Submitted:

17 January 2024

Posted:

18 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Executive Summary

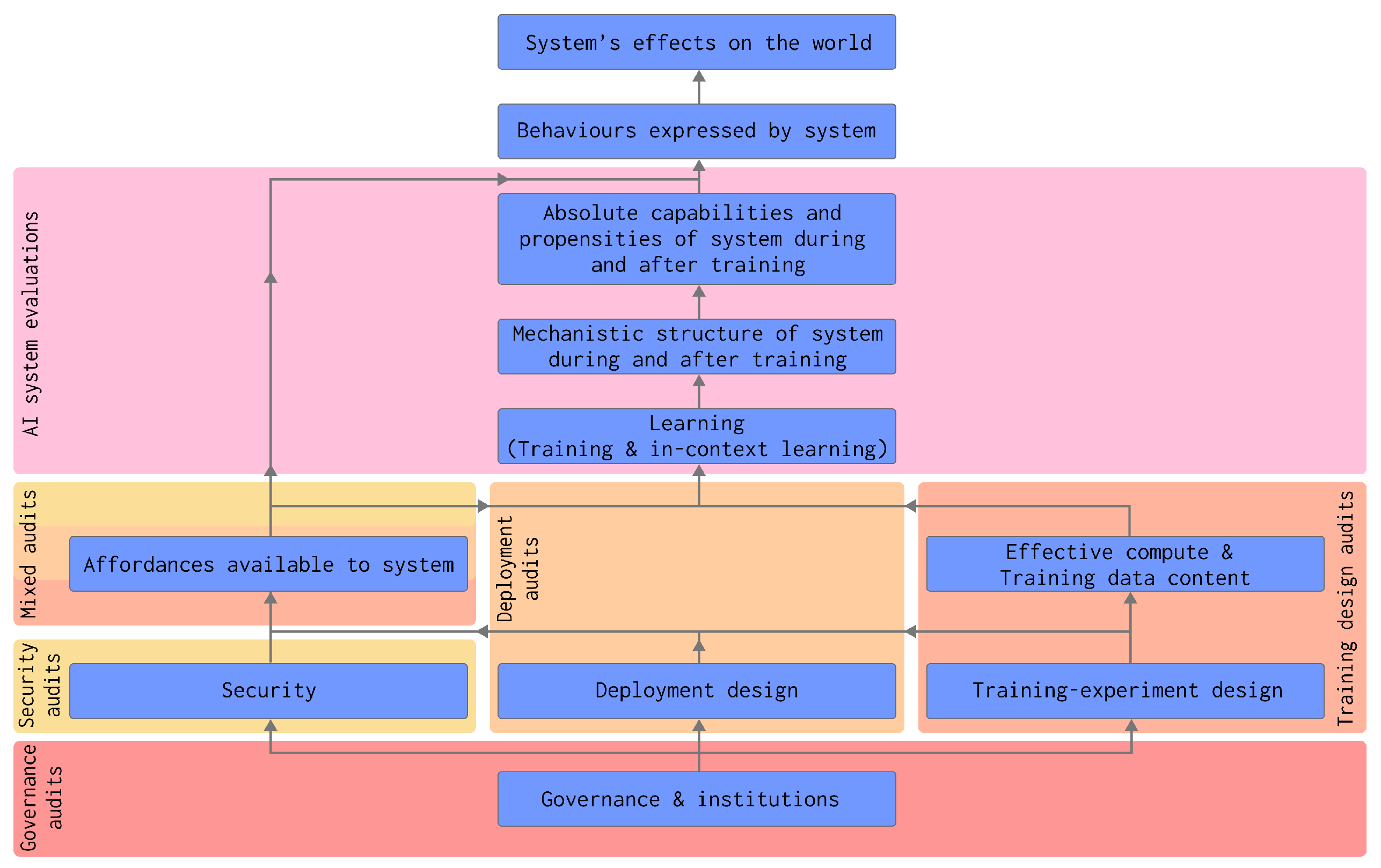

- A causal framework: Our framework works backwards through the causal chain that leads to the effects that AI systems have on the world and discusses ways auditors may work toward assurances at each step in the chain.

- Conceptual clarity: We develop several distinctions that are useful in describing the chain of causality. Conceptual clarity should lead to better governance.

- Highlighting the importance of AI systems’ available affordances: We identify a key node in the causal chain - the affordances available to AI systems - which may be useful in designing regulation. The affordances available to AI systems are the environmental resources and opportunities for affecting the world that are available to it, e.g. whether it has access to the internet. These determine which capabilities the system can currently exercise. They can be constrained through guardrails, staged deployment, prompt filtering, safety requirements for open sourcing, and effective security. One of our key policy recommendations is that proposals to change the affordances available to an AI system should undergo auditing.

- AI system behaviors - The set of actions or outputs that a system actually produces and the context in which they occur (for example, the type of prompt that elicits the behavior).

- Available affordances - The environmental resources and opportunities for affecting the world that are available to an AI system.

- Absolute capabilities and propensities - The full set of potential behaviors that an AI system can exhibit and its tendency to exhibit them.

- Mechanistic structure of the AI system during and after training - The structure of the function that the AI system implements, comprising architecture, parameters, and inputs.

- Learning - The processes by which AI systems develop mechanistic structures that are able to exhibit intelligent-seeming behavior.

- Effective compute and training data content - The amount of compute used to train an AI system and the effectiveness of the algorithms used in training; and the content of the data used to train an AI system.

- Security - Adequate information security, physical security, and response protocols.

- Deployment design - The design decisions that determine how an AI system will be deployed, including who has access to what functions of the AI system and when they have access.

- Training-experiment design - The design decisions that determine the procedure by which an AI system is trained.

- Governance and institutions - The governance landscape in which AI training-experiment and security decisions are made, including of institutions, regulations, standards, and norms.

- AI system evaluations

- Security audits

- Deployment audits

- Training design audits

- Governance audits.

1. Introduction

- Causal framework: Our framework begins with the target of our assurance efforts - the effects that AI systems have on the world - and works backwards through the causal process that leads to them. This provides an overarching framework for conceptualizing the governance of general-purpose AI systems. We hope that a framework will help to highlight potential regulatory blindspots and ensure comprehensiveness.

- Conceptual engineering for clarity: In developing the framework, we found we needed to use distinctions that we had not previously encountered. For instance, in Section 2.2 we distinguish between absolute, contextual, and reachable capabilities, which we found useful for thinking about how AI systems interact with their environment and, hence, about regulations concerning their eventual effects on the world. We also reframe the focus from AI models to the slightly broader concept of AI systems (Section 2.1).

- Highlighting the importance of AI systems’ available affordances: One of the benefits of the technical focus of the framework is that it highlights a key concept, the affordances available to AI systems (defined in Section 2.2) as a key variable for regulations, and serves as a unifying frame for many related concepts such as AI system deployment, open sourcing, access to code interpreters, guardrails, and more. The concept of available affordances adds important nuance to the ‘training phase-deployment phase’ distinction, a distinction that arguably formed the keystone of previous frameworks.

2. Our framework: Auditing the determinants of AI systems’ effects

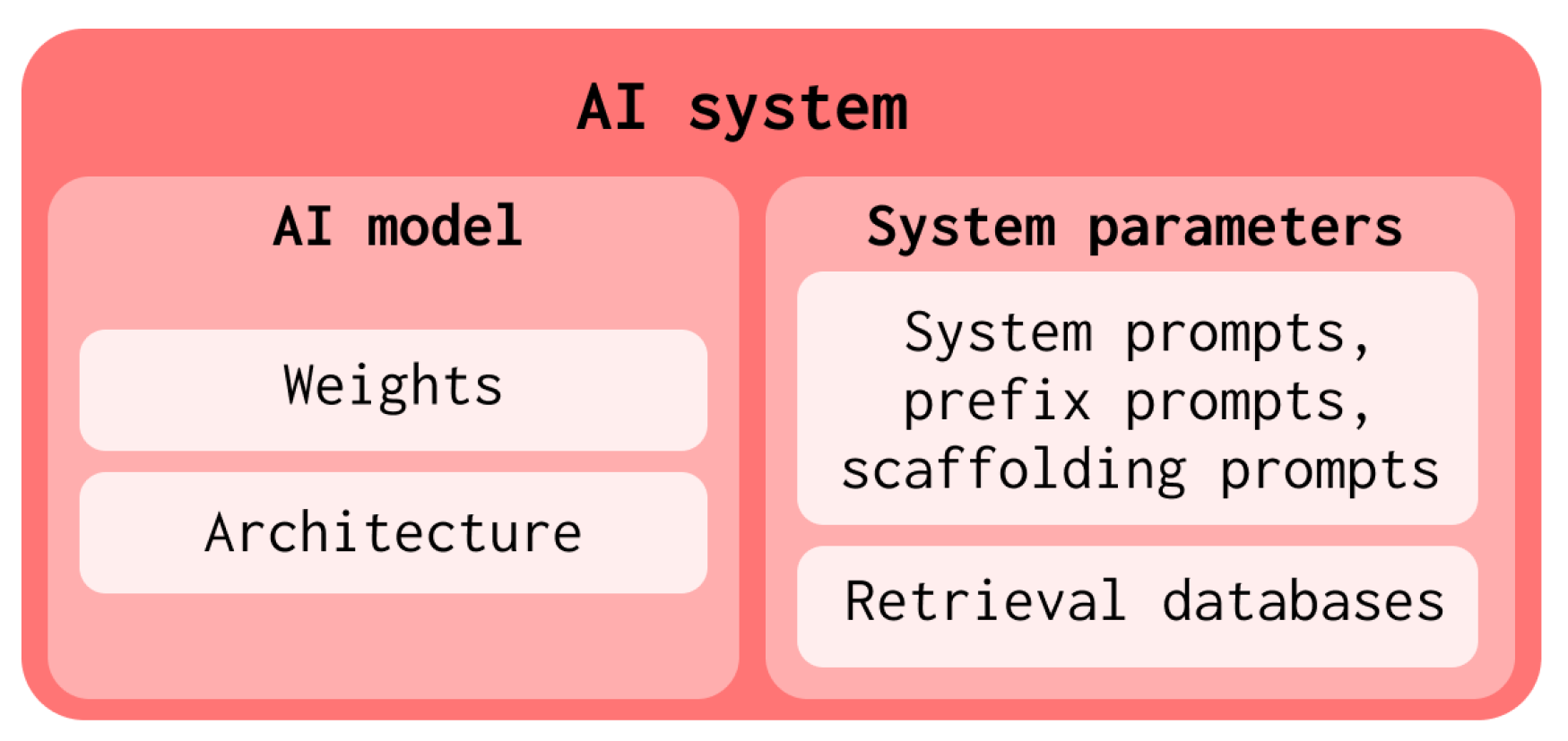

2.1. Conceptualizing AI systems vs. AI models

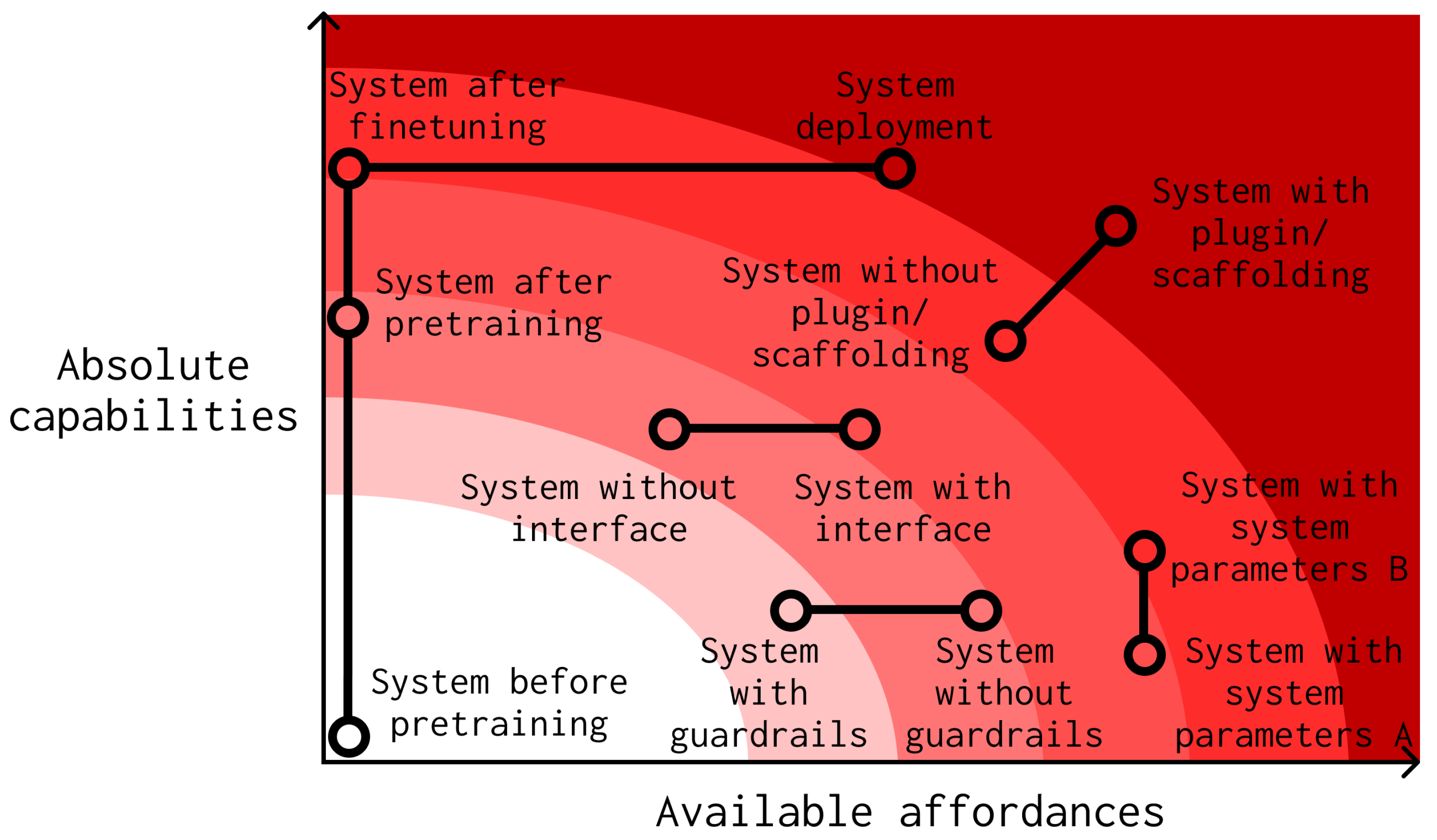

- System prompts, prefix prompts, and scaffolding: System prompts and prefix prompts are prefixed to any user-generated prompts that are input to AI models (Section 2.3.4). These prompts substantially modify system behavior. For instance: A model may not itself possess cyber offensive capabilities. But if part of its system prompt contains documentation for cyber offense software, then, through in-context learning (Section 2.3.4), the system may exhibit dangerous cyber offense capabilities capabilities. This materially affects which systems are safe to deploy. If a lab wants to change the system prompt of a deployed model, it could change the capabilities profile enough to warrant repeated audits. Similarly, AI systems with few-shot prompts or chain-of-thought prompts (examples of prefix prompts) are more capable of answering questions than without those prompts that prefix their outputs. It is possible to arrange systems of models such that outputs of some models are programmatically input to other models (e.g. [15,16,17]). These systems, which often involve using different scaffolding prompts in each of the models in the system, have different capability profiles than systems without scaffolding prompts.

- Retrieval databases: Retrieval databases (Section 2.3.4) may sometimes be considered parameters of the model [18] and other times parameters of the AI system (of which the model is a part) [19]. In both cases, the retrieval databases meaningfully influence the capabilities of the system, which may influence the outcomes of evaluations. We therefore expand the focus of what we consider important to evaluate in order to include all factors that influence the capabilities profile of the system.

2.2. Conceptualizing AI system capabilities

- AI system behaviors. The set of actions or outputs that a system actually produces and the context in which they occur (for example, the type of prompt that elicits the behavior). In this article, we exclusively mean behaviors that could be useful to the system or a user, rather than arbitrary or random behaviors that might be produced by an untrained system.

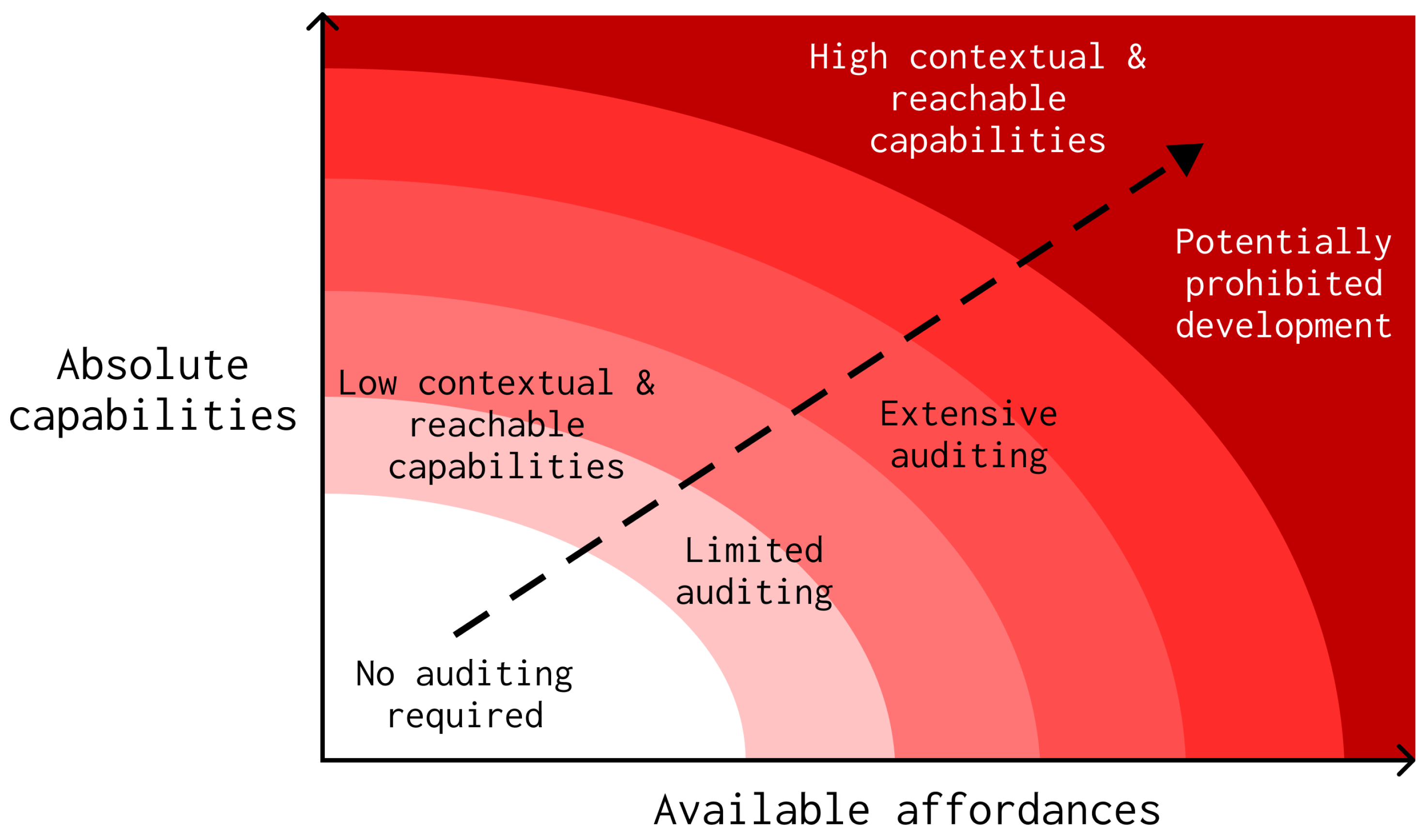

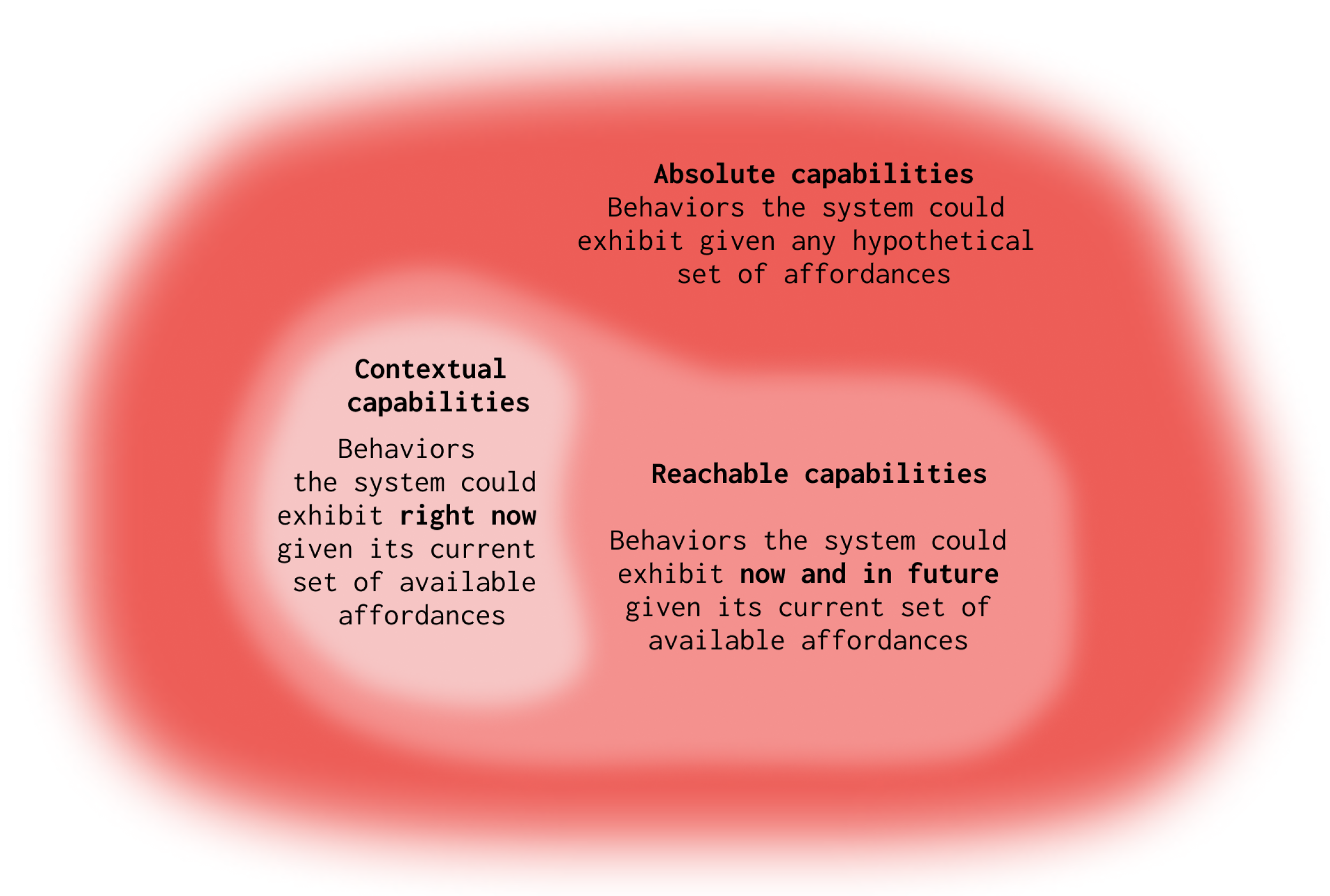

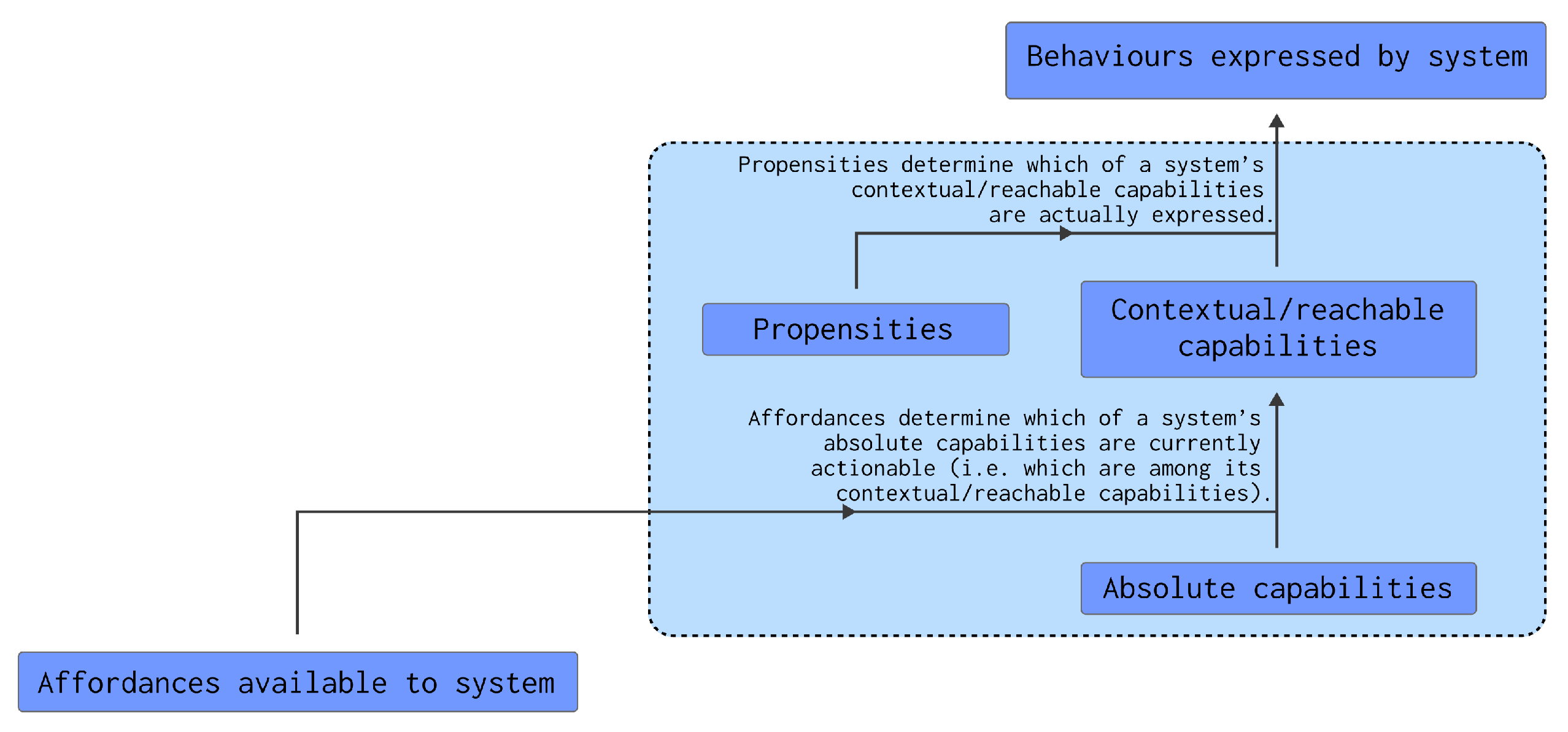

- Available affordances. The environmental resources and opportunities for influencing the world that are available to a system. We can exert control over the affordances available to a system through deployment decisions, training design decisions, guardrails, and security measures. As we’ll see below, the available affordances determine which of a system’s absolute capabilities are its contextual capabilities and reachable capabilities (Figure 3). Systems with greater available affordances have constant absolute capabilities but greater contextual and reachable capabilities (Figure 5).

-

Absolute capabilities. The potential set of behaviors that a system could exhibit given any hypothetical set of available affordances (regardless of whether the system can reach them from its current context) (Figure 2).

- −

- Example: If a trained system is saved in cold storage and not loaded, it is not contextually or reachably capable of behaving as a chat bot, even if it is absolutely capable of doing so. To become contextually or reachably capable of behaving as a chat bot, it must be loaded from storage and used for inference.

-

Contextual capabilities. The potential set of behaviors that a system could exhibit right now given its current set of available affordances in its current environmental context (Figure 2).

- −

- Example: A system may be absolutely capable of browsing the web, but if it does not have access to the internet (i.e., an available affordance), then it is not contextually capable of browsing the web.

-

Reachable capabilities. The potential set of behaviors that a system could exhibit given its current set of available affordances (i.e. contextual capabilities) as well as all the affordances the system could eventually make available from its current environmental context. A system’s reachable capabilities include and directly follow from a system’s contextual capabilities (Figure 2).

- −

- Example: A system, such as GPT4, may not be able to add two six-digit numbers. Therefore, six-digit addition is not within its contextual capabilities. However, if it can browse the web, it could navigate to a calculator app to successfully add the numbers. Therefore, six-digit addition is within its reachable capabilities.

-

System propensities. The tendency of a system to express one behavior over another (Figure 3). Even though systems may be capable of a wide range of behaviors, they may have a tendency to express only particular behaviors. Just because a system may be capable of a dangerous behavior, it might not be inclined to exhibit it. It is therefore important that audits assess a system’s propensities using ‘alignment evaluations’ [9].

- −

- Example: Instead of responding to user requests to produce potentially harmful or discriminatory content, some language models, such as GPT-3.5, usually respond with a polite refusal to produce such content. This happens even though the system is capable of producing such content, as demonstrated when the system is ‘jailbroken’. We say that such systems have a propensity not to produce harmful or offensive content.

2.3. The determinants of AI systems’ effects on the world

- Affordances available to the system

- Absolute capabilities and propensities of the system during and after training

- Mechanistic structure of the system during and after training

- Learning

- Effective compute and training data content

- Security

- Deployment design

- Training-experiment design

- Governance and institutions

- AI system evaluations

- Security audits

- Deployment audits

- Training design audits

- Governance audits.

2.3.1. Affordances available to a system

- Extent of system distribution

- Actuators, interfaces, and scaffolding

- Online vs offline training

- Guardrails

Extent of system distribution

Actuators, interfaces, and scaffolding

Online vs offline training

Extent of guardrails

Summary of recommendations regarding affordances available to AI systems

- Proposed changes in the affordances available to a system (including changes to the extent of a system’s distribution, online/offline training, actuators, interfaces, plugins, scaffolding, and guardrails) should undergo auditing, including conduct risk assessments, scenario planning, and evaluations.

- AI systems’ deployment should be staged such that distribution increases in the next stage only if it is deemed safe.

- Model parameters should not be open sourced unless they can be demonstrated to be safe.

- All copies of highly absolutely capable models should be tracked and secured.

- Guardrails should be in place to constrain the affordances available to AI systems.

2.3.2. Absolute capabilities and propensities of a system

- Risk assessments prior to certain gain-of-function experiments to ensure that the risks are worth the benefits.

- Requirement of official certification to perform certain gain-of-function work, reducing risks from irresponsible or underqualified actors.

- Information controls. Given the risk that information obtained by gain-of-function research may proliferate, there should be controls on its reporting. Auditors should be able to report gain-of-function results to regulators, who may have regulatory authority on decisions whether to prevent or reduce system deployment, and not necessarily to AI system developers or the broader scientific community.

Summary of proposed changes regarding absolute capabilities and propensities of AI systems

- Evaluate dangerous capabilities and propensities continually throughout and after training.

- When such experiments involve extremely capable AI systems, auditors should require certification to perform gain-of-function experiments, similar to AI developers; risk assessments prior to gain-of-function experiments should be required; and information controls on reporting gain-of-function results should be implemented.

- Have enforceable action plans following concerning evaluations.

2.3.3. Mechanistic structure of a system

Summary of recommendations regarding the mechanistic structure of AI systems

- Do not overstate the guarantees about an AI system’s absolute capabilities and propensities that can be achieved through behavioral evaluations alone.

- Incorporate interpretability into capability and alignment evaluations as soon as possible.

- Develop forms of structured access for external auditors to enable necessary research and evaluations.

2.3.4. Learning

Pretraining and fine-tuning

- Iterative hallucination reduction, as in GPT-4 [43];

- Different training objectives that increase absolute capabilities on downstream metrics, such as UL2 training [44];

- Fine-tuning two independently trained models so they operate as one model, such as Flamingo, which combines a vision model with a language model [46];

Learning from prompts and retrieval databases

Summary of recommendations regarding learning

- For each new experiment, require audits in proportion to expected capability increases from pretraining or fine-tuning.

- Filter prompts and retrieval databases to avoid AI systems learning potentially dangerous capabilities using in-context learning.

- When system parameters, such as retrieval databases, are changed, the AI system should undergo renewed auditing.

2.3.5. Effective compute and training data content

Effective compute

- Amount of compute Given that AI systems that undergo additional training may have increased absolute capabilities, they should require additional auditing. Unfortunately, even though the absolute amount of computation used in training-experiments correlates with a system’s absolute capabilities, it is not possible to use it to predict accurately when particular capabilities will emerge [48,49,50]. We want to avoid risky scenarios where systems trained with increasing amounts of compute suddenly become able to exhibit certain dangerous behavior. We may be able to do this by evaluating systems trained with a lower level of compute to understand their capabilities profiles before moving to systems trained with slightly more. Risk assessments should ensure that slightly smaller systems have undergone adequate auditing before permission is given to develop larger systems. If compute thresholds exist, auditors may ensure that training-experiment designs and the experiments themselves do not exceed permitted thresholds.

-

Algorithmic progress AI is a dual-use technology; it has great potential for both good and harm. Due to its dual-use nature, widespread access to large amounts of effective compute could result in proliferation of dangerous misuse risks (such as systems capable of automating the discovery of zero-day exploits on behalf of bad actors) or accident risks (such as systems capable of autonomous exfiltration and replication). Algorithmic progress is one of the key inputs to effective compute. Thus, when tasked with governing effective compute, policymakers are faced with a challenge: Algorithmic improvements are often published openly. But future publications may have unpredictable effects on the amount of effective compute available to all actors. Therefore, the standard publication norm or openness may therefore unintentionally provide dangerous actors with increased effective compute. Policymakers may therefore consider it necessary from a security perspective to implement publication controls, such as requiring pre-publication risk assessments, in order to prevent undesirable actors gaining access to potentially dangerous amounts of effective compute. Such publication controls for dual-use technologies have precedent; they are the norm in nuclear technology, for instance [65]. It may not be possible to rely on lab self-regulation, since labs are incentivised to publish openly in order to garner prestige or to attract the best researchers. Regulation would therefore likely be required to ensure that pre-publication risk assessments take national security into account sufficiently. Assessing risks of publication may require significant independent technical expertise, a role which regulators may either have in-house or could be drawn from auditing organizations.In addition to facilitating pre-publication risk assessments, auditing organizations may also serve as monitors of algorithmic progress within labs, since doing so would require access to frontier AI systems in order to evaluate them, adequate technical capacity, and independence from other incentives. Between AI labs, regulators, and auditors, it may therefore be the case that auditors are the best positioned actors to perform this function. However, currently no consensus metric of algorithmic progress exists and further research is required to identify metrics that are predictive of capability levels. Building a ‘science of evals’ and designing metrics that are more predictive of capabilities than compute should be priority research areas.

Training data content

Summary of recommendations regarding effective compute and training data content

- For each new experiment, require audits in proportion to expected capability increases from additional effective compute or different training data content.

- Conduct risk assessments of slightly smaller AI systems before approval is given to develop a larger system.

- Place strict controls on training-experiments that use above a certain level of effective compute.

- Implement national security-focused publication controls on research related to AI capabilities.

- Auditors should be able to evaluate training data.

- Filter training data for potentially dangerous or sensitive content.

2.3.6. Security

Preventing AI system theft and espionage

Preventing misuse of AI systems

Protection from dangerous autonomous AI systems

Incident response plans

Summary of recommendations regarding security

- Organizations with access to advanced AI systems should have military-grade information security, espionage protection, and red-teaming protocols.

- Implement strict cyber- and physical security practices to prevent unauthorized access and AI system exfiltration.

- Structured access APIs and other technical controls to enable secure development and sharing with researchers, auditors, or the broader public.

- Individuals with high levels of access to AI systems should require background checks.

- Information sharing of security and safety incidents between labs.

- The level of access to AI systems given to developers, researchers, and auditors should be appropriate and not excessive.

- Monitoring of compute usage to ensure compliance with regulations regarding the amount of compute used and how it is used.

- Prompt filtering and other input controls to prevent malicious and dangerous use, such as prohibited scaffolding methods.

- Fail-safes and rapid response plans in case the AI system does gain access to more affordances (e.g. by auto-exfiltration).

- Mandatory reporting of safety and security incidents.

2.3.7. Deployment design

Summary of recommendations regarding deployment design

- Deployment plans should be subject to auditing.

2.3.8. Training-experiment design

Summary of recommendations regarding training-experiment design

- Require pre-registration and pre-approval of training-experiments involving highly absolutely capable AI systems trained with large amounts of effective compute and AI systems with large affordances available to them.

- Training-experiment designs should be subject to prior-to-training risk assessment.

- Require developers of frontier AI systems to publish detailed alignment strategies or to make their plans available to auditors for scrutiny.

- Require regulator approval of experiments with highly capable AI systems, large sets of available affordances, or large effective compute budgets, based on risk assessments from internal and external auditors.

- Potentially require smaller scale experiments before further scaling compute. This helps assess effective compute and predict capabilities.

2.3.9. Governance and institutions

- Reviewing the adequacy of organizational governance structures

- Creating an audit trail of the frontier AI systems development process

- Mapping roles and responsibilities within organizations that design frontier AI systems.

Summary of recommendations regarding governance and institutions

- Labs and other relevant actors should be rendered transparent enough to regulators for effective governance.

- Regulators commission and act on governance audits when structuring the governance and institutional landscape.

3. Key areas of research

3.1. Technical AI safety research

- Interpretability and training dynamics: Improve methods for explaining the internal mechanisms of AI system behavior. Develop better understanding of how capabilities emerge during training through phase transitions. Use this to create predictive models that forecast emergence of new capabilities.

- Behavioral evaluations of dangerous capabilities: In advance of adequate interpretability methods, we should develop better behavioral methods for assessing risks from AI systems. We must develop evaluations that can serve as clear decision boundaries for particular kinds of regulatory or other risk-mitigating actions. We should improve our predictive models of how capabilities emerge in AI systems.

- Alignment theory: Further develop the theoretical understanding of how to create AI systems whose goals and incentives are robustly aligned with human values. This might eventually provide technically grounded metrics against which AI systems can be audited.

3.2. Technical infrastructure research

- Structured access frameworks: Design interfaces and structured access protocols that enable external auditors and researchers to safely analyze AI system mechanistic structure in ways that avoid misuse and proliferation.

- Auditing of training compute usage: Create methods to monitor and audit how computational resources are used during AI system training to ensure adherence to safety requirements and regulations. The methods would preferably be privacy-preserving, secure, and permit verification of code, data pipelines, compute usage, and other aspects of the training process.

- Technically grounded definitions of effective compute and algorithmic progress: A prerequisite for governance and auditing of effective compute is a technically grounded definition. Develop rigorous technical definitions and metrics for measuring the effective compute used during AI system training and for measuring algorithmic progress.

3.3. Institutional governance and policy research:

- Accountability of auditors: Research protocols and institutional designs that ensure accountability of auditors to the public, while also controlling potentially hazardous information flows.

- Institutional design for transformational technology: The current political economy of general-purpose AI development, which is currently driven by private interests, may permit less public accountability than is ideal for such a transformational technology. As the technology advances, we should consider alternative frameworks that bring AI development into a regime with a greater focus on security and public accountability, such as nationalization or internationalization.

- Adaptive policy making and enforcement: Build regulatory and policy-making capability to enable rapid adaptation of regulatory infrastructure as AI progresses at pace. Ensure that auditors adapt at the same pace.

- Legal frameworks: Explore legal tools like liability, regulations, and treaties to align AI with public interests. These provide the basis for compliance audits.

- Frameworks for cooperation: Develop frameworks to facilitate cooperation between governments and between companies on AI governance, even where little mutual trust exists. This may be required for auditors to operate cross-jurisdictionally, which will be required for a global approach to AI risk reduction.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; Bridgland, A.; Meyer, C.; Kohl, S.A.A.; Ballard, A.J.; Cowie, A.; Romera-Paredes, B.; Nikolov, S.; Jain, R.; Adler, J.; Back, T.; Petersen, S.; Reiman, D.; Clancy, E.; Zielinski, M.; Steinegger, M.; Pacholska, M.; Berghammer, T.; Bodenstein, S.; Silver, D.; Vinyals, O.; Senior, A.W.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Kohli, P.; Hassabis, D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, K.; Azizi, S.; Tu, T.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Scales, N.; Tanwani, A.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Pfohl, S.; et al.. Large language models encode clinical knowledge, 2023.

- Brundage, M.; Avin, S.; Clark, J.; Toner, H.; Eckersley, P.; Garfinkel, B.; Dafoe, A.; Scharre, P.; Zeitzoff, T.; Filar, B.; Anderson, H.S.; Roff, H.; Allen, G.C.; Steinhardt, J.; Flynn, C.; hÉigeartaigh, S.Ó.; Beard, S.; Belfield, H.; Farquhar, S.; Lyle, C.; Crootof, R.; Evans, O.; Page, M.; Bryson, J.; Yampolskiy, R.; Amodei, D. The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation. CoRR 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderljung, M.; Hazell, J. Protecting Society from AI Misuse: When are Restrictions on Capabilities Warranted?, 2023. arXiv:cs.AI/2303.09377.

- Solaiman, I.; Talat, Z.; Agnew, W.; Ahmad, L.; Baker, D.; Blodgett, S.L.; au2, H.D.I.; Dodge, J.; Evans, E.; Hooker, S.; Jernite, Y.; Luccioni, A.S.; Lusoli, A.; Mitchell, M.; Newman, J.; Png, M.T.; Strait, A.; Vassilev, A. Evaluating the Social Impact of Generative AI Systems in Systems and Society, 2023. arXiv:cs.CY/2306.05949.

- Hendrycks, D.; Mazeika, M.; Woodside, T. An Overview of Catastrophic AI Risks, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CY/2306.12001]. arXiv:cs.CY/2306.12001.

- Ngo, R.; Chan, L.; Mindermann, S. The alignment problem from a deep learning perspective, 2023. arXiv:cs.AI/2209.00626.

- Schuett, J.; Dreksler, N.; Anderljung, M.; McCaffary, D.; Heim, L.; Bluemke, E.; Garfinkel, B. Towards best practices in AGI safety and governance: A survey of expert opinion, 2023. arXiv:cs.CY/2305.07153.

- Shevlane, T.; Farquhar, S.; Garfinkel, B.; Phuong, M.; Whittlestone, J.; Leung, J.; Kokotajlo, D.; Marchal, N.; Anderljung, M.; Kolt, N.; Ho, L.; Siddarth, D.; Avin, S.; Hawkins, W.; Kim, B.; Gabriel, I.; Bolina, V.; Clark, J.; Bengio, Y.; Christiano, P.; Dafoe, A. Model evaluation for extreme risks, 2023. arXiv:cs.AI/2305.15324.

- Anderljung, M.; Barnhart, J.; Korinek, A.; Leung, J.; O’Keefe, C.; Whittlestone, J.; Avin, S.; Brundage, M.; Bullock, J.; Cass-Beggs, D.; Chang, B.; Collins, T.; Fist, T.; Hadfield, G.; Hayes, A.; Ho, L.; Hooker, S.; Horvitz, E.; Kolt, N.; Schuett, J.; Shavit, Y.; Siddarth, D.; Trager, R.; Wolf, K. Frontier AI Regulation: Managing Emerging Risks to Public Safety, 2023. arXiv:cs.CY/2307.03718.

- Whittlestone, J.; Clark, J. Why and How Governments Should Monitor AI Development, 2021. arXiv:cs.CY/2108.12427.

- Mökander, J.; Schuett, J.; Kirk, H.R.; Floridi, L. Auditing large language models: a three-layered approach. AI and Ethics 2023. [CrossRef]

- Raji, I.D.; Xu, P.; Honigsberg, C.; Ho, D.E. Outsider Oversight: Designing a Third Party Audit Ecosystem for AI Governance, 2022. arXiv:cs.CY/2206.04737.

- Anderljung, M.; Smith, E.T.; O’Brien, J.; Soder, L.; Bucknall, B.; Bluemke, E.; Schuett, J.; Trager, R.; Strahm, L.; Chowdhury., R. Towards Publicly Accountable Frontier LLMs: Building an External Scrutiny Ecosystem under the ASPIRE Framework., forthcoming.

- Yao, S.; Yu, D.; Zhao, J.; Shafran, I.; Griffiths, T.L.; Cao, Y.; Narasimhan, K. Tree of Thoughts: Deliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models, 2023. arXiv:cs.CL/2305.10601.

- Long, J. Large Language Model Guided Tree-of-Thought, 2023. arXiv:cs.AI/2305.08291.

- Gravitas, S. Significant-Gravitas/AutoGPT: An experimental open-source attempt to make GPT-4 fully autonomous. https://github.com/Significant-Gravitas/AutoGPT, 2023. (Accessed on 10/13/2023).

- Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Hoffmann, J.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; Millican, K.; van den Driessche, G.; Lespiau, J.B.; Damoc, B.; Clark, A.; de Las Casas, D.; Guy, A.; Menick, J.; Ring, R.; Hennigan, T.; Huang, S.; Maggiore, L.; Jones, C.; Cassirer, A.; Brock, A.; Paganini, M.; Irving, G.; Vinyals, O.; Osindero, S.; Simonyan, K.; Rae, J.W.; Elsen, E.; Sifre, L. Improving language models by retrieving from trillions of tokens, 2022. arXiv:cs.CL/2112.04426.

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; tau Yih, W.; Rocktäschel, T.; Riedel, S.; Kiela, D. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H.; Ranzato, M.; Hadsell, R.; Balcan, M.; Lin, H., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2020, Vol. 33, pp. 9459–9474.

- Heim, L. Information security considerations for AI and the long term future. https://blog.heim.xyz/information-security-considerations-for-ai/, 2022. (Accessed on 10/12/2023).

- Boiko, D.A.; MacKnight, R.; Gomes, G. Emergent autonomous scientific research capabilities of large language models, 2023. arXiv:physics.chem-ph/2304.05332.

- Brohan, A.; Brown, N.; Carbajal, J.; Chebotar, Y.; Chen, X.; Choromanski, K.; Ding, T.; Driess, D.; Dubey, A.; Finn, C.; Florence, P.; Fu, C.; Arenas, M.G.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Han, K.; Hausman, K.; Herzog, A.; Hsu, J.; Ichter, B.; Irpan, A.; Joshi, N.; Julian, R.; Kalashnikov, D.; Kuang, Y.; Leal, I.; Lee, L.; Lee, T.W.E.; Levine, S.; Lu, Y.; Michalewski, H.; Mordatch, I.; Pertsch, K.; Rao, K.; Reymann, K.; Ryoo, M.; Salazar, G.; Sanketi, P.; Sermanet, P.; Singh, J.; Singh, A.; Soricut, R.; Tran, H.; Vanhoucke, V.; Vuong, Q.; Wahid, A.; Welker, S.; Wohlhart, P.; Wu, J.; Xia, F.; Xiao, T.; Xu, P.; Xu, S.; Yu, T.; Zitkovich., B. RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control, 2022. (Accessed on 10/12/2023).

- OpenAI. ChatGPT plugins. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt-plugins#code-interpreter, 2023. (Accessed on 10/12/2023).

- Reed, S.; Zolna, K.; Parisotto, E.; Colmenarejo, S.G.; Novikov, A.; Barth-maron, G.; Giménez, M.; Sulsky, Y.; Kay, J.; Springenberg, J.T.; Eccles, T.; Bruce, J.; Razavi, A.; Edwards, A.; Heess, N.; Chen, Y.; Hadsell, R.; Vinyals, O.; Bordbar, M.; de Freitas, N. A Generalist Agent. Transactions on Machine Learning Research 2022. Featured Certification, Outstanding Certification.

- Wang, G.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Mandlekar, A.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, L.; Anandkumar, A. Voyager: An Open-Ended Embodied Agent with Large Language Models, 2023. arXiv:cs.AI/2305.16291.

- Bubeck, S.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Eldan, R.; Gehrke, J.; Horvitz, E.; Kamar, E.; Lee, P.; Lee, Y.T.; Li, Y.; Lundberg, S.; Nori, H.; Palangi, H.; Ribeiro, M.T.; Zhang, Y. Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4, 2023. arXiv:cs.CL/2303.12712.

- Schick, T.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Dessì, R.; Raileanu, R.; Lomeli, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Cancedda, N.; Scialom, T. Toolformer: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Use Tools, 2023. arXiv:cs.CL/2302.04761.

- Rando, J.; Paleka, D.; Lindner, D.; Heim, L.; Tramèr, F. Red-Teaming the Stable Diffusion Safety Filter, 2022. arXiv:cs.AI/2210.04610.

- Turner, A.M.; Smith, L.; Shah, R.; Critch, A.; Tadepalli, P. Optimal Policies Tend to Seek Power, 2019. arXiv:cs.AI/1912.01683.

- Reynolds, L.; McDonell, K. Prompt Programming for Large Language Models: Beyond the Few-Shot Paradigm, 2021. arXiv:cs.CL/2102.07350.

- Shin, T.; Razeghi, Y.; au2, R.L.L.I.; Wallace, E.; Singh, S. AutoPrompt: Eliciting Knowledge from Language Models with Automatically Generated Prompts, 2020. arXiv:cs.CL/2010.15980.

- Wen, Y.; Jain, N.; Kirchenbauer, J.; Goldblum, M.; Geiping, J.; Goldstein, T. Hard Prompts Made Easy: Gradient-Based Discrete Optimization for Prompt Tuning and Discovery, 2023. arXiv:cs.LG/2302.03668.

- Jones, E.; Dragan, A.; Raghunathan, A.; Steinhardt, J. Automatically Auditing Large Language Models via Discrete Optimization, 2023. arXiv:cs.LG/2303.04381.

- Li, X.L.; Liang, P. Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation, 2021. arXiv:cs.CL/2101.00190.

- Christiano, P.; Leike, J.; Brown, T.B.; Martic, M.; Legg, S.; Amodei, D. Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences, 2017, [arXiv:stat.ML/1706.03741]. arXiv:stat.ML/1706.03741.

- Levinstein, B.A.; Herrmann, D.A. Still No Lie Detector for Language Models: Probing Empirical and Conceptual Roadblocks, 2023. arXiv:cs.CL/2307.00175.

- Trask, A.; Sukumar, A.; Kalliokoski, A.; Farkas, B.; Ezenwaka, C.; Popa, C.; Mitchell, C.; Hrebenach, D.; Muraru, G.C.; Junior, I.; Bejan, I.; Mishra, I.; Ngong, I.; Bandy, J.; Stahl, J.; Cardonnet, J.; Trask, K.; Trask, K.; Nguyen, K.; Dang, K.; van der Veen, K.; Eng, K.; Strahm, L.; Ayre, L.; Jay, M.; Lytvyn, O.; Kyemenu-Sarsah, O.; Chung, P.; Smith, P.; S, R.; Falcon, R.; Gupta, S.; Gabriel, S.; Milea, T.; Thoraldson, T.; Porto, T.; Cebere, T.; Gorana, Y.; Reza., Z. How to audit an AI model owned by someone else (part 1). https://blog.openmined.org/ai-audit-part-1/, 2023. (Accessed on 10/13/2023).

- Shevlane, T. Structured access: an emerging paradigm for safe AI deployment, 2022. arXiv:cs.AI/2201.05159.

- von Oswald, J.; Niklasson, E.; Randazzo, E.; Sacramento, J.; Mordvintsev, A.; Zhmoginov, A.; Vladymyrov, M. Transformers learn in-context by gradient descent, 2023. arXiv:cs.LG/2212.07677.

- Xie, S.M.; Raghunathan, A.; Liang, P.; Ma, T. An Explanation of In-context Learning as Implicit Bayesian Inference, 2022. arXiv:cs.CL/2111.02080.

- Wei, J.; Bosma, M.; Zhao, V.Y.; Guu, K.; Yu, A.W.; Lester, B.; Du, N.; Dai, A.M.; Le, Q.V. Finetuned Language Models Are Zero-Shot Learners, 2022. arXiv:cs.CL/2109.01652.

- Bai, Y.; Kadavath, S.; Kundu, S.; Askell, A.; Kernion, J.; Jones, A.; Chen, A.; Goldie, A.; Mirhoseini, A.; McKinnon, C.; Chen, C.; Olsson, C.; Olah, C.; Hernandez, D.; Drain, D.; Ganguli, D.; Li, D.; Tran-Johnson, E.; Perez, E.; Kerr, J.; Mueller, J.; Ladish, J.; Landau, J.; Ndousse, K.; Lukosuite, K.; Lovitt, L.; Sellitto, M.; Elhage, N.; Schiefer, N.; Mercado, N.; DasSarma, N.; Lasenby, R.; Larson, R.; Ringer, S.; Johnston, S.; Kravec, S.; Showk, S.E.; Fort, S.; Lanham, T.; Telleen-Lawton, T.; Conerly, T.; Henighan, T.; Hume, T.; Bowman, S.R.; Hatfield-Dodds, Z.; Mann, B.; Amodei, D.; Joseph, N.; McCandlish, S.; Brown, T.; Kaplan, J. Constitutional AI: Harmlessness from AI Feedback, 2022. arXiv:cs.CL/2212.08073.

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report, 2023. arXiv:cs.CL/2303.08774.

- Tay, Y.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Tran, V.Q.; So, D.R.; Shakeri, S.; Garcia, X.; Zheng, H.S.; Rao, J.; Chowdhery, A.; Zhou, D.; Metzler, D.; Petrov, S.; Houlsby, N.; Le, Q.V.; Dehghani, M. Transcending Scaling Laws with 0.1. arXiv:cs.CL/2210.11399.

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models, 2021. arXiv:cs.CL/2106.09685.

- Alayrac, J.B.; Donahue, J.; Luc, P.; Miech, A.; Barr, I.; Hasson, Y.; Lenc, K.; Mensch, A.; Millican, K.; Reynolds, M.; Ring, R.; Rutherford, E.; Cabi, S.; Han, T.; Gong, Z.; Samangooei, S.; Monteiro, M.; Menick, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Brock, A.; Nematzadeh, A.; Sharifzadeh, S.; Binkowski, M.; Barreira, R.; Vinyals, O.; Zisserman, A.; Simonyan, K. Flamingo: a Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning, 2022. arXiv:cs.CV/2204.14198.

- Wu, Y.; Rabe, M.N.; Hutchins, D.; Szegedy, C. Memorizing Transformers, 2022. arXiv:cs.LG/2203.08913.

- Srivastava, A.; Rastogi, A.; Rao, A.; Shoeb, A.A.M.; Abid, A.; Fisch, A.; Brown, A.R.; Santoro, A.; Gupta, A.; Garriga-Alonso, A.; Kluska, A.; Lewkowycz, A.; Agarwal, A.; Power, A.; Ray, A.; Warstadt, A.; Kocurek, A.W.; Safaya, A.; Tazarv, A.; Xiang, A.; Parrish, A.; Nie, A.; Hussain, A.; Askell, A.; Dsouza, A.; Slone, A.; Rahane, A.; Iyer, A.S.; Andreassen, A.; Madotto, A.; Santilli, A.; Stuhlmüller, A.; Dai, A.; La, A.; Lampinen, A.; Zou, A.; Jiang, A.; Chen, A.; Vuong, A.; Gupta, A.; Gottardi, A.; Norelli, A.; Venkatesh, A.; Gholamidavoodi, A.; Tabassum, A.; Menezes, A.; Kirubarajan, A.; Mullokandov, A.; Sabharwal, A.; Herrick, A.; Efrat, A.; Erdem, A.; Karakaş, A.; Roberts, B.R.; Loe, B.S.; Zoph, B.; Bojanowski, B.; Özyurt, B.; Hedayatnia, B.; Neyshabur, B.; Inden, B.; Stein, B.; Ekmekci, B.; Lin, B.Y.; Howald, B.; Orinion, B.; Diao, C.; Dour, C.; Stinson, C.; Argueta, C.; Ramírez, C.F.; Singh, C.; Rathkopf, C.; Meng, C.; Baral, C.; Wu, C.; Callison-Burch, C.; Waites, C.; Voigt, C.; Manning, C.D.; Potts, C.; Ramirez, C.; Rivera, C.E.; Siro, C.; Raffel, C.; Ashcraft, C.; Garbacea, C.; Sileo, D.; Garrette, D.; Hendrycks, D.; Kilman, D.; Roth, D.; Freeman, D.; Khashabi, D.; Levy, D.; González, D.M.; Perszyk, D.; Hernandez, D.; Chen, D.; Ippolito, D.; Gilboa, D.; Dohan, D.; Drakard, D.; Jurgens, D.; Datta, D.; Ganguli, D.; Emelin, D.; Kleyko, D.; Yuret, D.; Chen, D.; Tam, D.; Hupkes, D.; Misra, D.; Buzan, D.; Mollo, D.C.; Yang, D.; Lee, D.H.; Schrader, D.; Shutova, E.; Cubuk, E.D.; Segal, E.; Hagerman, E.; Barnes, E.; Donoway, E.; Pavlick, E.; Rodola, E.; Lam, E.; Chu, E.; Tang, E.; Erdem, E.; Chang, E.; Chi, E.A.; Dyer, E.; Jerzak, E.; Kim, E.; Manyasi, E.E.; Zheltonozhskii, E.; Xia, F.; Siar, F.; Martínez-Plumed, F.; Happé, F.; Chollet, F.; Rong, F.; Mishra, G.; Winata, G.I.; de Melo, G.; Kruszewski, G.; Parascandolo, G.; Mariani, G.; Wang, G.; Jaimovitch-López, G.; Betz, G.; Gur-Ari, G.; Galijasevic, H.; Kim, H.; Rashkin, H.; Hajishirzi, H.; Mehta, H.; Bogar, H.; Shevlin, H.; Schütze, H.; Yakura, H.; Zhang, H.; Wong, H.M.; Ng, I.; Noble, I.; Jumelet, J.; Geissinger, J.; Kernion, J.; Hilton, J.; Lee, J.; Fisac, J.F.; Simon, J.B.; Koppel, J.; Zheng, J.; Zou, J.; Kocoń, J.; Thompson, J.; Wingfield, J.; Kaplan, J.; Radom, J.; Sohl-Dickstein, J.; Phang, J.; Wei, J.; Yosinski, J.; Novikova, J.; Bosscher, J.; Marsh, J.; Kim, J.; Taal, J.; Engel, J.; Alabi, J.; Xu, J.; Song, J.; Tang, J.; Waweru, J.; Burden, J.; Miller, J.; Balis, J.U.; Batchelder, J.; Berant, J.; Frohberg, J.; Rozen, J.; Hernandez-Orallo, J.; Boudeman, J.; Guerr, J.; Jones, J.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Rule, J.S.; Chua, J.; Kanclerz, K.; Livescu, K.; Krauth, K.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Ignatyeva, K.; Markert, K.; Dhole, K.D.; Gimpel, K.; Omondi, K.; Mathewson, K.; Chiafullo, K.; Shkaruta, K.; Shridhar, K.; McDonell, K.; Richardson, K.; Reynolds, L.; Gao, L.; Zhang, L.; Dugan, L.; Qin, L.; Contreras-Ochando, L.; Morency, L.P.; Moschella, L.; Lam, L.; Noble, L.; Schmidt, L.; He, L.; Colón, L.O.; Metz, L.; Şenel, L.K.; Bosma, M.; Sap, M.; ter Hoeve, M.; Farooqi, M.; Faruqui, M.; Mazeika, M.; Baturan, M.; Marelli, M.; Maru, M.; Quintana, M.J.R.; Tolkiehn, M.; Giulianelli, M.; Lewis, M.; Potthast, M.; Leavitt, M.L.; Hagen, M.; Schubert, M.; Baitemirova, M.O.; Arnaud, M.; McElrath, M.; Yee, M.A.; Cohen, M.; Gu, M.; Ivanitskiy, M.; Starritt, M.; Strube, M.; Swędrowski, M.; Bevilacqua, M.; Yasunaga, M.; Kale, M.; Cain, M.; Xu, M.; Suzgun, M.; Walker, M.; Tiwari, M.; Bansal, M.; Aminnaseri, M.; Geva, M.; Gheini, M.; T, M.V.; Peng, N.; Chi, N.A.; Lee, N.; Krakover, N.G.A.; Cameron, N.; Roberts, N.; Doiron, N.; Martinez, N.; Nangia, N.; Deckers, N.; Muennighoff, N.; Keskar, N.S.; Iyer, N.S.; Constant, N.; Fiedel, N.; Wen, N.; Zhang, O.; Agha, O.; Elbaghdadi, O.; Levy, O.; Evans, O.; Casares, P.A.M.; Doshi, P.; Fung, P.; Liang, P.P.; Vicol, P.; Alipoormolabashi, P.; Liao, P.; Liang, P.; Chang, P.; Eckersley, P.; Htut, P.M.; Hwang, P.; Miłkowski, P.; Patil, P.; Pezeshkpour, P.; Oli, P.; Mei, Q.; Lyu, Q.; Chen, Q.; Banjade, R.; Rudolph, R.E.; Gabriel, R.; Habacker, R.; Risco, R.; Millière, R.; Garg, R.; Barnes, R.; Saurous, R.A.; Arakawa, R.; Raymaekers, R.; Frank, R.; Sikand, R.; Novak, R.; Sitelew, R.; LeBras, R.; Liu, R.; Jacobs, R.; Zhang, R.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Chi, R.; Lee, R.; Stovall, R.; Teehan, R.; Yang, R.; Singh, S.; Mohammad, S.M.; Anand, S.; Dillavou, S.; Shleifer, S.; Wiseman, S.; Gruetter, S.; Bowman, S.R.; Schoenholz, S.S.; Han, S.; Kwatra, S.; Rous, S.A.; Ghazarian, S.; Ghosh, S.; Casey, S.; Bischoff, S.; Gehrmann, S.; Schuster, S.; Sadeghi, S.; Hamdan, S.; Zhou, S.; Srivastava, S.; Shi, S.; Singh, S.; Asaadi, S.; Gu, S.S.; Pachchigar, S.; Toshniwal, S.; Upadhyay, S.; Shyamolima.; Debnath.; Shakeri, S.; Thormeyer, S.; Melzi, S.; Reddy, S.; Makini, S.P.; Lee, S.H.; Torene, S.; Hatwar, S.; Dehaene, S.; Divic, S.; Ermon, S.; Biderman, S.; Lin, S.; Prasad, S.; Piantadosi, S.T.; Shieber, S.M.; Misherghi, S.; Kiritchenko, S.; Mishra, S.; Linzen, T.; Schuster, T.; Li, T.; Yu, T.; Ali, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Wu, T.L.; Desbordes, T.; Rothschild, T.; Phan, T.; Wang, T.; Nkinyili, T.; Schick, T.; Kornev, T.; Tunduny, T.; Gerstenberg, T.; Chang, T.; Neeraj, T.; Khot, T.; Shultz, T.; Shaham, U.; Misra, V.; Demberg, V.; Nyamai, V.; Raunak, V.; Ramasesh, V.; Prabhu, V.U.; Padmakumar, V.; Srikumar, V.; Fedus, W.; Saunders, W.; Zhang, W.; Vossen, W.; Ren, X.; Tong, X.; Zhao, X.; Wu, X.; Shen, X.; Yaghoobzadeh, Y.; Lakretz, Y.; Song, Y.; Bahri, Y.; Choi, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Belinkov, Y.; Hou, Y.; Hou, Y.; Bai, Y.; Seid, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Z. Beyond the Imitation Game: Quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models, 2023. arXiv:cs.CL/2206.04615.

- Wei, J.; Tay, Y.; Bommasani, R.; Raffel, C.; Zoph, B.; Borgeaud, S.; Yogatama, D.; Bosma, M.; Zhou, D.; Metzler, D.; Chi, E.H.; Hashimoto, T.; Vinyals, O.; Liang, P.; Dean, J.; Fedus, W. Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models, 2022. arXiv:cs.CL/2206.07682.

- Ganguli, D.; Hernandez, D.; Lovitt, L.; Askell, A.; Bai, Y.; Chen, A.; Conerly, T.; Dassarma, N.; Drain, D.; Elhage, N.; Showk, S.E.; Fort, S.; Hatfield-Dodds, Z.; Henighan, T.; Johnston, S.; Jones, A.; Joseph, N.; Kernian, J.; Kravec, S.; Mann, B.; Nanda, N.; Ndousse, K.; Olsson, C.; Amodei, D.; Brown, T.; Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Olah, C.; Amodei, D.; Clark, J. Predictability and Surprise in Large Generative Models. 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. ACM, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Agarwal, S.; Herbert-Voss, A.; Krueger, G.; Henighan, T.; Child, R.; Ramesh, A.; Ziegler, D.M.; Wu, J.; Winter, C.; Hesse, C.; Chen, M.; Sigler, E.; Litwin, M.; Gray, S.; Chess, B.; Clark, J.; Berner, C.; McCandlish, S.; Radford, A.; Sutskever, I.; Amodei, D. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners, 2020. arXiv:cs.CL/2005.14165.

- Olsson, C.; Elhage, N.; Nanda, N.; Joseph, N.; DasSarma, N.; Henighan, T.; Mann, B.; Askell, A.; Bai, Y.; Chen, A.; Conerly, T.; Drain, D.; Ganguli, D.; Hatfield-Dodds, Z.; Hernandez, D.; Johnston, S.; Jones, A.; Kernion, J.; Lovitt, L.; Ndousse, K.; Amodei, D.; Brown, T.; Clark, J.; Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Olah, C. In-context Learning and Induction Heads, 2022. arXiv:cs.LG/2209.11895.

- Raventós, A.; Paul, M.; Chen, F.; Ganguli, S. Pretraining task diversity and the emergence of non-Bayesian in-context learning for regression, 2023. arXiv:cs.LG/2306.15063.

- Wei, J.; Wei, J.; Tay, Y.; Tran, D.; Webson, A.; Lu, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Huang, D.; Zhou, D.; Ma, T. Larger language models do in-context learning differently, 2023. arXiv:cs.CL/2303.03846.

- Langchain. Introduction | Langchain. https://python.langchain.com/docs/get_started/introduction, 2023. (Accessed on 10/13/2023).

- Izacard, G.; Lewis, P.; Lomeli, M.; Hosseini, L.; Petroni, F.; Schick, T.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Joulin, A.; Riedel, S.; Grave, E. Atlas: Few-shot Learning with Retrieval Augmented Language Models, 2022. arXiv:cs.CL/2208.03299.

- Zhong, Z.; Lei, T.; Chen, D. Training Language Models with Memory Augmentation, 2022. arXiv:cs.CL/2205.12674.

- Karpukhin, V.; Oğuz, B.; Min, S.; Lewis, P.; Wu, L.; Edunov, S.; Chen, D.; tau Yih, W. Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering, 2020. arXiv:cs.CL/2004.04906.

- Guu, K.; Lee, K.; Tung, Z.; Pasupat, P.; Chang, M.W. REALM: Retrieval-Augmented Language Model Pre-Training, 2020. arXiv:cs.CL/2002.08909.

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models, 2020. arXiv:cs.LG/2001.08361.

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; de Las Casas, D.; Hendricks, L.A.; Welbl, J.; Clark, A.; Hennigan, T.; Noland, E.; Millican, K.; van den Driessche, G.; Damoc, B.; Guy, A.; Osindero, S.; Simonyan, K.; Elsen, E.; Rae, J.W.; Vinyals, O.; Sifre, L. Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models, 2022. arXiv:cs.CL/2203.15556.

- Sevilla, J.; Heim, L.; Ho, A.; Besiroglu, T.; Hobbhahn, M.; Villalobos, P. Compute Trends Across Three Eras of Machine Learning, 2022. arXiv:cs.LG/2202.05924.

- Erdil, E.; Besiroglu, T. Algorithmic progress in computer vision, 2023. arXiv:cs.CV/2212.05153.

- Tucker, A.D.; Anderljung, M.; Dafoe, A. Social and Governance Implications of Improved Data Efficiency. Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; AIES ’20, p. 378–384. [CrossRef]

- Wasil, A.; Siegmann, C.; Ezell, C.; Richardson, A. WasilEzellRichardsonSiegmann+(10).pdf. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6276a63ecf564172c125f58e/t/641cbc1d84814a4d0f3e1788/1679604766050/WasilEzellRichardsonSiegmann+%2810%29.pdf, 2023. (Accessed on 10/13/2023).

- Gunasekar, S.; Zhang, Y.; Aneja, J.; Mendes, C.C.T.; Giorno, A.D.; Gopi, S.; Javaheripi, M.; Kauffmann, P.; de Rosa, G.; Saarikivi, O.; Salim, A.; Shah, S.; Behl, H.S.; Wang, X.; Bubeck, S.; Eldan, R.; Kalai, A.T.; Lee, Y.T.; Li, Y. Textbooks Are All You Need, 2023. arXiv:cs.CL/2306.11644.

- Eldan, R.; Li, Y. TinyStories: How Small Can Language Models Be and Still Speak Coherent English?, 2023. arXiv:cs.CL/2305.07759.

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer, 2023. arXiv:cs.LG/1910.10683.

- Korbak, T.; Shi, K.; Chen, A.; Bhalerao, R.; Buckley, C.L.; Phang, J.; Bowman, S.R.; Perez, E. Pretraining Language Models with Human Preferences, 2023. arXiv:cs.CL/2302.08582.

- Chan, J.S.; Pieler, M.; Jao, J.; Scheurer, J.; Perez, E. Few-shot Adaptation Works with UnpredicTable Data, 2022. arXiv:cs.CL/2208.01009.

- Zou, A.; Wang, Z.; Kolter, J.Z.; Fredrikson, M. Universal and Transferable Adversarial Attacks on Aligned Language Models, 2023. arXiv:cs.CL/2307.15043.

- Shavit, Y. What does it take to catch a Chinchilla? Verifying Rules on Large-Scale Neural Network Training via Compute Monitoring, 2023. arXiv:cs.LG/2303.11341.

- Everitt, T.; Carey, R.; Langlois, E.; Ortega, P.A.; Legg, S. Agent Incentives: A Causal Perspective, 2021. arXiv:cs.AI/2102.01685.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).