INTRODUCTION

Forests are of great importance for the socio-economic development of the rural and peri-urban areas in developing countries providing products for different uses at both household and industrial levels (Appiah, 2009). These products are grouped into timber and non-timber products (NTFPs). Timber products are highly valued worldwide while non-timber forest products (NTFPs) play a significant role in livelihood sustenance, especially in rural communities of Sub-Sahara Africa. NTFPs serve as a major source of fodder, protein, fruits, gums, resins, dyes, bamboo, rattans, mushrooms, medicinal plants etc. Globally, there is enough evidence that developing countries' populace rely on forest products for food, medicine and shelter (Dione et al., 2000). Rattan is one of the important NTFPs which contribute to the livelihood of the various actors along its value chain.

Rattan is a climbing palm of the family Palmae in the subfamily Calamoideae. It provides a valuable crop that can be grown and harvested sustainably. Its use in furniture production also means that effective rattan cultivation may provide a reliable alternative to timber exploitation. Rattan harvesting and processing provides an alternative to logging timber including secondary forest, fruit orchards, tree plantations or rubber estates. Also, they have been utilized for generations in binding, basketry and other domestic purposes, and it is the most important commercial non-timber forest product ranking next to timber and bamboo wood in Southeast Asia due to high economic value (Ogunwusi, 2012). Over the world, there are about 600 different rattan species arranged in 13 genera, and most of them are located in South-East Asian countries among which about 20 excellent species have been commercially used around the world (Nadine et al., 2017). NTFP trade such as rattan cane seems financially viable because the cost of nurturing the species to maturity (production) is usually not considered in the production cost but only collection and processing costs are always the focus (Pandey, 2016).

Rattan is found in considerable amounts in Nigeria forests which are numerous in the South-South region while it is limited in the northern part of Nigeria (Adewole and Onilude, 2011). Rattan is an effective tool to bridge the gap occasioned by wood raw material shortage in Nigeria; creating employment for the unemployed but able hands in the community as well as strengthening income generated from other sub-sectors in Nigeria (Copper, 2006). Rattan as a non-timber forest product has the potential to be developed as a commodity to meet both national and international demands (Dominic and Camille 2001; Supriadi et al., 2002). However, the share of rattan and cane products is negligible and barely above zero in the estimated contribution of agriculture and forestry to the gross domestic products in Nigeria (Ogunwusi, 2012). This is because most rattan operations are carried out without any form of mechanization and without following standard processing procedures for the products to meet export standards (Ogunwusi, 2012). This study investigates the contribution of the rattan cane business to the livelihood, income and poverty reduction of rattan processors in Ibadan.

The study focuses on the socio-economic significance of rattan-based activities in the Ibadan Metropolis, Nigeria. Rattan plays a vital role in the economy, particularly benefiting the rural population. However, there is a lack of comprehensive data on the employment and income generated by rattan businesses. The increasing demand for rattan has led to the depletion of wild stocks and local scarcity. The research aims to assess the contributions of rattan cane production to the livelihood of processors in the Ibadan Metropolis, with specific objectives including evaluating raw material availability, identifying factors affecting demand and supply, and assessing marketability. The study emphasizes the need for sustainable management of rattan species, highlights its historical utilization, and underscores its role in income generation and job creation. The information gathered can guide government policies and encourage the cultivation of rattan, addressing unemployment and promoting economic sustainability.

METHODOLOGY

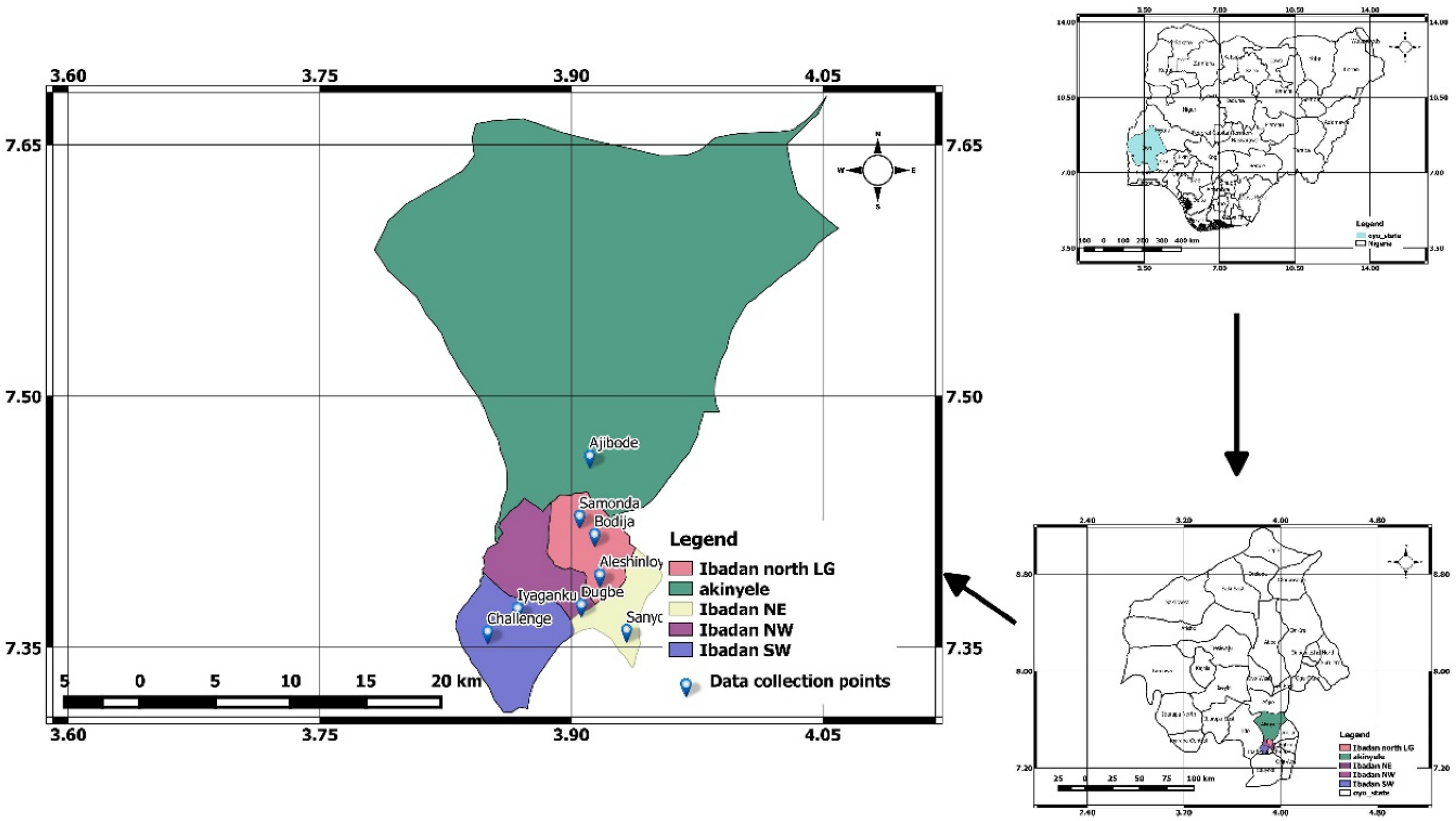

Ibadan is the capital and most populous city in Oyo State, Nigeria. Ibadan metropolis lies between latitudes 7

020’N and 7

040’N and longitudes 3

030’E and 4

010’E (

Figure 1). It is the third most populous metropolitan city in Nigeria with a population of over 1 million after Lagos and Kano (Ann, 2017). It is also the largest city by geographical area in Nigeria. Ibadan metropolis covers an area of 129.65km

2, it is located in south-western Nigeria, 128 kilometres inland northeast of Lagos and 530 kilometres southwest of Abuja, federal capital (

https://en.m.wikipedia.org. Accessed 13

th of November, 2019). With the strategic location on the railway line connecting Lagos to Kano, the city and its environment are home to several industries such as Agro-allied, food processing, health care, cosmetics and furniture making etc.

The city is a major centre for trade in cassava, timber, cocoa and palm oil. Ibadan is known for its abundance of kaolin, clay, several cattle ranches, dairy farms, and commercial abattoirs and the economic activities engaged in by the populace include; agriculture, trade, public service employment, factory work and tertiary population (

https://en.m.wikipedia.org. Accessed 13

th November, 2019).

Snowball sampling was employed to survey cane product processors in Ibadan Metropolis due to the difficulty in locating these hidden respondents. Fifty structured questionnaires, a mix of open and closed-ended questions, were administered through total enumeration sampling. Primary data was collected on raw material availability, factors affecting demand and supply, and marketability of cane products from rattan processors in the study area using structured questionnaires, field visits, and personal interviews. Secondary data was collected to obtain information on the factors affecting the demand and supply of rattan products in Nigeria then and what it is now from journals, articles, manuals and textbooks which were properly cited and referenced. Objectives one and two were achieved using descriptive statistics (percentages, and frequency). Objective three was achieved using Correlation and Gross Marketing Margin (GMM) analysis.

The survey included demographic information, production costs, income, and market conditions. Descriptive, inferential, and marketing margin analyses were conducted using SPSS. The relationship between production costs and income was determined through correlation analysis. Market margin analysis involves calculating the gross marketing margin as a percentage of the retail price. The model used was GMM (%) = (Selling Price - Purchase Price) / Retail Price * 100. This analysis provided insights into the marketability of cane products in Ibadans, Metropolis.

Correlation Analysis

To determine the relationship between the cost of production and the income of the respondents. Thus, the use of correlation indicates the strength of the relationship between these variables. The formula is given thus,

where:

rxy – the correlation coefficient of the linear relationship between the cost of production and income

xi – the values of the cost of production

x̅ - the mean value of the cost of production

yi - the values of the income

ӯ – the mean of the value of income

Market Margin Analysis

The procedure for analysis was based on (Achike, 2010).

A model for this could be represented thus:

GMM (#) = SP-PP

This is expressed as a percentage of the retail price:

GMM (%) = SP-PP/RP*100

Where:

GMM = Gross Marketing Margin

SP = Selling Price (#)

PP = Purchase Price (#)

RP = Retail Price (#)

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

Consumer decision-making process is strongly correlated with demographic variables such as age, gender, nationality, family size, family life, religion race, education, and social class (Ketler, 2003; Kim and Kim, 2004; Creusen, 2010). The age of the processors is an important factor that affects their level of involvement, overall productivity and overall coping ability. As seen in

Table 1, a majority (26%) of the respondents fall within age 33-38, the least was found in the category of >50. From the table, it can be deduced that many of the respondents are still in their youthful age (27-44) which portrays strength because they are endowed with strength to carry out tedious work. Age is related to experience i.e., the older one becomes the more experienced and exposed such individual (Prskawetz and Lindh (2006); Skirbekk, 2004). Risk bearing, more exposure to the line of business and greater experience are generally associated with higher earnings and productivity (Salthouse, 1991). Also, it can be viewed that the ageing workforce might lack experience in the relevant contemporary skills if job requirements change over time or if the people’s skills decline. This lays more emphasis on the strength, efficiency and ability to acquire more i.e., to be sceptical in adopting new things. Innovations in organizational structure, management practices and improved political and legal environments foster significant productivity gains.

From

Table 1, it can be said that 68% of the respondents are married, 26% are single (26%) and 6% are divorced. The fact that 68% of the respondents are married indicates that the rattan business provided income support for the families of the majority of those involved in the business. This confirms the relevance of rattan processing in the area of income and employment generation over the years.

Table 1 shows that the ratio of males to females is 39: 11, it can be deduced that in this trade there is a larger percentage of males than females which means that the level of involvement of females is low compared to males. It connotes that the trade is tedious and requires strength. From the table, it can also be extracted that males are more than females implying that the trade might be technically efficient (i.e., technical efficiency) which reflects skillfulness; labour input will be more as males are in higher proportion to females in the trade. With technical efficiency, it shows such trade aims for productivity and it is assumed that productivity is achieved.

The educational level is an important factor that affects the productivity of the trade.

Table 1 shows the educational level of the respondents; it reveals that the majority of the respondents (34%) fall on secondary education. It can be deduced that 22% of the respondents do not have any formal education, 24% of the respondents gained only primary school living certificates, 34% gained both primary school living certificates and O levels certificates and 20% had higher education. The lowest percentage (20%) was recorded in higher education and from their response to how their educational level has impacted their productivity. Many responses made the fact what they are doing now is not what they have studied in school but it has exposed them to learning. Respondents that attained tertiary education have an eye opener to new things that pertain to the trade, they are majorly the ones that incorporated other methods and techniques in manufacturing products. Though the equipment used is not favourable to exploring more in the way they can, they have generated new things that rattan can be used for, for instance; the making of flower vases with rattan has not long existed. Education enhances one’s ability to identify, locate and assimilate relevant information (Kulviwat

et al., 2004). Education has a powerful influence on consumer behaviour; the level of literacy in specific areas and regions may provide marketers with opportunities to seek products. Higher education gives entry to the profession, and social aspiration and consumption levels are raised (Chisnall, 1994). There are changes in product preferences and also higher incomes and more discriminating tastes (Stanton

et al., 1994).

Respondents with no formal education (22%) have informal education, many of them had their training in appliances, rattan trade and other vocational trades. Those who took up the rattan trade alone had more than 10 years of training before going into the business. The result of these have sharpened their experience on the trade and they might be perceived to know more about rattan as they are conversant with the raw material.

Education and age were used as proxy variables for managerial input. It is expected that increased experience and higher level of education would lead to a better assessment of the importance of good decision making including the efficient use of inputs. Increased levels of education in the workforce improve the quality of labour inputs and thereby increase output per hour worked. It is assumed that education with experience increases the processors' ability to seek and use information and production inputs (Njuki et al., 2006).

Table 1 shows that the respondent’s religions are Christianity, Islam and also traditional religion. The majority (66%) of the respondents are Christians, 22% are Muslims and 12% are traditionists.

The table tells us that 42% of the respondents in rattan trade in the Ibadan metropolis are Yoruba, 44% are Igbos and 4% are Hausas. It is inferred from the table that respondents are Igbo (44%) more in the trade than other tribes i.e., Igbos are found more in the trade than the Yoruba and Hausa. The implication of this is that, even though many of these Igbo traders do have a university education still what they have as an advantage over other tribes is their unique understanding of the mechanics of business fostered by a strong entrepreneurial culture. Also, in agreement with (Ola, 2016) Igbo traders are frugal in business which is avoidance of unnecessary expenditure and waste and they are persistent in their trade.

There is a reflection on the household size of the processors. Fifty-six per cent of the respondents have a household size of up to 5 people, 42% of the respondents have a household of about 6-10 people while 2% of the respondents are in a family of above 10 people. Though majority of the respondents’ households consist of 5 people (56%) which tells that the family is small-sized. It can be perceived that this set of people is well-informed and educated about the economy and its happenings. Respondents with households of 6-10 people are on the average. Respondents with a household size of above 10 people are perceived to be on the belief that with more children there will be more income which is not the case as the resultant effect is on the net income and also savings resulting to low investments. The outcome of this household size can be due to low levels of education, and religious, social and cultural beliefs.

From

Table 1, 52% of the respondents revealed that they have other means of livelihood such as shoe making, poultry rearing, driving, teaching, transportation, vendor, catering, other trade businesses etc. while 48% of them do not have any other means of livelihood aside rattan trade. It can be inferred that the business is a source of income for many people but the majority of the respondents that have other means of livelihood want more of profit gain. When asked why they are involved in other trades they responded that though a true rattan business is profitable there are considerations to other things they are involved in, considering what to be done in the family as many of them are family people of different household sizes, they were like staying on one business alone would not be able to achieve them all. Therefore, they need to get involved in other trades to generate income from different sources and collating them together will yield bigger profits.

Also, the time taking to finish jobs is longer and they do not fully utilize their income they would have spent so much before actualizing the money for the jobs done as it can be time-consuming due to the tools used. The trade-in Nigeria employs crude tools instead of machinery so that the jobs to be done on time. Many of them complained that when there seems to be importation of equipment to ease the work to avoid time waste, the government stopped the importation of bolo knives, the reason being that the cost of importation is high which has deeply affected efficiency.

Table 2.

Availability of Raw Materials for Processing of Cane Products in Ibadan Metropolis.

Table 2.

Availability of Raw Materials for Processing of Cane Products in Ibadan Metropolis.

| Is Rattan available? |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Yes |

21 |

42 |

| No |

29 |

58 |

Forty-two percent of the respondents stated that rattan is available while 58% of the respondents stated that rattan is not available.

From

Table 3, 28% of the respondents are of the fact that rattan availability is on the increase, 36% said that rattan availability is decreasing, 32% agreed that its availability remains constant while 4% said they do not know. Those respondents who do not know anything about the availability of rattan show that they are not conversant with the trade, many of them who do not know are assumed to be new in the trade as some are just starters. They are found in the rattan because they likely do not have anything to do that generates income for them and according to the survey, they are either introduced by friends or family to the trade. To those who agreed that rattan is on the increase, from what was discussed, it was discovered that they agreed to that because of the scarcity of rattan that occurred last two years and the year after. The majority of respondents (36%) stated that rattan availability decreased, and the supply of rattan has been on the decrease, therefore the sustainability of the rattan raw materials supplies; and by intention the rattan industry is in doubt. This tells us that rattan is a natural resource that can be exhausted but renewed. In agreement with what Oteng-Amoako and Obiri-Darko, (2000) stated, there is a decline in wild stocks and considerable local scarcity especially of rattan due to regular exploitation without conscious effort to regenerate rattan species.

Table 3.

Availability of Raw Materials for Processing of Cane Products over time.

Table 3.

Availability of Raw Materials for Processing of Cane Products over time.

| How has availability been in years? |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Increasing |

14 |

28 |

| Decreasing |

18 |

36 |

| Remain constant |

16 |

32 |

| I do not know |

2 |

4 |

Table 4.

Reasons for The Decrease in Rattan Availability.

Table 4.

Reasons for The Decrease in Rattan Availability.

| Reasons |

Frequency |

Percentage of Respondents that observed a decline in rattan availability |

| Deforestation |

9 |

18 |

| Excessive Demand |

8 |

16 |

| I do not know |

1 |

2 |

Reasons were given by respondents that stated that rattan availability is on the decrease and it is shown below:

Thirty-six percent of respondents who agreed that rattan is on the decrease gave their reason on a different basis. Eighteen per cent of these respondents stated that rattan availability is on the decrease due to the continuous harvesting of its crops. Deforestation is a major reason for the shortage of the supply of rattan, 16% of the respondents stated that the reason is the harvesting of immature rattan crops because of the excess market demand of rattan which leads to overexploitation of the raw materials and 2% are on the thought that it is undecided. The reasons stated drive down to the fact that rattan as a natural resource can be exhaustible if there is a measure put in place to ensure its continuous availability. There is a higher consumption of rattan material than the production. The supply of rattan has been on the decrease leaving the rattan industry in doubt. The reason is in agreement with the finding of Rahim and Idrus, (2018) that the utilization of rattan in Nigeria over time has resulted in the exploitation of this species. Also, the loss of forest cover due to the establishment of industries, residents and building structures are reasons for the inadequate supply of rattan in Nigeria (IFAD, 1991; Manokaran, 1992 and Oteng-Amoako and Obiri-Darko, 2000).

Table 5.

Availability of Labor.

Table 5.

Availability of Labor.

| Do you have people working for you |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Yes |

22 |

44 |

| No |

28 |

56 |

Forty-four percent of respondents have people working for them while fifty-six percent of respondents work alone. The majority of the respondents (56%) take up the work themselves and do not give out work. From what was discovered, many of them that work themselves not employing others take up their work from different people. They have their customers as well and they also work with other processors just to generate more income. From the field survey, it was discovered that those who employed workers do not have permanent workers for their employment is valid only in the case of urgency. They are only hired to assist in clearing workload and to ensure supply at the stated date i.e., urgency in supply. Furthermore, data collected reveals that 44% of respondents that employed labourers have other means of livelihood. They do not only run the rattan trade alone but they engage in other ventures that generate income.

Various incomes generated by respondents were collated. According to

Table 4.5, it can be deduced that the majority (64%) of the respondents have an income range between

#11,000 –

#35,000, 14% of the respondents make an income between and above

#36,000 while 10% of the respondents make an income of around

#10,000. Although not all respondents have data taken down for their income as they see it as confidential information from the profit gotten it indicates that there is income generated from the trade. Respondents with above

#36,000 income per month have different businesses they are into aside rattan trade as stated in

Table 6 which enables them to generate such income. The majority with an income between

#11,000 –

#35,000 are more into cane furniture and they let out jobs more to labourers while those with income of

#10,000 or less are majorly labourers (those that do not have a workshop but work in different places as laborers).

It can be deduced that income that can be said to be sufficient to maintain and sustain the respondents cannot be sourced only from rattan trade. Following

Table 1, the majority of the respondents are of a household size of up to 5 people; income from rattan trade about their household size will not sustain household needs.

Table 7.

Price variation.

Table 7.

Price variation.

| Is there seasonal price variation |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Yes |

34 |

68 |

| No |

16 |

32 |

Price is an important factor that affects the supply and demand of rattan. From 15, the majority (68%) of the respondents stated that prices vary while 32% of the respondents stated that there are no changes in the prices of rattan. Sixty-eight percent of the respondents further explained from

Table 16 that variations in prices are due to the seasons in Nigeria, the seasons which are rainy and dry. From

Table 8, 62% of the respondents stated that in the rainy season, the price of rattan is the lowest, and 6% of the respondents stated that the price of rattan is the highest in the dry season. The abundance of this raw material brings down the price of rattan. Rattan in abundance will increase the production of products making consumers benefit from it as well. The purchase of products is cheaper compared to when the price of raw materials is high. The case is different when in the dry season, scarcity of rattan increases the price of the commodities.

Irregularities of price compel costs for both producers as well as consumers in agreement with Parmod and Anil, (2006). Respondents identified factors that are possibly responsible for price variation. They mentioned that the rattan trade is seasonal; there is more demand for cane products during festive periods and also ceremonial events. Price variation depends on the availability of rattan by suppliers. As explained earlier, they get to supply more in the rainy season and do not supply frequently during dry seasons.

From the survey, it was discovered that the tools used by the processors are crude tools such as knives, saws, hammers, gas cylinders, pinches, and tape rules which are reflected in production time. It implies that rattan processing in Ibadan is still at the craft level (i.e., the use of crude tools) which has an impact on the production level of the trade. It allows production time to be higher which in turn affects productivity and the market of the products. A low degree of mechanization reflects in the output of the trade leading to low average investment of workers. It gives room to no competition and doesn’t allow creativity (i.e., the use of rattan in the production of different designs and shapes) (Aguilar and Miralao, 1985; UNIDO, 1983; IFAD, 1991; ESCAP, 1991).

Table 9 shows that the majority (56%) of the respondents stated that they pay tax while 44% of the respondents do not pay tax. From the survey, it can be deduced that those who pay tax do not pay directly but it is removed from the money contributed every month from group contribution that they are involved in. The respondents (44%) stated that they do not pay tax; they do not do group savings. They do not see any reason to pay tax when they have never received any support from the government; lack credit availability with less provision of sophisticated machinery, and no quality control measures to enable processors to produce high-quality products that can fetch higher prices.

Table 10.

Support from government.

Table 10.

Support from government.

| Do you receive support from the government? |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Yes |

- |

- |

| No |

50 |

100 |

All the respondents stated that the government has never been supportive. Despite their complaint to researchers and extension officers, the situation remains unchanged and their efforts prove abortive.

Table 11.

Credit Facilities.

Table 11.

Credit Facilities.

| How do you obtain capital |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Bank loan |

13 |

26 |

| Family loan |

5 |

10 |

| Corporative loan |

5 |

10 |

| Personal savings |

27 |

54 |

In terms of credit facilities,

Table 4.6.4.3 shows various facilities to obtain loans for the capital of the business. The majority of the respondents (54%) stated that capital to start up the trade is obtained from personal savings, 26% said that capital for the business was obtained from the bank while 10% of the respondents obtained capital from family, friends and relatives. the remaining 10% of the respondents obtained loans from corporative. Though deducing from the responses by respondents, the capital to start of the business is affordable and can be acquired from returns of other jobs. Respondents (26%) that obtain loans from banks are mostly into other trades aside from rattan trade and capital is going into different businesses. No financial support from the government. Also, Credit facilities that should be opened for industries and to help small-scale businesses are not accessible.

Table 12 shows the cost incurred in the manufacture of cane products, it also shows the major products made out of rattan in Ibadan Metropolis. Products are manufactured on a large scale, (i.e., large-scale production). They get jobs from Supermart, ShopRite, retailers and event planners and their production is mass. Production cost in this study was determined for those products that are commonly produced in the industry. These include stools, chairs, tables, basket flower vases, hats etc. The production time to process each unit of the items (stool, chair, table basket, hat and flower vase) varies and it determines the extent to which rattan products are produced. The average cost of raw materials in localities visited is #1500 per bundle of about 13 sticks (for cane). The average cost of a stick of cane is #115 though purchase is mostly per bundle. The length of each stick is about 12 feet (3.66 meters). In determining the cost of raw materials used for cane end products, only those products that are commonly produced were considered (

Table 12).

From

Table 13, it could be seen that with an investment of

# 10,181.67 in the production of a set of stools (3 stools), a profit of #14,499.44 was made. For a set of chairs, a profit of #1270.83 was made. Arranging the different end products in terms of profitability, a set of chairs tops the list as shown below. It is also observed that cane furniture is making more return in this trade than other cane products made with rattan canes. The income derived cannot justify the labor incurred and the time spent in production as spending is more than their profit. An increase in production time holds current assets, frees fixed assets slows down reproduction and decreases the output.

Table 14 shows that there is a significant difference between the cost of production and the income of the respondents.

Table 15 shows the percentage of the market for the common products sales in Ibadan Metropolis. The table represents the estimated figure of marketing margins which is derived from the profits rattan processors acquired from the sales of these products. Processors in the Ibadan metropolis major in the same products and there is no difference in their production of cane products. From

Table 15, it can be seen that the market margin for stool is 15.15%, for chairs is 32.22%, for tables is 6.59%, for baskets is 19.55%, for hats is 5.14%, flower vases is 5.96%. Also,

Table 15 shows the profit margin for stool as 18.18%, for chair as 145.00%, for table as 6.92%, for basket as 12.71, for hat as 30.83, for flower vase as 59.58%. The profit and returns from each product show that furniture such as chairs is higher (145.00%) than other rattan products considered in this study as a result of the cost incurred in processing as well as production time and that the market for baskets, stool and chairs in Ibadan metropolis is high compared to hats and flower vase.

Table 15.

Marketing Margin.

Table 15.

Marketing Margin.

| S/N |

Product |

Cost Price (#) |

Selling Price (#) |

Profit (#) |

| 1 |

Stool |

10,181.67 |

12,000 |

1818.33 |

| 2 |

Chair |

30,500.56 |

45,000 |

14,499.44 |

| 3 |

Table |

9,808.33 |

10,500 |

691.67 |

| 4 |

Basket |

5,229.17 |

6,500 |

1270.83 |

| 5 |

Hat |

5,691.67 |

6,000 |

308.33 |

| 6 |

Flower Vase |

9404.17 |

10,000 |

595.83 |

Table 16.

| Price in % |

|

| Market products |

Market Margin (%) |

Profit Margin (%) |

| Stool |

15.15 |

18.18 |

| Chair |

32.22 |

145.00 |

| Table |

6.59 |

6.92 |

| Basket |

19.55 |

12.71 |

| Hat |

5.14 |

30.83 |

| Flower Vase |

5.96 |

59.58 |

| Average |

14.10 |

45.54 |

The market margin records highest in basket products, the reason is because of the high demand of consumers for different ceremonial functions. Ceremonies such as weddings, naming as well as festive periods for the presentation of gifts to people and also as souvenirs. Also, from the table, it can be seen that higher profit is recorded from products such as chairs and tables which tells of the durability of rattan products. Despite the high cost of purchase, consumers purchase more of them because of the aesthetic value it provides with the use of wood as well as its durability. The prices of chairs and tables are inflated by the cost of producing these products.

This implies that there is less competition in the market for rattan trade. This agrees with Minot and Golleti (2001), who observed that competition pressure reduces profits and perhaps costs, resulting in low marketing margins. Processing of NTFPS is done for various reasons proper utilization, an extension of shelf life, and value addition are few out of many objectives. Processing provides the physical characteristics of the goods while marketing entails the packaging, branding, finishing, price promotion, location, positioning and people. The value of a product economically projects into marketing which forms a crucial part of it i.e., income generated and revenue derived from the sale of products is designed from effective marketing (ITTO, 2011). Processing can be achieved through simple cleaning of harvested materials, providing proper storage conditions, packaging, grading and labelling of products. There are constraints to effective processing that were identified, they include scarcity of raw materials, especially during the dry season; scarcity also as a result of overexploitation and steady loss of forest habitat to buildings and agriculture, unsustainable harvesting of rattan. This resulted in declining exports and the closure of several operations alongside competition. This is in line with the conclusion of Olubanjo, (2002) that sound and sustainable management and exploitation of rattan stocks has not enjoyed desirable consideration in government circles or among local authorities and institutions. Rattan processors lack credits from the government rather taxes are imposed on this business which restrain the expansion of their business. The low degree of mechanization and labour intensity of the rattan are constraints which have a great impact on the marketing of the trade and also their income. Rattan processing is still at the craft level in Nigeria and there is a high intensity of labour work due to i.e. scraping, drying, splitting, sizing, bending, cording and chemical treatments as good designs and modern technologies are essential to meet standards for export. This is in agreement with the statement of Achike, (2010). Also, lack of credit availability and technical assistance limit the adoption of modern and efficient technology. This is also in support of what Abel (2018) stated on the challenges facing rattan craft men in Africa. He mentioned that the relatively high cost of acquiring high-valued rattan canes continuously all year round, and the tedium and time involved in manual peeling and weaving of cane products are crucial challenges of rattan processors. These challenges have limited the expansion of the rattan business.