Submitted:

08 January 2024

Posted:

10 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

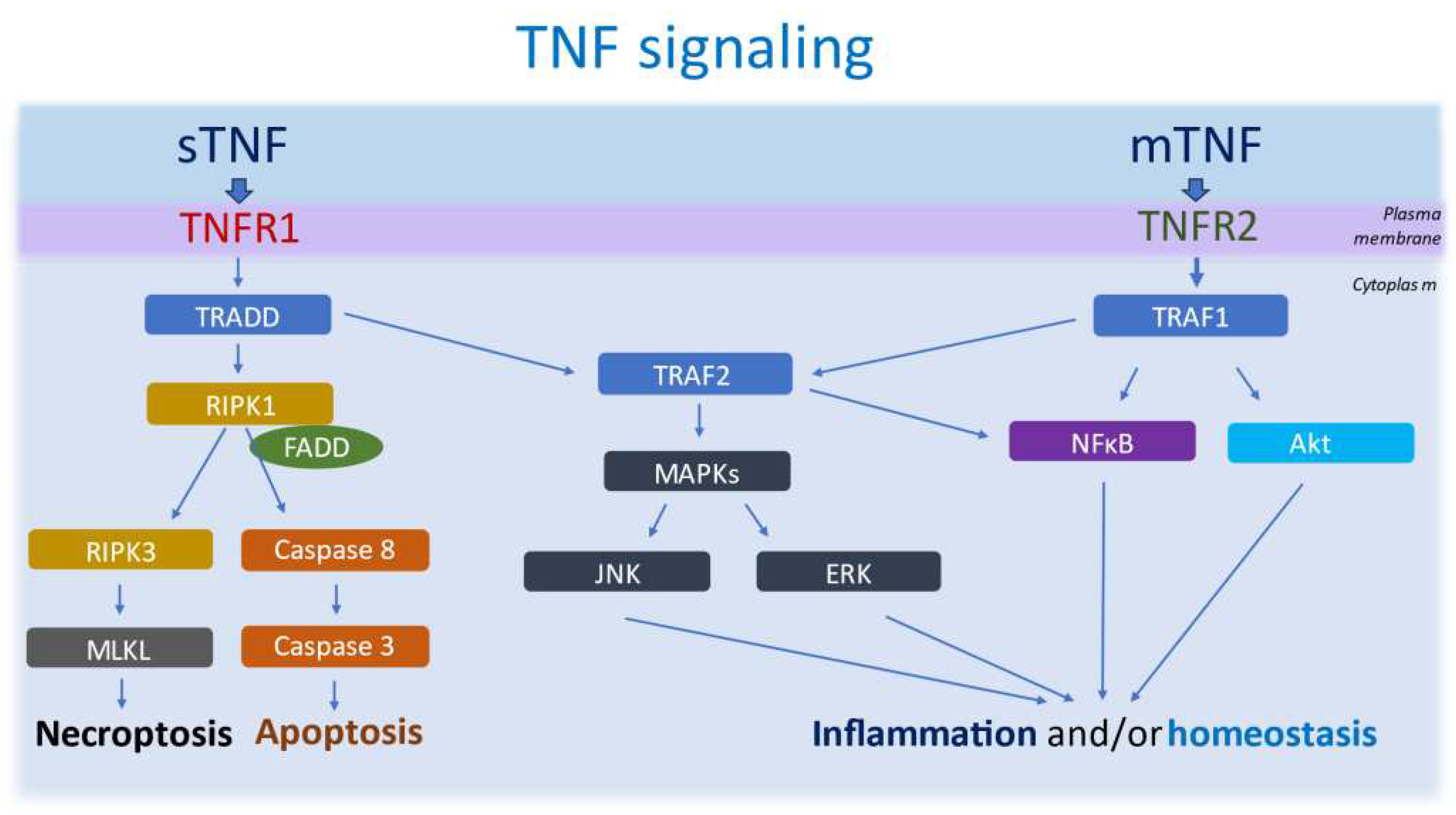

2. TNF biology, cellular production and signalling pathways

3. Potential pathological implications of TNF/TNFRs impairment in MS and EAE

3.1. Neuroinflammation

3.2. Neurodegeneration, Demyelination and Remyelination

4. TNF and meningeal inflammation.

5. TNF and MS lesions

6. TNF and PIRA

7. Anti-TNF therapy and their potential use for PIRA

8. Discussion and conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Browne P, Chandraratna D, Angood C, Tremlett H, Baker C, Taylor BV, Thompson AJ. Atlas of Multiple Sclerosis 2013: A growing global problem with widespread inequity. Neurology. 2014 Sep 9;83(11):1022-4. [CrossRef]

- Koch-Henriksen N, Sørensen PS. The changing demographic pattern of multiple sclerosis epidemiology. Lancet Neurol. 2010 May;9(5):520-32. [CrossRef]

- Filippi M, Bar-Or A, Piehl F, Preziosa P, Solari A, Vukusic S, Rocca MA. Multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018 Nov 8;4(1):43. Erratum in: Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018 Nov 22;4(1):49. [CrossRef]

- Wan ECK. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms in the Pathogenesis of Multiple Sclerosis. Cells. 2020 Oct 1;9(10):2223. [CrossRef]

- Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008 Oct 25;372(9648):1502-17. [CrossRef]

- Vollmer TL, Nair KV, Williams IM, Alvarez E. Multiple Sclerosis Phenotypes as a Continuum: The Role of Neurologic Reserve. Neurol Clin Pract. 2021 Aug;11(4):342-351. [CrossRef]

- Scalfari, A. MS can be considered a primary progressive disease in all cases, but some patients have superimposed relapses - Yes. Mult Scler. 2021 Jun;27(7):1002-1004. [CrossRef]

- Kappos L, Wolinsky JS, Giovannoni G, Arnold DL, Wang Q, Bernasconi C, Model F, Koendgen H, Manfrini M, Belachew S, Hauser SL. Contribution of Relapse-Independent Progression vs Relapse-Associated Worsening to Overall Confirmed Disability Accumulation in Typical Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis in a Pooled Analysis of 2 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Sep 1;77(9):1132-1140. [CrossRef]

- Cree BAC, Hollenbach JA, Bove R, Kirkish G, Sacco S, Caverzasi E, Bischof A, Gundel T, Zhu AH, Papinutto N, Stern WA, Bevan C, Romeo A, Goodin DS, Gelfand JM, Graves J, Green AJ, Wilson MR, Zamvil SS, Zhao C, Gomez R, Ragan NR, Rush GQ, Barba P, Santaniello A, Baranzini SE, Oksenberg JR, Henry RG, Hauser SL. Silent progression in disease activity-free relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2019 May;85(5):653-666. [CrossRef]

- Cree BA, Gourraud PA, Oksenberg JR, Bevan C, Crabtree-Hartman E, Gelfand JM, Goodin DS, Graves J, Green AJ, Mowry E, Okuda DT, Pelletier D, von Büdingen HC, Zamvil SS, Agrawal A, Caillier S, Ciocca C, Gomez R, Kanner R, Lincoln R, Lizee A, Qualley P, Santaniello A, Suleiman L, Bucci M, Panara V, Papinutto N, Stern WA, Zhu AH, Cutter GR, Baranzini S, Henry RG, Hauser SL. Long-term evolution of multiple sclerosis disability in the treatment era. Ann Neurol. 2016 Oct;80(4):499-510. [CrossRef]

- Tur C, Carbonell-Mirabent P, Cobo-Calvo Á, Otero-Romero S, Arrambide G, Midaglia L, Castilló J, Vidal-Jordana Á, Rodríguez-Acevedo B, Zabalza A, Galán I, Nos C, Salerno A, Auger C, Pareto D, Comabella M, Río J, Sastre-Garriga J, Rovira À, Tintoré M, Montalban X. Association of Early Progression Independent of Relapse Activity With Long-term Disability After a First Demyelinating Event in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2023 Feb 1;80(2):151-160. [CrossRef]

- Cagol A, Schaedelin S, Barakovic M, Benkert P, Todea RA, Rahmanzadeh R, Galbusera R, Lu PJ, Weigel M, Melie-Garcia L, Ruberte E, Siebenborn N, Battaglini M, Radue EW, Yaldizli Ö, Oechtering J, Sinnecker T, Lorscheider J, Fischer-Barnicol B, Müller S, Achtnichts L, Vehoff J, Disanto G, Findling O, Chan A, Salmen A, Pot C, Bridel C, Zecca C, Derfuss T, Lieb JM, Remonda L, Wagner F, Vargas MI, Du Pasquier R, Lalive PH, Pravatà E, Weber J, Cattin PC, Gobbi C, Leppert D, Kappos L, Kuhle J, Granziera C. Association of Brain Atrophy With Disease Progression Independent of Relapse Activity in Patients With Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2022 Jul 1;79(7):682-692. [CrossRef]

- Filippi M, Preziosa P, Copetti M, Riccitelli G, Horsfield MA, Martinelli V, Comi G, Rocca MA. Gray matter damage predicts the accumulation of disability 13 years later in MS. Neurology. 2013 Nov 12;81(20):1759-67. [CrossRef]

- Scalfari A, Romualdi C, Nicholas RS, Mattoscio M, Magliozzi R, Morra A, Monaco S, Muraro PA, Calabrese M. The cortical damage, early relapses, and onset of the progressive phase in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2018 Jun 12;90(24):e2107-e2118. [CrossRef]

- Haider L, Prados F, Chung K, Goodkin O, Kanber B, Sudre C, Yiannakas M, Samson RS, Mangesius S, Thompson AJ, Gandini Wheeler-Kingshott CAM, Ciccarelli O, Chard DT, Barkhof F. Cortical involvement determines impairment 30 years after a clinically isolated syndrome. Brain. 2021 Jun 22;144(5):1384-1395. [CrossRef]

- Howell OW, Reeves CA, Nicholas R, Carassiti D, Radotra B, Gentleman SM, Serafini B, Aloisi F, Roncaroli F, Magliozzi R, Reynolds R. Meningeal inflammation is widespread and linked to cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2011 Sep;134(Pt 9):2755-71. [CrossRef]

- James RE, Schalks R, Browne E, Eleftheriadou I, Munoz CP, Mazarakis ND, Reynolds R. Persistent elevation of intrathecal pro-inflammatory cytokines leads to multiple sclerosis-like cortical demyelination and neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020 May 12;8(1):66. [CrossRef]

- Magliozzi R, Howell O, Vora A, Serafini B, Nicholas R, Puopolo M, et al. Meningeal B-cell follicles in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis associate with early onset of disease and severe cortical pathology. Brain. 2007;130:1089–1104. [CrossRef]

- Magliozzi R, Howell OW, Reeves C, Roncaroli F, Nicholas R, Serafini B, et al. A Gradient of neuronal loss and meningeal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:477–493. [CrossRef]

- Absinta M, Sati P, Masuzzo F, Nair G, Sethi V, Kolb H, Ohayon J, Wu T, Cortese ICM, Reich DS. Association of Chronic Active Multiple Sclerosis Lesions With Disability In Vivo. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Dec 1;76(12):1474-1483. Erratum in: JAMA Neurol. 2019 Dec 1;76(12):1520. [CrossRef]

- Absinta M, Lassmann H, Trapp BD. Mechanisms underlying progression in multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2020 Jun;33(3):277-285. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed SM, Fransen NL, Touil H, Michailidou I, Huitinga I, Gommerman JL, Bar-Or A, Ramaglia V. Accumulation of meningeal lymphocytes correlates with white matter lesion activity in progressive multiple sclerosis. JCI Insight. 2022 Mar 8;7(5):e151683. [CrossRef]

- Magliozzi R, Howell OW, Nicholas R, Cruciani C, Castellaro M, Romualdi C, Rossi S, Pitteri M, Benedetti MD, Gajofatto A, Pizzini FB, Montemezzi S, Rasia S, Capra R, Bertoldo A, Facchiano F, Monaco S, Reynolds R, Calabrese M. Inflammatory intrathecal profiles and cortical damage in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2018 Apr;83(4):739-755. [CrossRef]

- Kosa P, Barbour C, Varosanec M, Wichman A, Sandford M, Greenwood M, Bielekova B. Molecular models of multiple sclerosis severity identify heterogeneity of pathogenic mechanisms. Nat Commun. 2022 Dec 12;13(1):7670. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese M, Magliozzi R, Ciccarelli O, Geurts JJ, Reynolds R, Martin R. Exploring the origins of grey matter damage in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015 Mar;16(3):147-58. [CrossRef]

- Sharief MK, Hentges R. Association between tumor necrosis factor-alpha and disease progression in patients with multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1991 Aug 15;325(7):467-72. [CrossRef]

- Selmaj K, Raine CS, Cannella B, Brosnan CF. Identification of lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor in multiple sclerosis lesions. J Clin Invest. 1991 Mar;87(3):949-54. [CrossRef]

- Fischer MT, Wimmer I, Höftberger R, Gerlach S, Haider L, Zrzavy T, Hametner S, Mahad D, Binder CJ, Krumbholz M, Bauer J, Bradl M, Lassmann H. Disease-specific molecular events in cortical multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain. 2013 Jun;136(Pt 6):1799-815. [CrossRef]

- Zahid M, Busmail A, Penumetcha SS, Ahluwalia S, Irfan R, Khan SA, Rohit Reddy S, Vasquez Lopez ME, Mohammed L. Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Blockade and Multiple Sclerosis: Exploring New Avenues. Cureus. 2021 Oct 17;13(10):e18847. [CrossRef]

- Navikas, V. & Link, H. Cytokines and the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis [Review]. J. Neurosci. Res. 45, 322–333 (1996).

- Olmos G, Lladó J. Tumor necrosis factor alpha: a link between neuroinflammation and excitotoxicity. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:861231. [CrossRef]

- Akassoglou K, Bauer J, Kassiotis G, Pasparakis M, Lassmann H, Kollias G, Probert L. Oligodendrocyte apoptosis and primary demyelination induced by local TNF/p55TNF receptor signaling in the central nervous system of transgenic mice: models for multiple sclerosis with primary oligodendrogliopathy. Am J Pathol. 1998 Sep;153(3):801-13. [CrossRef]

- Ofengeim D, Ito Y, Najafov A, Zhang Y, Shan B, DeWitt JP, Ye J, Zhang X, Chang A, Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg H, Geng J, Py B, Zhou W, Amin P, Berlink Lima J, Qi C, Yu Q, Trapp B, Yuan J. Activation of necroptosis in multiple sclerosis. Cell Rep. 2015 Mar 24;10(11):1836-49. [CrossRef]

- Picon C, Jayaraman A, James R, Beck C, Gallego P, Witte ME, van Horssen J, Mazarakis ND, Reynolds R. Neuron-specific activation of necroptosis signaling in multiple sclerosis cortical grey matter. Acta Neuropathol. 2021 Apr;141(4):585-604. [CrossRef]

- Magliozzi R, Howell OW, Durrenberger P, Aricò E, James R, Cruciani C, Reeves C, Roncaroli F, Nicholas R, Reynolds R. Meningeal inflammation changes the balance of TNF signalling in cortical grey matter in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2019 Dec 7;16(1):259. [CrossRef]

- De Jager PL, Jia X, Wang J, de Bakker PI, Ottoboni L, Aggarwal NT, Piccio L, Raychaudhuri S, Tran D, Aubin C, Briskin R, Romano S; International MS Genetics Consortium; Baranzini SE, McCauley JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Haines JL, Gibson RA, Naeglin Y, Uitdehaag B, Matthews PM, Kappos L, Polman C, McArdle WL, Strachan DP, Evans D, Cross AH, Daly MJ, Compston A, Sawcer SJ, Weiner HL, Hauser SL, Hafler DA, Oksenberg JR. Meta-analysis of genome scans and replication identify CD6, IRF8 and TNFRSF1A as new multiple sclerosis susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2009 Jul;41(7):776-82. [CrossRef]

- Holbrook J, Lara-Reyna S, Jarosz-Griffiths H, McDermott M. Tumour necrosis factor signalling in health and disease. F1000Res. 2019 Jan 28;8:F1000 Faculty Rev-111. [CrossRef]

- Caminero A, Comabella M, Montalban X. Role of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and TNFRSF1A R92Q mutation in the pathogenesis of TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome and multiple sclerosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2011, 166, 338–345.

- McCoy MK, Tansey MG. TNF signaling inhibition in the CNS: implications for normal brain function and neurodegenerative disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2008 Oct 17;5:45. [CrossRef]

- Beutler B, Cerami A. The biology of cachectin/TNF--a primary mediator of the host response. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:625-55. [CrossRef]

- Popa C, Netea MG, van Riel PL, van der Meer JW, Stalenhoef AF. The role of TNF-alpha in chronic inflammatory conditions, intermediary metabolism, and cardiovascular risk. J Lipid Res. 2007 Apr;48(4):751-62. [CrossRef]

- Maguire AD, Bethea JR, Kerr BJ. TNFα in MS and Its Animal Models: Implications for Chronic Pain in the Disease. Front Neurol. 2021 Dec 6;12:780876. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Liu T, Lei T, Zhang D, Du S, Girani L, et al.. RIP1/RIP3-regulated necroptosis as a target for multifaceted disease therapy (Review). Int J Mol Med. 201. 44:771–86. 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4244.

- Van Antwerp DJ, Martin SJ, Kafri T, Green DR, Verma IM. Suppression of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis by NF-kappaB. Science. 1996 Nov 1;274(5288):787-9. [CrossRef]

- Fresegna D, Bullitta S, Musella A, Rizzo FR, De Vito F, Guadalupi L, Caioli S, Balletta S, Sanna K, Dolcetti E, Vanni V, Bruno A, Buttari F, Stampanoni Bassi M, Mandolesi G, Centonze D, Gentile A. Re-Examining the Role of TNF in MS Pathogenesis and Therapy. Cells. 2020 Oct 14;9(10):2290. [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia LA, Rothe M, Hu YF, Goeddel DV. Tumor necrosis factor's cytotoxic activity is signaled by the p55 TNF receptor. Cell. 1993 Apr 23;73(2):213-6. [CrossRef]

- Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Regulation of NF-κB by TNF family cytokines. Semin Immunol. 2014 Jun;26(3):253-66. [CrossRef]

- Sabio G, Davis RJ. TNF and MAP kinase signalling pathways. Semin Immunol. 2014 Jun;26(3):237-45. [CrossRef]

- Brenner, D., Blaser, H. & Mak, T. Regulation of tumour necrosis factor signalling: live or let die. Nat Rev Immunol 15, 362–374 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Barton A, John S, Ollier WE, Silman A, Worthington J. Association between rheumatoid arthritis and polymorphism of tumor necrosis factor receptor II, but not tumor necrosis factor receptor I, in Caucasians. Arthritis Rheum. 2001 Jan;44(1):61-5. [CrossRef]

- Komata T, Tsuchiya N, Matsushita M, Hagiwara K, Tokunaga K. Association of tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2) polymorphism with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus. Tissue Antigens. 1999 Jun;53(6):527-33. [CrossRef]

- Sashio H, Tamura K, Ito R, Yamamoto Y, Bamba H, Kosaka T, Fukui S, Sawada K, Fukuda Y, Tamura K, Satomi M, Shimoyama T, Furuyama J. Polymorphisms of the TNF gene and the TNF receptor superfamily member 1B gene are associated with susceptibility to ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, respectively. Immunogenetics. 2002 Mar;53(12):1020-7. [CrossRef]

- Scheurich P, Thoma B, Ucer U, Pfizenmaier K. Immunoregulatory activity of recombinant human tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha: induction of TNF receptors on human T cells and TNF-alpha-mediated enhancement of T cell responses. J Immunol. 1987 Mar 15;138(6):1786-90.

- Kassiotis G, Pasparakis M, Kollias G, Probert L. TNF accelerates the onset but does not alter the incidence and severity of myelin basic protein-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol. 1999 Mar;29(3):774-80. [CrossRef]

- Russi AE, Walker-Caulfield ME, Guo Y, Lucchinetti CF, Brown MA. Meningeal mast cell-T cell crosstalk regulates T cell encephalitogenicity. J Autoimmun. 2016 Sep;73:100-10. [CrossRef]

- Begolka WS, Vanderlugt CL, Rahbe SM, Miller SD. Differential expression of inflammatory cytokines parallels progression of central nervous system pathology in two clinically distinct models of multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 1998 Oct 15;161(8):4437-46.

- Vladić A, Horvat G, Vukadin S, Sucić Z, Simaga S. Cerebrospinal fluid and serum protein levels of tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) interleukin-6 (IL-6) and soluble interleukin-6 receptor (sIL-6R gp80) in multiple sclerosis patients. Cytokine. 2002 Oct 21;20(2):86-9. [CrossRef]

- Maimone D, Gregory S, Arnason BG, Reder AT. Cytokine levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and serum of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 1991 Apr;32(1):67-74. [CrossRef]

- Williams SK, Maier O, Fischer R, Fairless R, Hochmeister S, Stojic A, Pick L, Haar D, Musiol S, Storch MK, Pfizenmaier K, Diem R. Antibody-mediated inhibition of TNFR1 attenuates disease in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2014 Feb 28;9(2):e90117. [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann P, Albrecht M, Ehrenreich H, Weber T, Michel U. Semi-quantitative analysis of cytokine gene expression in blood and cerebrospinal fluid cells by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Res Exp Med (Berl). 1995;195(1):17-29. [CrossRef]

- van Oosten BW, Barkhof F, Scholten PE, von Blomberg BM, Adèr HJ, Polman CH. Increased production of tumor necrosis factor alpha, and not of interferon gamma, preceding disease activity in patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1998 Jun;55(6):793-8. [CrossRef]

- Kemanetzoglou E, Andreadou E. CNS Demyelination with TNF-α Blockers. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017 Apr;17(4):36. PMID: 28337644; PMCID: PMC5364240. [CrossRef]

- Valentin-Torres A, Savarin C, Hinton DR, Phares TW, Bergmann CC, Stohlman SA. Sustained TNF production by central nervous system infiltrating macrophages promotes progressive autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroinflammation. 2016 Feb 22; 13:46. [CrossRef]

- Körner H, Lemckert FA, Chaudhri G, Etteldorf S, Sedgwick JD. Tumor necrosis factor blockade in actively induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis prevents clinical disease despite activated T cell infiltration to the central nervous system. Eur J Immunol. 1997 Aug;27(8):1973-81. [CrossRef]

- Suvannavejh GC, Lee HO, Padilla J, Dal Canto MC, Barrett TA, Miller SD. Divergent roles for p55 and p75 tumor necrosis factor receptors in the pathogenesis of MOG(35-55)-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Cell Immunol. 2000 Oct 10;205(1):24-33. [CrossRef]

- Yang S, Wang J, Brand DD, Zheng SG. Role of TNF-TNF Receptor 2 Signal in Regulatory T Cells and Its Therapeutic Implications. Front Immunol. 2018 Apr 19;9:784. [CrossRef]

- Valencia X, Stephens G, Goldbach-Mansky R, Wilson M, Shevach EM, Lipsky PE. TNF downmodulates the function of human CD4+CD25hi T-regulatory cells. Blood. 2006 Jul 1;108(1):253-61. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Subleski JJ, Kopf H, Howard OM, Männel DN, Oppenheim JJ. Cutting edge: expression of TNFR2 defines a maximally suppressive subset of mouse CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T regulatory cells: applicability to tumor-infiltrating T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2008 May 15;180(10):6467-71. [CrossRef]

- Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003 Feb 14;299(5609):1057-61. [CrossRef]

- Sospedra M, Martin R. Immunology of Multiple Sclerosis. Semin Neurol. 2016 Apr;36(2):115-27. [CrossRef]

- Atretkhany KN, Mufazalov IA, Dunst J, Kuchmiy A, Gogoleva VS, Andruszewski D, Drutskaya MS, Faustman DL, Schwabenland M, Prinz M, Kruglov AA, Waisman A, Nedospasov SA. Intrinsic TNFR2 signaling in T regulatory cells provides protection in CNS autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 Dec 18;115(51):13051-13056. [CrossRef]

- Dopp JM, Mackenzie-Graham A, Otero GC, Merrill JE. Differential expression, cytokine modulation, and specific functions of type-1 and type-2 tumor necrosis factor receptors in rat glia. J Neuroimmunol. 1997 May;75(1-2):104-12. [CrossRef]

- Centonze D, Muzio L, Rossi S, Cavasinni F, De Chiara V, Bergami A, Musella A, D'Amelio M, Cavallucci V, Martorana A, Bergamaschi A, Cencioni MT, Diamantini A, Butti E, Comi G, Bernardi G, Cecconi F, Battistini L, Furlan R, Martino G. Inflammation triggers synaptic alteration and degeneration in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci. 2009 Mar 18;29(11):3442-52. [CrossRef]

- Probert L. TNF and its receptors in the CNS: The essential, the desirable and the deleterious effects. Neuroscience. 2015 Aug 27;302:2-22. [CrossRef]

- Lucchinetti CF, Brück W, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H. Distinct patterns of multiple sclerosis pathology indicates heterogeneity on pathogenesis. Brain Pathol. 1996 Jul;6(3):259-74. [CrossRef]

- hher R, Padutsch T, Bracchi-Ricard V, Murphy KL, Martinez GF, Delguercio N, Elmer N, Sendetski M, Diem R, Eisel ULM, Smeyne RJ, Kontermann RE, Pfizenmaier K, Bethea JR. Exogenous activation of tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 promotes recovery from sensory and motor disease in a model of multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav Immun. 2019 Oct;81:247-259. [CrossRef]

- Arnett HA, Mason J, Marino M, Suzuki K, Matsushima GK, Ting JP. TNF alpha promotes proliferation of oligodendrocyte progenitors and remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2001 Nov;4(11):1116-22. [CrossRef]

- Madsen PM, Motti D, Karmally S, Szymkowski DE, Lambertsen KL, Bethea JR, Brambilla R. Oligodendroglial TNFR2 Mediates Membrane TNF-Dependent Repair in Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by Promoting Oligodendrocyte Differentiation and Remyelination. J Neurosci. 2016 May 4;36(18):5128-43. [CrossRef]

- Magliozzi R, Scalfari A, Pisani AI, Ziccardi S, Marastoni D, Pizzini FB, Bajrami A, Tamanti A, Guandalini M, Bonomi S, Rossi S, Mazziotti V, Castellaro M, Montemezzi S, Rasia S, Capra R, Pitteri M, Romualdi C, Reynolds R, Calabrese M. The CSF Profile Linked to Cortical Damage Predicts Multiple Sclerosis Activity. Ann Neurol. 2020 Sep;88(3):562-573. [CrossRef]

- Javor J, Shawkatová I, Ďurmanová V, Párnická Z, Čierny D, Michalik J, Čopíková-Cudráková D, Smahová B, Gmitterová K, Peterajová Ľ, Bucová M. TNFRSF1A polymorphisms and their role in multiple sclerosis susceptibility and severity in the Slovak population. Int J Immunogenet. 2018 Jul 16. [CrossRef]

- Kalafatakis I, Karagogeos D. Oligodendrocytes and Microglia: Key Players in Myelin Development, Damage and Repair. Biomolecules. 2021 Jul 20;11(7):1058. [CrossRef]

- Dendrou CA, Fugger L, Friese MA. Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015 Sep 15;15(9):545-58. [CrossRef]

- Lassmann H, van Horssen J, Mahad D. Progressive multiple sclerosis: pathology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012 Nov 5;8(11):647-56. [CrossRef]

- Healy LM, Stratton JA, Kuhlmann T, Antel J. The role of glial cells in multiple sclerosis disease progression. Nat Rev Neurol. 2022 Apr;18(4):237-248. [CrossRef]

- Veroni C, Serafini B, Rosicarelli B, Fagnani C, Aloisi F, Agresti C. Connecting Immune Cell Infiltration to the Multitasking Microglia Response and TNF Receptor 2 Induction in the Multiple Sclerosis Brain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020 Jul 7; 14:190. [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann T, Ludwin S, Prat A, Antel J, Brück W, Lassmann H. An updated histological classification system for multiple sclerosis lesions. Acta Neuropathol. 2017 Jan;133(1):13-24. [CrossRef]

- Prineas JW, Kwon EE, Cho ES, Sharer LR, Barnett MH, Oleszak EL, Hoffman B, Morgan BP. Immunopathology of secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001 Nov;50(5):646-57. [CrossRef]

- Calvi A, Clarke MA, Prados F, Chard D, Ciccarelli O, Alberich M, Pareto D, Rodríguez Barranco M, Sastre-Garriga J, Tur C, Rovira A, Barkhof F. Relationship between paramagnetic rim lesions and slowly expanding lesions in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2023 Mar;29(3):352-362. [CrossRef]

- Hofman FM, Hinton DR, Johnson K, Merrill JE. Tumor necrosis factor identified in multiple sclerosis brain. J Exp Med. 1989 Aug 1;170(2):607-12. [CrossRef]

- Elkjaer ML, Frisch T, Reynolds R, Kacprowski T, Burton M, Kruse TA, Thomassen M, Baumbach J, Illes Z. Molecular signature of different lesion types in the brain white matter of patients with progressive multiple sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019 Dec 11;7(1):205. [CrossRef]

- Luchetti S, Fransen NL, van Eden CG, Ramaglia V, Mason M, Huitinga I. Progressive multiple sclerosis patients show substantial lesion activity that correlates with clinical disease severity and sex: a retrospective autopsy cohort analysis. Acta Neuropathol. 2018 Apr;135(4):511-528. [CrossRef]

- Frischer JM, Weigand SD, Guo Y, Kale N, Parisi JE, Pirko I, Mandrekar J, Bramow S, Metz I, Brück W, Lassmann H, Lucchinetti CF. Clinical and pathological insights into the dynamic nature of the white matter multiple sclerosis plaque. Ann Neurol. 2015 Nov;78(5):710-21. [CrossRef]

- Jäckle K, Zeis T, Schaeren-Wiemers N, Junker A, van der Meer F, Kramann N, Stadelmann C, Brück W. Molecular signature of slowly expanding lesions in progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2020 Jul 1;143(7):2073-2088. [CrossRef]

- Wegner C, Esiri MM, Chance SA, Palace J, Matthews PM. Neocortical neuronal, synaptic, and glial loss in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2006 Sep 26;67(6):960-7. [CrossRef]

- Kutzelnigg A, Lassmann H. Cortical lesions and brain atrophy in MS. J Neurol Sci. 2005 Jun 15;233(1-2):55-9. [CrossRef]

- Amato MP, Bartolozzi ML, Zipoli V, Portaccio E, Mortilla M, Guidi L, Siracusa G, Sorbi S, Federico A, De Stefano N. Neocortical volume decrease in relapsing-remitting MS patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2004 Jul 13;63(1):89-93. [CrossRef]

- Klineova S, Lublin FD. Clinical Course of Multiple Sclerosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018 Sep 4;8(9):a028928. [CrossRef]

- Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, Cutter GR, Sørensen PS, Thompson AJ, Wolinsky JS, Balcer LJ, Banwell B, Barkhof F, Bebo B Jr, Calabresi PA, Clanet M, Comi G, Fox RJ, Freedman MS, Goodman AD, Inglese M, Kappos L, Kieseier BC, Lincoln JA, Lubetzki C, Miller AE, Montalban X, O'Connor PW, Petkau J, Pozzilli C, Rudick RA, Sormani MP, Stüve O, Waubant E, Polman CH. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014 Jul 15;83(3):278-86. [CrossRef]

- Frischer JM, Bramow S, Dal-Bianco A, Lucchinetti CF, Rauschka H, Schmidbauer M, Laursen H, Sorensen PS, Lassmann H. The relation between inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis brains. Brain. 2009 May;132(Pt 5):1175-89. [CrossRef]

- Hauser SL, Cree BAC. Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. Am J Med. 2020 Dec;133(12):1380-1390.e2. [CrossRef]

- Doinikow B. Über De- und Regenerationserscheinungen an Achsenzylindern bei der multiplen Sklerose. Z ges Neurol Psych 1915; 27: 151–178.

- Ferguson B, Matyszak MK, Esiri MM, Perry VH. Axonal damage in acute multiple sclerosis. Brain 1997; 120: 393–399.

- Kuhlmann T, Moccia M, Coetzee T, Cohen JA, Correale J, Graves J, Marrie RA, Montalban X, Yong VW, Thompson AJ, Reich DS; International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials in Multiple Sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis progression: time for a new mechanism-driven framework. Lancet Neurol. 2023 Jan;22(1):78-88. [CrossRef]

- Trapp BD, Peterson J, Ransohoff RM, Rudick R, Mörk S, Bö L. Axonal transection in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998 Jan 29;338(5):278-85. [CrossRef]

- Kapica-Topczewska K, Collin F, Tarasiuk J, Czarnowska A, Chorąży M, Mirończuk A, Kochanowicz J, Kułakowska A. Assessment of Disability Progression Independent of Relapse and Brain MRI Activity in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis in Poland. J Clin Med. 2021 Feb 19;10(4):868. [CrossRef]

- Del Negro I, Pez S, Gigli GL, Valente M. Disease Activity and Progression in Multiple Sclerosis: New Evidences and Future Perspectives. J Clin Med. 2022 Nov 9;11(22):6643. [CrossRef]

- Radue EW, Barkhof F, Kappos L, Sprenger T, Häring DA, de Vera A, von Rosenstiel P, Bright JR, Francis G, Cohen JA. Correlation between brain volume loss and clinical and MRI outcomes in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015 Feb 24;84(8):784-93. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Barnett MH, Yiannikas C, Barton J, Parratt J, You Y, Graham SL, Klistorner A. Lesion activity and chronic demyelination are the major determinants of brain atrophy in MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2019 Jul 16;6(5):e593. [CrossRef]

- Ostini C, Bovis F, Disanto G, Ripellino P, Pravatà E, Sacco R, Padlina G, Sormani MP, Gobbi C, Zecca C. Recurrence and Prognostic Value of Asymptomatic Spinal Cord Lesions in Multiple Sclerosis. J Clin Med. 2021 Jan 26;10(3):463. [CrossRef]

- Kapica-Topczewska K, Collin F, Tarasiuk J, Czarnowska A, Chorąży M, Mirończuk A, Kochanowicz J, Kułakowska A. Assessment of Disability Progression Independent of Relapse and Brain MRI Activity in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis in Poland. J Clin Med. 2021 Feb 19;10(4):868. [CrossRef]

- Portaccio E, Bellinvia A, Fonderico M, Pastò L, Razzolini L, Totaro R, Spitaleri D, Lugaresi A, Cocco E, Onofrj M, Di Palma F, Patti F, Maimone D, Valentino P, Confalonieri P, Protti A, Sola P, Lus G, Maniscalco GT, Brescia Morra V, Salemi G, Granella F, Pesci I, Bergamaschi R, Aguglia U, Vianello M, Simone M, Lepore V, Iaffaldano P, Filippi M, Trojano M, Amato MP. Progression is independent of relapse activity in early multiple sclerosis: a real-life cohort study. Brain. 2022 Aug 27;145(8):2796-2805. [CrossRef]

- Tur C, Carbonell-Mirabent P, Cobo-Calvo Á, Otero-Romero S, Arrambide G, Midaglia L, Castilló J, Vidal-Jordana Á, Rodríguez-Acevedo B, Zabalza A, Galán I, Nos C, Salerno A, Auger C, Pareto D, Comabella M, Río J, Sastre-Garriga J, Rovira À, Tintoré M, Montalban X. Association of Early Progression Independent of Relapse Activity With Long-term Disability After a First Demyelinating Event in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2023 Feb 1;80(2):151-160. [CrossRef]

- Müller J, Cagol A, Lorscheider J, Tsagkas C, Benkert P, Yaldizli Ö, Kuhle J, Derfuss T, Sormani MP, Thompson A, Granziera C, Kappos L. Harmonizing Definitions for Progression Independent of Relapse Activity in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. JAMA Neurol. 2023 Nov 1;80(11):1232-1245. [CrossRef]

- Lublin FD, Häring DA, Ganjgahi H, Ocampo A, Hatami F, Čuklina J, Aarden P, Dahlke F, Arnold DL, Wiendl H, Chitnis T, Nichols TE, Kieseier BC, Bermel RA. How patients with multiple sclerosis acquire disability. Brain. 2022 Sep 14;145(9):3147-3161. [CrossRef]

- Bittner S, Oh J, Havrdová EK, Tintoré M, Zipp F. The potential of serum neurofilament as biomarker for multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2021 Nov 29;144(10):2954-2963. [CrossRef]

- Khalil M, Pirpamer L, Hofer E, Voortman MM, Barro C, Leppert D, Benkert P, Ropele S, Enzinger C, Fazekas F, Schmidt R, Kuhle J. Serum neurofilament light levels in normal aging and their association with morphologic brain changes. Nat Commun. 2020 Feb 10;11(1):812. [CrossRef]

- Zou H, Li R, Hu H, Hu Y, Chen X. Modulation of Regulatory T Cell Activity by TNF Receptor Type II-Targeting Pharmacological Agents. Front Immunol. 2018 Mar 26;9:594. [CrossRef]

- Brown JWL, Coles A, Horakova D, Havrdova E, Izquierdo G, Prat A, Girard M, Duquette P, Trojano M, Lugaresi A, Bergamaschi R, Grammond P, Alroughani R, Hupperts R, McCombe P, Van Pesch V, Sola P, Ferraro D, Grand'Maison F, Terzi M, Lechner-Scott J, Flechter S, Slee M, Shaygannejad V, Pucci E, Granella F, Jokubaitis V, Willis M, Rice C, Scolding N, Wilkins A, Pearson OR, Ziemssen T, Hutchinson M, Harding K, Jones J, McGuigan C, Butzkueven H, Kalincik T, Robertson N; MSBase Study Group. Association of Initial Disease-Modifying Therapy With Later Conversion to Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA. 2019 Jan 15;321(2):175-187. [CrossRef]

- Bsteh G, Hegen H, Altmann P, et al. Retinal layer thinning is reflecting disability progression independent of relapse activity in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2020;6(4):2055217320966344. [CrossRef]

- Graf J, Leussink VI, Soncin G, et al. Relapse-independent multiple sclerosis progression under natalizumab. Brain Commun. 2021;3(4):fcab229. [CrossRef]

- van Oosten BW, Barkhof F, Truyen L, Boringa JB, Bertelsmann FW, von Blomberg BM, Woody JN, Hartung HP, Polman CH. Increased MRI activity and immune activation in two multiple sclerosis patients treated with the monoclonal anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody cA2. Neurology. 1996 Dec;47(6):1531-4. [CrossRef]

- Kemanetzoglou E, Andreadou E. CNS Demyelination with TNF-α Blockers. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017 Apr;17(4):36. [CrossRef]

- Bosch X, Saiz A, Ramos-Casals M; BIOGEAS Study Group. Monoclonal antibody therapy-associated neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011 Mar;7(3):165-72. [CrossRef]

| Type Cells Involved | Effects | Effects | Relevance | Relevance in MS | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS patients | TNF in the MS CSF | Macrophages, T cells | Infiltration of activated macrophages/T cells in the brain parenchyma | MS lesions formation | Inflammation | Disability accumulation | [53,54,55] |

| Neurons, Glial cells | Activation of neurons and glial cells | MS lesions formation | Neuroinflammation | [23,26,79,80] | |||

| TNF in MS Lesions | Neurons | Cortical lesionsand Atrophy | GM damage | Neurodegeneration | Disability progression | [35] | |

| Microglia, T cells | Chronic active lesions | WM lesions | Demyelination | [93] | |||

| EAE model | EAE mice | Macrophages, T cells | Infiltration of activated macrophages/T cells inthe brain parenchyma | WM lesions | Neuroinflammation | Diffuse Demyelination | [56] |

| Neurons | AMPAR/NMDAR Overexpression | Neuronal Excitotoxicity | Neurodegeneration | Severe Disease Symptoms | [73] | ||

| EAE TNF KO mice | Macrophages, T cells, Neurons, Glial cells | Infiltration reduction by macrophages and T cells; No AMPAR/NMDAR Overexpression; Enhanced Tregs cells | Neuronal Homeostasis | Neuroprotection | Severe Disease Symptoms | [64] | |

| EAE TNFR1 KO mice | Macrophages, T cells, Neurons, Glial cells | No AMPAR/NMDAR OverexpressionEnhanced Tregs cells | Remyelination Increase and Neurodegeneration Reduction | Neuroprotection | Reduction of disease signs and clinical symptoms | [65] | |

| EAE TNFR2 KO mice | T regs | Suppression of T regs in response to autoreactive T cells | Impaired Remyelination | Demyelination | Aggressive Disease | [70,71] | |

| Oligodendrocytes | Oligodendrocytes Death | Impaired Remyelination | Demyelination | Severe Disease Symptoms; Enhanced T cells infiltration in the CNS; Diffuse Demyelination | [65,78] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).