Submitted:

20 November 2023

Posted:

22 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of DR Patients

- Non-diabetic subjects with absence of ocular pathologies (N = 12) - CTRL group;

- Diabetic patients without DR signs (N = 15 ) - Diabetic group;

- Diabetic patients with diagnosis of non-proliferative DR (N = 15) - NPDR group;

- Diabetic patients with diagnosis of proliferative DR (N = 15) - PDR group;

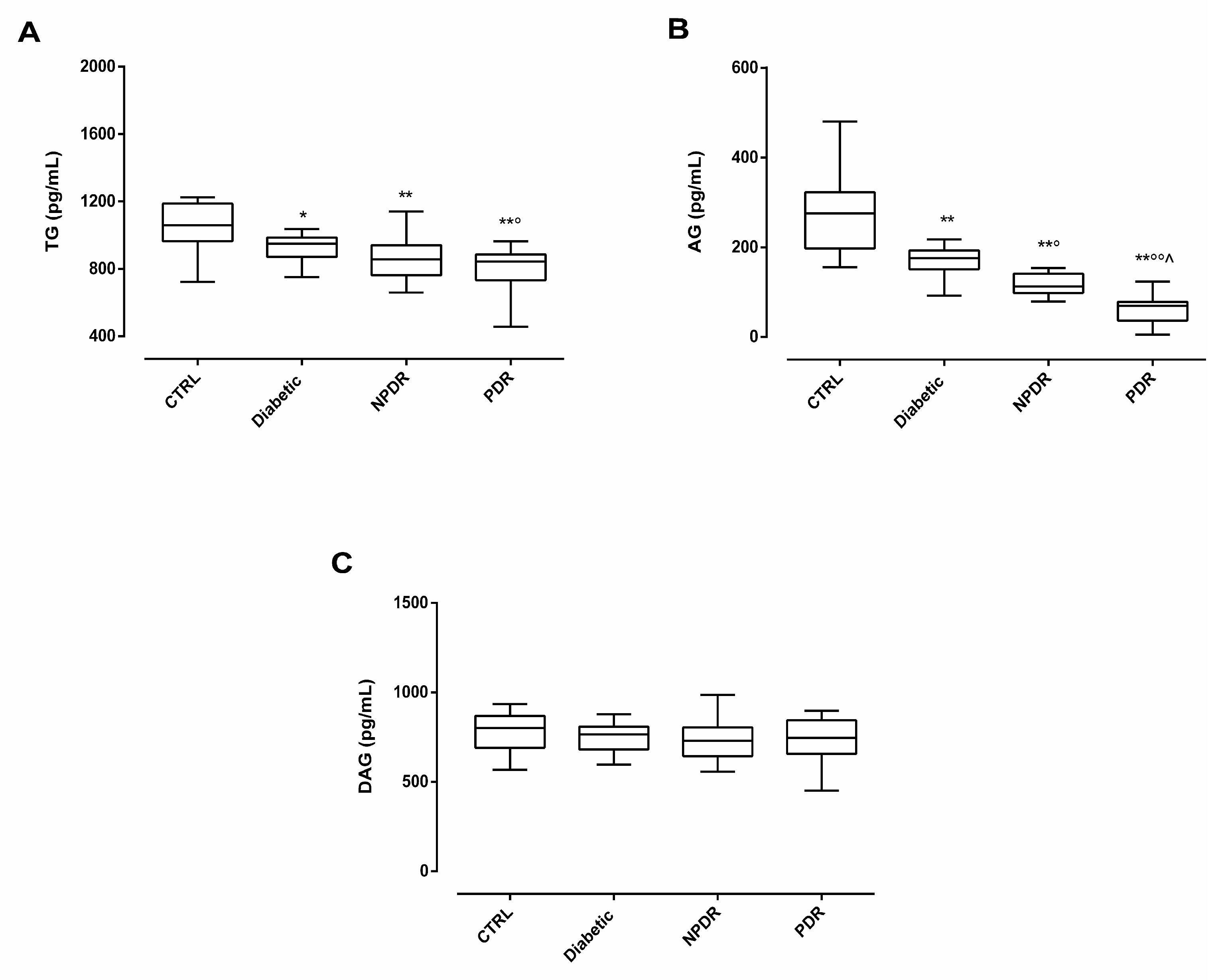

2.2. Serum Ghrelin Levels in DR Patients

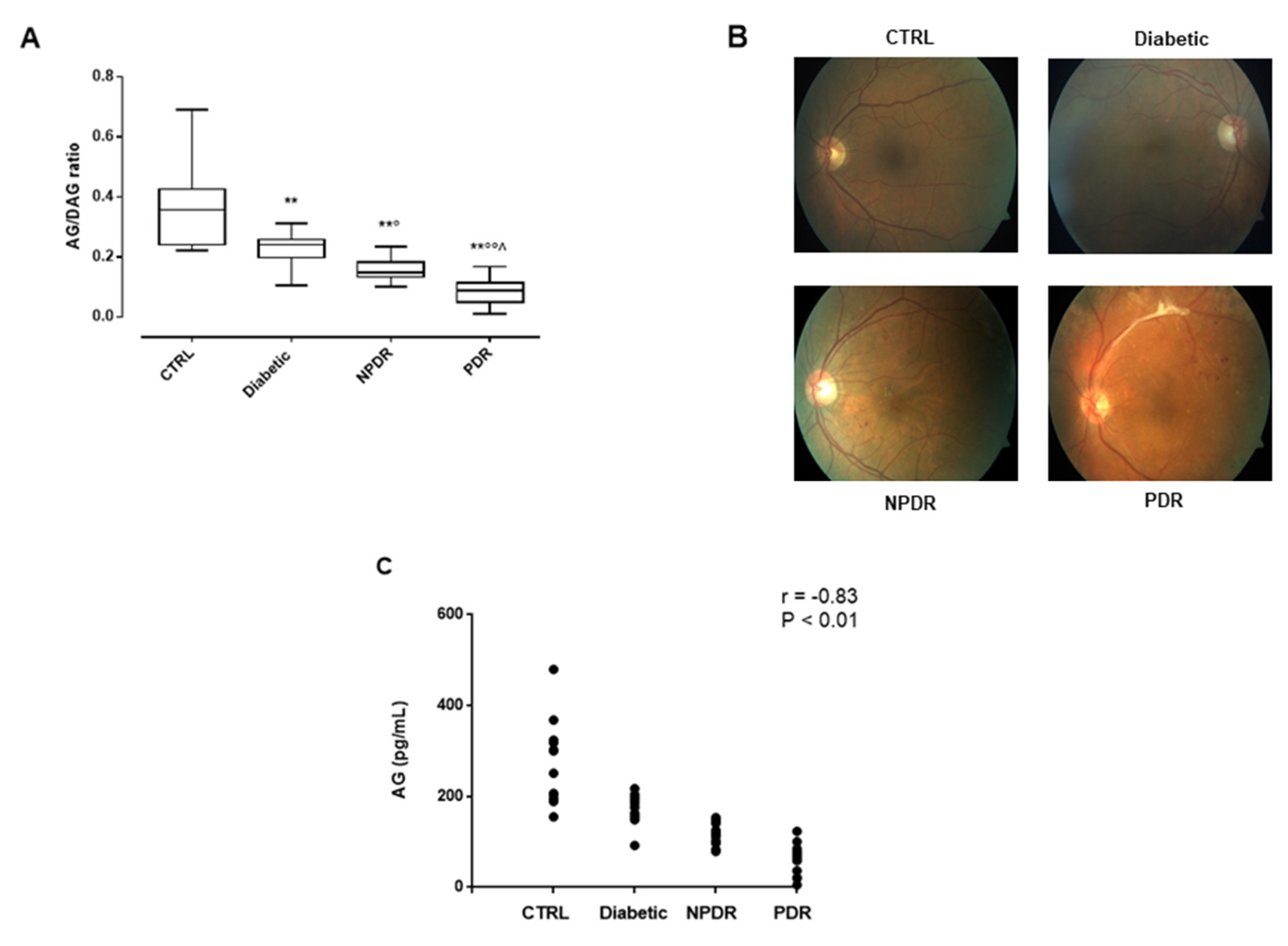

2.3. Serum AG/DAG Ratio and Its Correlation with Retinal Abnormalities in DR Patients

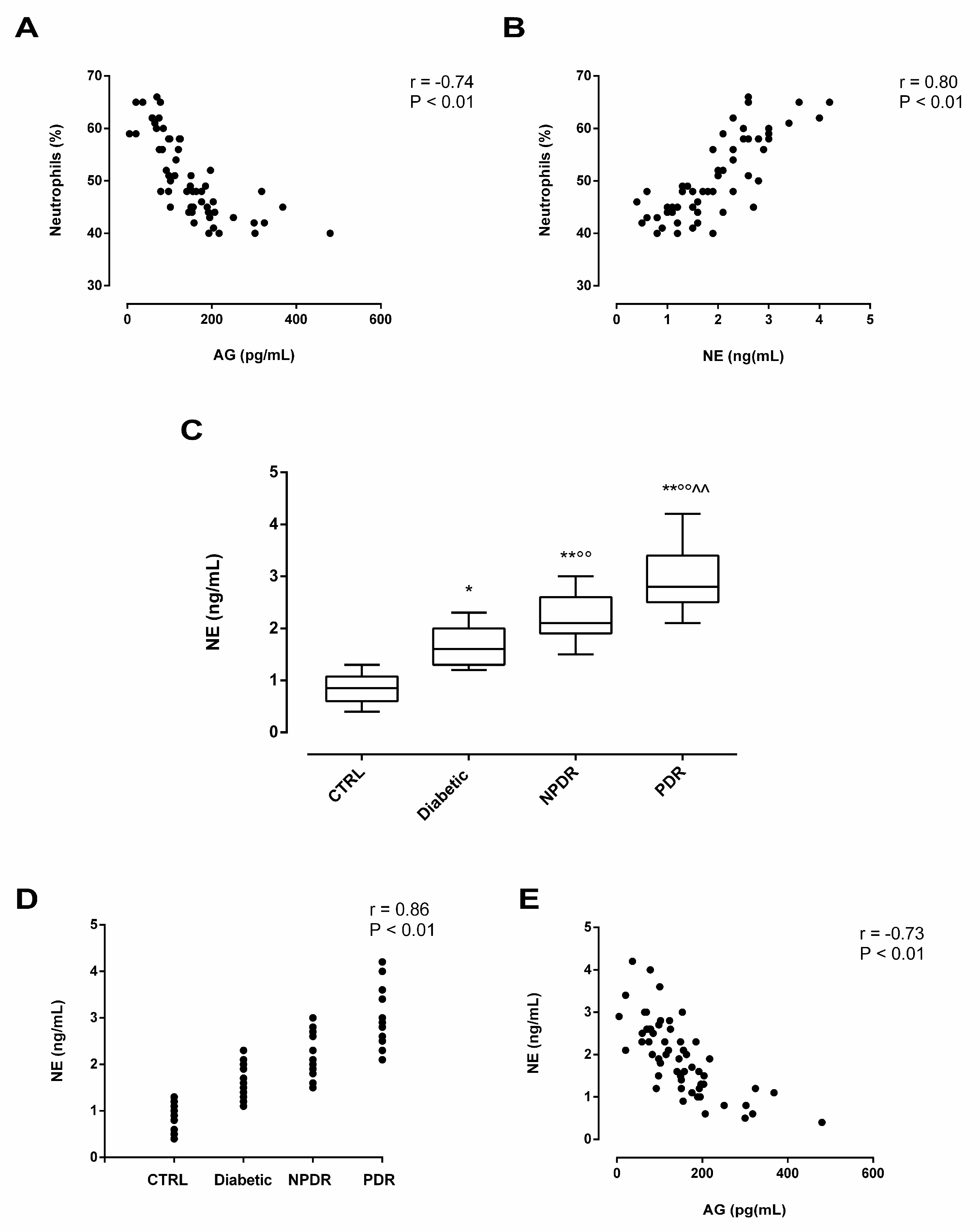

2.4. Serum Neutrophil Elastase (NE) Levels in DR Patients and Its Association with Serum AG

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Clinical Design

4.2. DR Diagnosis

4.3. Serum Samples Collection and Analysis of Serum Markers

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teo, Z.L.; Tham, Y.-C.; Yu, M.; Chee, M.L.; Rim, T.H.; Cheung, N.; Bikbov, M.M.; Wang, Y.X.; Tang, Y.; Lu, Y.; et al. Global Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy and Projection of Burden through 2045. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 1580–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó, R.; Hernández, C. New Insights into Treating Early and Advanced Stage Diabetic Retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, T.A.; Bakri, S.J. Update on the Management of Diabetic Retinopathy: Anti-VEGF Agents for the Prevention of Complications and Progression of Nonproliferative and Proliferative Retinopathy. Life 2023, 13, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonny, J.; Violetta, L.; Kartasasmita, A.S.; Supriyadi, R.; Rita, C. Circulating Biomarkers to Predict Diabetic Retinopathy in Patients with Diabetic Kidney Disease. Vision 2023, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trotta, M.C.; Gesualdo, C.; Petrillo, F.; Cavasso, G.; Corte, A.D.; D’Amico, G.; Hermenean, A.; Simonelli, F.; Rossi, S. Serum Iba-1, GLUT5, and TSPO in Patients with Diabetic Retinopathy: New Biomarkers for Early Retinal Neurovascular Alterations? A Pilot Study. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, G.; Samson, S.L.; Sun, Y. Ghrelin: Much More than a Hunger Hormone. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2013, 16, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Yang, F.; Dong, L.; Zheng, Y. Ghrelin Protects Human Lens Epithelial Cells against Oxidative Stress-Induced Damage. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, M.-L.; Liu, S.-T.; Li, X.-Y.; Zhong, S.-M.; Li, F.; Xu, G.-Z.; Wang, Z.; Miao, Y. Ghrelin Attenuates Retinal Neuronal Autophagy and Apoptosis in an Experimental Rat Glaucoma Model. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Yang, F.; Wang, R.; Yan, Q. Ghrelin Ameliorates Diabetic Retinal Injury: Potential Therapeutic Avenues for Diabetic Retinopathy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yao, G.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, M.; Yan, J. The Ghrelin-GHSR-1a Pathway Inhibits High Glucose-Induced Retinal Angiogenesis in Vitro by Alleviating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Eye Vis. 2022, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiridon, I.; Ciobanu, D.; Giușcă, S.; Căruntu, I. Ghrelin and Its Role in Gastrointestinal Tract Tumors (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zeng, M.; Zheng, H.; Huang, C.; He, W.; Lu, G.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Xie, R. Effects of Ghrelin on the Apoptosis of Human Neutrophils in Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 38, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, T.; Ashitani, J.-I.; Matsumoto, N.; Kangawa, K.; Nakazato, M. Ghrelin Treatment Suppresses Neutrophil-Dominant Inflammation in Airways of Patients with Chronic Respiratory Infection. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 21, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tawab, S.S.; Ibrahim, I.K.; Megallaa, M.H.; Mgeed, R.M.A.; Elemary, W.S. Neutrophil–Lymphocyte Ratio as a Reliable Marker to Predict Pre-Clinical Retinopathy among Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Egypt. Rheumatol. Rehabil. 2023, 50, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njeim, R.; Azar, W.S.; Fares, A.H.; Azar, S.T.; Kfoury Kassouf, H.; Eid, A.A. NETosis Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Diabetes and Its Complications. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2020, 65, R65–R76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xia, X.; He, Q.; Xiao, Q.-A.; Wang, D.; Huang, M.; Zhang, X. Diabetes-Associated Neutrophil NETosis: Pathogenesis and Interventional Target of Diabetic Complications. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1202463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, X.; Yin, Y.; Mai, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X. Hyperglycemia Induces Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Formation Through an NADPH Oxidase-Dependent Pathway in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafqat, A.; Abdul Rab, S.; Ammar, O.; Al Salameh, S.; Alkhudairi, A.; Kashir, J.; Alkattan, K.; Yaqinuddin, A. Emerging Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in the Complications of Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 995993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessieur, E.M.; Liu, H.; Saadane, A.; Du, Y.; Tang, J.; Kiser, J.; Kern, T.S. Neutrophil-Derived Proteases Contribute to the Pathogenesis of Early Diabetic Retinopathy. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Lessieur, E.M.; Saadane, A.; Lindstrom, S.I.; Taylor, P.R.; Kern, T.S. Neutrophil Elastase Contributes to the Pathological Vascular Permeability Characteristic of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 2365–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.D.; Zhou, Y.; Barak, L.S.; Caron, M.G. Ghrelin Receptor Signaling in Health and Disease: A Biased View. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 34, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Massadi, O.; López, M.; Tschöp, M.; Diéguez, C.; Nogueiras, R. Current Understanding of the Hypothalamic Ghrelin Pathways Inducing Appetite and Adiposity. Trends Neurosci. 2017, 40, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, P.; Xiong, J.; Liang, X.; Li, M.; Ke, H.; Chen, C.; Han, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Serum Levels of Ghrelin and LEAP2 in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Correlation with Circulating Glucose and Lipids. Endocr. Connect. 2022, 11, e220012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovetkina, A.; Nadir, R.; Fung, J.N.M.; Nadjarpour, A.; Beddoe, B. The Physiological Role of Ghrelin in the Regulation of Energy and Glucose Homeostasis. Cureus 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakhari, J.S.; Zorrilla, E.P.; Zhou, B.; Mayorov, A.V.; Janda, K.D. Oligoclonal Antibody Targeting Ghrelin Increases Energy Expenditure and Reduces Food Intake in Fasted Mice. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Tokudome, T.; Otani, K.; Kishimoto, I.; Nakanishi, M.; Hosoda, H.; Miyazato, M.; Kangawa, K. Ghrelin Prevents Incidence of Malignant Arrhythmia after Acute Myocardial Infarction through Vagal Afferent Nerves. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3426–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.S.; Kaufman, R.J. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Oxidative Stress in Cell Fate Decision and Human Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 21, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, M.; Yamaki, A.; Furuya, M.; Inomata, N.; Minamitake, Y.; Ohsuye, K.; Kangawa, K. Ghrelin Improves Body Weight Loss and Skeletal Muscle Catabolism Associated with Angiotensin II-Induced Cachexia in Mice. Regul. Pept. 2012, 178, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porporato, P.E.; Filigheddu, N.; Reano, S.; Ferrara, M.; Angelino, E.; Gnocchi, V.F.; Prodam, F.; Ronchi, G.; Fagoonee, S.; Fornaro, M.; et al. Acylated and Unacylated Ghrelin Impair Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2013, JCI39920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLarnon, A. Age-Dependent Balance of Leptin and Ghrelin Regulates Bone Metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 504–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, N.; Pedone, C.; Pozzilli, P.; Lauretani, F.; Bandinelli, S.; Ferrucci, L.; Incalzi, R.A. Effect of Ghrelin on Bone Mass Density: The InChianti Study. Bone 2011, 49, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesualdo, C.; Balta, C.; Platania, C.B.M.; Trotta, M.C.; Herman, H.; Gharbia, S.; Rosu, M.; Petrillo, F.; Giunta, S.; Della Corte, A.; et al. Fingolimod and Diabetic Retinopathy: A Drug Repurposing Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 718902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perais, J.; Agarwal, R.; Evans, J.R.; Loveman, E.; Colquitt, J.L.; Owens, D.; Hogg, R.E.; Lawrenson, J.G.; Takwoingi, Y.; Lois, N. Prognostic Factors for the Development and Progression of Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy in People with Diabetic Retinopathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöykkö, S.M.; Kellokoski, E.; Hörkkö, S.; Kauma, H.; Kesäniemi, Y.A.; Ukkola, O. Low Plasma Ghrelin Is Associated With Insulin Resistance, Hypertension, and the Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2003, 52, 2546–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, A.; Shcherbina, L.; Prasad, R.B.; Miskelly, M.G.; Abels, M.; Martínez-Lopéz, J.A.; Fred, R.G.; Nergård, B.J.; Hedenbro, J.; Groop, L.; et al. Ghrelin Suppresses Insulin Secretion in Human Islets and Type 2 Diabetes Patients Have Diminished Islet Ghrelin Cell Number and Lower Plasma Ghrelin Levels. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020, 511, 110835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Østergård, T.; Hansen, T.; Nyholm, B.; Gravholt, C.; Djurhuus, C.; Hosoda, H.; Kangawa, K.; Schmitz, O. Circulating Ghrelin Concentrations Are Reduced in Healthy Offspring of Type 2 Diabetic Subjects, and Are Increased in Women Independent of a Family History of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetologia 2003, 46, 134–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsuki, A.; Urakawa, H.; Gabazza, E.; Murashima, S.; Nakatani, K.; Togashi, K.; Yano, Y.; Adachi, Y.; Sumida, Y. Circulating Levels of Active Ghrelin Is Associated with Abdominal Adiposity, Hyperinsulinemia and Insulin Resistance in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2004, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, H.; Shiiya, T.; Mizuta, M.; Mondal, M.; Nakazato, M. Plasma Ghrelin Concentrations in Different Clinical Stages of Diabetic Complications and Glycemic Control in Japanese Diabetics. Endocr. J. 2007, 54, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, T.D.; Nogueiras, R.; Andermann, M.L.; Andrews, Z.B.; Anker, S.D.; Argente, J.; Batterham, R.L.; Benoit, S.C.; Bowers, C.Y.; Broglio, F.; et al. Ghrelin. Mol. Metab. 2015, 4, 437–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyasu, H.; Takaya, K.; Tagami, T.; Ogawa, Y.; Hosoda, K.; Akamizu, T.; Suda, M.; Koh, T.; Natsui, K.; Toyooka, S.; et al. Stomach Is a Major Source of Circulating Ghrelin, and Feeding State Determines Plasma Ghrelin-Like Immunoreactivity Levels in Humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 4753–4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.P.; Gao, Y.; Geng, L.; Brimijoin, S. Butyrylcholinesterase Regulates Central Ghrelin Signaling and Has an Impact on Food Intake and Glucose Homeostasis. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satou, M.; Nishi, Y.; Yoh, J.; Hattori, Y.; Sugimoto, H. Identification and Characterization of Acyl-Protein Thioesterase 1/Lysophospholipase I As a Ghrelin Deacylation/Lysophospholipid Hydrolyzing Enzyme in Fetal Bovine Serum and Conditioned Medium. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 4765–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, P.; Yang, C.-H.; Liu, J.; Lei, H.-Y.; Wang, W.; Guo, Q.-Y.; Lu, B.; Shao, J.-Q. Relationship Between Acyl and Desacyl Ghrelin Levels with Insulin Resistance and Body Fat Mass in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 2763–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, N.; Hölscher, C. Acylated Ghrelin as a Multi-Targeted Therapy for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 614828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C.O.D.; Montenegro, R.M.; Pedroso, A.P.; Fernandes, V.O.; Montenegro, A.P.D.R.; De Carvalho, A.B.; Oyama, L.M.; Maia, C.S.C.; Ribeiro, E.B. Altered Acylated Ghrelin Response to Food Intake in Congenital Generalized Lipodystrophy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shati, A.A.; Khalil, M.A. Acylated Ghrelin Suppresses Doxorubicin-Induced Testicular Damage and Improves Sperm Parameters in Rats via Activation of Nrf2 and Mammalian Target of Rapamycin. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2023, 19, 1194–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, L.H.; Hage, C.; Pironti, G.; Thorvaldsen, T.; Ljung-Faxén, U.; Zabarovskaja, S.; Shahgaldi, K.; Webb, D.-L.; Hellström, P.M.; Andersson, D.C.; et al. Acyl Ghrelin Improves Cardiac Function in Heart Failure and Increases Fractional Shortening in Cardiomyocytes without Calcium Mobilization. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2009–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, N. Expression, Regulation and Biological Actions of Growth Hormone (GH) and Ghrelin in the Immune System. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2009, 19, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, N.; Saito, T.; Yagyu, T.; Jiang, B.-H.; Kitagawa, K.; Inagaki, C. GH, GH Receptor, GH Secretagogue Receptor, and Ghrelin Expression in Human T Cells, B Cells, and Neutrophils. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 4284–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaštelan, S.; Tomić, M.; Gverović Antunica, A.; Salopek Rabatić, J.; Ljubić, S. Inflammation and Pharmacological Treatment in Diabetic Retinopathy. Mediators Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef Moursy, E. Relationship Between Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio and Microvascular Complications in Egyptian Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Am. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 3, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.J.; Ahn, S.J.; Ahn, J.; Park, K.H.; Lee, K. Elevated Systemic Neutrophil Count in Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetes: A Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study of 30,793 Korean Subjects. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socorro Faria, S.; Fernandes Jr, P.C.; Barbosa Silva, M.J.; Lima, V.C.; Fontes, W.; Freitas-Junior, R.; Eterovic, A.K.; Forget, P. The Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio: A Narrative Review. ecancermedicalscience 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, T.T.; Aktas, G.; Atak, B.M.; Kocak, M.Z.; Erkus, E.; Savli, H. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio as an Indicative of Diabetic Control Level in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Afr. Health Sci. 2019, 19, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulu, S.M.; Dogan, M.; Ahsen, A.; Altug, A.; Demir, K.; Acartürk, G.; Inan, S. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Quick and Reliable Predictive Marker to Diagnose the Severity of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2013, 15, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Yu, K. Neutrophil–Lymphocyte Ratio Is Associated with Arterial Stiffness in Diabetic Retinopathy in Type 2 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Complications 2015, 29, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Quan, J.; Wei, S.; An, S.; Yang, R.; Liu, J. The Association of Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio, Mean Platelet Volume, and Platelet Distribution Width with Diabetic Retinopathy and Nephropathy: A Meta-Analysis. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR20180172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imazu, Y.; Yanagi, S.; Miyoshi, K.; Tsubouchi, H.; Yamashita, S.; Matsumoto, N.; Ashitani, J.; Kangawa, K.; Nakazato, M. Ghrelin Ameliorates Bleomycin-Induced Acute Lung Injury by Protecting Alveolar Epithelial Cells and Suppressing Lung Inflammation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 672, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.H.; Parodo, J.; Kapus, A.; Rotstein, O.D.; Marshall, J.C. Dynamic Regulation of Neutrophil Survival through Tyrosine Phosphorylation or Dephosphorylation of Caspase-8. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 5402–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baatar, D.; Patel, K.; Taub, D.D. The Effects of Ghrelin on Inflammation and the Immune System. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 340, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, V.D.; Taub, D.D. Ghrelin and Immunity: A Young Player in an Old Field. Exp. Gerontol. 2005, 40, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.; Zhao, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Du, J.; Tang, C. Therapeutic Effects of Ghrelin on Endotoxic Shock in Rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 473, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Dong, W.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, F.; Marini, C.P.; Ravikumar, T.S.; Wang, P. Ghrelin Attenuates Sepsis-Induced Acute Lung Injury and Mortality in Rats. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 176, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado, M.; Priego, T.; Martín, A.I.; Villanúa, M.Á.; López-Calderón, A. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of the Ghrelin Agonist Growth Hormone-Releasing Peptide-2 (GHRP-2) in Arthritic Rats. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 288, E486–E492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Rizo, V.; Martínez-Guzmán, M.A.; Iñiguez-Gutierrez, L.; García-Orozco, A.; Alvarado-Navarro, A.; Fafutis-Morris, M. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Its Implications in Inflammation: An Overview. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobjeva, N.V.; Chernyak, B.V. NETosis: Molecular Mechanisms, Role in Physiology and Pathology. Biochem. Mosc. 2020, 85, 1178–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Hong, W.; Wan, M.; Zheng, L. Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Target of NETosis in Diseases. MedComm 2022, 3, e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papayannopoulos, V. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Immunity and Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Z. Impact of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps on Thrombosis Formation: New Findings and Future Perspective. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 910908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Guo, P.; Hao, X.; Sun, X.; Feng, H.; Chen, Z. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs): A New Therapeutic Target for Neuroinflammation and Microthrombosis After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage? Transl. Stroke Res. 2023, 14, 443–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, N.; Üstunkaya, T.; Feener, E. Thrombosis and Hemorrhage in Diabetic Retinopathy: A Perspective from an Inflammatory Standpoint. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2015, 41, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.H.; Park, S.-J.; Han, S.; Song, J.H.; Lee, K.; Chung, Y.-R. Potent Oral Hypoglycemic Agents for Microvascular Complication: Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors for Diabetic Retinopathy. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern® Guidelines. Diabetic Retinopathy. 2014.

- Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Li, Z.; Gong, Y. The Role of Acylated Ghrelin and Unacylated Ghrelin in the Blood and Hypothalamus and Their Interaction with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2020, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CTRL | Diabetic | NPDR | PDR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (N) | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Male (N) | 6 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| Mean age (years ± SD) | 64.2 ± 9 | 65.5 ± 6 | 69.9 ± 7 | 70.1 ± 5 |

| Age range (years) | 54-74 | 58-74 | 52-82 | 65-77 |

| Type I diabetes (%) | NA | 25 | 42 | 57 |

| Type II diabetes (%) | NA | 75 | 58 | 43 |

| Mean diabetes duration (years ± SD) | NA | 6.0 ± 0.8 | 6.8 ± 1 | 7.8 ± 1.1 |

| Mean time from DR diagnosis (years ± SD) |

NA | NA | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.4 |

| Glycaemia (mg/dl) normal range (70-100 mg/dl) |

82 ± 15 | 140.2 ± 25** | 142.4 ± 20** | 200 ± 25°^ |

| Neutrophils (%± SD) normal range (40-70%) |

43.9 ± 2 | 45.4 ± 4 | 50.8 ± 5°° | 61.2 ± 3°°^^ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).