Submitted:

01 December 2023

Posted:

01 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The eosinophil

1.2. Eosinophil biological activity

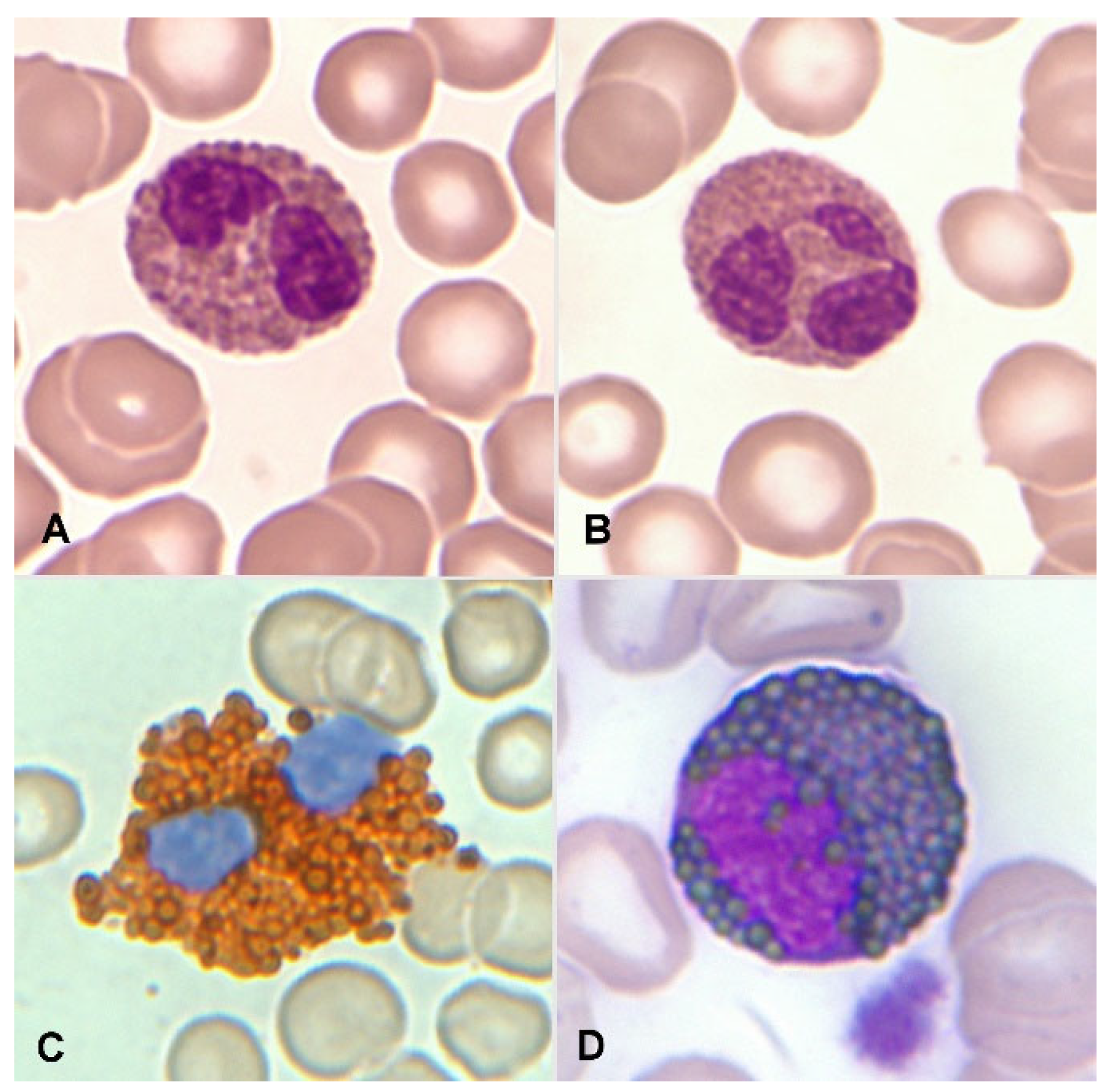

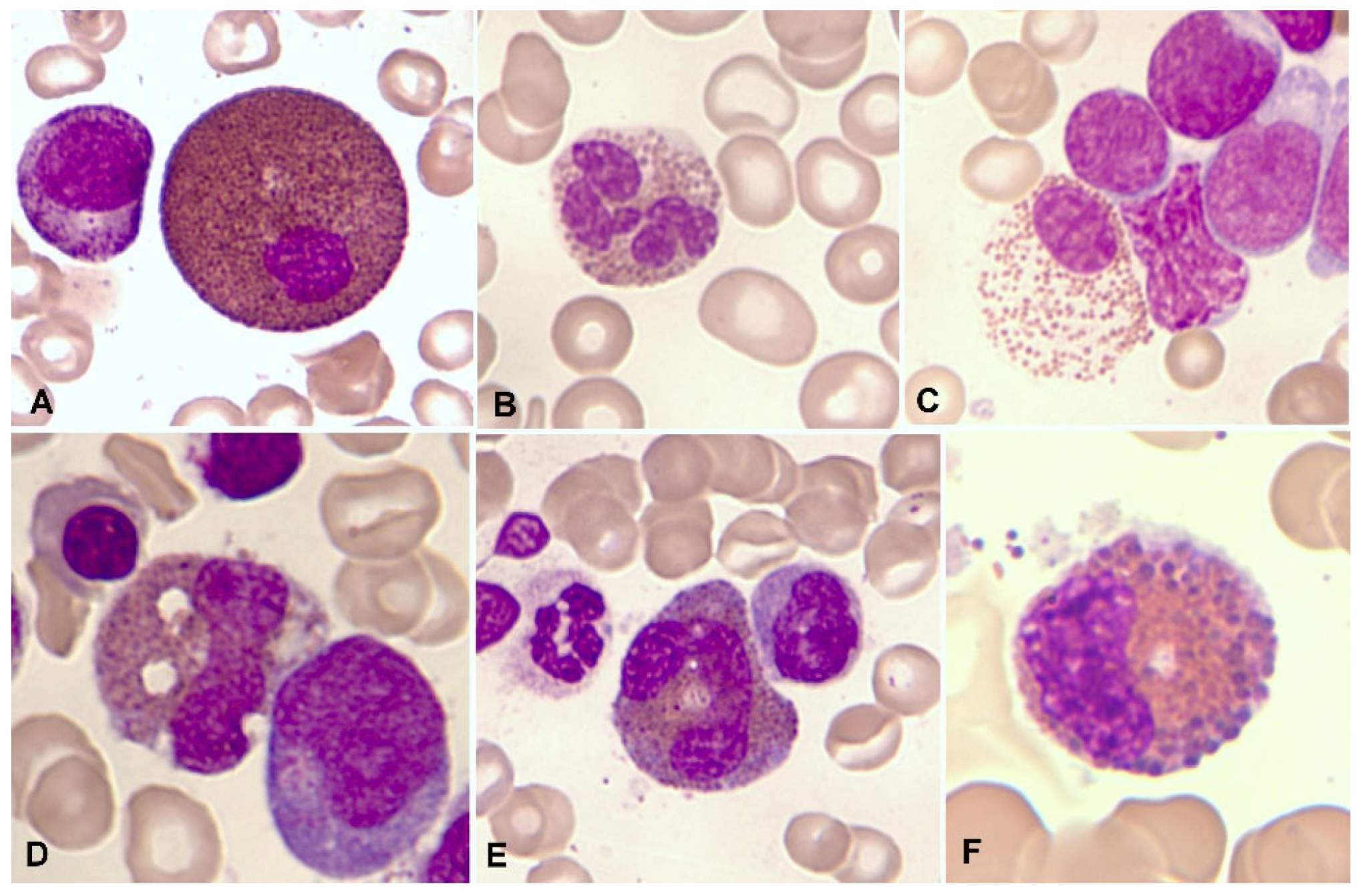

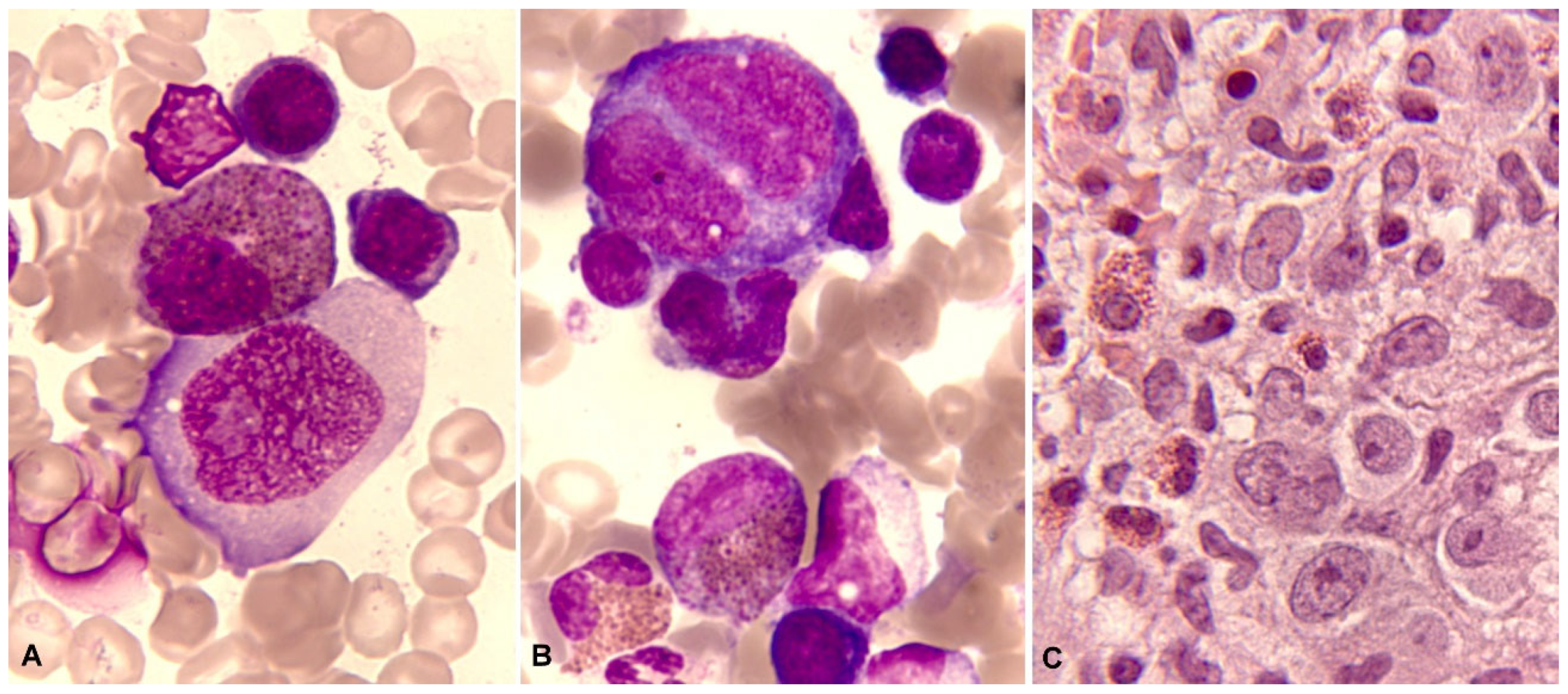

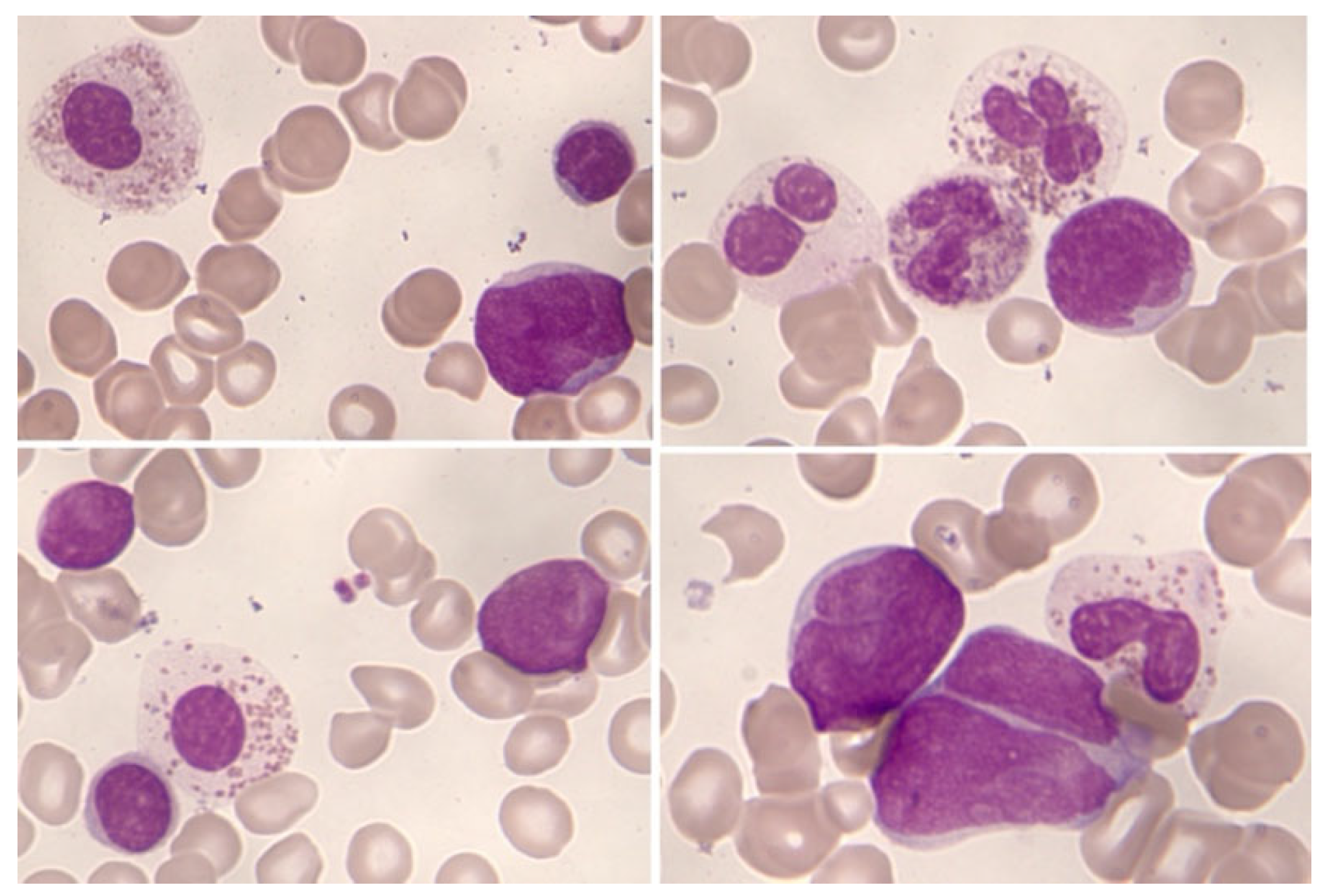

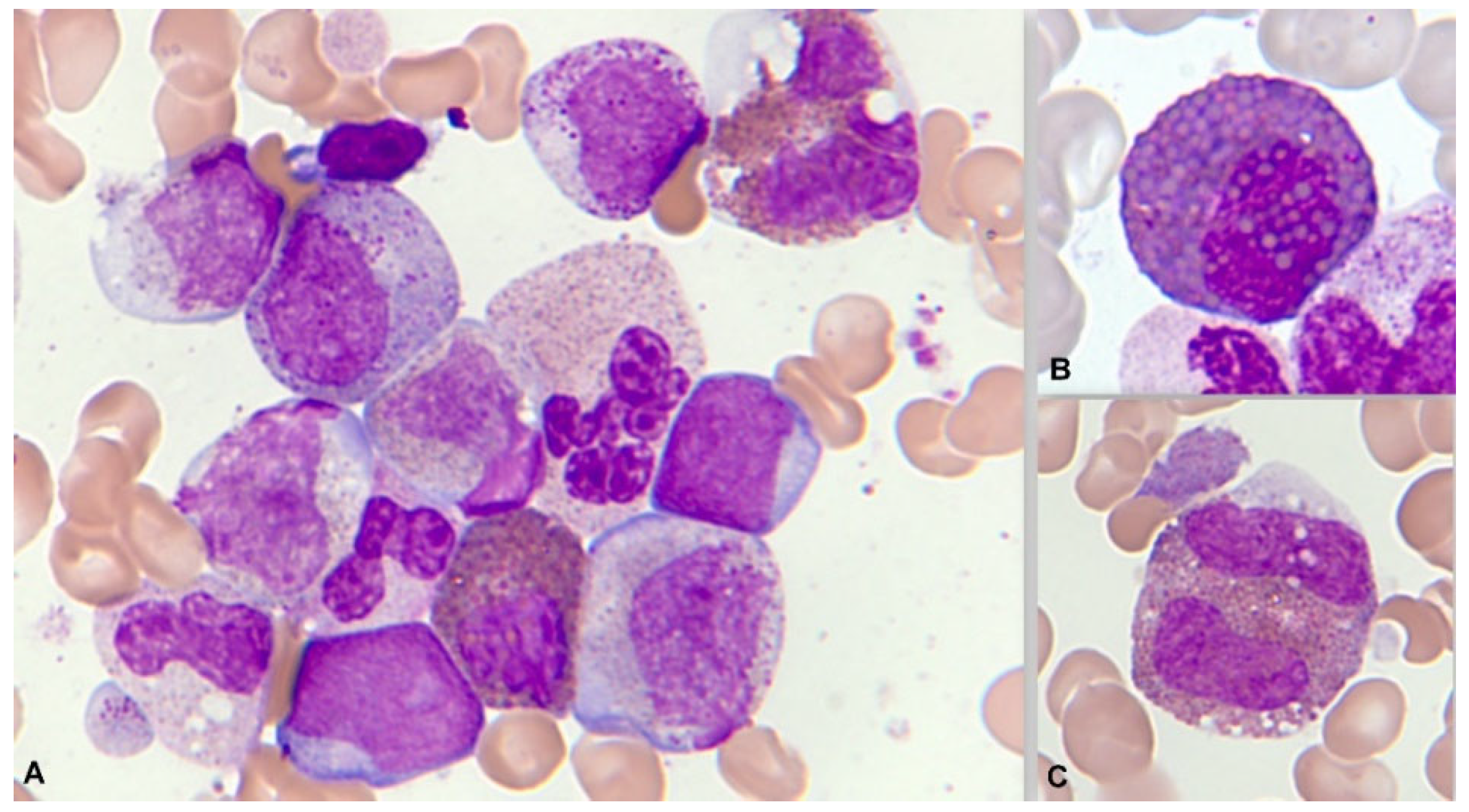

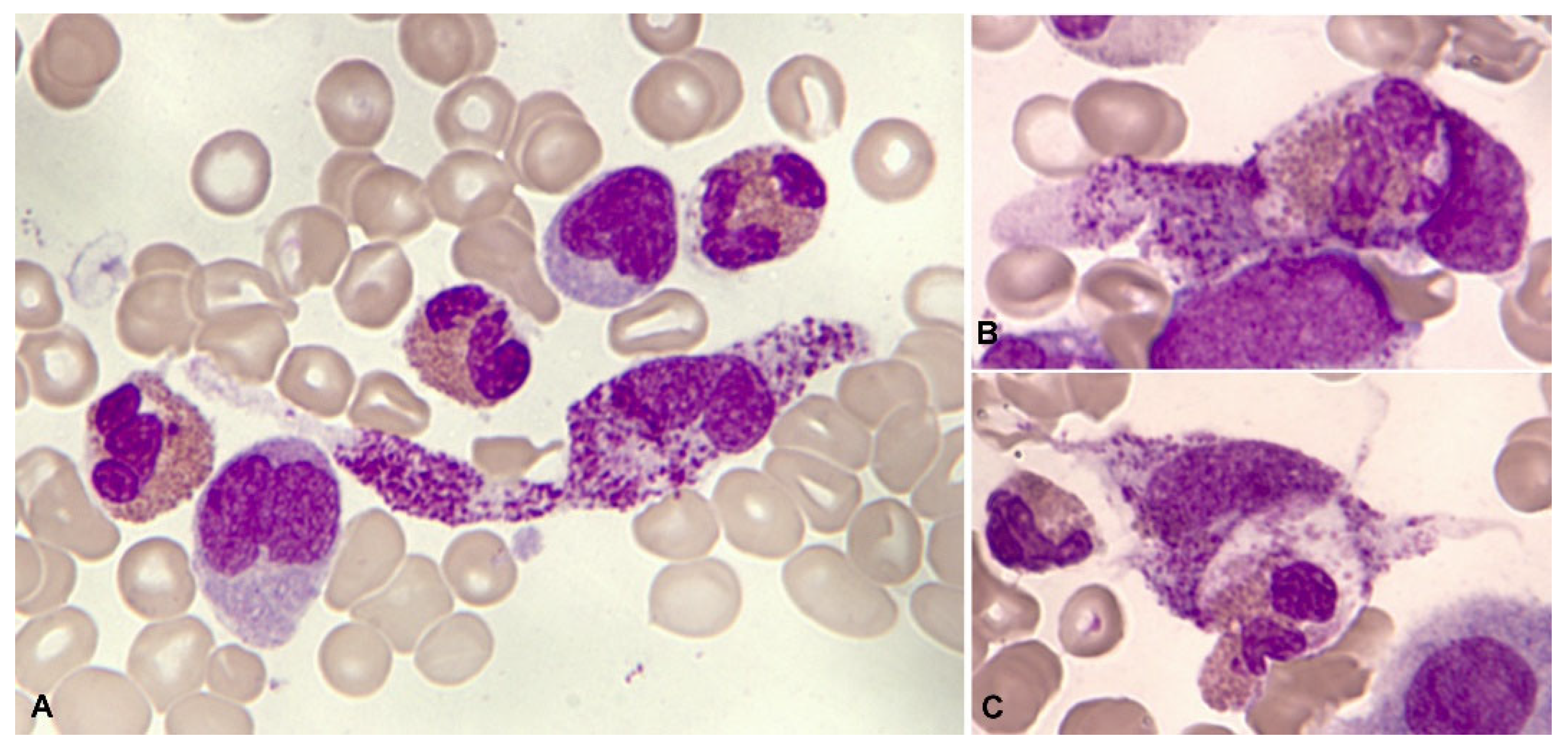

1.3. Normal and Pathological Morphology of Eosinophils

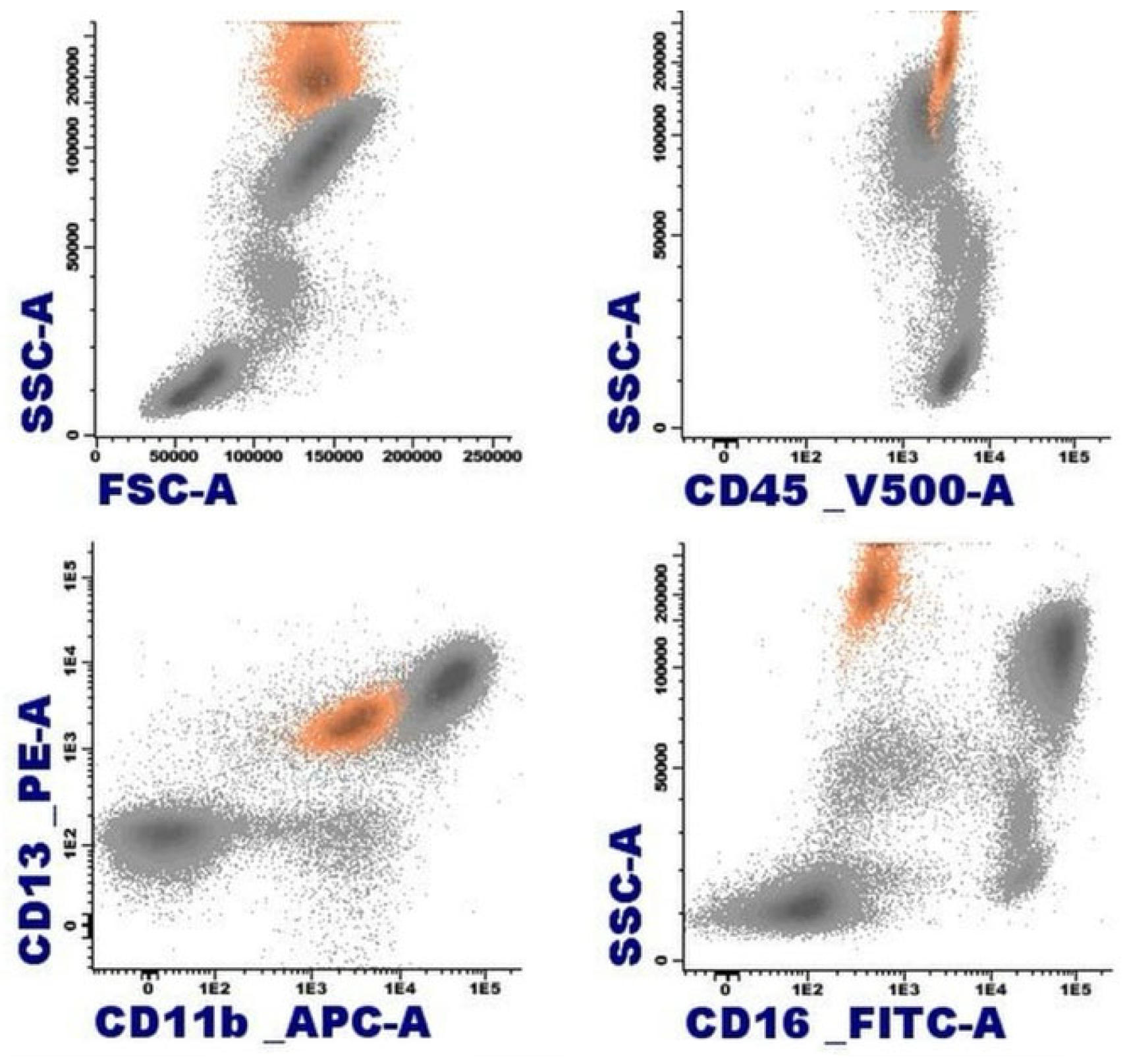

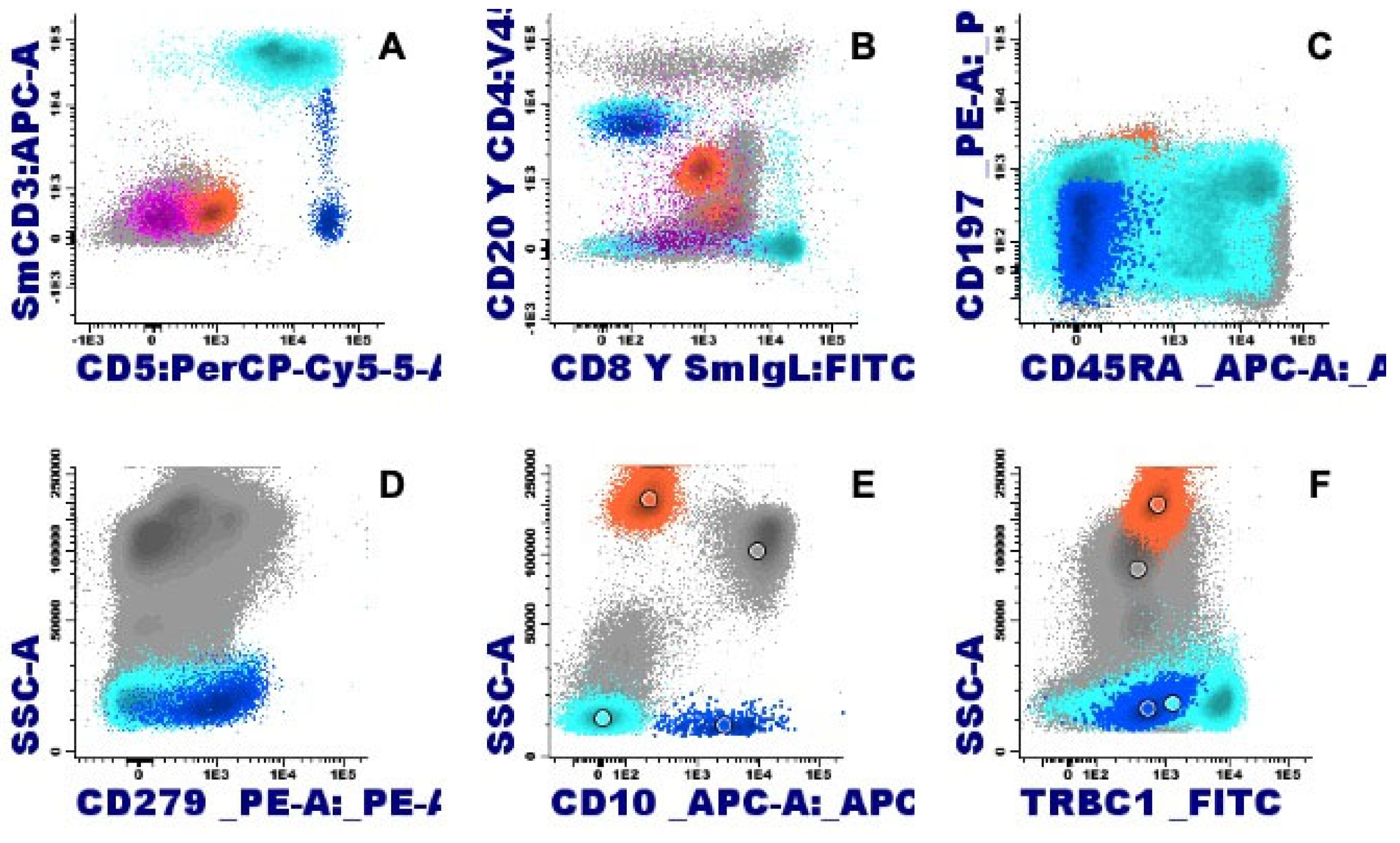

1.4. Flow cytometry of the eosinophil

2. Eosinophilia

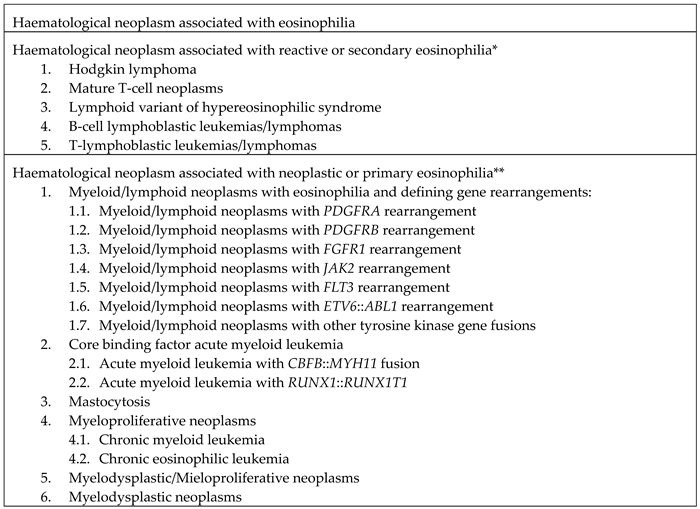

3. Hematological neoplasms associated with eosinophilia

3.1. Hematological neoplasms associated with reactive eosinophilia

3.1.1. Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma

3.1.2. Mature T-cell neoplasms

3.1.3. Lymphocyte variant hypereosinophilic syndrome

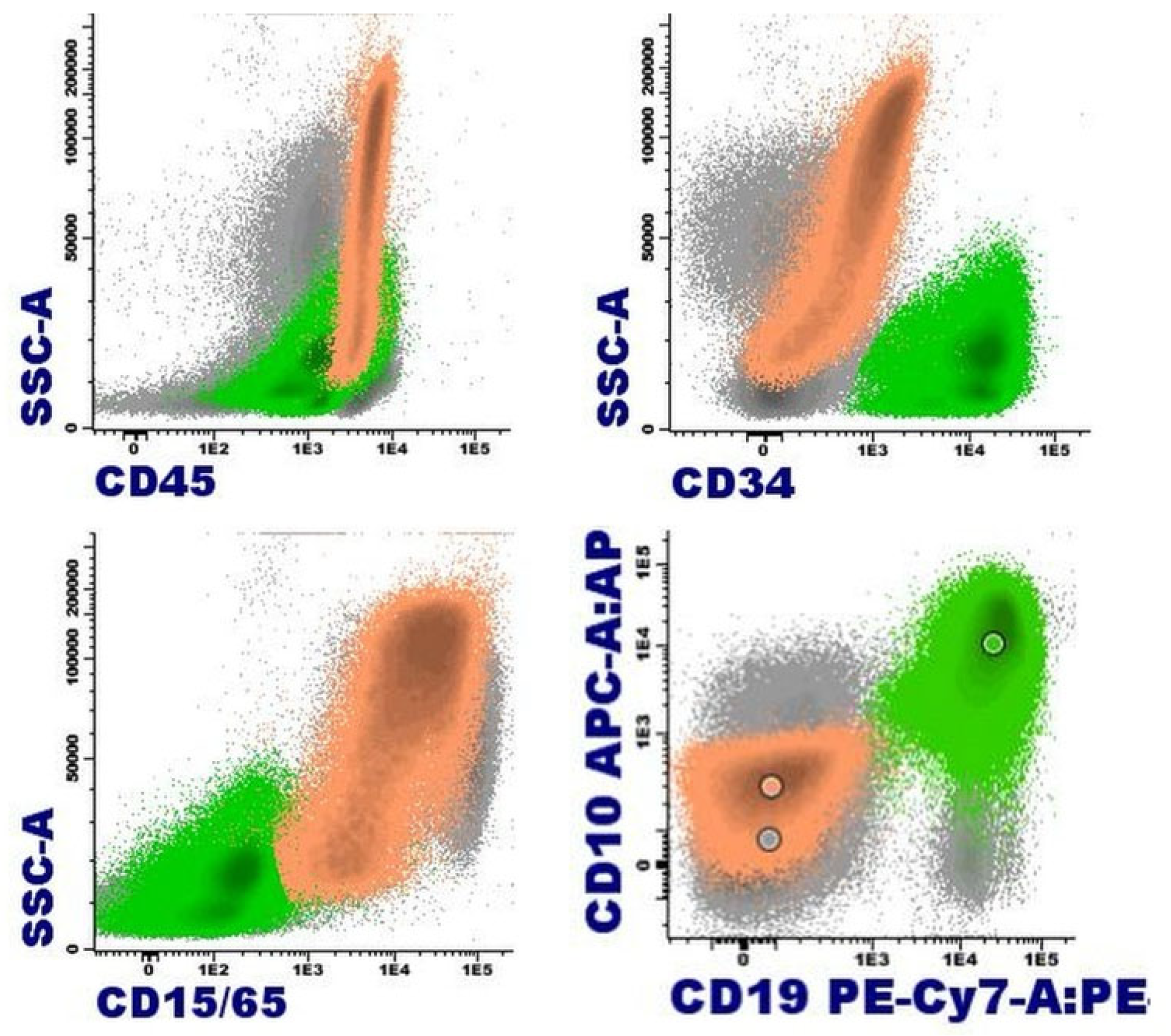

3.1.4. B Acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma

3.1.5. T acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma

3.2. Hematological malignancies associated with neoplastic or primary eosinophilia

3.2.1. Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and defining gene rearrangement

3.2.1.1. Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasm with PDGFRA rearrangement

3.2.1.2. Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasm with PDGFRB rearrangement

3.2.1.3. Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasm with FGFR1 rearrangement

3.2.1.4. Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasm with PCM1::JAK2 rearrangement

3.2.1.5. Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and defining gene rearrangement: new entities

3.2.2. Core Binding Factor acute myeloid leukemias

3.2.2.1. LMA with inv (16)( p13.1q22) o t(16;16)(p13.1;q22); CBFB::MYH11

3.2.2.2. LMA with t(8; 21)( q22;q22.1); RUNX1::RUNX1T1

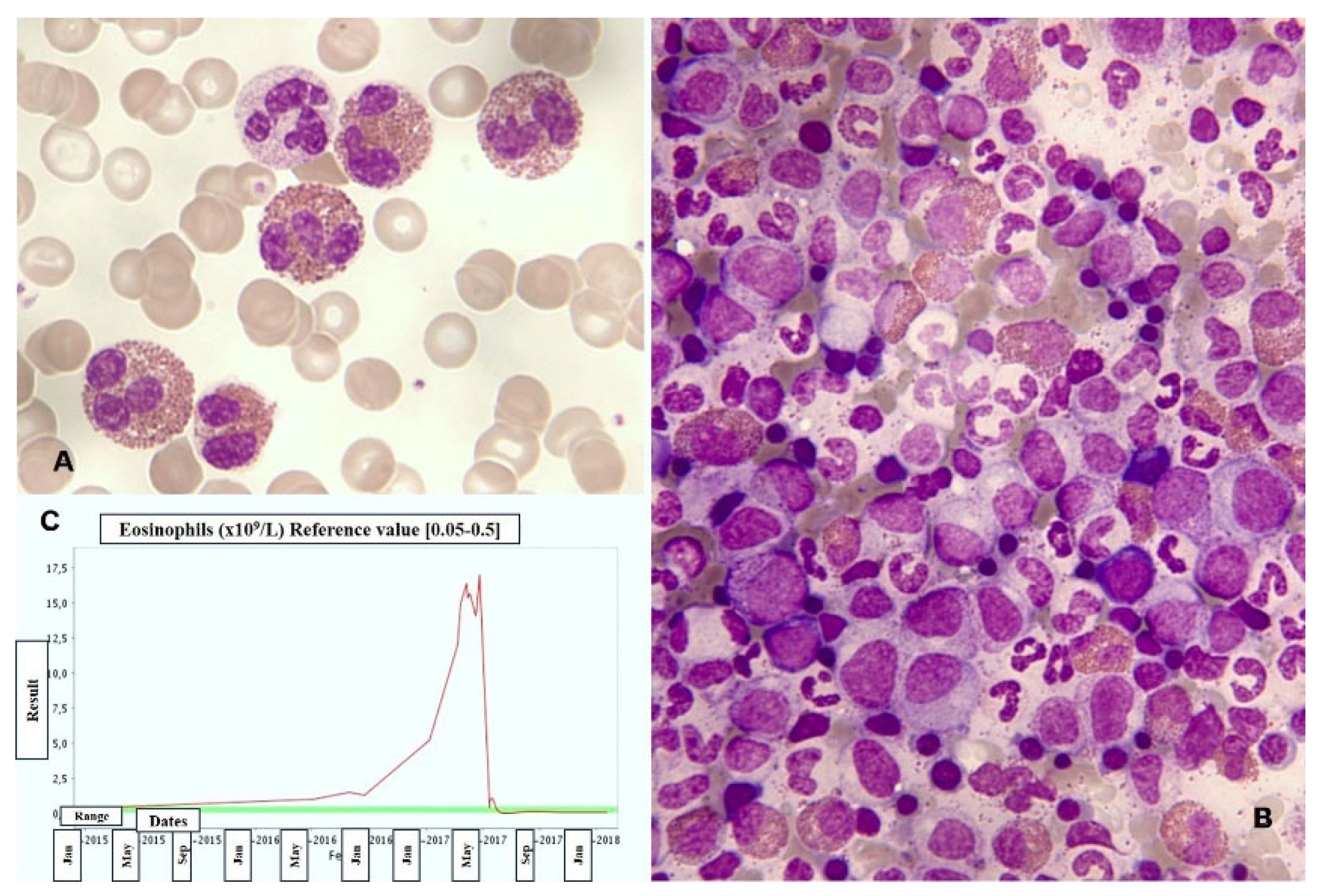

3.2.3. Mastocytosis

3.2.4. Myeloproliferative neoplasms

3.2.5. Chronic myeloid leukemia

3.2.6. Chronic eosinophilic leukemia

3.2.7. Myeloproliferative / myelodysplastic neoplasms

3.2.8. Myelodysplastic neoplasms

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ehrlich, P. (1879). Uber die spezifischen Granulationen des Blutes. Arch Anat Physiol., 571-579.

- Kay AB. The early history of the eosinophil. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015 Mar;45(3):575-82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woessner Casas S, Florensa Brich L. La citología óptica en el diagnóstico hematológico. 5ª. Ed. Madrid: Acción Médica S. A.; 2006.

- Johnston LK, Bryce PJ. Understanding Interleukin 33 and Its Roles in Eosinophil. Development. Front Med (Lausanne). 2017 May 2;4:51. [CrossRef]

- Varricchi G, Galdiero MR, Loffredo S, Lucarini V, Marone G, Mattei F, Marone G, Schiavoni G. Eosinophils: The unsung heroes in cancer? Oncoimmunology. 2017 Nov 13;7(2):e1393134. [CrossRef]

- DiScipio RG, Schraufstatter IU. The role of the complement anaphylatoxins in the recruitment of eosinophils. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007 Dec 20;7(14):1909-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo RCN, Weller PF. Contemporary understanding of the secretory granules in human eosinophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2018 Jul;104(1):85-93. [CrossRef]

- Acharya KR, Ackerman SJ. Eosinophil granule proteins: form and function. J Biol Chem. 2014 Jun 20;289(25):17406-15. [CrossRef]

- Kanda A, Yasutaka Y, Van Bui D, Suzuki K, Sawada S, Kobayashi Y, Asako M, Iwai H. Multiple Biological Aspects of Eosinophils in Host Defense, Eosinophil-Associated Diseases, Immunoregulation, and Homeostasis: Is Their Role Beneficial, Detrimental, Regulator, or Bystander? Biol Pharm Bull. 2020;43(1):20-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goasguen JE, Bennett JM, Bain BJ, Brunning R, Zini G, Vallespi MT, Tomonaga M, Locher C; International Working Group on Morphology of MDS. The role of eosinophil morphology in distinguishing between reactive eosinophilia and eosinophilia as a feature of a myeloid neoplasm. Br J Haematol. 2020 Nov;191(3):497-504. [CrossRef]

- Zederbauer M, Furtmüller PG, Brogioni S, Jakopitsch C, Smulevich G, Obinger C. Heme to protein linkages in mammalian peroxidases: impact on spectroscopic, redox and catalytic properties. Nat Prod Rep. 2007 Jun;24(3):571-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orfao A, Matarraz S, Pérez-Andrés M, et al. Immunophenotypic dissection of normal hematopoiesis. J Immunol Methods. 2019;475:112684. [CrossRef]

- Bain, BJ. Eosinophilic leukaemias and the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Br J Haematol. 1996 Oct;95(1):2-9. [PubMed]

- Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, Roufosse F, Gotlib J, Weller PF, Hellmann A, Metzgeroth G, Leiferman KM, Arock M, Butterfield JH, Sperr WR, Sotlar K, Vandenberghe P, Haferlach T, Simon HU, Reiter A, Gleich GJ. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Sep;130(3):607-612.e9. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Serrano J, Morales-Camacho RM, Caballero-Velázquez T, García-Canale S, Vargas MT, Prats-Martín C. Eosinophils engulfing platelets and with ring-shaped nuclei in nivolumab-associated eosinophilia. Br J Haematol. 2020 Mar;188(6):812. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Camacho RM, Prats-Martín C. Eosinophils with ring-shaped nuclei in a patient treated with adalimumab. Blood. 2019 Jan 3;133(1):101. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valent P, Degenfeld-Schonburg L, Sadovnik I, Horny HP, Arock M, Simon HU, Reiter A, Bochner BS. Eosinophils and eosinophil-associated disorders: immunological, clinical, and molecular complexity. Semin Immunopathol. 2021 Jun;43(3):423-438. [CrossRef]

- Roufosse F, Garaud S, de Leval L. Lymphoproliferative disorders associated with hypereosinophilia. Semin Hematol. 2012 Apr;49(2):138-48. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samoszuk M, Nansen L. Detection of interleukin-5 messenger RNA in Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin's disease with eosinophilia. Blood. 1990 Jan 1;75(1):13-6. [PubMed]

- Muñoz-García N, Lima M, Villamor N, Morán-Plata FJ, Barrena S, Mateos S, Caldas C, Balanzategui A, Alcoceba M, Domínguez A, Gómez F, Langerak AW, van Dongen JJM, Orfao A, Almeida J. Anti-TRBC1 Antibody-Based Flow Cytometric Detection of T-Cell Clonality: Standardization of Sample Preparation and Diagnostic Implementation. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Aug 30;13(17):4379. [CrossRef]

- Tancrède-Bohin E, Ionescu MA, de La Salmonière P, Dupuy A, Rivet J, Rybojad M, Dubertret L, Bachelez H, Lebbé C, Morel P. Prognostic value of blood eosinophilia in primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Arch Dermatol. 2004 Sep;140(9):1057-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulitzer MP, Horna P, Almeida J. Sézary syndrome and mycosis fungoides: An overview, including the role of immunophenotyping. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2021 Mar;100(2):132-138. [CrossRef]

- Pu Q, Qiao J, Liu Y, Cao X, Tan R, Yan D, Wang X, Li J, Yue B. Differential diagnosis and identification of prognostic markers for peripheral T-cell lymphoma subtypes based on flow cytometry immunophenotype profiles. Front Immunol. 2022 Nov 18;13:1008695. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki T, Karube K, Sakihama S, Tsuruta Y, Awazawa R, Hayashi M, Nakada N, Matsumoto H, Yagi N, Ohshiro K, Nakazato I, Kitamura S, Nishi Y, Miyagi T, Yamaguchi S, Nakachi S, Morishima S, Masuzaki H, Takahashi K, Fukushima T, Wada N. A Comprehensive Study of the Immunophenotype and its Clinicopathologic Significance in Adult T-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2023 Aug;36(8):100169. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi Y, Wang C. What we have learned about lymphocytic variant hypereosinophilic syndrome: A systematic literature review. Clin Immunol. 2022 Apr;237:108982. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier B, Balducci E, Duployez N, Clappier E, Cuccuini W, Arfeuille C, Caye-Eude A, Delabesse E, Bottollier-Lemallaz Colomb E, Nebral K, Chrétien ML, Derrieux C, Cabannes-Hamy A, Dumezy F, Etancelin P, Fenneteau O, Frayfer J, Gourmel A, Loosveld M, Michel G, Nadal N, Penther D, Tigaud I, Fournier E, Reismüller B, Attarbaschi A, Lafage-Pochitaloff M, Baruchel A. B-ALL With t(5;14)(q31;q32); IGH-IL3 Rearrangement and Eosinophilia: A Comprehensive Analysis of a Peculiar IGH-Rearranged B-ALL. Front Oncol. 2019 Dec 10;9:1374. [CrossRef]

- McClure BJ, Heatley SL, Rehn J, Breen J, Sutton R, Hughes TP, Suppiah R, Revesz T, Osborn M, White D, Yeung DT, White DL. High-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia presenting with hypereosinophilia and acquiring a novel PAX5 fusion on relapse. Br J Haematol. 2020 Oct;191(2):301-304. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon A, Fuda F, Gagan J, John S, Aquino V, Chen W. Rare circulating lymphoblasts with striking eosinophilia: A rare case of B-lymphoblastic leukemia with PAX5::ZCCHC7. Am J Hematol. 2023 Jun;98(6):989-990. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferruzzi V, Santi E, Gurdo G, Arcioni F, Caniglia M, Esposito S. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia with Hypereosinophilia in a Child: Case Report and Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Jun 4;15(6):1169. [CrossRef]

- Pierini V, Bardelli V, Giglio F, Arniani S, Matteucci C, Pellanera F, Quintini M, Crescenzi B, Bruno A, Sabattini E, Falcinelli E, Ruggeri L, Ronchi P, Ponzoni M, Ciceri F, Mecucci C, La Starza R. A Novel t(5;7)(q31;q21)/CDK6::IL3 in Immature T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia With IL3 Expression and Eosinophilia. Hemasphere. 2022 Oct 19;6(11):e795. [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J (Eds): WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues (Revised 4th edition). IARC: Lyon 2017.

- Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, Akkari Y, Alaggio R, Apperley JF, Bejar R, Berti E, Busque L, Chan JKC, Chen W, Chen X, Chng WJ, Choi JK, Colmenero I, Coupland SE, Cross NCP, De Jong D, Elghetany MT, Takahashi E, Emile JF, Ferry J, Fogelstrand L, Fontenay M, Germing U, Gujral S, Haferlach T, Harrison C, Hodge JC, Hu S, Jansen JH, Kanagal-Shamanna R, Kantarjian HM, Kratz CP, Li XQ, Lim MS, Loeb K, Loghavi S, Marcogliese A, Meshinchi S, Michaels P, Naresh KN, Natkunam Y, Nejati R, Ott G, Padron E, Patel KP, Patkar N, Picarsic J, Platzbecker U, Roberts I, Schuh A, Sewell W, Siebert R, Tembhare P, Tyner J, Verstovsek S, Wang W, Wood B, Xiao W, Yeung C, Hochhaus A. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022 Jul;36(7):1703-1719. [CrossRef]

- Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, Borowitz MJ, Calvo KR, Kvasnicka HM, Wang SA, Bagg A, Barbui T, Branford S, Bueso-Ramos CE, Cortes JE, Dal Cin P, DiNardo CD, Dombret H, Duncavage EJ, Ebert BL, Estey EH, Facchetti F, Foucar K, Gangat N, Gianelli U, Godley LA, Gökbuget N, Gotlib J, Hellström-Lindberg E, Hobbs GS, Hoffman R, Jabbour EJ, Kiladjian JJ, Larson RA, Le Beau MM, Loh ML, Löwenberg B, Macintyre E, Malcovati L, Mullighan CG, Niemeyer C, Odenike OM, Ogawa S, Orfao A, Papaemmanuil E, Passamonti F, Porkka K, Pui CH, Radich JP, Reiter A, Rozman M, Rudelius M, Savona MR, Schiffer CA, Schmitt-Graeff A, Shimamura A, Sierra J, Stock WA, Stone RM, Tallman MS, Thiele J, Tien HF, Tzankov A, Vannucchi AM, Vyas P, Wei AH, Weinberg OK, Wierzbowska A, Cazzola M, Döhner H, Tefferi A. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood. 2022 Sep 15;140(11):1200-1228. [CrossRef]

- Kim AS, Pozdnyakova O. SOHO State of the Art Updates and Next Questions | Myeloid/Lymphoid Neoplasms with Eosinophilia and Gene Rearrangements: Diagnostic Pearls and Pitfalls. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022 Sep;22(9):643-651. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozdnyakova O, Orazi A, Kelemen K, King R, Reichard KK, Craig FE, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Rimsza L, George TI, Horny HP, Wang SA. Myeloid/Lymphoid Neoplasms Associated With Eosinophilia and Rearrangements of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1 or With PCM1-JAK2. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021 Feb 4;155(2):160-178. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzgeroth G, Steiner L, Naumann N, Lübke J, Kreil S, Fabarius A, Haferlach C, Haferlach T, Hofmann WK, Cross NCP, Schwaab J, Reiter A. Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and tyrosine kinase gene fusions: reevaluation of the defining characteristics in a registry-based cohort. Leukemia. 2023 Sep;37(9):1860-1867. [CrossRef]

- Saft L, Kvasnicka HM, Boudova L, Gianelli U, Lazzi S, Rozman M. Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and tyrosine kinase fusion genes: A workshop report with focus on novel entities and a literature review including paediatric cases. Histopathology. 2023 Dec;83(6):829-849. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shomali W, Gotlib J. World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2022 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2022 Jan 1;97(1):129-148. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohmer J, Couteau-Chardon A, Trichereau J, Panel K, Gesquiere C, Ben Abdelali R, Bidet A, Bladé JS, Cayuela JM, Cony-Makhoul P, Cottin V, Delabesse E, Ebbo M, Fain O, Flandrin P, Galicier L, Godon C, Grardel N, Guffroy A, Hamidou M, Hunault M, Lengline E, Lhomme F, Lhermitte L, Machelart I, Mauvieux L, Mohr C, Mozicconacci MJ, Naguib D, Nicolini FE, Rey J, Rousselot P, Tavitian S, Terriou L, Lefèvre G, Preudhomme C, Kahn JE, Groh M; CEREO and GBMHM collaborators. Epidemiology, clinical picture and long-term outcomes of FIP1L1-PDGFRA-positive myeloid neoplasm with eosinophilia: Data from 151 patients. Am J Hematol. 2020 Nov;95(11):1314-1323. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Score J, Curtis C, Waghorn K, Stalder M, Jotterand M, Grand FH, Cross NC. Identification of a novel imatinib responsive KIF5B-PDGFRA fusion gene following screening for PDGFRA overexpression in patients with hypereosinophilia. Leukemia. 2006 May;20(5):827-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walz C, Curtis C, Schnittger S, Schultheis B, Metzgeroth G, Schoch C, Lengfelder E, Erben P, Müller MC, Haferlach T, Hochhaus A, Hehlmann R, Cross NC, Reiter A. Transient response to imatinib in a chronic eosinophilic leukemia associated with ins(9;4)(q33;q12q25) and a CDK5RAP2-PDGFRA fusion gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006 Oct;45(10):950-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis CE, Grand FH, Musto P, Clark A, Murphy J, Perla G, Minervini MM, Stewart J, Reiter A, Cross NC. Two novel imatinib-responsive PDGFRA fusion genes in chronic eosinophilic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2007 Jul;138(1):77-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter EJ, Hochhaus A, Bolufer P, Reiter A, Fernandez JM, Senent L, Cervera J, Moscardo F, Sanz MA, Cross NC. The t(4;22)(q12;q11) in atypical chronic myeloid leukaemia fuses BCR to PDGFRA. Hum Mol Genet. 2002 Jun 1;11(12):1391-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers ZR, Ali SM, Ohgami RS, Campregher PV, Frampton GM, Yelensky R, Elvin JA, Palma NA, Erlich R, Vergilio JA, Chmielecki J, Ross JS, Stephens PJ, Hermann R, Miller VA, Miles CR. Comprehensive genomic profiling identifies a novel TNKS2-PDGFRA fusion that defines a myeloid neoplasm with eosinophilia that responded dramatically to imatinib therapy. Blood Cancer J. 2015 Feb 6;5(2):e278. [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto Y, Sada A, Shimokariya Y, Monma F, Ohishi K, Masuya M, Nobori T, Matsui T, Katayama N. A novel FOXP1-PDGFRA fusion gene in myeloproliferative neoplasm with eosinophilia. Cancer Genet. 2015 Oct;208(10):508-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain N, Khoury JD, Pemmaraju N, Kollipara P, Kantarjian H, Verstovsek S. Imatinib therapy in a patient with suspected chronic neutrophilic leukemia and FIP1L1-PDGFRA rearrangement. Blood. 2013 Nov 7;122(19):3387-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiely R, Almasri F, Almasri N, Abu-Ghosh A. Case Report: Pediatric myeloid/lymphoid neoplasm with eosinophilia and PDGFRA rearrangement: The first case presenting as B-lymphoblastic lymphoma. Front Pediatr. 2022 Dec 14;10:1059527. [CrossRef]

- Huang Q, Snyder DS, Chu P, Gaal KK, Chang KL, Weiss LM. PDGFRA rearrangement leading to hyper-eosinophilia, T-lymphoblastic lymphoma, myeloproliferative neoplasm and precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2011 Feb;25(2):371-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trempat P, Villalva C, Laurent G, Armstrong F, Delsol G, Dastugue N, Brousset P. Chronic myeloproliferative disorders with rearrangement of the platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor: a new clinical target for STI571/Glivec. Oncogene. 2003 Aug 28;22(36):5702-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts KG, Gu Z, Payne-Turner D, McCastlain K, Harvey RC, Chen IM, Pei D, Iacobucci I, Valentine M, Pounds SB, Shi L, Li Y, Zhang J, Cheng C, Rambaldi A, Tosi M, Spinelli O, Radich JP, Minden MD, Rowe JM, Luger S, Litzow MR, Tallman MS, Wiernik PH, Bhatia R, Aldoss I, Kohlschmidt J, Mrózek K, Marcucci G, Bloomfield CD, Stock W, Kornblau S, Kantarjian HM, Konopleva M, Paietta E, Willman CL, Mullighan CG. High Frequency and Poor Outcome of Philadelphia Chromosome-Like Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Adults. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Feb;35(4):394-401. [CrossRef]

- Krigstein M, Menzies A, Fay K, Lukeis R, Cheung K, Parker A. FIP1L1::PDGFRA fusion driving three synchronous haematological malignancies. Pathology. 2023 Dec;55(7):1040-1044. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellani V, Croci GA, Bucelli C, Maronese CA, Alberti S, Iurlo A, Cattaneo D. Lymphomatoid papulosis associated with myeloid neoplasm with eosinophilia and FIP1L1::PDGFRA rearrangement: Successful imatinib treatment in two cases. J Dermatol. 2023 Oct;50(10):1330-1334. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baccarani M, Cilloni D, Rondoni M, Ottaviani E, Messa F, Merante S, Tiribelli M, Buccisano F, Testoni N, Gottardi E, de Vivo A, Giugliano E, Iacobucci I, Paolini S, Soverini S, Rosti G, Rancati F, Astolfi C, Pane F, Saglio G, Martinelli G. The efficacy of imatinib mesylate in patients with FIP1L1-PDGFRalpha-positive hypereosinophilic syndrome. Results of a multicenter prospective study. Haematologica. 2007 Sep;92(9):1173-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawhar M, Naumann N, Schwaab J, Baurmann H, Casper J, Dang TA, Dietze L, Döhner K, Hänel A, Lathan B, Link H, Lotfi S, Maywald O, Mielke S, Müller L, Platzbecker U, Prümmer O, Thomssen H, Töpelt K, Panse J, Vieler T, Hofmann WK, Haferlach T, Haferlach C, Fabarius A, Hochhaus A, Cross NCP, Reiter A, Metzgeroth G. Imatinib in myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and rearrangement of PDGFRB in chronic or blast phase. Ann Hematol. 2017 Sep;96(9):1463-1470. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darbyshire PJ, Shortland D, Swansbury GJ, Sadler J, Lawler SD, Chessells JM. A myeloproliferative disease in two infants associated with eosinophilia and chromosome t(1;5) translocation. Br J Haematol. 1987 Aug;66(4):483-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson K, Velloso ER, Lopes LF, Lee C, Aster JC, Shipp MA, Aguiar RC. Cloning of the t(1;5)(q23;q33) in a myeloproliferative disorder associated with eosinophilia: involvement of PDGFRB and response to imatinib. Blood. 2003 Dec 1;102(12):4187-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Z, Yang R, Zhao J, Yuan R, Lu Q, Li Q, Tse W. Molecular diagnosis and targeted therapy of a pediatric chronic eosinophilic leukemia patient carrying TPM3-PDGFRB fusion. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011 Mar;56(3):463-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham S, Salama M, Hancock J, Jacobsen J, Fluchel M. Congenital and childhood myeloproliferative disorders with eosinophilia responsive to imatinib. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012 Nov;59(5):928-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berking AC, Flaadt T, Behrens YL, Yoshimi A, Leipold A, Holzer U, Lang P, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Schlegelberger B, Reiter A, Niemeyer C, Strahm B, Göhring G. Rare and potentially fatal - Cytogenetically cryptic TNIP1::PDGFRB and PCM1::FGFR1 fusion leading to myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia in children. Cancer Genet. 2023 Apr;272-273:29-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang SC, Yang WY. Myeloid neoplasm with eosinophilia and rearrangement of platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta gene in children: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases. 2021 Jan 6;9(1):204-210. [CrossRef]

- McKeague SJ, O'Rourke K, Fanning S, Joy C, Throp D, Adams R, Harvey Y, Keng TB. Acute leukemia with cytogenetically cryptic FGFR1 rearrangement and lineage switch during therapy: A case report and literature review. Am J Clin Pathol. 2023 Oct 19:aqad135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strati P, Tang G, Duose DY, Mallampati S, Luthra R, Patel KP, Hussaini M, Mirza AS, Komrokji RS, Oh S, Mascarenhas J, Najfeld V, Subbiah V, Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G, Verstovsek S, Daver N. Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with FGFR1 rearrangement. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018 Jul;59(7):1672-1676. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Boluda JC, Pereira A, Zinger N, Gras L, Martino R, Nikolousis E, Finke J, Chinea A, Rambaldi A, Robin M, Saccardi R, Natale A, Snowden JA, Tsirigotis P, Vallejo C, Wulf G, Xicoy B, Russo D, Maertens J, Daguindau E, Lenhoff S, Hayden P, Czerw T, McLornan DP, Yakoub-Agha I. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with myeloid/lymphoid neoplasm with FGFR1-rearrangement: a study of the Chronic Malignancies Working Party of EBMT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2022 Mar;57(3):416-422. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakim JJ, Tirado CA, Chen W, Collins R. t(8;22)/BCR-FGFR1 myeloproliferative disorder presenting as B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia: report of a case treated with sorafenib and review of the literature. Leuk Res. 2011 Sep;35(9):e151-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam K, Langabeer SE, Kelly J, Coen N, O'Connell NM, Conneally E. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for a BCR-FGFR1 Myeloproliferative Neoplasm Presenting as Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Case Rep Hematol. 2012;2012:620967. [CrossRef]

- Baldazzi C, Iacobucci I, Luatti S, Ottaviani E, Marzocchi G, Paolini S, Stacchini M, Papayannidis C, Gamberini C, Martinelli G, Baccarani M, Testoni N. B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia as evolution of a 8p11 myeloproliferative syndrome with t(8;22)(p11;q11) and BCR-FGFR1 fusion gene. Leuk Res. 2010 Oct;34(10):e282-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth CB, Zhang L, Li S. Systemic mastocytosis with associated myeloproliferative neoplasm with t(8;19)(p12;q13.1) and abnormality of FGFR1: report of a unique case. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014 Jan 15;7(2):801-7.

- Macdonald D, Aguiar RC, Mason PJ, Goldman JM, Cross NC. A new myeloproliferative disorder associated with chromosomal translocations involving 8p11: a review. Leukemia. 1995 Oct;9(10):1628-30. [PubMed]

- Macdonald D, Reiter A, Cross NC. The 8p11 myeloproliferative syndrome: a distinct clinical entity caused by constitutive activation of FGFR1. Acta Haematol. 2002;107(2):101-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama H, Inamitsu T, Ohga S, Kai T, Suda M, Matsuzaki A, Ueda K. Chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia with t(8;9)(p11;q34) in childhood: an example of the 8p11 myeloproliferative disorder? Br J Haematol. 1996 Mar;92(3):692-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg H, Kroes W, van der Schoot CE, Dee R, Pals ST, Bouts TH, Slater RM. A young child with acquired t(8;9)(p11;q34): additional proof that 8p11 is involved in mixed myeloid/T lymphoid malignancies. Leukemia. 1996 Jul;10(7):1252-3. [PubMed]

- Wong WS, Cheng KC, Lau KM, Chan NP, Shing MM, Cheng SH, Chik KW, Li CK, Ng MH. Clonal evolution of 8p11 stem cell syndrome in a 14-year-old Chinese boy: a review of literature of t(8;13) associated myeloproliferative diseases. Leuk Res. 2007 Feb;31(2):235-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang WW, Habeebu S, Sheehan AM, Naeem R, Hernandez VS, Dreyer ZE, López-Terrada D. Molecular monitoring of 8p11 myeloproliferative syndrome in an infant. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009 Nov;31(11):879-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan Y, Qu S, Liu J, Li C, Yan X, Xu Z, Qin T, Jia Y, Pan L, Gao Q, Jiao M, Li B, Gale RP, Xiao Z. Olverembatinib for myeloid/lymphoid neoplasm associated with eosinophilia and FGFR1 rearrangement. Leuk Lymphoma. 2023 Sep;64(9):1605-1610. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzankov A, Reichard KK, Hasserjian RP, Arber DA, Orazi A, Wang SA. Updates on eosinophilic disorders. Virchows Arch. 2023 Jan;482(1):85-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan HG, Jin R, Bifulco CB, Scanlan JM, Corwin DR. PCM1-JAK2 Fusion Tyrosine Kinase Gene-Related Neoplasia: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Literature. Oncologist. 2022 Aug 5;27(8):e661-e670. [CrossRef]

- Rumi E, Milosevic JD, Casetti I, Dambruoso I, Pietra D, Boveri E, Boni M, Bernasconi P, Passamonti F, Kralovics R, Cazzola M. Efficacy of ruxolitinib in chronic eosinophilic leukemia associated with a PCM1-JAK2 fusion gene. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jun 10;31(17):e269-71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang G, Tam W, Short NJ, Bose P, Wu D, Hurwitz SN, Bagg A, Rogers HJ, Hsi ED, Quesada AE, Wang W, Miranda RN, Bueso-Ramos CE, Medeiros LJ, Nardi V, Hasserjian RP, Arber DA, Orazi A, Foucar K, Wang SA. Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with FLT3 rearrangement. Mod Pathol. 2021 Sep;34(9):1673-1685. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venable ER, Gagnon MF, Pitel BA, Palmer JM, Peterson JF, Baughn LB, Hoppman NL, Greipp PT, Ketterling RP, Patnaik MS, Kelemen K, Xu X. A TRIP11:: FLT3 gene fusion in a patient with myeloid/lymphoid neoplasm with eosinophilia and tyrosine kinase gene fusions: a case report and review of the literature. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2023 Mar 24;9(1):a006243. [CrossRef]

- Schoelinck J, Gervasoni J, Guillermin Y, Beillard E, Pissaloux D, Chassagne-Clement C. T cell phenotype and lack of eosinophilia are not uncommon in extramedullary myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with ETV6::FLT3 fusion: a case report and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2023 Nov 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer B, Dela Cruz FS, Ibanez Sanchez GD, Zhang Y, Xiao W, Benayed R, Markova A, Rodriguez-Sanchez MI, Bouvier N, Roshal M, Kung AL, Shukla N. ETV6-FLT3-positive myeloid/lymphoid neoplasm with eosinophilia presenting in an infant: an entity distinct from JMML. Blood Adv. 2021 Apr 13;5(7):1899-1902. [CrossRef]

- Munthe-Kaas MC, Forthun RB, Brendehaug A, Eek AK, Høysæter T, Osnes LTN, Prescott T, Spetalen S, Hovland R. Partial Response to Sorafenib in a Child With a Myeloid/Lymphoid Neoplasm, Eosinophilia, and a ZMYM2-FLT3 Fusion. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2021 May 1;43(4):e508-e511. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasian SK, Loh ML, Hunger SP. Philadelphia chromosome-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2017 Nov 9;130(19):2064-2072. [CrossRef]

- De Braekeleer E, Douet-Guilbert N, Rowe D, Bown N, Morel F, Berthou C, Férec C, De Braekeleer M. ABL1 fusion genes in hematological malignancies: a review. Eur J Haematol. 2011 May;86(5):361-71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaliova M, Moorman AV, Cazzaniga G, Stanulla M, Harvey RC, Roberts KG, Heatley SL, Loh ML, Konopleva M, Chen IM, Zimmermannova O, Schwab C, Smith O, Mozziconacci MJ, Chabannon C, Kim M, Frederik Falkenburg JH, Norton A, Marshall K, Haas OA, Starkova J, Stuchly J, Hunger SP, White D, Mullighan CG, Willman CL, Stary J, Trka J, Zuna J. Characterization of leukemias with ETV6-ABL1 fusion. Haematologica. 2016 Sep;101(9):1082-93. [CrossRef]

- Carll T, Patel A, Derman B, Hyjek E, Lager A, Wanjari P, Segal J, Odenike O, Fidai S, Arber D. Diagnosis and treatment of mixed phenotype (T-myeloid/lymphoid) acute leukemia with novel ETV6-FGFR2 rearrangement. Blood Adv. 2020 Oct 13;4(19):4924-4928. [CrossRef]

- Telford N, Alexander S, McGinn OJ, Williams M, Wood KM, Bloor A, Saha V. Myeloproliferative neoplasm with eosinophilia and T-lymphoblastic lymphoma with ETV6-LYN gene fusion. Blood Cancer J. 2016 Apr 8;6(4):e412. [CrossRef]

- Kralik JM, Kranewitter W, Boesmueller H, Marschon R, Tschurtschenthaler G, Rumpold H, Wiesinger K, Erdel M, Petzer AL, Webersinke G. Characterization of a newly identified ETV6-NTRK3 fusion transcript in acute myeloid leukemia. Diagn Pathol. 2011 Mar 15;6:19. [CrossRef]

- Maesako Y, Izumi K, Okamori S, Takeoka K, Kishimori C, Okumura A, Honjo G, Akasaka T, Ohno H. inv(2)(p23q13)/RAN-binding protein 2 (RANBP2)-ALK fusion gene in myeloid leukemia that developed in an elderly woman. Int J Hematol. 2014 Feb;99(2):202-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballerini P, Struski S, Cresson C, Prade N, Toujani S, Deswarte C, Dobbelstein S, Petit A, Lapillonne H, Gautier EF, Demur C, Lippert E, Pages P, Mansat-De Mas V, Donadieu J, Huguet F, Dastugue N, Broccardo C, Perot C, Delabesse E. RET fusion genes are associated with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and enhance monocytic differentiation. Leukemia. 2012 Nov;26(11):2384-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naymagon L, Marcellino B, Mascarenhas J. Eosinophilia in acute myeloid leukemia: Overlooked and underexamined. Blood Rev. 2019 Jul;36:23-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson RA, Williams SF, Le Beau MM, Bitter MA, Vardiman JW, Rowley JD. Acute myelomonocytic leukemia with abnormal eosinophils and inv(16) or t(16;16) has a favorable prognosis. Blood. 1986 Dec;68(6):1242-9. [PubMed]

- Ouyang J, Goswami M, Peng J, Zuo Z, Daver N, Borthakur G, Tang G, Medeiros LJ, Jorgensen JL, Ravandi F, Wang SA. Comparison of Multiparameter Flow Cytometry Immunophenotypic Analysis and Quantitative RT-PCR for the Detection of Minimal Residual Disease of Core Binding Factor Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016 Jun;145(6):769-77. [CrossRef]

- Raya José María, Gómez-Hernando Marta, Guijarro Francesca, Alonso Esther, Arnan Montserrat, Senent Leonor, Vicente Ana Isabel, Borrego Asunción, Gómez-Casares María Teresa, González-González Carmen, Ondarra Laida, Saumell Silvia, Montoro María Julia, Abío María de la O, Daza Sonia, Orna Elisa, Caballero María del Mar, Ródenas Isabel, Lo Riso Laura, De Miguel Carlos, Blanco Angela, Ricard María Pilar, Roldán Verónica, Martín-Santos Taida, Grupo Español de Citología Hematológica. (2021). PO-115: Leucemia aguda mieloide con t(8,21); RUNX1-RUNX1T1: análisis multicéntrico retrospectivo de 165 pacientes. LXIII Congreso Nacional de la SEHH XXXVII Congreso Nacional de la SETH Pamplona, 14-16 de octubre, 2021. Haematologica. Volume 106 OCTOBER 2021 - S2. ISSN 0390-6078.

- Swirsky DM, Li YS, Matthews JG, Flemans RJ, Rees JK, Hayhoe FG. 8;21 translocation in acute granulocytic leukaemia: cytological, cytochemical and clinical features. Br J Haematol. 1984 Feb;56(2):199-213. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haferlach T, Bennett JM, Löffler H, Gassmann W, Andersen JW, Tuzuner N, Casslleth PA, Fonatsch C, Schoch C, Schlegelberger B, Becher R, Thiel E, Ludwig WD, Sauerland MC, Heinecke A, Büchner T. Acute myeloid leukemia with translocation (8;21). Cytomorphology, dysplasia and prognostic factors in 41 cases. AML Cooperative Group and ECOG. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996 Oct;23(3-4):227-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valent P, Akin C, Hartmann K, Alvarez-Twose I, Brockow K, Hermine O, Niedoszytko M, Schwaab J, Lyons JJ, Carter MC, Elberink HO, Butterfield JH, George TI, Greiner G, Ustun C, Bonadonna P, Sotlar K, Nilsson G, Jawhar M, Siebenhaar F, Broesby-Olsen S, Yavuz S, Zanotti R, Lange M, Nedoszytko B, Hoermann G, Castells M, Radia DH, Muñoz-Gonzalez JI, Sperr WR, Triggiani M, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Galli SJ, Schwartz LB, Reiter A, Orfao A, Gotlib J, Arock M, Horny HP, Metcalfe DD. Updated Diagnostic Criteria and Classification of Mast Cell Disorders: A Consensus Proposal. Hemasphere. 2021 Oct 13;5(11):e646. [CrossRef]

- Kluin-Nelemans HC, Reiter A, Illerhaus A, van Anrooij B, Hartmann K, Span LFR, Gorska A, Niedoszytko M, Lange M, Scaffidi L, Zanotti R, Bonadonna P, Perkins C, Elena C, Malcovati L, Shoumariyeh K, von Bubnoff N, Parente R, Triggiani M, Schwaab J, Jawhar M, Caroppo F, Fortina AB, Brockow K, Zink A, Fuchs D, Kilbertus A, Yavuz AS, Doubek M, Mattsson M, Hagglund H, Panse J, Sabato V, Aberer E, Niederwieser D, Breynaert C, Várkonyi J, Kennedy V, Lortholary O, Jakob T, Hermine O, Rossignol J, Arock M, Gotlib J, Valent P, Sperr WR. Prognostic impact of eosinophils in mastocytosis: analysis of 2350 patients collected in the ECNM Registry. Leukemia. 2020 Apr;34(4):1090-1101. [CrossRef]

- Kovalszki A, Weller PF. Eosinophilia in mast cell disease. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014 May;34(2):357-64. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Camacho RM, Villanueva-Herraiz S, Prats-Martín C, Borrero JJ, Bernal R, Vargas MT. Eosinophil phagocytosis in advanced systemic mastocytosis with eosinophilia. Br J Haematol. 2018 Jun;181(5):578. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshref Razavi H, Yu R. Myeloid neoplasm with PDGFRB rearrangement, presenting as systemic mastocytosis-chronic eosinophilic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2022 May;97(5):668-669. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leguit RJ, Wang SA, George TI, Tzankov A, Orazi A. The international consensus classification of mastocytosis and related entities. Virchows Arch. 2023 Jan;482(1):99-112. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgado JM, Perbellini O, Johnson RC, Teodósio C, Matito A, Álvarez-Twose I, Bonadonna P, Zamò A, Jara-Acevedo M, Mayado A, Garcia-Montero A, Mollejo M, George TI, Zanotti R, Orfao A, Escribano L, Sánchez-Muñoz L. CD30 expression by bone marrow mast cells from different diagnostic variants of systemic mastocytosis. Histopathology. 2013 Dec;63(6):780-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langabeer SE. The eosinophilic variant of chronic myeloid leukemia. EXCLI J. 2021 Nov 26;20:1608-1609. [CrossRef]

- Morsia E, Reichard K, Pardanani A, Tefferi A, Gangat N. WHO defined chronic eosinophilic leukemia, not otherwise specified (CEL, NOS): A contemporary series from the Mayo Clinic. Am J Hematol. 2020 Jul;95(7):E172-E174. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushima T, Handa H, Yokohama A, Nagasaki J, Koiso H, Kin Y, Tanaka Y, Sakura T, Tsukamoto N, Karasawa M, Itoh K, Hirabayashi H, Sawamura M, Shinonome S, Shimano S, Miyawaki S, Nojima Y, Murakami H. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of myelodysplastic syndrome with bone marrow eosinophilia or basophilia. Blood. 2003 May 1;101(9):3386-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).