Submitted:

13 November 2023

Posted:

14 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

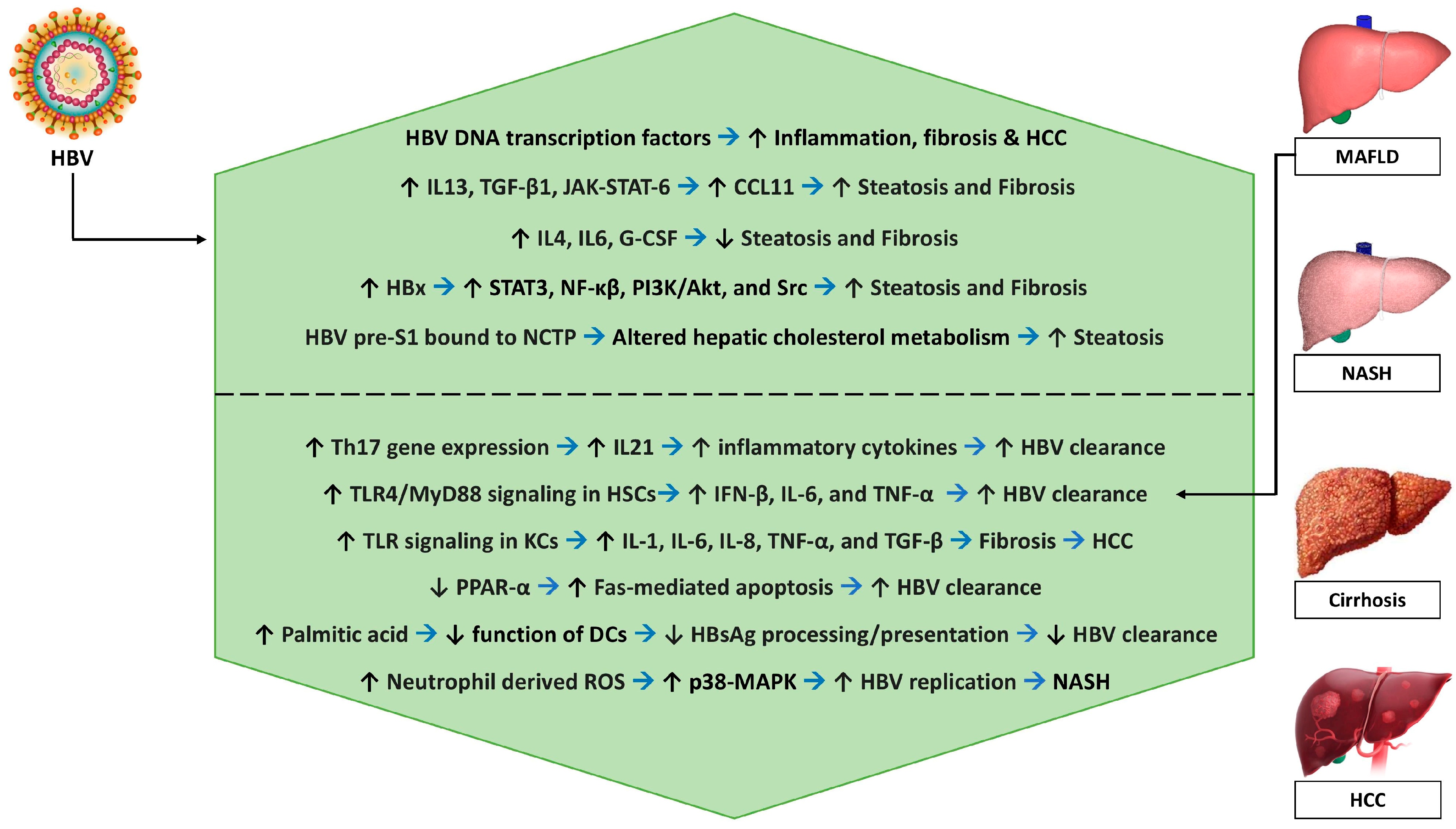

MAFLD and chronic HBV infection

Epidemiology

Effect of MAFLD on CHB infection and chronic liver disease progression:

Effects of CHB infection on the MAFLD and chronic liver disease progression

Complications

Management

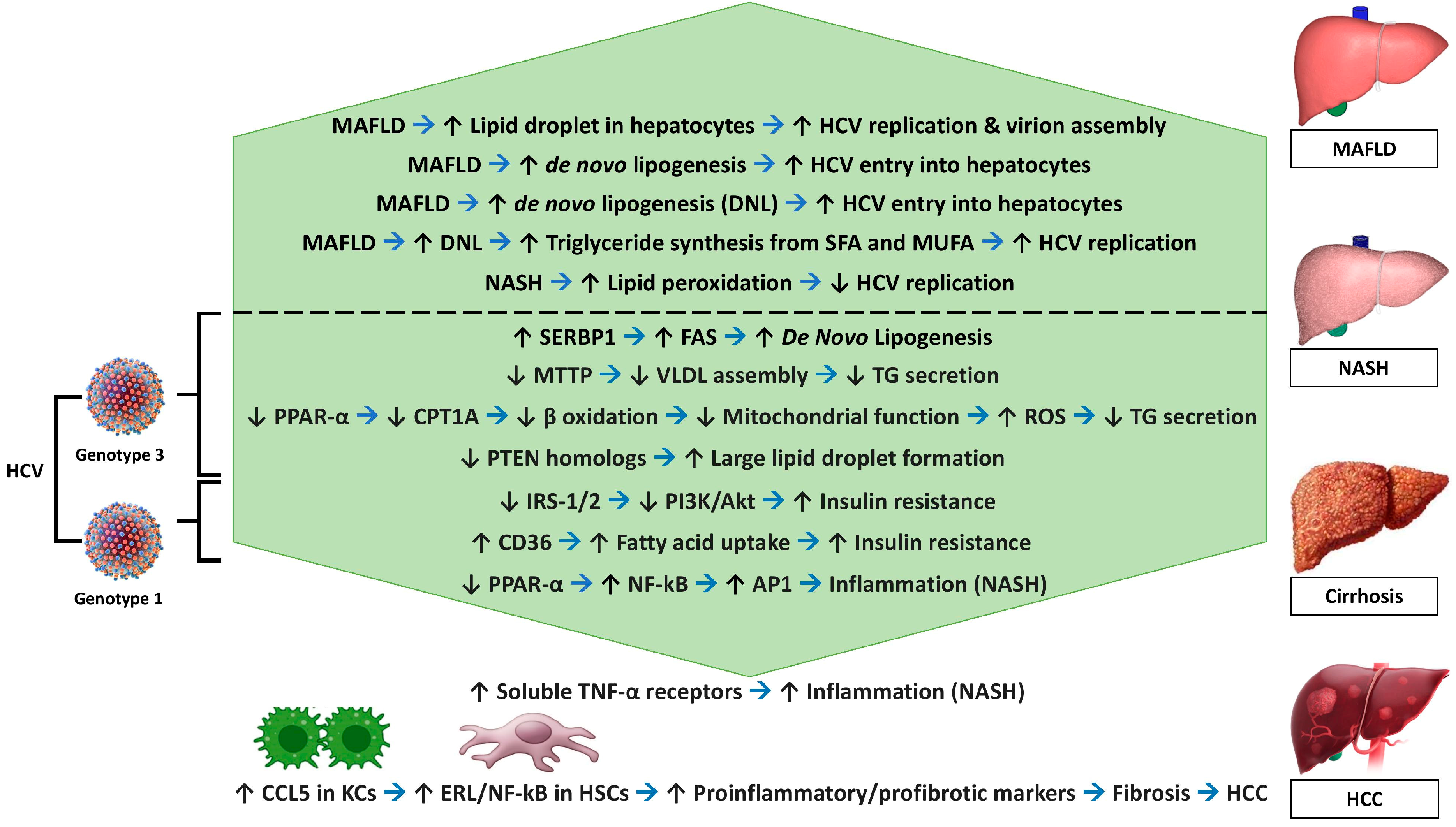

MAFLD and chronic HCV infection

Epidemiology

Disease characteristics

Effect of MAFLD on CHC infection and chronic liver disease progression:

Effect of CHC infection on the MAFLD and chronic liver disease progression:

Complications

Management.

Areas of uncertainty/emerging concepts

Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fouda S, Jeeyavudeen MS, Pappachan JM, Jayanthi V. Pathobiology of Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2023 Sep;52(3):405-416. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka N, Kimura T, Fujimori N, Nagaya T, Komatsu M, Tanaka E. Current status, problems, and perspectives of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease research. World J Gastroenterol. 2019 Jan 14;25(2):163-177. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslam M, Sanyal AJ, George J; International Consensus Panel. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2020 May;158(7):1999-2014.e1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane H, Gofton C, Sharma A, George J. MAFLD: an optimal framework for understanding liver cancer phenotypes. J Gastroenterol. 2023 Jul 20. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baclig MO, Reyes KG, Liles VR, Mapua CA, Dimamay MPS, Gopez-Cervantes J. Hepatic steatosis in chronic hepatitis B: a study of metabolic and genetic factors. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2018 Apr 5;9(2):13-19. [PubMed]

- Asselah T, Rubbia-Brandt L, Marcellin P, Negro F. Steatosis in chronic hepatitis C: why does it really matter? Gut. 2006 Jan;55(1):123-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi Z, Tacke F, Arrese M, Chander Sharma B, Mostafa I, Bugianesi E, Wai-Sun Wong V, Yilmaz Y, George J, Fan J, Vos MB. Global Perspectives on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2019 Jun;69(6):2672-2682. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado MV, Oliveira AG, Cortez-Pinto H. Hepatic steatosis in hepatitis B virus infected patients: meta-analysis of risk factors and comparison with hepatitis C infected patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Sep;26(9):1361-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng Q, Zou B, Wu Y, Yeo Y, Wu H, Stave CD, Cheung RC, Nguyen MH. Systematic review with meta-analysis: prevalence of hepatic steatosis, fibrosis and associated factors in chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Nov;54(9):1100-1109. Epub 2021 Sep 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang D, Chen C, Liu X, Huang C, Yan D, Zhang X, Zhou Y, Lin Y, Zhou Y, Guan Z, Ding C, Lan L, Zhu C, Wu J, Li L, Yang S. Concurrence and impact of hepatic steatosis on chronic hepatitis B patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2021 Dec;9(23):1718. PMCID: PMC8743703. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li HJ, Kang FB, Li BS, Yang XY, Zhang YG, Sun DX. Interleukin-21 inhibits HBV replication in vitro. Antivir Ther. 2015;20(6):583-90. Epub 2015 Mar 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiziltas S. Toll-like receptors in pathophysiology of liver diseases. World J Hepatol. 2016 Nov 18;8(32):1354-1369. PMCID: PMC5114472. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang RN, Pan Q, Zhang Z, Cao HX, Shen F, Fan JG. Saturated Fatty Acid inhibits viral replication in chronic hepatitis B virus infection with nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease by toll-like receptor 4-mediated innate immune response. Hepat Mon. 2015 May 23;15(5):e27909. PMCID: PMC4451278. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, Schwabe RF. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007 Nov;13(11):1324-32. Epub 2007 Oct 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares JB, Pimentel-Nunes P, Afonso L, Rolanda C, Lopes P, Roncon-Albuquerque R Jr, Gonçalves N, Boal-Carvalho I, Pardal F, Lopes S, Macedo G, Lara-Santos L, Henrique R, Moreira-Dias L, Gonçalves R, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Leite-Moreira AF. Increased hepatic expression of TLR2 and TLR4 in the hepatic inflammation-fibrosis-carcinoma sequence. Innate Immun. 2012 Oct;18(5):700-8. Epub 2012 Feb 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccinin E, Villani G, Moschetta A. Metabolic aspects in NAFLD, NASH and hepatocellular carcinoma: the role of PGC1 coactivators. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Mar;16(3):160-174. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang CY, Lu CW, Liu YL, Chiang CH, Lee LT, Huang KC. Relationship between chronic hepatitis B and metabolic syndrome: A structural equation modeling approach. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016 Feb;24(2):483-9. Epub 2015 Dec 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarčuška P, Janičko M, Kružliak P, Novák M, Veselíny E, Fedačko J, Senajová G, Dražilová S, Madarasová-Gecková A, Mareková M, Pella D, Siegfried L, Kristián P, Kolesárová E; HepaMeta Study Group. Hepatitis B virus infection in patients with metabolic syndrome: a complicated relationship. Results of a population based study. Eur J Intern Med. 2014 Mar;25(3):286-91. Epub 2014 Jan 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon S, Jung J, Kim T, Park S, Chwae YJ, Shin HJ, Kim K. Adiponectin, a downstream target gene of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, controls hepatitis B virus replication. Virology. 2011 Jan 20;409(2):290-8. Epub 2010 Nov 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinet J, Dufeu-Duchesne T, Bruder Costa J, Larrat S, Marlu A, Leroy V, Plumas J, Aspord C. Altered functions of plasmacytoid dendritic cells and reduced cytolytic activity of natural killer cells in patients with chronic HBV infection. Gastroenterology. 2012 Dec;143(6):1586-1596.e8. Epub 2012 Sep 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang WW, Su IJ, Chang WT, Huang W, Lei HY. Suppression of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in human hepatoma cell: the antiviral role of nitric oxide. J Viral Hepat. 2008 Jul;15(7):490-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Cabrera M, Letovsky J, Hu KQ, Siddiqui A. Multiple liver-specific factors bind to the hepatitis B virus core/pregenomic promoter: trans-activation and repression by CCAAT/enhancer binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Jul;87(13):5069-73. PMCID: PMC54263. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim BK, Lim SO, Park YG. Requirement of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein for hepatitis B virus replication. Hepatology. 2008 Aug;48(2):361-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raney AK, Zhang P, McLachlan A. Regulation of transcription from the hepatitis B virus large surface antigen promoter by hepatocyte nuclear factor 3. J Virol. 1995 Jun;69(6):3265-72. PMCID: PMC189037. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu X, Mertz JE. Distinct modes of regulation of transcription of hepatitis B virus by the nuclear receptors HNF4alpha and COUP-TF1. J Virol. 2003 Feb;77(4):2489-99. PMCID: PMC141100. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramière C, Scholtès C, Diaz O, Icard V, Perrin-Cocon L, Trabaud MA, Lotteau V, André P. Transactivation of the hepatitis B virus core promoter by the nuclear receptor FXRalpha. J Virol. 2008 Nov;82(21):10832-40. Epub 2008 Sep 3. PMCID: PMC2573182. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reese VC, Oropeza CE, McLachlan A. Independent activation of hepatitis B virus biosynthesis by retinoids, peroxisome proliferators, and bile acids. J Virol. 2013 Jan;87(2):991-7. Epub 2012 Nov 7. PMCID: PMC3554059. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang H, McLachlan A. Transcriptional regulation of hepatitis B virus by nuclear hormone receptors is a critical determinant of viral tropism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Feb 13;98(4):1841-6. Epub 2001 Feb 6. PMCID: PMC29344. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee CG, Homer RJ, Zhu Z, Lanone S, Wang X, Koteliansky V, Shipley JM, Gotwals P, Noble P, Chen Q, Senior RM, Elias JA. Interleukin-13 induces tissue fibrosis by selectively stimulating and activating transforming growth factor beta(1). J Exp Med. 2001 Sep 17;194(6):809-21. PMCID: PMC2195954. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarantino G, Cabibi D, Cammà C, Alessi N, Donatelli M, Petta S, Craxì A, Di Marco V. Liver eosinophilic infiltrate is a significant finding in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2008 Jul;15(7):523-30. Epub 2008 Feb 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacke F, Trautwein C, Yagmur E, Hellerbrand C, Wiest R, Brenner DA, Schnabl B. Up-regulated eotaxin plasma levels in chronic liver disease patients indicate hepatic inflammation, advanced fibrosis and adverse clinical course. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Aug;22(8):1256-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song YS, Fang CH, So BI, Park JY, Jun DW, Kim KS. Therapeutic effects of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor on non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis in the rat. Ann Hepatol. 2013 Jan-Feb;12(1):115-22. [PubMed]

- Wong SW, Ting YW, Yong YK, Tan HY, Barathan M, Riazalhosseini B, Bee CJ, Tee KK, Larsson M, Velu V, Shankar EM, Mohamed R. Chronic inflammation involves CCL11 and IL-13 to facilitate the development of liver cirrhosis and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2021 Apr;81(2):147-159. Epub 2021 Feb 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng SY, Wang X, Vijayan S, Tang Y, Kim YO, Padberg K, Regen T, Molokanova O, Chen T, Bopp T, Schild H, Brombacher F, Crosby JR, McCaleb ML, Waisman A, Bockamp E, Schuppan D. IL-4 Receptor Alpha Signaling through Macrophages Differentially Regulates Liver Fibrosis Progression and Reversal. EBioMedicine. 2018 Mar;29:92-103. Epub 2018 Feb 17. PMCID: PMC5925448. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto N. Oxidative-stress and IL-6 mediate the fibrogenic effects of [corrected] Kupffer cells on stellate cells. Hepatology. 2006 Dec;44(6):1487-501. Erratum in: Hepatology. 2007 Feb;45(2):546. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim KH, Shin HJ, Kim K, Choi HM, Rhee SH, Moon HB, Kim HH, Yang US, Yu DY, Cheong J. Hepatitis B virus X protein induces hepatic steatosis via transcriptional activation of SREBP1 and PPAR-gamma. Gastroenterology. 2007 May;132(5):1955-67. Epub 2007 Mar 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu YL, Peng XE, Zhu YB, Yan XL, Chen WN, Lin X. Hepatitis B virus X Protein induces hepatic steatosis by enhancing the expression of liver fatty acid binding protein. J Virol. 2015 Dec 4;90(4):1729-40. PMCID: PMC4733992. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na TY, Shin YK, Roh KJ, Kang SA, Hong I, Oh SJ, Seong JK, Park CK, Choi YL, Lee MO. Liver X receptor mediates hepatitis B virus X protein-induced lipogenesis in hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2009 Apr;49(4):1122-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu Y, Yang X, Kuang Q, Wu Y, Tan X, Lan J, Qiang Z, Feng T. HBx induced upregulation of FATP2 promotes the development of hepatic lipid accumulation. Exp Cell Res. 2023 Sep 1;430(1):113721. Epub 2023 Jul 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivasudhan E, Blake N, Lu Z, Meng J, Rong R. Hepatitis B Viral Protein HBx and the Molecular Mechanisms Modulating the Hallmarks of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Review. Cells. 2022 Feb 21;11(4):741. PMCID: PMC8870387. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho HK, Kim SY, Yoo SK, Choi YH, Cheong J. Fatty acids increase hepatitis B virus X protein stabilization and HBx-induced inflammatory gene expression. FEBS J. 2014 May;281(9):2228-39. Epub 2014 Apr 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oehler N, Volz T, Bhadra OD, Kah J, Allweiss L, Giersch K, Bierwolf J, Riecken K, Pollok JM, Lohse AW, Fehse B, Petersen J, Urban S, Lütgehetmann M, Heeren J, Dandri M. Binding of hepatitis B virus to its cellular receptor alters the expression profile of genes of bile acid metabolism. Hepatology. 2014 Nov;60(5):1483-93. Epub 2014 May 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong X, Song Y, Yin S, Wang J, Huang R, Wu C, Shi J, Li J. Clinical impact and mechanisms of hepatitis B virus infection concurrent with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022 Jul 20;135(14):1653-1663. PMCID: PMC9509100. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung YL, Wu ML. The role of promyelocytic leukemia protein in steatosis-associated hepatic tumors related to chronic hepatitis B virus Infection. Transl Oncol. 2018 Jun;11(3):743-754. Epub 2018 Apr 24. PMCID: PMC6050444. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li F, Ou Q, Lai Z, Pu L, Chen X, Wang L, Sun L, Liang X, Wang Y, Xu H, Wei J, Wu F, Zhu H, Wang L. The co-occurrence of chronic hepatitis B and fibrosis is associated with a decrease in hepatic global DNA methylation levels in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front Genet. 2021 Jul 14;12:671552. PMCID: PMC8318039. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomopoulos KC, Arvaniti V, Tsamantas AC, Dimitropoulou D, Gogos CA, Siagris D, Theocharis GJ, Labropoulou-Karatza C. Prevalence of liver steatosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a study of associated factors and of relationship with fibrosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Mar;18(3):233-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kleef LA, Choi HSJ, Brouwer WP, Hansen BE, Patel K, de Man RA, Janssen HLA, de Knegt RJ, Sonneveld MJ. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease increases risk of adverse outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis B. JHEP Rep. 2021 Aug 8;3(5):100350. PMCID: PMC8446794. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang SC, Su TH, Tseng TC, Chen CL, Hsu SJ, Liao SH, Hong CM, Liu CH, Lan TY, Yang HC, Liu CJ, Chen PJ, Kao JH. Distinct effects of hepatic steatosis and metabolic dysfunction on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol Int. 2023 Oct;17(5):1139-1149. Epub 2023 May 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim K, Choi S, Park SM. Association of fasting serum glucose level and type 2 diabetes with hepatocellular carcinoma in men with chronic hepatitis B infection: A large cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2018 Oct;102:103-113. Epub 2018 Sep 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang SH, Cho Y, Jeong SW, Kim SU, Lee JW; Korean NAFLD Study Group. From nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: Big wave or ripple? Clin Mol Hepatol. 2021 Apr;27(2):257-269. Epub 2021 Mar 22. PMCID: PMC8046627. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Wei S, Wei Y, Wang X, Xiao F, Feng Y, Zhu Q. The impact of concomitant metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease on adverse outcomes in patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis: a propensity score matching study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug 1;35(8):889-898. Epub 2023 Jun 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang P, Liu Z, Fan H, Shi T, Han X, Suo C, Chen X, Zhang T. Positive hepatitis B core antibody is associated with advanced fibrosis and mortality in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Mar 1;35(3):294-301. Epub 2022 Dec 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim D, Konyn P, Sandhu KK, Dennis BB, Cheung AC, Ahmed A. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease is associated with increased all-cause mortality in the United States. J Hepatol. 2021 Dec;75(6):1284-1291. Epub 2021 Aug 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai J, Zhang XJ, Ji YX, Zhang P, She ZG, Li H. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Pandemic Fuels the Upsurge in Cardiovascular Diseases. Circ Res. 2020 Feb 28;126(5):679-704. Epub 2020 Feb 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapper EB, Lok AS. Use of Liver Imaging and Biopsy in Clinical Practice. N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 24;377(8):756-768. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton MS, Heba ER, Hooker CA, Bashir MR, Fowler KJ, Sandrasegaran K, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Doo E, Van Natta ML, Lavine JE, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Sanyal A, Loomba R, Sirlin CB; NASH Clinical Research Network. Agreement Between Magnetic Resonance Imaging Proton Density Fat Fraction Measurements and Pathologist-Assigned Steatosis Grades of Liver Biopsies From Adults With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2017 Sep;153(3):753-761. Epub 2017 Jun 15. PMCID: PMC5695870. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu J, Liu S, Du S, Zhang Q, Xiao J, Dong Q, Xin Y. Diagnostic value of MRI-PDFF for hepatic steatosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2019 Jul;29(7):3564-3573. Epub 2019 Mar 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlas T, Petroff D, Sasso M, Fan JG, Mi YQ, de Lédinghen V, Kumar M, Lupsor-Platon M, Han KH, Cardoso AC, Ferraioli G, Chan WK, Wong VW, Myers RP, Chayama K, Friedrich-Rust M, Beaugrand M, Shen F, Hiriart JB, Sarin SK, Badea R, Jung KS, Marcellin P, Filice C, Mahadeva S, Wong GL, Crotty P, Masaki K, Bojunga J, Bedossa P, Keim V, Wiegand J. Individual patient data meta-analysis of controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) technology for assessing steatosis. J Hepatol. 2017 May;66(5):1022-1030. Epub 2016 Dec 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu L, Lu W, Li P, Shen F, Mi YQ, Fan JG. A comparison of hepatic steatosis index, controlled attenuation parameter and ultrasound as noninvasive diagnostic tools for steatosis in chronic hepatitis B. Dig Liver Dis. 2017 Aug;49(8):910-917. Epub 2017 Mar 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang J, Liu F, Wang F, Han T, Jing L, Ma Z, Gao Y. A Noninvasive Score Model for Prediction of NASH in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8793278. Epub 2017 Mar 2. PMCID: PMC5352864. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsome PN, Sasso M, Deeks JJ, Paredes A, Boursier J, Chan WK, Yilmaz Y, Czernichow S, Zheng MH, Wong VW, Allison M, Tsochatzis E, Anstee QM, Sheridan DA, Eddowes PJ, Guha IN, Cobbold JF, Paradis V, Bedossa P, Miette V, Fournier-Poizat C, Sandrin L, Harrison SA. FibroScan-AST (FAST) score for the non-invasive identification of patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis with significant activity and fibrosis: a prospective derivation and global validation study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr;5(4):362-373. Epub 2020 Feb 3. Erratum in: Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr;5(4):e3. PMCID: PMC7066580. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Pongpaibul A, Kaosombatwattana U, Bhanthumkomol P, Bandidniyamanon W, Pausawasdi N, Tanwandee T. The prevalence of steatohepatitis in chronic hepatitis B patients and its impact on disease severity and treatment response. Liver Int. 2017 Apr;37(4):542-551. Epub 2016 Oct 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li J, Le AK, Chaung KT, Henry L, Hoang JK, Cheung R, Nguyen MH. Fatty liver is not independently associated with the rates of complete response to oral antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients. Liver Int. 2020 May;40(5):1052-1061. Epub 2020 Mar 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen J, Wang ML, Long Q, Bai L, Tang H. High value of controlled attenuation parameter predicts a poor antiviral response in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2017 Aug 15;16(4):370-374. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin X, Chen YP, Yang YD, Li YM, Zheng L, Xu CQ. Association between hepatic steatosis and entecavir treatment failure in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e34198. Epub 2012 Mar 30. PMCID: PMC3316632. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi ZM, Corey KE, Lim JK. AGA clinical practice update on lifestyle modification using diet and exercise to achieve weight loss in the management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2021 Feb;160(3):912-918. Epub 2020 Dec 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufour JF, Anstee QM, Bugianesi E, Harrison S, Loomba R, Paradis V, Tilg H, Wong VW, Zelber-Sagi S. Current therapies and new developments in NASH. Gut. 2022 Jun 16;71(10):2123–34. Epub ahead of print. PMCID: PMC9484366. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsome PN, Buchholtz K, Cusi K, Linder M, Okanoue T, Ratziu V, Sanyal AJ, Sejling AS, Harrison SA; NN9931-4296 Investigators. A placebo-controlled trial of subcutaneous Semaglutide in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021 Mar 25;384(12):1113-1124. Epub 2020 Nov 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francque SM, Bedossa P, Ratziu V, Anstee QM, Bugianesi E, Sanyal AJ, Loomba R, Harrison SA, Balabanska R, Mateva L, Lanthier N, Alkhouri N, Moreno C, Schattenberg JM, Stefanova-Petrova D, Vonghia L, Rouzier R, Guillaume M, Hodge A, Romero-Gómez M, Huot-Marchand P, Baudin M, Richard MP, Abitbol JL, Broqua P, Junien JL, Abdelmalek MF; NATIVE Study Group. A randomized, controlled trial of the pan-PPAR agonist Lanifibranor in NASH. N Engl J Med. 2021 Oct 21;385(17):1547-1558. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison SA, Bashir MR, Guy CD, Zhou R, Moylan CA, Frias JP, Alkhouri N, Bansal MB, Baum S, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Taub R, Moussa SE. Resmetirom (MGL-3196) for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2019 Nov 30;394(10213):2012-2024. Epub 2019 Nov 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Taub RA, Barbone JM, Harrison SA. Hepatic Fat Reduction Due to Resmetirom in Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Is Associated With Improvement of Quality of Life. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jun;20(6):1354-1361.e7. Epub 2021 Jul 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi ZM, Ratziu V, Loomba R, Rinella M, Anstee QM, Goodman Z, Bedossa P, Geier A, Beckebaum S, Newsome PN, Sheridan D, Sheikh MY, Trotter J, Knapple W, Lawitz E, Abdelmalek MF, Kowdley KV, Montano-Loza AJ, Boursier J, Mathurin P, Bugianesi E, Mazzella G, Olveira A, Cortez-Pinto H, Graupera I, Orr D, Gluud LL, Dufour JF, Shapiro D, Campagna J, Zaru L, MacConell L, Shringarpure R, Harrison S, Sanyal AJ; REGENERATE Study Investigators. Obeticholic acid for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: interim analysis from a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019 Dec 14;394(10215):2184-2196. Epub 2019 Dec 5. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 Aug 1;396(10247):312. Erratum in: Lancet. 2021 Jun 19;397(10292):2336. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Nader F, Loomba R, Anstee QM, Ratziu V, Harrison S, Sanyal AJ, Schattenberg JM, Barritt AS, Noureddin M, Bonacci M, Cawkwell G, Wong B, Rinella M; Randomized global phase 3 study to evaluate the impact on NASH with fibrosis of obeticholic acid treatment (REGENERATE) Study Investigators. Obeticholic acid impact on quality of life in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: REGENERATE 18-month interim analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2050-2058.e12. Epub 2021 Jul 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong GL, Chan HL, Yu Z, Chan AW, Choi PC, Chim AM, Chan HY, Tse CH, Wong VW. Coincidental metabolic syndrome increases the risk of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis B--a prospective cohort study with paired transient elastography examinations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Apr;39(8):883-93. Epub 2014 Feb 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan R, Niu J, Ma H, Xie Q, Cheng J, Rao H, Dou X, Xie J, Zhao W, Peng J, Gao Z, Gao H, Chen X, Chen J, Li Q, Tang H, Zhang Z, Ren H, Cheng M, Liang X, Zhu C, Wei L, Jia J, Sun J, Hou J; Chronic Hepatitis B Study Consortium. Association of central obesity with hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B receiving antiviral therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Aug;54(3):329-338. Epub 2021 Jun 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan KE, Ng CH, Fu CE, Quek J, Kong G, Goh YJ, Zeng RW, Tseng M, Aggarwal M, Nah B, Chee D, Wong ZY, Zhang S, Wang JW, Chew NWS, Dan YY, Siddiqui MS, Noureddin M, Sanyal AJ, Muthiah M. The Spectrum and Impact of Metabolic Dysfunction in MAFLD: A Longitudinal Cohort Analysis of 32,683 Overweight and Obese Individuals. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Sep;21(10):2560-2569.e15. Epub 2022 Oct 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modeling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Mar;2(3):161-176. Epub 2016 Dec 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gower E, Estes C, Blach S, Razavi-Shearer K, Razavi H. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2014 Nov;61(1 Suppl):S45-57. Epub 2014 Jul 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moucari R, Asselah T, Cazals-Hatem D, Voitot H, Boyer N, Ripault MP, Sobesky R, Martinot-Peignoux M, Maylin S, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Paradis V, Vidaud M, Valla D, Bedossa P, Marcellin P. Insulin resistance in chronic hepatitis C: association with genotypes 1 and 4, serum HCV RNA level, and liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008 Feb;134(2):416-23. Epub 2007 Nov 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adinolfi LE, Rinaldi L, Guerrera B, Restivo L, Marrone A, Giordano M, Zampino R. NAFLD and NASH in HCV Infection: Prevalence and Significance in Hepatic and Extrahepatic Manifestations. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 May 25;17(6):803. PMCID: PMC4926337. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzouk D, Sass J, Bakr I, El Hosseiny M, Abdel-Hamid M, Rekacewicz C, Chaturvedi N, Mohamed MK, Fontanet A. Metabolic and cardiovascular risk profiles and hepatitis C virus infection in rural Egypt. Gut. 2007 Aug;56(8):1105-10. Epub 2006 Sep 6. PMCID: PMC1955512. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai PS, Cheng YM, Wang CC, Kao JH. The impact of concomitant hepatitis C virus infection on liver and cardiovascular risks in patients with metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Nov 1;35(11):1278-1283. Epub 2023 Sep 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Omary A, Byth K, Weltman M, George J, Eslam M. The importance and impact of recognizing metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Dig Dis. 2022 Jan;23(1):33-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi Z, A.Q., Marietti M, & al, e. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors, and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;15:11–20. [CrossRef]

- Negro F. Facts and fictions of HCV and comorbidities: steatosis, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases. J Hepatol. 2014 Nov;61(1 Suppl):S69-78. Epub 2014 Nov 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyanari Y, Atsuzawa K, Usuda N, Watashi K, Hishiki T, Zayas M, Bartenschlager R, Wakita T, Hijikata M, Shimotohno K. The lipid droplet is an important organelle for hepatitis C virus production. Nat Cell Biol. 2007 Sep;9(9):1089-97. Epub 2007 Aug 26. Erratum in: Nat Cell Biol. 2007 Oct;9(10):1216. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André P, Komurian-Pradel F, Deforges S, Perret M, Berland JL, Sodoyer M, Pol S, Bréchot C, Paranhos-Baccalà G, Lotteau V. Characterization of low- and very-low-density hepatitis C virus RNA-containing particles. J Virol. 2002 Jul;76(14):6919-28. PMCID: PMC136313. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapadia SB, Chisari FV. Hepatitis C virus RNA replication is regulated by host geranylgeranylation and fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Feb 15;102(7):2561-6. Epub 2005 Feb 7. PMCID: PMC549027. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamane D, McGivern DR, Wauthier E, Yi M, Madden VJ, Welsch C, Antes I, Wen Y, Chugh PE, McGee CE, Widman DG, Misumi I, Bandyopadhyay S, Kim S, Shimakami T, Oikawa T, Whitmire JK, Heise MT, Dittmer DP, Kao CC, Pitson SM, Merrill AH Jr, Reid LM, Lemon SM. Regulation of the hepatitis C virus RNA replicase by endogenous lipid peroxidation. Nat Med. 2014 Aug;20(8):927-35. Epub 2014 Jul 27. PMCID: PMC4126843. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann S, Krajewski M, Scherer C, Scholz V, Mordhorst V, Truschow P, Schöbel A, Reimer R, Schwudke D, Herker E. Complex lipid metabolic remodeling is required for efficient hepatitis C virus replication. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2018 Sep;1863(9):1041-1056. Epub 2018 Jun 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abomughaid M, Tay ESE, Pickford R, Malladi C, Read SA, Coorssen JR, Gloss BS, George J, Douglas MW. PEMT Mediates Hepatitis C Virus-Induced Steatosis, Explains Genotype-Specific Phenotypes and Supports Virus Replication. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 May 15;24(10):8781. PMCID: PMC10218061. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola N, Rosa Z, Cirillo G, Stanzione M, Macera M, Boemio A, Grandone A, Pisaturo M, Marrone A, Adinolfi LE, Sagnelli E, Miraglia del Giudice E. TM6SF2 E167K variant is associated with severe steatosis in chronic hepatitis C, regardless of PNPLA3 polymorphism. Liver Int. 2015 Aug;35(8):1959-63. Epub 2015 Jan 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng Y, Dharancy S, Malapel M, Desreumaux P. Hepatitis C virus infection down-regulates the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha and carnitine palmitoyl acyl-CoA transferase 1A. World J Gastroenterol. 2005 Dec 28;11(48):7591-6. PMCID: PMC4727219. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda M, Li K, Beard MR, Showalter LA, Scholle F, Lemon SM, Weinman SA. Mitochondrial injury, oxidative stress, and antioxidant gene expression are induced by hepatitis C virus core protein. Gastroenterology. 2002 Feb;122(2):366-75. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi T, Yoshida T, Harada M, Hisamoto T, Nagao Y, Ide T, Taniguchi E, Kumemura H, Hanada S, Maeyama M, Baba S, Koga H, Kumashiro R, Ueno T, Ogata H, Yoshimura A, Sata M. Hepatitis C virus down-regulates insulin receptor substrates 1 and 2 through up-regulation of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. Am J Pathol. 2004 Nov;165(5):1499-508. PMCID: PMC1618659. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miquilena-Colina ME, Lima-Cabello E, Sánchez-Campos S, García-Mediavilla MV, Fernández-Bermejo M, Lozano-Rodríguez T, Vargas-Castrillón J, Buqué X, Ochoa B, Aspichueta P, González-Gallego J, García-Monzón C. Hepatic fatty acid translocase CD36 upregulation is associated with insulin resistance, hyperinsulinaemia and increased steatosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2011 Oct;60(10):1394-402. Epub 2011 Jan 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serfaty L, Andreani T, Giral P, Carbonell N, Chazouillères O, Poupon R. Hepatitis C virus induced hypobetalipoproteinemia: a possible mechanism for steatosis in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2001 Mar;34(3):428-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackel-Cram C, Qiao L, Xiang Z, Brownlie R, Zhou Y, Babiuk L, Liu Q. Hepatitis C virus genotype-3a core protein enhances sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 activity through the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt-2 pathway. J Gen Virol. 2010 Jun;91(Pt 6):1388-95. Epub 2010 Feb 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clément S, Peyrou M, Sanchez-Pareja A, Bourgoin L, Ramadori P, Suter D, Vinciguerra M, Guilloux K, Pascarella S, Rubbia-Brandt L, Negro F, Foti M. Down-regulation of phosphatase and tensin homolog by hepatitis C virus core 3a in hepatocytes triggers the formation of large lipid droplets. Hepatology. 2011 Jul;54(1):38-49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gottardi A, Pazienza V, Pugnale P, Bruttin F, Rubbia-Brandt L, Juge-Aubry CE, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha and -gamma mRNA levels are reduced in chronic hepatitis C with steatosis and genotype 3 infection. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2006;23(1):107–14. [CrossRef]

- Dharancy S, Malapel M, Perlemuter G, Roskams T, Cheng Y, Dubuquoy L, Podevin P, Conti F, Canva V, Philippe D, Gambiez L, Mathurin P, Paris JC, Schoonjans K, Calmus Y, Pol S, Auwerx J, Desreumaux P. Impaired expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha during hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2005 Feb;128(2):334-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zylberberg H, Rimaniol AC, Pol S, Masson A, De Groote D, Berthelot P, Bach JF, Bréchot C, Zavala F. Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors in chronic hepatitis C: a correlation with histological fibrosis and activity. J Hepatol. 1999 Feb;30(2):185-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki R, Devhare PB, Steele R, Ray R, Ray RB. Hepatitis C virus-induced CCL5 secretion from macrophages activates hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2017 Sep;66(3):746-757. Epub 2017 Jul 18. PMCID: PMC5570659. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fartoux L, Chazouillères O, Wendum D, Poupon R, Serfaty L. Impact of steatosis on progression of fibrosis in patients with mild hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005 Jan;41(1):82-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohata K, Hamasaki K, Toriyama K, Matsumoto K, Saeki A, Yanagi K, Abiru S, Nakagawa Y, Shigeno M, Miyazoe S, Ichikawa T, Ishikawa H, Nakao K, Eguchi K. Hepatic steatosis is a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Cancer. 2003 Jun 15;97(12):3036-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poynard T, Ratziu V, McHutchison J, Manns M, Goodman Z, Zeuzem S, Younossi Z, Albrecht J. Effect of treatment with peginterferon or interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin on steatosis in patients infected with hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003 Jul;38(1):75-85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adinolfi LE, Restivo L, Zampino R, Guerrera B, Lonardo A, Ruggiero L, Riello F, Loria P, Florio A. Chronic HCV infection is a risk of atherosclerosis. Role of HCV and HCV-related steatosis. Atherosclerosis. 2012;221:496–502. [CrossRef]

- Rau M, Buggisch P, Mauss S, Boeker KHW, Klinker H, Müller T, Stoehr A, Schattenberg JM, Geier A. Prognostic impact of steatosis in the clinical course of chronic HCV infection-Results from the German Hepatitis C-Registry. PLoS One. 2022 Jun 16;17(6):e0264741. PMCID: PMC9203066. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krassenburg LAP, Maan R, Ramji A, Manns MP, Cornberg M, Wedemeyer H, de Knegt RJ, Hansen BE, Janssen HLA, de Man RA, Feld JJ, van der Meer AJ. Clinical outcomes following DAA therapy in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis depend on disease severity. J Hepatol. 2021 May;74(5):1053-1063. Epub 2020 Nov 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do A, Esserman DA, Krishnan S, Lim JK, Taddei TH, Hauser RG 3rd, Tate JP, Re VL 3rd, Justice AC. Excess weight gain after cure of hepatitis C infection with direct-acting antivirals. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Jul;35(7):2025-2034. Epub 2020 Apr 27. Erratum in: J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Oct;35(10):3140. PMCID: PMC7352003. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasiewicz K, Flisiak R, Jaroszewicz J, Małkowski P, Pawłowska M, Piekarska A, Simon K, Zarębska-Michaluk D. Recommendations of the Polish group of experts for HCV for the treatment of hepatitis C in 2023. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2023 Mar;9(1):1-8. Epub 2023 Mar 24. PMCID: PMC10090994. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun D, Dai M, Shen S, Li C, Yan X. Analysis of naturally occurring resistance-associated variants to NS3/4A protein inhibitors, NS5A protein inhibitors, and NS5B polymerase inhibitors in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gene Expr. 2018 Mar 21;18(1):63-69. Epub 2017 Dec 8. PMCID: PMC5885147. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison SA, Brunt EM, Qazi RA, Oliver DA, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Di Bisceglie AM, Bacon BR. Effect of significant histologic steatosis or steatohepatitis on response to antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 Jun;3(6):604-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaguarnera M, Vacante M, Russo C, Gargante MP, Giordano M, Bertino G, Neri S, Malaguarnera M, Galvano F, Li Volti G. Rosuvastatin reduces nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with α-interferon and ribavirin: Rosuvastatin reduces NAFLD in HCV patients. Hepat Mon. 2011 Feb;11(2):92-8. PMCID: PMC3206670. [PubMed]

- Look MP, Gerard A, Rao GS, Sudhop T, Fischer HP, Sauerbruch T, Spengler U. Interferon/antioxidant combination therapy for chronic hepatitis C--a controlled pilot trial. Antiviral Res. 1999 Sep;43(2):113-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houglum K, Venkataramani A, Lyche K, Chojkier M. A pilot study of the effects of d-alpha-tocopherol on hepatic stellate cell activation in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 1997 Oct;113(4):1069-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rout G, Nayak B, Patel AH, Gunjan D, Singh V, Kedia S, Shalimar. Therapy with oral directly acting agents in hepatitis C infection is associated with reduction in fibrosis and increase in hepatic steatosis on transient elastography. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2019 Mar-Apr;9(2):207-214. Epub 2018 Jun 21. PMCID: PMC6477071. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun HY, Cheng PN, Tseng CY, Tsai WJ, Chiu YC, Young KC. Favouring modulation of circulating lipoproteins and lipid loading capacity by direct antiviral agents grazoprevir/elbasvir or ledipasvir/sofosbuvir treatment against chronic HCV infection. Gut. 2018 Jul;67(7):1342-1350. Epub 2017 Jun 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hum J, Jou JH, Green PK, Berry K, Lundblad J, Hettinger BD, Chang M, Ioannou GN. Improvement in glycemic control of type 2 diabetes after successful treatment of hepatitis C virus. Diabetes Care. 2017 Sep;40(9):1173-1180. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt AA, Yan P, Shuaib A, Abou-Samra AB, Shaikh OS, Freiberg MS. Direct-acting antiviral therapy for HCV infection is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease events. Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar;156(4):987-996.e8. Epub 2018 Nov 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya D, Aronsohn A, Price J, Lo Re V; AASLD-IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C Guidance 2023 Update: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2023 May 25:ciad319. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao X, Chen L, Zhao Y, Liu Y, Shi R, Jiang B, Mi Y, Xu L. A novel noninvasive diagnostic model of HBV-related inflammation in chronic hepatitis B virus infection patients with concurrent nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Mar 23;9:862879. PMCID: PMC8984271. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Lin S, Jiang D, Li M, Chen Y, Li J, Fan J. Chronic hepatitis B and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Conspirators or competitors? Liver Int. 2020 Mar;40(3):496-508. Epub 2020 Jan 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaheen AA, AlMattooq M, Yazdanfar S, Burak KW, Swain MG, Congly SE, Borman MA, Lee SS, Myers RP, Coffin CS. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate significantly decreases serum lipoprotein levels compared with entecavir nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy in chronic hepatitis B carriers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 Sep;46(6):599-604. Epub 2017 Jul 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang FM, Wang YP, Lang HC, Tsai CF, Hou MC, Lee FY, Lu CL. Statins decrease the risk of decompensation in hepatitis B virus- and hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis: A population-based study. Hepatology. 2017 Sep;66(3):896-907. Epub 2017 May 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon TG, Duberg AS, Aleman S, Hagstrom H, Nguyen LH, Khalili H, Chung RT, Ludvigsson JF. Lipophilic statins and risk for hepatocellular carcinoma and death in patients with chronic viral hepatitis: results from a nationwide Swedish population. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Sep 3;171(5):318-327. Epub 2019 Aug 20. PMCID: PMC8246628. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Yishay I, Shaul Y, Shlomai A. Hepatocyte metabolic signaling pathways and regulation of hepatitis B virus expression. Liver Int. 2011 Mar;31(3):282-90. Epub 2011 Jan 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Xie Q. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and viral hepatitis. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2022 Feb 28;10(1):128-133. Epub 2021 Oct 8. PMCID: PMC8845159. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metabolic complications |

| Insulin Resistance |

| Dyslipidemia – elevated triglyceride and LDL cholesterol levels |

| Obesity |

| Hypertension |

| Cardiovascular disease |

| Non-metabolic Complications |

| Hepatic fibrosis |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) |

| Chronic liver disease-related complications - ascites, encephalopathy, and variceal bleeding |

| Increased risk of infection |

| Quality of life - fatigue, discomfort, and the need for ongoing medical care |

| Genotype 3 HCV | Non-Genotype 3 HCV | |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of steatosis | Viral steatosis | Metabolic steatosis |

| Location | Periportal zone (acinar 1) | Centrilobular (acinar 3) |

| HCV RNA viral load | Co-relate with MAFLD severity | No relation with MAFLD severity |

| Response to Antiviral | MAFLD reversible with SVR | Reduced response to therapy |

| Consequence | High rate of steatosis, more rapid progression to advanced fibrosis, and increased HCC risk | Lower rates of steatosis, slower progression to advanced fibrosis, and lower HCC risk |

| HBV | HCV | |

|---|---|---|

| CHB/CHC promoting fatty liver | No | Yes |

| CHB/CHC predisposing to diabetes | Unknown | Yes |

| CHB/CHC worsening lipid profile | No | No |

| MAFLD promoting CHB/CHC related fibrosis | Yes | Yes |

| MAFLD promoting CHB/CHC related HCC | Yes | Yes |

| MAFLD promoting viral replication | No | Yes |

| MAFLD reducing the antiviral response | Unknown | IFN-α: Yes DAAs: unknown |

| Drugs for diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia reducing the antiviral response | Unknown | IFN-α: unknown Some DAAs: Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).