1. Introduction

Climate forecasting studies estimate that permafrost thaw could contribute anywhere between 20 to 500 Gt of CO

2-eq by 2100 ([

1,

2,

3,

4]). These estimates varied in the phenomenon they modeled, how that phenomenon was modeled, and assumptions of warming trends, therefore explaining the wide range of predictions. Regardless of these differences, a crucial variable in all forecasts is the active layer thickness (ALT), which describes the topmost layer of permafrost subject to annual freeze and thaw. Warmer temperatures lead to deeper active layers. Organic carbon is distributed throughout the soil column, meaning deeper active layers permit microbacteria to process more carbon and emit more greenhouse gases. For more background on permafrost carbon cycles, the reader is referred to [

5].

2. Background

2.1. ReSALT Description

The remotely sensed active layer thickness (ReSALT) algorithm was introduced to model ALT with broad spatial coverage while preserving heterogeneous predictive power [

6]. Without remote sensing, our understanding of permafrost thaw is constrained to sparse in-situ observations. Given the vast extent of permafrost, it would be incredibly useful if remote sensing could accurately monitor ALT. ReSALT leverages a technique known as interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) to create its predictions. For background information on InSAR, the reader is referred to [

7]. For the purpose of analysis in this paper, an InSAR measurement should be thought of as having three properties: i) the date of the reference SAR acquisition, ii) the date of the secondary SAR acquisition, and iii) an image containing ground subsidence

1 per pixel. Specifically, if the ground position is measured as

in an unchanging, earth-centered reference frame and the positive direction points towards the Earth’s center, then the image will consist of

per pixel.

ReSALT has been used in several studies since its conception, such as in [

6,

8,

9,

10]. While it has demonstrated promising results, there is room for improvement. For example, the Permafrost Dynamics Observatory project reported a root-mean-square-error (RMSE) of 15.18 cm in ReSALT predicted vs in-situ ALTs [

10]. The in-situ data had an average ALT of around 55 cm, making the RMSE significantly large with respect to the unit of measure. This large error served as motivation for this paper.

ReSALT is based on two main phenomenon. The first is ALT is proportional to

, where

stands for Accumulated Degree Days of Thaw. This is the well-known Stefan Equation and is shown in (

1).

where

N is a proportionality factor. This is derived in

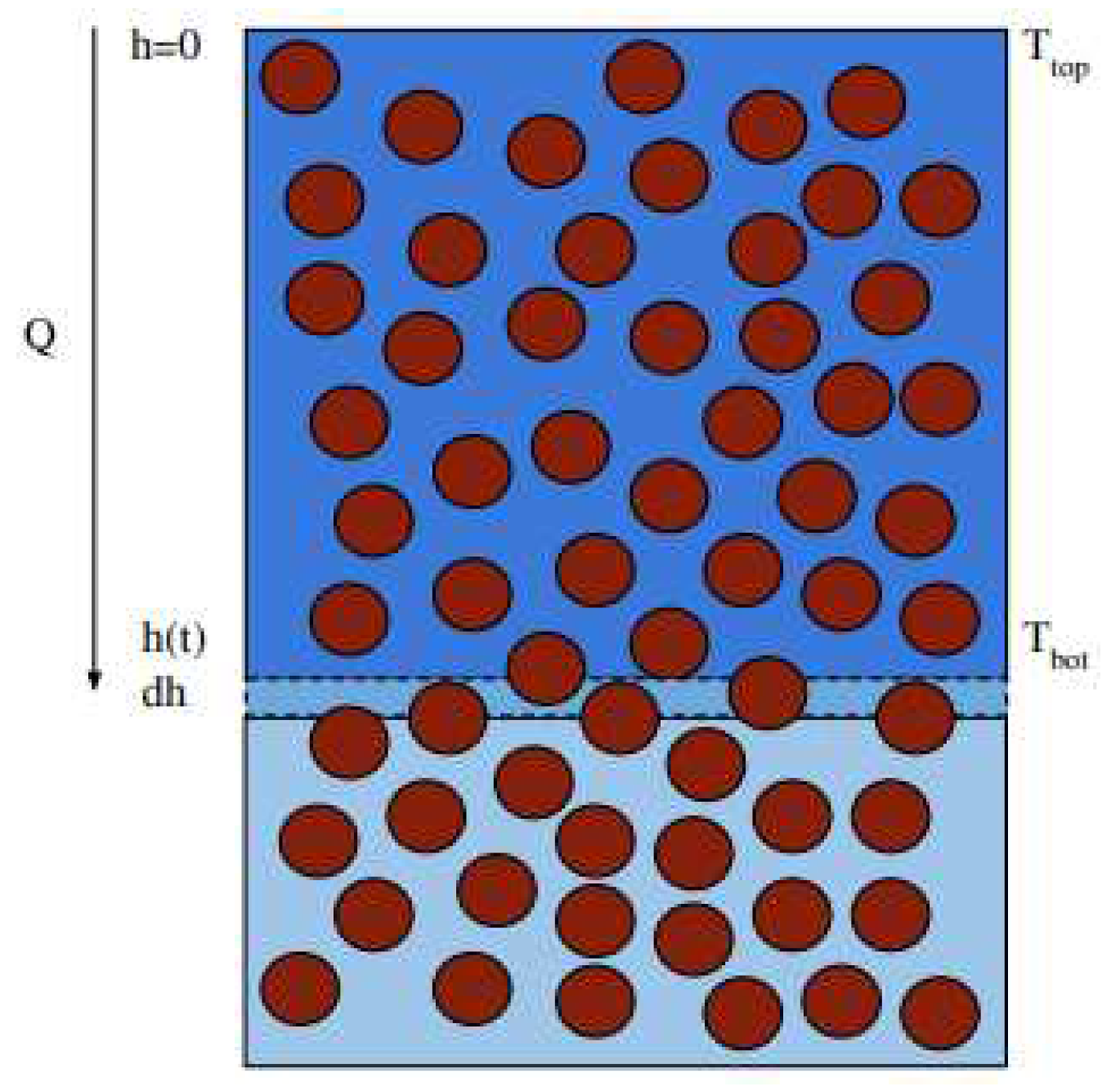

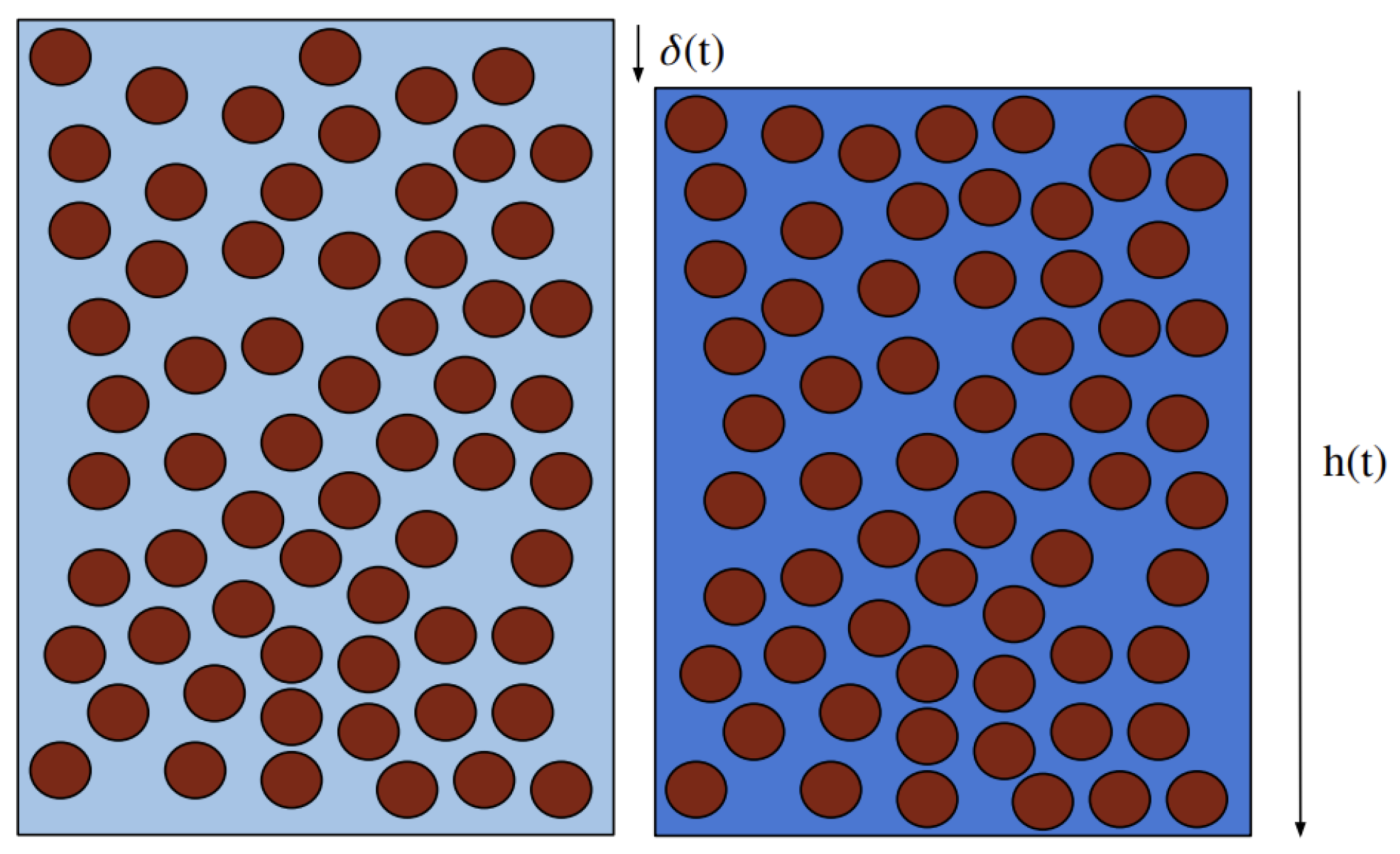

Appendix A. The second is that soil is fully saturated, meaning all pore space is filled with water. Consequently, when ice thaws into liquid water, the amount of volume reduces, which leads to a subsidence of the ground. This is shown visually in

Figure 1 and captured mathematically in (

2).

where

is the density of water,

is the density of ice,

P is the soil porosity, and

S is the soil saturation. The integral captures the volumetric water content. The ratio

describes the difference in volume height when the ice phase transitions to liquid water per unit volume of ice.

2 We can then compute the difference in ground height by multiplying the two quantities, therefore arriving at (

2).

f is introduced as a convenience to compute subsidence from ALT.

Any particular InSAR image contains subsidence difference

. Temperature is typically known at a coarse resolution. Hence, ReSALT strives to find a way to relate these two quantities, and ultimately retrieve

. It does so by posing the following least-squares inversion problem:

where

is the measured subsidence difference in the

ith interferogram,

and

describe the times of the two SAR acquisitions that were used to create the

ith interferogram, and

and

describe the

’s for

and

. Note that all

refer to the same geographic location, but may differ in pixel location from image to image.

R and

E are the unknown variables and are solved for.

R captures a long-term subsidence trend. More information can be found in [

6,

11].

E captures the relationship between

and subsidence difference, which can then be used to identify subsidence at any arbitrary time

t via:

Then, (

2) can be inverted to obtain

. More details on ReSALT’s derivation are shown in

Appendix B.

2.2. ReSALT Inconsistency Description

In (

4), we see that subsidence difference is modeled as proportional to

. Using (

1) and (

2), we can see that this only happens when

P is constant with depth. Hence, any application of ReSALT that uses a non-constant porosity model is self-inconsistent. Examples of self-inconsistent applications of ReSALT are [

8] and [

9], which use the “mixed soil model” shown later in this paper.

3. Method

The fundamental problem is that we only measure and subsidence difference , but we know no relationship between the two. We will first demonstrate a simple way to solve this problem for a practical soil moisture model. Then, we will more rigorously analyze the proposed method to understand its properties.

If we ignore

R, we can see that the correct inversion LHS (left-hand side) for (

3) is ALT difference:

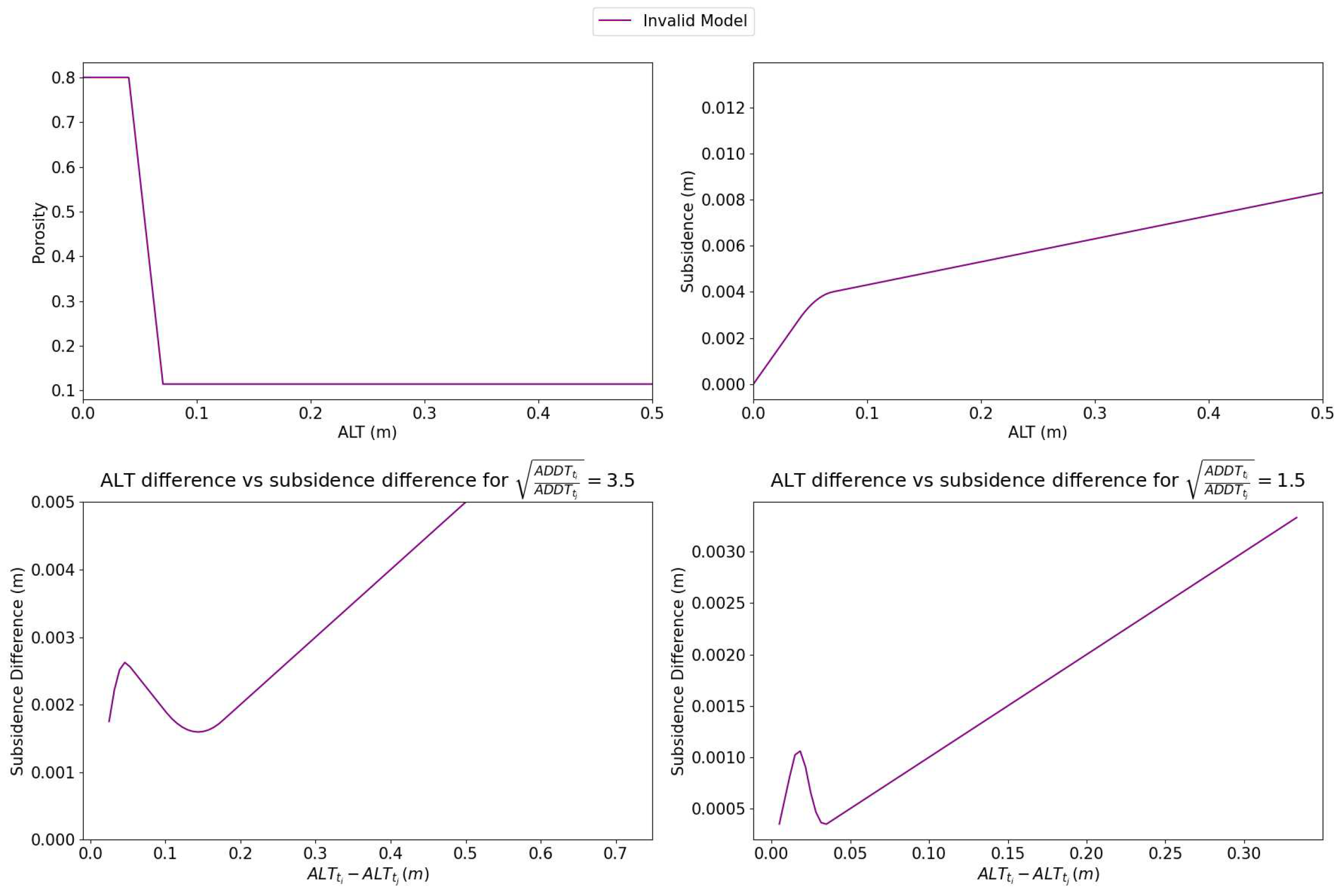

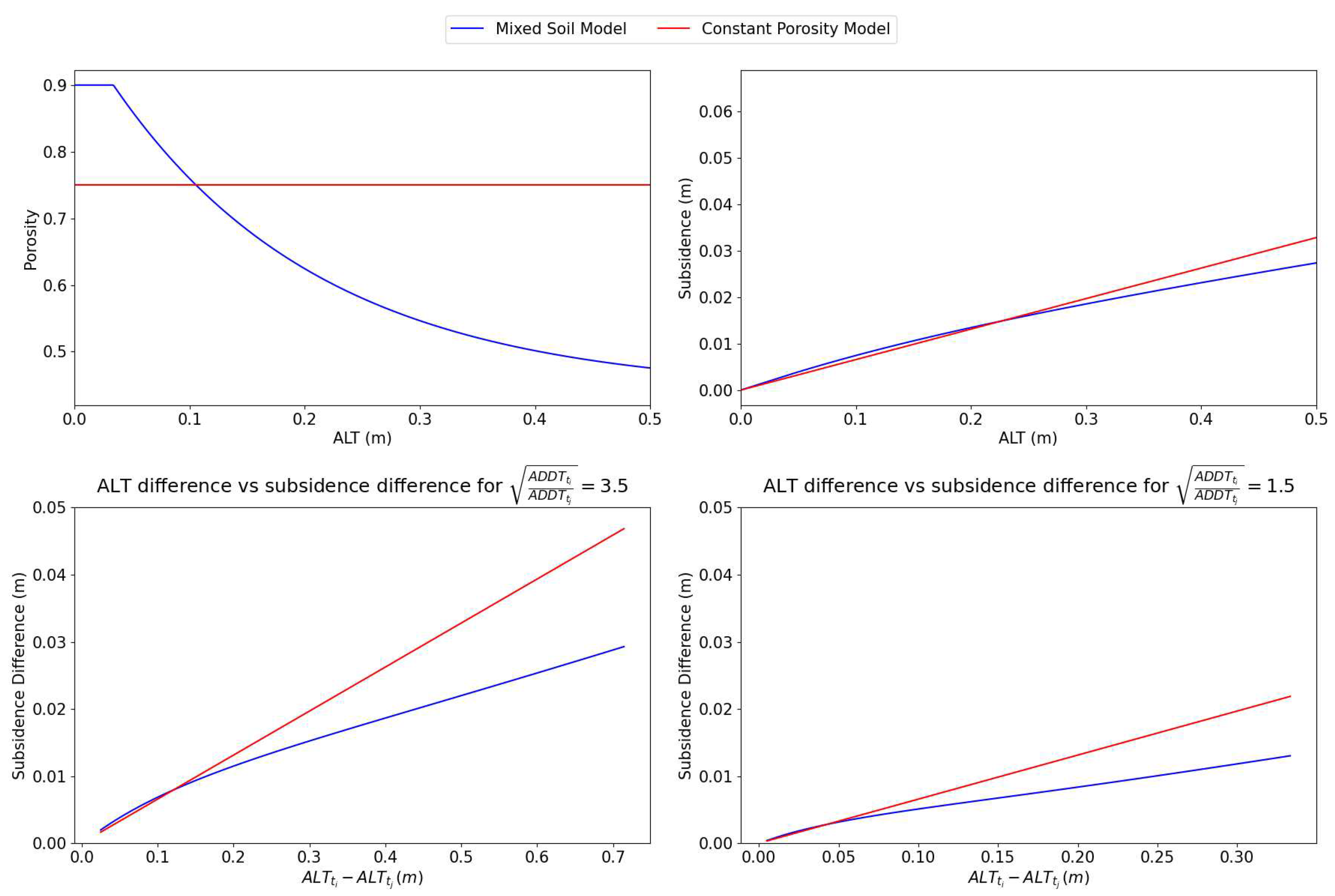

To see if subsidence difference can be related to ALT difference, we analyze (

1) as a ratio:

Next, we fix some ratio

, create a list of

on some large interval of candidate ALTs, generate corresponding

use (

7) to calculate the corresponding subsidences for each

and

, and then plot ALT differences and corresponding subsidence differences. See

Figure 2 for examples of this plot for two soil porosity models. Each of these models is explained explicitly in [

8]. As shown via a “horizontal line test,” a particular subsidence difference can always be directly mapped to an ALT difference with zero ambiguity. Intuitively, this is because (

7) enables multiplicative growth of

with respect to

. Consequently, we would hope that (

2) enables subsidence difference to grow strictly monotonically. Of course, there is no guarantee that this always will be the case. A counterexample is discussed in

Section 3.1.

This method is summarized Algorithm 1. We can now rewrite (

3) as:

where

is the best-matching ALT difference reported for each

via Algorithm 1. This now forms a self-consistent modelling of thaw, temperature, and ground subsidence. Hence, we call this new method SCReSALT (Self-Consistent ReSALT). Least-squares inversion gives the best

A, which can then be used to find ALT at any point in the thaw season:

|

Algorithm 1 Self-Consistent ReSALT LHS Retrieval |

Require:

Require:

- 1:

- 2:

- 3:

- 4:

▹ Calculate step size for linear spacing - 5:

fordo

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

- 9:

▹ See ( 2) - 10:

end for - 11:

small neighborhood in which a subsidence difference should be unique - 12:

if not check_unique then

- 13:

raise Error(“x and y have non-unique matching.”) - 14:

end if - 15:

Find k such that is closest to D

- 16:

return

|

To extend the formulation to multiple years, we simply need to discount the long-term trend R from the measured subsidence difference before following the above approach. ReSALT jointly inverts for R and E, but a self-consistent model cannot do that. So, we must find a way to estimate R independently of and prior to A. Thankfully, there are many ways around this. Two are discussed here.

Form interferograms across multiple years at the start of thaw season, ideally when (and perhaps there is some tolerance on how large can get before it affects the result due to seasonal subsidence). Any observed subsidence can be attributed to R. Compute the best-fit R that solves all .

Compute an initial estimate of

A by solving (

8).

A could be solved either per thaw season (which makes

) or overall. Then, like the previous bullet point, form interferograms across multiple years at the start of thaw season and remove the subsidence contribution due to ALT. This is known because the subsidence contribution due to ALT can be written as:

. Note

denotes

A for the thaw season in the 2nd SAR image in the

ith interferogram.

means the same for the 1st SAR image. Compute the best-fit

R that solves all

.

Once

R is known, the multi-year problem can be solved using (

8) but instead of giving Algorithm 1 the observed subsidence difference

, give it

.

For completeness, it is worth noting that both ReSALT and SCReSALT do not need both SAR acquisitions to be precisely during the thaw season. One acquisition could be before the thaw season, in which case we can assume

for that acquisition. Hence, any measured subsidence difference can be modeled as the true subsidence at that point. ReSALT can directly use (

3). SCReSALT would need a slight modification because it operates using ratios. Algorithm 1 could be modified such that if

, simply report

. Similarly, if

, report

. The sign change is because

is the subsidence underwent when going from

to

. That is expected to be positive if

and negative vice-versa.

3.1. SCReSALT Counterexample Discussion

A more rigorous analysis of SCReSALT is shown in

Appendix C. It shows a counterexample with a realistic soil porosity model that does not meet the SCReSALT requirement. Some possible workarounds are described below, but we leave exploring them to future work.

From multiple interferograms per year and obtain time-series measurements of subsidence difference. Attempt to interpolate the measurements onto an ALT difference vs subsidence difference graph and determine which ALT differences best explain the data.

Make sure to get a SAR acquisition before the thaw season starts. This allows one to treat the subsidence difference as the true subsidence. Handling this is easy and was described earlier in this paper.

Incorporating a prior on ALT difference might isolate a particular ALT difference as the most likely candidate.

4. Experiments

To assess the practical improvement of our method, we reproduce and benchmark against the results reported in [

9]. [

9] applies ReSALT to Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow), Alaska to predict ALT from 2006 to 2010. The paper uses data from the U1 CALM

3 plot. It uses ALOS-PALSAR L-band data and generates interferograms using the ISCE2 framework

4. The paper defines the

metric:

where

e is the uncertainty in the measurement. In [

9],

cm. If

, it is called a “great match.” If the

is within the uncertainty of

, it is called a “good match." Otherwise, it is called a “bad match.” We have not described uncertainty analysis in this paper, but in brief one could compute uncertainty by assigning an uncertainty to each ReSALT/SCReSALT parameter and either analytically propagating that into an uncertainty in the prediction or more practically using numerical simulation to understand the distribution of predictions as a function of the modeling parameter distributions. Since this paper is primarily concerned with RMSE improvement, and uses

as a way to assess reproduction accuracy, we do not discuss uncertainty explicitly in this analysis. Instead, we take advantage of the fact that [

9] states that the ReSALT uncertainty is roughly twice that of the measurement uncertainty. Hence, we use

cm. This makes the “great match,” “good match,” and “bad match” categorizations directly comparable. Additionally, [

9] uses the same “mixed soil model” from [

8]. Further specifics (namely image calibration) on the reproduction are described in

Appendix D. With those details explained, results are shown in

Table 1.

5. Discussion

As we can see in

Table 1, the reproduced ReSALT had much worse results than in the original paper. Private correspondence and a review of the software with the authors of [

9] suggested that the reproduction was most likely very similar. Also, it is worth noting that [

10] reported similar RSMEs to the reproduced ReSALT (albeit for a broader set of CALM sites). For completeness, we show comparisons between the reproduced ReSALT, the original paper, and SCReSALT. Given that SCReSALT outperforms the original paper on the

metric, we take these results to mean SCReSALT outperforms ReSALT. Of course, this is to be expected. SCReSALT makes no approximations and can perfectly model the “mixed soil model” in a self-consistent way.

6. Conclusion

We present SCReSALT, a modification to ReSALT that enables self-consistency. SCReSALT makes no approximations and reduces to ReSALT under the right soil models. We also rigorously analyze SCReSALT’s requirements and identify a counterexample where the requirements are not met. We then describe possible workarounds but leave exploring that to future work. Experimentally, SCReSALT demonstrates significant improvement in predicting ALTs in Utqiagvik, Alaska. We recommend SCReSALT become a standard tool in permafrost thaw modelling.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Stefan’s Equation Derivation

We first derive Stefan’s Equation to understand the relationship between temperature history and ground ice thaw.

Figure A1 is provided to help visualize the relevant processes . We start with Fourier’s Law:

Figure A1.

A diagram of a thawing soil column. h denotes the position of the thaw front. Q is the (uniform) heat flux induced by and . is the same as the temperature of the air. Brown circles denote soil particles. Anything that is not a soil particle is pore space. Note that any real soil would have a far more dense concentration of soil particles. Dark blue denotes liquid (thawed) water. Light blue denotes frozen (unthawed) water. In this diagram, we assume all pore space is filled with water. This does not have to be the case for Stefan’s equation to apply. A different bulk density and latent heat of thaw L can capture the thaw dynamics of a variety of soil hydrology models.

Figure A1.

A diagram of a thawing soil column. h denotes the position of the thaw front. Q is the (uniform) heat flux induced by and . is the same as the temperature of the air. Brown circles denote soil particles. Anything that is not a soil particle is pore space. Note that any real soil would have a far more dense concentration of soil particles. Dark blue denotes liquid (thawed) water. Light blue denotes frozen (unthawed) water. In this diagram, we assume all pore space is filled with water. This does not have to be the case for Stefan’s equation to apply. A different bulk density and latent heat of thaw L can capture the thaw dynamics of a variety of soil hydrology models.

where

Q is the heat per unit area per unit time,

is the thermal conductivity,

T is temperature, and

h defines the position of the thaw front. Note that both

T and

h are functions of time

t. Assuming the temperature gradient is uniform throughout the column, we can write:

Next, we assume that all heat is absorbed as latent heat to facilitate phase change from ice to liquid water. Consequently, an infinitesimal change in thaw depth

can be related to the amount of heat required to do so by:

where

H is the amount of heat per unit area required to advance the thaw front by

,

is the bulk density of soil, and

L is the latent heat of thawing. Differentiating with respect to time:

Since

refers to the boundary of thawed/frozen soil, it is reasonable to assume

, in which case we can remove it from (

17).

Practically, once the thaw season begins

. Since

is typically measured at daily basis (rather than continually), we can replace the right-hand side (RHS) with:

where

stands for the Accumulated Degree Days of Thaw. It is a standard number used in permafrost literature and is calculated at any day

t by summing the temperatures of all days preceding and including

t. Now, looking at the left-hand side (LHS), if we assume

and

L are constant with depth:

At this point, we have derived Stefan’s equation. It is the same as equation (A4) in [

12]. Note that in this derivation, we used the opposite sign convention. We set

at the ground and make

h increase with depth. [

12] does the opposite, hence flipping some signs in the above equations.

Appendix B. ReSALT Derivation

We now present the derivation for ReSALT. First, we assume that thaw begins when

first exceeds 0 °C-days.

5 So, if

is the start of the thaw season, we know that

,

. Recall that (

22) only applies for times within the thaw season, so that is why we need this assumption. We can then write the thaw depth at any time

:

We have now derived (

1). InSAR gives measurements of ground subsidence

as determined by two SAR acquisitions at

and

. Most ReSALT methods model subsidence as (

2). In general,

P is not constant with depth. This means

is not linearly proportional to

. However, because we only measure

and

D, ReSALT strives to find a way to relate the two. To do so, it makes the assumption of constant porosity and therefore proportionality:

For any InSAR measurement, we know

. We also know the times of the two SAR acquisitions, meaning we can determine

and

. So, we could determine the coefficient

. If we have multiple InSAR images, we can pose (

27) as a least-squares inversion problem, leading to (

3). Therefore, any use of (

3) with a non-constant porosity model will be inconsistent.

Appendix C. SCReSALT Counterexample Analysis

We now conduct a more rigorous analysis of SCReSALT through which we derive a counterexample. The mathematical premise of SCReSALT can be stated as follows: Given an integrable

6 function

P for which

, then for any ratio

,

can be uniquely identified by

(following (

2)). This can be restated as: if

, then SCReSALT requires

. We know

f is strictly increasing with

z. We can write

. There are constraints on

P, and hence constraints on

f, but for simplicity we will at first ignore

P and just consider

f. To create a convincing failure case, we consider whether a range of

Q can contradict the SCReSALT requirement. Mathematically, we consider two ratios

and two points

with the following property:

Taking the difference leads to:

If we assume

, that

is small, and that

f is locally linear around both

and

, we get:

where

is the local linearity coefficient around

and

is the local linearity coefficient around

. (

32) might appear simple, but it contains our answer! This tells us that if

and

, and they follow (

32), then for some

Q we will observe the same subsidence difference. If we extend the local linearity, we can extend the range of

Q that lead to the same subsidence difference. Using this insight, we can devise a piecewise linear

f that does not meet the SCReSALT requirement. We can use a quadratic function to fit the ends of the piecewise linear functions. As long as i) the values and derivatives match at the intersection points, ii)

f is strictly increasing, and iii) a valid

P can be constructed from

f, we have met the requirements. An example is shown below:

This example is scaled such that there is a valid corresponding

P model.

P can be generated by taking the derivative of each case and multiplying by

, as shown below.

Both

f and

P are visualized in

Figure A2, which demonstrates a potentially realistic soil porosity model that does not meet the SCReSALT requirement.

Figure A2.

A diagram showing a physically realizable soil porosity model that fails the SCReSALT requirement. As shown in the bottom images, subsidence difference cannot necessarily be equated to an ALT difference.

Figure A2.

A diagram showing a physically realizable soil porosity model that fails the SCReSALT requirement. As shown in the bottom images, subsidence difference cannot necessarily be equated to an ALT difference.

Appendix D. Experiments Calibration Step

The paper uses node 61 of the U1 CALM

7 plot as a reference or calibration node. In general, InSAR requires a calibration pixel where subsidence is known to calibrate the subsidence image. InSAR practitioners typically use a point in which subsidence is known, such as on gravel where it is assumed to be 0. In [

9], no pixel had known subsidence, so they instead formulated (

3) as “delta subsidence differences” with respect to node 61. After inversion, they calculated the subsidence of the calibration node by inputting its measured in-situ ALT into (

2). They then corrected the best-fit

E with a global offset that made the calibration node have the expected measured subsidence. This is actually problematic because the

E that they compute is on a seasonal basis yet the calibrated subsidence measurement is at measurement time, which slightly predates the end-of-season. We do not correct this error, but simply take note of it here. An easy way to fix the error is to scale

E by the

at measurement time, which would be a valid operation under ReSALT formulation (but not SCReSALT). SCReSALT handles the calibration node as follows:

To be clear, the steps listed above only need to be followed when the calibration node is itself subsiding. SCReSALT/ReSALT ultimately need an image in which subsidence difference is known.

References

- Kevin Schaefer et al., “Amount and timing of permafrost carbon release in response to climate warming.,” Tellus B, vol. 63, pp. 165–180, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Schneider von Deimling et al., “Observation-based modelling of permafrost carbon fluxes with accounting for deep carbon deposits and thermokarst activity.,” Biogeosciences, vol. 12, pp. 3469–3488, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Ruiz, “$41m audacious grant will tackle permafrost thaw,” Woodwell Climate, 2022, Available at: https://www.woodwellclimate.org/41-million-grant-for-permafrost-thaw-monitoring/. (Accessed: 1st November 2023).

- “Carbon emissions from permafrost,” 50x30, 2023, Available at: https://www.50x30.net/carbon-emissions-from-permafrost. (Accessed: 1st November 2023).

- K.R Miner et al., “Permafrost carbon emissions in a changing arctic.,” Nat Rev Earth Environ, vol. 3, pp. 55–67, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lin Liu et al., “Insar measurements of surface deformation over permafrost on the north slope of alaska.,” Journal of Geophysical Research, vol. 115, 2010. [CrossRef]

- European Space Agency, “Insar principles: Guidelines for sar interferometry processing and interpretation,” Tech. Rep., ESA Publications ESTEC, February 2007.

- Liu Liu et al., “Estimating 1992–2000 average active layer thickness on the alaskan north slope from remotely sensed surface subsidence.,” Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, vol. 117, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Kevin Schaefer et al., “Remotely sensed active layer thickness (resalt) at barrow, alaska using interferometric synthetic aperture radar,” Remote Sensing, vol. 7, pp. 3735–3759, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Richard Chen et al., “Permafrost dynamics observatory (pdo): 2. joint retrieval of permafrost active layer thickness and soil moisture from l-band insar and p-band polsar.,” Earth and Space Science, vol. 10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Nixon and A. Taylor, “Regional active layer monitoring across the sporadic, discontinuous and continuous permafrost zones, mackenzie valley, northwestern canada,” in Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Permafrost, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada, 1998, International Permafrost Association, pp. 815–820.

- Roger Michaelides et al., “Permafrost dynamics observatory—part i: Postprocessing and calibration methods of uavsar l-band insar data for seasonal subsidence estimation,” Earth and Space Science, vol. 8, 2021. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

For the remainder of this paper, ground subsidence refers to the downwards motion of the ground and is a measure of distance. If the ground shifts down, subsidence is a positive number. If the ground shifts up, subsidence is negative. |

| 2 |

[ 10] argues convincingly that the ReSALT formulation only works when . If , some open pore space will be filled by freeze/thaw before the ground subsides. At a critical threshold (characterized by the densities of liquid water and ice), freeze/thaw might lead to no ground subsidence. So, we assume . |

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

[ 12] proposes that this is perhaps an erroneous assumption and suggests a different approach. However, we will not address that here. |

| 6 |

One might argue that a physically realizable P should be differentiable. We ignore that in the analysis presented in this paper, but it not hard to see that the example P given later could be made differentiable without changing the conclusion. |

| 7 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).