1. Introduction

There are concerns internationally around the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of health and social care practitioners who provide care for people living with dementia [

1]. Globally, the prevalence of dementia is 55 million with projections indicating an increase to 139 million by 2050 [

2,

3]. Notably, most of these people, approximately 75%, are anticipated to be concentrated in low- and middle-income countries [

4].

In India, dementia prevalence for people aged 60 years and older is estimated to be 7.4% and increasing due to demographic transition [

5]. Despite this, there is limited awareness and stigma associated with the condition [

1]. Dementia symptoms can be considered as non-pathological deviations from normal ageing and supported within systems of family care with limited input from professionals [

6]. The Indian Government has recognized the challenges with special provision for people with dementia included in national health programs and policy [

1]. The Dementia India Report [

7] highlighted health professional education as a critical component when developing national dementia services. Key areas for change included the development of in-service training for health professionals and Train the Trainer programs for carers and community health workers.

In the UK, dementia workforce development through education has been articulated in several government reports and strategies [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Dementia education in adult social care is a priority to meet the needs of practitioners who are increasingly providing specialist dementia care. Evidence suggests that asynchronous online courses can benefit social care practitioners in terms of knowledge and skills development [

15,

16]; however, social distancing requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the value of integrating both asynchronous and synchronous delivery methods [

17]. No studies are known to have combined asynchronous and synchronous online dementia education for social care practitioners, nor are there any studies known to have evaluated technology-enabled dementia education in India.

1.1. The Intervention

Dementia Education for Workforce Excellence (DEWE) was developed during the COVID-19 pandemic to equip health and social care practitioners to work in increasingly digitalized and ageing societies with growing numbers of people with dementia. DEWE integrated the philosophy of care within the Standards of Dementia Care in Scotland [

11] that are underpinned by three National Dementia Strategies [

10,

12,

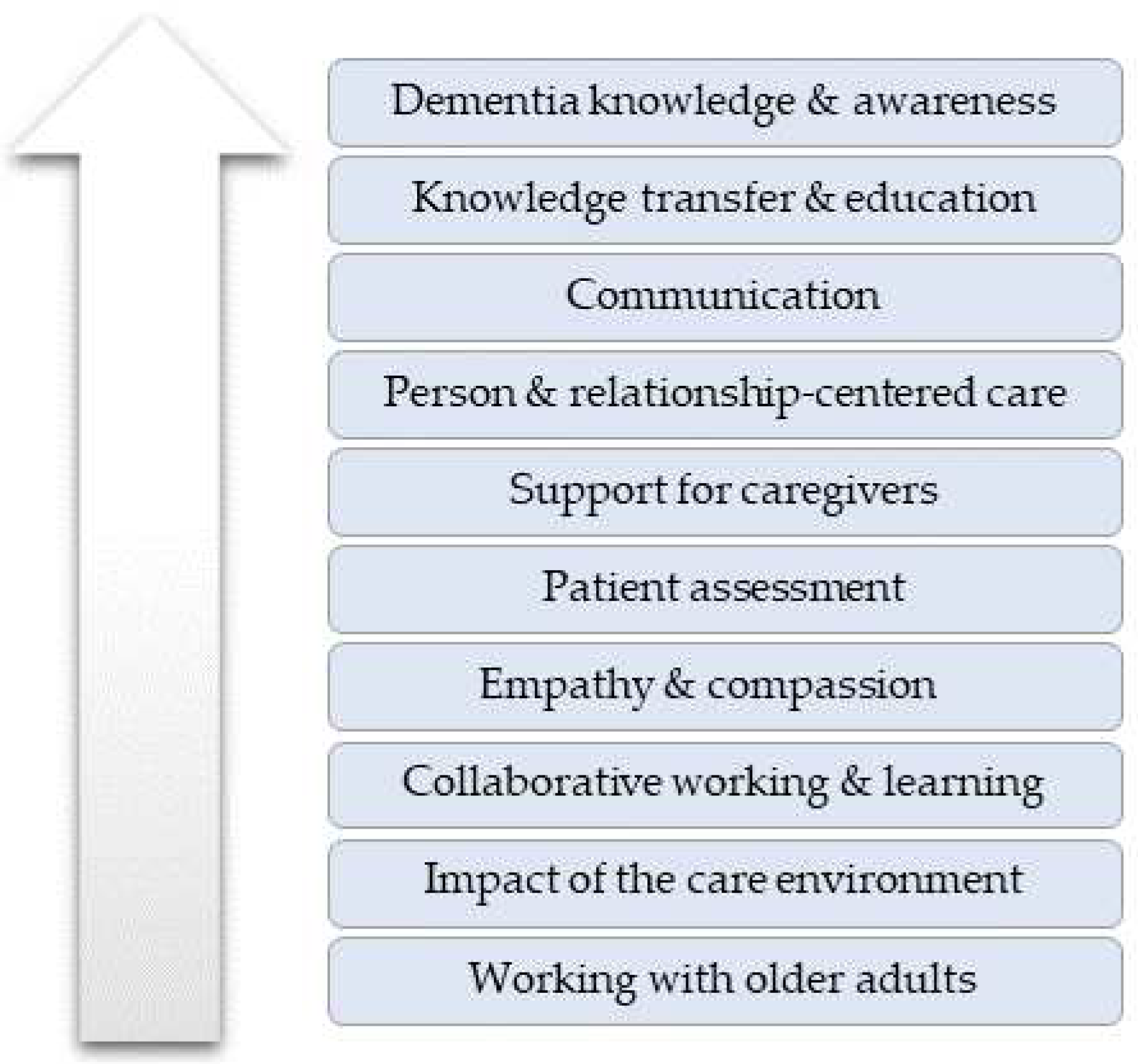

13]. Program development was informed by Scotland's national dementia workforce development framework (Promoting Excellence: A framework for all health and social services staff working with people with dementia, their families, and carers) [

14]. This framework prioritizes the rights of individuals living with dementia and integrates their dementia journey in its framework, structured at four practice levels: Informed, Skilled, Enhanced, and Expert. The levels correspond to the frequency and intensity of interactions that practitioners engage with people affected by dementia within their unique practice settings. DEWE was aligned to the skilled level of Promoting Excellence which outlines the knowledge and skills required by practitioners who have direct and/or substantial contact with people living with dementia.

The project lead previously developed two innovative and comprehensive dementia curricula for pre-registration nurse education in Scotland: Being Dementia Smart [

18] and Dementia Enhanced Education to Promote Excellence (DEEPE) both mapped at the enhanced level of the Promoting Excellence Framework. DEWE was developed adopting a similar approach with input and consensus from an expert group that consisted of academics; clinicians; educational technologists; and experts with lived experience of dementia or dementia care giving.

DEWE lends itself to bichronous online learning – a blend of both asynchronous and synchronous delivery methods [

17] where participants can participate flexibly during the asynchronous parts of the course alongside real-time participation for the synchronous sessions. For the asynchronous component, participants had free access to three online workbooks (Dementia Care Essentials; Dementia Care Priorities; & Dementia Care Enablers) with content mapped along the stages of the dementia journey. The key narrative was based on ‘Barbara’s Story’ [

19], a fictional story, that demonstrates the various stages and associated complexities of the dementia journey supported by learning activities and opportunities for reflective discussions. Learning resources also included short videos created by a general practitioner as an expert with lived experience of dementia [

20] from an emic perspective with insights into the higher needs of people with dementia including social activity, sense of belonging, self-esteem, and meaning in life [

21]. Furthermore, a relationship-centered approach to dementia care was embedded to emphasize the importance of recognizing the value of support for the wellbeing of both formal and informal carers to ensure high-quality person-centered dementia care [

22]. Synchronous sessions (n=16), via the Cisco Webex Platform, were spread over 6 weeks which allowed participation in real-time sessions facilitated by experts (with lived experience of dementia care giving and professionals). Live sessions embraced the philosophy of person-centered dementia care regularly interspersed with opportunities for reflective learning on dementia care from pre diagnosis to end-of-life [

Table 1]. Participants in DEWE included care home practitioners, care at home practitioners, and nurse educators.

1.2. Aim and Objectives

The overarching aim of this study was to evaluate DEWE training delivered using a bichronous approach with practitioners and educators from three different contexts.

To explore participants’ perceptions on the content and quality of the dementia training.

To explore participants’ perceptions and experiences of accessing the dementia training using a bichronous approach.

3. Results: Survey Findings

3.1. Demographics

Participants were 34 nurse educators and social care practitioners from the UK and India who completed DEWE between July 2021 and March 2022. Educators (n=17) were either professors or associate/assistant professors in nursing, nursing lecturers, or nursing tutors. Practitioners (n=9) were carers and service managers. Eight participants reported their role as being ‘other’ but did not provide any further details on their role.

Table 2 demonstrates the participant demographics.

3.2. Experience of Dementia Care and Education

Twelve educators (70.6%) taught on BSc Nursing programs, two (11.8%) taught on general nursing programs, whilst one (5.9%) taught on postgraduate programs. The remaining educators (11.8%) taught on a combination of programs. Five practitioners (55.6%) provided care to more than 15 people with dementia on a typical workday, whilst two (22.2%) provided care to between 11 and 15 people. Two practitioners (22.2%) did not provide dementia care at work.

3.3. Access to DEWE

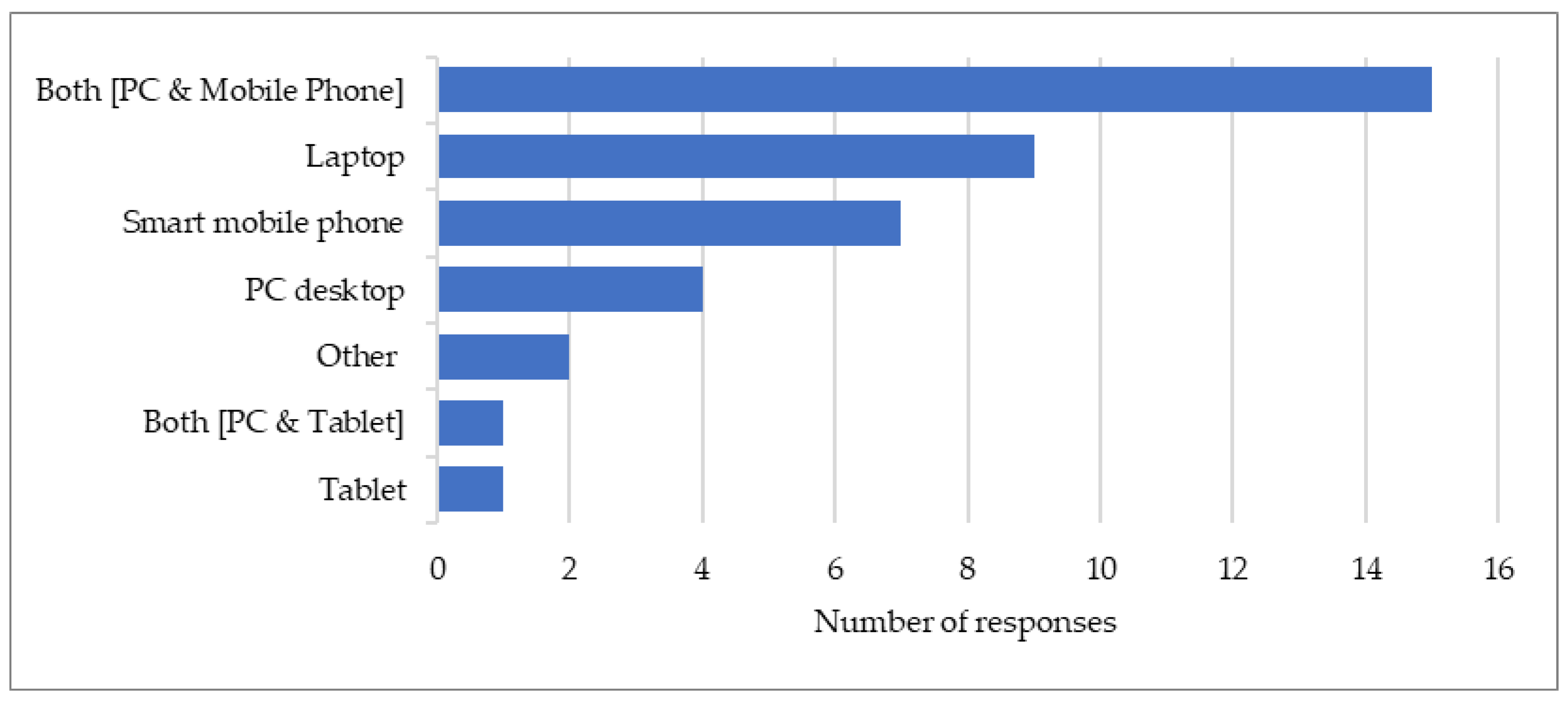

A combination of personal computers and smartphones were most frequently used to access DEWE.

Figure 1 demonstrates the devices used to access the training. Note the total does not tally to 34 (most likely as some participants have used multiple devices to access DEWE).

3.4. Level 1: Reaction to Asynchronous Resources

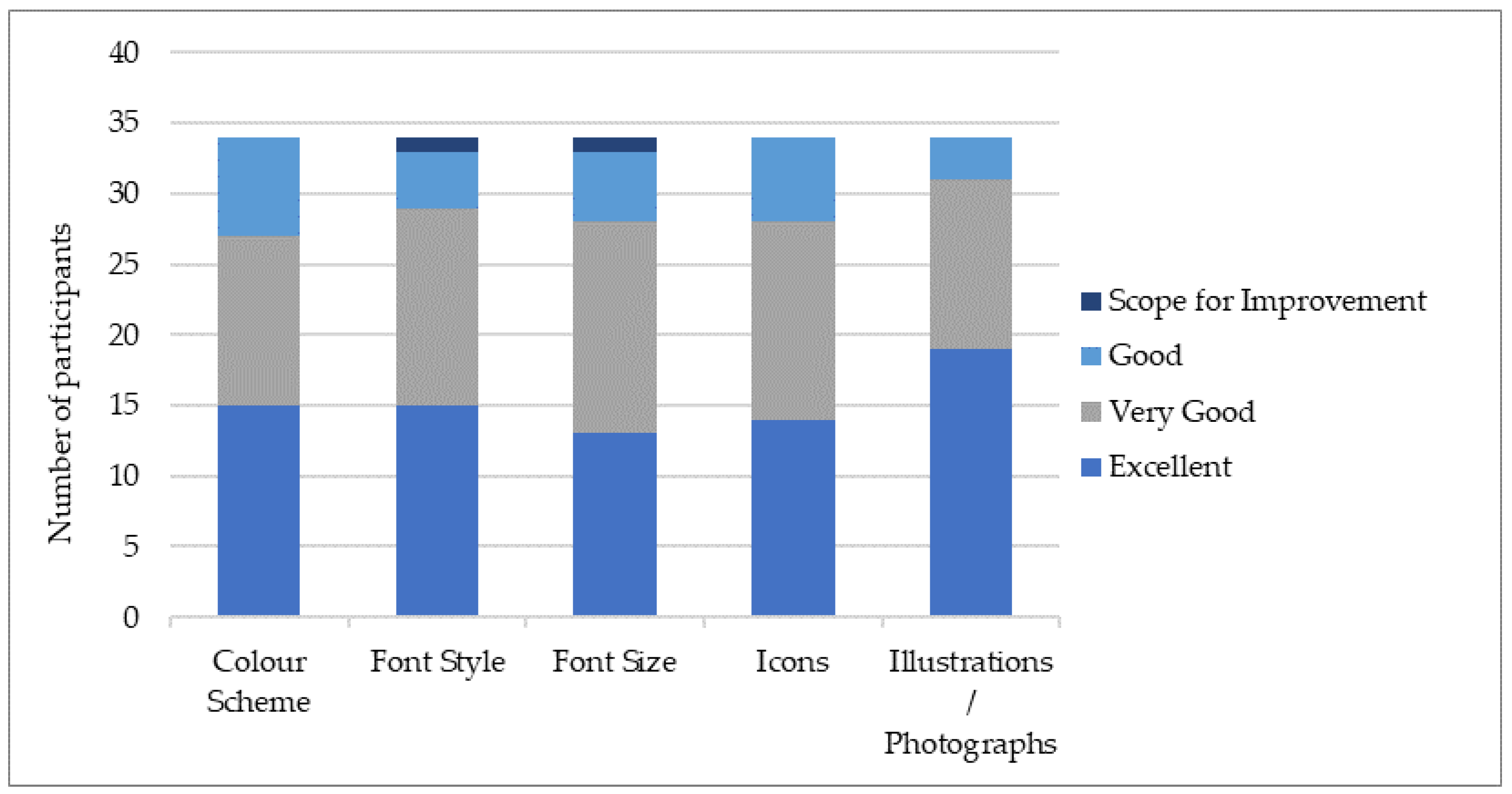

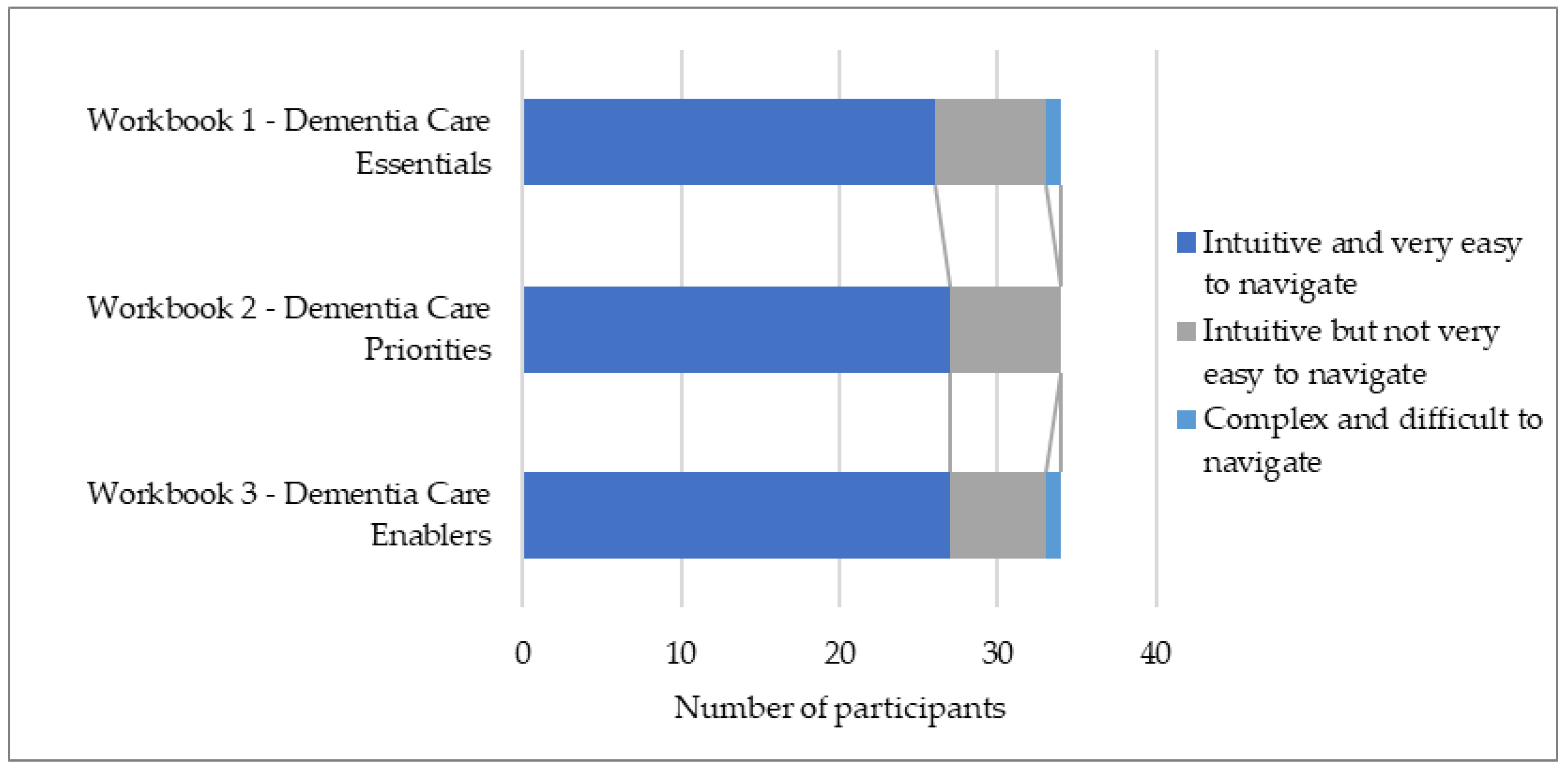

The presentation of the workbooks was highly rated among participants with most indicating the color scheme, font style, font size, icons, and illustrations being very good or excellent [

Figure 2]. There were high levels of agreement that the online workbooks were intuitive; however, some participants suggested that the workbooks were not easy to navigate [

Figure 3]. One participant suggested that the content could be more streamlined as ‘

a few videos were mixed up’ [80908493, Practitioner].

The workbooks were thought to work well but ‘did not translate to hard copy which some staff without IT skills preferred to use’ [92124189, Other]. Another participant suggested that ‘ease of use PDF copies would be useful’ [81022848, Practitioner].

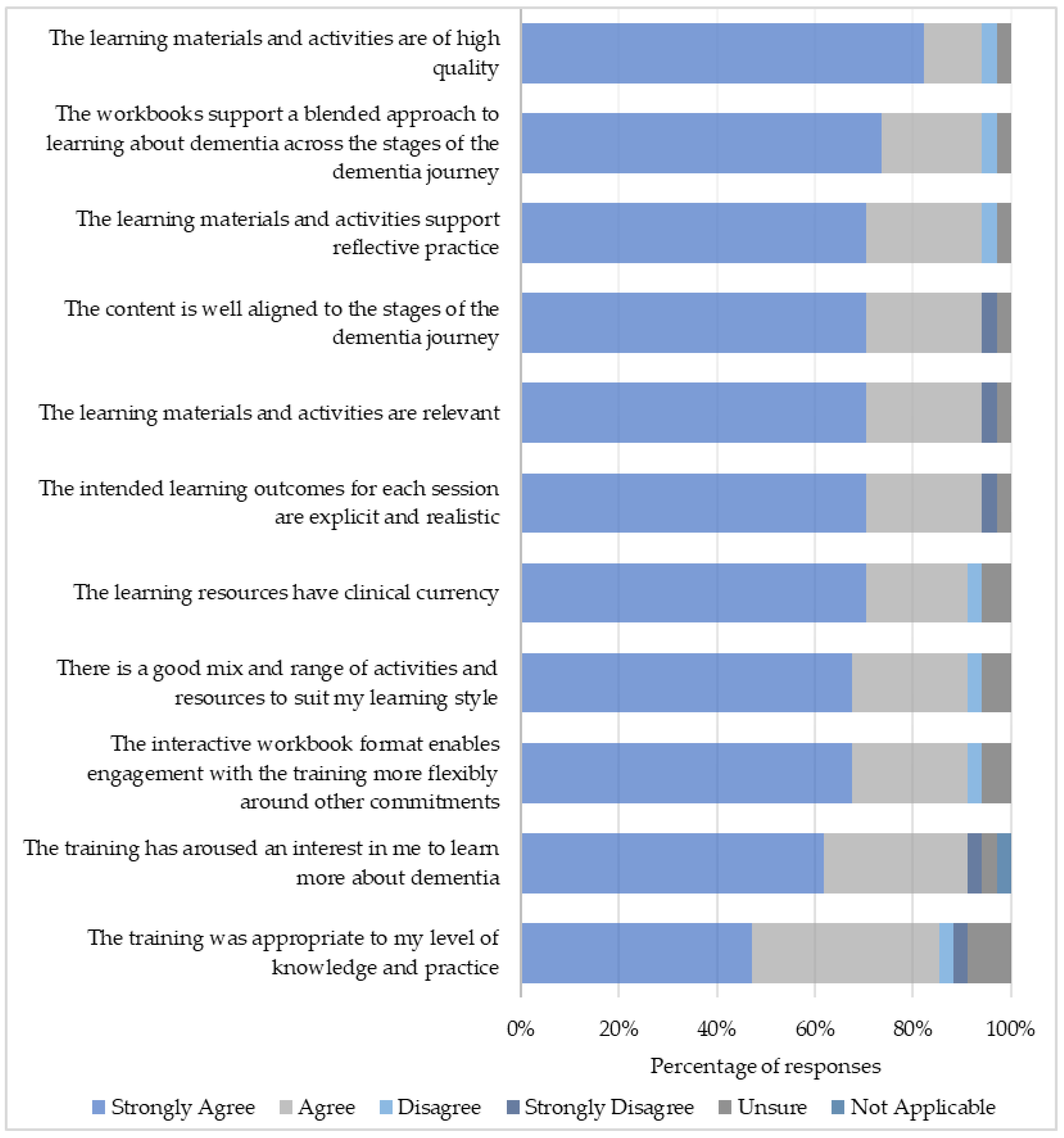

Twenty-four participants rated the overall quality of the workbooks on a scale of 1 – 10 (1 being poor and 10 being excellent). The median scores (with interquartile range) for the three workbooks were: 9 (9,10), 10 (9,10), and 9 (9,10) for Workbooks 1, 2, and 3 respectfully. The participants’ reaction to the training was also measured as levels of agreement to various aspects of the training content [

Figure 4].

3.5. Level 1: Reaction to Synchronous Resources

Feedback on the duration of the interactive sessions was mixed with some participants recommending a shorter duration whilst others recommended a longer duration. Alternative suggestions were to reduce the duration of interactive sessions and increase the frequency of sessions provided. Some participants were not satisfied with the delivery platform and recommended that this be changed for future delivery. Other suggestions to improve synchronous sessions included implementation of interactive icebreaker sessions, improved orientation to workbooks, and follow-up sessions.

3.6. Level 1: Reaction to Bichronous Learning

Participants described the aspects most and least enjoyed about blended learning in DEWE [

Table 3].

3.7. Preferred Mode of Learning

Twenty-four participants rated their preferred modes of dementia training on a scale of 1 – 5 (5 being most preferred and 1 being least preferred).

Figure 5 shows the median scores for each training modality with high levels of preference for a blended approach

.

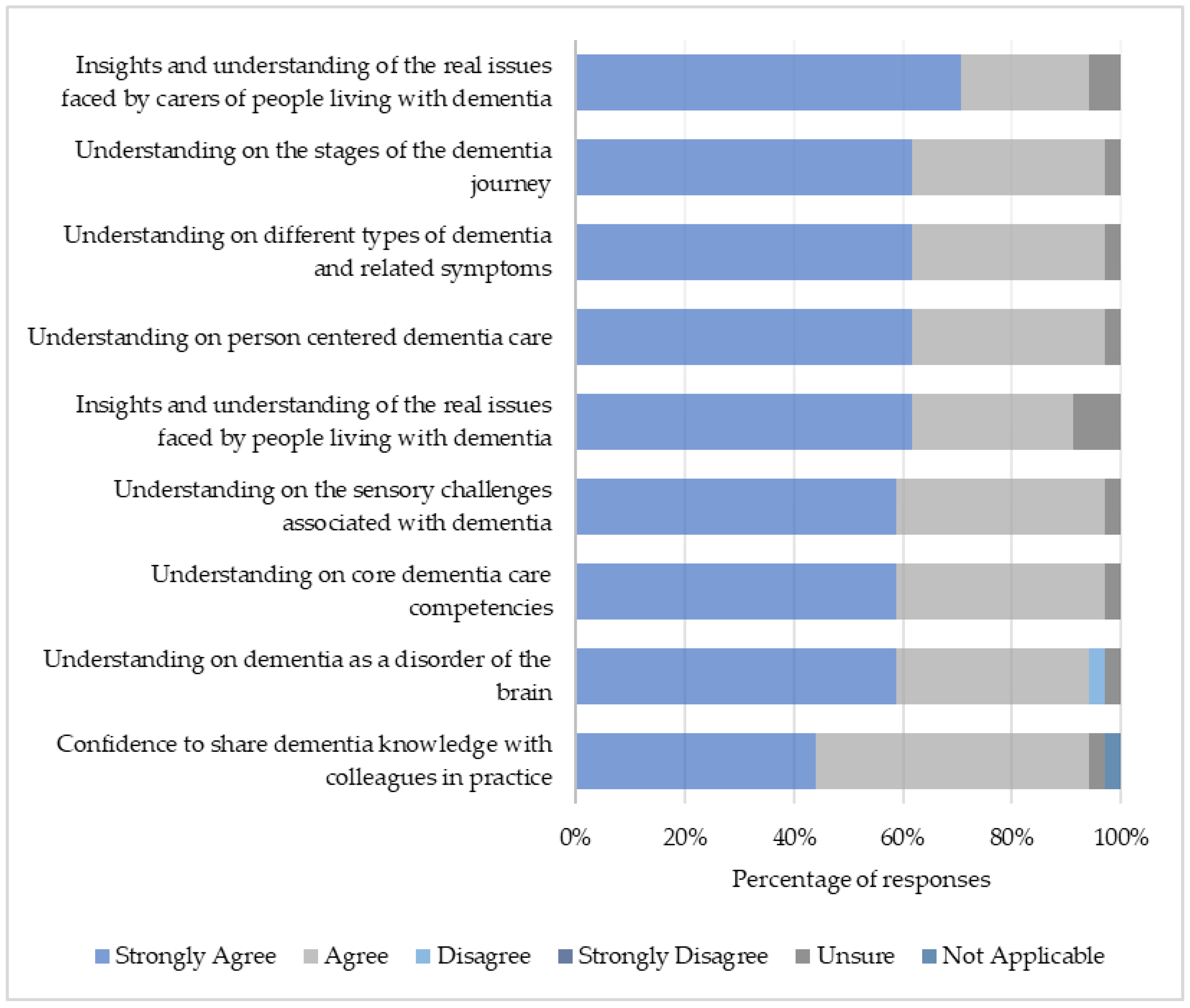

3.8. Level 2: Learning Gains

There were high levels of agreement that DEWE had enhanced aspects of dementia care knowledge [

Figure 6] and that learning outcomes had relevance to participants’ areas of professional practice [

Table 4]. Furthermore, most participants (91.2%) indicated that DEWE had enabled the development of relevant skills transferrable beyond the dementia care context [

Figure 7].

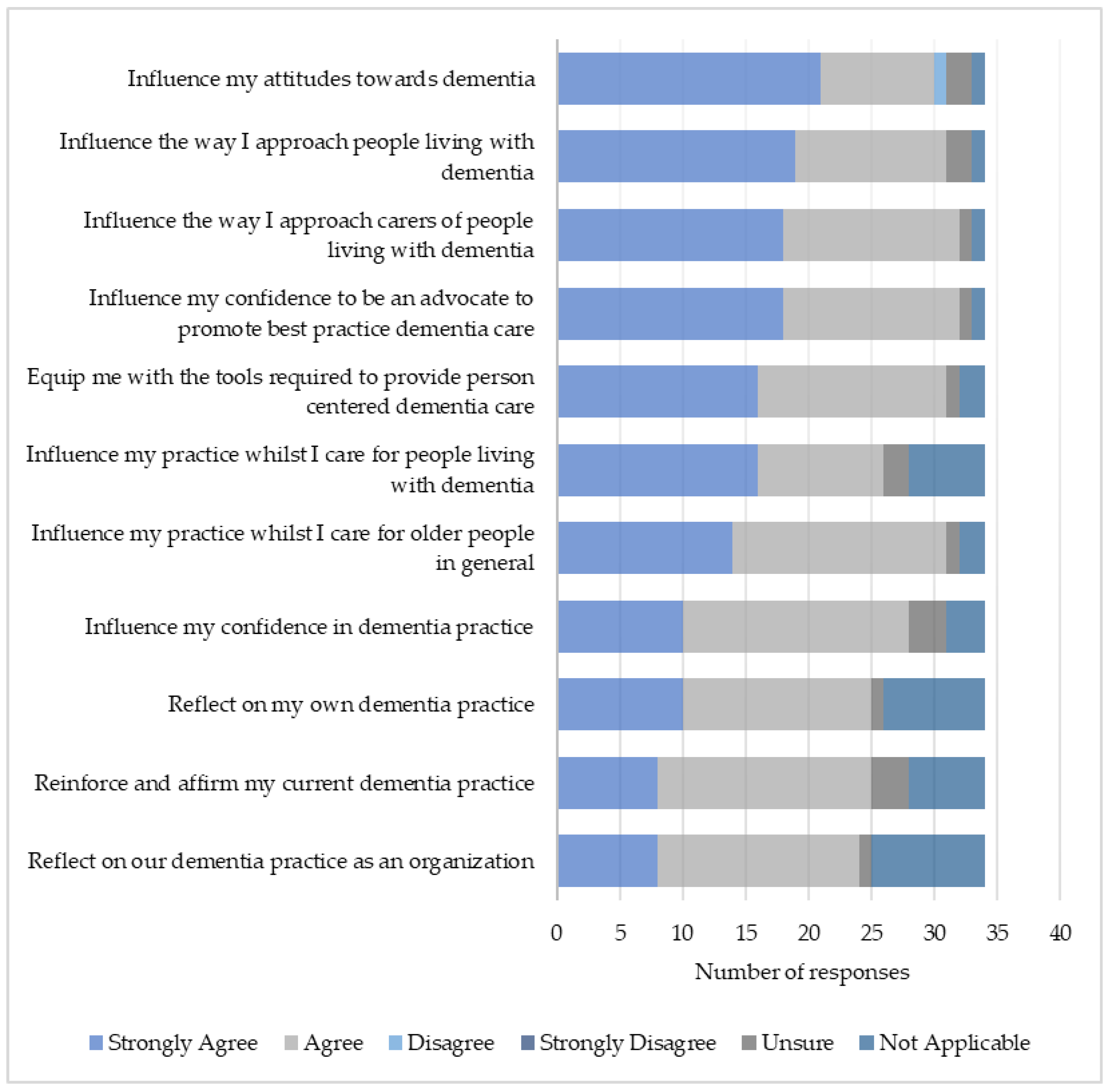

3.9. Level 3: Practice-Based Behavioral Change

There were high levels of agreement that learning in DEWE had resulted in positive behaviors in practice [

Figure 8].

3.10. Level 4: Results

Following DEWE, participants were motivated to lead or influence dementia practice. Several were interested in leading dementia education through teaching and the development of educational initiatives:

I would like to influence the way nurses learn and practice dementia care [93011072, Educator].

Participants were also motivated to share knowledge gained and improve awareness and attitudes towards the condition:

I would like to help change the attitudes of some carers and give them a confidence boost and help them with their knowledge [81126963, Practitioner]

The training motivated participants to lead improvements in person-centered dementia care, communication with people living with dementia, and support for family members and carers affected by dementia. Specific areas of dementia practice that participants sought to change included dementia assessment, delirium awareness, management of stress and distress, implementation of dementia inclusive environments, pain management, and palliative care.

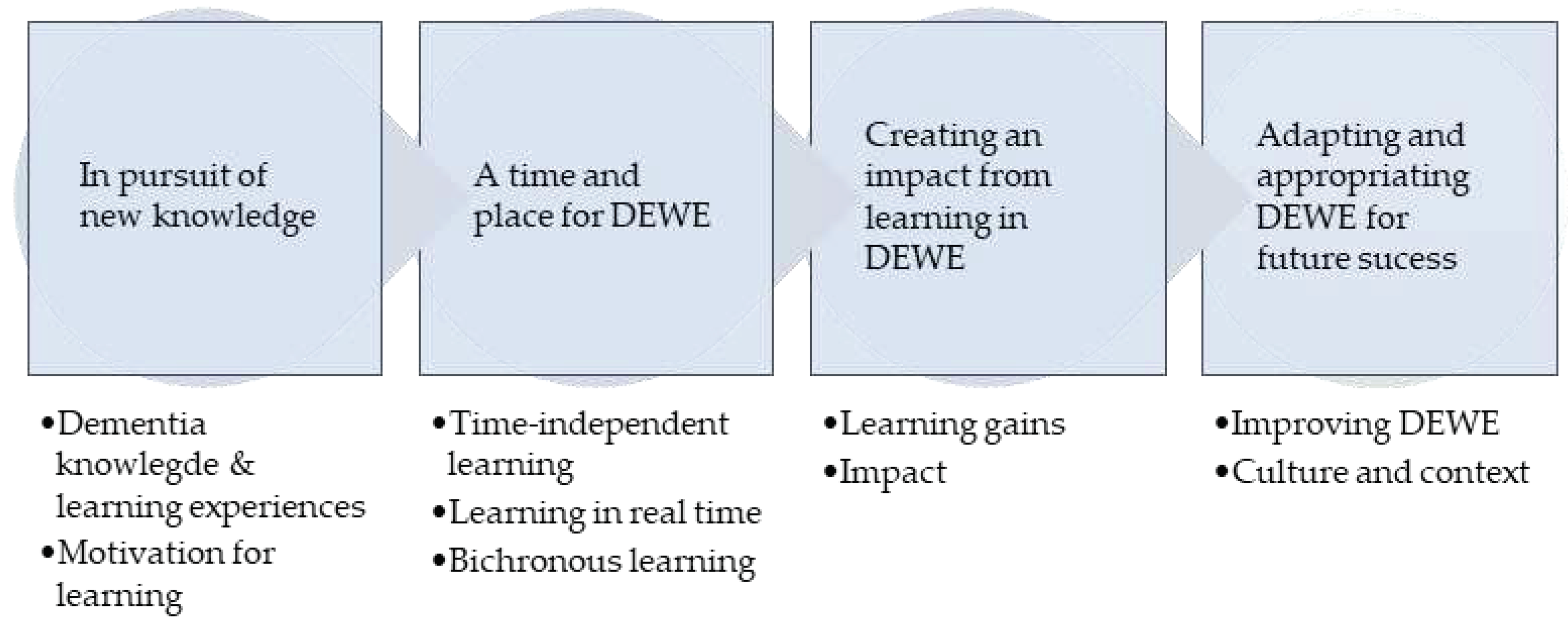

6. Discussion

Dementia training that is dependent on learner-initiated asynchronous instruction involving episodic or standardized elements of care often fail to accurately depict the trajectory of the illness and risks assumptions that such criteria are ubiquitous to the dementia syndrome [

29]. One might also presume that such training has the potential to inadvertently introduce unconscious negative bias and reinforce stigma when certain training packages, e.g., Management of Stress & Distress, are recommended as mandatory dementia training. Such an approach unfortunately does not seem to help practitioners understand dementia as a neurodegenerative disorder and the complexities associated with the progression of the disease. Acknowledging the inherent uniqueness of the dementia trajectory for each person ensured that DEWE prioritized and enabled learning for participants to see the person behind the illness rather than the condition itself or focus on managing isolated behaviors associated with the condition [

30]. DEWE, as both a unique and comprehensive dementia training program, used a “journey-based approach” to help participants to appreciate the essentials, priorities, and enablers for high-quality person and relationship-centered dementia care.

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted a shift in educational delivery and transition to online programs which was particularly notable in India where e-learning has only started to gain popularity [

31]. DEWE was developed during the pandemic to provide dementia education through a balance of flexibility (asynchronous workbooks) and immediacy (synchronous sessions). Previous research has demonstrated that the combination of asynchronous and synchronous (bichronous) online learning has several advantages including improved learning outcomes [

17].

Asynchronous workbooks provided participants with access to dementia education at any time and place. Convenience and flexibility are benefits of technology-enabled dementia education [

32,

33,

34]; however, asynchronous learning may result in feelings of isolation [

35]. DEWE implemented various active learning strategies to compensate the effects of learner isolation. Adherence to principles of adult learning [

36] combined with established motivating factors for participation, e.g., certification for learning [

37], optimized learner interest and enthusiasm. Feedback is an integral element of teaching and learning across educational delivery modes [

38,

39]. Formal assessment of learning in DEWE may indicate whether specified learning outcomes were achieved and enhance learner motivation by fostering engagement with course content [

40].

It is recommended that effective dementia education be relevant to the roles, experiences, and practices of learners, rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all approach [

41]. However, diverse and multidisciplinary learning cohorts are also known to be beneficial [

42]. DEWE replicated in-person teaching in synchronous sessions involving various practitioners and educators in real-time group discussions. This rich diversity of participants shared a passion for dementia and actively sought improvements in dementia care which led to a vibrant community of engagement and expertise [

43].

Online programs should be designed to focus on pedagogical issues which emphasize collaborative and case-based learning (CBL) [

31]. CBL aimed to connect theory and practice in both asynchronous and synchronous resources through emotional engagement with authentic clinical cases [

44]. CBL using actual learner experience is aligned with the experiential learning model [

45]. Greater emphasis on participants’ direct experience may develop higher order thinking whilst encouraging group reflection and collaborative problem solving [

46]. Experience-based CBL during synchronous sessions could be enhanced using frameworks rooted in nursing processes to guide discussions and the effective articulation of cases [

47].

DEWE was deemed highly relevant to the participants' current practice; however, it fell short in addressing cultural differences between the UK and India. Both countries share many common goals, such as providing quality healthcare and addressing the needs of the growing elderly population [

48]. Culturally appropriate education is crucial in India to address the rising burden of dementia and effectively address the unique socio-economic, cultural, linguistic, geographical, and lifestyle characteristics of this population [

49]. Learner motivation can be enhanced where educational content includes references to national dementia prevalence, incidence, and related factors, along with information on local professional and community services [

50]. Incorporating relevant material is crucial as participants anticipate applying new knowledge locally in practice.

DEWE was enriched through involvement of individuals with lived experience of dementia and their family carers. Involvement in dementia education may foster a sense of worth and altruism among people with dementia and can provide carers with opportunities to share experiences and address caregiving challenges. The involvement of lived experience in DEWE fostered emotional connections with participants for deeper engagement [

51]. Engagement was further enhanced from expert facilitation and input from credible and relatable dementia care experts who served as positive dementia care role models [

52].

Surr [

41] suggested that the total duration of dementia education programs should be more than eight hours with individual sessions being at least 90 minutes. Limited evidence exists on the optimal duration for online synchronous sessions; however, during or after these sessions, learners often report feelings of fatigue [

53]. The average duration of synchronous sessions in DEWE was 82 minutes with most exceeding the 90-minute recommendation and were regularly interspaced with breakout opportunities. Nonetheless, the duration of synchronous sessions in future iterations of DEWE might be minimized to mitigate cognitive overload and learner fatigue.

Delivery via WebEx posed challenges to participants from India due to unfamiliarity with the platform. Engagement may have been further compromised as several participants used mobile phones to access DEWE. Mobile devices including smartphones are promising as learning devices due to their portability and ability to facilitate rapid information retrieval, collaborative interaction, and situated learning [

54]; however, mobile devices may not be ideal for online learning due to software compatibility issues and small screen size [

55].

Technical challenges and poor online etiquette can risk misunderstanding and miscommunication [

56]. Setting rules for online etiquette in synchronous sessions may encourage a sense of community and active participation amongst learners [

57]. In future courses, it will be important to provide 'netiquette' guidance in the first synchronous session with contingency plans to resolve potential technical issues. These enhancements will ensure that DEWE provides a seamless and efficient online learning experience.

6.1. Limitations

The survey did not include demographic information to establish the impact of training based on country of origin. Most (78%) interview participants were from India, which limited the extent to which findings can be interpreted and applied in the UK. Interviews were conducted up to 18 months following participation in the training resulting in potential recall bias.