1. Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common microvascular complication of diabetes, with an estimated prevalence of about one in four diabetic patients [

1]. IDF estimated the number of diabetic patients worldwide will reach 700 million by 2045 [

2]. Although some reports indicate that the risk of diabetic patients developing new DR is decreasing, the number of patients with sight-threatening DR (i.e., proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) OR diabetic macular edema (DME)), is estimated to reach 44.82 million by 2045 [

3].

Significant advances have been made in the treatment of DR over the past 30 years, and timely treatment can greatly reduce the risk of blindness or severe and irreversible visual impairment. However, there are still cases of irreversible vision loss, and the reasons for this include the lack of subjective symptoms in the early stages of DR, which delays the detection of DR. In the shadow of progress in DR care, the remaining challenge is to detect DR early enough to secure access to effective treatment. The disease burden of diabetes and DR remains weighty, and early detection of DR by screening program is one of the strategies to counteract this burden [

4].

This article aims to provide a review on the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) for automated diagnosis models and other potential use cases. In considering the use and challenges of using AI automated diagnostic models for DR, this paper first provides an overview of screening for DR from historical perspective, then describes the types of screening for which AI automated diagnostic models have been developed, and finally describes how AI automated diagnostic models can be used for screening for DR in Japan. Finally, we will discuss how large language models (LLMs) can be used for the management and a total healthcare for DR in Japan.

2. Why DR needs to be screened, and how?

As shown in

Table 1, diabetic retinopathy meets the criteria for screening DR. Since the St. Vincent Declaration (1990) to the Liverpool Declaration (2005) and further conferences by the screening for diabetic retinopathy in Europe [

5]. The Liverpool Declaration encouraged European countries to establish systematic screening to reduce the risk of visual impairment due to diabetic retinopathy by 2010 by: (1) systematic programs of screening reaching at least 80% of the population with diabetes; (2) using trained professionals and personnel; (3) universal access to laser therapy. Further meetings have been held and recommended that screening for DR be shifted from opportunistic screening to systemic screening, un-organized to organized systematic screening, which has been started to be implemented in some countries.

An example of systematic screening implemented country wide is a screening program of the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom [

6]. This is based on the strategy from the St. Vincent declaration, a four-stage concept that advocates the development of stepwise screening for DR (

Table 2).

A path to establish systematic or organized screening consists of further five components as presented in

Table 3. Following these components, Japan’s situation can be reviewed as below:

2.1. Screening pathway

“A pathway for DR screening should be in place, rather than the test being carried out in isolation.”

In Japan, current DR screening is provided two-fold (

Figure 1); the first pathway is the national health screening program, and the second path is a referral from physicians to ophthalmologists. The first pathway is built in the national systematic screening program to detect diabetes in Japan, called the specific health checkups (“Tokutei-Kenko-Shinsa”) [

7]. This is a nation-wide program for persons aged 40-74 years old under the health insurance and includes a screening of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.

2.2. Guidelines

The first pathway of the national systematic screening program for diabetes is conduced as the national screening program. This screening scheme is refined every 5 years, and the screening for DR has been recommended since the revision in 2018. There are no official grading protocols for DR defined in the health screening programs. However, there have been grading manuals and suggested recommendation published from he Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare [

8] [refs] (which adopts a classification of simple DR, pre-proliferative DR and PDR), the Japanese Society of Cardiovascular Disease Prevention [

9] and the Japan Society for Ningen Dock [

10] (these two adopts the international classification [

11]). For the second pathway, the clinical guideline for DR in Japan recommends that when a patient is diagnosed with diabetes, he/she should be referred to an ophthalmologist to be screened for DR yearly [

12]

2.3. Quality standard

There are no quality standards for the two pathways of the DR screening in Japan. The first path of DR screening in the national screening program is not mandatory and no clear quality standards are set. The second pathway of the referral from physicians to ophthalmologists is recommended but no standards are defined. As a result of this opportunistic approach, the uptake of DR screening is estimated to be remained low.

2.4. Information system and monitoring

There are no dedicated information system and monitoring for both DR screening pathways. Japan has a national level health insurance scheme, and the National Database (NDB) captures more than 95% of the screening linked to this health insurance scheme and clinical claims in Japan. Because the DR screening is not a mandatory component of the health screening program, reported numbers are not useful to monitor the screening uptake. For the second path of clinical referrals, Ihana-Sugiyama et al. reported that the only half of the patients who are under treatment for diabetes had fundus examination done in NDB database [

13].

In summary, Japan has DR screening in place via two pathways as a part of the national screening for diabetes and referrals between physicians and ophthalmologists; they are both still unsystematic and predominantly carried out by motivated ophthalmologists and health organizations. Although it was not discussed in this manuscript in details, there are secured access to the ophthalmologists (10.35 ophthalmologists per 100,000 population) and DR treatment in Japan. It remains a need to provide policy makers and stake holders in the health insurance and health screening program with importance and challenges of DR screening so that more systematic screening be offered in Japan.

3. Emerging AI technologies that can be applied to DR screening

3.1. Image classification for diagnostic support.

To realize systematic screening, which requires large amount of grading workload, many projects have been attempting to automate DR screening since the 1990s. Early approaches to automated screening used image processing filters so that they can process images step-by-step, e.g., firstly, an image processing to exclude areas of non-retinopathy lesions (e.g., optic nerve papillae and blood vessels). Secondly, the process to detect red lesions (e.g., retinal hemorrhages) and yellow/white lesions (e.g., hard white spots and soft white spots). Those attempts have achieved sensitivity and specificity at 80% and 80%, respectively [

14].

A milestone that changed the situation was a series of research using deep learning to classify color fundus images to identify DR since 2016 [

15]. As an automatic judgment model for fundus images using deep learning, it was trained based on screening images and judgment results performed in the past and reached a level of sensitivity and specificity exceeding 90% at the same time, which became a hot topic. Subsequently, as a prospective study, the accuracy was verified at several hospitals, and it was reported that the sensitivity and specificity of approximately 90% could be maintained [

16].

There are domestic research and companies to use automated grading of color fundus photographs using deep learning to assist in the diagnostic support of DR in Japan. DeepEyeVision Inc. [

17] has developed the original system and started a commercial service. This service aims to serve mainly for fundus photograph evaluation in the national health screening program.

Many other research projects and commercial services have been reported to date, and

Table 4 lists those that have been prospectively verified in actual cases. All of them are now at high levels of both sensitivity and specificity and can achieve sensitivity ≥ 80% and specificity ≥ 90%.

3.2. Generative AI and large language models

Since the release of ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) in 2022, large language models (LLMs) revealed its ability generating sentences and humanlike conversations with nuanced expression. The advent of LLM chatbots in use have been researched for various academic tasks such as medical examinations and expected to become a personal virtual assistant.

There are many potential examples of LLM applications in prevention and healthcare [

18]. From the patient's perspective, many attempts have already begun to provide virtual consultations to improve health in daily life, assist patients in deciding if they need to see a doctor, help them schedule an appointment to see a doctor, as well as explain difficult medical terms and record and consolidate health-related information. For healthcare professionals, the possibilities are great for creating medical records such as medical charts, surgical records, referral letters, discharge summaries, and handover documents, as well as for suggesting guideline-compliant treatment options and providing explanatory support to patients. It could facilitate the management, complementation, and utilization of health-related information with a high degree of personalization, scalability, and efficiency for both patients and health care providers. Caution should be taken before integrating these LLMs into existing health care systems, because it is essential to address concerns about their robustness and reliability, particularly regarding the potential for probabilistically derived, non-factual discourse known as hallucination. We need to be concerned about the situation where there is no medical professional available to verify the truth or falsity of the discourse generated by LLMs. Basically, we optimistically expect that these technical shortcomings will improve day by day. Until then, it is essential to include discussions on the effective and proper use of LLMs, including technical accuracy assessments, governance to ensure a path to maximize their functionality, and remaining safeguards to ensure their safety.

4. How can artificial intelligent be implemented effectively in diabetic retinopathy screening in Japan?

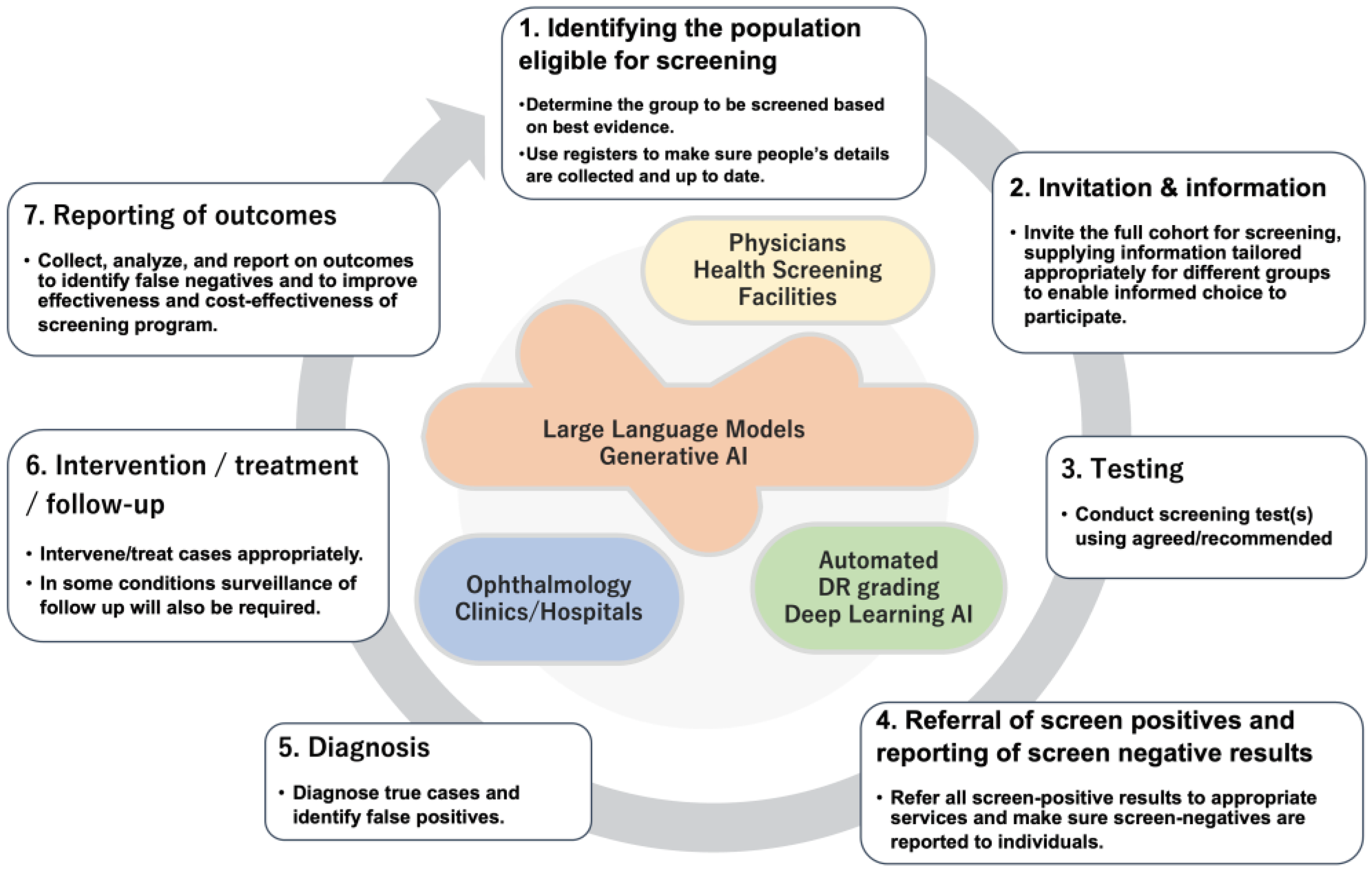

4.1. Seven steps towards systematic screening of DR

Automated DR screening system has truly increased the potential to deliver good quality screening for DR nationwide. To realize this, the automated screening needs to be integrated into a well design screening program and it turned out that a good quality automated grading system does not guarantee its success. As proposed by the Screening for Diabetic Retinopathy in Europe [

5], steps to establish a successful systematic screening can be break down to the 7 steps (

Figure 2).

4.2. How will it possible to fully utilize the capacity of automated grading systems for DR?

Automated DR screening system will surely contribute to enhance the step for “

Testing” (

Figure 2). By adopting automated AI based grading as a screening test, it has a benefit to secure reproducibility especially not concerning about an inter-rater agreement. It will also speed up the turnaround from the image capture to a reporting of the results. The first pathway of DR screening in the national health screening has a target population with diabetes of 1.5 to 3 million every year. To provide timely and accurate grading of the fundus images, automated DR screening program will contribute. However, this emerging technology is not integrated well in the screening program as a system, it will not become effective. As shown above, there are other steps before and after the “

Testing” step.

There is a study [

19] on a demonstration of an automated AI diagnosis system for DR conducted at 11 hospitals in Thailand. They used the state-of-the-art system developed by the research group of Google and Verily. In Thailand, systematic screening for DR is conducted by taking fundus photographs of diabetic patients when they visit a physician; as the number of ophthalmologists is limited, the images are sent to the ophthalmologists, and they report the results after reviewing them. The introduction of an automated system was expected to reduce the time required to obtain test results from 2-10 weeks to 10 minutes. The implementation was not as expected due to the multiple factors from unstable communication infrastructure, ungradable quality images and, above all, the human factors of the intervening screening staff and patients. It was shown that, even the best quality automated grading program for DR does not necessarily work well as a system.

4.3. How will LLMs can contribute to the screening system of DR in the steps of systematic screening perform?

In the context of DR screening, the potential applications of LLMs can fill in the gap between the 7 steps to implement systematic screening (

Figure 2). The ability to generate personalized letter can be utilized to prepare “Invitation and Information”. Personalized letter considering each person’s situation and readiness may encourage and motivate eligible person to regularly undertake DR screening. After automated DR grading successfully process retinal images, the grading output can be generated as a natural language so that it can achieve automated “Referral of screen positives and reporting of screen negative results”. As mentioned above, LLMs can be utilized to support “Diagnosis” and “Intervention” by supporting medical records and guideline compliant decision making. “Reporting of outcomes” will be also supported by LLMs by automated personalized referral letters or patient explanations.

5. Conclusions

This review tried to illustrate how screening for DR in Japan is conducted and also identify what area should be focused further to achieve quality systemic screening program. The use of automated grading system with AI will boost the capacity to realize systematic screening in Japan, and in other contexts, by enabling fast and reproducible grading and soon replace primary screening task. Generative AI will connect the disrupted flow in the loop of systematic screening in identification and invitation of eligible persons, through referrals and reporting. For the future design of systematic DR screening, digital transformation including automated DR grading and personalized assistance with LLMs will be essential to be integrated in the loop. The most important factor in enabling such next-generation systematic screening is leadership by healthcare professionals, including all stakeholders, ophthalmologists, internists, diabetes specialists and patients living with diabetes.

“Technology makes possibilities. Design makes solutions. Art makes questions. Leadership makes actions.” - John Maeda [

20]

This statement offers suggestions on how new technologies can be applied to social implementations. No matter how much potential a new technology has, it must be designed to be utilized, and leadership is required to continue to ask questions and act toward social implementation. This reemphasizes the need for ophthalmic healthcare providers to take leadership to resolve the longstanding challenge of DR screening without resting on their advantage in preventing and treatment of DR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and writing: R.K.

Funding

This research was funded by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Japan) 22H03353 and 22K19671.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Those who wants to request data can contact the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, Lamoureux EL, Kowalski JW, Bek T, Chen SJ, Dekker JM, Fletcher A, Grauslund J, Haffner S, Hamman RF, Ikram MK, Kayama T, Klein BE, Klein R, Krishnaiah S, Mayurasakorn K, O'Hare JP, Orchard TJ, Porta M, Rema M, Roy MS, Sharma T, Shaw J, Taylor H, Tielsch JM, Varma R, Wang JJ, Wang N, West S, Xu L, Yasuda M, Zhang X, Mitchell P, Wong TY; Meta-Analysis for Eye Disease (META-EYE) Study Group. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):556-64. [CrossRef]

- Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, Colagiuri S, Guariguata L, Motala AA, Ogurtsova K, Shaw JE, Bright D, Williams R; IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. [CrossRef]

- Teo ZL, Tham YC, Yu M, et al. Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(11):1580–91. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Col- laborators. Causes of blindness and vision impair- ment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the Right to Sight: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(2):e144–60.

- The Screening for Diabetic Retinopathy in Europe web site. http://www.drscreening2005.org.uk/contact_email.html (Last accessed Jan 1, 2024).

- Garvican, L., Clowes, J. and Gillow, T. Preservation of sight in diabetes: developing a national risk reduction programme. Diabetic Medicine, 2000;17: 627-634. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. Specific Health Checkups and Specific Health Guidance. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000161103.html (In Japanese) (Last accessed Jan 1, 2024).

- Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. Specific Health Checkups and Specific Health Guidance. Related documents. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/001172504.pdf (In Japanese) (Last accessed Jan 1, 2024).

- Japanese Society of Cardiovascular Disease Prevention web site. https://www.jacd.info/method/index.html (In Japanese) (Last accessed Jan 1, 2024).

- Japan Society for Ningen Dock web site. https://www.ningen-dock.jp/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Fundus-JSND.pdf (In Japanese) (Last accessed Jan 1, 2024).

- Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL 3rd, Klein RE, Lee PP, Agardh CD, Davis M, Dills D, Kampik A, Pararajasegaram R, Verdaguer JT; Global Diabetic Retinopathy Project Group. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(9):1677-82. [CrossRef]

- The Japanese Society of Ophthalmic Diabetology Clinical Guideline Committee. Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Practice Guidelines (1st Edition). Journal of Japanese Ophthalmological Society. 2020; 124 (12): 953-953.

- Ihana-Sugiyama N, Sugiyama T, Hirano T, Imai K, Ohsugi M, Kawasaki R, Murata T, Ogura Y, Ueki K, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T. Patient referral flow between physician and ophthalmologist visits for diabetic retinopathy screening among Japanese patients with diabetes: A retrospective cross-sectional cohort study using the National Database. J Diabetes Investig. 2023;14(7):883-892. [CrossRef]

- Nørgaard MF, Grauslund J. Automated Screening for Diabetic Retinopathy - A Systematic Review. Ophthalmic Res. 2018;60(1):9-17. [CrossRef]

- Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, Stumpe MC, Wu D, Narayanaswamy A, Venugopalan S, Widner K, Madams T, Cuadros J, Kim R, Raman R, Nelson PC, Mega JL, Webster DR. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm for Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy in Retinal Fundus Photographs. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2402-2410. [CrossRef]

- Gulshan V, Rajan RP, Widner K, Wu D, Wubbels P, Rhodes T, Whitehouse K, Coram M, Corrado G, Ramasamy K, Raman R, Peng L, Webster DR. Performance of a Deep-Learning Algorithm vs Manual Grading for Detecting Diabetic Retinopathy in India. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(9):987-993. [CrossRef]

- DeepEyeVision Inc. web site. https://deepeyevision.com (Last accessed Jan 1, 2024).

- Betzler BK, Chen H, Cheng CY, Lee CS, Ning G, Song SJ, Lee AY, Kawasaki R, van Wijngaarden P, Grzybowski A, He M, Li D, Ran Ran A, Ting DSW, Teo K, Ruamviboonsuk P, Sivaprasad S, Chaudhary V, Tadayoni R, Wang X, Cheung CY, Zheng Y, Wang YX, Tham YC, Wong TY. Large language models and their impact in ophthalmology. Lancet Digit Health. 2023;5(12):e917-e924. [CrossRef]

- Beede E, Baylor E, Hersch F, Iurchenko A, Wilcox L, Ruamviboonsuk P, Vardoulakis LM. A Human-Centered Evaluation of a Deep Learning System Deployed in Clinics for the Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2020; 1–12. [CrossRef]

- John Maeda: How art, technology and design inform creative leaders. TED talk (https://youtu.be/WAuDCOl9qrk?si=oVZzlmAFK5mHssHJ) (Last accessed Jan 1, 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).