1. Introduction

Taeniasis and cysticercosis are human diseases caused by the pork tapeworm, Taenia solium. Cysticercosis in humans is the infection of the larval stage following the ingestion of pork tapeworm eggs (Galán-Puchades, 2016; Ito et al., 2015; Mata et al., 1996). Taeniasis is asymptomatic although carriers may suffer abdominal discomfort and weight loss(Okello & Thomas, 2017). The pork tapeworm larva in the human central nervous system causes neurocysticercosis(NCC), a serious medical condition in humans (Mahanty & Garcia, 2010). It is a brain disease that presents as epilepsy, chronic headache, visual disorders, dizziness, or nausea; the clinical manifestation depends on the immune response of the individual; the location of cysts, and their size and number (Del Brutto, 2014; Montano et al., 2005; Yancey et al., 2005).

Worldwide pork tapeworm infections prevail in poor subsistence farming communities in low and middle-income countries (Mwape et al., 2013; Rojas et al., 2019; Shukla et al., 2010). Taeniasis has been reported in Europe to range from 0.05-0.27% and ranges from 0-17.25% in Africa, Asia, and Latin America (Okello & Thomas, 2017). Neurocysticercosis causes up to 30 percent of all cases of acquired epilepsy in endemic localities (Mahanty & Garcia, 2010; Torgerson et al., 2015; Torgerson & Macpherson, 2011) which causes about 61 to 212 deaths annually in East African countries (Minani et al., 2022; Trevisan et al., 2017; Lozano et al., 2012).

Generally, pork tapeworm diseases in Africa have been estimated to be 0-13.9 % for taeniasis and 0.68-34.5% for cysticercosis and reported in 29 countries(Braae et al., 2015; Gulelat et al., 2022; Okello & Thomas, 2017). About 0.95-3.08 million people are estimated to suffer from symptomatic NCC in sub-Saharan Africa (Winkler, 2012). In Eastern Africa, human T. solium cysticercosis is endemic with pooled prevalence ranging from 14-20 % (Gulelat et al., 2022). The disease is endemic in Tanzania, with an average seroprevalence of about 17% and the disease accounted for 212 deaths and 17,853 NCC incident cases for the year 2012 (Mwang’onde et al., 2012; Mwanjali et al., 2013; Mwita et al., 2013; Trevisan et al., 2017).

Human T. solium cysticercosis is associated with community practices and poor sanitation. Open defecation, unsafe water sourcing, and consumption of uninspected and undercooked infected pork increase the risk of human infections. (Mwang’onde et al., 2012; Kabululu et al., 2020; Mwape et al., 2013; Ngowi et al., 2004,; Pondja et al., 2010). Studies have shown clean and safe water reduce infection in both human and pig, furthermore the clean practices of feeding pigs reduce the risks of infecting pigs (Kabululu et al., 2023). The underuse of pit latrines and improperly constructed toilets give access of pigs to toilets thus easily accessing faces (Kabululu et al., 2020). The pig-free-ranging practices is another risk factor for pork tapeworm transmission in the endemic communities (Mwanjali et al., 2013; Ngowi et al., 2004).

The prophylaxis treatment is among the means of reducing the transmission of intestinal and tissue worms. The current treatment guideline for pork tapeworm diseases gives directives for treatment in humans (Chemotherapy, 2021). The prophylaxis and vaccine in pigs is currently in research work not practiced in communities but the result showed the high efficacy of combined TSOL18 and oxfendazole (Kabululu et al., 2020). The current prophylactic treatment using praziquantel and albendazole for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths is targeting school children only (World Bank, 2018a).

Although pork tapeworm is listed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the number one cause of food-borne diseases (Torgerson et al., 2015), it is not considered a priority disease in Tanzania, thus receiving less attention in terms of surveillance and interventions (CDC, 2017). The current nationwide intervention among school children using praziquantel and albendazole targets schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths but not pork tapeworm (Resources, 2003; World Bank, 2018a). We conducted this study to determine the effect of anthelminthic treatment among school children on the transmission of pork tapeworm in communities of Mbulu district in Tanzania.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted in Mbulu District of northern Tanzania in March-April 2021. The district is among six districts of Manyara region in Tanzania located at latitude 3˚45′ and 4˚ S and longitude 35˚20′ and 36˚E at an altitude ranging from 1,000–2,400 meters above mean sea level. The district has an area of 3,800 square kilometres and a population of 320,279; among these, 161,548 are males and 158,731 are females. About 48,976 are in urban and 271,303 are in rural areas (National Bureau of Statistics & Office of Chief Government Stastician, 2013). Crop farming and livestock keeping are the main economic activities for 96% of the population (DPLO, 2015). The district administers anthelmintic to pre and school children annually as part of the national deworming program using praziquantel and albendazole targeting schistosomiasis, and soil-transmitted helminths which started in 2002 in Tanzania (Resources, 2003; World Bank, 2018a). Primary school Children in all villages in the district including those selected for study received the intervention conducted by Neglected Tropical Diseases Control program Tanzania collaborating with local governments. The study area was selected as a result of the high prevalence and cysticercosis burden of pork tapeworm from previous studies of 16.3% prevalence (Mwang’onde et al., 2012, 2018)

2.2. Study Design

This was a community-based cross-sectional study conducted in Mbulu district Northern Tanzania from March to April 2020.

2.3. Sampling and Sample Size

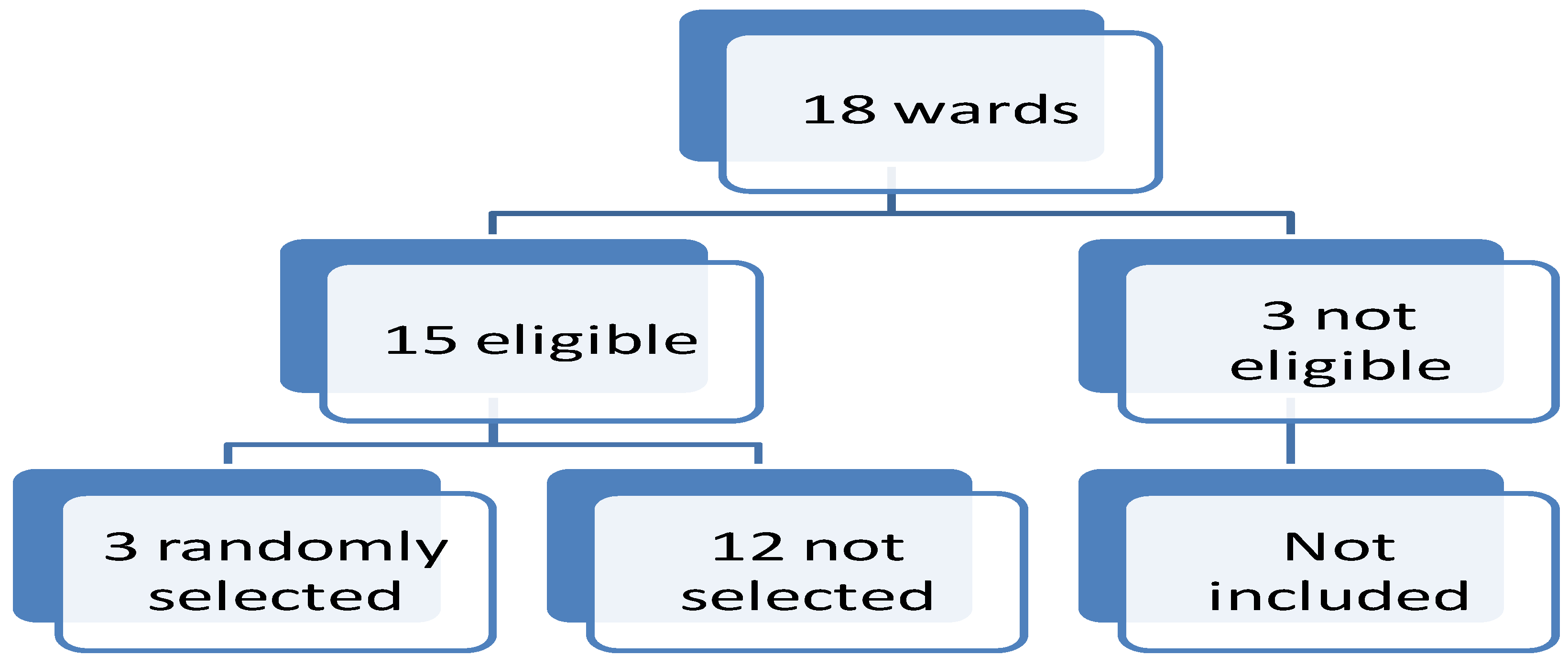

Three wards namely Maghang, Dinamu and Bashay were randomly selected from 15 pig-keeping wards, the inclusion criteria were pig keeping communities; three wards were excluded out of 18 wards. From each of the three wards, one village was randomly selected and included in this study (

Figure 1). The households were conveniently sampled based on the presence of pigs and history of keeping pigs and the consent of the household leader. The consented adult and assented minor participants from households aged five years and above were recruited for the study, the study included five years because they are enrolled in pre-and primary school and are targeted by the deworming program. The study villages selected were Maghang Juu, Diyomati and Harsha. The sample size was computed using Fisher’s formula (Rotondi & Donner, 2012) Z= 1.96, p= 16.3%, d= 0.0418 estimating a sample size of 300 participants (Mwang’onde

et al., 2012).

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Questionnaire Method

The household leaders were asked about risk factors related to cysticercosis on source of water and participation in previous deworming programs. Observations and responses on the availability of pit latrines, water sources, and pigs keeping were recorded. The data were collected electronically using tablets installed with koBocollect software. The information recorded among study participants was on education, occupation, and participation in deworming programs by swallowing anthelmintic in the last deworming program.

2.4.2. Sample Collection

Five millilitres of blood was drawn from each participant including the head of households who consented and assented children in the household and transferred into a plain vacutainer tube and stored in a cool box packed with ice cubes. The blood samples were centrifuged at 1500 rounds per 15 minutes and the supernatant was transferred into cryovials and stored in a -200 freezer until laboratory tests were done.

2.4.3. ELISA Method

The detection of cysticercosis was done using ApDia Ag ELISA (Reference number 650505; apDia, Raadsherenstraat 3 2300 Turnhout, Belgium) for the determination of viable metacestode of Taenia species (ApDia, 2004). ELISA cut-off value for antigen was calculated, a cut-off value = mean Optical Density (OD) negative × 2). A positive reaction corresponded to the antigen index above or equal to 1.3 while the antigen index value below or equal to 0.8 was negative. A grey zone between 0.8 and 1.3 was considered doubtful and was retested.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS software, version 20. Continuous variables are summarized by the measure of central tendency and their respective dispersion. Categorical variables were summarized by proportions and frequencies and compared by chi-square test. Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval were used and a p-value of less than 5% was considered significant.

2.6. Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the Medical Research Coordinating Committee of the National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania (Reference No. NIMR/HQ/R.8c/Vol.1/1612). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects’ ≥18 years, and consent was obtained from parents or guardians of the respective individuals below 18 years old following the subject’s assent.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

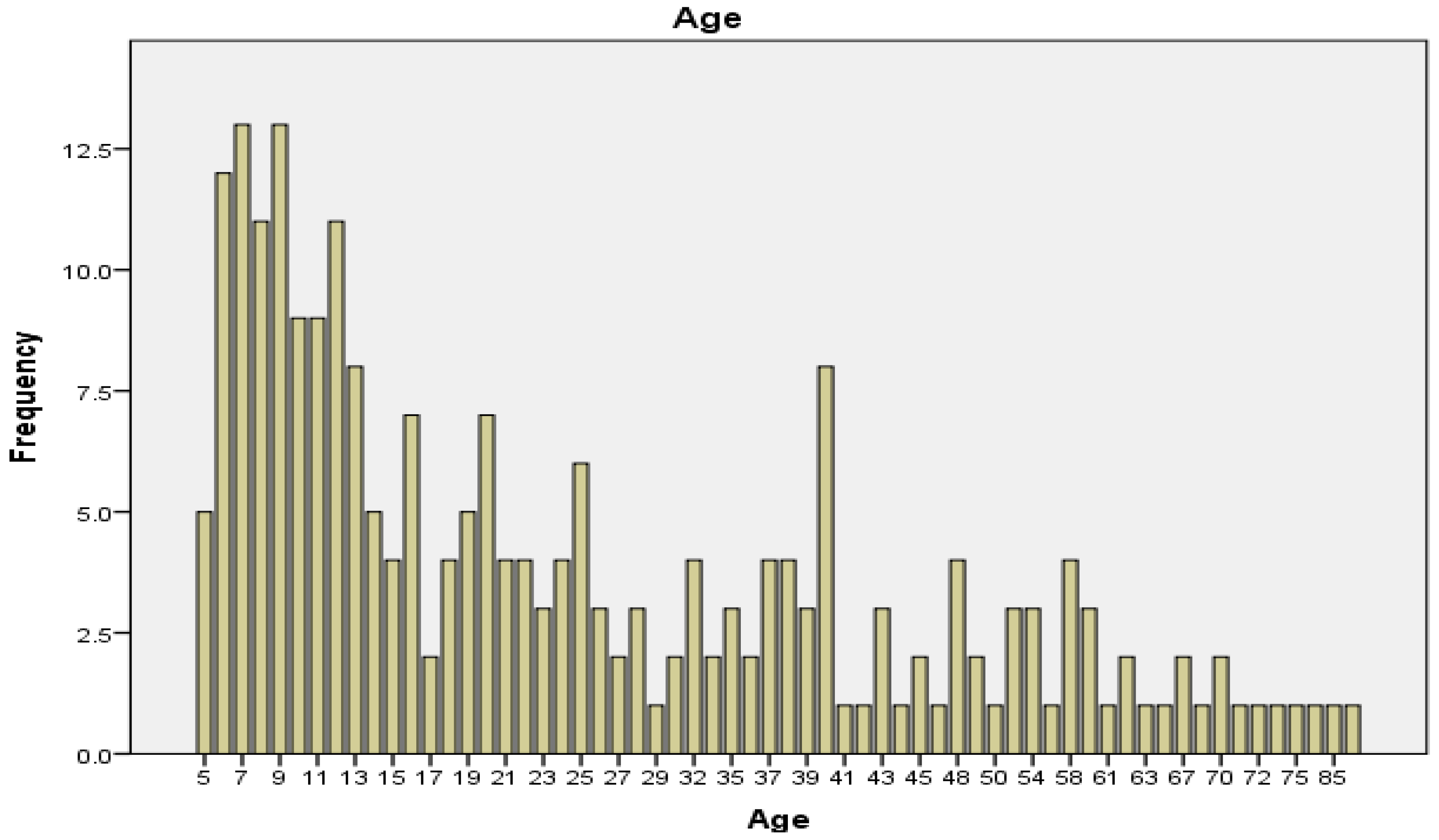

A total of 300 individuals were involved in the study. The median age was 19 years and the mode was 7, with a maximum of 89 and a minimum of 5 years. Female and male participants were almost equally represented (

Figure 2 and

Table 1).

3.2. Prevalence of Cysticercosis

The overall prevalence of human

T.solium cysticercosis was 23(7.67%), among these 12(8.27%) were males and 11(7.09%) were females. The prevalence was higher 6(11.76%) among those aged 26-35 years and ±45 years. There was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence by age group, sex, and occupation (

Table 2). Among the 300, 82(27.3%) had received anthelminthic during the previous year. Among 23(7.67%) who tested positive by antigen test 5(21.7%) received anthelmintic. The likelihood of infection among anthelminthic users and non-users was low by 28% [0.72 (0.26-2.01)], but the protection was not statistically significant.

Risk Factors

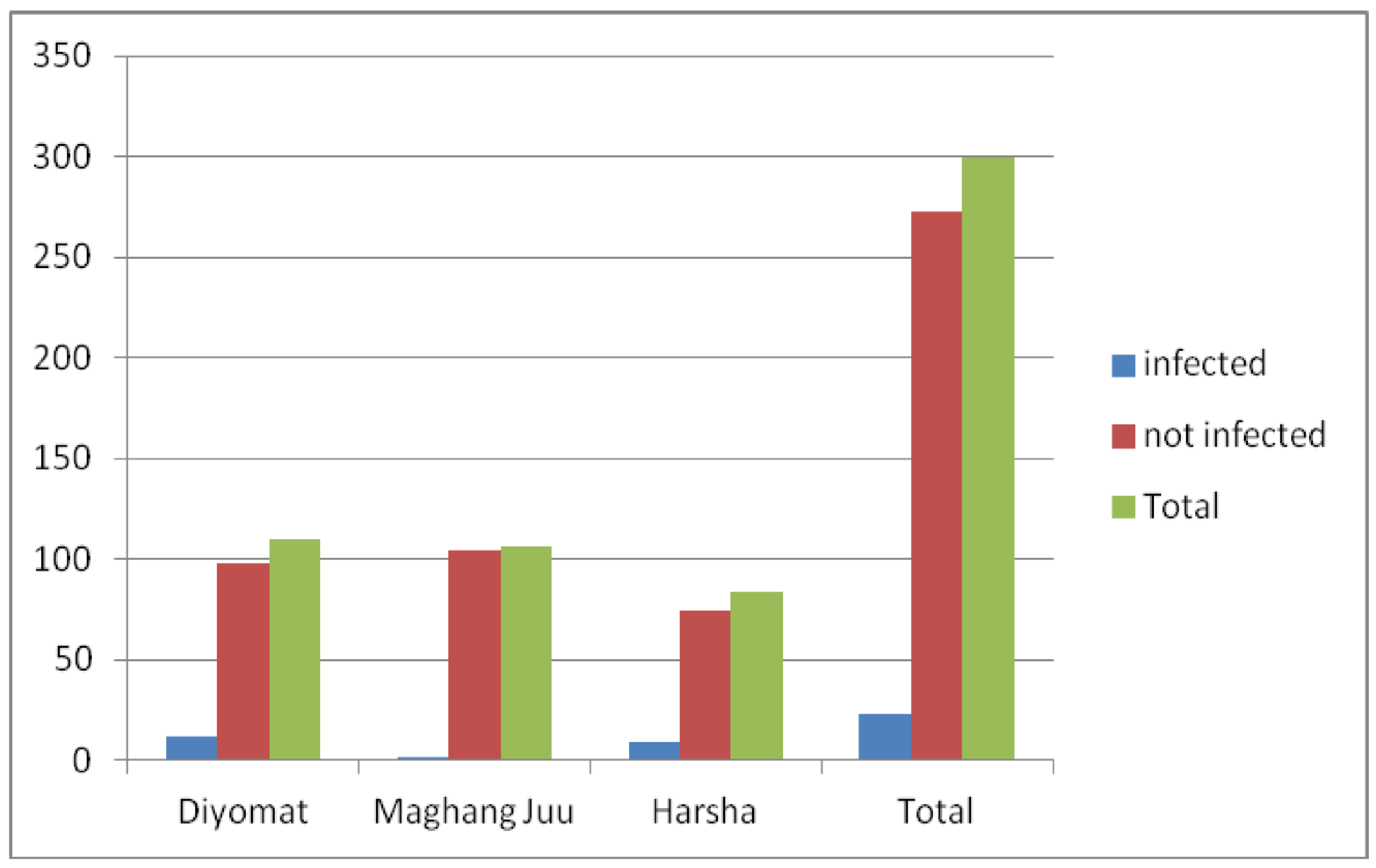

Eighty-nine households were visited during the survey. The availability of tap water was observed in two of the three villages. Maghang Juu had 14 water delivery points and people were getting water throughout the year. The community in this village was connected with low cysticercosis infection status. People living in Maghang Juu were the least infected and differed statistically with Harsha and Diyomat (

Figure 3). Diyomat had five water delivery points with seasonal water availability mainly during the rainy seasons. Harsha had 11 water delivery points without water throughout the year; the community in this village was linked with a high prevalence of cysticercosis (

Figure 3). Free-range pig rearing was observed in all three villages. About 46(51.7%) of the visited households had no latrines/toilets. More than 50 % of the households inspected had no access to clean and safe water supply (tap water) (

Table 3). Human faeces were often observed near footpaths as research team moved from one household to another.

Discussion

The current study shows that human infection with T.solium cysticercosis in Mbulu District is high (7.67%). The prevalence was not statistically different between those who received and those who did not receive anthelminthic during the previous year. This may be a result of low anthelminthic coverage in the communities by targeting school children only, thus continued transmission among elder age groups as indicated by the results of this study. The high prevalence of cysticercosis established in this study has the implication of environmental contamination with infective teniid eggs from human faces and faecal-oral infections due to lack of clean and safe water as reported in over half of the surveyed households. The absence of difference in the infection among those who received anthelmintic and those who didn’t receive may be explained by the continued carriers in the communities contaminating environment including water as more than half of the surveyed households didn’t have access to tape water and more than two-thirds of the community members didn’t receive anthelminthic because they were not targeted despite being at risk of infection.

The prevalence of human cysticercosis in this study is lower than that reported previously (Mwang’onde et al., 2018). This may be a result of different diagnostic assays used with different sensitivity and specificity. The current study used antigen ELISA which detects the active parasite while the previous study used IgG western blot Assay (Mwang’onde et al., 2018) which detects exposure to the parasite infection. Furthermore, individuals who tested negative for this test could have tested positive for the antibody tests as observed in studies elsewhere in Tanzania, Zambia, and Venezuela (Mwanjali et al., 2013; Mwape et al., 2013; Rojas et al., 2019).

There was a variation in the prevalence of human cysticercosis across villages. The prevalence was higher at Harsha village, and this could be associated with the absence of clean and safe water, and underuse of pit latrines, and the presence of free-ranging pigs. The relatively high prevalence among people of Diyomat may be explained among other reasons by the shared water source for irrigation, thus no water supply throughout the year. The low prevalence at Maghang Juu was most likely associated with the availability and use of safe and clean water throughout the year. These risk factors were in line with similar endemic communities reported in other studies elsewhere (Alexander et al., 2012; Carabin et al., 2018).

From these findings, mass drug administration in primary school children seems to have little effect on the prevalence of cysticercosis, most likely due to low coverage of the targeted school children about 20% of the total population (World Bank, 2018b). Previous studies have shown that porcine cysticercosis was high in households that were not using latrines and among those practicing free-ranging pig (Kabululu, et al., 2020; Ngowi et al., 2004; Shonyela et al., 2017). Similarly, in Mozambique, free-ranging has been reported as an important risk factor (Pondja et al., 2010). Individuals of higher age were at high risk because they were not involved in the National school deworming program. The community with uneven supply and use of clean and safe water had a high prevalence of human cysticercosis which was the case in Harsha village, implying an increased risk of human cysticercosis infection in communities with similar risk factors. This study used antigen test thus missing those infected but recovered from infection.

Conclusion

The study established a high prevalence of human cysticercosis among higher age groups compared to lower age groups. This reveals that school deworming has a positive effect in lowering the prevalence of cysticercosis in lower age groups. It is recommended that the deworming program should be scaled up to higher age groups.

Authors Contributions

Conceptualization, Vedasto Bandi, Bernard Ngowi, Emmanuel Mpolya and John-Mary Vianney; Formal analysis, Vedasto Bandi, Bernard Ngowi, Emmanuel Mpolya and John-Mary Vianney; Methodology, Vedasto Bandi, Bernard Ngowi, Emmanuel Mpolya and John-Mary Vianney; Supervision, Bernard Ngowi, Emmanuel Mpolya and John-Mary Vianney; Writing – original draft, Vedasto Bandi; Writing – review & editing, Andrew Kilale.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the Mbulu District Medical Officer, Dr. Bonaventura R. Chitopeka, and Veterinary Officer in Charge, and Dr. Moses Nduligu for their support during field data collection. We acknowledge the research assistants; Fatuma Said, Judy Swai, Anna Mbowe, and Bernadeta Tungu; and the village and ward authority for accommodating us in their respective wards and villages. We acknowledge the Higher Education Students Loans Board of Tanzania for field financial support and the Centre for Research, Agricultural Advancement, Teaching Excellence, and Sustainability in Food and Nutrition Security (CREATES) of NM-AIST for the financial support to the fieldwork. Thanks to the Tanzania Military Academy Hospital for sample storage.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Medical Research Coordinating Committee of the National Institute of Medical Research in Tanzania (Reference No. NIMR/HQ/R.8c/Vol.1/1612). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects ≥18 years, and consent was obtained from parents or guardians of the respective individuals <18 years old following the subject’s assent.

Consent for publication

All authors approved the manuscript for publication

Availability of Data and material

All data are available in the main document

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

List of Abbreviations

ELISA- Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay

NCC- Neurocysticercosis

NIMR- National Institute for Medical Research

OD- Optical density

SPSS- Statistical Package for Social Sciences

WHO- World Health Organisation

References

- Alexander, A. M., Mohan, V. R., Muliyil, J., Dorny, P., & Rajshekhar, V. (2012). Changes in knowledge and practices related to taeniasis/cysticercosis after health education in a south Indian community. International Health, 4(3), 164–169. [CrossRef]

- ApDia. (2004). In vitro diagnostic kit Cysticercosis Ag ELISA. 5–6.

- Braae, U. C., Saarnak, C. F. L., Mukaratirwa, S., Devleesschauwer, B., Magnussen, P., & Johansen, M. V. (2015). Taenia solium taeniosis/cysticercosis and the co-distribution with schistosomiasis in Africa. Parasites and Vectors, 8(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Carabin, H., Millogo, A., Ngowi, H. A., Bauer, C., Dermauw, V., Koné, A. C., Sahlu, I., Salvator, A. L., Preux, P. M., Somé, T., Tarnagda, Z., Gabriël, S., Cissé, R., Ouédraogo, J. B., Cowan, L. D., Boncoeur-Martel, M. P., Dorny, P., & Ganaba, R. (2018). Effectiveness of a community-based educational programme in reducing the cumulative incidence and prevalence of human Taenia solium cysticercosis in Burkina Faso in 2011–14 (EFECAB): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Global Health, 6(4), e411–e425. [CrossRef]

- CDC. (2017). One Health Zoonotic Disease Prioritization for Multi-Sectoral Engagement in Tanzania. 1–24. https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/pdfs/uganda-one-health-zoonotic-disease-prioritization-report-508.pdf.

- Chemotherapy, P. (2021). Guideline for Preventive Chemotherapy for the Control of Taenia solium Taeniasis. In Guideline for Preventive Chemotherapy for the Control of Taenia solium Taeniasis. [CrossRef]

- Del Brutto, O. H. (2014). Neurocysticercosis. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 121, 1445–1459. [CrossRef]

- DPLO. (2015). MBULU DISTRICT COUNCIL STRATEGIC PLAN. 3(December), 1–6.

- Galán-Puchades, M. T. (2016). Taeniasis vs cysticercosis infection routes. In Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine (Vol. 9, Issue 6, pp. 619–620). [CrossRef]

- Gulelat, Y., Eguale, T., Kebede, N., Aleme, H., & Fèvre, E. M. (2022). Epidemiology of Porcine Cysticercosis in Eastern and Southern Africa : Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 10(March), 6–8. [CrossRef]

- Ito, A., Wandra, T., Li, T., Dekumyoy, P., Nkouawa, A., Okamoto, M., & Budke, C. (2015). The Present Situation of Human Taeniases and Cysticercosis in Asia. Recent Patents on Anti-Infective Drug Discovery, 9(3), 173–185. [CrossRef]

- Kabululu, M. L., Johansen, M. V, Lightowlers, M., Trevisan, C., Braae, U. C., & Ngowi, H. A. (2023). Aggregation of Taenia solium cysticerci in pigs : Implications for transmission and control. Parasite Epidemiology and Control, 22(October 2022), e00307. [CrossRef]

- Kabululu, M. L., Ngowi, H. A., Mlangwa, J. E. D., Mkupasi, E. M., Braae, U. C., Colston, A., Cordel, C., Poole, E. J., Stuke, K., & Johansen, M. V. (2020). Tsol18 vaccine and oxfendazole for control of taenia solium cysticercosis in pigs: A field trial in endemic areas of tanzania. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 14(10), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Kabululu, M. L., Ngowi, H. A., Mlangwa, J. E. D., Mkupasi, E. M., Braae, U. C., Trevisan, C., Colston, A., Cordel, C., & Johansen, M. V. (2020). Endemicity of Taenia solium cysticercosis in pigs from Mbeya Rural and Mbozi districts , Tanzania. 1–9.

- Lozano, R., Naghavi, M., Foreman, K., Lim, S., Shibuya, K., Aboyans, V., Abraham, J., Adair, T., Aggarwal, R., Ahn, S. Y., AlMazroa, M. A., Alvarado, M., Anderson, H. R., Anderson, L. M., Andrews, K. G., Atkinson, C., Baddour, L. M., Barker-Collo, S., Bartels, D. H., … Murray, C. J. (2012). Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 380(9859), 2095–2128. [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, S., & Garcia, H. H. (2010). Cysticercosis and neurocysticercosis as pathogens affecting the nervous system. Progress in Neurobiology, 91(2), 172–184. [CrossRef]

- Mata, D. E., Craig, S., & Mencos, F. (1996). Epidemiology of Taenia solium taeniasis and in two rural Guatemalan communities. 55(3), 282–289. [CrossRef]

- Minani, S., Devleesschauwer, B., Gasogo, A., Ntirandekura, J. B., Gabriël, S., Dorny, P., & Trevisan, C. (2022). Assessing the burden of Taenia solium cysticercosis in Burundi, 2020. BMC Infectious Diseases, 22(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Montano, S. M., Villaran, M. V., Ylquimiche, L., Figueroa, J. J., Rodriguez, S., Bautista, C. T., Gonzalez, A. E., Tsang, V. C. W. C. W., Gilman, R. H., & Garcia, H. H. (2005). Neurocysticercosis: Association between seizures, serology, and brain CT in rural Peru. Neurology, 65(2), 229–234. [CrossRef]

- Mwang’onde, B. J., Chacha, M. J., & Nkwengulila, G. (2018). The status and health burden of neurocysticercosis in Mbulu district, northern Tanzania. BMC Research Notes, 11(1), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Mwang’onde, B., Nkwengulila, G., & Chacha, M. (2012). The Serological Survey for Human Cysticercosis Prevalence in Mbulu District, Tanzania. Advances in Infectious Diseases, 02(03), 62–66. [CrossRef]

- Mwanjali, G., Kihamia, C., Kakoko, D. V. C., Lekule, F., Ngowi, H., Johansen, M. V., Thamsborg, S. M., & Willingham, A. L. (2013). Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Human Taenia Solium Infections in Mbozi District, Mbeya Region, Tanzania. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 7(3), e2102. [CrossRef]

- Mwape, K. E., Phiri, I. K., Praet, N., Speybroeck, N., Muma, J. B., Dorny, P., & Gabriël, S. (2013). The Incidence of Human Cysticercosis in a Rural Community of Eastern Zambia. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 7(3). [CrossRef]

- Mwita, C. J., Yohana, C., & Nkwengulila, G. (2013). The Prevalence of Porcine Cysticercosis and Risk Factors for Taeniasis in Iringa Rural District. International Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances, 5(6), 251–255. http://www.maxwellsci.com/print/ijava/v5-251-255.pdf. [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics & Office of Chief Government Stastician. (2013). 2012 Population and Housing Survey. Population Distribution by Administrative areas - United Republic of Tanzania.

- Ngowi, H. ., Kassuku, A. ., Maeda, G. E. ., Boa, M. ., Carabin, H., & Willingham, A. . (2004). Risk factors for the prevalence of porcine cysticercosis in Mbulu District, Tanzania. Veterinary Parasitology, 120(4), 275–283. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S030440170400041X. [CrossRef]

- Ngowi, H. A., Winkler, A. S., Braae, U. C., Mdegela, R. H., Mkupasi, E. M., Kabululu, M. L., Lekule, F. P., & Johansen, M. V. (2019). Taenia solium taeniosis and cysticercosis literature in Tanzania provides research evidence justification for control: A systematic scoping review. PLoS ONE, 14(6), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Okello, A. L., & Thomas, L. F. (2017). Human taeniasis: Current insights into prevention and management strategies in endemic countries. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 10, 107–116. [CrossRef]

- Pondja, A., Neves, L., Mlangwa, J., Afonso, S., Fafetine, J., Willingham, A. L., Thamsborg, S. M., & Johansen, M. V. (2010). Prevalence and risk factors of porcine cysticercosis in Angónia District, Mozambique. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 4(2). [CrossRef]

- Resources, F. (2003). School Deworming. Tropical Medicine, November, 3–6.

- Rojas, R. G., Patiño, F., Pérez, J., Medina, C., Lares, M., Méndez, C., Aular, J., Parkhouse, R. M. E., & Cortéz, M. M. (2019). Transmission of porcine cysticercosis in the Portuguesa state of Venezuela. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 51(1), 165–169. [CrossRef]

- Rotondi, M., & Donner, A. (2012). Sample size estimation in cluster randomized trials : An evidence-based perspective. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 56(5), 1174–1187. [CrossRef]

- Shonyela, S. M., Mkupasi, E. M., Sikalizyo, S. C., Kabemba, E. M., Ngowi, H. A., & Phiri, I. (2017). An epidemiological survey of porcine cysticercosis in Nyasa District, Ruvuma Region, Tanzania. Parasite Epidemiology and Control, 2(4), 35–41. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, N., Husain, N., Venkatesh, V., Masood, J., & Husain, M. (2010). Seroprevalence of cysticercosis in North Indian population. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine, 3(8), 589–593. [CrossRef]

- Torgerson, P. R., Devleesschauwer, B., Praet, N., Speybroeck, N., Willingham, A. L., Kasuga, F., Rokni, M. B., Zhou, X. N., Fèvre, E. M., Sripa, B., Gargouri, N., Fürst, T., Budke, C. M., Carabin, H., Kirk, M. D., Angulo, F. J., Havelaar, A., & de Silva, N. (2015). World Health Organization Estimates of the Global and Regional Disease Burden of 11 Foodborne Parasitic Diseases, 2010: A Data Synthesis. PLoS Medicine, 12(12), 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Torgerson, P. R., & Macpherson, C. N. L. (2011). Veterinary Parasitology The socioeconomic burden of parasitic zoonoses : Global trends. Veterinary Parasitology, 182(1), 79–95. [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, C., Devleesschauwer, B., Schmidt, V., Winkler, A. S., Harrison, W., & Johansen, M. V. (2017). The societal cost of Taenia solium cysticercosis in Tanzania. Acta Tropica, 165, 141–154. [CrossRef]

- Winkler, A. S. (2012). Neurocysticercosis in sub-Saharan Africa : a review of prevalence , clinical characteristics , diagnosis , and management. 261–274. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2018a). Guidelines for School-based Deworming Programs: Information for policy-makers and planners on conducting deworming as part of an integrated school health program.

- World Bank. (2018b). National Education Profile: Tanzania 2018 Update. https://www.epdc.org/sites/default/files/documents/EPDC_NEP_2018_Tanzania.pdf.

- Yancey, L. S., Diaz-Marchan, P. J., & White, A. C. (2005). Cysticercosis: Recent advances in diagnosis and management of neurocysticercosis. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 7(1), 39–47. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).