1. Introduction

In everyday communication, non-verbal language plays an important role alongside verbal language, for example through the use of hand gestures. They help us to express feelings and thoughts, to give context to spoken language (e.g., by pointing to something while speaking), or even to replace spoken language completely (e.g., by using the thumbs up gesture to signal to the other person that everything is okay).

With technological progress, the desire to transfer this natural way of interpersonal interaction to computers is increasing. Thus, machines could be controlled directly using gestures: Instead of the user learning to control the machines, they should use natural and instinctive means of communication, and the machine learns to understand them.

In addition, even within a computer-generated environment, such as Virtual Reality (VR), interpersonal communication could be accomplished through the use of gestures. This would allow simple hand gestures, such as the aforementioned

thumbs up gesture, to be used in the context of operational force training. Significantly more complex issues could also be presented in the context of sign language, either because this is given by the application (e.g., sign learning software) or because this is the user’s primary form of communication, e.g., for deaf and hard of hearing people. This is an aspect that is becoming increasingly important because, according to the World Health Organization [

1], there are approximately 430 million people worldwide with some degree of hearing loss, and the trend is increasing. Where hearing people within vr communicate predominantly by microphone in their spoken language, the deaf and hard of hearing have to express themselves non-verbally, for example via a chat function. In addition, they cannot hear when other users communicate via the microphone. There are speech-to-text solutions that can display the spoken word as text, but an approach that can also convert signs into text or speech would still have to be developed for bidirectional communication.

Developing a system that can recognize and translate signs requires first determining how signs are structured. Linguist

William C. Stokoe [

2,

3] was one of the first to break down signs into their characteristic components. According to him, a sign consists essentially of the parameters of the hand shape, the orientation of the hand, the movement of the hand, and the location of execution of the sign. Other non-manual parameters such as facial expression are also conceivable, but the most important parameter is the hand shape [

4]. This is also evident when looking at the American Sign Language (ASL) finger alphabet: There are 26 signs with a total of 21 different hand shapes, which are all performed with the dominant hand. Two pairs of signs have the same hand shapes, but differ by having a movement of the hand (

I ⇔

J and

1⇔

Z). Three other pairs of signs have the same hand shapes, but differ in the orientation of the hand (

K⇔

P,

G⇔

Q and

H⇔

U).

To determine the hand shapes of an entire vocabulary, a suitable data set is needed.

ASL-Lex is a public sign lexicon for asl [

5,

6]. It contains videos and information on 2,723 signs. One component of this information is the so-called

Phonological Coding System, which is based on the

Prosodic Model of Sign Language by Brentari [

7]. It describes signs based on their characteristic features, similar to the aforementioned notation system of Stokoe [

3], only with significantly more parameters. To the best of our knowledge, there is no other publicly accessible database of this size that displays gestures in parametric form.

To recognize hand shapes reasonably, it also needs the appropriate hardware. There are different approaches, which can be distinguished in particular into video-based and (other) sensor-based approaches. In vr, data gloves are often used as an alternative to traditional controllers because they can capture hand shapes and movements even in complex motion sequences and are independent of occlusions [

8].

The main application of data gloves is hand gesture recognition, especially for static gestures. Between 2015 and 2022, more than 100 papers were published in English on this topic in reputable sources, like Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) or Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), according to the Web of Science (WoS). More than 70% of these examine static gestures [

9].

Even though these papers all pursue the topic of hand gesture recognition with data gloves, they differ in some points:

i) Used classification methods,

ii) number of participants,

iii) number of samples,

iv) number of hand gestures,

v) type of hand gestures. The type of hand gestures is defined by the used features. The more features are present, the more information is available for the classifier to successfully recognize the hand gesture. Therefore, many of these papers ([

10,

11,

12]) not only use hand shape information for classification, but also add hand orientation as an additional feature.

A distinction is also made between static and dynamic gestures: Static gestures possess spatial information, like the already mentioned hand shape, the orientation of the hand or the location of the hand where the gesture is performed. Dynamic gestures additionally possess temporal information, such as the movement of the hand [

12], the rotation of the ulnar, or a change in finger pose (e.g., closed fingers that are spread) [

5]. Therefore, some of the papers use dynamic gestures instead of static ones [

10,

12,

13,

14].

1.1. Goal and Methodology

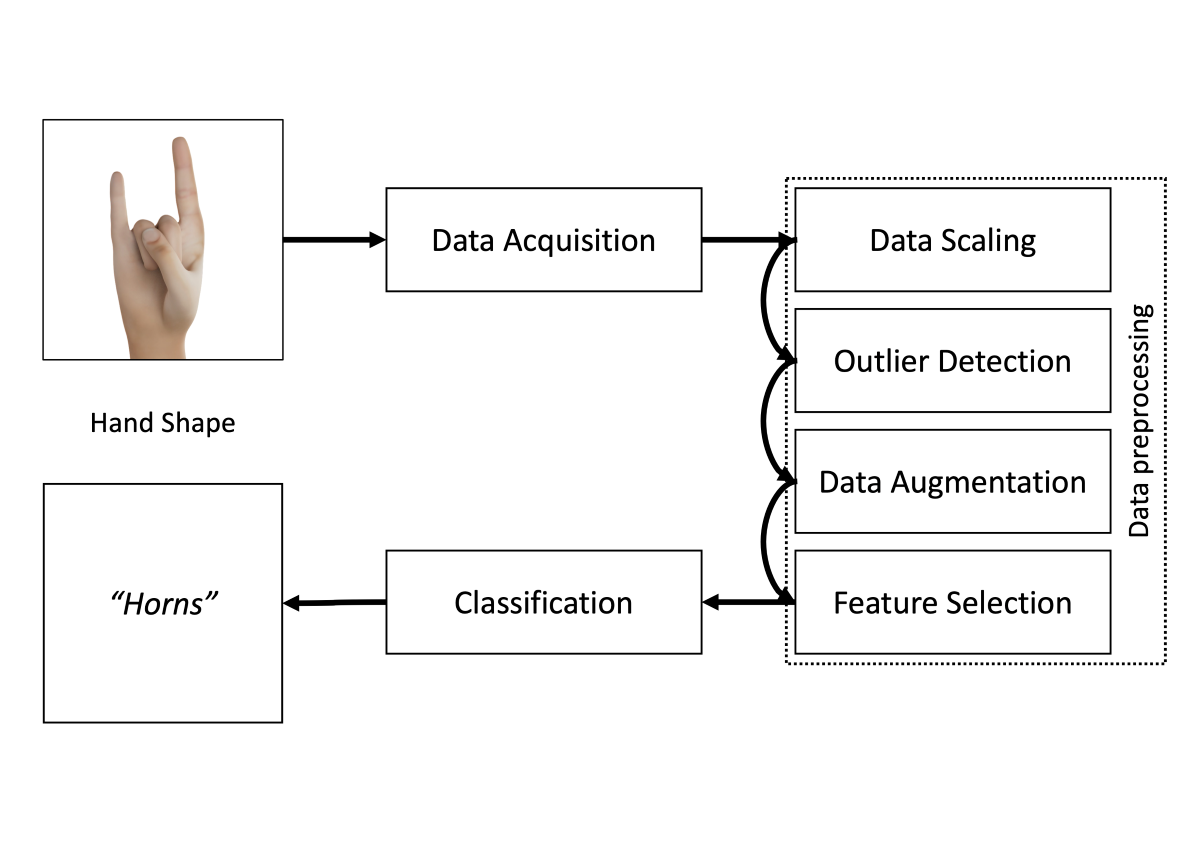

In this work, we focus on the recognition of static hand shapes with data gloves. We investigate whether commercially available data gloves are suitable for recognizing hand shapes of sign language in the use of vr. For this purpose, we designed a classification pipeline to reliably detect static hand shapes using a generalizable approach that can be used for other static data. The individual steps of data preprocessing will be examined with respect to their performance (accuracy and time for classification) and a recommendation is made as to which steps should be used for which use case. The classification pipeline can be seen in

Figure 1.

First, we acquire the hand shape with a Manus Prime X data glove. To ensure high quality data, an Outlier Detection method Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (DBSCAN) is applied to the training data. The data is further augmented using a proprietary method and thus artificially duplicated with the goal to counteract overfitting of the classification. To reduce the amount of training data and increase the speed of training and classification, we apply Feature Selection in the form of Genetic Algorithm (GA).

For evaluation, we chose two different data sets: 27 hand shapes from the asl finger alphabet (letters and numbers) and 56 hand shapes from a 2,700+ word lexicon of asl. On the one hand, this covers a variety of different hand shapes and, at the same time, serves to be able to create a basis for a sign language application within vr.

Our pipeline is generic and can be applied to any type of static data as long as it is in the correct data format. However, it is recommended to adjust the various parameters of the pipeline, such as the hyperparameters of the classifiers to the new data.

2. Data Acquisition

To reliably recognize hand shapes, these must be recorded in a suitable form. The recordings can then be used to train Machine Learning (ML) classifiers. Attention must be paid to the choice of suitable hardware and the selection of features to be captured.

The data gloves that were used during our experiment are the

Manus Prime X Haptic1 and are specifically designed for use within vr. The gloves can be seen on

Figure 2.

A 9-Degrees of Freedom (DoF) IMU and a 2D flex sensor is attached on each finger to obtain reliable values about the flexion/stretch of the fingers but also the spread between each finger. The latter information is not available in some data gloves, but is indispensable for distinguishing individual hand shapes such as

R,

U and

V (see

Figure 3) [

9]. A 6-DoF IMU is attached to the back of the hand to get its orientation. The accuracy of each finger measurement is

degrees.

The acquired sensor values are internally fused and preprocessed by the

Manus Core C++ SDK2. The preprocessed data is transferred to the computer via Bluetooth. According to the manufacturer, the latency is less than

, and the glove’s sensor sampling rate is

.

Table 1 shows all spread and stretch values given by the SDK that we use as features to represent each static gesture.

To obtain the best quality sensor data, the gloves must be calibrated. This is done by performing three simple gestures via the SDK. This also compensates for deviations that may occur due to differently sized user hands. The calibration is stored in the glove so that it is immediately ready for use for the next session.

3. Data Preprocessing

The main idea of

Data Preprocessing is to highlight important information in the available data while also removing some of the redundant or misleading data that may be present [

10].

The first step of

Data Preprocessing is often to scale all data to a predetermined interval.

or

are often used. Alternatively, statistical properties of the training data can be used for scaling. In this work, we use sklearn’s

StandardScaler.

3 It calculates the average value of each feature

i, subtracts it from each data point and divides it by the standard deviation.

In this way, all features follow a normal distribution with zero mean and unit variance. We chose this scaling procedure because it has been shown that some models, such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) or certain linear models, may perform worse when the data are not scaled and centered around zero [

16,

17].

Other than scaling the data, we implemented several Outlier Detection and Feature Selection methods that sort out misleading data samples or unimportant features. We also experimented with various Data Augmentation techniques to artificially enrich our data set with the goal to improve the generalizability of our approach. The best methods in each category are presented in the following.

3.1. Outlier Detection

Outliers are samples that differ greatly from the other recorded samples. Outliers can occur during data acquisition, for example due to sensor drift or because a user performs a gesture incorrectly. Such outliers can negatively impact the performance of ml classifiers, as it is often best for these models to be able to generalize and not over-fit the data [

18].

Outlier Detection therefore aims to find and remove all outliers within the given data.

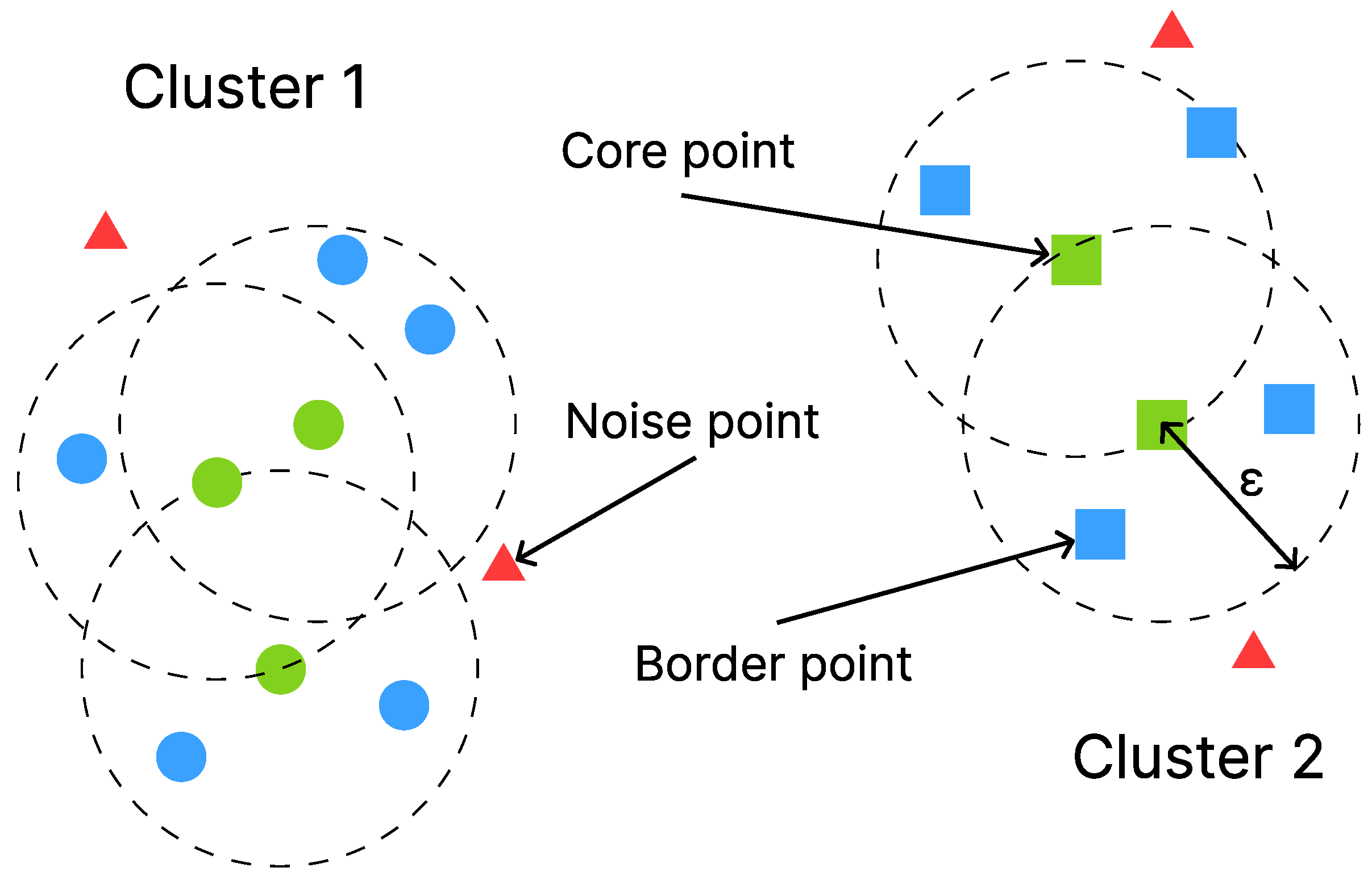

Many algorithms used to achieve this goal are similar to clustering algorithms in that samples are also combined to form clusters. Points that do not belong to any cluster are then identified as outliers. In this work, we used the dbscan algorithm. dbscan starts at a random data point and searches for other samples within a predefined distance . If the number of samples within this distance is greater than the minPoints parameter, the original point is marked as a Core Point. This step is repeated for all data points. Afterwards a random Core Point is selected and the point itself and all neighboring points within are added to a cluster. When all Core Points have been assigned to a cluster, the algorithm terminates. All samples that are not part of any cluster are considered outliers.

The algorithm can be controlled by the

and

minPoints parameters.

Figure 4 shows how DBSCAN assigns multiple points into two clusters.

minPoints is set to four in this example

4.

Outlier Detection is rarely used in other works on gesture recognition. Most often, outliers are removed from the test set. This is usually done, when outliers and incorrect predictions in the application phase can have serious consequences, such as in the medical field. In these scenarios it is often more favourable to detect outliers and output a warning alongside the models’ prediction. Related works that operate in this way are, for example, by Zhang

et al. [

19] or by Palipana

et al. [

20].

In this work, we focused on detecting outliers only in the training data, since our application phase is not as critical at this time and it can be more easily compared to most other gesture recognition work. Test data should also, in our opinion, represent a possible real-world scenario, this includes biases in sensor values or erroneous user executions.

Once the Outlier Detection has been performed, the remaining data is scaled again according to the principle described above.

3.2. Data Augmentation

In order to use ml models for reliable hand shape classification, a sufficient amount of high-quality training data must be available. In particular, in the application area of gesture recognition with the use of wearable sensors as a data source, the acquisition of large amounts of data for learning poses one of the main challenges due to the cumbersome acquisition process. This is because the data must be physically gathered from individuals equipped with wearable sensors and then carefully labeled afterwards (see

Section 2), which takes time and effort and usually yields inadequate quantities, especially for deep learning approaches [

21]. In addition, further challenges may arise, for example, at the time of the

Covid 19 pandemic, which required even stricter hygiene standards and therefore may increase the cost of physical data acquisition with wearable sensors. Thus, building a rich and diverse data set may become even more laborious. This potential scarcity of training data can then lead to poor generalization capabilities of the model.

One way to deal with these problems is the use of

Data Augmentation to artificially enrich the training data set. This is usually done by applying transformations to the existing data to create new, synthetic data samples.

Data Augmentation can therefore be employed as a preprocessing step in order to ultimately reduce overfitting and enhance the robustness and generalizability of the ml models used. [

22]

However, the applicability of different Data Augmentation methods depends on the type of data available and corresponding sensor technology, and therefore must be evaluated for the specific task at hand. Depending on these factors, and additionally on the ml classifiers used, the effectiveness of Data Augmentation may vary.

As introduced in

Section 2, static spread and stretch values for each joint are used in this work as features. However, the available literature on

Data Augmentation for wearable sensors is mainly concerned with dynamic data consisting of a gesture performed within a certain time interval. For example, Um et al. [

22] conducted one of the most comprehensive evaluations of

Data Augmentation techniques for wearable sensor data used in dynamic approaches. These methods leverage variations in orientation or timing and are therefore not applicable in this setting since the available data does not capture positional or dynamic properties. In contrast, the literature on

Data Augmentation for static hand shape recognition is rather scarce and mostly not the subject of studies. However, in this work, we have adapted a

Data Augmentation approach presented by Liu and Ostadabbas [

23] so that it is applicable to the available data and can be used in our setting as a means with the goal to reduce overfitting and improve the generalizability of the models by introducing more variety to the way hand shapes are performed. Below, we present the

Data Augmentation approach we use to generate artificial data samples, i.e. hand shapes.

3.2.1. Methodology

We have adopted and slightly adapted a

Data Augmentation approach presented by Liu and Ostadabbas [

23], where joint angle constraints are used to define range boundaries for each joint. Using these range boundaries, new poses can be generated by randomly sampling within the defined limits for each joint. This ensures that the newly generated data samples are valid, since the boundaries can be set appropriately.

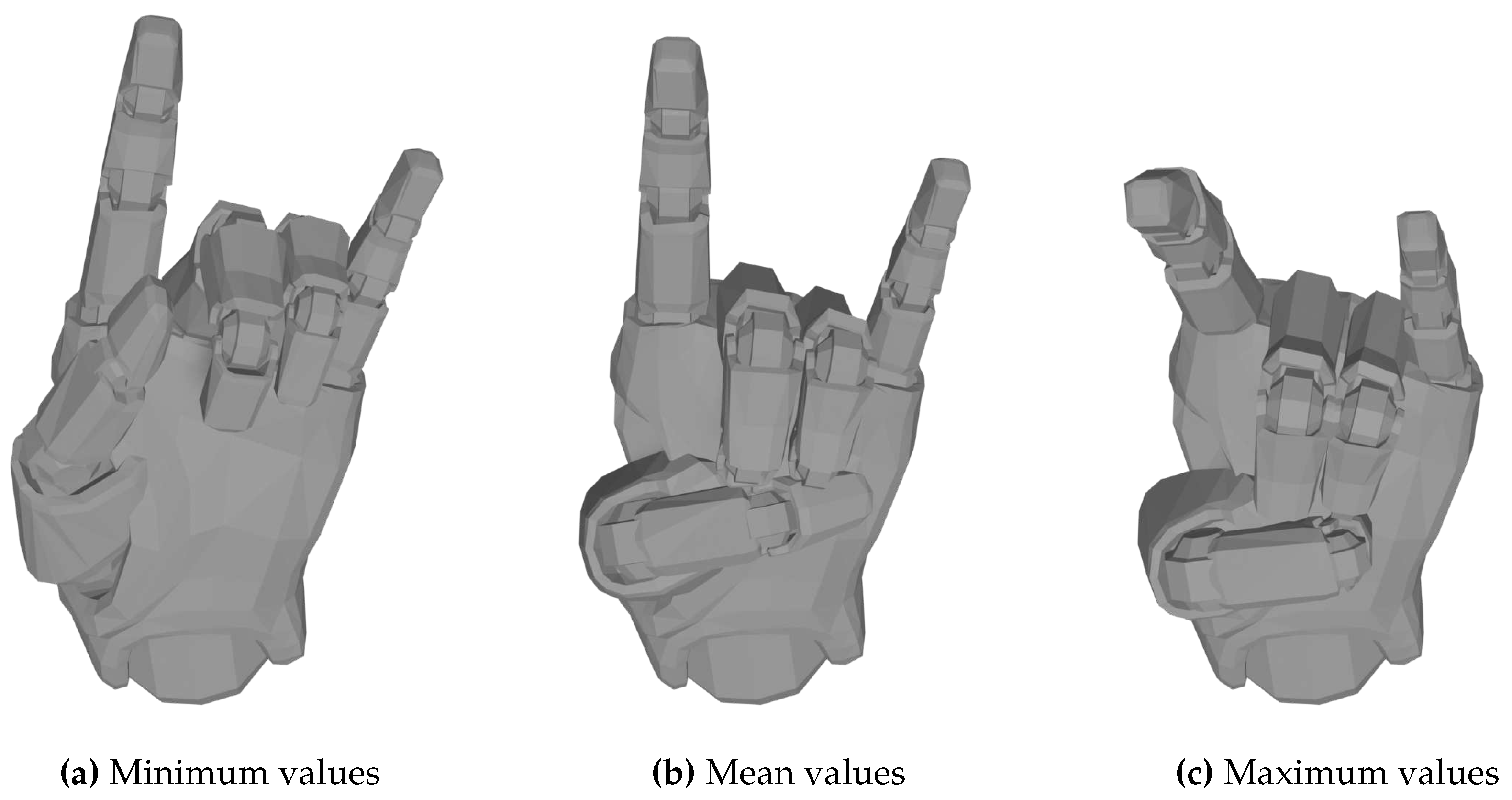

We modified this approach to generate new data samples for each specific hand shape (i.e. label). Therefore, these range boundaries must be chosen differently for each hand shape and define the amount of maximum and minimum joint bending that is still considered to be the respective hand shape. This would be required for each hand shape of our data set. In this work, we define the limits by first calculating the respective minimum and maximum joint values for each hand shape from the available data. As an example,

Figure 5a and

Figure 5c show the minimum and maximum hand shape for the

Horns label, which is illustrated in

Table A1 in the appendix

5. Compared to the mean hand shape in

Figure 5b, it becomes apparent that there may be slight variations in the way a hand shape is performed by individuals due to anatomical differences, which may lead to larger disparities in some feature values depending on the hand shape. In addition, inaccuracies of the data glove sensors also seem to play a role, because although the hand shapes were recorded under supervision and performed again in case of errors, there are still sometimes large differences in the data. These two factors can lead to large differences in some joint values, especially in the joints of the thumb.

In order to improve generalizability to yet unseen data samples, we further add (subtract) half the standard deviation of each feature

to (from) the calculated maximum (minimum) values for each hand shape (i.e. label

l). Since we have a normal distribution with unit variance (

) due to standardization, the calculation simplifies as follows:

Concretely, this results in minimum values with feature vector

and maximum values with feature vector

for each label

l. Here,

is the number of features, as shown in

Table 1. Using these limits, a new data sample

can then be generated for a specific label

l by sampling new feature values

from a uniform distribution

where

.

Even after applying Data Augmentation, the entire data set, including the augmented data, is scaled again as described at the beginning of the chapter.

3.3. Feature Selection

Each feature of a data sample holds a certain amount of information about the performed gesture. Some features may be more important than others. For example, the

DIP and

PIP joints, shown in

Figure 6, are interdependent in most of the gestures that were investigated here [

9]. Consequently, only one of these features holds significant information about the performed gesture. This is in contrast to any of the thumbs’ features, as the exact position of the thumb plays an important role in many of gestures that were examined in this work. So in general, many of the

DIP or

PIP features hold very little information about the performed gesture, while other features, such as that of the thumb, are more important for the classification.

Figure 6.

Joints and bones of the human hand [

25].

Figure 6.

Joints and bones of the human hand [

25].

Feature Selection takes advantage of that and tries to keep the most important features, while also removing features that hold very little information. That way fewer features are used to represent a single gesture, meaning the data takes up less space and the ml models can focus on the most important data [

26].

In this work, we used the Genetic Algorithm (GA) for

Feature Selection. The algorithm is loosely based on the theory of evolution and consists of an initialization phase and four repeating phases after that:

6 i) At first, multiple bitstrings are randomly created (initialization). Each bit corresponds to a single feature that is either kept (1) or discarded (0). For each of these bitstrings one ML model is created and trained with the corresponding features.

ii) Afterwards, some of these models are selected for the next phase of the algorithm. Models with high accuracy often have a higher chance to be selected by the algorithm. iii) The remaining bitstrings are combined to form new combinations of features.

iv) These may randomly flip single bits (=

mutation). The resulting bitstrings are used to train new models. The whole process is repeated until either a predefined number of iterations is reached or there has not been a significant accuracy improvement for multiple iterations [

27].

The algorithm has also been used in related work, such as Li

et al. [

28], to reduce the training error alongside the number of epochs of a neural network, when classifying ten gestures. Without GA, a training error of about 0.00566 was reached after 5000 epochs. Using GA, the error was reduced to about 0.00042. Using a handcrafted modification of the GA reduced the error to about 0.00010 after just 608 epochs.

4. Machine Learning Classification

Building on the results of Achenbach

et al. [

11], we chose the classifiers Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Logistic Regression (LR) for our investigations, as they were able to achieve the highest accuracy values in a similar experiment. We added a Voting Meta-Classifier (VL2) to combine the advantages of all these classifiers. In comparison, we are now using different hardware and a larger number of gestures: Achenbach

et al. [

11] examine five gestures with 15 features of hand shape and 25 gestures with the same 15 features of hand shape plus four additional features for hand orientation. In this work, we examine 27 and 56 gestures with 20 features of hand shape.

In the following, we briefly present the rough working of each classifier and explain the conditions under which we used them.

4.1. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

SVMs are used to split data into two classes. This is achieved by mapping the data into a vector space and looking for a linear hyperplane that separates the data according to the max-margin paradigm. This generally results in less overfitting and more robustness when classifying unseen data. Projecting the data into a higher dimensional vector space, finding a linear hyperplane there and projecting the data and hyperplane back into the original vector space can transform the hyperplane from a linear function to one of a higher complexity. This procedure is used to classify data that is not linearly separable. In practice the so called

kernel trick is often used instead of transforming the entire vector space to safe computing time [

29].

Following this procedure, a single SVM can differentiate between two classes. However, most classification problems contain more than just two output classes. In multi-class classification problems, more than one SVM has to be used to separate the data. There are two commonly used methods to train these SVMs. In the

One-versus-One (OvO) approach, one SVM is created for every pair of classes. The final decision is often found by performing a majority vote over all SVMs. In the other method,

One-versus-All (OvA), a single SVM is trained for each class and is used to distinguish between that class and all the other classes. The final output is usually provided by the SVM with the highest confidence score [

30]. In this work, we used the OvO approach to classify all of our data.

4.2. Random Forest (RF)

A RF uses the results of multiple Decision Trees (DTs) to calculate its own prediction. A single DT within a RF often performs worse than a full-fledged DT. This is because a single tree inside a RF is usually trained on a small subset of the data and its features. The subset is generated by sub-sampling the original training data with replacement [

29]. It is important to have different subsets for most of the trees. The idea is to train a large number of diverse DTs. Each one may heavily focus on one part of the training data, while neglecting other parts. Thus being worse than a DT trained with all the available data [

31]. However, their results are then combined, often by a majority vote. Together they usually perform better than a single DT, while overfitting less and thus generalizing better.

It has been shown that RFs do not overfit by increasing the number of trees [

31]. Hundreds or thousands of trees are often trained, when using RFs. One advantage of training so many classifiers is that they can also be used to analyse the data. For example, adding noise to a single feature and observing the change in accuracy of all DTs can be an indication of the importance of that specific feature [

29]. The large number of classifiers ensures that a higher error rate is actually caused by the random noise added to the feature and not by a specific characteristic of a single classifier.

4.3. Logistic Regression (LR)

In the most basic case of LR, the model has to distinguish between two output classes. In this case, LR calculates the probability of a sample belonging to one of the two output classes. If the calculated value exceeds 50%, the sample is assigned to that class. Otherwise the other output class is chosen. Probabilities close to either

or

are often desirable because the model is sure about assigning the corresponding sample to one of the two classes in these cases. Probabilities close to

are very susceptible to small amounts of noise. The probability is often calculated using the

logit function [

32],

where

represent the features of the data. The

are weights that must be calculated when fitting the model. The resulting function usually follows the shape of a sigmoid. In general, a steeper slope leads to better predictions as there are fewer inputs with probabilities close to

this way.

When classifying more than two classes, LR uses a similar strategy than what was presented in

Section 4.1. Because of higher training times when using large amounts of data, most of the time the OvA approach is used for LR instead of OvO.

4.4. Voting Meta-Classifier (VL2)

A meta-classifier is a model that does not operate on the input data alone. It uses other models to improve its own predictions. That way the entire system becomes more resistant to failures of individual models or sensors, as well as noise in the data [

33]. Such models are often organized in layers. The voting classifier used in this work consists of two layers. The three classifiers presented in this chapter form the first layer. These models use the input data to predict the output class. The second layer is the voting classifier itself. It combines the predicted probabilities of the models in the previous layer to produce its own output based on the argmax of their sums. A weighted average, where the weights are based on the grid search results of the classifiers in the first layer, produced the best results.

5. Experiment

In an experiment [

15], different hand shapes used in

ASL-Lex lexical database

7 and asl manual alphabet (including digits) were recorded with a

Manus Prime X data glove. We examine two different data sets in this paper:

-

ASL manual alphabet

consists of 26 different hand gestures with 21 different hand shapes. To represent the digits 0-9 as well, six more hand shapes were added. This leads us to 27 hand shapes with which fingerspelling is possible, i.e. the possibility to spell names and numbers.

-

ASL-Lex

uses 58 different hand shapes for the dominant hand. For reasons we cannot explain, the hand shapes

Flat H and

Flat N are displayed identically

8 by ASL-Lex and cannot be distinguished. We therefore combine them and refer to them as

Flat N. As already mentioned, the letters of the finger alphabet

P and

K also share the same hand shape

9 and differ only in their orientation. We therefore have only considered

K. So we have a total of 56 unique hand shapes, which (together with other details such as movement or orientation of the hand) allow a vocabulary of more than 2,700 characters.

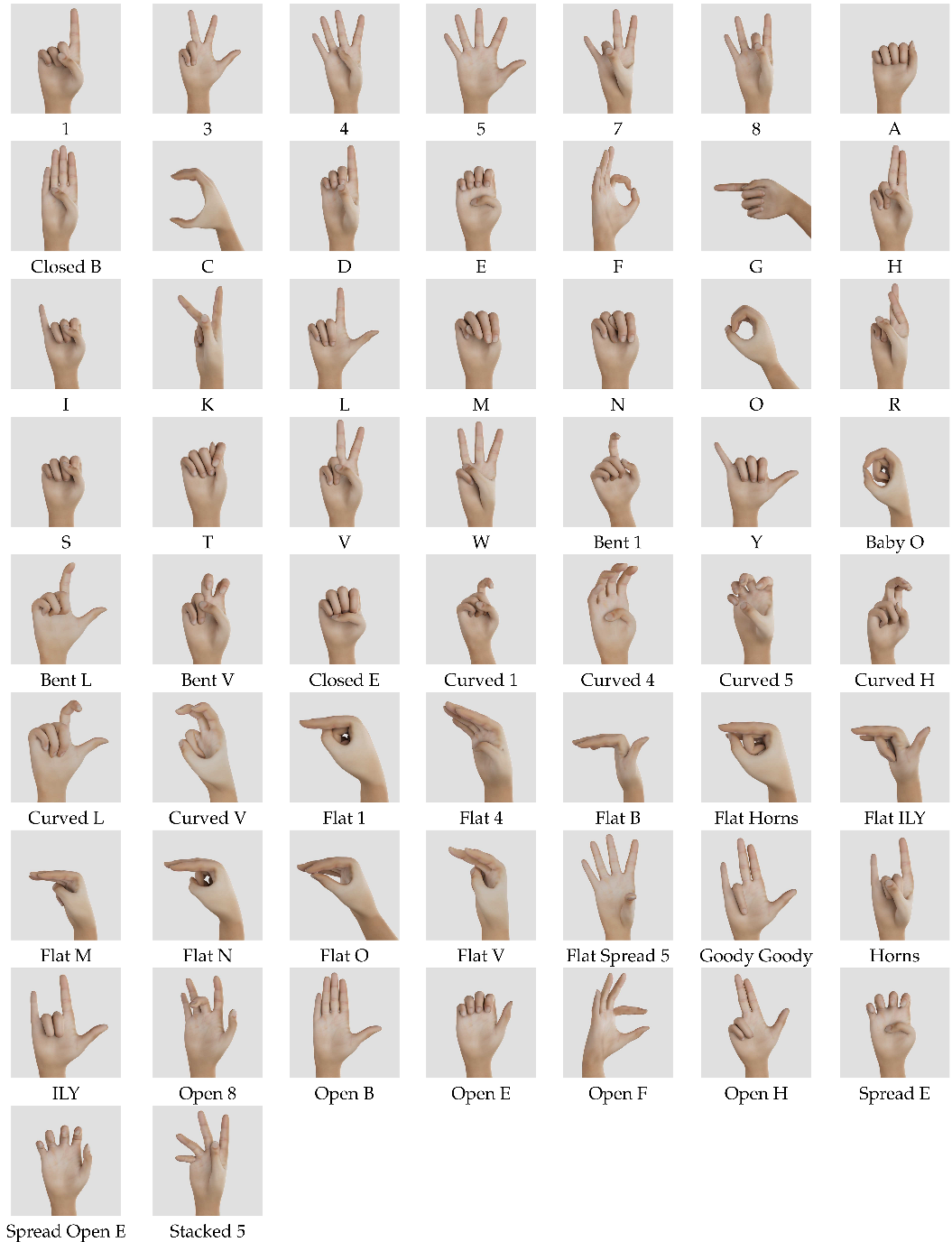

All hand shapes from the ASL manual alphabet are found in the set of hand shapes of

ASL-Lex, with the exception of the hand shape

M and

N. Therefore, we have a total set of 58 hand shapes, which are shown in

Table A1.

Since the focus of this work is on hand shape recognition, all recorded hand gestures are static, differ only by hand shape, and are independent of hand orientation. Therefore, all stretch and spread values from

Table 1 are used as features. The quaternions of the individual fingers are not considered due to their dependence on orientation.

5.1. Data Acquisition

For data acquisition a total of 20 participants took part in the experiment [

15]. The experiment was conducted as follows:

To allow for better hand mobility, the vibration motors on the gloves were removed. Prior to each experiment, the gloves were recalibrated using the associated software of Manus Core SDK to clean up any possible drift in the IMU sensors and to ensure that different hand sizes of the participants did not affect the results.

After calibration, each participant sat at a table and was shown a picture of the hand movement to be performed. Pressing the Enter key started the recording. The participant now had three seconds to perform the hand gesture and then held it for an additional two seconds. In a later segmentation, the static hand shape was then extracted as one keyframe from the middle of this second section.

After recording, participants were asked to return their hands to the starting position and place them on the table. This process was repeated three times for each hand gesture. Throughout the experiment, participants were under observation to ensure that the hand gestures were performed correctly. Incorrect recordings were repeated at the end of the experiment.

Thus, for each of the 58 hand gestures we used, three repetitions were recorded by 20 participants, yielding a total of 3,480 samples.

5.2. Hyperparameters

To find suitable hyperparameters for our hand shape recognition system, we first performed a pre-grid search with ten-fold cross-validation over all recorded samples for both data sets and each combination of our data preprocessing methods. The hyperparameters were searched in the same areas as Achenbach et al. [

11] already used. In this way, we were able to determine 16 different configurations of hyperparameters. From these, we have now defined a smaller, but more precise range, which can be viewed in

Table 2. This range will be used in each run of our following experiments with a five-fold cross-validation grid search.

To save computational resources, we performed the grid search based on the successive halving algorithm and used sklearn’s

HalvingGridSearchCV10. This algorithm allocates resources dynamically and favors the most promising hyperparameter configuration. Starting with an equal distribution of resources, the grid search therefore iteratively excludes hyperparameter combinations that are considered to be the least effective. Overall, this leads to considerable time savings in the search for the best hyperparameter configuration.

5.3. Hardware

An

Apple MacBook Pro11 (16", 2021) with

Apple M1 Max processor (10-core CPU with 8 performance cores and 2 efficiency cores, 32-core GPU, 16-core neural engine, and 400 GB/s memory bandwidth) and 32 GB Ram was used to compute the results presented here. The Python library scikit-learn

12 (version 1.2.1) and Python (version 3.9.6) were used.

6. Results

The four classifiers were evaluated using a Leave-One-Out cross-validation, i.e., training and test data were separated such that one participant’s data was used as test data and all other data were used as training data. In this way, all possible combinations were iterated, i.e., 20 repetitions for participants. To compare the performance of the classifiers, the accuracy and time for classification were stored and evaluated. Mean and standard deviation were calculated from the data thus obtained. Since we have an equal class distribution and prioritize each class equally, we omitted other measures such as the F-score.

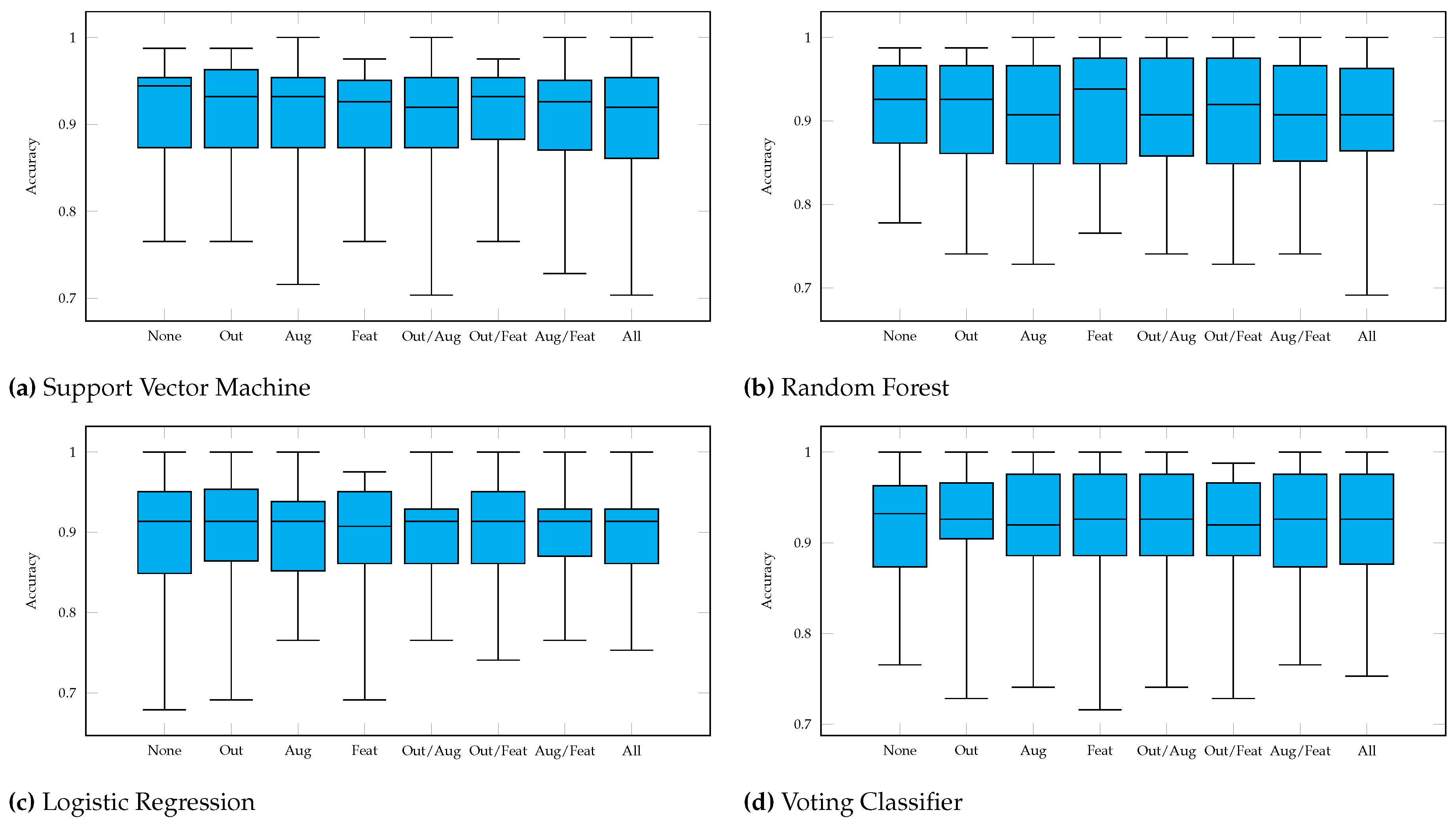

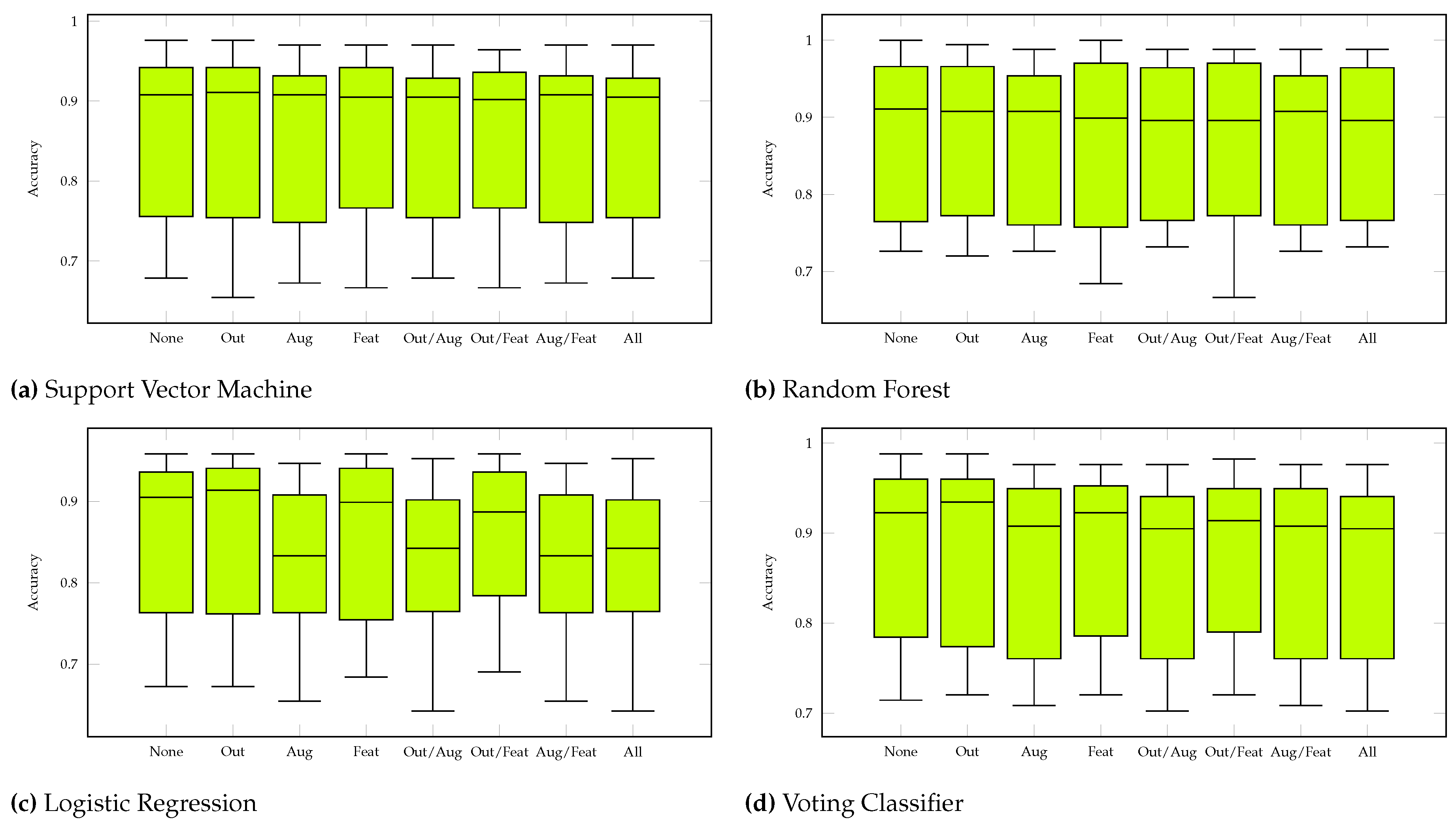

Table 3 and

Table 4 show the accuracy values of all classifiers with respect to the data preprocessing methods used. The best results for each classifier and data preprocessing configuration are marked in green, the worst results are marked in red.

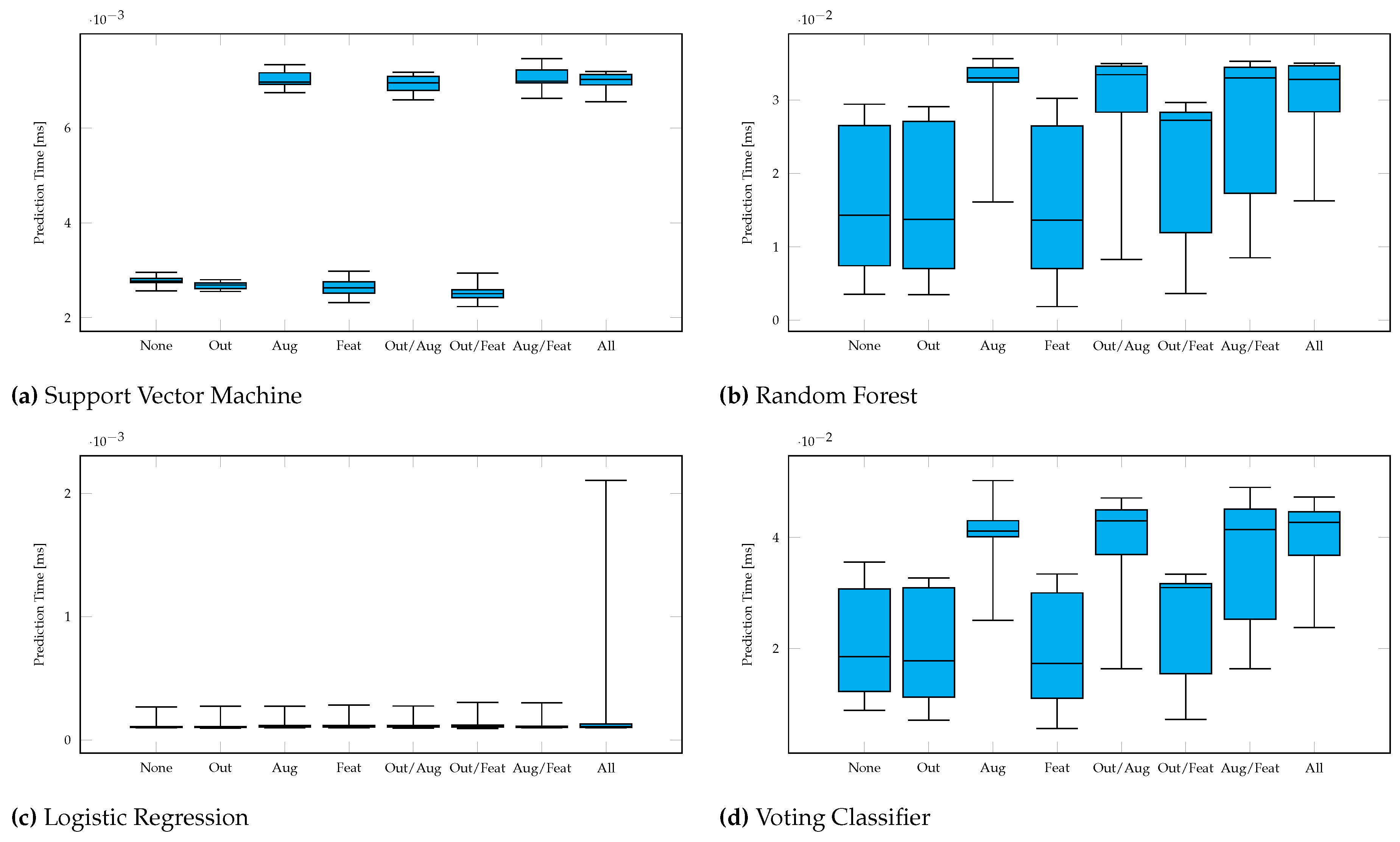

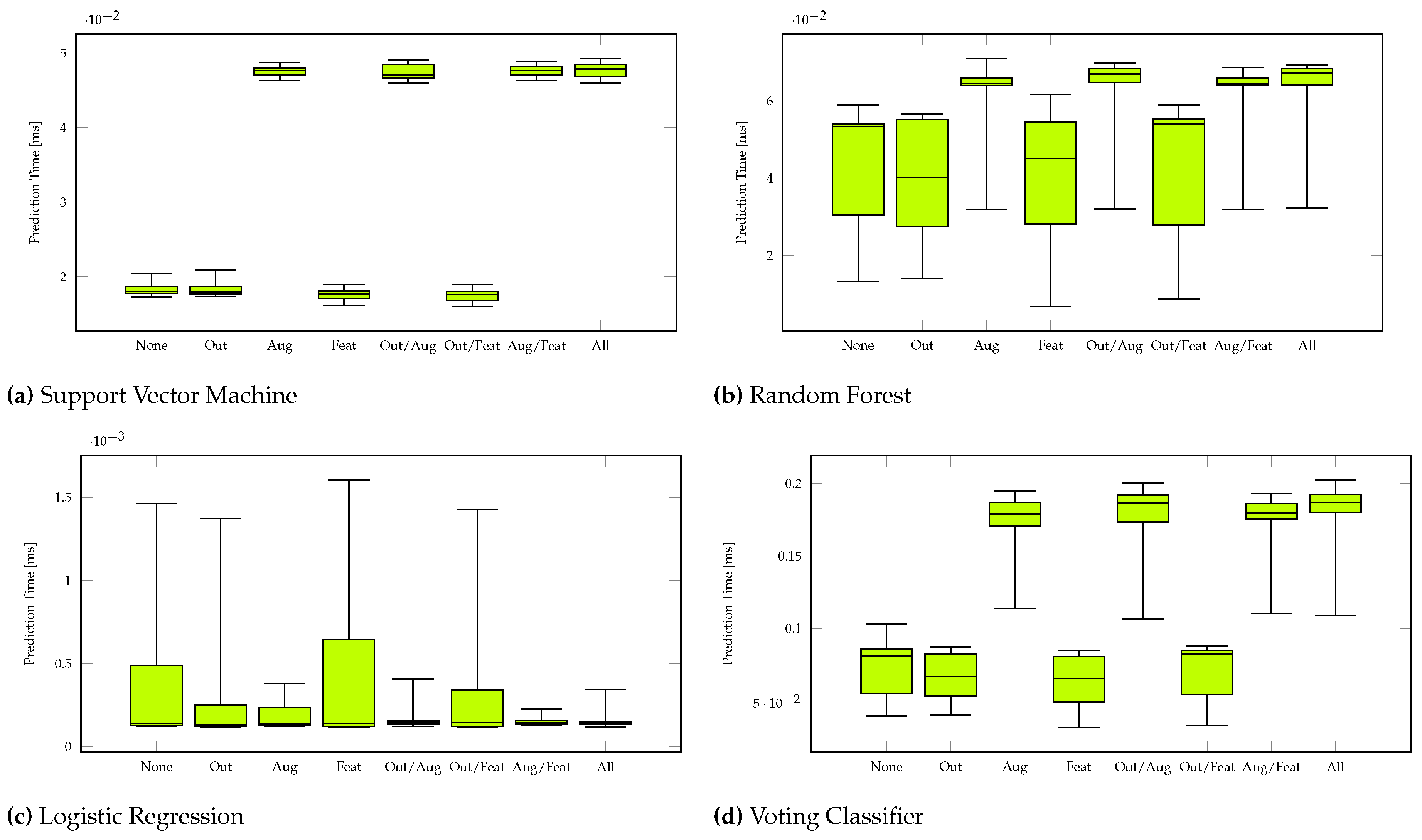

Figure A1 to

Figure A4 show the plotted metrics of the classifiers with different data preprocessing steps. The black lines mark the range where the metrics of each run can be found (maximum, mean, and minimum). The colored boxes represent the values of the first through third quartiles. So, inside a box there are 50% of the determined values from each of the 20 runs.

Independent of the used data preprocessing methods, 27 hand shapes can be classified with an accuracy of to and 56 hand shapes score to . In both cases, LR performs worst on average. For 27 hand shapes VL2 can achieve the highest average accuracy values, for 56 hand shapes RF performs best. Regardless of the number of hand shapes, there are only 0.51 to 2.53 percentage points between the best and worst feature combinations for each classifier, with the range varying significantly more for 56 hand shapes.

The classification time is the time difference immediately before and after calling the classifiers’

predict13 function. It includes the classification of an entire user data set, i.e. up to 168 samples (up to 56 hand shapes with three repetitions) before

Outlier Detection. In case of VL2 classifier, the classification time of the first layer classifiers are included.

Table 5 and

Table 6 show the classification times of all classifiers with respect to the data preprocessing methods used. Again, the best results are marked in green, the worst results are marked in red.

In contrast to the accuracy values, the classification times vary considerably: LR is by far the fastest classifier with times below , whereas VL2 understandably takes the longest with for 27 hand shapes and for 56 hand shapes, as it contains its own classification in addition to the three other classifiers. It is obvious that the classification times also increase sharply with the number of hand shapes. This affects LR the least (mean 2-fold increase in classification time) and SVM the most (mean 8-fold increase in classification time) for the difference from 27 to 56 hand shapes. When doubling the data using Data Augmentation, the times also roughly double.

6.1. Machine Learning Classifier

We will now briefly look at the results of the individual ml classifiers before taking a closer look at the data preprocessing methods.

-

Support Vector Machine (SVM)

-

showed a robust performance in classifying both data sets. For 27 hand shapes, SVM achieved an average accuracy of 90.46%, while for the more extensive data set with 56 hand shapes, the accuracy dropped slightly to 85.46%. These results suggest a marginal decline in SVM’s efficacy with increasing data complexity.

In terms of classification time, SVM took between and to classify the smaller data set and to classify the larger one, indicating good scalability.

-

Random Forest (RF)

offers comparable accuracy to SVM, with an average of 90.52% for 27 hand shapes and 86.79% for 56 hand shapes. However, the longer classification times ( for 27 hand shapes and for 56 hand shapes) could be a disadvantage in practical applications.

-

Logistic Regression (LR)

-

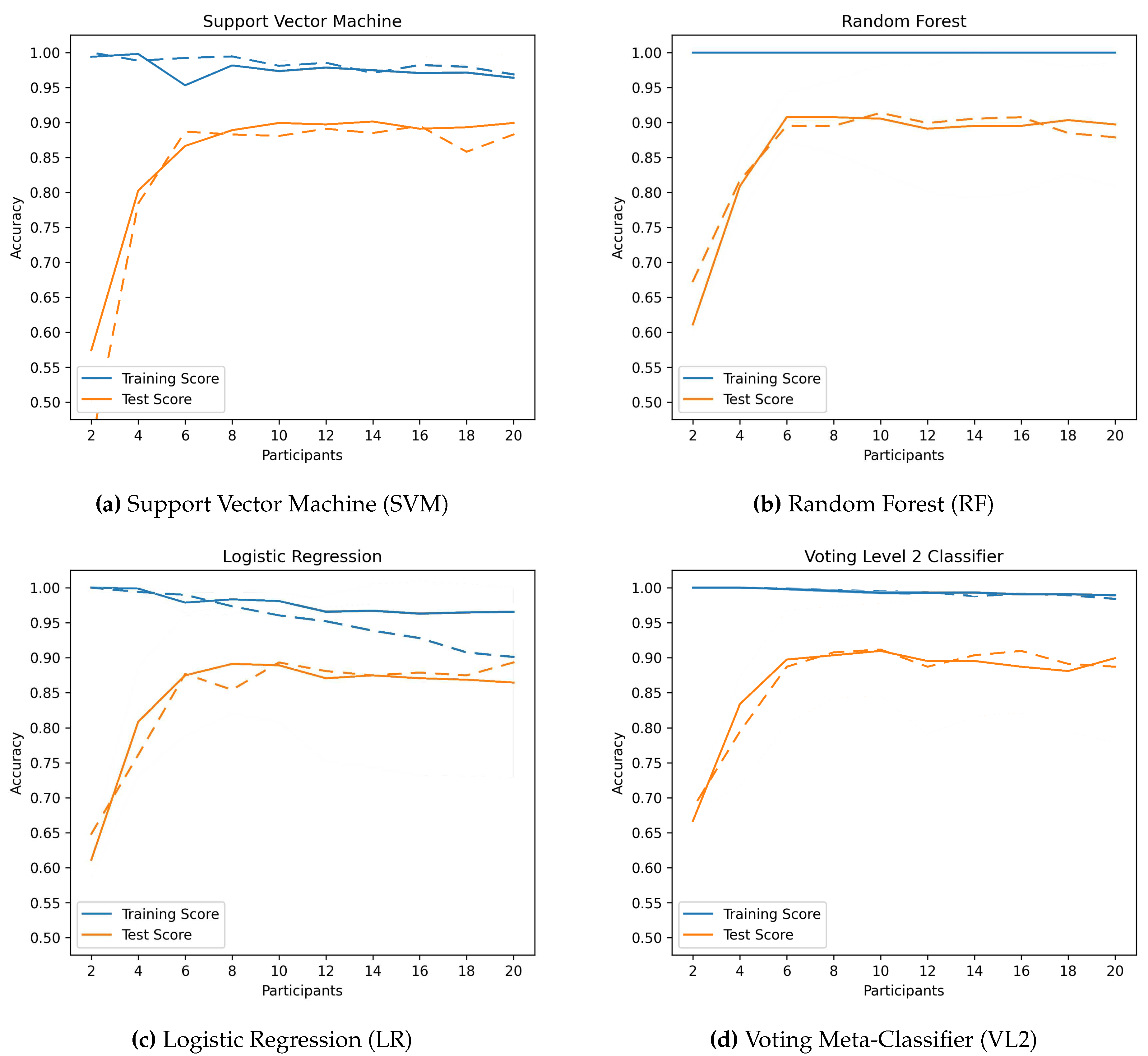

showed slightly lower accuracy, especially for the larger data set (average 89.58% for 27 hand shapes vs. 84.19% for 56 hand shapes). It can be seen that LR suffers a significant loss of accuracy (

) when

Data Augmentation is applied to a larger data set. When looking at the learning curves in

Figure 10c, it can also be seen how the accuracy decreases as the number of samples increases. It therefore appears that LR has problems with scalability.

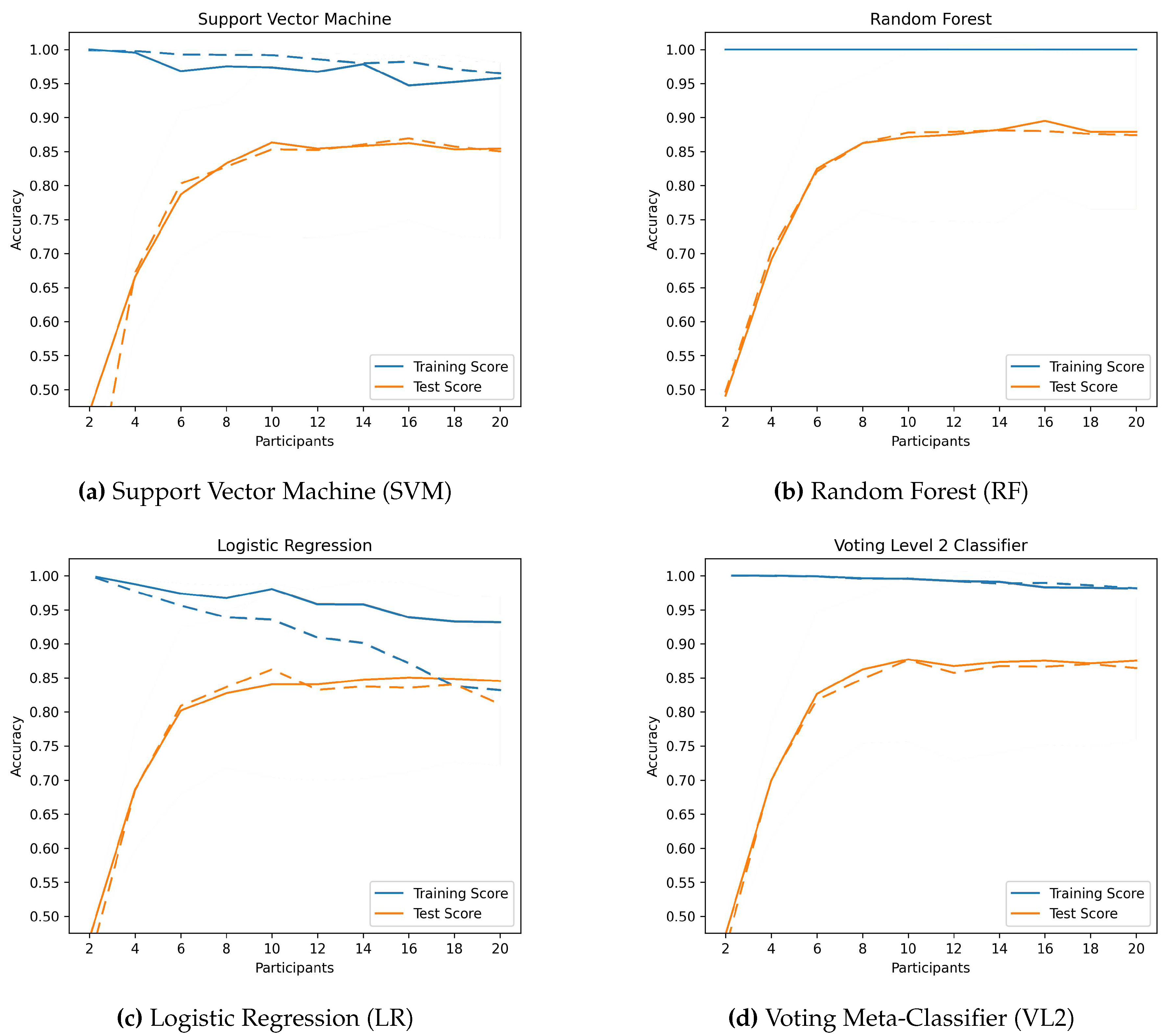

Figure 7.

Learning curves with (dashed line) and without (solid line) Data Augmentation for 27 hand shapes.

Figure 7.

Learning curves with (dashed line) and without (solid line) Data Augmentation for 27 hand shapes.

Classification times were the shortest among all classifiers tested, which could make LR an attractive choice for very time-constrained applications, as long as the amount of data is not too high. Regardless of the number of classes, the classification times are below

, but are also the most dependent on processor runtime fluctuations due to these short runtimes. This can also be well recognized in

Figure A3c and

Figure A4c. Therefore, comparisons of the classification time for LR should be treated with caution.

-

Voting Meta-Classifier (VL2)

-

consistently achieved the highest average accuracy in both data sets (91.50% for 27 hand shapes and 86.59% for 56 hand shapes), if the results for procedures with Data Augmentation in the larger data set were omitted. It seems that the poor scalability of LR affects the accuracy of VL2.

Classification times were also the longest ( for 27 hand shapes and for 56 hand shapes), which may limit its practical applicability in time-critical environments, because it contains all other classifiers on the first layer and additionally its own meta-classification takes place on the second layer.

6.2. Data preprocessing methods

Considering the results with respect to the selected data preprocessing methods, it can be said that, with few exceptions, the highest accuracy values are achieved without data preprocessing (except scaling). Occasionally, some combinations of data preprocessing steps and classifiers (e.g. LR with Feature Selection and Data Augmentation for 56 hand shapes) can achieve higher accuracy values, but since the differences are minimal and no real pattern can be recognized, these exceptions are probably due to the choice of hyperparameters. Only VL2 with Outlier Detection shows better accuracy for both 27 and 56 hand shapes compared to VL2 without data preprocessing.

According to

Figure A2, the data preprocessing methods for 56 hand shapes and SVM almost all have the same mean, whereas the greatest fluctuations occur for LR. There, the approaches with

Data Augmentation are significantly worse than without. For 27 hand shapes (see

Figure A1), the fluctuations are lower for all classifiers.

We tested 64 different configurations of data preprocessing (see

Table 3 and

Table 4). Eight configurations used no data preprocessing, while 56 used a combination of the methods described so far. Our tests have shown that only seven of these combinations perform better in terms of accuracy than the runs without data preprocessing.

Feature Selection, Outlier Detection and the combination of both lead to improvements in classification times in most cases. The times for LR are difficult to evaluate here, as they are very low and are therefore strongly influenced by runtime fluctuations. Data Augmentation roughly doubles the classification time when doubling the data.

6.2.1. Outlier Detection

Regarding the Outlier Detection, we found that detecting only very few outliers yielded the best results. Consequently, we set the the maximal distance one point is allowed to have to the closest point within the cluster to one standard deviation per feature on average. With 20 features, this resulted in an eps value of 4.4. The minPoints parameter was set to 51, as there were a total of 57 samples for each gesture in the training set and we figured that at least 90% of the data should be inliers. These parameters resulted in an average of 3.25 out 1539 samples being considered outliers in the 27 gestures data set. For 56 gestures, an average of 5.8 outliers were found in 3192 samples.

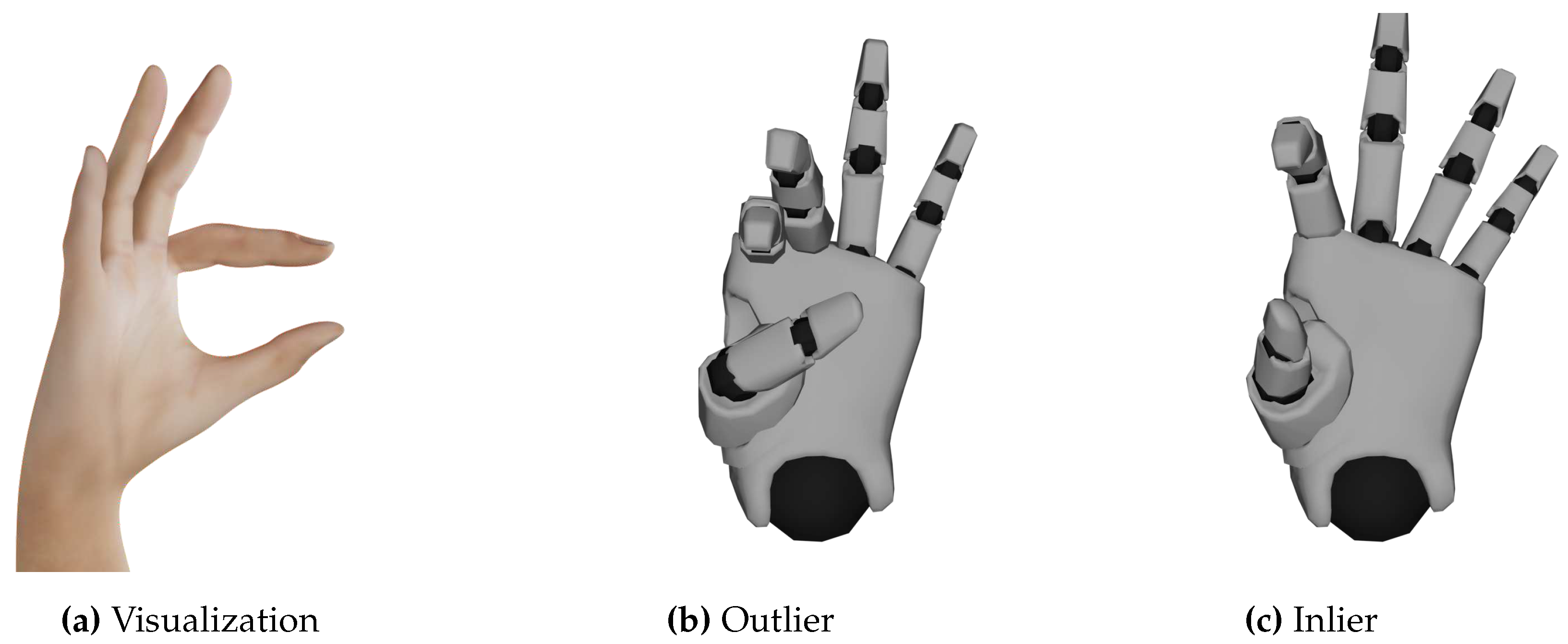

One example of an outlier alongside an inlier and the visualization of the gesture

Open F can be seen in

Figure 8. The outlier was created by bending the thumb and middle finger too much.

About 0.78% of all samples were identified as outliers, which slightly improved performance in three of eight cases, as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. More importantly, classification time improved in six out of eight cases, as seen in

Table 5 and

Table 6. This leads to a recommendation to use

Outlier Detection in time-critical applications.

6.2.2. Data Augmentation

The effect of the applied

Data Augmentation method can best be seen in

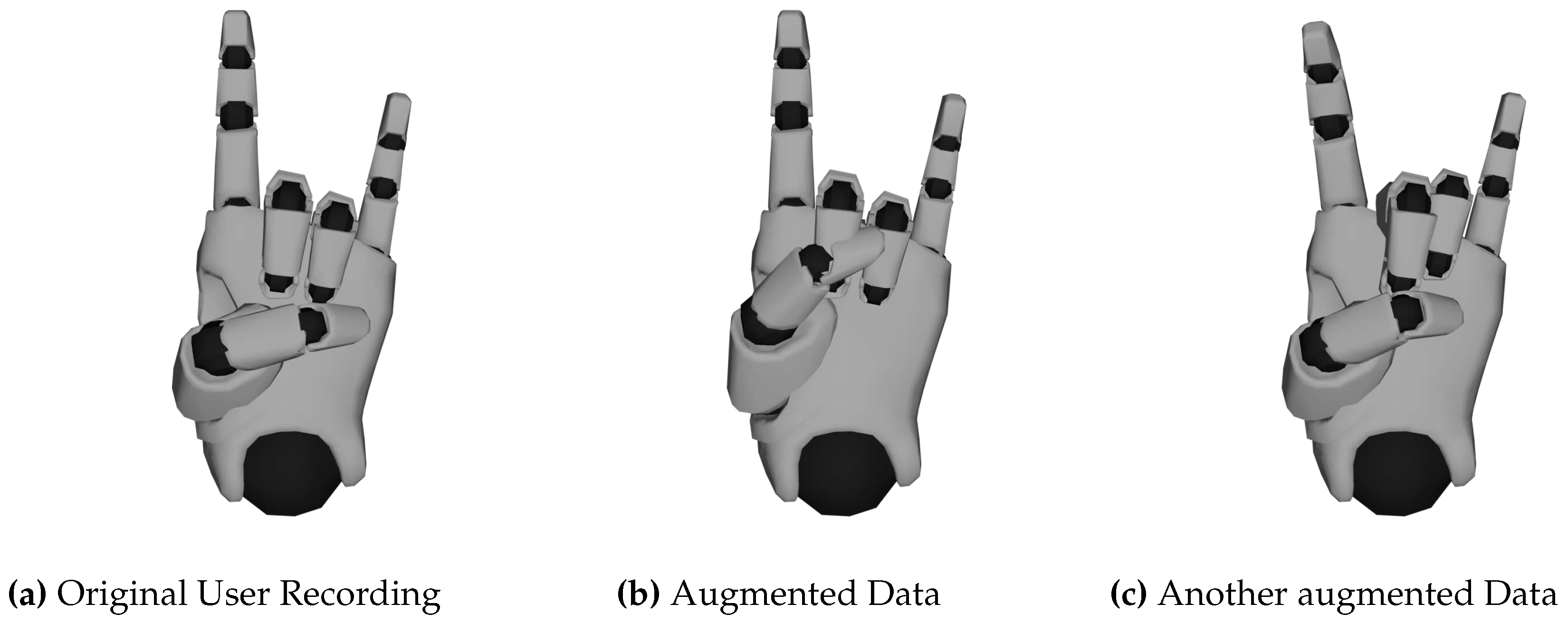

Figure 9, where the result is visualized. Here, two synthetically generated hand shapes for the

Horns label are shown as an example, along with an original sample for comparison. As can be seen, new data samples can be successfully generated and show some variations in the way the hand shape is performed. Overall, we have doubled our training data set using this technique.

As can seen in

Table 3 and

Table 4, the experimental application of

Data Augmentation failed to improve the accuracy further, especially with the larger data set. The reason could be that the collected data is sufficient for the chosen classifiers and does therefore not further improve classification accuracy. As the number of data samples increases, the classification time also increases. To evaluate whether better generalizability can be achieved with

Data Augmentation, we created and compared learning curves: We plotted the accuracy obtained without

Data Augmentation as a function of the number of participants, i.e., the number and variety of available training data, and compared it with the results when

Data Augmentation is applied.

Figure 7 and

Figure 10 show these learning curves. When the data is not augmented, the curves already show a good fit, with accuracy on the test set increasing steadily with the number of participants. The

generalization gap, i.e. the gap between the two curves, is also clearly visible. Just LR shows a significant decrease in training accuracy as the number of data increases (whether due to a larger data set or the use of

Data Augmention).

The generalizability can therefore not be increased by augmenting the data, as they already have a high generalizability with the exception of LR.

Overall, we were able to successfully generate valid synthetic data samples to enrich our training set. For the reasons stated above, the application of the

Data Augmentation method is altogether not worth applying in this context and for this type of data. As mentioned in

Section 3.2, research on

Data Augmentation for wearable sensors has mainly been studied in a dynamic context, where models trained with this more complex type of data benefit more from artificial augmentation of the data set. The application of

Data Augmentation would therefore be more effective for dynamic gestures and would probably achieve a better effect on accuracy in the area of

Deep Learning, as these methods perform significantly better with a large amount of data than the traditional ml methods [

34].

6.2.3. Feature Selection

Feature Selection was used for data preprocessing in a total of four configurations. When applied to both data sets with 20 runs per experiment, we obtain 160 executions. The amount of times each feature was discarded by the algorithm can be seen in

Table 7. There were no features discarded in 50 out of 160 runs. The maximum number of discarded features was six (five times in 160 runs). On average 2.069 features were discarded per run.

Figure 10.

Learning curves with (dashed line) and without (solid line) Data Augmentation for 56 hand shapes.

Figure 10.

Learning curves with (dashed line) and without (solid line) Data Augmentation for 56 hand shapes.

According to the

Table 7, the thumb, index finger and middle finger seem to be the most important for classification. As, for example, no thumb stretch features were discarded at all, but the thumb spread feature was discarded more than every fourth time. Features of the index finger were discarded the least, and if so, then only the values of the upper extremities (dip and pip stretch features). For the middle finger, each of the four features was discarded at least three times, but the total number of discarded features is lower than for the thumb. The ring- and little finger seem to contribute the least amount of information needed to classify gestures, as their features were discarded most often.

It is important to note that the stretch mcp value was always preserved for almost all fingers, while the pip and dip values were frequently discarded. In most cases, only one of the latter two joints was discarded, while the other was kept for classification. After investigation this phenomenon further, we noticed that these two joints are rarely moved individually. For most gestures, both joints are a flexed to about the same degree. Looking at our data, we also noticed that the value of these two joints is often exactly the same, explaining why one of these two joints for each finger was discarded by our feature selection so often. Anatomically, it is not possible to move the upper phalanx (= dip) independently of the middle phalanx (= pip) without external influence [

9]. This dependence explains why so many values are filtered out here.

Another noteworthy observation is that the ring finger spread value was the most frequently discarded feature and was discarded in more than 40% of all runs. This is likely due to the Ring finger barely moving along this axis in most gestures. For example, when spreading your fingers, the ring finger barely moves, while the spread value of all other fingers changes significantly. As the ring finger mainly has a supporting function, its mobility is limited compared to the other fingers. In most cases, the ring finger is used together with its neighboring fingers and therefore exhibits a strong dependence on them. This dependency was obviously recognized by our Feature Selection.

Overall, it can be said that Feature Selection was able to achieve an improvement in classification time with a slight decrease in accuracy. On the other hand, we were able to prove that Feature Selection comprehensibly identified and filtered dependent values. The approach would probably bring even more time advantages if more than 20 features were used for classification.

7. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of various ml classifiers and data preprocessing techniques in recognizing hand shapes of asl. Our focus was not only on achieving high accuracy but also on ensuring real-time applicability. The choice of the most suitable classifier and preprocessing method requires a careful consideration of both accuracy and classification time. The training time is not relevant for our purposes, since the training is performed offline and is not time-critical.

7.1. Key Findings

-

Accuracy vs. Classification Time Trade-off:

VL2 achieved the highest accuracy, but was also the slowest, making its use in real-time applications a careful consideration. In contrast, LR offered the best speed but lowest accuracy ( percentage points less than VL2). RF and SVM are somewhere in between.

-

Impact of Data Preprocessing:

Data preprocessing techniques such as Feature Selection and Outlier Detection improved the efficiency of classifiers in terms of classification time, but often at the cost of a slight decrease in accuracy. The particular benefit of Data Augmentation could not be proven, instead it has provided poorer accuracy values and higher classification times.

7.2. Optimal Classifier for Real-Time Application

In general, the accuracy values achieved are at a comparable level for all classifiers. Since VL2 can almost exclusively achieve the highest accuracy values by combining the advantages of the other classifiers, it is very suitable for our purpose. The high classification time is slightly relativized when considering that in a real-time scenario usually only one hand shape has to be recognized at a time. In our case, the classification time was given for the classification of 82 and 168 hand shapes, respectively, before applying Outlier Detection.

VL2 achieves an average classification time of for 27 hand shapes and for 56 hand shapes for data preprocessing without Data Augmentation. If we assume an approximately proportional ratio of classification time to the number of data to be classified, this results in a classification time of approximately or for a single hand shape to be classified. Theoretically, classification rates of over would be possible, i.e. far more than the sampling rate supported by the data glove used in this work. It can therefore be assumed that a high classification rate for single hand shapes can be achieved even when using hardware that is not as performant as we had available.

Regarding data preprocessing, the use of Outlier Detection is recommended, as this leads to improvements especially in classification times and, when used with VL2, also to improvements in accuracy. Feature Selection has brought slight improvements in classification time, but these advantages do not add up to those of Outlier Detection, which is why it does not necessarily make sense to use both methods at the same time. The experimental Data Augmentation approach showed no improvements.

Overall, we therefore consider the use of VL2 in conjunction with Outlier Detection to be the most useful for our purpose.

7.3. Limitations of Classification

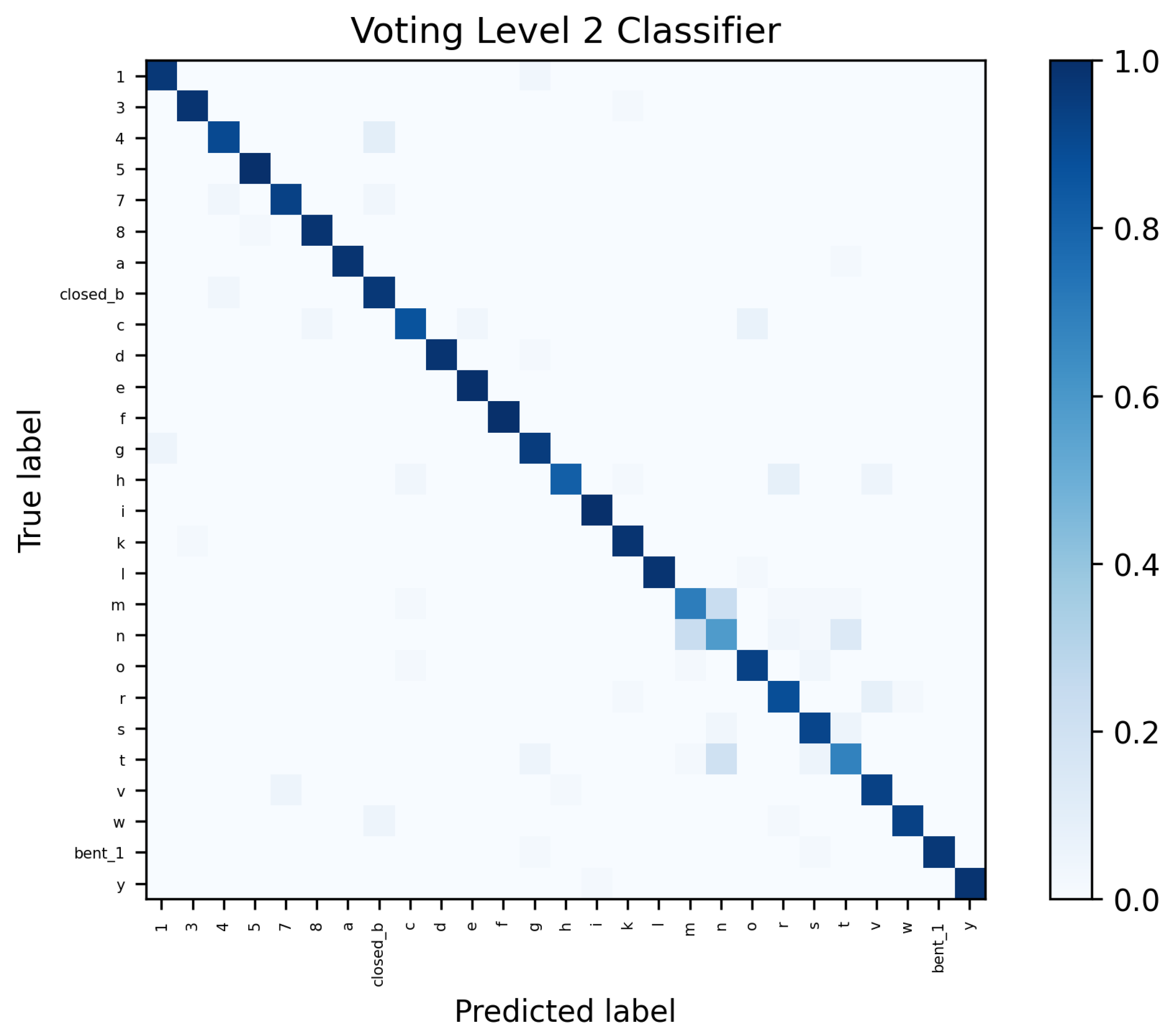

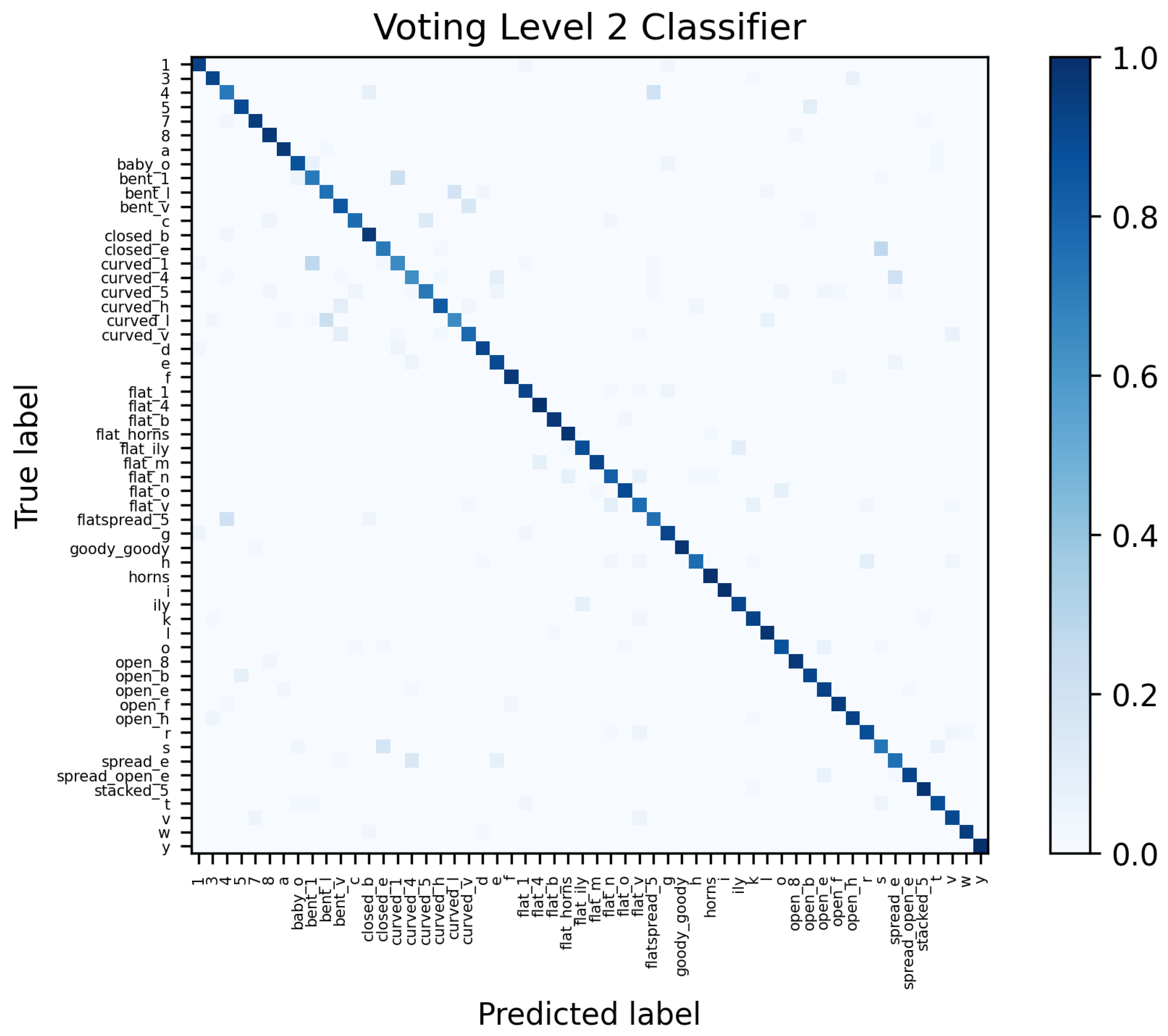

Looking at the confusions within the classification, see

Table 8 and

Table 9, it can be seen for which types of hand shapes there are difficulties in classification. The data acquisition was supervised, i.e. it was monitored whether the hand shapes were correctly executed during the recording. The listed errors are therefore mainly due to the data gloves or the classification methods.

- Thumb Position:

-

There are particular difficulties with the hand shapes M, N, and T, where a fist is formed and the thumb crosses a certain number of fingers below. Looking beyond the top 10, it can be seen that S is also often interchanged with the hand shapes just mentioned, because here the hand also forms a fist, but the thumb crosses the fingers at the top (and not at the bottom). Also, S is confused with Closed E, where the thumb does not rest on the fingers but directly below them.

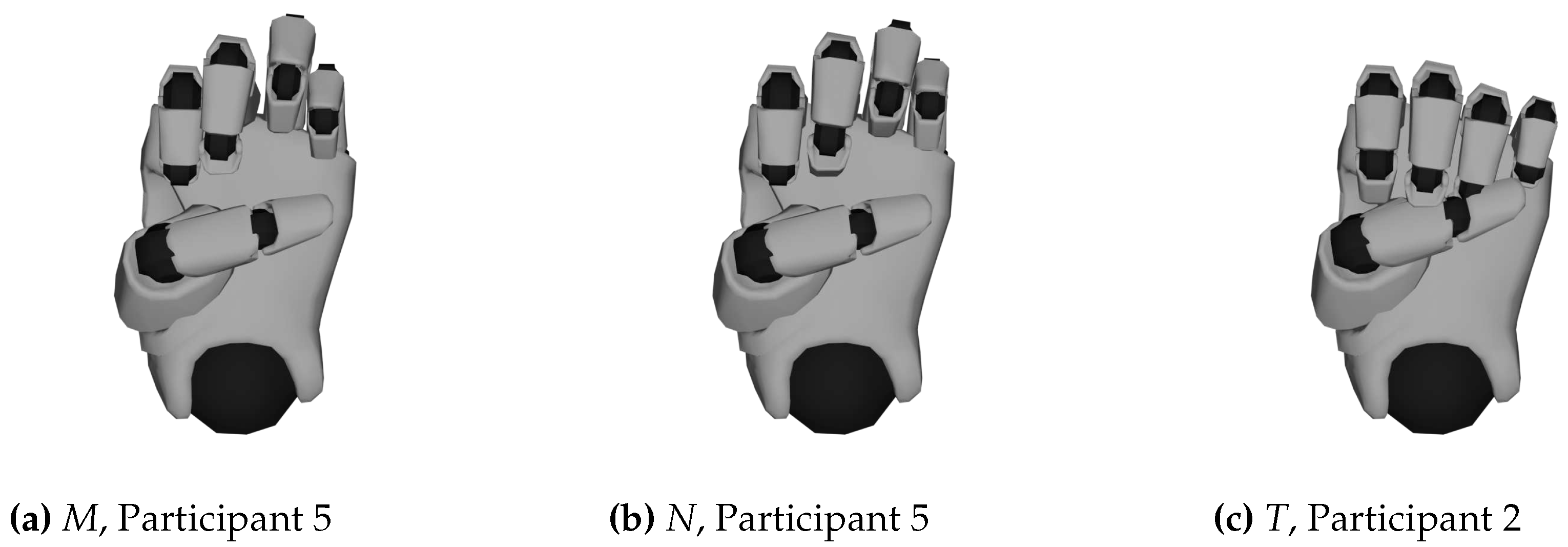

Upon closer inspection of the visualized data, it is noticeable that the position of the thumb is not recorded accurately enough by the data glove (examples can be seen in

Figure 11). This is generally a weakness with this glove and seems to be the case with other IMU controlled gloves [

11]. Similarly, it is difficult for the glove to tell whether the thumb is on top or underneath the crossed fingers.

The hand shapes Flat Spread 5 and 4 are also confused and differ only in the position of the thumb.

- Spread Values:

Another example where the classifiers had difficulties with recognition are the hand shapes

R,

H and

V already shown in

Figure 3, which differ only by the spread of the index finger and ring finger. The same applies to

4 and

Closed B.

- Stretch Values:

The classifiers also often had problems with stretch values, for example to distinguish between curved and bent hand shapes. Even though the recording of the hand shapes was monitored, it cannot be completely ruled out that the hand shapes were all recorded uniformly, as the difference between bent and curved is sometimes marginal. Examples are Curved L ⇔Bent L and Curved 1⇔Bent 1. The differences between the hand shapes Curved 4⇔Spread E and C⇔ O are more significant, but there have also been cases of confusion.

7.4. Comparison to Related Work

Pan et al. [

9] have published a state of the art paper on data gloves in 2023. They examined over 100 English-language papers from reputable publishers and created a comprehensive review that we use for comparison:

- Number of gestures:

One of their results shows that the papers validate at least three to a maximum of 31 hand gestures. The average for static gestures is 20 gestures. So in comparison, our paper is in the upper range or well above with 27 and 56 static hand gestures respectively.

- Number of participants:

For the number of participants and data recorded (samples), our work is right on the average of 20 participants and 1,000 to 10,000 samples (it has 1,620 and 3,360 samples, respectively, and double that if the data are augmented).

- Number of classifiers:

Most papers have examined between three and five classifiers; again, we are in the mean range with four classifiers examined. However, we examine eight different combinations of data preprocessing methods for each classifier.

Table 10 shows us an overview of related work [

9,

11,

13,

14]. Since most papers ([

10,

11,

12,

14]) report their results in a user-dependent manner, we conducted an additional experiment for this purpose. This means that a user’s data can appear in both the training and the test data. For better comparability, we therefore conducted another experiment for both data sets.

This time, randomly combined training and test data were examined in a ratio of 80 to 20. For this we used the VL2 with the already used hyperparameter ranges and with Outlier Detection, as this was the most promising approach, and trained and tested them 100 times. The training and testing data were randomized again before each run.

An accuracy of 95.55% was achieved for the data set with 27 hand shapes, and 93.19% for 56 hand shapes. Looking at the other classifiers, we see that they are at a similarly high level between 94.17% (LR) and 95.34% (rf) for 27 hand shapes and between 90.16% (LR) and 93.28% (rf) for 56 hand shapes. It should be noted here that RF can even achieve a slightly higher result than VL2 and that LR obviously scales poorly.

Comparable works, such as Pezzuoli et al.’s [

12], achieve an accuracy of up to 99.70% for 27 dynamic gestures, but also use five times as many features. These 96 features include information about hand orientation and movement.

Plawiak et al. [

10] use ten sensor values per frame to detect dynamic hand gestures, two of which are rejected using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). They interpolate the average of 60 frames of data to 20 frames, resulting in 160 data points, which they use to classify the 22 different hand gestures. While this gives them a higher accuracy of 98.32% than us (95.92% for 27 hand shapes), they also use eight times the amount of features for classification.

Achenbach et al. [

11] achieve a higher accuracy than we do with a comparable number of gestures (25 compared to 27) and features (19 compared to 20) with 99.50%, but they can also rely on information about the orientation of the hands, which we lack.

In direct comparison with the related work shown in

Table 10, we perform slightly worse with 27 hand shapes in terms of accuracy, but we can also rely on significantly less information, which generally has a positive effect on the classification times. With 56 hand shapes we can distinguish more than twice as many hand shapes as the related work and this with a still high accuracy.

8. Conclusions

In this work, the effects of different data preprocessing steps on the classification of 27 and 56 static hand shapes were investigated. The metrics considered were accuracy and the classification time.

According to our research, we can recommend the VL2 classifier with Outlier Detection, as it has a high accuracy with acceptable classification time. With this setting, 91.91% (27 hand shapes) and 87.50% (56 hand shapes) accuracy could be achieved for user-independent tests, with a classification time of less than and less than , respectively. In user-dependent tests, as much as 95.55% and 93.28% accuracy could be achieved. Comparable work with better accuracy values either had more information available to classify the data or was only able to distinguish significantly fewer classes. For very time-critical applications, LR with Outlier Detection can also be used, whose accuracy is slightly lower, but classification time is significantly higher. This recommendation is independent of the number of hand shapes to be classified.

The use of Feature Selection has brought a slight improvement in classification times, but this is not necessarily additive to the advantages of Outlier Detecion. With more features, the advantages of Feature Selection would certainly be greater. Our approach to Data Augmentation was able to double the number of training data with valid data, however, no improvement in accuracy or generalizability was observed. This is certainly due to the fact that we classified static gestures, whereas related work has pointed to noticeable improvements for dynamic gestures.

Future work will evaluate how the data preprocessing methods would behave with dynamic data with significantly more features. Especially improvements in Data Augmentation and Feature Selection could then be expected. Data Augmentation should lead to higher accuracy and better generalizability, whereas Feature Selection should lead to faster classification times.

The focus on real-time applicability limits the exploration of more computationally intensive, yet potentially more accurate, models like deep learning. These models may offer improved performance but require greater computational resources. This could also be taken into account in future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Philipp Achenbach, Sebastian Laux, Dennis Purdack, Philipp Müller and Stefan Göbel; Data curation, Philipp Achenbach, Sebastian Laux and Dennis Purdack; Formal analysis, Philipp Achenbach, Sebastian Laux, Dennis Purdack and Philipp Müller; Funding acquisition, Stefan Göbel; Investigation, Philipp Achenbach; Methodology, Philipp Achenbach, Sebastian Laux and Dennis Purdack; Project administration, Philipp Achenbach and Stefan Göbel; Resources, Philipp Achenbach; Software, Philipp Achenbach, Sebastian Laux and Dennis Purdack; Supervision, Philipp Achenbach and Stefan Göbel; Validation, Philipp Achenbach, Sebastian Laux, Dennis Purdack and Philipp Müller; Visualization, Philipp Achenbach, Sebastian Laux and Dennis Purdack; Writing – original draft, Philipp Achenbach, Sebastian Laux and Dennis Purdack; Writing – review & editing, Philipp Müller and Stefan Göbel.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACM |

Association for Computing Machinery |

| ASL |

American Sign Language |

| CMC |

Carpometacarpal |

| DBSCAN |

Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise |

| DIP |

Distal Interphalangea |

| DoF |

Degrees of Freedom |

| DT |

Decision Tree |

| GA |

Genetic Algorithm |

| IEEE |

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| IP |

Interphalangeal |

| IMU |

Inertial Measurement Unit |

| LR |

Logistic Regression |

| MCP |

Metacarpophalangeal |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| OvA |

One-versus-Al |

| OvO |

One-versus-One |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| PIP |

Proximal Interphalangeal |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| VL2 |

Voting Meta-Classifier |

| VR |

Virtual Reality |

| WoS |

Web of Science |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Used hand shapes of asl fingeralphabet (1 to Y) and ASL-Lex (all hand shapes except M and N).

Table A1.

Used hand shapes of asl fingeralphabet (1 to Y) and ASL-Lex (all hand shapes except M and N).

Figure A1.

Accuracy values in Leave-One-Out cross-validation for Classifiers with 27 Gestures (Outlier Detection, Feature Selection, Data Augmentation).

Figure A1.

Accuracy values in Leave-One-Out cross-validation for Classifiers with 27 Gestures (Outlier Detection, Feature Selection, Data Augmentation).

Figure A2.

Accuracy values in Leave-One-Out cross-validation for Classifiers with 56 Gestures (Outlier Detection, Feature Selection, Data Augmentation).

Figure A2.

Accuracy values in Leave-One-Out cross-validation for Classifiers with 56 Gestures (Outlier Detection, Feature Selection, Data Augmentation).

Figure A3.

Classification Times in Leave-One-Out cross-validation for Classifiers with 27 Gestures (Outlier Detection, Feature Selection, Data Augmentation).

Figure A3.

Classification Times in Leave-One-Out cross-validation for Classifiers with 27 Gestures (Outlier Detection, Feature Selection, Data Augmentation).

Figure A4.

Classification Times in Leave-One-Out cross-validation for Classifiers with 56 Gestures (Outlier Detection, Feature Selection, Data Augmentation).

Figure A4.

Classification Times in Leave-One-Out cross-validation for Classifiers with 56 Gestures (Outlier Detection, Feature Selection, Data Augmentation).

Figure A5.

Leave-One-Out cross-validation confusion matrix for 27 hand shapes and VL2 classifier with Outlier Detection.

Figure A5.

Leave-One-Out cross-validation confusion matrix for 27 hand shapes and VL2 classifier with Outlier Detection.

Figure A6.

Leave-One-Out cross-validation confusion matrix for 56 hand shapes and VL2 classifier with Outlier Detection.

Figure A6.

Leave-One-Out cross-validation confusion matrix for 56 hand shapes and VL2 classifier with Outlier Detection.

References

- World Health Organization. Deafness and hearing loss. Technical report; World Health Organization, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stokoe, W.C.; Casterline, D.C.; Croneberg, C.G. A dictionary of American Sign Language on linguistic principles; Linstok Press, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Stokoe, W. Sign language structure. 1978; Linstok Press: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, P.; Göksu, Y.; Kullmann, T.; Tregel, T.; Göbel, S. Towards handshape identification for automatic gesture recognition using sign notation systems. 8th European Conference on Social Media (ECSM ’21) 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sehyr, Z.S.; Caselli, N.; Cohen-Goldberg, A.M.; Emmorey, K. The ASL-LEX 2.0 Project: A Database of Lexical and Phonological Properties for 2,723 Signs in American Sign Language. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 2021, 26, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, N.K.; Sehyr, Z.S.; Cohen-Goldberg, A.M.; Emmorey, K. ASL-LEX: A lexical database of American Sign Language. Behavior Research Methods 2017, 49, 784–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brentari, D. A prosodic model of sign language phonology; Language, speech, and communication, MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fricke, E.; Bressem, J. Gesten - gestern, heute, übermorgen. Vom Forschungsprojekt zur Ausstellung; Universitätsverlag Chemnitz: Chemnitz, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, M.; Tang, Y.; Li, H. State-of-the-Art in Data Gloves: A Review of Hardware, Algorithms, and Applications. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 2023; 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plawiak, P.; Sosnicki, T.; Niedzwiecki, M.; Tabor, Z.; Rzecki, K. Hand Body Language Gesture Recognition Based on Signals From Specialized Glove and Machine Learning Algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2016, 12, 1104–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, P.; Purdack, D.; Wolf, S.; Müller, P.N.; Tregel, T.; Göbel, S. Paper Beats Rock: Elaborating the Best Machine Learning Classifier for Hand Gesture Recognition. In Serious Games; Söbke, H., Spangenberger, P., Müller, P., Göbel, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzuoli, F.; Corona, D.; Corradini, M.L. Recognition and Classification of Dynamic Hand Gestures by a Wearable Data-Glove. SN Computer Science 2021, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukor, A.Z.; Miskon, M.F.; Jamaluddin, M.H.; Ali@Ibrahim, F.b.; Asyraf, M.F.; Bahar, M.B.b. A New Data Glove Approach for Malaysian Sign Language Detection. Procedia Computer Science 2015, 76, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggio, G.; Cavallo, P.; Ricci, M.; Errico, V.; Zea, J.; Benalcázar, M.E. Sign Language Recognition Using Wearable Electronics: Implementing k-Nearest Neighbors with Dynamic Time Warping and Convolutional Neural Network Algorithms. Sensors 2020, 20, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, N. Recognition and Classification of Handshapes of American Finger Alphabet. Bachelor’s Thesis, Technical University of Darmstadt, Darmstadt, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; Vanderplas, J.; Passos, A.; Cournapeau, D. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. MACHINE LEARNING IN PYTHON.

- Ali, S.; Smith-Miles, K.A. Improved Support Vector Machine Generalization Using Normalized Input Space. In AI 2006: Advances in Artificial Intelligence; Springer, 2006; pp. 362–371. [Google Scholar]

- Ghojogh, B.; Crowley, M. The Theory Behind Overfitting, Cross Validation, Regularization, Bagging, and Boosting: Tutorial, 2019. arXiv:1905.12787.[cs, stat].

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Qian, K.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Wu, C.; Yang, Z. Widar3.0: Zero-Effort Cross-Domain Gesture Recognition With Wi-Fi. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021, 44, 8671–8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palipana, S.; Salami, D.; Leiva, L.A.; Sigg, S. Pantomime: Mid-air gesture recognition with sparse millimeter-wave radar point clouds. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 2021, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, H.; Al-Naser, M.; Ahmed, S.; Akiyama, T.; Sato, T.; Nguyen, P.; Nakamura, K.; Dengel, A. Augmenting Wearable Sensor Data with Physical Constraint for DNN-Based Human-Action Recognition. Time Series Workshop. Time Series Workshop @ ICML, befindet sich ICML 2017, August 11-11, Sydney, Australia. 2017; 5. [Google Scholar]

- Um, T.T.; Pfister, F.M.J.; Pichler, D.; Endo, S.; Lang, M.; Hirche, S.; Fietzek, U.; Kulić, D. Data augmentation of wearable sensor data for parkinson’s disease monitoring using convolutional neural networks. Proceedings of the 19th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction; ACM: Glasgow UK, 2017; pp. 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ostadabbas, S. A Semi-supervised Data Augmentation Approach Using 3D Graphical Engines. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2018 Workshops; Leal-Taixé, L., Roth, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; Vol. 11130, pp. 395–408, Series Title: Lecture Notes in Computer Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blender Online Community. Blender - a 3D modelling and rendering package; Stichting Blender Foundation: Amsterdam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Feix, T. Anthropomorphic hand optimization based on a latent space analysis; na, 2011.

- Baraniuk, R.G.; Cevher, V.; Wakin, M.B. Low-dimensional models for dimensionality reduction and signal recovery: A geometric perspective. Proceedings of the IEEE 2010, 98, 959–971, Publisher: IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, D. A genetic algorithm tutorial. Statistics and Computing 1994, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.J.; Li, Y.Y.; Li, J.X.; Fu, Y. Gesture Recognition Based on BP Neural Network Improved by Chaotic Genetic Algorithm. International Journal of Automation and Computing 2018, 15, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P.; Cord, M.; Delany, S.J. Supervised Learning. In Machine Learning Techniques for Multimedia; Springer, 2008; pp. 21–49. [Google Scholar]

- Galar, M.; Fernández, A.; Barrenechea, E.; Bustince, H.; Herrera, F. An overview of ensemble methods for binary classifiers in multi-class problems: Experimental study on one-vs-one and one-vs-all schemes. Pattern Recognition 2011, 44, 1761–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimaneekarn, N.; Hayter, A.; Liu, W.; Tantipoj, C. Binary response analysis using logistic regression in dentistry. International Journal of Dentistry 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zappi, P.; Lombriser, C.; Stiefmeier, T.; Farella, E.; Roggen, D.; Benini, L.; Tröster, G. Activity recognition from on-body sensors: accuracy-power trade-off by dynamic sensor selection. In Wireless Sensor Networks: 5th European Conference, EWSN 2008, Bologna, Italy, January 30-February 1, 2008. Proceedings; Springer: Italy, 2008; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, I.H. Machine Learning: Algorithms, Real-World Applications and Research Directions. SN Computer Science 2021, 2, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Short Biography of Authors

|

Philipp Achenbach completed his master’s degree in mechatronics at the Technical University of Darmstadt in 2018. His thesis was about full-body reconstruction using Inverse Kinematics in the context of Virtual Reality. He joined the Multimedia Communications Lab of the Technical University of Darmstadt as a research assistant in March 2019 and moved with his group to the Department of Electrical Engineering in early 2022. He researches in the area of hand gesture recognition using wearables in the context of sign language. For this he is also intensively working on the application of different machine learning classifiers. In addition, he is active in teaching (Serious Games and previously Communication Networks II). |

|

Dennis Purdack wrote both his computer science bachelor’s and master’s theses on sign language recognition using various Machine Learning methods and different hardware such as data gloves and camera-based systems. He completed his bachelor’s degree in 2021 and his master’s degree in 2022. Both were completed at the Technical University of Darmstadt. He is currently working at the Hessian University for Public Management and Security to develop a virtual reality training program for police officers using full-body tracking. |

| |

Sebastian Laux is currently studying for a master’s degree in computer science at the Technical University of Darmstadt. In 2022, he wrote his bachelor thesis on sign language recognition using data gloves with a focus on data augmentation. He also works as a student assistant in the Serious Games research group at the Technical University of Darmstadt, where he assists research on hand gesture recognition with wearable sensors. |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

We used the 3D hand model provided by the Manus Core Plugins and visualized it using Blender [ 24]. |

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

Figure 1.

Our classification pipeline

Figure 1.

Our classification pipeline

Figure 2.

Manus Prime X data glove and bare sensors of the glove [

15].

Figure 2.

Manus Prime X data glove and bare sensors of the glove [

15].

Figure 3.

Hand shapes R, H (identical to U, only different in orientation) and V differ only in spread.

Figure 3.

Hand shapes R, H (identical to U, only different in orientation) and V differ only in spread.

Figure 4.

DBSCAN assigning points into core, border and noise points

4.

Figure 4.

DBSCAN assigning points into core, border and noise points

4.

Figure 5.

Minimum, mean and maximum values of hand shape Horns.

Figure 5.

Minimum, mean and maximum values of hand shape Horns.

Figure 8.

Outlier (bent thumb and middle finger) found for hand shape Open F alongside Inlier of the same hand shape and visualization.

Figure 8.

Outlier (bent thumb and middle finger) found for hand shape Open F alongside Inlier of the same hand shape and visualization.

Figure 9.

Visualized effect of Data Augmentation for hand shape Horns.

Figure 9.

Visualized effect of Data Augmentation for hand shape Horns.

Figure 11.

Faulty recordings of hand shapes M, N and T of participant 2 and 5.

Figure 11.

Faulty recordings of hand shapes M, N and T of participant 2 and 5.

Table 1.

Features and Joint Values with their respective range of motion (normalized output of Manus Core SDK and corresponding degree range). Names of joints can be seen in

Figure 6.

Table 1.

Features and Joint Values with their respective range of motion (normalized output of Manus Core SDK and corresponding degree range). Names of joints can be seen in

Figure 6.

| Feature |

Finger |

Joint Value |

SDK Range |

Degree Range |

| |

|

|

Min |

Max |

Min |

Max |

| 0 |

Thumb |

Spread cmc |

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

Index |

Spread mcp |

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

Middle |

Spread mcp |

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

Ring |

Spread mcp |

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

Pinky |

Spread mcp |

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

Thumb |

Stretch cmc |

|

|

|

|

| 6 |

Thumb |

Stretch mcp |

|

|

|

|

| 7 |

Thumb |

Stretch ip |

|

|

|

|

| 8 |

Index |

Stretch mcp |

|

|

|

|

| 9 |

Index |

Stretch pip |

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

Index |

Stretch dip |

|

|

|

|

| 11 |

Middle |

Stretch mcp |

|

|

|

|

| 12 |

Middle |

Stretch pip |

|

|

|

|

| 13 |

Middle |

Stretch dip |

|

|

|

|

| 14 |

Ring |

Stretch mcp |

|

|

|

|

| 15 |

Ring |

Stretch pip |

|

|

|

|

| 16 |

Ring |

Stretch dip |

|

|

|

|

| 17 |

Pinky |

Stretch mcp |

|

|

|

|

| 18 |

Pinky |

Stretch pip |

|

|

|

|

| 19 |

Pinky |

Stretch dip |

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

Hyperparameter optimization ranges for our experiments.

Table 2.

Hyperparameter optimization ranges for our experiments.

| Classifier |

Parameter |

Pre-Grid Search Range |

Grid Search Range |

| SVM |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

| RF |

criterion |

gini, entropy |

gini, entropy |

| max_features |

|

|

| n_estimators |

|

|

| LR |

penalty |

elasticnet |

elasticnet |

| solver |

newton-cg, lbfgs, sag, saga |

saga |

| C |

|

|

| l1_ratio |

|

|

| penalty |

none, l1, l2

|

|

| solver |

newton-cg, lbfgs, sag, saga |

newton-cg, lbfgs, sag, saga |

| C |

|

|

Table 3.

Mean accuracy values of Leave-One-Out cross-validation in dependence of different data preprocessing methods for 27 hand shapes (Outlier Detection, Data Augmentation, Feature Selection).

Table 3.

Mean accuracy values of Leave-One-Out cross-validation in dependence of different data preprocessing methods for 27 hand shapes (Outlier Detection, Data Augmentation, Feature Selection).

| Data Preprocessing |

Machine Learning Classifier |

Results |

| Out |

Aug |

Feat |

SVM |

RF |

LR |

VL2 |

Mean |

Min |

Max |

| ✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

0.9080 |

0.9123 |

0.8963 |

0.9160 |

0.9082 |

0.8963 |

0.9160 |

| ✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

0.9037 |

0.9105 |

0.8951 |

0.9185 |

0.9069 |

0.8951 |

0.9185 |

| ✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

0.9037 |

0.9037 |

0.8914 |

0.9123 |

0.9028 |

0.8914 |

0.9123 |

| ✗ |

✓ |

✓ |

0.9031 |

0.9049 |

0.9000 |

0.9154 |

0.9059 |

0.9000 |

0.9154 |

| ✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

0.9080 |

0.9043 |

0.8981 |

0.9191 |

0.9074 |

0.8981 |

0.9191 |

| ✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

0.9043 |

0.9037 |

0.8981 |

0.9111 |

0.9043 |

0.8981 |

0.9111 |

| ✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

0.9031 |

0.9025 |

0.8951 |

0.9142 |

0.9037 |

0.8951 |

0.9142 |

| ✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

0.9025 |

0.9000 |

0.8920 |

0.9130 |

0.9019 |

0.8920 |

0.9130 |

| Mean |

0.9046 |

0.9052 |

0.8958 |

0.9150 |

|

|

|