1. Introduction

A lot of structures (masses) may be found within the right heart chambers and may be evaluated using various imaging modalities, including echocardiography, computer tomography (CT), positron emission tomography–CT (PET-CT), cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging, scintigraphy or, even, invasive angiography [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. These masses can be normal bands, aberrant structures, or pathologic structures (tumors). Either normal or aberrant, they can mimic cardiac tumors, thus representing a diagnostic challenge sometimes. The normal variants typically appear in a classic location and exhibit the same signal intensity and enhancement characteristics with the normal myocardium. However, right heart tumors have altered signal intensity and enhancement characteristics, which involves the use of several imaging methods followed by excision or biopsy [

4].

These tumors can be primary (benign or malignant) or secondary (metastatic, usually malign). Primary malignant heart tumor are exceptionally rare, being less than 0.2% of cardiac tumors [

4]. In adults, around 75% of primary cardiac tumors are benign, a percentage that increases to 90% in children [

6]. It appears that about 80% of all benign primary cardiac tumors are rhabdomyomas and fibromas [

7]. Breast cancer, lymphoma, and melanoma are the most common metastatic cancers affecting the heart [

5]. Benign tumors may have a malignant counterpart [

8], such as myxoma (myxosarcoma), lipoma (liposarcoma), rhabdomyoma (rhabdomyosarcoma), angioma (angiosarcoma), fibroma (fibrosarcoma), schwannoma (malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor), etc. It seems that cardiac metastases (secondary malignant tumor) often involve the right side of the heart.

Right heart tumors are usually identified during a routine examination by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) or due to cardiac symptoms [

8]. Given their ability to mimic various cardiac pathologies, cardiac tumors may present with diverse clinical features. These clinical presentations are taken into consideration when a right heart tumor is detected on TTE or transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) examination.

It is crucial to recognize individual clinical contexts and settings, encompassing factors like medical history, age, gender, ethnicity/geography, and risk factors, before selecting an imaging method [

4,

9]. Historically significant features, such as fever, weight loss, fatigue, and paraneoplastic syndromes, along with phenomena like embolism, cardiac dysfunction resulting from arrhythmias or valvular insufficiency, and hemodynamic compromise, play a pivotal role. Some tumors occur in younger patients, whereas others occur in older ones [

9]. Risk factors like intravenous drug abuse, recent invasive medical procedures, impaired systolic function, atrial fibrillation or history of thrombotic disease are important when deciding on an appropriate imaging modality or if imaging findings are inconclusive.

Right heart tumors might involve not only the walls (myocardium, endocardium and pericardium), but also the valves, and cardiac chambers [

4]. A cardiac mass could be visible on the endocardium but could be invasively in the myocardium (or pericardium).

Imaging methods often play a complementary role; therefore, an integrated imaging approach is recommended. For example, CT and CMR provide high-resolution anatomic information, while PET-CT can distinguish between benign and malignant tumors by metabolic activity of tumors (functional information). The multimodal imaging approach for the right heart tumors is the first step towards an appropriate diagnostic, followed by the staging, the follow-up and/or imaging guided excision. Anatomo-pathological diagnosis must always be confirmed by endomyocardial or excisional biopsy.

However, prior to biopsy or excision, the multimodal imaging examination has an important role in the differential diagnosis of cardiac tumors. Unfortunately, there is lack of standardization of these imaging modalities with regard to an algorithm because it depends on the locally available expertise of each center or preferred imaging modality. Therefore, the subject deserves thorough discussion.

2. Imaging Modalities for Assessing Right Heart Tumors

Cardiac imaging has undergone significant advancements over the last decades. Multimodality imaging facilitates differential diagnosis of heart right cardiac tumors [

4]. Some authors consider that, when available, all imaging methods should be used, especially in certain cardiac tumors like myxofibrosarcoma [

7,

10].

Regardless of the type of cardiac tumor, a multimodality-imaging algorithm has the following objectives [

4]:

1. Identify, localize, and describe the tumor (including its origin, attachments, size, morphology, mobility, hemodynamic significance, their tissue characteristics and vascularity);

2. Differentiate the tumor from other cardiac pathologic conditions through a comprehensive differential diagnosis;

3. Assess the secondary consequences of this tumor;

4. Evaluate whether the tumor is primary or secondary.

The utility of the main imaging methods in right heart tumors is detailed in

Table 1.

2.1. Chest Radiography

Chest radiography is no longer recommended in the evaluation of right heart tumors, but is important in differential diagnosis of murmurs, dyspnea, or signs of right heart failure. In patients with these complaints, it could reveal changes such as cardiomegaly, enlargement of right chambers or a dilated pulmonary artery. Depending on the presentation of right heart tumors, the chest X-ray can therefore be part of the imaging evaluation of these patients.

2.2. Echocardiography

Bi-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography is the first-line non-invasive imaging modality used in heart tumors evaluation. It detects cardiac tumors with 90% sensitivity and 95% specificity [

7,

11].

It can be used as screening imaging method, but right heart tumors could be an incidental finding during routine echocardiographic examination. This imaging technique is widely available (accessible), portable, easy to perform, even at the patient’s bedside and in those who are hemodynamically unstable. It is safe, repeatable without any consequence, cost effective, has a good spatial resolution (higher with TEE) and an excellent temporal resolution. TEE is more sensitive in identifying tumors less than <5 mm compared with TTE. Therefore, comparing with TTE, TEE is better for detection, location and mobility of cardiac tumors and equal for hemodynamic impact, compromising as compression/destruction/distortion of cardiac structures [

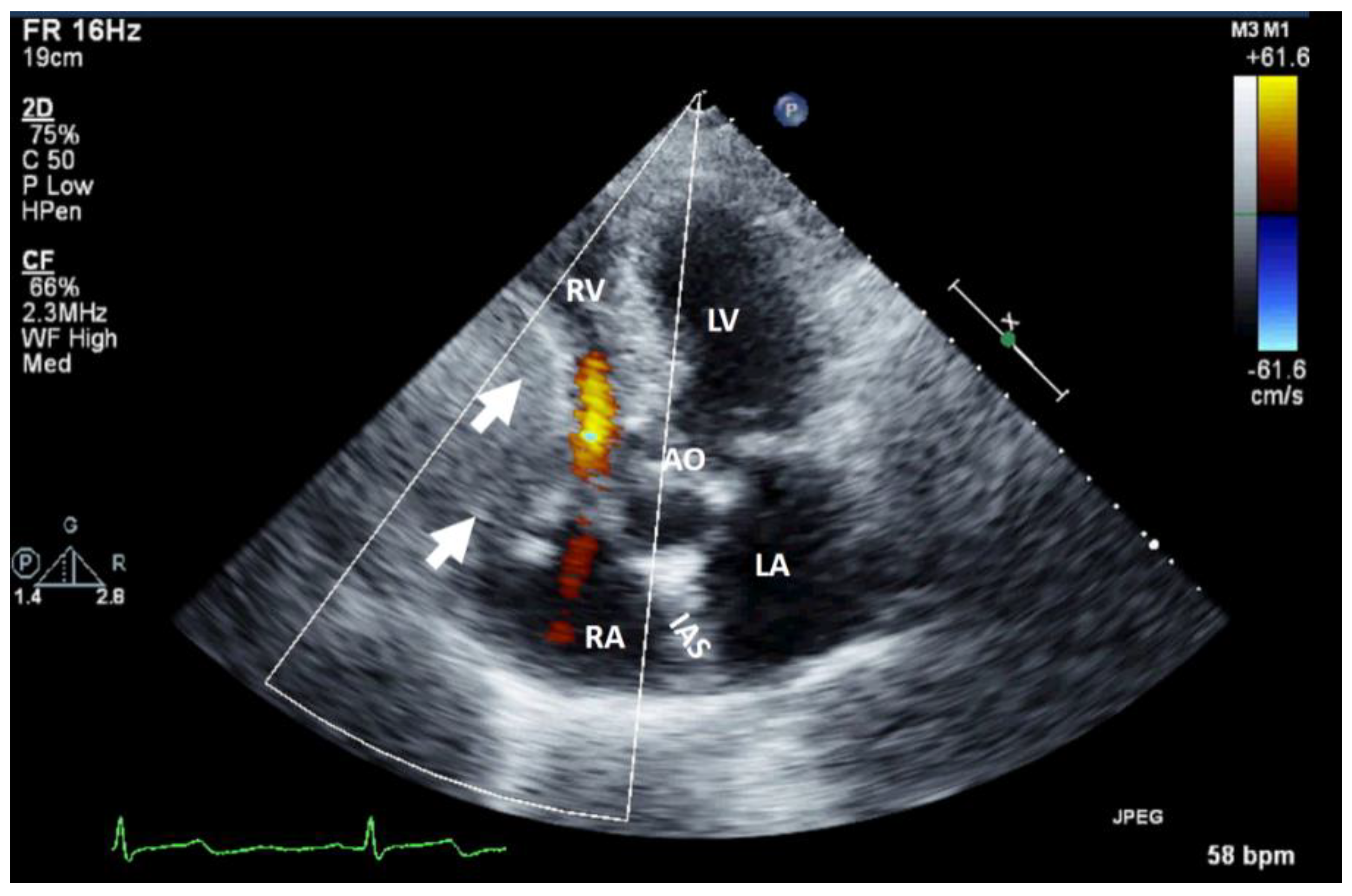

12]. In some cases, the mass effect of a non-cardiac tumor severely compromises cardiac hemodynamics (

Figure 1).

The echocardiography with ultrasound-enhancing agents is the best modality for tissue characterization [

13]. Bi-dimensional TTE may sometimes overrate the size of myxomas or very soft tumors (myxoid or gelatinous type mass) due to his distensibility, mobility or irregular shape, especially when compared to three-dimensional TEE. However, most frequently, the size of the tumor is appropriately assessed by TTE. The site and the modality of tumor attachment, a useful clue to define the type of cardiac tumor, could be determined easily by TEE (especially 3D). For example, right atrium angiosarcomas, characterized by a heterogenic mass with central necrosis on CT or CMR [

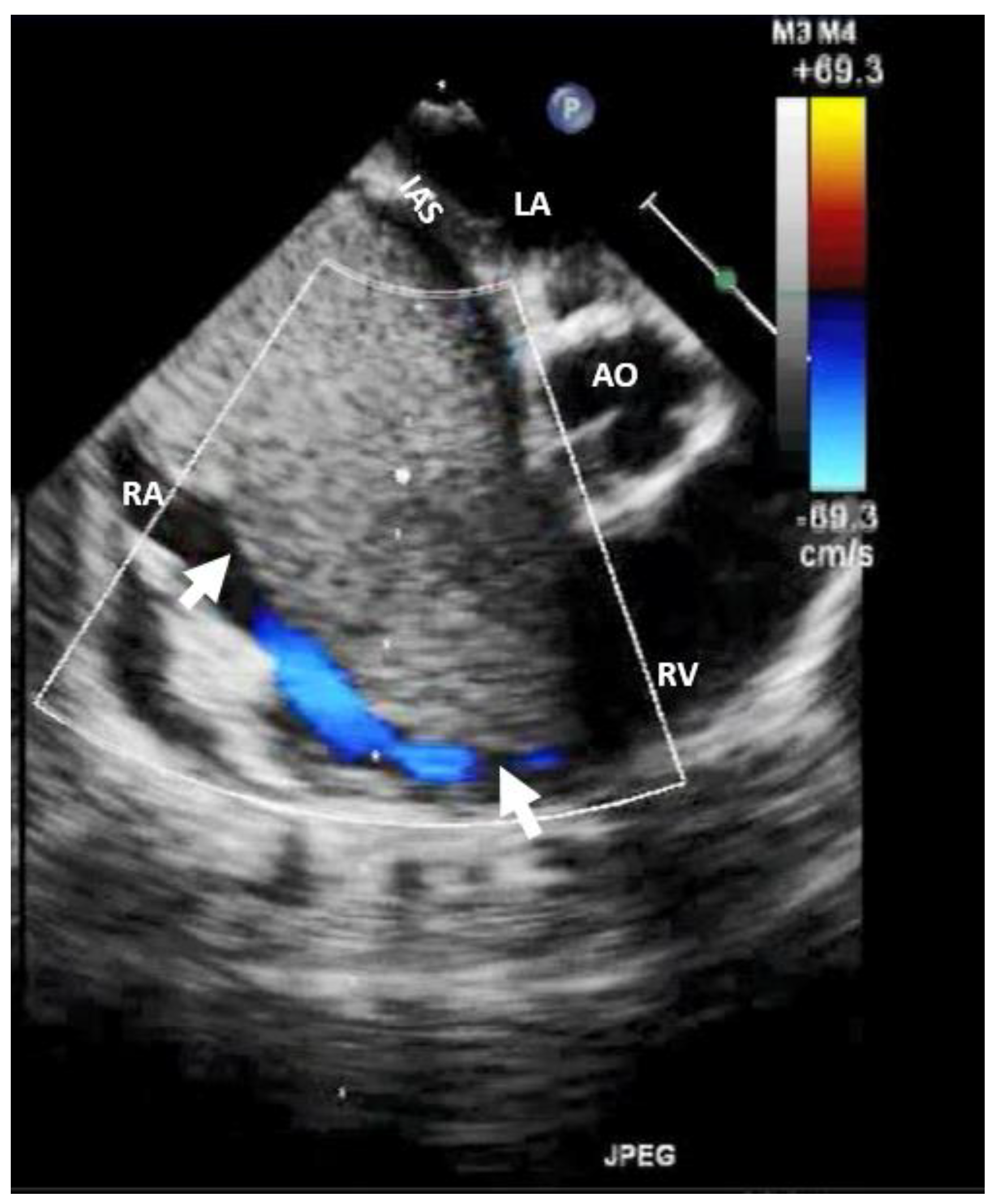

13], could be attached from any part of the right atrial wall, while myxoma (

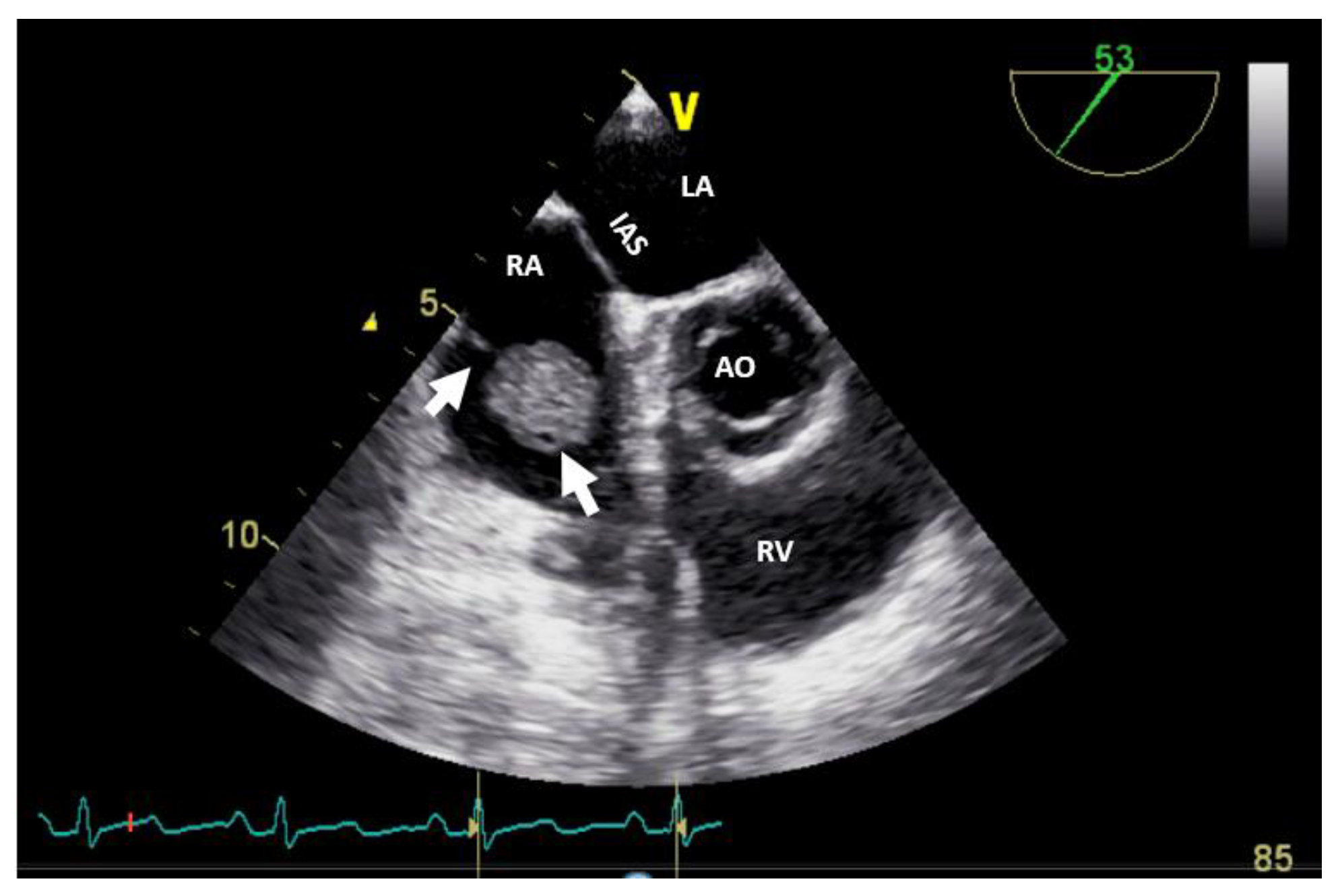

Figure 2) is usually situated in the fossa ovalis region of the atrial septum (most frequently on the left side).

Echocardiography is highly operator-dependent, has a limited acoustic window in some patients, a narrow field of view, and limited tissue characterization. In addition, TEE requires sedation and necessitates precautions in cases of severe esophageal disease but allows a better assessment of the right heat cavities comparing with TTE.

All echocardiographic modalities, including two or three-dimensional, Color Doppler imaging, spectral Doppler imaging, the use of agitated saline (

Video S2-Supplementary Materials) as well as ultrasound enhancement agents, are important in the diagnosis [

14] and even in guiding the biopsy procedure for histological examination. Besides guiding the potential therapeutic interventions, echocardiography is important for defining morphology, assessing size, observing dynamic appearance and evaluating functional abnormality and hemodynamic consequences before the other diagnosis imaging modalities.

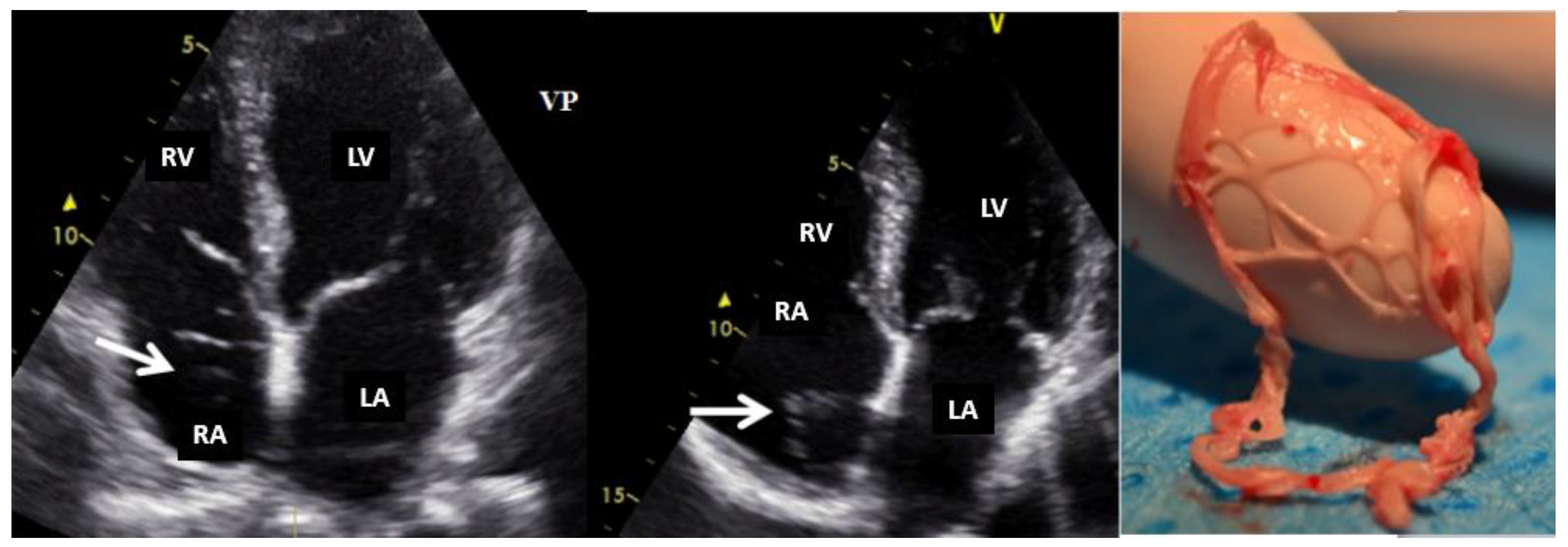

Normal or aberrant structures that may be present in the right cavities include the crista terminalis, Chiari network (

Figure 3) [

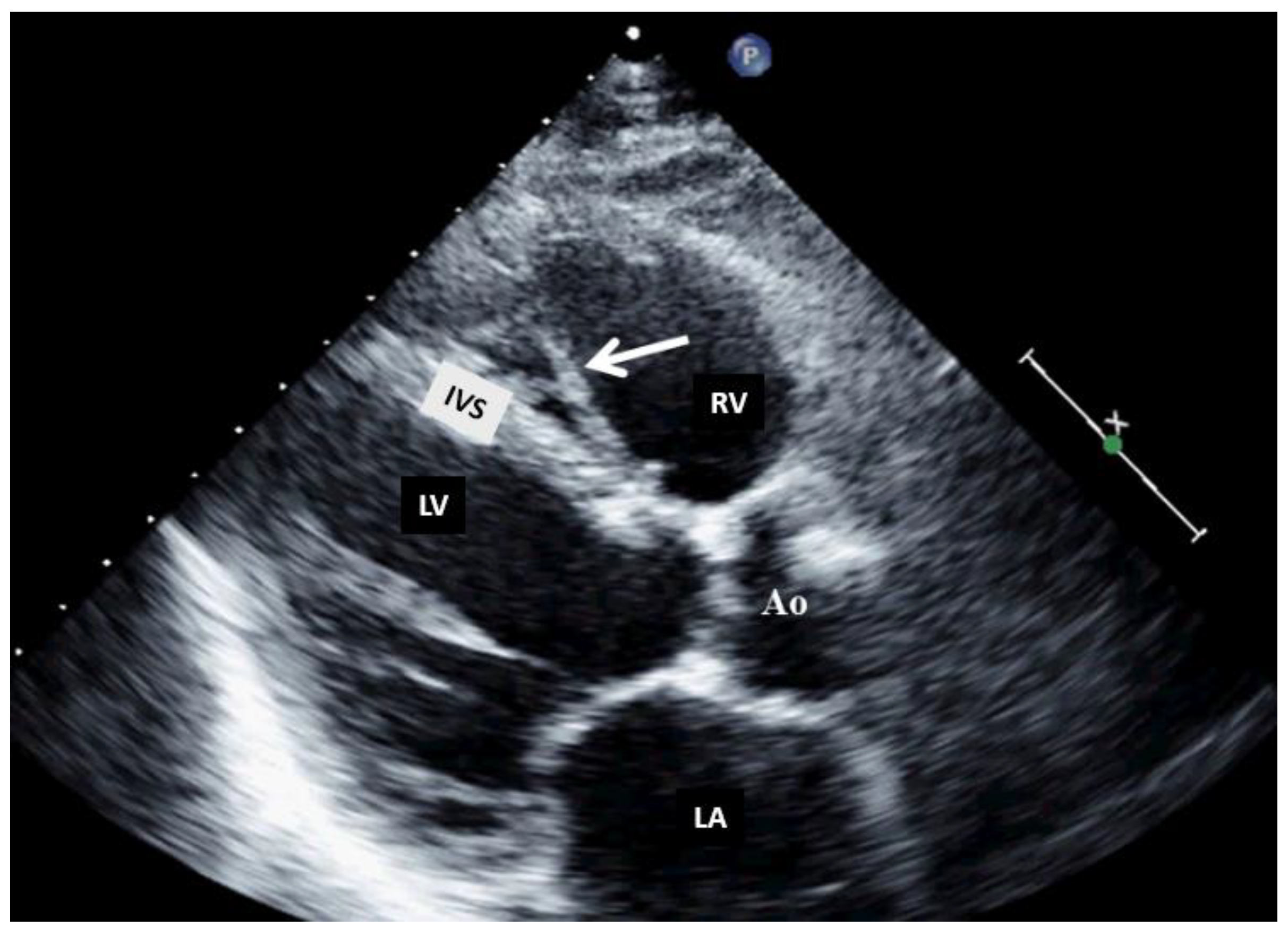

15], aberrant atrial bands in the right atrium, moderator band (

Figure 4), aberrant papillary muscles and accessory chordae tendineae in the right ventricle.

2.3. Cardiac Computer-Tomography

Computer-tomography is nowadays widely available, has a rapid turnaround time, a high isotropic spatial resolution (better then temporal resolution), superior anatomic depiction, a wide field of view, and multiplanar reconstruction capabilities. The strengths of cardiac CT include the assessment of intrathoracic anatomy, the coronary tree, and staging in malignant tumors [

9]. Unfortunately, this exam requires expertise, exposes individuals to radiation, involves the use of potential nephrotoxic iodinated contrast material and it is challenging to perform in patients who are hemodynamically unstable (as the sequences are breath-hold dependent) or in those with severe arrhythmias [

9].

Similar to echocardiography, right heart tumors might be an incidental finding during CT examination. After the echocardiography, cardiac CT, or CMR imaging are the second- line approach for assessing right heart tumors. In clinical settings (medical history, age, gender, ethnicity/geography and clinical risk factors), CT imaging can characterize tumor morphology, location and surrounding structural assessment. In addition, it allows a better assessment of the right cavities morphology and function compared to echocardiography.

Using multidetector cardiac CT in right heart tumors the following imaging features could be obtained [

16]:

1. Size of the mass (assessed in terms of diameters or volumes);

2. Tumor margins (circumscribed, micro-lobulated, obscured or partially hidden by adjacent tissue, indistinct or illdefined, and spiculated);

3. Invasiveness (the presence of the disruption of neighboring tissue and extension of the mass into the tissue);

4. Mass density defined as solid or mainly cystic and rated as hypo-, iso- or hyperdense (comparing with the normal cardiac muscle);

5. Presence of intra-mass calcifications;

6. Contrast uptake, defined as an increasing of at least 10 Hounsfield units in cardiac mass density compared with baseline;

7. Pericardial effusion.

In order to better define surgical approaches in cardiac tumors that might involve directly or abut coronary arteries, cardiac CT could be more useful than CMR.

Cardiac CT may be useful in differentiating benign from malignant cardiac tumor by irregular borders, invasive appearance, calcification, and Hounsfield units. However, imaging appearance may not always be predictive of malignancy. In addition, Hounsfield unit values overlap when differentiating hypoperfused myocardium from thrombus.

2.4. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging

If echocardiography serves as the initial step in cardiac tumors assessment, CMR is the preferred imaging modality following echocardiography. This preference stems from its ability to offer a comprehensive noninvasive evaluation using techniques such as late gadolinium enhancement, post-contrast long inversion time imaging, first-pass perfusion, and T1/T2 tissue characterization. This imaging method is most useful for tissue characterization and hemodynamics. However, it should be noted that CMR has some limitations, including ECG-gated image acquisition, dependency on breath-holding, lower image quality with arrhythmias, incompatibility to certain implants; a long acquisition time and unsuitability for patients with claustrophobia [

9].

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance is the standard imaging modality for functional quantification of the right heart tumors. It is an imaging technique with a high spatial and temporal resolution, it has an excellent depiction of anatomy, contrast resolution and tissue characterization, wide field of view, and multiplane acquisition and reconstruction capabilities. But, cardiac magnetic resonance has also limited accessibility, requires higher expertise, and a longer scan time. It is relatively expensive and not possible in patients with claustrophobia (unless intravenous anesthesia is administered), CMR-incompatible devices or severe renal dysfunction and it requires stable rhythm (this exam can be performed in hemodynamically stable patients). Even if it is rare, the risk of gadolinium deposition and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis exists. As for echocardiography and CT, right heart tumors could be an incidental finding on CMR; it allows a more accurate tissue characterization and tumor assessment, achieved with late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) sequences.

To date, CMR is considered the gold standard for volumes and myocardial mass assessment, especially of the right ventricle (i.e., cine imaging), and highly appropriate for flow and shunt quantification, allowing for hemodynamic assessment of valvular pathology (i.e., phase-contrast sequences) [

3].

Tissue characterization is a major strength of CMR, achieved using T1- and T2-weighted, perfusion, and early and late gadolinium-enhanced (with normal and long inversion times) sequences, as well as with parametric mapping techniques such as T1, T2, and T2 mapping. A right ventricle thrombus typically has low signal intensity with all sequences, including with late gadolinium-enhanced sequences at long inversion time, whereas a neoplasm shows variable signal intensity and contrast enhancement.

Prospective electrocardiographic triggering is adequate for morphologic evaluation, but retrospective electrocardiographic gating and the acquisition of data throughout the cardiac cycle are essential for dynamic and functional information. Right heart tumors require triphasic injection (e.g., contrast material injection followed by either a contrast material–saline mixture administered at the same flow rate or contrast material only administered at a slower flow rate than that of the first phase, followed by a saline bolus).

In addition, CMR can precisely delineate intra and extra-cardiac anatomy through several sequences.

2.5. Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography

The main strengths of the PET-CT, by assessing tumors’ metabolic activity, are staging of malignant tumors, optimization of biopsy site, deciding therapy by allowing radiotherapy planning and prognosis evaluation. Positron emission tomography has 100% sensitivity and 92% specificity in differentiating benign and malignant cardiac tumors [

7]. However, this imaging method has not a high spatial and temporal resolution, expose to radiation and requires a specific diet [

9].

As an imaging method, PET-CT could offer the following intensity and volume-based PET parameters of the cardiac mass [

9]:

These parameters enable differentiation between benign and malignant tumors; mean standardized uptake value, metabolic tumor volume and total lesion glycolysis are significantly higher in malignant than benign ones [

16].

PET-CT plays a crucial role in early detection of occult or distant metastasis. It proves valuable both before and after surgical resection, as it can unveil local metabolic activity persisting post-surgical excision in malignant heart tumors [

17]. Therefore, PET-CT has a prognostic role in both short and long -term follow-up.

In the case of rare malignancies like neuroendocrine tumors and cardiac paragangliomas, which could involve the heart, in order to better visualize and characterize these tumors, is useful to perform molecular imaging (with 68Ga–PET DOTA(0)-Tyr(3)-octreotate).

PET-CT and CMR can independently diagnose benign and malignant tumors. CMR has higher sensitivity comparing with FDG-PET-CT in distinguishing benign from malignant cardiac tumor, while FDG-PET-CT has higher specificity. The combination of these modalities increases the diagnostic capacity for malignant tumor [

18]. However, these imaging tools should be performed in specific clinical settings, such as involvement of great vessels or for disease-staging purposes [

19].

The integration of positron emission tomography with CT or CMR in a hybrid approach improves the detection of malignant tumors. For example, a hybrid CMR-18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET can identify a cardiac metastatic melanoma [

20]. 18F-FDG PET-CT is useful in distinguishing malignant from benign cardiac tumors when CT signs are inconclusive [

16]. In the context of neuroendocrine tumors and cardiac paragangliomas, 68Ga–PET DOTA (0)-Tyr (3)-octreotate is recommended for enhanced visualization and characterization through molecular imaging [

21].

2.6. Invasive Angiography

Invasive angiography is rarely used for right heart tumors diagnosis; it is merely reserved for specific cases (such as assessing the vascularization of tumors localized on tricuspid or pulmonary valve). This procedure has an excellent spatial and temporal resolution, provides a hemodynamic assessment of the tumors and allows therapeutic interventions at the same time. However, being an invasive procedure, it could be associated with the following risks: bleeding, pseudo-aneurysm, infection, stroke, arrhythmia, and allergic reactions.

3. Imaging Features of the Right Heart Tumors

Secondary cardiac tumors occur up to 40-fold more frequently than primary cardiac tumors [

7], which are exceedingly rare in clinical practice. Most frequently, secondary cardiac tumors involve the right heart.

Benign cardiac tumors may be associated with malignant arrhythmias, embolism or impaired hemodynamics, leading to life-threatening events, even if, from a histological point of view, these tumors have a good prognosis. However, anamnesis and clinical context together with appropriate and early diagnosis of these cardiac tumors is recommended. The utilization of multimodality imaging has improved the approach to diagnosis and management by enabling early detection and diagnosis, followed by timely effective treatment.

The diagnostic approach for right heart tumors is primarily based on differentiating them from other right heart masses such as thrombi (

Figure 5) or vegetation (

Figure 6). For example, in a patient known with neoplasia and port-a-cath (whether undergoing chemotherapy or not), a right heart masse discovered fortuity on TTE or TEE suggests, in a first step, a thrombus on the port-a-cath (

Figure 5). It was less likely to be a benign tumor, especially considering these patients underwent repeated TTE evaluations. The initiation of anticoagulant treatment can determine the disappearing of this mass. However, a differential diagnosis is mandatory, involving considerations of marantic endocarditis or metastases.

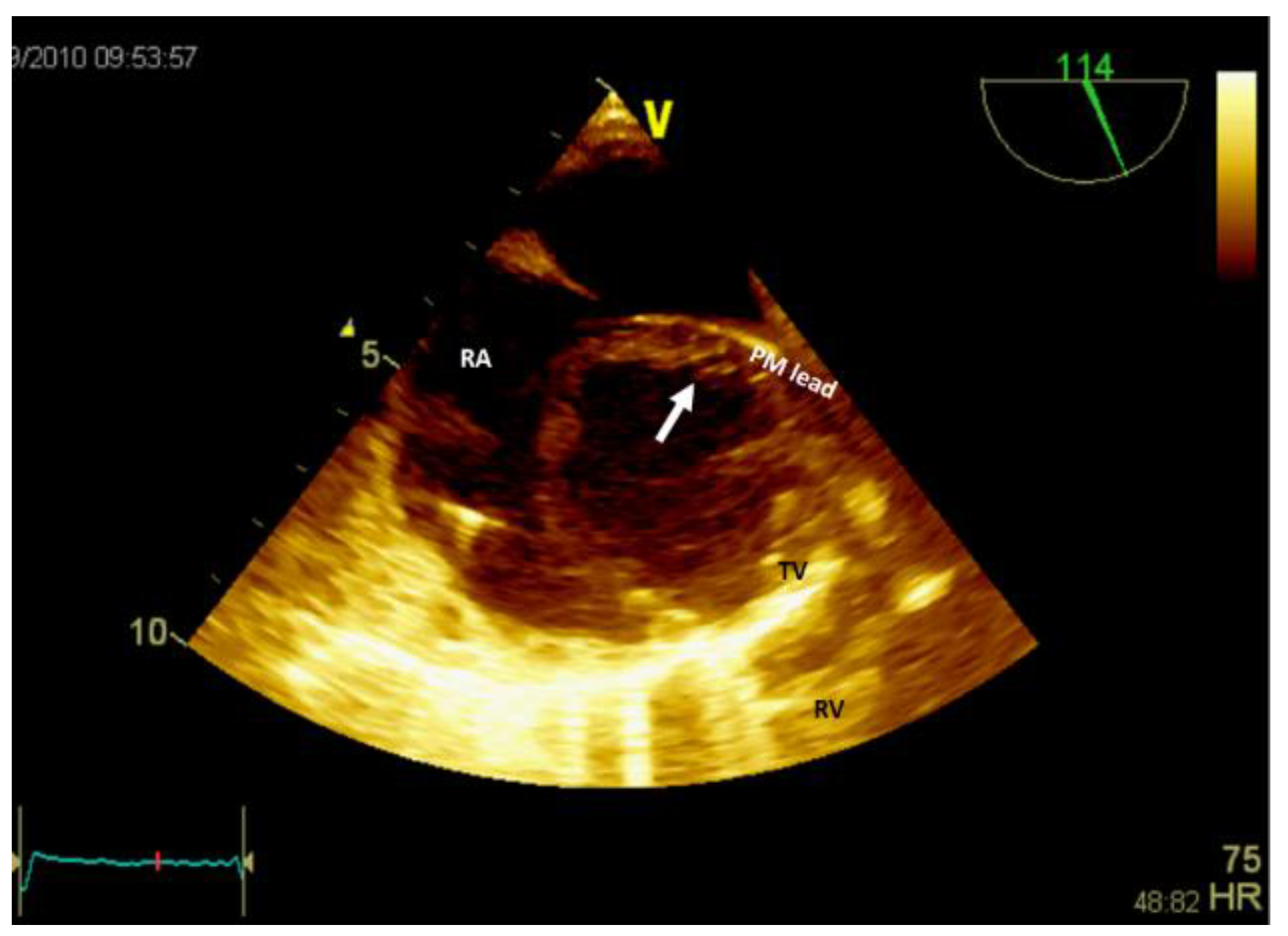

If the patient has a pacemaker or automatic implantable defibrillator, the first supposition in clinical suggestive context of endocarditis is a vegetation (

Figure 6,

Video S3 - Supplementary Materials). Differential diagnosis must include fibrin formations or thrombi. However, if the patient is already anticoagulated (due to atrial fibrillation) these diagnoses are less likely.

Secondly, using TTE and/or TEE, besides the clinical setting, the histology-based likelihood the following characteristics are important: the tumor location, the morphological and functional characteristics [

8].

Clinical presentations and main findings in benign right heart tumors [

6] provided by imaging methods are presented in

Table 2. Echocardiography, CMR, cardiac CT and PET have complementary roles, requiring two or more of these imaging methods for an accurate diagnosis [

6].

Almost half of primary benign cardiac tumors are

myxomas. Cardiac myxomas can arise in 20% in the right atrium, and around 3–4% in the right and left ventricle [

6]. Up to 90% of myxomas are solitary and sporadic, with less than 10% being multiple and familial (Carney complex).

Papillary fibroelastoma is the second most common benign cardiac tumor: it seems to surpass myxomas, representing about 10% of all cardiac tumors and frequently diagnosed in men and between 40–80 years [

6]. It is usually located on cardiac valves (about 75% of all cardiac valvular tumors), and less often in the right heart. In the presence of symptoms (such as transient ischemic attack) or significant valvular regurgitation, surgical excision ensures an accurate diagnosis.

Cardiac

lipoma, one of the right heart tumors types, is a very rare primary tumor, without evidence of malignant transformation. Among benign cardiac tumors, lipomas seem to have an incidence between 2.9-8% [

4]; could be within the cardiac chamber (about 53%), encompassing all three layers of the cardiac wall (the endocardium, the myocardium in almost 11% of cases, or the pericardium in about 32% of cases) [

8]. Cardiac lipomas within the cardiac chamber are usually, smaller than, those within the pericardium. Multimodal noninvasive imaging is important in diagnosis (especially CMR), follow-up, and management of these tumors. In the literature, there are many case reports with right atrial lipomas and fewer with right ventricle lipomas [

8]; more than 90% of these patients underwent surgical resection [

4,

9]. However, this could fail if there is an infiltrative growth into the myocardium. The confirmation of cardiac lipomas by anatomopathological exam is mandatory. Lipomatous hyperplasia or hypertrophy of the myocardium interatrial septum, which is not considered true cardiac lipoma, could be an obstacle to the transseptal puncture in patients undergoing an ablation procedure (

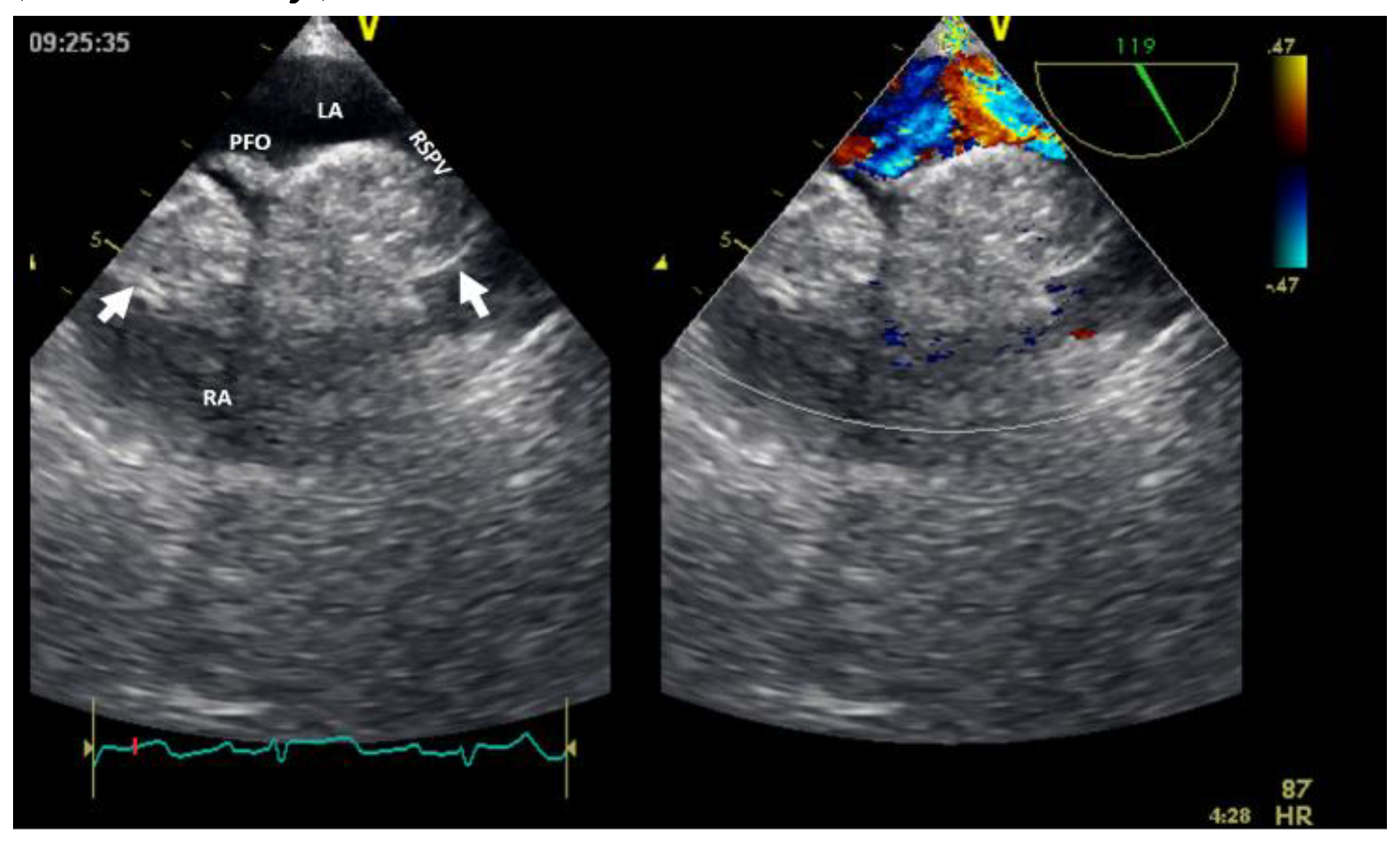

Figure 7). Cardiac magnetic resonance can facilitate a differential diagnosis with liposarcoma before resection (if necessary).

The main difference is liposarcoma, which exhibits the following characteristics on CMR: prominent areas of enhancement associated non-adipose lesions, thick or nodular septa, and prominent foci of high T2 signal [

20]. The size and margin are also discriminatory signs between lipoma and liposarcoma. The last is usually larger (> 10 cm), with nodular margins and lower fat content (< 75%) [

22]. Even with this imaging characteristic, without radiomics, well-differentiated liposarcomas might be challenging differentiate from mature cardiac lipomas.

Rhabdomyoma is more frequently diagnosed in infants and children, with an equal sex distribution. It can be intramyocardial or intracavitary, in the left or right heart [

6]. Can be frequently multiples, with intraluminal extensions in more than half of cases. In adults, suspicion of malignant tumor (rhabdomyosarcoma,

Video 4 - Supplementary Materials) requires the extension of imaging explorations to CMR+/-PET scan.

Fibroma is a tumor rarely diagnosed in adults, being the second most frequently occurring primary benign tumor in children, usually in ventricles. Appears as a non-capsulated mass located most commonly in the left ventricle free wall (in over half of cases), followed by right ventricle free wall (almost one third of cases) [

6]. Cardiac fibromas does not have a good prognosis.

Paraganglioma, a rare neuroendocrine tumor, is diagnosed typically in young female adults (between 20-60 years old), being rare localized in the heart [

23]. There are no cases described in the right heart. However, up to 10% of paraganglioma are malignant [

24].

Hemangioma is a vascular tumor more frequently found in women, being more common in the right atrium.

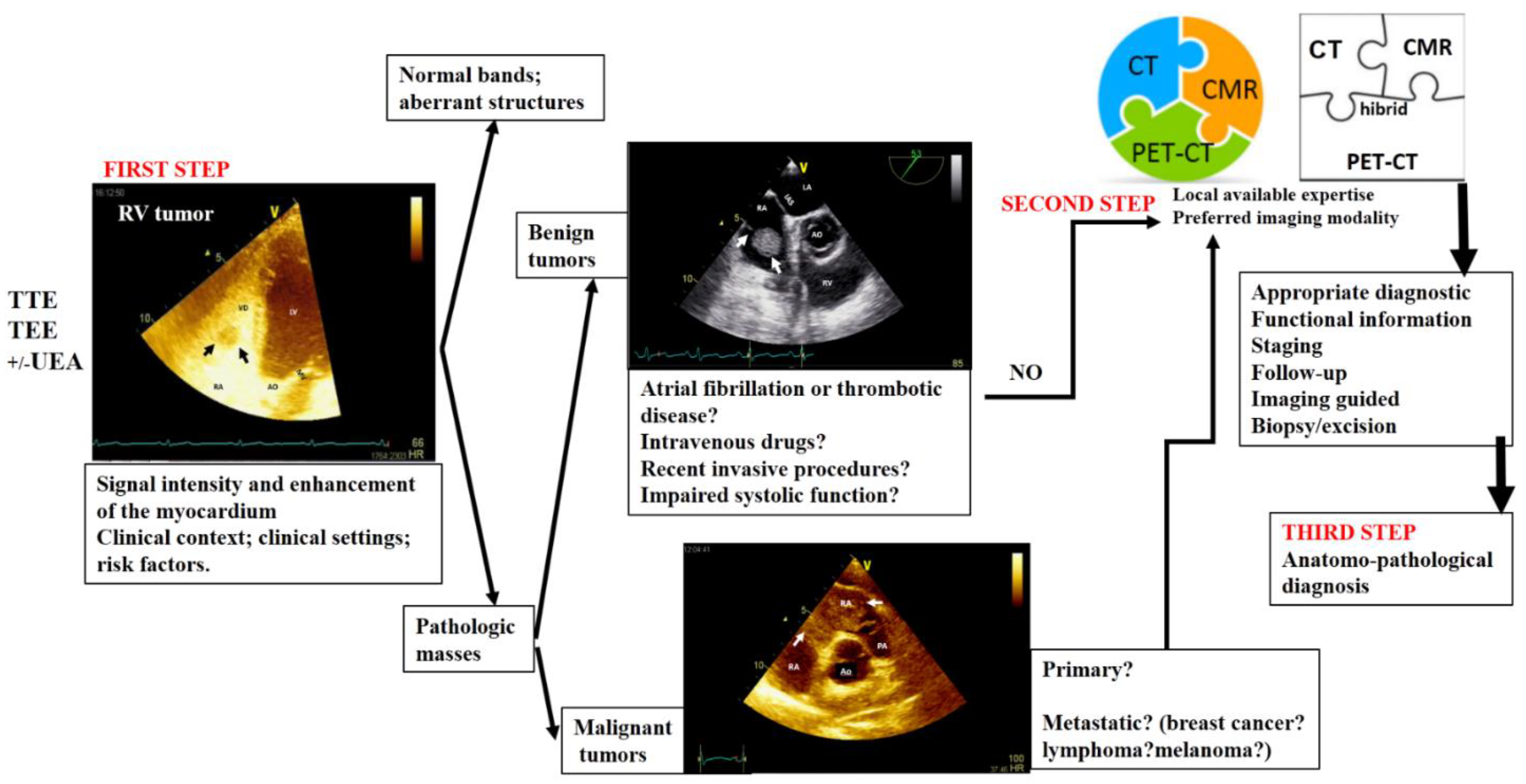

4. Proposed Algorithm for an Appropriate Multimodality Imaging Diagnosis in Right Heart Tumors

Nowadays, there is enough data about histological findings and outcomes that could allow performing some standardize recommendations in multimodality imaging for evaluation of the right heart tumors [

25]. In

Figure 8 it is presented an algorithm about the appropriate multimodality-imaging diagnosis for right heart tumors.

Artificial intelligence applications in cardiovascular imaging have proved significant roles in area such as detection, characterization, and monitoring of intracardiac masses and image interpretation [

26,

27]. In the future, artificial intelligence is likely to facilitate the development of an algorithm for a practical and appropriate imaging diagnosis of right heart masses. Moreover, there is the potential for artificial intelligence to integrate all medical data, including imaging, to predict prognosis [

26]. Nevertheless, practical approaches for multimodality cardiovascular imaging in cardio-oncology patients are gaining more and more traction [

28].

5. Conclusions

Right heart cardiac masses may be normal (aberrant variants) or pathologic structures. The last ones are usually suspected during a routine examination by transthoracic echocardiography or due to cardiac symptoms. Various imaging methods, following a multimodality-imaging algorithm that concludes with the excision or biopsy of the tumor, play roles in diagnosis, therapy and prognosis. The local expertise available in each center or the preferred imaging modality is crucial for an appropriate imaging diagnosis. In conclusion, in right heart tumors, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, as imaging methods often play a complementary role. Therefore, an integrated imaging approach is recommended.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Video S1: Transthoracic echocardiography (subcostal view) showing the presence of a thick right ventricular free wall (which on histological diagnosis was a myosarcom);Video S2: Contrast transthoracic echocardiography image with agitated saline serum (apical 4 chambers view) showed a spherical, mobile tumor in the right ventricle area, attached to the tricuspid valve (which on histological diagnosis was a cavernous hemangioma).Video S3: Bi-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography (short axis view at the level of great vessels) showing a mass in the right atrium, on the pacemaker leads. Video 4: Bi-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography (short axis view at the level of great vessels) showing a mass in right ventricle (rhabdomyosarcoma).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F., D.M.T., A.B., V.S., and D.E.I.; methodology, M.F., V.S., D.M.T., G.L.B., C.S.S.; software, D.M.T., C.S.S.; validation, V.S., M.F. and G.L.B.; formal analysis, A.B.; investigation, A.B., P.C.M, A.F.O.; resources, A.B.; data curation, P.C.M., A.F.O.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F., D.E.I., D.M.T.; writing—review and editing, V.S., A.B.; visualization, D.E.I., C.S.S., A.B.; supervision, M.F., D.M.T.; project administration, G.L.B., D.E.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All echocardiographic and video images belong to the authors of this article.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rajiah, P.; MacNamara, J.; Chaturvedi, A.; Ashwath, R.; Fulton, N.L.; Goerne, H. Bands in the Heart: Multimodality Imaging Review. Radiographics 2019, 39, 1238–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.K.; Rigsby, C.K.; Leipsic, J.; Bardo, D.; Abbara, S.; Ghoshhajra, B.; Lesser, J.R.; Raman, S.V.; Crean, A.M.; Nicol, E.D.; Siegel, M.J.; Hlavacek, A.; Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography; Society of Pediatric Radiology; North American Society of Cardiac Imaging. Computed Tomography Imaging in Patients with Congenital Heart Disease, Part 2: Technical Recommendations. An Expert Consensus Document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT): Endorsed by the Society of Pediatric Radiology (SPR) and the North American Society of Cardiac Imaging (NASCI). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2015, 9, 493–513. [Google Scholar]

- Secinaro, A.; Ait-Ali, L.; Curione, D.; Clemente, A.; Gaeta, A.; Giovagnoni, A.; Alaimo, A.; Esposito, A.; Tchana, B.; Sandrini, C.; Bennati, E.; Angeli, E.; Bianco, F.; Ferroni, F.; Pluchinotta, F.; Rizzo, F.; Secchi, F.; Spaziani, G.; Trocchio, G.; Peritore, G.; Puppini, G.; Inserra, M.C.; Galea, N.; Stagnaro, N.; Ciliberti, P.; Romeo, P.; Faletti, R.; Marcora, S.; Bucciarelli, V.; Lovato, L.; Festa, P. Recommendations for cardiovascular magnetic resonance and computed tomography in congenital heart disease: a consensus paper from the CMR/CCT working group of the Italian Society of Pediatric Cardiology (SICP) and the Italian College of Cardiac Radiology endorsed by the Italian Society of Medical and Interventional Radiology (SIRM) Part I. Radiol Med, 2022, 127, 788–802. [CrossRef]

- Tyebally, S.; Chen, D.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Mughrabi, A.; Hussain, Z.; Manisty, C.; Westwood, M.; Ghosh, A.K.; Guha, A. Cardiac Tumors: JACC Cardio Oncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACCC ardio Oncol 2020, 2, 293–311. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Tigadi, S.; Azrin, M. A.; Kim, A.S. Multimodality Imaging of a Right Atrial Cardiac Mass. Cureus 2019, 11, e4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wu, W.; Gao, L.; Ji, M.; Xie, M.; Li, Y. Multimodality Imaging of Benign Primary Cardiac Tumor. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, A.; Dădârlat-Pop, A.; Tomoaia, R.; Trifan, C.; Molnar, A.; Manole, S.; Achim, A.; Suceveanu, M. The Role of Multimodality Imaging in the Diagnosis and Follow-Up of Malignant Primary Cardiac Tumors: Myxofibrosarcoma-A Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 13, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, P.G.; Moreo, A.; Lestuzzi, C. Differential diagnosis of cardiac tumors: General consideration and echocardiographic approach. J Clin Ultrasound 2022, 50, 1177–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quah, K. H. K.; Foo, J. S.; Koh, C. H. Approach to Cardiac Tumors Using Multimodal Cardiac Imaging. Current problems in cardiology 2023, 48, 101731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Yu, Y. Multimodality imaging in cardiac myxofibrosarcoma. Eur. Hear. J. Case Rep 2022, 6, ytac223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzoni, L.; Bonapace, S.; Dugo, C.; Chiampan, A.; Anselmi, A.; Ghiselli, L.; Molon, G. Cardiac Tumors and Contrast Echocardiography. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 23, jeab289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.-H.; Chi, N.-H.; Wang, Y.-C.; Huang, C.-H. Metastatic breast cancer with right ventricular erosion. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg 2016, 49, 1006–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajdechi, M.; Onciul, S.; Costache, V.; Brici, S.; Gurghean, A. Right atrial lipoma: A case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med 2022, 24, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floria, M.; Guedes, A.; Buche, M.; Deperon, R.; Marchandise, B. A rare primary cardiac tumour: cavernous hemangioma of the tricuspid valve. European journal of echocardiography: the journal of the Working Group on Echocardiography of the European Society of Cardiology 2011, 12, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grecu, M.; Floria, M.; Tinică, G. Complication due to entrapment in the Chiari apparatus. Europace: European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology: journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology 2014, 16, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Angelo, E. C.; Paolisso, P.; Vitale, G.; Foà, A.; Bergamaschi, L.; Magnani, I.; Saturi, G.; Rinaldi, A.; Toniolo, S.; Renzulli, M.; Attinà, D.; Lovato, L.; Lima, G. M.; Bonfiglioli, R.; Fanti, S.; Leone, O.; Saponara, M.; Pantaleo, M. A.; Rucci, P.; Di Marco, L.; … Galiè, N. Diagnostic Accuracy of Cardiac Computed Tomography and 18-F Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography in Cardiac Tumors. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging 2020, 13, 2400–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijnens, J.; Bourgeois, T., L'Hoyes, W., Bogaert, J., Rega, F. The elephant in the atrium: an unexpected diagnosis resulting in obstructive cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2023, 25, e55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Ko, W. S.; Kim, S. J. Diagnostic test accuracies of F-18 FDG PET for characterisation of cardiac tumors compared to conventional imaging techniques: systematic review and meta-analysis. The British journal of radiology 2022, 95, 20210263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, S.; Wang, J., Zheng, C. From pathogenesis to treatment, a systemic review of cardiac lipoma. J Cardiothorac Surg 2021, 16, 1. [CrossRef]

- Benz, D. C.; Fuchs, T. A.; Tanner, F. C.; Eriksson, U.; Yakupoglu, H. Y. Multimodality imaging of a right ventricular mass. European Heart Journal. Cardiovascular Imaging 2019, 20, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polk, S.L.; Montilla-Soler, J.; Gage, K.L.; Parsee, A.; Jeong, D. Cardiac metastases in neuroendocrine tumors: 68: Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT with cardiac magnetic resonance correlation. Clin Nucl Med 2020, 45, e201–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, S.; Yuan, H.; Kong, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Zheng, C. The value of multimodality imaging in diagnosis and treatment of cardiac lipoma. BMC Med Imaging 2021, 21, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aidarous, S.; Khanji, M.Y. Advanced cavoatrial tumour thrombus as an unusual cause of right heart failure. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2023, 25, e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghayev, A.; Cheezum, M. K.; Steigner, M. L.; Mousavi, N.; Padera, R.; Barac, A.; Kwong, R. Y.; Di Carli, M. F.; Blankstein, R. Multimodality imaging to distinguish between benign and malignant cardiac tumors. Journal of nuclear cardiology: official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology 2022, 29, 1504–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Mattei, J. C.; Lu, Y. Multimodality Imaging in Cardiac Masses: To Standardize Recommendations, The Time Is Now! JACC. Cardiovascular imaging 2020, 13, 2412–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madan, N.; Lucas, J.; Akhter, N.; Collier, P.; Cheng, F.; Guha, A.; Zhang, L.; Sharma, A.; Hamid, A.; Ndiokho, I.; Wen, E.; Garster, N. C.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M.; Brown, S. A. Artificial intelligence and imaging: Opportunities in cardio-oncology. American heart journal plus: cardiology research and practice 2022, 15, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, D. S.; Noseworthy, P. A.; Akbilgic, O.; Herrmann, J.; Ruddy, K. J.; Hamid, A.; Maddula, R.; Singh, A.; Davis, R.; Gunturkun, F.; Jefferies, J. L.; Brown, S. A. Artificial intelligence opportunities in cardio-oncology: Overview with spotlight on electrocardiography. American heart journal plus: cardiology research and practice 2022, 15, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldassarre, L. A.; Ganatra, S.; Lopez-Mattei, J.; Yang, E. H.; Zaha, V. G.; Wong, T. C.; Ayoub, C.; DeCara, J. M.; Dent, S.; Deswal, A.; Ghosh, A. K.; Henry, M.; Khemka, A.; Leja, M.; Rudski, L.; Villarraga, H. R.; Liu, J. E.; Barac, A.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M.; ACC Cardio-Oncology and the ACC Imaging Councils. Advances in Multimodality Imaging in Cardio-Oncology: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2022, 80, 1560–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Bi-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography (apical 4 chambers view) with color Doppler showing external compression of the free right ventricular wall (arrow) in a patient with hepatomegaly due to a hepatic tumor, which explained hemodynamic instability (similar to a localized cardiac tamponade). AO, aorta; IAS, interatrial septum; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 1.

Bi-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography (apical 4 chambers view) with color Doppler showing external compression of the free right ventricular wall (arrow) in a patient with hepatomegaly due to a hepatic tumor, which explained hemodynamic instability (similar to a localized cardiac tamponade). AO, aorta; IAS, interatrial septum; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 2.

Bi-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography (short axis view at the level of the great vessels) showing a huge masse, inhomogenous, attached to the interatrial septum crossing the tricuspid valve (which on histology diagnosis was a myxoma). AO, aorta; IAS, interatrial septum; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 2.

Bi-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography (short axis view at the level of the great vessels) showing a huge masse, inhomogenous, attached to the interatrial septum crossing the tricuspid valve (which on histology diagnosis was a myxoma). AO, aorta; IAS, interatrial septum; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 3.

Bi-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography (apical 4 chamber view) showing Chiari network (arrow) in right atrium before and after (the last image) an electrophysiological study complicated by catheter entrapping in the Chiari apparatus. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 3.

Bi-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography (apical 4 chamber view) showing Chiari network (arrow) in right atrium before and after (the last image) an electrophysiological study complicated by catheter entrapping in the Chiari apparatus. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 4.

Bi-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography (modified parasternal view long axis) showing moderator band in the right ventricle. AO, aorta; IVS, interventricular septum; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 4.

Bi-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography (modified parasternal view long axis) showing moderator band in the right ventricle. AO, aorta; IVS, interventricular septum; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 5.

Bi-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography (short axis view at the level of great vessels) showing a mass on the port-a-cath in a patient with neoplasia and chemotherapy. It was an incidental finding. This mass disappeared after anticoagulation treatment because it was a thrombus. AO, aorta; IVS, interventricular septum; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 5.

Bi-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography (short axis view at the level of great vessels) showing a mass on the port-a-cath in a patient with neoplasia and chemotherapy. It was an incidental finding. This mass disappeared after anticoagulation treatment because it was a thrombus. AO, aorta; IVS, interventricular septum; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 6.

Bi-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography (short axis view at the level of great vessels) showing a mass in the right atrium, on the pacemaker leads. PM, pacemaker; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; TV, tricuspid valve.

Figure 6.

Bi-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography (short axis view at the level of great vessels) showing a mass in the right atrium, on the pacemaker leads. PM, pacemaker; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; TV, tricuspid valve.

Figure 7.

Bi-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography with color Doppler (high transesophageal view at 119°) showing two tumors at the level of interatrial septum with compression on right superior pulmonary vein (right image). LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; PFO, permeable foramen oval; RA, right atrium; RSPV, right superior pulmonary vein.

Figure 7.

Bi-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography with color Doppler (high transesophageal view at 119°) showing two tumors at the level of interatrial septum with compression on right superior pulmonary vein (right image). LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; PFO, permeable foramen oval; RA, right atrium; RSPV, right superior pulmonary vein.

Figure 8.

Multimodality integrated imaging algorithm diagnosis in right heart tumors. TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography; UEA, ultrasound enhancing agents; CT, computer tomography; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; PET-CT, positron emission tomography-computer tomography.

Figure 8.

Multimodality integrated imaging algorithm diagnosis in right heart tumors. TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography; UEA, ultrasound enhancing agents; CT, computer tomography; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; PET-CT, positron emission tomography-computer tomography.

Table 1.

The utility of the main imaging methods in right heart tumors.

Table 1.

The utility of the main imaging methods in right heart tumors.

IMAGING

MODALITY

|

Identify, localize, and characterize the tumor |

Make a differential diagnosis by distinguishing them from other cardiac pathologic conditions |

Evaluate the secondary consequences in the case of pathologic entities |

Classify in primary or secondary tumor |

| 2D/3D TTE/TEE (including UEA) |

++ |

++ |

++ |

+ |

| CT (including contrast CT) |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

++ |

| CMR |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

| PET |

++ |

++ |

+ |

++++ |

| Invasive angiography |

NA |

NA |

+ |

NA |

| Nuclear imaging |

NA |

NA |

NA |

+++ |

Table 2.

Clinical presentations and imaging findings of right heart cardiac tumors.

Table 2.

Clinical presentations and imaging findings of right heart cardiac tumors.

| TUMORS TYPE AND CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS |

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY |

|

COMPUTER-TOMOGRAPHY |

CARDIAC MAGNETIC RESONANCE |

POSITRON EMISSION TOMOGRAPHY |

| MIXOMA: This is frequently diagnosed in middle-aged patients (30–60 y). The typical triad of symptoms includes embolism, obstruction, and constitutional symptoms. |

It is a mobile, round, or oval in shape, heterogeneous echogenic mass attached to the endocardial surface, less commonly localized in the right atrium (especially in the left atrium, to the fossa ovalis). In contrast echocardiography appears as a partial or incomplete enhancement. |

|

Appears as heterogeneous, well-defined spherical or ovoid mass, a low-attenuation intracavitary mass with lobular contour and calcification (which are more common in the right atrium); as filling defects surrounded by enhancing intracardiac blood, hypo or isoattenuating relative to the myocardium. Contrast-enhanced CT will show a weak or absent enhancement. |

Usually is a smooth, well-defined, lobular, or oval mass; appears as a heterogeneous appearance or isointense on T1WI and heterogeneous appearance or hyperintense on T2WI (because of the high extracellular water content). Is relatively hyperintense compared with the myocardium, and hypointense relative to the blood pool.

On resting: slight heterogeneous enhancement.

On LGE images: patchy and more heterogeneous enhancement, 10–15 min after gadolinium contrast administration. |

May manifest as a mildly hypermetabolic hypodense area. |

| PAPILLARY FIBROELASTOMA: This can be an incidental finding or can be associated with a cerebral or sistemic embolic event. |

Small (usually <1.5 cm); round;

well-circumscribed; homogeneously textured appearance; a short pedicle; shimmering edges. Could be better visualized on 3D TEE, the echocardiography being the first step in the evaluation of embolic events.

|

|

It can be hard to see on moving valves. Appears as a focal low attenuation mass with irregular borders on valve surface. Can identify the anatomic location and attachment site, allowing simultaneous evaluation of the coronary arteries. |

It can be hard to see on moving valves. Appears as a round, small, homogeneous mass attached to valvular leaflets. Is an isointense signal intensity relative to myocardium on T1-weighted images or could appears as hypointense or as hyperintense signal intensity on T2-weighted images. On cine CMR images is a hypointense signal intensity. No delayed gadolinium enhancement on LGE, usually.

|

Usually not necessary. |

| LIPOMA: This is frequently an incidental finding. May be asymptomatic (even in large dimensions); fatigue; dyspnea on exertion; chest distress; palpitations; sudden death. |

Identify lipoma location and attachment, the shape, and the size.

Appear as hypoechogenic, homogenous echo intensity, and well-defined border.

|

|

Homogenous, encapsulated hypodense mass (between –45 HU and -100 HU).

|

Is essential in differential diagnosis with liposarcoma. It has the same signal intensity with subcutaneous fat; hyperintense (T1W and T2W); hypointense (in fat saturation sequences); T1/T2 value (ms): 255/65; Post gadolinium; no enhancement.

|

Usually not necessary, except in case of suspicion of malignity. |

| RHABDOMYOMA: This may be associated with symptoms of congestive heart failure, palpitations or syncope. These symptoms may gradually disappeared because of spontaneous regression of this tumor. |

Appears as multiple small, round, lobulated. |

|

Small; round; multiple homogenous hyperechoic mass of variable size, usually brighter than the surrounding myocardium; in contrast CT is hypodense. Allows to distinguish from fibroma by deformation imaging. |

On T1W1 rhabdomyoma appears isointense to slightly hyperintense (as on T2W1) compared with the myocardum. No delayed gadolinium enhancement on LGE.

|

Usually not recommended, except in case of suspicion of ma-lignity. |

FIBROMA: This may be associated with fatal arrhythmias, heart failure, and sudden death. Surgical treatment is

recommended regardless of symptoms.

|

Appears as a large intramural structure, well-delimited, noncontractile, solitary solid lesion within the myocardium, with central calcification. |

|

Described as intramural, homogenous structure, sharply marginated or infiltrative, with central calcification (a common feature of fibromas on CT) and soft-tissue attenuation, frequently without enhancement. |

On T1WI is an iso-intense tumor and on T2WI is a hypointense homogenous structure.

On LGE an intense delayed hyperenhancement is observed; without enhancement on resting. |

Usually not necessary, except in case of suspicion of malignity. |

| PARAGANGLIOMA: Is associated with symptoms like tachycardia, tremors, palpitations, flushing, hypertension, or hypotension because of excessive secretion of catecholamines. |

Appears as a granular oval heterogeneous structure, well-delimited, with a broad base. Sometimes adjacent structures like superior vena cava can be compressed. They are highly vascular structures.

|

|

Is a well-delimited and heterogeneous structure, with low attenuation. In constract CT is a heterogeneous marked enhancement. If the margins are poorly defined an invasion or extracardiac extension can be suspected. Can allows coronary angiography to assess the relationship with the tumor. |

Appears on T1WI as isointense or hypointense and on T2WI as hyerointense; with a heterogeneous and

peripheral rim enhancement |

Appear as positive with intense uptake of radiotracers. |

| HEMANGIOMA: is an incidental finding; in case of symptoms, the patient can present chest pain, arrhythmias, heart failure, dyspnea on exertion, syncope, stroke, pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, and even sudden death. |

Appears as a well-delimited structure, endocardial or intramural, with oscillations during the cardiac cycle; well vascularised (on color Doppler flow imaging presents blood flow signals); obviously enhancement. |

|

Is a well-defined structure, with a low density or equal density; associate heterogeneous intense

enhancement and “vascular blush” on coronary angiography. |

Appears on T1WI as a heterogeneous isointense or hypointense and on T2WI as a hyperintense, with heterogeneous enhancement. |

Usually not necessary, except in case of suspicion of malignity. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).