Submitted:

30 November 2023

Posted:

01 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

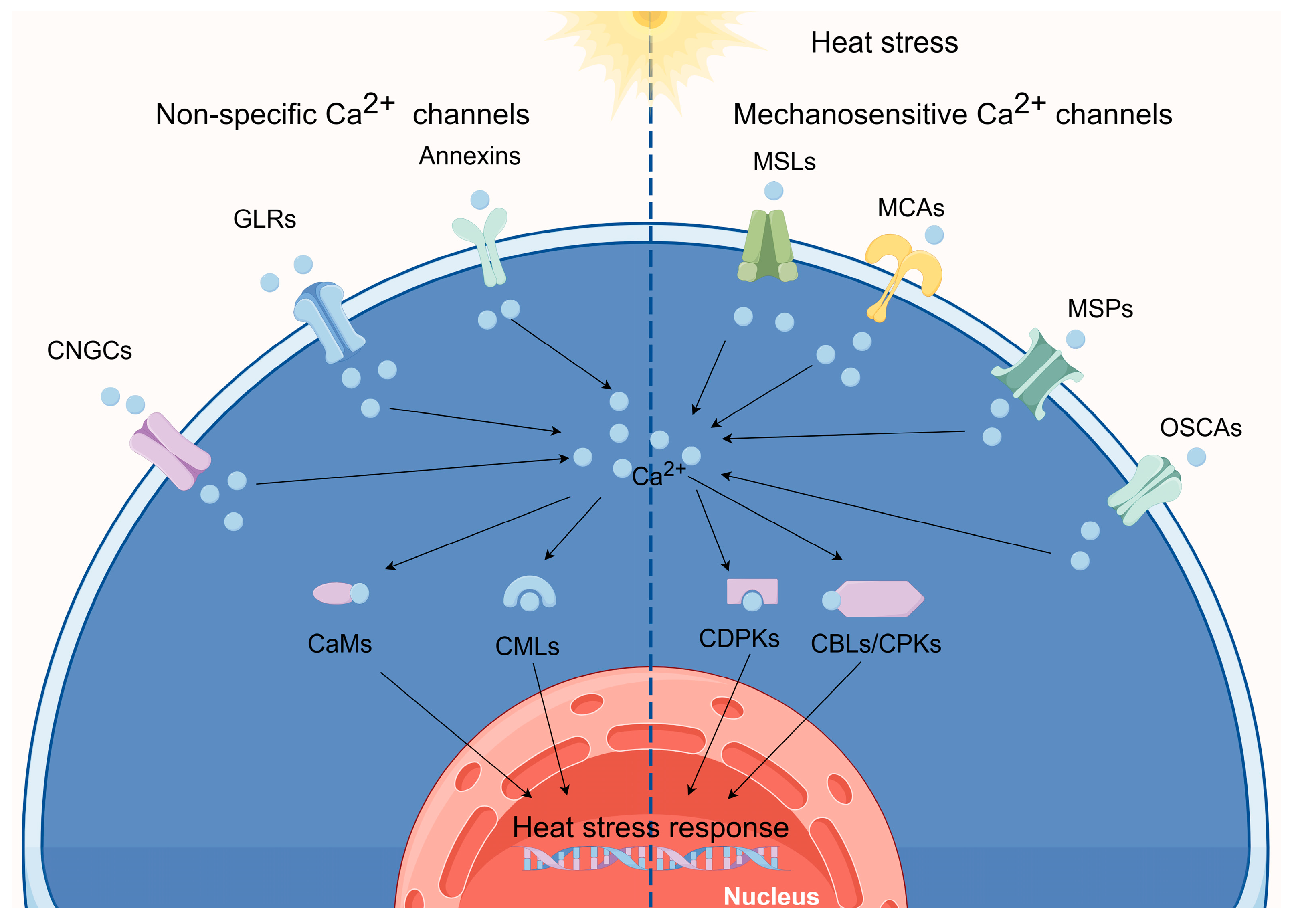

1. Ca2+ signaling and plant thermotolerance

2. Ca2+-permeable channels perceive elevated temperatures

2.1. Heat sensing via CNGCs

2.2. Heat sensing via GLRs

2.3. Heat sensing via annexins

2.4. Heat sensing via OSCAs

2.5. The functions of MSLs, MCAs, and MSPs in plants following HT treatment

| Gene type | Organism | Gene symbol | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNGCs | Physcomitrella patens | CNGCb | Sensitive to heat stress | [5] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AtCNGC2 | Sensitive to heat stress at the seedling stage; Tolerance to heat stress at the reproductive stage | [5,20,21] | |

| AtCNGC4 | Tolerance to extreme temperatures; Response to pathogen infection | [22] | ||

| AtCNGC6 | Regulates tolerance to extreme temperatures together with H2O2 and NO | [23,24,25] | ||

| Oryza sativa L. | OsCNGC14 | Tolerance to extreme temperatures | [26] | |

| OsCNGC16 | Tolerance to extreme temperatures | [26] | ||

| GLRs | Arabidopsis thaliana | AtGLR3.3 | Response to pathogen infection | [41] |

| Vicia faba L. | VfGLR3.5 | Tolerance to drought | [42 | |

| Zea mays L. | ZmGLR | Tolerance to heat stress | [44] | |

| Solanum lycopersicum L. | SlGLR3.3 | Tolerance to cold stress by regulating apoplastic H2O2 production and redox homeostasis | [43] | |

| SlGLR3.5 | Tolerance to cold stress by regulating apoplastic H2O2 production and redox homeostasis | [43] | ||

| ANNEXINs | Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. | NnANN1 | Tolerance to heat stress | [56] |

| Glycine max L. | GmANN | Tolerance to high temperatures and humidity stress | [57] | |

| Oryza sativa L. | OsANA1 | Tolerance to heat shock, H2O2 treatment, and abiotic stress | [58] | |

| Raphanus sativus L. | RsANN | Tolerance to heat, drought, salinity, oxidation, and ABA stress | [59] | |

| OSCAs | Zea mays L. | ZmOSCA1.4 | Gene expression increases in response to heat stress | [64] |

| ZmOSCA2.1 | Gene expression increases in response to heat stress | [64] | ||

| ZmOSCA2.2 | Gene expression increases in response to heat stress | [64] | ||

| ZmOSCA2.5 | Gene expression increases in response to heat stress | [64] | ||

| ZmOSCA3.1 | Gene expression increases in response to heat stress | [64] | ||

| ZmOSCA4.1 | Gene expression increases in response to heat stress | [64] | ||

| ZmOSCA1.3 | Gene expression decreases in response to heat stress | [64] | ||

| ZmOSCA1.5 | Gene expression decreases in response to heat stress | [64] | ||

| ZmOSCA2.4 | Gene expression decreases in response to heat stress | [64] | ||

| MSLs | Arabidopsis thaliana | AtMSL2 | Tolerance to high osmotic stress | [65] |

| AtMSL3 | Tolerance to high osmotic stress | [65] | ||

| AtMSL8 | Response to plasma membrane distortion during pollen grain rehydration and germination | [66] | ||

| AtMSL9 | Exhibits MS ion channel activity | [67] | ||

| AtMSL10 | Exhibits MS ion channel activity | [67] | ||

| Oryza sativa L. | OsMSLs | Responses to plant growth, development, and various stressors | [68] | |

| MCAs | Arabidopsis thaliana | AtMCA1 | Tolerance to cold stress | [72] |

| AtMCA2 | Tolerance to cold stress | [72] | ||

| MSPs | Arabidopsis thaliana | AtPiezo | Response to virus infection | [75] |

3. Ca2+-binding protein involvement in HS responses

3.1. CaMs in HS signaling

3.2. CMLs in HS signaling

3.3. CDPKs in HS signaling

3.4. CBLs and CIPKs in HS signaling

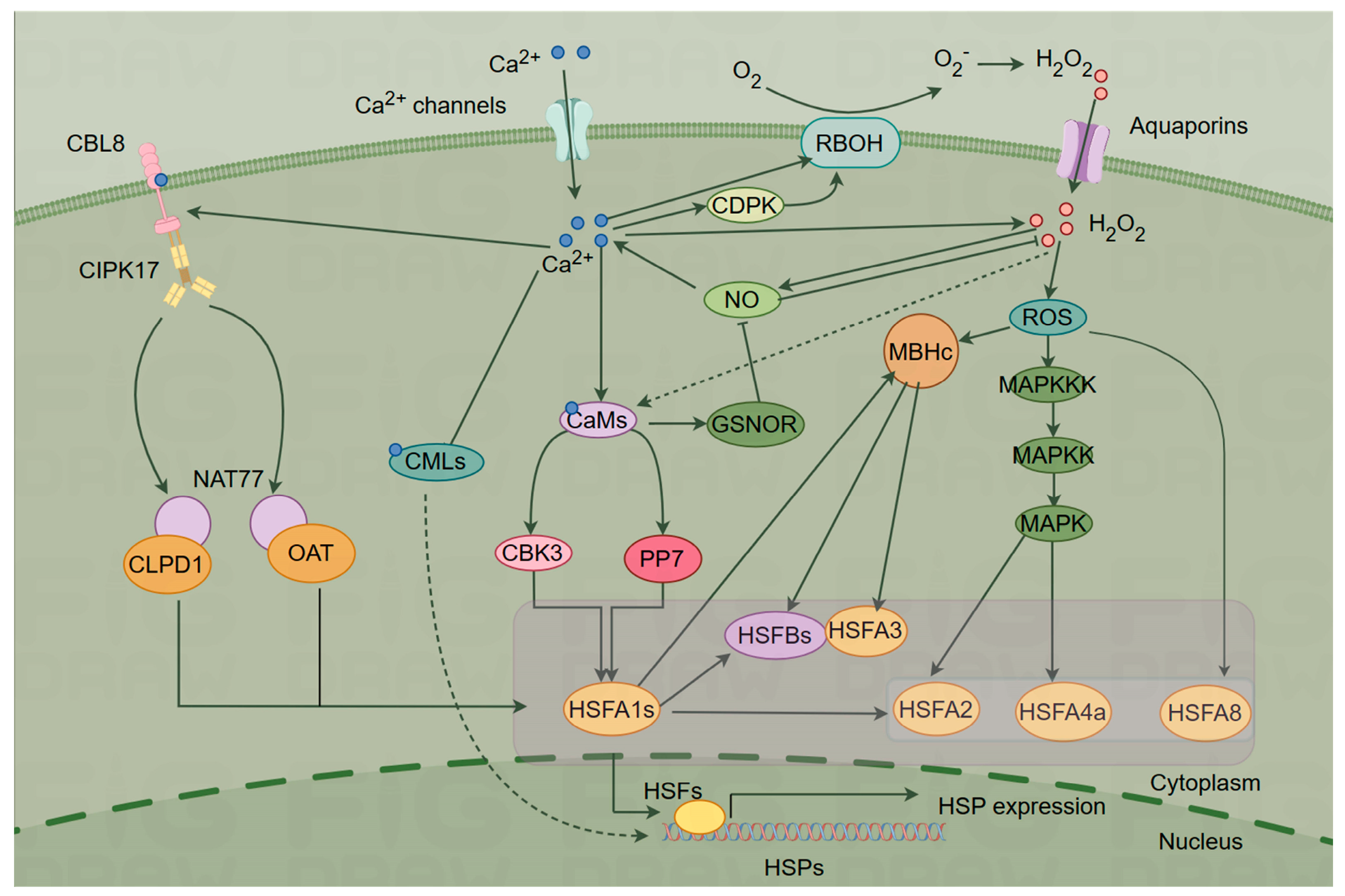

4. Ca2+ signaling networks mediate plant HS responses

| Gene type | Organism | Gene symbol | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaMs | Arabidopsis thaliana | AtCaM3 | Tolerance to heat stress | [84,85] |

| Cucumis sativus L. | CsCaM3 | Tolerance to heat stress; Safeguards against oxidative damage | [86] | |

| Oryza sativa L. | OsCaM1-1 | Tolerance to heat stress | [87] | |

| CMLs | Arabidopsis thaliana | AtCML12 | Gene expression significantly increased under heat stress | [89] |

| AtCML24 | Gene expression significantly increased under heat stress | [89] | ||

| Oryza sativa L. | OsMSR2 | Response to cold, drought, and heat stress | [90] | |

| Solanum lycopersicum L. | SlCML39 | Negative impact on high-temperature tolerance | [91] | |

| CDPKs | Arabidopsis thaliana | AtCPK1 | Tolerance to salt, cold, and heat | [97] |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. | LeCPK28 | Tolerance to heat stress | [98] | |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. | LeCPK2 | Tolerance to heat stress | [99] | |

| Zea mays L. | ZmCPK7 | Tolerance to heat stress | [100] | |

| ZmCK3 | Exhibits increased transcription in response to drought, salt, and heat stress | [101] | ||

| Setaria italica | SiCDPK7 | Response to extreme temperature stress | [102] | |

| Vitis amurensis Rupr. | VaCPK29 | Response to heat and osmotic stress | [103] | |

| CBLs | Oryza sativa L. | OsCBL8 | Enhances resistance to high temperatures and pathogens | [112] |

| CIPKs | Oryza sativa L. | OsCIPK17 | Enhances resistance to high temperatures and pathogens | [112] |

| Ananas comosus | AcCIPK5 | Promotes tolerance to salt, osmotic stress, and cold stress while negatively regulating heat stress responses | [113] |

4.1. ROS-mediated signaling

4.2. NO signaling

4.3. HSF–HSP signaling

5. Conclusions and perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fitter, A.H.; Fitter, R.S.R. Rapid changes in flowering time in British plants. Science 2002, 296, 1689–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, B.; Piao, S.; Wang, X.; Lobell, D.B.; Huang, Y.; Huang, M.; Yao, Y.; Bassu, S.; Ciais, P.; Durand, J.L.; Elliott, J.; Ewert, F.; Janssens, I.A.; Li, T.; Lin, E.; Liu, Q.; Martre, P.; Müller, C.; Peng, S.; Peñuelas, J.; Ruane, A.C.; Wallach, D.; Wang, T.; Wu, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Asseng, S. Temperature increase reduces global yields of major crops in four independent estimates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, 9326–9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Gao, K.; Ren, H.; Tang, W. Molecular mechanisms governing plant responses to high temperatures. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 757–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, A.N.; Kudla, J.; Sanders, D. The language of calcium signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 593–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finka, A.; Cuendet, A.F.; Maathuis, F.J.; Saidi, Y.; Goloubinoff, P. Plasma membrane cyclic nucleotide gated calcium channels control land plant thermal sensing and acquired thermotolerance. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3333–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudla, J.; Batistic, O.; Hashimoto, K. Calcium signals: the lead currency of plant information processing. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 541–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batistič, O.; Kudla, J. Analysis of calcium signaling pathways in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012, 1820, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirayesh, N.; Giridhar, M.; Ben Khedher, A.; Vothknecht, U.C.; Chigri, F. Organellar calcium signaling in plants: An update. Biochim. Biophys Acta. Mol. Cell Res. 2021, 1868, 118948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swarbreck, S.M.; Colaço, R.; Davies, J.M. Plant calcium-permeable channels. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jammes, F.; Hu, H.C.; Villiers, F.; Bouten, R.; Kwak, J.M. Calcium-permeable channels in plant cells. Febs j. 2011, 278, 4262–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, B.; Sherman, T.; Fromm, H. Cyclic nucleotide-gated channels in plants. FEBS Lett 2007, 581, 2237–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFalco, T.A.; Marshall, C.B.; Munro, K.; Kang, H.G.; Moeder, W.; Ikura, M.; Snedden, W.A.; Yoshioka, K. Multiple calmodulin-binding sites positively and negatively regulate Arabidopsis cyclic nucleotide-gated channel 12. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 1738–1751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fischer, C.; Kugler, A.; Hoth, S.; Dietrich, P. An IQ domain mediates the interaction with calmodulin in a plant cyclic nucleotide-gated channel. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuurink, R.C.; Shartzer, S.F.; Fath, A.; Jones, R.L. Characterization of a calmodulin-binding transporter from the plasma membrane of barley aleurone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 1944–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäser, P.; Thomine, S.; Schroeder, J.I.; Ward, J.M.; Hirschi, K.; Sze, H.; Talke, I.N.; Amtmann, A.; Maathuis, F.J.; Sanders, D.; Harper, J.F.; Tchieu, J.; Gribskov, M.; Persans, M.W.; Salt, D.E.; Kim, S.A.; Guerinot, M.L. Phylogenetic relationships within cation transporter families of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 1646–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, D.; Fraser, M.E.; Moorhead, G.B. Cyclic nucleotide binding proteins in the Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa genomes. BMC Bioinform. 2005, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Lan, W.; Jiang, Y.; Fang, W.; Luan, S. A calcium-dependent protein kinase interacts with and activates a calcium channel to regulate pollen tube growth. Mol. Plant 2014, 7, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Pan, Y.; Tian, W.; Dong, M.; Zhu, H.; Luan, S.; Li, L. Arabidopsis CNGC14 mediates calcium influx required for tip growth in root hairs. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 1004–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiasson, D.M.; Haage, K.; Sollweck, K.; Brachmann, A.; Dietrich, P.; Parniske, M. A quantitative hypermorphic CNGC allele confers ectopic calcium flux and impairs cellular development. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Kang, Y.; Ma, C.; Miao, R.; Wu, C.; Long, Y.; Ge, T.; Wu, Z.; Hou, X.; Zhang, J.; Qi, Z. CNGC2 Is a Ca2+ Influx Channel That Prevents Accumulation of Apoplastic Ca2+ in the Leaf. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 1342–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katano, K.; Kataoka, R.; Fujii, M.; Suzuki, N. Differences between seedlings and flowers in anti-ROS based heat responses of Arabidopsis plants deficient in cyclic nucleotide gated channel 2. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 123, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoen, M.P.; Davila Olivas, N.H.; Kloth, K.J.; Coolen, S.; Huang, P.P.; Aarts, M.G.; Bac-Molenaar, J.A.; Bakker, J.; Bouwmeester, H.J.; Broekgaarden, C.; Bucher, J.; Busscher-Lange, J.; Cheng, X.; Fradin, E.F.; Jongsma, M.A.; Julkowska, M.M.; Keurentjes, J.J.; Ligterink, W.; Pieterse, C.M.; Ruyter-Spira, C.; Smant, G.; Testerink, C.; Usadel, B.; van Loon, J.J.; van Pelt, J.A.; van Schaik, C.C.; van Wees, S.C.; Visser, R.G.; Voorrips, R.; Vosman, B.; Vreugdenhil, D.; Warmerdam, S.; Wiegers, G.L.; van Heerwaarden, J.; Kruijer, W.; van Eeuwijk, F.A.; Dicke, M. Genetic architecture of plant stress resistance: multi-trait genome-wide association mapping. New Phytol. 2017, 213, 1346–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Han, X.W.; Wu, J.H.; Zheng, S.Z.; Shang, Z.L.; Sun, D.Y.; Zhou, R.G.; Li, B. A heat-activated calcium-permeable channel - Arabidopsis cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel 6 - is involved in heat shock responses. Plant J. 2012, 70, 1056–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Ai, L.; Wu, D.; Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, L. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel 6 mediates thermotolerance in Arabidopsis seedlings by regulating hydrogen peroxide production via cytosolic calcium ions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 708672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Zhao, L. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel 6 mediates thermotolerance in Arabidopsis seedlings by regulating nitric oxide production via cytosolic calcium ions. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Lu, S.; Li, Z.; Cheng, J.; Hu, P.; Zhu, T.; Wang, X.; Jin, M.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Huang, S.; Zou, B.; Hua, J. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels 14 and 16 promote tolerance to heat and chilling in rice. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 1794–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, Z.; Kakar, K.U.; Saand, M.A.; Shu, Q.Y. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel gene family in rice, identification, characterization and experimental analysis of expression response to plant hormones, biotic and abiotic stresses. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, M.L. Structural biology of glutamate receptor ion channel complexes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016, 41, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, H.M.; Chiu, J.; Hsieh, M.H.; Meisel, L.; Oliveira, I.C.; Shin, M.; Coruzzi, G. Glutamate-receptor genes in plants. Nature 1998, 396, 125–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, B.; Becker, D.; Hedrich, R.; DeSalle, R.; Hollmann, M.; Kwak, J.M.; Schroeder, J.I.; Le Novère, N.; Nam, H.G.; Spalding, E.P.; Tester, M.; Turano, F.J.; Chiu, J.; Coruzzi, G. The identity of plant glutamate receptors. Science 2001, 292, 1486–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, S.; Song, X.; Shen, Y.; Chen, H.; Yu, J.; Yi, K.; Liu, Y.; Karplus, V.J.; Wu, P.; Deng, X.W. A rice glutamate receptor-like gene is critical for the division and survival of individual cells in the root apical meristem. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, P.; Anschütz, U.; Kugler, A.; Becker, D. Physiology and biophysics of plant ligand-gated ion channels. Plant Biol. 2010, 12 (Suppl. 1), 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, B.C.; Mukherjee, A. Computational analysis of the glutamate receptor gene family of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2017, 35, 2454–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, J.M.; Mäser, P.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant ion channels: gene families, physiology, and functional genomics analyses. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2009, 71, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, R. Glutamate receptors in plants. Ann. Bot. 2002, 90, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Recatalà, V. New roles for the glutamate receptor-like 3.3, 3.5, and 3.6 genes as on/off switches of wound-induced systemic electrical signals. Plant Signal Behav. 2016, 11, e1161879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.N.; Gangwar, S.P.; Michard, E.; Simon, A.A.; Portes, M.T.; Barbosa-Caro, J.; Wudick, M.M.; Lizzio, M.A.; Klykov, O.; Yelshanskaya, M.V.; Feijó, J.A.; Sobolevsky, A.I. Structure of the Arabidopsis thaliana glutamate receptor-like channel GLR3.4. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 3216–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Hu, H.C.; Okuma, E.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.S.; Munemasa, S.; Cho, D.; Ju, C.; Pedoeim, L.; Rodriguez, B.; Wang, J.; Im, W.; Murata, Y.; Pei, Z.M.; Kwak, J.M. L-Met activates Arabidopsis GLR Ca2+ channels upstream of ROS production and regulates stomatal movement. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 2553–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, N.; Zhan, C.; Song, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qi, J.; Wu, J. The glutamate receptor-like 3.3 and 3.6 mediate systemic resistance to insect herbivores in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 7611–7627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Fichman, Y.; Mittler, R. Vascular bundles mediate systemic reactive oxygen signaling during light stress. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 3425–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, H.; Kelloniemi, J.; Chiltz, A.; Wendehenne, D.; Pugin, A.; Poinssot, B.; Garcia-Brugger, A. Involvement of the glutamate receptor AtGLR3.3 in plant defense signaling and resistance to Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis. Plant J. 2013, 76, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, R.; Mori, I.C.; Kamizono, N.; Shichiri, Y.; Shimatani, T.; Miyata, F.; Honda, K.; Iwai, S. Glutamate functions in stomatal closure in Arabidopsis and fava bean. J. Plant Res. 2016, 129, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Duan, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhao, J.; Lin, H. Patellin protein family functions in plant development and stress response. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 234–235, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.G.; Ye, X.Y.; Qiu, X.M. Glutamate signaling enhances the heat tolerance of maize seedlings by plant glutamate receptor-like channels-mediated calcium signaling. Protoplasma 2019, 256, 1165–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortimer, J.C.; Laohavisit, A.; Macpherson, N.; Webb, A.; Brownlee, C.; Battey, N.H.; Davies, J.M. Annexins: multifunctional components of growth and adaptation. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.M. Annexin-mediated calcium signalling in plants. Plants 2014, 3, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorecka, K.M.; Konopka-Postupolska, D.; Hennig, J.; Buchet, R.; Pikula, S. Peroxidase activity of annexin 1 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 336, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerke, V.; Creutz, C.E.; Moss, S.E. Annexins: linking Ca2+ signalling to membrane dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.B.; Sessions, A.; Eastburn, D.J.; Roux, S.J. Differential expression of members of the annexin multigene family in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 1072–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jami, S.K.; Clark, G.B.; Ayele, B.T.; Roux, S.J.; Kirti, P.B. Identification and characterization of annexin gene family in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tang, Y.; Gao, S.; Su, S.; Hong, L.; Wang, W.; Fang, Z.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Quan, W.; Sun, H.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X.; Gao, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, L.; Zhao, C. Comprehensive analyses of the annexin gene family in wheat. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, V.; Moss, S.E. Annexins: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 331–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, R.B.; Ben Romdhane, W.; Ben Hsouna, A.; Mihoubi, W.; Harbaoui, M.; Brini, F. Insights into plant annexins function in abiotic and biotic stress tolerance. Plant Signal Behav. 2020, 15, 1699264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laohavisit, A.; Davies, J.M. Annexins. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Bian, Y.; Ren, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, F.; Ding, H. A critical review on plant annexin: Structure, function, and mechanism. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 190, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, L.; Tsang, E.W.; Wu, K.; Huang, S. Proteomic and functional analyses of Nelumbo nucifera annexins involved in seed thermotolerance and germination vigor. Planta 2012, 235, 1271–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liu, X.; Jia, Y.; Yu, X.; Ma, H. GmANN, a glutathione S-transferase-interacting annexin, is involved in high temperature and humidity tolerance and seed vigor formation in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2019, 138, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, D.; Wang, H.; Yin, J.; Wang, R.; He, M.; Cui, M.; Shang, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhu, Z. A calcium-binding protein, rice annexin OsANN1, enhances heat stress tolerance by modulating the production of H2O2. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 5853–5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Ying, J.; Xu, L.; Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Mei, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, L. Characterization of annexin gene family and functional analysis of RsANN1a involved in heat tolerance in radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 2027–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Yang, H.; Xue, Y.; Kong, D.; Ye, R.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Theprungsirikul, L.; Shrift, T.; Krichilsky, B.; Johnson, D.M.; Swift, G.B.; He, Y.; Siedow, J.N.; Pei, Z.M. OSCA1 mediates osmotic-stress-evoked Ca2+ increases vital for osmosensing in Arabidopsis. Nature 2014, 514, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, F.; Wen, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhu, T.; Zhuo, W.; Jin, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Pei, Z.M.; Han, S. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of the OSCA gene family in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Feng, X.; Du, H.; Wang, H. Genome-wide analysis of maize OSCA family members and their involvement in drought stress. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, Y.; Yang, F.; Magwanga, R.O.; Cai, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, F.; Zhou, Z. Genome-wide identification of OSCA gene family and their potential function in the regulation of dehydration and salt stress in Gossypium hirsutum. J. Cotton Res. 2019, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Hou, L.; Yu, J.; Jia, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, M.; Qin, J.; Cao, N.; Cui, J.; Shi, W. Preliminary expression analysis of the OSCA gene family in Maize and their involvement in temperature stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haswell, E.S.; Meyerowitz, E.M. MscS-like proteins control plastid size and shape in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, E.S.; Haswell, E.S. The tension-sensitive ion transport activity of MSL8 is critical for its function in pollen hydration and germination. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 1222–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyronnet, R.; Haswell, E.S.; Barbier-Brygoo, H.; Frachisse, J.M. AtMSL9 and AtMSL10: Sensors of plasma membrane tension in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008, 3, 726–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Sun, J.; Mao, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Zheng, H.; Zhen, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zou, D. Genome-wide characterization and identification of trihelix transcription factor and expression profiling in response to abiotic stresses in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Katagiri, T.; Shinozaki, K.; Qi, Z.; Tatsumi, H.; Furuichi, T.; Kishigami, A.; Sokabe, M.; Kojima, I.; Sato, S.; Kato, T.; Tabata, S.; Iida, K.; Terashima, A.; Nakano, M.; Ikeda, M.; Yamanaka, T.; Iida, H. Arabidopsis plasma membrane protein crucial for Ca2+ influx and touch sensing in roots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 3639–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurusu, T.; Yamanaka, T.; Nakano, M.; Takiguchi, A.; Ogasawara, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Iida, K.; Hanamata, S.; Shinozaki, K.; Iida, H.; Kuchitsu, K. Involvement of the putative Ca²⁺-permeable mechanosensitive channels, NtMCA1 and NtMCA2, in Ca²⁺ uptake, Ca²⁺-dependent cell proliferation and mechanical stress-induced gene expression in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) BY-2 cells. J. Plant Res. 2012, 125, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, T.; Nakagawa, Y.; Mori, K.; Nakano, M.; Imamura, T.; Kataoka, H.; Terashima, A.; Iida, K.; Kojima, I.; Katagiri, T.; Shinozaki, K.; Iida, H. MCA1 and MCA2 that mediate Ca2+ uptake have distinct and overlapping roles in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1284–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K.; Renhu, N.; Naito, M.; Nakamura, A.; Shiba, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Suzaki, T.; Iida, H.; Miura, K. Ca2+-permeable mechanosensitive channels MCA1 and MCA2 mediate cold-induced cytosolic Ca2+ increase and cold tolerance in Arabidopsis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coste, B.; Mathur, J.; Schmidt, M.; Earley, T.J.; Ranade, S.; Petrus, M.J.; Dubin, A.E.; Patapoutian, A. Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science 2010, 330, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurusu, T.; Kuchitsu, K.; Nakano, M.; Nakayama, Y.; Iida, H. Plant mechanosensing and Ca2+ transport. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Tong, X.; Liu, S.Y.; Chai, L.X.; Zhu, F.F.; Zhang, X.P.; Zou, J.Z.; Wang, X.B. Genetic analysis of a Piezo-like protein suppressing systemic movement of plant viruses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, H. Calcium signaling during abiotic stress in plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2000, 195, 269–324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohanta, T.K.; Yadav, D.; Khan, A.L.; Hashem, A.; Abd Allah, E.F.; Al-Harrasi, A. Molecular players of EF-hand containing calcium signaling event in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braam, J.; Davis, R.W. Rain-, wind-, and touch-induced expression of calmodulin and calmodulin-related genes in Arabidopsis. Cell 1990, 60, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quraan, N.A.; Locy, R.D.; Singh, N.K. Expression of calmodulin genes in wild type and calmodulin mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana under heat stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.S.; Kim, M.C.; Yoo, J.H.; Moon, B.C.; Koo, S.C.; Park, B.O.; Lee, J.H.; Koo, Y.D.; Han, H.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Chung, W.S.; Lim, C.O.; Cho, M.J. Isolation of a calmodulin-binding transcription factor from rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 40820–40831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoim, P.R.; de Carvalho, T.L.; Ballesteros, H.G.; Bellieny-Rabelo, D.; Rojas, C.A.; Venancio, T.M.; Ferreira, P.C.; Hemerly, A.S. Genome-wide transcriptome profiling provides insights into the responses of maize (Zea mays L.) to diazotrophic bacteria. Plant and Soil. 2020, 451, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, J.L.; Walsh, M.P.; Vogel, H.J. Structures and metal-ion-binding properties of the Ca2+-binding helix-loop-helix EF-hand motifs. Biochem. J. 2007, 405, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, P.; Nehra, A.; Gill, R.; Tuteja, N.; Gill, S.S. Unraveling the importance of EF-hand-mediated calcium signaling in plants. S. AFR. J. BOT. 2022, 148, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, R.G.; Gao, Y.J.; Zheng, S.Z.; Xu, P.; Zhang, S.Q.; Sun, D.Y. Molecular and genetic evidence for the key role of AtCaM3 in heat-shock signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 1773–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, L. Nitric oxide functions as a signal and acts upstream of AtCaM3 in thermotolerance in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 1895–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Yan, S.; Zhou, H.; Dong, R.; Lei, J.; Chen, C.; Cao, B. Overexpression of CsCaM3 improves high temperature tolerance in cucumber. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.C.; Luo, D.L.; Vignols, F.; Jinn, T.L. Heat shock-induced biphasic Ca2+ signature and OsCaM1-1 nuclear localization mediate downstream signalling in acquisition of thermotolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 1543–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, E.; Tsai, Y.C.; Braam, J. Handling calcium signaling: Arabidopsis CaMs and CMLs. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braam, J. Regulated expression of the calmodulin-related TCH genes in cultured Arabidopsis cells: induction by calcium and heat shock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992, 89, 3213–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.Y.; Rocha, P.S.; Wang, M.L.; Xu, M.L.; Cui, Y.C.; Li, L.Y.; Zhu, Y.X.; Xia, X. A novel rice calmodulin-like gene, OsMSR2, enhances drought and salt tolerance and increases ABA sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Planta 2011, 234, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Qian, Y.; Fang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Sheng, J.; Ge, C. Characteristics of SiCML39, a tomato calmodulin-like gene, and its negative role in high temperature tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana during germination and seedling growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, R.M.; Shahid, L.; Waqas, M.; Ali, B.; Rashid, M.A.R.; Azeem, F.; Nawaz, M.A.; Wani, S.H.; Chung, G. Insights on calcium-dependent protein kinases (CPKs) signaling for abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip Delormel, T.; Boudsocq, M. Properties and functions of calcium-dependent protein kinases and their relatives in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2019, 224, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.H.; Willmann, M.R.; Chen, H.C.; Sheen, J. Calcium signaling through protein kinases. The Arabidopsis calcium-dependent protein kinase gene family. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Lv, X.; Xia, X.; Zhou, J.; Shi, K.; Yu, J.; Zhou, Y. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of calcium-dependent protein kinase in tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.; Lv, W.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, D.; Cai, G.; Pan, J.; Li, D. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of calcium-dependent protein kinase in maize. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veremeichik, G.N.; Shkryl, Y.N.; Gorpenchenko, T.Y.; Silantieva, S.A.; Avramenko, T.V.; Brodovskaya, E.V.; Bulgakov, V.P. Inactivation of the auto-inhibitory domain in Arabidopsis AtCPK1 leads to increased salt, cold and heat tolerance in the AtCPK1-transformed Rubia cordifolia L cell cultures. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 159, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Li, J.; Ding, S.; Cheng, F.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, J.; Foyer, C.H.; Shi, K. The protein kinase CPK28 phosphorylates ascorbate peroxidase and enhances thermotolerance in tomato. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 1302–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.J.; Su, H.S.; Li, W.J.; Zhang, Z.L. Expression profiling of a novel calcium-dependent protein kinase gene, LeCPK2, from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) under heat and pathogen-related hormones. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 2427–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Du, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, S.; Li, C.; Chen, N.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, L.; Hu, X. The calcium-dependent protein kinase ZmCDPK7 functions in heat-stress tolerance in maize. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-T.; Song, W. ZmCK3, a maize calcium-dependent protein kinase gene, endows tolerance to drought and heat stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis. J. Plant Biochem. 2014, 23, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.-T.; Hou, Z.-H.; Wang, Y.; Hao, J.-M.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, W.; Wang, D.-M.; Xu, Z.-S.; Song, X.; Wang, F.; Li, R. Foxtail millet SiCDPK7 gene enhances tolerance to extreme temperature stress in transgenic plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 207, 105197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrovina, A.S.; Kiselev, K.V.; Khristenko, V.S.; Aleynova, O.A. The calcium-dependent protein kinase gene VaCPK29 is involved in grapevine responses to heat and osmotic stresses. Plant Growth Regula. 2017, 82, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Han, Y.T.; Zhao, F.L.; Hu, Y.; Gao, Y.R.; Ma, Y.F.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Wen, Y.Q. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the CDPK gene family in grape, vitis spp. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, W.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, M.; Niu, F.; Yang, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Liang, W.; Deyholos, M.K.; Jiang, Y.Q. Identification, expression and interaction analyses of calcium-dependent protein kinase (CPK) genes in canola (Brassica napus L.). BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 211. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.; Wang, W.; Duan, W.; Li, Y.; Hou, X. Comprehensive analysis of the CDPK-SnRK superfamily genes in chinese cabbage and its evolutionary implications in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Liu, M.; Lu, L.; He, M.; Qu, W.; Xu, Q.; Qi, X.; Chen, X. Genome-wide analysis and expression of the calcium-dependent protein kinase gene family in cucumber. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2015, 290, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Cheng, J.; Yan, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Li, J.; Mou, S.; Qiu, A.; Lai, Y.; Guan, D.; He, S. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of calcium-dependent protein kinase and its closely related kinase genes in Capsicum annuum. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, J.K. A calcium sensor homolog required for plant salt tolerance. Science 1998, 280, 1943–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, S. The CBL-CIPK network in plant calcium signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, S.K.; Mahiwal, S.; Nambiar, D.M.; Pandey, G.K. CBL-CIPK module-mediated phosphoregulation: facts and hypothesis. Biochem. J. 2020, 477, 853–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Lu, S.; Zhou, R.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Fang, H.; Wang, B.; Chen, M.; Cao, Y. The OsCBL8-OsCIPK17 module regulates seedling growth and confers resistance to heat and drought in rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, M.; Greaves, J.G.; Jakada, B.H.; Fakher, B.; Wang, X.; Qin, Y. AcCIPK5, a pineapple CBL-interacting protein kinase, confers salt, osmotic and cold stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2022, 320, 111284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; He, R.J.; Xie, Q.L.; Zhao, X.H.; Deng, X.M.; He, J.B.; Song, L.; He, J.; Marchant, A.; Chen, X.Y.; Wu, A.M. Ethylene response factor 74 (ERF74) plays an essential role in controlling a respiratory burst oxidase homolog D (RbohD)-dependent mechanism in response to different stresses in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2017, 213, 1667–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, I.; Srikanth, S.; Chen, Z. Cross talk between H2O2 and interacting signal molecules under plant stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogasawara, Y.; Kaya, H.; Hiraoka, G.; Yumoto, F.; Kimura, S.; Kadota, Y.; Hishinuma, H.; Senzaki, E.; Yamagoe, S.; Nagata, K.; Nara, M.; Suzuki, K.; Tanokura, M.; Kuchitsu, K. Synergistic activation of the Arabidopsis NADPH oxidase AtrbohD by Ca2+ and phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 8885–8892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, S.; Kaya, H.; Kawarazaki, T.; Hiraoka, G.; Senzaki, E.; Michikawa, M.; Kuchitsu, K. Protein phosphorylation is a prerequisite for the Ca2+-dependent activation of Arabidopsis NADPH oxidases and may function as a trigger for the positive feedback regulation of Ca2+ and reactive oxygen species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012, 1823, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bienert, G.P.; Møller, A.L.; Kristiansen, K.A.; Schulz, A.; Møller, I.M.; Schjoerring, J.K.; Jahn, T.P. Specific aquaporins facilitate the diffusion of hydrogen peroxide across membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaimes-Miranda, F.; Chávez Montes, R.A. The plant MBF1 protein family: a bridge between stress and transcription. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 1782–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Miller, G.; Salazar, C.; Mondal, H.A.; Shulaev, E.; Cortes, D.F.; Shuman, J.L.; Luo, X.; Shah, J.; Schlauch, K.; Shulaev, V.; Mittler, R. Temporal-spatial interaction between reactive oxygen species and abscisic acid regulates rapid systemic acclimation in plants. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 3553–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Sejima, H.; Tam, R.; Schlauch, K.; Mittler, R. Identification of the MBF1 heat-response regulon of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2011, 66, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giesguth, M.; Sahm, A.; Simon, S.; Dietz, K.J. Redox-dependent translocation of the heat shock transcription factor AtHSFA8 from the cytosol to the nucleus in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, G.; Mittler, R. Could heat shock transcription factors function as hydrogen peroxide sensors in plants? Ann. Bot. 2006, 98, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovtun, Y.; Chiu, W.L.; Tena, G.; Sheen, J. Functional analysis of oxidative stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000, 97, 2940–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evrard, A.; Kumar, M.; Lecourieux, D.; Lucks, J.; von Koskull-Döring, P.; Hirt, H. Regulation of the heat stress response in Arabidopsis by MPK6-targeted phosphorylation of the heat stress factor HsfA2. PeerJ 2013, 1, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Salamó, I.; Papdi, C.; Rigó, G.; Zsigmond, L.; Vilela, B.; Lumbreras, V.; Nagy, I.; Horváth, B.; Domoki, M.; Darula, Z.; Medzihradszky, K.; Bögre, L.; Koncz, C.; Szabados, L. The heat shock factor A4A confers salt tolerance and is regulated by oxidative stress and the mitogen-activated protein kinases MPK3 and MPK6. Plant Physiol. 2014, 165, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Guo, Y.; Jia, L.; Chu, H.; Zhou, S.; Chen, K.; Wu, D.; Zhao, L. Hydrogen peroxide acts upstream of nitric oxide in the heat shock pathway in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 2184–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chu, H.; Jia, L.; Chen, K.; Zhao, L. A feedback inhibition between nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide in the heat shock pathway in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 75, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, B.; Ji, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Gao, L.L.; Ma, R.Y. Induction of heat shock protein genes is the hallmark of egg heat tolerance in Agasicles hygrophila (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2020, 113, 1972–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Huang, X.; Chen, L.; Sun, X.; Lu, C.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zuo, J. Site-specific nitrosoproteomic identification of endogenously S-nitrosylated proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 1731–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Brandizzi, F.; Benning, C.; Larkin, R.M. A membrane-tethered transcription factor defines a branch of the heat stress response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 16398–16403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.T.; Li, G.L.; Chang, H.; Sun, D.Y.; Zhou, R.G.; Li, B. Calmodulin-binding protein phosphatase PP7 is involved in thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.T.; Gao, F.; Li, G.L.; Han, J.L.; Liu, D.L.; Sun, D.Y.; Zhou, R.G. The calmodulin-binding protein kinase 3 is part of heat-shock signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2008, 55, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, T.; von Braun, J. Climate change impacts on global food security. Science 2013, 341, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; De Lima, C.F.F.; De Smet, I. The heat is on: how crop growth, development and yield respond to high temperature. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 7359–7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).