1. Introduction

Unhealthy dietary choices have become a global public health concern, leading to poor health outcomes and an increased risk of diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [

1]. This has been influenced more by the widespread availability and marketing of less nutrient-dense foods [

2,

3]. The increased accessibility to processed foods specifically snacks from supermarket shopping has been identified as a contributor to poor dietary habits [

4] leading to a rise in overweight/obese (BMI>24.5kg/m

2) [

5,

6,

7]. Labeling has been an important tool for informing consumers about the nutritional composition of foods, allowing them to make informed decisions about their food. [

8,

9,

10].

In Tanzania, food labeling standards are regulated by the Tanzania Bureau of Standards (TBS) [

11]. The agency is responsible for adopting and enforcing labeling standards put by the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC), an international organization for developing food standards [

12]. However, individual nations have the autonomy to select what to include and what not to put on their standards, creating a disparity in labeling standards among countries [

13]. With the recent increase in international trade, and with labels being considered as a marketing tool, countries are recommended to adhere to all mandatory Codex requirements to ensure homogeneity in labeling and protecting consumers [

7].

However still, food product labels often lack completeness, and not all products conform to mandatory labeling requirements with challenges being persistent in Low-Middle Income Countries (LMICs) [

14,

15,

16]. Studies have highlighted deficiencies in the adherence of food products to International (Codex) food labeling standards [

17,

18]. A recent study from Nigeria revealed that only 30% of food products comply with these standards [

19]. This non-compliance with labeling standards hampers consumers’ ability to make informed choices, potentially contributing to unhealthy dietary practices [

20]. The significance of proper food labeling is ever more important because consumption of pre-packaged foods has become increasingly common, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, and has been associated with a rise in NCDs [

15]. In response to this growing health concern, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the Global Action Plan for Prevention and Control of NCDs (2013-2020) strategies. Among the proposed strategies, the enforcement of food labeling, including Front of Pack Nutrition Labeling (FoPL), was suggested as a cost-effective approach to mitigate the impact of unhealthy diets [

18]. Additionally, for Tanzania to participate in international trade, adherence to international labeling standards is not only necessary but also a key marketing strategy [

21].

Despite the WHO recommendation, and the given health and economical role of food labels, there remains a scarcity of research evaluating adherence to food labeling among pre-packaged products in Tanzania. Therefore, this study aims to address this] research gap by examining the extent of adherence to food labeling standards in Tanzania, encompassing both local and international standards. The investigation will focus on pre-packaged snacks available in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s largest city.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a cross-sectional study involving the assessment of labels of 180 pre-packaged snacks collected from supermarkets and mini-stores of the five districts in Dar es Salaam. Dar es Salaam a center for trade with a wide range of manufacturing industries and an international harbor allowing for diverse availability and entry of pre-packaged foods made a justifiable setting for conducting the study [

22,

23].

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Pre-packaged snacks with and without labels falling under the Codex categorization of Bakery (e.g., Cakes, sweet biscuits and pastries, other sweet bakery products), ready-to-eat savory snacks Potato, cereal or starch-based (crisps, chips, and crackers), Confectionaries (chocolate, sweets, sweet toppings, energy bars, and desserts), and Sweetened Beverages (soda, energy drinks, milk, and dairy products) were eligible for the study [

24]. Snacks with fainted fonts and those with prices above the average Tanzania daily individual earning were not included in the study.

2.3. Sampling Strategy

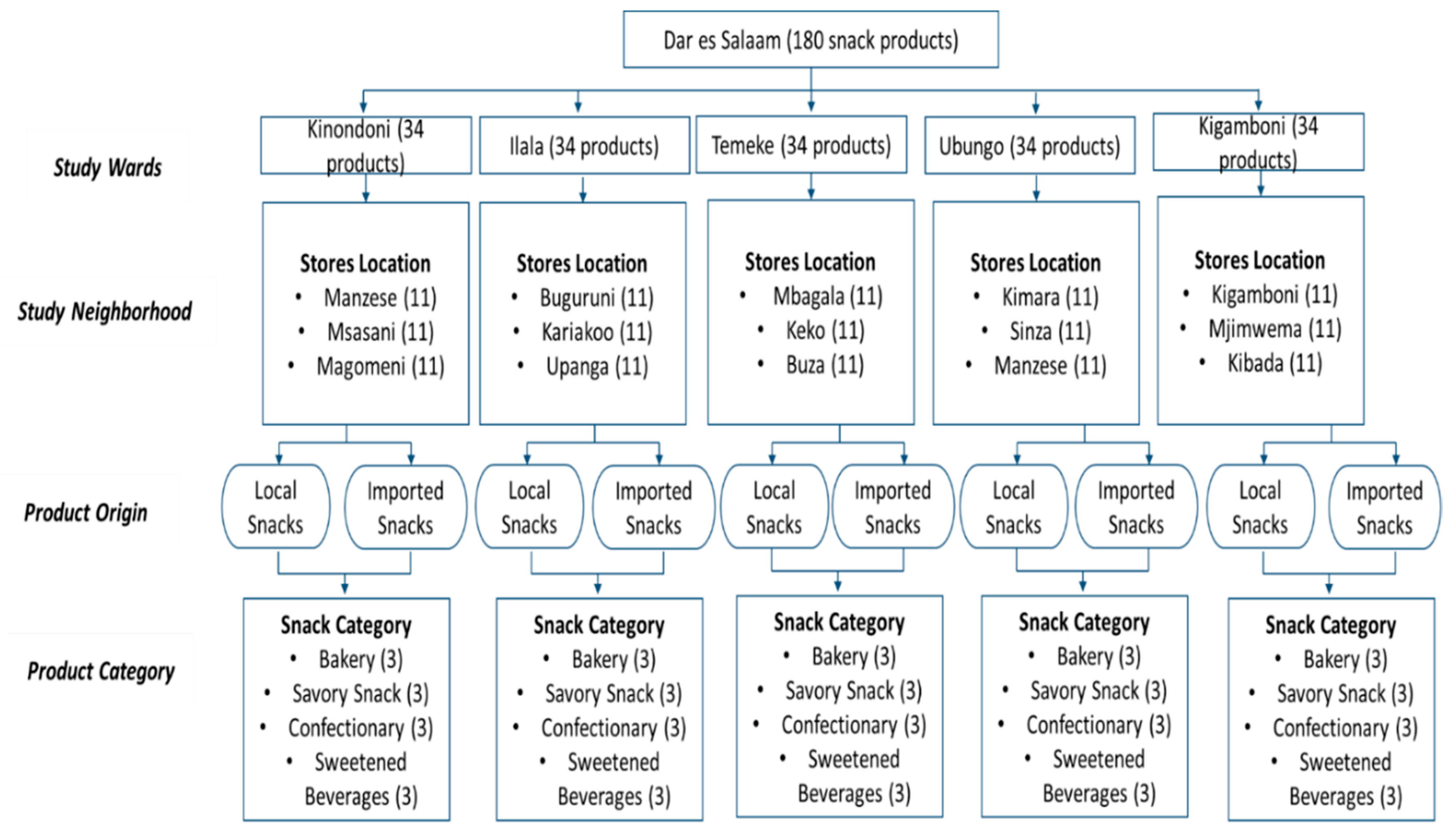

In this study, we utilized the sampling protocols jointly developed by WHO and Resolve to save lives for rapid assessment of trans-fatty acids (TFA) in edible oils and foods [

25,

26]. A complete list of registered supermarkets, mini-stores, and regularly purchased snacks within each ward was obtained from the ward marketing officer. Stratified cluster sampling was done where five districts of Dar es Salaam were considered as strata that included Kinondoni, Ilala, Temeke, Ubungo, and Kigamboni districts. Each stratum was then clustered into wards, where three wards were randomly selected for the study. Within each ward, a total of ten mini-stores and supermarkets were randomly selected. Based on the regularity of purchase, simple random sampling was used for the selection of each snack category within shelves and rows of supermarkets and stores. Although this form of probability sampling is time-consuming, it is one of the most reliable methods for eliminating selection bias as stated in a study by Maheshwari, 2017 [

27]. The approach used is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.4. Data Collection

An electronic checklist from Kobo Tool software that included all the Tanzania and International mandatory labeling requirements was used. To allow for data cleaning and avoiding missing information data was regularly transferred into Microsoft Excel software, and cross-checked for consistency and completeness before they were exported to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for analysis.

Snacks were categorized into fully adherent, and partially adherent. Although specific cut-off points are not available for categorizing product level of adherence, categorization was designed to align with the number of Codex and Tanzania mandatory label requirements stipulated in a previous study [

11,

24]. A product was considered fully adherent if it contained all ten (10) or thirteen (13) mandatory food labeling requirements from Tanzanian and international food standards respectively and partially adherence if it missed at least one of the mandatory food labeling requirements. Completeness in labeling nutritional information was inferred if a product labeled all seven essential nutrients (Energy, Carbohydrate, Sugar, Protein, Fat, Saturated Fat, and Salt/Sodium) recommended by Codex guideline on nutritional labeling.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data was exported from Excel to Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 23 computer software program for analysis. Statistical significance was set at a p-value of 5%. Categorical variables were presented using frequencies and proportions. Descriptive statistics were done to assess the proportion of local and imported snacks that adhered to both Tanzania and International labeling standards and also on product categories to investigate which snack categories adhered more to labeling standards. To assess for an association between product factors (product origin, snack category, purchase location, and package size) and level of adherence to International (Codex) labeling standards, a Pearson’s Chi-square test was done. Factors with p-value <0.05 were further subjected to multivariable logistic regression analysis to assess for independent association.

3. Results

3.1. Product Characteristics

A total of 180 snacks from 165 stores and supermarkets were included in the study. Majority of the products were local snacks 94 (52%), where an even number of snacks were assessed 45 (27.3%) (

Table 1)

3.2. Adherence to Labeling Standards among Snacks Products

Majority of products 82 (46%) were found to fully adhere to Tanzania’s labeling requirements (

Figure 2a), while only 60 (33%) fully complied with international (Codex) requirements (

Figure 2b).

When examining the components of the labels, it was observed that the brand name was the most commonly available information on all product labels. However, some essential components such as Quantitative Ingredient Declaration (QUID) 85 (47%), instruction of use 79 (44%) and the International labeling requirement of allergen information 87 (48.5%), were notably missing.

3.3. Adherence to Labeling Standard Based on Product Origin

The majority of imported snacks (53%) were found to fully adhere to Tanzania’s labeling standards, compared to just 34% of local products achieving full compliance (

Figure 3a). In terms of adherence to international labeling standards, 48% of imported products fully met the Codex Alimentarius Commission’s standards, significantly higher than the mere 15% of locally produced products that attained full adherence (

Figure 3b).

3.4. Adherence to Labeling Standard Based on Product Category

In the adherence to labeling standards based on product category, both baked snacks and confectioneries showed a high level of compliance with Tanzania’s labeling standard, with each category registering 53% of products in full adherence (

Figure 4a). Confectioneries stood out in terms of adherence to the Codex standards, with 66% of these products fully complying (

Figure 4b). In contrast, savory snacks were identified as the category with the lowest adherence to both Tanzania and Codex labeling standards (

Figure 4a & 4b).

3.5. Language and Expiration Date Position

Out of the 180 products, more than half 110 (66.7%) of the products used English language for labeling. Similarly, among the 94 local products, only 14 (19.7 %) of products used the Swahili language. However, the use of English along with other languages (Arabic, Greek, Turkey, etc.) was seen in 39 (41.5%), with most being found among imported products. Regarding the inclusion of expiry (best before) dates, all the products in the study had this information. However, the positioning of the expiry date on the packaging varied among the products. Approximately 103 (57%) of the products highlighted the expiry date prominently at the top or in front of their packaging.

3.6. Adherence to the Nutrition Declaration

Out of the total products studied, the majority, 113 (68.5%), had complete nutrition declarations. More than a third quarter of imported products 83 (86%) completed their nutrition declarations, with less than half 30 (42.3%) of local products fully presenting that information (

Figure 5).

When comparing different snack categories, bakery snacks had an impressive proportion of 43 (96%) for having complete nutrition information. On the other hand, savory snacks had the lowest proportion, 22 (48%), of presenting complete nutrition information.

3.7. Nutrition Profiling Schemes

Regarding the presentation of nutrition labeling components, a greater number of product labels 106 (59%), displayed their information using the Back of Pack Labeling (BoPL) format. In contrast, a smaller proportion, 74(41%)) employed one or more of Front of Pack nutrition Labeling (FoPL) format. Notably, the majority of products using FoPL labeling, 64%, were imported products (

Figure 6).

3.8. Product-Related Factors Associated with Adherence to International Labeling Standards

Product category (p-value < 0.024), product origin (p-value < 0.001), and package size (p-value < 0.016) exhibited statistically significant associations with adherence to Tanzania labeling standards. However, after adjusting for confounders, package size, and product origin demonstrated an independent association with adherence to International labeling standards. Specifically, imported ([aOR]=3.24; 95% [CI]=2.84-7.52) and medium-sized packages ([aOR]=4.09; 95% [CI]=1.23 - 10.9) were more adherent to International Standard compared to local and small-sized packages respectively (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

Food labels serve as a critical tool for promoting healthier food choices, contributing to the global effort to promote healthier food choices, enhance food safety, and mitigate the escalating crisis of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs). Our study, while focused on Tanzania, taps into a universal challenge, reflecting a scenario prevalent in many parts of the world, particularly in low- and middle-income countries that are undergoing rapid urbanization and dietary transitions. Our findings offer valuable insights into the complexities and challenges of implementing effective food labeling practices – a concern that resonates globally, given the World Health Organization’s (WHO) drive for mandatory labeling and Front of nutrition Pack Labeling (FoPL) as key strategies in the worldwide fight against NCDs [

18].

Our findings indicate a notable adherence to Tanzanian labeling standards among snack products, though adherence to International (Codex) standards was less prevalent, echoing similar observations in other African regions. Studies by Kokobe et al. [

28] in Ethiopia and Nigerian research [

19] also reported higher compliance among imported products compared to local ones. This discrepancy highlights a critical need for increased investment in labeling education and awareness, particularly targeting local micro-food producers.

The variation in adherence across snack categories, with poorer performance in savory snacks as noted in our study, is similar to findings from a meta-analysis across European countries [

29]. This disparity is likely due to differences in manufacturing practices, with larger industries typically adhering more strictly to regulations [

30]. This suggests a need for more robust regulation and support for smaller-scale producers, who often contribute to the savory snacks category.

Another significant concern observed in our study, is the incomplete adherence to mandatory labeling requirements, particularly the lack of essential information such as ingredient lists, usage instructions, and allergen information. While the missing information might not be viewed as particularly important, this gap in labeling poses a health risk, as illustrated by Dumoitier et al. [

31] and a Canadian study linking missing allergen information to increased accidental allergic reactions [

32].

We also found that the majority of labels used English, with limited use of Kiswahili, raising concerns about consumer comprehension. Given that a substantial portion of Tanzania’s population is more proficient in Kiswahili, this finding underscores the importance of language translation and localization in labeling, as emphasized in most studies [

33,

34]. Additionally, our analysis also revealed that FoPL, despite being recommended by WHO, was not widely employed. This contrasts with studies in regions like the United Kingdom, where FoPL is more commonly used [

35,

36]. The inconsistent use of FoPL, which is not a mandatory requirement by the Codex Commission, allows manufacturers to conceal nutritional information, potentially misleading consumers.

Factors such as product origin and package size significantly influenced adherence to labeling standards, with imported products and those with large packages, complying as compared to local and small packaged snacks respectively. This finding aligns with research conducted in Malaysia [

37,

38], suggesting that smaller packages and locally produced snacks tend to have lower compliance rates. This emphasizes the need for stricter scrutiny of labeling practices, particularly for local and smaller packaged products.

However, our study is not without limitations. Despite sampling the most popular snacks, the focus on only four snack categories may not fully represent the diversity of snacks available, highlighting the need for broader research. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits our ability to capture dynamic trends or changes in labeling regulations and practices which are currently common.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, while Tanzania shows promising progress in food labeling practices, considerable efforts are still needed to achieve full compliance with mandatory standards, particularly among locally produced products. Emphasis on using Kiswahili for labeling and enforcing policies for FoPL implementation is crucial. Strengthening regulatory frameworks and enhancing support for small-scale producers will be key to improving food labeling standards aiding consumers in making informed healthier food choices and ultimately contributing to the reduction of Non-Communicable diseases.

Author Contributions

H.J.R was involved in conceptualizing and designing the study, data collection, data analysis, and writing the manuscript A.E was involved in drafting the manuscript, Z.K. and F.M. were involved in conceptualizing and supervising the study as well as reviewing and finalizing the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review of Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Science Board (Reference No.DA.282/298/01.C/1802, July 2023)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank all supermarket and mini-store managers who agreed to engage their stores in the study. Special thanks are addressed to Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Science physiology department members for their external support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abegunde DO, Mathers CD, Adam T, Ortegon M, Strong K. The burden and costs of chronic diseases in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1929–38. [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew S, Coyle D, McKenzie B, Vu D, Lim SC, Berasi K, et al. A review of front-of-pack nutrition labelling in Southeast Asia: Industry interference, lessons learned, and future directions. Lancet Reg Heal - Southeast Asia. 2022;3: 100017. [CrossRef]

- Branca F, Lartey A, Oenema S, Aguayo V, Stordalen GA, Richardson R, et al. Transforming the food system to fight non-communicable diseases. BMJ. 2019;364.

- Thrimavithana, A. Snacking Behavior, Its Determinants and Association with Nutritional Status Among Early Adolescents in Schools of Galle Municipality Area Snacking Behavior, Its Determinants and Association with Nutritional Status Among Early Adolescents in Schools of G. 2023.

- Rischke R, Kimenju SC, Klasen S, Qaim M. Supermarkets and food consumption patterns: The case of small towns in Kenya. Food Policy. 2015;52: 9–21. [CrossRef]

- Gibney MJ, Forde CG, Mullally D, Gibney ER. Ultra-processed foods in human health: A critical appraisal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(3):717–24. [CrossRef]

- Martini D, Menozzi D. Food Labeling: Analysis, Understanding, and Perception. Nutrients. 2021;13(1):1–5. [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAO publications catalogue 2022. FAO Publ Cat 2022 [Internet]. 2022 Oct 18. [cited 2023 Mar 13]; Available from: http://www.fao.org/food-labelling/en.

- Blaine RE, Kachurak A, Davison KK, Klabunde R, Fisher JO. Food parenting and child snacking: A systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1). [CrossRef]

- Annette McDermott. 9 Low-Carb Snack Recipes [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/food-nutrition/low-carb-snacks.

- Tanzania Bureau of Standards. Formulation of Standards. TBS [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2022 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.tbs.go.tz/pages/formulation-of-standards.

- Codex Alimentarius. Food safety and quality. Food and Agriculture Organization. [Internet] [cited2023Jul26]. Availablefrom:https://www.fao.org/food-safety/food-control-systems/policy-and-legal-frameworks/codex-alimentarius/en.

- Albert, J. Introduction to innovations in food labelling. In: Innovations in Food Labelling. Elsevier Ltd.; 2009. p. 1–4.

- FAO.FAO publications catalogue. [Internet]. FAO publications catalogue 2021. FAO; 2021 [cited 2022 Sep 18]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/food-labelling/en.

- Alan, T. Prepacked food labelling: Past, present and future. Br Food J. 1995;97(5):23–31.

- Packer J, Russell SJ, Ridout D, Hope S, Conolly A, Jessop C, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of front of pack labels: Findings from an online randomised-controlled experiment in a representative British sample. Nutrients. 2021;13(3):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Sacks G, Veerman JL, Moodie M, Swinburn B. Traffic-light nutrition labelling and junk-food tax: A modelled comparison of cost-effectiveness for obesity prevention. Int J Obes. 2011;35(7):1001–9.

- Madsen CB, van den Dungen MW, Cochrane S, Houben GF, Knibb RC, Knulst AC, et al. Can we define a level of protection for allergic consumers that everyone can accept? Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2020;117. Okoruwa A. CN. Review of Food Safety Policy in Nigeria. J Law, Policy Glob. 2021 Jun.

- Martinelli, K. The Importance of Food Labels [Internet]. High Speed Training. 2018 [cited 2022 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.highspeedtraining.co.uk/hub/importance-of-food-labels/.

- Achentalika HTS, Msuya DT. Competitiveness of East African Exports: A Constant Market Share Analysis. In 2022. p. 213–38.

- Tanzania Ports Authority. Dar es Salaam Port [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2023 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.ports.go.tz/index.php/en/dar-es-salaam-port.

- Britannica. Dar es Salaam | History, Population, & Facts | Britannica [Internet]. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2023[cited 2023 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/place/Dar-es-Salaam.

- CODEX. Codex general standard for the labelling of prepackaged foods. CODEX STAN 1-1985, Revis 1-1991 [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2022 Oct 10];1–7. Available from: https://www.fao.org/3/Y2770E/y2770e02.htm.

- WHO. REPLACE transfat: an action package to eliminate industrially produced trans-fatty acids. World Heal Organ [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Dec 10];1–8. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/324823.

- Mashili F, Rusobya H, Masaulwa J, Shonyella C, Kaushik L. Assessment of Trans Fatty Acid Levels in Popular Edible Oils and Fried Foods: Implications for Public Health in Tanzania. Preprints. 2023.

- Maheshwri, V. Fundamental Concepts of Research Methodology. 2017. p. 2.

- Kokobe T, Marew T, Fenta TG. Compliance of Pre-Packed Juice to Labelling Requirements and Use of Food Labelling Information for Purchasing Decision Among Consumers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Pharm J. 2022;37(1):65–76.

- El-Abbadi NH, Taylor SF, Micha R, Blumberg JB. Nutrient Profiling Systems, Front of Pack Labeling, and Consumer Behavior. Vol. 22, Current Atherosclerosis Reports. Curr Atheroscler Rep; 2020.

- Howarth, S. Food labelling beyond EU borders. Food Sci Technol [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2023May26];31(3):446. Availablefrom:https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/fsat.3103_11.

- Fuduric M, Varga A, Horvat S, Skare V. The ways we perceive: A comparative analysis of manufacturer brands and private labels using implicit and explicit measures. J Bus Res. 2022; 142:221–41. [CrossRef]

- Dall’Asta M, Angelino D, Pellegrini N, Martini D. The nutritional quality of organic and conventional food products sold in italy: Results from the food labelling of italian products (flip) study. Nutrients. 2020;12(5). [CrossRef]

- Sheth SS, Waserman S, Kagan R, Alizadehfar R, Primeau MN, Elliot S, et al. Role of food labels in accidental exposures in food-allergic individuals in Canada. Ann Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2010;104(1):60–5. [CrossRef]

- Silveira BM, Gonzalez-Chica DA, Da Costa Proença RP. Reporting of trans-fat on labels of Brazilian food products. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(12):2146–53. [CrossRef]

- Bacarella S, Altamore L, Valdesi V, Chironi S, Ingrassia M. Importance of food labeling as a means of information and traceability according to consumers. Adv Hortic Sci. 2015;29(2–3):145–51.

- Dynamic. Importance of Food Label and Packaging Translation | Dynamic Language [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jul 26]. Availablefrom:https://www.dynamiclanguage.com/the-importance-of-food-label-and-packaging-translation.

- Ogundijo DA, Tas AA, Onarinde BA. An assessment of nutrition information on front of pack labels and healthiness of foods in the United Kingdom retail market. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Othman Y, Hasan Z, Mustafa MS, Mustafa A, Mahat IR, Malib MA. Assessing Snack Food Manufacturers’ Conformity to the Law On Food Labelling. Int J Accounting, Financ Bus. 2021;6(33):197–206.

- Wilson NLW, Rickard BJ, Saputo R, Ho ST. Food waste: The role of date labels, package size, and product category. Food Qual Prefer. 2017; 55:35–44. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).