1. Introduction

Overweight and obesity are abnormal states of excessive fat accumulation, which can deteriorate health; the World Health Organization (WHO) classifies obesity as a type of chronic disease and emphasizes the importance of obesity management [

1]. In 2018, the rate of obesity among adults aged 20–29 years in Korea was relatively low compared to 35 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries [

2]. However, the rate of increase in the cases of obesity in Korea is very steep compared to Western countries; moreover, the OECD projects the rate of morbid obesity rate in Korea to reach 9.0% in 2030, approximately two-folds higher than that in 2015 [

3]. Obesity is a known risk factor for various physical as well as psychological disorders [

4], and the incidence of health problems begin to increase from a body mass index (BMI) of 23–27 kg/m

2 [

5], highlighting the need for weight control from an overweight stage.

2. Review of Literature

In general, women have a higher percent body fat percentage than men and thus are more likely to progress towards obesity [

2]. In particular, college students tend to be dissatisfied with and concerned about their bodies and make an attempt to unreasonably lose weight to the point of health impairment [

6,

7] as they prepare to graduate from school and enter society owing to a social atmosphere that values outer looks. Further, a majority of college students perceive themselves as obese and suffer from severe obesity stress [

8]. Obesity-related stress refers to perceived stress due to obesity [

9], which is reportedly influenced by excessively focus on obesity and past weight control experiences and is considered higher among women than men and is highly prevalent among obese individuals with a high BMI [

10,

11]. Foss and Dyrstad [

12] reported that obesity and stress are mutually influential and research focused on obesity-induced stress is warranted for appropriate weight loss and enhancement of the quality of life [

13]; however, relevant Korean studies are rare, especially those on female college students with high BMI are lacking.

Self-control is the determination and ability to control one’s inner impulses and behaviors to attain one’s own standards or goals [

13,

14]. It is associated with behaviors in various aspects, such as diet, interpersonal relationships, planning, and decision making [

15] and is reported as an important factor in facilitating desirable health behaviors [

16]. In terms of obesity, self-control contributes to controlling BMI [

17] and weight control behaviors [

18]. While individuals with good self-control are able to steadily and appropriately manage their weight by ameliorating their lifestyle, those with poor self-control exhibit impaired impulse control and engage in undesirable eating behaviors that eventually result in psychosocial health problems [

18]. Self-control is also linked to psychological adaptation [

14]. Excessive stress can impair self-control [

19], and it plays an important role in suppressing undesirable impulses and maintaining positive behaviors through regulating negative mood or emotions [

13]. Based on these findings, self-control is anticipated to have a mediating effect on the relationship between weight control behaviors and obesity-related stress in overweight or obese female college students with a high BMI; however, no previous study has investigated the effects and relationship among the three variables.

Thus, this study aimed to investigate the relationship among obesity-related stress, weight control behaviors, and self-control in overweight or obese female college students.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design of the study

This study was a descriptive cross-sectional survey using a self-reported questionnaire to investigate the degree of obesity stress, weight control behavior, and self-control of overweight and obese female university students, and confirm the mediating effect of self-control in the relationship between obesity stress and weight control behavior.

3.2. Research Questions

First, obesity-related stress affects weight control behaviors in overweight or obese female college students.

Second, self-control affects weight control behaviors in overweight or obese female college students.

Third, self-control mediates the relationship between obesity-related stress and weight control behaviors in overweight or obese female college students.

3.3. Participants of the study

The participants of this study were surveyed through convenience sampling of female students attending universities located in two metropolitan cities (Seoul and Ulsan) and two provinces (Gyeongbuk and Chungnam). This study included female students older than 18 years with a BMI of 23 kg/m2 or higher and who were currently in university, understood the purpose of this study, and agreed to participate in it. G*power 3.1.9.2 was used for sampling; the minimum number of participants was 109 when the significance level was set at 0.05, while the size of effect was set at 0.15 and the statistical power of the test was set at 0.80 when the impact factors were set at 8. Thus, a total of 120 participants were sampled considering a dropout rate of 10%.

3.4. Study tools

A structured questionnaire was used, which consisted of 46 items in total: 5 items about the general characteristics, 15 about obesity stress, 11 about self-control, and 15 about weight control behaviors.

3.4.1. Obesity stress

To measure obesity stress, the scale developed by Jang Je-hyun and Shin Gyu-ok [

20] for their research on obesity stress in female university students was used. This tool consists of 3 areas with 15 questions, including 5 about effort stress, 5 about psychological stress, and 5 about physical stress, with a minimum of 15 points and a maximum of 75 points. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1= not at all; 5= a lot), which indicates that the higher the total score, the higher the obesity stress. In Jang Je-hyun and Shin Gyu-ok’s research [

20], Cronbach’s α was 0.91, while in this study, it was 0.81.

3.4.2. Self-control

In order to measure the participants’ self-control, this study used a Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS) of 13 questions developed by Tangney et al [

13], and translated and adapted by Hong Hyun Gi et al [

21]. In the process of validating this tool, two of the existing 13 questions were deleted by the results of the internal consistency and exploratory factor analysis between the questions, and the tool consisted of the final 11 questions, which was measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1= not at all; 5= a lot).

Nine out of 11 questions were calculated as reverse questions, and the total score was distributed between a minimum of 11 points and a maximum of 55 points, which indicates that the higher the total score, the higher the self-control. In Hong Hyun-Gi’s research [

21], Cronbach’s α was 0.78, in this study was 0.82.

3.4.3. Weight control behavior

Weight control behavior was assessed using the scale developed by Jeong Hui-seop [

22] and modified and balanced by Jeong Yun-kyung and Tae Young-sook [

23]. The scale was measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1= not at all; 5= a lot) in a total of 4 areas with 15 items: 3 about exercise therapy, 8 about dietary therapy, 1 about drug therapy, and 3 about behavioral therapy. The total score was between 15 and 75, which indicates that the higher the scores, the more active the participants’ weight control behavior. The Cronbach’s α was 0.77 in Jeong Yun-kyung and Tae Young-sook’s research [

23] and 0.79 in this study.

3.5. Ethical consideration

This study was examined and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the researcher’s institution, Dongguk university (DGU IRB 20200032). On the first screen of the online survey, the contents including anonymity, voluntary participation, and rejection when participating in the study with ethical considerations, withdrawal during the study, and possible benefits and disadvantages were described. In addition, it was announced that their mobile phone numbers would only be used for a reward for responses and will be immediately disposed after this study. The participants were free to decide regarding their participation in this study when they individually reviewed the first screen and the collected data were immediately coded by the provision of an ID to conceal the identity of the participants to prevent data leakage. The participants were rewarded for their participation in this study.

3.6. Data collection

The data were collected using a structured self-reporting questionnaire for the period from November 18, 2020 to November 30, 2020 online from female university students in Seoul, Ulsan, Gyeongbuk, and Chungnam. For data collection, the first screen of the survey described the background, purpose, methods, ethical considerations, and standards for selection of the participants. If the participant consented to participating in the study, she was asked to fill out "Yes" or "Agreed" at the bottom. The upper part of the second screen contained the definition and calculation method of BMI (weight [kg] ÷ height [m2]), the participants could calculate their BMI indices personally and input them. If the index was 23 kg/m2 or higher, they would be guided to press the ‘Next’ button to participate in the survey.

3.7. Data anlaysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS/WIN 25.0 program (IBM Cop, Armonk, NY, USA) and SPSS/WIN PROCESS macro v3.4. First, general characteristics and main variables were processed for frequency, percentage, means, standard deviations, and other descriptive statistics. Second, the correlations among the participants’ obesity stress, self-control, and weight control behaviors were analyzed using Pearson‘s correlation coefficients. Third, SPSS PROCESS macrol (model 4) was used to analyze the mediating effects of self-control on the relationship between the participants’ obesity stress and their weight control behaviors. In order to confirm the statistical significance of the mediating effects, Hayes’ PROCESS macro was used for boot strapping and reported the adjusted OR. Also, this study declared significance level at P<0.05 and 95% CI.

4. Results

4.1. Simple characteristics

A total of 120 questionnaires were collected; 110 questionnaires were used for the final analysis, whereas 10 copies that could not be used for analysis owing to insufficient data were excluded. Participants’ average age was 23.21 years, while their average BMI was 25.80 kg/m

2; 58.2% of them were in the 4th year university, while 90% of them had tried to control their weights within the last year. A total of 74.5% (n=82) of them consumed alcohol less than twice per week, while 90% of them did not smoke (

Table 1).

4.2. Research question results

4.2.1. Correlations among the participants’ obesity stress, self-control and weight control behavior

The results of research question number 1 and 2 are shown in

Table 2. The participants’ average obesity stress score was 45.05±9.11, while their average self-control and their weight control behavior scores were 32.82±7.13 and 42.20±8.27, respectively (

Table 2). The participants’ obesity stress positively correlated with their weight control behaviors (r=0.25, p<0.001), while negatively correlated with their self-control (r=-0.36, p<0.001). Their self-control positively correlated with their weight control behaviors (r=0.26, p<0.001) (

Table 2).

4.2.2. Mediating effects of self-control in the relationship between obesity stress and weight control behaviors

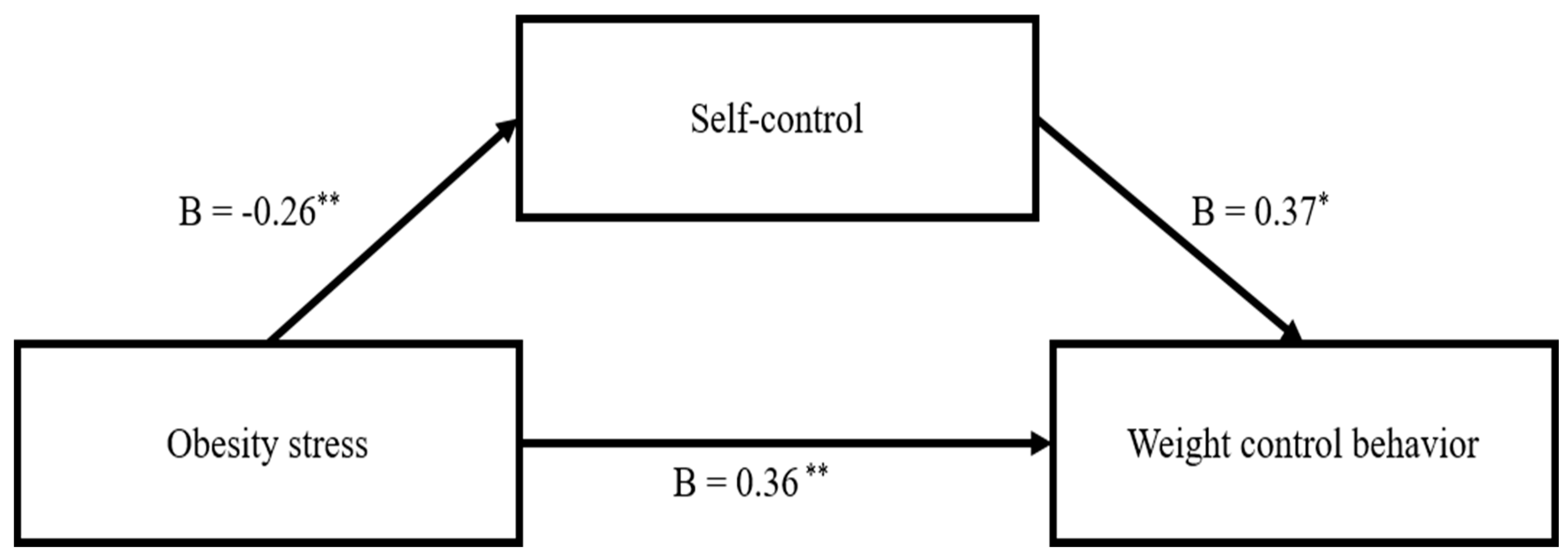

To examine the mediating effect of self-control on weight control behaviors, the following values were controlled for covariates (age, grade, experience of weight control, alcohol, and smoking). Considering the relationship between obesity stress and weight control behaviors, as in research question number 3, self-control had a partial mediating effect (

Figure 1).

Obesity stress had negative effects on self-control (Β=-0.26, p<0.001), while weight control behaviors had positive effects (Β=0.36, p<0.001). In addition, self-control had some positive effects on the weight control behaviors (Β=0.37, p=0.001) (

Table 3). Considering the relation between obesity stress and weight control behavior, the indirect effects of self-control were significant. (Β=-0.09, bootstrap 95% confidence interval –0.188, -0.02).

5. Discussion

In this study, the obesity-related stress score was 45.05±9.11. This is higher than the score (18.26±5.66) among female college students reported by Kang and Kim [

24] using the same instrument. The difference in the obesity-related stress scores seems to be attributable to the fact that we included female college students with a BMI of 23.0 kg/m

2 or higher, Kang and Kim [

24] did not use a BMI criterion for their participants. Moreover, overweight or obese female college students with a BMI of 23.0 kg/m

2 or higher suffer from greater obesity-related stress.

Our findings demonstrated that weight control behaviors increased with decreasing school year. In contrast, Yang and Byeon [

25] reported that older female college students engaged in more weight control behaviors for reasons such as being more concerned about their appearances as they prepare for employment. The difference could be attributed to the different times that the study was conducted. According to the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family [

26], 63.0% of women aged 20–29 years and 72.7% of female adolescents have weight loss goals. Further, the rate of inappropriate weight loss attempts among female middle and high school students in Korea steadily rose from 18.8% in 2014 to 26.3% in 2019 [

27]. On the other hand, the rate of weight loss attempt among adult women aged 19 years or older decreased from 70.7% in 2010–2012 surveys to 68.5% in 2016–2018 surveys [

28]. While these results are not representative of the entire population of women aged 20–29 years, the increasing rate of weight loss attempt among female middle and high school students and declining rate among adult women demonstrate that the peak age at which individuals’ desire weight loss is getting younger over time, which is also similar to our findings. In the future, further research on obesity in female adolescents and female college students is warranted to determine whether younger individuals are making weight loss attempts and whether inappropriate weight loss behaviors are practiced; studies should also plan and provide interventions accordingly.

In this study, there was a significant positive correlation between obesity-related stress and weight control behaviors. This is similar to the report by Yang and Byeon [

25] that the perceived overweight and normal weight groups more frequently engage in weight control behaviors than the perceived underweight group. Further, this is consistent with previous findings showing a significant association between weight control behaviors and obesity-related stress in female college students [

10,

29]. Thus, obesity-related stress may serve as a motivator for weight control behaviors as individuals become aware that they are obese on their own (internal stimulation) or through people around them or mass media (external stimulation) [

10]. However, some studies also report that weight control behaviors induced by obesity-related stress are often undesirable weight loss attempts, where individuals try to lose weight in a short period of time regardless of attempts to promote health, which eventually leads to failed attempts [

24,

30]. Therefore, studies should examine the predictors of weight control behaviors other than obesity-related stress, and replication studies as well as studies analyzing the associations among and the effects of various positive variables and weight control behaviors are required.

In this study, self-control had a significant partial mediating effect on the relationship between obesity-related stress and weight control behaviors. These results are similar to a previous report that self-control partially mediates the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction in adolescents [

30], and that stress affects internet addiction through the mediation of self-control [

31]. On the other hand, while self-control had a significant partial mediating effect on the relationship between obesity-related stress and weight control behaviors, we could not compare our findings directly with previous findings owing to the lack of similar studies.

Self-control is the ability to stop undesirable behavioral inclinations, such as impulses, and refrain from relevant behaviors and a psychological variable that can reduce the impact of stress [

13,

31]. Hence, many studies have demonstrated that self-control predicts better adjustment and better performance [

15,

32]. Therefore, individuals with high self-control have a sense of duty and are disciplined and goal-oriented [

33].

Considering the mediating effects, our results showed that self-control influences weight control behaviors in female college students, suggesting that improving self-control to ensure that individuals do not choose unhealthy weight control methods is essential in addition to an appropriate level of obesity-related stress in order to motivate overweight and obese female college students to engage in positive weight control behaviors. This is supported by the study on academic stressors and cyberloafing in college students by Zhou et al. [

32], where the association between the two factors was significant in students with a poor self-control, but students with a high self-control had a low risk of cyberloafing regardless of the academic stressors. Thus, it is necessary to explore other potential mediators that influence weight control behaviors in order to understand the effects of obesity-related stress on weight control behaviors.

6. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations. Although we recruited female college students from various regions by using an online survey, we could not recruit a large sample owing to the criterion of BMI 23.0 kg/m2 or higher. Further, there could be errors with the BMI measurements since they were measured individually using their weight and height by themselves. Thus, the findings of this study should be generalized with caution, and future studies should ensure accuracy in the selection of overweight and obese female college students by employing objective measurements of BMI. In addition, since this study was conducted only on overweight and obese female college students, further studies are recommended that whether there are differences in obesity related stress and variables affecting weight control behaviors according to gender.

Although the limitations of the study, this study confirmed that the importance of self-control in overweight and obese female college students as the first paper to verify the mediating effect of self-control between obesity-related stress and weight control behaviors. In addition, the results of this study highlight the need for schools and relevant organizations in the community to provide education and counselling for overweight and obese female college students to enhance self-control such that they can choose positive weight control behaviors, and these education and counselling programs should include contents pertaining to sustained appropriate diet, exercise therapy, and stress coping skills for the development of a desirable body image and better health promotion. These results would bolster the understanding of the psychosocial factors and weight control behaviors of female adolescents and female college students in school health facilities and by clinical nurses, thereby improving their support for students’ weight control efforts.

7. Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the mediating effect of self-control on the relationship between obesity-related stress and weight control behaviors in female college students, and the results confirmed that obesity-related stress was significantly correlated with weight control behaviors and self-control, while weight control behaviors were significantly correlated with self-control. Self-control partially mediated the relationship between obesity-related stress and weight control behaviors in female college students. Thus, self-control resulted in the evolvement of obesity-related stress into weight control behaviors. Hence, programs and strategies are needed to enhance self-control in order to reduce the prevalence of overweight and obese female college students. Moreover, an appropriate level of stress from obesity helps facilitate weight control behaviors; thus, programs to manage obesity-related stress should be developed and implemented to prevent the progress of such stress to aggressive weight loss attempts in a short period of time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.Y.H., P.H.K., P.S.G., and K.H.Y. Methodology, P.Y.H., P.H.K., P.S.G., and K.H.Y.; Formal Analysis, P.H.Y. and J.Y.W.; Investigation, P.H.K., P.S.G., and K.H.Y.; Data Curation, P.H.K., P.S.G., and K.H.Y.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, P.H.Y., J.Y.W., P.H.K., P.S.G., and K.H.Y.; Writing – Review & Editing, P.H.Y. and J.Y.W.; Visualization, J.Y.W.; Supervision, P.H.Y. and J.Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dongguk University Research Fund of 2022.

Data ability statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available to protect the privacy of human subjects.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dongguk University, Gyeonju, Korea (protocol code DGU IRB 20200032) in November 2020. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

A statement about the registration status of the manuscript

This manuscript is not published previously and be under consideration for publication in another journal.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and overweight; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed 9 June 2021).

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCPA). Korea health statistics 2019: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VII-3). (Report No.: 11-1351159-000027-10); Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency: Seoul, Korea, 2020. Available online: https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/sub04/sub04_04_01.do (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Organization for economic co-operation and development (OECD). Obesity Update 2017; OECD Publishing, Paris, 2017. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Obesity-Update-2017.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Carey, M.; Small, H.; Yoong, S. L.; Boyes, A.; Bisquera, A.; Sanson-Fisher, R. Prevalence of comorbid depression and obesity in general practice: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract 2014, 64, e122-e127. [CrossRef]

- Korean society for the study of obesity (KOSSO). Clinical obesity, 3rd ed.; KOMB: Seoul, 2008; pp. 140-150, ISBN 978-89-7043-645-6.

- Lee C. K.; Park, H. S. A Comparative Study on Type of Health and Practice to Promote Health following the Level of Subjective Recognition of Body Image of Female University Students. J Korean Association of Security and Safety 2017, 12, 115-130.

- Yahia, N.; El-Ghazale, H.; Achkar, A.; Rizk, S. Dieting practices and body image perception among Lebanese university students. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2011, 20, 21-28.

- Lee, H. J. Influence on in-dorm university students' body-shape perception, obesity, and weight control toward obesity stress. J Digit Converg 2013, 11, 573-583. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Y. The effect of body image and self-efficacy on obesity stress: focusing of female college students. AJMAHS 2019, 9, 565-574. [CrossRef]

- Ham, M. Y.; Lim, S. H. Effects of obesity stress and health belief on weight control behavior among nursing students. JKAIS 2017, 18, 459-468. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H. J. The effect of satisfaction of body figure and obesity stress on career preparation behavior among nursing college students. Korean J Health Commun 2019, 14, 145-153. [CrossRef]

- Foss, B.; Dyrstad, S. M. Stress in obesity: cause or consequence? Med Hypotheses 2011, 77, 7-10. [CrossRef]

- Tangney JP.; Boone AL.; Bcaumeister RF. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers 2008, 72, 271-324. [CrossRef]

- Malouf, E. T.; Schaefer, K. E.; Witt, E. A.; Moore, K. E.; Stuewig, J.; Tangney, J. P. The brief self-control scale predicts jail inmates’ recidivism, substance dependence, and post-release adjustment. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2014, 40, 334-347. [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, D. T.; Lensvelt-Mulders, G.; Finkenauer, C.; Stok, F. M.; Baumeister, R. F. Taking stock of self-control: A meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2012, 16, 76-99. [CrossRef]

- Muraven, M. Practicing self-control lowers the risk of smoking lapse. Psychol Addict Behav 2010, 24, 446-452. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Body mass index, obesity, and self-control: A comparison of chronotypes. SBP 2014, 42, 313-320. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y. S.; Ahn, H. S. Influence of subjective perception of body image and weight management on obesity stress in college women. J Korean Society of Esthetics & Cosmetics 2006, 1, 13-26.

- Maier, S. U.; Makwana, A. B.; Hare, T. A. Acute stress impairs self-control in goal-directed choice by altering multiple functional connections within the brain’s decision circuits. Neuron 2015, 87, 621-631. [CrossRef]

- Jang, J. H.; Shin, K. O. Study on body image perception, eating habits, obesity stress by BMI in female college students. J Kor Soc 2015, 21, 131-137.

- Hong, H. G.; Kim, H. S.; Kim, J. H.; Kim, J. H. Validity and reliability validation of the Korean version of the Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS). Korean J Psychol Gen 2012, 31, 1193-1210. uci: G704-001037.2012.31.4.010.

- Jeong, H. S. A study on the relationship between their health beliefs and compliance with weight control behavior in adults [dissertation]. Hanyang University.; 1987.

- Jung, Y. K.; Tae, Y. S. Factors affecting body weight control behavior of female college students. J Korean Acad Adult Nurs 2004, 16, 545-555.

- Kang, Y. H.; Kim, K. H. Body weight control behavior and obesity stress of college women. Jour. of KoCon.a. 2015, 15, 292-300. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. Y.; Byeon, Y. S. Weight control behavior in women college students and factors influencing behavior. J Korean Acad Fundam Nurs 2012, 19, 190-200. [CrossRef]

- Korea Women's Development Institute. 2016 Gender Equality Survey Analysis Study. (Report No. 2016-96); Ministry of Gender Equality and Family: Seoul, Korea, 2016. Available online: https://scienceon.kisti.re.kr/commons/util/originalView.do?cn=TRKO201900000446&dbt=TRKO&rn= (accedssed on December, 2020).

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCPA). 15th Youth Health Behavior Survey; Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency: Osong, Korea, 2019. Available online: https://www.kdca.go.kr/yhs/home.jsp?id=m03_03 (accessed 16 January 2020).

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCPA). Results of the 3rd year of the 7th National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES); Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency: Osong, Korea, 2018. Available online: https://www.k-stat.go.kr/metasvc/msea100/statsdcdta-popup?orgId=117&statsConfmNo=117002&kosisYn=Y (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- Kim, J. I. Predictors of weight control behavior according to college students' BMI, perception of body shape, obesity stress, and self-esteem. JKAIS 2016, 17, 438-448. [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y. S.; Kwon, H. J.; Baek, K. A. Subjectivity on weight control of college women. Jour. of KoCon.a. 2016, 16, 544-554. [CrossRef]

- Song, W. J.; Park, J. W. The influence of stress on internet addiction: Mediating effects of self-control and mindfulness. Int J Ment Health Addict 2019, 17, 1063-1075. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Cao, W. An experience-sampling study on academic stressors and cyberloafing in college students: The moderating role of trait self-control. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 514252. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, W.; Luhmann, M.; Fisher, R. R.; Vohs, K. D.; Baumeister, R. F. Yes, but are they happy? Effects of trait self-control on affective well-being and life satisfaction. J Pers 2014, 82, 265-277. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).