Submitted:

21 November 2023

Posted:

21 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

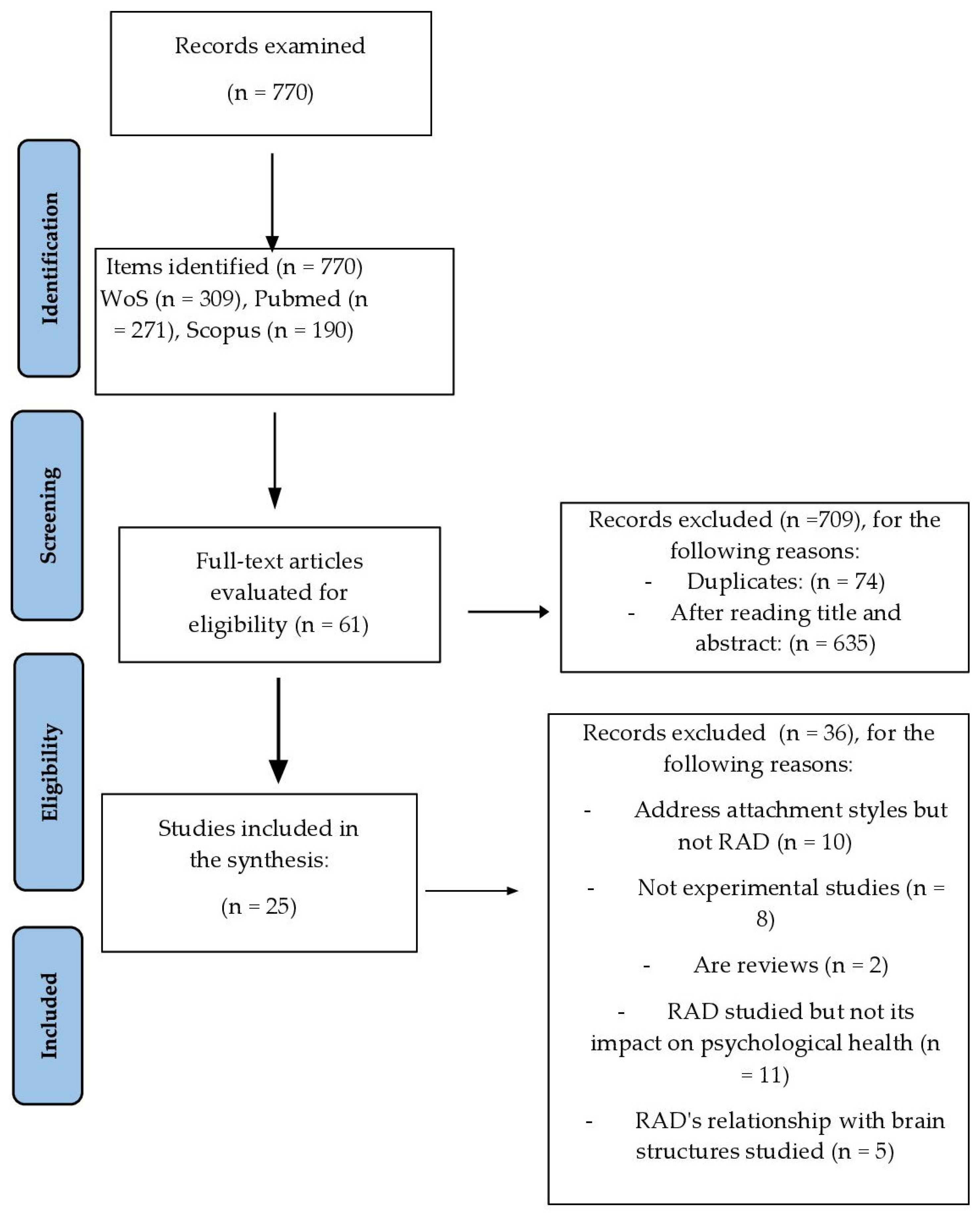

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Methodological Quality of the Selected Articles

3. Results

3.1. RAD Diagnostic and Assessment Tests Used in the Articles Included in the Systematic Review

| Article | Country of sample and life history or protection measures | Sample | Instrument used to assess RAD or DSED or diagnostic criteria used | Main results | Study limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bosmans et al. (2019) [39] |

Belgium. Children in special education schools. 48% suspected of mistreatment, abuse or neglect. |

Children with RAD: n = 21. Children without RAD: n = 46. Mage: 8.70 years, SD= 0.99 27.2 % were diagnosed or suspected with RAD. |

Disturbance Attachment Interview – DAI [28]. | RAD correlates negatively with trust in teachers and emotional security compared to the group without RAD. | They only focus on children's emotional safety in relation to teachers, rather than on their general context. |

| Bruce et al. (2019) [40] |

Scotland. Children in foster care. | Moment 1: N = 100 Moment 2: N = 76 Age: 12-61 months |

The Rating of Inhibited Attachment Behavior Scale - RInAB [33]. | There is a relationship between RAD symptomatology and the presence of internalising and externalising problems, as well as lower verbal and total IQ. | Small sample size and small number of children with RAD. Change in protective measure between moment 1 and moment 2. The procedure used to activate the attachment mechanism in children may not be sufficiently stressful. Change of caregivers at moment 1 in some children. |

| Coughlan et al. (2021) [35] |

England. There is no information on its previous history. |

Group RAD (n =39), Group ADHD (n=1.430) Group ASD (n= 1.193) Age 17 years< |

World Health Organisation ICD-10 [56] | There are significant differences between groups (p < 0.001) in all factors of the SDQ questionnaire. The ASD group had more emotional problems, difficulties with peers and fewer prosocial strengths than the ADHD or RAD group. ADHD and RAD group more hyperactivity and behavioural problems. | Additional information from the children's context is not available for a better understanding of the results. |

| Davidson et al. (2015) [41] |

Scotland RAD Group, history of abuse and fostering. |

Children 5-11 years. Group RAD: n = 67 Group ASD: n = 58 |

Disturbance Attachment Interview - DAI [28]. | Higher prevalence of comorbidity with other mental health problems, as well as more disinhibition and indiscriminate friendliness in the RAD group. | Failure to discriminate between different types of RAD. The discrepancy between RAD diagnostic criteria (DSM-IV) and RAD assessment instrument that follows DSM-5 criteria. |

| Elovainio et al. (2015) [34] |

Finland. Adopted children. |

N= 853. Age: 6-15 years. No RAD n = 348; DSED n = 153; RAD n = 137, comorbid (DSED+TAR) n = 214. |

Disturbance Attachment Interview - DAI [28]. | Relationship between RAD and DSED with the presence of emotional, hyperactive and behavioural symptoms. The comorbid group had greater internalising, externalising and total problems than the other groups. | Does not allow for causal relationships between attachment disorders and psychological problems. Heteroinformed assessment (adoptive parents). |

| Giltaij et al. (2016) [36] |

The Netherlands. No data on life history. RAD group has higher indicators of neglectful care. |

N = 55. Age: 5-11 years. Mild intellectual disability. RAD (n= 3); DSED (n= 1); RAD+DSED (n=6). Control group (n= 45). |

Diagnosis is based on the criteria of the DSM-5 [6]. | RAD+DSED group has greater difficulties in adaptive behaviour in the area of socialisation and motor skills. RAD and/or DSED group had more disruptive and antisocial behaviour than the control group. DSED had greater emotional problems compared to the non-DSED group. |

Hetero- information (teachers). |

| Gleason et al. (2011) [13] |

Romania Children spent an average of 86% of their lives in institutional care. |

N= 136 initially (6-30 months). These were followed up at 30, 42 and 54 months of age. n= 68 assigned to care as usual. n=68 foster care. |

Disturbance Attachment Interview - DAI [28]. | DSED criteria met: Study start 41/129 (31.8 %), 30 months 22/122 (17.9 %), 42 months 22/122 (18.0 %) and 54 months of age 22/125 (17.6 %). RAD-I criteria met: Study entry 6/130 (4.6 %), 30 months 4/123 (3.3 %), 42 months 2/125 (1.6 %) and 54 months of age 5/122 (4.1 %). |

Neglectful care conditions other than institutionalisation were not assessed. The life history and background of caregivers (maltreatment or mental health status) are not considered. (maltreatment or mental health status). Low rates of emotionally withdrawn/inhibited RAD. |

| Guyon-Harris et al. (2019) [42] |

Romania. Foster care |

Experimental group (n = 55). Control group (n = 50). Mage = 12.80, (SD=0.71) years. | Version DAI-EA [20] adapted Disturbance Attachment Interview - DAI [28]. | A greater presence of RAD signs predicts worse overall social functioning and lower social competence. A greater presence of DSED signs predicts worse social functioning, more relationship victimisation and lower social competence. |

Adolescent self-reports are not included. Signs of RAD are examined, but not the diagnosis. Focuses on social functioning and does not explore other domains. |

| Hong et al. (2018) [37] |

Corea del Sur General population |

Children <10 years. N = 14,029,571 RAD = 736 |

Diagnosis is based on the criteria of the [57]. | Higher prevalence of comorbid disorders in children with RAD than in typically developing children. This type of disorder varies according to age group. | Patients who underwent treatment outside the hospital are not included. The precise incidence of RAD is not reflected. |

| Jonkman et al. (2014) [43] |

Netherlands The children had experienced at least one foster care disruption. |

N=126 in Foster care families. Age: 24-72 months with the foster family). Control group n = 84; RAD-I: n =11; DSED: n = 19; RAD-I+DSED n = 12. |

Disturbance Attachment Interview - DAI [28]. | RAD and DSED groups presented greater internalising, externalising and total problems. | Small sample size. Observational measures. Hetero-informed assessment (family members and teachers). |

| Kay y Green (2013) [15] |

England Residential care and children at risk of social exclusion. |

Group RAD foster care: N= 153. Group RAD social risk: n = 42. Age: 10-15 years. |

Development and Wellbeing Assessment–RAD/DSED Section (DAWBA-RAD/DSED; [30] 24-item version. | Greater presence of RAD symptomatology in the group in foster care compared to the social risk group. Relationship between RAD symptomatology and greater behavioural and emotional problems and a lower adaptive capacity. |

Hetero- information (social workers). Incomplete data on participants' life history. |

| Kay et al. (2016) [16] |

England Adopción. Sin antecedes de institucionalización previa. |

Adoption group: n = 60. Group with externalising disorder: n = 26. Group at social risk: n = 55 Age: 6-11 month. |

CAPA-RAD [16,41] adaption of CAPA [29] based on the DSM-5 criteria [6]. | In the adoption group, there is a significant relationship between the presence of DSED and ADHD according to the teachers. According to parents, this relationship is found with ADHD, emotional and behavioural problems. | Small sample size. Biases in sample selection. No clinical diagnosis of DSED. Lack of pre-adoption information on children's life history. Hetero-informed assessment (family members and teachers). |

| Kocovska et al. (2012) [44] |

United Kingdom. Adopted children who have suffered abuse, neglect, abandonment and abuse. | N = 66. Age: 5-12 years. Adopted group (n = 33) of which 20 had RAD. Control group (n = 32). |

Relationship Patterns Questionnaire (RPQ) [32]. | The group of adopted children presented greater behavioural problems than the group of non-adopted children. High prevalence of children with RAD in the adopted group. | Possible bias in the sample of adopted families as those with higher motivation and better family functioning participated. The attachment assessment measure used has shown adequate psychometric properties in children under 8 years of age and the sample is somewhat larger. |

| Lehmann et al. (2016) [14] |

Norway Foster care. |

N = 122 Age: 6-10 years. | Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder Assessment – RADA [31]. | The positive association between RAD symptoms and DSED. RAD is associated with more comorbid personal difficulties than DSED. | Small sample size. Hetero-informed (caregiver) assessment. Broad, general categories of experiences of maltreatment. |

| Mayes et al. (2017) [45] |

United States. Children who have suffered severe abuse or neglect (N= 16) and children adopted from Russian or Chinese orphanages (N= 4). |

RAD+DSED n = 15; DSED n = 5; ASD n = 933; ADHD-C n = 631; ADHD-I n = 264. | The Rating of Inhibited Attachment Behavior Scale - RInAB [33]. | RAD group: All of them had callous-unemotional traits and 73 % had behavioural problems. RAD-I+DSED group: More behavioural problems and emotional insensitivity than DSED group. RAD group had more behavioural and emotional problems than the group with ASD, with ADHD-C and ADHD-I. |

Unrepresentative sample of children with RAD because of their size and because they initially presented other personal difficulties that required referral. |

| Moran et al. (2017) [46] |

Young people in the Youth Justice Service. 86% had experienced abuse. |

N = 29. Age: 12-17 years. Mage = 16.2; SD = 1.3. Carers: n = 29. Teachers: n = 20. | The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment – CAPA [29] | Relationship between RAD symptoms and other mental health problems. More mental health problems in the RAD group than in the non-ADR group. | Does not allow causal relationships to be established. Heteroassessment (parents and teachers). It is not known whether the children had any other psychological or neuropsychological problems. |

| Pritchett et al. (2013) [52] |

England. The general population with socio-cultural deprivation. RAD group have histories of abuse. |

N = 1.600. Age: 6-12 years. RAD group (n = 22). Of these 13 with a diagnosis of RAD and 9 with suspected | The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment – CAPA [29] | RAD group has a high comorbidity with other disorders and with the presence of behavioural problems. | Small sample size. |

| Raaska et al. (2012) [47] |

Finland. Children adopted between 1985 and 2007 from different countries. | N= 365. Age: 9-15 years. (47,8 % man). | FinAdo-RAD [34]. | There is a significant relationship between the severity of RAD symptomatology and participation in bullying situations, both victimisation and peer bullying. | Relatively low response rate. Children completed the questionnaires at home (possible parental influence). There is no information on whether RAD also relates to those children who engage in bullying in normative samples. |

| Sadiq et al. (2012) [38] |

Muestra con TAR: 1/3 vivía con la familia biológica y 2/3 eran adoptados. | N = 126. Age: 5-8 years. RAD group: n = 35. ASD group: n = 52. TD: n = 13 grupo. |

Diagnosis is based on the criteria of World Health Organisation ICD-10 [58] | RAD group had difficulties in the use of context, rapport and social relations than ASD group. | Clinical sample and not general population. |

| Seim et al. (2021) [48] |

Norway Residential care. 71% exposure to abuse. |

N = 306. Age: 12.2-20.2 years. Of these, with RAD (n = 28), with DSED (n = 26). Control group: n = 10480. Age: 12-20 years. |

The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment - PAPA [55] adaptation of CAPA [29] for children between 2 and 8 years. | RAD group lower self-esteem in school competence and higher self-esteem for close friendships than the control group. DSED group lower self-esteem in social acceptance, sports competence, romantic attractiveness and close friendship than control group. |

Hetero- information (caregivers). Inability to determine whether symptoms were present before the age of 5 years. |

| Seim et al. (2022) [49] |

Norway. Foster care. Exposure to neglect. 71% exposed to abuse. |

N = 381. Age:12.2-20.2 years. RAD (n = 33). DSED (n = 31). RAD+DSED (n = 2) | The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment - PAPA [55] adaptation of CAPA [29] for children between 2-8 years | High prevalence of mental disorders in children with RAD and DSED. Children with RAD and/or DSED high prevalence of emotional and behavioural problems. |

Heteroassessment (caregivers). Difficulty in demonstrating the presence of RAD before the age of 5 years. |

| Shimada et al. (2015) [50] |

Japan. Residential Foster care. RAD Group has suffered abuse and neglect |

RAD group: n = 21. Mage = 12.76 years. Group control: n = 22. Mage = 12.95 years. |

Diagnosis based on the criteria of DSM-5 criteria [6] | RAD group: smaller volume of grey matter. This is related to greater internalising and externalising problems according to the SDQ. | Small sample size. Cross-sectional design. Differences in IQ between RAD group and control group. |

| Vervoort et al. (2013) [53] |

Belgium. School-aged children with emotional and behavioural problems. 25% diagnosed or suspected RAD. 48% maltreatment, abuse or neglect. | Children DAI n = 77. Children RPQ n = 152. Mage 7.92 years. |

Disturbance Attachment Interview - DAI [28]. Relationship Problems Questionnaire - RPQ [30] |

More frequent and stronger associations between RAD and emotional and behavioural difficulties than DSED. | Small sample size. Need to use other measures to confirm the diagnosis of RAD. |

| Vervoort et al. (2014) [54] |

Belgium. Special education children with emotional and behavioural problems (suspected DSED). | DSED group: N = 33 special education. Control group: N = 33 general education. Mage 8.52 years |

Relationship Problems Questionnaire - RPQ [30] | DSED group showed more indiscriminate kindness and more behavioural problems than the control group. DSED group showed more positive overall self-concept and greater confidence in relationships compared to general education children. | The study focuses on one DSED indicator (indiscriminate kindness). Cross-sectional study. |

| Zimmerman & Iwanski (2019) [51] |

Germany. Children at risk of RAD-I had experienced severe neglect or abuse. |

N= 64 children in institutions and the general population. Age: 5-10 years. Of these, 32 suffered from RAD (foster homes or families). | Relationship Patterns Questionnaire - RPQ [32] | RAD risk group has a poorer self-concept, a greater number of negative signals from others through Internal Working Models and greater mental health problems. Positive association RAD with personal difficulties and negative association with prosocial behaviour. | Not specified |

3.2. Conditions and Previous History of the Sample According to the Articles Included in the Review

3.3. Association between RAD Diagnosis and Other Personal, Social and Mental Health Difficulties

3.4. Differences between the RAD Group with Other Children with Neurodevelopmental or Typical Developmental Problems

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowlby, J. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Psychological Disorders in Childhood. Health Education Journal 1954, 12, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeanah, C.H.; Gleason, M.M. Annual Research Review: Attachment disorders in early childhood - clinical presentation, causes, correlates, and treatment. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Main, M. Introduction to the special section on attachment and psychopathology: 2. Overview of the field of attachment. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 64, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fresno, A.; Spencer, R.; Retamal, T. Maltrato infantil y representaciones de apego: defensas, memoria y estrategias, una revisión. Univ. Psychol. 2012, 11, 829–838. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, E.E.; Yilanli, M.; Saadabadi, A. Reactive Attachment Disorder. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, 2023.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

- Granqvist, P.; Sroufe, L.A.; Dozier, M.; Hesse, E.; Steele, M.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.; et al. Disorganized attachment in infancy: a review of the phenomenon and its implications for clinicians and policy-makers. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2017, 19, 534–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, S.; Breivik, K.; Monette, S.; Minnis, H. Potentially traumatic events in foster youth, and association with DSM-5 trauma- and stressor related symptoms. Child. Abuse Negl. 2020, 101, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, M.; Beckwith, H.; Duschinsky, R.; Forslund, T.; Foster, S.L.; Coughlan, B.; Pal, S.; Schuengel, C. Attachment difficulties and disorders. InnovAiT 2019, 12, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, 1994.

- Zeanah, C.H. Beyond insecurity. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 64, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilberstein, K. Clarifying core characteristics of attachment disorders. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2006, 76, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, MM.; Fox, NA.; Drury, S.; Smyke, A.; Egger, HL.; Nelson, CA.; Gregas, MC.; Zeanah, CH. Validity of evidence-derived criteria for Reactive Attachment Disorder: Indiscriminately Social/Disinhibited and Emotionally Withdrawn/Inhibited types. J. Am. Aca Child. Adol Psychiatry 2011, 50, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S. , Breivik, K.; Heiervang, ER.; Havik, T.; Havik, OE. Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder in school-aged foster children - a confirmatory approach to dimensional measures. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2016, 44, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, C.; Green, J. Reactive Attachment Disorder following early maltreatment: Systematic evidence beyond the institution. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2013, 41, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, C.; Green, J.; Sharma, K. Disinhibited Attachment Disorder in UK adopted children during middle childhood: Prevalence, validity and possible developmental rigin. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2016, 44, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugaard, JJ.; Hazan, C. ; Recognizing and treating uncommon behavioral and emotional disorders in children and adolescents who have been severely maltreated: Reactive Attachment Disorder. Child. Maltreat 2004, 9, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, S.; Havik, OE.; Havik, T.; Heiervang, ER. Mental disorders in foster children: a study of prevalence, comorbidity and risk factors. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2013, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, C.; Zeanah, CH. Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder. The Encyclopedia Clin. Psychol. 2015, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, KL.; Nelson, CA.; Fox, NA.; Zeanah, CH. Signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder at age 12 years: Effects of institutional care history and high-quality foster care. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, M.; Palacios, J.; Minnis, H. Changes in Attachment Disorder symptoms in children internationally adopted and in residential care. Child. Abuse Negl. 2022, 130, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, CM.; Pimenta, CA.; Nobre, MR. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev. Latino-am Enfermagem 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. https://www.covidence.org. Accessed 22 Feb 2023.

- Ogrinc, G.; Davies, L.; Goodman, D.; Batalden, P.; Davidoff, F.; Stevens, D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised Publication Guidelines from a Detailed Consensus Process. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2016, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orwin, R.G. Evaluating coding decisions. In The handbook of research synthesis; Russell Sage Foundation, EEUU, 2018. pp. 95–107.

- Hernández-Nieto, RA. Contributions to Statistical Analysis: The Coefficients of Proportional Variance, Content Validity and Kappa. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2002.

- Smyke AT, Zeanah CH. Disturbances of attachment interview. New Orleans: Tulane University; 1999 (Unpublished Manual).

- Angold, A.; Prendergast, M.; Cox, A.; Harrington, R.; Simonoff, E.; Rutter, M. The child and adolescent psychiatric assessment (CAPA). Psychol. Med. 1995, 25, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnis, H.; Green, J.; O’Connor, T.; Liew, A.; Glaser, D.; Taylor, E.; Follan, M.; Young, D.; Barnes, J.; Gillberg, C.; et al. An exploratory study of the association between reactive attachment disorder and attachment narratives in early school-age children. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, S.; Monette, S.; Egger, H.; Breivik, K.; Young, D.; Davidson, C.; Minnis, H. Development and examination of the reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder assessment interview. Assessment 2020, 27, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurth, R.A.; Körner, A.; Geyer, M.; Pokorny, D. Relationship Patterns Questionnaire (RPQ): Psychometric properties and clinical applications. Psychother. Res. 2004, 14, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corval, R.; Baptista, J.; Fachada, I.; Soares, I. Rating of inhibited attachment disordered behavior. Unpublished manuscript, Universidade do Minho, 2016.

- Elovainio, M.; Raaska, H.; Sinkkonen, J.; Makipaa, S.; Lapinleimu, H. Associations between attachment-related symptoms and later psychological problems among international adoptees: results from the FinAdo study. Scand. J. Psychol. 2015, 56, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlan, B.; Woolgar, M.; Van Ijzendoorn, MH.; Duschinsky, R. Socioemotional profiles of autism spectrum disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and disinhibited and reactive attachment disorders: a symptom comparison and network approach. Dev. Psychopathol. 2021, 35, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giltaij, HP.; Sterkenburg, PS.; Schuengel, C. Psychiatric diagnostic screening of social maladaptive behaviour in children with mild intellectual disability: differentiating disordered attachment and pervasive developmental disorder behaviour. J. Intellec Disabil. Res. 2015, 59, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, M.; Moon, D.S.; Chang, H.; Lee, S.Y.; Cho, S.W.; Lee, K.; Bahn, G.H. Incidence and comorbidity of Reactive Attachment Disorder: Based on national health insurance claims data, 2010–2012 in Korea. Psychiatry Investig 2018, 15, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, FA.; Slator, L.; Skuse, D.; Law, J.; Gillberg, C.; Minnis, H. Social use of language in children with reactive attachment disorder and autism spectrum disorders. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2012, 21, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosmans, G.; Spilt, J.; Vervoort, E.; Verschueren, K. Inhibited symptoms of Reactive Attachment Disorder: links with working models of significant others and the self. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2019, 21, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, M.; Young, D.; Turnbull, S.; Rooksby, M.; Chadwick, G.; Oates, C.; et al. Reactive Attachment Disorder in maltreated young children in foster care. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2019, 21, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.; O’Hare, A.; Mactaggart, F.; Green, J.; Young, D.; Gillberg, C.; et al. Social relationship difficulties in autism and reactive attachment disorder: Improving diagnostic validity through structured assessment. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 40, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon-Harris, K.L.; Humphreys, K.L.; Fox, N.A.; Nelson, C.A.; Zeanah, C.H. Signs of attachment disorders and social functioning among early adolescents with a history of institutional care. Child. Abuse Negl. 2019, 88, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, C.S.; Oosterman, M.; Schuengel, C.; Bolle, E.A.; Boer, F.; Lindauer, R.J. Disturbances in attachment: inhibited and disinhibited symptoms in foster children. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2014, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocovska, E.; Puckering, C.; Follan, M.; Smillie, M.; Gorski, C.; Lidstone, E.; Pritchett, R.; Hockaday, H.; Minnis, H. Neurodevelopmental problems in maltreated children referred with indiscriminate friendliness. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 1560–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayes, S.D.; Calhoun, S.L.; Waschbusch, D.A.; Breaux, R.P.; Baweja, R. Reactive attachment/disinhibited social engagement disorders: Callous-unemotional traits and comorbid disorders. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 63, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, K.; McDonald, J.; Jackson, A.; Turnbull, S.; Minnis, H. A study of Attachment Disorders of young offenders attending specialist services. Child. Abuse Negl. 2017, 65, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raaska, H.; Lapinleimu, H.; Sinkkonen, J.; Salmivalli, C.; Matomäki, J.; Mäkipää, S.; et al. Experiences of School Bullying Among Internationally Adopted Children: Results from the Finnish Adoption (FINADO) Study. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2012, 43, 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seim, A.R.; Jozefiak, T.; Wichstrøm, L.; Lydersen, S.; Kayed, N.S. Self-esteem in adolescents with reactive attachment disorder or disinhibited social engagement disorder. Child. Abuse Negl. 2021, 118, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seim, A.R.; Jozefiak, T.; Wichstrøm, L.; Lydersen, S.; Kayed, N.S. Reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder in adolescence: co-occurring psychopathology and psychosocial problems. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Takiguchi, S.; Mizushima, S.; Fujisawa, T.X.; Saito, D.N.; Kosaka, H.; et al. Reduced visual cortex grey matter volume in children and adolescents with reactive attachment disorder. NeuroImage Clinical 2015, 9, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, P.; Iwanski, A. Attachment Disorder behavior in early and middle childhood: associations with children's self-concept and observed signs of negative internal working models. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2019, 21, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchett, R.; Pritchett, J.; Marshall, E.; Davidson, C.; Minnis, H. Reactive Attachment Disorder in the general population: A hidden ESSENCE disorder. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vervoort, T.; Trost, Z.; Van Ryckeghem, D.M.L. Children’s selective attention to pain and avoidance behaviour: The role of child and parental catastrophizing about pain. Pain. 2013, 154, 1979–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, E.; Bosmans, G.; Doumen, S.; Minnis, H.; Verschueren, K. Perceptions of self, significant others, and teacher–child relationships in indiscriminately friendly children. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 2802–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, H.L.; Erkanli, A.; Keeler, G.; Potts, E.; Walter, B.K.; Angold, A. Test-Retest Reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA). J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 45, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10: Version 2010. Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva. 2010.

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1992.

- World Health Organisation. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnostic criteria for research. World Health Organisation, Geneva. 1993.

- Vasquez, M.; Miller, N. Aggression in Children with Reactive Attachment Disorder: A sign of deficits in emotional regulatory processes? J. Aggress, Maltreat Trauma. 2018, 27, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J. Reactive Attachment Disorder: A biopsychosocial Disturbance of Attachment. Child. Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2007, 24, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schore, J.R.; Schore, A.N. Modern attachment theory: The central role of affect regulation in development and treatment. Clin. Soc. Work. J. 2008, 36, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).