Submitted:

06 December 2023

Posted:

07 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. General Context of the Study and MSP Definition:

3. Methodology

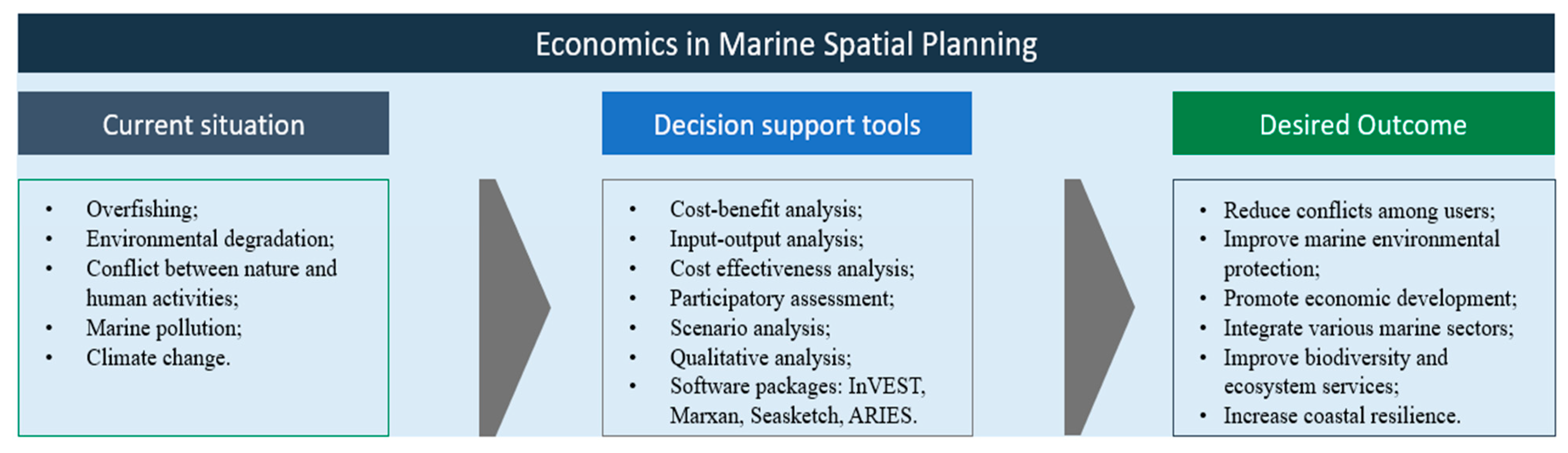

4. Economic and Social Aspects of MSP

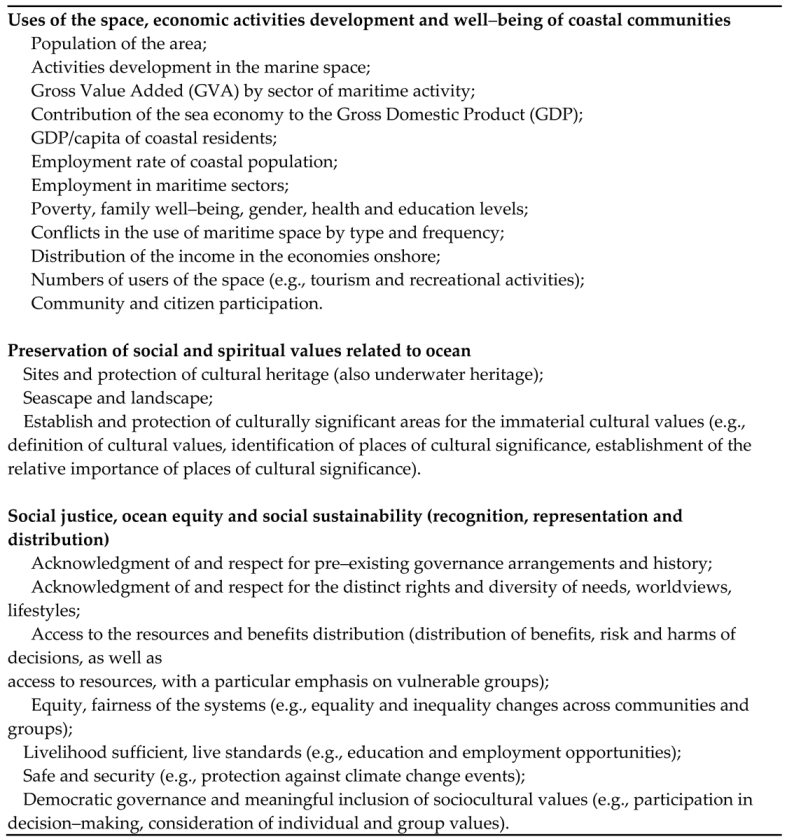

4.1. Main Socio–Economic Aspects Included in MSP

4.2. Different Uses of Socio–Economic Aspects in MSP

4.3. Socio–Economic Aspects in the MSP Decision Support Tools

5. Application of Economics to Inform MSP Decisions

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Appendix A

| Canada | The US | The UK | Belgium | Australia | Germany | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National plan | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Regional or state plan | Southern BC; Pacific North Coast; Newfoundland & Labrador shelves; Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence; and Scotian Shelf and bay of Fundy. |

Northeast Ocean Plan; Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan; Mid–Atlantic Regional Ocean Action Plan; Rhode Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan; Draft Marine Spatial Plan for Washington’s Pacific Coast and Oregon Territorial Sea Plan. |

East Inshore and East; South Inshore and South Offshore Marine Plans (England); Offshore Marine Plans (England); Scotland’s National Marine Plan; Welsh National Marine Plan and Marine Plan for Northern Ireland. |

Belgian Part of the North Sea; Flanders. | Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Zoning Plan; Marine Bioregional Plan for the North–west Marine Region; Marine Bioregional Plan for the South–west Marine Region; Marine Bioregional Plan for the North Marine Region; South–east Regional Marine Plan; Marine Bioregional Plan for the Temperate East Marine Region. |

Maritime Spatial Plan for the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the North Sea; Maritime Spatial Plan for the EEZ of the Baltic Sea; State Development Plan for Schleswig– Holstein; Spatial Planning Programme of Lower Saxony; and Spatial Development Programme of Mecklenburg– Vorpommer. |

| Responsible ministry at regional plan | Minister of Fisheries and Oceans. | Regional Advisory Committees. |

Marine Management Organization with regional marine management plans. | The Belgian minister for the North Sea | Regional Marine Plans under Commonwealth environment department. | Ministry of Energy, Infrastructure and Digitalization (Mecklenburg– Vorpommer). |

| Focus area | Environmental protection and economic development. | Manage conservation and biodiversity (e.g., Northeast Ocean plan). | Sustainable development. | Improve management of the Belgian Part of the North Sea. | Support environmental protection and maritime economy. | Support maritime economy and environmental protection. |

| Legal binding | Ocean Act is non–binding. | Mandated. | Not legally binding. | Royal Decree. | Mandated. | General Spatial Planning Act |

| Environment assessment | Cabinet Directive on Strategic Environmental Assessment. | Strategic Environmental Assessment. | Strategic Environment Assessment. |

| Country | Authority | Official terminology | Official Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | The department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) | Marine spatial planning | Marine spatial planning is a process for managing ocean spaces to achieve ecological, economic, cultural and social objectives. We advance marine spatial planning in Canada in collaboration with other federal departments, provincial, territorial and Indigenous governments as well as relevant stakeholders. |

| USA | The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) | Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning | A compilation of geospatial data to create a national framework for coastal and marine spatial planning, complete with data, tools, and information to bolster transparent, science–based decision–making to enhance regional economic, environmental, social, and cultural well–being. |

| England | Marine Management Organisation | Marine planning |

|

| Norway | Government of Norway | Integrated ocean management plans | The purpose of the management plans is to provide a framework for value creation through the sustainable use of marine natural resources and ecosystem services and at the same time maintain the structure, functioning, productivity and diversity of the ecosystems. |

| Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden | European commission4 | Marine spatial planning |

|

| Stage | Description | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Phase (e.g., Vietnam Danang Master Plan Towards 2030). | – Emerged in the late 20th century as a response to increasing conflicts over marine resource use. – Informal and ad –hoc approaches to managing marine space. – Limited integration of environmental considerations. |

– Reactive management. –Lack of coordination among stakeholders. – Focus on sector –specific regulations |

| Development Phase (e.g., Ecuador’s Galapagos Marine Reserve Management Plan). | – Late 1990s to early 2000s saw the emergence of formal MSP frameworks. – Recognition of the need for holistic and integrated management of marine space. – Growing emphasis on stakeholder engagement and participatory processes. |

– Identification of marine planning areas. – Assessment of marine resources and uses – Integration of ecological, social, and economic considerations – Stakeholder involvement and public participation. |

| Maturation Phase (e.g., Australia EEZ, including Norfolk Island). | – Mid –2000s onwards witnessed the maturation of MSP as a recognized management approach. – Increasing adoption of MSP at national and regional levels. – Emphasis on ecosystem –based management and sustainability principles |

– Integration of ecosystem –based approach. – Strategic goals and objectives for marine management. – Development of marine spatial plans and zoning systems. – Incorporation of adaptive management and monitoring. – Emphasis on cross –sectoral coordination. |

| Implementation Phase (e.g., E.g., Belize (TS) Integrated CoastalZone Management Plan, Norway (EEZ and TS). | – Current phase focused on the practical implementation of MSP. – Emphasis on plan implementation, monitoring, and evaluation. – Iterative process to learn and adapt over time. – Continued engagement with stakeholders and adaptive management |

– Implementation of marine spatial plans. – Monitoring of ecological and socioeconomic indicators. – Review and revision of plans based on feedback and changing conditions. – Integration with existing governance structures and policies. |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | Scenarios analysis |

| Uses of DST | Provides management scenarios and guide management to develop their own solutions. Provides a set of structured information to aid in decision-making and analysis. |

| Country/MSP | USA, European Union, Australia. E.g., Scenario planning has been used in Australia for MSP efforts, such as the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, which considered scenarios of climate change, population growth, and land use changes to guide conservation and management strategies. |

| Limitation | Scenario planning can be resource-intensive, requiring significant time, expertise, and financial investment to develop, analyze. Unreliable data can constrain the effectiveness of the process. |

| Data intensive level | High: Data on environmental conditions, socioeconomic indicators, policy frameworks, and other relevant factors. |

| Output variable | Plausible future scenarios, visualizations of spatial and temporal changes, impact assessments, and identification of key vulnerabilities and opportunities. These outputs inform decision-making by providing a range of potential future outcomes and their associated implications for MSP. |

| References | Hassan and Alam 2019, Beck et al. 2009, World Bank 2022b, Collie et al. 2013. |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | InVEST, complement with cost-Effectiveness analysis. |

| Uses of DST | InVEST supports the evaluation of trade-offs between different management options. |

| Country/MSP | China, Costa Rica, Colombia. E.g., InVEST has been employed in China for MSP, including the Beibu Gulf region, to evaluate the impacts of different management scenarios on multiple ecosystem services, such as fisheries production, and coastal protection. |

| Limitation | The accuracy of InVEST outputs can be influenced by the scale and resolution of the input data such as ecosystem characteristics, land use, hydrology, and socioeconomic factors. |

| Data intensive level | High: Geospatial data on ecological characteristics, economic indicators, and ecosystem services. |

| Output variable | Spatial maps and models depicting the distribution and value of ecosystem services, trade-off analyses, and valuation of ecosystem services.These outputs contribute to the identification of priority areas for conservation. |

| References | Sun et al. 2020; Halpern et al. 2010; World Bank 2021. |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | Input-output analysis. |

| Uses of DST | Quantifies the socioeconomic importance of marine sectors in the total economy of a country or region. |

| Country/MSP | German, Norway, Australia, The United States, The United Kingdom. E.g., The German Baltic Sea has utilized input-output analysis in MSP initiatives, to assess the economic linkages and impacts of marine sectors, such as fisheries, aquaculture, and tourism. |

| Limitation | Input-output analysis assumes a static economic structure, not accounting for innovation, dynamic changes, or future market conditions. Data gaps can affect the accuracy and reliability of the analysis. |

| Data intensive level | High. Detailed economic data, such as input-output tables, sectoral data on production, employment, and value-added, as well as data on intersectoral linkages and transactions. |

| Output variable | The output variables can include employment impacts, economic multipliers, value-added effects, and the assessment of direct and indirect effects of changes in the marine sector on the overall economy. |

| References | Surís-Regueiro et al. 2021 ; Huang et al. 2015. |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | The efficiency frontier. |

| Uses of DST | Allows comparison of very different ecosystem services, for example, MSP increased whale sector values by up 5% at no cost to the offshore wind energy. |

| Country/MSP | Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan (USA). |

| Limitation | The identification of the efficiency frontier can be influenced by subjective choices, such as the selection of indicators, and weighting factors. |

| Data intensive level | Medium. Data on resource allocation, management effectiveness, desired outcomes or indicators, and spatial patterns of activities or ecosystem components. |

| Output variable | Outputs may include optimal resource allocation, efficiency scores. The identification of management strategies or spatial plans that achieve desired outcomes most efficiently. |

| References | White et al. 2012. |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | Cost-benefit analysis (CBA). |

| Uses of DST | CBA provides financial and social rationale for investing in the BE. |

| Country/MSP | CBA has been applied in MSP projects. In Indonesia, NPV of an Indonesian MPA was estimated as USD 3.55.0 million. |

| Limitation | Social and ecological aspects may be challenging to monetize. |

| Data intensive level | Economic data, market prices, valuation techniques. |

| Output variable | Net present value (NPV), benefit-cost ratio, economic impact assessments. |

| References | OECD, 2017; World Bank 2022. |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | Marxan |

| Uses of DST | Designing MPAs and conservation planning. |

| Country/MSP | Marxan applied in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (Australia) to identify MPA designs that maximize conservation outcomes. |

| Limitation | Computationally intensive, sensitive to input parameters, and may not account for all stakeholder preferences. |

| Data intensive level | High: Biodiversity data, habitat maps, socioeconomic data. |

| Output variable | Optimal MPA configurations, conservation priorities, and cost-effectiveness analysis. |

| References | Watts et al. 2009. |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | Geographic Information Systems (GIS). |

| Uses of DST | Spatial data management, visualization, and analysis. |

| Country/MSP | GIS used in the MSP process of the United Kingdom’s Marine Management Organization to integrate various data layers and inform decision-making. |

| Limitation | GIS requires georeferenced data, expertise in GIS software, and data quality control. |

| Data intensive level | Geospatial data on human activities, marine features, and habitats. |

| Output variable | Maps, spatial analysis results, and visualization. |

| References | EU MSP Platform 2018. |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | SeaSketch. |

| Uses of DST | Interactive mapping and visualization tool for collaborative MSP. |

| Country/MSP | SeaSketch has been employed in the Magallanes Region (Chile), Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan (USA). |

| Limitation | The effectiveness of SeaSketch is dependent on the availability and quality of spatial data and active participation from stakeholders. |

| Data intensive level | High resolution data. Up-to-date datasets on marine ecosystems, habitats, species distributions, and socioeconomic factors such tourism revenue. |

| Output variable | Zoning plans, maps of potential impacts, cumulative impact assessments, and scenario-based visualizations. |

| References | Agardy 2015. https://legacy.seasketch.org/projects/ |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | Ecopath with Ecosim (EwE) is a software package used for ecosystem-based MSP. |

| Uses of DST | Impact assessment. EwE can simulate the effects of human activities, such as fishing, or climate change, on the marine environment and assess the potential ecological consequences. |

| Country/MSP | EwE has been utilized in South Africa for MSP, specifically in the Benguela Current region, to assess the impacts of different fishing scenarios on the ecosystem and inform management decisions. |

| Limitation | EwE requires extensive data on species interactions, population dynamics, fishing effort, and environmental variables. |

| Data intensive level | High. EwE models require comprehensive data on species composition, trophic interactions, life history parameters, fishing effort, environmental variables (e.g., temperature, productivity), and other relevant ecosystem characteristics. |

| Output variable | Estimates of species biomass, trophic interactions, fishing impacts, and indicators of ecosystem health. These outputs can guide decision-making in MSP. |

| References | Hamukuaya 2020. |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA). |

| Uses of DST | Evaluating and comparing multiple criteria and alternatives in decision-making. |

| Country/MSP | MCDA applied in New Zealand’s MSP process to assess and prioritize different management scenarios based on ecological and socioeconomic criteria. |

| Limitation | Subjective weighting of criteria, stakeholder engagement challenges, and difficulty in quantifying certain criteria. |

| Data intensive level | High: Data on ecological, economic, and social factors, stakeholder preferences, and decision criteria. |

| Output variable | Evaluation scores, ranking of alternatives, and trade-off analysis. |

| References | Tuda et al. 2013 ; Zuercher et al. 2022. |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | Marine Spatial Planning Support System (MSPSS). |

| Uses of DST | MSPSS can be used to incorporate new uses, such as renewable energy, aquaculture. |

| Country/MSP | South Africa, Australia, Norway. E.g., The South African MSPSS aids in incorporating various uses, such as offshore oil and gas exploration, marine tourism, into the MSP process. |

| Limitation | Stakeholder engagement and local context are crucial for effective use of MSPSS, and its effectiveness may vary depending on the level of stakeholder involvement. |

| Data intensive level | Regional-scale dataset such as spatial data on ecological features (habitats, species distributions), socioeconomic factors (e.g., human activities), and governance aspects (e.g., regulations, management measures). |

| Output variable | Spatial allocation of different uses (e.g., areas offshore wind farms). Quantitative assessments of the impacts of uses on ecological, socioeconomic, and governance factors. |

| References | Maes et al. 2005; Ehler and Douvere 2007. |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | Probabilistic risk assessment (PRA), sensitivity analysis aiding environment risk assessment. |

| Uses of DST | Identifies the types of incentives needed for motivating highercompliance of regulations.Identify and quantify potential risks associated with marine activities, such as oil and gas exploration, shipping, or renewable energy installations. |

| Country/MSP | MSP scenarios in the German EEZ of the North Sea. Gulf of Mexico (USA) has employed PRA to evaluate risks from offshore energy development, spills, and natural hazards, and to inform decision-making processes for resource management. |

| Limitation | May not fully capture spatial and temporal variations in risks, particularly at finer scales or when considering dynamic changes in environmental conditions and human activities. |

| Data intensive level | Data on hazards (e.g., pollution sources), exposure (e.g., spatial distribution of activities), vulnerability (e.g., ecological sensitivity, socio-economic factors), and potential impacts. |

| Output variable | Risk estimates, probability distributions, sensitivity indices, and visualizations of potential impacts and their uncertainties. These outputs guide the development of risk management strategies. |

| References | Frazao Santo et al. 2013; Stelzenmuller et al. 2015. |

| Economic decision support tools (DST) | Adaptive management (AM). |

| Uses of DST | AM helps reduce risks by allowing for adjustments and course corrections in response to unforeseen or unexpected outcomes. |

| Country/MSP | The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (Australia), the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (USA), and The Netherlands Integrated Management Plan for the North Sea. |

| Limitation | Adaptive management requires ongoing monitoring, data collection, analysis, and stakeholder engagement, which can be time-consuming and resource-intensive. |

| Data intensive level | Data or information gathered through stakeholder engagement processes, such as surveys, interviews, or participatory mapping. |

| Output variable | Publication of new scientific knowledge, best practices, or guidelines that emerge from the adaptive management process. |

| References | Ehler and Douvere 2009. |

Appendix B. MSP case studies

| 1 |

Source: Authors creation based on literature reviewed. |

| 2 |

Source: Authors creation based on literature reviewed. |

| 3 |

For each definition, the source is provided in the hyperlink attached to the Authority. |

| 4 |

For an update on the adoption of MSP plans in each of the European Commission’s member countries, please consult this link .. |

References

- Agardy, T. (2015). Marine protected areas and marine spatial planning. In H. D. Smith, J. L. Suaréz de Vivero, & T. Agardy (Eds.), Routledge handbook of ocean resources and management (Chapter 31). Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Albotoush, R., and Shau– Hwai, A.T. (2023). Overcoming worldwide Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) challenges through standardizing management authority. Ocean and Coastal Management 235, 106481. [CrossRef]

- Alpizar, F., et al. (2020). Mainstreaming of Natural Capital and Biodiversity into Planning and Decision–Making: Cases from Latin America and the Caribbean. Series. IDB–MG–823: Inter–American Development Bank.

- Ansong, J.O., McElduff, L., and Ritchie, H. (2021). Institutional integration in transboundary marine spatial planning: A theory–based evaluative framework for practice. Ocean and Coastal Management 202, 105430. [CrossRef]

- Arkema, K.K., et al. (2015). Embedding ecosystem services in coastal planning leads to better outcomes for people and nature, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 7390–7395. [CrossRef]

- Australia National Oceans Office (2004). South–east Regional Marine Plan – Implementing Australia’s oceans policy in the South–east Marine Region. Accessed on April 2, 2023 from https://parksaustralia.gov.au/marine/pub/scientific-publications/archive/sermp.pdf.

- Baker, S., and Constant, N.L. (2020). Epistemic justice and the integration of local ecological knowledge for marine conservation: Lessons from the Seychelles. Marine Policy 117, 103921. [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.W, Z. Ferdaña, J. Kachmar, K. Morrison, K., and Taylor, P. (2009). Best Practices for Marine Spatial Planning. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, VA.

- Bennett, et al. (2020). Social equity and marine protected areas: Perceptions of small–scale fishermen in the Mediterranean Sea. Biological Conservation 244, 108531. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J., et al. (2021). Advancing Social Equity in and Through Marine Conservation. Frontiers in Marine Science 8, 711538. [CrossRef]

- Borges, R., Eyzaguirre, I., Barboza, R. S. L., and Glaser, M. (2020). Systematic review of spatial planning and marine protected areas: a Brazilian perspective. Frontiers in Marine Science 7, 499. [CrossRef]

- Buhl–Mortensen, L., et al. (2017). Maritime ecosystem–based management in practice: Lessons learned from the application of a generic spatial planning framework in Europe. Marine Policy 75, 174–186. [CrossRef]

- Chalastani, V.I., Tsoukala, VK., Coccossis, H., Duarte, C.M. (2021). A bibliometric assessment of progress in marine spatial planning, Marine Policy 127, 104329. [CrossRef]

- crowder, A., Schoukens, H., and Maes, F. (2012). Conflicting interests between offshore wind farm development and the designation of a Natura 2000 site: riding a Belgian policy rollercoaster? Prog. Mar. Conserv. Eur. 149–156.

- Coudenys, H., Barbery, S., Depestel, N., Traen, S., Pirlet, H., (2013). Social and economic environment. In: Pirlet, H., Verleye, T., Lescrauwaet, A.K., Mees, J. (Eds.), Compendium for Coast and Sea 2015: An integrated knowledge document about the socioeconomic, environmental and institutional aspects of the coast and sea in Flanders and Belgium. Ostend, Belgium, p. 187–200.

- Craig, R.K. (2019). Fostering adaptive marine aquaculture through procedural innovation in marine spatial planning. Marine Policy 110, 103555. [CrossRef]

- Crowder, L., and Norse, E. (2008). Essential ecological insights for marine ecosystem–based management and marine spatial planning. Marine Policy 32,772–778. [CrossRef]

- Dahmouni, I., & Sumaila, R. U. (2023). A dynamic game model for no-take marine reserves. Ecological Modelling, 481, 110360. [CrossRef]

- Day, J. (2016). The great barrier reef marine park: The grandfather of modern MPAs. Big, bold and blue: Lessons from Australia’s marine protected areas, 65–97.

- Depellegrin, et al. (2021). Current status, advancements and development needs of geospatial decision support tools for marine spatial planning in European seas. Ocean and Coastal Management 209, 105644. [CrossRef]

- Douvere, F. (2009). The importance of marine spatial planning in advancing ecosystem–based sea use management. Marine Policy 32, 762–771. [CrossRef]

- Douvere, F., and Ehler, C. (2009). New perspectives on sea use management: Initial findings from European experience with marine spatial planning. Journal of Environmental Management 90, 77–88. [CrossRef]

- Ehler, C. (2021). Two decades of progress in Marine Spatial Planning. Marine Policy 132, 104134. [CrossRef]

- Ehler, C., and Douvere, F. (2009). Marine Spatial Planning: a step–by–step approach toward ecosystem–based management. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission and Man and the Biosphere Programme. IOC Manual and Guides No. 53, ICAM Dossier No. 6. Paris: UNESCO.

- EU MSP Platform (2018). Available online at https://maritime-spatial-planning.ec.europa.eu/practices/gis-tools-msp-and-management.

- European Commission (2008). Roadmap for maritime spatial planning: achieving common principles in the EU. Brussels: communication from the commission, 791, p. 11.

- European Commission. (2020). Study on the economic impact of Maritime Spatial Planning. Executive Agency for Small and Medium–sized Enterprises (EASME).

- Fernandes, M.L., Larruga, J.S., and Alves, F.L. (2022). Spatial characterization of marine socio–ecological systems: A Portuguese case study. Journal of Cleaner Production 363, 132381. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M., Johnson, D., Pereira da Silva. C., Ramos T.B. (2018). Developing a performance evaluation mechanism for Portuguese marine spatial planning using a participatory approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 180, 913–923. [CrossRef]

- Flannery, W., Ellis, G., Ellis, G., Flannery, W., Nursey–Bray, M., van Tatenhove, J.P.M., Kelly, C., Coffen–Smout, S., Fairgrieve, R., Knol, M., Jentoft, S., Bacon, D., and O’Hagan, A.M. (2016). Exploring the winners and losers of marine environmental governance/Marine spatial planning: cui bono?/“More than fishy business”: epistemology, integration and conflict in marine spatial planning/Marine spatial planning: power and scaping/Surely not all. Planning Theory & Practice 17 (1), 121–151. [CrossRef]

- Flannery, W., Healy, N., and Luna, M. (2018). Exclusion and non–participation in Marine Spatial Planning. Marine Policy 88, 32–40. [CrossRef]

- Frazao Santo, CF., Michel J., Neves, M., Janeiro, J. (2013). Marine spatial planning and oil spill risk analysis: Finding common grounds. Marine Pollution Bulletin 1, 73–81. [CrossRef]

- Frazão–Santos, C., et al. (2019). Marine Spatial Planning. World Seas: An environmental evaluation.

- Frederiksen, P., Morf, A., von Thenen, M., Armoskaite, A., Luhtala, H., Schiele, K.S., Strake, S., Hansen, H.S. (2021). Proposing an ecosystem services–based framework to assess sustainability impacts of maritime spatial plans (MSP–SA). Ocean and Coastal Management 208, 105577. [CrossRef]

- Friends of Ocean Action. (2020). The Ocean Finance Handbook: Increasing finance for a healthy ocean. Ocean Fox Advisory and Friends of Ocean Action.

- Friess, B., and Gremaud–Colombier, M. (2021). Policy outlook: Recent evolutions of maritime spatial planning in the European Union. Marine Policy 132, 103428. [CrossRef]

- Gee, K., et al. (2017). Identifying culturally significant areas for marine spatial planning. Ocean & Coastal Management 136, 139–147. [CrossRef]

- GHK Consulting (2004). Potential Benefits of Marine Spatial Planning to Economic Activity in the UK. Accessed on April 4, 2023, from https://www.rspb.org.uk/globalassets/downloads/documents/positions/marine/potential-benefits-of-marine-spatial-planning-to-economic-activity-in-the-uk.pdf.

- Gilek, M., Armoskaite, A., Gee, K., Saunders, F., Tafon, R., and Zaucha, J. (2021). In search of social sustainability in marine spatial planning: A review of scientific literature published 2005–2020. Ocean and Coastal Management 208, 105618. [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, P.M., and Laffoley, D. (2008). Key elements and steps in the process of developing ecosystem–based marine spatial planning, Marine Policy 32, 787–796. [CrossRef]

- Gómez–Ballesteros, M., et al. (2021). Transboundary cooperation and mechanisms for Maritime Spatial Planning implementation. SIMNORAT project. Marine Policy 127,104434. [CrossRef]

- Grimmel, H., Calado, H., Fonseca, C., Suárez de Vivero, J.L. (2019). Integration of the social dimension into marine spatial planning – Theoretical aspects and recommendations. Ocean and Coastal Management 173, 139–147. [CrossRef]

- Halpern, B., Lester, S., and Kellner, J. (2010). Spillover from marine reserves and the replenishment of fished stocks. Environmental Conservation 36, 268–276. [CrossRef]

- Hassan D., and Alam A. (2019). Marine Spatial Planning and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975: An Evaluation. Ocean and Coastal Management 167, 188–196. [CrossRef]

- Hassler, B. et al. (2018). Collective action and agency in Baltic Sea marine spatial planning: Transnational policy coordination in the promotion of regional coherence. Marine Policy 92, 138–147. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO (IOC–UNESCO). (2017). MSP around the globe. http://msp.ioc-unesco.org/world-applications (Accessed 15.11.17). UNESCO.

- Issifu, I., Dahmouni, I., Deffor, E.W., & Sumaila, UR. (2023). Diversity, equity and inclusion in the blue economy: Why they matter and how do we achieve them? Frontiers in Political Science 4,1067481. [CrossRef]

- Issifu, I., Deffor, E. W., Deyshappriya, N. P. R., Dahmouni, I., & Sumaila, U. R. (2022). Drivers of Seafood Consumption at Different Geographical Scales. Journal of Sustainability Research, 4(3). [CrossRef]

- Jones P.J.S., Lieberknecht LM., and Qiu W. (2016). Marine spatial planning in reality: Introduction to case studies and discussion of findings. Marine Policy 71, 256–264. [CrossRef]

- Kirkfeldt, T.S., van Tatenhove, J.P.M., Nielsen, H.N., and Larsen, S.V. (2020). An ocean of ambiguity in Northern European marine spatial planning policy designs. Marine Policy 119, 104063. [CrossRef]

- Kull, M., Moodie, J.R., Thomas, H.L., Mendez–Roldan, S., Giacometti, A., Morf, A., and Isaksson, I. (2021). International good practices for facilitating transboundary collaboration in Marine Spatial Planning. Marine Policy 132, 103492. [CrossRef]

- Lagabrielle, E., Lombard, A.T., Harris, J.M., Livingstone, T– C. (2018). Multi–scale multi–level marine spatial planning: A novel methodological approach applied in South Africa. PLoS ONE 13(7): e0192582. [CrossRef]

- Lester, S.E., Costello, C., Halpern, B.S., Gaines, S.D., White, C., and Barth, J.A. (2013). Evaluating trade–offs among ecosystem services to inform marine spatial planning, Marine Policy 38, 80–89. [CrossRef]

- Longato, D., Cortinovis, C., Albert, C., and Geneletti, D. (2021). Practical applications of ecosystem services in spatial planning: Lessons learned from a systematic literature review. Environmental Science and Policy 119, 72–84. [CrossRef]

- Maes, F., De Batist, M., Van Lancker, V., Leroy, D., Vincx, M., 2005. Towards a Spatial Structure Plan for Sustainable Management of the Sea, SPSD–II/Mixed Research Actions, Belgian Science Policy Office, pp. 39–298.

- Maini, B., Blythe, J.L., Darling, E.S., and Gurney, G.G. (2023). Charting the value and limits of other effective conservation measures (OECMs) for marine conservation: A Delphi study. Marine Policy 147,105350. [CrossRef]

- Nursey–Bray, M., Gillanders, B.M., and Maher, J. (2021). Developing indicators for adaptive capacity for multiple use coastal regions: Insights from the Spencer Gulf, South Australia. Ocean and Coastal Management 211, 105727. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2017) Marine protected areas: Economics, management and effective policy mixes, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Parliament of the republic of South Africa 2021. Operation Phakisa initiatives that are central to the mandate of the department of forestry, fisheries and the environment. RESEARCH BRIEF (pmg.org.za).

- Pecceu, E., Hostens, K., and Mae, F. (2016). Governance analysis of MPAs in the Belgian part of the North Sea. Marine Policy 71, 265–274. [CrossRef]

- Pinarbasi, K., Galparsoro, I., Alloncle, N., Quemmerais, F., and Borja, A. (2020). Key issues for a transboundary and ecosystem–based maritime spatial planning in the Bay of Biscay. Marine Policy 120, 104131. [CrossRef]

- Pınarbaşı, K., Galparsoro, I., Borja, A., Stelzenmüller, V., Ehler, CN., Antje Gimpel, A. (2017). Decision support tools in marine spatial planning: Present applications, gaps and future perspectives. Marine Policy 83, 83–91. [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, R., and Douvere, F. (2008). The engagement of stakeholders in the marine spatial planning process, Marine Policy 32, 816–822. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez–Monsalve, P., and van Tatenhove, J. (2020). Mechanisms of power in maritime spatial planning processes in Denmark. Ocean and Coastal Management 198, 105367. [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, A., et al. (2015). InVEST Scenarios Case Study: Coastal Belize. Natural Capital Project. Accessed on April 1, 2023, from https://naturalcapitalproject.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/belize_invest_scenarios_case_study.pdf.

- Saunders, F., Gilek, M., Ikauniece, A., Tafon, R.V., Gee, K., and Zauch J. (2020). Theorizing Social Sustainability and Justice in Marine Spatial Planning: Democracy, Diversity, and Equity. Sustainability, 12, 2560. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, N., and Barale, V. (2011). Maritime Spatial Planning: Opportunities and challenges in the framework of the EU Integrated Maritime Policy. Coastal Conservation 15, 237–245. [CrossRef]

- Sumaila, U. R., Walsh, M., & Hoareau, K. (2022). Financing a sustainable ocean economy. Nature Communication, 12 (3259), veröffentlicht 08.06. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sumaila, U. R. (2021). Infinity fish: Economics and the future of fish and fisheries. Academic Press.

- Sumaila, U. R., Lam, V. W., Miller, D. D., Teh, L., Watson, R. A., Zeller, D., ... & Pauly, D. (2015). Winners and losers in a world where the high seas is closed to fishing. Scientific reports, 5(1), 8481. [CrossRef]

- Sun X., Zhang L., Lu S–Y., et al. (2020). A new model for evaluating sustainable utilization of coastline integrating economic output and ecological impact: A case study of coastal areas in Beibu Gulf, China. Journal of Cleaner Production 271,122423. [CrossRef]

- Surís–Regueiro, J.C., Santiago, J.L., González–Martínez, X.M., and Garza–Gil, M.D. (2021a). Estimating economic impacts linked to Marine Spatial Planning with input–output techniques. Application to three case studies. Marine Policy 129, 104541. [CrossRef]

- Surís–Regueiro, J.C., Santiago, J.L., González–Martínez, X.M., and Garza–Gil, M.D. (2021b). An applied framework to estimate the direct economic impact of Marine Spatial Planning, Marine Policy, 127, 104443. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M., et al. (2015). Economic analysis to Support Marine Spatial Planning in Washington. Washington Coastal Marine Advisory Council.

- The World Bank. (2022). Applying Economic Analysis to Marine Spatial Planning. Accessed on March 22, 2023 from https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099515006062210102/pdf/P1750970bba3a60940831205d770baece51.pdf.

- Tuda A.O., Stevens T.F., Rodwell L.D. (2013). Resolving coastal conflicts using marine spatial planning. Journal of Environmental Management 133, 59–68. [CrossRef]

- Waldron A., et al. (2020). Protecting 30% of the planet for nature: costs, benefits and economic implications. Campaign for Nature. Accessed on April 1, 2023, from https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/326470/Waldron_Report_FINAL_sml.pdf?sequence=1.

- White, C., Halpern, B.S., and Kappel, C.V. (2012). Ecosystem service tradeoff analysis reveals the value of marine spatial planning for multiple oceans uses, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 4696–4701. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).