Submitted:

17 November 2023

Posted:

17 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

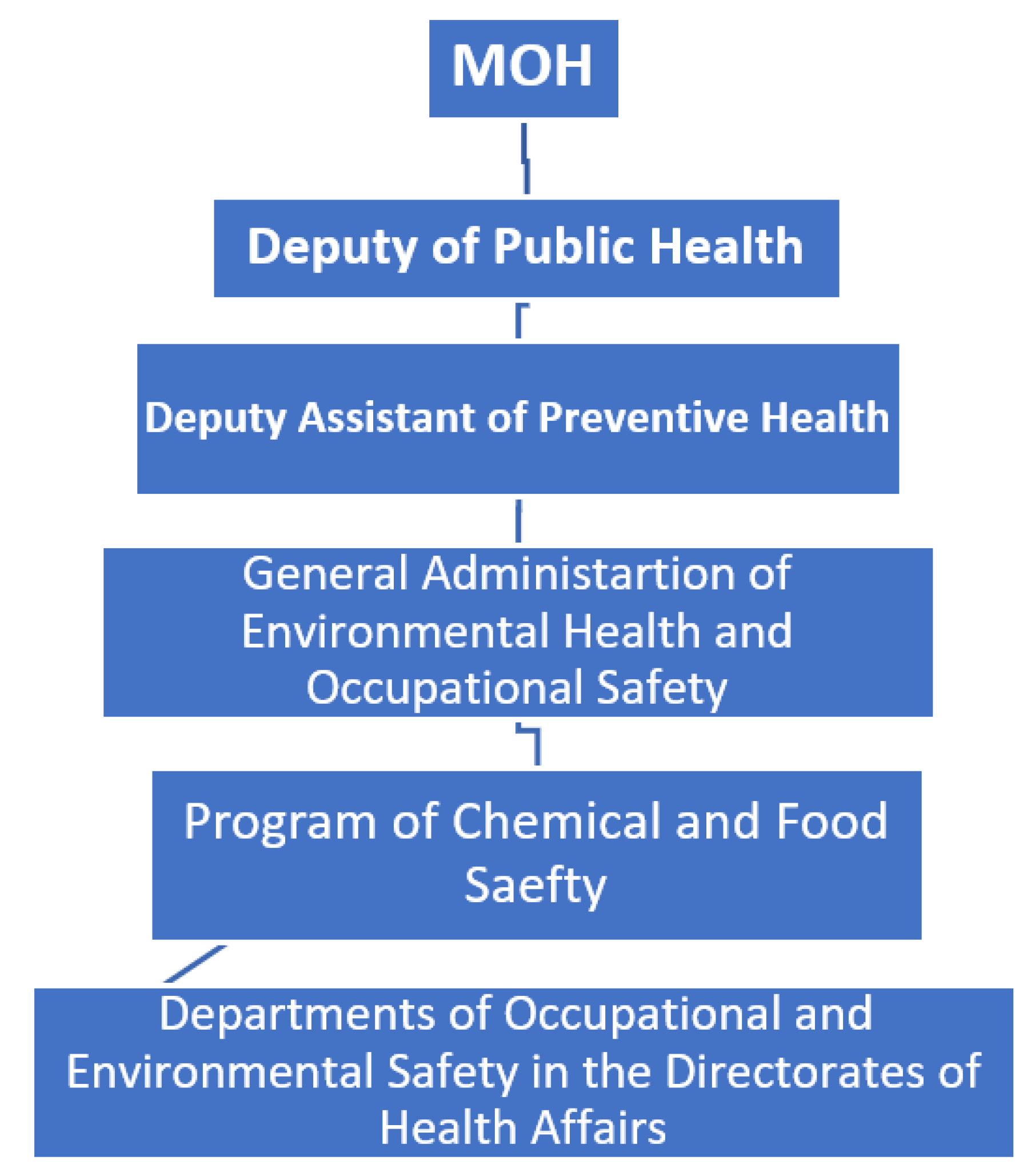

1. Introduction:

1.1. Background:

- Collaboration with the relevant sectors.

- Risk assessment for chemical substances.

- Review for the laws and guidelines legislating safe dealing with the chemical substances.

- Continuous monitoring for the reporting system.

- Representing the Ministry of Health in meetings with pertinent sectors in all matters related to chemical and drug poisoning.

- Ensure the compliance of different sectors with the regulations of the drug and chemical safety program.

- Dissemination of the decrees governing adherence to the regulations of the program.

- Reviewing, monitoring and follow up for all the cases of chemical and drug poisoning occurring all over the Kingdom.

- Receiving all reports and notifications from all directorates in the Kingdom.

- Confirm uploading all relevant data received from the regions on the Health Electronic Surveillance Network (HESN) designated for this purpose.

- Immediate to the Deputy of Public Health about mortality cases together with the laboratory and the forensic reports.

- Preparing the annual statistics about all chemical and drug poisoning occur all over the Kingdom.

- Collaboration with other sectors in conducting field inspection on the shops dealing with chemical substances and insecticides and companies specialized in insect and rodent control.

- Training and continuous education.

- Training of all employees serving in the program about Health Electronic Surveillance Network (HESN).

- Training workers in the regions about surveillance of the chemical and drug poisoning and documentation of the data either on paper or electronic programs.

- Preparing health education materials disseminated for the regions to increase awareness of the workers as well as the community about risks of chemical and drug poisoning and how to prevent it.

- Prepare and disseminate updated scientific materials to the workers in the regions.

- Regular meetings with coordinators of the regions.

- Regular field visits to health institutes in different regions encourage notification of poison cases.

1.3. Tasks and responsibilities of the regional Departments of Environmental Health and Occupational Safety regarding chemical and drug poisoning:

- Act as a liaison for disseminating the regulations set at the ministerial level to all governmental and private sectors and ensuring adherence to these regulations.

- Monitoring timeliness and accuracy of the reporting system and perform regular supervisory visits to the reporting health institutes in the region.

- Receiving, organizing and saving all reports sent from the hospitals.

- Immediate for any mortalities, cases of group poisoning and cases of methanol or aluminum phosphide poisoning to the central Program of Chemical and Drug safety at the MOH.

- Preparing and submitting a monthly report for all drug and chemical poisoning cases occur in the region to the central program at the MOH.

- Preparing and submitting an annual report for all drug and chemical poisoning cases occur in the region to the central program at the MOH.

- Active participation of the primary health care centers should be ensured in providing health education about protective measures against chemical and drug poisoning accidents.

- Organizing and sharing in training activities regarding awareness about the notification system for chemical and drug poisoning incidents.

1.4. Responsibilities of the notifying health institute:

- On arrival of the case and suspicion of chemical or drug poisoning, the relevant form should be completed by the treating physician and the health inspector.

- The physician is responsible for collecting the appropriate sample from the case (blood, urine, gastric lavage, etc.) depending on the type of poisoning.

- The samples were sent to the laboratory of chemical and forensic poisoning in the region.

-

Notifying the coordinator of the program of chemical and drug safety in the region according to the following time ranges:

- ○

- If the incident occurs in only one case, which is stable, the form should be sent within one week together with the laboratory results.

- ○

- If the incident occurs in a group of cases, notification should be instant to the regional coordinator.

- ○

- Mortalities should be notified at once to the regional coordinator.

- ○

- Additionally, cases of methanol and aluminum phosphide poisoning should be notified immediately to the regional coordinator.

- The notifying health institute should keep forms and reports about the poisoning cases and send copies for the coordinator in the region as well as the primary health care center in the catchment area of the case.

- The health inspector in the institute is responsible for follow-up of the laboratory investigation results conducted in the hospital or any other laboratories.

- A full report about the case and forensic report (in case of mortality) should be sent to the regional coordinator after completing the case.

1.5. Rationale of the study:

1.6. Aim of the study:

1.7. Objective(s) of the study:

- To describe the notification and reporting system in the environmental health and occupational safety department in the public health directorate in Makkah Almukarramah.

2. Review of Literature:

2.1. International studies:

2.2. Studies in Saudi Arabia:

3. Material and methods:

3.1. Study setting:

3.2. Study population:

3.3. Data collection and statistical analysis:

3.4. Ethical consideration:

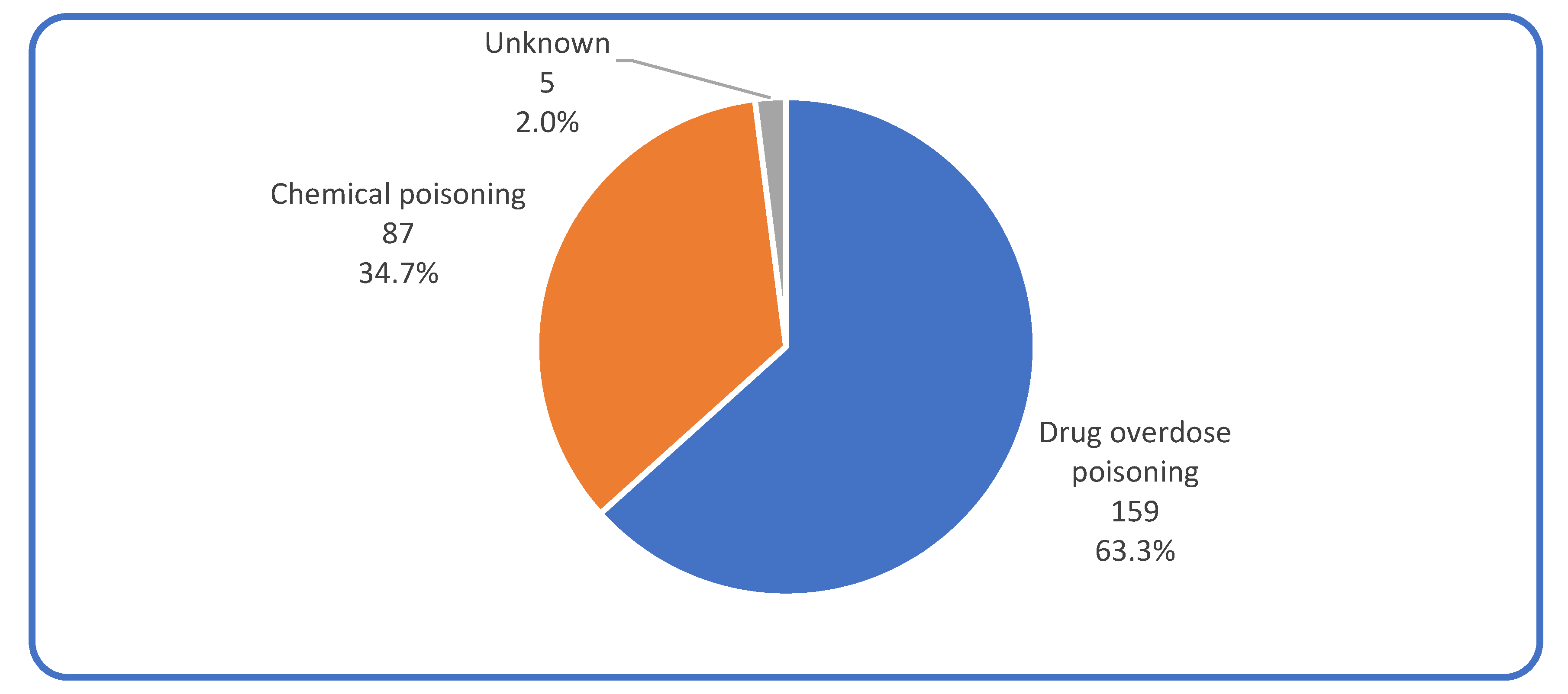

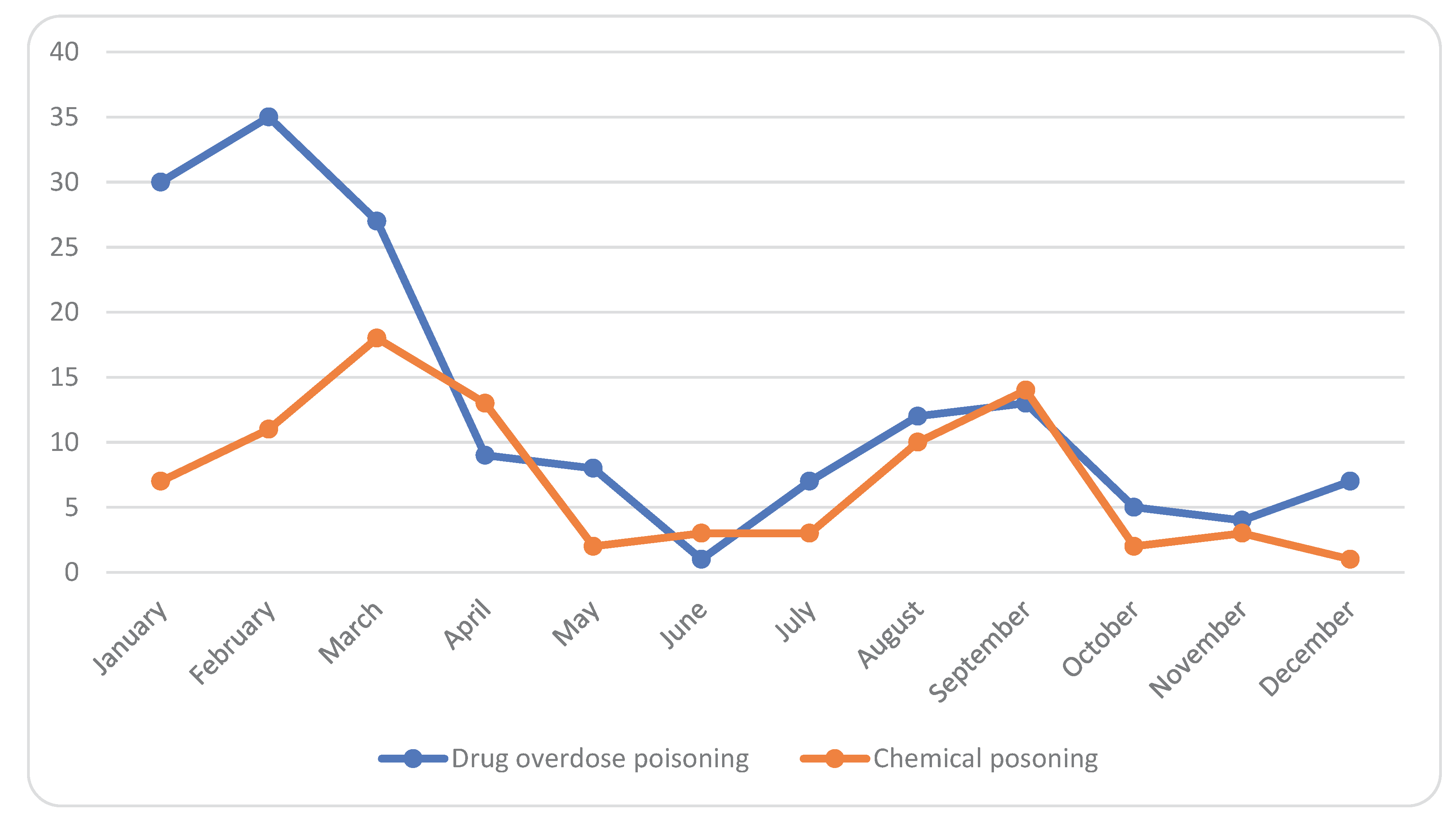

4. Results:

4.1. Characteristics of the cases:

4.2. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the cases:

5. Discussion:

6. Conclusion and recommendations:

References

- WHO, “WHO | Poisoning Prevention and Management,” 2016.

- Ramesha, K.B. Rao, and G.S. Kumar, Pattern and outcome of acute poisoning cases in a tertiary care hospital in Karnataka, India. Indian journal of critical care medicine: peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine, 2009. 13(3): p. 152. [CrossRef]

- “OED Environmental Outlook for the Chemical Industry.”. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/env/ehs/2375538.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- “King Fahad medical city Poison control department,” 2016. Available online: https://www.kfmc.med.sa/EN/Patient/Poison-Control/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- Martins, S.S., et al., Worldwide prevalence and trends in unintentional drug overdose: a systematic review of the literature. American journal of public health, 2015. 105(11): p. e29-e49. [CrossRef]

- Bakhaidar, M., et al., Pattern of drug overdose and chemical poisoning among patients attending an emergency department, western Saudi Arabia. Journal of community health, 2015. 40(1): p. 57-61. [CrossRef]

- Teklemariam, E., S. Tesema, and A. Jemal, Pattern of acute poisoning in Jimma University specialized hospital, south West Ethiopia. World journal of emergency medicine, 2016. 7(4): p. 290. [CrossRef]

- Malangu, N. and G. Ogunbanjo, A profile of acute poisoning at selected hospitals in South Africa. Southern African Journal of Epidemiology and Infection, 2009. 24(2): p. 14-16.

- Al-Barraq, A. and F. Farahat, Pattern and determinants of poisoning in a teaching hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, 2011. 19(1): p. 57-63. [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, S.H., et al., Five-year epidemiological trends for chemical poisoning in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Annals of Saudi medicine, 2017. 37(4): p. 282-289. [CrossRef]

- Moazzam, M., et al., Pattern of acute poisoning in Al-Qassim region: a surveillance report from Saudi Arabia, 1999-2003. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 15 (4), 1005-1010, 2009.

- Abd-Elhaleem, Z.A.E. and B. Al Muqhem, Pattern of acute poisoning in Al Majmaah region, Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Med, 2014. 4(2): p. 79-85. [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, R. and W. Almalki, Pattern of acute poisoning in makkah region saudi arabia, 2009-2011. In presentations from the 22nd Congress of the ilam (July 5-8, 2012, Istanbul, Turkey). 2012.

- Kaale, E., et al., A retrospective study of poisoning at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar-Es Salaam, Tanzania. J Public Health Front, 2013. 2(1): p. 21-26.

- Wang, L.-J., et al., The trend in morning levels of salivary cortisol in children with ADHD during 6 months of methylphenidate treatment. Journal of attention disorders, 2017. 21(3): p. 254-261. [CrossRef]

- Gummin, D.D., et al., 2017 Annual report of the American Association of Poison control centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 35th annual report. Clinical toxicology, 2018. 56(12): p. 1213-1415.

- Sharma, B., et al., Toxicological emergencies and their management at different health care levels in Northern India-An overview. Journal of Pharmacology & Toxicology, 2010. 5(7): p. 418-430.

- Bakar, M., S. Ahsan, and P. Chowdhury, Acute poisoning-nature and outcome of treatment in a teaching hospital. Bangladesh Med J (Khulna), 1999. 32(1): p. 19-21.

- Izuora, G.I. and A. Adeoye, A seven-year review of accidental poisoning in children at a military hospital in Hafr Al Batin, Saudi Arabia. Annals of Saudi medicine, 2001. 21(1-2): p. 13-15. [CrossRef]

- El-Mouzan, M., A. Elaged, and N. Ali, Accidental poisoning of children in the Eastern Province. Saudi medical journal, 1986. 7(3): p. 231-236.

- Asiri, Y.A., et al., Evaluation of drug and poison information center in Saudi Arabia during the period 2000-2002. Saudi medical journal, 2007. 28(4): p. 617-619.

- AL-Nsour, T.S. and K.A. Hadidi, Investigating the presence of a common drug of abuse (benzhexol) in hair; the Jordanian experience. Journal of clinical forensic medicine, 2002. 9(3): p. 119-125. [CrossRef]

- Gossel, T.A., Principles of clinical toxicology. 2018: CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Branche, C., et al., World report on child injury prevention. 2008.

| Year | Gender | Mortality rate/100,000 |

| 2000 | Both (males and females) | 1.300 |

| Males | 1.500 | |

| Females | 1.00 | |

| 2005 | Both (males and females) | 1.00 |

| Males | 1.20 | |

| Females | 0.80 | |

| 2010 | Both (males and females) | 0.90 |

| Males | 1.0 | |

| Females | 0.70 | |

| 2015 | Both (males and females) | 0.70 |

| Males | 0.80 | |

| Females | 0.50 | |

| 2016 | Both (males and females) | 0.70 |

| Males | 0.80 | |

| Females | 0.50 |

| Characteristics | No. | % |

| Nationality: | ||

| Saudi | 230 | 91.6 |

| Non Saudi | 21 | 8.4 |

| Gender: | ||

| Male | 144 | 57.4 |

| Female | 107 | 42.6 |

| Age: | ||

| <1 year | 10 | 4.0 |

| 1-5 years | 128 | 51.0 |

| 6-12 years | 16 | 6.4 |

| 13-19 years | 27 | 10.8 |

| 20-39 years | 53 | 21.1 |

| 40+ years | 17 | 6.8 |

| Characteristics | Types of poisoning | |||||

| Drug overuse poisoning | Chemical poisoning | X2 | p | |||

| No | % | No | % | |||

| Nationality: | 2.685 | 0.101 | ||||

| Saudi | 150 | 66.1% | 77 | 33.9% | ||

| Non Saudi | 9 | 47.4% | 10 | 52.6% | ||

| Gender: |

1.461 |

0.227 |

||||

| Male | 86 | 61.4% | 54 | 38.6% | ||

| Female | 73 | 68.9% | 33 | 31.1% | ||

| Age: |

25.925 |

<0.001* |

||||

| < 1 year | 7 | 70.0% | 3 | 30.0% | ||

| 1-5 years | 67 | 52.8% | 60 | 47.2% | ||

| 6-12 years | 8 | 50.0% | 8 | 50.0% | ||

| 13-19 years | 25 | 96.2% | 1 | 3.8% | ||

| 20-39 years | 38 | 76.0% | 12 | 24.0% | ||

| 40+ years | 14 | 82.4% | 3 | 17.6% | ||

| Medicines’ categories | Frequency |

| Analgesic Antipyretic or Anti-inflammatory | 48 |

| Antiepileptic | 17 |

| Anti-Hypertensive | 13 |

| Antipsychotic | 12 |

| Anti-Histaminic | 9 |

| Antibiotic | 7 |

| Vitamins | 6 |

| Anti-emetic | 6 |

| Anti-diabetic | 5 |

| Contraceptive | 4 |

| Anti-Asthmatic | 2 |

| Iron Preparations | 1 |

| Unknown | 7 |

| Others | 16 |

| Chemical substances | Frequency |

| Cleansing Substance | 30 |

| Disinfectant | 17 |

| Insecticide | 8 |

| Antiseptic | 2 |

| Carbon Monoxide | 1 |

| Fuel | 1 |

| Unknown | 5 |

| Other | 19 |

| Types of poisoning | ||||||

| Drug overuse poisoning | Chemical poisoning | X2 | P | |||

| No | % | No | % | |||

| Circumstances: | 39.512 | <0.001* | ||||

| Accidental | 81 | 52.3% | 80 | 92.0% | ||

| Intentional | 25 | 16.1% | 3 | 3.4% | ||

| Unknown | 49 | 31.6% | 4 | 4.6% | ||

| Physical form: |

141.338 |

<0.001* |

||||

| Solid | 140 | 92.1% | 14 | 16.1% | ||

| Liquid | 12 | 7.9% | 56 | 64.4% | ||

| Gas | 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 11.5% | ||

| Powder | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 8.0% | ||

| Route of administration: |

16.314 |

<0.001* |

||||

| Oral | 151 | 98.1% | 78 | 90.7% | ||

| Injection | 3 | 1.9% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Inhalation | 0 | 0.0% | 8 | 9.3% | ||

| Circumstances of poisoning | ||||||

| Accidental | Intentional | X2 | p | |||

| No | % | No | % | |||

| Gender: | 6.852 | 0.009* | ||||

| Males | 92 | 56.8% | 8 | 29.6% | ||

| Females | 70 | 43.2% | 19 | 70.4% | ||

| Age: |

NA |

NA |

||||

| <13 years | 146 | 90.1% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| 13-19 years | 2 | 1.2% | 13 | 48.1% | ||

| 20-39 years | 12 | 7.4% | 13 | 48.1% | ||

| 40+ years | 2 | 1.2% | 1 | 3.7% | ||

| Type of poisoning: |

13.956 |

<0.001* |

||||

| Drug overdose poisoning | 81 | 50.3% | 24 | 88.9% | ||

| Chemical poisoning | 80 | 49.7% | 3 | 11.1% | ||

| Clinical condition | Frequency | % |

| Symptoms | ||

| Vomiting | 35 | 26.7 |

| Nausea | 30 | 22.9 |

| Abdominal pain | 16 | 12.2 |

| Headache | 15 | 11.5 |

| Difficulty in breathing | 12 | 9.2 |

| Dizziness | 7 | 5.3 |

| Loss of consciousness | 4 | 3.1 |

| Disorientation | 3 | 2.3 |

| Weakness | 2 | 1.5 |

| Blurred vision | 2 | 1.5 |

| Seizures | 2 | 1.5 |

| Fever | 1 | 0.8 |

| Skin rashes | 1 | 0.8 |

| Coma | 1 | 0.8 |

| Condition | ||

| Stable | 245 | 97.6 |

| Deteriorated | 6 | 2.4 |

| Management | ||

| Admitted to the hospital | 107 | 44.2 |

| Discharge against medical advice | 62 | 25.6 |

| Not admitted | 73 | 30.2 |

| Laboratory Investigations | ||

| Blood sample hospital lab | 164 | 65.3 |

| Blood sample toxicological | 93 | 37.1 |

| Urine sample hospital lab | 28 | 11.2 |

| Urine sample toxicological | 17 | 6.8 |

| Gastric lavage hospital lab | 33 | 13.1 |

| Gastric lavage toxicological | 15 | 6.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).