Submitted:

15 December 2023

Posted:

18 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

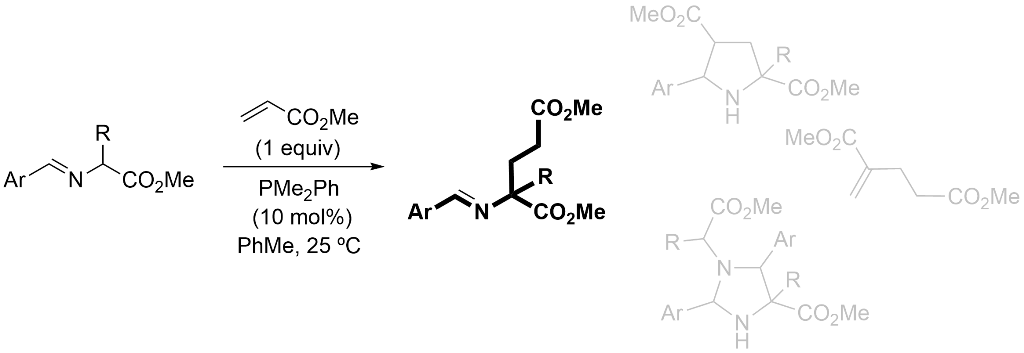

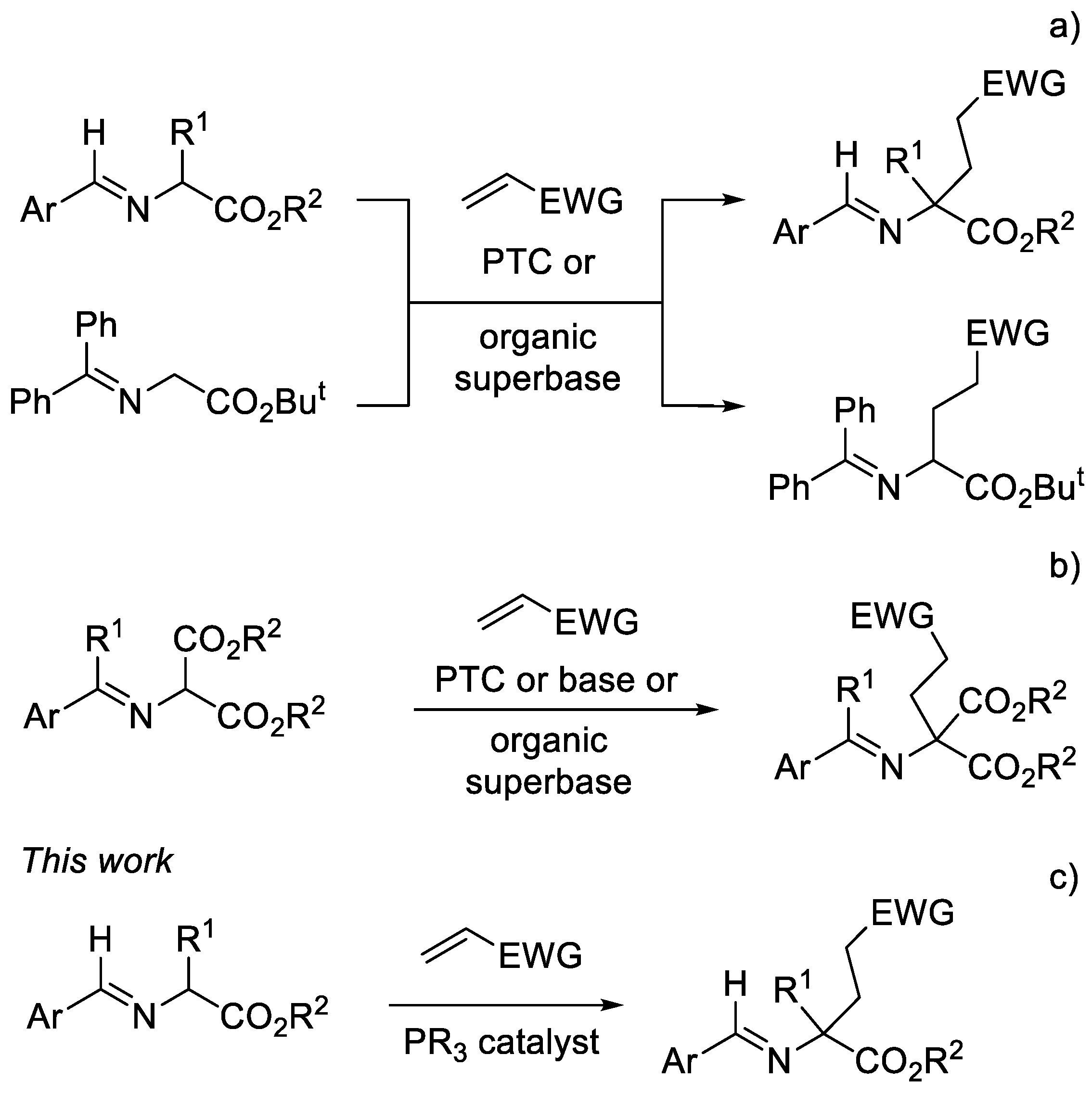

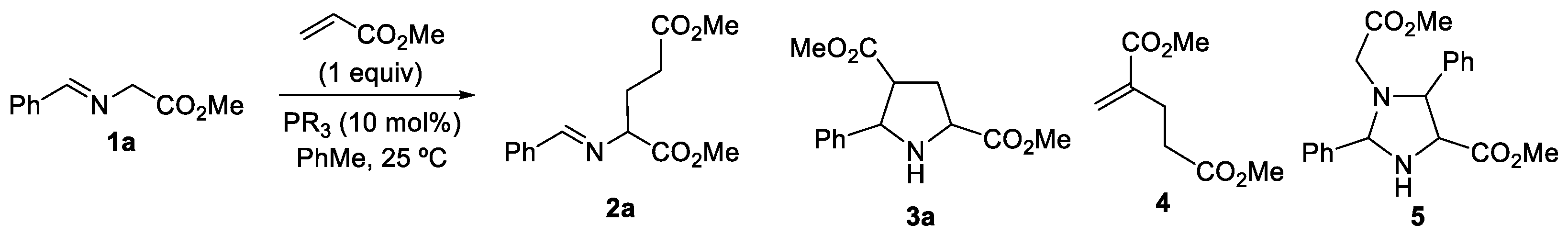

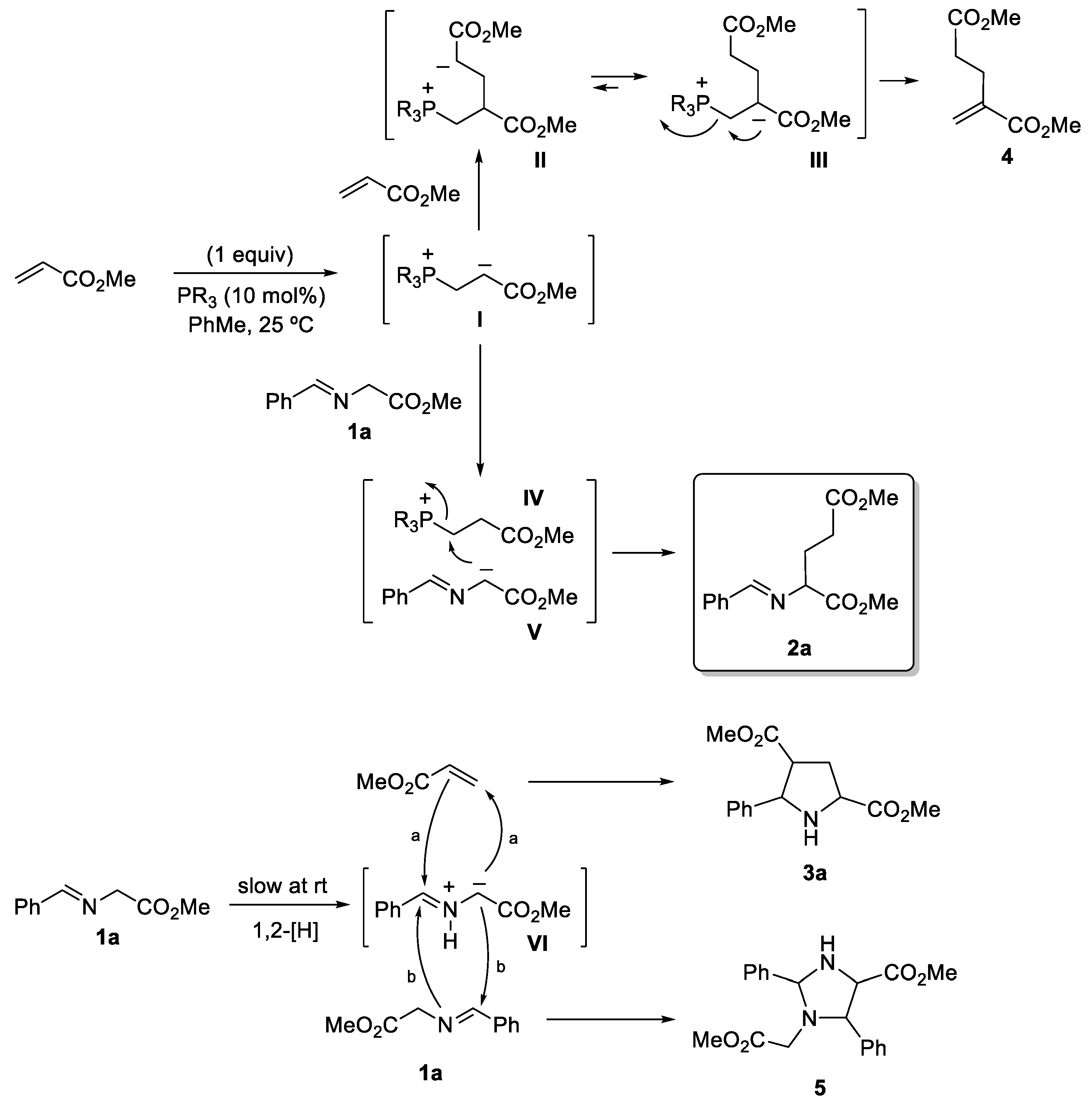

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General

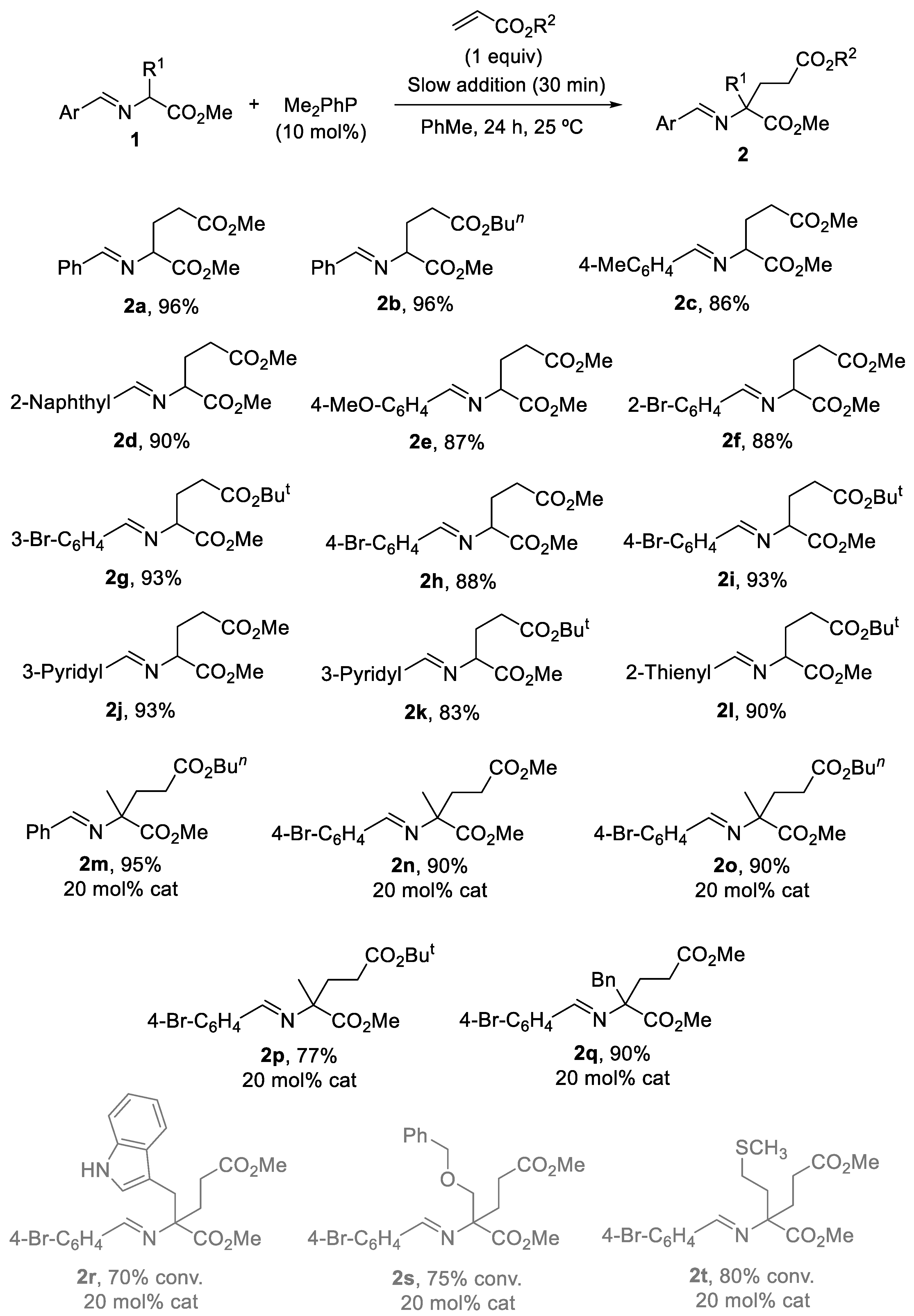

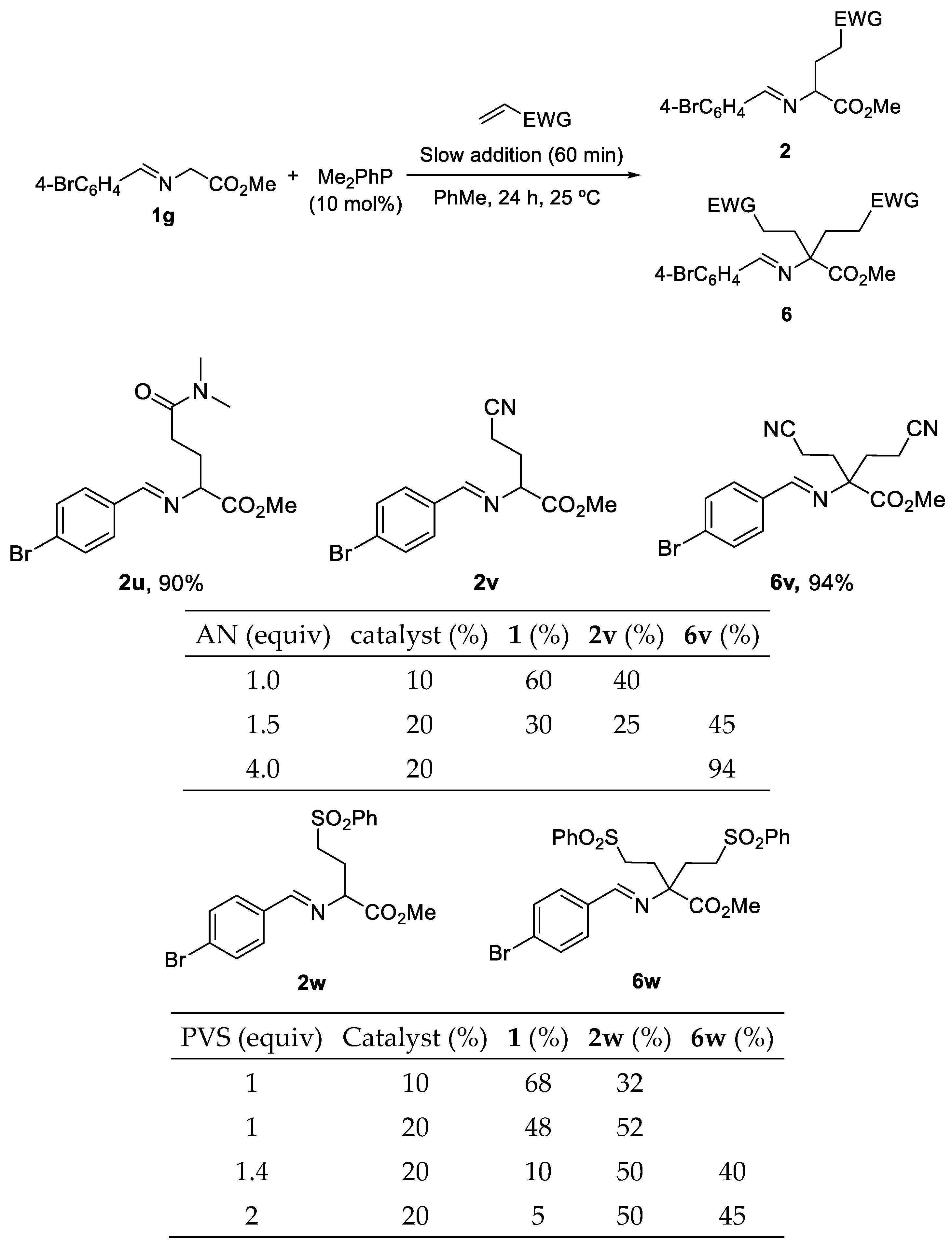

3.2. General Experimental Procedure for the Synthesis of Michael Type Addition Products 2

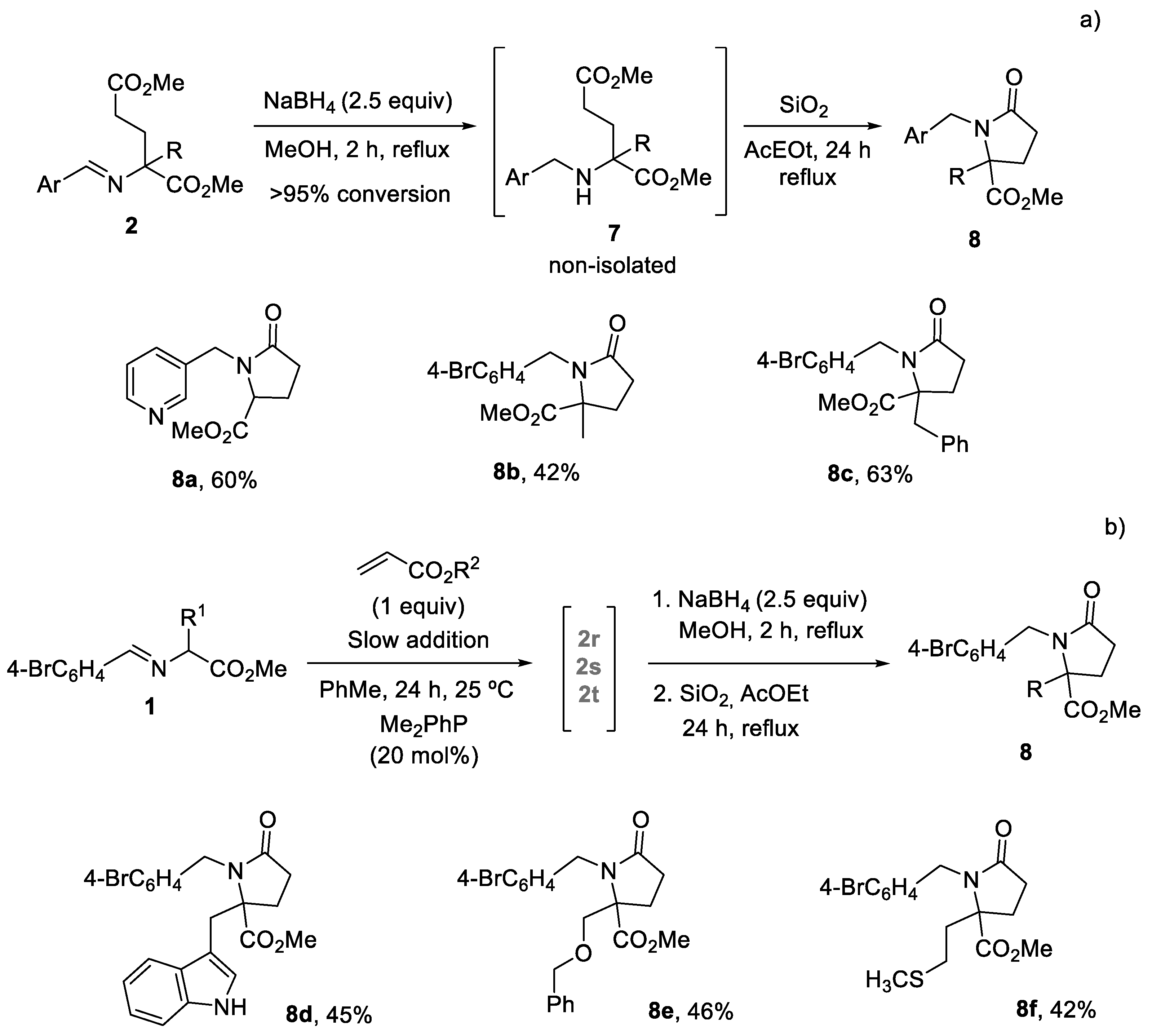

3.3. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Pyroglutamate Derivatives

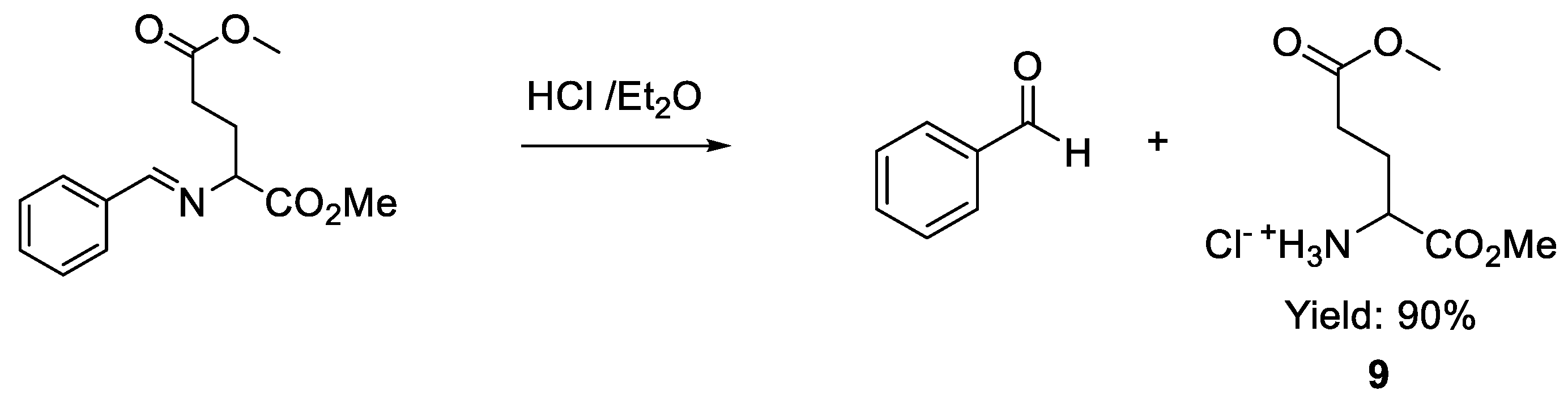

3.4. Procedure to Obtain the Glutamic acid 1,5-dimethyl ester Hydrochloride 9 [[28]]

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- For recent reviews concerning to the synthesis of AAs, see: (a) Eder, I.; Haider, V.; Zebrowski, P.; Waser, M. Recent Progress in the Asymmetric Syntheses of α-Heterofunctionalized (Masked) α- and β-Amino Acid Derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.202001077. (b) Yuan, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Rao, Y. Recent Advances in Rapid Synthesis of Non-proteinogenic Amino Acids from Proteinogenic Amino Acids Derivatives via Direct Photo-Mediated C–H Functionalization. Molecules 2020, 25, 5270-5310. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25225270. (c) Masamba, W. Petasis vs. Strecker Amino Acid Synthesis: Convergence, Divergence and Opportunities in Organic Synthesis. Molecules 2021, 26, 1707-1730. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25225270.

- (a) Zhou, M.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, X. Recent advances in the synthesis of fluorinated amino acids and peptides. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 1434-1448. doi.org/10.1039/D2CC06787K. (b) Shatskiy, A.; Kaerkaes, M. D. Photoredox-enabled decarboxylative synthesis of unnatural α-amino acids. Synlett 2022, 33, 109-115. doi: 10.1055/a-1499-8679. (c) Forro, E.; Fulop, F. Enzymatic Strategies for the Preparation of Pharmaceutically Important Amino Acids through Hydrolysis of Amino Carboxylic Esters and Lactams. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 6218-6227. Doi: 10.2174/0929867329666220718123153. (d) Larionov, V. A.; Stoletova, N. V.; Maleev, V. I. Advances in asymmetric amino acid synthesis enabled by radical chemistry Adv. Synth. Cat. 2020, 362, 4325-4367. doi.org/10.1002/adsc.202000753. (e) Yuan, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Rao, Y. Recent advances in rapid synthesis of non-proteinogenic amino acids from proteinogenic amino acids derivatives via direct photo-mediated C-H functionalization. Molecules 2020, 25, 5270. (f) O'Donnell, M. J. Benzophenone Schiff bases of glycine derivatives: Versatile starting materials for the synthesis of amino acids and their derivatives. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 3667-3696. (g) Xue, Y.-P.; Cao, C.-H.; Zheng, Y.-G. Enzymatic asymmetric synthesis of chiral amino acids. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 1516-1561. doi.org/10.1039/C7CS00253J. (h) Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Wang, J.; Moriwaki, H.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Liu, H. Recent approaches for asymmetric synthesis of α-amino acids via homologation of Ni(II) complexes. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 1487-1520. DOI: 10.1007/s00726-017-2458-6. (i) He, G.; Wang, B.; Nack, W. A.; Chen, G. Syntheses and Transformations of α-Amino Acids via Palladium-Catalyzed Auxiliary-Directed sp3 C-H Functionalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 635-645. doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00022. (j) Nájera, C.; Sansano, J. M. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of α-Amino Acids. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 4584−4671. doi.org/10.1021/cr050580o.

- (a) Yin, G.-W.; Wu, S.-L.; Yan, J.-H.; Zhang, P.-F.; Yang, M.-M.; Li, L.; Xu, Z.; Yang, K.-F.; Xu, L.-W. Swollen-induced in-situ encapsulation of chiral silver catalysts in cross-linked polysiloxane elastomers: Homogeneous reaction and heterogeneous separation. Mol. Catal. 2021, 515, 111901. doi.org/10.1016/j.mcat.2021.111901. (b) Seibel, Z. M.; Bandar, J. S.; Lambert, T. H. Enantioenriched α-substituted glutamates/pyroglutamates via enantioselective cyclopropenimine-catalyzed Michael addition of amino ester imines. Beilst. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 17, 2077-2084. doi.org/10.3762/bjoc.17.134. (c) Grigg, R.; Kemp, J.; Malone, J. P.; Rajviroongit, S.; Tangthonkum, A. X=Y-ZH Systems as potential 1,3-dipoles. Part 17. Sequential Michael addition-5-endo-trig cyclisation of arylideneimines of α-amino acid esters. Tetrahedron 1988, 44, 5361-5374. doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4020(01)86043-9.

- (a) Bai, Y.-J.; Cheng, M.L.; Zheng, X.-H.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Wang, P. A. Chiral Cyclopropenimine-catalyzed Asymmetric Michael Addition of Bulky Glycine Imine to α,β-Unsaturated Isoxazoles. chiral organosuperbase catalyst. Chem. Asian J. 2022, 17, e202200131. doi.org/10.1002/asia.202200131. (b) Leonardi, C.; Brandolese, A.; Preti, L.; Bortolini, O.; Polo, E.; Dambruoso, P.; Ragno, D.; Di Carmine, G.; Massi, A. Expanding the Toolbox of Heterogeneous Asymmetric Organocatalysts: Bifunctional Cyclopropenimine Superbases for Enantioselective Catalysis in Batch and Continuous Flow. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 5473-5485. doi.org/10.1002/adsc.202100757. (c) Tyszka-Gumkowska, A.; Jurczak, J. Divergent synthesis of pyrrolidine and glutamic acid derivatives using a macrocyclic phase-transfer catalyst under high-pressure conditions. Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 5888-5894. doi.org/10.1039/D1QO01198G. (d) Bai, Y.-J.; Hu, X.-M.; Bai, Y.-J.; Zheng, X.-H.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Ping-An, W. DBU-catalyzed Michael addition of bulky glycine imine to α,β-unsaturated isoxazoles and pyrazolamides. Tetrahedron 2021, 101, 132511. doi.org/10.3762/bxiv.2021.18.v1. (e) Meninno, S.; Carratu, M.; Overgaard, J.; Lattanzi, A. Diastereoselective Synthesis of Functionalized 5-Amino-3,4-Dihydro-2H-Pyrrole-2-Carboxylic Acid Esters: One-Pot Approach Using Commercially Available Compounds and Benign Solvents. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 4573-4577. doi.org/10.1002/chem.202005262.

- For other different alkylations or allylations, see references 1-3. O'Donnell, M. J.; Boniece, J. M.; Earp, S. E. The synthesis of amino acids by phase-transfer reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978, 2641–2644. [CrossRef]

- (a) Duan, X.-Y.; Tian, Z.; Liu, B.; He, T.; Zhao, L.-L.; Dong, M.; Zhang, P.; Qi, J. Highly Enantioselective Synthesis of Pyrroloindolones and Pyrroloquinolinones via an N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed Cascade Reaction. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 3777-3781. doi.org/10.1021/acs.orglett.1c01203. (b) Ren, N.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X.; Deng, Z.; Chen, J.; Deng, H.; Zhang, H.; Tang, X.-J.; Cao, W. Perfluoroalkyl-Promoted Synthesis of Perfluoroalkylated Pyrrolidine-Fused Coumarins with Methyl β-Perfluoroalkylpropionates. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 15717-15725. doi.org/10.1021/acs.joc.1c01538.

- For specific alkylations and allylations, see: (a) Xiao, F.; Xu, S. M.; Dong, X.-Q.; Wang, C.-J. Allylations Ir-Catalyzed Asymmetric Tandem Allylation/Iso-Pictet−Spengler Cyclization Reaction for the Enantioselective Construction of Tetrahydro-γ-carbolines. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 706−710. Doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c03909. (b) Barlow, S. R.; Callaghan, L. J.; Franckevicius, V. Investigation of the palladium-catalysed cyclisation of α-amido malonates with propargylic compounds. Tetrahedron 2021, 80, 131866. doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2020.131866. (c) Cui, Z.; Zhang, K.; Gu, L.; Bu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Q. Diastereoselective trifunctionalization of pyridinium salts to access structurally crowded azaheteropolycycles. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 9402-9405. doi.org/10.1039/D1CC03478B. (d) Ha, M. W.; Lee, M.; Choi, S.; Kim, S.; Hong, S.; Park, Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, T.-S.; Lee, J.; Lee, J. K.; Park, H.-g. Construction of Chiral α-Amino Quaternary Stereogenic Centers via Phase-Transfer Catalyzed Enantioselective α-Alkylation of α-Amidomalonates. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 3270-3279. doi.org/10.1021/jo502791d. (e) Li, J.-T.; Luo, J.-N.; Wang, J.-L.; Wang, D.-K.; Yu, Y.-Z.; Zhuo, C.-X. Stereoselective intermolecular radical cascade reactions of tryptophans or ɤ-alkenyl-α-amino acids with acrylamides via photoredox catalysis. Nature Commun. 2022, 13, 1778-1785. Doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29464-5.

- N-Amidomalonates required stronger bases: Banerjee, I.; Ghosh, K. C.; Oheix, E.; Jean, M.; Naubron, J. V.; Réglier, M.; Iranzo, O.; Sinha, S. Synthesis of Protected 3,4- and 2,3-Dimercaptophenylalanines as Building Blocks for Fmoc-Peptide Synthesis and Incorporation of the 3,4-Analogue in a Decapeptide Using Solid-Phase Synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 2210−2223. doi.org/10.1021/acs.joc.0c02359.

- Glutamate is a versatile-multifunctional metabolite and a signaling molecule in plants. Liao, H.-S.; Chung, Y.-H.; Hsieh, M.-H. Glutamate: A multifunctional amino acid in plants. Plant Sci. 2022, 318, 111238. [CrossRef]

- Bayer, T. A. Pyroglutamate Aβ cascade as drug target in Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 1880-1885. [CrossRef]

- (a) Natural Product Isoliquiritigenin Activates GABAB Receptors to Decrease Voltage-Gate Ca2+ Channels and Glutamate Release in Rat Cerebrocortical Nerve Terminals. Lin, T.-Y.; Lu, C.-W.; Hsieh, P.-W.; Chiu, K.-M.; Lee, M.-Y.; Wang, S.-J. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1537-1548. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11101537. (b) Gulder, T. A. M.; Moore, B. S. Salinosporamide Natural Products: Potent 20 S Proteasome Inhibitors as Promising Cancer Chemotherapeutics. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9346–9367. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201000728. (c) Panday, S. K.; Prasad, J.; Dikshit, D. K. Pyroglutamic acid: a unique chiral synthon. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2009, 20, 1581–1632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetasy.2009.06.011. (d) Zhang, J.; Flippen-Anderson, J. L.; Kozikowski, A. P. A Tandem Michael Addition Ring-Closure Route to the Metabotropic Receptor Ligand α-(Hydroxymethyl)glutamic Acid and Its γ-Alkylated Derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 7555–7559. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo010626n.

- Pyroglutamate unit are constituent parts of, for example: (a) Tekkam, S.; Alam, M. A.; Just, M. J.; Berry, S. M.; Johnson, J. L.; Jonnalagadda, S. C.; Mereddy, V. R. Stereoselective Synthesis of Pyroglutamate Natural Product Analogs from α-Aminoacids and their Anti-Cancer Evaluation. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 1514-1530. https://doi.org/10.2174/18715206113139990097. (b) Katoh, M.; Hisa, C.; Honda, T. Enantioselective synthesis of (R)-deoxydysibetaine and (−)-4-epi-dysibetaine. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 4691–4694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.05.007. (b) Isaacson, J.; Loo, M.; Kobayashi, Y. Total Synthesis of (±)-Dysibetaine. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 1461–1463. https://doi.org/10.1021/ol800245m. (c) Ma, G.; Nguyen, H.; Romo, D. Concise Total Synthesis of (±)-Salinosporamide A, (±)-Cinnabaramide A, and Derivatives via a Bis-cyclization Process: Implications for a Biosynthetic Pathway? Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2143–2146. https://doi.org/10.1021/ol070616u. (d) Ling, T.; Macherla, V. R.; Manam, R. R.; McArthur, K. A.; Potts, B. C. M. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (−)-Salinosporamide A (NPI-0052). Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2289–2292. https://doi.org/10.1021/ol0706051. (e) Shibasaki, M.; Kanai, M.; Fukuda, N. Total Synthesis of Lactacystin and Salinosporamide A. Chem. Asian J. 2007, 2, 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.200600310. (f) Masse, C. E.; Morgan, A. J.; Adams, J.; Panek, J. S. Syntheses and Biological Evaluation of (+)-Lactacystin and Analogs. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 2513–2528. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0690(200007)2000:14<2513::AID-EJOC2513>3.0.CO;2-D.

- An enantioselective version was reported using chiral silver complexes: Bai, X.-F.; Li, L.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, Z.-J.; Xia, C. G.; Cui, Y. M.; Xu, L.-W. Asymmetric Michael-addition of aldimino esters with chalcones catalyzed by Silver/Xing-Phos: Mechanism-oriented divergent synthesis of chiral pyrrolines. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 10399-10404. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Fan, Y. C.; Sun, Z.; Wu, Y.; Kwon, O. Phosphine Organocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 10049–10293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (a) Molteni, G.; Silvani, A. Spiro-2-oxindoles via 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions. A decade update. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 1653-1675. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.202100121. (b) Nájera, C.; Sansano, J. M. Synthesis of pyrrolizidines and indolizidines by multicomponent 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of azomethine ylides. Pure Appl. Chem. 2019, 91, 575-596. https://doi.org/10.1515/pac-2018-0710. (c) Dondas, H. A.; Retamosa, M. G.; Sansano, J. M. Synthesis 2017, 49, 2819−2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27144579. (d) Bdiri, B.; Zhao, B.-J.; Zhou, Z.-M. Recent advances in the enantioselective 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of azomethine ylides and dipolarophiles. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2017, 28, 876−899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetasy.2017.05.010. For asymmetric 1,3-DCs, see: (e) Wei, L.; Chang, X.; Wang, C.-J. Catalytic Asymmetric Reactions with N-Metallated Azomethine Ylides. Acc. Chem. Res., 2020, 53, 1084-1100. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00113. (f) Adrio, J.; Carretero, J. C. Stereochemical diversity in pyrrolidine synthesis by catalytic asymmetric 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of azomethine ylides. Chem. Commun., 2019, 55, 11979-11991. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9CC05238K. (g) Fang, X.; Wang, C.-J. Catalytic asymmetric construction of spiropyrrolidines via 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of azomethine ylides. Org. Biomol. Chem., 2018, 16, 2591-2601. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7OB02686B. (h) De, N.; Yoo, E. J. Recent Advances in the Catalytic Cycloaddition of 1,n-Dipoles. ACS Catal., 2018, 8, 48-58. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.7b03346.

- Stewart, I. C.; Bergman, R. G.; Toste, F. D. Phosphine-Catalyzed Hydration and Hydroalkoxylation of Activated Olefins: Use of a Strong Nucleophile to Generate a Strong Base. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 29, 8696–8697. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rundlöf, T.; Mathiasson, M.; Bekiroglu, S.; Hakkarainen, B.; Bowden, T.; Arvidsson, T. Survey and qualification of internal standards for quantification by 1 H NMR Spectroscopy. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2010, 52, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purities of compounds were determined accordingly. See experimental section.

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Jia, M.; Peng, L.; Zhang, N.; Qi, S.; Zhang, L. Bifunctional additive phenyl vinyl sulfone for boosting cyclability of lithium metal batteries. Green Chem. Engin. 2023, 4, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, A. M.; Ghabbour, H. A.; Kabil, M. M.; Al-Rashood, S. T.; Abdel-Aziz, H. A. Synthesis, X-ray crystal structure, Hirshfeld analysis and computational investigation of bis(methylthio)acrylonitrile with antimicrobial and docking evaluation J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1260, 132793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, M.; Fujisawa, S. A structure-activity relationship study on the mechanisms of methacrylate-induced toxicity using NMR chemical shift of β-carbon, RP-HPLC log P and semiempirical molecular descriptor. Dental Mat. J. 2009, 28, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (a) Pérez-Garmendia, R.; Gevorkian, G. Pyroglutamate-Modified Amyloid Beta Peptides: Emerging Targets for Alzheimer´s Disease Immunotherapy. Curr. Neuropharm. 2013, 11, 491-498. DOI: 10.2174/1570159X11311050004. (b) Cynis, H.; Frost, Jeffrey L.; Crehan, Helen; Lemere, Cynthia A. Immunotherapy targeting pyroglutamate-3 Aβ: prospects and challenges. Mol. Neurodegener. 2016, 11, 48/1-48/11. doi.org/10.1186/s13024-016-0115-2. (c) Piechotta, A.; Parthier, C.; Kleinschmidt, M.; Gnoth, K.; Pillot, T.; Lues, I.; Demuth, H.-U.; Schilling, S.; Rahfeld, J.-U.; Stubbs, M. T. Structural and functional analyses of pyroglutamate-amyloid-β-specific antibodies as a basis for Alzheimer immunotherapy. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 12713-12724. doi.org/10.1186/s13024-016-0115-2. (d) Xu, C.; Wang, Y.-n.; Wu, H. Glutaminyl cyclase, diseases, and development of glutaminyl cyclase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 6549-6565. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00325. (e) Bayer, T. A. Pyroglutamate Aβ cascade as drug target in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 1880-1885. doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01409-2.

- Casas, J.; Grigg, R.; Nájera, C.; Sansano, J.M. The Effect of Phase-Transfer Catalysis in the 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Reactions of Azomethine Ylides− Synthesis of Substituted Prolines Using AgOAc and Inorganic Base in Substoichiometric Amounts. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 1971–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caleffi, G.; Larrañaga, O.; Ferrándiz-Saperas, M, Costa, P.; Nájera, C., de Cózar, A.; Cossío, F.; Sansano, J. M. Switching Diastereoselectivity in Catalytic Enantioselective (3+2) Cycloadditions of Azomethine Ylides Promoted by Metal Salts and Privileged Segphos-Derived Ligands. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 10593-10605. [CrossRef]

- Beksultanova, N.; Doğan, Ö. Asymmetric synthesis of aryl-substituted pyrrolidines by using CFAM ligand–AgOAc chiral system via 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction. Chirality 2023, 35, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moins, S.; Coulembier, O. Dimerization of Methyl Acrylate through CO2-pressurized DBU Mediated Process. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202100734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Bai, X.-F.; Ly, J.-Y.; Yuan, Y.; Cao, J.; Zheng, Z.-J.; Xu, Z.; Cui, Y.-M.; Yang, K. F.; Xu, L.-W. Enantioselective Synthesis of Chiral Imidazolidine Derivatives by Asymmetric Silver/Xing-Phos-Catalyzed Homo-1,3-Dipolar [3+2] Cycloaddition of Azomethine Ylides. Adv. Synth Cat. 2017, 359, 3577–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigl, M.; Wunsch, B. Synthesis of chiral non-racemic 3-(dioxopiperazin-2-yl)propionic acid derivatives. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry | PR3 (10 mol%) | Slow addition (min) | t (h) | 2a:3a:4:5:1aa |

| 1 | PPh3 | --- | 15 | 0:9:0:0:91 |

| 2 | dppe | --- | 15 | 37:22:0:4:37 |

| 3 | dppe | --- | 48 | 22:32:0:30:16 |

| 4 | dppe | --- | 72 | 56:39:0:5:0 |

| 5 | dppe | 1a (60) | 72 | 80:0:20:0:0 |

| 6 | dppe | MA (60) | 72 | 88:0:0:12:0 |

| 7 | dppe | MA (60) | 12 | 71:0:0:9:20 |

| 8 | Bu3P | --- | 72 | 0:0:0:100:0 |

| 9 | Bu3P | MA (60) | 72 | 0:0:100:0:0 |

| 10 | But3P | --- | 72 | 0:0:100:0:0 |

| 11 | Me2PhP | --- | 12 | 23:0:38:38:0 |

| 12 | Me2PhP | --- | 2 | 70:0:15:15:0 |

| 13 | Me2PhP | MA (60) | 2 | 70:5:0:5:20 |

| 14 | Me2PhP | MA (60) | 24 | 80:10:0:5:5 |

| 15 | Me2PhP | MA (30) | 24 | 97:0:0:0:3 |

| 16 | Me2PhP | MA (5) | 24 | 64:0:29:0:7 |

| 17 | Me2PhPb | MA (5) | 24 | 50:0:0:0:50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).