4.1. Experimental Setup

Platform: Our study experiment used heterogeneous architectures like Nvidia GPUs- H100, A100, A40, ARM A64FX, and Intel Xeon CPU. We chose different generations of GPUs and CPUs to study the impact of architectural differences. We chose different generations of GPUs and CPUs to study the effects of architectural differences.

Dataset and Model: This study employs TVM v0.8dev0 and PyTorch v0.7.1 for its implementations. As baseline tuners, we utilized XGBoost (XGB) [

40], multi-layer perception (MLP) [

41], and LightGBM (LGBM) [

42]. Our proposed tuner introduces an attention-based multi-head model, as elaborated in

Section 3.3. The baseline TenSet dataset [

11] utilized in this study comprises over 51 million measurement records. These records pertain to 2,308 subgraphs extracted from 120 networks. The baseline dataset for each subgraph contains measurements on various hardware, as delineated in

Table 1.

Baseline Measurements: For the baseline, we used the TenSet dataset, commit 35774ed. Based on the previous work [

11], we have considered 800 tasks with 400 measurements as the baseline. We used Platinum-8272 for the CPU dataset and Nvidia Tesla T4 for the GPU dataset. Further, we took record measurements on A64FX and H100 for the auto-tuner’s extensive feature analysis and evaluation.

4.2. Dataset Sampling

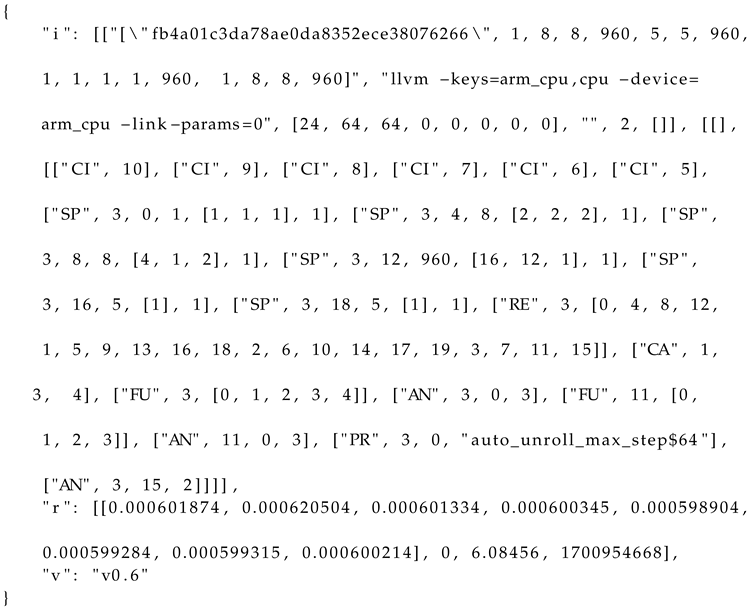

A measurement record corresponding to a task in the dataset is encapsulated within JSON files, delineating three crucial components: first, the input information and the schedules generated

(i); second, the measured performance across multiple runs

(r); and finally, the version information

(v). The concrete manifestation of such a measured record for a randomly chosen task is depicted in Listing 1. This exemplar showcases an intricate array of details, including explicit hardware specifications such as

"llvm-keys =arm_cpu, cpu-device=arm_cpu-link-params=0", intricate tensor information, and the automatically generated scheduling primitives (e.g.,

CI, SP, etc.) along with their respective parameters. To rectify erroneous measurements, we incorporate warm runs for each measurement and meticulously exclude any configurations deemed invalid. In

Table 5, a comprehensive list of scheduling primitives, derived from measurements conducted on hardware utilizing TVM, is presented. Each abbreviation corresponds to a specific scheduling step, offering a succinct representation of the intricacies involved in the optimization process. These primitives encapsulate a range of tasks, from

annotation (AN) and

fusing (FU) steps to

pragma (PR) application and

reordering (RE) procedures. Notably, the table encompasses more intricate steps such as

storage alignment (SA),

compute at (CA), and

compute in-line (CI) steps, highlighting the nuanced nature of the optimization strategies employed. Additionally, the inclusion of cache-related steps such as

cache read (CHR) and

cache write (CHW) underscores the importance of memory considerations in optimizing performance. A schedule constitutes a compilation of computational transformations, often referred to as schedule primitives, that are applied to the loops within a program, thereby modifying the sequence of computations. Diverse schedules contribute to varying degrees of locality and performance for tensor programs. Consequently, it becomes imperative to delve into the search space and autonomously generate optimized schedules to enhance overall efficiency.

| Listing 1: A Sample Measured Record On A64FX |

|

We conducted a comprehensive exploration of hardware measurements, extending our analysis to encompass two additional hardware platforms: NVIDIA’s H100 and ARM A64FX. This endeavor aimed to unravel valuable insights from the recorded data, subsequently employed as embeddings in our attention-based auto-tuner. The cumulative count of measurements amassed across both hardware platforms reached an impressive total of 9,232,000.

On the H100 hardware, the automatically generated schedule sequence lengths exhibited a diverse spectrum, spanning from 5 to 69. Conversely, within the measured records on the A64FX platform, the sequence lengths manifested a range between 3 and 54. Noteworthy variations in the occurrences of schedule primitives within a measured record were observed, and these intricacies are meticulously documented in the accompanying

Table 6. In this context, "sequence length" refers to the total length of the schedule primitives when encoded as a string, as illustrated below. The term "total occurrence" denotes the overall presence of such encoded strings across all 2308 sub-graphs. For each individual subgraph, a comprehensive set of 4000 measurements were systematically conducted.

To illustrate, an example sequence with a length of 5 may take the form of FU_SP_AN_AN_PR or CA_CA_FU_AN_PR, complete with parameter values tailored to the specific kernel. This exemplar serves as a glimpse into the rich diversity found in the measured records. Based on these insightful analyses, we have made informed decisions regarding the embedding strategies employed by our auto-tuner, ensuring a robust and nuanced approach.

As detailed in

Section 3.2, we have conducted sampling on the dataset. Utilizing data sampling techniques that prioritize the importance of features, particularly in relation to FLOPs count, enabled a reduction of 43% in the GPU dataset and 53% in the CPU dataset. The evaluation results, presented in

Table 7, indicate an overall improvement in training time.

During the dataset sampling process, ensuring the precision of the resulting cost model or tuner trained on the sampled dataset is crucial. Therefore, we conducted a comparison between the top-1 and top-5 accuracy metrics and the pairwise comparison accuracy (PCA). To elaborate briefly, when

y and

represent actual and predicted labels, the number of correct pairs,

, is computed through elementwise

followed by elementwise

on

y and

. Subsequently, we sum the upper triangular matrix of the resulting matrix. The PCA is then calculated using equation

5.

The cost models trained on both the baseline and sampled datasets exhibited comparable performance.

For a fair comparison, we trained XGB, MLP, and LGBM tuners on both the baseline and sampled datasets using three distinct split strategies outlined as follows:

-

within_task

- –

The dataset is divided into training and testing sets based on the measurement record.

- –

Features are extracted for each task, shuffled, and then randomly partitioned.

-

by_task

- –

A learning task is employed to randomly partition the dataset based on the features of the learning task.

-

by_target

- –

Partitioning is executed based on the hardware parameters.

These split strategies are implemented to facilitate a thorough and unbiased evaluation of the tuners under various scenarios. The aim is to identify and select the best-performing strategy from the aforementioned list.

To prevent biased sampling, tasks with an insufficient number of measurements were excluded. Additionally, we selected tasks based on the occurrence probability of FLOPs in tensor operations, as illustrated in

Table 3. The latency and throughput of these tasks were recorded by executing them on the computing hardware. The time-to-train gains for the sampled dataset are presented in

Table 7. Notably, in the case of CPUs, there is a time-to-train increase of up to 56% for LGBM when utilizing the

within_task split strategy during training. GPUs also exhibit an increase of up to 32%.

4.3. Tensor Program Tuning

In this section, we outline the metrics utilized to demonstrate the efficacy of our proposed approach in comparison to the baseline.

In

Figure 2, the Pairwise Comparison Accuracy (PCA), as defined in Equation

5, is illustrated for each split scheme, comparing our sampled dataset with the baseline dataset across NVIDIA A100 GPU and Intel Xeon CPU. Remarkably, the accuracy exhibits minimal variations with the introduction of the sampled dataset under the 5% error rate. This consistent trend is observed across various architectures employed in this study.

In

Table 8, the inference times for both baseline and sampled datasets are presented, considering ARM A64FX CPU, Intel Xeon CPU, NVIDIA A40, A100, H100, and RTX 2080 GPUs, with and without transfer tuning. The XGBoost tuner was employed for this analysis. Notably, the sampled dataset demonstrates significant advantages, exhibiting markedly lower inference times compared to the baseline dataset. The standard deviation in the reported inference times, both with and without transfer tuning, falls within the range of 4% to 6% relative to the mean inference time. For additional inference results, including those obtained using multi-layer perception (MLP) and LightGBM (LGBM) based tuners, as well as detailed logs for various batch sizes (1, 2, 4, 8) and diverse architectures, please refer to our GitHub repository

1. The observed trends, favoring the sampled dataset, remain consistent across different tuners and architectures considered in this study.

4.4. Evaluation of Heterogeneous Transfer Learning

Various transformations can be implemented on a given computation graph, which comprises tensor operations along with input and output tensor shapes, thereby influencing their performance on the target hardware. For instance, consider the conv2D tensor operation, where the choice of tiling is contingent upon whether the target hardware is a GPU or CPU, given the constraints imposed by grid and block size in GPUs. A tiling size deemed appropriate for a CPU may be unsuitable for a GPU, and not all combinations yield optimal performance. To identify jointly optimized schedules for a kernel and hardware, we leveraged the TVM auto-scheduler. Subsequently, we applied these optimized schedules to similar untuned kernels using an attention mechanism. To streamline the process, we organized the kernels by their occurrences and total contribution to the FLOPs count, ensuring efficiency. The tuning process focused on refining a select few significant tensor operations.

We conducted an evaluation of our methodology using three architecturally distinct networks on both CPU and GPU. In contrast to the baseline approach, where tasks were randomly tuned, we specifically selected tasks that contribute more to the FLOPs count. As outlined in

Table 9, our approach achieved mean inference times comparable to the baseline, while significantly reducing tuning time. On CPU, we observed a reduction in time of 30% for ResNet_50, 70% for MobileNet_50, and 90% for Inception_v3. However, ResNet_50 experienced a performance regression due to a lack of matching kernel shapes in the trained dataset for the given hardware. On the GPU, we achieved a remarkable 80%-90% reduction in tuned time across all networks. The greater reduction in tuning time for GPUs can be attributed to the utilization of hardware intrinsics, leveraging the inherent higher parallelism in GPUs compared to CPUs. The standard deviation associated with the reported mean inference time in

Table 9 ranges from 5% to 7%. In this evaluation, the tuner was trained on features extracted from neural networks and hardware.

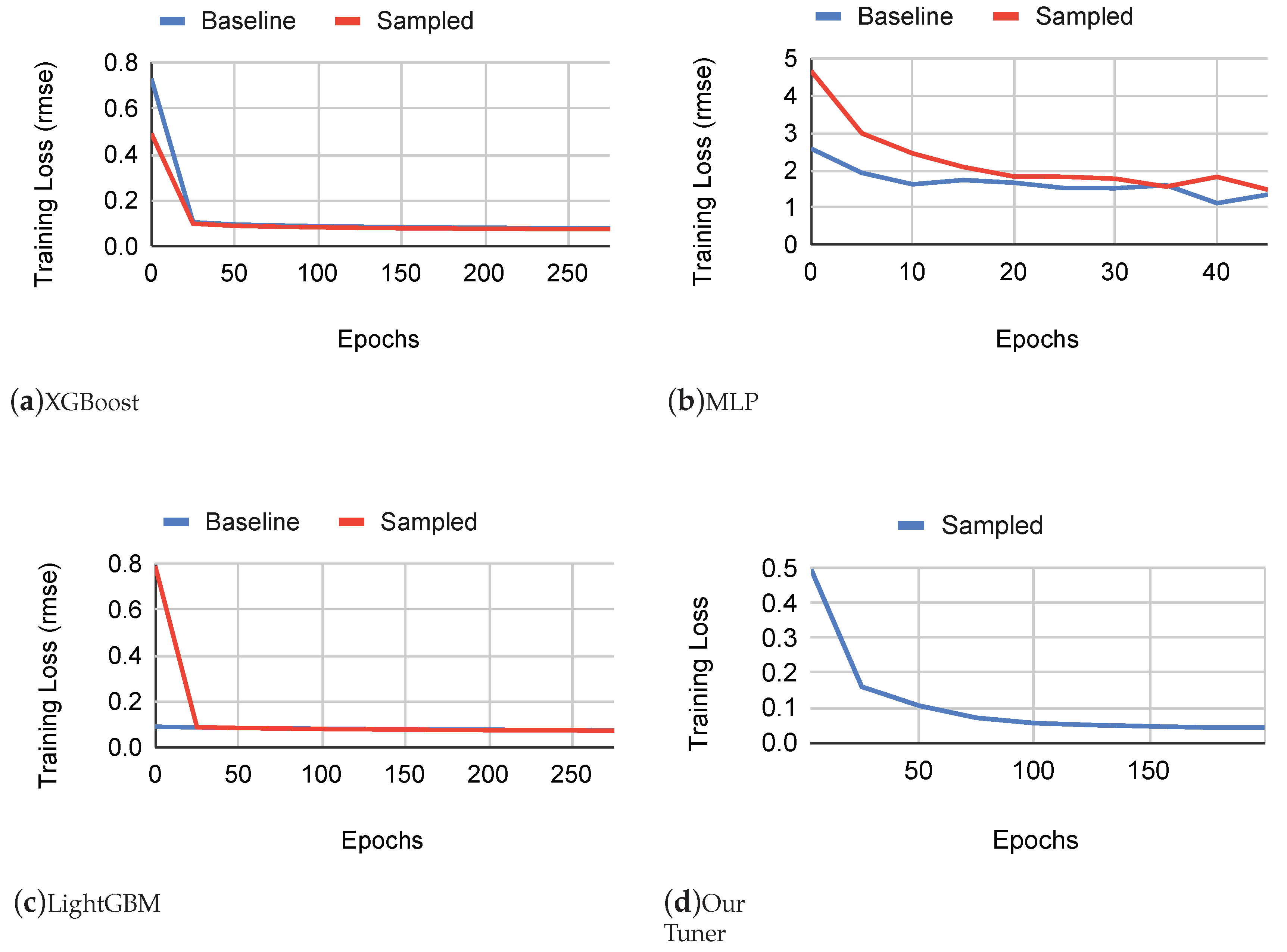

We conducted a thorough comparison of tuners based on the convergence epochs, considering both the baseline and sampled datasets. Following the design principles of TVM’s auto-scheduler, it is anticipated that tuners like XGB and MLP will converge after a substantial number of trials. To ensure an equitable evaluation, we assessed their convergence in terms of epochs. As depicted in

Figure 3, the convergence patterns for XGB, MLP, and LGBM tuners exhibit minimal differences between the two datasets. In contrast, our attention-inspired tuner showcased remarkable performance by converging in a comparable number of epochs while achieving a twofold improvement in error loss. Specifically, the root mean square error (RMSE) for our optimized tuner is 0.04 after 200 epochs, outperforming the values of 0.08 and 0.09 for XGB and LGBM, respectively. It is important to note that we are actively addressing the offline training overhead as part of our ongoing research efforts. This represents an initial phase in our research, and we are concurrently investigating potential instabilities in the tuners. A limitation inherent in our proposed methodology is its challenge in effectively transferring knowledge across hardware architectures of dissimilar classes, such as attempting knowledge transfer from one CPU class to a GPU class. This constraint becomes especially notable in situations where the dataset available for a specific hardware class is limited, leading to substantial time requirements for data collection and model training. The consequences of insufficient data may manifest in the auto-tuner’s performance, potentially resulting in suboptimal convergence. Emphasizing the significance of robust datasets for each hardware class becomes crucial to ensure the effectiveness of the knowledge transfer process and subsequent auto-tuning performance. Additionally, exploring research avenues in few-shot learning methods for hardware-aware tuning could provide valuable insights into mitigating this limitation.

Table 10 presents the assessment outcomes of the proposed tuner compared to the TenSet XGB Tuner based on Top-k scores. The table outlines each tuner’s top-1 and top-5 accuracy metrics across two target hardware platforms: H100 and A64FX. In the case of our proposed tuner, it was trained to utilize all available hardware datasets, excluding the specific hardware under examination. Subsequently, an evaluation was performed for both tuners. The network architecture employed for this evaluation was ResNet_50. Our tuner exhibited comparable performance to the XGB tuner, which was trained for the underlying hardware. Our tuner, conversely, leveraged learning schedules derived from a similar architecture. This quantitative analysis underscores the proficiency of our tuner in transfer learning, demonstrating competitive performance across the specified hardware configurations.