1. Introduction

The Infotainment HPC system has integrated information and technology to enhance the safety and convenience of the drivers and passengers of automotive vehicles. The integration consists of various factors such as passenger’s mobile devices, surrounding vehicles, remote servers, drivers, traffic infrastructure, environment, and so on. It is predicted that nearly all new cars made by 2035 will have internet connectivity [

1]. The integration can provide many advantages, such as access to various information as the vehicle is always connected to the internet. But the problem is the system becomes vulnerable to cyberattacks from adversaries [

2,

3]. The interconnection of the wider range of services with automobiles increases security vulnerabilities and incident of car hacking is being reported more frequently [

4]. All these facts motivate the emphasis on security research in automotive vehicles.

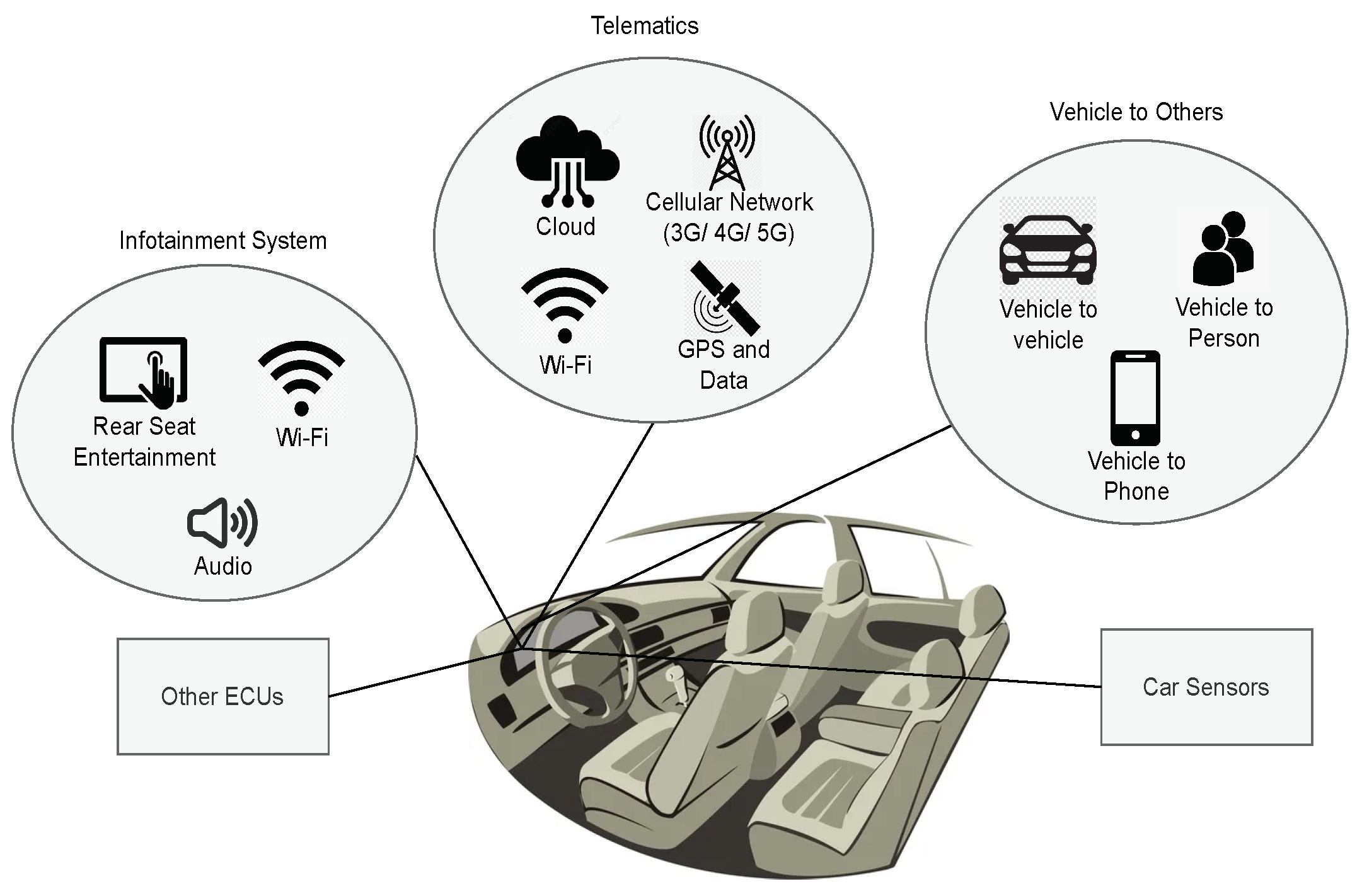

The automotive vehicle’s infotainment system intricately connects to complex networks, forming a sophisticated ecosystem that enhances the driving experience. These systems seamlessly integrate with various networks, including the internet, internal vehicle area networks (VANs) connecting electronic control units (ECUs), car sensors, and wireless technology like Wi-Fi as illustrated in

Figure 1. Internet connectivity enables real-time navigation updates, streaming services, and over-the-air software updates. Internal VANs ensure efficient data exchange among different vehicle components, while Wi-Fi connectivity enables hands-free calling and media streaming with smartphones. Telematics systems utilize cellular network for remote diagnostics and vehicle tracking, connecting to the cloud and using GPS for accessing location-related information. This network connectivity also facilitates communication with other vehicles, devices, and individuals. This intricate, heterogeneous network connectivity not only offers numerous features to drivers and passengers but also presents cybersecurity challenges, leading to continuous efforts to safeguard connected vehicles from potential threats.

The In-Vehicle Infotainment (IVI) system uses in-vehicle network services, including Wi-Fi connectivity, beside remote functionalities such as conventional navigation, radio playback, and multimedia functions to establish a link between the vehicle and the external world [

5]. Because of the existence of these remote interfaces and interconnected services, the system might become susceptible to potential vulnerabilities. The adversaries might try to access the system’s weaknesses by performing unauthorized manipulation from a remote location [

6,

7]. IVI system services were detected with a vulnerability as an adversary tried to attain root privileges and establish remote access through the Wi-Fi interface in [

8]. Such access can result in manipulation of the system’s configuration and the adversary might get access to sensitive user information [

9,

10]. As the users can access personal information through Bluetooth while driving, it can also be an attack surface for the adversary [

11]. The existing countermeasures might not be sufficient to counter these forms of attacks.

The in-vehicle applications might face security challenges, especially those related to Inter-Component Communication (ICC) have received concern in [

12]. It is identified that malicious applications might be able to manipulate or deceive the system, resulting in the potential exposure of sensitive user data to unauthorized access. One vulnerability lies in the Controller Area Network (CAN) bus, where the broadcast transmission is at risk due to the network’s bus topology. Messages are exchanged between ECUs across the entire network without authentication or encryption, posing a severe threat [

13,

14]. This vulnerability in the CAN bus could be exploited by adversaries, leading to potential vehicle attacks or even the complete takeover of ECUs through the transmission of spoofed messages [

15]. In response to these challenges, researchers have developed frameworks aimed at mitigating these security risks.

An adversary can bypass safety-critical systems in vehicles, taking control of automotive functions and potentially compromising driving performance [

16,

17,

18]. Khan et al. introduced a Microsoft STRIDE-based framework for cyber-physical systems that focuses on component vulnerabilities and their inter-dependencies, enhancing security [

19]. However, addressing vulnerabilities in each component is crucial to prevent a loss of control over the entire security system. The incorporation of Threat Analysis and Risk Assessment (TARA) becomes crucial to maintain an acceptable risk level by analyzing potential threats and implementing corresponding mitigation strategies [

20]. Nevertheless, it’s noteworthy that this framework primarily engages in theoretical threat analysis during the conceptual design phase and not during the security evaluation phase upon the vehicle’s release. Based on these studies, it is needed to address these issues to enhance modern automotive security.

To improve the security of the IVI system, the paper has focused on identifying security vulnerabilities and threats using the Microsoft threat modeling tool STRIDE at the component level. It also focused on calculating risk value to determine the potential risk of the threats using risk assessment methodologies, specifically SAHARA and DREAD. It has provided a comparative analysis of the two methods and based on that it will be easy to understand which threats to prioritize first for mitigation. Finally, generalized mitigation strategies are provided that ultimately lead to an overall improvement in the IVI system’s security [

21,

22].

The paper is arranged as follows: section 2 outlines the research methodology, section 3 outlines the evaluation of threats and risk rating, section 4 contains results and discussion, and finally, section 5 directs the paper to the conclusion.

2. Methodology

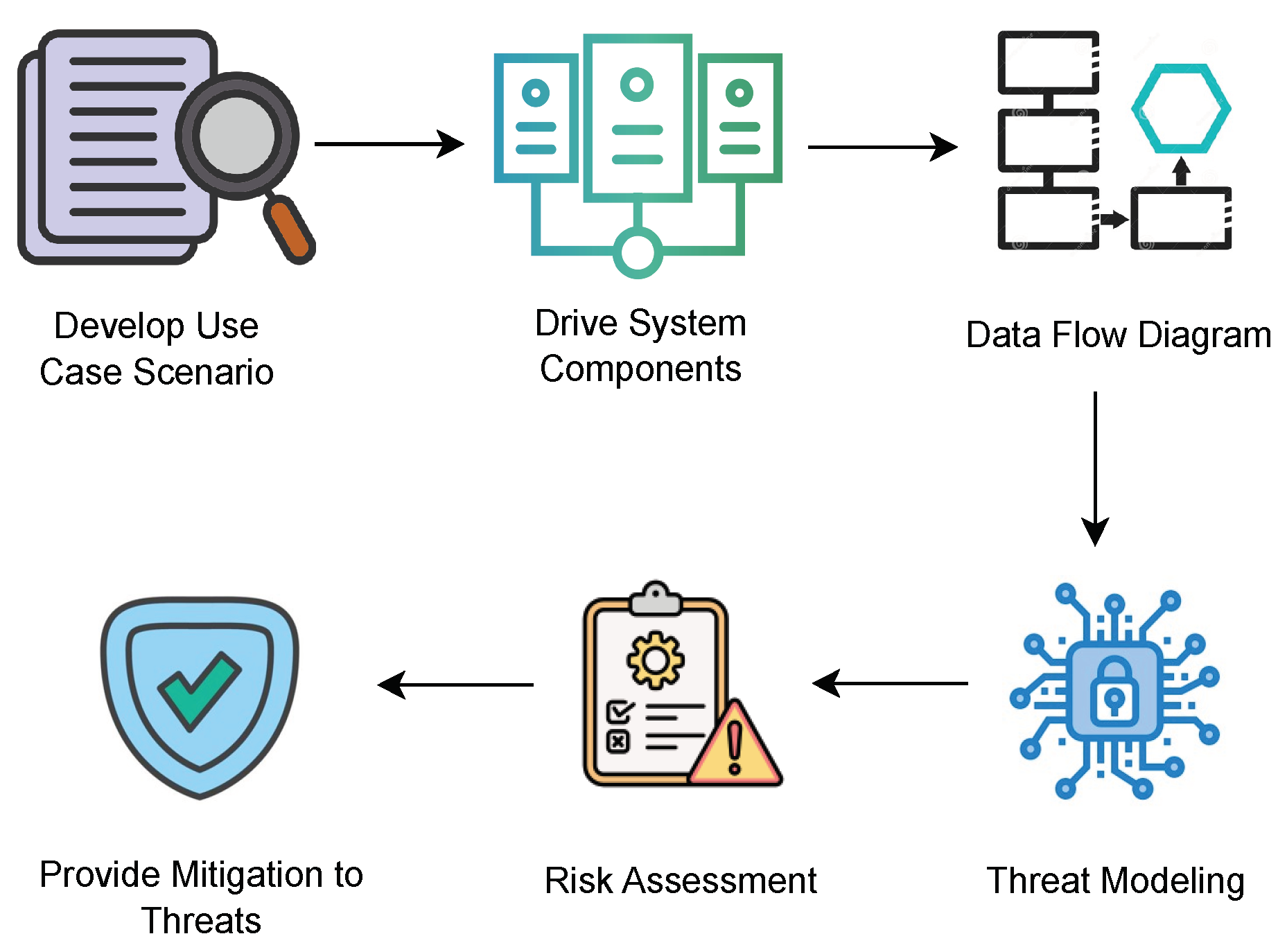

The motivation of this research is to conduct threat modeling, risk assessment and provide mitigation strategies to counter potential threats to IVI system. This is achieved by adopting the approach illustrated in

Figure 2.

During the procedure, the use case scenario explains the way through which the attack may occur by the adversary. It is important to consider the components that are proposed to develop an infotainment system. To achieve the research objective, the first step involved the identification and outlining of the system components, followed by creating a data flow diagram (DFD). Subsequently, STRIDE is employed to conduct threat modeling, resulting in the generation of a threat report that outlines the identified threats. Additionally, risk assessment is carried out using SAHARA and DREAD methodologies, allowing for the calculation of risk values. Based on the identified threats, general defense mechanisms are proposed to enhance security.

2.1. Use Case Scenario

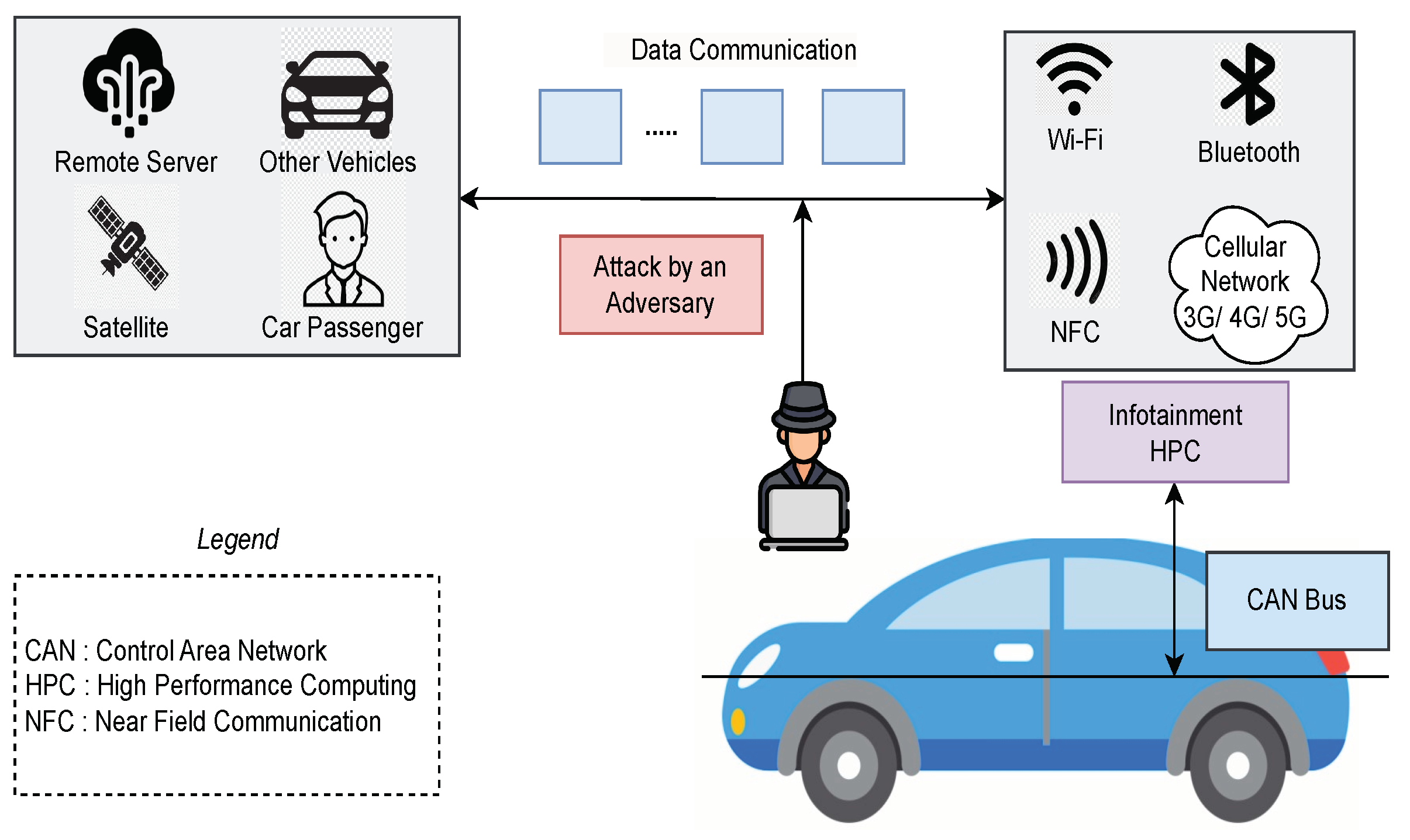

The on-board computer controls all the operations that occur in the infotainment system of the automotive vehicle. The driver may use Near Field Communication (NFC), Bluetooth, Wi-Fi and cellular network (3G /4G /5G) to transfer data and information. The CAN bus is used by the on-board computer to communicate with the sub-sections of the automotive vehicle. While communicating with the outside world or transferring data, the data paths can be attacked by the adversary, as illustrated in

Figure 3. An attacker is any person, including an insider, group, or entity that engages in adverse acts to damage, expose, disable, steal, obtain unauthorized access to, or otherwise misuse a resource [

23]. The paper considered only NFC, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi and cellular network, and CAN bus as attack surfaces but other surfaces can also be attack points for the attackers.

2.2. Proposed System Components

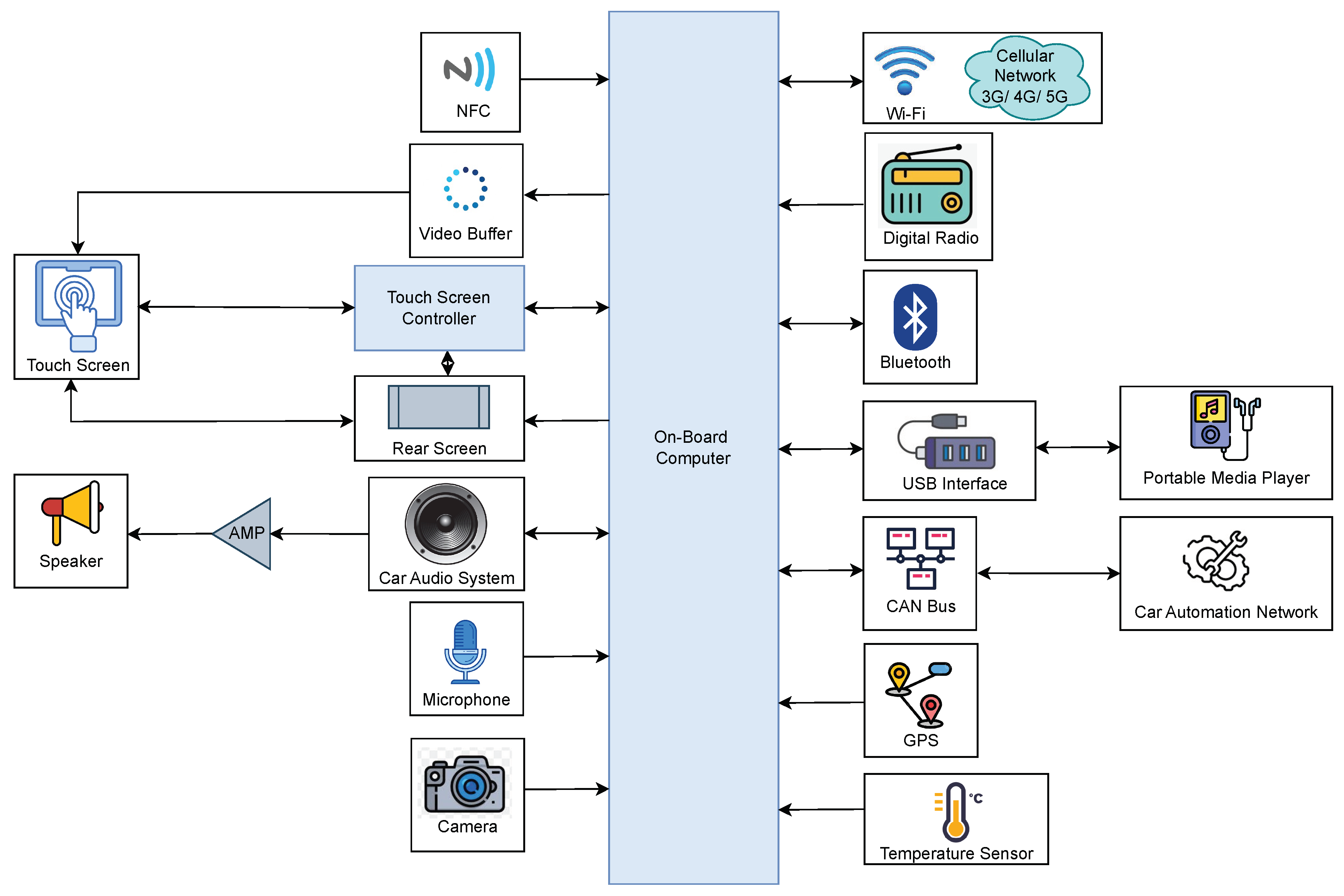

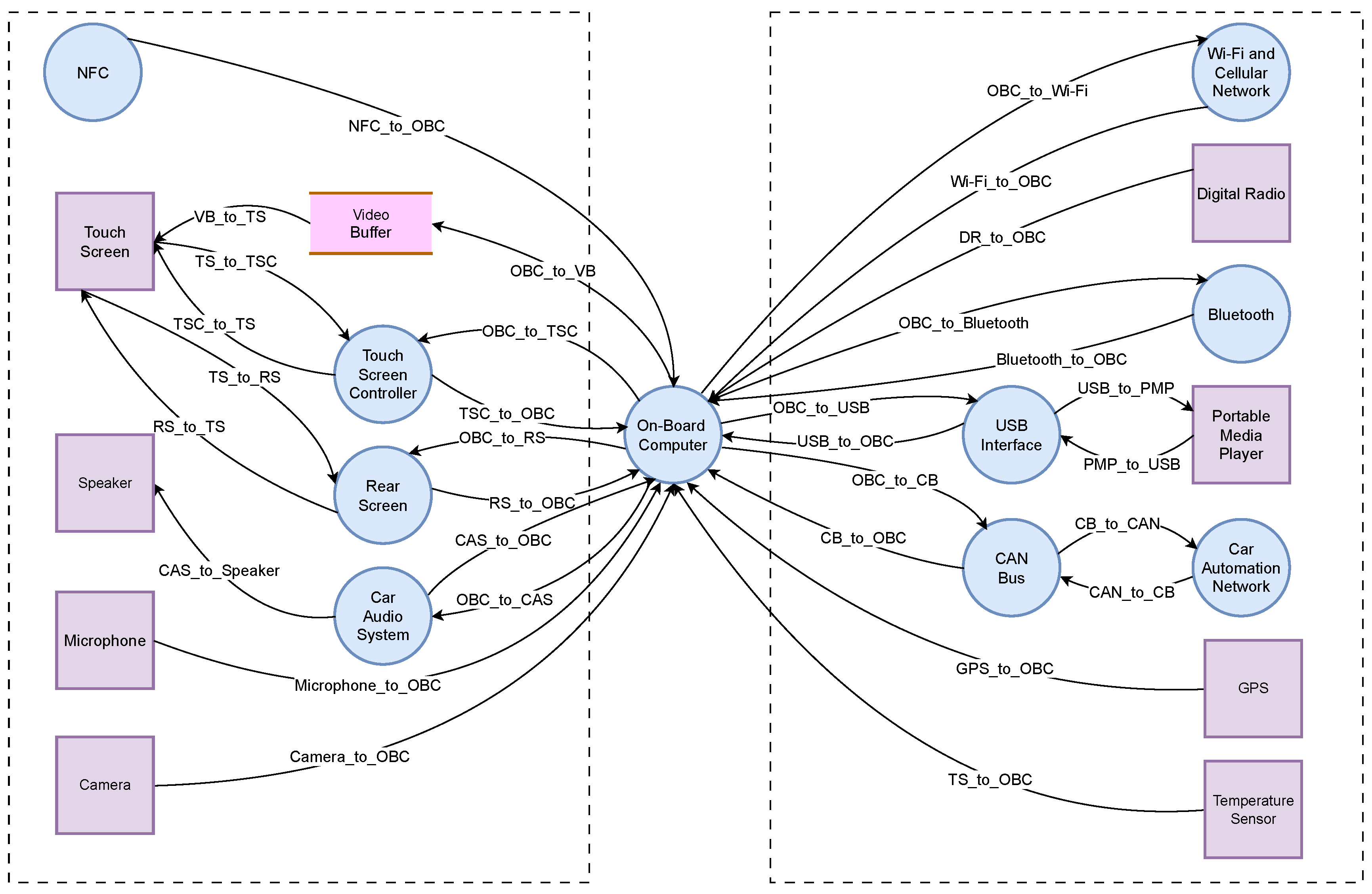

The key components of an infotainment system of an automotive vehicle with their functions and interactions are represented in

Figure 4. Each component receives input and generates output to perform specific actions. The system includes on-board computer, NFC, video buffer, touch screen controller, touch screen, rear screen, car audio system with microphone and speaker, camera, Wi-Fi and cellular network, digital radio, Bluetooth, USB interface, portable media player, CAN bus, car automation network, GPS and temperature sensor [

24,

25,

26].

A typical IVI system is centered around an on-board computer that serves as the processor of the system, to which all other system elements are connected physically or wirelessly. The core Human-Machine Interface (HMI) consists of a large touch screen placed on the dashboard for easier access by the driver [

27]. NFC enables wireless communication between devices, allowing for secure transactions, and device connectivity with a simple touch. Video buffering involves pre-loading data segments for streaming video content, which are stored in a reserved section of memory. A touchscreen controller is a circuit that connects the touchscreen sensor to the touchscreen device. If the vehicle is equipped with a rear seat, passengers can play media from various sources on monitors located behind the front-seat headrests, functioning similarly to a smart TV [

28]. The video buffer, touchscreen controller, and rear screen are connected to both the touch screen and on-board computer, allowing for data processing by the on-board computer and input control through the touch screen.

The car’s audio system is equipped with a microphone and speaker for audio input and output by the user, allowing for multimedia playback and hands-free calling. The camera captures visual data for functions like rear view display and driver assistance [

29]. The Wi-Fi and cellular network provide wireless connectivity for data communication and internet access, enabling access to web content, streaming, and email while driving [

30]. The digital radio receives and processes digital signals for audio playback. Bluetooth enables wireless communication with external devices like smartphones, while the USB interface allows for data transfer and device charging.

The portable media player plays multimedia content from external devices [

31]. The CAN bus facilitates communication among different ECUs in the vehicle, while the car automation network enables communication among different vehicle systems for automation and control. Finally, the GPS and temperature sensor provide location and temperature data, which are used for navigation and climate control functions. Overall, the proposed infotainment system includes a wide range of components that work together to provide a better infotainment experience for users in the car.

2.3. DFD

In

Figure 5, DFD provides a comprehensive depiction of all system components and their corresponding data flows. Processes, such as the on-board computer, NFC, touch screen controller, rear screen, car audio system, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi and cellular network, USB interface, CAN bus, and car automation network, are illustrated to showcase how they receive input data, execute actions, and generate output. The data flows depicted in the diagram represent the transfer of information among different system components. The video buffer is represented as a data store, responsible for the temporary storage of video data. External entities, including the touch screen, speaker, microphone, camera, digital radio, portable media player, GPS, and temperature sensor, are depicted as sources or destinations of information entering or leaving the system. Processes are symbolized by circles, data flows are indicated by arrows, data stores are represented by open rectangles and external entities are represented by rectangles.

2.4. Threat Modeling Using STRIDE

Threat modeling is the method to identify, catalog, and prioritize dangers that assist in the way of development of effective defenses against threats. Simply, it aims to address questions like "Where could the system be vulnerable to threats?", "Which threats are most significant?", and "Where are the system’s weaknesses?". According to National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) special documentation, a threat model encompasses the ability to address both the offensive and defensive dimensions of a logical entity, be it data, a host, an application, a system, or an environment [

32].

Despite the availability of various threat modeling models such as PASTA [

33], Attack Tree [

34], CVSS [

35], etc., the paper used the STRIDE threat modeling tool. This choice is based on the tool’s wide acceptance in both academia and industry, as well as its ability to identify threats at the component level. It is an open-source tool provided by Microsoft and is free [

36]. It specifically focuses on identifying vulnerabilities and weaknesses in application security.

Microsoft STRIDE is a tool for identifying cybersecurity threats, utilizing an acronym that encompasses six distinct threat categories: Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information Disclosure, Denial of Service, and Elevation of Privilege. These categories align with authenticity, integrity, non-repudiation, confidentiality, availability, and authorization. Each component of an infotainment system can be analyzed via the STRIDE method and is susceptible to one or more threats from each category.

Table 1 outlines the security properties linked to specific threat categories. As shown in

Table 1, an external entity is exposed to two threat categories, a process is susceptible to all six threat categories, a unidirectional data flow contends with three threat categories, and a data store is vulnerable to three threat categories [

37,

38]. Notably, a component may confront multiple threats within a single category.

The STRIDE tool initiates the threat modeling process by presenting a DFD. Subsequently, a threat report is generated based on this DFD, encompassing information about threat categories, threat descriptions, and proposed mitigation strategies.

Figure 6 illustrates the interaction involving STRIDE, NFC to On-Board Computer (NFC_to_OBC). According to the STRIDE tool, three distinct threats — denial of service, information disclosure, and tampering — are identified for this interaction. As data flows from NFC to on-board computer, it can become the target of the attacker in these ways. Likewise, threat reports are generated for other interactions of the infotainment system.

2.5. Risk Assessment Methodologies

The complex architecture of modern vehicles can be vulnerable to cyberattacks as the entire system is a combination of the risks associated with each interconnected component [

39]. Recently, researchers have brought to light 14 vulnerabilities found in the infotainment systems across various BMW series [

40]. This underscores the urgent need to address the risks associated with threats throughout the entire development process. According to the definition provided by the NIST, risk is defined as "A measure of the extent to which an entity is threatened by a potential circumstance or event, and typically a function of: (i) the adverse impacts that would arise if the circumstance or event occurs; and (ii) the likelihood of occurrence" [

41]. Meanwhile, risk assessment is explained as "The process of identifying, estimating, and prioritizing risks to organizational operations (including mission, functions, image, or reputation), organizational assets, individuals, and other organizations, resulting from the operation of a system" [

42].

2.5.1. SAHARA

The SAHARA methodology integrates the automotive HARA (Hazard Analysis and Risk Assessment) approach with the security-oriented STRIDE framework. The SAHARA method employs a fundamental element from the HARA approach, specifically the definition of Automotive Safety Integrity Levels (ASILs), to evaluate the outcomes of the STRIDE analysis. Threats are assessed in a manner with respect to ASIL quantification, considering the required resources (R) and expertise (K) to execute the threat, along with its threat criticality (T). Security threats that have the potential to compromise safety objectives (T = 3) can be handed over to the HARA process for further safety analysis [

43].

Table 2 provides instances of resources, expertise, and threat levels for each quantification tier of K, R, and T values [

44]. These three factors collectively define a security level (SecL), as detailed in

Table 3 [

45]. This SecL aids in determining the appropriate number of countermeasures that should be taken into account.

2.5.2. DREAD

DREAD constitutes a method for assessing risk, where its name corresponds to five assessment criteria: damage, reproducibility, exploitability, affected users, and discoverability [

46]. DREAD holds potential for conducting a more comprehensive analysis of system design. The DREAD acronym delineates:

Damage (D): Signifying the potential impact of an attack.

Reproducibility (R): Indicating the ease of replicating the attack.

Exploitability (E): Assessing the effort required to execute the attack.

Affected Users (A): The number of individuals who are going to experience the impact.

Discoverability (D): Measuring the ease of identifying the threat.

As illustrated in

Table 4, the DREAD method’s rating scheme for each threat involves assigning points from 1 to 3, with a cumulative of 15 points indicating the most severe risk.

The DREAD risk can be calculated as follows:

After summing up the scores, the outcome can vary within the 5-15 range. Subsequently, threats can be categorized: those with total ratings of 12-15 are considered high risk, ratings of 8-11 indicate medium risk, and ratings of 5-7 are considered low risk [

47].

3. Evaluation of Threats and Risk Rating

This section represents an overview of evaluating threats and the risks associated with the threats.

3.1. Analyzing Threats

Threat modeling is performed to assess the possibility of cyberattacks associated with the major data flows and processes in the DFD. It is assumed that the two sides that are marked in the trust boundary are safe. However, not all components of the DFD are analyzed for potential threats. Information and commands are transmitted through NFC, Wi-Fi and cellular network, and Bluetooth, while the CAN bus is responsible for communication with the ECUs in a vehicle. So, these points can be potential targets for unauthorized access by adversaries. Such unauthorized access could enable them to manipulate the infotainment system, gain access to personal data, control vehicle components, or disrupt normal system operations. Therefore, it is crucial to acknowledge the possibility of security issues in the infotainment system of an automotive vehicle.

Threat modeling is not performed on video buffer, touch screen controller, rear screen, touch screen, car audio system, speaker, camera, microphone, digital radio, GPS, and temperature sensor because there is no function of data or file transmission. Additionally, it is also not performed on USB interface and portable media player, because they have to be physically inserted into the system. Only the threats that cross the trust boundary are considered, which means, On-Board Computer, NFC to On-Board Computer (NFC_to_OBC), On-Board Computer to Wi-Fi and Cellular Network (OBC_to_Wi-Fi), Wi-Fi and Cellular Network to On-Board Computer (Wi-Fi_to_OBC), On-Board Computer to Bluetooth (OBC_to_Bluetooth), Bluetooth to On-Board Computer (Bluetooth_to_OBC), On-Board Computer to CAN Bus (OBC_to_CB), and CAN Bus to On-Board Computer (CB_to_OBC).

3.2. Identified Threats

By utilizing the STRIDE threat modeling tool, organizations can effectively identify potential threats by analyzing each of the categories, as it encompasses six categories. This allows organizations to assess the likelihood and impact of attacks within each category, prioritizing security efforts. With this information, organizations can develop possible mitigation strategies to safeguard their systems and networks against a wide array of potential threats.

Table 5 lists the identified threats along with additional details. The term "adversary" is frequently used in this context, referring to a person or organization that is unauthorized to access or modify information, or that attempts to bypass any security measures implemented to safeguard the system [

48].

3.3. Rating Threats

The SAHARA method, previously discussed, caters to the requirements of analyzing security threats in the early stages of automotive development (concept level). Despite its concentration on individual vehicle development and identifying security threats and safety risks during initial development phases, the method’s inter-dependencies are noteworthy. Validation of the SAHARA approach’s suitability within ISO 26262 compliant development was exhibited through a battery management system use-case, revealing a 34% increase in the identification of hazardous situations compared to traditional HARA methodologies [

49]. Therefore, the SAHARA method is integrated into this work for risk assessment.

Consequently, another risk assessment method, DREAD is adopted for quantifying threats. By quantifying threats in accordance with their associated risks, threats with the highest risk levels will be prioritized. This strategic approach optimizes risk management by tackling the most impacting threats first. That’s why the DREAD classification scheme is adopted, showing promise in facilitating a more intricate analysis of system design.

The SAHARA analysis is conducted through a conventional process, involving the determination of SecL. Additionally, the DREAD approach is employed to contrast the differences between these two rating systems. Notably, the adapted DREAD threat classification scheme proves more suitable for evaluating remote cybersecurity attacks and attacks that affect entire vehicle operations. This suitability arises from its classification factors related to potential damage and the impact on affected users. Despite the availability of numerous risk assessment methodologies, the paper chose to utilize SAHARA and DREAD due to their ability to quantify the security impact on the development of safety-related automotive vehicles at the system level. These methodologies are particularly well-suited for evaluating remote cybersecurity attacks that can impact the operation of the vehicle.

The SAHARA method designates k value of 2, indicating a moderate requirement, and R value of 2, signifying moderate resources for the computation of risk values associated with Threat No. 1. However, due to the T value being 3, the threat of an adversary spoofing processes on the on-board computer results in a high level of criticality. The cumulative values contribute to a SecL value of 1, signifying high priority.

In parallel, D, R, E, and A all receive DREAD value of 3, signaling high impact, while D obtains a value of 2, indicating medium impact. The cumulative score reaches 13, categorizing it as a high-priority threat. The computed risk values for all threats, utilizing both the SAHARA and DREAD methodologies, are presented in

Table 6.

4. Results and Discussion

In this section, the resultant threats and risks are discussed after applying the STRIDE threat model to the DFD and risk assessment methodologies, SAHARA, and DREAD to the threats. Additionally, the proposed defense mechanisms against the STRIDE threat category are outlined.

4.1. Resultant Threats and Risks

In the process of identifying cybersecurity threats, the Microsoft STRIDE tool is applied to the selected components, data flows, data stores, and external entities within the DFD. The efforts led to the recognition of a total of 34 threats, systematically classified into six STRIDE categories. For a comprehensive list of these threats and their corresponding categories, refer to

Table 5. It’s important to note that all the identified threats, as derived from the use case scenario, are potentially subjective and may exhibit variations in different scenarios. These recognized threats must be taken into account before the deployment of the infotainment HPC system in real-world automotive vehicles to ensure the safety and security of the system.

For conducting risk assessments of the identified threats, both the SAHARA and DREAD methodologies are employed. Utilizing these approaches, risk values are calculated and presented in a comparative analysis of the outcomes in

Table 6. The risk values are categorized by priority, including high, medium, and low. Using the SAHARA methodology, 29 threats are classified as high priority, while none fall under medium risk, and 5 are categorized as low priority. Employing the DREAD methodology, 31 threats are identified as high priority, 3 as medium priority, and none as low priority. The number of high-priority threats requiring immediate attention is almost similar in both methodologies. High-priority threats, which bear significant risk values, are emphasized as top priorities, demanding the immediate implementation of countermeasures.

4.2. Generalized Defense Mechanisms against STRIDE

To ensure the security and integrity of the system and protect it against potential compromises, a range of defense mechanisms should be implemented. Specifically, when dealing with threats associated with spoofing, the implementation of multi-factor authentication or biometric authentication methods proves to be highly effective in mitigating these threats within the system [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. To address tampering attacks, it is essential to employ encryption and digital signature technologies, which can bolster the system’s resistance against unauthorized alterations and data manipulation [

55,

56]. A comprehensive overview of the complete set of defense mechanisms is provided in

Table 7. These strategies collectively work to enhance the security of the system and minimize its vulnerabilities to various types of cyber threats.

5. Conclusion

The convergence of security and safety considerations within the automotive industry introduces potential threats to infotainment HPC systems. Safeguarding against cybersecurity and privacy breaches necessitates the development of proper approaches for threat detection and recovery in automotive systems. Addressing these concerns is important to the system’s real-world implementation. Our research undertook the task of identifying, categorizing, and enumerating 34 cybersecurity threats to the infotainment HPC systems, leveraging the STRIDE threat modeling tool. Risk assessment methodologies, SAHARA and DREAD, are also performed on resultant threats, and risk values are calculated to determine their priority. In response to the threat and risk categories, mitigation techniques are provided, aiming to enhance the equilibrium between security and safety concerns within the automotive sector while assuring the security of infotainment HPC systems within automotive vehicles.

In future work, threat modeling on the hardware components connected to road vehicles can be conducted. Adhering to the ISO/SAE 21434 standard for road vehicle cybersecurity may enable the identification of more threats, thereby enhancing the overall security of automotive vehicles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.A.A., S.J., K.A., and F.M.B.; methodology, P.D.; software, P.D., M.R.A.A., and S.J.; validation, K.A, M.R.A.A., S.J., F.M.B., and R.K.; formal analysis, P.D.; investigation, P.D.; resources, P.D., M.R.A.A., and S.J.; data curation, P.D., M.R.A.A., and S.J.; writing—original draft preparation, P.D., M.R.A.A., S.J., and K.A.; writing—review and editing, M.R.A.A., S.J., R.K., K.A. and F.M.B.; visualization, P.D., M.R.A.A., S.J., and K.A.; supervision, M.R.A.A., and S.J.; project administration, K.A., M.R.A.A., and F.M.B.; funding acquisition, K.A. and F.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Data Availability Statement

Will be available upon proper request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

References

- Watabe, H.; Yamada, H. Efforts toward realization of connected car society. Denso Ten Technical Review, 1, 2017; pp. 3-11.

- Hackers take Remote Control of Tesla’s Brakes and Door locks from 12 Miles Away. Available online: https://thehackernews.com /2016/09/hack-tesla-autopilot.html (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Vehicle Cybersecurity: The Jeep Hack and Beyond. Available online: https://insights.sei.cmu.edu/blog/vehicle-cybersecurity-the-jeep-hack-and-beyond (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Choi, J.; Jin, S.I. Security threats in connected car environment and proposal of in-vehicle infotainment-based access control mechanism. In Advanced Multimedia and Ubiquitous Engineering: MUE/FutureTech 2018 12, Springer Singapore, 2019; pp. 383-388.

- Takahashi, J.; Iwamura, M.; Tanaka, M. Security threat analysis of automotive infotainment systems. In 2020 IEEE 92nd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Fall), IEEE, November 2020; pp. 1-7.

- Nie, S.; Liu, L.; Du, Y. Free-fall: Hacking tesla from wireless to can bus. Briefing, Black Hat USA, 25(1), 2017; pp. 16.

- Kamkar, S. Drive it like you hacked it: New attacks and tools to wirelessly steal cars. Presentation at DEFCON, 23, 2015; pp. 10.

- Computest. The connected car -Ways to get unauthorized access and potential implications. Research paper, 2018.

- Smith, C. The car hacker’s handbook: A guide for the penetration tester. No Starch Press, 2016.

- Bolz, R.; Kriesten, R. Automotive vulnerability disclosure: Stakeholders, opportunities, challenges. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 1(2), 2021; pp. 274-288. [CrossRef]

- Renganathan, V.; Yurtsever, E.; Ahmed, Q.; Yener, A. Valet attack on privacy: A cybersecurity threat in automotive Bluetooth infotainment systems. Cybersecurity, 5(1), 2022; pp. 30. [CrossRef]

- Moiz, A.; Alalfi, M.H. An approach for the identification of information leakage in automotive infotainment systems. In 2020 IEEE 20th International Working Conference on Source Code Analysis and Manipulation (SCAM), IEEE, September 2020; pp. 110-114.

- Scalas, M.; Giacinto, G. Automotive cybersecurity: Foundations for next-generation vehicles. In 2019 2nd International Conference on new Trends in Computing Sciences (ICTCS), IEEE, October 2019; pp. 1-6.

- Iorio, M.; Reineri, M.; Risso, F.; Sisto, R.; Valenza, F. Securing SOME/IP for in-vehicle service protection. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 69(11), 2020; pp. 3450-13466. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Duan, Z.; Tehranipoor, M. Identify a spoofing attack on an in-vehicle CAN bus based on the deep features of an ECU fingerprint signal. Smart Cities, 3(1), 2020; pp. 17-30. [CrossRef]

- Koscher, K.; Czeskis, A.; Roesner, F.; Patel, S.; Kohno, T.; Checkoway, S.; McCoy, D.; Kantor, B.; Anderson, D.; Shacham, H.; Savage, S. Experimental security analysis of a modern automobile. In 2010 IEEE symposium on security and privacy, IEEE, May 2010; pp. 447-462.

- Dang, Q.A.; Khondoker, R.; Wong, K.; Kamijo, S. Threat analysis of an autonomous vehicle architecture. In 2020 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Technologies for Industry 4.0 (STI), IEEE, December 2020; pp. 1-6.

- Pascale, F.; Adinolfi, E.A.; Coppola, S.; Santonicola, E. Cybersecurity in automotive: An intrusion detection system in connected vehicles. Electronics, 10(15), 2021; pp. 1765. [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; McLaughlin, K.; Laverty, D.; Sezer, S. STRIDE-based threat modeling for cyber-physical systems. In 2017 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe), IEEE, September 2017; pp. 1-6.

- Benyahya, M.; Lenard, T.; Collen, A.; Nijdam, N.A. A Systematic Review of Threat Analysis and Risk Assessment Methodologies for Connected and Automated Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, August 2023; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Al Asif, M.R.; Hasan, K.F.; Islam, M.Z.; Khondoker, R. STRIDE-based cyber security threat modeling for IoT-enabled precision agriculture systems. In 2021 3rd International Conference on Sustainable Technologies for Industry 4.0 (STI), IEEE, December 2021; pp. 1-6.

- Salau, A.; Dantu, R.; Morozov, K.; Upadhyay, K.; Badruddoja, S. Towards a threat model and security analysis for data cooperatives. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Security and Cryptography-SECRYPT, 2022; pp. 707-713.

- Shostack, A. Threat modeling: Designing for security. John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

- Alarcón, J.; Balcázar, I.; Collazos, C.A.; Luna, H.; Moreira, F. User interface design patterns for infotainment systems based on driver distraction: A Colombian case study. Sustainability, 14(13), 2022; pp. 8186. [CrossRef]

- Quintal, F.; Lima, M. HapWheel: In-car infotainment system feedback using haptic and hovering techniques. IEEE Transactions on Haptics, 15(1), 2021; pp. 121-130. [CrossRef]

- Designing infotainment systems that are interactive, not distractive. Automotive Technical Articles - TI E2E Support Forums, 6 June 2019. Available online: https://e2e.ti.com/blog_/b/behind_the_wheel/posts/designing-infotainment-systems-that-are-interactive-not-distractive (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Meixner, G.; Häcker, C.; Decker, B.; Gerlach, S.; Hess, A.; Holl, K.; Klaus, A.; Lüddecke, D.; Mauser, D.; Orfgen, M.; Poguntke, M. Retrospective and future automotive infotainment systems—100 years of user interface evolution. Automotive user interfaces: Creating interactive experiences in the car, 2017; pp. 3-53.

- Berger, M.; Bernhaupt, R.; Pfleging, B. A tactile interaction concept for in-car passenger infotainment systems. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications: Adjunct Proceedings, September 2019; pp. 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, G.; Sener, B. Design for luxury front-seat passenger infotainment systems with experience prototyping through VR. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 36(18), 2020; pp. 1714-1733. [CrossRef]

- Josephlal, E.F.M.; Adepu, S. Vulnerability Analysis of an Automotive Infotainment System’s WIFI Capability. In 2019 IEEE 19th International Symposium on High Assurance Systems Engineering (HASE), IEEE, January 2019; pp. 241-246.

- Tashev, I.; Seltzer, M.; Ju, Y.C.; Wang, Y.Y.; Acero, A. Commute UX: Voice enabled in-car infotainment system. In Mobile HCI’09: Workshop on Speech in Mobile and Pervasive Environments (SiMPE), September 2009.

- Souppaya, M.; Scarfone, K. Guide to enterprise telework, remote access, and bring your own device (BYOD) security. NIST Special Publication, 800, 2016; pp. 46.

- Wolf, A.; Simopoulos, D.; D’Avino, L.; Schwaiger, P. The PASTA threat model implementation in the IoT development life cycle. Informatik 2020, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Chen, K.; Chang, Y.; Chen, A.; Yin, Q.; Zhang, H. A New Correlation Model of IoT Attack Based on Attack Tree. In 2021 IEEE Intl Conf on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, Intl Conf on Pervasive Intelligence and Computing, Intl Conf on Cloud and Big Data Computing, Intl Conf on Cyber Science and Technology Congress (DASC/PiCom/CBDCom/CyberSciTech), IEEE, 2021, October; pp. 930-935.

- Ali, O.; Ishak, M.K.; Bhatti, M.K.L. Internet of things security: Modelling smart industrial thermostat for threat vectors and common vulnerabilities. In Intelligent Manufacturing and Mechatronics: Proceedings of SympoSIMM 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Asif, M.R.A.; Khondoker, R. Cyber Security Threat Modeling of A Telesurgery System. In 2020 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Technologies for Industry, 2020; Vol. 4, pp. 1-6.

- Kim, K.H.; Kim, K.; Kim, H.K. STRIDE-based threat modeling and DREAD evaluation for the distributed control system in the oil refinery. ETRI Journal, 44(6), 2022; pp. 991-1003. [CrossRef]

- Tany, N.S.; Suresh, S.; Sinha, D.N.; Shinde, C.; Stolojescu-Crisan, C.; Khondoker, R. Cybersecurity Comparison of Brain-Based Automotive Electrical and Electronic Architectures. Information, 13(11), 2022; pp. 518. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Bryans, J.; Sabaliauskaite, G. Framework for calculating residual cybersecurity risk of threats to road vehicles in alignment with ISO/SAE 21434. In International Conference on Applied Cryptography and Network Security, Cham: Springer International Publishing, June 2022; pp. 235-247.

- Birch, J.; Rivett, R.; Habli, I.; Bradshaw, B.; Botham, J.; Higham, D.; Jesty, P.; Monkhouse, H.; Palin, R. Safety cases and their role in ISO 26262 functional safety assessment. In Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security: 32nd International Conference, SAFECOMP 2013, Toulouse, France, Proceedings 32, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 24-27 September 2013; pp. 154-165.

- Dempsey, K.L.; Johnson, L.A.; Scholl, M.A.; Stine, K.M.; Jones, A.C.; Orebaugh, A.; Chawla, N.S.; Johnston, R. Information security continuous monitoring (ISCM) for federal information systems and organizations, 2011.

- Grassi, P.A.; Fenton, J.L.; Garcia, M.E. Digital identity guidelines [including updates as of 12-01-2017], 2017.

- Macher, G.; Armengaud, E.; Brenner, E.; Kreiner, C. Threat and risk assessment methodologies in the automotive domain. Procedia Computer Science, 83, 2016; pp. 1288-1294.

- Macher, G.; Armengaud, E.; Brenner, E.; Kreiner, C. A review of threat analysis and risk assessment methods in the automotive context. In Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security: 35th International Conference, SAFECOMP 2016, Trondheim, Norway, Proceedings 35, Springer International Publishing, 21-23 September 2016.

- Macher, G.; Sporer, H.; Berlach, R.; Armengaud, E.; Kreiner, C. SAHARA: A security-aware hazard and risk analysis method. In 2015 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition, IEEE, March 2015; pp. 621-624.

- Available online: https://owasp.org/www-community/Threat_Modeling_Process#subjective-model-dread (accessed on 09 June 2023).

- Cagnazzo, M.; Hertlein, M.; Holz, T.; Pohlmann, N. Threat modeling for mobile health systems. In 2018 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference Workshops (WCNCW), IEEE, April 2018; pp. 314-319.

- Dang, Q. Recommendation for applications using approved hash algorithms. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2008.

- Macher, G.; Höller, A.; Sporer, H.; Armengaud, E.; Kreiner, C. A combined safety-hazards and security-threat analysis method for automotive systems. In Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security: SAFECOMP 2015 Workshops, ASSURE, DECSoS. ISSE, ReSA4CI, and SASSUR, Delft, The Netherlands, Proceedings 34, Springer International Publishing, 22 September 2015; pp. 237-250.

- Ahmed, A.A.; Ahmed, W.A. An effective multifactor authentication mechanism based on combiners of hash function over internet of things. Sensors, 19(17), 2019; pp. 3663. [CrossRef]

- Modarres, A.M.A.; Sarbishaei, G. An improved lightweight two-factor authentication potocol for IoT applications. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, H.; Hashim, S.J.; Ahmad, S.M.S.; Hashim, F.; Chaudhary, M.A. SELAMAT: a new secure and lightweight multi-factor authentication scheme for cross-platform industrial IoT systems. Sensors, 21(4), 2021; pp. 1428. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Sahri, N.M.; Karie, N.M.; Ahmed, M.; Valli, C. Biometrics for internet-of-things security: A review. Sensors, 21(18), 2021; pp. 6163. [CrossRef]

- Tait, B.L. Aspects of biometric security in internet of things devices. Digital Forensic Investigation of Internet of Things (IoT) Devices, 2021; pp. 169-186.

- Bhandari, R.; Kirubanand, V.B. Enhanced encryption technique for secure IoT data transmission. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 9(5), 2019; pp. 3732. [CrossRef]

- Alizai, Z.A.; Tareen, N.F.; Jadoon, I. Improved IoT device authentication scheme using device capability and digital signatures. In 2018 International Conference on Applied and Engineering Mathematics (ICAEM), IEEE, September 2018; pp. 1-5.

- Ali, A.; Ahmed, M.; Khan, A. Audit logs management and security- A survey. Kuwait Journal of Science, 48(3), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Gong, L.; Cao, J.; Gu, Z. The current research of IoT security. In 2019 IEEE Fourth International Conference on Data Science in Cyberspace (DSC), IEEE, June 2019; pp. 346-353.

- Mbarek, B.; Ge, M.; Pitner, T. Blockchain-based access control for IoT in smart home systems. In Database and Expert Systems Applications: 31st International Conference, DEXA 2020, Bratislava, Slovakia, September 14–17, 2020, Proceedings, Part II 31, Springer International Publishing, 2020; pp. 17-32.

- Borgiani, V.; Moratori, P.; Kazienko, J.F.; Tubino, E.R.; Quincozes, S.E. Toward a distributed approach for detection and mitigation of denial-of-service attacks within industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 8(6), 2020; pp. 4569-4578. [CrossRef]

- Tandon, R. A survey of distributed denial of service attacks and defenses. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.01345. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, K.G.; Upadrashta, R.; Ramachandra, G. Securing Over-the-Air Firmware Updates (FOTA) for Industrial Internet of Things (IIOT) Devices. In 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST), IEEE, November 2022; pp. 1-8.

- Rizvi, S.; Orr, R.J.; Cox, A.; Mehmood, M.; Amin, R.; Muslam, M.M.A.; Xie, J.; Aldabbas, H. Privilege Escalation Attack Detection and Mitigation in Cloud using Machine Learning. IEEE Access, 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).