Submitted:

21 December 2023

Posted:

26 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material grinding and mixing

2.2. Extrusion conditions

2.3. Chemicals and reagents

2.4. Moisture content

2.5. Sample preparation for LC-MS/MS analysis

2.6. LC-MS/MS analysis

2.7. Expansion ratio

2.8. Bulk density of extrudates

2.9. Texture analysis

2.10. Water Absorption Index (WAI) and Water Solubility Index (WSI)

2.11. Statistical analysis

2.11.1. Principal Component Analysis

2.11.2. Response surface methodology

2.11.3. Standard score

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of the LC-MS/MS method

3.2. Determination of Alternaria toxins content

3.3. Reduction of Alternaria toxins by extrusion processing

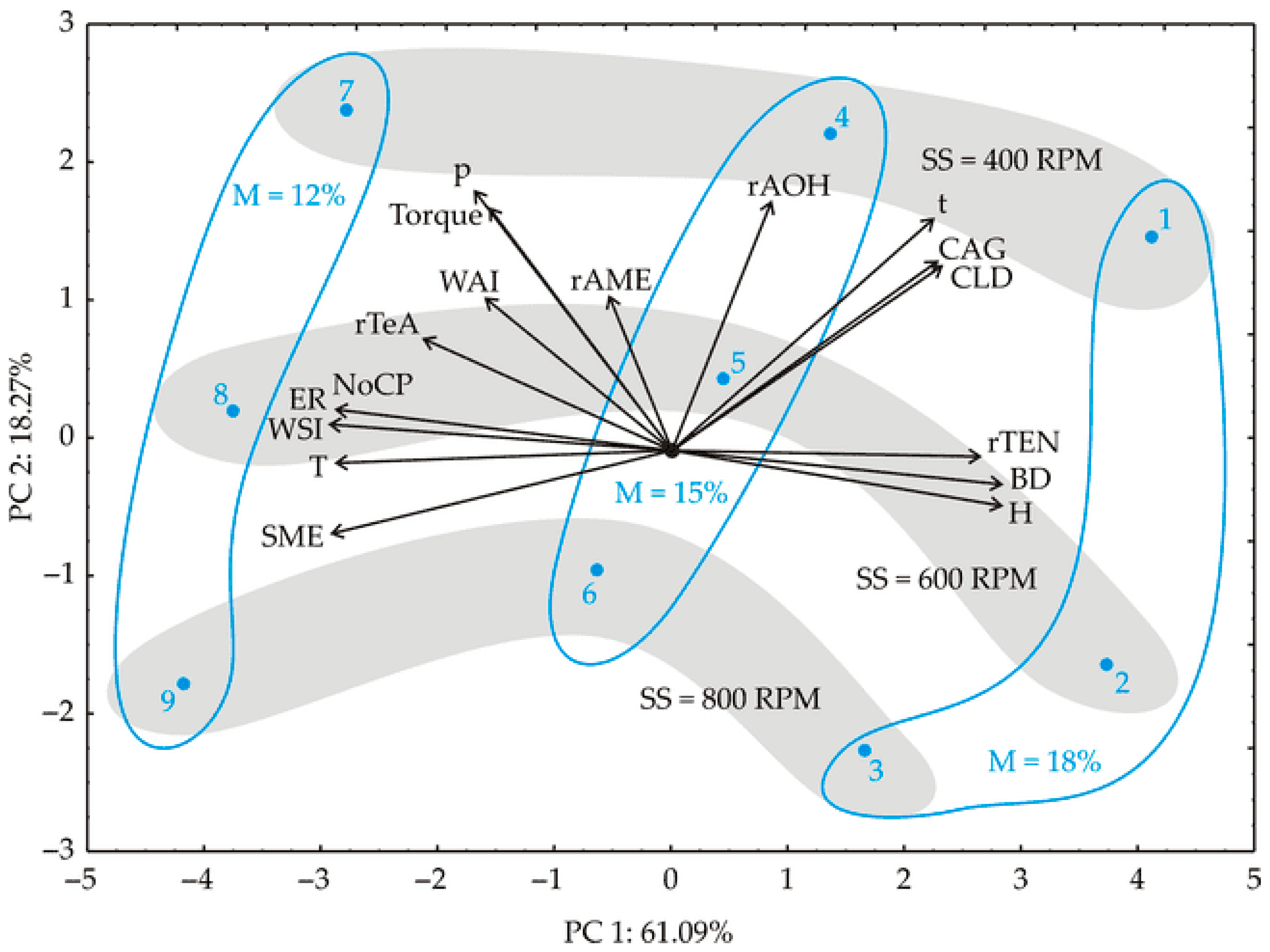

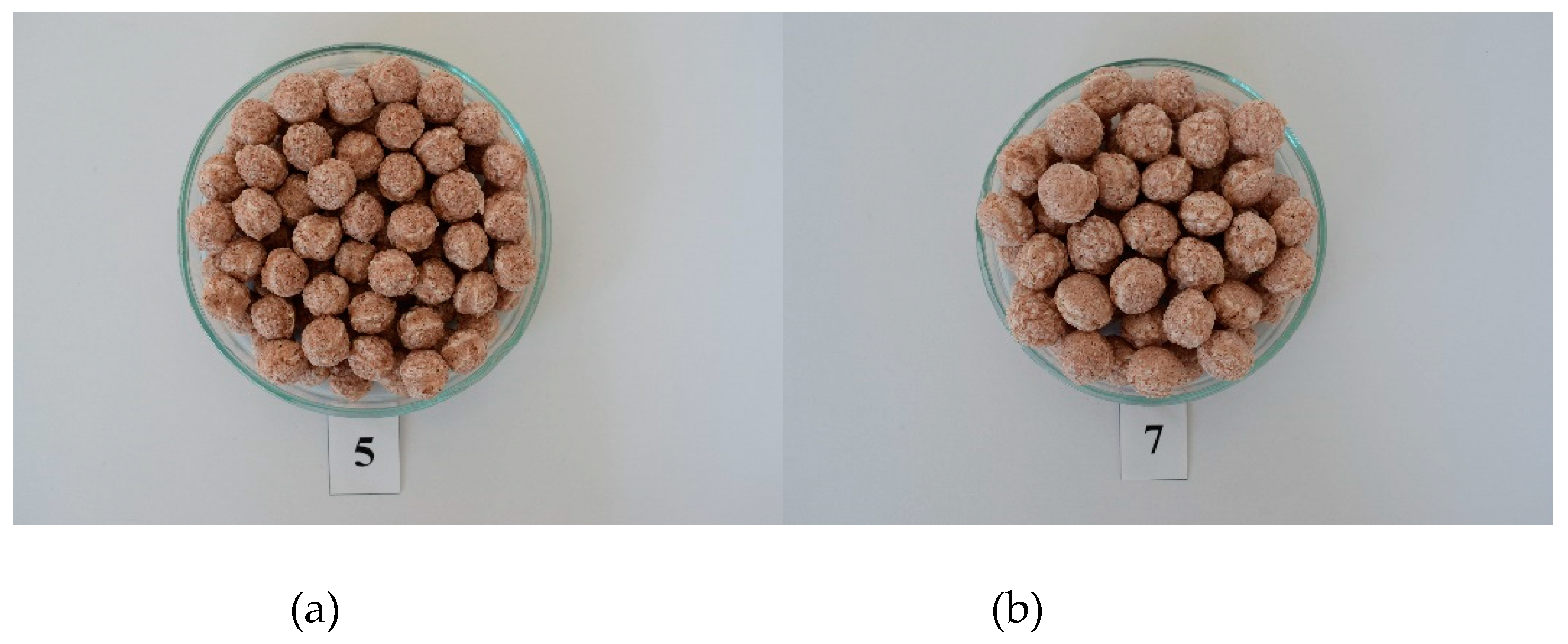

3.3.1. Principal component analysis

3.3.2. Response surface method

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Astoreca, A.; Emateguy, G.; Alconada, T. Fungal contamination and mycotoxins associated with sorghum crop: Its relevance today. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 155, 381–392. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10658-019-01797-w.

- Khoddami, A., Messina, V.; Vadabalija Venkata, K.; Farahnaky, A.; Blanchard, C. L.; Roberts, T. H. Sorghum in foods: Functionality and potential in innovative products. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. 2023, 63(9), 1170-1186. [CrossRef]

- Ciacci, C.; Maiuri, L.; Caporaso, N.; Bucci, C.; Del Giudice, L.; Massardo, D.R.; Pontieri, P.; Di Fonzo, N.; Bean, S.R.; Ioerger, B.; et al. Celiac Disease: In Vitro and In Vivo Safety and Palatability of Wheat-Free Sorghum Food Products. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 26(6), 799–805. [CrossRef]

- Pontieri, P.; Troisi, J.; Calcagnile, M.; Bean, S.R.; Tilley, M.;Aramouni, F.; Boffa, A.; Pepe, G.;Campiglia, P.; Del Giudice, F.; et al. Chemical Composition, Fatty Acid and Mineral Content of Food-Grade White, Red and Black Sorghum Varieties Grown in the Mediterranean Environment. Foods 2022, 11(3), 436. [CrossRef]

- Stefoska-Needham, A.; Beck, E.J.; Johnson, S.K.; Tapsell, L.C. Sorghum: An underutilized cereal whole grain with the potential to assist in the prevention of chronic disease. Food Rev. Int. 2015, 31, 401–437. [CrossRef]

- Serna-Saldivar, S.O. Cereal grains: Properties, processing, and nutritional attributes. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, United States, 2016, pp. 477-480.

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Scientific opinion on the risks for animal and public health related to the presence of Alternaria toxins in feed and food. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 2407–2504.

- Karlovsky, P.; Suman, M.; Berthiller, F.; De Meester, J.; Eisenbrand, G.; Perrin, I.; P. Oswald, I.; Speijers, G.; Chiodini, A.; Recker, T.; Dussort, P. Impact of food processing and detoxification treatments on mycotoxin contamination. Mycotoxin Res. 2016, 32, 179–205. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12550-016-0257-7.

- Schaarschmidt, S.; Fauhl-Hassek, C. The fate of mycotoxins during the processing of wheat for human consumption. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. F. 2018, 17(3), 556–593. [CrossRef]

- Schaarschmidt, S.; Fauhl-Hassek, C. The fate of mycotoxins during secondary food processing of maize for human consumption. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. F. 2021, 20(1), 91–148. [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Bingcan, C.; Rao, J. Occurrence and preventive strategies to control mycotoxins in cereal-based food. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. F. 2020, 19(3), 928–953. [CrossRef]

- Janić Hajnal, E.; Čolović, R.; Pezo, L.; Orčić, D.; Vukmirović, Đ.; Mastilović, J. Possibility of Alternaria toxins reduction by extrusion processing of whole wheat flour. Food chem. 2016, 213, 784-790. [CrossRef]

- Janić Hajnal, E.; Babic, J.; Pezo, L.; Banjac, V.; Čolović, R.; Kos, J.; Krulj, J.; Pavsic-Vrtač, K.; Jakovac-Strajn, B. Effects of extrusion process on Fusarium and Alternaria mycotoxins in whole grain triticale flour. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2022, 155, 112926. [CrossRef]

- Grasso, S. Extruded snacks from industrial by-products: A review. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2020, 99, 284-294. [CrossRef]

- Clark, P. M.; Behnke, K. C.; Poole, D. R. Effects of marker selection and mix time on the coefficient of variation (mix uniformity) of broiler feed. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2007, 16(3), 464–470. [CrossRef]

- Kojić, J.; Ilić, N.; Kojić, P.; Pezo, L.; Banjac, V.; Krulj, J.; Bodroža Solarov, M. Multiobjective process optimization for betaine enriched spelt flour based extrudates. J. Food Process. Eng. 2019, 42, e12942. [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 712/2009. Cereals and Cereal Products—Determination of Moisture Content—Reference Method; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Topi, D.; Tavčar-Kalcher, G.; Pavšič-Vrtač, K.; Babič J.; Jakovac-Strajn, B. Alternaria Mycotoxins in Grains from Albania: Alternariol, Alternariol Monomethyl Ether, Tenuazonic Acid and Tentoxin. World Mycotoxin J. 2019, 12(1), 89–99. [CrossRef]

- Babič, J.; Tavčar-Kalcher, G.; Celar, F. A.; Kos, K.; Knific, T.; Jakovac-Strajn, B. Occurrence of Alternaria and other toxins in cereal grains intended for animal feeding collected in Slovenia: A three-year study. Toxins 2021, 13(5), 304. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Ainsworth, P.; Tucker, G.; Marson, H. The effect of extrusion conditions on the physicochemical properties and sensory characteristics of rice-based expanded snacks. J. Food Eng. 2005, 66(3), 283–289. [CrossRef]

- Onwulata, C. I.; Smith, P. W.; Konstance, R. P.; Holsinger, V. H. Incorporation of whey products in extruded corn, potato or rice snacks. Food Res. Int. 2001, 34(8), 679–687. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. A.; Conway, H. F.; Peplinski, A. J. Gelatinization of corn grits by roll cooking, extrusion cooking and steaming. Starch-Starke, 1970, 22(4), 130-135. [CrossRef]

- STATISTICA (Data Analysis Software System) V14.0.0.15; TIBCO Stat-Soft Inc.: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2020.

- Singha, P.; Muthukumarappan, K. Effects of processing conditions on the system parameters during single screw extrusion of blend containing apple pomace. J. Food Process. Eng. 2017, 40(4), e12513. [CrossRef]

- Janić Hajnal, E.; Mastilović, J.; Bagi, F.; Orčić, D.; Budakov, D.; Kos, J.; Savić, Z. Effect of wheat milling process on the distribution of Alternaria toxins. Toxins, 2019, 11(3), 139. [CrossRef]

- EURL-MP-guidance doc_003 (version 1.2) Guidance document on performance criteria (draft 29th September, 2023). https://www.wur.nl/en/show/03.-eurlmp-guidance-document-performance-criteria-draft-29.09.2022.htm.

- Kristiawan, M.; Chaunier, L.; Sandoval, A. J.; Della Valle, G. Extrusion—Cooking and expansion. In Breakfast cereals and how they are made, 3rd ed.; Perdon, A. A.; Schonauer, S. L.; Poutanen, K., Eds.; AACC International Press, Totnes, England, 2020; pp. 141-167.

- Llopart, E. E.; Drago, S. R.; De Greef, D. M.; Torres, R. L.; González, R. J. Effects of extrusion conditions on physical and nutritional properties of extruded whole grain red sorghum (Sorghum spp). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65(1), 34–41. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Singh, B.; Singh, A.; Sharma, S.; Kidwai, M. K. Effect of extrusion processing on techno-functional properties, textural properties, antioxidant activities, in vitro nutrient digestibility and glycemic index of sorghum–chickpea-based extruded snacks. J. Texture Stud. 2023, 54(5), 706-719. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Singh, B.; Singh, A. Sorghum–mung bean combination snacks: Effect of extrusion temperature and moisture on chemical, functional, and nutritional characteristics. Legum. Sci. 2023, e186. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/leg3.186.

- Altan, A.; Mccarthy, K.L; Maskan, M. Twin-screw extrusion of barley-grape pomade blends: Extrudate characteristics and determination of optimum processing conditions. J. Food Eng. 2007, 89, 24–32. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:98063511.

- Altan, A.; Mccarthy, K.L.; Maskan, M. Evaluation of snack foods from barley–tomato pomace blends by extrusion processing. J. Food Eng. 2008, 84, 231–242. [CrossRef]

- Pardhi, S. D.; Singh, B.; Nayik, G. A.; Dar, B. N. Evaluation of functional properties of extruded snacks developed from brown rice grits by using response surface methodology. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18(1), 7-16. [CrossRef]

- Filli, K.B.; Nkama, I.; Jideani, V.A.; Abubakar, U.M. Application of response surface methodology for the evaluation of proximate composition and functionality of millet-soybean fura extrudates. Wudpecker J. Food Technol. 2013, 1(5), 74–92. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:53339595.

- Sacchetti, G.; Pittia, P.; Pinnavaia, G. G. The effect of extrusion temperature and drying-tempering on both the kinetics of hydration and the textural changes in extruded ready-to-eat breakfast cereals during soaking in semi-skimmed milk. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2005, 40(6), 655-663. [CrossRef]

- X. Meng, X.; Threinen, D.; Hansen, M.; Driedger, D. Effects of extrusion conditions on system parameters and physical properties of a chickpea flour-based snack. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 650–658. [CrossRef]

- Dar, A. H.; Sharma, H. K.; Kumar, N. Effect of extrusion temperature on the microstructure, textural and functional attributes of carrot pomace-based extrudates. J. Food Proc. Pres. 2014, 38(1), 212-222. [CrossRef]

- Wójtowicz, A.; Kolasa, A.; Mościcki, L. Influence of Buckwheat Addition on Physical Properties, Texture and Sensory Characteristics of Extruded Corn Snacks. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2013, 63(1), 239-244. [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, N. A.; Krokida, M. K. Water absorption index and water solubility index prediction for extruded food products. Int. J. Food. Prop. 2012, 15(1), 157-168. [CrossRef]

| Experimental factor | Factor’s level | ||

| (low) | (center) | (high) | |

| Screw speed (RPM) | 400 | 600 | 800 |

| Moisture content (%) | 12 | 15 | 18 |

| Analytes | Spiking level (µg/kg)* | R (%)**yufenfor whole grain red sorghum flour | R (%)**yufen for extruded product |

|---|---|---|---|

| AOH | 12.5 ̶ 100 | 90.1 | 102 |

| AME | 6.25 ̶ 50 | 95.3 | 102 |

| TeA | 6.25 ̶ 50 | 99.1 | 98.7 |

| TEN | 6.25 ̶ 50 | 100 | 97.8 |

| Analytes | Spiking level (µg/kg) | Repeatabilityyufen(n = 6) yufenRSDr (%) | Within-Laboratory reproducibilityyufen(n = 3 x 6) RSDwR (%) | Repeatabilityyufen(n = 6) yufenRSDr (%) | Within-Laboratory reproducibilityyufen(n = 3 x 6) RSDwR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole grain sorghum flour | Extruded product | ||||

| AOH | 12.5 | 9.76 | 15.7 | 11.8 | 12.9 |

| 25.0 | 9.67 | 12.4 | 9.31 | 9.96 | |

| 50.0 | 9.53 | 12.0 | 9.44 | 9.76 | |

| 100 | 8.05 | 9.16 | 8.3 | 8.5 | |

| AME | 6.25 | 10.0 | 14.4 | 10.0 | 14.4 |

| 12.5 | 9.45 | 13.1 | 9.45 | 13.1 | |

| 25.0 | 5.73 | 7.69 | 5.73 | 7.69 | |

| 50.0 | 5.11 | 6.82 | 5.11 | 6.82 | |

| TeA | 6.25 | 9.74 | 12.6 | 10.8 | 13.4 |

| 12.5 | 9.10 | 10.9 | 7.94 | 10.8 | |

| 25.0 | 7.43 | 9.80 | 7.04 | 9.20 | |

| 50.0 | 7.28 | 9.30 | 4.05 | 5.33 | |

| TEN | 6.25 | 6.98 | 10.1 | 8.53 | 12.2 |

| 12.5 | 3.55 | 4.00 | 6.16 | 10.9 | |

| 25.0 | 2.73 | 3.85 | 4.85 | 9.34 | |

| 50.0 | 2.62 | 3.50 | 3.91 | 8.33 | |

| Process responses | Product responses | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | M | SS | T | P | SME | Torque | t | rAOH | rAME | rTeA | rTEN | ER | BD | H | CLD | NoCP | CAG | WAI | WSI | Score | |

| 1 | 18 | 400 | 136 | 2.65 | 83.5 | 114 | 13 | 61.4 | 75.0 | 5.45 | 55.4 | 1.88 | 0.318 | 23.9 | 61.8 | 4.48 | 17.9 | 5.71 | 8.73 | 0.536 | |

| 2 | 18 | 600 | 144 | 1.25 | 99.6 | 88.0 | 10 | 60.6 | 71.3 | 4.55 | 56.7 | 2.02 | 0.278 | 21.6 | 60.3 | 5.70 | 17.2 | 3.82 | 11.8 | 0.302 | |

| 3 | 18 | 800 | 153 | 0.16 | 112 | 99.0 | 8 | 61.1 | 74.9 | 3.14 | 55.7 | 2.15 | 0.222 | 18.5 | 53.6 | 6.35 | 12.9 | 4.44 | 15.7 | 0.423 | |

| 6 | 15 | 400 | 159 | 4.03 | 104 | 134 | 12 | 62.1 | 77.5 | 3.56 | 52.5 | 2.68 | 0.145 | 15.4 | 61.7 | 18.4 | 16.8 | 4.72 | 20.0 | 0.613 | |

| 5 | 15 | 600 | 165 | 1.78 | 117 | 99.0 | 9.4 | 62.0 | 76.1 | 8.76 | 51.4 | 2.84 | 0.115 | 16.3 | 60.7 | 20.7 | 15.3 | 4.55 | 22.4 | 0.689 | |

| 4 | 15 | 800 | 166 | 1.28 | 130 | 114 | 8.5 | 60.9 | 80.0 | 6.89 | 54.7 | 2.97 | 0.090 | 17.6 | 55.3 | 19.6 | 12.1 | 4.69 | 26.1 | 0.619 | |

| 7 | 12 | 400 | 168 | 6.23 | 132 | 163 | 9.5 | 61.4 | 76.4 | 12.1 | 50.8 | 3.58 | 0.065 | 11.8 | 56.3 | 41.8 | 14.4 | 5.40 | 30.1 | 0.681 | |

| 8 | 12 | 600 | 176 | 4.81 | 140 | 117 | 7.7 | 60.7 | 78.2 | 7.91 | 45.7 | 3.63 | 0.055 | 9.53 | 52.8 | 56.8 | 13.6 | 5.81 | 31.1 | 0.405 | |

| 9 | 12 | 800 | 177 | 3.04 | 152 | 123 | 5.6 | 60.6 | 71.1 | 8.75 | 43.1 | 3.76 | 0.048 | 12.1 | 51.6 | 50.7 | 10.9 | 5.42 | 30.5 | 0.156 | |

| M | M2 | SS | SS2 | M x SS | Error | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| T | 1290. 7*** | 37. 6 | 181.5* | 6.7 | 16.0 | 17.8 | 0.989 |

| P | 1673.3** | 87.1 | 1184.4** | 16.2 | 12.3 | 38.7 | 0.987 |

| SME | 2799.4*** | 13.9 | 917.6*** | 0.0 | 18.1 | 6.2 | 0.998 |

| Torque | 1706.9** | 4.3 | 932.5** | 1101.4** | 146.4* | 42.9 | 0.989 |

| t | 11.2** | 2.0 | 25.6** | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.984 |

| rAOH | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.773 |

| rAME | 3.3 | 22.7 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 6.6 | 35.3 | 0.495 |

| rTeA | 40.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 25.0 | 0.632 |

| rTEN | 133.1* | 5.1 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 15.8 | 15.3 | 0.913 |

| ER | 4.0*** | 0.0 | 0.9*** | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.999 |

| BD | 0.1*** | 0.1*** | 0.1*** | 0.0 | 0.1** | 0.0 | 0.999 |

| H | 154.8** | 0.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 8.2 | 10.5 | 0.940 |

| CLD | 37.6* | 19.5* | 61.6* | 3.1 | 3.0 | 5.6 | 0.957 |

| NoCP | 2938.1*** | 130.6 | 24.1 | 34.3 | 12.6 | 46.6 | 0.985 |

| CAG | 13.6** | 0.1 | 29.4*** | 2.9* | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.990 |

| WAI | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.702 |

| WSI | 511.8*** | 4.5 | 30.6** | 0.0 | 10.8* | 2.6 | 0.995 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).