1. Introduction

Enthusiasm on the super-hardness of diamond-like carbon (DLC) films is fading during their industrial applications, and toughness issue once-neglected is gradually emerging. Since Aisenberg et al. synthesized DLC films using low-energy carbon ion beam, hard hydrogen-free DLC films have drawn an intensive attention due to their high hardness, smooth surface, and good corrosion resistance [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The hard DLC films present a broad prospect as a good tribological film in the green precision manufacturing industry [

6,

7,

8,

9]. The industry demands urge the DLC films to have both high hardness and high toughness. Improving the toughness of hard DLC films has been regarded as a major influence on surface modification of precision components [

10]. Poor toughness is an inherent shortcoming of DLC films [

11]. This “bottleneck” issue directly affects their industrial applications [

12,

13]. Toughness is one of the fundamental mechanical properties. A film toughness involves the film cohesion and impact load resistance. The toughness may reflect the resistance ability of the formation of cracks due to the stress accumulation in the vicinity of the defects [

14,

15,

16]. A film of high toughness shares both a high resistance to crack initiation and a high energy absorption rate to prevent crack propagation, so as to avoid serious failures, such as film damage and peeling during usage. A low toughness may lead to a catastrophic failure and even accident for the equipment, as well as huge losses of labor forces and resources [

17,

18,

19]. Using coated bearings commonly used in ultra-deep drilling as an example, only machine halting, drill lifting, and troubleshooting may consume hundreds of thousands of dollars per day [

20].

Poor understanding of the film toughness characterization and toughening mechanism are two huge obstacles in the way of solving the drawback. At present, some indirect methods are available to characterize toughness, either quantitatively or qualitatively. Some proposed to measure film toughness under specific conditions. Five main methods are commonly used: bending, buckling, scratching, indentation, and tensile tests [

21]. Such methods are at the mercy of (1) Film thickness limitation. Fracture toughness cannot be characterized by conventional methods since the film thickness is well below 250 μm; (2) and uncertainty in parameter measurements and inability to accurately define failure [

22,

23]. Consequently, no widely accepted method emerges for characterizing film toughness to date.

With regard to toughening, doping of metal proved to be an effective method to improve toughness of DLC films. The good ductility of doped metal inhibits the initiation and expansion of cracks thus slows down the fracture process [

24,

25,

26]. It is worth noting that the doped non-carbide-forming metal does not react with the carbon in the film, thus directly embeds in the matrix of the DLC as metal particles [

27,

28,

29,

30]. The non-carbide metal may be a better option as compared with its counterpart of the carbide metal. However, a systematical report has not been found on the toughening mechanism of non-carbide metal-doped DLC film.

In this work, we attempt to explore a relatively simple and acceptable characterization method to measure the film toughness. Moreover, we investigate the change patterns of the layer structures during the characterization to reveal the toughening mechanism.

2. Effect of metal doping on toughness

The structure and properties of DLC films depend mainly on their deposition methods and doping components, where the doped metal elements affect the properties of the synthesized films [

31,

32,

33,

34]. The doped metals can be divided into carbide and non-carbide [

35]. The current research mainly focuses on the doping of carbide. The doped metal has a strong ability to bond and form carbide with carbon matrix, such as Ti, but it is difficult to eliminate the problem of brittle and hard film layer, because the carbide formed is essentially a hard phase [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Non-carbide metals and carbon do not react, such as silver and copper, there is no hard phase generation, and the inherent good ductility characteristics of the metal can still be maintained after entering the interior of the film. In addition, the doped particles are in the nanometer scale, which can change the particle arrangement in the amorphous carbon matrix [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44].

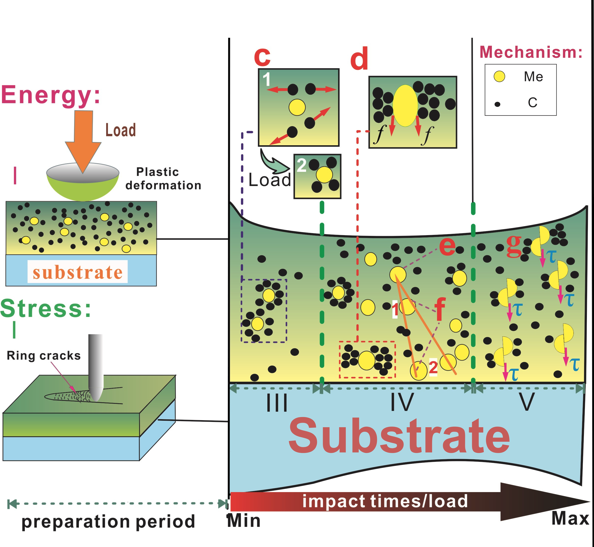

As depicted in

Figure 1, Sui [

45] utilized Closed Field Unbalanced Magnetron Sputter Ion Plating (CFUB-MSIP) to deposit CrN/DLC/Cr-DLC multilayer films. Wear mechanism of as-deposited film is shown in

Figure 1a. Presence of Cr-DLC reduces adhesive wear by creating a lubrication transfer layer between the film and friction pair. Additionally, the inclusion of Cr-DLC inhibits crack propagation, resulting in improved fracture toughness.

Figure 1b illustrates three-dimensional optical profile images of wear tracks. Wear track of CrN/DLC/Cr-DLC film exhibits a distinct appearance compared to both CrN and DLC films. Middle section of the multilayer film’s wear track appears smooth with minimal debris. Frictional data for these films are presented in

Figure 1c. Furthermore,

Figure 1d displays calculated wear rates for each deposited coating type. Remarkably, when compared to single-layered CrN and DLC films, wear rate of multilayer film is significantly reduced by approximately one order of magnitude. These resultant multilayer films consist of amorphous carbon-based layer acting as lubricants alongside hard transition-metal nitride layer. CrN/DLC/Cr-DLC multilayer film exhibits reduction in friction coefficient compared to single CrN film. Enhanced tribological performance of the multi-layer coatings can be primarily attributed to factors such as the incorporation of a lubricant and a robust support layer made of Cr-DLC.

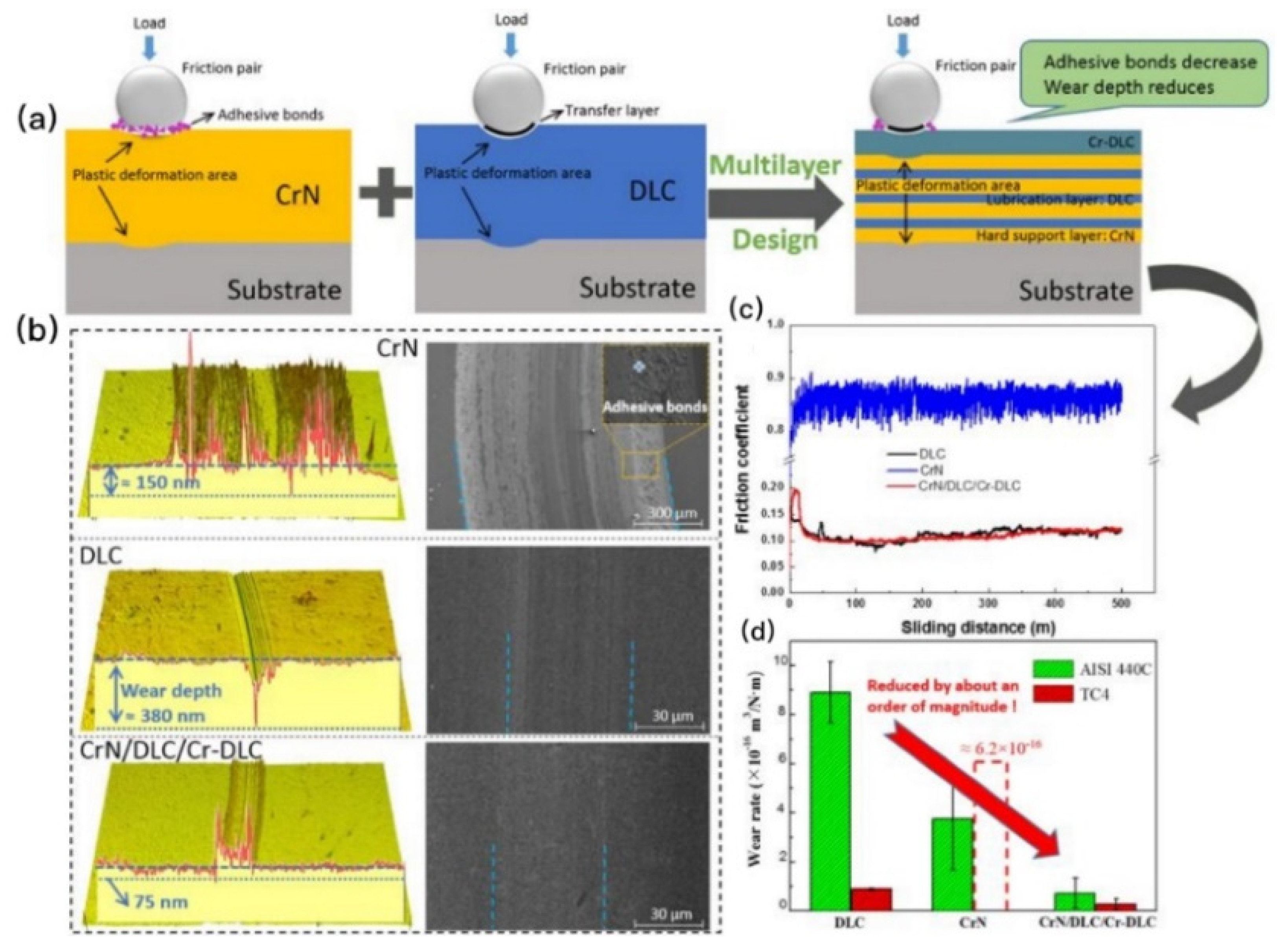

As depicted in

Figure 2, Zhou [

46] utilized ion beam-assisted enhanced unbalanced magnetron sputtering to deposit DLC films with varying levels of Ti doping on a substrate made of 304 stainless steel. The schematic diagram of the frictional mechanism is shown in

Figure 2a. When a small amount of Ti (1.82 wt%) was employed, the introduction of TiC nano-crystallites occurred, enhancing the film hardness and fracture toughness while regulating carbon matrix. Consequently, this led to exceptional performance in terms of tribological behavior. However, an excessive presence of large TiC nano-crystallites within the DLC film can disrupt the three-dimensional structure of carbon and subsequently reduce its hardness and fracture toughness.

The wear rates presented in

Figure 2b exhibit a similar trend as that observed for the friction coefficient. Notably, when examining wear tracks and rates, it becomes evident that the DLC film doped with 1.82 wt% Ti showcased minimal grooves along its track compared to pure DLC film samples. Furthermore, both width and depth measurements indicate smaller grinding cracks for this particular composition, further highlighting its outstanding anti-wear properties. Conversely, increasing levels of Ti doping result in more severe wear marks which signify a decline in wear resistance quality.

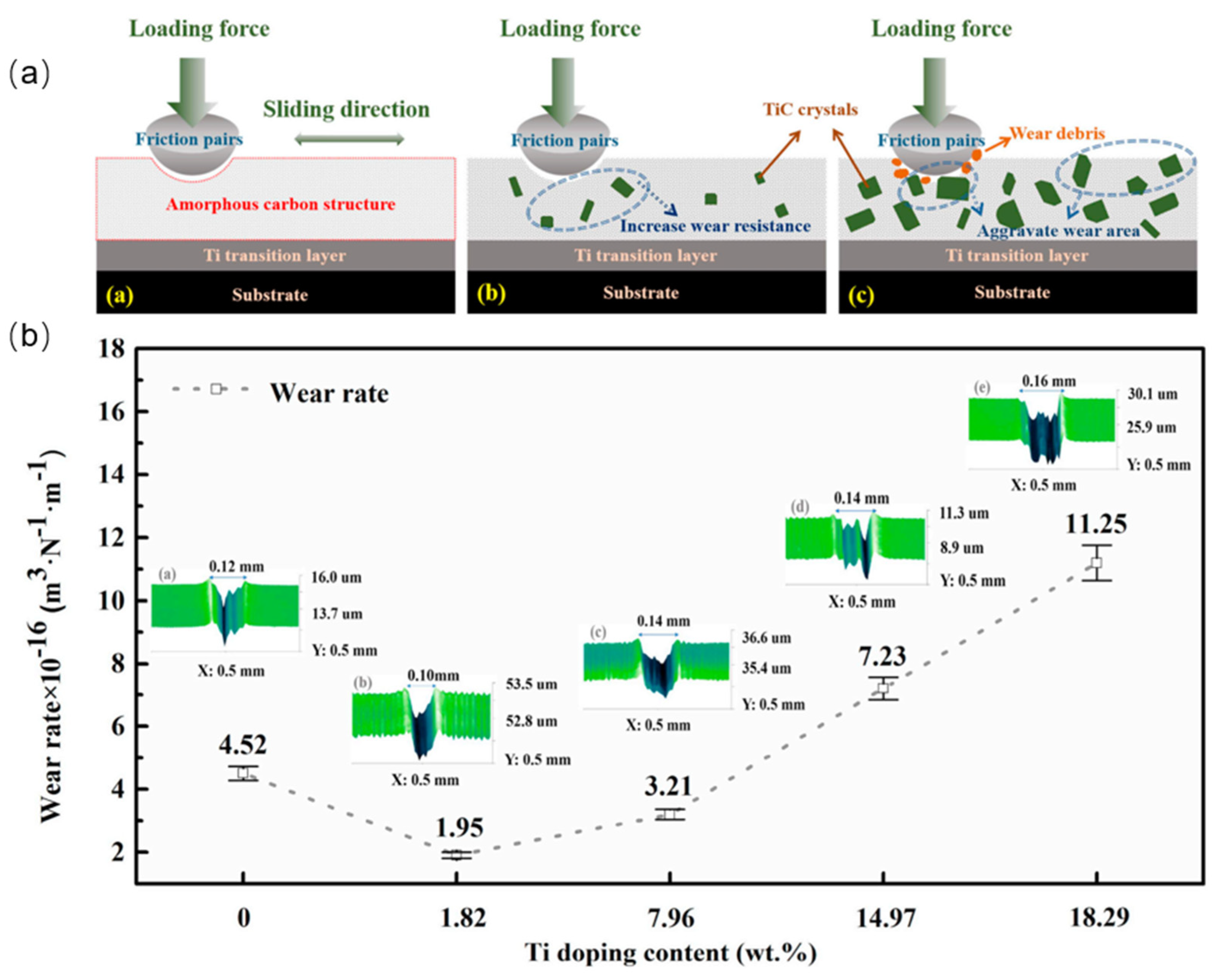

As depicted in

Figure 3, the Cathodic Arc Deposition technique was employed to in-corporate Ag into DLC film with chromium interlayer on surgical stainless steel (SS) [

47].

Figure 3a illustrates the profile of wear scars on both surgical SS and coated surface. Applying Ag-DLC/Cr coating lets the wear rate drop with evidence.

Figure 3b presents SEM micrographs displaying the wear track on both surfaces. In the case of Ag-DLC/Cr, localized tensile cracking occurs in the film at 5 N, and abrasion appears at load of 10 N due to silver-doped DLC and chromium abradant. Post-coating application, there was a four-order decrease in substrate wear rate. Incorporating Ag into the top layer enlarges surface energy which consequently enhanced adhesion strength between layers within the film structure.

It can be concluded from the above analysis that metal doping can effectively improve the friction and wear performance of DLC, and carbide metal will generate carbide hard phase, which leads to high residual stress of film and prone to failure. Non-carbide metal in the appropriate doping range may effectively improve the film toughness, enhance the bonding strength, and increase the lubrication. In this way, we prepared Ag-DLC with gradient doping contents, and characterize the film toughness from two aspects of both energy and pressure.

3. Toughness characterization

The toughness of a DLC film depends on both the energy absorption capacity and cohesive force of the film. In fact, the film toughness relates to the energy states as well as to the stress states of the tips of cracks before and after fracture of a film [

48,

49,

50,

51]. We have to take both energy and stress aspects into account during toughness characterization under complex working conditions. Scratch and impact tests are two preferred methods, owing to their convenience and effectiveness. They also have two drawbacks. (1) Scratch toughness does not really mean toughness, because it is only an indication of toughness [

52]. (2) The data of the impact test may not be reliable because of the uncertainties in the crack length measurement [

53]. Three main uncertainties that may induce deviations during scratch and impact tests are the initial value of crack formation, the substrate influence, and crack length measurement [

54].

3.1. Characterization of impact toughness

Impact test can be conducted to investigate the energy states of a film before and after fracture, and can serve to evaluate film toughness from the energy aspect [

55,

56,

57,

58].

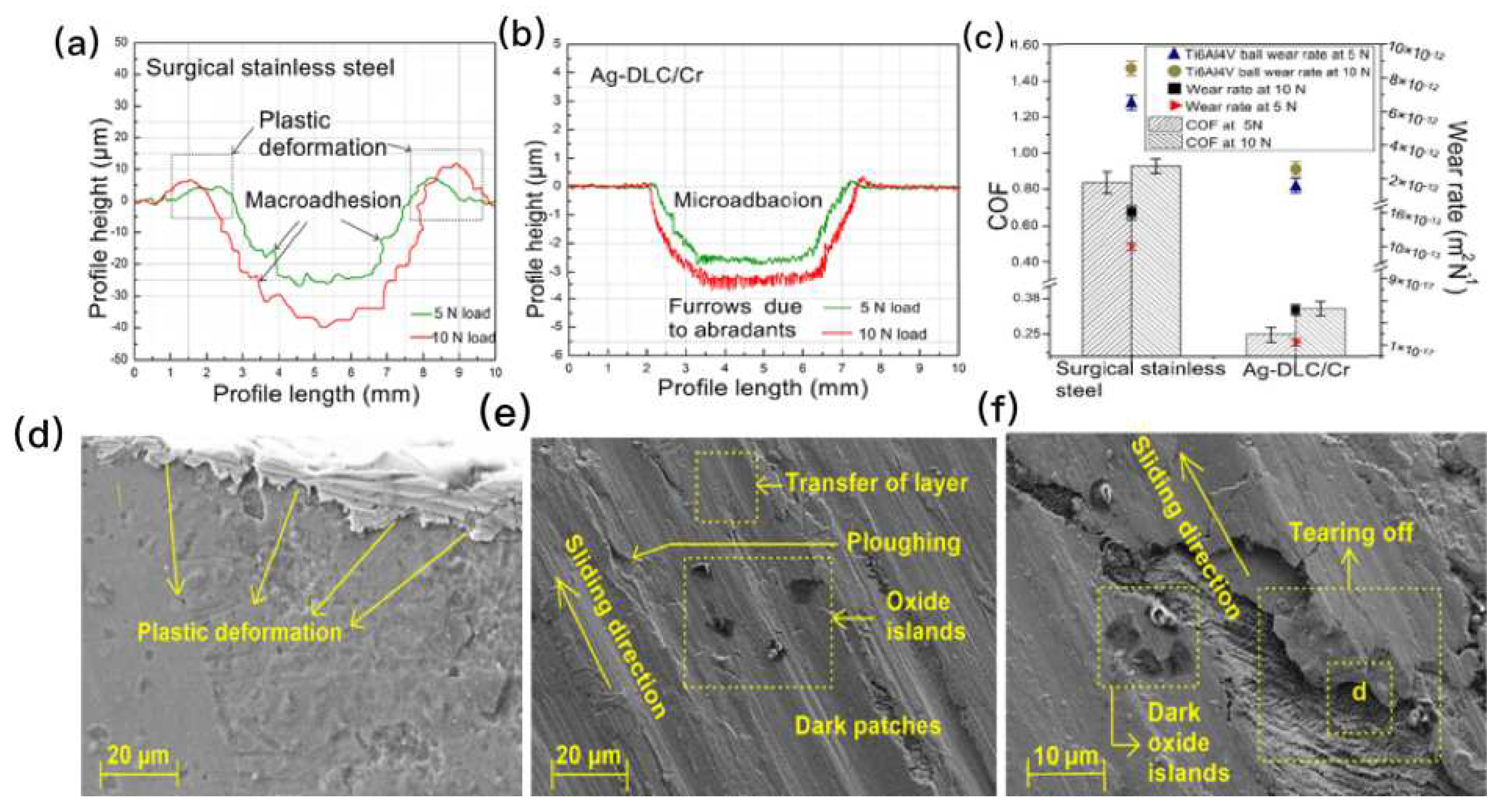

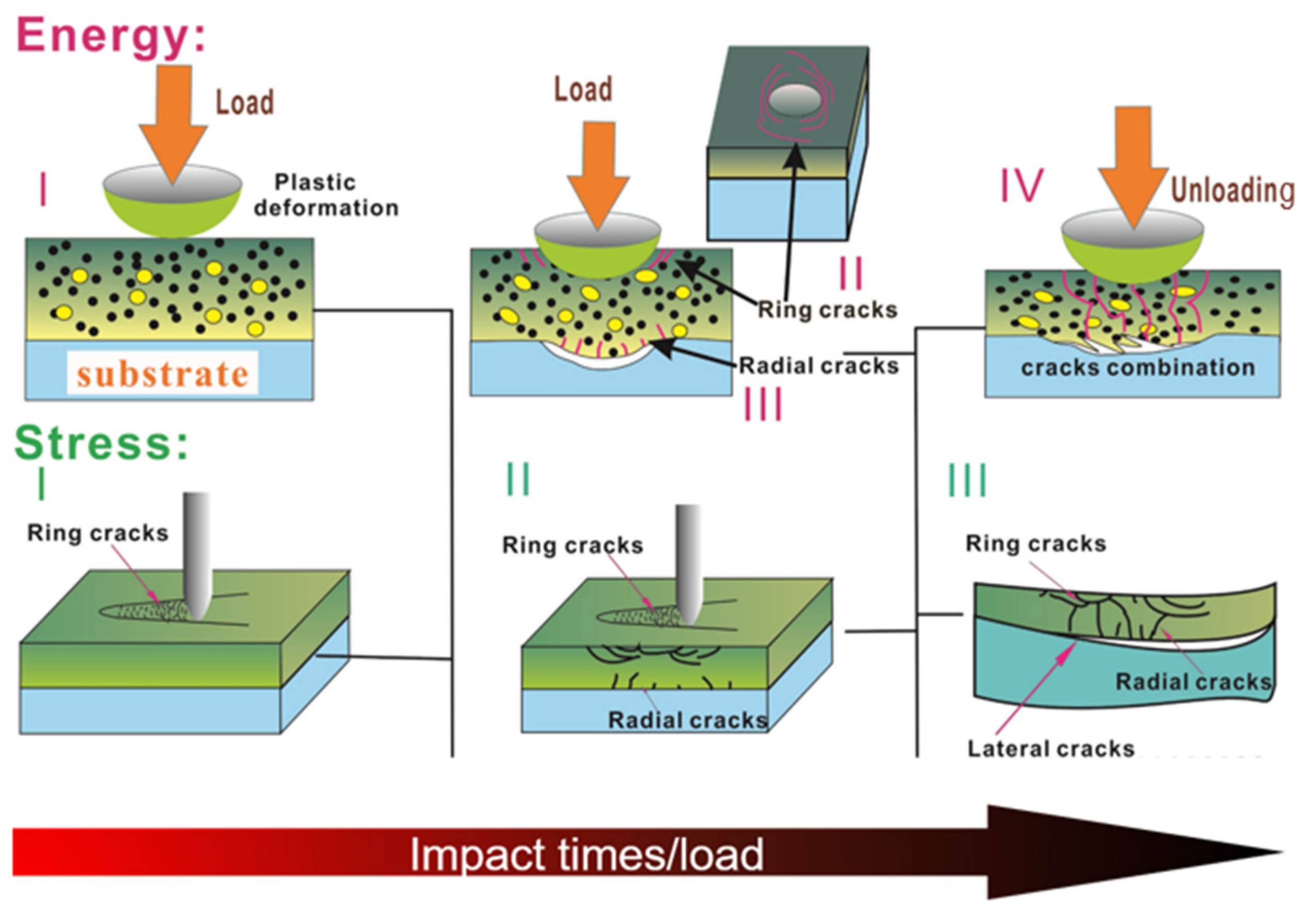

Figure 4-Energy shows the possible failure process of a Me (Metal)-DLC films during impact test, and the failure process of the film can be divided into three stages.

Stage I (

Figure 4-Energy I). The film shows only part of elastic deformation due to few times of impact. Dislocations accumulate at the defects in the edge of plastic deformation region. With increase of impact times (

Figure 1-Energy II), a further accumulation of the energy may let the cracks extend to initiate ring cracks on the upper surface.

Stage II (

Figure 4-Energy III). The accumulation of energy induces the film to start bending. The deformation of the sub-surface of the film is larger than that of the upper surface. Vertical to the film, the radial cracks may initiate on the sub-surface, and propagate from bottom to top.

Stage III (

Figure 4-Energy IV). The energy gathered during loading may continue to provide the energy for crack propagation. The annular and radial cracks may continuously propagate, and their close contact may lead to the film peeling.

Consequently, the continuous energy accumulation results in the ring, radial, and transverse cracks in sequence, as shown in the three stages.

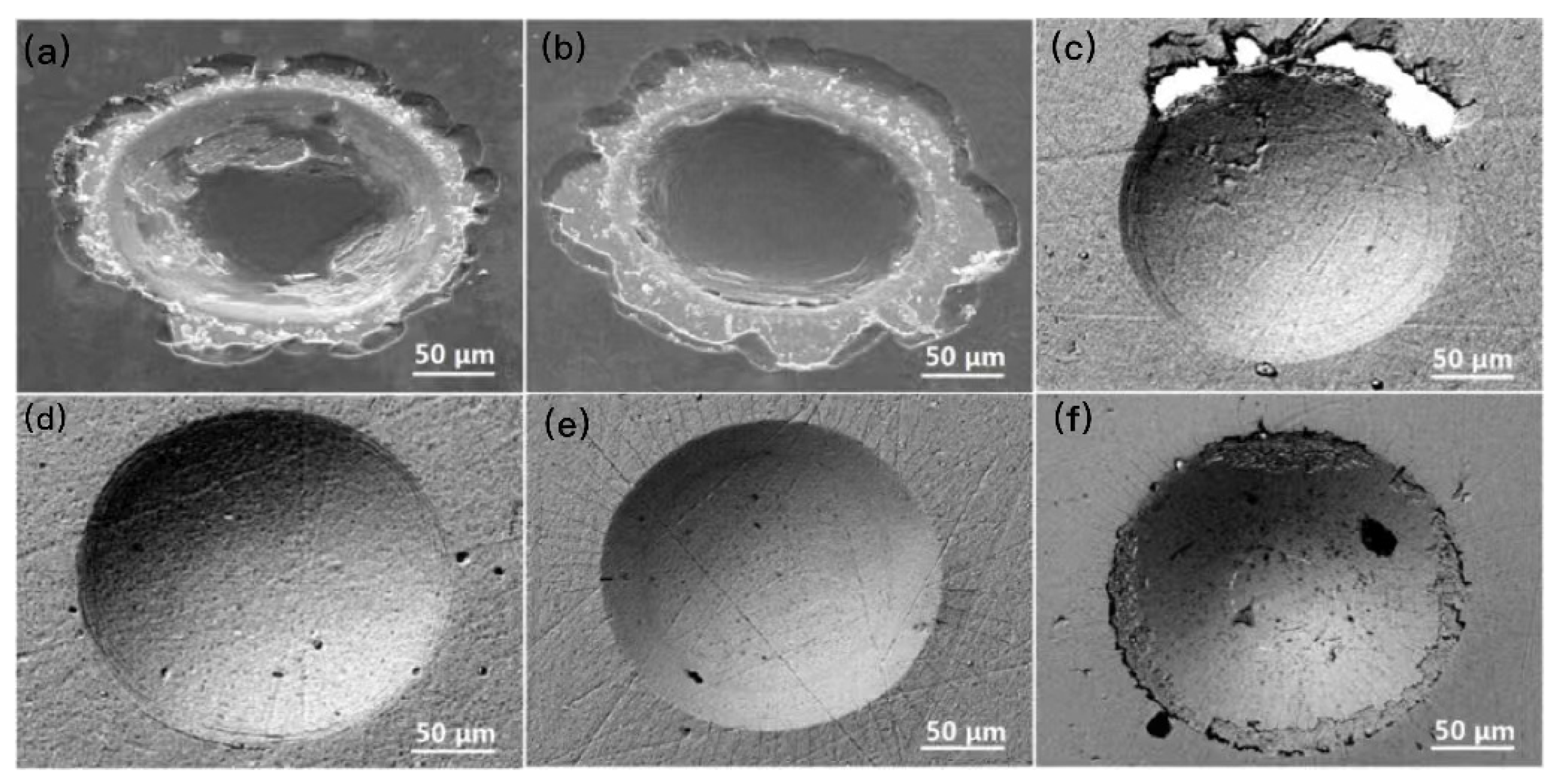

Yu et al. [

59] evaluated the toughness of DLC films with six Ag contents in an impact test, and compared their impact morphologies. Under a driving force of 5 kN, Si

3N

4 ceramic ball was used to impact the film for 2×10

3 times in the test duration. The impact toughness is characterized through jointly observing the morphologies of crack, failure zone and peeling. In addition, doping Ag in the DLC film could improve its toughness, and different Ag contents had different toughening effects.

Figure 5a,b show large white failure regions occurred around the impact cavities since large amounts of circular cracks encounter radial cracks. The two films subject to severe delamination, and have poor toughness. Their cracks undergo evident initiation and propagation during Stages I-III.

Figure 5c,f show that fewer white failure regions and delamination occurred around the impact cavities. The cracks may only initiate at Stage II and propagate during a short period of Stage III. Thus, the two films exhibit moderate toughness.

Figure 5d,e evidence that the impact cavities have clear profiles, and no visible cracks occurred around the impact cavities. We can infer that the two films have good toughness.

Consequently, using impact test may allow to evaluate the ability of film to absorb the impact energy and characterize the impact toughness. The impact energy evaluates the fatigue wear resistance of a DLC film, and the impact test characterizes the impact toughness under loading conditions. The problem is that this method cannot distinguish the films with similar morphologies, such as DLC films doped with 24.6% Ag and 15.2% Ag (

Figure 5d,e). Furthermore, DLC films tend to be used under sliding rather than cyclic loading condition. We thus have to introduce another characterization method, the scratch test.

3.2. Characterization of Scratch Toughness

The scratch test investigates the stress state of a crack tip as follows.

Figure 4-Stress shows a possible failure process of a film during scratch test, and the process can be divided into three stages.

Stage I (

Figure 1-Stress I). The circular cracks initiate behind the indenter when the load reaches the critical load, and propagate in more circular cracks as the pressure increases.

Stage II (

Figure 1-Stress II). The upper surface endures compressive stress, whereas the sub-surface experiences tensile stress. The vertical pressure downward from the indenter may make the radical cracks form at the interface between the film and the substrate.

Stage III (

Figure 1-Stress III). The film may delaminate from the substrate in that the circular cracks encounter the radial cracks to form transverse cracks.

Normally, the initial critical load (L

c1) of the scratch test can be used to evaluate the scratch toughness of the film [

60]. It is worth noting that some films with good toughness may not fail immediately when the L

c1 occurs, but may sustain for a period till the second critical load (L

c2) is reached [

61]. This suggests that the film toughness is also associated with the second critical load (L

c2).

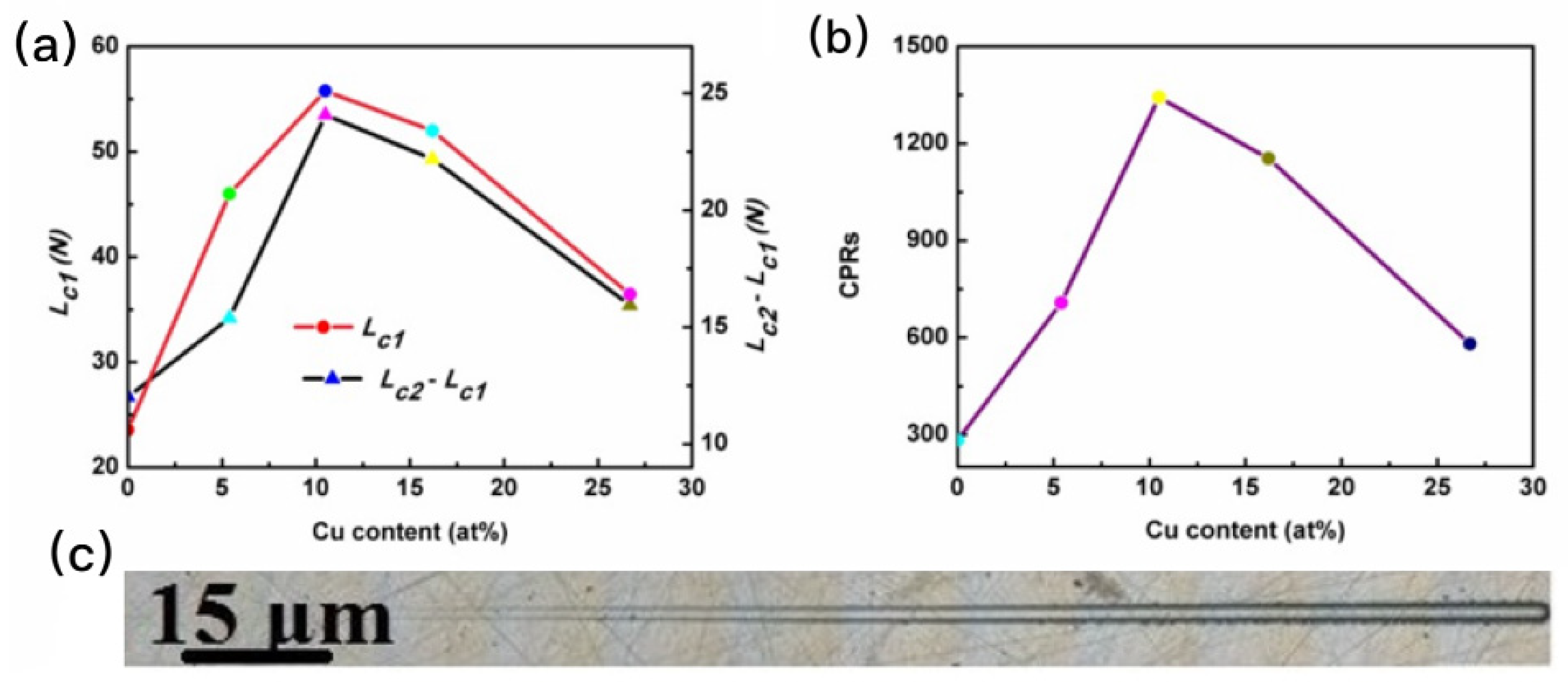

Zhang et al. [

62] indicated that the toughness of a film is directly proportional to L

c1 and the difference between L

c1 and L

c2, and introduced CPRs (Crack Propagation Resistance) to characterize the scratch toughness. CPRS can quantitatively evaluate the fracture toughness, but not the scratch toughness.

Figure 6a,b demonstrate that Cu doping increases both L

c1 and the difference between L

c2- L

c1 as well as CPRS values. The film with a Cu content of 10.5 at.% displayed optimal toughness among all five Cu-DLC films due to its maximal values of L

c1, L

c2- L

c1, and CPRS. As shown in

Figure 6b, there is a positive correlation between CPRS value and Cu doping content initially; however, this relationship becomes inverse when the doping content reaches 10.5 at%. In

Figure 6c, we observe few cracks or peeling on the scratch trace of the Cu-DLC film containing 10.5 at.% copper during testing indicating excellent toughness properties for this particular composition.

The optimal toughness of Cu-DLC using CPRs value was consistent with that from the results of morphology observation. Consequently, the scratch toughness may be determined through jointly analyzing the value of CPRS and scratch morphology. As for the drawback of impact test, Yu et al. [

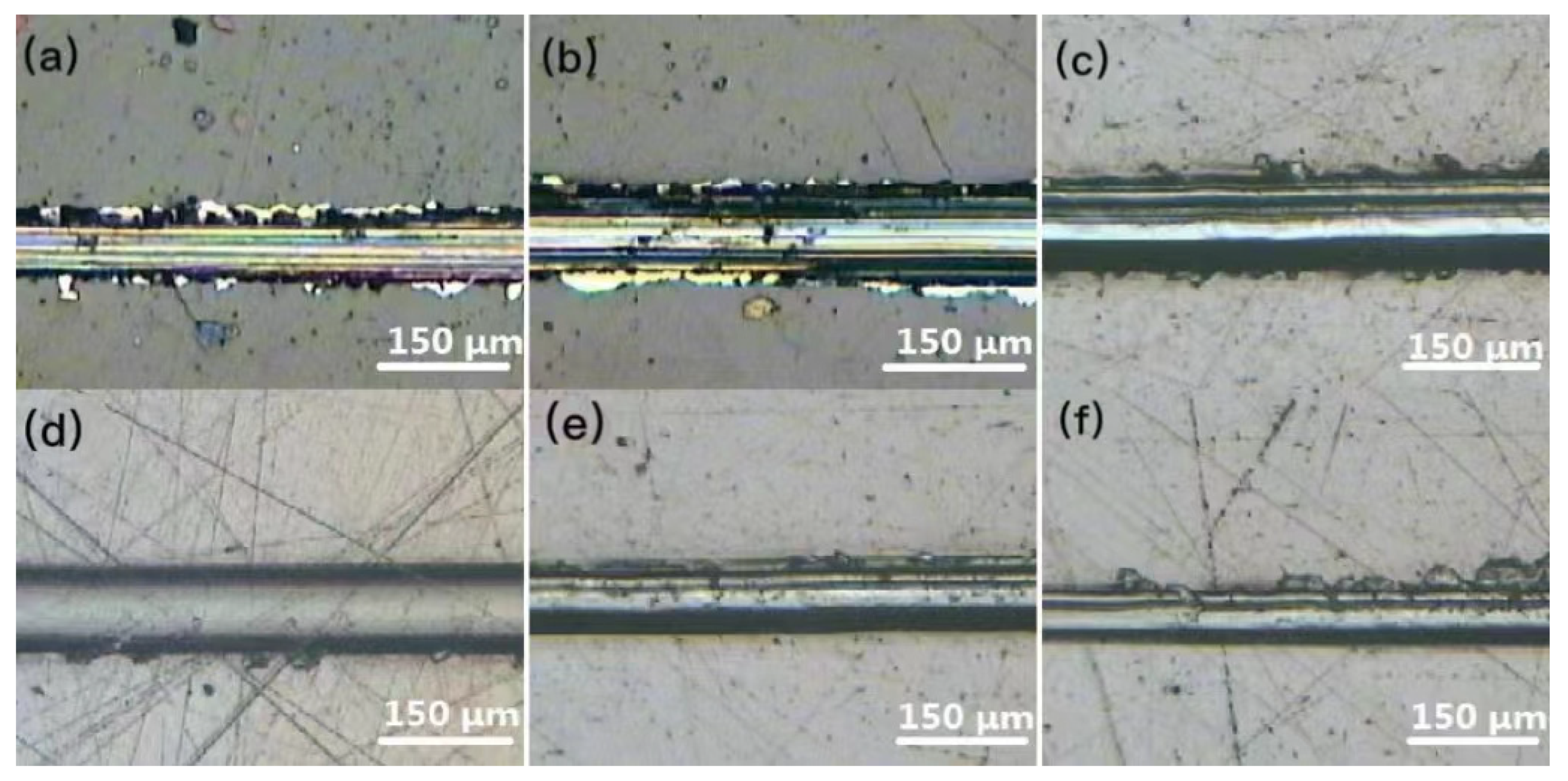

63] evaluated the scratch toughness of DLC films with six Ag contents in a comparative observation of the scratch morphologies in scratch test.

Figure 7 displays optical micrographs of the failure regions of DLC films with six Ag contents in scratch test. The films with different Ag doping contents exhibit different toughness behaviors.

Figure 7 shows optical micrographs of the failure regions of DLC films with six Ag contents in scratch test. The films with different Ag doping contents exhibit different toughness behaviors.

Figure 7a,b,f indicate that DLC films doped with low content or excessive content have poor toughness. When a low load is applied, brittle crack may initiate due to the inability of these films to resist the crack initiation.

Figure 7c,d,e infer that the films exhibit better toughness. As is shown in

Figure 7c, the discrepancy in the deformation degree between the film and substrate results in the failure under a high load

As compared with

Figure 7e, DLC film doped with 15.2% Ag in

Figure 7d presents better properties. The scratch trace is smoother, and no apparent cracks can be observed. A close observation reveals that DLC film doped with 15.2% Ag has a superior scratch toughness in vivid, whereas the impact toughness of two DLC films doped with 24.6% Ag and 15.2% Ag could not be distinguished due to similar morphologies in the impact test.

From the above data, the use of impact test or scratch test alone can only characterize the toughness of the film under certain service conditions. A complementary combination of impact toughness and scratch toughness may become an applicable characterization method of the film toughness. The impact toughness is derived from comparing of the impact morphologies, and the scratch toughness from CPRs value and the morphologies.

4. Toughening mechanism

The failure processes outlined in the toughness characterization above suggest that fracture initiation and propagation are the root causes of film failures. In the final section, we will present five toughening mechanisms of DLC films doped with non-carbide metal in the form of illustrations. A combination of the two processes of film manufacturing and toughness test serves as an illustration of the toughening mechanisms.

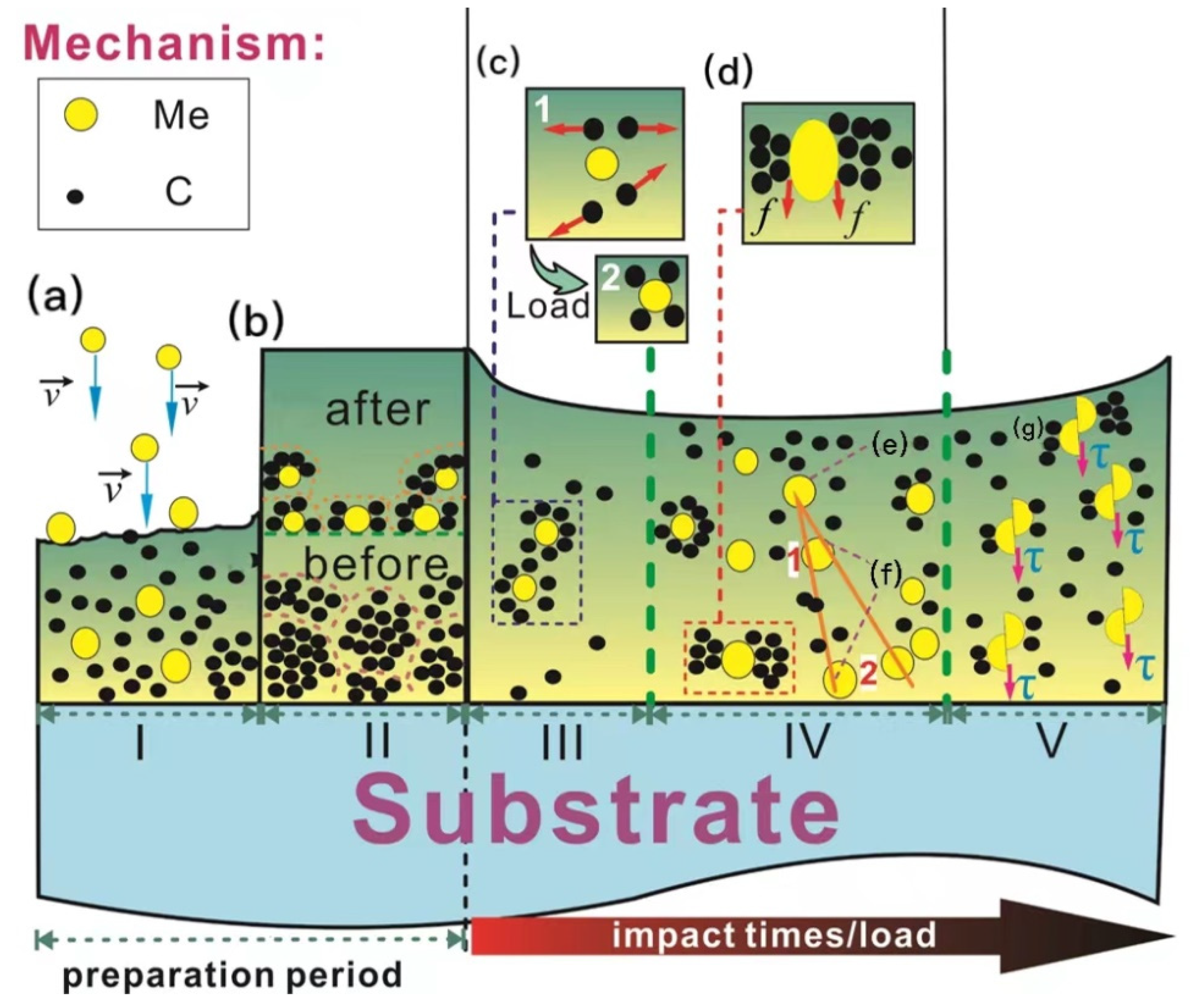

Figure 8 presents five toughening mechanisms of DLC film doped with non-carbide metal. The toughening mechanisms are illustrated in a combination of two processes of film fabrication and toughness test. In

Figure 8, the black dotted line means the toughening mechanism, and the five gradual patterns correspond to the five mechanisms (I-V) accordingly. Seven influential factors are denoted in red letters (a-g). The positive direction of the horizontal axis indicates a duration from the film fabrication to the toughness characterization test.

Mechanism I.Figure 8a shows the film-forming particles bombardment during film deposition. Compressive stress may be formed inside the film due to the bombardment. The particles with suitable energy may reduce the internal stress to inhibit crack initiation [

64].

Mechanism II. Figure 8b displays two statuses of film formation before and after the doping. Prior to the doping, “atomic clusters” in the amorphous carbon matrix have large particle sizes and few boundaries. The metal particles doped may disturb the clusters’ boundaries, and the carbon atoms tend to distribute around the metal particles. This results in formation of some new “atomic clusters”, having a much smaller particle size than that of the original “atomic clusters”. There are two aspects here: (i) reduced stress concentration, owing to the particle size decrease which is favorable to inhibit crack initiation [

65,

66,

67]. (ii) ductile doped metal particles slip through grain boundaries to inhibit crack propagation, in that the number of boundaries of the new “atomic clusters” is far more than that of the original carbon “atomic clusters” [

68,

69,

70].

Mechanism III.Figure 8(c1) indicates that plastic deformation does not occur before loading, and there is repulsive interaction between carbon atoms. After applying the load (

Figure 8(c2)), carbon atoms are distributed around the metal particles, the movement of carbon atoms becomes slow due to the weakened repulsive interaction. As a result, a decline in the degree of accumulation of dislocations at the defects may partly inhibit crack initiation.

Mechanism IV. Figure 8d–f exhibits three change patterns due to the metal doping. The pressure comes from the pressure needle or pressure ball, and the doped metal particle may have an important “ligament” role to inhibit crack initiation and propagation due to its ductility nature. (i) Stress accumulation may reduce by plastic deformation. There is friction (f) at the interface between different particles during loading, and the metal particles may undergo a plastic deformation (the yellow circular metal particle deforms into oval one, as shown in

Figure 8d). Stress accumulation is reduced because doping metal particles absorb energy during plastic deformation, and the stress field inside the film is relieved accordingly. (ii) The strain field is relaxed at the crack tip (

Figure 8e). When the orange crack tip encounters the metal particles, the crack tip propagation stops since the metal particles absorb the energy required for crack tip propagation. (iii) Bridging crack and yielding of the ductile phase act as “ligaments” (

Figure 8f). In

Figure 8(f1), two sides of a crack encounter the same metal particle, the metal particles bridge the crack to inhibit the crack propagation. In another case, two sides of the crack encounter different metal particles (

Figure 8(f2)), the metal particles may absorb the energy of crack propagation yielding deformation to inhibit the crack propagation.

During crack propagation, the crack tip may encounter either “atomic clusters” or the boundaries of “atomic clusters”, and the crack tips are more likely to propagate into the boundaries. An excessive amount of doping metals may lead to a leap of the boundary. The corresponding rise of probability and space of crack propagation may induce a drop in the crack resistance. As a result, only appropriate amount of the doped metal can improve the film toughness with efficiency.

Mechanism V.Figure 8g shows that the cracks begin to extend due to subsequent energy accumulation or pressure rise. When a crack encounters a soft metal particle with relatively low shear strength, the stress field inside the film may relieve by shearing the metal particle [

71,

72,

73,

74,

75]. It is worth noting that an excessive doping of soft metals may be adverse to the toughness due to an obvious drop in hardness.

5. Conclusion

The inherent weak toughness of DLC film restricts its industrial applicability. There is no unified toughness characterization method due to the low thickness of the film and the erroneous parameters of the current methods. Doping of non-carbide metal is introduced to improve the film toughness and is evaluated during toughness characterization. This allows us to propose the toughness characterization method and toughness mechanism.

The toughening may result from synthetic effect of the five mechanisms. It is tricky to see that, Mechanisms I and III imply that the toughening is simply proportional to the content of the metal nanoparticles. Mechanisms II, IV and V infer that the toughening may be inversely proportional to the doping content, in case that the content exceeds an inflection point. In accordance with our experimental results, Mechanisms II, IV and V are thus regarded as primary driving forces for toughening.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, X.Y., Y. W., and G.C.; validation, Y.W.; writing-review and editing, G.H., J. Y., and R.B.; visualization, X.Y.; funding acquisition, X.Y; supervision, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 51071143).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Cheng, F.; Wu, F.; Liu, L.; Yang, S.; Ji, W. Investigation on cavitation erosion of diamond-like carbon films with heterogeneous multilayer structure. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 405, 126682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalibón, E.L.; Escalada, L.; Simison, S.; Forsich, C.; Heim, D.; Brühl, S.P. Mechanical and corrosion behavior of thick and soft DLC coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 312, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemek, J.; Jiricek, P.; Houdkova, J.; Ledinsky, M.; Jelinek, M.; Kocourek, T. On the Origin of Reduced Cytotoxicity of Germanium-Doped Diamond-Like Carbon: Role of Top Surface Composition and Bonding. Nanomaterials, 2021; 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zia, A.W.; Zhou, Z.; Shum, P.W.; Li, K.Y. Development of diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings with alternate soft and hard multilayer architecture for enhancing wear performance at high contact stress. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 320, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nery, R.; Bonelli, R.S.; Camargo, S.S. Evaluation of corrosion resistance of diamond-like carbon films deposited onto AISI 4340 steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2010, 45, 5472–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernoulli, D.; Wyss, A.; Raghavan, R.; Thorwarth, K.; Hauert, R.; Spolenak, R. Contact damage of hard and brittle thin films on ductile metallic substrates: an analysis of diamond-like carbon on titanium substrates. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 2779–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auciello, O.; Aslam, D.M. Review on advances in microcrystalline, nanocrystalline and ultrananocrystalline diamond films-based micro/nano-electromechanical systems technologies. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 7171–7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.S.; Patel, S.K.; Fernandes, F. Performance of Al2O3/TiC mixed ceramic inserts coated with TiAlSiN, WC/C and DLC thin solid films during hard turning of AISI 52100 steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 3380–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Lin, S.; Gao, D.; Shi, Q.; Wei, C.; Dai, M.; Su, Y.; Xu, W.; Tang, P.; Li, H. Modulation of Si on microstructure and tribo-mechanical properties of hydrogen-free DLC films prepared by magnetron sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 509, 145381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, R.A.; Chen, P.; Schall, J.D.; Harrison, J.A.; Jeng, Y.; Carpick, R.W. Influence of chemical bonding on the variability of diamond-like carbon nanoscale adhesion. Carbon 2018, 128, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.J.; Zhang, T.F.; Son, M.J.; Kim, K.H. Synthesis and electrochemical properties of Ti-doped DLC films by a hybrid PVD/PECVD process. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 433, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzakis, E. Fatigue endurance assessment of DLC coatings on high-speed steels at ambient and elevated temperatures by repetitive impact tests. Coatings 2020, 10, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, A.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Wu, Z. The friction and wear properties of metal-doped DLC films under current-carrying condition. Tribol. Trans. 2019, 62, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, E.; Lanzutti, A.; Nakamura, M.; Zanocco, M.; Zhu, W.; Pezzotti, G.; Andreatta, F. Corrosion and scratch resistance of DLC coatings applied on chromium molybdenum steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 378, 124944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhuge, Z.; Zhao, S.; Zou, Y.; Tong, K.; Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Liang, Z.; Li, B.; Jin, T.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Z. Effects of Diamond on Microstructure, Fracture Toughness, and Tribological Properties of TiO2-Diamond Composites. Nanomaterials, 2022; 12, 3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, E.; Pardo, A.; Suter, T.; Mischler, S.; Schmutz, P.; Hauert, R. A methodology for characterizing the electrochemical stability of DLC coated interlayers and interfaces. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 375, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Hao, J. Microstructure, mechanical and tribological characterization of CrN/DLC/Cr-DLC multilayer coating with improved adhesive wear resistance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 439, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, G.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S. Diamond-like carbon film with gradient germanium-doped buffer layer by pulsed laser deposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 337, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Huang, J.; He, X.; Wang, T.; He, Z.; Du, K.; Diao, X. Preparation and characterization of high quality diamond like carbon films on Si microspheres. Mater. Lett. 2018, 220, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, U.; Falub, C.V.; Thorwarth, G.; Voisard, C.; Hauert, R. Diamond-like carbon coatings on a CoCrMo implant alloy: A detailed XPS analysis of the chemical states at the interface. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 1150–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, D.; Fu, Y.; Du, H. Toughness measurement of thin films: a critical review. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 198, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X. Toughness evaluation of hard coatings and thin films. Thin Solid Films 2012, 520, 2375–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Qiang, L.; Zhang, B.; Ling, X.; Yang, T.; Zhang, J. Mechanical and tribological properties of Ti-DLC films with different Ti content by magnetron sputtering technique. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 5025–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Kong, C.; Li, X.; Guo, P.; Wang, Z.; Wang, A. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti/Al co-doped DLC films: Dependence on sputtering current, source gas, and substrate bias. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 410, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicek, H.; Keles, A.; Totik, Y.; Efeoglu, I. Adhesion and multipass scratch characterization of Ti: Ta-DLC composite coatings. Diamond Relat. Mater. 2018, 83, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Qi, F.; Ouyang, X.; Zhao, N.; Zhou, Y.; Li, B.; Luo, W.; Liao, B.; Luo, J. Effect of Ti transition layer thickness on the structure, mechanical and adhesion properties of Ti-DLC coatings on aluminum alloys. Materials 2018, 11, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, G.A.; Roy, S.S.; Papakonstantinou, P.; McLaughlin, J.A. Structural investigation and gas barrier performance of diamond-like carbon based films on polymer substrates. Carbon 2005, 43, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Ootani, Y.; Bai, S.; Higuchi, Y.; Ozawa, N.; Adachi, K.; Martin, J.M.; Kubo, M. Tight-binding quantum chemical molecular dynamics study on the friction and wear processes of diamond-like carbon coatings: Effect of tensile stress. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 34396–34404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Li, B.; Ling, X.; Zhang, J. Superlubricity of hydrogenated carbon films in a nitrogen gas environment: adsorption and electronic interactions at the sliding interface. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 3025–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manimunda, P.; Al-Azizi, A.; Kim, S.H.; Chromik, R.R. Shear-induced structural changes and origin of ultralow friction of hydrogenated diamond-like carbon (DLC) in dry environment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 16704–16714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacı, H.; Yetim, A.F.; Baran, Ö.; Çelik, A. Tribological behavior of DLC films and duplex ceramic coatings under different sliding conditions. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 7151–7158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liza, S.; Hieda, J.; Akasaka, H.; Ohtake, N.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Nagai, A.; Hanawa, T. Deposition of boron doped DLC films on TiNb and characterization of their mechanical properties and blood compatibility. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2017, 18, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, X.; Yu, H.; Zhu, X.; Xie, Y. Fabrication, characterization and optical properties of TiO2 nanotube arrays on boron-doped diamond film through liquid phase deposition. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2014, 30, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trava-Airoldi, V.J.; Bonetti, L.F.; Capote, G.; Santos, L.V.; Corat, E.J. A comparison of DLC film properties obtained by rf PACVD, IBAD, and enhanced pulsed-DC PACVD. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 202, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.W.; Yu, X.; Hua, M.; Wang, C.B. Influence of copper content and nanograin size on toughness of copper containing diamond-like carbon films. Mater. Res. Innovations 2013, 17, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Písařík, P.; Jelínek, M.; Remsa, J.; Mikšovský, J.; Zemek, J.; Jurek, K.; Kubinová, Š.; Lukeš, J.; Šepitka, J. Antibacterial, mechanical and surface properties of Ag-DLC films prepared by dual PLD for medical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C, 2017; 77, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xie, T.; Qian, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X. Mechanical properties and biocompatibility of Ti-doped diamond-like carbon films. ACS omega 2020, 5, 22772–22777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovydaitis, V.; Marcinauskas, L.; Ayala, P.; Gnecco, E.; Chimborazo, J.; Zhairabany, H.; Zabels, R. The influence of Cr and Ni doping on the microstructure of oxygen containing diamond-like carbon films. Vacuum 2021, 191, 110351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Hu, T.; Wang, Q.; Shao, W.; Rao, L.; Xing, X.; Yang, Q. Role of TiC nanocrystalline and interface of TiC and amorphous carbon on corrosion mechanism of titanium doped diamond-like carbon films: Exploration by experimental and first principle calculation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 542, 148740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, J.C. Impression test—a review. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2013, 74, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ning, Z.W.; Hua, M.; Wang, C.B. Influence of silver incorporation on toughness improvement of diamond-like carbon film prepared by ion beam assisted deposition. J Adhes 2013, 89, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, W.; Dong, Y.; Ma, M.; Liu, Y.; Tian, S.; Xiao, Y.; Jia, Y. Electrodeposition and microstructure of Ni and B co-doped diamond-like carbon (Ni/B-DLC) films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 405, 126713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, P.P.; Feng, Q.G.; Lan, Q.H.; Ma, D.L.; Wang, H.Y.; Jiang, X.; Leng, Y.X. Migration and agglomeration behaviors of Ag nanocrystals in the Ag-doped diamond-like carbon film during its long-time service. Carbon 2023, 201, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidparvar, A.A.; Mosavi, M.A.; Ramezanzadeh, B. Nickel-aluminium bronze (NiBRAl) casting alloy tribological/corrosion resistance properties improvement via deposition of a Cu-doped diamond-like carbon (DLC) thin film; optimization of sputtering magnetron process conditions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 296, 127279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Hao, J. Microstructure, mechanical and tribological characterization of CrN/DLC/Cr-DLC multilayer coating with improved adhesive wear resistance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 439, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Shao, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S.; Xing, X.; Yang, Q. Mechanical and tribological behaviors of Ti-DLC films deposited on 304 stainless steel: Exploration with Ti doping from micro to macro. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2020, 107, 107870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, L.; Maity, S.R.; Kumar, S. Comprehensive structural, nanomechanical and tribological evaluation of silver doped DLC thin film coating with chromium interlayer (Ag-DLC/Cr) for biomedical application. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 22805–22818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goehring, L.; Clegg, W.J.; Routh, A.F. Plasticity and fracture in drying colloidal films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 24301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodnik, N.R.; Brach, S.; Long, C.M.; Ravichandran, G.; Bourdin, B.; Faber, K.T.; Bhattacharya, K. Fracture Diodes: Directional asymmetry of fracture toughness. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 25503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yan, F. Scratch-induced deformation and damage behavior of doped diamond-like carbon films under progressive normal load of Vickers indenter. Thin Solid Films 2022, 756, 139351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegunde, O.O.; Makha, M.; Machkih, K.; Larhlimi, H.; Ghailane, A.; Samih, Y.; Alami, J. Structural, mechanical and corrosion resistance of phosphorus-doped TiAlN thin film. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 19107–19130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, J.; Huang, W.; Wang, L.; He, H.; Liu, C. The investigation of the structures and tribological properties of F-DLC coatings deposited on Ti-6Al-4V alloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 316, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, W.; Dong, Y.; Ma, M.; Liu, Y.; Tian, S.; Xiao, Y.; Jia, Y. Electrodeposition and microstructure of Ni and B co-doped diamond-like carbon (Ni/B-DLC) films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 405, 126713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, K.; Gou, S. Structural, mechanical and tribological behavior of different DLC films deposited on plasma nitrided CF170 steel. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2021, 116, 108400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. Structure characterization and antibacterial properties of Ag-DLC films fabricated by dual-targets HiPIMS. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 410, 126967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolawole, F.O.; Varela, L.B.; Kolawole, S.K.; Ramirez, M.A.; Tschiptschin, A.P. Deposition and characterization of tungsten oxide (WO3) nanoparticles incorporated diamond-like carbon coatings using pulsed-DC PECVD. Mater. Lett. 2021, 282, 128645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, P.P.; Ma, D.L.; Gong, Y.L.; Luo, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Weng, Y.J.; Leng, Y.X. Influence of Ag doping on the microstructure, mechanical properties, and adhesion stability of diamond-like carbon films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 405, 126542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.S.; Zhou, Z.; Xie, Z.; Munroe, P. Designing multilayer diamond like carbon coatings for improved mechanical properties. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 65, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabarczyk, J.; Gaj, J.; Pazik, B.; Kaczorowski, W.; Januszewicz, B. Tribocorrosion behavior of Ti6Al4V alloy after thermo-chemical treatment and DLC deposition for biomedical applications. Tribol. Int. 2021, 153, 106560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugela, A.; Chang, C.H.; Peterson, D.W. Deep learning based characterization of nanoindentation induced acoustic events. Mater. Sci. Eng. C a 2021, 800, 140273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, T.; Yan, B.; Qi, H.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, D.; Tian, Y.; Jaffery, S.H.I. Synergistic friction-reducing and anti-wear behaviors of DLC on NCD films via in-situ synthesis by fs laser ablation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 409, 126947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claver, A.; Jiménez-Piqué, E.; Palacio, J.F.; Almandoz, E.; Fernández De Ara, J.; Fernández, I.; Santiago, J.A.; Barba, E.; García, J.A. Comparative study of tribomechanical properties of HiPIMS with positive pulses DLC coatings on different tools steels. Coatings 2020, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Shao, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S.; Xing, X.; Yang, Q. Mechanical and tribological behaviors of Ti-DLC films deposited on 304 stainless steel: Exploration with Ti doping from micro to macro. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2020, 107, 107870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Guo, P.; Zuo, X.; Sun, L.; Li, X.; Lee, K.; Wang, A. Understanding the effect of Al/Ti ratio on the tribocorrosion performance of Al/Ti co-doped diamond-like carbon films for marine applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 402, 126347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, M.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, G. Effect of dopants (F, Si) material on the structure and properties of hydrogenated DLC film by plane cathode PECVD. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2020, 110, 108102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ţălu, Ş.; Abdolghaderi, S.; Pinto, E.P.; Matos, R.S.; Salerno, M. Advanced fractal analysis of nanoscale topography of Ag/DLC composite synthesized by RF-PECVD. Surf. Eng. 2020, 36, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.S.; Majumder, H.; Khan, A.; Patel, S.K. Applicability of DLC and WC/C low friction coatings on Al2O3/TiCN mixed ceramic cutting tools for dry machining of hardened 52100 steel. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 11889–11897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, L.; Maity, S.R.; Kumar, S. Comprehensive structural, nanomechanical and tribological evaluation of silver doped DLC thin film coating with chromium interlayer (Ag-DLC/Cr) for biomedical application. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 22805–22818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Zhang, F.; Fong, A.; Lai, K.M.; Shum, P.W.; Zhou, Z.F.; Gao, Z.F.; Fu, T. Effects of silver segregation on sputter deposited antibacterial silver-containing diamond-like carbon films. Thin Solid Films 2018, 650, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Cao, X.; Yin, P.; Ding, Q.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, G. Design of a novel superhydrophobic F&Si-DLC film on the internal surface of 304SS pipes. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 123, 108852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, R.; Jonayat, A.; Van Duin, A.C.; Biswas, M.M.; Hempstead, R. A reactive force field study on the interaction of lubricant with diamond-like carbon structures. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 27443–27451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, C.; Osman, E.; Chen, X.; Ma, T.; Hu, Y.; Luo, J.; Ali, E. Influence of tribofilm on superlubricity of highly-hydrogenated amorphous carbon films in inert gaseous environments. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2016, 59, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajita, S.; Righi, M.C. Insigths into the tribochemistry of silicon-doped carbon-based films by ab initio analysis of water–surface interactions. Tribol. Lett. 2016, 61, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, H. A shear localization mechanism for lubricity of amorphous carbon materials. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetter, J. 60 years of DLC coatings: historical highlights and technical review of cathodic arc processes to synthesize various DLC types, and their evolution for industrial applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 257, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).