1. Introduction

Spinel ferrites are a material with wide technological applications such as a magnetic fluid, drug delivery material, magnetic recording material and pigments. Red spinel has been considered a gemstone, but until fairly modern times, it was not differentiated from the rare “ruby” (Cr-corundum solid solution) that can be distinguished by x-ray test which is the best method to differentiate between spinel and ruby [

1]. The spinel AB

2O

4 (SG.

Fd-3m) is built by O

2- ions in cubic closed-packed array and the A and B ions occupying the interstices in the structure. In the normal structure the A ion occupy one-eighth of the tetrahedral sites and the A ion one-half of the octahedral sites. On the inverse spinel all A ions and one-half of the B ions have exchanged places. Usually the crystal field stabilization energy (CFSE) of the transition metals present is used to explain the cation distribution on the spinel structure. J.K. Burdett [

2] proposed the use of the relative sizes of the s and p atomic orbitals of the two types of atoms to determine their site preference, because the dominant stabilizing interaction in the solids is not the crystal field stabilization energy but the σ-type interactions between the metal cations and the oxide anions. Only in cases where this size-based approach indicates no preference for one structure over another do crystal field effects make any difference.

Spinel forms gems of all colors, but the “Ruby Spinel”, a bright red spinel [

3] is the most valuable gem. Spinel gems are based in the presence of chromophores (Cr, Fe, V, Mn...) of different compositions, as the spinels based on zinc such as Gahnite ZnAl

2O

4, Franklinite or ZnFe

2O

4 and Zincochromite ZnCr

2O

4.

Franklinite is a normal spinel which is paramagnetic in the bulk form, but exhibits ferrimagnetic behaviour in nanocrystalline thin film format. A large room temperature magnetization and narrow ferromagnetic resonance linewidth have been achieved by controlling thin films growth conditions [

4]. However, Tanaka et al. [

5] have prepared, using the hydrothermal method, nanoparticles of zinc ferrite and reported that although the bulk zinc ferrite is an antiferromagnetic material having a Neel temperature around 10 K. The reason that zinc ferrites, which have a small magnetization value at bulk sizes, have a large magnetization value at room temperature is that zinc ferrite nanoparticles exhibit super paramagnetism. Because of their high opacity, zinc ferrites are used as magenta ceramic pigments [

6], which requiring heat stability, and shows high corrosion-resistant coatings in paints. The corrosion protection increases with the concentration of zinc ferrite [

7]. On the other hand, considering eco-friendly requirements, Calbo et al. [

8] reported black ceramic pigments based on Ni(Fe,Cr)

2O

4 spinels, which include toxic and hazardous elements such as Ni, Cr, prepared by ceramic method and optimised to reduce toxic and hazardous components replacing toxic by inert elements such as Mg and Zn minimising the content of Cr. Thereby, Schwarz et al. [

9] shows that MFe

2O

4 (M= Ca ,Zn) pigments, can be prepared from industrial wastes of metallurgical slag from the production of non-ferrous metals and two types of AMD (acid mine drainage) sludge: one of natural origin (Fe-sediment) and the second one synthetically prepared from AMD (Fe-precipitate. Due to the high Pb content in pigments from the slag (0.67–1.10 wt.% Pb in pigments), utilisation of these pigments in coatings is problematic. Ferrite pigments from the AMD sludge, mainly that with zinc ferrite, have promising application in anticorrosive paints but optimisation of the preparation process is required.

Gahnite (ZnAl

2O

4) crystallizes under normal conditions in a normal spinel structure. It is a stable material with a high melting temperature. This material has attracted a lot of attention in recent years because of its multifunctional applications such as phosphors, hydrogen generation, catalyst, transparent conducting oxide (TCO), gas sensing, and water gas shift. Although this material is a normal spinel, like materials in the spinel family, this material always has a degree of inversion which depends greatly on the method and the growth conditions and it varies from 0.01 to 0.35. This means that it is important to study the effect of the degree of inversion on the properties of this material [

10]. Thereby, Granone et al. [

11] have studied the effect of degree of inversion on the electrical properties of zinc ferrite and they showed that the electrical conductivity of ZnFe

2O

4 increases with the increasing of the degree of inversion. Quintero et al. [

12] have studied the effect of inversion on the magnetic properties of this material.

Zincochromite (ZnCr

2O

4) can be obtained by solid state reaction from oxides or carbonates sintering at elevated temperatures 1400°C several hours. Peng et al. [

13] synthesise nanoparticles of zincochromite by hydrothermal route with average particle size of <5 nm. The ZnCr

2O

4 nanoparticles have a direct band gap about 3.46 eV and exhibit blue emission in the range of 300–430 nm, cantered at 358 nm when excited at 220 nm. Furthermore, the nanoparticles show apparent photocatalytic activities for the degradation of methylene blue under UV light irradiation. Thereby, Mousavi et al. [

14] synthesized nanostructures through co-precipitation method. It was found that particle size and morphology of the products could be greatly influenced for parameters such as such as alkaline agent, pH value and capping agent type. The superhydrophilicity and the photocatalytic activity of ZnCr

2O

4 nanoparticles over anionic dyes such as Eosin-Y and phenol red under UV light irradiation are confirmed. In this case, ZnCr

2O

4 nanoparticles exhibit a paramagnetic behaviour although bulk ZnCr

2O

4 is antiferromagnetic, this change in magnetic property can be ascribed to finite size effects. Chen et al. [

15] use a coprecipitation method and used (EXAFS) to investigate the change of the inversion parameter vs the annealing temperature. The inversion parameter decreases with increasing annealing temperature: at 750 °C has a normal spinel structure, like bulk ZnCr

2O

4 but at 300°C is 24%.

Cool pigments show high reflectance in the NIR range (750–2500 nm), which helps keep the interior of buildings cool on sunny days, avoiding energy expenditure on conditioning air. When light hits, both diffuse and specular reflections act: diffuse reflection is considered to be the result of subsurface scattering. The Kubelka–Munk (K-M) transform of the measured diffuse reflectance is approximately proportional to the absorption, and hence to the concentration of light absorbent species associated to charge transfer and d-d transitions of metal ions in lattice environments or also to stretching and deformation modes of functional groups (vibrations of supported species) [

16]. Buildings contribute to climate change with their greenhouse gas emissions (e.g., 30% of the total emitted by the U.S.) associated with their primary energy consumption (36% of the total in the U.S.) [

6]. Determination of the Solar Reflectance for exterior materials (wall, roof and floor) reveals the ability of a surface to reflect solar radiation, reducing the increase in temperature caused by the incidence of solar radiation on the surface. The reflectance of a specific surface depends largely on the colour in the visible range, light colours are cool and dark colours are warm. However visible light is only a 43% of the solar light, approximatively 50% of the solar radiation falls in the near infrared radiation (NIR) range, and it is not direct dependent of the colour. Coloured surfaces should use high NIR pigment to save in air conditioning consumption and attenuate the urban heat island (UHI) effect [

17].

Photocatalysts utilize light energy to carry out oxidation and reduction reactions. When selecting a photocatalyst, the band gap of the material determines the wavelength of light that can be absorbed. Many of the photocatalysts that are commonly used have wide band gaps (>3.1 eV) and are capable of utilizing only a small portion of sunlight. In order for a photocatalyst to effectively absorb visible solar energy a maximum band gap of 3.1 eV (400 nm) is required. TiO

2 has a wide band gap (3.03 eV rutile and 3.18 eV anatase) and can therefore absorb only a small portion of sunlight. There are two approaches in which visible light irradiation can be utilized by photocatalysts: (a) to dope a UV active photocatalyst with elements which narrows the band gap (C,S,N,Si or heavy metals Co, Ag, Pt, Ru…are used as dopants for TiO

2) [

18] , (b) development of materials that have a narrow band gap which falls in the visible range, such as ferrites ZnFe

2O

4, ZnCr

2O

4 or Zn(Al,Fe)

2O

4. [

19].

In effect, ferrites offer several advantages as photocatalyst: (a) have a band gap capable of absorbing visible light, (b) the spinel crystal structure, which enhanced efficiency due to the available extra catalytic sites, (c) their magnetic properties, when ferrites are used alone as photocatalysts or in combination with others, they can therefore be easily separated from the reaction mixture, (d) to enhance the production of reactive oxygen species, oxidants such as H

2O

2 are add to the reaction mixture for a Fenton-type system, thereby its use as solid iron compounds to replace soluble Fe

2+ in traditional Fenton-type systems. Ferrites could remove some of the limitations that occur in traditional Fenton systems such as no sludge formation, operations at neutral pH, and the possibility of recycling the iron compounds, (e) combined with TiO

2, the composite photocatalyst that are formed show higher efficiency as a film in which a TiO

2 film is doped with ferrites or as a single nanoparticle with the ferrite acting as a magnetic core and the TiO

2 as a shell, the composites become effective under visible light irradiation, whereas TiO

2 alone is effective only under UV light

. [

19].

In this paper Franklinite-Zincochromite Zn(Fe,Cr)2O4, Gahnite-Zincochromite Zn(Al,Cr)2O4 and the three spinel Zn(Al,Fe,Cr)2O4 solid solutions were studied as cool ceramic pigments, following criteria of high colouring capacity and high NIR reflectance at minimum Cr amount. The resulting optimal compositions were studied as photocatalyst over Orange II azoic dye with visible light.

Author Contributions

The individual contributions are provided by the following statements “Conceptualization, Guillermo Monrós; methodology, Guillermo Monrós, Mario Llusar; software, José A. Badenes, Guillermo Monrós, Carolina Delgado; validation, Guillermo Monrós, Carolina Delgado; formal analysis, Guillermo Monrós; investigation, José A. Badenes, Guillermo Monrós, Mario Llusar; resources, José A. Badenes, Guillermo Monrós.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Carolina Delgado, Guillermo Monrós, Mario Llusar; writing—review and editing, Guillermo Monrós, Carolina Delgado; visualization, José A. Badenes, Guillermo Monrós; supervision, Guillermo Monrós; project administration, Guillermo Monrós; funding acquisition, Guillermo Monrós, Mario Llusar. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

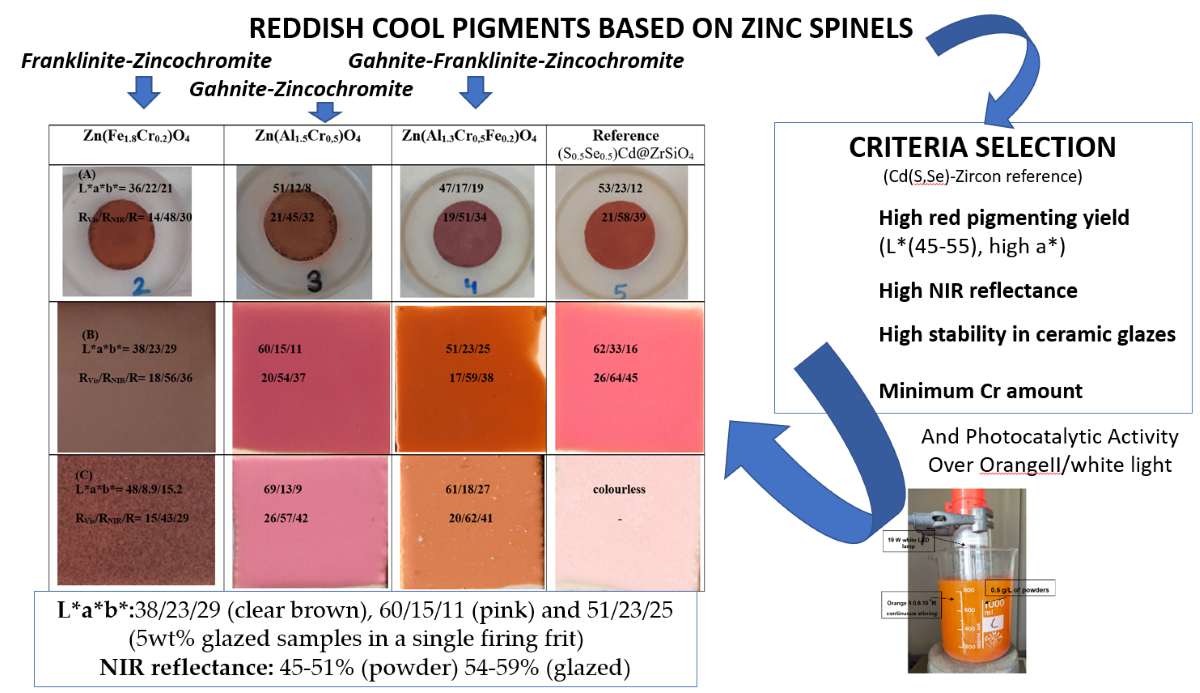

Figure 1.

Franklinite-Zincochromite Zn(Fe2-xCrx)O4 solid solutions: (A) powders synthesized at 1000ºC/3h (B) 5wt.% glazed powders in a single fire frit 1080ºC, (C) 5wt.% glazed powders in a single firing porcelain frit 1200ºC, with indication of the corresponding CIEL*a*b* values.

Figure 1.

Franklinite-Zincochromite Zn(Fe2-xCrx)O4 solid solutions: (A) powders synthesized at 1000ºC/3h (B) 5wt.% glazed powders in a single fire frit 1080ºC, (C) 5wt.% glazed powders in a single firing porcelain frit 1200ºC, with indication of the corresponding CIEL*a*b* values.

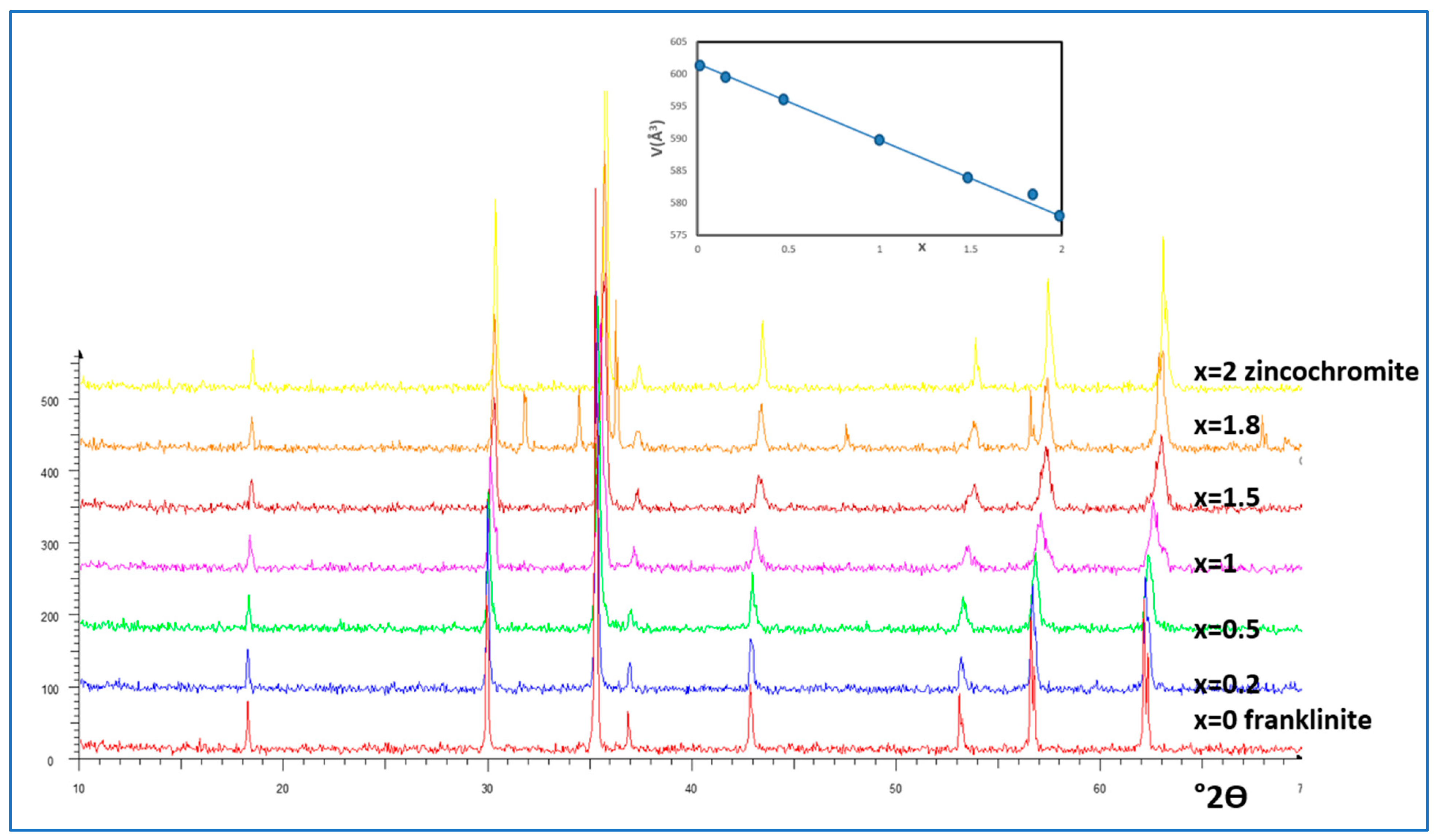

Figure 2.

X-ray diffractograms (XRD) of Franklinite-Zincochromite Zn(Fe2-xCrx)O4 solid solutions synthesized at 1000ºC/3h with the evolution of the volume of cubic cell of the corresponding spinel with x.

Figure 2.

X-ray diffractograms (XRD) of Franklinite-Zincochromite Zn(Fe2-xCrx)O4 solid solutions synthesized at 1000ºC/3h with the evolution of the volume of cubic cell of the corresponding spinel with x.

Figure 3.

UV-Vis-NIR diffuse reflectance spectra of Franklinite-Zincochromite Zn(Fe2-xCrx)O4 solid solutions; (A) fired powders 1000ºC/3h, (B) 5wt.% glazed in a single fire frit 1080ºC.

Figure 3.

UV-Vis-NIR diffuse reflectance spectra of Franklinite-Zincochromite Zn(Fe2-xCrx)O4 solid solutions; (A) fired powders 1000ºC/3h, (B) 5wt.% glazed in a single fire frit 1080ºC.

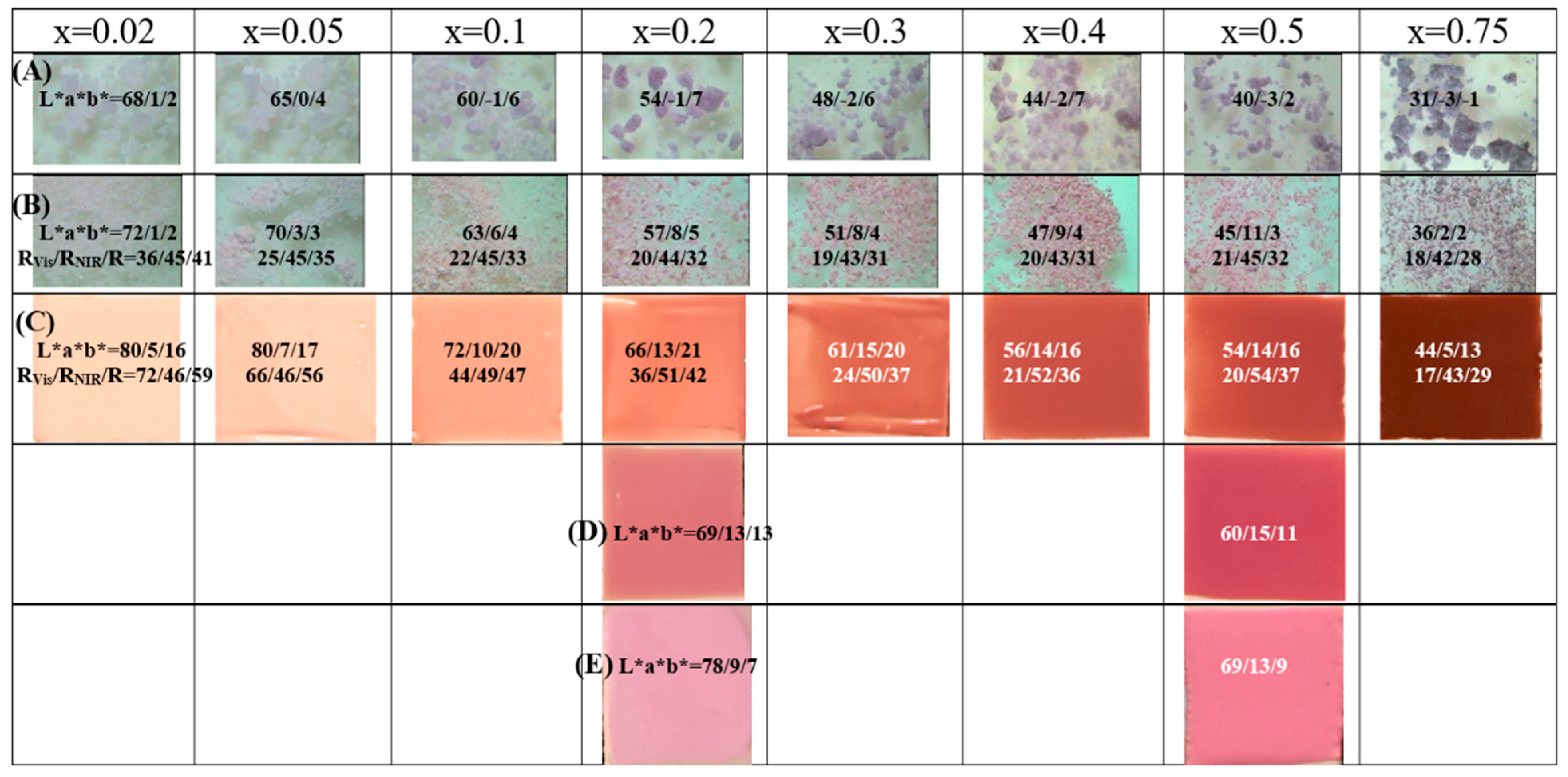

Figure 4.

Gahnite-Zincochromite Zn(Al2-xCrx)O4 solid solutions synthesized by ammonia coprecipitation: (A) raw dried gels, (B) powders fired at 1000°C/1h, (C) 5wt.% glazed in double firing frit with some lead (6wt.% PbO) 1000°C, (D) 5wt.% glazed in single firing frit 1080°C, (E) 5wt.% glazed in porcelain single firing frit 1200°C, with indication of the CIEL*a*b* values.

Figure 4.

Gahnite-Zincochromite Zn(Al2-xCrx)O4 solid solutions synthesized by ammonia coprecipitation: (A) raw dried gels, (B) powders fired at 1000°C/1h, (C) 5wt.% glazed in double firing frit with some lead (6wt.% PbO) 1000°C, (D) 5wt.% glazed in single firing frit 1080°C, (E) 5wt.% glazed in porcelain single firing frit 1200°C, with indication of the CIEL*a*b* values.

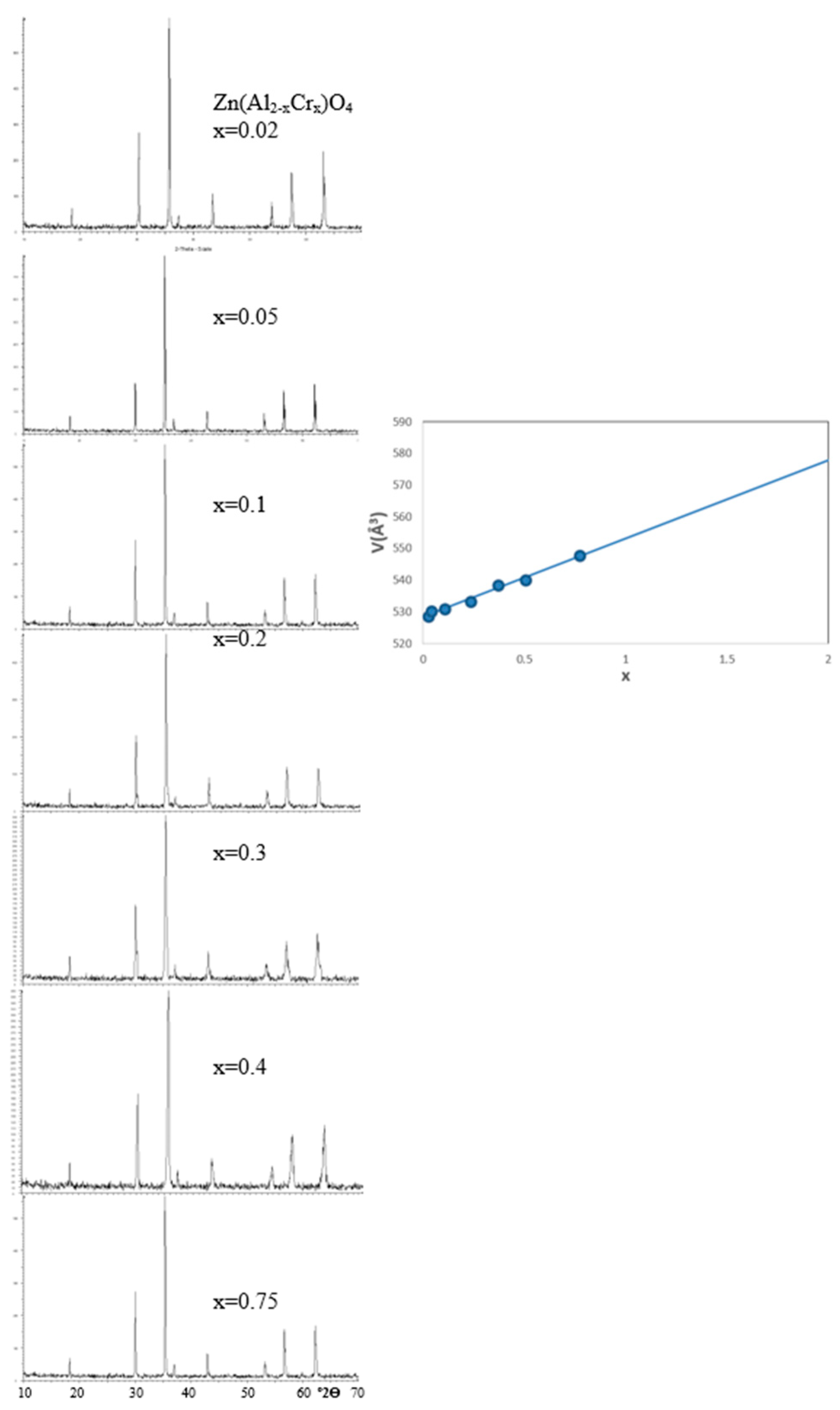

Figure 5.

X-ray diffractograms (XRD) of Zn(Al2-xCrx)O4 solid solutions synthesized at 1000ºC/1h with the evolution of the volume of cubic cell of the corresponding spinel with x.

Figure 5.

X-ray diffractograms (XRD) of Zn(Al2-xCrx)O4 solid solutions synthesized at 1000ºC/1h with the evolution of the volume of cubic cell of the corresponding spinel with x.

Figure 6.

UV-Vis-NIR spectra of Gahnite-Zincochromite Zn(Al2-xCrx)O4 solid solutions synthesized by ammonia coprecipitation fired at 1000ºC/1h.

Figure 6.

UV-Vis-NIR spectra of Gahnite-Zincochromite Zn(Al2-xCrx)O4 solid solutions synthesized by ammonia coprecipitation fired at 1000ºC/1h.

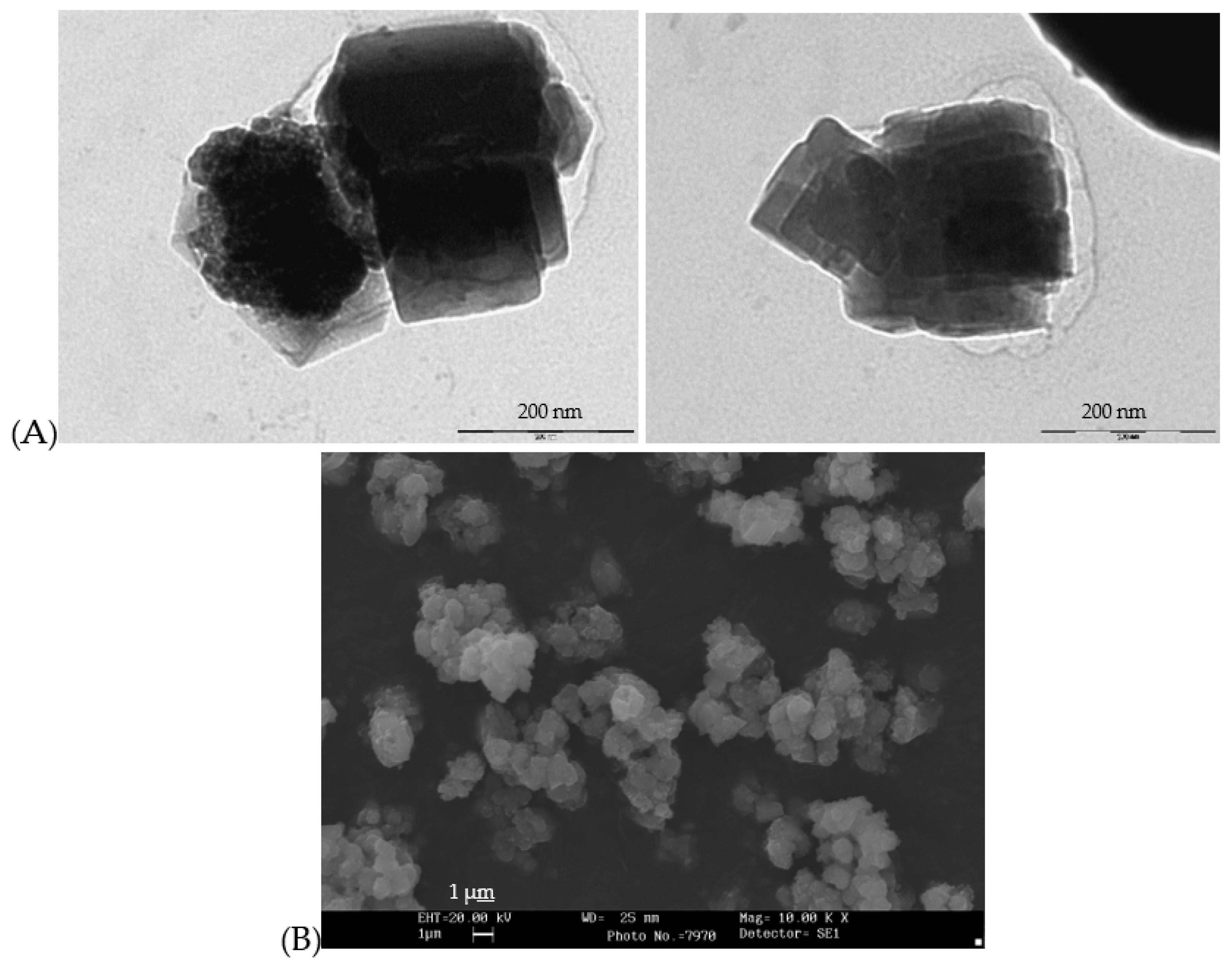

Figure 7.

(A) TEM micrographs of raw gel of coprecipitated sample Zn(Al2-xCrx)O4 x=0.5, (B) SEM and EDX composition mapping of the same sample fired at 1000°C/1h.

Figure 7.

(A) TEM micrographs of raw gel of coprecipitated sample Zn(Al2-xCrx)O4 x=0.5, (B) SEM and EDX composition mapping of the same sample fired at 1000°C/1h.

Figure 8.

Gahnite-Zincochromite-Franklinite Zn(Al1.5-xCr0,5Fex)O4 solid solutions: (A) raw dried gels, (B) fired powders 1000°C/1h, (C) 5wt.% glazed samples in a single firing frit 1080°C, (B) 5wt.% glazed samples in a porcelain single firing frit 1200°C. L*a*b* and reflectance values of samples are included.

Figure 8.

Gahnite-Zincochromite-Franklinite Zn(Al1.5-xCr0,5Fex)O4 solid solutions: (A) raw dried gels, (B) fired powders 1000°C/1h, (C) 5wt.% glazed samples in a single firing frit 1080°C, (B) 5wt.% glazed samples in a porcelain single firing frit 1200°C. L*a*b* and reflectance values of samples are included.

Figure 9.

XRD of Zn(Al1.5-xCr0,5Fex)O4 coprecipitated samples fired at 1000ºC/1h.

Figure 9.

XRD of Zn(Al1.5-xCr0,5Fex)O4 coprecipitated samples fired at 1000ºC/1h.

Figure 10.

UV-Vis-NIR diffuse reflectance spectra of Zn(Al1.5-xCr0.5Fex)O4 glazed coprecipitated samples fired at 1000ºC/1h in single firing frit 1080ºC.

Figure 10.

UV-Vis-NIR diffuse reflectance spectra of Zn(Al1.5-xCr0.5Fex)O4 glazed coprecipitated samples fired at 1000ºC/1h in single firing frit 1080ºC.

Figure 11.

(A) TEM micrographs of raw gel nanoparticles of the optimal coprecipitated sample Zn(Al1.3Cr0.5Fe0.2)O4. (B) SEM micrograph of the same sample fired at 1000ºC/1h.

Figure 11.

(A) TEM micrographs of raw gel nanoparticles of the optimal coprecipitated sample Zn(Al1.3Cr0.5Fe0.2)O4. (B) SEM micrograph of the same sample fired at 1000ºC/1h.

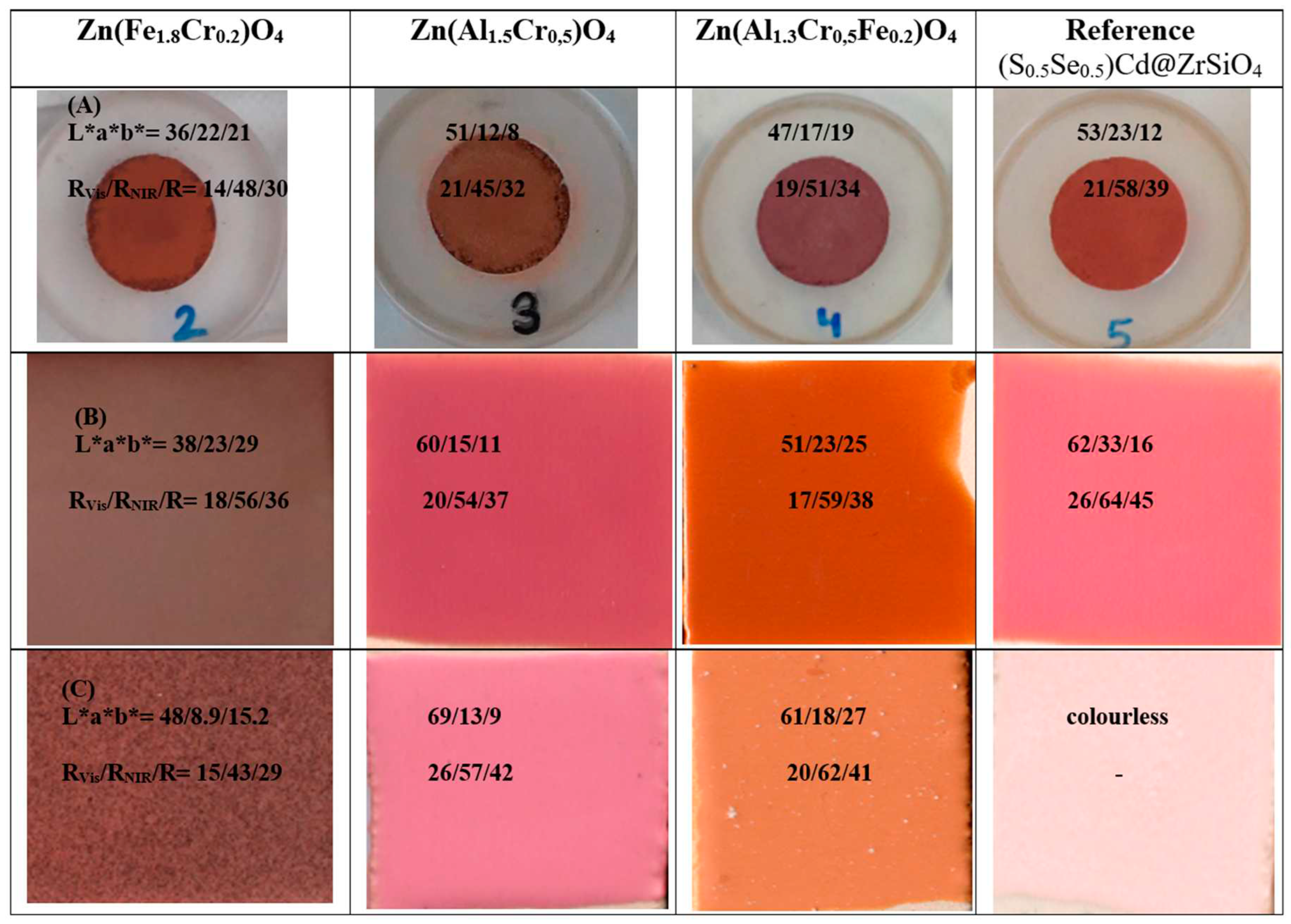

Figure 12.

Summary of the three reddish optimized samples compared with a commercial cadmium sulfoselenide encapsulated in zircon ((S0.5Se0.5)Cd@ZrSiO4): (A) powders, (b) 5wt.% glazed in single firing frit 1080°C, (C) 5wt.% glazed in porcelain single firing frit 1200°C.

Figure 12.

Summary of the three reddish optimized samples compared with a commercial cadmium sulfoselenide encapsulated in zircon ((S0.5Se0.5)Cd@ZrSiO4): (A) powders, (b) 5wt.% glazed in single firing frit 1080°C, (C) 5wt.% glazed in porcelain single firing frit 1200°C.

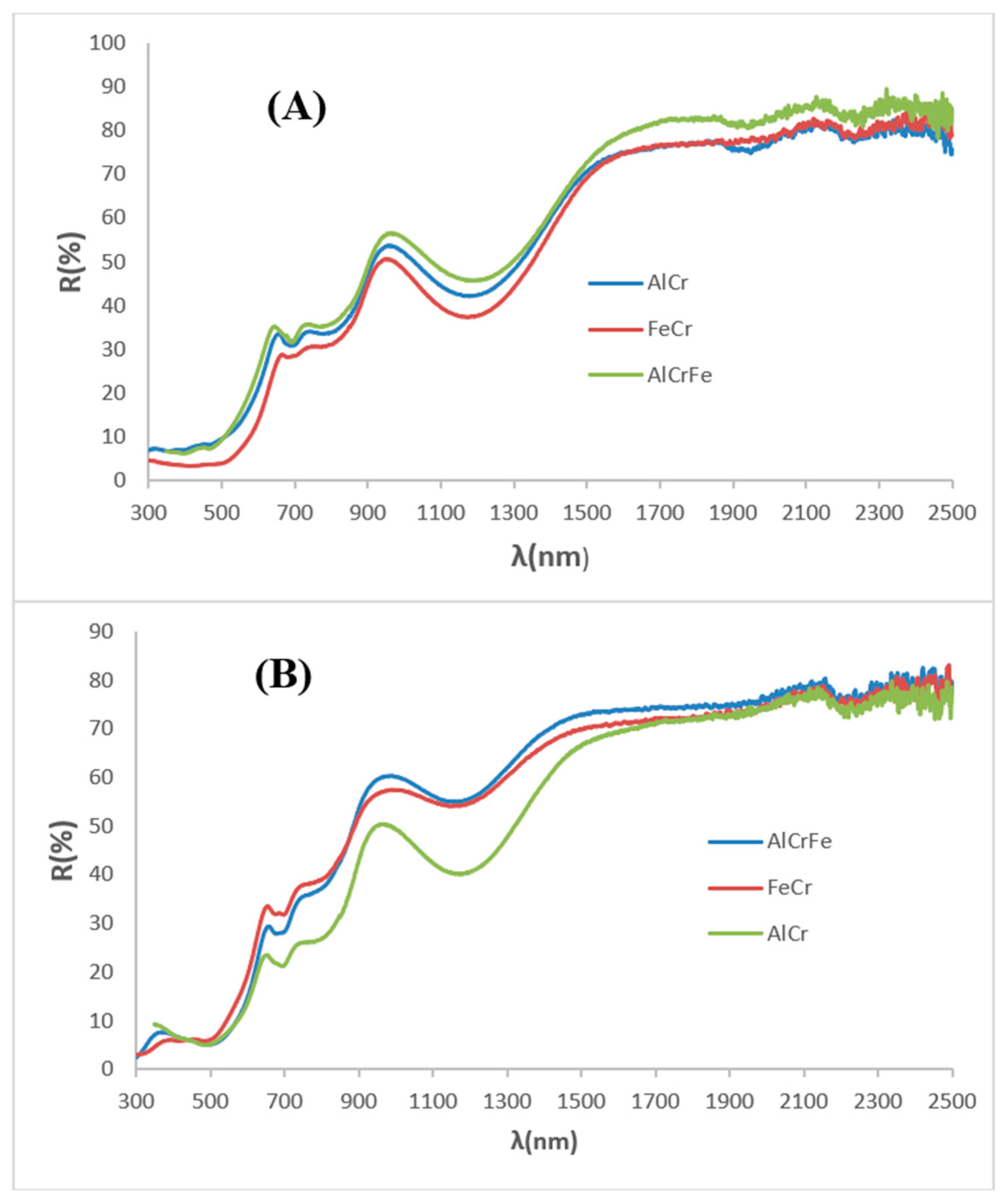

Figure 13.

UV-Vis-NIR diffuse reflectance spectra of optimized samples: (A) powders, (B) glazed samples in single firing frit.

Figure 13.

UV-Vis-NIR diffuse reflectance spectra of optimized samples: (A) powders, (B) glazed samples in single firing frit.

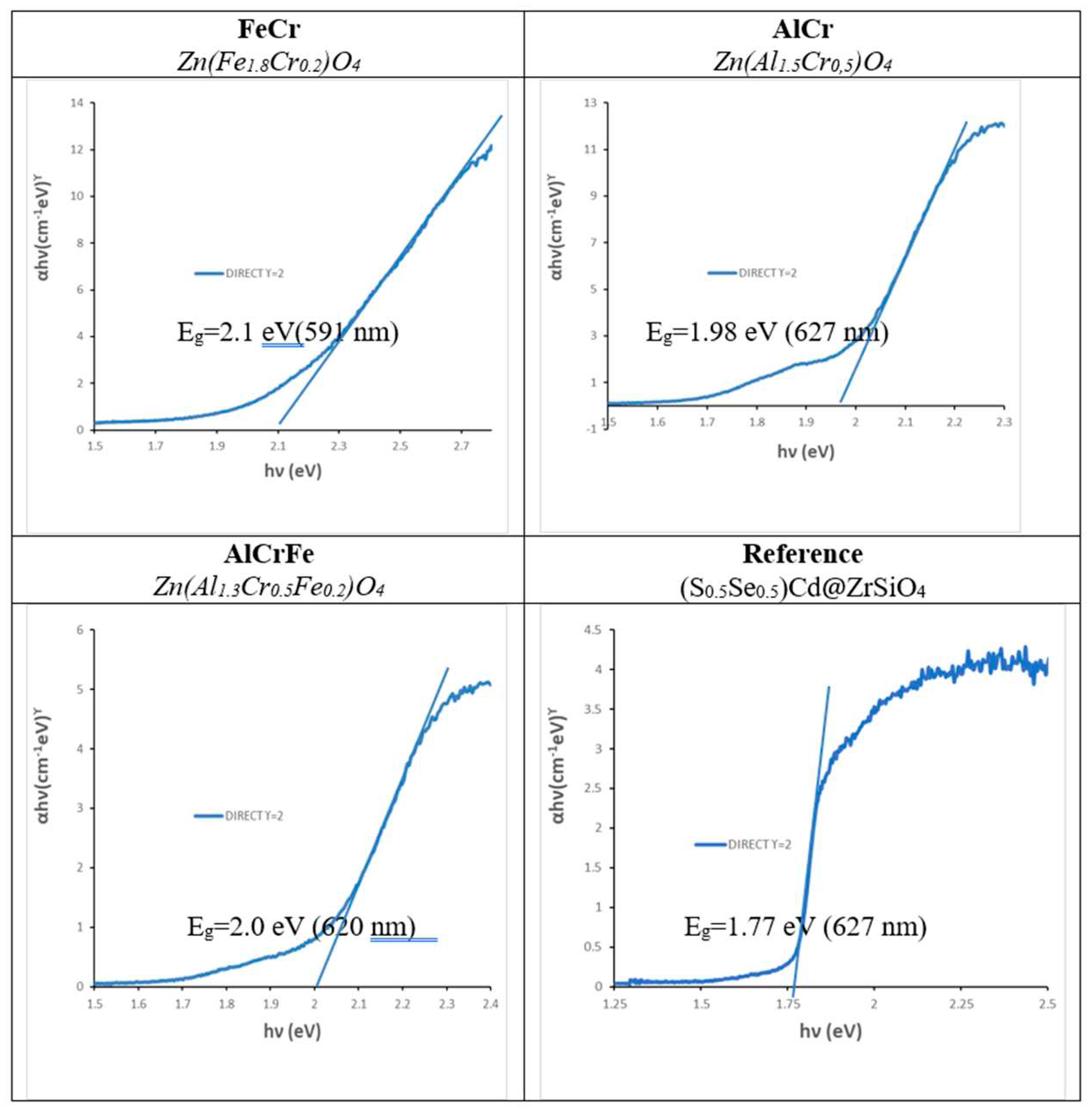

Figure 14.

Tauc plots of optimized samples.

Figure 14.

Tauc plots of optimized samples.

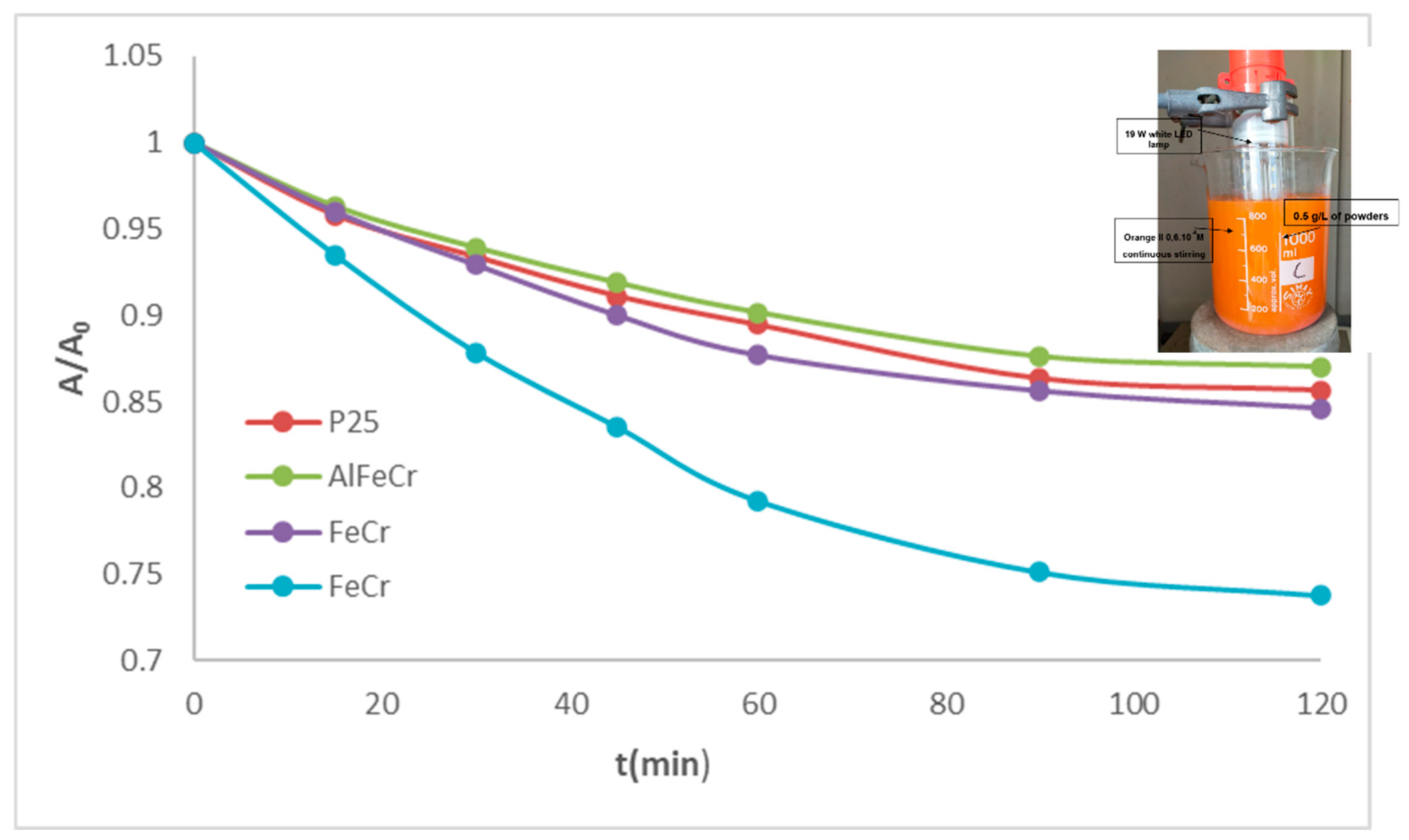

Figure 15.

Photodegradation test of Orange II with the optimized powders (image of reactor enclosed).

Figure 15.

Photodegradation test of Orange II with the optimized powders (image of reactor enclosed).

Table 1.

Photodegradation parameters of the test over Orange II of the optimized powders with visible light.

Table 1.

Photodegradation parameters of the test over Orange II of the optimized powders with visible light.

| |

Eg(eV) |

t1/2(min) |

R2

|

| P25 |

3.15 |

408 |

0.9871 |

| Zn(Fe1.8Cr0.2) |

2.10 |

213 |

0.8341 |

| Zn(Al1.5Cr0.5) |

1.98 |

346 |

0.9679 |

| Zn(Al1.3Cr0.5Fe0.2)O4

|

2.00 |

433 |

0.8177 |

| ((S0.5Se0.5)Cd@ZrSiO4

|

1.77 |

267 |

0.9870 |