Submitted:

26 December 2023

Posted:

26 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

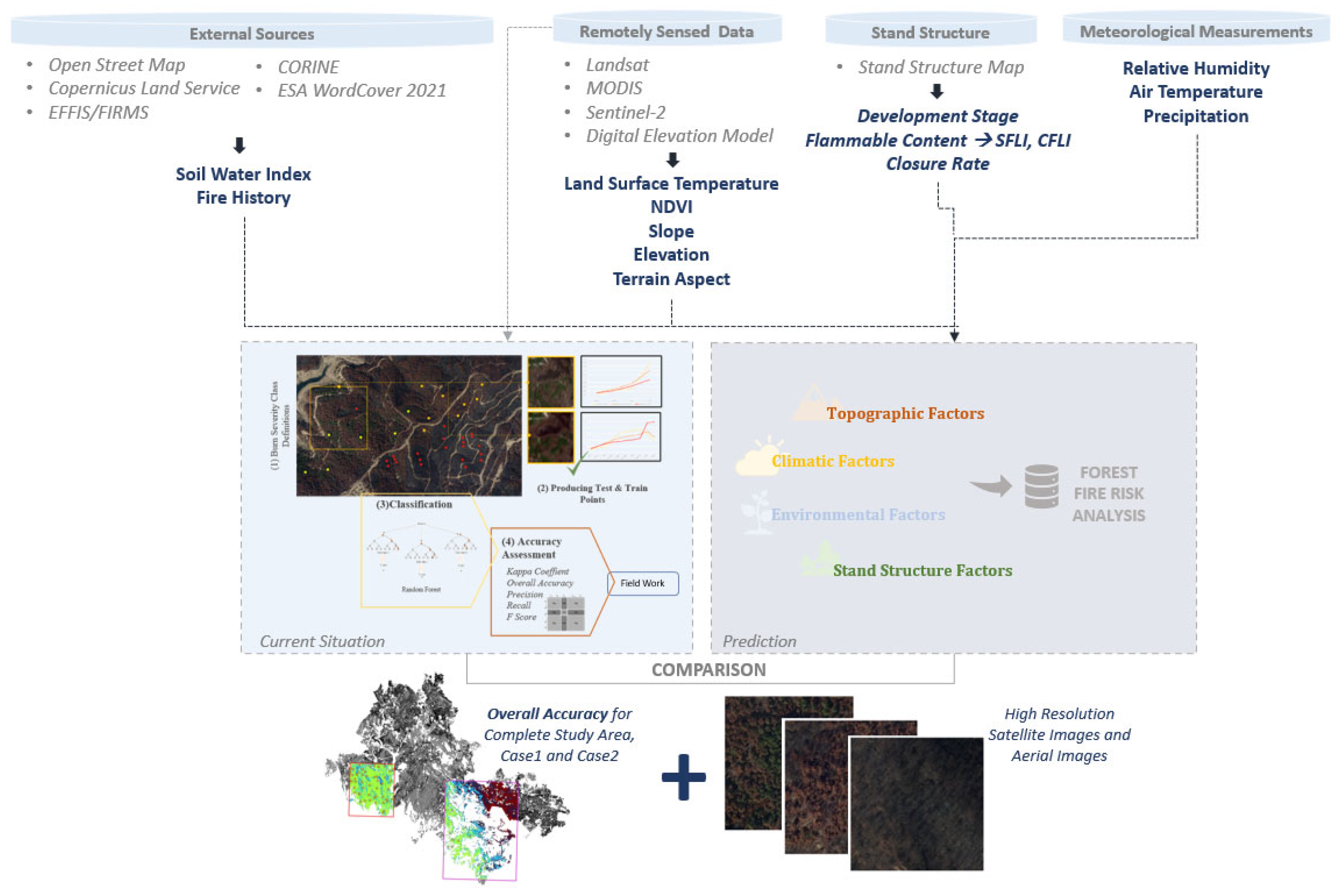

2. Materials and Methods

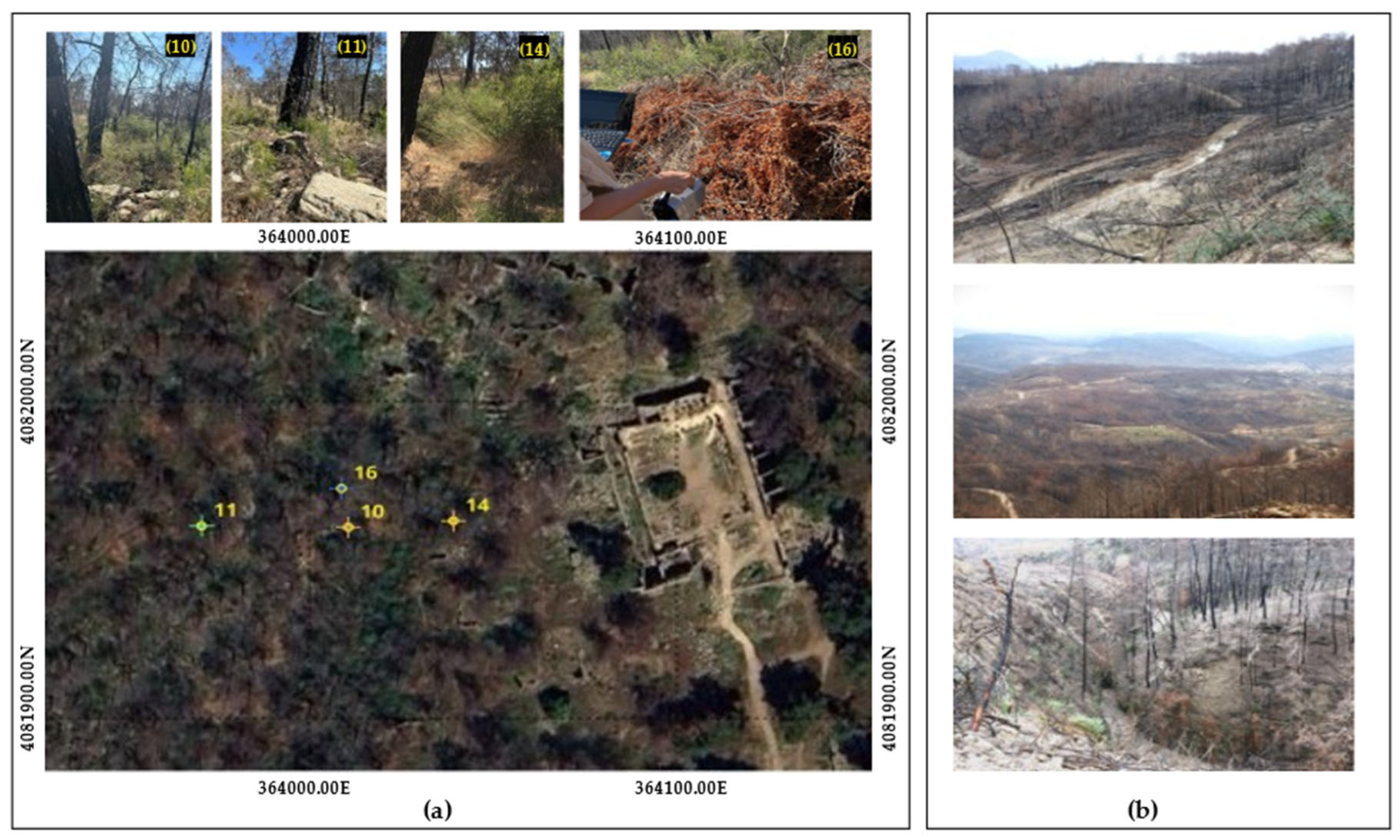

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Burn severity

2.3.2. Risk Assessment

2.3.2.1. The fuzzy AHP model (FAHP)

3. Results

| Evaluated Factors | F-Score |

Overall Accuracy |

||

|

Low Burn Severity |

Moderate Burn Severity |

High Burn Severity |

||

| Topographic Factors | 0.2581 | 0.4110 | 0.5089 | 0.4167 |

| Climatic Factors | 0.4634 | 0.3710 | 0.6705 | 0.5288 |

| Environmental Factors | 0.0779 | 0.4184 | 0.4800 | 0.3936 |

| Stand Structure Factors | 0.3648 | 0.2074 | 0.4660 | 0.3640 |

| SFLI | 0.4953 | 0.3846 | 0.2439 | 0.4131 |

| CFLI | 0.4129 | 0.4533 | 0.2105 | 0.3846 |

|

Pre-Fire Risk Analysis |

0.4959 | 0.2920 | 0.5432 | 0.4476 |

Discussion

Conclusiond

Acknowledgments

References

- Tepley, A.J.; Thomann, E.; Veblen, T.T.; Perry, G.L.W.; Holz, A.; Paritsis, J.; Kitzberger, T.; Anderson-Teixweria, K.J. Influences of fire–vegetation feedbacks and post-fire recovery rates on forest landscape vulnerability to altered fire regimes. Journal of Ecology. 2018, 106:1925–1940. [CrossRef]

- Brotons, L.; Aquilué, N.; De Cáceres, M.; Fortin, M.J.; Fall, A. How fire history, fire suppression practices and climate change affect wildfire regimes in Mediterranean landscapes. PLOS one. 2013, 8 (5), p.e62392. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.; Ascoli, D.; Safford, H.; Adams, M.A.; Moreno, J.M.; Pereira, J.M.; Catry, F.X.; Armesto, J.; Bond, W.; González, M.E.; Curt, T. Wildfire management in Mediterranean-type regions: paradigm change needed. Environmental Research Letters 2020, 15(1), p.011001. [CrossRef]

- Chicas, S.D.; Nielsen, Ø.J. Who are the actors and what are the factors that are used in models to map forest fire susceptibility? A systematic review. Natural Hazards. 2022, 114 (3), 2417-2434. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, K.L.; Dickinson, M.B.; Bova, A.S. A way forward for fire-caused tree mortality prediction: modeling a physiological consequence of fire. Fire Ecology. 2010, 6, 80-94. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Kang, W.; Park, K.H.; Kim, C.B. and Girona, M.M. Predicting post-fire tree mortality in a temperate pine forest, Korea. Sustainability. 2021, 13(2), p.569. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.P.; Calkin, D.E. Uncertainty and risk in wildland fire management: a review. Journal of environmental management. 2011, 92(8), pp.1895-1909. [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Ager, A.A. A review of recent advances in risk analysis for wildfire management. International journal of wildland fire. 2013, 22(1), pp.1-14. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.; Vega-Garcia, C.; Chuvieco, E. Human-caused wildfire risk rating for prevention planning in Spain. Journal of Environmental Management. 2009, 90, 1241–1252. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Riva, J. Assessing the effect on fire risk modeling of the uncertainty in the location and cause of forest fires. In Viegas DX (eds), Advances in Forest Fire Research. 2014, 1061–72. Coimbra, Portugal, da Universidade de Coimbra.

- Finney, M. A. The challenge of quantitative risk analysis for wildland fire. Forest ecology and management. 2005, 211(1-2), 97-108. [CrossRef]

- Maniatis, Y.; Doganis, A.; Chatzigeorgiadis, M. Fire Risk Probability Mapping Using Machine Learning Tools and Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis in the GIS Environment: A Case Study in the National Park Forest Dadia-Lefkimi-Soufli, Greece. Applied Sciences. 2022, 12(6), 2938. [CrossRef]

- Saglam, B.; Boyatan, M.; Sivrikaya, F. An innovative tool for mapping forest fire risk and danger: case studies from eastern Mediterranean. Scottish Geographical Journal. 2023, 139 (1-2), 160-180. [CrossRef]

- Sari, F. Identifying anthropogenic and natural causes of wildfires by maximum entropy method-based ignition susceptibility distribution models. Journal of Forestry Research. 2023, 34, 355–371. [CrossRef]

- Bot, K.; Borges, J.G. A Systematic Review of Applications of Machine Learning Techniques for Wildfire Management Decision Support. Inventions. 2022, 7, 15. [CrossRef]

- Akıncı, H. A.; Akıncı, H. Machine learning based forest fire susceptibility assessment of Manavgat district (Antalya), Turkey. Earth Science Informatics. 2023, 16, 397–414. [CrossRef]

- Satir, O.; Berberoglu, S.; Donmez, C. Mapping regional forest fire probability using artificial neural network model in a Mediterranean forest ecosystem. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk. 2016, 7 (5), 1645-1658. [CrossRef]

- Nuthammachoti, N.; Stratoulias, D. A GIS- and AHP-based approach to map fire risk: a case study of Kuan Kreng peat swamp forest, Thailand. Geocarto International. 2021, 36 (2), 212-225. [CrossRef]

- Güngöroğlu, C. Determination of Forest Fire Risk with Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process and its Mapping with the Application of GIS: The Case of Turkey/Çakırlar. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal. 2017, 23 (2), 388-406. [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, A.; Manzoor, S.A.; Lukac, M. Areas of the Terai Arc landscape in Nepal at risk of forest fire identified by fuzzy analytic hierarchy process. Environmental Development. 2023, 45: 100810. [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Roodposhti, M.S.; Jankowski, P.; Blaschke, T. A GIS-based extended fuzzy multi-criteria evaluation for landslide susceptibility mapping. Computers & Geosciences. 2014, 73, 208–221. [CrossRef]

- Bakırman, T.; Gümüşay, M.U.; Musaoğlu, N.; Tanık, A.G. Development of Sustainable Wetland Management Strategies by using Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Web-Based GIS: A Case Study from Turkey. Transactions in GIS. 2021, 26 (3), 1589-1608. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Nikhil, S.; Ajin, R.S.; Danumah, J.H.; Saha, S.; Costache, R.; Rajaneesh, A.; Sajinkumar, K.S.; Amrutha, K.; Johny, A.; Marzook F.; Mammen P.C.; Abdelrahman, K.S.; Fnais, M.; Abioui, M. Wildfire Risk Zone Mapping in Contrasting Climatic Conditions: An Approach Employing AHP and F-AHP Models. Fire. 2023, 6, 44. [CrossRef]

- Sari, F. Forest fire susceptibility mapping via multi-criteria decision analysis techniques for Mugla, Turkey: A comparative analysis of VIKOR and TOPSIS. Forest Ecology and Management. 2021, 480, 118644. [CrossRef]

- Sivrikaya, F.; Küçük, Ö. Modeling forest fire risk based on GIS-based analytical hierarchy process and statistical analysis in Mediterranean region. Ecological Informatics. 2022, 68, 101537. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, K.L.; Dickinson, M.B.; Bova, A.S. A Way Forward For Fire-Caused Tree Mortality Prediction: Modeling A Physiological Consequence of Fire. Fire Ecology. 2010, 6 (1), 80-94. [CrossRef]

- Hood, S.M. Physiological responses to fire that drive tree mortality. Plant Cell Environment. 2021, 44:692–695. [CrossRef]

- Etchell, H.; O’Donnell, A.J.; McCaw, M.L.; Grierson, P. Fire severity impacts on tree mortality and post-fire recruitment in tall eucalypt forests of southwest Australia. Forest Ecology and Management. 2020, 459 (1), 117850. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.L.; Ryan, K.C. Modeling Postfire Planning Conifer Mortality for Long-range planning. Environmental Management. 2012, 10 (6), 797-808. [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Zhang, Z.; Long, T.; He, G.; Wang, G. Monitoring Landsat based burned area as an indicator of Sustainable Development Goals. Earth’s Future. 2021, 9, e2020EF001960. [CrossRef]

- Roces-Díaz, J.V.; Santin, C.; Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Doerr, S.H. A global synthesis of fire effects on ecosystem services of forests and woodlands. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2022, 20 (3), 170–178. [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Durrant, T.; Boca, R.; Maianti, P.; Libertá, G.; Artés-Vivancos, T.; Oom, D.; Branco, A.; de Rigo, D.; Ferrari, D.; Pfeiffer, H.; Grecchi, R.; Onida, M.; Löffler, P. 2022. Forest Fires in Europe, Middle East and North Africa 2021, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. 2022, JRC130846. [CrossRef]

- Manavgat Orman İşletme Müdürlüğü, Orman Amenajman Planları Meşcere Haritaları, 2021.

- Roy, D.P.; Huang, H.; Boschetti, L.; Giglio, L.; Yan, L.; Zhang, H.H.; Li, Z. Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 burned area mapping - A combined sensor multi-temporal change detection approach. Remote Sensing of Environment. 2019, 231, 111254. [CrossRef]

- İsmailoğlu, İ.; Musaoğlu, N. Burn severity assessment with different remote sensing products for wildfire damage analysis, SPIE Conference Proceeding. October 4, 2023, San Diego, USA.

- Bennett, M.; Fitzgerald, S.; Parker, B.; et al. Reducing Fire Risk on Your Forest Property. A Pacific Northwest.

- Extension Publication. 2010, 618. Available at: https://catalog.extension.oregonstate.edu/sites/catalog/files/project/pdf/pnw618.pdf.

- Pereira, M.G.; Trigo, R.M.; Da Camara, C.C.; et al. Synoptic patterns associated with large summer forest fires in Portugal. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 2005, 129, 11–25. [CrossRef]

- Bonora, L.; Conese, C.; Marchi, E.; Tesi, E.; Montorselli, N.B. Wildfire occurrence: Integrated model for risk analysis and operative suppression aspects management. American Journal of Plant Sciences. 2013. 4, 705–710. [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, L.; Deeming, J.E.; Burgan, R.E.; Cohen, J.D. The 1978 National Fire-Danger Rating System: technical documentation. USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, General Technical Report INT-169. 1984, (Ogden, UT).

- Possell, M.; Bell, T. L. The influence of fuel moisture content on the combustion of Eucalyptus foliage. International journal of wildland fire. 2013, 22 (3), 343-352. [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A. D.; Rustigian-Romsos, H.; Mann, M.; Conlisk, E.; Moritz, M.A.; Ackerly, D. The relative influence of climate and housing development on current and projected future fire patterns and structure loss across three California landscapes. Global Environmental Change. 2019, 56, 41-55. [CrossRef]

- Sharples, J. J.; McRae, R. H. D.; Weber, R. O.; Gill, A. M. Simple indices for assessing fuel moisture content and fire danger rating. Fire Note. 2010, 65, 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Flatley, W.T.; Lafon, C.W.; Grissino-Mayer, H.D. Climatic and topographic controls on patterns of fire in the southern and central Appalachian Mountains, USA. Landscape Ecology. 2011, 26:195–209. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M. Combining forest structure data and fuel modelling to classify fire hazard in Portugal. Annals of Forest Science. 2009, 66: 415p9. [CrossRef]

- Bond-Lamberty, B.; Wang, C.; Gower, S. Aboveground and belowground biomass and sapwood area allometric equations for six boreal tree species of northern Manitoba. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 2002, 32, 1441-1450. [CrossRef]

- Güngöroğlu, C.; Güney, Ç. O.; Sarı, A.; Serttaş, A. Estimation of fuel load in maquis type vegetation of Antalya. International Symposium on New Horizons in Forestry, October 18-20, 2017, Isparta / Turkey.

- Küçük, Ö.; Bilgili, E.; Sağlam, B. Estimating crown fuel loading for Calabrian pine and Anatolian black pine. International Journal of Wildland Fire. 2008, 17(1), 147–54. [CrossRef]

- Küçük, Ö.; Sağlam, B.; Bilgili, E. Canopy fuel characteristics and fuel load in young black pine trees. Biotechnology and Biotechnological Equipment. 2007, 21 (2), 235-240. [CrossRef]

- Sağlam, B.; Küçük, Ö.; Bilgili, E.; Dinç Durmaz, B.; Baysal, İ. Estimating fuel biomass of some shrub species (Maquis) in Turkey. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry. 2008, 32 (4), 349-356.

- Yurtgan, M.; Baysal, İ.; Küçük, Ö. Fuel characterization and crown fuel load prediction in non-treated Calabrian pine (Pinus brutia Ten.) plantation areas. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry. 2022, 15 (6), 458-464. [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.Y. Applications of the extent analysis method on fuzzy AHP. European Journal of Operational Research. 1996, 95 (3), 649–55. [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, C.; Ertay, T.; Büyüközkan, G. A fuzzy optimization model for QFD planning process using analytic network approach. European Journal of Operational Research. 2006, 171 (2), 390–411. [CrossRef]

- Szpakowski, D.M.; Jensen, J.L.R.; Butler, D.R.; Chow, T.E. A study of the relationship between fire hazard and burn severity in Grand Teton National Park, USA. International Journal of Applied Earth Observations and Geoinformation. 2021, 98: 102305. [CrossRef]

- Paz, S.; Carmel, Y.; Jahshan, F.; Shoshany, M. Post-fire analysis of pre-fire mapping of fire-risk: A recent case study from Mt. Carmel (Israel). Forest Ecology and Management. 2010, 262, 1184–1188. [CrossRef]

- Maniatis, Y.; Athanasios Doganis, A.; Chatzigeorgiadis, M. Fire Risk Probability Mapping Using Machine Learning Tools and Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis in the GIS Environment: A Case Study in the National Park Forest Dadia-Lefkimi-Soufli, Greece. Applied Science. 2022, 12, 2938. [CrossRef]

- Finney, M.A. The challenge of quantitative risk analysis for wildland fire. Forest Ecology and Management. 2005, 211, 97–108. [CrossRef]

- Estes, B.L.; Knapp, E.E.; Skinner, C.N.; Miller, J.D.; Preisler, H.K. Factors influencing fire severity under moderate burning conditions in the Klamath Mountains, northern California, USA. Ecosphere. 2017, 8 (5):e01794. [CrossRef]

- Trucchia, A.; Meschi, G.; Fiorucci, P.; Provenzale, A.; Tonini, M.; Pernice, U. Wildfire hazard mapping in the eastern Mediterranean landscape. International Journal of Wildland Fire. 2023, 32 (3), 417–434. [CrossRef]

- Saura-Mas, S.; Paula, S.; Pausas, J.G.; Lloret, F. Fuel loading and flammability in the Mediterranean Basinwoody species with different post-fire regenerative strategies. International Journal of Wildland Fire. 2010, 19, 783–794. [CrossRef]

- Mitsopoulos, I.D.; Dimitrakopoulos, A.P. Canopy fuel characteristics and potential crown fire behavior in Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) forests. Annals of Forest Science. 2007, 64, 287–2992007. [CrossRef]

| Data | Operator | Global/Local | Extracted Information | Spatial Resolution (m) |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landsat | NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) | Global | Land Surface Temperature | 30 | https://landsat.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/ |

| Sentinel-2 | European Space Agency (ESA) | Global | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, Burn Severity Classes (by Classification) |

10,20,60 | https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/Copernicus/Sentinel-2 |

| Digital Elevation Model | Republic of Türkiye General Directorate of Mapping | Local | Slope, Elevation, Terrain Aspect | 2,50 | https://www.harita.gov.tr/ |

| Aerial Photos | Visual Interpretation | 0,25 | |||

| SPOT - Pleiades | AIRBUS | Global | Visual Interpretation | 1,5 - 0,5 | |

| Open Street Map | Open Street Map | Global | Land Use/Land Cover Classes | https://www.openstreetmap.org/ | |

| European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS) | European Commission, EU Copernicus Program | European, Middle East and North African countries (Totally 43 countries) | Active Fire Points | - | https://effis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/about-effis |

| Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS) | NASA LANCE | Global | Active Fire Points | - | https://firms.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/ |

| Copernicus Land Monitoring Service | European Environment Agency’s Copernicus Land Monitoring Service | Global, European continent | Soil Water Index(SWI) Land Use/Land Cover Classes(LU/LC) |

1000(SWI) Minimum Mapping Unit (MMU) of 25 hectares (ha)(LU/LC) |

https://land.copernicus.eu/en |

| ESA WorldCover | European Space Agency (ESA) | Global | Land Use/Land Cover Classes | 10 | https://esa-worldcover.org/en |

| Stand Structure Map | Republic of Türkiye General Directorate of Forestry | Local | Development Stage,Closure Rate, Flammable Content | - | https://www.ogm.gov.tr/en/organization/general-information |

| Meteorological Measurements | Turkish State Meteorological Service | Local | Relative Humidity, Air Temperature, Precipitation | - | https://www.mgm.gov.tr/eng/forecast-cities.aspx |

| Linguistic scale for importance | Triangular fuzzy scale | Triangular fuzzy reciprocal scale |

|---|---|---|

| Just equal | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 1, 1) |

| Equally important | (1/2, 1, 3/2) | (2/3, 1, 2) |

| Strongly more important | (1, 3/2, 2) | (1/2, 2/3, 1) |

| Very strongly more important | (3/2, 2, 5/2) | (2/5, 1/2, 2/3) |

| Absolutely more important | (2, 5/2, 3) | (1/3, 2/5, 1/2) |

| Case 1 | Case 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | 0.4490 | 0.3429 | |

| F-score | Low BurnSeverity | 0 | 0.0909091 |

| Moderate Burn Severity | 0.4 | 0.518519 | |

| High Burn Severity | 0.588235 | 0.380952 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).