Introduction

Cotton, one of the world's most important cash crops, is critical to the global textile industry, and its production is a pillar of agricultural economies in many places. However, a wide range of pests and diseases are constantly attacking the cotton crop, devastating yields and lowering the quality of the cotton fibers. The detection of pests and diseases in cotton crops is a complex task that involves recognizing, tracking, and controlling a range of harmful insects, fungi, bacteria, and viruses. Inadequate detection can have dire implications, affecting the world's supply of this vital raw material and causing cotton growers to suffer significant financial losses.

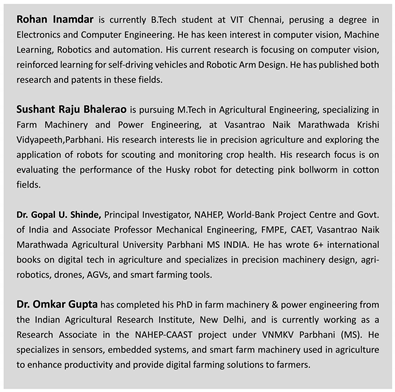

A tiny, typically around 1/2 inch long and pinkish moth larva (refer

Figure 1) called the Pink Bollworm (Pectinophora gossypiella) has the potential to seriously harm cotton crops. The whole metamorphic life cycle of the pink bollworm includes the egg, larval, pupal, and adult stages. The larvae of the pink bollworm enter within the cotton bolls, feeding on the surrounding cotton fibers and seeds which reduces the cotton quality, yield loss, and cotton lint contamination can result from this feeding practice. Cotton producers must keep a close eye out for Pink Bollworm infestations since damage to cotton crops can be reduced with early diagnosis and effective control techniques.

In addition to lowering output and degrading cotton fiber quality, diseases can have a major effect on cotton crops. The kind of sickness, the surroundings, and the methods used for managing it are some of the variables that affect how much of an impact there is. While certain types may be more susceptible to disease, others may have been developed to be resistant to it. The type of cotton being farmed determines how a disease affects the crop. For the purpose of early identification and intervention, routine monitoring and looking for illness indicators are crucial. Early illness detection enables prompt treatment, which may lessen the possible impact on yield.

Pesticides have been used widely and repeatedly, which has put selection pressure on the population of pests and encouraged the survival and procreation of those with innate resistance features. This has caused a population's tolerance to widely used insecticides to rise over time [

1]. In order to encourage healthy cotton bolls to develop healthier and avoid wasting resources on infected cotton bolls, we would like to suggest a solution that includes removing cotton bolls affected with pink bollworm in their early stages.

This research presents a unique system for monitoring diseases and pests in cotton crops. By harnessing existing technology, we elevate crop health surveillance to new heights, enabling more effective detection and management strategies. Importantly, the methodologies described in this research have the potential to be applied to different crop types, providing a flexible framework for agricultural monitoring and management. While initially applied to cotton crops, our methodology holds promises for broader adoption. Farmers can leverage similar techniques for diverse crops, enhancing sustainability across the agricultural landscape.

Literature Work

The researchers emphasized how transgenic crops that produce Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) toxins might lessen the need for pesticides by killing several important insect pests [

2]. As more of these Bt crops were planted, worries grew that pests would quickly develop tolerance to the toxins in the crops, limiting their utility. For eight years, the resistance of pink bollworms to Bt toxin was recorded. Although there was a delay, it has undergone strong selection to develop a resistance to Bt cotton.

Data-driven techniques in precision agriculture have received a lot of interest in recent years because of their potential to handle issues like insect detection. The study [

3], encouraged by the criteria of the H2020 European project PANTHEON, provides a unique pest detection system designed specifically for hazelnut orchards. Using a bespoke dataset gathered in real-world outdoor circumstances, the study applies a You Only Look Once (YOLO) based Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to achieve roughly 94.5% average precision in recognizing actual bugs, a major danger to hazelnut production. The study investigates a variety of factors, including data augmentation techniques and depth information, to improve the detector's resilience. Furthermore, by running the system on an NVIDIA Jetson Xavier, the study promises effective real-time processing at about 50 frames per second, facilitating onboard implementation on robotic platforms for seamless integration into precision agriculture practices.

A region-based end-to-end method called PestNet which is divided into three main sections was proposed for large-scale multi-class pest identification and classification using deep learning [

4]. First, for feature extraction and augmentation, a novel module called channel-spatial attention (CSA) was suggested to be fused into the convolutional neural network (CNN) backbone. Based on feature maps that are generated from photos, the second is known as the region proposal network (RPN), and it is used to provide region proposals as possible pest places. The third component, the position-sensitive score map (PSSM), was utilized for bounding box regression and pest classification in place of fully connected layers. According to the experimental results, the suggested PestNet surpasses state-of-the-art techniques in multi-class pest identification, with a mean average accuracy (mAP) of 75.46%.

Automated weed management systems based on computer vision were developed as a sustainable alternative. However, the variety of field settings and plant species offers hurdles for accurate detection. The study [

5] tackles this issue by offering the CottoWeedDet12 dataset, which includes 5648 photos of 12 weed types in cotton fields in the southern United States, together with 9370 annotated bounding boxes. This dataset serves as a complete benchmark for 25 YOLO detectors, including YOLOv3, YOLOv4, and YOLOv5. The results show great accuracy, with mAP@0.5 ranging from 88.14% to 95.22% and mAP 0.5:0.95 from 68.18% to 89.72%. YOLOv5 models show potential real-time performance, particularly when paired with data augmentation.

In recent years, there has been an increased emphasis on accurately detecting and counting unopened cotton bolls to improve crop management and harvesting techniques. In response to this requirement, a novel deep learning algorithm known as MRF-YOLO [

6] was presented in recent research. This technique uses the YOLOX framework to extract multi-receptive fields. MRF-YOLO uses unique elements such as a multi-scale residual block, attention module, and tiny target detection layer to improve feature extraction and accuracy in recognizing small targets such as cotton bolls. A Comparative study showed a significant 14.86% increase in average accuracy, resulting in an astounding 92.75% accuracy rate while maintaining a high processing speed. In addition, a detection-based counting approach is provided, producing encouraging results with a mean squared error of 1.06 and a coefficient of determination of 0.92.

An agricultural field may have several processes monitored and automated using of Internet of Things (IoT) systems, which utilize a variety of sensors [

7] or the use of computer vision in agriculture for detection, harvesting, sorting and grading, machine navigation, and field robotics [

8]. A brief discussion of the possible integration of deep learning with computer vision technologies through agricultural automation, computer vision may enhance small-scale farming through high performance and precision.

Precision is crucial for useful production measurements in agriculture [

9]. Agricultural robots often have to be reconfigured for different applications or used for multiple applications at once, which can reduce reading accuracy. It is crucial to select trajectories that maximize manoeuvrability while optimizing measurement accuracy by accounting for the vehicle's changing dynamics. The ideal path connecting two locations for a husky robot that can be adjusted to take readings from any angle while adhering to the vehicle's dynamic limitations.

The multi-robot system WAMbot was developed to recognize visual objects and move, explore, and map expansive urban settings [

10]. The open-source Robot Operating System (ROS) software architecture is being used to standardize and enhance the WAMbot system. The main elements, or stacks, of the new WAMbot system [

11] included an effective, frontier-based multi-robot exploration stack, a large-scale mapping stack that can create 500×500m global maps from over 20 robots in real-time, a navigation stack that combines centralized global planning with decentralized local navigation and an easy-to-use graph-based visual object recognition pipeline.

The literature study [

12] demonstrates a multifaceted approach to autonomous navigation in agricultural areas, with a particular emphasis on cotton farms. Existing approaches, such as GPS navigation and vision-based techniques, have limitations such as availability and sensitivity to environmental changes. The suggested integrated method, which integrates GPS and optical navigation, is a promising approach. Three alternatives were designed and assessed, each with its own set of advantages. The route tracking system performed well while following pre-recorded paths. However, the deep learning model combined with path planning techniques considerably decreased lateral deviation. The combination of GPS mapping and local planning approaches provides a realistic solution, allowing the robot to effectively travel between cotton rows. This integrated strategy provides a possible answer to the issues of autonomous navigation in agricultural fields.

Cotton-picking robots [

13] that use SMACH-based control systems demonstrate their effectiveness in coordinating complicated movements necessary for successful boll harvesting. These robots use stereo cameras for accurate boll recognition and 2D manipulators directed by finite state machines to perform picking operations. PID control ensures precise rover motions toward the desired bolls. The benefits include task-level deployment of numerous functions, flexibility, and optimum control. A picking performance of 17.3 seconds per boll with high detection rates demonstrates the system's efficacy in agricultural contexts, promising increased production and resource efficiency.

This research addresses the gap in monitoring pests and diseases in cotton fields by proposing a novel system. By leveraging existing technology, it elevates crop health surveillance, offering adaptable strategies for detection and management applicable to various crops. The methodology, initially designed for cotton, holds promise for wider agricultural adoption, fostering sustainability.

Methodology

We have collected our own dataset from two fields which are the organic field and BT cotton field. The organic field consisted of a lot of pink bollworm-infected cotton bolls as it was an experimental field where cotton was naturally grown by providing the crops with only water and no pesticides.

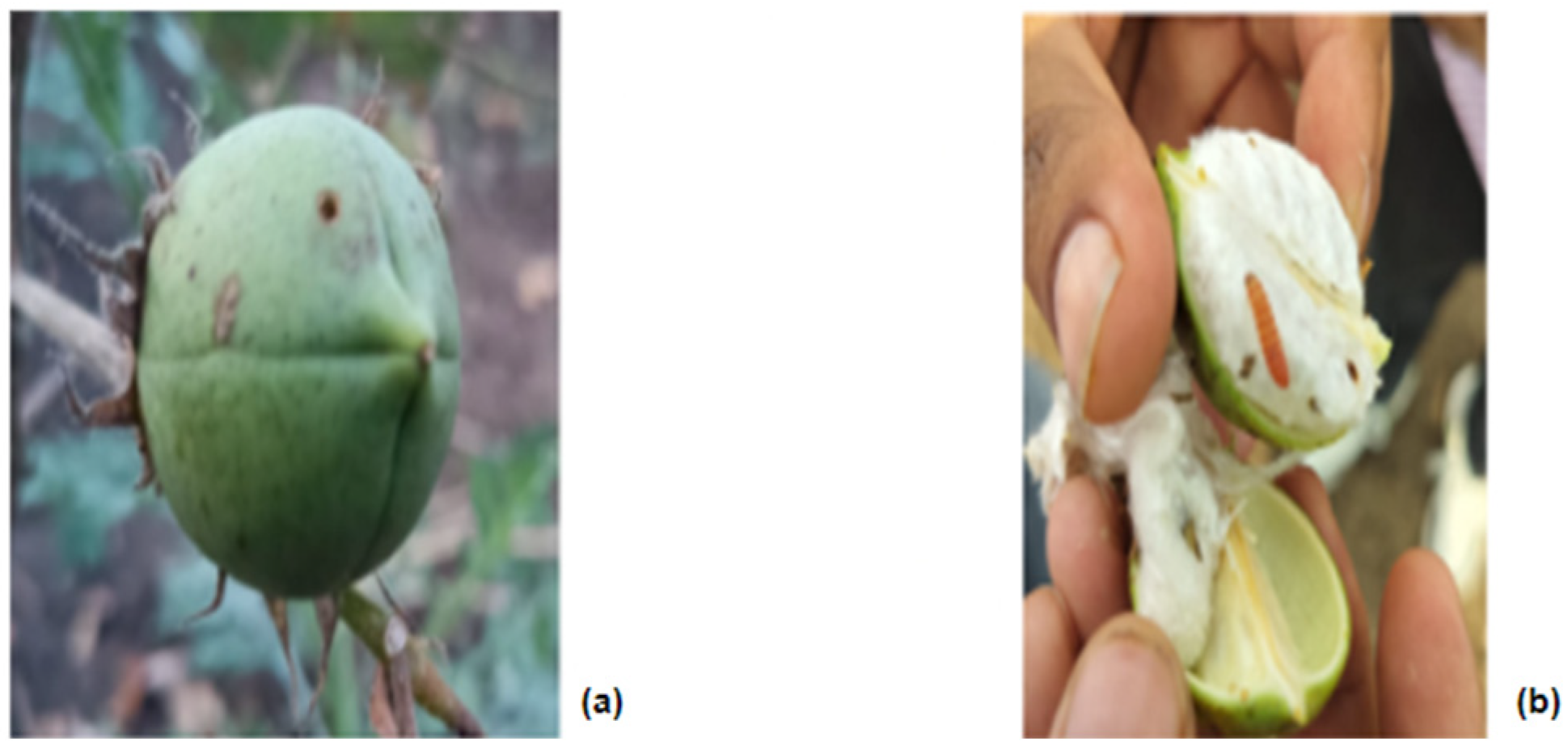

The proposed methodology (

Figure 2) includes the initial development of a deep learning model for detection and counting. This requires the dataset to be carefully labelled, a process efficiently done using Roboflow. The labelled dataset is trained with YOLOv8, which currently is the state-of-the-art object detection model. The next step is to construct the model and then seamlessly integrate it into an autonomous Clearpath Husky robot. This robot can accurately count and identify cases of Red Disease, Pink Bollworms, and other components in cotton fields. Real-time detection capabilities are smoothly integrated with the ROS Navigation framework to improve the robot's overall functioning. Through this complex integration, a customized pipeline that not only greatly improves the robot's perceptual abilities but also its navigational capabilities, guaranteeing a comprehensive and effective approach to agricultural monitoring and management.

The annotation process encompasses six distinct classes, including "cotton flower," "cotton boll," "cotton," "pink bollworm," "healthy leaf," and "red disease". We labelled the cotton bolls with holes in them as pink bollworms because, according to their characteristics, they live and grow inside cotton bolls and only emerge from them in cool environments. The tiny hole they leave on the boll during their first phase grows larger as the pest matures. The labels for the remaining classes are standard

Dataset

Our own data was gathered using RGB cameras from two different types of fields: BT cotton fields, which were sprayed with pesticides, and organic cotton fields, which were not sprayed with pesticides. The dataset is made up of over a thousand RGB photos showing three different phases of cotton (flower, cotton boll, and matured cotton), as well as healthy and red disease-infested leaves and cotton bolls infected with pink bollworm.

To supplement the dataset shown in

Table 1, we used a variety of strategies to introduce diversity to the photos. These included performing horizontal flips, adding noise, and blurring the photos. By supplementing the dataset in this way, we enhanced its size and variability, improving our model's resilience.

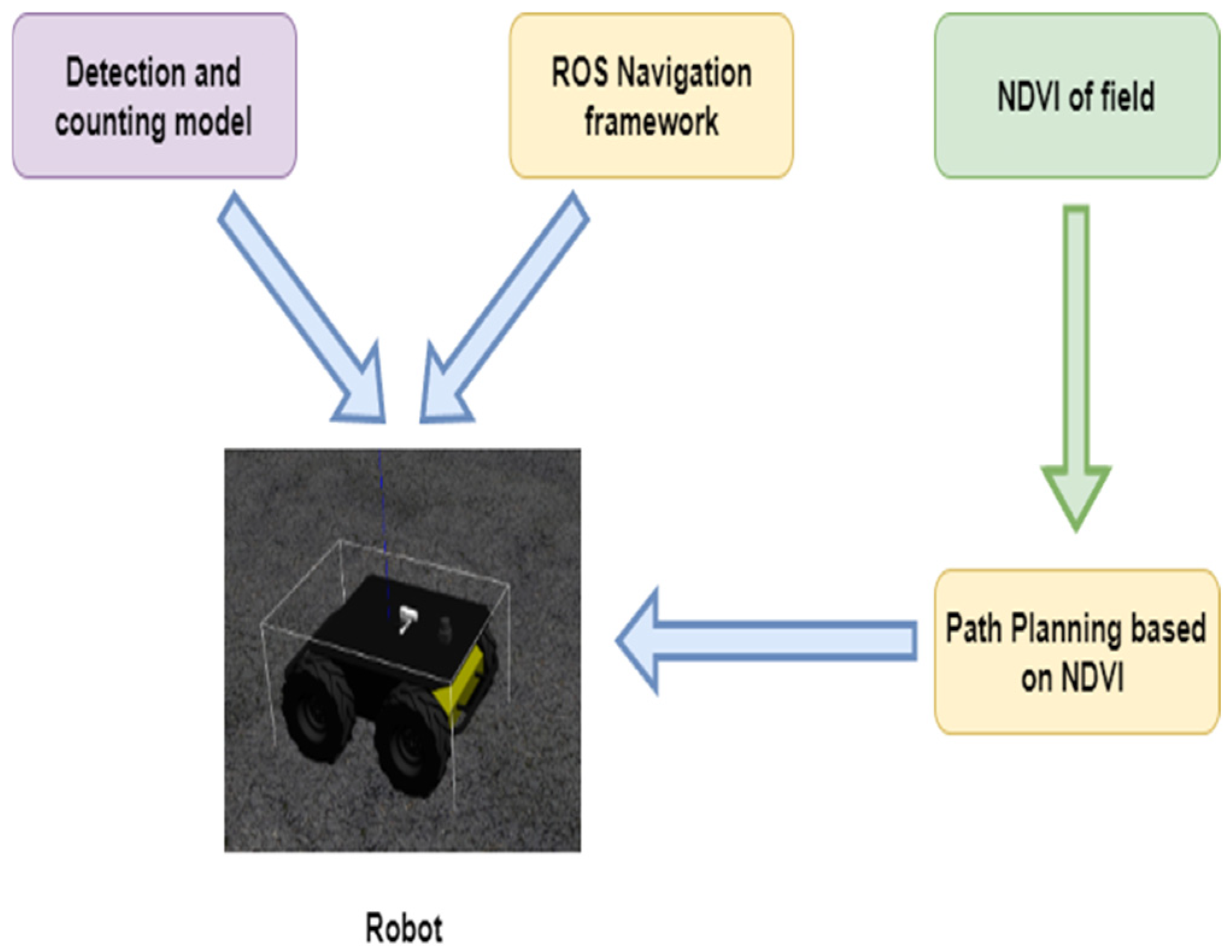

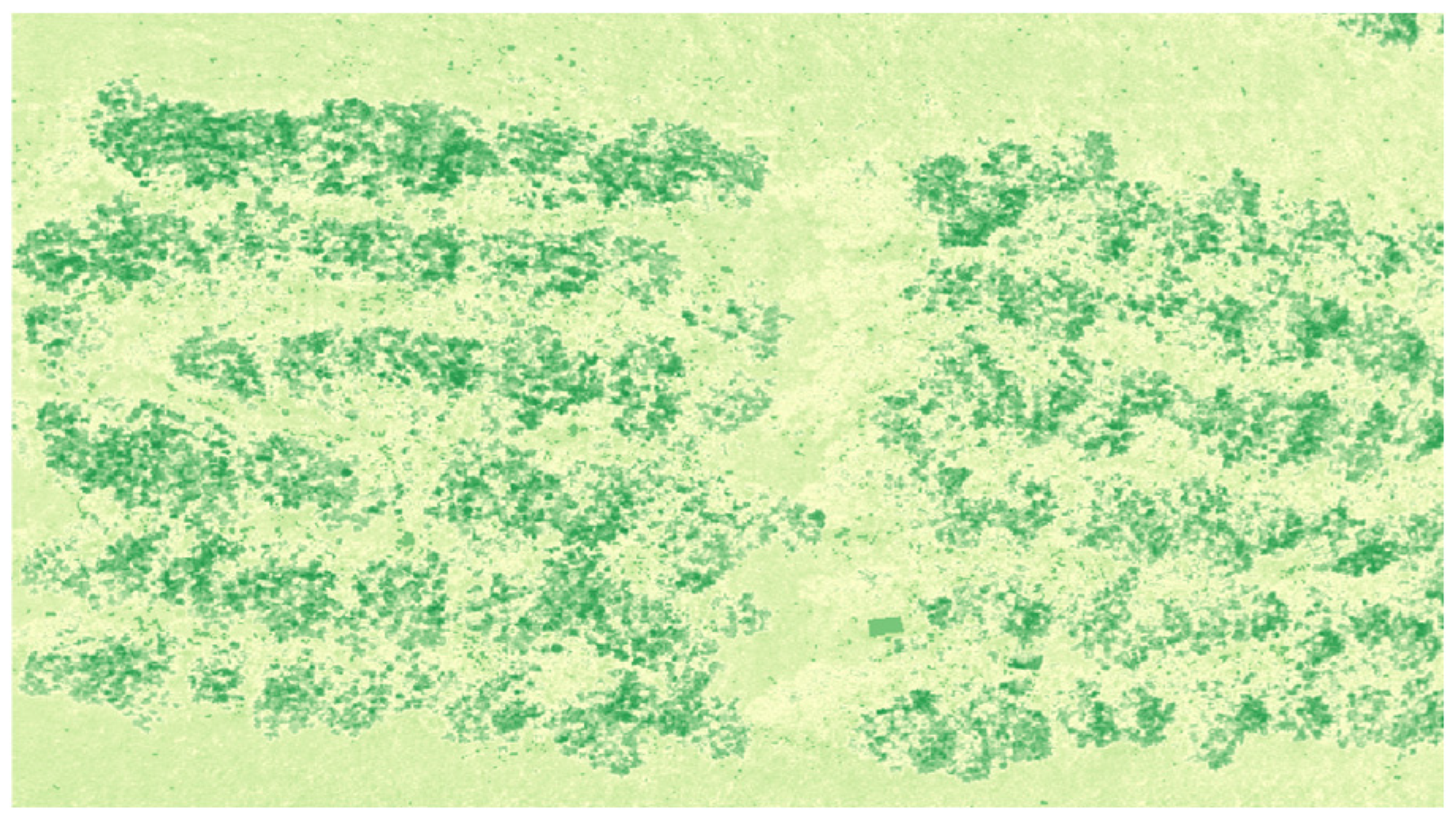

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) is calculated by taking pictures of a target area at various wavelengths as shown in

Figure 3. So, we have collected the data using the Parrot Sequoia multi-spectral camera, the dataset consists of target fields in the red, green, red edge, and near-infrared (NIR) bands are recorded by the Parrot Sequoia camera from the drones.

Model Architecture

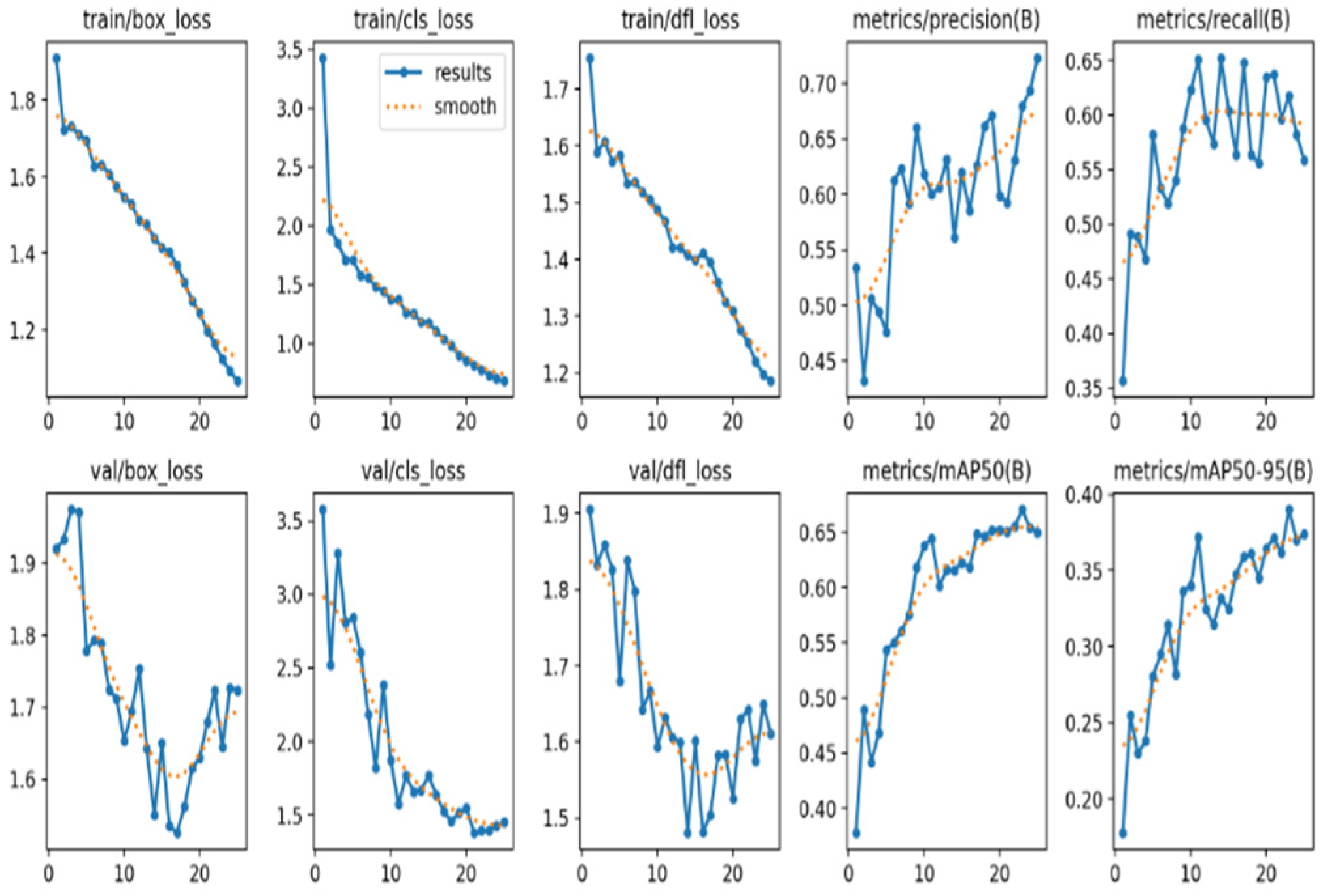

Our model was rigorously tested and labelled on the efficient Roboflow platform. The YOLOv8-S architecture was used for training at 25 epochs for reliable and accurate performance. In order to improve accuracy and dependability, supervision was also used for counting and tracking the objects that emerged. The learning rate of 0.001, which is often utilized as a starting point, worked well for this investigation. A batch size of 8 balanced memory utilization and training efficiency, resulting in consistent convergence with minimal computational cost. The Adam optimizer was chosen for its ability to handle big datasets and adaptively alter learning rates. These parameters were continuously refined based on validation dataset performance in order to maximize training and produce satisfying results.

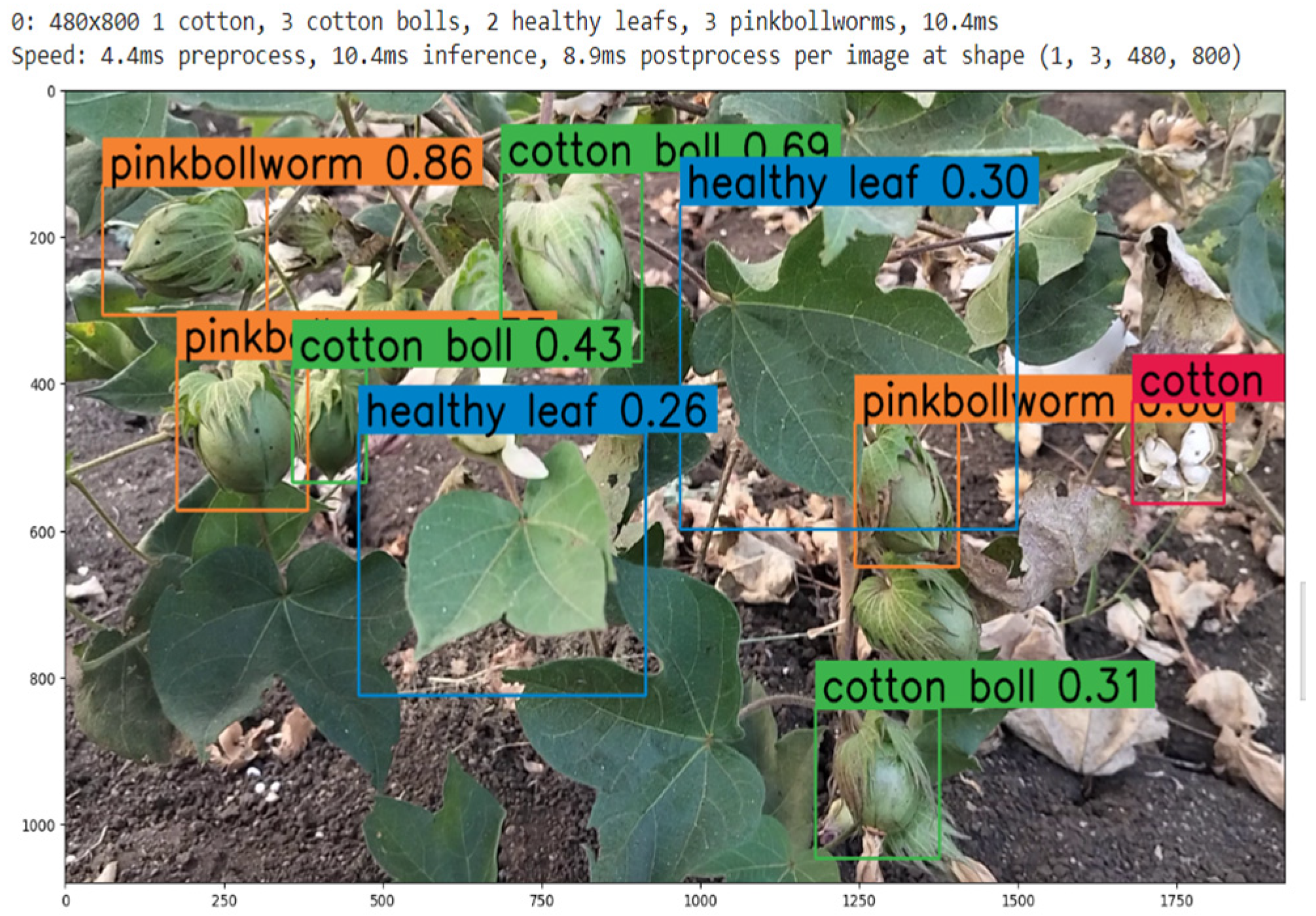

In

Figure 4, the counting of identified classes in the frame is depicted. This visual representation showcases the accurate enumeration of various classes detected within the frame, providing valuable insight into the model's performance in identifying and quantifying different elements present in the cotton fields.

We selected YOLOV8-S from the available YOLOV8 variants. A backbone network is used by YOLOv8-S as the feature extractor. The extraction of hierarchical characteristics from the input image is the responsibility of the backbone. YOLOv8-S often uses the CSPDarknet53 [

14] backbone architecture. To improve information flow, it has a CSP (Cross Stage Partial) connection. It's possible that YOLOv8-S has a neck architecture that combines characteristics of several sizes. In YOLOv8 variations, PANet (Path Aggregation Network) [

15] is frequently employed for this purpose. For object detection, the detection head is in charge of estimating bounding boxes, class probabilities, and confidence ratings. A modified version of the YOLO head is used by YOLOv8-S, which makes multiple-scale predictions for bounding box coordinates, class probabilities, and confidence ratings.

Training the model involves utilizing targets such as bounding box regression, class prediction, and object prediction. In order to introduce non-linearity, YOLOv8-S usually utilizes Leaky ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) [

16] activation functions. Non-maximum suppression (NMS) is used by YOLOv8-S to further refine and filter the final set of bounding box predictions once they are created. YOLOv8-S generates bounding boxes with corresponding class probabilities and confidence ratings based on an input picture. YOLOv8-S is trained utilizing methods like backpropagation and stochastic gradient descent (SGD) on labelled datasets. This particular model can be effectively implemented on devices with constrained resources because of its high computational efficiency.

Autonomous Robot

For a range of robotic applications, the autonomous Clearpath Husky robot is a robust and adaptable unmanned ground vehicle. Because of its characteristics, it's ideal for jobs like data collecting, mapping, and exploration in difficult areas. The robot can see and navigate its environment well since it is outfitted with a variety of sensors, such as a RealSense camera and LiDAR (

Figure 5). Constructed to smoothly interface with the Robot Operating System (ROS), allowing ROS packages and libraries to be used in the creation and implementation of sophisticated robotic applications. The Clearpath Husky is a dependable and flexible autonomous robotic platform because of its sturdy hardware, interoperability with ROS, and autonomous capabilities.

In order to ensure compatibility with ROS Noetic, we constructed and configured the Clearpath Husky robot hardware and attached a LiDAR sensor for autonomous driving. Integrated sensors into the ROS Noetic framework by configuring their drivers and ensuring compatibility with ROS Noetic nodes. Created an environment map using the GMapping mapping solution, which is compatible with ROS Noetic. After that the AMCL (Adaptive Monte Carlo Localization) module from ROS Noetic to implement localization [

17]. Object avoidance pre-trained model and ROS navigation stack for ROS Noetic were used for path planning. Before deploying the robot, we tested it in a controlled environment and made sure the algorithms had been verified and improved using Gazebo simulation tools.

For the purpose of calculating the NDVI, take pictures of the cotton fields using drones that are fitted with multispectral cameras. Incorporate this data into the robot’s navigation system so that it can make well-informed decisions. Utilize our object detection model to discover and enumerate cases of illnesses or infestations of pink bollworms that impact cotton crops. Ascertain a smooth interface with the ROS architecture. Following a simulated test, Deploy the self-navigating Husky robot in actual cotton fields to enable it to independently traverse, and gather information, while monitoring the agricultural conditions. Robot deployment data collection includes gathering information about environmental conditions (done by mapping), detection outcomes, and NDVI maps. This information will be analysed to assist in determining crop health and other issues.

NDVI and Path Planning

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) is a remote sensing tool that evaluates the density and overall health of plants. It is computed by first normalizing the difference between the visible red and near-infrared (NIR) reflectance of a plant by adding their total reflectance as depicted in eq(1). Drones were used to capture multispectral photographs of the whole field at a height of around 25 meters in order to calculate the NDVI.

Path planning for the Husky robot depends on the NDVI calculation (

Figure 6), which is accomplished using the Raster Calculator in QGIS. To ensure accurate detection and counting, the robot's speed is constrained to less than 0.5 m/s. For large-field scenarios, an effective route can be designed that gives priority to areas with healthy crops, and then to areas with moderately healthy crops. This strategic approach allows the robot to optimize its scanning by detecting and counting in healthy crop regions initially, strategically bypassing unhealthy areas. The robot then goes back and carefully checks any areas it may have overlooked before, making sure the whole field is evaluated in a systematic and thorough manner. This path planning approach maximizes the robot's operating speed while concentrating on locations that may have problems, improving the effectiveness of agricultural monitoring.

Results and Discussion

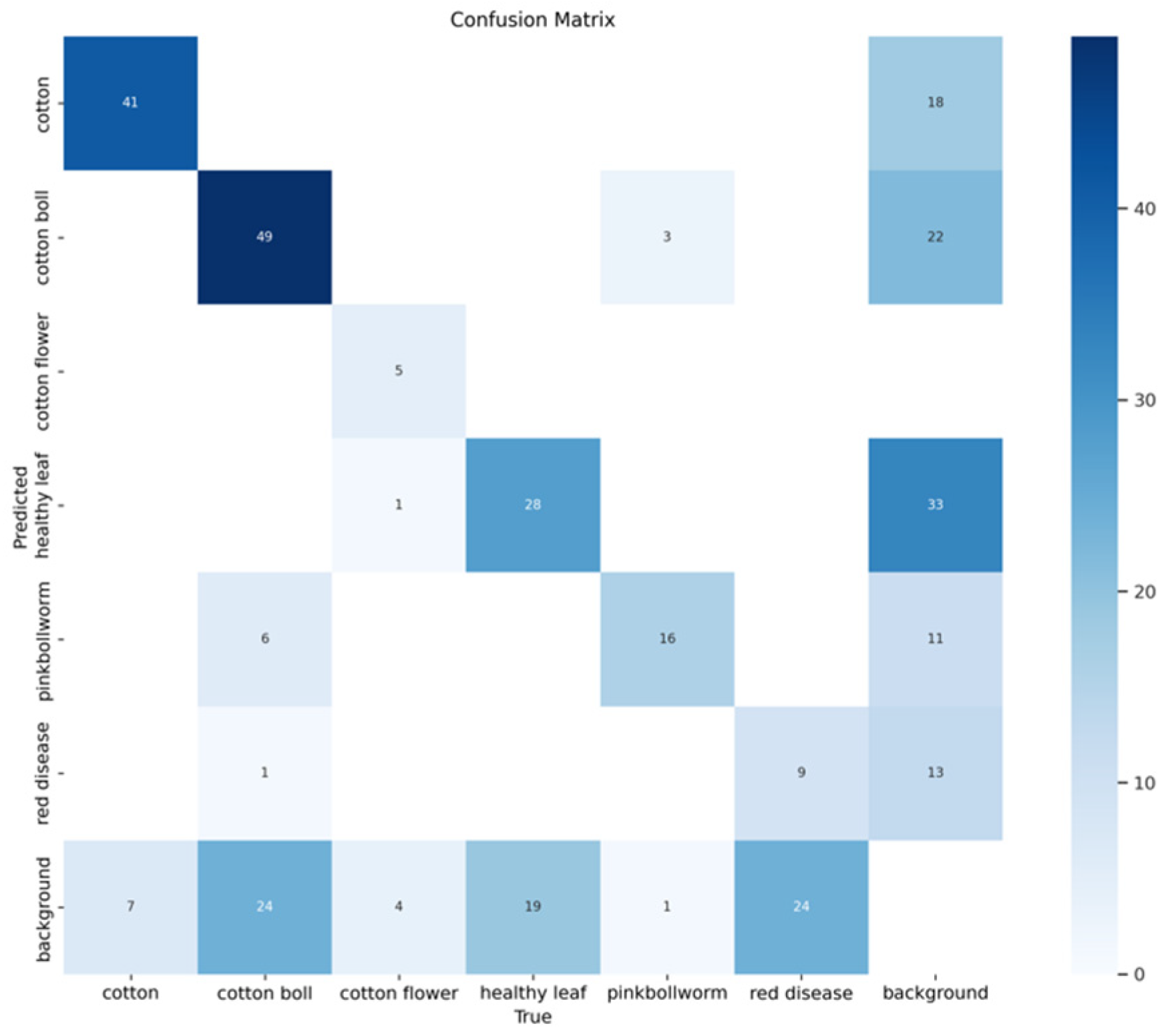

After being trained on a specially created dataset designed for accurate cotton crop monitoring, the YOLOv8 model showed encouraging results. The accuracy of the individual classes can be seen below in the Confusion Matrix (

Figure 7). All of the cells in the matrix indicate how many examples there are of a certain type. Correct predictions are shown by diagonal elements (from top-left to bottom-right), whereas mistakes are indicated by off-diagonal elements. The confusion matrix may be used for a thorough evaluation of the model's performance across various object classes.

As visible in

Figure 8 the graphs provide us with various graphs and plots to visualize and assess its performance in object detection tasks which include The Loss Curve a dynamic visual aid that illustrates the model's training progress by showing how accuracy increases with epochs via decreasing loss. A key factor in maximizing model convergence is the learning rate's evolution throughout training, which is illustrated by the learning rate curve. The precision-recall curve serves as an illustration of average precision (AP), highlighting the trade-off between recall and accuracy. Higher AP values imply better model performance. This assessment is further integrated across all classes by the mean Average Precision (mAP), which provides information about the overall efficacy of the model. With a balanced curve that denotes reliable object identification at all levels, the recall-precision curve graphically depicts the complex link between recall and accuracy. To help identify misclassifications, the Confusion Matrix offers a concise assessment of the model's classification performance. A thorough evaluation of the YOLO model's detection ability is provided by the ROC Curve, which compares the true positive rate to the false positive rate, and the F1 Score Curve, which shows the harmonic mean of accuracy and recall.

Furthermore, the resultant system's robustness and dependability were improved by using Roboflow for model testing. Metrics showing the model's balanced and efficient performance included a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 67.1\%, Precision at 67.9%, and Recall at 61.8%.

As shown in

Table 2 the Husky robot was placed in two distinct types of cotton fields, with testing rows of around 20 meters long. The robot's camera was positioned at a height of 60 cm for best visibility during real-time detection while moving at a speed of 0.5 meters per second. The detection findings were rigorously compared to hand counts of cotton bolls and infected cotton bolls and validated against earlier NDVI estimations generated from drone footage for route planning. The average accuracy of the detection model was then obtained for each field by averaging the accuracy values across all rows. The B.T. Cotton Field had an average accuracy of 76.04%, but the Organic Cotton Field had an average of 67.54%. These results highlight the usefulness of the robotic system.

Detecting "Healthy Leaf" may appear unnecessary, given that the primary purpose is to detect infected cotton bolls, and incorporating this category can result in a huge number of unnecessary detections, which could overwhelm the system. The method can provide a baseline for comparison and help detect diseased or pest-infested plant patches. While "Healthy Leaf" detection is not critical for this specific application, establishing a method for monitoring diseases and pests that can be applied to any crop is critical for larger agricultural applications.

The dataset created for this application was inadequate, limiting the trained model's performance. Additionally, GPU limitations hindered optimal training capacity. These constraints underscore the need for more comprehensive datasets and enhanced computational resources to realize the model's full potential.

Through the integration of state-of-the-art technologies, such as drone-based multispectral photography, NDVI-based path planning, and YOLOv8 object recognition, this research provides an achievable solution. Deployed autonomous robot with an effective detection model helps farmers make fast and accurate decisions, potentially reducing losses from crop illnesses and pink bollworm infestations. The attained outcomes highlight the efficacy of the suggested approach, opening the door for developments in autonomous agricultural robots for crop management and protection.

Conclusion

The combination of autonomous robots, ROS, drones, and sophisticated detection algorithms offers a viable option for effective crop protection, notably against pink bollworm infestations and crop diseases in cotton farming. The Husky robot's deployment in two separate cotton fields confirmed the system's practical usefulness, with the detection model achieving an average accuracy of 76.04% in B.T. Cotton Fields and 67.54% in Organic Cotton Fields. These findings demonstrate the robotic system's ability to reliably identify and measure cotton bolls, as well as detect pink bollworm infections. Moving ahead, additional improvement of dataset level and computing resources will be critical to maximizing the model's potential and promoting sustainable agriculture methods.

In future research, we hope to broaden the application of the proposed technique to diverse crops, allowing for a comparative evaluation of the model's performance across various agricultural situations. This comparison study will help to understand the detection system's flexibility and generalizability. Furthermore, because the cotton fields tested were very small, future research will include wider field testing to gather more comprehensive data for NDVI route design. This enhanced dataset will allow for a more complete examination of path planning efficacy, as well as the discovery of any tweaks or enhancements required to maximize the system's performance. By carrying out these studies, we can modify and improve the technique to match the particular issues and requirements of different crop types, ultimately advancing the capabilities of autonomous crop monitoring and protection systems.

Acknowledgment

A sincerely thank the National Agricultural Higher Education Project (NAHEP) for their indispensable assistance and for providing of necessary materials. Critical sensors, drones, and the Clearpath Husky robot have all been made available, which has made the research efforts far more fruitful. Furthermore, the cooperative chance to work on the Husky ROS codes that NAHEP offered was crucial to our model's testing and verification processes and greatly enhanced its overall effectiveness.

References

- Tabashnik, Bruce E., et al. "Frequency of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis in field populations of pink bollworm." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97.24 (2000): 12980-12984. [CrossRef]

- Tabashnik, Bruce E., Timothy J. Dennehy, and Yves Carrière. "Delayed resistance to transgenic cotton in pink bollworm." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102.43 (2005): 15389-15393. [CrossRef]

- Lippi, Martina, et al. "A yolo-based pest detection system for precision agriculture." 2021 29th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED). IEEE, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Liu, et al. "PestNet: An end-to-end deep learning approach for large-scale multi-class pest detection and classification." Ieee Access 7 (2019): 45301-45312. [CrossRef]

- Dang, Fengying, et al. "YOLOWeeds: a novel benchmark of YOLO object detectors for multi-class weed detection in cotton production systems." Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 205 (2023): 107655. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Zhang Y, Yang G. Small unopened cotton boll counting by detection with MRF-YOLO in the wild. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 2023 Jan 1;204:107576. [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, Apurva R., Shweta B. Solanke, and Gopal U. Shinde. "IOT for precision Agriculture: A Review".

- Khatri, Narendra, and Gopal U. Shinde. "Computer Vision and Image Processing for Precision Agriculture." Cognitive Behavior and Human Computer Interaction Based on Machine Learning Algorithm (2021): 241-263. [CrossRef]

- Henninger, Helen, and Karl von Ellenrieder. "Generating maneuverable trajectories for a reconfigurable underactuated agricultural robot." 2021 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Agriculture and Forestry (MetroAgriFor). IEEE, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Boeing, Adrian, et al. "WAMbot: Team MAGICian’s entry to the Multi Autonomous Ground-robotic International Challenge 2010." Journal of Field Robotics 29.5 (2012): 707-728. [CrossRef]

- Reid, Robert, et al. "Cooperative multi-robot navigation, exploration, mapping and object detection with ROS." 2013 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV). IEEE, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mwitta C, Rains GC. The integration of GPS and visual navigation for autonomous navigation of an Ackerman steering mobile robot in cotton fields. Frontiers in Robotics and AI. 2024 Apr 12;11:1359887. [CrossRef]

- Fue, Kadeghe G., Edward M. Barnes, Wesley M. Porter, and Glen C. Rains. "Visual control of cotton-picking Rover and manipulator using a ROS-independent finite state machine." In 2019 ASABE Annual International Meeting, p. 1. American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mahasin, Marsa, and Irma Amelia Dewi. "Comparison of CSPDarkNet53, CSPResNeXt-50, and EfficientNet-B0 Backbones on YOLO V4 as Object Detector." International Journal of Engineering, Science and Information Technology 2.3 (2022): 64-72. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Kaixin, et al. "Panet: Few-shot image semantic segmentation with prototype alignment." proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. 2019.

- Chen, Yinpeng, et al. "Dynamic relu." European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Baoxian, Jun Liu, and Haoyao Chen. "AMCL based map fusion for multi-robot SLAM with heterogenous sensors." 2013 IEEE International Conference on Information and Automation (ICIA). IEEE, 2013. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).