Submitted:

27 November 2023

Posted:

28 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

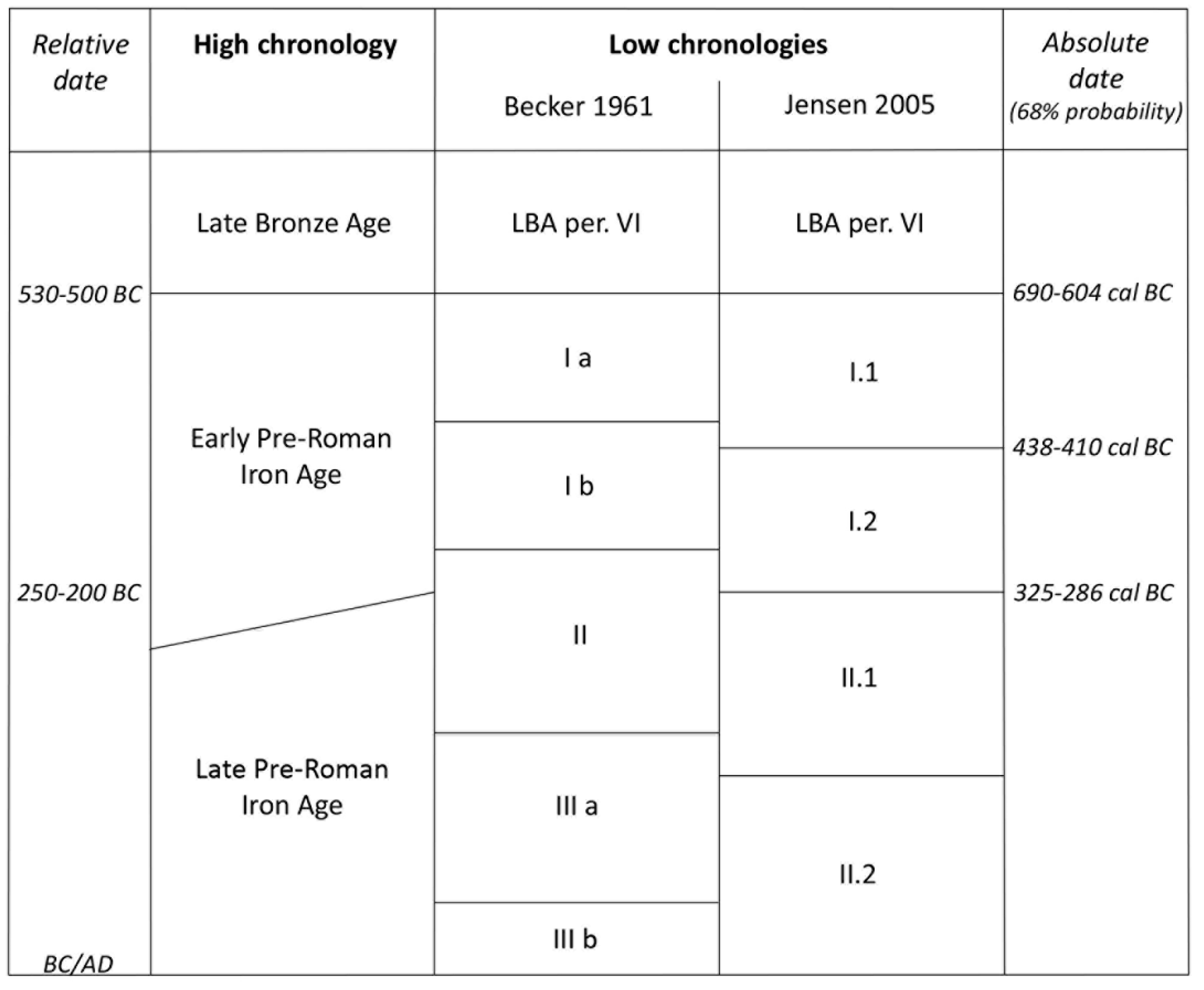

Dividing Time and Identifying Change

Modelling Change within a Bayesian Framework

Research Questions

Material and Methods

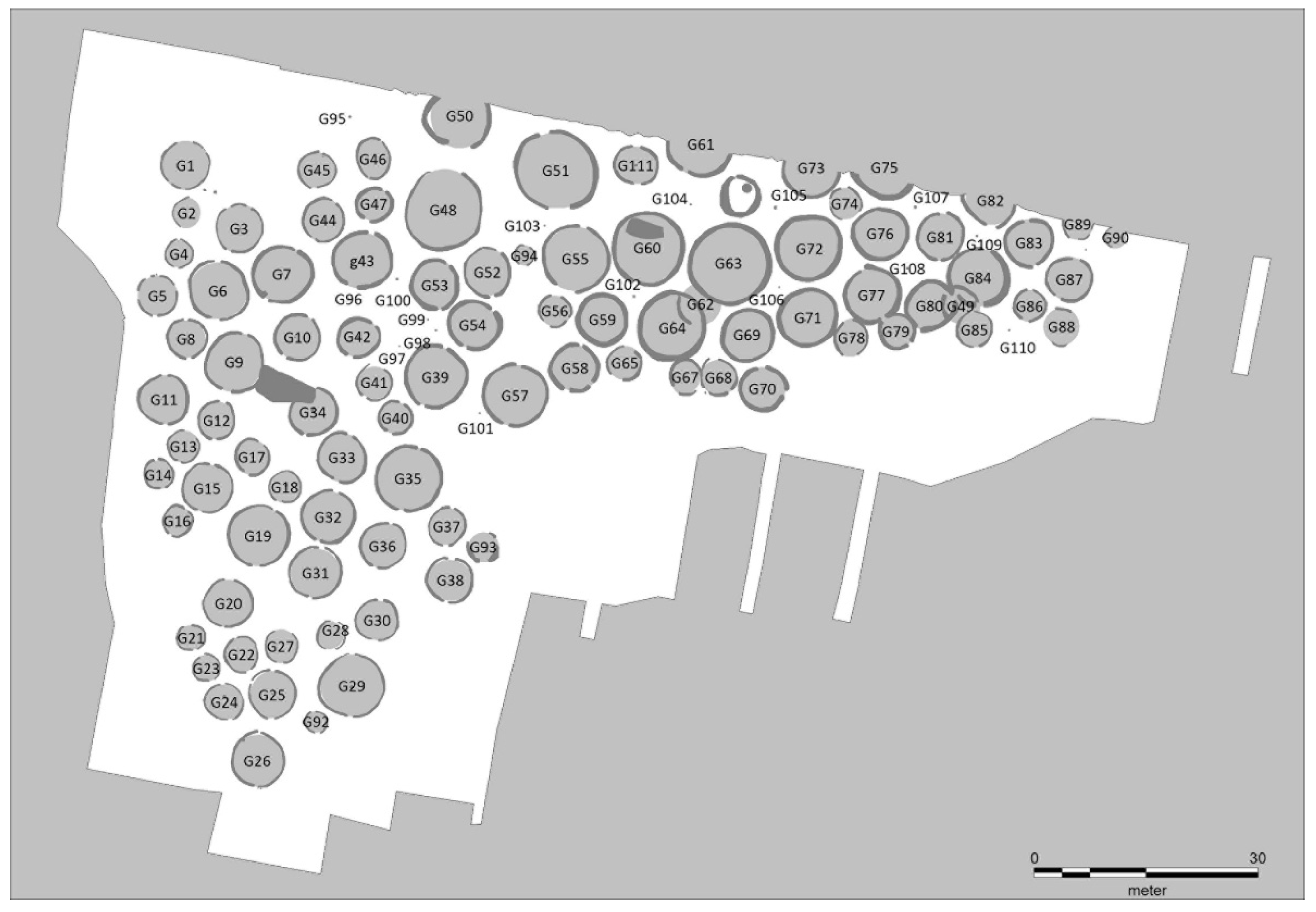

Sample Selection

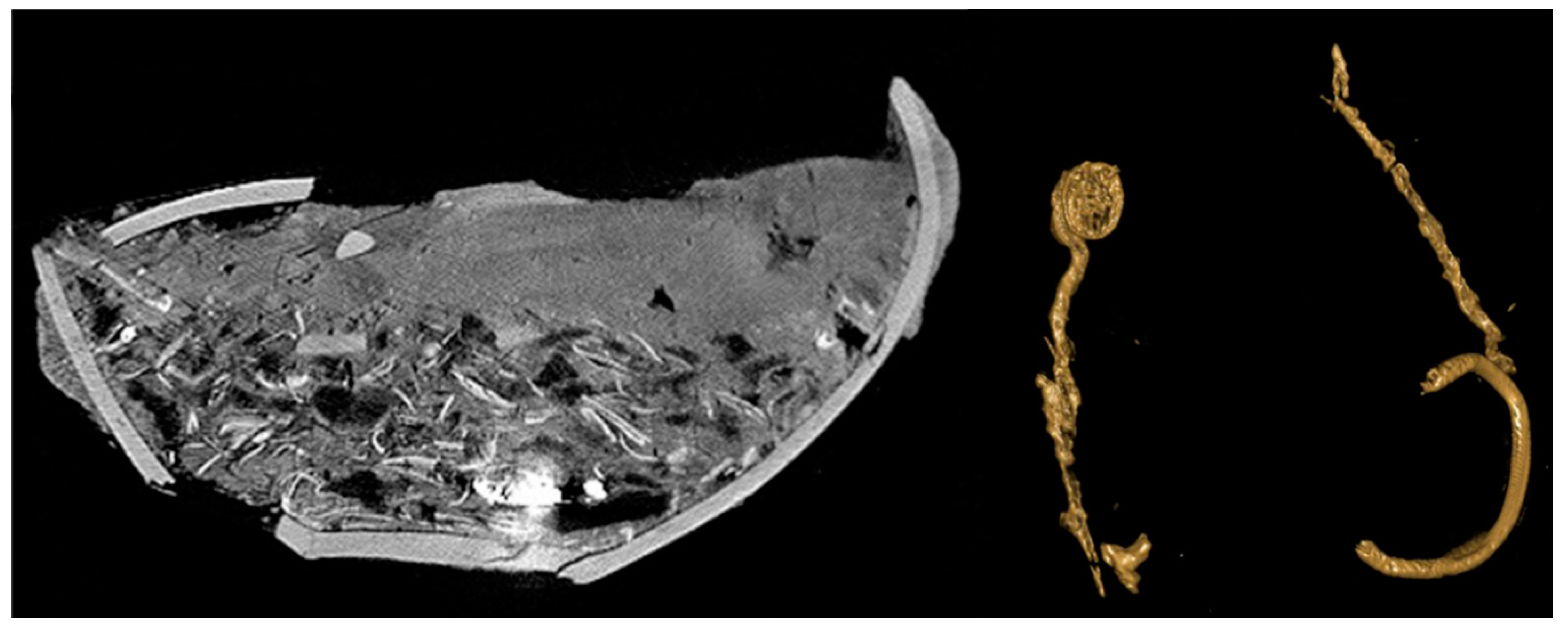

Laboratory Analyses

Pretreatment and Combustion

Graphitization and AMS Measurement

Results

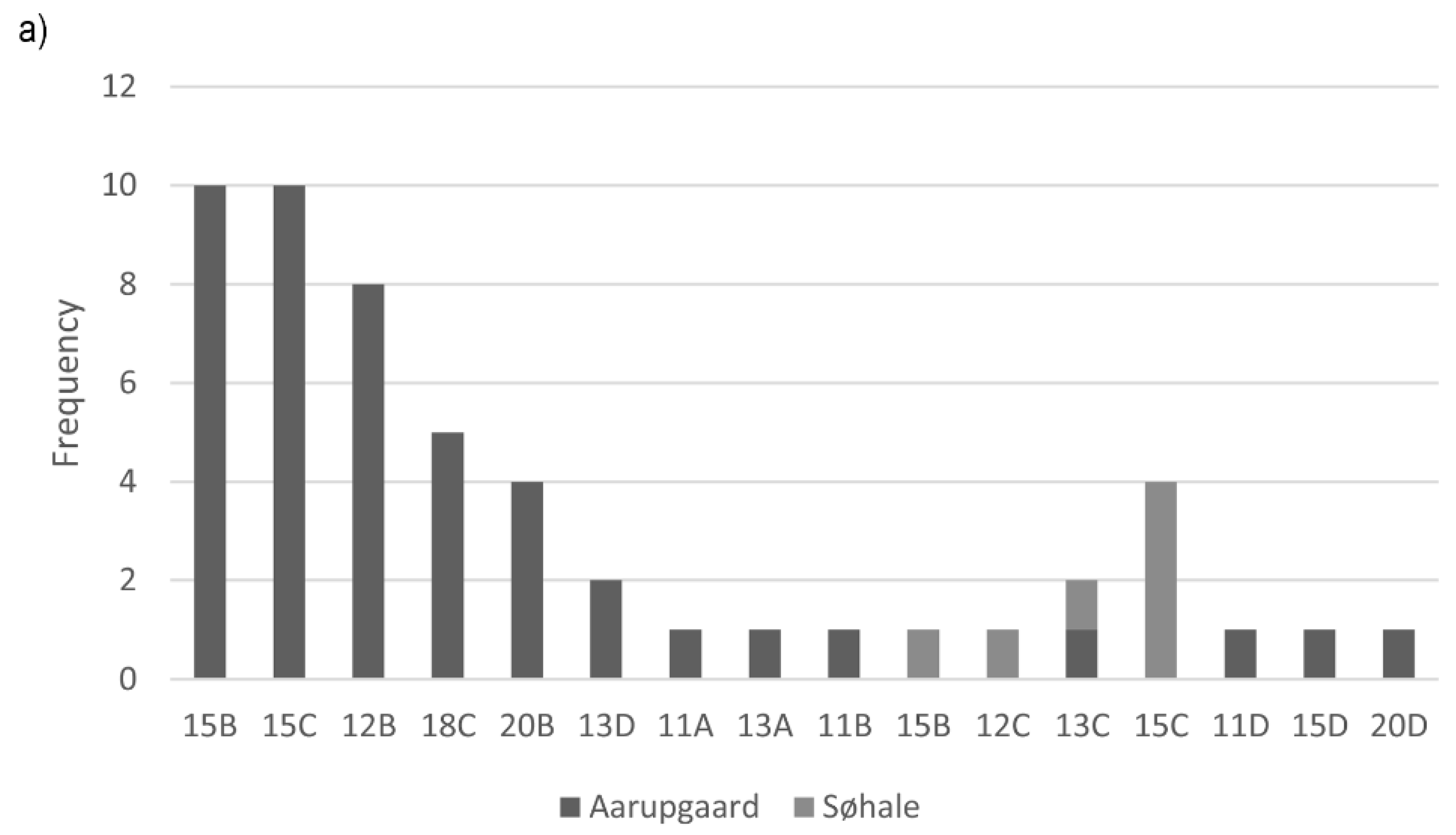

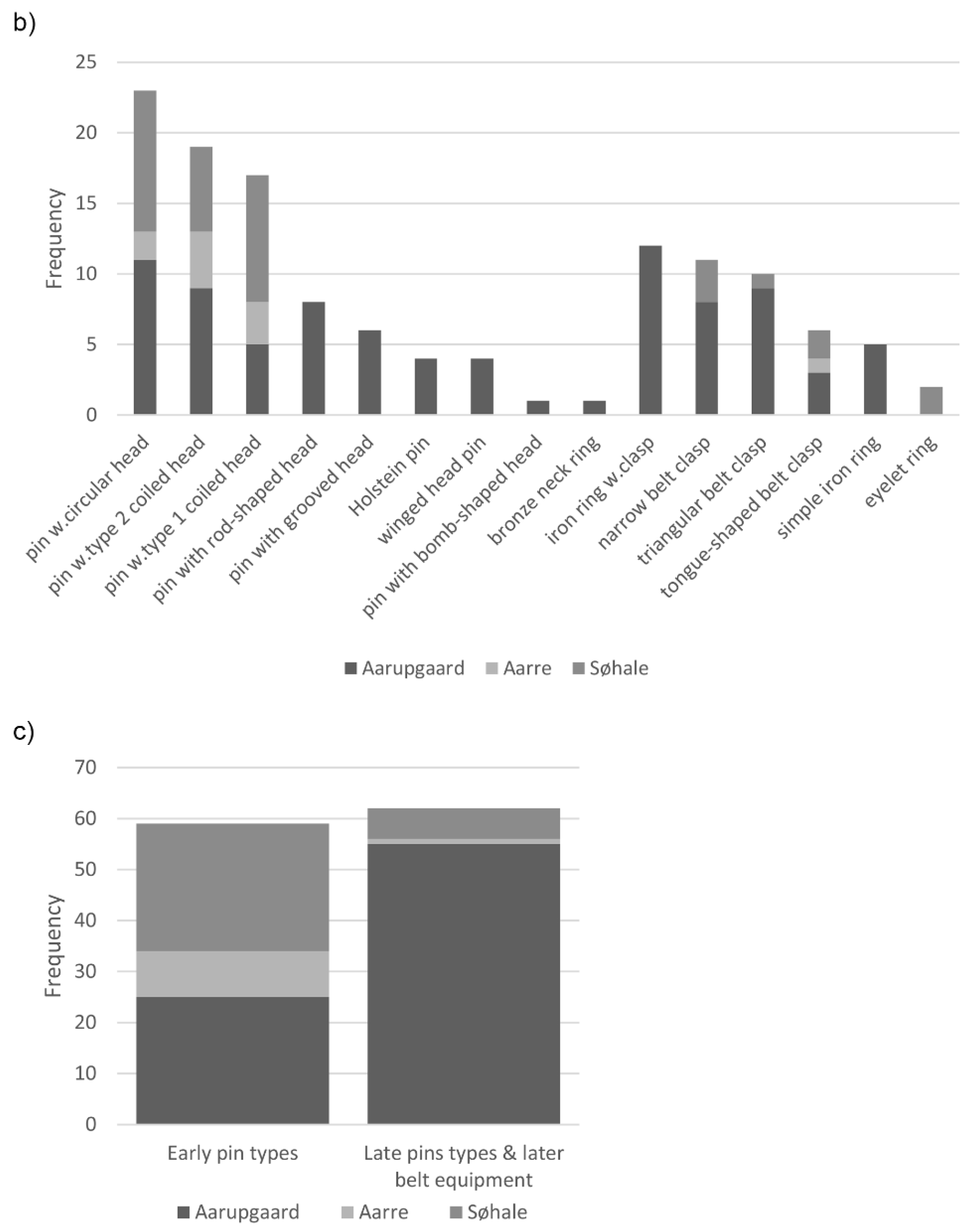

Artefact Frequencies

Radiocarbon Results

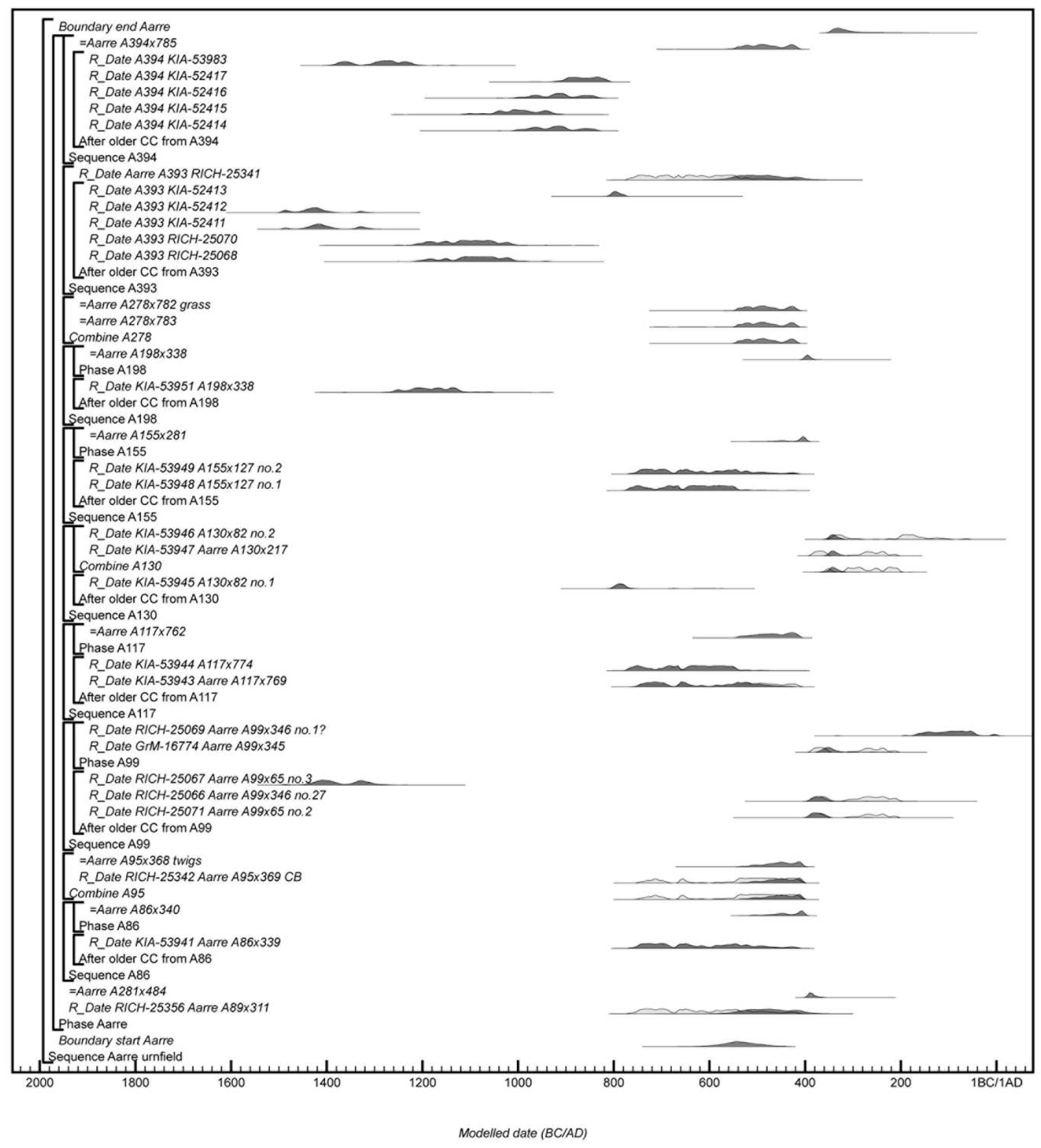

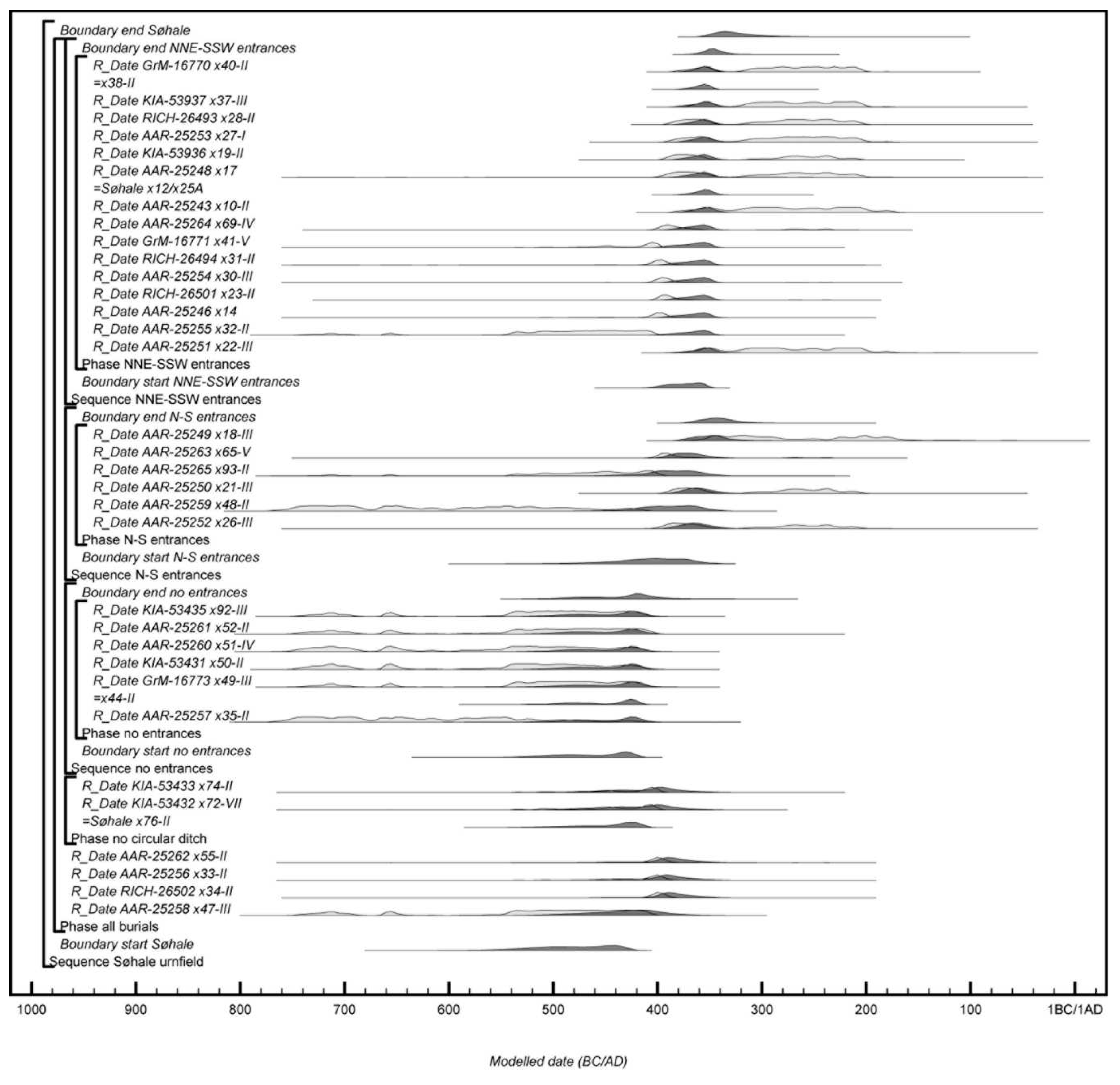

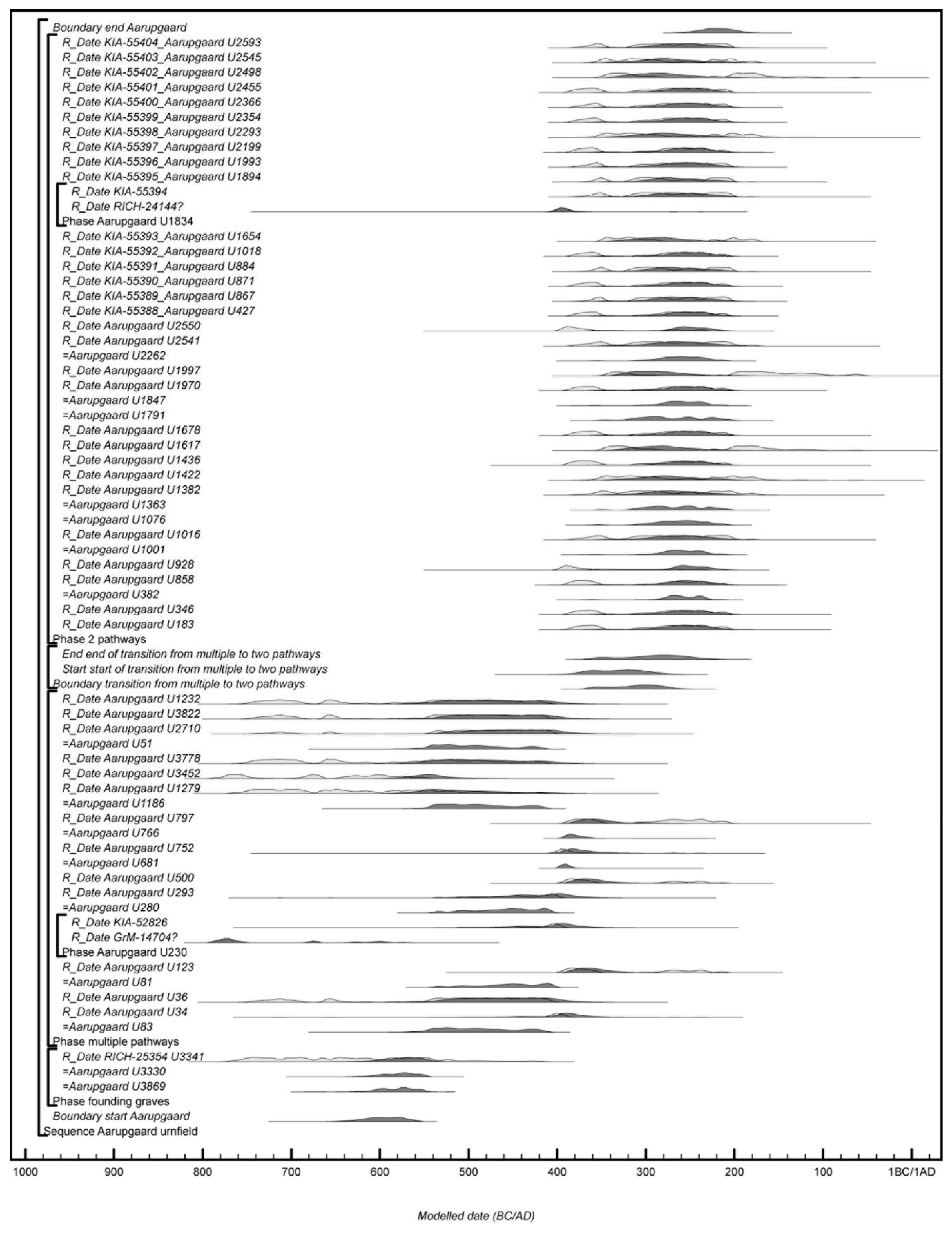

Chronological Modelling

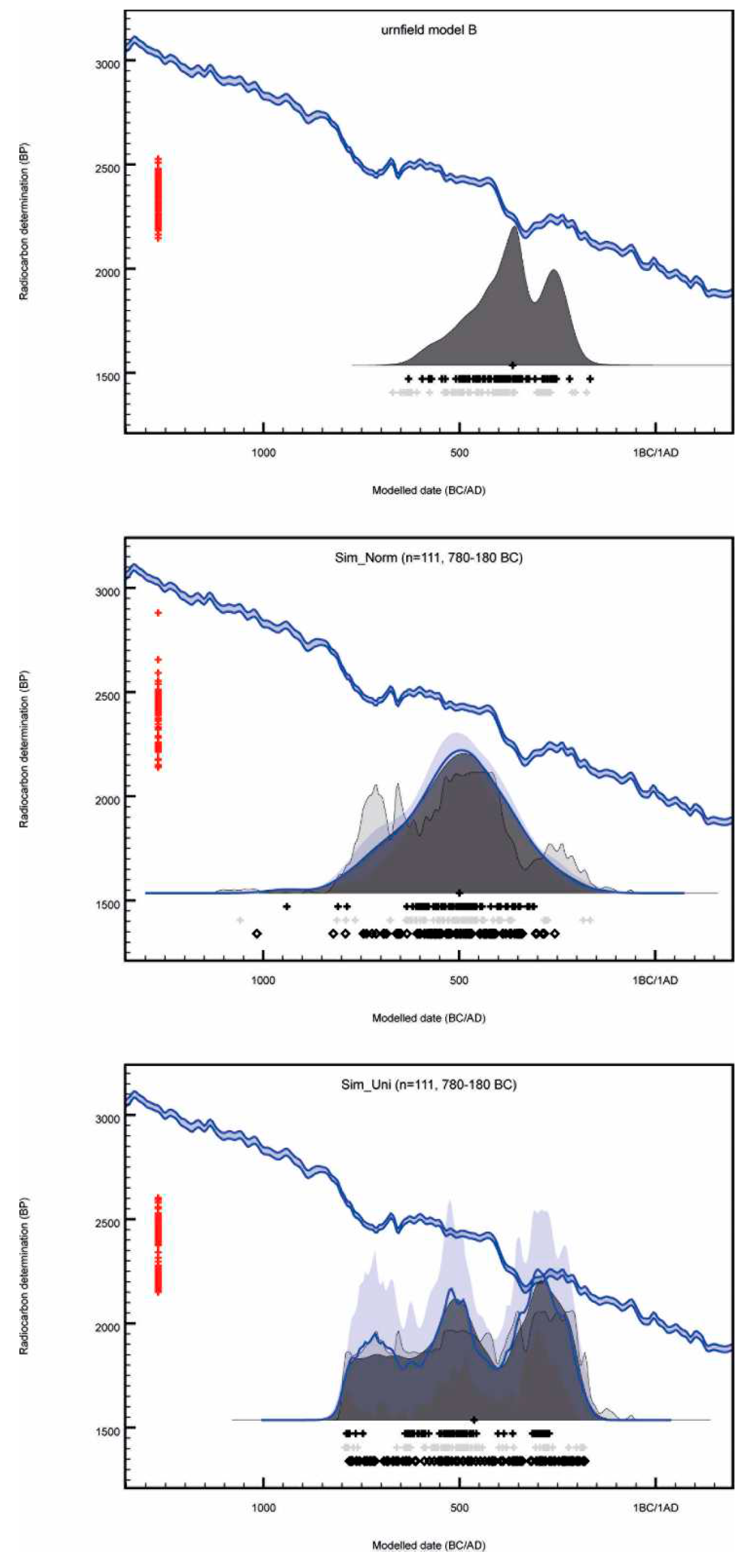

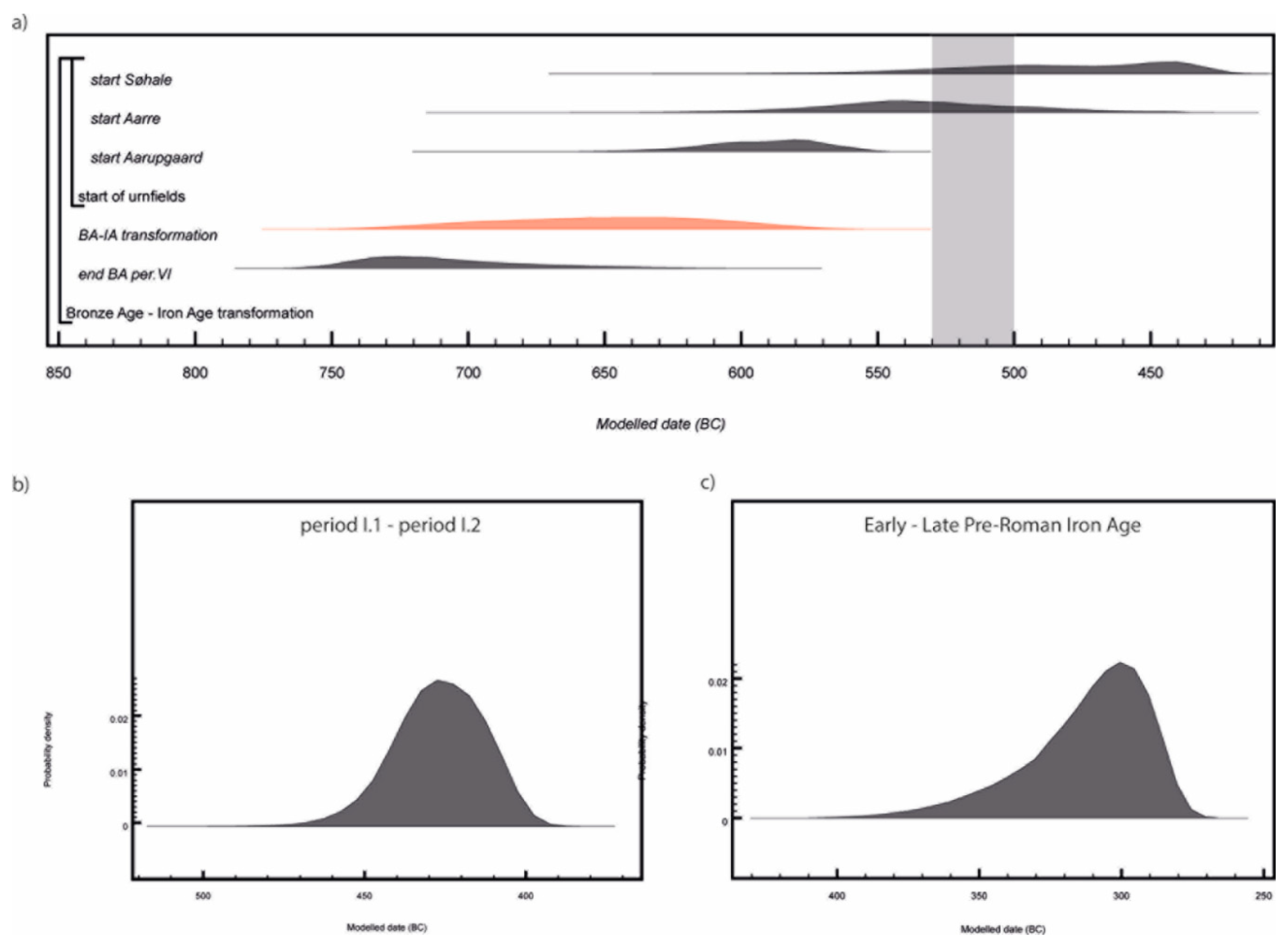

Modelling Burial Activity

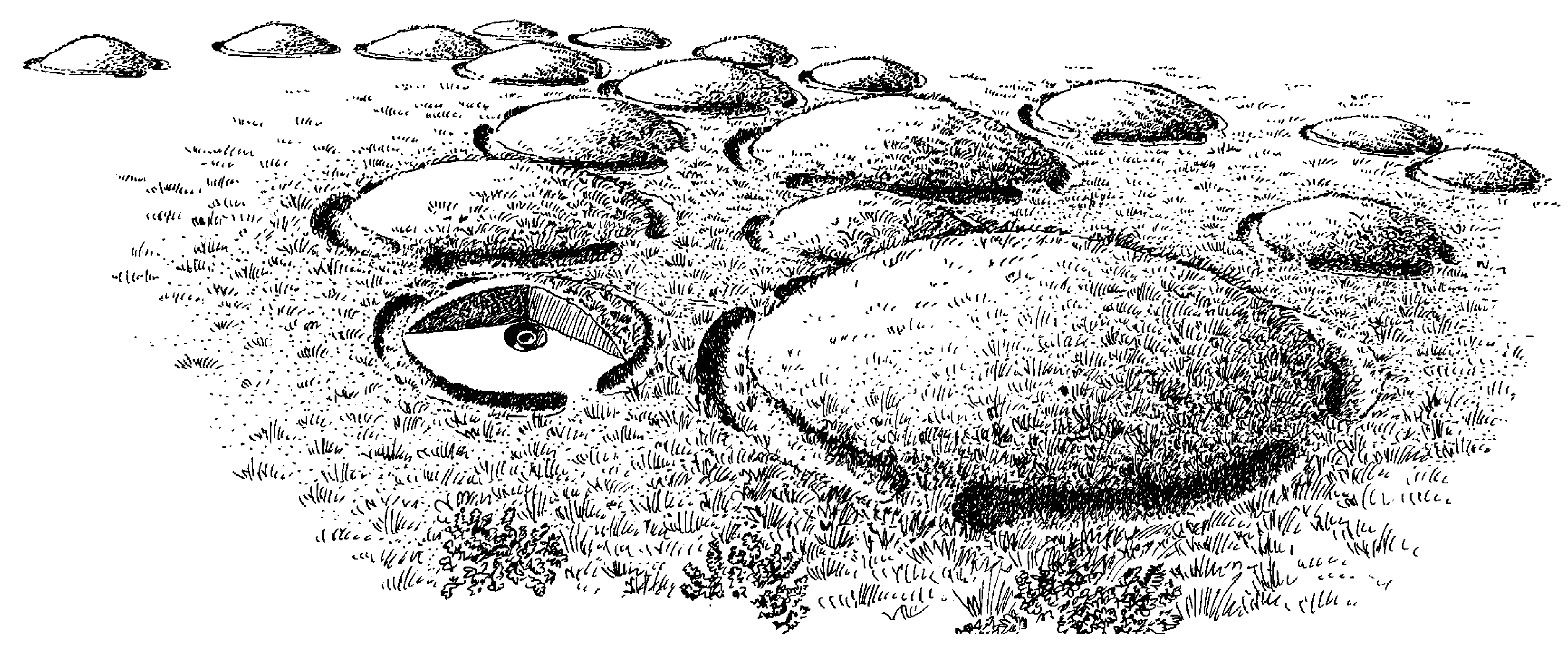

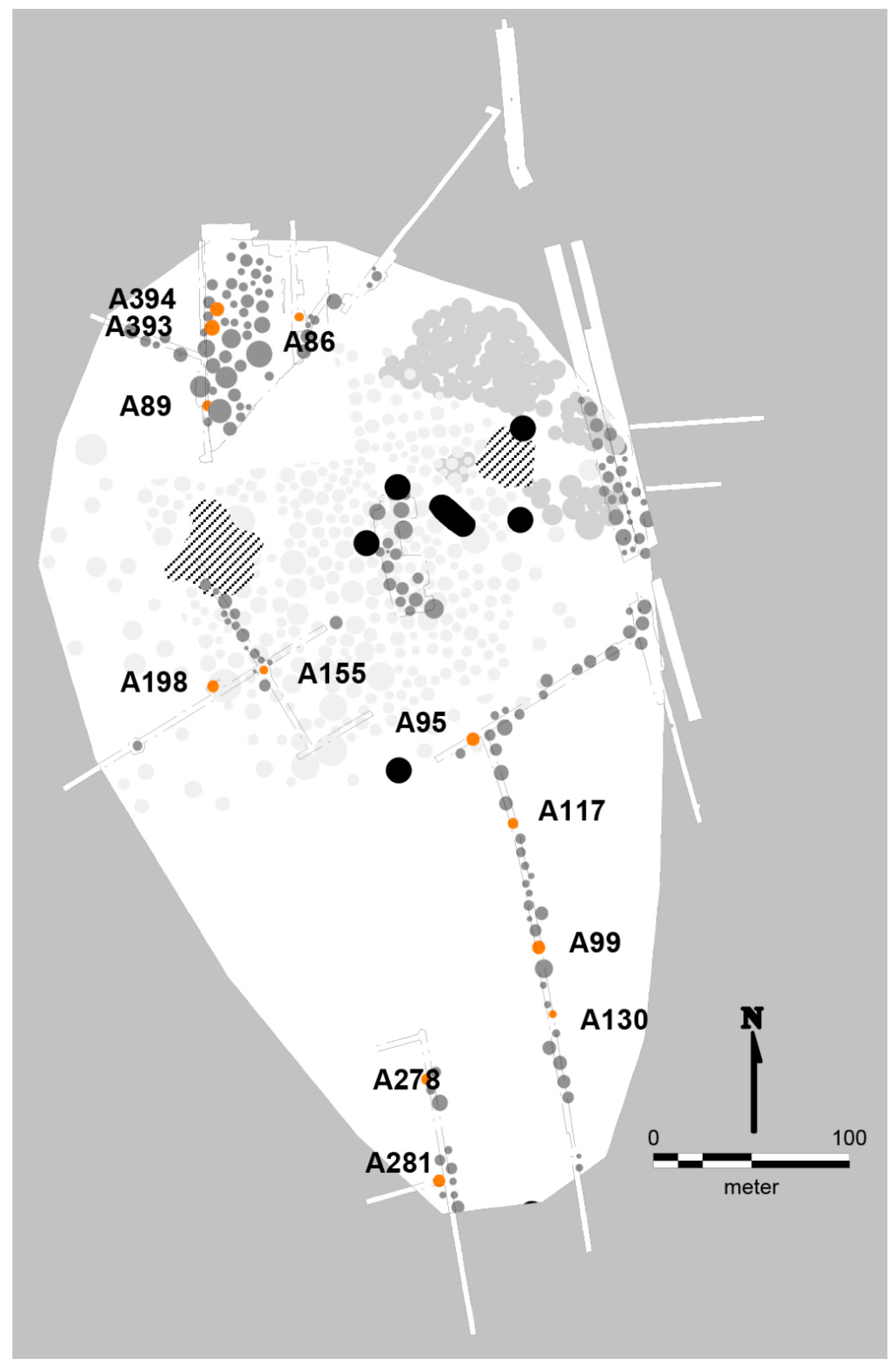

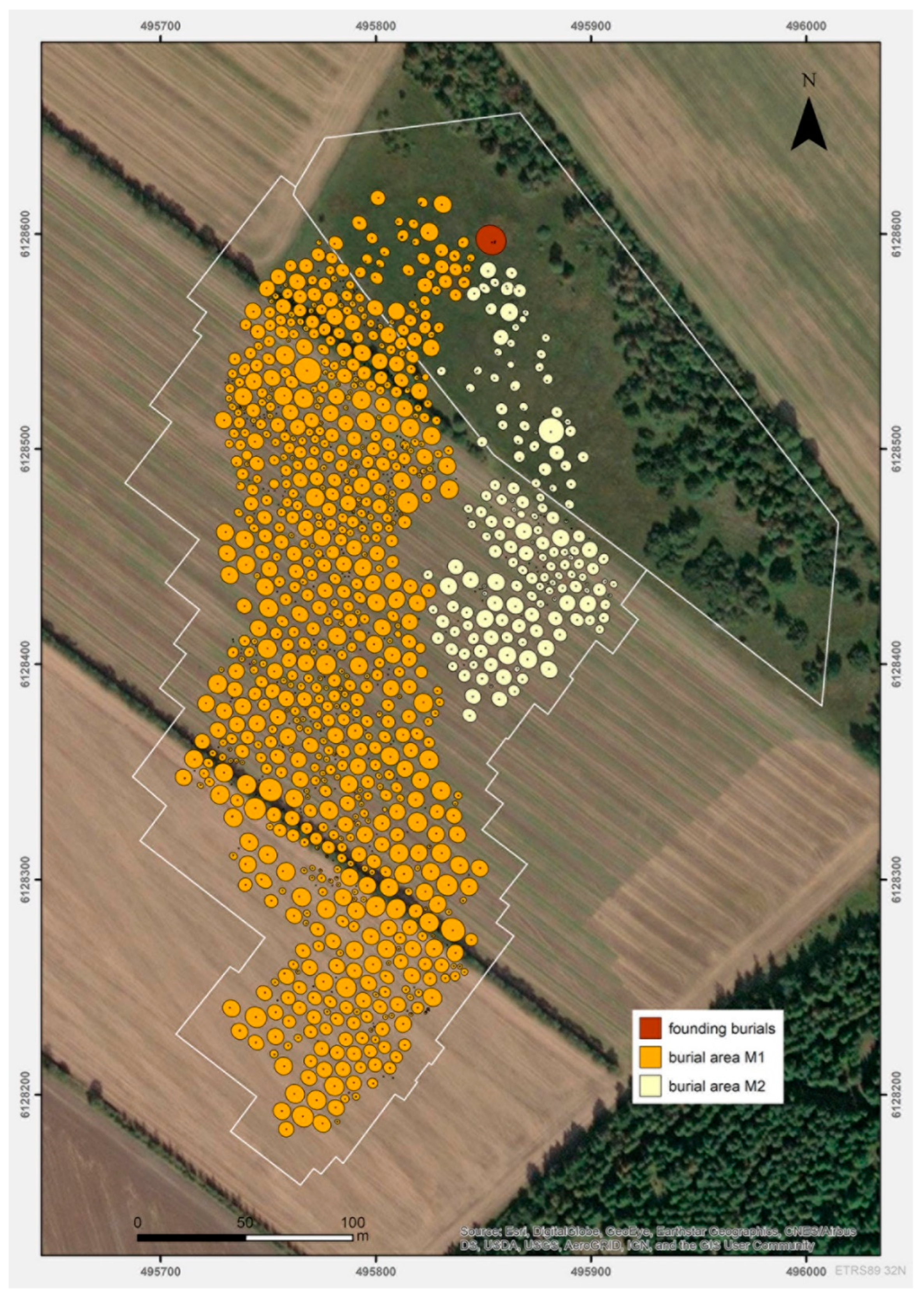

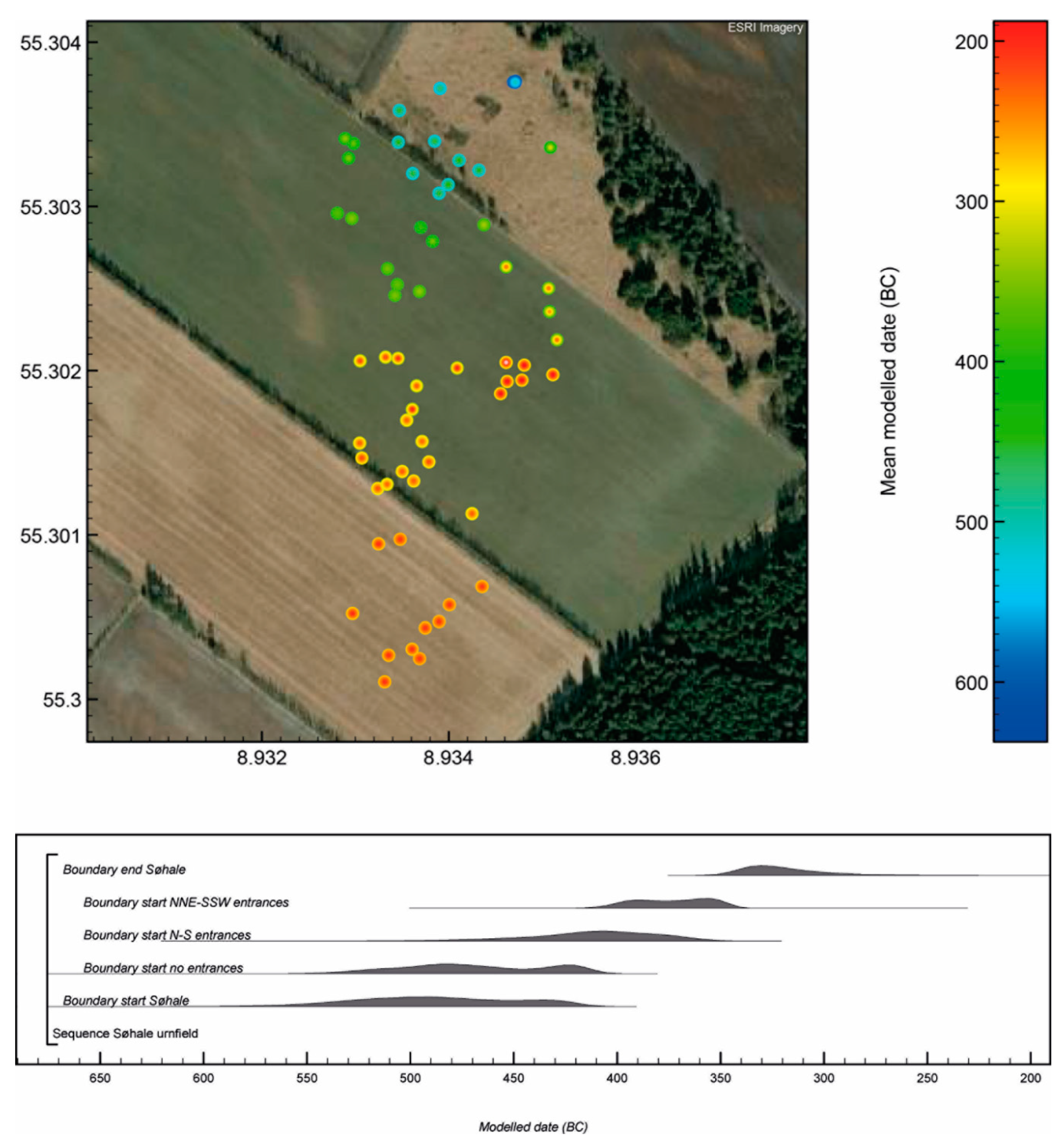

Spatio-Temporal Development

Sensitivity Testing

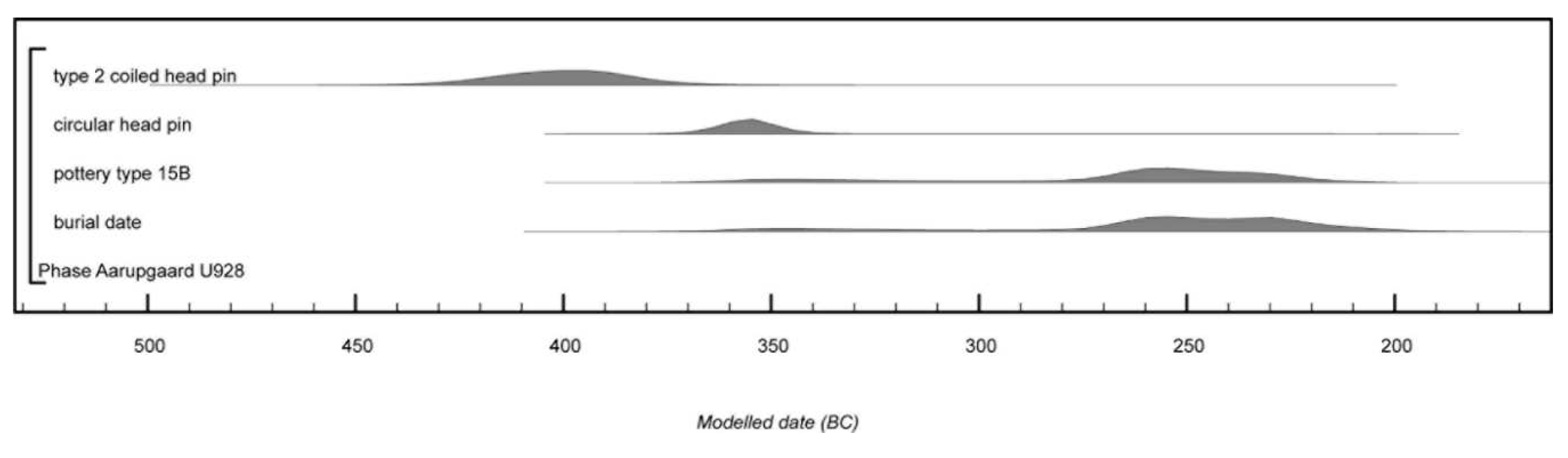

Modelling Artefact Currencies

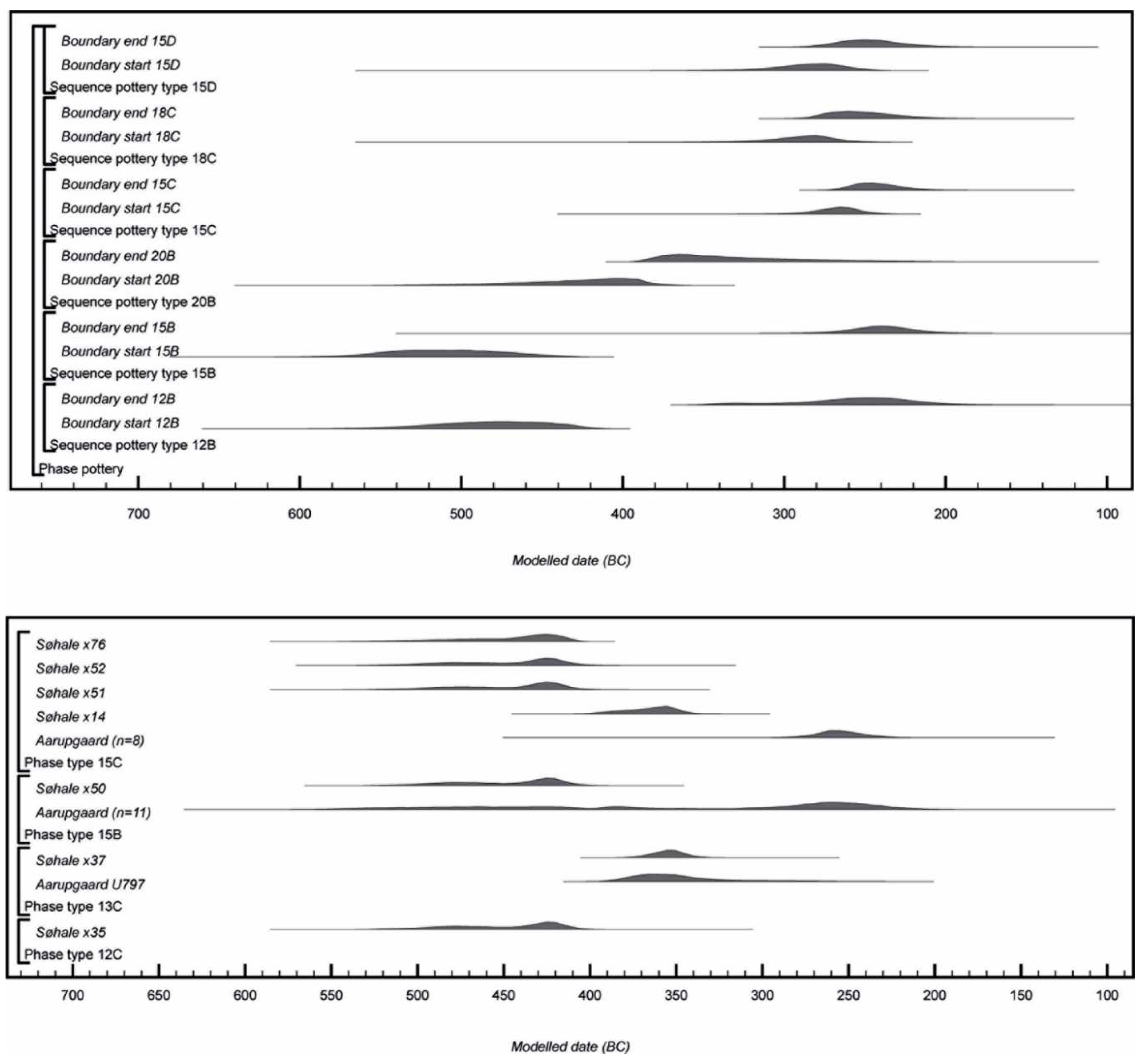

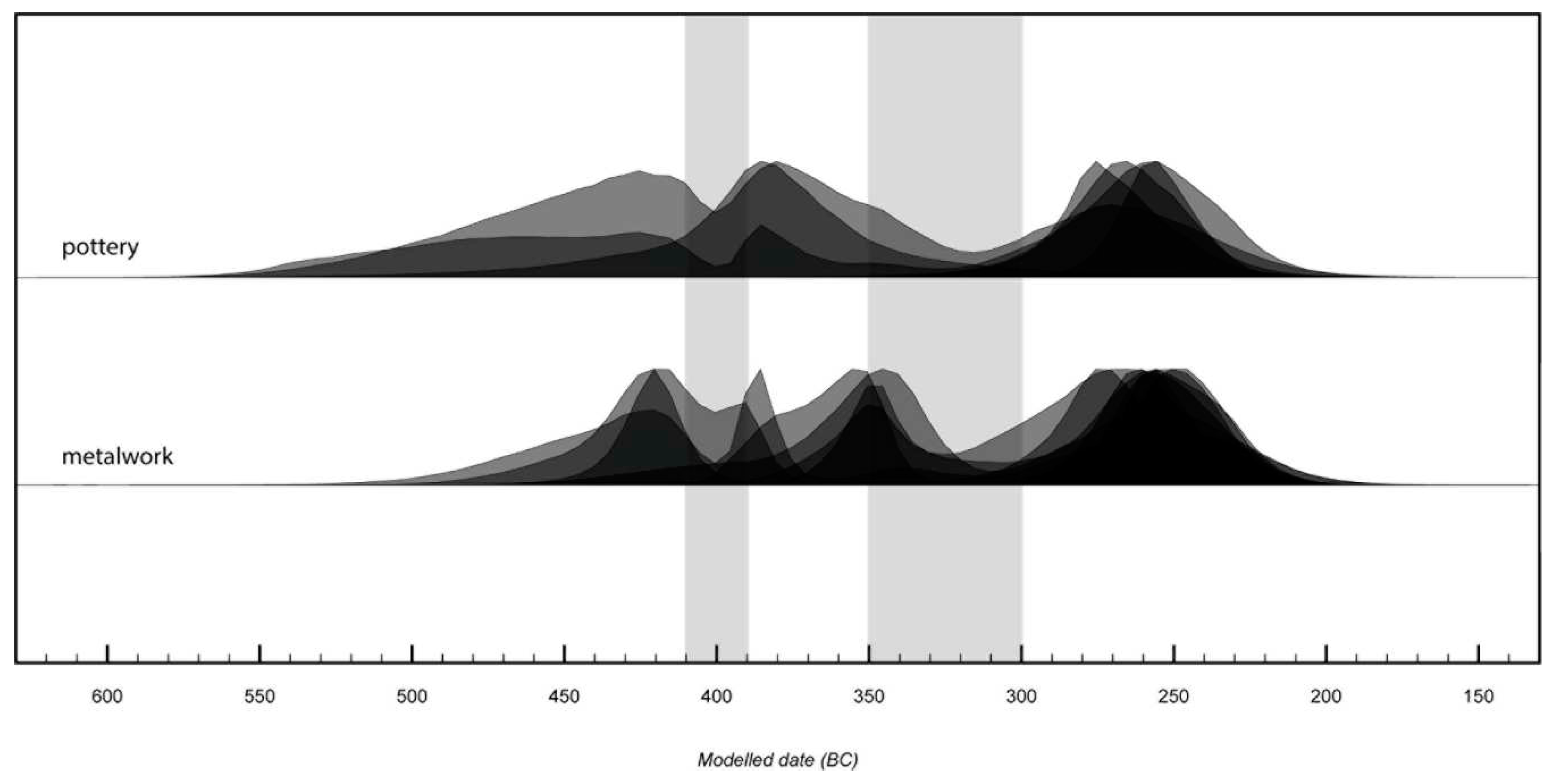

Pottery Currencies

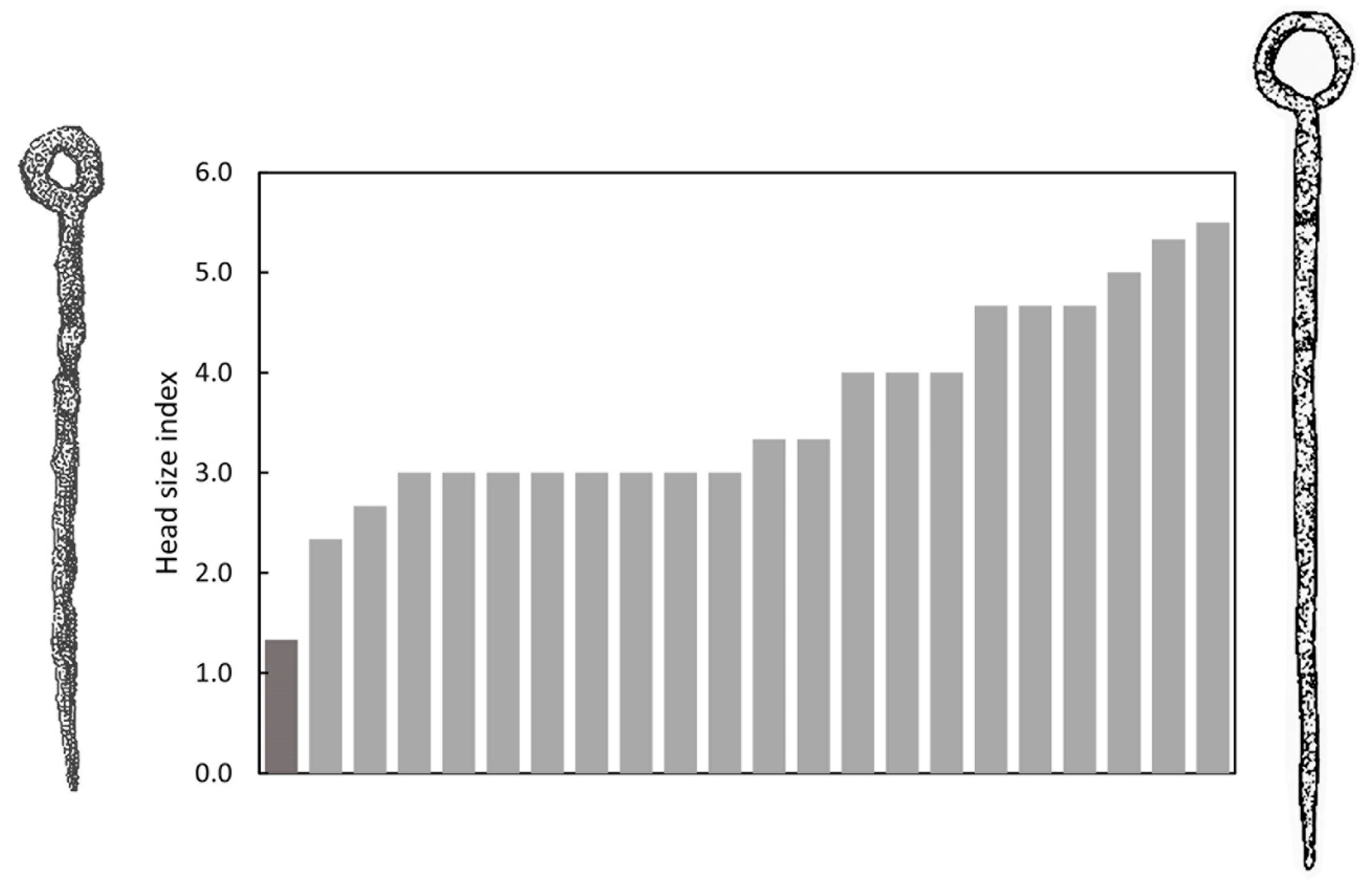

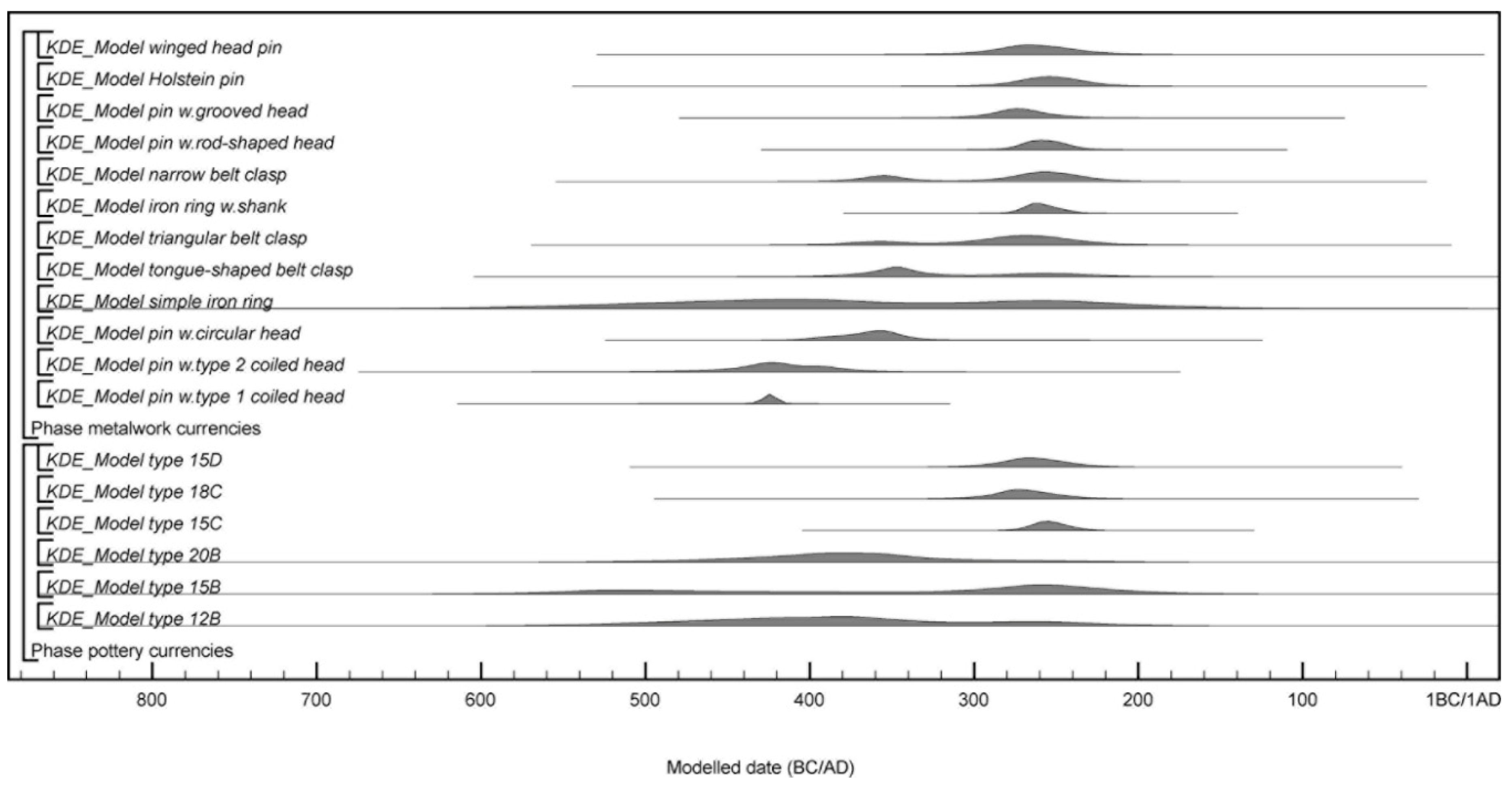

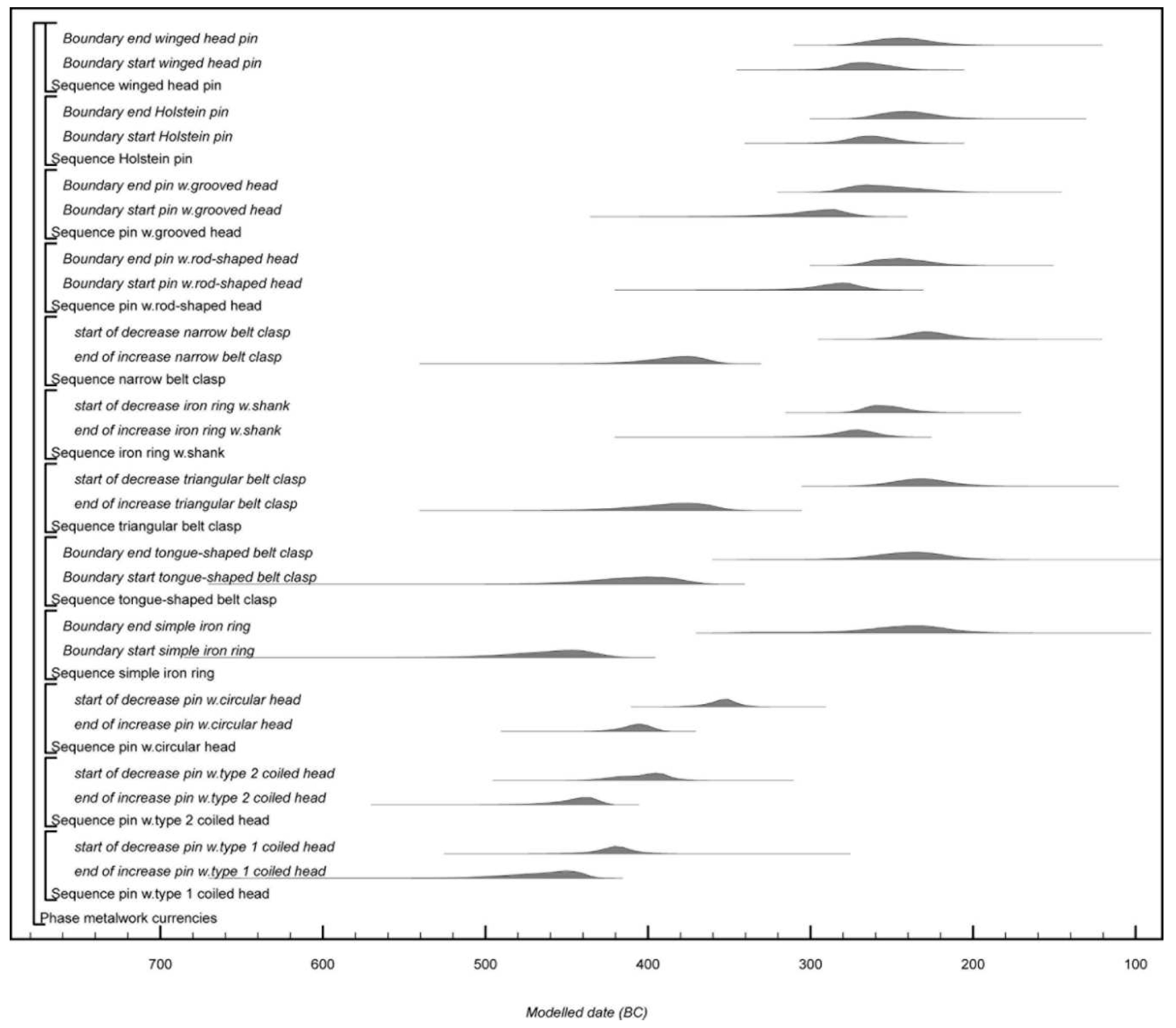

Metalwork Currencies

Discussion

Insight into a Dynamic Material Culture

Heirlooms and Residence Time

Absolute Chronology

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Thomsen, C.J. Ledetraad til Nordisk Oldkyndighed; Kongelige Nordiske oldskriftselskab: Kjöbenhavn, 1836. [Google Scholar]

- Gräslund, B. Periodsystem i forskningshistorisk perspektiv. Hikuin 1978, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Neergaard, C. Sønderjyllands Jærnalder Aarbøger for Nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie. 1916, 1916; 227–230. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, C.J. Førromersk jernalder i Syd- og Midtjylland; Nationalmuseet: København, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, C.K. Kontekstuel kronologi: en revision af det kronologiske grundlag for førromersk jernalder i Sydskandinavien; Kulturlaget: Højbjerg, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke, P. Brandgräber vom Beginn der Hallstattzeit aus den östlichen Alpenländern und die Chronologie des Grabfeldes von Hallstatt,‘Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft 30, Wien. 1900.

- Kossinna, G. Die Herkunft der Germanen: zur methode der Siedlungsarchäologie; Kabitzsch: 1911.

- Sørensen, M.L.S.; Rebay-Salisbury, K. The impact of 19th century ideas on the construction of ’urnfield’ as a chronological and cultural concept: tales from Northern and Central Europe. In Construire le temps. Histoire et méthodes des chronologies et calendriers des derniers millénaires avant notre ère en Europe occidentale. Actes du XXXe (Bibracte; 16). Colloque international de Halma-Ipel, UMR 8164 (CNRS, Lille 3, MCC), 7-9 décembre 2006, Lille; Lehoërff, A., Ed. 2008; pp. 57-67.

- Madsen, A.; Neergaard, C. Jydske gravpladser fra den førromerske jernalder. Aarbøger for Nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie 1894, 1894, 165–212. [Google Scholar]

- Neergaard, C. Jernalderen. Aarbøger for Nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie 1892, 207–341. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, C.K. Chronologische Probleme und ihre Bedeutung für das Verständnis der vorrömischen Eisenzeit in Süd-/Mitteljütland. Praehistorische Zeitschrift 1996, 71, 194–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.K. Om behovet for en nyvurdering af den førromerske kronologi. Lag 1992, 3, 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hingst, H. Vorgeschichte des Kreises Stormarn; Wachholtz: Neumünster, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J. The prehistory of Denmark: from the Stone Age to the Vikings; Gyldendal: Kbh, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J. Hallstattsværd i skandinaviske fund fra overgangen mellem bronze- og jernalderen. In Regionale forhold i Nordisk Bronzealder. 5. Nordiske Symposium for Bronzealderforskning på Sandbjerg Slot 1987., Poulsen, J., Ed. 1989; p. 149-157.

- Lorentzen, A.; Steffgen, U. Bemerkungen zu Leitformen der älteren vorrömischen Eisenzeit nördlich der Mittelgebirge. Germania 1990, 68, 483–508. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J. Ulbjerg-graven. Begyndelsen af den ældre jernalder i Jylland. Kuml 1966, 1965, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, N.A.; Harvig, L.L.; Grundvad, B. The Iron Age urnfield tradition of southwestern Jutland, Denmark. Acta Archaeologica 2020, 91, 11–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, M.G.L.; Pilcher, J.R. Some observations on the high-precision calibration of routine dates. In Archaeology, Dendrochronology and the Radiocarbon Calibration Curve, Ottaway, B.S., Ed. University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, 1983; pp. 51-63.

- Lanting, J.N.; Aerts-Bijma, A.T.; van der Plicht, J. Dating of Cremated Bones. Radiocarbon 2001, 43, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mulder, G.; Creemers, G.; Van Strydonck, M. Challenging the Traditional Chronological Framework of Funerary Rituals in the Meuse-Demer-Scheldt Region: 14C Results from the Site of Lummen-Meldert (Belgium). Radiocarbon 2014, 56, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüls, C.M.; Erlenkeuser, H.; Nadeau, M.J.; Grootes, P.M.; Andersen, N. Experimental Study on the Origin of Cremated Bone Apatite Carbon. Radiocarbon 2010, 52, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazzo, A.; Saliège, J.-F.; Lebon, M.; Lepetz, S.; Moreau, C. Radiocarbon Dating of Calcined Bones: Insights from Combustion Experiments Under Natural Conditions. Radiocarbon 2012, 54, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoeck, C.; Brock, F.; Schulting, R.J. Carbon Exchanges between Bone Apatite and Fuels during Cremation: Impact on Radiocarbon Dates. Radiocarbon 2014, 56, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, H.A.; Meadows, J.; Henriksen, M.B. Bayesian modeling of wood-age offsets in cremated bone. Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinman, G.M.; Neitzel, J.E. Excising culture history from contemporary archaeology. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 2020, 60, 101230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.W. A Study of Archaeology; 1948.

- Binford, L.R. Archaeological Systematics and the Study of Culture Process. American Antiquity 1965, 31, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S. We’re All Cultural Historians Now: Revolutions In Understanding Archaeological Theory And Scientific Dating. Radiocarbon 2017, 59, 1347–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D. Archaeology: the loss of innocence. Antiquity 1973, 47, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegmund, F. How many years should chronological units cover in archaeology? In Rural riches & royal rags? Studies on medieval and modern archaeology, presented to Frans Theuws, Kars, M., van Oosten, R., Roxburgh, M.A., Verhoeven, A., Eds. SPA-Uitgevers & the Dutch Society for Medieval Archaeology: Zwolle, 2018; pp. 96-104.

- Fowler, C. Relational Typologies, Assemblage Theory and Early Bronze Age Burials. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 2017, 27, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, M.L.S. ‘Paradigm lost’ – on the State of Typology within Archaeological Theory. In Paradigm Found. Archaeological Theory. Present, Past And Future, Kristiansen, K., Šmejda, L., Turek, J., Eds. Oxford, 2015; pp. 84-94.

- Normark, J. Involutions of Materiality: Operationalizing a Neo-materialist Perspective through the Causeways at Ichmul and Yo’okop. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 2010, 17, 132–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boozer, A.L. The tyranny of typologies: evidential reasoning in Romano-Egyptian domestic archaeology. In Material Evidence: Learning from archaeological practice, Chapman, R., Wylie, A., Eds. Routledge: London, 2015; pp. 92– 109.

- Gräslund, B. Relativ datering. Om kronologisk metod i nordisk arkeologi; 1974.

- Trachsel, M. Untersuchungen zur relativen and absoluten Chronologie der Hallstattzeit; R. Habelt: Bonn, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, C.K.; Høilund Nielsen, K. Burial & society: the chronological and social analysis of archaeological burial data; Aarhus University Press: Aarhus, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kneisel, J. New chronological research of the late Bronze Age in Scandinavia. Danish Journal of Archaeology 2013, 2, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, A.; Hines, J.; Høilund Nielsen, K.; McCormac, F.G.; Scull, C. Anglo-Saxon Graves and Grave Goods of the Sixth and Seventh Centuries AD: A Chronological Framework; Society for Medieval Archaeology: London, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parzinger, H. Chronologie der Späthallstatt- und Frühlatène-Zeit: Studien zu Fundgruppen zwischen Mosel und Save; VCH, Acta Humaniora: Weinheim, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, B.W.; Uckelmann, M.; Brandherm, D. Old Father Time: The Bronze Age Chronology of Western Europe. In The Oxford handbook of the European Bronze Age, Fokkens, H., Harding, A., Eds. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2013; pp. 17-46.

- Brainerd, G.W. The Place of Chronological Ordering in Archaeological Analysis. American Antiquity 1951, 16, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plog, S.; Hantman, J.L. Chronology Construction and the Study of Prehistoric Culture Change. Journal of Field Archaeology 1990, 17, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmer, M.P. Arkeologisk positivism. Fornvännen 1984, 79, 260–268. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, J.M. Mortuary variability: an archaeological investigation; Academic Press: Orlando, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, M.P. The archaeology of death and burial, 2003 ed.; Sutton Publishing: Phoenix Mill, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zavodny, E.; Culleton, B.J.; McClure, S.B.; Kennett, D.J.; Balen, J. Recalibrating grave-good chronologies: new AMS radiocarbon dates from Late Bronze Age burials in Lika, Croatia. Antiquity 2019, 93, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strien, H.-C. ‘Robust chronologies’ or ‘Bayesian illusion’? Some critical remarks on the use of chronological modelling. Documenta Praehistorica 2019, 46, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asscher, Y.; Boaretto, E. Absolute Time Ranges in the Plateau of the Late Bronze to Iron Age Transition and the Appearance of Bichrome Pottery in Canaan, Southern Levant. Radiocarbon 2019, 61, 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, C.E.; Cavanagh, W.G.; Litton, C.D. Bayesian approach to interpreting archaeological data; Wiley: Chichester, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss, A. Rolling Out Revolution: Using Radiocarbon Dating in Archaeology. Radiocarbon 2009, 51, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.D.; Krus, A.M. The myths and realities of Bayesian chronological modeling revealed. American Antiquity 2018, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronk Ramsey, C.; Schulting, R.J.; Bazaliiskii, V.I.; Goriunova, O.I.; Weber, A.W. Spatio-temporal patterns of cemetery use among Middle Holocene hunter-gatherers of Cis-Baikal, Eastern Siberia. Archaeological Research in Asia 2021, 25, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, G.W.; Pilcher, J.R.; Baillie, M.G.L. High-precision 14C measurement of Irish oaks to show the natural 14C variations from 200 BC to 4000 BC. Radiocarbon 1983, 25, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuiver, M.; Becker, B. High-precision decadal calibration of the radiocarbon time scale, AD 1950–2500 BC. Radiocarbon 1986, 28, 863–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijma, S.; Aerts, A.T.; van der Plicht, J.; Zondervan, A. The Groningen AMS facility. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 1996, 113, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stäuble, H.; Hiller, A. An Extended Prehistoric Well Field in the Opencast Mine Area of Zwenkau, Germany. Radiocarbon 1997, 40, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.D.; Haselgrove, C.; Gosden, C. The impact of Bayesian chronologies on the British Iron Age. World Archaeology 2015, 47, 642–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts-Bijma, A.T.; Paul, D.; Dee, M.W.; Palstra, S.W.L.; Meijer, H.A.J. An independent assessment of uncertainty for radiocarbon analysis with the new generation high-yield accelerator mass spectrometers. Radiocarbon 2020, 63, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, T.J.; Blaauw, M.; Blackwell, P.G.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Reimer, P.J.; Scott, E.M. The IntCal20 Approach to Radiocarbon Calibration Curve Construction: A New Methodology Using Bayesian Splines and Errors-in-Variables. Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 821–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrni, S.M.; Southon, J.; Fuller, B.T.; Park, J.; Friedrich, M.; Muscheler, R.; Wacker, L.; Taylor, R.E. Single-year German oak and Californian bristlecone pine 14C data at the beginning of the Hallstatt Plateau from 856 BC to 626 BC. Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 919–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Southon, J.; Fahrni, S.; Creasman, P.P.; Mewaldt, R. Relationship between solar activity and Δ14C peaks in AD 775, AD 994, and 660 BC. Radiocarbon 2017, 59, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 64. Reimer, P.J.; Austin, W.E.N.; Bard, E.; Bayliss, A.; Blackwell, P.G.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Butzin, M.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Friedrich, M.; et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curve (0-55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 725–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddington, K.; Bayliss, A.; Higham, T.; Madgwick, R.; Sharples, N. Histories of deposition: creating chronologies for the Late Bronze Age-Early Iron Age transition in Southern Britain. Archaeological Journal 2019, 176, 84–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, H.A.; Müller-Scheeßel, N.; Meadows, J.; Hamann, C. Radiocarbon dating and Hallstatt chronology: a Bayesian chronological model for the burial sequence at Dietfurt an der Altmühl ‘Tennisplatz’, Bavaria, Germany. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 2022, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsson, P.; Hamilton, W.D.; Cook, G.; Crone, A.; Dunbar, E.; Kinch, H.; Naysmith, P.; Tripney, B.; Xu, S. Refining the Hallstatt Plateau: Short-Term 14C Variability and Small Scale Offsets in 50 Consecutive Single Tree-Rings from Southwest Scotland Dendro-Dated to 510–460 BC. Radiocarbon 2018, 60, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, S.W.; Smith, A.T.; Khatchadourian, L.; Badalyan, R.; Lindsay, I.; Greene, A.; Marshall, M. A new chronological model for the Bronze and Iron Age South Caucasus: radiocarbon results from Project ArAGATS, Armenia. Antiquity 2018, 92, 1530–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, J.; Rinne, C.; Immel, A.; Fuchs, K.; Krause-Kyora, B.; Drummer, C. High-precision Bayesian chronological modeling on a calibration plateau: The Niedertiefenbach gallery grave. Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 1261–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, E. Tuernes Mysterier. Skalk 1975, 1975, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss, A.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; van der Plicht, J.; Whittle, A. Bradshaw and Bayes: Towards a Timetable for the Neolithic. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 2007, 17, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deetz, J.; Dethlefsen, E. The Doppler Effect and Archaeology: A Consideration of the Spatial Aspects of Seriation. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 1965, 21, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, R.L.; Harpole, J.L.A. L. Kroeber and the Measurement of Time’s Arrow and Time’s Cycle. Journal of Anthropological Research 2002, 58, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, C.E.; Litton, C.D.; Smith, A.F.M. Calibration of radiocarbon results pertaining to related archaeological events. Journal of Archaeological Science 1992, 19, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsberg, A.J. Flexible Bayesian methods for archaeological dating. Doctoral thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, 2006.

- Lee, S.; Bronk Ramsey, C. Development and Application of the Trapezoidal Model for Archaeological Chronologies. Radiocarbon 2012, 54, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronk Ramsey, C. Bayesian Analysis of Radiocarbon Dates. Radiocarbon 2009, 51, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Mazar, A. Iron Age Chronology in Israel: Results from Modeling with a Trapezoidal Bayesian Framework. Radiocarbon 2013, 55, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S.; Johnston, R.; May, R.; McOmish, D.; Marshall, P.; Last, J.; Bayliss, A. Dividing the Land: Time and Land Division in the English North Midlands and Yorkshire. European Journal of Archaeology 2022, 25, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, J. Jastorf and Jutland. In Proceedings of Internationalen Tagung zum einhundertjähringen Jubiläum der Veröffentlichung der "Ältesten Urnenfriedhöfe bei Uelzen und Lüneburg" duch Gustav Schwantes, Bad Bevensen; pp. 245-266.

- Fokkens, H. The genesis of urnfields: economic crisis or ideological change? Antiquity 1997, 71, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beek, R.; Quik, C.; Bergerbrant, S.; Huisman, F.; Kama, P. Bogs, bones and bodies: the deposition of human remains in northern European mires (9000 BC–AD 1900). Antiquity 2023, 97, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkildsen, K.F. Gravpladsen Årupgård som kilde til social stratifikation i førromersk jernalder. In Proceedings of the De dødes landskab. Grav og gravskik i ældre jernalder i Danmark, Ribe; pp. 51–70.

- Løvschal, M. Emerging Boundaries: Social Embedment of Landscape and Settlement Divisions in Northwestern Europe during the First Millennium BC. Current Anthropology 2014, 55, 725–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, P.; Rindel, P.O. Hulbælternes funktioner. In Lange linjer i landskabet. Hulbælter fra jernalderen, Eriksen, P., Rindel, P.O., Eds. Jysk Arkæologisk Selskab: Højbjerg, 2018; pp. 409-428.

- Martens, J. Fortified places in low-land Northern Europe and Scandinavia during the Pre-Roman Iron Age. In Keltische Einflüsse im nördlichen Mitteleuropa während der mittleren und jüngeren vorrömischen Eisenzeit, Mollers, S., Schlüter, W., Sievers, S., Eds. Habelt: Bonn, 2007; pp. 87-105.

- Neergaard, C. Nogle sønderjydske Fund fra den ældre jernalder. Fra Nationalmuseets Arbejdsmark 1931, 1931, 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, H. Tuegravpladsen på Årupgårds mark, Gram sogn. Haderslev Amts Museum 1947, 1947, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Olesen, L.H.; Schlosser Mauritsen, E. Fortiden Set fra Himlen. Luftfotoarkæologi i Danmark; Holstebro Museum: Holstebro, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kolstrup, E. Vegetational and environmental history during the Holocene in the Esbjerg area, west Jutland, Denmark. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 2009, 18, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, N.A. Døde i de levendes verden. Vestjyske gravfund i kontekst. In Proceedings of the De dødes landskab. Grav og gravskik i ældre jernalder i Danmark, Ribe; pp. 215–236.

- Henriksen, M.B. Experimental cremations – can they help us to understand prehistoric cremation graves? In Interacting Barbarians Contacts, Exchange and Migrations in the First Millennium AD, Cieśliński, A., Kontny, B., Eds. Neue Studien zur Sachsenforschung Band 9: Warschau, 2019; pp. 289-296.

- Harvig, L.; Runge, M.T.; Lundø, M.B. Typology and function of Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age cremation graves - a micro-regional case study. Danish Journal of Archaeology 2014, 3, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, E. Berigtigelse. Skalk 1999, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, J. Die vorrömische Eisenzeit in Südskandinavien. Probleme und Perspektiven. Praehistorische Zeitschrift 1996, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingst, H. Neumünster-Oberjörn. Ein Urnenfriedhof der vorrömischen Eisenzeit am Oberjörn und die vor- and frühgeschichtliche Besiedlung auf dem Neumünsteraner Sander; Wachholtz: Neumünster, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hingst, H. Urnenfriedhöfe der vorrömischen Eisenzeit aus dem östlichen Holstein und Schwansen; Wachholtz: Neumünster, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hingst, H. Jevenstedt. Ein Urnenfriedhof der älteren vorrömischen Eisenzeit im Kreise Rendsburg-Eckernförde, Holstein; Wachholtz: Neumünster, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hingst, H. Die vorrömische Eisenzeit Westholsteins; Wachholtz: Neumünster, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hingst, H. Urnenfriedhöfe der vorrömischen Eisenzeit aus Südholstein; Wachholtz: Neumünster, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lorange, T. Det sakrale landskab ved Årre. Landskabets hukommelse gennem 4.000 års gravriter. In De dødes landskab. Grav og gravskik i ældre jernalder i Danmark, Foss, P., Møller, N.A., Eds. SAXO-instituttet, Københavns Universitet: Ribe, 2015; pp. 21-36.

- Guy, H.; Masset, C.; Baud, C.-A. Infant taphonomy. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 1997, 7, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, J. Investigations on Pre-Roman and Roman Cremation Remains. In The Analysis of Burned Human Remains, Second ed.; Schmidt, C.W., Symes, S.A., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2015; pp. 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz Paulsson, B. Radiocarbon dates and Bayesian modeling support maritime diffusion model for megaliths in Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 3460–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayliss, A.; Allen, M.J.; Healy, F.; Whittle, A.; Germany, M.; Griffiths, S.; Hamilton, D.; Higham, T.; Meadows, J.; Shand, G.; et al. The Greater Thames estuary. In Gathering Time: Dating the Early Neolithic Enclosures of Southern Britain and Ireland, Whittle, A., Healy, F., Bayliss, A., Eds. Oxbow: Oxford, 2011; pp. 348-386. [CrossRef]

- Dye, T.S.; Buck, C.E.; DiNapoli, R.J.; Philippe, A. Bayesian chronology construction and substance time. Journal of Archaeological Science 2023, 153, 105765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvig, L.; Lynnerup, N.; Ebsen, J.A. Computed tomography and computed radiography of Late Bronze Age cremation urns from Denmark: an interdisciplinary attempt to develop methods applied in bioarchaeological cremation research. Archaeometry 2012, 54, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Person, A.; Bocherens, H.; Saliège, J.-F.; Paris, F.; Zeitoun, V.; Gérard, M. Early Diagenetic Evolution of Bone Phosphate: An X-ray Diffractometry Analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science 1995, 22, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.; Heinemeier, J.; Bennike, P.; Krause, C.; Margrethe Hornstrup, K.; Thrane, H. Characterisation and blind testing of radiocarbon dating of cremated bone. Journal of Archaeological Science 2008, 35, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, H.A.; Meadows, J.; Palstra, S.W.L.; Hamann, C.; Boudin, M.; Huels, M. Radiocarbon Dating Cremated Bone: A Case Study Comparing Laboratory Methods. Radiocarbon 2019, 61, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Strydonck, M.; Boudin, M.; De Mulder, G. 14C Dating of Cremated Bones: The Issue of Sample Contamination. Radiocarbon 2009, 51, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mulder, G.; Van Strydonck, M.; Boudin, M.; Leclercq, W.; Paridaens, N.; Warmenbol, E. Re-Evaluation of the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Chronology of the Western Belgian Urnfields Based on 14C Dating of Cremated Bones. Radiocarbon 2007, 49, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dee, M.W.; Palstra, S.W.L.; Aerts-Bijma, A.T.; Bleeker, M.O.; de Bruijn, S.; Ghebru, F.; Jansen, H.G.; Kuitems, M.; Paul, D.; Richie, R.R.; et al. Radiocarbon dating at Groningen: New and updated chemical pretreatment procedures. Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudin, M.; Van Strydonck, M.; van den Brande, T.; Synal, H.-A.; Wacker, L. RICH – A new AMS facility at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, Brussels, Belgium. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 2015, 361, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, M.-J.; Schleicher, M.; Grootes, P.; Erlenkeuser, H.; Gottdang, A.; Mous, D.; Sarnthein, J.; Willkomm, H. The Leibniz-Labor AMS facility at the Christian-Albrechts University, Kiel, Germany. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 1997, 123, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuiver, M.; Polach, H.A. Discussion Reporting of 14C Data. Radiocarbon 1977, 19, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, G.K.; Wilson, S.R. Procedures for comparing and combining radiocarbon age determinations: a critique. Archaeometry 1978, 20, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaux, C.; Veselka, B.; Capuzzo, G.; Snoeck, C.; Sengeløv, A.; Hlad, M.; Warmenbol, E.; Stamataki, E.; Boudin, M.; Annaert, R.; et al. Multi-proxy analyses reveal regional cremation practices and social status at the Late Bronze Age site of Herstal, Belgium. Journal of archaeological science 2021, 132, 105437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naysmith, P.; Scott, E.M.; Cook, G.T.; Heinemeier, J.; Van der Plicht, J.; Van Strydonck, M.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Grootes, P.M.; Freeman, S.P.H.T. A Cremated Bone Intercomparison Study. Radiocarbon 2007, 49, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Strydonck, M.; Boudin, M.; Mulder, G.D. The Carbon Origin of Structural Carbonate in Bone Apatite of Cremated Bones. Radiocarbon 2010, 52, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronk Ramsey, C. Dealing with Outliers and Offsets in Radiocarbon Dating. Radiocarbon 2009, 51, 1023–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dee, M.W.; Bronk Ramsey, C. High-precision Bayesian modeling of samples susceptible to inbuilt age. Radiocarbon 2014, 56, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.; Margrethe Hornstrup, K.; Heinemeier, J.; Bennike, P.; Thrane, H. Chronology of the Danish Bronze Age Based on 14C Dating of Cremated Bone Remains. Radiocarbon 2011, 53, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronk Ramsey, C. Methods for summarizing radiocarbon datasets. Radiocarbon 2017, 59, 1809–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, D.A.; Meadows, J. Summed radiocarbon calibrations as a population proxy: a critical evaluation using a realistic simulation approach. Journal of Archaeological Science 2014, 52, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, M.; von Felten, J.; Hinz, M.; Hafner, A. Central European Early Bronze Age chronology revisited: A Bayesian examination of large-scale radiocarbon dating. PLOS ONE 2021, 15, e0243719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, S.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Coombs, D.; Cartwright, C.; Pettitt, P. An Independent Chronology for British Bronze Age Metalwork: The Results of the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Programme. Archaeological Journal 1997, 154, 55–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrow, D.; Gosden, C.; Hill, J.D.; Bronk Ramsey, C. Dating Celtic Art: a Major Radiocarbon Dating Programme of Iron Age and Early Roman Metalwork in Britain. Archaeological Journal 2009, 166, 79–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, A.; Bayliss, A.; Barclay, A.; Gaydasrka, B.; Bánffy, E.; Borić, D.; Draşovean, F.D.; Jakucs, J.; Marić, M.; Orton, D.; et al. A Vinča potscape: formal chronological models for the use and development of Vinča ceramics in south-east Europe. Documenta Praehistorica 2016, 43, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, Z.; Jungbert, B.; Morgós, A.; Molnár, M.; Horváth, E. Wiggle-match dating of a floating oak chronology from an Early Iron Age grave construction (Eresztvényi Forest, Fehérvárcsurgó, Hungary). Radiocarbon 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandkilde, H.; Rahbek, U.; Rasmussen, K.L. Radiocarbon dating and the chronology of Bronze Age Southern Scandinavia. Acta Archaeologica 1996, 67, 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J. Fra Bronze - til Jernalder. En kronologisk undersøgelse; Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab: København, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rieckhoff, S.; Biel, J. Die Kelten in Deutschland; Konrad Theiss Verlag: Stuttgart, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeager, L. Danmarks jernalder: mellem stamme og stat. Doctoral dissertation, Aarhus University Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 1990.

- Schmidt, J.-P. Studien zur jüngeren Bronzezeit in Schleswig-Holstein und dem nordelbischen Hamburg; Habelt: Bonn, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kneisel, J.; Dörfler, W.; Dreibrodt, S.; Schaefer-Di Maida, S.; Feeser, I. Cultural change and population dynamics during the Bronze Age: Integrating archaeological and palaeoenvironmental evidence for Schleswig-Holstein, Northern Germany. The Holocene 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingst, H. Grabhügelfelder der jüngeren Bronze- und der frühen Eisenzeit aus Schleswig-Holstein. Offa 1976, 33, 66–122. [Google Scholar]

- Webley, L. Iron Age households: structure and practice in Western Denmark, 500 BC-AD 200; Jutland Archaeological Society: Højbjerg, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer-Di Maida, S. Bronzezeitliche Transformationsprozesse in Schleswig-Holstein am Beispiel vom Fundplatz von Mang de Bargen, Bornhöved (Kr. Segeberg). Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Kiel, 2020.

- Louwen, A.J. Breaking and Making the Ancestors. Piecing together the urnfield mortuary process in the Lower-Rhine-Basin, ca. 1300 - 400 BC; Sidestone Press: Leiden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- De Mulder, G.; Van Strydonck, M.; Boudin, M. The Impact of Cremated Bone Dating on the Archaeological Chronology of the Low Countries. Radiocarbon 2009, 51, 579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lab code | Sample ID | Material | Diagnostic artefacts | Entrances / burial group | CI | %C of extract | Corrected pMC | AMS δ13C(‰VPDB)1 | 14C Age (BP) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aarupgaard urnfield cemetery (HAM 1070) | |||||||||||

| KIA-51892 | U34x34-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 20B, 2 pins with type 2 coiled heads | >2 entrances, M1_CC2, | 6.4 | 0.24 | 74.68 ± 0.26 | -24.4 | 2346 ± 28 | ||

| KIA-51893 | U36x36-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 20B, 2 pins with type 2 coiled heads | >2 entrances,M1_CC2 | 5.9 | 0.23 | 73.81 ± 0.19 | -24.6 | 2439 ± 21 | ||

| GrM-15072 | U51x51-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15B, 2 pins with coiled heads and incomplete neck bends | >2 entrances,M1_CC1 | 5.9 | 0.11 | 73.77 ± 0.26 | -30.3 ± 0.4 | 2445 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52339 | U51x51-1 | Cremated bone (human) | - | - | - | 0.38 | 73.73 ± 0.24 | -26.8 ± 0.3 | 2448 ± 26 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U51x51-1: T’ = 0.0, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2446 ± 16 BP | |||||||||||

| GrM-14589 | U81x81-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 12B, 2 pins with type 2 coiled heads, iron chain corroded together with pins | >2 entrances,M1_CC1 | 5.9 | 0.06 | 73.93 ± 0.20 | -27.5 | 2425 ± 30 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52819 | U81x81-81 | Replicate of GrM-14589; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.19 | 74.37 ± 0.20 | -23.0 | 2379 ± 22 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U81x81-81: T’ = 1.5, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2395 ± 18 BP | |||||||||||

| GrM-15078 | U83x83-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 12B, 2 pins with type 2 coiled heads, pin of unknown type | >2 entrances,M1_CC1 | 6.0 | 0.06 | 73.42 ± 0.30 | -28.1 | 2485 ± 30 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52825 | U83x83-1 | Replicate of GrM-15078; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.17 | 74.09 ± 0.25 | -20.7 | 2409 ± 27 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U83x83-1: T’ = 3.5, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2443 ± 21 BP | |||||||||||

| KIA-51894 | U123x123-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 20B, triangular belt clasp, pin with circular head | >2 entrances,M1_CC2 | 6.4 | 0.29 | 75.32 ± 0.25 | -22.6 | 2277 ± 26 | ||

| KIA-51895 | U183x183-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 12B, tongue-shaped belt clasp, 2 pins with circular heads | 2 entrances, M2_CC1-3 | 6.6 | 0.21 | 75.64 ± 0.21 | -23.4 | 2243 ± 23 | ||

| GrM-14704 | U230x230-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 12B, 2 pins with circular heads | >2 entrances,M1_CC2 | 5.4 | 0.07 | 72.83 ± 0.12 | -21.7 | 2546 ± 19 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52826 | U230x230-1 | Replicate of GrM-14704; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.19 | 74.53 ± 0.23 | -20.9 | 2362 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U230x230-1: T’ = 34.1, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2480 ± 16 BP | |||||||||||

| GrM-14588 | U280x280-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15B, 2 pins with type 2 coiled heads | >2 entrances,M1_CC2 | 6.2 | 0.08 | 74.12 ± 0.14 | -25.1 | 2405 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52820 | U280x280-1 | Replicate of GrM-14588; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.27 | 74.16 ± 0.21 | -22.7 | 2402 ± 22 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U280x280-1: T’ = 0.0, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2404 ± 15 BP | |||||||||||

| KIA-51896 | U293x293-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 20B, 3 pins with circular heads | >2 entrances,M1_CC2 | 6.9 | 0.22 | 74.38 ± 0.21 | -22.8 | 2378 ± 23 | ||

| KIA-51897 | U346x346-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15C, tongue-shaped belt clasp | 2 entrances, M2_CC1-3 | 6.3 | 0.18 | 75.61 ± 0.22 | -21.9 | 2246 ± 24 | ||

| GrM-14596 | U382x382-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15C, narrow belt clasp | 2 entrances, M2_CC1-3 | 7.3 | 0.08 | 75.29 ± 0.14 | -24.8 ± 0.2 | 2280 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52827 | U382x382-1 | Replicate of GrM-14596; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.27 | 75.77 ± 0.24 | -22.5 ± 0.3 | 2229 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U382x382-1: T’ = 2.5, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2260 ± 16 BP | |||||||||||

| KIA-55388 | U427x427-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Holstein pin, triangular belt clasp, tweezer | 2 entrances, M2_CC1-3 | 6.2 | 0.26 | 75.66 ± 0.22 | -21.0 | 2241 ± 17 | ||

| KIA-51898 | U500x500-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 12B, 3 pins with circular heads | >2 entrances,M1_CC3 | 7.6 | 0.21 | 75.30 ± 0.21 | -26.7 | 2278 ± 23 | ||

| GrM-14705 | U681x681-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 13D, 2 pins with type 2 coiled heads, simple iron ring | >2 entrances,M1_CC3 | 6.0 | 0.08 | 75.01 ± 0.12 | -22.3 | 2310 ± 19 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-53094 | U681x681-1 | Replicate of GrM-14705; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.24 | 75.05 ± 0.19 | -22.5 | 2305 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U681x681-1: T’ = 0.0, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2308 ± 14 BP | |||||||||||

| RICH-25343 | U752x752-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 12B, 2 pins with circular heads | >2 entrances,M1_CC3 | 5.7 | 0.28 | 74.94 | -24.2 | 2317 ± 26 | ||

| GrM-14589 | U766x766-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15B, 3 pins with circular heads | >2 entrances,M1_CC3 | 5.5 | 0.16 | 75.24 ± 0.14 | -26.4 | 2285 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52821 | U766x766-1 | Replicate of GrM-14589; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.39 | 75.55 ± 0.21 | -25.2 | 2252 ± 23 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U766x766-1: T’ = 1.2, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2271 ± 16 BP | |||||||||||

| RICH-24151 | U797x797-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 13C, 2 pins with circular heads, narrow belt clasp | >2 entrances,M1_CC3 | 6.7 | 0.03 | 75.53 | -27.9 | 2255 ± 28 | ||

| KIA-51899 | U858x858-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15B, pin with rod-shaped head, narrow belt clasp | 2 entrances, M2_CC4 | 6.2 | 0.41 | 75.49 ± 0.21 | -21.5 | 2258 ± 23 | ||

| KIA-55389 | U867x867-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15D, winged head pin | 2 entrances, M2_CC4 | 6.0 | 0.28 | 75.93 ± 0.23 | -17.9 | 2219 ± 12 | ||

| KIA-55390 | U871x871-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Pin with grooved head, iron ring with shank | 2 entrances, M2_CC4 | 5.7 | 0.35 | 75.63 ± 0.22 | -21.5 | 2239 ± 17 | ||

| KIA-55391 | U884x884-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15D, winged head pin | 2 entrances, M2_CC4 | 4.8 | 0.22 | 75.95 ± 0.21 | -21.7 | 2211 ± 16 | ||

| RICH-24150 | U928x928-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15B, pin with type 2 coiled head, pin with circular head | 2 entrances, M1_CC3 | 7.3 | 0.05 | 75.13 | -20.6 | 2297 ± 25 | ||

| GrM-14599 | U1001x1001-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn types 18C and 15B, pin of unknown type, iron ring with shank | 2 entrances, M1_CC4 | 6.2 | 0.08 | 75.71 ± 0.14 | -23.0 | 2235 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-53095 | U1001x1001-1 | Replicate of GrM-14599; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.22 | 75.54 ± 0.19 | -20.1 | 2253 ± 21 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U1001x1001-1: T’ = 0.4, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2244 ± 15 BP | |||||||||||

| KIA-51900 | U1016x1016-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15B, iron ring with shank | 2 entrances, M1_CC4 | 6.7 | 0.23 | 75.85 ± 0.24 | -23.7 | 2220 ± 25 | ||

| KIA-55392 | U1018x1018-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15B, winged head pin, iron ring with shank | 2 entrances, M1_CC4 | 5.3 | 0.21 | 75.63 ± 0.22 | -17.6 | 2242 ± 17 | ||

| GrM-14592 | U1076x1076-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 18C, narrow belt clasp, bronze neck ring | 2 entrances, M1_CC4 | 6.4 | 0.08 | 75.47 ± 0.14 | -27.8 | 2260 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52822 | U1076x1076-1 | Replicate of GrM-14592; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.18 | 76.05 ± 0.28 | -25.3 | 2199 ± 29 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| RICH-25340 | U1076x1076-1 | Cremated bone (human) | - | - | 0.12 | 76.06 ± 0.26 | -25.5 | 2198 ± 27 | Rose et al. (2019) | ||

| Weighted mean U1076x1076-1: T’ = 4.8, T’ (5%) = 6.0, v = 2, 2229 ± 15 BP | |||||||||||

| GrM-14597 | U1186x1186-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 13A, 2 pins with type 1 coiled heads, simple iron ring | >2 entrances,M1_CC1 | 5.8 | 0.12 | 73.58 ± 0.13 | -24.7 | 2465 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-53096 | U1186x1186-1 | Replicate of GrM-14597; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.27 | 74.10 ± 0.18 | -24.1 | 2408 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U1186x1186-1: T’ = 4.1, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2437 ± 15 BP | |||||||||||

| RICH-25332 | U1232x1232-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15B, 2 pins with type 1 coiled heads | >2 entrances,M1_CC1 | 5.8 | 0.16 | 73.78 | -21.4 | 2443 ±27 | ||

| RICH-24143 | U1279x1279-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 13A, 2 pins with type 2 coiled heads | >2 entrances,M1_CC1 | 5.7 | 0.21 | 73.56 | -19.6 | 2467 ± 26 | ||

| GrM-14602 | U1363x1363-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15B, triangular belt clasp | 2 entrances, M1_CC4 | 6.5 | 0.07 | 75.79 ± 0.14 | -30.3 | 2225 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52828 | U1363x1363-1 | Replicate of GrM-14602; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.17 | 76.09 ± 0.23 | -27.9 | 2195 ± 24 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U1363x1363-1: T’ = 0.9, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2213 ± 16 BP | |||||||||||

| RICH-25335 | U1382x1382-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 18C, 2 pins with circular heads, triangular belt clasp | 2 entrances, M1_CC4 | 6.8 | 0.10 | 76.01 | -26.2 | 2204 ± 27 | ||

| RICH-25357 | U1422x1422-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 13D, pin with grooved head, narrow belt clasp | 2 entrances, M1_CC4 | 5.9 | 0.11 | 76.18 | -23.5 | 2186 ± 26 | ||

| RICH-25333 | U1436x1436-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15C, narrow belt clasp | 2 entrances, M1_CC4 | 5.9 | 0.11 | 75.55 | -25.3 | 2252 ± 28 | ||

| RICH-25334 | U1617x1617-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 18C, 2 pins with circular heads, bronze pin with grooved head, triangular belt clasp | 2 entrances, M1_CC5 | 5.4 | 0.14 | 76.39 | -25.6 | 2163 ± 28 | ||

| KIA-55393 | U1654x1654-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Pin with grooved head, iron ring with shank | 2 entrances, M1_CC5 | 5.9 | 0.31 | 76.22 ± 0.24 | -22.0 | 2183 ±14 | ||

| KIA-52340 | U1678x1678-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15C, narrow belt clasp | 2 entrances, M1_CC5 | 5.4 | 0.32 | 75.64 ± 0.23 | -22.3 | 2243 ± 25 | ||

| GrM-15074 | U1791x1791-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15C, triangular belt clasp | 2 entrances, M1_CC5 | 5.7 | 0.07 | 75.78 ± 0.26 | -30.0 | 2230 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52341 | U1791x1791-1 | Cremated bone (human) | - | - | - | 0.29 | 76.35 ± 0.23 | -29.63 | 2167 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U1791x1791-1: T’ = 3.2, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2199 ± 18 BP | |||||||||||

| RICH-24144 | U1834x1834-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 12B, tongue-shaped belt clasp | 2 entrances, M1_CC5 | 6.5 | 0.09 | 74.89 | -19.8 | 2322 ± 25 | ||

| KIA-55394 | U1834x1834-1 | Cremated bone (human), separate sample from RICH-24144 | - | - | 5.1 | 0.18 | 75.91 ± 0.23 | -25.7 | 2216 ± 18 | ||

| Weighted mean U1834x1834-1: T’ = 11.9, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2253 ± 15 BP | |||||||||||

| GrM-15075 | U1847x1847-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15C, triangular belt clasp | 2 entrances, M1_CC5 | 6.1 | 0.08 | 75.53 ± 0.20 | -25.4 | 2255 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52342 | U1847x1847-1 | Cremated bone (human) | - | - | - | 0.28 | 75.78 ± 0.24 | -28.9 | 2228 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U1847x1847-1: T’ = 0.7, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2244 ± 16 BP | |||||||||||

| KIA-55395 | U1894x1894-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Pin with rod-shaped head, iron ring with shank | 2 entrances, M1_CC5 | 5.1 | 0.24 | 75.94 ± 0.21 | -21.1 | 2211 ± 14 | ||

| KIA-52343 | U1970x1970-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15C, bronze pin with grooved head, narrow belt clasp | 2 entrances, M1_CC5 | 5.9 | 0.28 | 75.61 ± 0.22 | -22.8 | 2246 ± 23 | ||

| KIA-55396 | U1993x1993-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Pin with grooved head, iron ring with shank | 2 entrances, M1_CC5 | 5.1 | 0.35 | 75.82 ± 0.25 | -21.6 | 2228 ±15 | ||

| KIA-52344 | U1997x1997-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 18C, bronze pin with grooved head, triangular belt clasp | 2 entrances, M1_CC5 | 6.5 | 0.38 | 76.36 ± 0.26 | -30.6 | 2167 ± 27 | ||

| KIA-55397 | U2199x2199-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Holstein pin | 2 entrances, M1_CC6 | 5.3 | 0.15 | 75.59 ± 0.26 | -20.4 | 2244 ± 17 | ||

| GrM-14593 | U2262x2262-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 11D, narrow belt clasp | 2 entrances, M1_CC6 | 6.5 | 0.07 | 75.53 ± 0.16 | -20.9 | 2255 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52823 | U2262x2262-1 | Replicate of GrM-14593; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.24 | 75.92 ± 0.26 | -19.0 | 2214 ± 28 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U2262x2262-1: T’ = 1.2, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2237 ± 19 BP | |||||||||||

| KIA-55398 | U2293x2293-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15D, pin with rod-shaped head, iron ring with shank | 2 entrances, M1_CC6 | 6.7 | 0.05 | 76.19 ± 0.31 | -22.3 | 2185 ± 25 | ||

| KIA-55399 | U2354x2354-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15C, pin with rod-shaped head, iron ring with shank | 2 entrances, M1_CC6 | 7.9 | 0.12 | 75.70 ± 0.23 | -22.6 | 2237 ± 18 | ||

| KIA-55400 | U2366x2366-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 20B, pin with rod-shaped head, simple iron ring | 2 entrances, M1_CC6 | 5.8 | 0.22 | 75.75 ± 0.24 | -18.9 | 2232 ± 15 | ||

| KIA-55401 | U2455x2455-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Pin with rod-shaped head, simple iron ring | 2 entrances, M1_CC6 | 7.4 | 0.05 | 75.66 ± 0.30 | -21.5 | 2240 ± 25 | ||

| KIA-55402 | U2498x2498-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15D, winged head pin | 2 entrances, M1_CC6 | 7.7 | 0.08 | 76.37 ± 0.31 | -24.5 | 2165 ± 25 | ||

| RICH-24145 | U2541x2541-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 20D, Holstein pin, pin with flat pierced head, iron ring with shank, | 2 entrances, M1_CC6 | 5.9 | 0.06 | 75.89 | -22.7 | 2216 ± 26 | ||

| KIA-55403 | U2545x2545-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Pin with rod-shaped head, pin with small pierced head | 2 entrances, M1_CC6 | 6.1 | 0.15 | 76.11 ± 0.24 | -24.9 | 2194 ± 18 | ||

| RICH-24146 | U2550x2550-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15D, iron ring with shank | 2 entrances, M1_CC6 | 5.9 | 0.08 | 75.18 | -22.3 | 2291 ± 26 | ||

| KIA-55404 | U2593x2593-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 17D, Holstein pin, iron ring with shank | 2 entrances, M1_CC6 | 6.9 | 0.15 | 75.84 ± 0.23 | -21.9 | 2222 ± 17 | ||

| RICH-25355 | U2710x2710-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 11A, pin with bomb-shaped head, possibly second pin of same type, unknown pin type with bend neck | >2 entrances,M1_CC1 | 5.5 | 0.12 | 74.07 | -18.9 | 2411 ± 27 | ||

| GrM-14594 | U3330x3330-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15? Iron pin with coiled head and no bend neck | Founding burial | 6.8 | 0.10 | 72.96 ± 0.13 | -21.0 | 2535 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52824 | U3330x3330-1 | Replicate of GrM-14594; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.29 | 73.52 ± 0.24 | -21.5 | 2471 ± 26 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-51901 | U3330x3330-1 | Cremated bone (human), separate sample from KIA-52824 and GrM14594 | - | - | - | 0.28 | 73.23 ± 0.24 | -21.9 | 2503 ± 27 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U3330x3330-1: T’ = 3.9, T’ (5%) = 6.0, v = 2, 2509 ± 14 BP | |||||||||||

| RICH-25354 | U3341x3341-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of Bronze Age period VI type, side urn of pre-Roman Iron Age style, swan neck pin | Founding burial | 5.7 | 0.35 | 73.47 | -21.5 | 2477±27 | ||

| RICH-24147 | U3452x3452-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15B, 2 pins with type 1 coiled heads | >2 entrances,M1_CC1 | 6.2 | 0.12 | 73.03 | -19.1 | 2525 ± 25 | ||

| RICH-24148 | U3778x3778-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 12B, 2 pins with type 2 coiled heads, simple iron ring | >2 entrances,M1_CC1 | 5.4 | 0.12 | 73.7 | -18.1 | 2452 ± 25 | ||

| KIA-52345 | U3822x3822-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 11B, 2 pins with type 1 coiled heads | >2 entrances,M2_CC1-3 | 5.5 | 0.26 | 73.87 ± 0.24 | -23.9 | 2433 ± 26 | ||

| GrM-15076 | U3869x3869-1 | Cremated bone (human) | Urn, open with no neck. Iron pin with round head and no neck bend | Founding burial | 6.0 | 0.09 | 72.87 ± 0.16 | -21.6 | 2540 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-52346 | U3869x3869-1 | Cremated bone (human) | - | - | - | 0.21 | 73.66 ± 0.23 | -25.9 | 2456 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| RICH-24152 | U3869x3869-1 | Cremated bone (human) | - | - | - | 0.20 | 73.22 ± 0.24 | -25.8 | 2504 ± 26 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean U3869x3869-1: T’ = 6.9, T’ (5%) = 6.0, v = 2, 2507 ± 14 BP | |||||||||||

| Aarre urnfield cemetery (VAM 1600) | |||||||||||

| KIA-53941 | A86x339 (urn) | Acer sp. trunk wood charcoal (Ø >10 cm) | - | - | - | 63.96 | 73.60 ± 0.23 | -25.3 | 2463 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53942 | A86x340 (urn) | Cremated bone (human) | - | - | 5.4 | 0.35 | 74.37 ± 0.24 | -19.7 | 2379 ± 26 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53942 | A86x340 (urn) | Cremated bone (human), replicate | Urn of unknown type, 2 pins with type 2 coiled heads | - | - | - | 74.31 ± 0.23 | -22.8 | 2385 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| Weighted mean A86x340: T’ = 0.0, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2382 ± 19 BP | |||||||||||

| RICH-25356 | A89x311 (urn) | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 13, 2 pins with type 1 coiled heads | - | 6.4 | 0.16 | - | -21.18 | 2464 ± 27 | ||

| KIA-53984 | A95x368 no.1 (urn) | Quercus sp. twig charcoal (Ø <0.3 cm) | - | - | - | 70.68 | 74.45 ± 0.23 | -28.4 | 2370 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53985 | A95x368 no.3 (urn) | Acer sp. twig charcoal (Ø <0.5 cm) | - | - | - | 70.49 | 73.90 ± 0.23 | -27.7 | 2430 ± 26 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| RICH-25342 | A95x369 (urn) | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 16? | - | 7.8 | 0.11 | 73.90 ± 0.25 | -24.3 | 2428 ± 27 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| RICH-25071 | A99x65 no.2 (pit) | Alnus sp. trunk wood charcoal (Ø 8-10 cm) | - | - | - | 60.00 | 75.39 ± 0.28 | -33.3 | 2269 ± 29 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| RICH-25067 | A99x65 no.3 (pit) | Quercus sp. trunk wood charcoal (Ø <10 cm) | - | - | - | 61.00 | 67.85 ± 0.26 | -31.6 | 3115 ± 31 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| GrM-16774 | A99x345 (urn) | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, pin with type 1 coiled head | - | 6.5 | 0.06 | 75.50 ± 0.17 | -26.5 | 2255 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| RICH-25069 | A99x346 no.1 (urn) | Alnus sp. twig charcoal (Ø <0.3 cm) | - | - | - | 53.50 | 77.14 ± 0.28 | -31.8 | 2085 ± 29 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| RICH-25066 | A99x346 no.27 (urn) | Alnus sp. trunk wood charcoal (Ø > 10 cm) | - | - | - | 61.60 | 75.56 ± 0.28 | -35.3 | 2251 ± 30 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| GrM-14604 | A117x762 (urn) | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 12, elaborate set of chain and pins | - | 6.0 | 0.10 | 73.75 ± 0.13 | -25.7 | 2445 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-53098 | A117x762 (urn) | Replicate of GrM-14604; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.28 | 74.03 ± 0.19 | -22.1 | 2416 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean A117x762: T’ = 1.1, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2431 ± 15 BP | |||||||||||

| KIA-53943 | A117x769 (urn) | Quercus sp. charcoal (Ø >10 cm) 1 annual ring sampled | - | - | - | 31.21 | 73.72 ± 0.23 | -23.6 | 2449 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53944 | A117x774 (urn) | Quercus sp. charcoal (Ø >10 cm) | - | - | - | 60.58 | 73.30 ± 0.22 | -25.0 | 2495 ± 24 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53945 | A130x82 no.1 (urn) | Charred grass stem | Pin of unknown type, tongue-shaped belt clasp, | - | - | 68.30 | 72.49 ± 0.23 | -25.1 | 2585 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53946 | A130x82 no.2 (urn) | Triticum cf. aestivum, charred cereal | - | - | - | 64.19 | 76.46 ± 0.23 | -28.5 | 2156 ± 24 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53947 | A130x217 (urn) | Cremated bone (human) | - | - | 5.8 | 0.24 | 75.57 ± 0.23 | -20.9 | 2250 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53947 | A130x217 (urn) | Cremated bone (human), replicate | - | - | - | - | 75.52 ± 0.23 | -21.7 | 2255 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| Weighted mean A130x217: T’ = 0.0, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2253 ± 18 BP | |||||||||||

| KIA-53948 | A155x127 no.1 (urn) | cf. Triticum sp., charred cereal | - | - | - | 50.00 | 73.31 ± 0.22 | -26.4 | 2494 ± 24 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53949 | A155x127 no.2 (urn) | Arrhenatherum elatius ssp. Bulbosum, charred grass bulb | - | - | - | 65.52 | 73.56 ± 0.22 | -28.2 | 2466 ± 24 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53950 | A155x281 (urn) | Cremated bone (human) | Pin with circular head | - | 6.1 | 0.26 | 74.55 ± 0.23 | -23.6 | 2359 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53950 | A155x281 (urn) | Cremated bone (human), replicate | - | - | - | - | 74.41 ± 0.23 | -24.1 | 2374 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| Weighted mean A155x281: T’ = 0.2, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2367 ± 18 BP | |||||||||||

| KIA-53951 | A198x338 (urn) | Alnus sp. trunk wood charcoal (Ø >10 cm) | - | - | - | 57.02 | 69.12 ± 0.21 | -24.9 | 2967 ± 24 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53952 | A198x338 CB (urn) | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, 2 pins with type 2 coiled heads | - | 5.9 | 0.28 | 74.89 ± 0.24 | -24.9 | 2323 ± 26 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53952 | A198x338 CB (urn) | Cremated bone (human), replicate | - | - | - | - | 74.82 ± 0.29 | -25.9 | 2330 ± 35 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| Weighted mean A198x338 CB: T’ = 0.0, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2325 ± 21 BP | |||||||||||

| GrM-14707 | A281x484 (urn) | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15, 2 pins with circular heads | - | 6.2 | 0.10 | 74.91 ± 0.13 | -28.0 | 2320 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-53100 | A281x484 (urn) | Replicate of GrM-14707; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | 0.11 | 75.37 ± 0.19 | -23.5 | 2271 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | ||

| Weighted mean A281x484: T’ = 3.9, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2296 ± 15 BP | |||||||||||

| KIA-53953 | A278x782 no.1 (urn) | Charred grass stem | - | - | - | 74.57 | 74.17 ± 0.23 | -27.5 | 2400 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53954 | A278x782 no.2 (urn) | Charred grass, stem and root fragment | - | - | - | 67.11 | 73.76 ± 0.23 | -26.2 | 2445 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53955 | A278x783 (urn) | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, 2 pins with disc-shaped heads, bronze ring | - | 5.5 | 0.20 | 73.47 ± 0.24 | -22.7 | 2477 ± 26 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53955 | A278x783 (urn) | Cremated bone (human), replicate | - | - | - | - | 73.71 ± 0.23 | -22.9 | 2450 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| Weighted mean A278x783: T’ = 0.6, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2463 ± 19 BP | |||||||||||

| RICH-25068 | A393x568 no.1 (pit) | Triticum dicoccum, charred cereal | - | - | - | 61.10 | 69.69 ± 0.28 | -29.9 | 2901 ± 32 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| RICH-25070 | A393x568 no.2 (pit) | Hordeum vulgare nudum, charred cereal | - | - | - | 44.30 | 69.58 ± 0.28 | -27.2 | 2914 ± 32 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| RICH-25341 | A393x561 CB (urn) | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, 2 pins with type 1 coiled heads | - | 6.4 | 0.16 | 73.90 ± 0.25 | -25.3 | 2480 ± 27 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-52411 | A393x561 no.1 (urn) | Hordeum vulgare nudum, charred cereal | - | - | - | 54.67 | 67.70 ± 0.21 | -24.0 | 3134 ± 25 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-52412 | A393x561 no.3 (urn) | Hordeum vulgare nudum, charred cereal | - | - | - | 32.35 | 67.57 ± 0.22 | -21.9 | 3150 ± 27 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-52413 | A393x561 Quercus (urn) | Quercus sp. trunk wood charcoal (Ø >10 cm) | - | - | - | 24.78 | 72.25 ± 0.24 | -25.7 | 2611 ± 27 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-52414 | A394x556 no.1 (urn) | Alnus sp. charcoal from branch sapwood (Ø 3-5 cm) | - | - | - | 26.74 | 70.77 ± 0.23 | -24.9 | 2778 ± 27 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53983 | A394x781 no.9 (urn) | Acer sp. trunk wood charcoal (Ø > 10 cm) | - | - | - | 66.85 | 68.58 ± 0.21 | -27.0 | 3029 ± 24 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| GrM-14708 | A394x785 CB (urn) | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, 2 pins with type 2 coiled heads | - | 6.3 | 0.10 | 73.57 ± 0.11 | -21.2 | 2465 ± 18 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| KIA-53099 | A394x785 CB (urn) | Replicate of GrM-14708; apatite pretreated at CIO, CO2 extracted and dated at KIA. | - | - | - | 0.14 | 73.97 ± 0.19 | -22.7 | 2422 ± 20 | Rose et al. (2019) | |

| Weighted mean A394x785 CB: T’ = 2.6, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2446 ± 14 BP | |||||||||||

| KIA-52415 | A394x785 no.1 (urn) | Triticum aestivum, charred cereal | - | - | - | 37.76 | 70.19 ± 0.23 | -23.0 | 2843 ± 26 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-52416 | A394x785 no.4 (urn) | Alnus sp. heartwood charcoal (Ø 2-3 cm) | - | - | - | 28.07 | 70.82 ± 0.23 | -27.9 | 2772 ± 26 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-52417 | A394x786 no.1 (urn) | Quercus sp. trunk wood charcoal (Ø >10 cm) | - | - | - | 51.01 | 71.29 ± 0.24 | -25.2 | 2719 ± 27 | Rose et al. (2020) | |

| Søhale urnfield cemetery (ESM 2139) | |||||||||||

| AAR-25251 | G3x22-III | Cremated bone (adult) | Urn of unknown type, unknown iron object | Multiple entrances | - | - | 75.94 ± 0.26 | -25 | 2211 ± 27 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| AAR-25250 | G5x21-III | Cremated bone, 25-40yrs (adult), female? | Belt clasp? | Multiple entrances | - | - | 75.5 ± 0.25 | -27 | 2258 ± 27 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53937 | G7x37-III | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 13C, pin with circular head | NNE-SSW entrances | 5.1 | 0.38 | 75.86 ± 0.23 | -21.9 | 2220 ± 20 | ||

| KIA-53936 | G9x19-II | Cremated bone (human) | 2 pins with large circular heads | NNE-SSW entrances | 6.2 | 0.23 | 75.43 ± 0.24 | -25.8 | 2265 ± 26 | ||

| RICH-26501 | G10x23-II | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, 2 pins with circular head | NNE-SSW entrances | - | 0.10 | 74.97 ± 0.23 | -22.8 | 2314 ± 24 | ||

| AAR-25249 | G11x18-III | Cremated bone, 6-15yrs (infans) | Pin of unknown type, narrow belt clasp | N-S entrances | - | - | 76.19 ± 0.26 | -28 | 2185 ± 27 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| AAR-25248 | G12x17 | Cremated bone (infans-adult) | None | NNE-SSW entrances | - | - | 75.46 ± 0.37 | -26 | 2262 ± 40 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| AAR-25243 | G19x10-II | Cremated bone, 2-10yrs. (infans) | Urn of unknown type | NNE-SSW entrances | - | - | 75.93 ± 0.29 | -24 | 2212 ± 30 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| AAR-25244 | G31x12/x25A | Cremated bone (adult) | None | NNE-SSW entrances | - | - | 76.22 ± 0.36 | -29 | 2181 ± 38 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| AAR-25245 | G31x12/x25B | Cremated bone (adult) | None | - | - | - | 75.74 ± 0.32 | -24 | 2232 ± 34 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| Weighted mean G31x12: T’ = 1.0, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2209 ± 26 BP | |||||||||||

| AAR-25246 | G32x14 | Cremated bone (infans-adult) | Urn type 15C | NNE-SSW entrances | - | - | 74.74 ± 0.25 | -23 | 2339 ±26 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| GrM-16770 | G34x40-II | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, pin with circular head | ?-SSW entrances | - | 0.10 | 75.79 ± 0.18 | -23.5 | 2227 ± 19 | ||

| RICH-26493 | G35x28-II | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, tongue-shaped belt clasp | NNE-SSW entrances | - | 0.26 | 75.62 ± 0.25 | -26.3 | 2245 ± 27 | ||

| AAR-25253 | G37x27-I | Cremated bone (infans-adult) | None | NNE-S entrances | - | - | 75.7 ± 0.28 | -24 | 2237 ± 30 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| RICH-26494 | G39x31-II | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15? Pin with circular head, pin with bend neck | NNE-SSW entrances | - | 0.10 | 74.76 ± 0.25 | -24.6 | 2337 ±27 | ||

| AAR-25254 | G40x30-III | Cremated bone (infans-adult) | Eyelet ring, triangular belt clasp | NNE-SSW entrances | - | - | 74.9 ± 0.26 | -26 | 2322 ± 28 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| RICH-26495 | G44x38-II | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15, narrow belt clasp | NNE-SSW entrances | 5.9 | 0.06 | 75.54 ± 0.24 | -28.8 | 2254 ± 26 | ||

| KIA-53938 | G44x38-II | Replicate of RICH-26495 | - | - | - | 0.22 | 76.12 ± 0.25 | -21.5 | 2192 ± 27 | ||

| Weighted mean: G44x38-II: T’ = 2.7, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2224 ± 19 BP | |||||||||||

| AAR-25257 | G48x35-II | Cremated bone, <20yrs (adult), male. | Urn type 12C | N entrance | - | - | 73.54 ± 0.24 | -26 | 2469 ± 26 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| AAR-25258 | G51x47-III | Cremated bone, <40yrs (matures), male? | Urn type 15, 2 pins with type 1 coiled heads | NNW-S entrances | - | - | 73.98 ± 0.25 | -19 | 2421 ± 27 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| AAR-25256 | G52x33-II | Cremated bone, <35yrs (maturus), male? | Urn of unknown type | NNE-SSE entrances | - | - | 74.61 ± 0.25 | -24 | 2353 ± 27 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| RICH-26502 | G53x34-II | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, 2 pins with circular head | NNE-SSE entrances | - | 0.37 | 74.71 ± 0.24 | -25.8 | 2342 ± 26 | ||

| AAR-25255 | G54x32-II | Cremated bone, <30yrs (adult) | Urn of unknown type, 2 pins with circular head | NNE-SSW entrances | - | - | 74.15 ± 0.27 | -29 | 2403 ± 29 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| GrM-16771 | G57x41-V | Cremated bone (human) | Urn 13C, narrow belt clasp, 1 pin with circular head, 1 pin of unknown type | NNE-SSW entrances | - | 0.09 | 74.46 ± 0.19 | -25.8 | 2370 ± 20 | ||

| GrM-16772 | G59x44-II | Cremated bone (human) | 2 pins with coiled head, type 1 and 2 | No entrances | 5.8 | 0.09 | 73.60 ±0.20 | -26.5 | 2465 ±20 | ||

| KIA-53939 | G59x44-II | Replicate of GrM-16772 | - | - | - | 0.34 | 73.55 ± 0.23 | -24.1 | 2468 ± 25 | ||

| Weighted mean G59x44-II: T’ = 0.0, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2466 ± 16 BP | |||||||||||

| GrM-16773 | G60x49-III | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, pin with type 1 coiled head, bronze ring with eyelet | No entrances | - | 0.15 | 73.92 ±0.16 | -25.5 | 2425 ±19 | ||

| AAR-25260 | G63x51-IV | Cremated bone, <35yrs (maturus), male? | Urn type 15C, pin with type 1 coiled head, pin of unknown type | No entrances | - | - | 73.8 ± 0.25 | -25 | 2440 ± 27 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53431 | G64x50-II | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15B, pin with type 2 coiled head, fragments of a pin of unknown type | No entrances | 5.5 | 0.29 | 73.82 ±0.19 | -21.9 | 2438 ±21 | ||

| AAR-25261 | G69x52-II | Cremated bone, 12-18yrs (juvenilis) | Urn type 15C, pin with type 1 coiled head, minimum 2 pins with neck bend | No entrances | - | - | 74.01 ± 0.28 | -21 | 2418 ± 31 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| AAR-25262 | G70x55-II | Cremated bone, <35yrs (maturus), male? | Urn type 13 | N-E entrances | - | - | 74.68 ± 0.26 | -26 | 2345 ± 27 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53435 | G73x92-III | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, pin with type 1 coiled head, pin with bend neck and head, imitation of pin x92-I? | No entrances? | 6.0 | 0.39 | 73.93 ±0.19 | -24.2 | 2427 ±21 | ||

| AAR-25263 | G81x65-V | Cremated bone <35yrs (maturus), female? | Urn of unknown type, 2 pins with slightly coiled heads, iron ring with shank | N-S entrances | - | - | 74.97 ± 0.26 | -18 | 2314 ± 28 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| AAR-25265 | G82x93-II | Cremated bone, <25yrs (adult), male? | Urn type 15, 2 pins, hereof at least one with type 2 coiled head | ?-S entrance(s) | - | - | 74.3 ± 0.27 | -24 | 2387 ± 29 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| AAR-25264 | G87x69-IV | Cremated bone, >25yrs (adult) | Urn of unknown type, pin with circular head, pin with neck bend | NNE-SSW entrances | - | - | 75.08 ± 0.27 | -26 | 2303 ± 28 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| AAR-25252 | G93x26-III | Cremated bone (infans-adult) | Pin with small circular head, tongue-shaped belt clasp | Multiple entrances | - | - | 75.32 ± 0.36 | -20 | 2277 ± 38 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

| KIA-53434 | G105x76-II | Cremated bone (human) | Urn type 15C, pin with type 2 coiled head, pin with type 1 coiled head | No burial mound | 6.0 | 0.24 | 73.86 ±0.19 | -29.0 | 2434 ±21 | ||

| KIA-53940 | G105x76-II | Replicate of KIA-53434 | - | - | - | 0.21 | 73.90 ± 0.24 | -27.4 | 2429 ± 26 | ||

| Weighted mean G105x76-II: T’ = 0.0, T’ (5%) = 3.8, v = 1, 2432 ± 17 BP | |||||||||||

| KIA-53433 | G107x74-II | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, pin with type 2 coiled head, pin with type 1 coiled head | No burial mound | 5.9 | 0.33 | 74.42 ±0.19 | -22.6 | 2373 ±21 | ||

| KIA-53432 | G110x72-VII | Cremated bone (human) | Urn of unknown type, flat iron ring, 2 pins with type 2 coiled heads | No burial mound | 6.4 | 0.44 | 74.34 ±0.19 | -23.1 | 2382 ±21 | ||

| AAR-25259 | G111x48-II | Cremated bone (adult) | Urn of unknown type | N-S entrances | - | - | 73.62 ± 0.27 | -26 | 2460 ± 30 | Møller et al. (2020) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).