Introduction

Wellbeing research is now entering the fourth wave of global wellbeing scholarship (Lomas, 2022). However, existential wellbeing (EWB) remains an important and yet largely ignored area of wellbeing research (Cohen et al., 1996; Ownsworth & Nash, 2015; Pelletier et al., 2002).

When you ask someone: “How are you?”, a typical answer is “I’m fine, thank you.” If you ask more specifically “How is your life?”, the answer is most likely something akin to “It’s okay, I just have the usual ups and downs.” Such answers are only automatic responses at the superficial level.

When you want to probe deeper, you may ask “What is the overall quality of your life?” “What would you live for if your were diagnosed with terminal cancer?” or “What would be your regrets at the end of your life?” To assess wellbeing at the deeper level, one would need a complex calculus that requires one to simultaneiously solve several equations. One would need to not only take into account personal history and present circumstances, but also consider future challenges and what will happen after death. More importantly, one needs to wrestle with the existential dimensions of health regarding one’s role in the world, meaning and purpose of life, as well as the meaning of suffering, loneliness, relational difficulties, spiritual yearnings, and the inevitable anxiety about one's fragile existence as a human being.

What is Existential Wellbeing or Existential Health?

The above concerns are characteristics of existential health. According to Hemberg and colleagues (2017), the existential dimension of health has health-promoting potential for older adults who requires nursing and palliative care:

We also assume that the existential dimension of health grows in importance as we age, with implications for healthy aging and related practices. A deepening of the understanding of health and well-being in later life is needed, one that takes into consideration existential aspects and applies a holistic-existential approach.

More recently, The World Health Organization (WHO) revised its definition of health to include spiritual healh, which is an existential necesscity for human beings to find solace and meaning in time of suffering (Winiger, 2022). The WHO’s new Quality of Life Measurement Instrument attempts to measures Spirituality, Religiousness, and Personal Beliefs (WHOQOL-SRPB). More specifically, it measures 8 aspects of such existential universals, which transcend cultures: meaning of life, awe and wonder, wholeness and integration, spiritual strength,inner peace, hope and optimism, spiritual connection, and faith. These factors seem very similar to the existential health dimension described by Hemberg and colleagues (2017).

Critics of this new quality of life measure argue that it is difficult if not impossible to measure intangible varaibles such as spirituality and personal beliefs. To answer these critics, WHO researchers described their WHOQOL approach as a long overdue correction:

Justified or not, it could be argued, these criticisms miss a larger significance of the WHOQOL-SRPB which lies beyond realpolitik and methodological rigour: its unprecedented breadth of consultation, openness, and mutual respect which transcended medical and religious solipsisms and produced a nuanced, verified, and widely shared consensus of what makes life worth living at all. The world, it could be argued, may not need more psychometric instruments, but it surely needs more consultations such as those that produced the WHOQOL-SRPB.

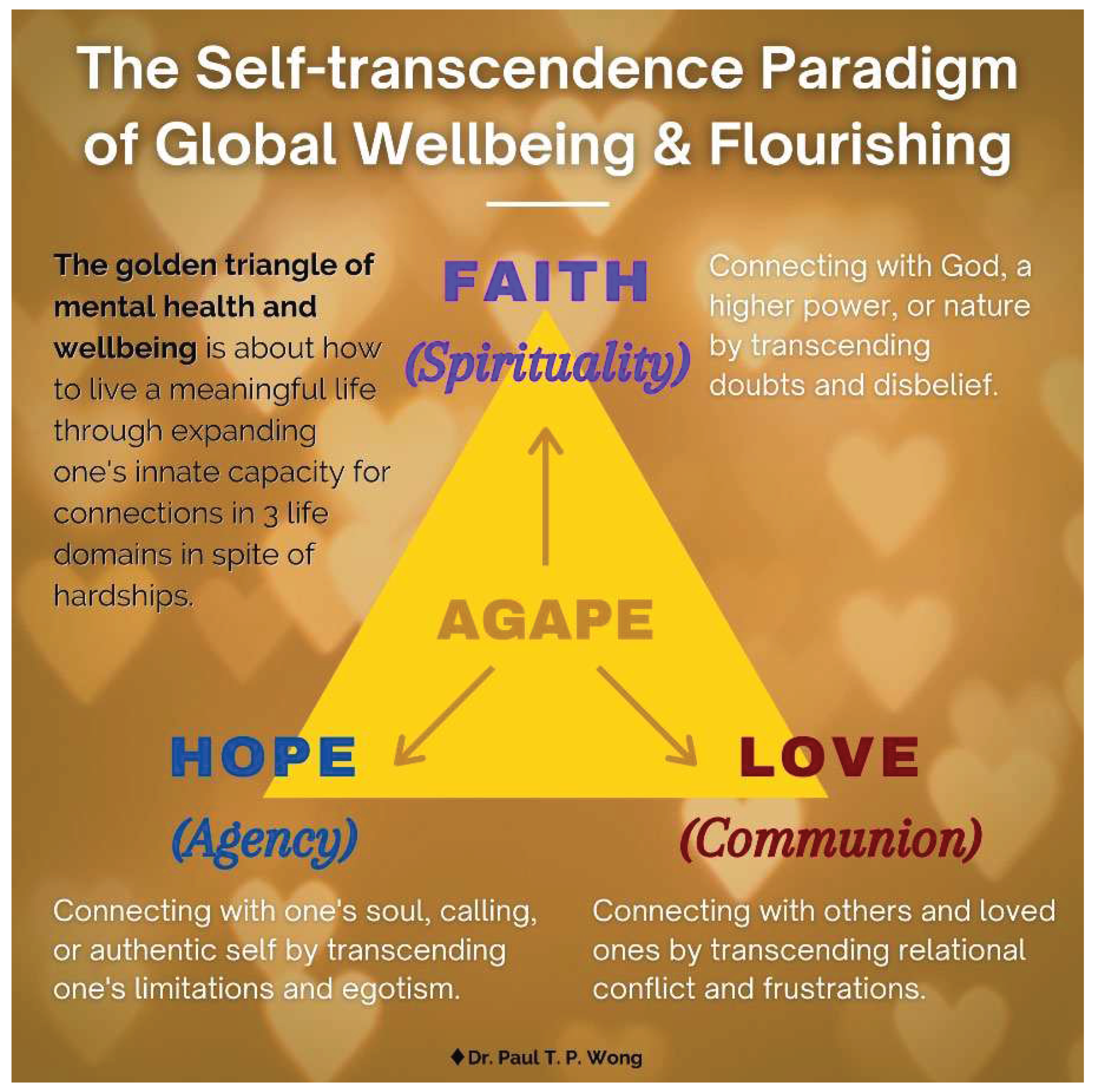

From the perspective of EWB, no matter how harsh the fate and how tough the circumstances, one can still enjoy a certain level of wellbeing through accepting life as it is, pursuing self-transcendence (Wong, Mayer et al., 2021), and activating the spiritual values of faith, hope, and love (Wong, 2023b). To experience EWB, one needs courage and responsibility for one’s physical health, emotional regulation, relations with others, care for the soul, and maintenance of inner peace. In short, EWB is the quality of life of the whole person or holistic wellbeing involving all four dimensions of personhood—bio-psycho-social-and spiritual. As such, EWB overlaps with other types of wellbeing.

EWB and Spiritual Wellbeing

For many other researchers, EWB is more aligned with spiritual/religious wellbeing rather than psychological wellbeing because of its emphasis on spiritual qualities, such as hope, faith and transcendence (Hiebler-Ragger et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2022). In fact, several scales measuring spiritual wellbeing include an EWB subscale (e.g., Paloutzian & Ellison, 1982; Unterrainer et al., 2010). Yet given these parallels, some researchers wonder if EWB has divergent validity with spiritual/religious wellbeing.

On the one hand, Genia’s (2001) factor analysis of Paloutzian et al.’s (1982) Spiritual Wellbeing Scale showed that religious wellbeing and EWB can be distinct constructs. Yet others agree that EWB and spiritual wellbeing could be considered the same construct (Wong et al., 2022). Wong’s sense of spiritual EWB (Wong, 2023b) comes from his faith in God and in the spiritual laws of faith, hope, and love.

These spiritual values of transcending suffering and death may be more adaptive than any other virtues (Christman & Mueller, 2017; Selvam, 2010). Some refer to the Faith-Hope-Love model as ‘spiritual wellness’ (Christman & Mueller, 2017). But it can also be called spiritual-existential wellbeing (SEW) because the theme of spirituality is closely woven with existential concerns (Thompson, 2007). What makes SEW unique is that unlike other kinds of wellbeing, SEW can be positively associated with suffering when it is embraced and transformed. In other words, SEW is positively correlated with flourishing through suffering.

Metaphorically, EWB is born on the sharp cutting edge of a knife, which separates life and death, present moment and eternity, blessings and suffering, joy and sadness, aloneness and connections. Such paradoxical experiences can be achieved with some level of personal maturity, faith in God or the benefelent forces in life, an attitude of gratitude for the gift of life, and the existential wisdom of accepting and understanding that life is both happy and sad at every stage of development. Thus, the positive illusion that one can be happy all the time is a hindrance to EWB.

EWB and Psychological Wellbeing

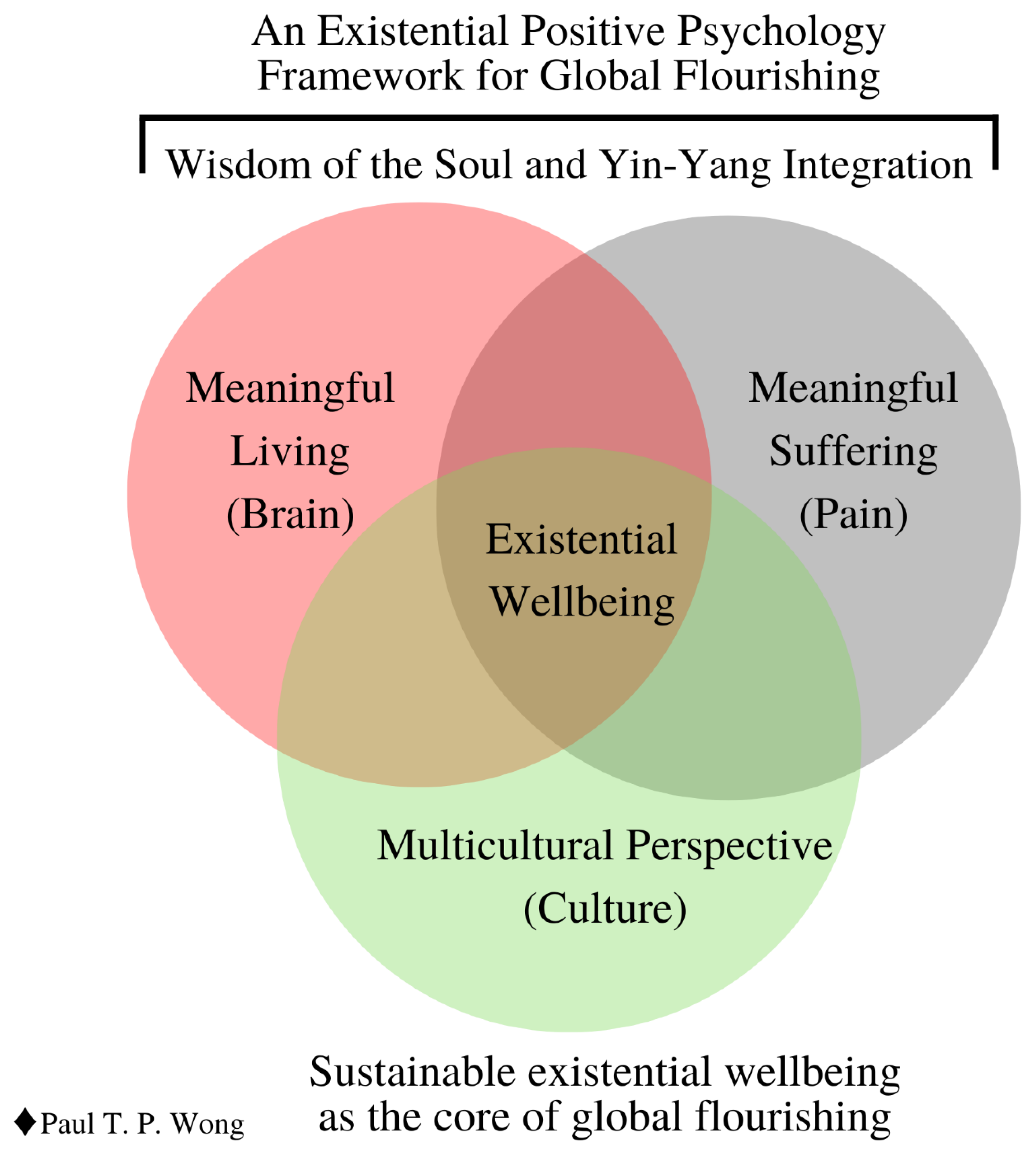

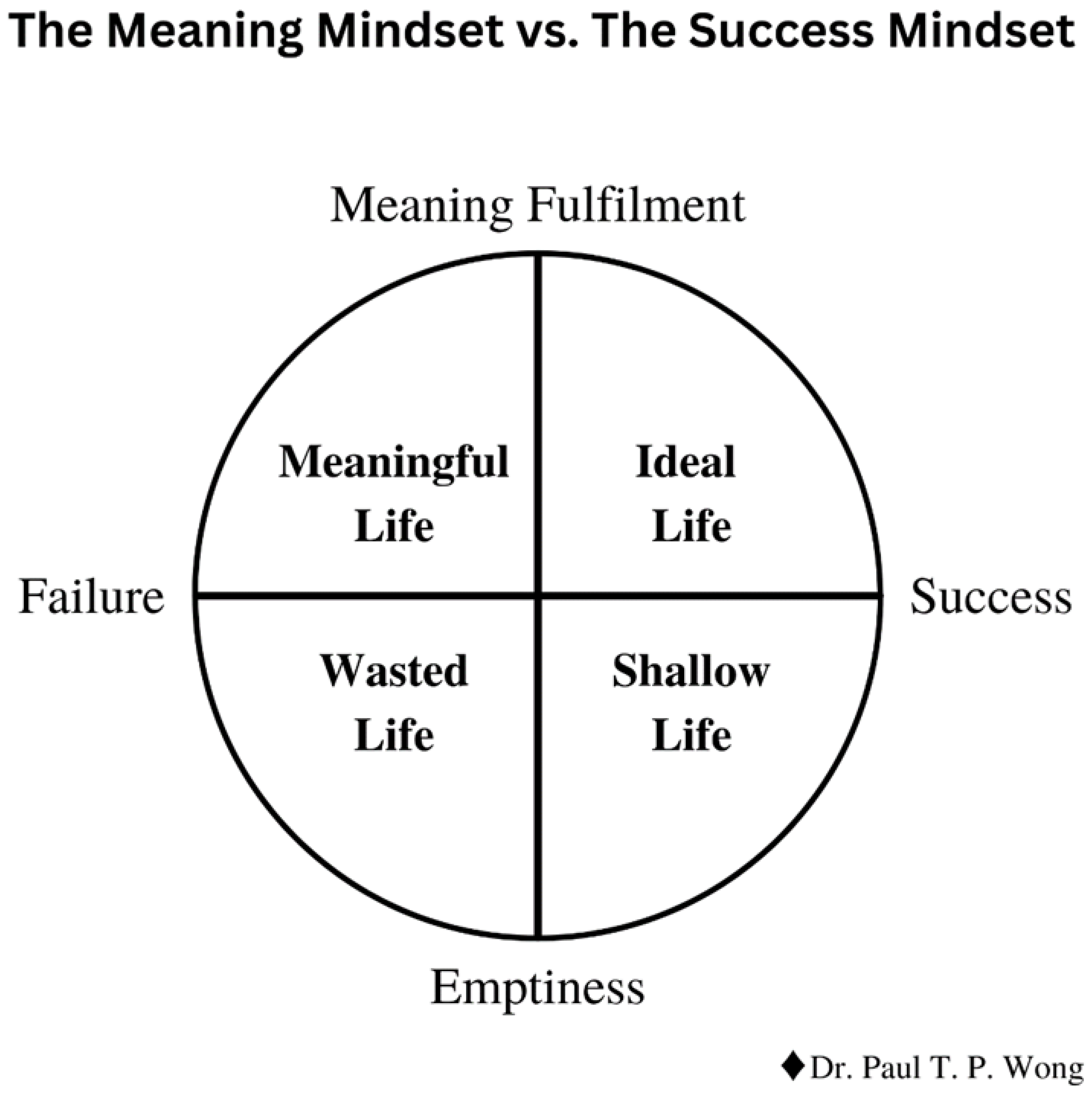

EWB overlaps psychological wellbeing concerning meaning and purpose (Visser et al., 2017). To that end, some researchers have measured EWB in terms of meaning in life (Xi et al., 2017). In her chapter, Ryff (2012) provides scientific evidence suggesting a positive relationship between EWB and biological regulation as well as physical health. However, she equates EWB with psychological wellbeing. As shown in

Figure 1, these two types of wellbeing overlap but they also have their own distinct characteristics. EWB includes much more than meaning and purpose in life; in addition, it is also related to how to tranform suffering to meaning, and how to co-exist with people who are different in terms of language, ideology, skin colour, and culture.

Since human life depends on a healthy body, community support, and responsible government, EWB is, in some way, related to all other types of wellbeing, but it is uniquely involved in izes the phenomenological experience of coping and transforming suffering and existential issues. Thus, it is more a mental state of acceptance and endurance rather than a state of positive affect.

For example, to be able to say “all is well with my soul” (Stringer, 2023), one exhibits the triumph of existantial wellbeing in the mist of trauma. Wong’s (1998a) successful aging research has also identified many seniors in nursing homes or palliative care who were able to find meaning, joy and hope through their faith in God, caring for others, and loving relationships with their family. Wong (the senior author), an 86-year old man, is still able to enjoy a full and productive life in spite of living with constant pains and aches 24/7. In short, there is already enough empirical evidence to concluse that EWB is important for the suffering masses, especially for those who need palliative care.

The History of EWB

Traditionally, EWB is generally defined in terms of a positive state of wellbeing related to meaning and purpose. For example, Hiebler-Ragger and colleagues (2020) discussed the importance of immanent hope, forgiveness, and meaning for EWB, while Ownsworth and Nash (2015), define EWB as “a person’s present state of subjective well-being across existential domains, such as meaning, purpose, and satisfaction in life, and feelings of comfort regarding death and suffering.” (p. 1). However, our recent research on the positive psychology of suffering (Wong, Ho et al., 2023a) has indicated that the adaptive benefit of struggling with suffering and existential crsis cannot be fully captured by subjective wellbeing.

Historically, EWB is rooted in the work of existential philosophers such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Camus, and Sartre, whose existentialism refers to the overarching human concepts of personal freedom, courage, suffering, death, and the pursuit of meaning and purpose. EWB focuses on a person’s overall experience and understanding of self at the deeper level in terms of one’s core values, life purpose, the meaning of suffering and the meaning of relating to people, including those one does not like.

According to Wong and Gingras (2010), EWB is the only kind of wellbeing achievable when we are going through the dark valley of suffering and death:

Inasmuch as we hate suffering and fear death, these existential givens are essential for human flourishing. It takes the terror of death for one to discover the beauty of life; it takes adversity to discover one’s strengths. Watanabe finds peace and happiness in the darkest moments of his life. (p. 4)

In this paper, we explore the adaptive benefits of suffering and provide examples of how one can experience EWB by integrating suffering with wellbeing through self-transcendence, meaning transformation, and the spiritual values (Wong, 2023b).

EWB: A Missing Link in Wellbeing Research

At present, EWB is still a missing component in most measures of wellbeing. In their systematic review of the wellbeing literature, Kauppi and colleagues (2023) concluded that spiritual (or existential) wellbeing could be considered a main theme of wellbeing; however, only 9% of the reviewed articles falls under the domain of spiritual wellbeing. Other wellbeing researchers only refer to Seligman's (2011) PERMA model as the criteria of wellbeing (e.g., Turner et al., 2023). Anderson (2014) noted that suffering and quality of life are intertwined, and it is more morally appropriate and effective to focus on reducing suffering. Clifton (2022) recently suggested that increasing unhappiness or suffering is the blind spot in wellbeing research, and the greatest challenge to achieve global wellbeing is to reduce rising levels of unhappiness and suffering.

Given that EWB is based on the premise that preventing and transforming suffering is the necessay path to living a good life (Wong et al., 2022), it provides one avenue for meeting the health challenges of baby boomers, health inequalities (Bambra et al., 2020), pandemics, and chronic diseases (Hacker et al., 2021). Research in palliative care highlight the importance of existential and spiritual wellbeing.

Existential Wellbeing in Palliative Care

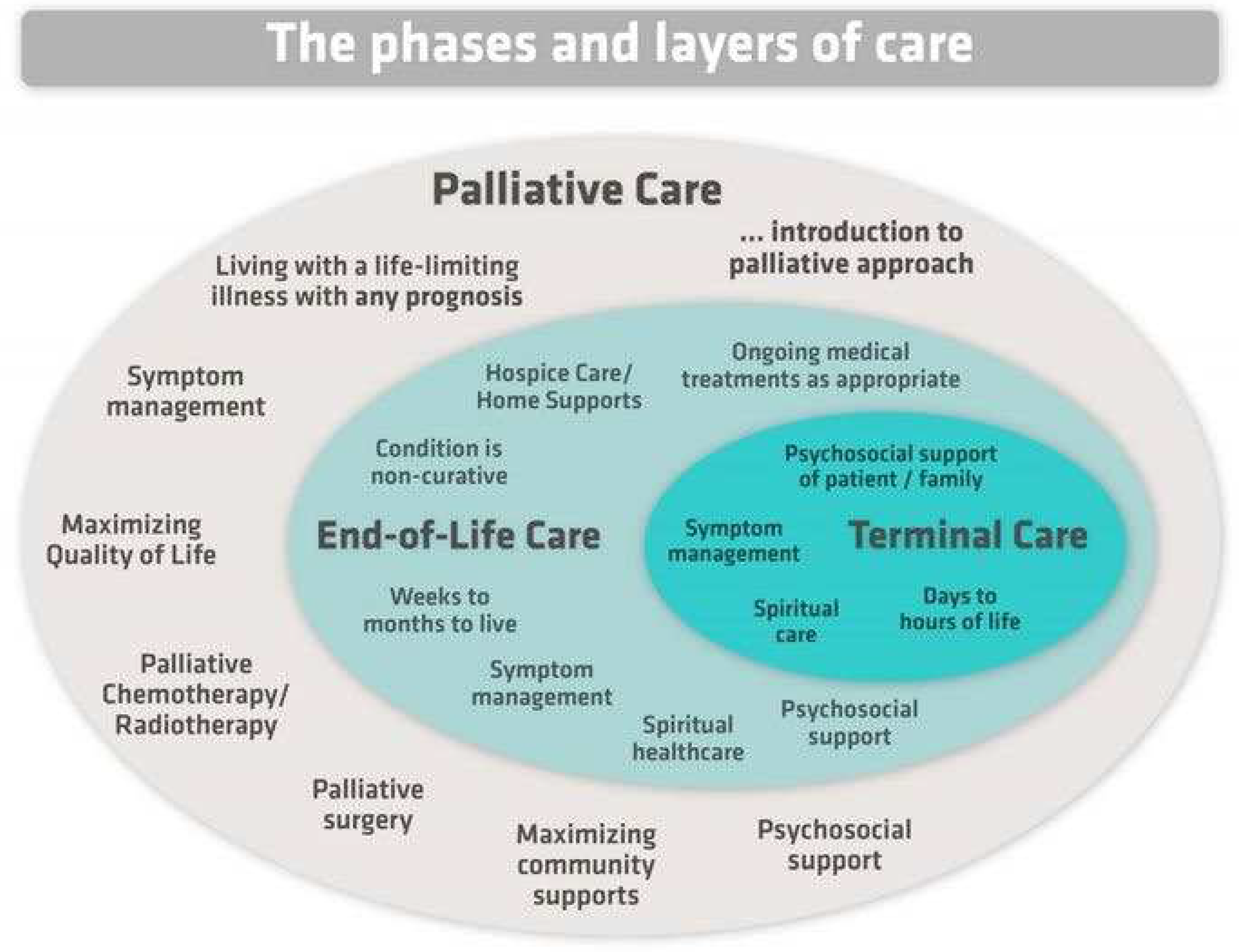

Contrarary to the common perception, people in any age may need palliative care as we witnessed during COVID-19 pandemic. According to Providence Health Care (n.d.):

“Palliate,” the root word, means to cloak, to protect. Palliative care is whole person and family care that is central to all health care. Palliative care is not limited to end-of-life and or terminal-stage care – it’s “available for people living with any illness, at any age and at any stage of an illness” (World Health Organization, 2012).

Better communication about the various stages, palliative care versus end-of-life care versus terminal care, debunking myths around palliative care, and championing the benefits of palliative care will help shift these misconceptions.

The same paper indicates that palliative care, as indicated in

Figure 2, is needed at different stages or layers of care from the largest circule of

Palliative Care of maximizing quality of life and providing psychosocial support to all people lving with a life-limiting illness with any prognosis,

End-of-Life Care for patients with only weeks to months to live, to

Terminal Care for patients with only days or hours to live. For the last two stages, the focus is on symtom manaement and spiritual care for the patients as well as psycholsocial support of patient and family. Thus, palliative care is holistic with its focus on exisential wellbeing.

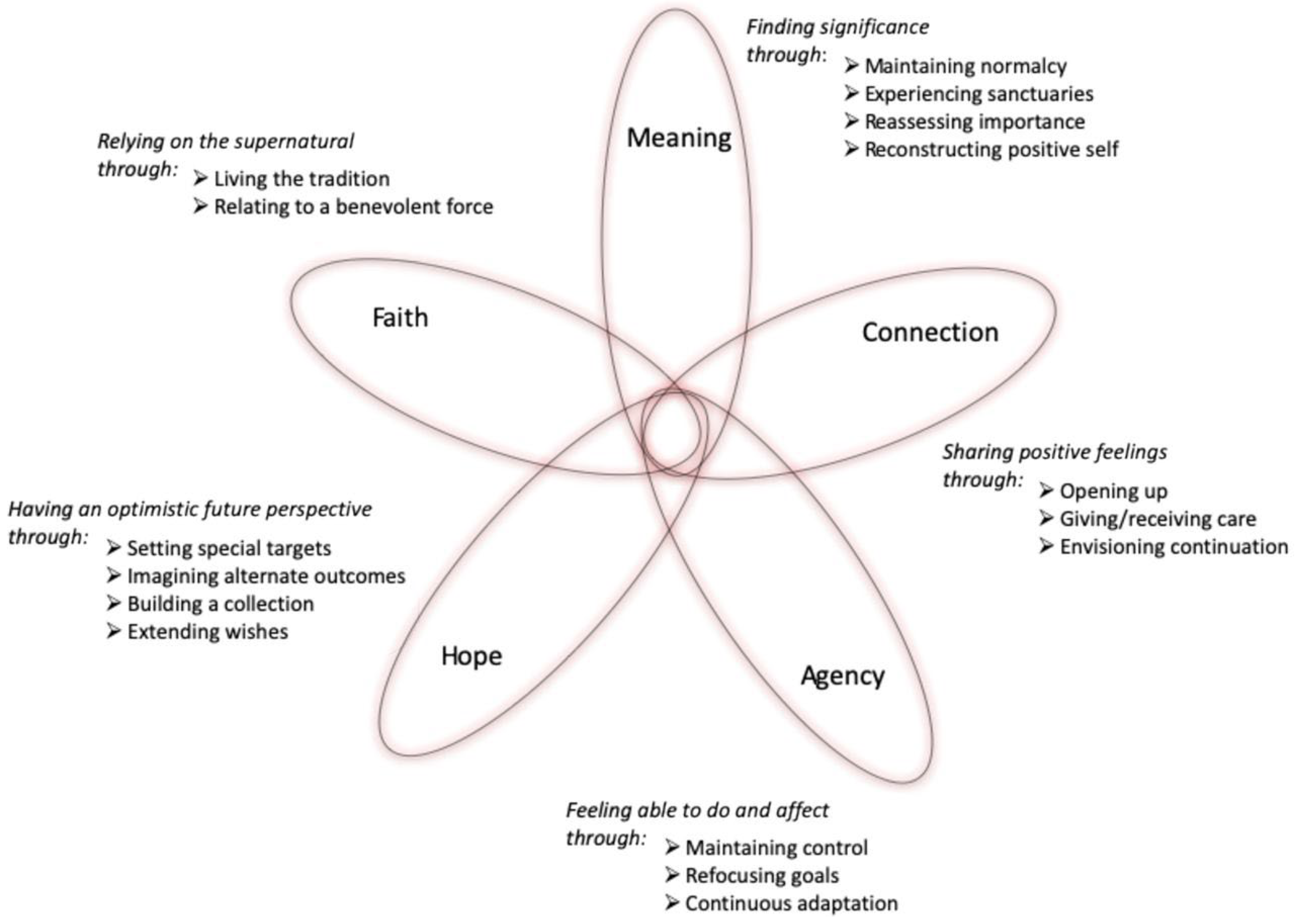

Regarding how to foster existential and spiritual wellbeing in palliative care, Haufe and colleagues (2020) suggest that an effective way to provide relief from symptoms and improve qualtiy of life is to identify and support existential or spiritual strengths of the patient, which can be grouped into 5 clusters as describe in

Figure 3.

Meaning is about finding significance in different aspects of life.

Connection is about sharing feelings with a caring person

Agency is about experiencing the capacity to do something or have some control over one’s life.

Hope pertains to developing an optimistic future perspective.

Faith consists of believing in God or some supernatural and benevolant forces.

Various exercises can be used to foster each of these existential-spiritual strengths. The best part is that these clusters are all interreatled in the person. Thus, strengthening any cluster may benefit other clusers, thus enhanicng patients’ existential wellbeing in palliative care. From the perspective of exisential positive psychology, these five clusters of huamn strength can be both deepened and enriched.

What is the Meaning of Life?

Meaning in life cannot be reduced to the rational process of connecting dots in a particular situation (King & Hicks, 2021). It needs to be connected with something deeper and richer about human existence, what cannot be comprehended through intellectual reasoning alone (May, 1983) or simply focusing on human strengths. The full meaning of life (Wong, 1998b) involves knowing and accepting one’s true self, relating to and serving others, seeking God’s help, and coping with injustice.

According to existential positive psychology, the deep questions about meaning in life necessarily involves the meaning of suffering and the challenges of relating to others.

Figure 4 shows that the true meaning of life depends on the paradoxical co-existence of both high level of suffering and high level of meaning to transform suffering. Unlike other measures of wellbeing, EWB cannot be measured only by a single point on a single dimension; rather, it can only be understood as a point of intersection in a two dimensional space of meaning and success (Wong, 2010). Thus, life can still be meaningful even when one is old and one’s life is not going well, as in the case of Oscar Schindler which we will discuss later.

What is the Meaning of Suffering?

With all the horrors happening, from the Russian war on Ukraine, random mass killings, and deaths from drug overdose, to all kinds of schemes and crimes, not only does our empathy becomes desensitized, but our faith in human progress is shaken. It is easy for people to become depressed and cynical about the future of humanity. We propose that the greatest challenge to achieve sustainable wellbeing and global flourishing is to reduce unnecessary suffering and transform inevitable suffering.

Frankl (1949/1986) considered logotherapy as an adjunct to all modalities of psychotherapy and as a medical ministry to medical practice because how to cope with suffering and death is a timeless and universal existential theme. In other words, how to transcend suffering and death is a transdiagnostic approach to health (Wong, 2021).

Gosetti-Ferencei (2020) shows that the human condition is wrought with difficulty, but despair should be considered alongside the possibility of hope and happiness. Nietzsche, Camus, and Marcel all suggest that pain and joy, as well as despair and hope can be interrelated (also see Wong & Laird, in press.).

According to Anderson (2014), suffering comes from the Latin word suffero which means “long suffering” or “endure pain of hardship with patience.” The virtue to endure is the key to determining the intensity of suffering. All the benefits or values of suffering come from our ability to accept and embrace suffering long enough to bring out the noblest and purest qualities in us, just like the best pearl come from enduring prolonged wounding and healing. Seeking a quick solution thorugh escape or avoidance through addiction or denial will eventually result in more suffering in the long run.

But existential suffering can either results in existential depression/anxiety or personal transformation and EWB. The meaning of suffering comes from heroically overcoming and attributing meaning to suffering, which leads to EWB.

Recently, Forsythe and Mongrain (2023) developed the 8-item Existential Nihilism Scale (ENS). They define existential nihilism as "a sweeping rejection of the existence of MiL and a belief in the futility of trying to establish any meaning or rectify its nonexistence (e.g., attempts to search for MiL)." (p. 2, para. 2). Using the ENS, they explored the relationship between existential nihilism and several wellbeing variables. They found that there was a strong negative relationship between existential nihilism and meaning in life. Additionally, high existential nihilism is associated with higher levels of depression and negative affect, and lower levels of life satisfaction, positive affect, and search for meaning (Forsythe and Mongrain, 2023). Their findings support our hypothesis that a deep sense of meaning and existential wellbeing is important for mental health.

Adrian Moulyn (1982) offers a heroic mode of existence which includes a realistic view about human imperfections and factors of human existence, but also the optimistic view that suffering creates wholeness in human beings. The meaning of suffering lies in its healing power. Suffering helps close the expectation gap between what we desire and what we can have realistically.

According to Buddhist psychology, the desire for attachment is the root of all suffering, which comes from the frustration of unfulfilled desires, fear of losing one's object of desire, anger and grief from abandonment by the object of desire, and feelings of emptiness after actualizing one's desire. The ultimate solution to this dilemma is to be free from desire through the death of the ego.

However, there are limitations to self-cultivation. Not everyone can achieve Nivana and not everyone is confident that they can break free from the karma for the evils during the last life. That is why existential intelligence (or life intelligence; LQ), a constituent of EWB, recognizes the best possible approach to solving human problems is the collaboration between Heaven and oneself. For example, Christianity calls for human responsibility to respond to God’s call to repentance, faith in Jesus for redemption through his sacrificial death, and God’s grace to save us on account of the righteousness of Jesus (see Wong, 2022a).

In sum, the meaning of suffering is based on the following adaptive benefits of suffering: (1) The diagnostic value of telling us that something is wrong in our body or in our life, (2) The healing value of motivating us to change or seek help, (3) The transformative value of helping us become what we are meant to be, and (4) The spiritual value of becoming connected with God or Higher Power.

What is the Meaning of Love and Connections with Others?

From the perspective of existential positive psycholyg, we not only need to consider meaning of suffering, but also need to broader our understation of connections to include loving people we don’t like or even embracing our enemies. Reconciliation with estranged relationships is important for existential wellbeing in old age. We are living in a global village with different cultures and ethnicities. Therefore, how we transcend cultural/racial differences is important for maintaining love and relationships.

Recently, Wong & Mayer (2023) explored the full meaning of love. As a complex concept, love can either be the most powerful motivator for healing and growth or the most destructive force in life; it all depends on the kind of love one has embraced. They also concluded that, at a deeper level, love and suffering are inextricably connected. Suffering is an inevitable aspect of true love, “because it always demands an element of self-sacrifice, because, given temperamental differences and the drama of situations, it will always bring with it renunciation and pain” (Pope Benedict XVI, 2022).

What is Existential Intelligence and Spiritual Wisdom?

For positive psychology as usual, agency or self-efficacy is king. But from the new paradigm of EPP, we need existential intelligence and spiritual wisdom to do the right thing to avoid unnecessary suffering and transform inevitable suffering (Wong, 2022a).

Gardner’s (1999, 1983/2011) existential intelligence, also known as existential thinking (Allan & Shearer, 2012) or life intelligence (LQ) (Wong, 2017a; Wong, 2022b), has been the focus of some research in recent years. LQ is having the necessary life intelligence or existential wisdom to live a meaningful and honourable life (Wong, 2005). LQ includes one’s capacity to understand and think about the big questions regarding one’s existence (Gardner & McConaghy, 2000; Halama & Stríženec, 2004) as well as knowing how to navigate through adverse situations (Wong et al., 2022).

LQ greatly overlaps with the spiritual wisdom of the soul (Wong 2022a; Wong, Ho, et al, 2023a) because both are concerned with meaning in life, transcendental values, and the spiritual/existential dimension (Halama & Stríženec 2004; Vaughan, 2002).

LQ also overlaps with the psychological construct of wisdom (e.g., Grossmann et al., 2020; Oser et al., 1999; Staudinger & Glück, 2011). For example, inspired by the Aristotelean concept of phronesis (or practical wisdom), Staudinger and Kessler’s (2009) integrated model of wisdom and Grossman and colleagues’ (2020) common wisdom model emphasize that wise individuals tend to view issues from a meta-cognitive perspective, therefore gaining deep and broad insights about existence. Additionally, wise individuals tend to understand how to navigate the basic dialectics of human existence and embrace the contradictions in life (Staudinger & Glück, 2011), act in a self-transcendent or altruistic way by being invested in the wellbeing of the global community (Oser et al., 1999), and can regulate their emotions well and tolerate ambiguity (Staudinger & Kessler, 2009). Therefore, to be life intelligent or spiritually intelligent is to have practical or existential wisdom.

Given the above, LQ can be simply defined as “intelligence for life, intelligence for living.” (Wong, 2005), essential for finding meaning in life, meaning in suffering, and living in harmony with one’s neighbors. Most people know how to make a good living, and how to be happy, but seldom taught the life intelligence (LQ) of how to make the best use of one’s fragile and short life to add value to oneself and others.

Many smart and educated people cannot live together in peace and harmony because they use their IQ and EQ to manipulate others for selfish gains, and end up hurting each other and themselves. In contrast, life intelligence (LQ) allows one to (a) understand themselves and connect with both their good and dark sides, (b) have the discernment to differentiate truth from falsehood, true friends from fake friends, and (c) know the wisdom of know how to change what is within one’s control, and how to accept what is beyond human control. Therefore, the aim of life education (or positive education) is to equip students with the necessary existential competency to trancend and transform suffering (Chen et al., 2021; Wong, 2017a). A healthy dosage of LQ will enable them to experience EWB whenever it needed.

Some research has shown that individuals with higher LQ experience higher levels of EWB. Allan and Shearer (2012) created a 11-item scale to measure existential thinking, which they define as “the tendency to explore the fundamental concerns of human existence and the capacity to engage in a meaning-making process that locates oneself in respect to these issues.” (p. 21). They reported that existential thinking was positively correlated with meaning in life, curiosity, and other existential variables, and meaning in life mediated the relationship between existential thinking and existential wellbeing. Kretschmer and Storm (2018) partially replicated these results in a similar study.

McKenzie (1999) created a survey to measure all of Gardner’s (1983/2011) nine types of intelligences including existential intelligence. Some items pertaining to existential intelligence includes “It is important to see my role in the ‘big picture’ of things,” “I enjoy discussing questions about life,” and “It is important for me to feel connected to people, ideas and beliefs.” Although this survey has been validated and utilized in different countries (Hajhashemi & Wong, 2010; Hajhashemi et al., 2018), there has yet to be research that examines if higher LQ scores on McKenzie’s (1999) survey is associated with higher EWB in EWB measures.

Here are some illustrations that highlight the importance of the above 5 clusters of strengths in EWB:

1. Finishing Life Well May be More Important Than Starting Life Well

Would Oscar Schindler’s life (Spielberg, 1993) be characterized as a failure or a success? He failed in many business endeavors. His marriage failed. He failed in moral character as a war profiteer, and as a Nazi member. Yet he succeeded in one tremendously important area: as a noble human being, he spent all his wealth and risked his own life to save as many Jews as he could from Nazi gas chambers.

Why did he do it? This was his answer: "I hated the brutality, the sadism, and the insanity of Nazism. I just did what I had to do, what my conscience told me. That's all there is to it. Really, nothing more." In sum, Schindler showed that the humanistic values of treating all fellow human beings with compassion has the potential to redeem one’s past mistakes. To end life well after many stumbles and pitfalls may be more honorable than to end life miserable when one is born into a wealthy family with many privileges and opportunities.

Unbroken (Jolie, 2014; Wong, 2015) is another example of finding final triumph through all the traumas and tragedies of life. This example supports Viktor Frankl’s (1946/1985) theory that the defiant human spirit is the backbone of resilience and grit. Such defiance is based on (1) one’s unyielding attitude to maintain one’s dignity, (2) stoic courage to accept what cannot be changed, and (3) unwavering faith in transforming suffering into achievement.

These cases support the importance of meaning, hope and faith in God, all of which are important components of EWB.

2. Character, Virtue, and Serving Others are More Important for a Great Life Than Possessions, Power, and Pleasure

How do you conceptualize a great life? Clifton’s (2022) measures of a great life depends much on having a good job, good community, good health, and positive experiences and emotions, all of which are assumptions that tend to characterize the individualistic, secular, and materialistic culture of the West. According to this kind of conventional thinking, is there any hope for vulnerable people born in war-torn countries those who live in proverty in a broken community? According to the metrics of world success, Jesus and Buddha are failures.

Wong (1989) struggled with a very similar problem – is successful aging possible for people with poor health and poverty in old age? The answer boils down to the importance of cultivating inner resources of meaning and spirituality and achieving some EWB (Wong & Yu, 2021). But there is a stronger reason for prioritizing EWB, which is this: When a good life is based on worldly gains, then the end will justify the means, and people will be willing to use and betray each other to get ahead. This is counterproductive because it will undermine trust and relationships, which are the cornerstones for flourishing. All the barriers, suspicions, and conflicts would disappear when people learn to maintain their integrity and relate to each other in an authentic and caring way. Living in an authentic mode allows us to connect with each other at a deeper, soulful level and experience the joy of meaningful relationships.Thus, connections depend not only on sharing of emotions but on authentic relationships.

Towards a New Paradigm of Existential Positive Psychology

EWB is one of the processes and outcomes of Existential Positive Psychology (EPP). In the simplest terms, the paradigm of EPP involves the scientific study of both negative and positive existential universals: how to see the light in the darkness, how to transform suffering into personal growth, and how to experience inner peace and joy through meaningful living, meaningful suffering, and living with others in peace in spite of cultural differences (Ho et al., 2022; Wong et al., 2022; Wong, 2023b).

Figure 5.

represents Wong’s (2023b) latest thinking.

Figure 5.

represents Wong’s (2023b) latest thinking.

This view is growing in popularity because most people understand that it is both necessary and our moral duty to prevent and reduce human suffering. According to Anderson (2014), “human suffering is the greatest humantarian challenge today” (p. 98). To care for the suffering masses requires a paradigm shift from egoisitic concerns to much broader concerns of human suffering, as articulated by Martin Luther King Jr.: “An individual has not started living until he can rise above the narrow confines of his individualistic concerns to the broader concerns of all humanity” (Pittman, 2020). Likewise, Nelson Mandela (2008) said: “The world remains beset by so much human suffering, poverty and deprivation. It is in your hands to make of our world a better one for all, especially the poor, vulnerable and marginalised.” More recently, Rashid and Brooks (2022) argued for a reorientation from worldly self-absorption to universal concerns:

We often follow a misguided formula for happiness—pushing us toward material wealth and other worldly successes. But when our expectations set us down the wrong path, it may be time to reorient ourselves around something new: universal happiness principles we can practice at any age.

The above public sentiments reflect a paradigm shift from positive psychology to EPP, which has begun to attract increasing attention during the COVID-19 pandemic (Wong, Mayer et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2022). Building on the first wave of positive psycholgy that shifted the paradigm of psychology from negative to positive, EPP represents another paradigm shift from a positive focus to a synthesis of both negative (thesis) and positive (antithesis).

The Three Basic Tenets of the New Existential Positive Psychology Paradigm

The new EPP paradigm is characterized by the following three principles:

3. True Positivity is Seeing or Being the Light in the Darkness by Embracing Our Brokenness

Ironically, real positive thoughts emerge not by ignoring negative ones but by transforming them. For instance, happiness has meaning only because we know what it is like when we are sad; a robust positive self-concept does not come from denial or suppression of shame but from focusing on what one has done or is doing to overcome shame (Wong, 2017b).

It is not possible to fully understand any of the positive emotions without considering its opposites. Contrary to the dominant view, true positivity is discovering how to be the light during our darkest hour (Wong, Mayer et al., 2021, Wong et al., 2022). This is the first tenet of the new paradigm of EPP: The best way to avoid both toxic positivity and debilitating negativity is through cultivating true positivity or mature happiness (Wong & Bowers, 2018) and EWB (Wong, 2023b).

2. Sustainable Flourishing Comes from Transcending Opposites Through Dialectics

The present paradigm shift represents a new synthesis of negatives and positives because wellbeing or flourishing can be best understood by considering the dialectical interactions between positive and negative, existential concerns and positive aspirations.

The second tenet of EPP is the necessity of the dialectical process to experience true positivity and sustainable wellbeing by learning how to hold two opposing thoughts, values, and emotions simultaneously, and navigating a dynamic, adaptive balance in each context (Wong, 2022a).

In most life situations, the best way is always the middle way or the way of Zhong Yong. It takes deep reflection and the wisdom of the soul to find the right balance in our responses to situations that we encounter in life (Wong, 2022b; Wong & Bowers, 2018).

3. Re-orientation from Egotism to Self-transcendence is Necessary for Positive Mental Health

How is it possible for us to feel positive about life with all the horrible things going on, such as Russia’s attack of Ukraine, international terrorism, and senseless violence at home? How it is possible to feel good about ourselves when the future looks so bleak and uncertain? You may ask, “How can I be free from the human bondage of carnal desires and egotistic pride?” (Wong, 2022c).

Precisely because of the impossible situations, like Job in the Bible or Sisyphus in Greek mythology, we need the new self-transcendence paradigm thal enables us to transcend all our limitations and reach our highest spiritual ideals of faith, hope, and love (Wong, 2023b). Metaphorically, the deeper our roots, the higher we grow and spread our branches (Wong, 2016; Wong & Laird, in press) as illustrated by

Figure 6.

How to Measure Existential Wellbeing

EWB has been measured in different ways. As mentioned previously, EWB has been widely measured in terms of meaning in life. In a 2017 American national survey, Xi and colleagues developed a brief EWB instrument that asked participants to rate the following two questions on a four-point Likert scale: 1) I believe my life matters to others, and 2) I have a strong sense of purpose that directs my life. These questions are similar to items found in other meaning in life measures, such as George and Park’s (2017) Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scale (e.g., My life matters) and Wong’s (1998b) Personal Meaning Profile (e.g., I have a purpose and direction in life). However, most EWB measures are featured alongside measures of religious or spiritual wellbeing. Paloutzian and colleagues (1982) were among the first to incorporate a EWB subscale in their Spiritual Wellbeing Scale (SWS). The more recent Multidimensional Inventory for Religious/Spiritual Well-being (MI-RSWB) also includes a EWB subscale (Unterrainer et al., 2010). Using these measures, higher EWB is associated with better mental health and wellbeing, higher self-esteem, and lower levels of depression (Genia, 2001; Hiebler-Ragger et al., 2020).

Previous quality of life measures often neglected the existential dimension until Cohen and colleagues’ (1996) developed the McGill Quality of Life (MQoL) Questionnaire. They found that the EWB subscale was as important as the three other subscales (physical symptoms, psychological symptoms, and support) when predicting the quality of life of patients, especially those with local or metastatic disease. The MQOL has been used extensively to measure EWB in cancer and brain tumor patients (Ownsworth & Nash, 2015). In one of the earlier studies, Pelletier and colleagues (2002) administered the MQoL to brain tumor patients and found that half of the sample scored low on the EWB subscale. They concluded that many brain tumor patients struggle with existential issues, and interventions for these patients needed to address the existential dimension.

Several studies have explored the nature of EWB using qualitative methods. Cavers and colleagues (2012) interviewed 26 patients with cerebral glioma and their caregivers over a span of 9-18 months. The interviews were transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis. Their study showed that for these patients, there was no straight trajectory from existential distress to existential wellbeing; rather, patients oscillated between existential wellbeing and existential distress, and hope and despair throughout their illness.

These findings on EWB allign with research on spirituality. For instance, spirituality helps people cope better with serious illness, suffering, and the prospect of impending death, and maintain a sense of inner peace in the face of such adversity (e.g., Puchalski, 2001; Sharecare, n.d.; WebMD Editorial Contributors; Wong & Yu, 2021).

Commenting on gross national happiness, Clifton (2022) indicate the need to account for the spiritual/existential dimension in addition to behavioral economics by citing Robert F. Kennedy’s (1968) speech that emphasized the greater task: “it is to confront the poverty of satisfaction - purpose and dignity - that afflicts us all. Too much and for too long, we seemed to have surrendered personal excellence and community values in the mere accumulation of material things.” Kennedy was right. To increase our wellbeing, we need to fullfill our potential and build our community by treating each other with love and dignity.

Given the controversial history of measuring EWB and our conception of EWB as resulting from successfully addressing three important, intertwined questions about human existence, we offer a preliminary checklist as the framework for developing a EWB Scale. Using this approach, we can ask people to indicate which of the following statements apply to them:

1. I try to have a deeper understanding of myself, especially my shadow or dark side.

2. I want to confront and know both the bright and dark sides of myself.

3. My happiness comes from striving towards my life goal or mission.

4. I see myself as part of a community and the human race as a whole.

5. It is important to accept, forgive, and be kind towards all people, including those who have hurt me.

6. I have helped many people during my life, often at a personal cost.

7. It brings me joy to relieve the suffering of others.

8. I face an uncertain and risky future with courage.

9. Other people are both my hell and my heaven; but I choose to love them anyway.

10. I have learned that I can transform my weaknesses into strengths by doing my best and praying for God’s help.

11. I am painfully aware of my human bondage and my brokenness; that is why I have tried to improve my habits and pray to God to transform me from inside out.

12. I am determined to do the right thing by consulting my conscience and God’s guidance.

13. I choose the narrow path of serving God and others rather than the broad way of worldly success.

14. Maintaining inner peace is more important to me than seeking fun or excitement.

15. I have learned that good and evil, as well as happiness and sadness, always co-exist.

16. I have learned to let go because nothing in this world is permanent.

17. I have learned to treat everything with a sense of detachment.

18. To me, it is more important to please God than to please people.

19. I embrace suffering because it adds some depth to my life and makes me a better person.

20. I have learned to see something good and beautiful in every situation.

21. The suffering of the poor and homeless motivates me to take action to reduce social injustices and discrimination.

22. I am grateful for the gift of life and our beautiful planet earth.

23. I don't see earthly death as the end of life, but as a promotion to my heavenly home.

24. I believe that eventually love will overcome hate, and goodness will prevail over evil.

25.Compared to last year, my life is now much better overall.

26. I have not accomplished all the things that are important to me, but I am satisfied that I did not give up and have run a good race.

27. I have given more to society than I have taken from it.

28. It gives me great joy to be able to alleviate the suffering in others.

Based on our literature review and theoretical analysis in this paper, the above checklist has both face validity and construct validity. Therefore, we predict that a person who endorses most of the above items should be able to enjoy mature happiness (Wong & Bowers, 2018) and EWB, and suffer less depression and anxiety as well as stressful or traumatic situations. However, psychometric work is needed to evaluate and refine this initial set of items.

Conclusion

We are facing an unprecedented mental health crisis which cannot be resolved by the medical model or the health sector alone. To resolve this crisis, we need to involve all sectors in the society – such as the workplace, school, family, and community – and adopt a new cultural narrative of behavioral economics (Wong et al., 2023a). More importantly, we need to pay more attention to EWB as a source of total wellness because of the prevalence of suffering and conflicts.

Recently, Per-Einar Binder (2022) emphasized the existential dimension of health and argues that seeking perfect health without suffering can be a source of existential suffering. Therefore, it is more adaptive to consider suffering as an unavoidable part of life and actively relate to suffering in a way that may contribute to our health. Likewise, Clifton (2022) recognizes the serious consequences of trying to escape from unhappiness or pain. Citing Case and Deaton’s (2020) Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, Clifton agrees that the dramatic increase in opioid overdoses, alcohol poisoning, and suicide in working class white males in the US to alleviate rising pain levels results in deaths of despair. He concludes that “the trend of increasing physical pain does not bode well for the world” (p. 150) and “the indicators of tomorrow must look more holistically at what make a great life – including measures of the quality of our communities, our physical health, and our social wellbeing” (p. 219).

Along similar lines, Anderson (2014) concludes that “a successful future depends, in part, on how successful global society is in recognizing and alleviating human suffering everywhere... Alleviating suffering is a force for healing the world – and ourselves” (p. 98). The EPP paradigm of flourishing through overcoming suffering posits that quality of life, or total wellbeing, depends on achieving EWB (Wong, 2023a, 2023b; Wong, Mayer et al., 2021, Wong, Ho et al., 2022). More work is needed to develop valid and reliable measures of EWB as an important indicator of flourishing.

Perhaps the most important question we can ask people about their EWB is: “If you review and reflect on both the negative and positive aspects of your life, how would you rate your life in terms of how well you have lived a worthwhile and honourable life (on a scale of 1-5)? Can you also provide a brief explanation for your decision?” EWB is important because it encourages people to develop a deep life with roots that stretch far down into the dark soil of suffering so that they are more likely to survive the storms in life and flourish.

In sum, we conclude that EWB is an important part of total wellbeing of overall quality of life. Those who enjoy and exhibit EWB have the following defining characteristic:

They have the existential courage and wisdom to live, relate, and die well in a world full of conflicts and brokenness.

They are able to cope with chronic pain, handicaps, and systemic discrimination by turning every negative into positive, and every tragedy into triumph though meaning and personal transformation.

They are able to see the light and be the light in the darkest hours through the transcendental values of faith, hope, and love.

These qualities will empower people to live the best possible deep life even when life is hard and the future is bleak. These qualities can even enable people to enjoy a high quality of life in palliative care.

Conflicts of Interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Allan, B. A. , & Shearer, C. B. The scale for existential thinking. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 2012, 31, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. E. Human suffering and quality of life: Conceptualizing stories and statistics. Springer. 2014.

- Bambra, C. , Riordan, R., Ford, J., & Matthews, F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. Journal of epidemiology and community health 2020, 74, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, P.-E. Facing the uncertainties of being a person: On the role of existential vulnerability in personal identity. Philosophical Psychology 2022. [CrossRef]

- Case, A. , & Deaton, A. Deaths of despair and the future of capitalism. Princeton University Press. 2020.

- Cavers, D. , Hacking, B., Erridge, S. E., Kendall, M., Morris, P. G., & Murray, S. A. Social, psychological and existential well-being in patients with glioma and their caregivers: a qualitative study. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2012, 184, E373–E382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H. , Chang, S.-M., & Wu, H.-M. Discovering and approaching mature happiness: The implementation of the CASMAC model in a university English class. Frontiers in Education. [CrossRef]

- Christman, S. K. , & Mueller, J. R. Understanding spiritual care: The faith-hope-love model of spiritual wellness. Journal of Christian Nursing 2017, 34, E1–E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, J. Blind spot: The global rise of unhappiness and how leaders missed it. Gallup Press. 2022.

- Cohen, S. R. , Mount, B. M., Tomas, J. J., & Mount, L. F. Existential well-being is an important determinant of quality of life. Evidence from the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire. Cancer 1996, 77, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeck, N. , Carreno, D. F., & Pérez-Escobar, J. A. Meaning-Centered Coping in the Era of COVID-19: Direct and Moderating Effects on Depression, Anxiety, and Stress. Frontiers in psychology 2021, 12, 648383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, J. , & Mongrain, M. The Existential Nihilism Scale (ENS): Theory, development, and psychometric evaluation. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. Washington Square Press. (First published in 1946).

- Frankl, V. E. (1986). The doctor and the soul: From psychotherapy to logotherapy. Second Vintage Books. (Originally published in 1949).

- Gardner, H. (1999). Are there additional intelligences? The case of naturalist, spiritual and existential intelligences. In J. Kane (Ed.), Education, information and transformation (pp. 111-131). Prentice Hall.

- Gardner, H. (2011). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Hachette UK. (Originally published in 1983).

- Gardner, H. (2020, ). A resurgence of interest in existential intelligence: Why now? 8 July. Available online: https://www.howardgardner.com/howards-blog/a-resurgence-of-interest-in-existential-intelligence-why-now.

- Gardner, H. , & McConaghy, T. Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. ATA Magazine 2000, 80, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Genia, V. Evaluation of the Spiritual Well-Being Scale in a sample of college students. International Journal of the Psychology of Religion 2001, 11, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L. S. , & Park, C. L. The Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scale: A tripartite approach to measuring meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2017, 12, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosetti-Ferencei JA () Existential suffering happiness hope In, J.A. Gosetti-Ferencei JA () Existential suffering happiness hope In, J.A. Gosetti-Ferencei, On being and becoming: an existentialist approach to life 2020; (p. 264-277). [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, I. , Weststrate, N.M., Ardelt, M., Brienza, J.P., Dong, M., Ferrari, M., Fournier, M.A., Hu, C.S., Nusbaum, H.C., & Vervaeke, J. (2020). The science of wisdom in a polarized world: Knowns and unknowns. Psychological Inquiry, 31, 103-133. [CrossRef]

- Hacker, K. A. , Briss, P. A., Richardson, L., Wright, J., & Petersen, R. COVID-19 and Chronic Disease: The Impact Now and in the Future. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2021, 18, 210086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajhashemi, K. , & Wong, B. E. A validation study of the Persian version of Mckenzie's (1999) multiple intelligences inventory to measure MI profiles of pre-university students. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities (JSSH) 2010, 18, 343–355. [Google Scholar]

- Hajhashemi, K. , Caltabiano, N., Anderson, N., & Tabibzadeh, S. A. Multiple intelligences, motivations and learning experience regarding video-assisted subjects in a rural university. International Journal of Instruction 2018, 11, 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Halama, P. , & Stríženec, M. Spiritual, existential or both? Theoretical considerations on the nature of "higher" intelligences. Studia Psychologica 2004, 46, 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Haufe, M. , Leget, C., Potma, M., & Teunissen, S. How can existential or spiritual strengths be fostered in palliative care? An interpretative synthesis of recent literature. BMJ supportive & palliative care, bmjspcare-2020-002379, 0023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemberg, J., Forsman, A. K., & Nordmr, J. One day at a time – being in the present experienced as optimal health by older adults – the existential health dimension as a health-promoting potential. Nursing and Palliative Care. 2017. Available online: https://www.oatext.com/pdf/NPC-2-148.pdf.

- Hiebler-Ragger, M. , Kamble, S. V., Aberer, E., & Unterrainer, H. F. The relationship between existential well-being and mood-related psychiatric burden in Indian young adults with attachment deficits: a cross-cultural validation study. BMC psychology 2020, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S. , Cook, K. V., Chen, Z. J., Kurniati, N. M. T., Suwartono, C., Widyarini, N., Wong, P. T. P., & Cowden, R. G. Suffering, psychological distress, and well-being in Indonesia: A prospective cohort study. Stress and Health. [CrossRef]

- Jolie, A. (Director). (2014). Unbroken. Universal Pictures.

- Kauppi, K. , Vanhala, A., Roos, E., & Torkki, P. Assessing the structures and domains of wellness models: A systematic review. International Journal of Wellbeing 2023, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R. F. (1968, March 18). Remarks at the University of Kansas, March 18, 1968. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. 18 March. Available online: https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/the-kennedy-family/robert-f-kennedy/robert-f-kennedy-speeches/remarks-at-the-university-of-kansas-march-18-1968.

- King, L. A. , & Hicks, J. A. The science of meaning in life. Annual review of psychology 2021, 72, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, M., & Storm, L. The relationships of the five existential concerns with depression and existential thinking. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology 2018, 7. Available online: https://www.meaning.ca/ijepp-article/vol7-no1/the-relationships-of-the-five-existential-concerns-with-depression-and-existential-thinking/.

- Lomas, T. Making waves in the great ocean: A historical perspective on the emergence and evolution of wellbeing scholarship. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2022, 17, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandela, N. (2008, June 25). Address by Nelson Mandela at dinner celebrating his 90th birthday, London - United Kingdom [Speech]. Mandela.gov. 25 June. Available online: http://www.mandela.gov.za/mandela_speeches/2008/080625_90.htm.

- May, R. (1983). The discovery of being: Writings in existential psychology. Norton.

- McKenzie, W. (1999). Multiple Intelligences Survey. Surfaquarium. Available online: https://surfaquarium.com/MI/inventory.htm.

- Moulyn, A. (1982). The meaning of suffering: An interpretation of human existence from the viewpoint of time. Praeger.

- Oser, F.K.; Schenker, C. ; Spychiger M (1999) Wisdom: An action-oriented approach In, K.H. Reich, F. K. Oser, & W. G. Scarlett (Eds.), Psychological Studies on Spiritual and Religious Development (pp. 85–109). Pabst.

- Ownsworth, T. , & Nash, K. (2015). Existential well-being and meaning making in the context of primary brain tumor: conceptualization and implications for intervention. Frontiers in oncology, 5. [CrossRef]

- Paloutzian, R.F. ; Ellison CW (1982) Loneliness spiritual well-being the quality of life In, L.A. Peplau, & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 224-236). John Wiley & Sons.

- Pelletier, G. , Verhoef, M. J., Khatri, N., & Hagen, N. Quality of life in brain tumor patients: The relative contributions of depression, fatigue, emotional distress, and existential issues. Journal of neuro-oncology 2002, 57, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittman, R. B. (2020, January 20). Moving forward and looking back: My reflections on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. United Nations Association of the United States of America. https://unausa.org/rachel-pittman-statement-mlk-day/.

- Pope Benedict XVI. (2022). Suffering and love. Catholic Education Resource Center. https://www.catholiceducation.org/en/religion-and-philosophy/spiritual-life/suffering-and-love.html.

- Providence Health Care. (n.d.). What is palliative care? https://hpc.providencehealthcare.org/about/what-palliative-care.

- Puchalski C., M. The role of spirituality in health care. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center) 2001, 14, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, R., & Brooks, A. C. (2022, November 14). A new formula for happiness. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/podcasts/archive/2022/11/happiness-formula-howto-age/672109 /. 14 November.

- Reed, P. G., & Haugan, G. (2021, March 12). Self-transcendence: A salutogenic process for well-being. In G. Haugan, & M. Eriksson (Eds.), Health promotion in health care – wital theories and research (Chapter 9). 12 March. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585654.

- Rittel, H. W. J. , & Webber, M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. ( 4, 155–169.

- Ryff CD (2012) Existential well-being health In PT, P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (pp. 233–247). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

- Selvam, S. G. (2010). Faith, hope and love as expressions of human transcendence: Insights from positive psychology [Paper presentation]. The Postgraduate Interdisciplinary Conference on Faith, Hope and Love, Heythrop College. Available online: https://www.sahayaselvam.org/2010/12/14/faith-hope-and-love-as-expressions-of-human-transcendence-insights-from-positive-psychology-2/.

- Sharecare. (n.d.). How does spiritual well-being affect overall quality of life? https://www.sharecare.com/health/spiritual-wellness-religion/spiritual-affect-quality-of-life.

- Spielberg, S. (Director). (1993). Schinder’s list.

- Staudinger, U. M. , & Glück, J. Psychological wisdom research: Commonalities and differences in a growing field. Annual Review of Psychology 2011, 62, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudinger, U.M. ; Kessler E -M (2009) Adjustment growth—two trajectories of positive personality development across adulthood In, M.C. Smith & N. DeFrates-Densch (Eds.), Handbook of research on adult learning and development (pp. 241–268). Routledge.

- Stringer, D. (2023, April 25). The Story Behind "It is Well with My Soul": A History of the Beloved Hymn. Imperfect Dust. https://imperfectdust.com/blogs/news/the-story-behind-it-is-well-with-my-soul-a-history-of-the-beloved-hymn. 25 April.

- Thompson, N. Spirituality: An existentialist perspective. Illness, Crisis & Loss 2007, 15, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J. , Roberts, R. M., Proeve, M., & Chen, J. Relationship between PERMA and children’s wellbeing, resilience and mental health: A scoping review. International Journal of Wellbeing 2023, 13, 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterrainer H., F. , Huber, H. P., Ladenhauf, K. H., Wallner-Liebmann, S. J., & Liebmann, P. M. MI-RSB 48: the development of a multidimensional inventory of religious-spiritual well-being. Diagnostica 2010, 56, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, F. What is spiritual intelligence? Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2002, 42, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, A. , Garssen, B., & Vingerhoets, A. J. Existential well-Being: Spirituality or well-Being? The Journal of nervous and mental disease 2017, 205, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WebMD Editorial Contributors. (2021, October 25). How spirituality affects mental health. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/balance/how-spirituality-affects-mental-health.

- Winiger, F. Spirituality, Religiousness, and Personal Beliefs in the WHO’s Quality of Life Measurement Instrument (WHOQOL-SRPB). In S. Peng-Keller, F. Winiger, & R. Rauch (Eds.), The Spirit of Global Health: The World Health Organization and the 'Spiritual Dimension' of Health 2022, 1946-2021 (pp. 133-160). [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P. Personal meaning and successful aging. Canadian Psychology 1989, 30, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (1998a). Wong PT P Implicit theories of meaningful life the development of the Personal Meaning Profile In PT, P. Wong, & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 111-140). Erlbaum.

- Wong PT, P. (1998b). Spirituality, meaning, and successful aging. In P. T. P. Wong & P. S. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 359–394). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P. T. P. (2005). A course on the meaning of life (Part 3): What is your life intelligence (LQ)? International Network on Personal Meaning. http://www.meaning.ca/archives/MOL_course/MOL_course3.htm.

- Wong, P. T. P. Meaning therapy: An integrative and positive existential psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 2010, 40, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P. The positive psychology of grit: The defiant power of the human spirit. [Review of the movie Unbroken, 2014]. PsycCRITIQUES 2015, 60. [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P. Self-transcendence: A paradoxical way to become your best. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology 2016, 6. https://www.meaning.ca/ijepp-article/vol6-no1/self-transcendence-a-paradoxical-way-to-become-your-best/.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017a, October 3). Lessons of life intelligence through life education. Invited talk presented at Tzu Chi University, Hualien, Taiwan.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017b). The positive psychology of shame and the theory of PP 2.0 [Review of the book The value of shame: Exploring a health resource in cultural contexts, by E. Vanderheiden & C. H. Mayer] PsycCRITIQUES, 62. [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P. The Frankl cure for the 21st century: Why self-transcendence is the key to mental health and flourishing. The International Forum for Logotherapy 2021, 41, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P. The wisdom of the soul: The missing key to happiness and positive mental health? [Review of the book A Time for Wisdom: Knowledge, Detachment, Tranquility, Transcendence, by P. T. McLaughlin & M. R. McMinn]. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology 2022, 11. Available online: https://www.meaning.ca/ijepp-article/vol11-no2/the-wisdom-of-the-soul-the-missing-key-to-happiness-and-positive-mental-health/.

- Wong, P. T. P. The best possible life in a troubled world: The seven principles of self-transcendence [亂世中活出最好的人生:自我超越的七項原則]. Positive Psychology in Counseling and Education 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P. (2022c, June 24). How can I be free from my struggles and live a happy life? [President’s Column]. Positive Living Newsletter. 24 June. Available online: https://www.meaning.ca/article/how-can-i-be-free-from-my-struggles-and-live-a-happy-life.

- Wong PT P Pioneer in research in existential positive psychology of suffering global flourishing: Paul, T.P. Wong. Applied Research in Quality of Life 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P. Spiritual-existential wellbeing (SEW): The faith-hope-love model of mental health and total wellbeing. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology 2023, 11. http://www.drpaulwong.com/spiritual-existential-wellbeing.

- Wong PT, P.; Arslan, G.; Bowers, V.L.; Peacock, E.J.; Kjell ON, E.; Ivtzan, I. ; Lomas T () Self-transcendence as a buffer against COVID-19 suffering: The development validation of the Self-Transcendence, m. e.a.s.u.r.e.-B. Frontiers 2021, 12, 4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong PT, P. ; Bowers V () Mature happiness global wellbeing in difficult times In, N.R. Silton (Ed.), Scientific concepts behind happiness, kindness, and empathy in contemporary society (pp. 112-134). IGI Global. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wong PT, P.; Cowden, R.G.; Mayer, C.-H. ; Bowers VL () Shifting the paradigm of positive psychology: Toward an existential positive psychology of wellbeing In, A.H. Kemp & D. J. Edwards (Eds.), Broadening the scope of wellbeing science: Multidisciplinary and interdiscipinary perspectives on human flourishing and wellbeing (pp. 13-27). Palgrave Macmillan. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P. , & Gingras, D. Finding meaning and happiness while dying of cancer: Lessons on existential positive psychology [Review of the film Ikiru]. PsycCRITIQUES. [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P., Ho, L. S., Cowden, R. G., Mayer, C.-H., & Yang, F. (Eds.) (2023a). A new science of suffering, the wisdom of the soul, and the new behavioral economics of happiness: towards a general theory of wellbeing [Special Issue]. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/42594/a-new-science-of-suffering-the-wisdom-of-the-soul-and-the-new-behavioral-economics-of-happiness-towa.

- Wong, P. T. P., Ho, L. S., Cowden, R. G., Mayer, C.-H., & Yang, F. (Eds.) (2023b). A new science of suffering, the wisdom of the soul, and the new behavioral economics of happiness: towards a general theory of wellbeing [Editorial]. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10552563/.

- Wong PT, P. ; Laird D (in press) The suffering hypothesis: Viktor Frankl’s spiritual remedies recent developments In, C. McLafferty, Jr. and J. Levinson (Eds.), Logotherapy and Existential Analysis: Proceedings of the Viktor Frankl Institute of Logotherapy Frankl Institute Vienna (Vol. 2). Springer Research.

- Wong, P. T. P. The meaning of love and its bittersweet nature. International Review of Psychiatry 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P., Mayer, C.-H., & Arslan, G. (Eds.). COVID-19 and Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0): The new science of self-transcendence [Special Issue]. Frontier 2021s. https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/14988/covid-19-and-existential-positive-psychology-pp20-the-new-science-of-self-transcendence.

- Wong, P. T. P. , & Yu, T. T. F. Existential suffering in palliative care: An existential positive psychology perspective. Medicina 2021, 57, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J. , Lee, M., LeSuer, W., Barr, P., Newton, K., & Poloma, M. Altruism and existential well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life 2017, 12, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).