2.2. Integration of XR in D. Nomikos Museum

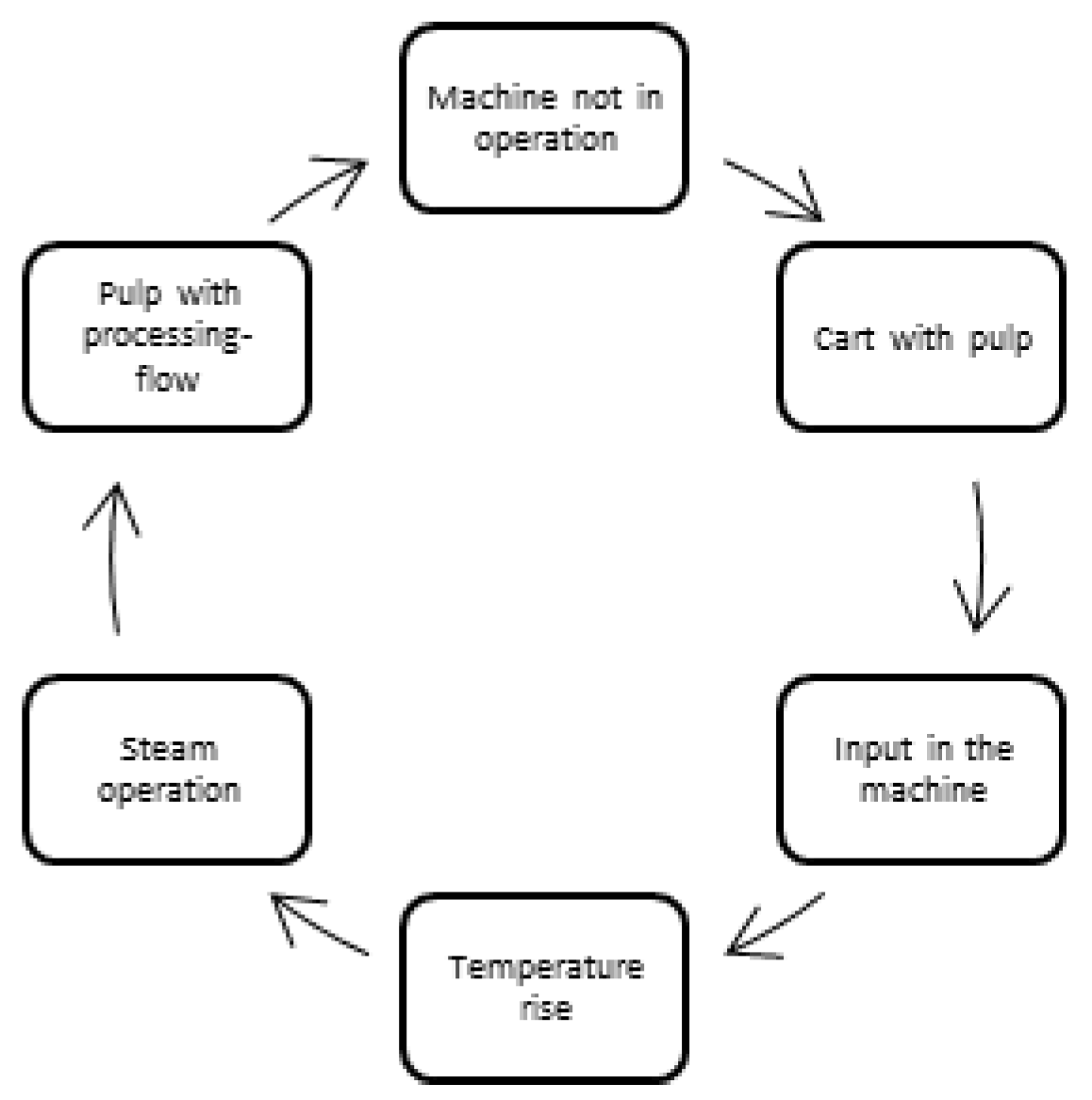

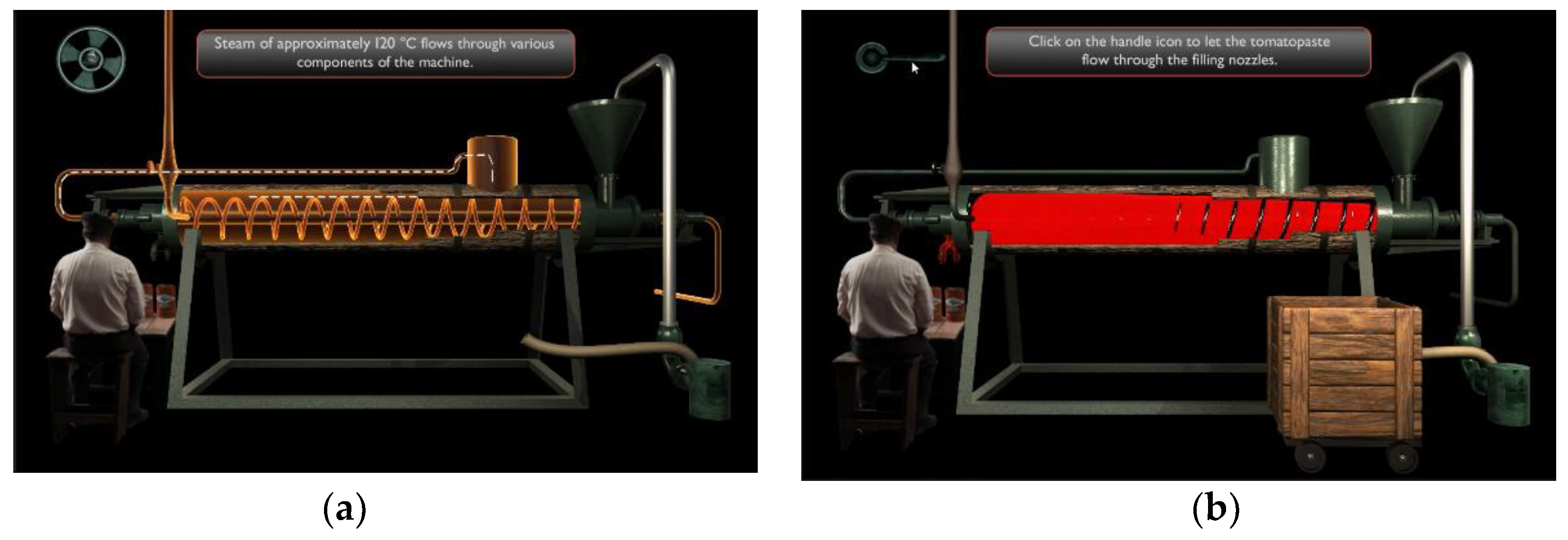

The thematic context in which the technologies employed in the Tomato Industrial Museum exhibition can be summarized as follows: the visitor learns about the processing machines from 1890, old tools, and through audiovisual material with videotaped stories of people who used to work in the factory, learns about the production procedure. More specifically, the use of technologies aims at (a) rendering the internal parts and function of the machine visible (i.e., with the use of animated cross sections); (b) show the "transformations" of the product through the concatenation of industrial processes and sequential operation of machines, and highlight the qualities of the end product; (c) foreground the workers’ role in the procedures and also the human perspective with regard to the experience of working and cooperating with others in the specific factory.

The museological underpinnings of the exhibition scenario and design had to face two serious challenges: firstly, how to combine static machinery along with screens/viewing devices in a way that new technologies will enhance the exhibits rather than distract from them, and secondly, how to engage visitors with an old industrial process and make them connect to the life in the factory as it unfolded in a bygone era. The first problem was addressed by installing rather discreet devices and placing them in a way that encourages a parallel viewing of screens and exhibits audiovisual resources referred to each time. The second issue of how to engage people who may not feel compelled to connect to a 19th-century line of production or the respective workers’ experience has been addressed through a combination of foregrounding the human element, e.g., through first-person narratives, with the animated representation of machines internal function, that allow for otherwise strange machines to become more understandable in terms of their role and thus generate more interest. The main issue in this respect and concerning the specific museum is the fact that, quite literally, the exhibits are almost self-referential, i.e., the machinery comprising the line of production, as opposed to a cultural artefact of artwork, do not seem to generate tangible allusions, connections, interpretations, or personal effects easily. In a way, exhibits only 'talk' about themselves and their position or role in the specific production procedure as purely practical items. One question that arises at this point is how to turn this practicality and orientation toward a result into an element that may be exploited to foster interest in the exhibits with the help of new technologies. A quick answer is to engage viewers and users of XR applications in tasks or gamified procedures, creating a challenge for them to undertake practical tasks as virtual handlers of such machinery.

Furthermore, new technologies allow for the inclusion of a considerable amount of information that may be interactively accessed but could not be satisfactorily included by conventional means. Such technologies, thus next to an exhibit, give an active role to the visitor, who chooses the level of information they wish to gain. Moreover, the appeal of user-friendly and exciting in their own right, interactive visuals can complement an otherwise mundane series of ancient machines for some visitors and foster the museum experience through a contrapuntal presentation of old next to new technologies that synergize to generate a meaningful engagement with the past. The inclusion of screen-based means is also foreseen as a measure to address the sensibilities of a generation that relies heavily on devices such as smartphones to gather information, gain insights and connect to a heritage site.

Designing visitors’ path with ICT applications was related to the approaches adopted to complement and enhance the visitors' experience and engagement with three key production phases and the corresponding machinery enlivened in differing ways with the presence of digital humans, thereby adding an element of empathy through narrations and visual representations of workers in original attire of the decades in which the factory functioned. Correlating the goals of the audio tour with XR technologies is based on a conscious effort to put these two ways of enhancing visitors' museum experience in synergy; thus, the choices made regarding digital applications were made bearing in mind that these two different but symbiotically related strands of communicating information and engaging the viewers, should mutually foster each other. The goals of applying the script are to clarify the primary stages of the production chain, i.e., the process of washing/sorting the tomato, the dehydration/condensation of the pulp, and finally, its pasteurization and packaging.

2.3. Design of evaluation methodology

The evaluation process was based on questionnaires filled out by visitors who were asked to assess their experience in relation to the effect that new technologies embedded into the exhibition had on their museum experience. After a review of existing questionnaires, we deemed more apposite to use one that is not as generic as the System Usability Scale/SUS [

7] (not to be confused with the Slater-Usoh-Steed Questionnaire whose acronym is also SUS and is presented below that was developed by Usoh et al. [

8], and that could capture more qualitative aspects of the users’ experience. At the same time, we opted for a method that is not time consuming or taxing to avoid unnecessary fatigue that may ensue for the visitors.

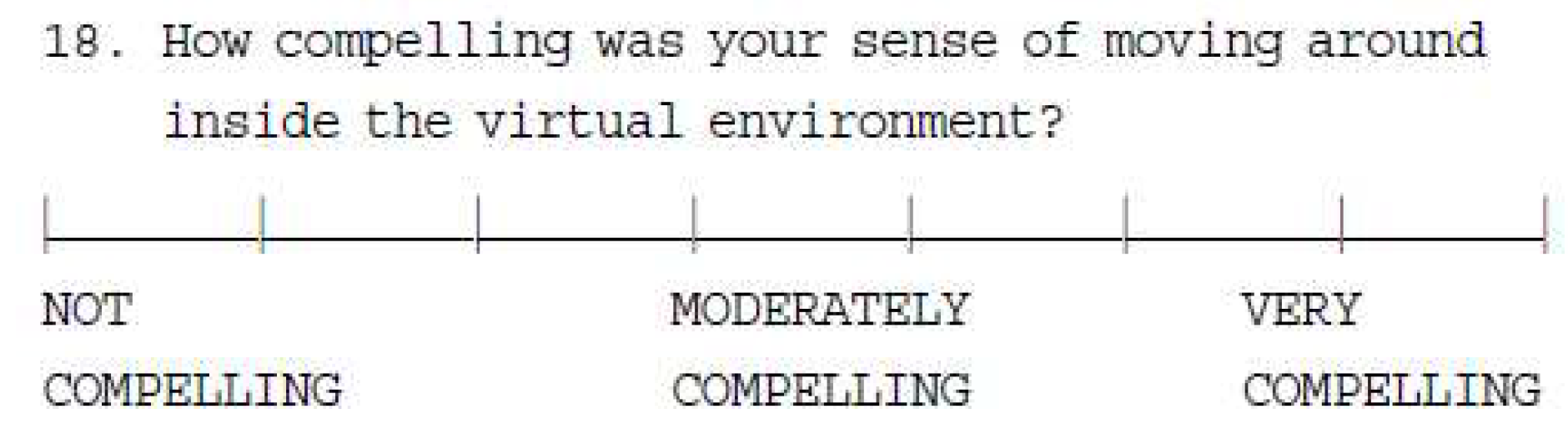

More specifically, during the design phase of the evaluation process that is more suitable for the specific exhibition and the technologies embedded in it, we surveyed assessment methods in the fields of XR-based experiences with emphasis on the culture and heritage domain as well as tools that mostly relate to digital applications that are either commercial products or can be described as more generic/general purpose as the SUS mentioned above. We surveyed XR specific UX questionnaires that were exceptionally interesting as such, however they gravitated towards immersive or fully immersive experiences, hence they were deemed incongruent with the scope of the specific evaluation. Such methods include the Presence Questionnaire developed by Witmer & Singer (1998) that uses a 7 steps Likert Scale as the

Figure 1 below illustrates.

Nevertheless, the sense of Presence is a key element for Virtual Environments (VE), which Lee [

9] ‘tentatively’ defines as “a psychological state in which the virtuality of experience is unnoticed” or according to Witmer & Singer [

10] is the subjective experience of being in one place or environment, even when one is physically situated in another, does not fully apply in the Tomato Industrial Museum exhibition design as it stands. Therefore, as a methodological approach is not commensurate with the type of mainly augmented reality and audio tour-based experience that may benefit from XR but do so by offering a coexistence of digital tools with the actual exhibits in their physical form and in an actual brick-and-mortar museum space. We nevertheless see fit to include a brief outline of the existing methodologies in the field and delineate the reasoning behind finally choosing the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) developed by Laugwitz et al. [

11]. that is presented in detail in the following section, over other more specified (or, conversely, generic models). Schwind et al. [

12] identified that Witmer & Singer [

10] are by far the most cited authors that present a questionnaire on Presence in XR environments. Likewise, Grassini and Laumann [

13] who provide a thorough Systematic Review on published research measuring Presence, surveyed 20 papers and, according to their findings, Witmer and Singer Presence Questionnaires (PQ) are used more frequently than any other measuring approach.

Grassini and Laumann [

13] offer a comprehensive outline of the issues and trends related to researchers’ efforts to measure presence in XR environments: The PQ questionnaire emphasizes the “involvement” and “immersion” characteristics of the simulated environment, while the Slater-Usoh-Steed Questionnaire (SUS) and the Igroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ) [

14] are focused on the sense of “being there” (i.e., the sense that the experienced VE may be part of the reality). The MEC-SPQ questionnaire [

15] analyzes what is called “spatial presence”. Moreover, although MPS (Multimodal Presence Scale) [

16] offers some very interesting aspects, it is hinged on spatial attributes and parameters of the experience in VE, as well as on one’s own sense of body/avatar as ‘real’ in a VE. Furthermore, Social presence is vital in MPS, but does so following Lee’s (2004) conceptualization of presence in VEs.

Moreover, a more pertinent evaluation method is described in a recent publication by Hammady et al. [

17] that focuses on an MR museum experience, while at the same time provides a comprehensive survey of related methods. This publication introduces a useful theoretical scheme and related methodological approach for evaluating a museum related XR experience.

Although the Role of the Guide (virtual human) is central in this diagrammatic scheme, even if deducted, the theoretical scheme remains relevant and methodologically valid for the present research in D. Nomikos Museum, as the remaining key elements still interrelate and underpin users’ Intention to Use. The main strengths of this methodological approach that it may well inform the present evaluation process, as it can serve as a framework that may help in interpreting (or, to an extent, coding) responses in interviewees’ answers. Adopting the structure of (tens of questions presented in [

17]) in questionnaires would result in adding questions that would overlap with those of the UEQ and protract the questioning procedures disproportionally in comparison with expected benefits. However, it was deemed beneficial to adapt these key interest areas as guiding or reference points for better making sense of qualitative data that emerge from discussions. More specifically, the terms presented by the authors [

17] are the following: Enjoyment, Immersion, Multimedia and UI, Storytelling (where applicable), Usefulness, Ease of use, Interaction, overall satisfaction phrases, and last but not least, the willingness of future use.

In a few words, the framework that is referred to at this point provides a basis to foster further the procedure of analyzing the outcomes of interviews/focus groups discussions and, in parallel conditions, the prompting questions such as ‘what did you like the most’ in a way that will encourage responses that address/include the abovementioned topics/areas (that also serve a codes). The theoretical scheme also will inform the structuring of these areas within the process of reaching conclusions and inferring meaningful suggestions as the intention of future use, for example, is shown to be the combined outcome of the other factors named above. In a nutshell, it is based on the UEQ approach and, moreover, draws on the framework developed by Hammady et al. [

17] with regard to the open-ended questions in focus groups, thereby facilitating analysis, gaining pertinent insights, and reaching more informed conclusions.

Other XR-related publications/research were also investigated, e.g., the case of Gonz et al., [

18] that use an adapted version of the Improved Museum Experience Scale (IMES), developed by Othman [

19]. This Questionnaire focuses on investigating four areas:

Engagement with the exhibit (in the case of [

18], a painting)

Knowledge/ Learning gained from understanding and information discoveries

Meaningful Experience from the interaction with the painting

Emotional Connection with the context and content of the painting

This helpful approach, although seemingly pertinent, was deemed to be both hinged on the affective and meaning-making potential of an artwork (main exhibit) and, therefore, incommensurate with the scope of an industrial heritage exhibition and contradictory to the UEQ that requires strict adherence to the exact set of questions in order to yield analyzable results.

Last but not least, another widely cited and used approach in XR-related experiences is that of the Slater-Usoh-Steed Questionnaire (SUS) developed by Usoh et al. [

20]. This approach, according to [

20] was developed over several studies by Slater and colleagues and most recently used in Slater et al. [

21] and Usoh et al. [

20]. This questionnaire is based on several questions that are all variations on one of three themes: the sense of being in the VE, the extent to which the VE becomes the dominant reality, and the extent to which the VE is remembered as a ‘place’. As this questionnaire focuses on the sense of space, it is deemed less helpful for our study. Furthermore, usability was measured using the System Usability Scale (SUS) [

22], which is an accredited and widely used questionnaire for measuring system usability. This quite generic yet useful evaluation tool can help assess user acceptance of the system.

What transpires at this point is that while there is a profusion of quantitative evaluation methods specifically developed to capture aspects of the user experience in an immersive VE, there is a caveat about questionnaires that are designed to assess the complex interrelation of augmented reality apps within physical galleries and used in tandem with actual artefacts/exhibitions.

After due consideration, the core method employed in the evaluation process is a thorough, yet relatively succinct questionnaire that measures user experience (User Experience or UX) in relation to interactive digital interfaces; namely, the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) developed by Laugwitz et al. [

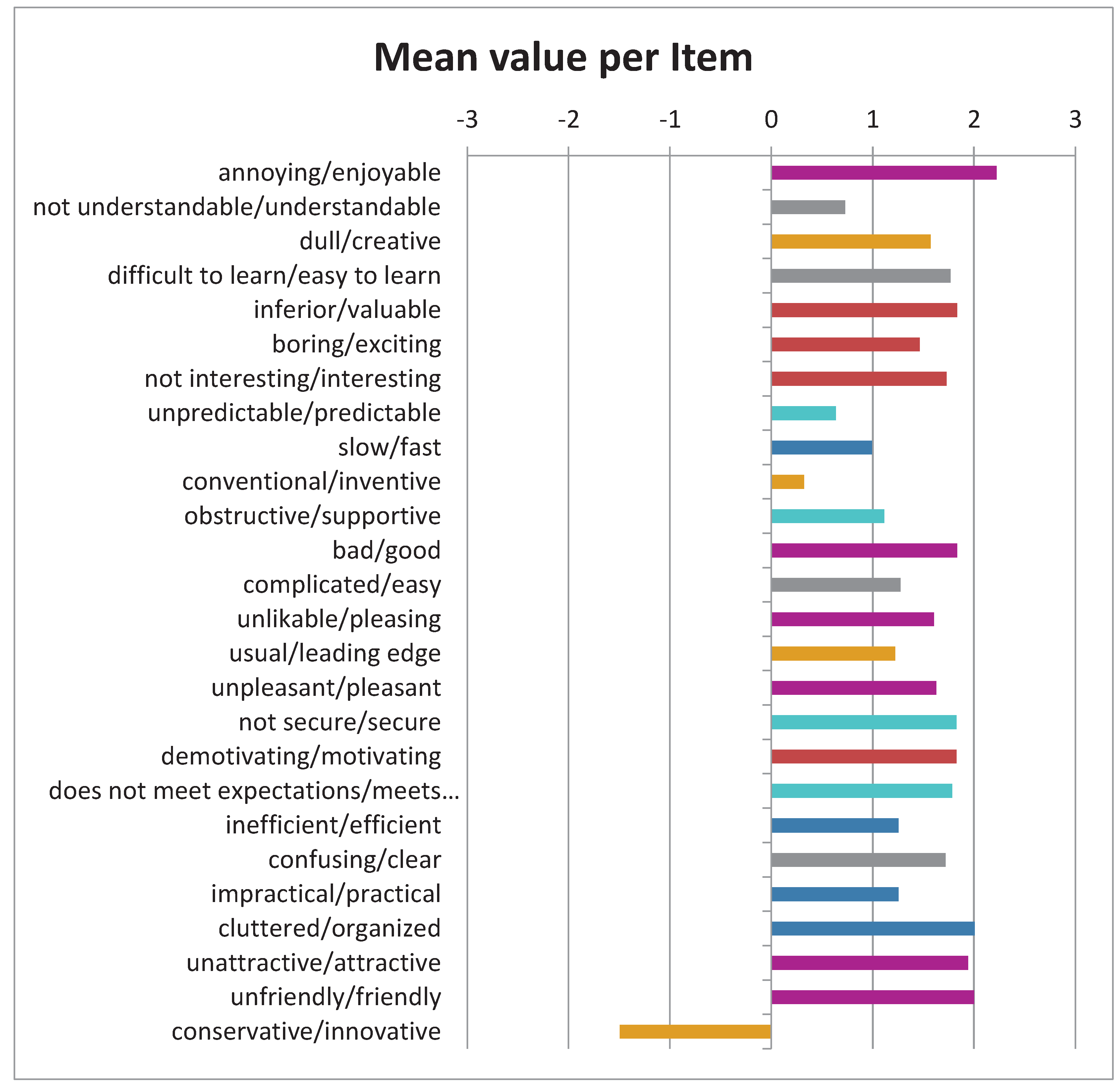

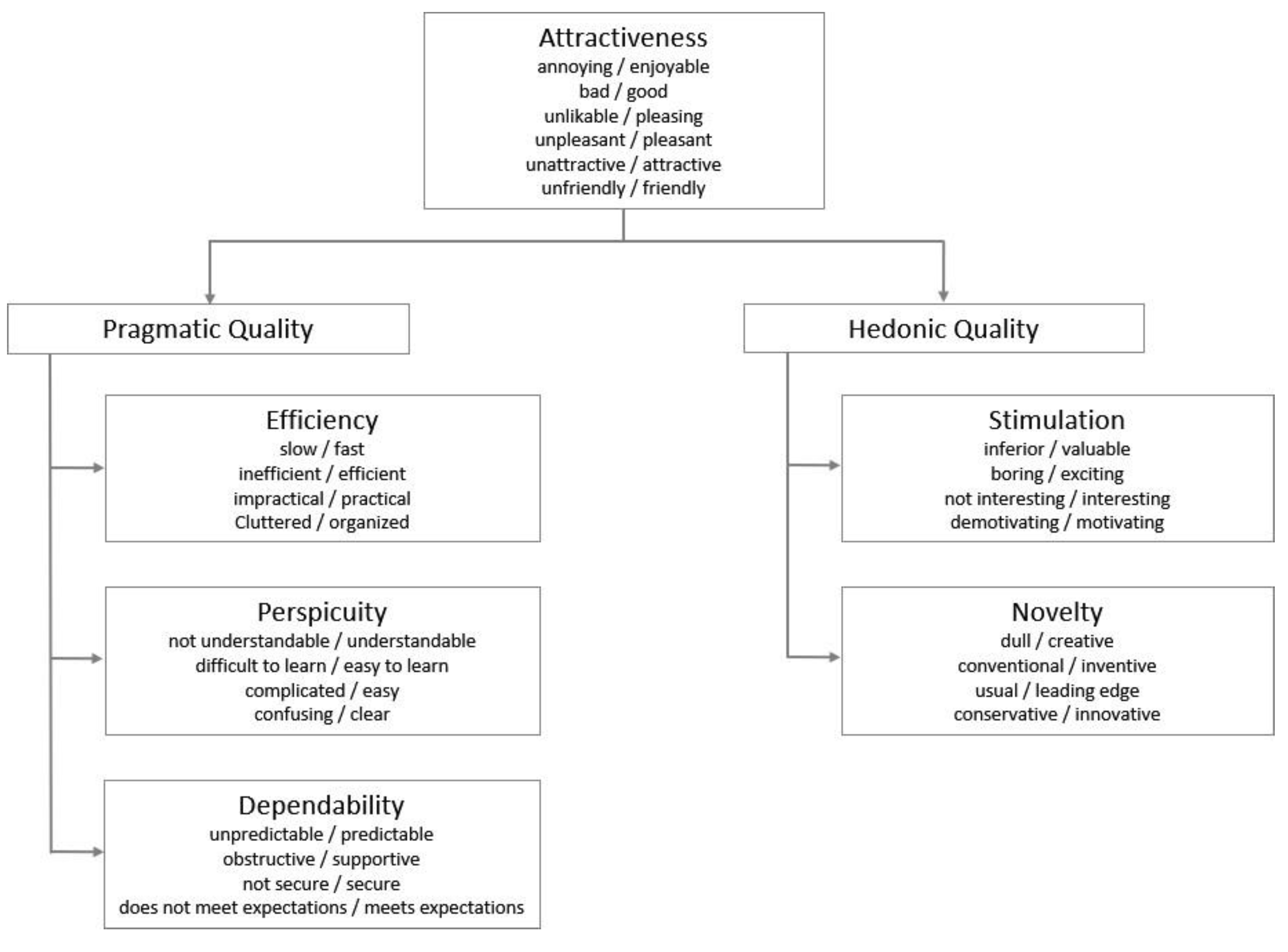

11]. Apart from the fact that as a method aims to capture both objective and subjective aspects of user experience, it also distinguishes itself as a valuable and highly dependable tool that can streamline the analysis process given that it embeds specifically developed benchmarks and several checks and balances to avoid (statistical) inconsistencies, by filtering out diverging results through a complex mechanism. Compared to most of the pertinent questionnaires, its distinctive characteristic is that it measures user experience based on different scales which correspond to specific areas of interest, thus allowing for gaining more focused insights. The UEQ comprises 26 questions, divided into six (6) scales as follows:

attractiveness,

efficiency,

perspicuity,

dependability,

stimulation,

innovation.

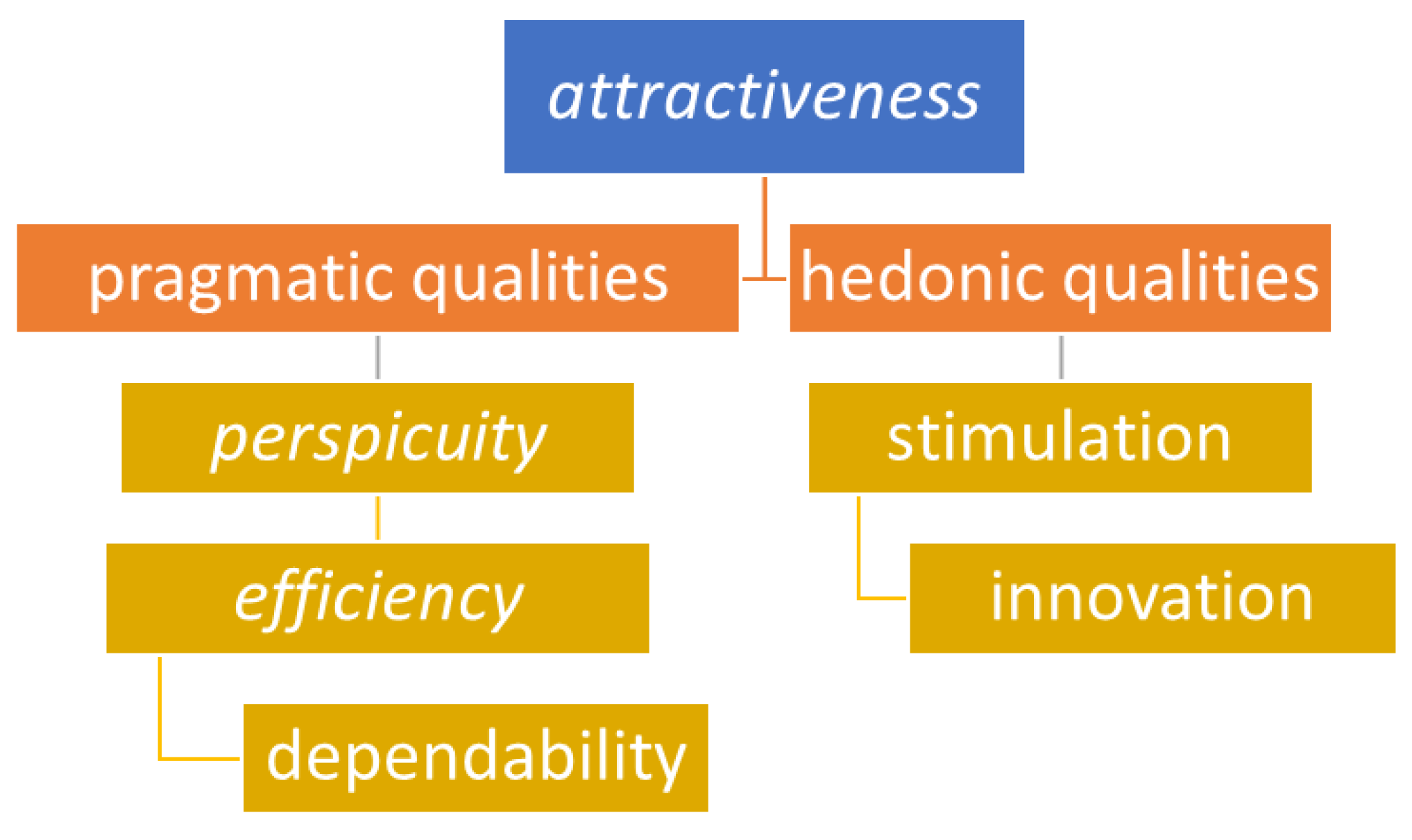

These scales belong to two broader fields: the first field concerns pragmatic or practical qualities (pragmatic qualities), which are related to efficiency (ease of use), perspicuity that, in fact, relates to the ease of getting used to the system, and dependability (degree of control). These, in broad terms, could be seen as objective aspects of the assessed application.

The second field concerns the so-called hedonic qualities. These, by and large, subjective qualities include the scale of stimulation, i.e., how exciting and motivating the use of the application is, and that of innovation, which concerns how creative, inventive and innovative the digital interaction environment is.

The two broad areas of pragmatic and subjective/hedonic qualities (the latter related to the satisfaction offered by an interactive environment) affect the overall degree of attractiveness, i.e., (a) the overall impression it leaves and (b) how much it is liked by users (attractiveness scale), which is mainly about how creative, inventive, and innovative the digital interaction environment is.

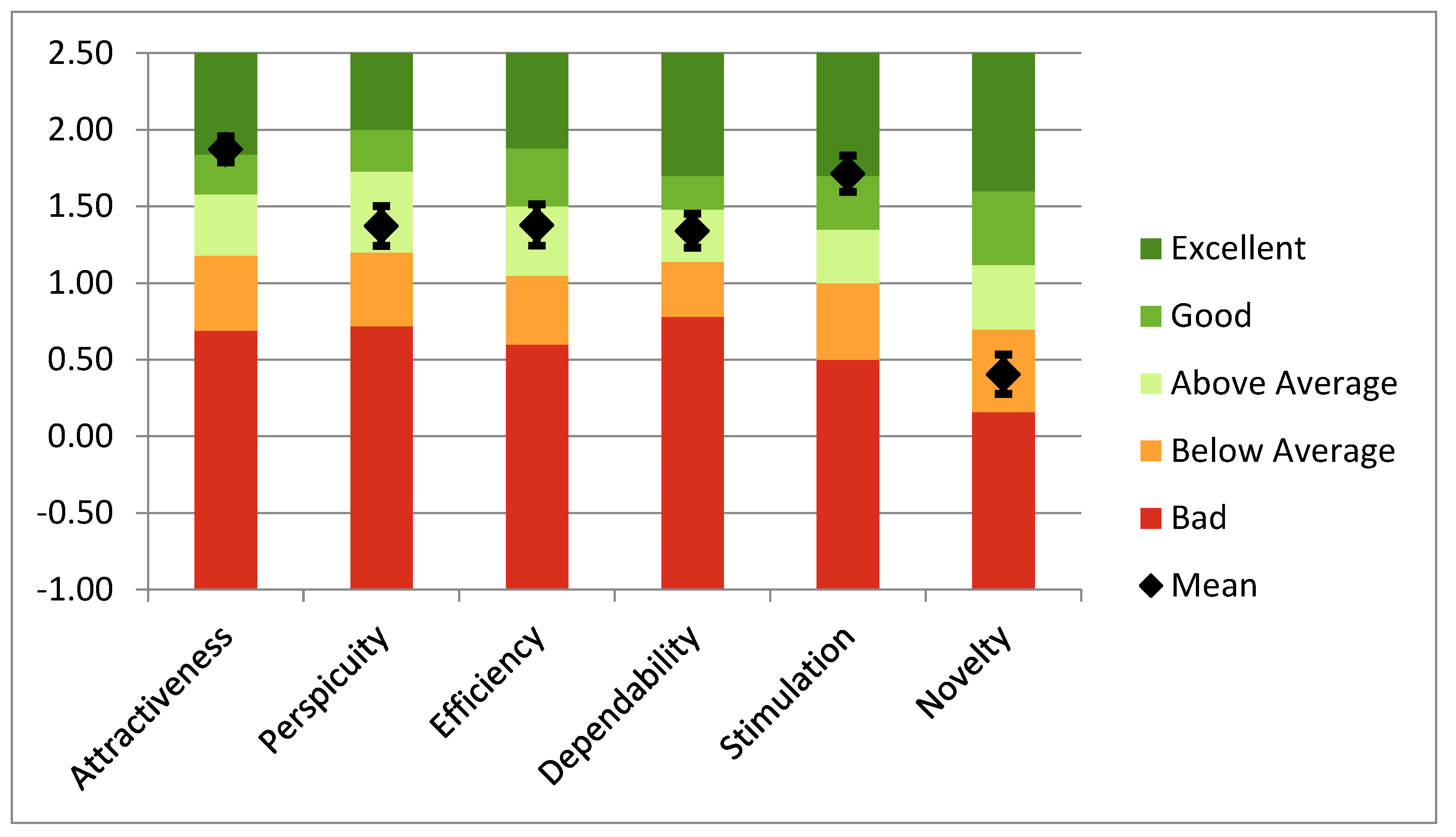

The creators of UEQ freely offer at the site manuals, related questionnaires, and spreadsheets for data analysis. In these excels, the response data input automatically produces results in relation to how the resulting average values are characterized (excellent, good, above, or below average, and poor) for each scale, based on special benchmarks that the researchers have developed [

23]. This flexible method can be applied in different evaluation scenarios [

24] and was seen as very appropriate and useful for the specific evaluation process described in this paper, given the existence of special benchmarks according to the area of use.

Figure 2.

Rendering of the scale structure of the UEQ.

Figure 2.

Rendering of the scale structure of the UEQ.

A key strength of this method, apart from the fact that it distinguishes and incorporates pragmatic and so-called hedonic qualities, which are both crucial factors, especially for a heritage-related museum environment, is that UEQ produces, as mentioned, automatically a description of the ensuing results (based on benchmarks that accrue from hundreds of cases of UEQ employment). This will add to the validity and accuracy of the second phase results. The following

Figure 3 (adapted from the UEQ handbook) provides a helpful overview of the correspondence between scales and questions.

Last but not least, the UEQ will be complemented by other methods, i.e., semi-structured interviews with visitors thereby gathering more in-depth qualitative data that can be used in tandem with the findings from questionnaires. More specifically we conducted a limited number of interviews with visitors who accepted the invitation to offer more details about their opinions verbally.