Submitted:

11 December 2023

Posted:

12 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Waste Wood with Synthetic Resin

2.2. Particles from Waste Plywood

2.3. Particleboards Preparation

2.4. Particleboards Properties

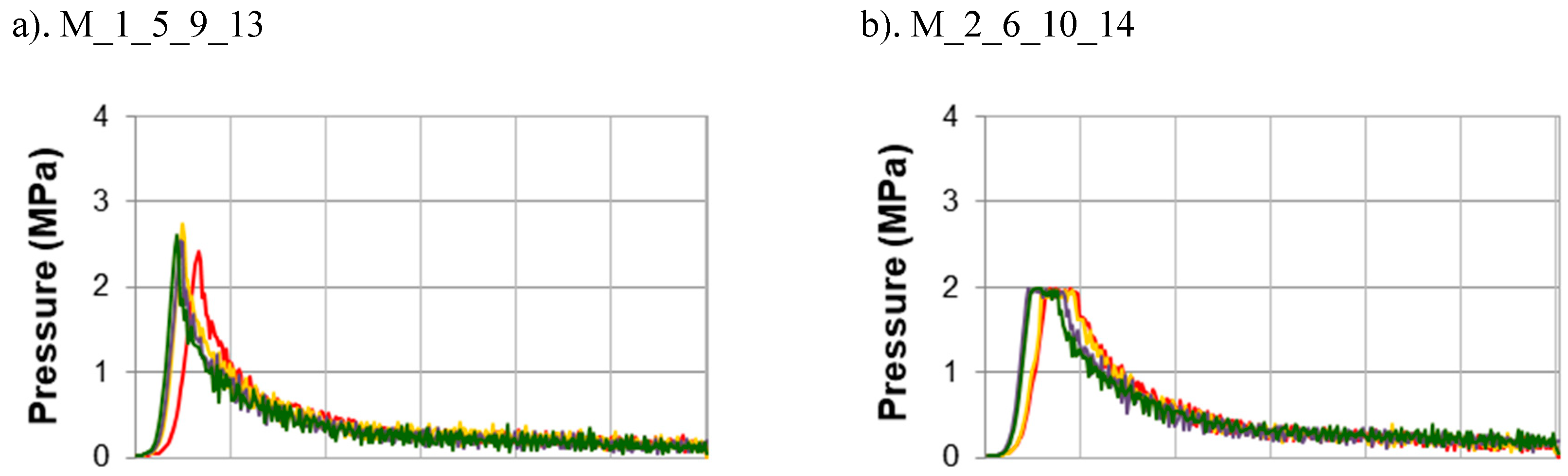

2.4.1. Pressing Process Parameters

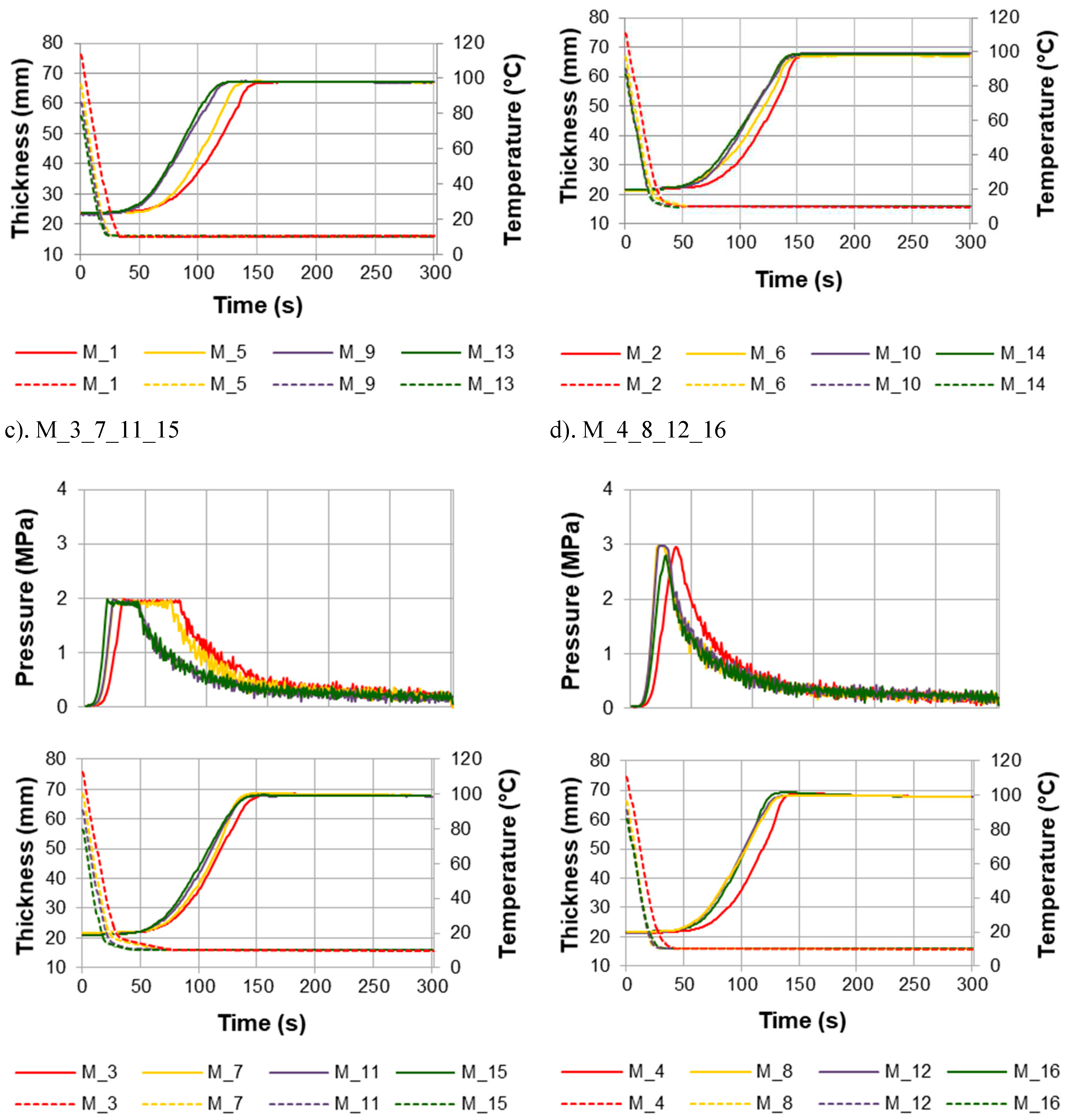

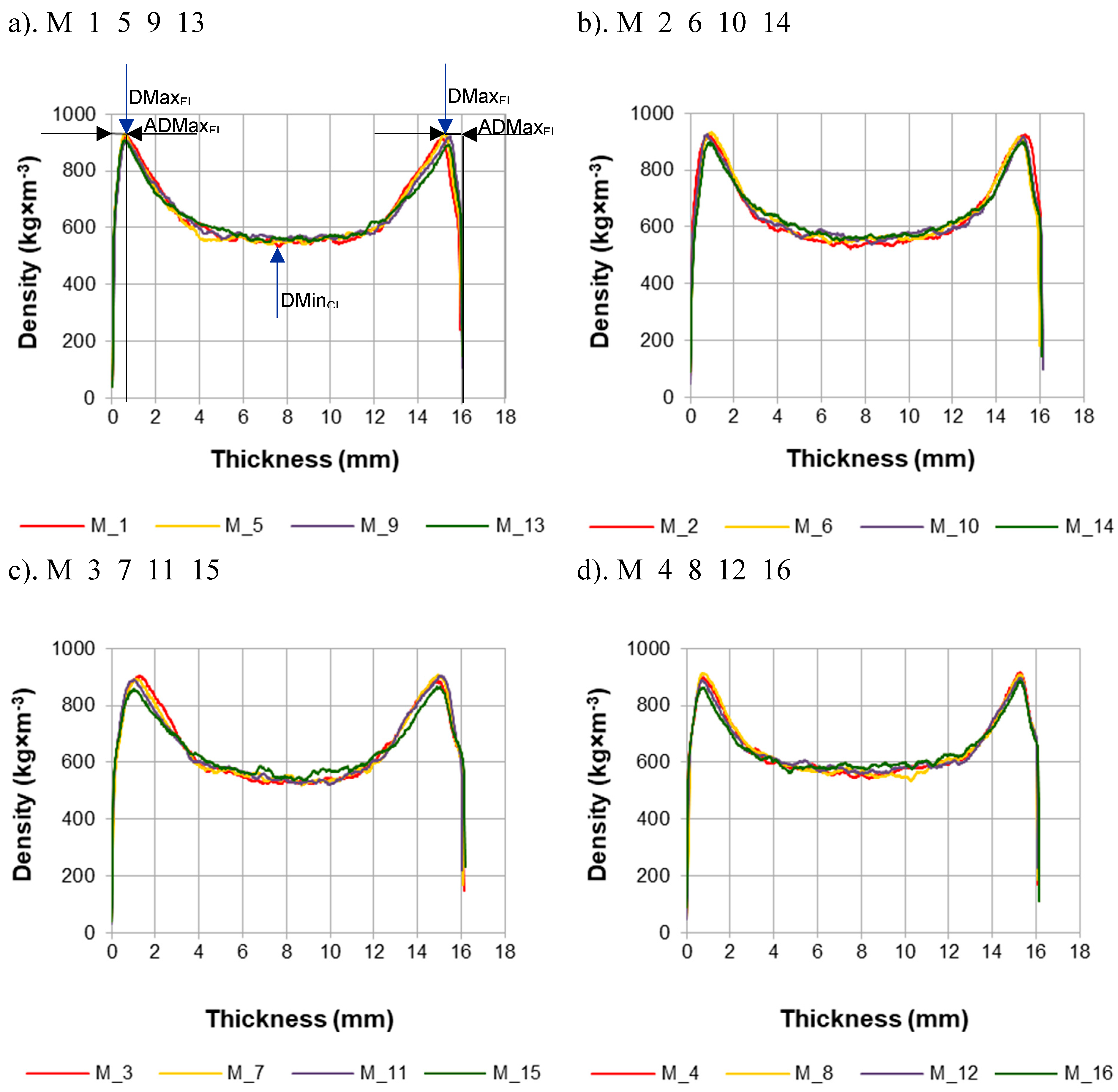

2.4.2. Density Profile

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Influence of Selected Factors on Pressing of Mats Containing PF-Covered Particles

3.2. Influence of Selected Factors on the Density Profile of Particleboards

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on waste and repealing certain Directives, OJ L 312, 22.11.2008.

- Deppe, H. - J.; Ernst K. MDF - Mitteldichte Faserplatten. DRW - Verlag Weinbrenner GmbH & Co., Leinfelden – Echterdingen, Germany, 1996.

- Baldwin, R.F. Plywood and veneer - based products: manufacturing practices. Miller Freeman Books, San Francisco, United States, 1995.

- Nicewicz, D.; Borysiuk, P.; Starecki, A. Ćwiczenia z technologii tworzyw drzewnych [Exercises in wood-based materials technology]. WULS- SGGW, Warsaw, Poland, 2009.

- Laskowska, A.; Mamiński, M. Properties of particleboard produced from post-industrial UF- and PF-bonded plywood. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products 2018, 76, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, H.; Czajka, M. The influence of compost obtained from composite wood waste and post - used wood on plant growth. 3rd European COST E31 Conference: Management of Recovered Wood. May 2 – 4, 2007, Klagenfurt, Austria, Proceedings, 293 - 307.

- Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council (EC) No. 1272/2008 of 16 December 2008, OJ L 353, 31.12.2008.

- EN 13986:2004+A1:2015. Wood-based panels for use in construction - Characteristics, evaluation of conformity and marking; European Committee for Standardization, Brussels, Belgium.

- Andrade, P.I.; Araújo, S. de O.; Neiva, D.M.; Vital, B.R.; Oliveira Carneiro, A. de C.; Gominho, J.; Pereira, H. Strength properties and dimensional stability of particleboards with different proportions of thermally treated recycled pine particles. Holzforschung 2016, 70 (5), 467 - 474, DOI: 10.1515/hf-2015-0090. [CrossRef]

- Czarnecki, R.; Dziurka, D.; Łęcka, J. The use of recycled boards as the substitute for particles in the centre layer of particleboards. Electronic Journal of Polish Agricultural Universities (EJPAU) 2003, 6(2):#01, http://www.ejpau.media.pl/volume6/issue2/wood/art-01.html, [Accessed on 6 December 2023].

- Demirkir, C.; Çolakoğlu, G. Formaldehyde emission from particleboards manufactured with waste materials from plywood industry. Holz als Roh- und Werkstoff 2007, 65 (6), 483 - 484. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T. - H.; Lin, Ch. - J.; Wang, S. - Y.; Tsai, M. - J. Characteristics of particleboard made from recycled wood-waste chips impregnated with phenol - formaldehyde resin. Building and Environment 2007, 42 (1), 189 - 195. [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, A.; Zbieć, M.; Borysiuk, P.; Kopecký, Z.; Rousek, M. Machineability of OSB boards manufactured with addition of fine fraction of waste particles. Wood machining and processing – product and tooling quality development/ed. by Górski J. and Zbieć M., WULS - SGGW Press, Warsaw, 2010, 91 – 109.

- Laskowska, A.; Mamiński, M. The properties of particles produced from waste plywood by shredding in a single-shaft shredder. Maderas. Ciencia y tecnología 2020, 22 (2), 197 - 204. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Lum, W. Ch.; Boon, J. G.; Kristak, L.; Antov, P.; Pędzik, M.; Rogoziński, T.; Taghiyari, H. R.; Lubis, M. A. R.; Fatriasari, W.; Yadav, S. M.; Chotikhun, A.; Pizzi, A. Particleboard from agricultural biomass and recycled wood waste: a review. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2022, 20, 4630–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.D.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Q.; Kawai, S. Effects of mat moisture content and press closing speed on the formation of density profile and properties of particleboard. Journal of Wood Science 1998, 44, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benthien, J.T.; Ohlmeyer, M.; Schneider, M.; Stehle, T. Experimental Determination of the Compression Resistance of Differently Shaped Wood Particles as Influencing Parameter on Wood-Reduced Particleboard Manufacturing. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products 2018, 76, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graser, M. Temperaturverlauf in industriell gefertigten Spanplatten während des Preßvorgangs, festgestellt durch Meßsonden [Thermocouple-monitored temperature distribution in particleboards manufactured under industrial pressing conditions]. Holz Zentralblatt 1962, 88 (137), 6 - 8 (Beilage 4).

- Bolton, A.J.; Humphrey, P.E.; Kavvouras, P.K. The hot pressing of dry - formed wood - based composites. Part III. Predicted vapour pressure and temperature variation with time, compared with experimental data for laboratory boards. Holzforschung 1989, 43(4), 265 – 274. [CrossRef]

- Kehr, E.; Schölzel, S. Untersuchungen über das Pressdiagramm zur Herstellung von Spanplatten [Studies on the press diagram for the production of particleboard]. Drevársky Výskum 1965, 3, 133–181. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, S.; Miyamoto, K. Effect of manufacturing parameters on the linear expansion and density profile of particleboard. Journal of Wood Science 1998, 44 (6), 444 – 450. [CrossRef]

- Wong, E. D.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Q.; Kawai, S. Formation of density profile and its effects on the properties of particleboard. Wood Science and Technology 1999, 33 (4), 327 - 340. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Wu, Q.; Lee, J.N.; Hiziroglu, S. Influence of board density, mat construction, and chip type on performance of particleboard made from eastern redcedar. Forest Products Journal 2004, 54 (12), 226 - 232.

- Gamage, N.; Setunge, S.; Jollands, M.; Hague, J. Properties of hardwood saw mill residue - based particleboards as affected by processing parameters. Industrial Crops and Products 2009, 29 (1), 248 - 254. [CrossRef]

- Murayama, K.; Kukita, K.; Kobori, H.; Kojima, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Miyamoto, K. Effect of Face-Layer Moisture Content and Face–Core–Face Ratio of Mats on the Temperature and Vapor Pressure Behavior during Hot-Pressing of Wood-Based Panel Manufacturing. Journal of Wood Science 2021, 67, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, S.; Sasaki, H. Production technology for low-density particleboard I-Forming a density gradient and its effect on board properties. Mokuzai Gakkaishi, J. Jpn. Wood Res. Soc.

- EN 827:2005 Adhesives - Determination of conventional solids content and constant mass solids content; European Committee for Standardization, Brussels, Belgium.

- Morin F., Wandelt P. (1998) Statystyczna kontrola i regulacja procesów w przemyśle celulozowopapierniczym. Cz. 3. Przegląd Papierniczy, SIGMA NOT, Montreal – Łódź.

- EN 323 (1993) Wood-based panels—Determination of density. European Committee for Standardization, Brussels.

- Li, Y.; Dai, Z.; Hu, Ch.; Tu, D.; Yun, H. Optimisation of particle distribution and performance in three-layer tubular particleboards using response surface methodology. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 108256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, P.E.; Bolton, A.J. The hot pressing of dry - formed wood - based composites. Part II. A simulation model for heat and moisture transfer, and typical results. Holzforschung 1989, 43 (3), 199 – 206.

- Hata, T.; Kawai, S.; Sasaki, H. Production of particleboard with steam-injection. Part 2: Computer simulation of temperature behavior in particle mat during hotpressing and steam-injection pressing. Wood Science and Technology 1990, 24 (1), 65 - 78.

- Thoemen, H.; Humphrey, P.E. Hot pressing of wooaHot pressing of wood - based composites: selected aspects of the physics investigated by means of simulation. In: Proceedings of the 5th European Panel Products Symposium, October 10 - 12, 2001, Llandudno Wales U.K., pp 38 – 49.

- Dukarska, D.; Rogozinski, T.; Antov, P.; Kristak, L.; Kmieciak, J. Characterisation of wood particles used in the particleboard production as a function of their moisture content. Materials 2022, 15(1), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Muehl, J.H.; Winandy, J.E. Effects of panel density and mat moisture content on processing medium density fibreboard. Forest Products Journal 2006, 56, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Keylwerth, R. Zur Mechanik der mehrschichtigen Spanplatten [On the mechanics of multi-layer particleboard]. Holz als Roh- und Werkstoff 1958, 16 (11), 419 - 430.

- Rofii, M.N.; Yamamoto, N.; Ueda, S.; Kojima, Y.; Suzuki, S. The Temperature Behaviour inside the Mat of Wood-Based Panel during Hot Pressing under Various Manufacturing Conditions. Journal of Wood Science 2014, 60, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benthien, J.T.; Ohlmeyer, M. Effects of Flat-Shaped Face Layer Particles and Core Layer Particles of Intentionally Greater Thickness on the Properties of Wood-Reduced Particleboard. Fibers 2020, 8(7), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Face Layer (ppw) |

Core Layer (ppw) |

|---|---|---|

| MUPF | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| 10% aq. (NH4)2SO4 | 3.0 | 7.0 |

| water | 12.0 | 8.0 |

| Variant | Content of the Recovered Particles (%) |

Resin Load Face_Core Layer (%) |

Face Layer Rate (%) |

Unit Pressure (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 12_10 | 50 | 3 |

| 2 | 0 | 12_10 | 35 | 2 |

| 3 | 0 | 10_8 | 50 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 | 10_8 | 35 | 3 |

| 5 | 20 | 12_10 | 50 | 3 |

| 6 | 20 | 12_10 | 35 | 2 |

| 7 | 20 | 10_8 | 50 | 2 |

| 8 | 20 | 10_8 | 35 | 3 |

| 9 | 60 | 12_10 | 50 | 3 |

| 10 | 60 | 12_10 | 35 | 2 |

| 11 | 60 | 10_8 | 50 | 2 |

| 12 | 60 | 10_8 | 35 | 3 |

| 13 | 100 | 12_10 | 50 | 3 |

| 14 | 100 | 12_10 | 35 | 2 |

| 15 | 100 | 10_8 | 50 | 2 |

| 16 | 100 | 10_8 | 35 | 3 |

| Variant | Content of the Recovered Particles (%) |

Resin Load Face_Core Layer (%) |

Face Layer Rate (%) | Unit Pressure (MPa) | DMaxFL | DMinCL | ADMaxFL | DMinCL/MD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (MPa) | (kg × m-3) | (kg × m-3) | (mm) | (-) | |

| 1 | 0 | 12_10 | 50 | 3 | 917 (7) | 522 (10) | 0.72 (0.04) | 80 (1) |

| 2 | 0 | 12_10 | 35 | 2 | 926 (3) | 523 (11) | 0.87 (0.07) | 80 (2) |

| 3 | 0 | 10_8 | 50 | 2 | 894 (4) | 519 (6) | 1.28 (0.06) | 80 (1) |

| 4 | 0 | 10_8 | 35 | 3 | 903 (5) | 542 (12) | 0.83 (0.03) | 84 (2) |

| 5 | 20 | 12_10 | 50 | 3 | 923 (12) | 529 (12) | 0.71 (0.03) | 81 (2) |

| 6 | 20 | 12_10 | 35 | 2 | 924 (10) | 532 (10) | 0.91 (0.09) | 82 (1) |

| 7 | 20 | 10_8 | 50 | 2 | 899 (3) | 520 (3) | 1.15 (0.06) | 80 (1) |

| 8 | 20 | 10_8 | 35 | 3 | 912 (6) | 543 (9) | 0.78 (0.06) | 84 (1) |

| 9 | 60 | 12_10 | 50 | 3 | 917 (4) | 544 (12) | 0.59 (0.05) | 84 (1) |

| 10 | 60 | 12_10 | 35 | 2 | 920 (4) | 541 (5) | 0.87 (0.02) | 83 (1) |

| 11 | 60 | 10_8 | 50 | 2 | 900 (10) | 522 (3) | 1.01 (0.02) | 80 (2) |

| 12 | 60 | 10_8 | 35 | 3 | 895 (3) | 556 (3) | 0.79 (0.01) | 85 (1) |

| 13 | 100 | 12_10 | 50 | 3 | 893 (7) | 552 (2) | 0.59 (0.03) | 85 (1) |

| 14 | 100 | 12_10 | 35 | 2 | 891 (11) | 556 (5) | 0.89 (0.01) | 86 (1) |

| 15 | 100 | 10_8 | 50 | 2 | 860 (6) | 542 (5) | 1.13 (0.03) | 84 (1) |

| 16 | 100 | 10_8 | 35 | 3 | 864 (22) | 564 (6) | 0.77 (0.06) | 87 (2) |

| Average value for all variants |

902 (21) | 538 (16) | 0.87 (0.19) | 83 (2) | ||||

| Properties. | Factor/Interaction | Statistical Measures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMaxFL | SS | Df | MS | F | p | X | |

| Content of the recovered particles (1) | 10499 | 3 | 3500 | 46.07 | 0.000 | 52 | |

| Resin load for face and core layer (2) | 6460 | 1 | 6460 | 85.04 | 0.000 | 32 | |

| Face layer rate (3) | 189 | 1 | 189 | 2.49 | 0.124 | 1 | |

| Unit pressure (4) | 18 | 1 | 18 | 0.24 | 0.626 | 0 | |

| (1) × (2) | 256 | 3 | 85 | 1.12 | 0.354 | 1 | |

| (1) × (3) | 195 | 3 | 65 | 0.86 | 0.473 | 1 | |

| (1) × (4) | 178 | 3 | 59 | 0.78 | 0.513 | 1 | |

| Error | 2431 | 32 | 76 | 12 | |||

| DMinCL | SS | Df | MS | F | p | X | |

| Content of the recovered particles (1) | 5242 | 3 | 1747 | 27.58 | 0.000 | 45 | |

| Resin load for face and core layer (2) | 14 | 1 | 14 | 0.22 | 0.641 | 0 | |

| Face layer rate (3) | 2168 | 1 | 2168 | 34.22 | 0.000 | 19 | |

| Unit pressure (4) | 1722 | 1 | 1722 | 27.18 | 0.000 | 15 | |

| (1) × (2) | 235 | 3 | 78 | 1.23 | 0.313 | 2 | |

| (1) × (3) | 16 | 3 | 5 | 0.08 | 0.968 | 0 | |

| (1) × (4) | 154 | 3 | 51 | 0.81 | 0.498 | 1 | |

| Error | 2027 | 32 | 63 | 18 | |||

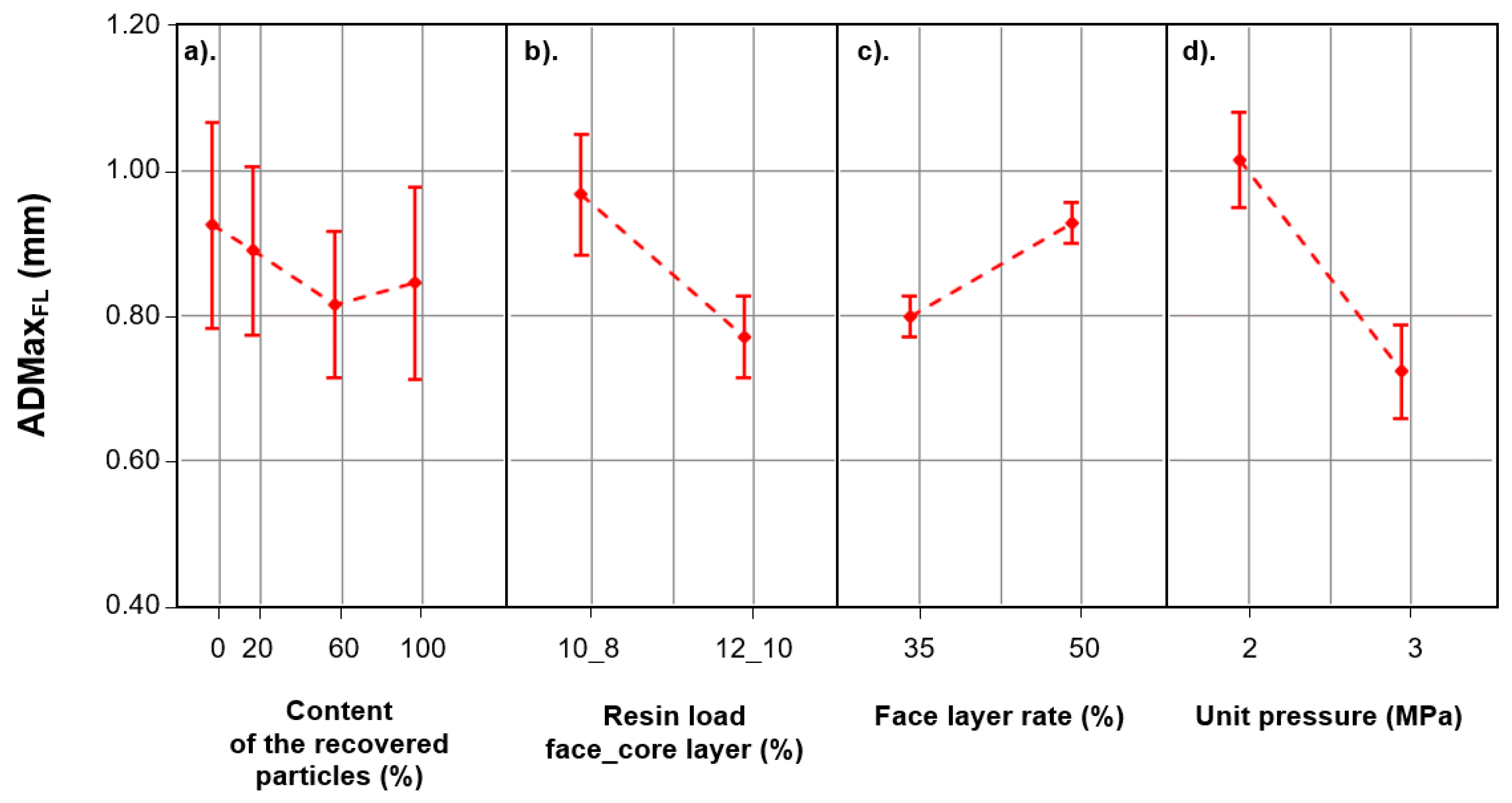

| ADMaxFL | SS | Df | MS | F | p | X | |

| Content of the recovered particles (1) | 0.086 | 3 | 0.029 | 13.35 | 0.000 | 5 | |

| Resin load for face and core layer (2) | 0.466 | 1 | 0.466 | 217.21 | 0.000 | 26 | |

| Face layer rate (3) | 0.043 | 1 | 0.043 | 19.85 | 0.000 | 2 | |

| Unit pressure (4) | 1.024 | 1 | 1.024 | 477.09 | 0.000 | 58 | |

| (1) × (2) | 0.020 | 3 | 0.007 | 3.06 | 0.042 | 1 | |

| (1) × (3) | 0.053 | 3 | 0.018 | 8.27 | 0.000 | 3 | |

| (1) × (4) | 0.010 | 3 | 0.003 | 1.51 | 0.231 | 1 | |

| Error | 0.069 | 32 | 0.002 | 4 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).