1. Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of visual impairment, particularly in developed nations.[

1,

2,

3] As shown in several large clinical trials,[

4,

5,

6] visual outcomes in patients with macular neovascularization (MNV) secondary to AMD have significantly improved since the introduction of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treatment, which is now the first-line treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD). Although the need for long-term continuous treatment is a burden, the use of treat and extend regimens (TAE: shortened dosing intervals for active disease and extended dosing intervals for inactive disease) reduces patient visits and administrations compared to fixed dosing and maintains visual outcomes compared to PRN (dosing at exacerbations).[

7,

8]

However, a certain percentage of patients with nAMD are refractory to frequent anti-VEGF treatment over a long period. For example, in the VIEW1/VIEW2 trials, active exudation persisted in approximately 19.7% and 36.6% of patients who received aflibercept treatment every 4 or 8 weeks for 1 year. [

9] In a prospective multiple-center study in Japan, the percentage of patients requiring monthly dosing after 2 years ranged from 16.5%–20.6%,[

10] and 33.3%-37.4% of patients required dosing every 8 weeks at 96 weeks.[

11] Continuous treatment of these patients imposes a significant burden on both the patient and physician, and there is great hope for alternative or additive treatment, which can extend the dosing interval.

Faricimab is a bispecific IgG1 antibody that targets VEGF-A and angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2), thereby suppressing conventional VEGF and Ang-2, which is involved in the regulation of vascular homeostasis, angiogenesis, and permeability.[

12,

13] Specifically, Ang-2 competes with Ang-1 in binding Tie-2 receptors. While Ang-1/Tie2 signal promotes adhesion among endothelial cells, adhesion between endothelial cells and pericytes, and reduce sensitivity to VEGF, excessive Ang-2 and subsequent block of this signal lead to pericyte loss, vascular leakage, and inflammation.[

14] The process is implicated in the pathogenesis of retinal vascular disease including nAMD. Several clinical trials, including those focused on nAMD, have demonstrated the efficacy of the anti Ang-2 approach and have shown sustained clinical effect when compared to conventional anti-VEGF agents.[

15]

In a clinical trial of patients with nAMD, faricimab exhibited efficacy, longer dosing intervals, and safety that were non-inferior to those of aflibercept.[

16] In real-world studies dealing patients who were resistant to aflibercept, switching to faricimab extended the dosing interval from 5.9 to 7.5 weeks or from 4.4 to 8.7 weeks, with success rates ranging from 29.1% to 40.8%.[

17,

18] Thus, switching to faricimab seems a promising option for refractory cases. However, these studies did not identify predictive factors for the success of switching. Since faricimab is more expensive than other anti-VEGF agents, it is vital to identify patients who can receive the most benefit from the drug to ensure the appropriate allocation of resources.

In this study, we focused on type 1 MNV, subretinal pigment epithelium neovascularization, to minimize the confounding effect of lesion status, and examined detailed background information to determine which patients would benefit from switching to faricimab.

2. Materials and Methods

Study participants

This retrospective cohort study included patients who were continuously treated with intravitreal aflibercept (IVA) for nAMD at Nagasaki University Hospital and Nagasaki Genbaku Hospital according to the TAE regimen, and who were switched to faricimab between August 2022 and March 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age over 50 years, 2) active type 1 MNV, 3) received IVA treatment with a TAE regimen, 4) an interval of 8 weeks or less between the last three doses of IVA, 5) a history of five or more consecutive IVA treatments, 6) switched to faricimab, and 7) at least 24 weeks of observation after switching. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) axial length greater than 26.5 mm, 2) presence of inflammatory or hereditary diseases that may induce MNV; 3) previous treatment for MNV; 4) any other retinal or optic nerve disease; and 5) previous treatment for MNV at institutions other than the two centers of interest.

Intervention and observation procedure

We used a TAE regimen. The patients were initially treated with three monthly injections of aflibercept (loading phase), followed by additional injections. When switching to faricimab, the TAE regimen was continued without a loading phase, starting at the pretreatment IVA interval. Extension and shortening were determined by the presence of exudative changes such as subretinal or intraretinal fluid. Switching back to aflibercept was performed after the fifth dose of faricimab if the injection interval could not be maintained for > 8 weeks.

Patients underwent comprehensive examinations, including measurement of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), axial length (IOLMaster 500; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA), fundus photography, spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT, Spectralis; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany), fluorescein angiography, indocyanine green angiography, fundus autofluorescence imaging (HRA2; Heidelberg Engineering), and OCT-angiography (Avanti; Optovue, US) for diagnosis. BCVA was measured using Landolt C and converted to the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) for statistical analysis; BCVA and SD-OCT measurements were performed at each visit. The SD-OCT images included 30° horizontal regular and enhanced depth scans through the fovea and 15 raster scans covering a 20°×15° oblong rectangle. Subretinal hemorrhage (SRH) was detected within 6 mm of the center based on fundus photographs and SD-OCT. Central choroidal thickness (CCT) was measured as the distance between the outer edge of Bruch's membrane and the scleral interface using enhanced depth imaging scans. Pigment epithelium detachment (PED) height was defined as the distance between the outer edge of the retinal pigment epithelium and the inner edge of the Bruch's membrane, and the maximum height of the PED within 6 mm of the center was recorded. The presence of the ellipsoid zone (EZ) was evaluated on vertical and raster scans within 1 mm of the center. Disease type was determined using angiography, SD-OCT, OCT angiography, and fundus photography. Fundus angiography was performed before or immediately after the start of treatment unless the patient had an allergy to the contrast agent or other systemic risks. The nomenclature for nAMD followed a previous study.[

19]

Two graders (J.I. and J.K.) blinded to the outcome performed the measurements and grading. The average of the measurements was used for the analysis and discrepancies in grading were resolved through discussion.

Main outcome measure

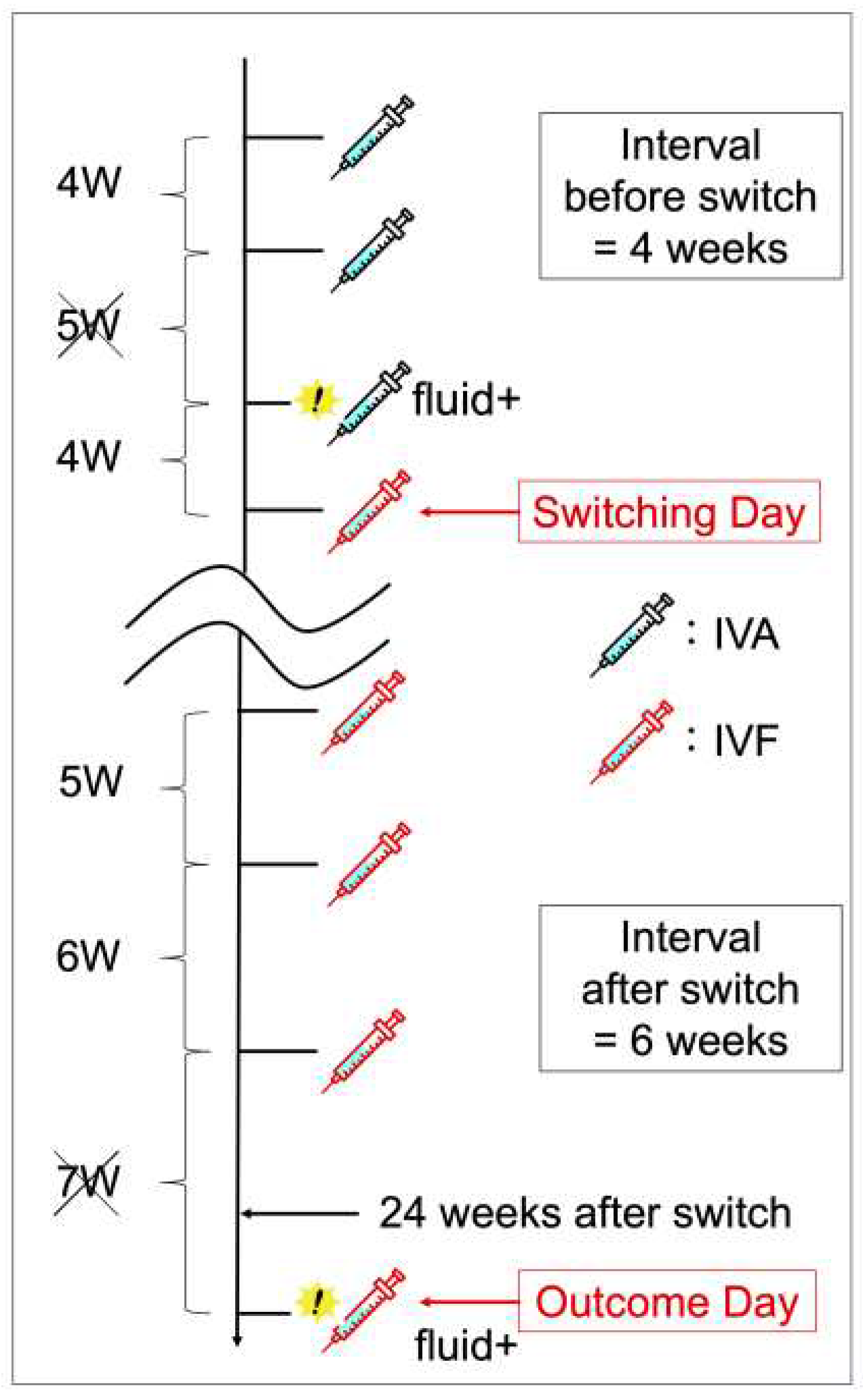

The main outcome was successful switching, defined as at least a two-week extension of the treatment interval compared with the treatment interval before switching. Specifically, the pre-switch interval was defined as the longest interval without disease activity among the three aflibercept doses before the switch date. The post-switch interval was defined as the longest interval without disease activity between the last three faricimab doses before the outcome date. The outcome date was defined as the date of the 6-month follow-up visit or switchback. (Figure 1)

Statistical analysis

Values are presented as the median and interquartile range. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR,[

20] a modified version of the R commander for statistical functions commonly used in biostatistics. P-values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test, Fisher's exact test, and Cochran-Armitage trend test. Logistic regression analysis was performed using age, sex, presence of polypoidal lesions, history of cataract surgery and photodynamic therapy (PDT), number of previous anti-VEGF treatments, dosing interval before switching, baseline BCVA, central retinal thickness (CRT), CCT, maximum PED height, presence of exudative changes at switching, presence of SRH, and EZ status as independent factors and successful extension as a dependent factor.

3. Results

According to these criteria, we enrolled 44 eyes with aflibercept-refractory nAMD during a specified period. One eye was excluded because of a decline in systemic diseases unrelated to the MNV treatment, and the final analysis included 43 eyes.

Table 1 presents the background data of the 43 eyes. The study included 16 women and 27 men. The median age was 80.0 years (interquartile range: 73.0 - 84.5), 37.2% of the patients had a history of PDT, and the median number of previous anti-VEGF injections was 34.0 (20.5 - 52.5). Of the last 3 treatment intervals before switching, the median of the longest interval without exudative changes was 5.0 (4.0 - 6.0) weeks, with a logMAR acuity of 0.16 (0.05 - 0.30). Compared to those without polypoidal lesions, the polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV) population was younger (P = 0.014), consisted of more males (P = 0.018), had a more history of PDT (P = 0.006), and received fewer injections (P = 0.036). Prior to the switch, the values for CRT, CCT, maximum PED height, presence of SRH, and EZ disruption were comparable regardless of the presence or absence of polypoid lesions.

The successful switching group consisted of 14 eyes (32.6%) in which the treatment interval was extended by at least 2 weeks compared with the pre-switch interval. This group had fewer polypoidal lesions (P = 0.035), more previous cataract surgeries (P = 0.022), fewer previous PDT (P = 0.045), and a shorter pre-switch dosing interval (P = 0.035) (

Table 2). Approximately half of the patients in the successful switching group showed no exudative changes at baseline, whereas the unsuccessful switching group showed more exudative changes at baseline (P = 0.040).

Logistic regression analysis identified three factors associated with successful switching: absence of polypoid lesions, CCT, and pre-switching interval. The odds ratios were 0.109 (95% CI, 0.019 - 0.642, P = 0.02) for polypoid lesions, 0.888 (95% CI, 0.789 - 0.999, P = 0.048) for every 10 μm increase in CCT, and 0.381 (95% CI, 0.168 - 0.864, P = 0.021) when the pre-switching dosing interval was extended by one week (

Table 3).

The visual and morphological outcomes and treatment intervals over 6 months are shown in

Table 4. The successfully extended group showed improvements in visual and overall morphological parameters. Visual acuity improved from 0.13 to 0.08 (logMAR), and CRT (277.0 to 248.0 μm), CCT (149.5 to 144.5 μm), and PED (178.5 to 152.5 μm) decreased at 6 months. Furthermore, the dosing interval was extended from 5 to 8 weeks. In the group that failed to extend the dosing interval, CRT worsened (319.0 to 332.0 μm), but CCT (190.0 to 190.0 μm) and PED (198.0 to 182.0 μm) did not worsen, and visual acuity was maintained at 6 months (0.16 to 0.16). In the successful extension group, 80% of patients experienced no or reduced exudative changes throughout the study period, whereas more than 60% of patients in the unsuccessful extension group experienced worsening exudative changes.

Five of the 43 eyes (11.6%) required faricimab injections for less than 8-week interval. One eye was switched back to aflibercept on day 105 and four eyes were switched back to aflibercept at the 6-month outcome date. All switchback cases had a polypoid lesion. They also had more previous PDT and tended to have a larger median CRT, but these differences were not statistically significant (

Table 5). Logistic regression analysis did not reveal any significant background characteristics.

No adverse events such as retinal pigment epithelium tear, subretinal hemorrhage, intraocular inflammation, and cardiovascular event were observed in any patient after switching to faricimab.

3.2. Figures

Figure 1.

An example of how the pre- and post-switching dosing intervals is defined. Of the three dosing intervals before switching, the longest interval without disease activity is 4 weeks, and of the three dosing intervals going back from the outcome date, the longest interval without disease activity is 6 weeks. Since the dosing interval is extended from 4–6 weeks, this case constitutes a successful switching. IVA, intravitreal aflibercept; IVF, intravitreal faricimab.

Figure 1.

An example of how the pre- and post-switching dosing intervals is defined. Of the three dosing intervals before switching, the longest interval without disease activity is 4 weeks, and of the three dosing intervals going back from the outcome date, the longest interval without disease activity is 6 weeks. Since the dosing interval is extended from 4–6 weeks, this case constitutes a successful switching. IVA, intravitreal aflibercept; IVF, intravitreal faricimab.

4. Discussion

Factors affecting successful switching.

This is the first report to identify the factors associated with the success of switching to faricimab for aflibercept-refractory type 1 MNV. Several reports have indicated that switching from aflibercept to faricimab for refractory nAMD can result in improved visual outcomes and longer dosing intervals in many cases.[

17,

18,

21,

22,

23]。However, the factors contributing to the success of the switch have not been analyzed due to the retrospective nature of the studies, short-term follow-up, and the relatively small sample size of participants. The participants in this study received treatment only at the designated facility for an extended period before switching. This enabled the retrospective collection of information on the background characteristics of the target population. In addition, the results of the regression analysis were made clearer by limiting the disease type to type 1 in order to minimize confounding effects. Since faricimab is more expensive than other anti-VEGF drugs, it is important to identify patients who would benefit most from this drug at the time before switching.

Logistic regression analysis revealed that the extension was more likely to be successful when the treatment interval before switching was short. One explanation for why faricimab was more effective in patients with a shorter treatment interval is that the anti-Ang-2 effect is more critical in populations that are highly resistant or tachyphylactic[

24] to conventional aflibercept treatment. Elevated Ang-2 and subsequent inactivation of Tie-2 cause increased sensitivity to VEGF in endothelial cells.[

25,

26] Anti-Ang-2 effect of faricimab may cancel hypersensitivity to VEGF in these patients. Switching to faricimab is recommended for patients with short dosing intervals before switching.

The absence of polypoidal lesions and thinner CCT were also identified as background factors for successful switching. This is rather surprising because Ang-2 levels in the aqueous humor are higher in pachychoroid-associated MNV[

27] than in drusen-associated MNV.[

28] We assumed that faricimab improves the elevated Ang-2 levels in patients with thick CCT and is more effective. We also assumed that patients with polypoidal lesions would show similar responses because lesions are generally observed in patients with a thick choroid.[

29] However, the results of the present study were contradictory. A possible explanation is that patients with polypoidal lesions and a thick choroid tended to undergo PDT before switching (15/29 patients with polypoidal lesions). Ang-2 inhibits Tie-2 signaling by competitively inhibiting Ang-1; Ang-2 inhibition promotes Ang-1-Tie-2 binding and stabilizes vessels via the activation of Tie-2 signaling.[

12] This mechanism may be less advantageous for anomalous vessels occluded or degenerated by PDT. The findings of this study support switching to faricimab treatment for non-PCV cases with thin CCT in refractory cases with a long treatment history.

Although not identified in the regression analysis, these results suggested that switching may be particularly effective in eyes with a history of cataract surgery. Ang-2 is a cytokine involved in many aspects of inflammatory diseases as well as angiogenesis, [

30] in the acute and chronic phases of intraocular surgery, inflammation may contribute to increased intraocular expression of Ang-2. We hypothesize that pseudophakic eyes have el-evated Ang-2 levels compared to phakic eyes, which explains the good response to the anti-Ang-2 effect of faricimab. However, no investigations have been conducted on changes in Ang-2 expression levels before and after intraocular surgery. Further inves-tigation is required to understand the association between a history of intraocular surgery and the effects of intraocular Ang-2.

Switching success rate.

Similar reports in Japan have shown success rates ranging from 29.1%–40.8%. This is consistent with the 32.6% reported in this study.[

17,

18] The finding that 30% of patients who are refractory to IVA can nearly double their treatment interval at six months is a great hope for patients who receive frequent conventional treatment. Additionally, the worsening of visual acuity in the population that failed to switch was minimal, and about 10% of the cases resulted in switchback due to unacceptable switching. Switching is a relatively safe option in refractory cases.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that switching to faricimab is effective in approximately 30% of the aflibercept-refractory population and that switching to faricimab is more successful in eyes without polypoidal lesions, thinner CCT, and short pre-switch intervals. Failure to switch was not strongly associated with worsening of parameters, suggesting that switching is a safe option for treatment-resistant patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and A.O.; methodology, A.M.,A.O. and J.K.; validation, Y.H. and R.M.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, J.I., J.K., A.Y., E.T., Y.H. and R.M.; resources, A.O. and J.K.; data curation, A.M., J.I., and J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and J.I.; writing—review and editing, A.O., J.K., A.Y., E.T. and T.K.; visualization, A.M. and J.I.; supervision, A.O. and T.K.; project administration, A.O. and J.K.; funding acquisition, A.O.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant-in-aid for scientific research (no. 22K09793) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo, Japan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study design was approved by the institutional review board of Nagasaki University Hospital, Japan (protocol code: 23051506; date of approval: 15 May 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

The ethics committee waived the requirement for written informed consent, given the study’s retrospective nature; instead, patients were allowed “opt-out” consent.

Data Availability Statement Access to data and data analysis

A. Machida had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of data analysis. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, A.O. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions that include information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Reprint requests

Akio Oishi, MD, PhD, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Nagasaki University, Sakamoto 1-7-1, Nagasaki 852-8102, Japan; e-mail: akio.oishi@nagasaki-u.ac.jp:.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

Akio Oishi received personal fees from Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd (Tokyo, Japan), Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), and Novartis Pharma K.K. (Tokyo, Japan). Eiko Tsuiki received personal fees from Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), and Novartis Pharma K.K. (Tokyo, Japan). Takashi Kitaoka received personal fees from Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), Novartis Pharma K.K. (Tokyo, Japan), and Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) and grants from Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

References

- Bressler, N.M. Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of blindness. Jama 2004, 291, 1900–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, P.T. Age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2006, 355, 1474–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.S.; Mitchell, P.; Seddon, J.M.; Holz, F.G.; Wong, T.Y. Age-related macular degeneration. The Lancet 2012, 379, 1728–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.M.; Kaiser, P.K.; Michels, M.; Soubrane, G.; Heier, J.S.; Kim, R.Y.; Sy, J.P.; Schneider, S.; Group, A.S. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2006, 355, 1432–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, P.J.; Brown, D.M.; Heier, J.S.; Boyer, D.S.; Kaiser, P.K.; Chung, C.Y.; Kim, R.Y. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2006, 355, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Investigators, I.S.; Chakravarthy, U.; Harding, S.P.; Rogers, C.A.; Downes, S.M.; Lotery, A.J.; Wordsworth, S.; Reeves, B.C. Ranibizumab versus bevacizumab to treat neovascular age-related macular degeneration: one-year findings from the IVAN randomized trial. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 1399–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, D.; Deonarain, D.M.; Gould, J.; Sothivannan, A.; Phillips, M.R.; Sarohia, G.S.; Sivaprasad, S.; Wykoff, C.C.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Sarraf, D.; et al. Efficacy, safety, and treatment burden of treat-and-extend versus alternative anti-VEGF regimens for nAMD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eye (Lond) 2023, 37, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wykoff, C.C.; Ou, W.C.; Brown, D.M.; Croft, D.E.; Wang, R.; Payne, J.F.; Clark, W.L.; Abdelfattah, N.S.; Sadda, S.R. Randomized Trial of Treat-and-Extend versus Monthly Dosing for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: 2-Year Results of the TREX-AMD Study. Ophthalmol Retina 2017, 1, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heier, J.S.; Brown, D.M.; Chong, V.; Korobelnik, J.F.; Kaiser, P.K.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Kirchhof, B.; Ho, A.; Ogura, Y.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; et al. Intravitreal aflibercept (VEGF trap-eye) in wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 2537–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruko, I.; Ogasawara, M.; Yamamoto, A.; Itagaki, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Arakawa, H.; Nakayama, M.; Koizumi, H.; Okada, A.A.; Sekiryu, T.; et al. Two-Year Outcomes of Treat-and-Extend Intravitreal Aflibercept for Exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Prospective Study. Ophthalmol Retina 2020, 4, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohji, M.; Takahashi, K.; Okada, A.A.; Kobayashi, M.; Matsuda, Y.; Terano, Y. Efficacy and Safety of Intravitreal Aflibercept Treat-and-Extend Regimens in Exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration: 52- and 96-Week Findings from ALTAIR : A Randomized Controlled Trial. Adv Ther 2020, 37, 1173–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, H.G.; Koh, G.Y.; Thurston, G.; Alitalo, K. Control of vascular morphogenesis and homeostasis through the angiopoietin-Tie system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009, 10, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heier, J.S.; Singh, R.P.; Wykoff, C.C.; Csaky, K.G.; Lai, T.Y.Y.; Loewenstein, A.; Schlottmann, P.G.; Paris, L.P.; Westenskow, P.D.; Quezada-Ruiz, C. THE ANGIOPOIETIN/TIE PATHWAY IN RETINAL VASCULAR DISEASES: A Review. Retina 2021, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Aziz, A.A.; Shafi, N.A.; Abbas, T.; Khanani, A.M. Targeting Angiopoietin in Retinal Vascular Diseases: A Literature Review and Summary of Clinical Trials Involving Faricimab. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberski, S.; Wichrowska, M.; Kocięcki, J. Aflibercept versus Faricimab in the Treatment of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Diabetic Macular Edema: A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heier, J.S.; Khanani, A.M.; Quezada Ruiz, C.; Basu, K.; Ferrone, P.J.; Brittain, C.; Figueroa, M.S.; Lin, H.; Holz, F.G.; Patel, V.; et al. Efficacy, durability, and safety of intravitreal faricimab up to every 16 weeks for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (TENAYA and LUCERNE): two randomised, double-masked, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet 2022, 399, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, K.; Itagaki, K.; Hashiya, N.; Wakugawa, S.; Tanaka, K.; Nakayama, M.; Yamamoto, A.; Mukai, R.; Honjyo, J.; Maruko, I.; et al. Six-month outcomes of switching from aflibercept to faricimab in refractory cases of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, M.; Miki, A.; Kamimura, A.; Okuda, M.; Matsumiya, W.; Imai, H.; Kusuhara, S.; Nakamura, M. Short-Term Outcomes of Faricimab Treatment in Aflibercept-Refractory Eyes with Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaide, R.F.; Jaffe, G.J.; Sarraf, D.; Freund, K.B.; Sadda, S.R.; Staurenghi, G.; Waheed, N.K.; Chakravarthy, U.; Rosenfeld, P.J.; Holz, F.G.; et al. Consensus Nomenclature for Reporting Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Data: Consensus on Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Nomenclature Study Group. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, 616–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software 'EZR' for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, R.B.; Rush, S.W. Intravitreal Faricimab for Aflibercept-Resistant Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Clin Ophthalmol 2022, 16, 4041–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondi, R.; Falfeli, T.; Bogdanova-Bennet, A.; Varma, D.; Habib, M.; Kotagiri, A.; Steel, D.H.; Grinton, M. Real-world outcomes of treatment resistant neovascular-age related macular degeneration switched from Aflibercept to Faricimab. Ophthalmol Retina 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamiya, R.; Hata, M.; Tanaka, A.; Tsuchikawa, M.; Ueda-Arakawa, N.; Tamura, H.; Miyata, M.; Takahashi, A.; Kido, A.; Muraoka, Y.; et al. Therapeutic effects of faricimab on aflibercept-refractory age-related macular degeneration. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 21128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, J.; Sun, X. Resistance to anti-VEGF therapy in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a comprehensive review. Drug Des Devel Ther 2016, 10, 1857–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshima, Y.; Deering, T.; Oshima, S.; Nambu, H.; Reddy, P.S.; Kaleko, M.; Connelly, S.; Hackett, S.F.; Campochiaro, P.A. Angiopoietin-2 enhances retinal vessel sensitivity to vascular endothelial growth factor. J Cell Physiol 2004, 199, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.; Cree, I.A.; Alexander, R.; Turowski, P.; Ockrim, Z.; Patel, J.; Boyd, S.R.; Joussen, A.M.; Ziemssen, F.; Hykin, P.G.; et al. Angiopoietin modulation of vascular endothelial growth factor: Effects on retinal endothelial cell permeability. Cytokine 2007, 40, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, C.E.; Freund, K.B. Pachychoroid neovasculopathy. Retina 2015, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoda, S.; Takahashi, H.; Inoue, Y.; Tan, X.; Tampo, H.; Arai, Y.; Yanagi, Y.; Kawashima, H. Cytokine profiles of macular neovascularization in the elderly based on a classification from a pachychoroid/drusen perspective. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2022, 260, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.E.; Kang, S.W.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.T. Choroidal thickness in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and exudative age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, A.; Plate, K.H.; Reiss, Y. Angiopoietin-2: a multifaceted cytokine that functions in both angiogenesis and inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2015, 1347, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).