Submitted:

02 December 2023

Posted:

04 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

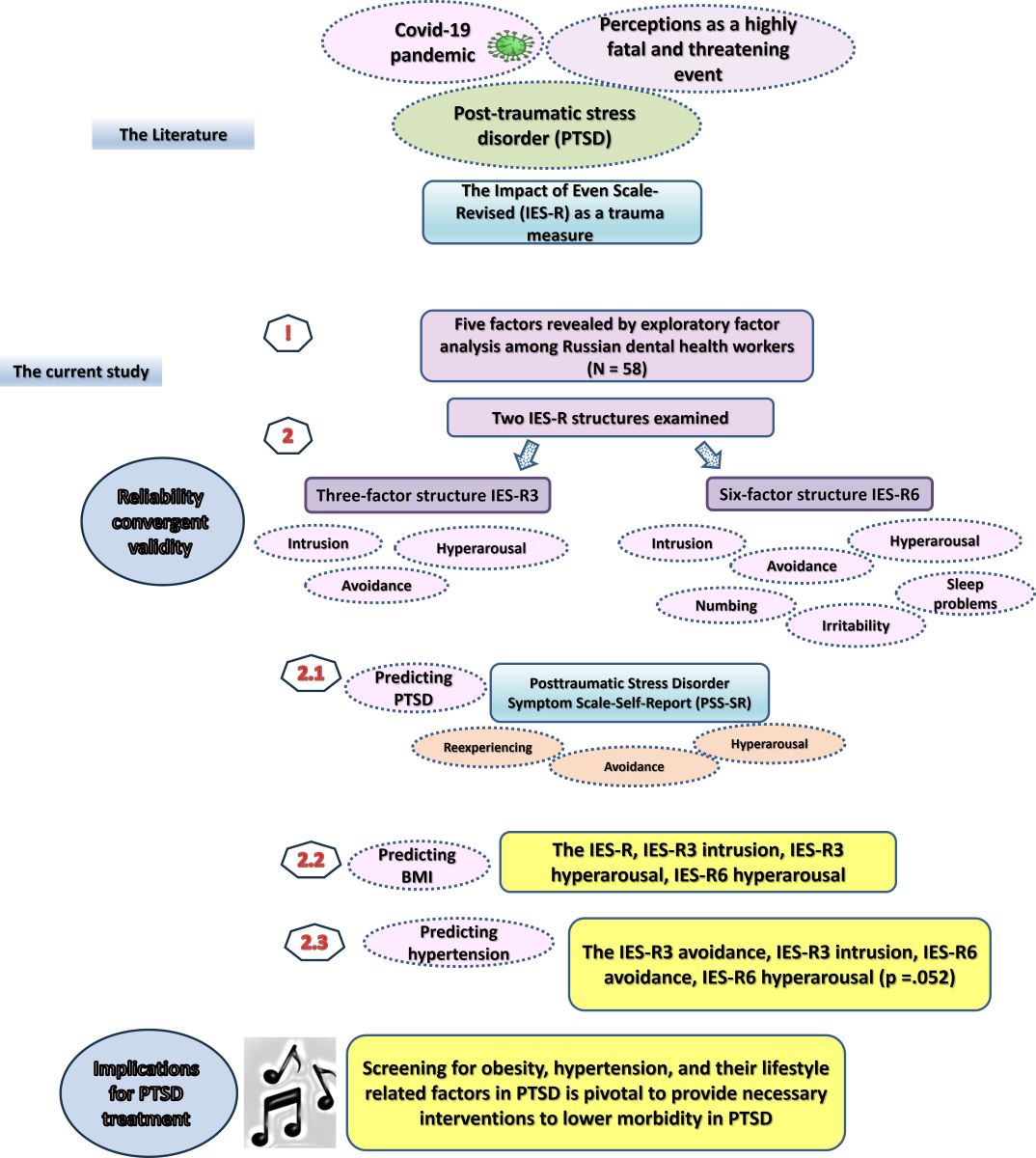

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design and participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical analysis

3. Results

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. IES-R | -- | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. T-Avoidance | .916** | -- | |||||||||||||||

| 3. T-Intrusion | .903** | .792** | -- | ||||||||||||||

| 4. T-Hyperarousal | .893** | .721** | .768** | -- | |||||||||||||

| 5. S-Avoidance | .870** | .977** | .727** | .668** | -- | ||||||||||||

| 6. S-Intrusion | .861** | .786** | .960** | .706** | .733** | -- | |||||||||||

| 7. S-Numbing | .788** | .783** | .788** | .710** | .680** | .723** | -- | ||||||||||

| 8. S-Hyperarousal | .878** | .804** | .793** | .892** | .764** | .753** | .761** | -- | |||||||||

| 9. S-Sleep | .797** | .604** | .704** | .870** | .560** | .591** | .631** | .693** | -- | ||||||||

| 10. S-Irritability 11. PSS-SR 12. PSS_Avoidance 13. PSS_Arousal 14.PSS_Reexperiencing 15. BMI 16. Hypertension 17. Smoking |

.621** .642** .545** .630** .494** 0.250 0.245 0.034 |

.528** .516** .463** .469** .437** 0.185 .295* -0.074 |

.595** .692** .586** .646** .576** .303* .294* 0.038 |

.684** .573** .414** .644** .393** .276* 0.193 0.040 |

.485** .486** .453** .432** .404** 0.146 .286* -0.049 |

.558** .619** .576** .570** .501** .299* 0.257 0.019 |

.526** .542** .402** .510** .514** 0.240 .293* -0.201 |

.627** .579** .419** .568** .479** .390** .287* 0.037 |

.449** .589** .416** .658** .411** 0.106 0.123 -0.056 |

-- .416** .375** .471** 0.190 0.205 0.253 .279* |

-- .879** .904** .773** 0.009 0.177 .279* |

-- .719** .587** -0.008 0.166 .328* |

-- .564** -0.041 0.076 0.242 |

-- 0.200 0.251 0.125 |

-- .344** -0.116 |

-- -0.151 |

-- |

| Median | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | 0 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 26.8▪ | 14• | 10• |

| Q1 – Q3 | 0 – 13.0 | 0 – 6.0 | 0 – 5.3 | 0 – 4.0 | 0 – 5.0 | 0 – 4.0 | 0 – 2.0 | 0 – 2.0 | 0 – 2.0 | 0 – 1.0 | 1 – 11.0 | 0 – 6.3 | 0 – 5.3 | 0 – 4.0 | 5.2▪ | 24.1%• | 17.2%• |

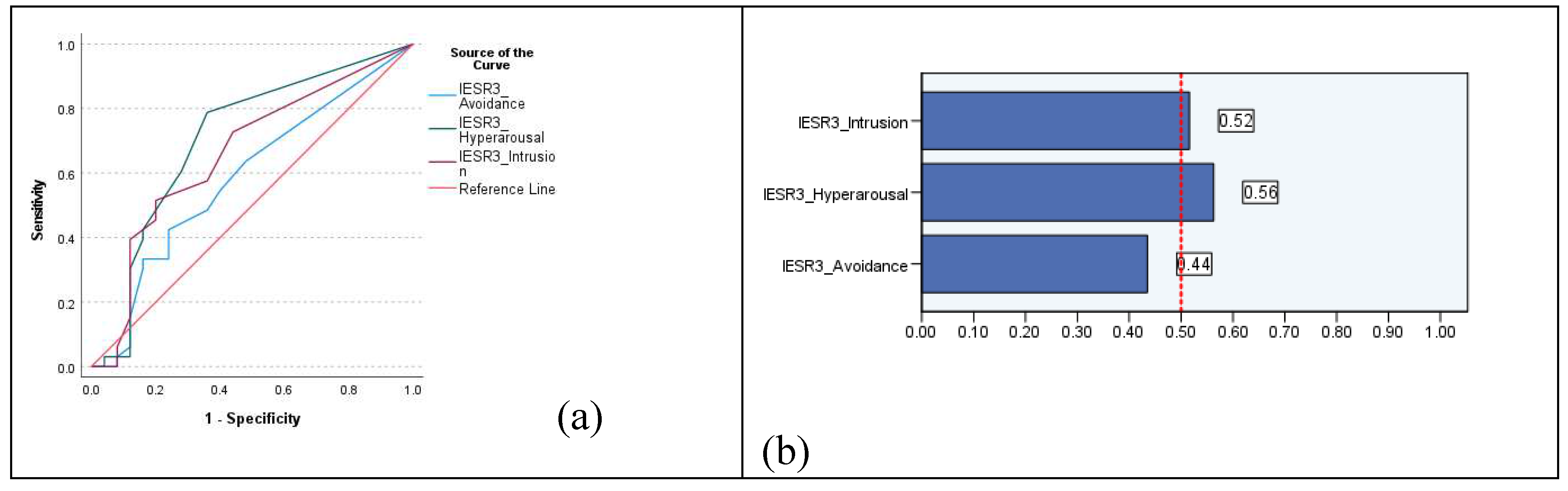

| Sample | AUC | SE | AUC 95% CI | Cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IES-R | PSS-SR | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 to 1.01 | 39.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Obesity | 0.67 | 0.08 | 0.52 to 0.82 | 5.5 | 0.64 | 0.72 | 0.36 | |

| Hypertension | 0.66 | 0.10 | 0.48 to 0.85 | 17.5 | 0.50 | 0.91 | 0.41 | |

| IES-R3-Avoidance | PSS-SR | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 12.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Obesity | 0.59 | 0.08 | 0.44 to 0.74 | 3.5 | 0.42 | 0.76 | 0.18 | |

| Hypertension | 0.69 | 0.09 | 0.52 to 0.87 | 3.5 | 0.57 | 0.73 | 0.30 | |

| IES-R3-Intrusion | PSS-SR | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 14.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Obesity | 0.66 | 0.07 | 0.52 to 0.81 | 2.5 | 0.52 | 0.80 | 0.32 | |

| Hypertension | 0.69 | 0.09 | 0.52 to 0.86 | 6.5 | 0.50 | 0.91 | 0.41 | |

| IES-R3-Hyperarousal | PSS-SR | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.97 to 1.01 | 10.5 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Obesity | 0.71 | 0.07 | 0.56 to 0.84 | 0.5 | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.43 | |

| Hypertension | 0.63 | 0.10 | 0.44 to 0.81 | 6.5 | 0.43 | 0.87 | 0.32 | |

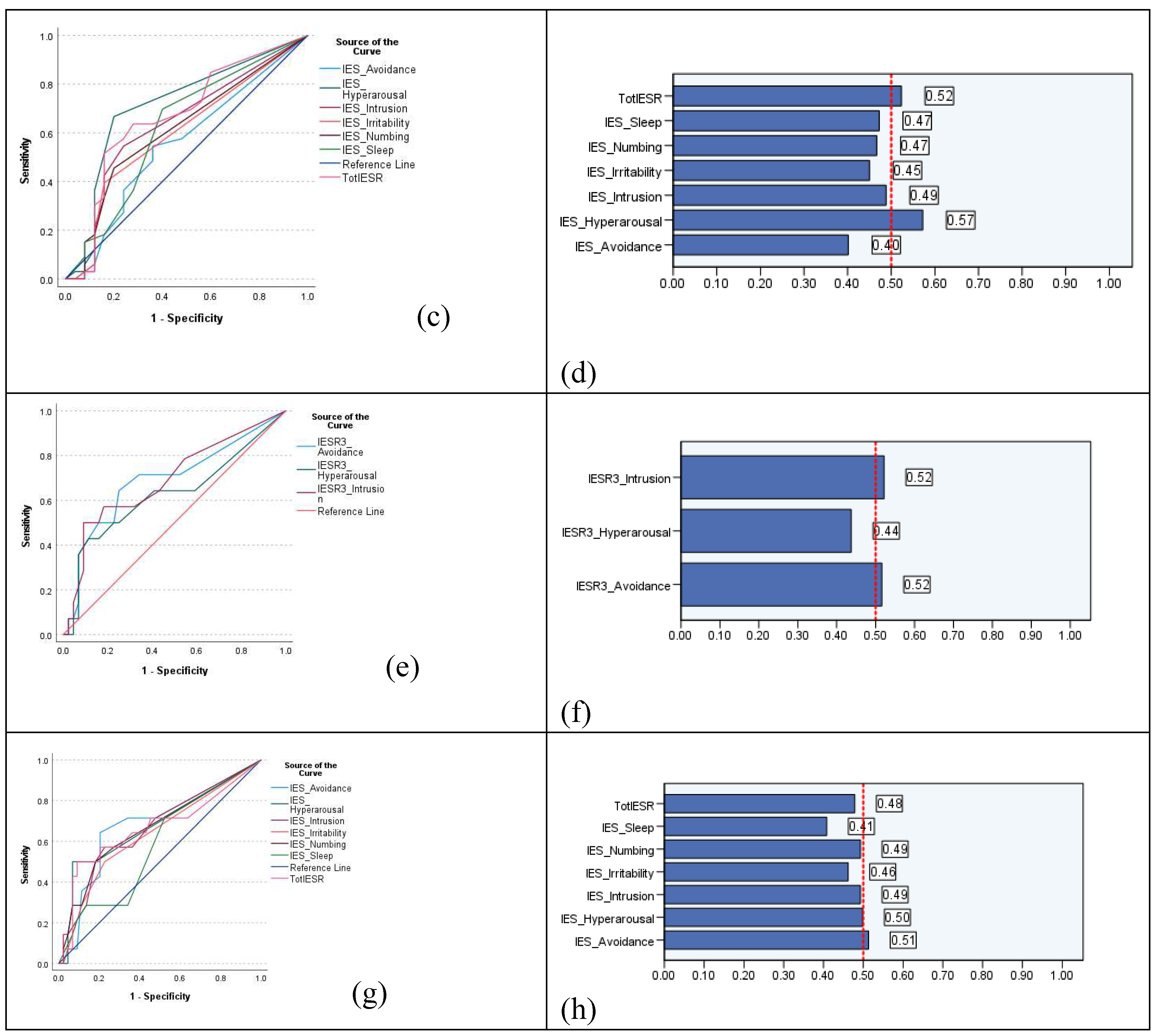

| IES-R6-Avoidance | PSS-SR | 1.00 | 0.008 | 0.98 to 1.01 | 7.5 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Obesity | 0.55 | 0.08 | 0.40 to 0.71 | 1.5 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.19 | |

| Hypertension | 0.68 | 0.09 | 0.51 to 0.85 | 3.5 | 0.64 | 0.80 | 0.44 | |

| IES-R6-Intrusion | PSS-SR | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 8.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Obesity | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.49 to 0.79 | 1.5 | 0.55 | 0.76 | 0.31 | |

| Hypertension | 0.66 | 0.09 | 0.49 to 0.84 | 2.5 | 0.57 | 0.77 | 0.34 | |

| IES-R6-Numbing | PSS-SR | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 6.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Obesity | 0.62 | 0.08 | 0.47 to 0.76 | 0.5 | 0.46 | 0.80 | 0.26 | |

| Hypertension | 0.66 | 0.09 | 0.49 to 0.84 | 1.5 | 0.50 | 0.81 | 0.31 | |

| IES-R6-Hyperarousal | PSS-SR | 0.99 | 0.02 | 0.96 to 1.01 | 7.0 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Obesity | 0.71 | 0.07 | 0.57 to 0.85 | 0.5 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.47 | |

| Hypertension | 0.68 | 0.09 | 0.50 to 0.86 | 3.5 | 0.29 | 0.93 | 0.22 | |

| IES-R6-Sleep | PSS-SR | 0.98 | 0.02 | 0.93 to 1.01 | 5.5 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| Obesity | 0.62 | 0.08 | 0.47 to 0.77 | 0.5 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.30 | |

| Hypertension | 0.58 | 0.09 | 0.41 to 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.71 | 0.48 | 0.19 | |

| IES-R6-Irritability | PSS-SR | 0.99 | 0.02 | 0.95 to 1.02 | 2.5 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| Obesity | 0.60 | 0.08 | 0.45 to 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.39 | 0.84 | 0.23 | |

| Hypertension | 0.64 | 0.09 | 0.46 to 0.81 | 0.5 | 0.50 | 0.77 | 0.27 |

4. Discussion

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgement

Competing interests

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

References

- Nagarajan, R.; Krishnamoorthy, Y.; Basavarachar, V.; Dakshinamoorthy, R. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among survivors of severe COVID-19 infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2022, 299, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. 2022.

- Moore, S.A.; Zoellner, L.A.; Mollenholt, N. Are expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal associated with stress-related symptoms? Behav Res Ther 2008, 46, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, O.; Willmund, G.; Gleich, T.; Zimmermann, P.; Lindenberger, U.; Gallinat, J.; Kühn, S. Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression of Negative Emotion in Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Functional MRI Study. Cognit Ther Res 2019, 43, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Alameri, R.A.; Brooks, T.; Ali, T.S.; Ibrahim, N.; Khatatbeh, H.; Pakai, A.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Al-Dossary, S.A. Cut-off scores of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-8: Implications for improving the management of chronic pain. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2023, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadad, N.A.; Schwendt, M.; Knackstedt, L.A. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in post-traumatic stress disorder and cocaine use disorder. Stress 2020, 23, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, L.; Isnard, P. Obesity and PTSD: A review on this association from childhood to adulthood. Neuropsychiatr Enfance Adolesc 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantz, D.S.; Shank, L.M.; Goodie, J.L. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a systemic disorder: Pathways to cardiovascular disease. Health Psychol 2022, 41, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursano, R.J.; Stein, M.B. From Soldier's Heart to Shared Genetic Risk: PTSD and Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Psychiatry 2022, 179, 785–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendlowicz, V.; Garcia-Rosa, M.L.; Gekker, M.; Wermelinger, L.; Berger, W.; Luz, M.P.; Pires-Dias, P.R.T.; Marques-Portela, C.; Figueira, I.; Mendlowicz, M.V. Post-traumatic stress disorder as a predictor for incident hypertension: a 3-year retrospective cohort study. Psychol Med 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapolisi, A.; Maurage, P.; Pappaccogli, M.; Georges, C.M.G.; Petit, G.; Balola, M.; Cikomola, C.; Bisimwa, G.; Burnier, M.; Persu, A.; et al. Association between post-traumatic stress disorder and hypertension in Congolese exposed to violence: a case-control study. J Hypertens 2022, 40, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, D.J.; Kaizer, A.M.; Kinney, A.R.; Bahraini, N.H.; Forster, J.E.; Brenner, L.A. The unique association of posttraumatic stress disorder with hypertension among veterans: A replication of Kibler et al. (2009) using Bayesian estimation and data from the United States-Veteran Microbiome Project. Psychol Trauma 2023, 15, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligowski, A.V.; Misganaw, B.; Duffy, L.A.; Ressler, K.J.; Guffanti, G. Leveraging Large-Scale Genetics of PTSD and Cardiovascular Disease to Demonstrate Robust Shared Risk and Improve Risk Prediction Accuracy. Am J Psychiatry 2022, 179, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swart, P.C.; van den Heuvel, L.L.; Lewis, C.M.; Seedat, S.; Hemmings, S.M.J. A Genome-Wide Association Study and Polygenic Risk Score Analysis of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Metabolic Syndrome in a South African Population. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 677800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misganaw, B.; Yang, R.; Gautam, A.; Muhie, S.; Mellon, S.H.; Wolkowitz, O.M.; Ressler, K.J.; Doyle, F.J., 3rd; Marmar, C.R.; Jett, M.; et al. The Genetic Basis for the Increased Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome among Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Patients. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berk-Clark, C.; Secrest, S.; Walls, J.; Hallberg, E.; Lustman, P.J.; Schneider, F.D.; Scherrer, J.F. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder and lack of exercise, poor diet, obesity, and co-occuring smoking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol 2018, 37, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Kunugi, H. Royal jelly as an intelligent anti-aging—a focus on cognitive aging and Alzheimer's disease: a review. Antioxidants 2020, 9, E937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Hendawy, A.O.; Elhay, E.S.A.; Ali, E.M.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Kunugi, H.; Hassan, N.I. The Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale: Its psychometric properties and invariance among women with eating disorders. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Hori, H.; Kim, Y.; Kunugi, H. Predictors of nutritional status, depression, internet addiction, Facebook addiction, and tobacco smoking among women with eating disorders in Spain. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, M.E.; Qin, X.J.; Mehta, D.; Dennis, M.F.; Marx, C.E.; Grant, G.A.; Stein, M.B.; Kimbrel, N.A.; Beckham, J.C.; Hauser, M.A.; et al. Gene Expression Analysis in Three Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Cohorts Implicates Inflammation and Innate Immunity Pathways and Uncovers Shared Genetic Risk With Major Depressive Disorder. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 678548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Kunugi, H. Apitherapy for age-related skeletal muscle dysfunction (sarcopenia): A review on the effects of royal jelly, propolis, and bee pollen. Foods 2020, 9, E1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Kunugi, H. Screening for sarcopenia (physical frailty) in the COVID-19 era. Int J Endocrinol 2021, 2021, 5563960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliman, S.; Anthonissen, L.; Carr, J.; du Plessis, S.; Emsley, R.; Hemmings, S.M.; Lochner, C.; McGregor, N.; van den Heuvel, L.; Seedat, S. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Overweight, and Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2016, 24, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoli, F.; Crocamo, C.; Alamia, A.; Amidani, F.; Paggi, E.; Pini, E.; Clerici, M.; Carrà, G. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of obesity: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2015, 76, e1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Nepal, B.; Moon, C.S.; Chabenne, A.; Khogali, A.; Ojo, C.; Hong, E.; Gaudet, R.; Sayed-Ahmad, A.; Jacob, A. Psychology of craving. Open Journal of Medical Psychology 2014, 3, 42106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Antonio Bertelloni, C.; Massimetti, G.; Miniati, M.; Stratta, P.; Rossi, A.; Dell׳Osso, L. Impact of DSM-5 PTSD and gender on impaired eating behaviors in 512 Italian earthquake survivors. Psychiatry Res 2015, 225, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmusson, A.M.; Schnurr, P.P.; Zukowska, Z.; Scioli, E.; Forman, D.E. Adaptation to extreme stress: post-traumatic stress disorder, neuropeptide Y and metabolic syndrome. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2010, 235, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Kunugi, H. Physical frailty/sarcopenia as a key predisposing factor to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its complications in older adults. BioMed 2021, 1, 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanovics, E.A.; Potenza, M.N.; Pietrzak, R.H. PTSD and obesity in U.S. military veterans: Prevalence, health burden, and suicidality. Psychiatry Res 2020, 291, 113242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noland, M.D.W.; Paolillo, E.W.; Noda, A.; Lazzeroni, L.C.; Holty, J.C.; Kuschner, W.G.; Yesavage, J.; Kinoshita, L.M. Impact of PTSD and Obstructive Sleep Apnea on Cognition in Older Adult Veterans. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2023, 8919887221149132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Gong, Y.-M.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y.-K.; Tian, S.-S.; Wang, Y.-J.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, A.-Y.; Su, S.-Z.; Liu, X.-X.; et al. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder after infectious disease pandemics in the twenty-first century, including COVID-19: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 4982–4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Elhay, E.S.A.; Taha, S.M.; Hendawy, A.O. COVID-19-related psychological trauma and psychological distress among community-dwelling psychiatric patients: people struck by depression and sleep disorders endure the greatest burden. Frontiers in Public Health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Ettorre, G.; Ceccarelli, G.; Santinelli, L.; Vassalini, P.; Innocenti, G.P.; Alessandri, F.; Koukopoulos, A.E.; Russo, A.; d’Ettorre, G.; Tarsitani, L. Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Healthcare Workers Dealing with the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatatbeh, H.; Al-Dwaikat, T.; Alfatafta, H.; Ali, A.M.; Pakai, A. Burnout, quality of life and perceived patient adverse events among paediatric nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Nurs 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, G.S.S.; Lee, H.Y.; Leong, J.Z.; Sulaiman, M.M.; Loo, W.F.; Tan, W.W. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among dental students and dental practitioners: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0267354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles-Pérez, E.; González-Díaz, B.; Miranda-García, M.; Borja-Aburto, V.H. Infection and death by COVID-19 in a cohort of healthcare workers in Mexico. Scand J Work Environ Health 2021, 47, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Al-Amer, R.; Kunugi, H.; Stănculescu, E.; Taha, S.M.; Saleh, M.Y.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Hendawy, A.O. The Arabic version of the Impact of Event Scale – Revised: Psychometric evaluation in psychiatric patients and the general public within the context of COVID-19 outbreak and quarantine as collective traumatic events. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022, 12, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Al-Dossary, S.A.; Almarwani, A.M.; Atout, M.; Al-Amer, R.; Alkhamees, A.A. The Impact of Event Scale – Revised: Examining its cutoff scores among Arab psychiatric patients and healthy adults within the context of COVID-19 as a collective traumatic event. Healthcare 2023, 11, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarapultsev, A.; Zolotareva, A.; Berdugina, O. BMI and PTSD among HCWs. Mendeley Data 2021, V1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarapultseva, M.; Zolotareva, A.; Kritsky, I.; Nasretdinova, N.y.; Sarapultsev, A. Psychological Distress and Post-Traumatic Symptomatology among Dental Healthcare Workers in Russia: Results of a Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E.B.; McLean, C.P.; Zang, Y.; Zhong, J.; Rauch, S.; Porter, K.; Knowles, K.; Powers, M.B.; Kauffman, B.Y. Psychometric properties of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale Interview for DSM-5 (PSSI-5). Psychol Assess 2016, 28, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargurevich, R.; Luyten, P.; Fils, J.F.; Corveleyn, J. Factor structure of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised in two different Peruvian samples. Depress Anxiety 2009, 26, E91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morina, N.; Böhme, H.F.; Ajdukovic, D.; Bogic, M.; Franciskovic, T.; Galeazzi, G.M.; Kucukalic, A.; Lecic-Tosevski, D.; Popovski, M.; Schützwohl, M.; et al. The structure of post-traumatic stress symptoms in survivors of war: confirmatory factor analyses of the Impact of Event Scale--revised. J Anxiety Disord 2010, 24, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyball, D.; Bennett, A.N.; Schofield, S.; Cullinan, P.; Boos, C.J.; Bull, A.M.J.; Stevelink, S.A.M.; Fear, N.T. The underlying mechanisms by which PTSD symptoms are associated with cardiovascular health in male UK military personnel: The ADVANCE cohort study. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2023, 159, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooldridge, J.S.; Herbert, M.S.; Dochat, C.; Afari, N. Understanding relationships between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, binge-eating symptoms, and obesity-related quality of life: the role of experiential avoidance. Eating Disorders 2021, 29, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobbs, O.; Crépin, C.; Thiéry, C.; Golay, A.; Van der Linden, M. Obesity and the four facets of impulsivity. Patient Educ Couns 2010, 79, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, T.L.; Ramirez, E.; Kwarteng, E.A.; Djan, K.G.; Faulkner, L.M.; Parker, M.N.; Yang, S.B.; Zenno, A.; Kelly, N.R.; Shank, L.M.; et al. Retrieval-induced forgetting in children and adolescents with and without obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2022, 46, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, S.; Stubbs, B.; Ward, P.B.; Steel, Z.; Lederman, O.; Vancampfort, D. The prevalence and risk of metabolic syndrome and its components among people with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism 2015, 64, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huai, P.; Liu, J.; Ye, X.; Li, W.Q. Association of Central Obesity With All Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality in US Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 816144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alpha | Alpha if item deleted | Item total correlations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IES-R | 0.95 | 0.946 to 0.951 | 0.48 to 0.83 |

| T-Avoidance | 0.84 | 0.81 to 0.84 | 0.46 to 0.64 |

| T-Intrusion | 0.88 | 0.85 to 0.88 | 0.46 to 0.85 |

| T-Hyperarousal | 0.86 | 0.82 to 0.88 | 0.39 to 0.81 |

| S-Avoidance | 0.75 | 0.67 to 0.72 | 0.46 to 0.59 |

| S-Intrusion | 0.81 | 0.72 to 0.80 | 0.47 to 0.77 |

| S-Numbing | 0.83 | 0.72 to 0.87 | 0.48 to 0.80 |

| S-Hyperarousal | 0.88 | 0.67 to 0.72 | 0.81 to 0.87 |

| S-Sleep | 0.84 | - | 0.72 |

| S-Irritability | 0.69 | - | 0.52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).