Submitted:

15 November 2023

Posted:

15 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Samples

2.3. Treatments

2.3.1. Treatments with MJ an ABA Paste

2.3.2. Treatments with MJ and ABA Spray

2.4. Physicochemical Parameters

2.4.1. Juiciness

2.4.2. Moisture Content

2.4.3. Total Soluble Solids (TSS)

2.4.4. Acidity

Active Acidity (or Hydrogen Concentration pH)

Total Titratable Acidity (TTA)

2.4.5. Maturity index

2.5. Health-Related Quality

2.5.1. Determination of Carotenoids

Extraction

Total Carotenoid Content (TCC)

Individual Carotenoids by HPLC

2.5.2. Anthocyanins

Extraction

Total Anthocyanin Content (TAC)

2.6. Antioxidant Activity

2.7. Statistical Study

3. Results and Discussion

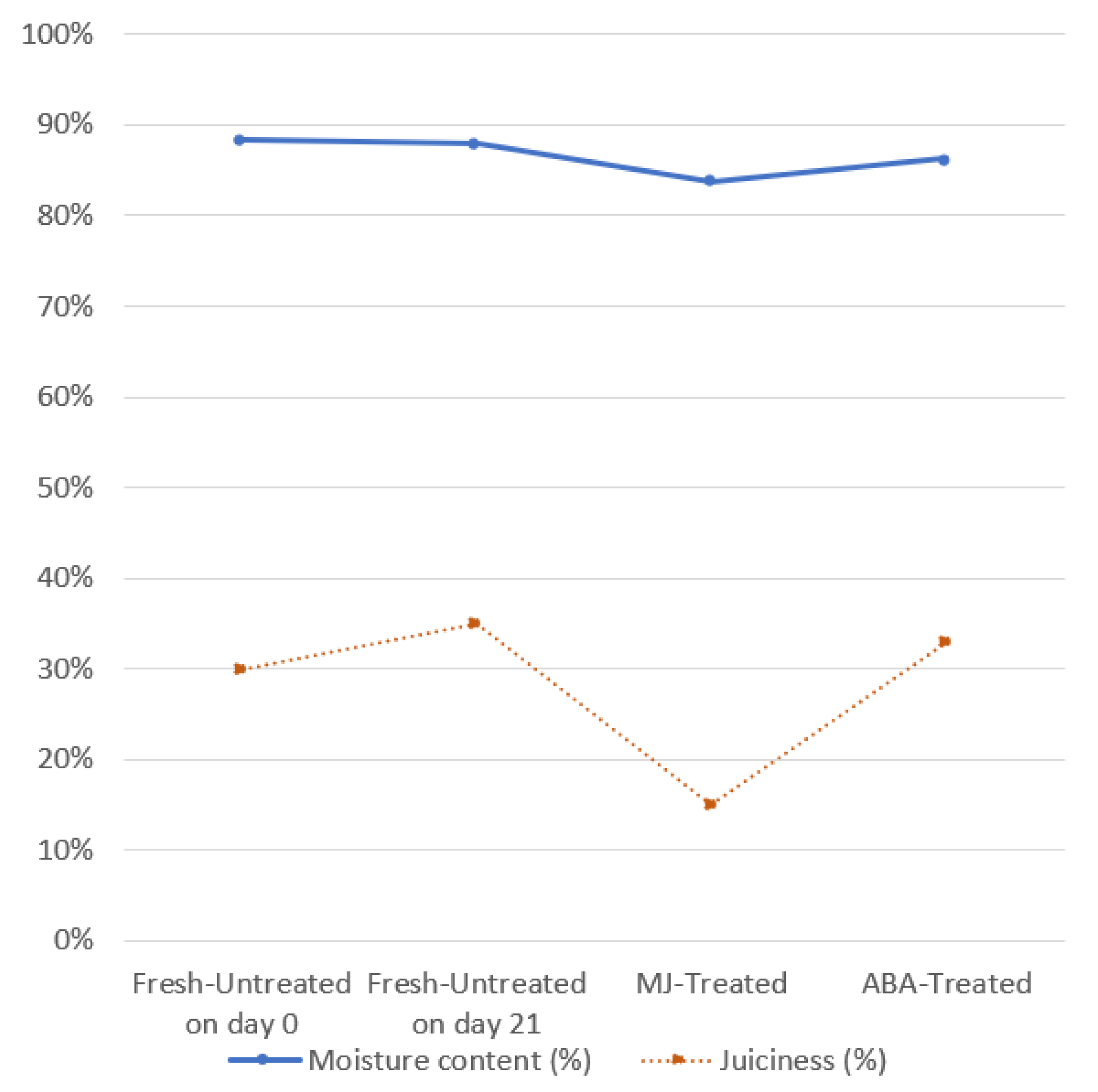

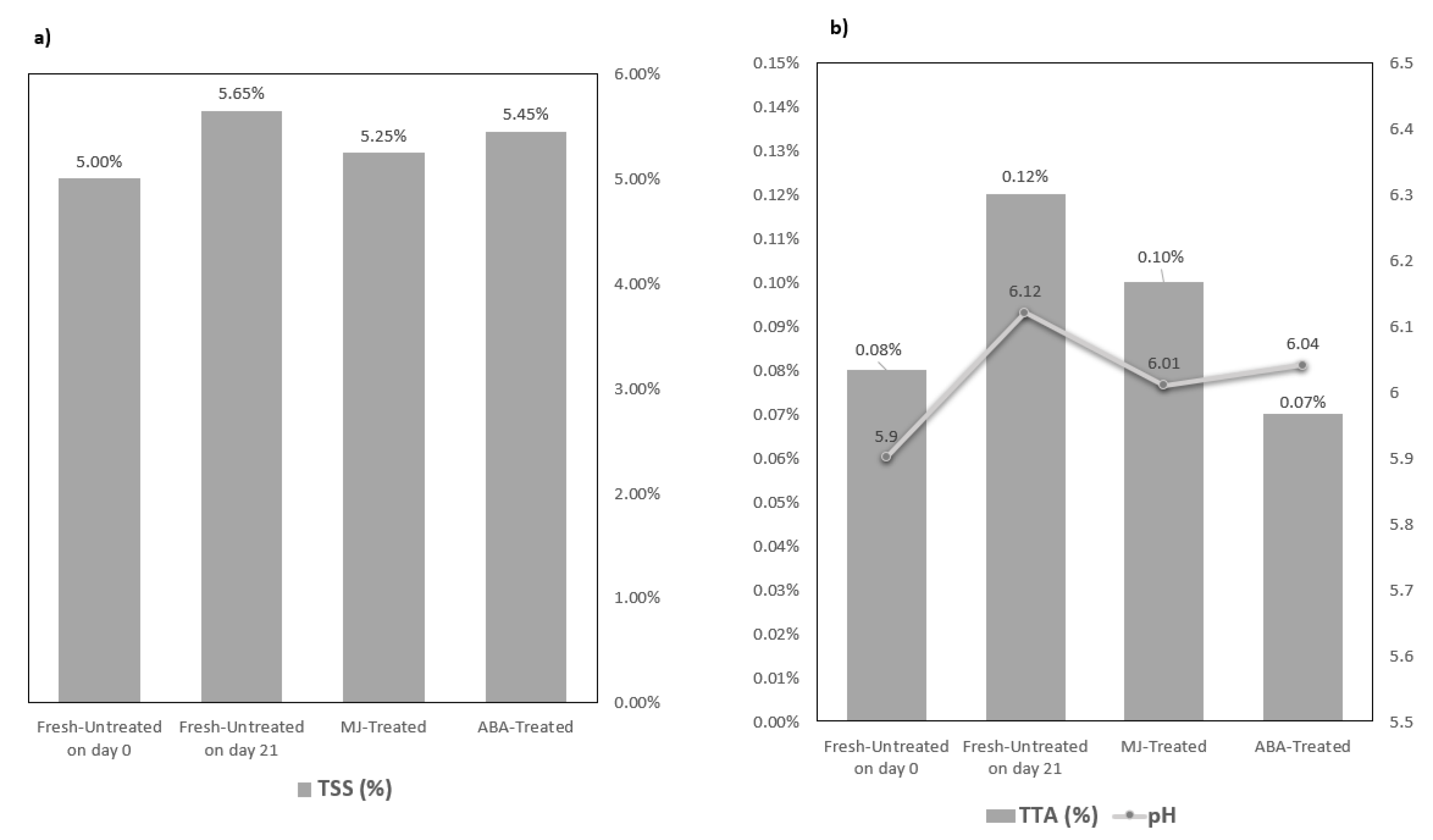

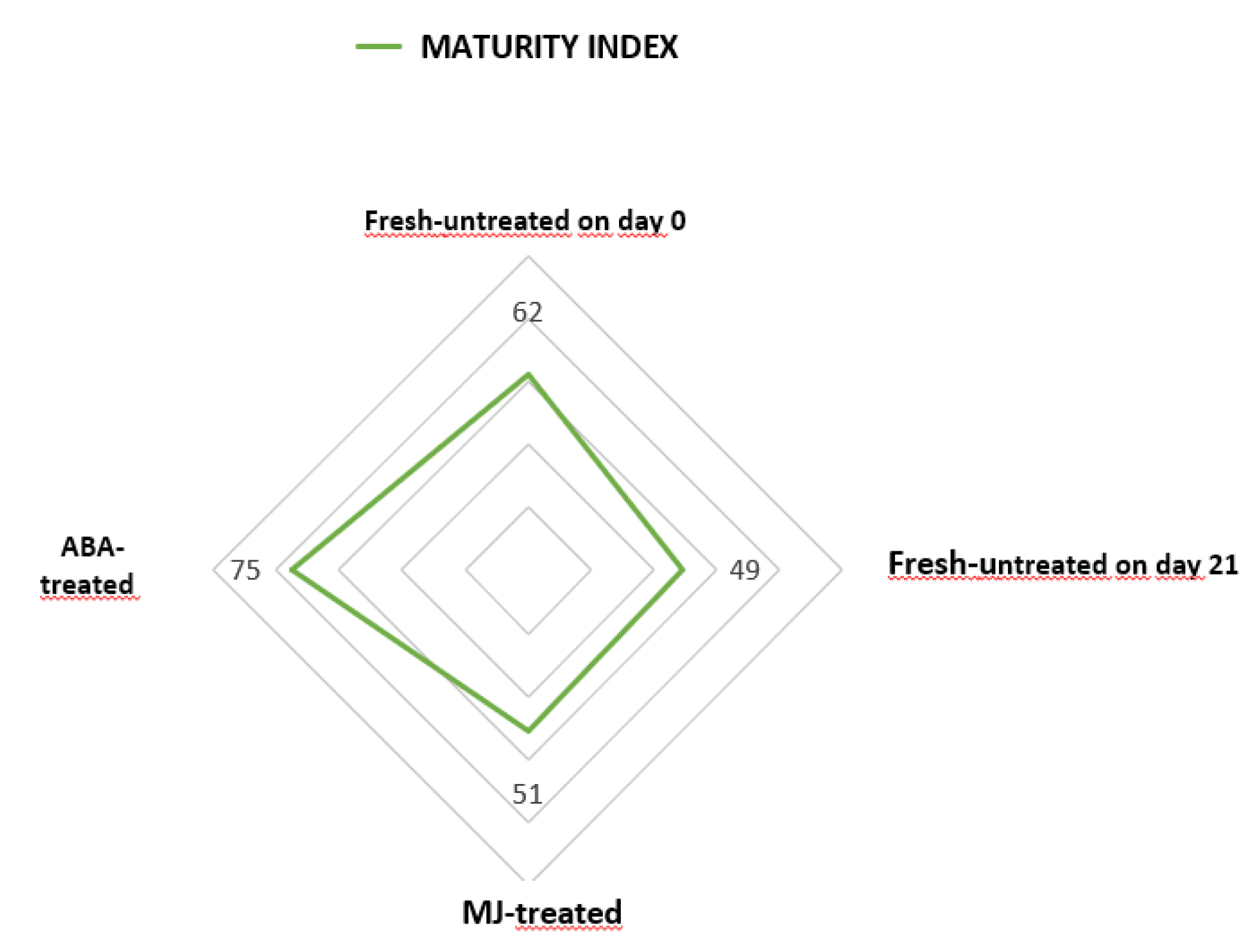

3.1. Physicochemical Quality

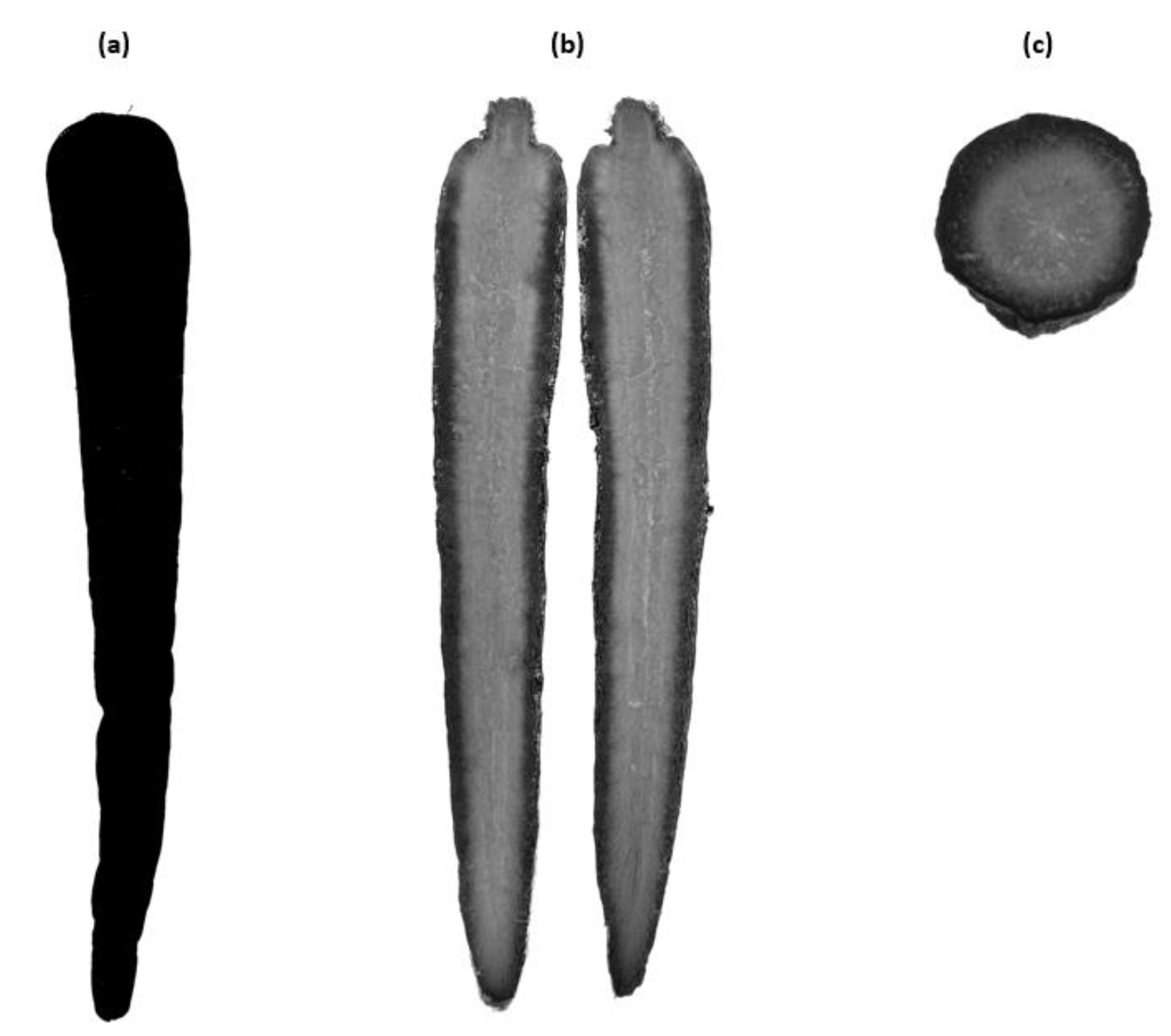

3.1.1. Visual Observation

3.1.2. Physicochemical parameters

3.2. Health-Related Quality

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alasalvar, C., Grigor, J.M., Zhang, D., Quantick, P.C., Shahidi, F., 2001. Comparison of volatiles, phenolics, sugars, antioxidants, vitamins, and sensory quality of different colored carrots varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49, 1410-1416.

- Al-Dairi, M., Pathare, P.B., Al-Yahayi, R., 2021. Chemical and nutritional quality changes of tomato during postharvest transportation and storage. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 20, 401-408. [CrossRef]

- Arscott, S.A., Simon, P.W., Tanumihardjo, S.A., 2010. Anthocyanins in purple-orange carrots (Daucus carota L.) do not influence the bioavailability of b-carotene in young women. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58, 2877-2881.

- Barba-Espín, G., Lütken, H., Glied, S., Crocoll, C., Joernsgaard, B., Müller, R., 2019. Anthocyanin elicitation for bio-sustainable colourant production in carrot. Acta Hortic. 1242, 87-92. [CrossRef]

- Barba-Espín, G., Martínez-Jiménez, C., Izquierdo-Martínez, A., Acosta-Motos, J.R., Hernández, J.A., Díaz-Vivancos, P., 2021. H2O2-elicitation of black carrot hairy roots induces a controlled oxidative burst leading to increased anthocyainin production. Plants 10, 2753-2768.

- Blanch, G.P., Gómez-Jiménez, M.C., Ruiz del Castillo, M.L., 2020. Exogenous salicylic acid improves phenolic content and antioxidant activity in table grapes. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 75, 177-183. [CrossRef]

- Blando, G., Marchello, S., Maiorano, G., Durante, M., Signore, A., Laus, M.N., Soccio, M., Mita, G., 2021. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity in anthocyanin-rich carrots: a comparison between the black carrot and the Apulian Landrace “Polignano” carrot. Plants 10, 564-579. [CrossRef]

- Berger, M., Kuchler, T., Maasen, A., Busch-Stockfisch, M., Steinhart, M., 2008. Correlation of carotene with sensory attributes in carrots under different storage conditions. Food Chem 106, 235-240. [CrossRef]

- Britton, G. 1998. Carotenoids, In: Dey P.M.; Harborne, J.B. (eds), Methods in plant biochemistry, vol 7. Terpenoids, Academic Press, New York, pp 473-518.

- Cisneros-Zevallos, L., Saltveit, M.E., Krochta, J.M., 1995. Mechanism of surface white discoloration of peeled (minimally processed) carrots during storage. J. Food Sci. 60, 320–323. [CrossRef]

- De Pascual-Teresa, S. and Sánchez-Ballesta, M.T., 2008. Anthocyanins: from plant to health. Phytochem. Rev. 7, 281-199.

- Flores, G., Blanch, G.P., Ruiz del Castillo, M.L., 2018. Abscisic acid treated olive seeds as a natural source of bioactive compounds. LWT-Food Technol. & Biol. 90, 556-561. [CrossRef]

- Flores, G. and Ruiz del Castillo, M.L., 2016. Accumulation of anthocyanins and flavonols in black currant (Ribes nigrum L.) by pre-harvest methyl jasmonate treatments. J. Sci. Food Agric. 96, 4026-4031.

- Galani, J.H., Pater, J.S., Patel, N.J., Talati, J.G., 2017. Storage of fruits and vegetables in refrigerator increases their phenolic acids but decreases the total phenolics, anthocyanins and vitamin C with subsequent loss of their antioxidant capacity. Antioxidants 6, 59-58. [CrossRef]

- Giusti, M. and Wrolstad, R.E., 2001. Characterization and measurement of anthocyanins by UV visible spectroscopy. In: Giusti, M.M.; Wrolstad, R.E. (eds). Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. Wiley, New York, pp F1.2.1–F1.2.13. [CrossRef]

- Hammaz, F., Charles, F., Kopec, R.E., Halimi, Ch., Fgaier, S., Aarrouf, J., Urban, L., Borel, P., 2021. Temperature and storage time increase provitamin A carotenoid concentrations and bioaccessibility in post-harvest carrots. Food Chem. 338, 12004-12013. [CrossRef]

- Hashem, H.A., Sharaf, A.M., Amira, S.A., Ibrahim, G.E., 2014. Changes in physico-chemical quality and volatile compounds of orange-carrot juice blends during storage. Food Sci. Qual. Manag. 33, 21-35.

- Howard, I.A., Wong, A.D., Perry, A.K., Klein, B.P., 1999. Beta-carotene and ascorbic acid retention in fresh and processed vegetables. J. Food Sci. 64, 929-936.

- Imsic, M., Winkler, S., Tomkins, B., Jones, R., 2010. Effect of storage and cooking on beta-carotene isomers in carrots (Daucus carota L. cv Stefano). J. Agric. Food Chem. 58, 5109-5113.

- Lee, C.Y., 1986. Changes in ca rotenoid content of carrots during growth and post-harvest storage. Food Chem. 20, 285-293.

- Macura, R., Michalczyk, M., Fiutak, G., Maciejaszek, I., 2019. Effect of freeze-drying and air drying on the content of carotenoids and anthocyanins in stored purple carrot. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 18, 135-142.

- Moreno-Escamilla, J.O., Jiménez-Hernández, F.E., Alvarez-Parrilla, E., de la Rosa, L.A., del Rocío Martínez-Ruiz, N., González-Fernández, R., 2020. Effect of elicitation on polyphenol and carotenoid metabolism in butterhead lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. capitate). ACS Omega 5, 11535–11546. [CrossRef]

- Munhuewyi, K., 2012. Postharvest losses and changes in quality of vegetables from retail to consumer: a case study of tomato, cabbage and carrot. Master thesis, Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University.

- Opoku, A., Meda, V., Wahab, J., 2009. Effects of storage methods on quality characteristics of carrots grown under organic and conventional management. The Canadian Society of Bioengineering, CSBE/SCGAB 2009 Annual Conference, Paper No. CSBE09-702.

- Özen, G., Akbulut, M., Artik, N., 2011. Stability of black carrot anthocyanins in the Turkish delight (Lokum) during storage. J. Food Process Eng. 34, 1282-1297. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.B., Carvajal, S., Beretta, V., Bannoud, F., Fangio, M.F., Berli, F., Fontana, A., Salomón, M.V., González, R., Valerga, L., Altamirano, J.C., Yildiz, M., Iorizzo, M., Simon, P.W., Cavagnaro, P.F., 2023. Characterization of purple carrot germplasm for antioxidant capacity and root concentration of anthocyanins, phenolics, and carotenoids. Plants 12, 1796-1822. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz del Castillo, M.L., Flores, G., Blanch, G.P., 2010. Exogenous methyl jasmonate diminishes the formation of lipid-derived compounds in boiled potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 90, 2263-2267. [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K. and Keum, Y-S., 2018. Carotenoid extraction methods: A review of recent developments. Food Chem. 240, 90-103. [CrossRef]

- Senkumba, J., Kaaya, A., Atukwase, A., Wasukira, A., 2017. Effect of storage conditions on the processing quality of different potato varieties grown in Eastern Uganda. Expanding Utilization of Roots, Tubers and Bananas and Reducing Their Postharvest Losses. RTB Endure project, 1-22.

- Van der Berg, H., Faulks, R., Fernando Granado, H., Hirschberg, J., Olmedilla, B., Sandmann, G., Southon, S., Stahl, W., 2000. The potential for the improvement of carotenoid levels in foods and the likely systemic effects. J. Sci. Food Agric. 80, 880-912.

- Wrolstad, R.E., 2004. Anthocyanin pigments-bioactivity and coloring properties. J. Food Sci. 69, 419-421. [CrossRef]

- Yen, Y.H., Shin, C.H., Chang, C.H., 2008. Effect of adding ascorbic acid and glucose on the antioxidant properties during of dried carrots. Food Chem. 107, 265-272. [CrossRef]

- Zelenkova, E.N., Yegorova, Z.E., Shabunya, P.S., Fatykhava, S.A., 2015. HPLC analysis of carotenoids in particular carrot (Daucus carota L.) cultivars. UDC 4, 9-15.

| FRESH-UNTREATED | MJ TREATMENT | AA TREATMENT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On day 0 | On day 21 | Control | Treated | Control | Treated | ||

|

TCC (mg EβC g-1DW) |

1.41±0.03a | 3.79±0.05b | 1.59±0.02a | 1.61±0.03a | 2.06±0.04c | 2.15±0.03c | |

|

TAC (mg ECGg−1DW) |

2.23±0.05a | 2.18±0.04a | 0.43±0.02b | 0.37±0.01b | 0.26±0.01b | 0.30±0.02b | |

| FRESH-UNTREATED | MJ TREATMENT | ABA TREATMENT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On day 0 | On day 21 | |||

|

LUTEIN (mg EβCg−1DW) |

0.23±0.01a | 0.68±0.03b | 0.18±0.01a | 0.16±0.02a |

|

β-CAROTENE (mg EβCg−1DW) |

4.87±0.07a | 28.16±0.10b | 2.06±0.05c | 4.93±0.09a |

| ASSAY | FRESH-UNTREATED | MJ TREATMENT | AA TREATMENT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On day 0 | On day 21 | Control | Treated | Control | Treated | |

|

DPPH (mg TROLOX g−1DW) |

12.24±0.06a | 12.71±0.05a | 4.73±0.02b | 4.09±0.03b | 4.25±0.02b | 4.89±0.02b |

|

FRAP (mg TROLOX g-1DW) |

17.57±0.08a | 30.03±0.07a | 7.38±0.02b | 6.02±0.02b | 6.37±0.04b | 7.02±0.03b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).