1. Introduction

All graphs considered in this paper are undirected and finite on

n vertices without loops and multiple edges. Two vertices of graph

G are adjacent if and only if they are connected by an edge. A molecular graph is a graph whose maximum degree of every vertex reaches four, see for more details reference [

1].

Graph theory serves as the foundation for studying the structures and properties of networks. Two key concepts in graph theory are symmetry groups and automorphism groups. This paper aims to investigate the relationship between these two groups, elucidating their significance and applications.

In graph theory, symmetry and the automorphism group are related concepts but have different meanings. Symmetry refers to the notion of preserving the structure or appearance of a graph under certain transformations. A graph is said to be symmetric if there exists one or more transformations that leave the graph unchanged. These transformations can include flipping or rotating the graph without altering the connections between the vertices. For example, consider a graph with a triangular shape. If you can rotate or flip the graph in such a way that it remains unchanged, then the graph possesses symmetry.

Symmetry holds significant visual importance for humans, and its evident application in architecture has prompted the authors of [

2] to investigate its role in the aesthetic judgment of residential building façades. The study aims to examine the patterns of eye movement based on the architectural expertise of the subjects. To accomplish this, two categories of façade images were created: symmetrical and asymmetrical. The experimental design enables an investigation into subject preferences, reaction times, and eye movements when evaluating the presented images. The findings indicate that the aesthetic experience of a building façade is influenced by the subjects’ level of expertise, revealing a noteworthy distinction between experts and non-experts across all conditions. Notably, non-expert subjects display a preference for symmetrical façades, aligning with their aesthetic taste. On the other hand, the automorphism group of a graph is a mathematical structure that captures all the symmetries of the graph. It is defined as the set of all permutations of the vertices that preserve the adjacency relationships in the graph. In other words, an automorphism of a graph is a permutation of the vertices that preserves the edges of the graph.

2. Automorphism Group and Symmetry Group

The automorphism group provides a systematic way of studying the symmetries of a graph and is useful in graph theory and related fields. In general, symmetry refers to the property of a graph, indicating that it can be transformed without changing its structure, while the automorphism group is the collection of all permutations of the vertices that preserve the graph’s adjacency relationships. The automorphism group represents the symmetries of the graph in a mathematical group structure.

An automorphism of the graph G = (V, E) is a bijection σ on V(G) which preserves the edge set E(G), namely e = uv is an edge if and only if σ(e) = σ(u)σ(v) is an edge of E. Here, the image of vertex u is denoted by σ(u). The set of all automorphisms of a graph G, with the operation of composition of permutations, is a permutation group on V(G) (a subgroup of the symmetric group on V(G)). We describe any subgroup H of Aut(G) as a group of automorphisms of G and refer to Aut(G) as the full automorphism group.

We say Aut(Γ) acts transitively on V(

G) if for any pair of vertices

, there is

such that

. Similarly, Aut(

G) acts transitively on

E(

G), if for two arbitrary edges

, there is an automorphism

such that

. The automorphism group plays a vital role in graph enumeration, particularly in the context of the relationship between labeled and unlabeled graphs. A labeled graph on

n vertices represents a graph whose vertex set is {1, …,

n}, while an unlabelled graph represents an isomorphism class of

n-element graphs. The number of labeling for a given unlabelled graph

G on

n vertices is determined by the formula

n!/|Aut(

G)|, where

n! represents the factorial of

n and |Aut(

G)| denotes the size of the automorphism group of

G, see [

3].

In a graph, labeling is defined by a bijective function

g from the set {1, …,

n} to the vertex set V(

G). There are

n! possible functions of this kind, and two functions,

g1 and

g2, define the same labeled graph if and only if there exists an automorphism

h such that

g2(

i) =

g1(

i)

h for all

i in {1, …,

n}.

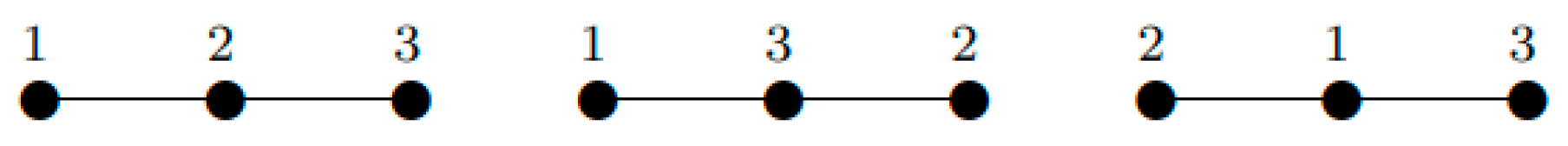

Figure 1 illustrates this concept with three labeling of the path graph of length 2, where the automorphism group has an order of 2, see [

3], for more details.

The two problems mentioned are closely intertwined, as the first problem can be polynomially reduced to the second problem. Let’s consider the scenario where we are given two graphs,

G and

H. By applying complementation, if necessary, we can assume that both

G and

H are connected. Now, suppose that we can identify generating permutations for Aut(

K), where

K represents the disjoint union of

G and

H. In this case,

G and

H are isomorphic if and only if one of the generators exchanges the two connected components, [

3].

Conversely, if we possess the ability to solve the graph isomorphism problem, we can at least verify whether a graph has a non-trivial automorphism. This can be accomplished by attaching distinctive "gadgets" to each vertex of the graph and examining whether any pair of resulting graphs are isomorphic. However, determining the generators for the automorphism group may prove to be more challenging [

3].

2.1. Symmetry Group

We begin by providing a thorough definition of symmetry groups in the context of graph theory. We explore how symmetry groups capture the symmetries present in a graph, and we discuss the fundamental properties of symmetry groups. The symmetry of an object refers to the rigid motion (that is, a motion that preserves distance and size) of a plane that does not alter the object [

8].

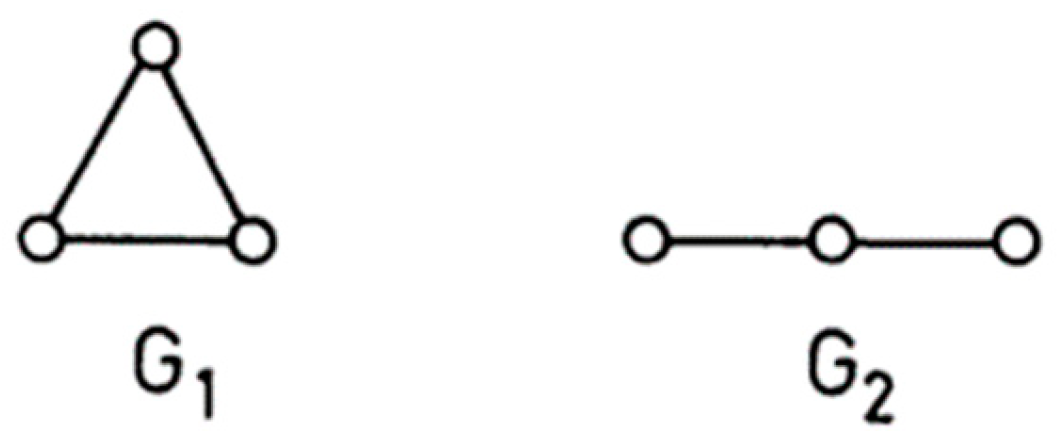

Symmetry plays a crucial role in characterizing molecules, relying on both their molecular geometry and the constituent atoms. The manifestation of a specific molecular geometry or topology is referred to as the materialization of a molecule. The delicate interplay between molecular geometry, symmetry and topology is best illustrated by the simple example of triatomic molecules. These can have two different topologies-cyclic and acyclic. The corresponding molecular graphs are G1 and G2.

Figure 2.

Two connected graphs of order 3.

Figure 2.

Two connected graphs of order 3.

The symmetry group can be defined as the group consisting of all transformations that leave an object unchanged. This group, denoted by Sym(X), includes only those isometries that map the object X back to itself while also preserving any other patterns present. We say that X is invariant under such a mapping and that the mapping itself is a symmetry of X. The term "full symmetry group" is sometimes used to specifically include orientation-reversing isometries, such as reflections, glide reflections, and improper rotations, as long as they map a specific object X to itself. This contrasts with the "proper symmetry group," which only includes orientation-preserving symmetries such as translations, rotations, and compositions of these transformations. An object is considered chiral if the full symmetry group is identical to its proper symmetry group. For symmetry groups that have a common fixed point, such as finite groups or bounded figures, they can be represented as sub-groups of the orthogonal group O(n) by choosing the origin as the fixed point. This means that any transformation in the symmetry group leaves the origin unchanged. The proper symmetry group, which only includes orientation-preserving symmetries, becomes a subgroup of the special orthogonal group SO(n) and is called the rotation group of the figure. This is because all transformations in the rotation group are rotations around the fixed point. In a discrete symmetry group, the images of a fixed point under the action of the group do not accumulate at a limiting point. Each orbit, which represents the set of all such images, is itself discrete. It is noteworthy that all finite symmetry groups belong to this class of groups. Discrete symmetry groups can be categorized into three types:

Finite point groups: These groups include rotations, reflections, inversions, and rotoinversions. They are the finite subgroups of the orthogonal group O(n).

Infinite lattice groups: These groups consist solely of translations.

Infinite space groups: These groups contain elements from both the finite point groups and infinite lattice groups. They may also include additional transformations such as screw displacements and glide reflections.

Continuous symmetry groups, known as Lie groups, encompass rotations of arbitrarily small angles or translations of arbitrarily small distances. An example of a continuous symmetry group is O3, which is the symmetry group of a sphere. The symmetry groups of Euclidean objects can be classified as subgroups of the Euclidean group

E(

n), which represents the isometry group of

Rn, see [

54]. Two geometric figures share the same symmetry type when their symmetry groups are conjugate subgroups of the Euclidean group.

3. Relationship between Symmetry Groups and Automorphism Groups

In this section, we establish the relationship between symmetry groups and automorphism groups. We demonstrate that the symmetry group of a graph is a subgroup of its automorphism group. The symmetry group consists of all the permutations of vertices that preserve the graph’s structure, including rotations, reflections, and combinations thereof. The automorphism group, on the other hand, consists of all the permutations of vertices that preserve the adjacency relationships in the graph. Since the symmetry group captures all the symmetries of the graph, it is a subset or subgroup of the larger automorphism group, which captures all the possible permutations preserving the graph’s adjacency relationships.

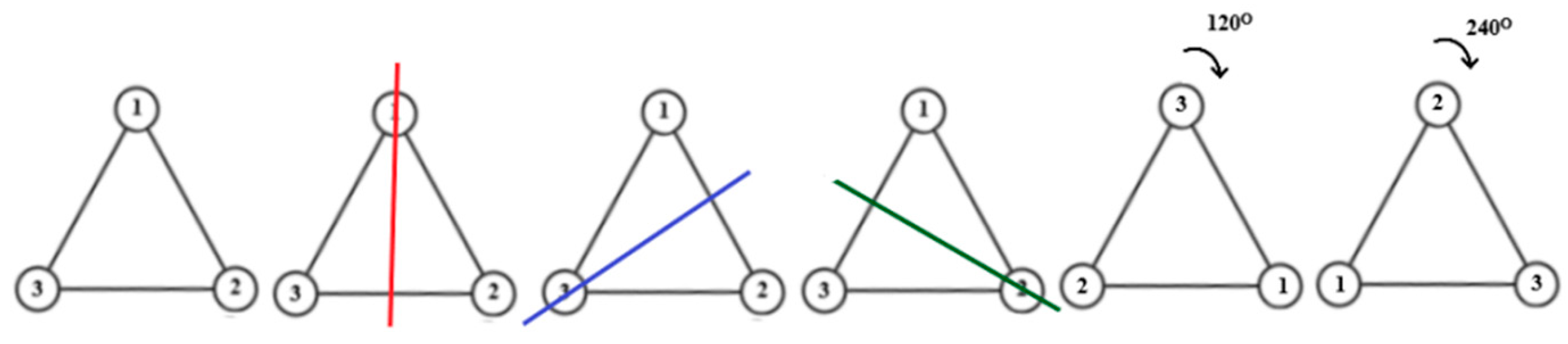

For example, consider the cycle graph

C3 in

Figure 3. The line of symmetry colored by red is denoted by permutation (2,3). Hence, the permutations corresponding to blue and green lines are respectively denoted by (1, 2) and (1, 3). A clockwise rotation equal to 120

◦ around the middle point of

C3 is denoted by (1, 2, 3) and equal to 240

◦ by (1, 3, 2). All of these permutations preserve the vertex adjacency and thus are automorphism. Note that a 360

◦ rotation preserves the figure unchanged and we denote this permutation by (). Hence, the automorphism group of

C3 has 6 elements which is Aut(

C3) = {(), (1, 2), (1, 3), (2, 3), (1, 2, 3), (1, 3, 2)}.

Here are a few examples to illustrate the relationship between symmetry groups and automorphism groups in different types of graphs:

The symmetry group of a complete graph is the symmetric group Sn, which consists of all possible permutations of the vertices.

The symmetry group of a cycle graph consists of rotations by multiples of 2π/n radians. It is isomorphic to the cyclic group Cn, which includes rotations by multiples of k(2π/n) radians, where k is an integer from 0 to n-1.

The symmetry group of a square grid graph includes rotations by multiples of 90 degrees and reflections along horizontal, vertical, and diagonal axes. In other words, it is isomorphic to the dihedral group D4, also known as the symmetry group of a square. The dihedral group D4 consists of eight elements, representing rotations and reflections that preserve the square’s structure. In the context of the square grid graph, the automorphism group captures the symmetries of the graph that preserve the grid structure, including rotations by 90, 180, and 270 degrees, as well as reflections along horizontal, vertical, and diagonal axes. Therefore, the automorphism group of the square grid graph is isomorphic to the dihedral group D4.

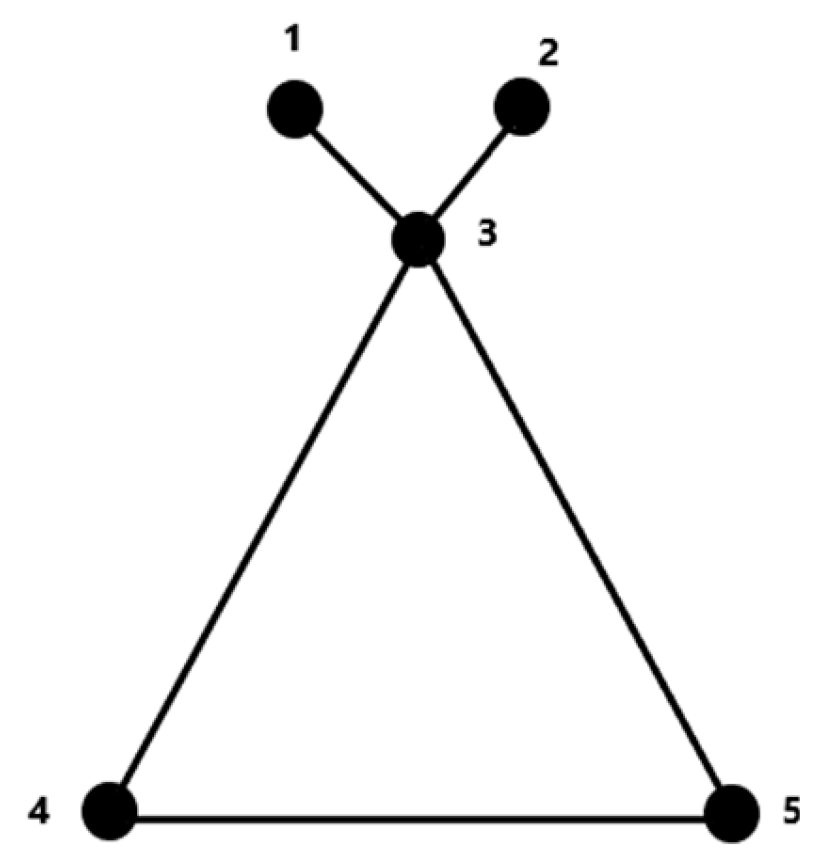

Now consider the graph

G depicted in

Figure 4. The symmetry group of this figure as a rigid graph is isomorphic with the cyclic group Z

2 of order two with group elements {(), (1,2)(4,5)} while the automorphism group is isomorphic with Klein group

with group elements {(), (1,2)(4,5), (1,2), (4,5)}.

These examples demonstrate that the symmetry group is a subgroup of the automorphism group. The automorphism group captures a broader set of permutations that preserve adjacency relationships, while the symmetry group represents a subset of those permutations that specifically preserve the graph’s symmetrical properties.

4. Main Results

In the realm of Abstract Algebra, a fundamental concept revolves around the combination of sets with operations on their elements and the subsequent study of their resulting behavior. This approach enables us to comprehend a set more comprehensively by considering its elements within the context of their interactions. For instance, we may be interested in understanding the behavior of the set of integers modulo m under addition, or how the elements of an abstract set S behave under a defined set of permutations acting upon them. Both of these examples embody the concept of a group.

In a group, we explore the properties and structures that emerge when combining elements from a given set with a particular operation. This study helps us analyze various aspects, such as closure (the result of the operation remaining within the set), associativity (the order in which operations are performed not affecting the result), the existence of an identity element (an element that leaves other elements unchanged when combined), and the existence of inverses (elements that, when combined with others, yield the identity element).

By studying groups, we gain insight into the interplay between sets and their operations, uncovering important properties and relationships that shed light on the underlying structure of mathematical systems.

Definition 4.1. In a group, denoted as S, there is an operation ◦ such that for all elements a and b in S, the result of applying the operation to a and b is an element c that also belongs to S. Additionally, for all elements a, b, and c in S, the equality a ◦ (b ◦ c) equals (a ◦ b) ◦ c holds. Furthermore, there exists an element e in S that satisfies the property a ◦ e = e ◦ a = a for all elements a in S. Lastly, for every element a in S, there exists another element b in S such that a ◦ b equals b ◦ a equals e.

To further explore the concept of groups, it is crucial to formalize the ideas of group homomorphisms, isomorphisms, and automorphisms. This will be achieved by utilizing the definitions presented by Steinberger [

12].

A group homomorphism is a function that preserves the operation between two groups. More precisely, let (G, *) and (H, •) be two groups. A function f: G → H is a group homomorphism if it satisfies the condition f(x * y) = f(x) • f(y) for all x, y ∈ G. This means that the homomorphism maps the group operation in G to the group operation in H, preserving the structure.

An isomorphism, on the other hand, is a special type of group homomorphism that establishes a one-to-one correspondence between two groups, preserving their structural properties. Specifically, an isomorphism is a bijective group homomorphism. If there exists an isomorphism between two groups G and H, they are said to be isomorphic, denoted as G ≅ H.

Lastly, an automorphism refers to an isomorphism from a group to itself. In other words, an automorphism is a bijective mapping that preserves the group operation and structure of a single group. The set of all automorphisms of a group G forms the automorphism group of G, denoted as Aut(G).

By formally defining group homomorphisms, isomorphisms, and automorphisms, we establish a solid framework for studying the relationships and mappings between groups, allowing us to analyze their structural properties and uncover deeper insights into the nature of these mathematical objects.

Definition 4.2. A function f: G → G0 is called a homomorphism if it satisfies f(x ◦ y) = f(x) ◦ f(y) for all x, y in G.

Definition 4.3. A function that is both one-to-one and onto when acting as a homomorphism is referred to as an isomorphism.

Definition 4.4. An automorphism of a group G is an isomorphism from G to itself.

The smallest graph, excluding the one-vertex graph, with a trivial automorphism group is depicted in

Figure 5 (not provided in this text-based format).

However, it is important to note that small graphs should not be solely relied upon as a reliable indicator in this context. Erdӧs and Rényi [

13] demonstrated that:

Theorem 4.1. The automorphism group of the complete graph on n vertices Aut(Kn) is isomorphic to Sn.

Theorem 4.2.

[13] Almost all graphs have no non-trivial automorphisms.

It has been established that as the number of vertices (n) approaches infinity, the proportion of graphs with a non-trivial automorphism tends to zero. This observation holds for both labeled and unlabeled graphs. As mentioned in the introduction, this theorem implies that almost all graphs can be labeled in n! different ways. Consequently, the number of unlabelled graphs on n vertices can be approximated as . (It is evident that there are precisely labeled graphs on the vertex set {1, …, n} since we have the choice of connecting or not connecting each pair of vertices by an edge.) Notably, there are now reliable estimates available for the error term in the asymptotic expansion. This error term originates from graphs with non-trivial symmetries, and these estimates serve to quantify the aforementioned theorem.

Theorem 4.3.

[13] This theorem asserts that the automorphism group of a complete graph with any single edge deleted, as portrayed in

Figure 6, is isomorphic to S

2 × S

n−2.This result can be extended to classify the automorphism groups of all graphs by repeatedly removing edges until the complete graph is attained. However, this method would be impractical due to the existence of numerous non-isomorphic ways to remove a fixed number of edges from the complete graph for small values of m. For instance, for m = 2, there are two distinct ways to remove two edges, but for m = 3, there are already several possibilities: we can remove three non-adjacent edges, two adjacent edges and one non-adjacent edge, three adjacent edges that are mutually adjacent, or three adjacent edges such that two are mutually non-adjacent. As the number of cases increases rapidly with m, exhaustively considering all possibilities becomes increasingly impractical.

On the other hand, the computer-based perception of graph automorphism symmetry poses a significant computational burden. Specifically, determining the automorphism group involves evaluating whether any vertex permutation of the given graph preserves the adjacency matrix (which represents the graph’s connectivity). To construct the automorphism group, the algorithm must verify whether a vertex permutation maintains the adjacency matrix’s invariance. In general, there are

n! possible vertex permutations for a graph comprising

n vertices. Verifying each permutation requires performing two matrix multiplications, resulting in a total of 2

n³ multiplication operations. Consequently, the overall complexity of the problem involves 2

n³

n! multiplication operations. For instance, a graph with 10 vertices entails a staggering 7,257,600,000 multiplication operations, see [

14].

While various techniques exist for partitioning the vertices of a graph based on automorphism properties, the generation of the actual automorphism group remains a relatively unexplored area with limited methods available. Automorphism partitioning involves dividing the vertices of a graph into equivalence classes based on their automorphic relationships. This process helps identify subsets of vertices that exhibit similar structural properties and symmetries. Several algorithms and heuristics have been proposed to efficiently perform automorphism partitioning, see [

15,

16].

However, when it comes to generating the automorphism group itself, there are comparatively few established methods. The generation of the automorphism group entails determining all the possible symmetries and preserving transformations of the graph, providing insights into its inherent structural symmetries.

A permutation matrix is a square matrix that represents a permutation of the rows or columns of an identity matrix. In other words, it is a matrix that results from rearranging the rows or columns of an identity matrix according to a specific permutation. Formally, let P be an n×n permutation matrix. Each row and column of P contains exactly one entry of 1, and all other entries are 0. Moreover, in each row and column, there is only one entry of 1. The permutation matrix P corresponds to a permutation σ of the numbers 1 to n. If we denote the entry in the ith row and jth column of P as P[i,j], then P[i,j] = 1 if and only if σ(i) = j. Otherwise, P[i,j] = 0. Essentially, a permutation matrix represents a reordering or rearrangement of the rows or columns of an identity matrix to achieve a specific permutation of elements.

In the context of the automorphism group of a graph, a given permutation is considered to be in the automorphism group if its corresponding permutation matrix, denoted as P, satisfies the equation A = PTAP. Here, a represents the adjacency matrix of the graph. When dealing with a graph consisting of n vertices, there are n! permutation matrices to consider. Therefore, a brute force approach for verifying if the above equation is satisfied would require performing n! checks. This equation involves two n × n matrix multiplications. To validate the automorphism group, the algorithm would need to compute these matrix multiplications for each permutation matrix. Hence, the overall computational complexity of the brute force approach for verifying the automorphism group involves performing 2n³ operations for each permutation matrix, resulting in a total of n! × 2n³ multiplication operations. However, it is important to note that this calculation only accounts for the multiplication operations and does not consider the CPU times required for generating the permutation matrix P. The process of generating the permutation matrix may introduce additional computational overhead, which should be taken into account when evaluating the overall computational cost.

5. Automorphism Group of Polyhedral Graphs

Polyhedral graphs are extensively utilized mathematical structures that effectively capture the connectivity of three-dimensional polyhedra. The concept of the symmetry group is instrumental in comprehending the symmetries embedded within these graphs. The automorphism group of a polyhedral graph encompasses the entire set of symmetries or transformations that uphold its structural integrity. In a polyhedral graph, vertices correspond to the corners or vertices of the associated polyhedron, while edges represent its edges or sides. The automorphism group aptly captures the symmetries present in the underlying polyhedron, encompassing diverse transformations like rotations, reflections, and their combinations. These transformations meticulously preserve the incidence relationships between the vertices and edges of the graph. The specific automorphism group of a polyhedral graph is contingent upon the symmetries exhibited by the corresponding polyhedron. Notably, a regular polyhedron such as a cube or an icosahedron possesses a larger automorphism group, comprising a greater number of transformations compared to an irregular polyhedron. The study of automorphism groups in polyhedral graphs holds significant importance in comprehending the symmetries and structural intricacies of polyhedra, while also finding practical applications in fields like crystallography, chemistry, and computer graphics. It is well-known that the symmetry group and automorphism group of regular polyhedral graphs are the same because regular polyhedra possess a high degree of symmetry, and the symmetries of the graph are precisely captured by the automorphisms of the graph. Regular polyhedra are highly symmetric three-dimensional objects that have identical faces, edges, and vertices. For example, a cube has six faces, each of which is a square, and the edges and vertices are symmetrically arranged. When we represent a regular polyhedron as a graph, with vertices representing the corners of the polyhedron and edges representing the connections between the corners, the symmetries of the polyhedron are reflected as symmetries of the graph. Ghorbani et al., in a series of papers, computed the symmetry group of several classes of polyhedral graphs, see (17,18). In [

19] the authors introduced the notation (

t,s,p,h)-polyhedral graphs to represent cubic polyhedral graphs with specific face compositions. These graphs consist of

t triangles,

s quadrangles,

p pentagons, and

h hexagons as their only faces, excluding any other types of faces. The authors further demonstrated that the order of the symmetry group of such graphs is a divisor of 240. In an exact phrase, they showed that in a (4,5,6)-fullerene

F.

Case 1: If the number of quadrangles in a graph is zero, it is classified as a classical fullerene with an automorphism group that is a divisor of 120. These fullerenes are described in detail in reference [

18]

.

Cases 2-6: In contrast, when the number of quadrangles is 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5, respectively, the graph has 10, 8, 6, 4, or 2 pentagons.

Case 7: When the number of quadrangles is six, the graph does not have any pentagons, and it is still a fullerene with an automorphism group that divides 48. These graphs are studied in reference [

20].

In this survey paper, we provide an overview of the research on the symmetry group of polyhedral graphs. We discuss various aspects, including the definitions and properties of symmetry groups, the relationship between symmetry groups and polyhedral symmetries, and the classification of polyhedral graphs based on their symmetry groups. Furthermore, we present applications of symmetry groups in fields such as crystallography, chemistry, and computer graphics. This survey serves as a comprehensive reference for researchers and practitioners interested in the symmetry group theory of polyhedral graphs.

In [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25], Fowler et al. demonstrated that out of all possible point groups, only 28 can actually be realized by fullerene structures. These 28 point groups represent all the possible symmetry configurations that can be achieved by a fullerene structure. It’s worth noting that the most common fullerene,

C60, belongs to the point group

Ih, which possesses icosahedral symmetry.

The pentagons in fullerene structures appear in specific orbits, each with a size equal to the ratio of the point group of fullerene to the site group. In this context, a site refers to a point that remains unchanged under certain operations of the space group. These operations can be organized into a group known as the site group.

Each point within the fullerene structure can be considered as a site, and at minimum, it possesses the trivial site group

E. In practical terms, the site is often defined as an occupied atomic site [

22]. For a pentagon on a sphere, the site group is restricted to

H, represented by

C5v,

C5,

Cs, or

C1 symmetries [

22]. If a fullerene possesses a fivefold axis, it necessitates a pentagon center at each end of the axis. However, if the fullerene has an axis of order 2, 3, 4, or 6, it does not feature a pentagon center along that particular axis.

Result 5. 1. Let F be a dodecahedron. The order of Aut(F) in action on the set of pentagonal faces is 120.

Proof. We assign labels to all twelve pentagons as P1, P2, ..., P12. Let’s arbitrarily select P1 as a starting point. There are twelve potential images for P1. Next, we examine a pentagon adjacent to P1, denoted as P2. It becomes evident that there are five options for the placement of P2. Continuing further, for a pentagon P3 adjacent to both P1 and P2, there are two possible permutations. Lastly, the fourth pentagon has only one viable choice. Thus, the proof is concluded.

In [

18], the author investigated that for a fullerene graph

F, the order of its automorphism group Aut(

F) is a divisor of 120. Ghorbani et al. also obtained similar results in (25,26) by proving that if

F is a (3,6)-polyhedral graph or a (4,6)-polyhedral graph, then the order of its automorphism group Aut(

F) is a divisor of 24 or 48, respectively.

They also identified the order of automorphism groups for all (3,4,6), (3,5,6), and (4,5,6)-polyhedral graphs. In other words, they proved the following results.

Theorem 5.1. Let F be both isolated (4,6), (5,6), and (4,5,6)-polyhedral graph, G be a (3,4,6)-polyhedral graph and L be a (3,5,6)-polyhedral graph. Then Aut(F) is a {2, 3, 5}-group and both Aut(G) and Aut(L) are {2, 3}-group. Moreover, |Aut(F)| divides 24 × 3 × 5, |Aut(G)| divides 24 × 3 and |Aut(L)| divides 23 × 3.

In [

27] the authors investigated the permissible point-group symmetries of cubic polyhedra, where the face sizes are limited to 3, 4, 5, and 6. They determined the polyhedron with the minimum number of vertices for each group and face signature (

p3,

p4,

p5).

General methods for generating infinite families of polyhedra with specific face signatures and point-group symmetries from a single prototype have already been established. One such method is the Goldberg-Coxeter construction, which involves taking a cubic polyhedron and specifying two integers, k and l. Applying this construction yields a new cubic polyhedron with

k2 +

kl +

l2 times as many vertices as the original, while maintaining the same rotational symmetry and the face signature [

28]. Another construction technique that preserves the same face signature is to divide the faces into two hemispheres using a simple zigzag pattern [

29] and inserting a cylindrical tube composed of layers of hexagons. Both of these construction approaches have been utilized in deriving electron counting rules for fullerenes [

22]. Thus, by starting with minimal examples, it becomes possible to generate an entire series of polyhedrals, see also (30,31).

Theorem 5.2. For the biface cubic polyhedra described by the triple (p

3, p

4, p

5), the possible point groups and vertex counts of minimal examples are [

32]:

| (p3, p4, p5) |

possible point groups |

vertex counts of minimal |

(p3, p4, p5) |

possible point groups |

vertex counts of minimal |

| (4, 0, 0) |

D2

|

24 |

(0, 0, 12) |

C1 |

36 |

| D2h

|

16 |

C2

|

32 |

| D2d

|

20 |

Ci

|

56 |

| T |

28 |

Cs

|

34 |

| Td

|

4 |

C3

|

40 |

| (0, 6, 0) |

C1 |

40 |

D2

|

28 |

| Cs

|

34 |

S4

|

44 |

| C2

|

26 |

C2v

|

30 |

| Ci

|

140 |

C2h

|

48 |

| C2v

|

22 |

D3

|

32 |

| C2h |

44 |

S6

|

68 |

| D2

|

24 |

C3v

|

34 |

| D3

|

20 |

C3h

|

62 |

| D2d

|

16 |

D2h

|

40 |

| D2h

|

20 |

D2d

|

36 |

| D3d

|

20 |

D5

|

60 |

| D3h

|

14 |

D6

|

72 |

| D6

|

84 |

D3h

|

26 |

| D6h

|

12 |

D3d

|

32 |

| O |

56 |

T |

44 |

| Oh

|

8 |

D5h

|

30 |

| (0, 0, 12) |

Td

|

28 |

D5d

|

40 |

| Th |

92 |

D6h

|

36 |

| I |

140 |

D6d

|

24 |

| Ih |

20 |

- |

- |

The outcomes of our ongoing investigation into the final 16 triplets are compiled in.

Theorem 5.3.

[27] identifies the possible point groups and vertex counts of minimal for cubic polyhedra with at least two face sizes chosen from {3, 4, 5} and no face larger than 6, based on their triple representation (p

3, p

4, p

5). The results are as follows:

| (p3, p4, p5) |

possible point groups |

vertex counts of minimal |

(p3, p4, p5) |

possible point groups |

vertex counts of minimal |

| (3, 1, 1) |

C1

|

20 |

(2, 3, 0) |

C1

|

22 |

| Cs

|

12 |

Cs

|

26 |

| (3, 0, 3) |

C1

|

18 |

C2

|

18 |

| Cs

|

14 |

C2v

|

10 |

| C3 |

22 |

D3

|

42 |

| C3v

|

10 |

D3h

|

6 |

| C3h

|

20 |

(2, 2, 2) |

C1

|

16 |

| (2, 1, 4) |

C1

|

16 |

Cs |

14 |

| Cs

|

14 |

Ci

|

56 |

| C2

|

14 |

C2

|

10 |

| C2v

|

12 |

C2v

|

8 |

| (2, 0, 6) |

C1

|

24 |

C2h

|

16 |

| Cs

|

22 |

(1, 3, 3) |

C1

|

14 |

| Ci

|

40 |

Cs

|

12 |

| C2

|

16 |

C3

|

28 |

| C2v

|

18 |

C3v

|

10 |

| C2h

|

20 |

(1, 2, 5) |

C1

|

18 |

| D3

|

36 |

Cs

|

14 |

| D3d

|

12 |

(1, 0, 9) |

C1

|

30 |

| D3h

|

18 |

Cs

|

26 |

| (1, 1, 7) |

C1

|

20 |

C3

|

34 |

| Cs

|

18 |

C3v

|

22 |

| (0, 5, 2) |

C1

|

20 |

(0, 4, 4) |

C1

|

18 |

| Cs

|

20 |

Cs

|

18 |

| C2

|

18 |

Ci

|

48 |

| C2v

|

14 |

C2

|

16 |

| D5

|

70 |

C2v

|

14 |

| D5h

|

10 |

C2h

|

32 |

| (0, 3, 6) |

C1 |

20 |

D2

|

20 |

| Cs

|

20 |

D2h

|

16 |

| C2

|

18 |

D2d

|

12 |

| C2v

|

18 |

S4

|

36 |

| C3

|

26 |

(0, 2, 8) |

C1 |

24 |

| C3v

|

16 |

Cs

|

22 |

| C3h

|

44 |

Ci

|

40 |

| D3

|

26 |

C2

|

20 |

| D3h

|

14 |

C2v

|

18 |

| (1, 4, 1) |

C1

|

18 |

C2h

|

28 |

| Cs

|

12 |

D4

|

48 |

| (0, 1, 10) |

C1

|

28 |

D4h

|

24 |

| Cs

|

24 |

D4d

|

16 |

| C2

|

26 |

D2

|

28 |

| C2v

|

22 |

D2h

|

24 |

| - |

- |

- |

D2d

|

40 |

| - |

- |

- |

S4

|

136 |

5.1. Determining the Automorphism Group of Small Polyhedral Graphs: A Computational Approach

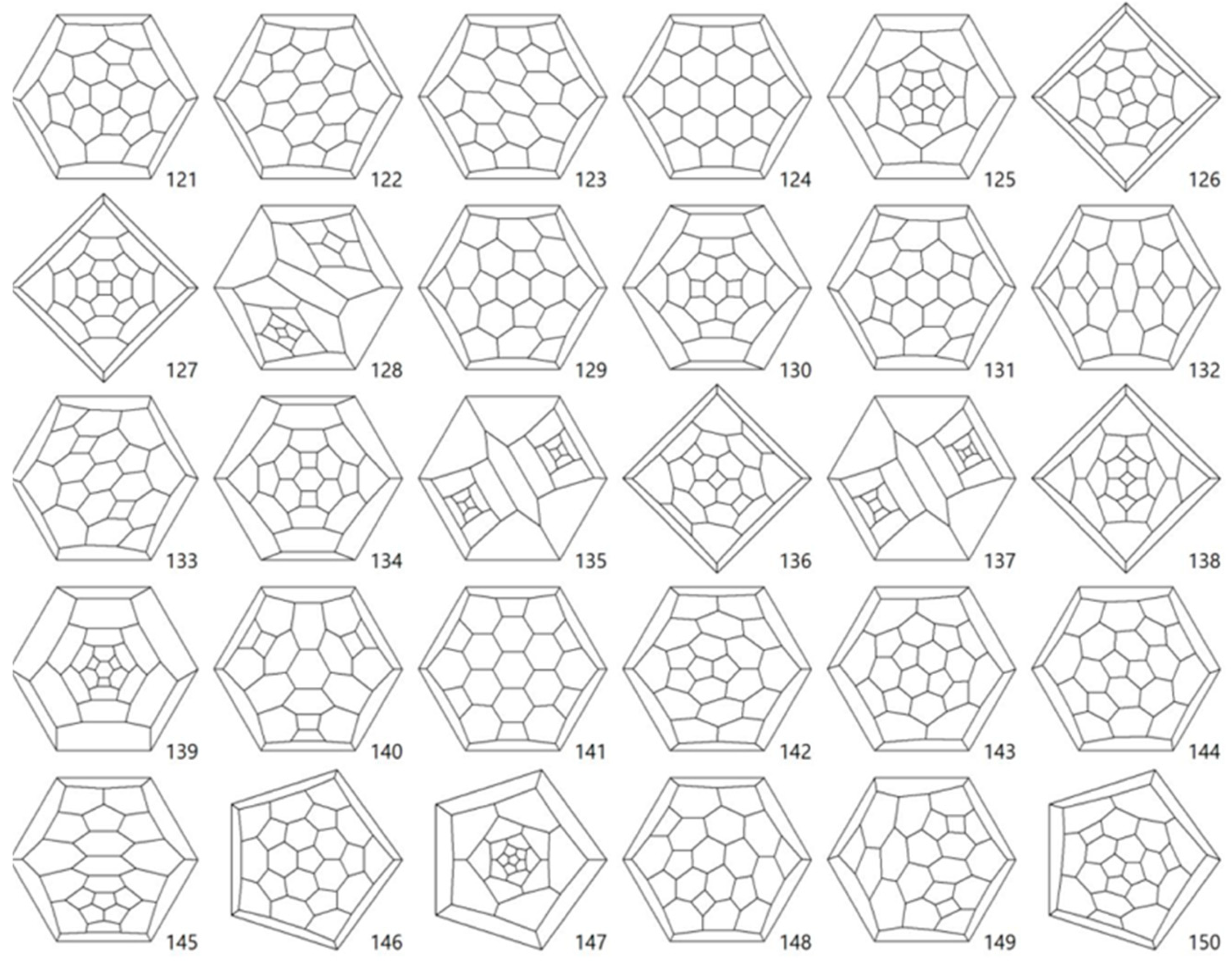

Here, we compute the symmetry/automorphism group of some (4,5,6) polyhedral graphs especially for fullerenes as depicted in

Figure 7.

Lemma 5.1. (Cauchy—Frobenius Lemma) Let G be a group acting on a set Ω. The number of orbits of G in Ω is given by:

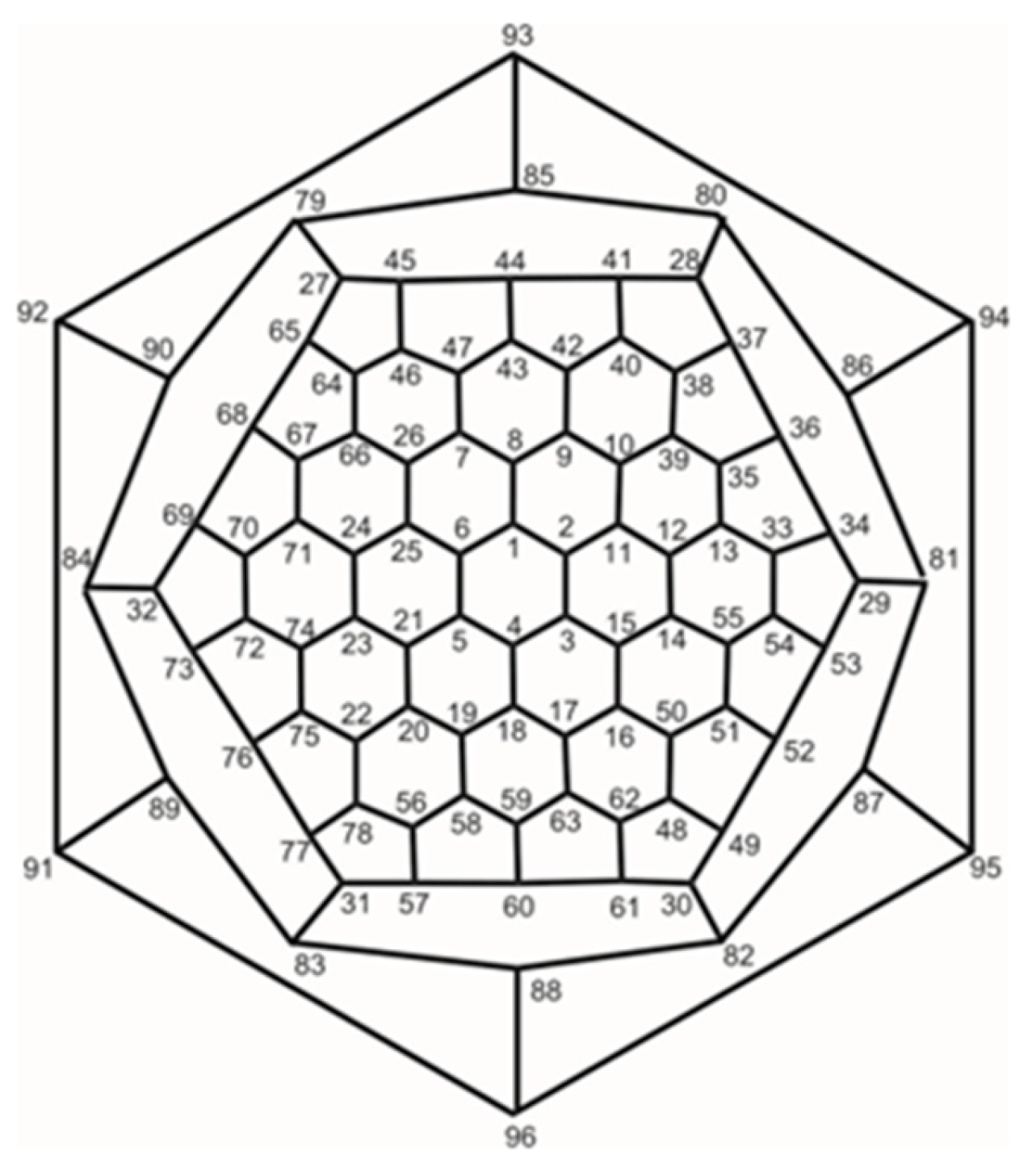

Example 5.1

[32]. Consider now the fullerene graph

F96 depicted in

Figure 8. Let us consider a rotation α that occurs around an axis passing through the midpoints of the front and back faces with an angle of 60°. Additionally, let us consider an axis symmetry element

that fixes vertices {1, 4, 8, 18, 43, 44, 59, 60, 85, 88, 92, 95}. It can be proven that

and

. Consequently, we can conclude that the symmetry group

of this fullerene graph is isomorphic with a dihedral group of order 96.

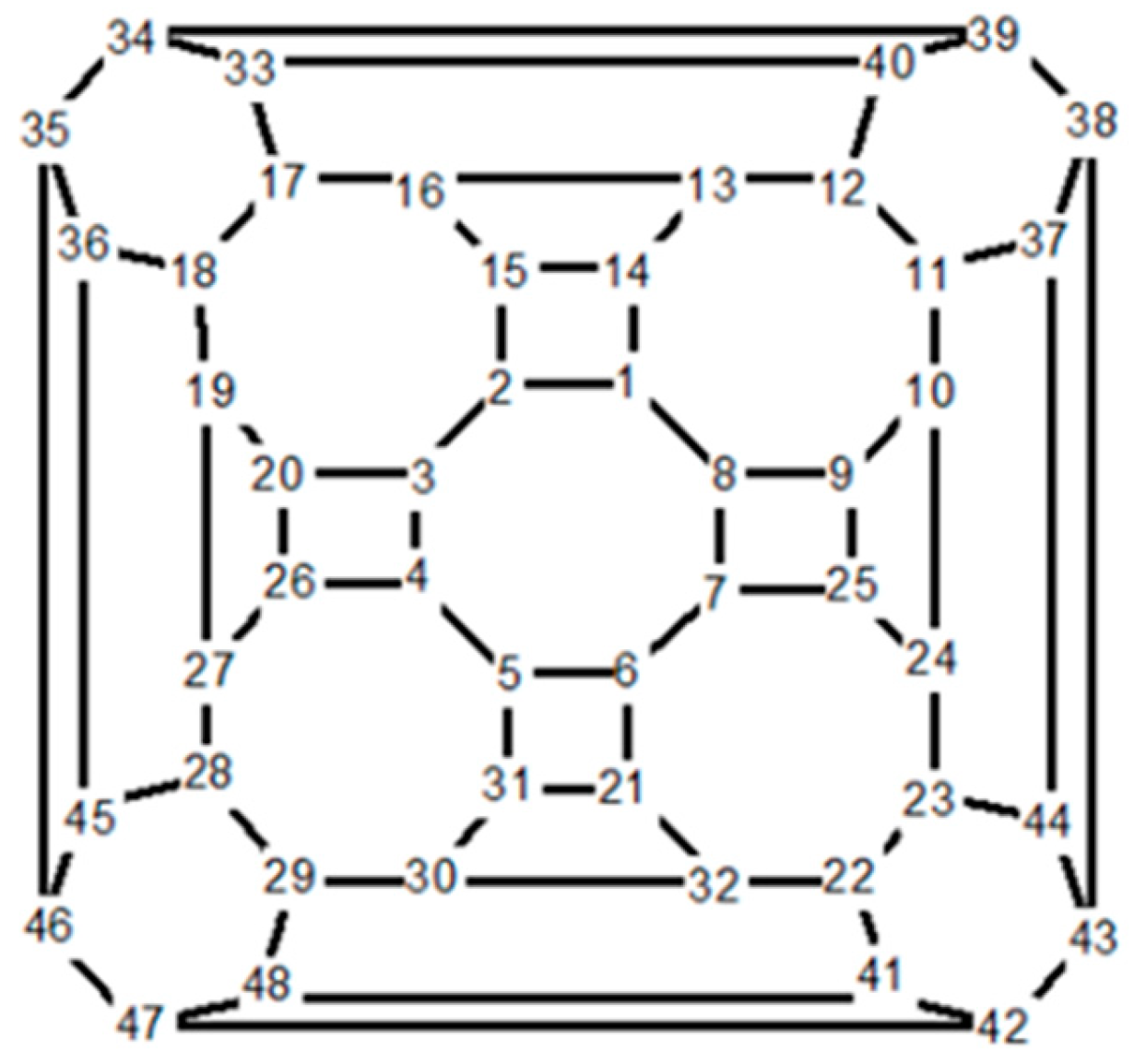

Example 5.2

[33]. Here, consider the fullerene

F48 depicted in

Figure 9. In reference (20, 26) it is proved that there are two automorphisms

and

which satisfy in the relation of the dihedral group

. Hence we conclude that the automorphism group of polyhedral graph F

48 is isomorphic with a dihedral group of order eight.

6. Applications of Automorphism Group in Real Life

The concept of automorphism groups finds various applications in real-life scenarios. Some notable applications include:

Crystallography: Crystallography is a scientific discipline that studies the atomic and molecular structures of crystals. Crystals are solid materials whose atoms or molecules are arranged in a highly ordered, repeating pattern, extending in three dimensions. They exhibit various physical properties, such as transparency, hardness, and unique optical characteristics, which are closely related to their underlying atomic arrangement. Automorphism groups play a fundamental role in crystallography, the study of the atomic and molecular structures of crystals. Understanding the symmetries present in crystal structures is crucial for characterizing their physical properties. Automorphism groups help identify and classify symmetries in crystal lattices, aiding in the analysis and prediction of crystallographic patterns and properties. For example, reference (35,36) gives examples of the use of the apparatus of group theory in research on crystallography, quantum mechanics, and elementary particle physics. In particular, in these studies matrix groups and representations of unitary groups are actively used.

Chemistry: the application of automorphism groups in chemical graph theory allows chemists to study the symmetry properties of molecules. By analyzing the automorphism group of a molecular graph, chemists gain insights into the spatial arrangement, symmetry elements, chemical reactivity, chirality, and molecular properties. This knowledge contributes to a deeper understanding of molecular behavior, aiding in the design of new compounds, drugs, and materials. In other words, in chemical graph theory, automorphism groups are utilized to study the symmetry properties of molecules. A molecular graph is a representation of a molecule where atoms are represented as vertices, and chemical bonds between atoms are represented as edges. The automorphism group of a molecular graph consists of all the symmetries or transformations of the graph that preserve its structural characteristics. By analyzing the automorphism group of a molecular graph, chemists can gain insights into the spatial arrangement and symmetry elements present in the molecule, see [

37,

38,

39,

40].

Network Analysis: Automorphism groups are used in network analysis to identify symmetries and regular patterns in complex networks. By exploring the automorphism group of a network, researchers can detect repeated substructures, identify equivalent nodes or edges, and understand the overall network organization. This knowledge aids in various network-related applications, including community detection, data clustering, and network visualization, see (37,38).

Computer Graphics: Automorphism groups find applications in computer graphics and computer-aided design. By understanding the symmetries of geometric models and graphical objects, automorphism groups can be utilized for efficient rendering, modeling, and animation. They enable the creation of visually appealing and symmetrical designs and aid in shape manipulation and deformation techniques, see, (41,42).

Coding Theory: Automorphism groups have applications in coding theory, a field that deals with the design and analysis of error-correcting codes. By studying the automorphism group of a code, researchers can identify symmetries that preserve code properties and aid in code optimization. This knowledge helps in constructing efficient codes with desirable symmetry properties, see [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48] for more details.

Symmetry Detection: Automorphism groups are utilized in computer vision and pattern recognition for symmetry detection in images and patterns. By analyzing the automorphism group of an object or image, algorithms can identify and quantify the presence of symmetries, leading to applications such as object recognition, shape analysis, and image compression, see [

49].

Symmetry is a pervasive phenomenon presenting itself in all forms and scales, from galaxies to microscopic biological structures, in nature and man-made environments. Much of one’s understanding of the world is based on the perception and recognition of recurring patterns that are generalized by the mathematical concept of symmetries [

50,

51,

52]. Humans and animals have an innate ability to perceive and take advantage of symmetry in everyday life (53–56) while harnessing this powerful insight for machine intelligence remains a challenging task for computer scientists. These applications highlight the significance of automorphism groups in various domains, contributing to advancements in scientific research, technology development, and practical applications in real-life scenarios.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper has provided a comprehensive exploration of the relationship between symmetry groups and automorphism groups in graph theory. We have elucidated their definitions, properties, and applications. Understanding this relationship enhances our comprehension of the symmetries and structures inherent in graphs, enabling us to leverage these concepts in practical applications. Future research can build upon this foundation to further investigate the intricacies and implications of symmetry groups and automorphism groups in graph theory.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Todeschini, R.; Consonni, V. Handbook of Molecular Descriptors; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Azemati, H.; Jam, F.; Ghorbani, M.; Dehmer, M.; Ebrahimpour, R.; Ghanbaran, A.; Emmert-Streib, F. The Role of Symmetry in the Aesthetics of Residential Building Façades Using Cognitive Science Methods. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, P.J.; Mary, Q. Automorphisms of graphs. In Topics in algebraic graph theory; Beineke, L.W., Wilson, R.J., Eds.; Cambridge Mathematical Library, Cambridge University Press, 2005; Volume 102, pp. 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, C.W. Euclidean Geometry and Transformations; Courier Dover Publications: New York, NY, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DeTemple, D.W.; Long, C.T.; Millman, R.S. Mathematical Reasoning for Elementary School Teachers, 7th ed.; Pearson Education, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nezhad-Sadeghi, N. The Effect of Using GeoGebra Software on Teaching Transformational Geometry Concepts to 7th and 8th Grade Students in Public Schools. Master’s thesis, Shahid Chamran University, Ahvaz, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Najd, S. The effect of education with a cultural-social approach on the mathematics academic performance of second-grade middle school students in the topic of symmetry. Master’s thesis, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tapp, K. Symmetry, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani, M. Symmetry for prospective elementary teachers. 18th Iranian Mathematics Education Conference, Damghan, Iran, 1-2 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bahamet, S.; Farhoudi Moghaddam, P. Mathematics Teacher Guide for Middle School; Goethe Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Moravcová, V.; Robová, J.; Hromadová, J.; Halas, Z. Student’s understanding of axial and central symmetry. J. Effic. Responsib. Educ. Sci. 2021, 14, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberger, M. Algebra; Boston: PWS, 1994.

- Erdös, P.; Rényi, A. Asymmetric graphs. Acta Math. Acad. Sci. Hungar. 1963, 14, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, K. Computational techniques for the automorphism groups of graphs. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. 1994, 34, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.I.; Ellzey Jr, M.L. A technique for determining the symmetry properties of molecular graphs. J. Comput. Chem. 1983, 4, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Balasubramanian, K.; Munk, M.E. Computer-assisted graph-theoretical construction of C-13 NMR signal and intensity patterns. J. Magn. Reson. 1990, 87, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Hakimi-Nezhaad, M. An algebraic study of non-classical fullerenes. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostructures 2016, 24, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutnar, K.; Marušic, D.; Janezic, D. Fullerenes via their automorphism groups. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2010, 63, 267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani, M.; Dehmer, M.; Rahmani, S.; Rajabi-Parsa, M. A survey on symmetry group of polyhedral graphs. Symmetry 2020, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Songhori, M. On the automorphism group of polyhedral graphs. App. Math. Comput. 2016, 282, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.W.; Manolopoulos, D.E.; Redmond, D.B.; Ryan, R. Possible symmetries of fullerenes structures. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1993, 202, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.W.; Manolopoulos, D.E. An Atlas of Fullerenes; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, P.W. How unusual is C60, Magic numbers for carbon clusters. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1986, 131, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.W.; Steer, J.I. The leapfrog principle-a rule for electron counts of carbon clusters. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1987, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Songhori, M.; Ashrafi, A.R.; Graovać, A. Symmetry group of (3,6)-fullerenes. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostructures 2015, 23, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Songhori, M. Polyhedral graphs via their automorphism groups. App. Math. Comput. 2018, 321, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deza, M.; Sikirić, M.D.; Fowler, P.W. The symmetries of cubic polyhedral graphs with face size no larger than 6. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2009, 61, 589–602. [Google Scholar]

- Dutour, M.; Deza, M. Goldberg-Coxeter construction for 3- and 4-valent plane graphs. Elec. J. Comb. 2004, 11, R202004–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deza, M.; Dutour, M. Zigzag structure of simple two-faced polyhedra. Comb. Probab. Comput. 2005, 14, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deza, M.; Dutour Sikirić, M. Geometry of Chemical Graphs: Polycycles and Twofaced Maps; Cambridge University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Deza, M.; Dutour, M.; Fowler, P. Zigzags, railroads and knots in fullerenes. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004, 44, 1282–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkmann, G.; Delgado-Friedrichs, O.; Dress, A.; Harmuth, T. CaGe - a virtual environment for studying some special classes of large molecules. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 1997, 36, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani, M.; Hakimi-Nezhaad, M.; Abbasi-Barfaraz, F. An algebraic approach to the Wiener number. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2017, 53, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Hakimi-Nezhaad, M.; Dehmer, M.; Li, X. Analysis of the Graovac–Pisanski index of some polyhedral graphs based on their symmetry group. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- Senashov, V.I. Applications of group theory in crystallography. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2022, 1230, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wipke, W.T.; Dyott, T.M. Stereochemically unique naming algorithm. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 4834–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herndon, W.C. Canonical Labelling and Linear Notation for Chemical Graphs. In Chemical Applications of Topology and Graph Theory; King, R.B., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1983; pp. 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, A.T.; Mekenyan, O.; Bonchev, D. Unique description of chemical structures based on hierarchically ordered extended connectivities (HOC procedures). I. Algorithms for finding graph orbits and canonical numbering of atoms. J. Comput. Chem. 1985, 6, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, H.L. Generation of unique machine description for chemical structures. J. Chem. Doc. 1965, 5, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razinger, M. Extended connectivity in chemical graphs. Theor. Chim. Acta 1982, 61, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, C.A.; Munk, M.E. Computer perception of topological symmetry. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1977, 17, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, C.A.; Munk, M.E. An approach to the assignment of canonical tables and topological symmetry perception. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1979, 19, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiselhart, M.; Elkelesh, A.; Ebada, M.; Cammerer, S.; Brink, S.T. Automorphism ensemble decoding of Reed–Muller codes. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2021, 69, 6424–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolte, N. Rekursive codes mit der Plotkin-Konstruktion und ihre Decodierung (Recursive codes with the Plotkin construction and their decoding). PhD Dissertation, Technische Universitat Darmstadt, 2002.

-

http://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/1.

- Hehn, T.; Huber, J.B.; Laendner, S.; Milenkovic, O. Multiple-Bases Belief-Propagation for Decoding of Short Block Codes. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Nice, France, June 2007; pp. 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, E.; Hager, C.; Pfister, H.D. (2018). Decoding Reed-Muller codes using minimum-weight parity checks. In IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory - Proceedings, 2018-June: 1296-1300. [CrossRef]

- Nachmani, E.; Marciano, E.; Lugosch, L.; Gross, W.J.; Burshtein, D.; Be’ery, Y. Deep learning methods for improved decoding of linear codes. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2018, 12, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchberger, A.; Hager, C.; Pfister, H.D.; Schmalen, L.; Amat, A.G. Pruning neural belief propagation decoders. IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory 2020, 2962–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hel-Or, H.; Kaplan, C.S.; Van Gool, L. Computational symmetry in computer vision and computer graphics. Found. Trends Comput. Graph. Vis. 2009, 5, 1–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyl, H. Symmetry; Princeton University Press, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Coxeter, H.; Moser, W. Generators and relations for discrete groups, 4th ed.; Springer, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.; Burgiel, H.; Goodman-Strauss, C. The symmetries of things; AK Peters, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D.W. On growth and form; Cambridge University Press, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurfa, M.; Eichmann, B.; Menzel, R. Symmetry perception in an insect. Nature 1996, 382, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, I.; Gumbert, A.; Hempel de Ibarra, N.; Kunze, J.; Giurfa, M. Symmetry is in the eye of the ‘beholder’: innate preference for bilateral symmetry in flower-naïve bumblebees. Naturwissenschaften 2004, 91, 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, C. (Ed.). Human symmetry perception and its computational analysis, VSP, 1996.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).