Submitted:

05 November 2023

Posted:

09 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

“Any economist will tell you that diversification is the key to a secure portfolio. Any geneticist will tell you that diversification is key to maintaining hardy species of plants and animals. But somehow, when it comes to racial politics, the virtues of diversity are lost. Diversity in health care is not about fair representation - it is about saving lives.” – Commissioner George Strait, Associate Vice Chancellor for Public Affairs, University of California, Berkeley

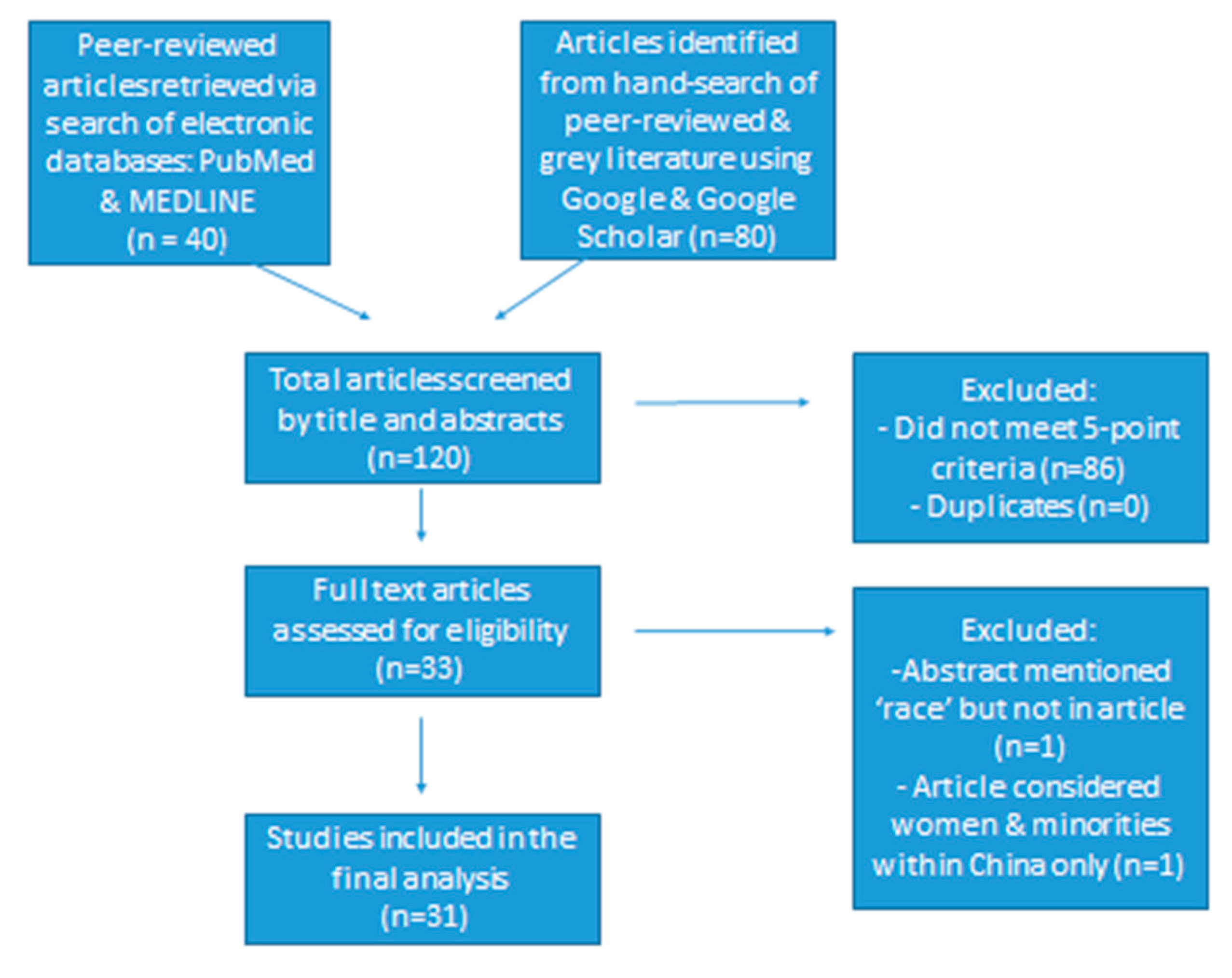

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

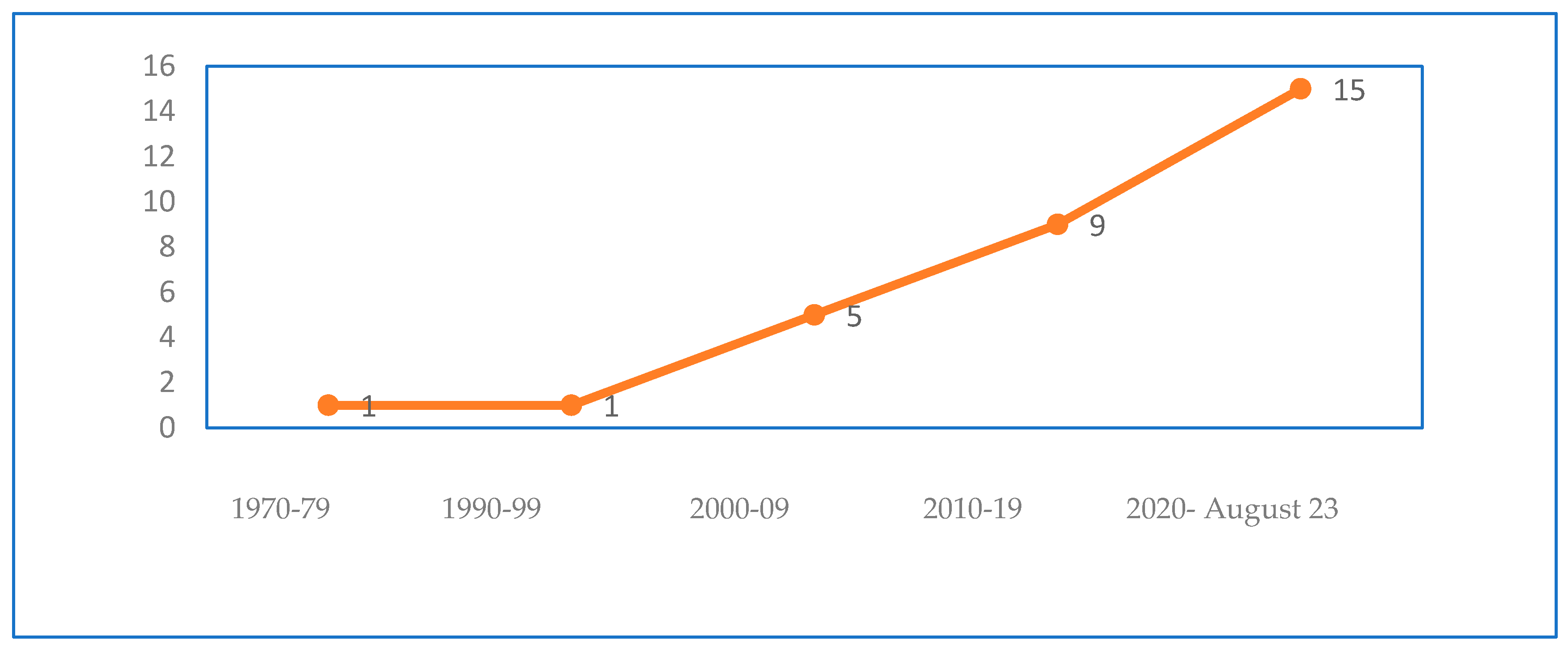

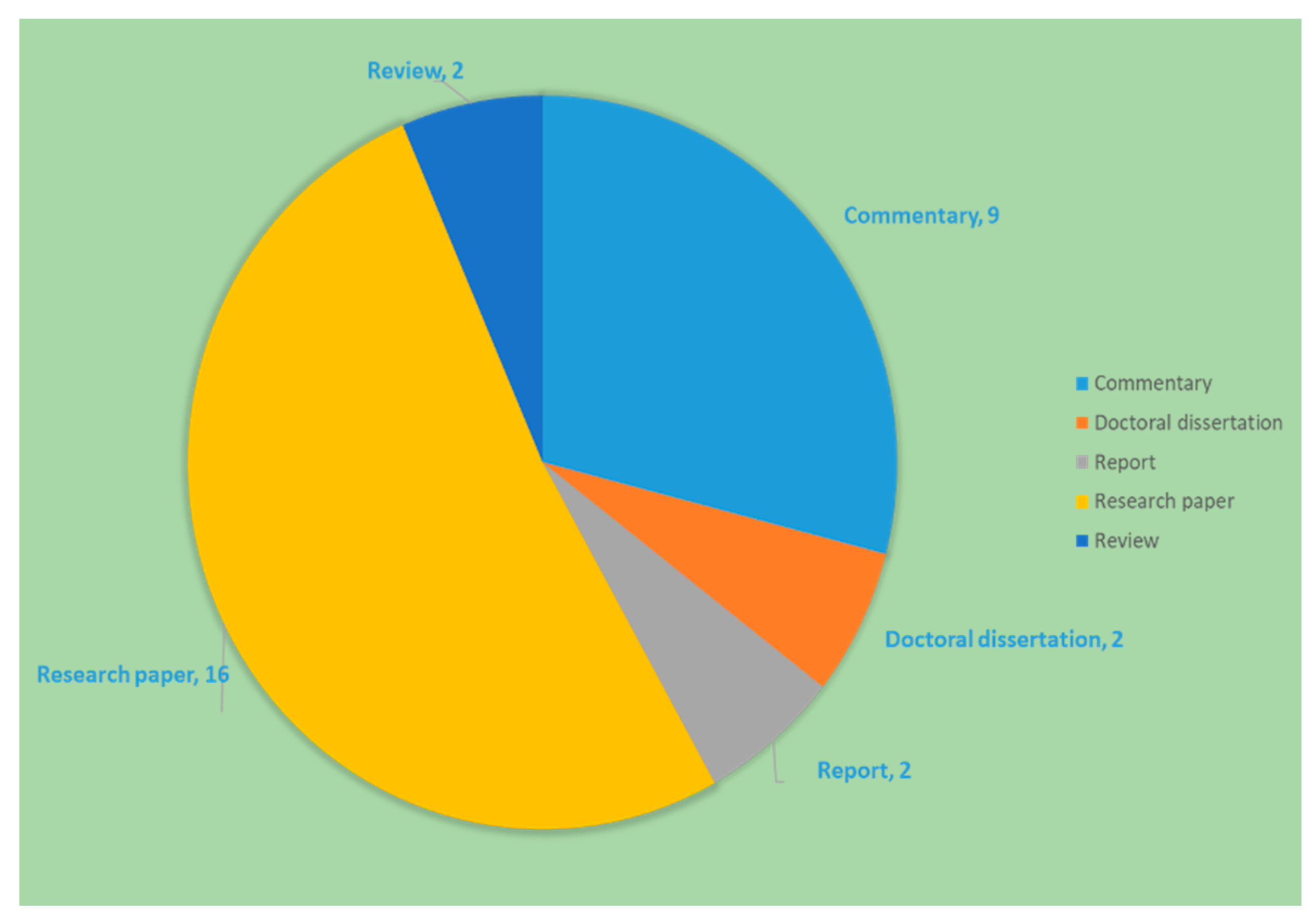

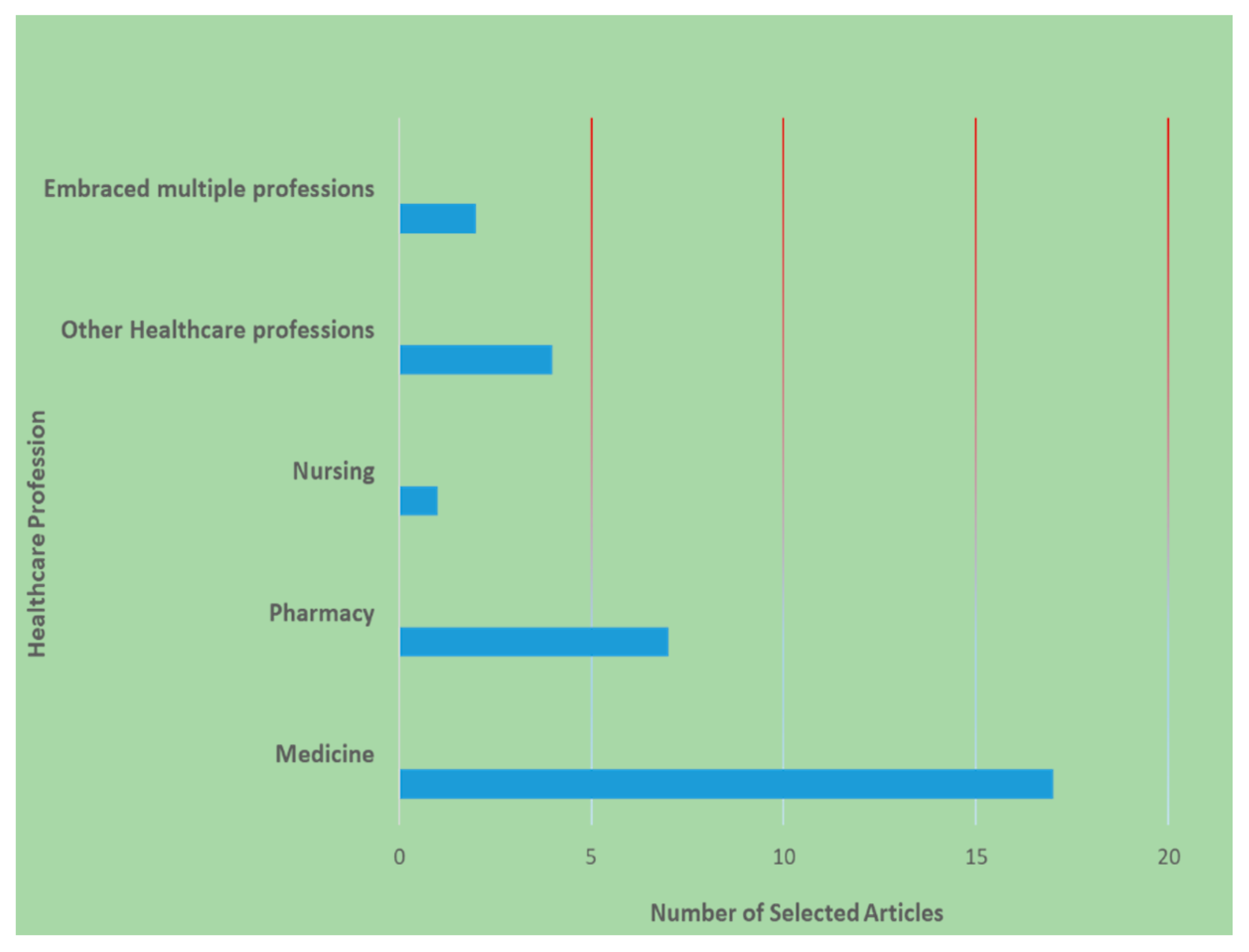

3.1. Descriptive results

4. Discussion

- Underrepresentation

- Intersectionality lens/approach

- Equity

- Professional support and networks

- Leadership and mentoring

- Sexual harassment and misconduct

- Retention and attrition

- Improving diversity

4.1. Category I: Barriers and Challenges

4.1.1. Underrepresentation

4.1.2. Intersectionality lens/approach

4.1.2. Equity

4.1.3. Professional support and networks

4.1.4. Leadership and mentoring

4.1.5. Sexual harassment & misconduct

4.2. Category II: Opportunities and Examples

4.2.1. Retention and Attrition

4.2.2. Improving diversity

| Seven studies [25,26,27,28,46,47,48] addressed pharmacy health professionals, of which Queaneau [47] examined occupational patterns of occupational segregation by race and ethnicity in healthcare for 16 healthcare professions (including pharmacy). The pharmacy profession has been experiencing demographic shifts in the past few decades, particularly in the US and UK. Recent data have shown an increase in WoC in the pharmacy workforce in the US [49], UK [50,51], and Canada [52]. Platts et al, concluded in 1999, the feminization of the pharmacy profession and described the profession as being in transition. They further implied that acceptance of flexible working patterns, childcare availability, increasing numbers of ethnic minorities in pharmacy, necessitated that the profession be proactive in its recruitment and flexible with its dynamic nature [46]. The pharmacy profession has become one of the most attractive professions to women due to its flexible working and part-time hours, and general working conditions. Despite the growing numbers of women pharmacists of color, there is little empirical research on the experiences, professional development, and advancement of WoC. More work must be done to demonstrate the profession’s commitment to diversity, beginning with student recruitment at colleges of pharmacy [26]. Hahn et al. [28] explored career engagement, interest, and retention of minority students at multiple schools and colleges of pharmacy and found that participants were most confident in their ability to obtain a job in community or hospital pharmacy but least confident about academic teaching or the pharmaceutical industry. While the study sample was small and not generalizable, the dearth of WoC in academic teaching needs to be addressed. Similarly, Rockich-Winston et al. [27] found that intersectionality of identities created advantages in belonging to some social categories and disadvantages in belonging to others for student pharmacists who are developing their professional identities. Chisholm-Burns et al. [48] noted the lack of women in leadership positions, citing that only 18% of all hospital CEOs were women, and in the healthcare sector, women leaders accounted for a mere 25%. Though it has been noted that inclusion of women in business leadership significantly increases firm value, financial performance, economic growth, innovation, social responsibility and capital, such inclusion continues to be low in the healthcare professions. The article addressed challenges and barriers to professional development of women and presented strategies identified by the American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists (ASHP) Women in Pharmacy Leadership Steering Committee that includes above all, soul searching and reflection by the pharmacy community to make concerted efforts to achieve equality in compensation and representation of women in pharmacy. A yet to be addressed area is the prospect of unionization of pharmacists, particularly women, since unions tend to be predominantly male dominated. However, the lower numbers of women in leadership positions make it challenging for women to unionize even though they may benefit from collective bargaining. Possibly, such unionization may be likely to occur within homogenous workplaces and unions, when available ought to offer training and mentoring programs for WoC [47]. Lastly, Abdul-Muktabbir et al. used the term “intersectional invisibility” to describe the marginalization experienced by black, indigenous, and persons of color (BIPOC) women and the harms perpetuated by single-axis movements that fail to take into account the experiences of discrimination of BIPOC women and the difference from minoritized men [25]. |

4.3. Research Gaps and Areas for future work

4.3.1. Research mostly exploratory.

4.3.2. Limited use of intersectionality.

4.3.3. Non-representative sampling.

4.3.4. Aggregation across groups

4.3.5. Variability in terminology and classifications

4.3.6. Generalizability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Betancourt, J.R.; King, R.K. Unequal treatment: the Institute of Medicine report and its public health implications. Public health rep 2003, 118, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, L.W. Missing persons: Minorities in the health professions, a report of the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce. 2004. https://api.drum.lib.umd.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/ffa2d34e-ba9f-4b01-afa2-58016e8658a8/content (accessed on 29/10/2023).

- Gaboury, I.; Bujold, M.; Boon, H.; Moher, D. Interprofessional collaboration within Canadian integrative healthcare clinics: Key components. Soc Sci Med 2009, 69, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25032386/ (accessed on 27/10/2023).

- U.S. Census Bureau. Population estimates. National characteristics: vintage 2015. www.census.gov/popest/data/national/asrh/2015/index.html (accessed on 26/10/2023).

- Glynn, S.J. The new breadwinners: 2010 update. www.americanprogress.org/issues/labor/report/2012/04/16/11377/the-new-breadwinners-2010-update/ (accessed on 26/10/2023).

- Shalala, D.E.; Agogino, A.M.; Bailyn, L; Birgeneau, R.J.; Cauce, A.M.; Deangelis, C.D.; et al. Beyond Bias and Barriers. Fulfilling the potential of women in academic science and engineering. National Academy of Sciences. 2007. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/11741/bias_and_barriers_summary.pdf (accessed on 26/10/2023).

- Johns, M.L. Breaking the glass ceiling: structural, cultural, and organizational barriers preventing women from achieving senior and executive positions. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3544145 (accessed on 26/10/2023).

- World Health Organization (p26). Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/health-workforce/delivered-by-women-led-by-men.pdf?sfvrsn=94be9959_2 (accessed on 26/10/2023).

- Himmelstein, K.E.W.; Venkataramani, A.S. Economic vulnerability among US female health care workers: potential impact of a $15-per-hour minimum wage. Am J Pub Health 2019, 109, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frogner, B.K. The health care job engine: where do they come from and what do they say about our future? Med Care Res Rev 2018, 75, 219–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, E.N. Forced to care: coercion and caregiving in America. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 2010. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=MjEFTl3KhfMC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=12.%09Glenn+EN.+Forced+to+care:+coercion+and+caregiving+in+America.+Cambridge+(MA):+Harvard+University+Press%3B+2010.&ots=tCyJwsKTeb&sig=ZHmeACYsgdI-_dBOfGpq74Fosek#v=onepage&q=12.%09Glenn%20EN.%20Forced%20to%20care%3A%20coercion%20and%20caregiving%20in%20America.%20Cambridge%20(MA)%3A%20Harvard%20University%20Press%3B%202010.&f=false (accessed on 30/10/2023).

- Duffy, M. Making care count: a century of gender, race, and paid care work. New Brunswick (NJ): Rutgers University Press; 2011. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=aXVnTvXr-xwC&oi=fnd&pg=PR10&dq=13.%09Duffy+M.+Making+care+count:+a+century+of+gender,+race,+and+paid+care+work.+New+Brunswick+(NJ):+Rutgers+University+Press%3B+2011.&ots=sgMZ8Lflls&sig=XUpuwB7kcutqlm0-SLy4zyv8q5g#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 30/10/2023).

- Glenn, E.N. From servitude to service work: historical continuities in the racial division of paid reproductive labor. Signs J Women Cult Soc 1992, 18, 1–43, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3174725?origin=JSTOR-pdf. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, E. Opportunity denied: limiting Black women to devalued work. New Brunswick (NJ): Rutgers University Press; 2011. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=QxuM454youwC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=15.%09Branch+E.+Opportunity+denied:+limiting+Black+women+to+devalued+work.+New+Brunswick+(NJ):+Rutgers+University+Press%3B+2011.&ots=7nmQKMn6P-&sig=8wevmIH-hw6ixdYprdyC3NUcZxo#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 30/10/2023). Available online:.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé W., "On Intersectionality: Essential Writings"; 2017. Faculty Books. 255. https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/books/255 (accessed on 26/10/2023).

- Salsberg, E; Richwine, C.; Westergaard, S, et al. Estimation and Comparison of Current and Future Racial/Ethnic Representation in the US Health Care Workforce. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e213789. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, S.; Thomas, A. Steps for conducting a scoping review. J Grad Med Educ 2022, 14, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verduzco-Gutierrez, M.; Wescott, S.; Amador, J.; Hayes, A.A.; Owen, M.; Chatterjee, A. Lasting solutions for advancement of women of color. Acad Med 2022, 97, 1587–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramas, M.E.; Webber, S.; Braden, A.L.; Goelz, E.; Linzer, M.; Farley, H. Innovative wellness models to support advancement and retention among women physicians. Pediatrics, 2021; 148(Supplement 2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.V.; Wake, M.; Carapinha, R.; Normand, S.L.; Wolf, R.E.; Norris, K.; Reede, J.Y. Rationale and Design of the Women and Inclusion in Academic Medicine Study. Ethn Dis 2016, 26, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.Y.; Bigby, J.; Kleinpeter, M.; Mitchell, J.; Camacho, D.; Dan, A.; Sarto, G. Promoting the Advancement of Minority Women Faculty in Academic Medicine: The National Centers of Excellence in Women’s Health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2001, 10, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.E. An Historical Perspective of African American Women in Professional Pharmacy Associations, 1900-1970. Pharm Hist (Lond) 2022, 52, 115–127, https://docserver.ingentaconnect.com/deliver/connect/bshp/00791393/v52n4/s3.pdf?expires=1698269824&id=0000&titleid=72010666&checksum=71CD27F36BB2F2C57653C3999C9E2662&host=https://www.ingentaconnect.com (accessed on 26/10/2023). [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M.L. Learning from their Journey: Black Women in Graduate Health Professions Education. Doctoral thesis, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, California, 2020. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/etd/936 (accessed on 26/10/2023).

- Abdul-Mutakabbir, J.C.; Arya, V.; Butler, L. Acknowledging the intersection of gender inequity and racism: Identifying a path forward in pharmacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2022, 79, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, K.; Bower, P.; Hassell, K. Exploring the career choices of White and Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic women pharmacists: a qualitative study. Int J Pharm Pract 2018, 26, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockich-Winston, N.; Robinson, A.; Arif, S.A.; Steenhof, N.; Kellar, J. The Influence of Intersectionality on Professional Identity Formation among Underrepresented Pharmacy Students. Am J Pharm Educ 2023, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, F.T.; Bush, A.A.; Zhang, K.; Patel, A.; Lewis, K.; Jackson, A.; McLaughlin, J.E. Exploring the career engagement, interests, and goals of pharmacy students identifying as underrepresented racial minorities. Am J Pharm Educ 2021, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspinall, C.; Jacobs, S.; Frey, R. Intersectionality and nursing leadership: An integrative review. J Clin Nurs 2023, 32, 2466–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samra, R.; Hankivsky, O. Adopting an intersectionality framework to address power and equity in medicine. Lancet 2021, 397, 857–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, E.; Waljee, J.; Dimick, J.; Mulholland, M. Eliminating Institutional Barriers to Career Advancement for Diverse Faculty in Academic Surgery. Ann Surg 2019, 270, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, L.L.; Byars-Winston, A.; Wang, M.F. Viewing Clinical Research Career Development Through the Lens of Social Cognitive Career Theory. Adv Health Sci Educ 2006, 11, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruge, E.; Lakoski, J.M.; Luban, N.; Lipton, J.M.; Poplack, D.G.; Hagey, A.; Felgenhauer, J.; Hilden, J.; Margolin, J.; Vaiselbuh, S.R.; Sakamoto, K.M. Increasing Diversity in Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011, 57, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, J.; Whelan, B.; Pollard-Larkin, J.; Paradis, K.C.; Scarpelli, M.; Sun, C.; ... Castillo, R. Diversity and professional advancement in medical physics. Adv Radiat Oncol 2023, 8, 101057. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, S.; Chawla, A.; Hussain, M.; Karimuddin, A.A.; Khosa, F. The state of diversity in academic plastic surgery faculty across North America. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoye, G.A. Supporting underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol 2020, 6, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manik, R.; Sadigh, G. Diversity and inclusion in radiology: a necessity for improving the field. Br J Radiol 2021, 94, 20210407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.R.; St. Pierre, F.; Velazquez, A.I.; Ananth, S.; Durani, U.; Anampa-Guzmán, A.; ... Duma, N. The Matilda effect: underrecognition of women in hematology and oncology awards. Oncologist 2021, 26, 779–786. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massaquoi, M.C, USA, M.A.; Reese, M.C, USA, T.R.; Barrett, J.; Nguyen, M.C, USA, D. Perceptions of gender and race equality in leadership and advancement among military family physicians. Mil Med 2021, 186(Supplement_1), 762-766. [CrossRef]

- Warner, E.T.; Carapinha, R.; Weber, G.M.; Hill, E.V.; Reede, J.Y. Faculty Promotion and Attrition: The Importance of Coauthor Network Reach at an Academic Medical Center. J Gen Intern Med 2015, 31, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pololi, L.H.; Jones, S.J. Women Faculty: An Analysis of Their Experiences in Academic Medicine and Their Coping Strategies. Gend Med 2010, 7(5): 438-450. [CrossRef]

- Cropsey, K.L.; Masho, S.W.; Shiang, R.; Sikka, V.; Kornstein, S.G.; Hampton, C.L. Why Do Faculty Leave? Reasons for Attrition of Women and Minority Faculty from a Medical School: Four-Year Results. J Womens Health 2008, 7, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Stevenson, S.; Hueston, W.J.; Mainous, A. G 3rd.; Bazell, P.C.; Ye, X. Female and Underrepresented Minority Faculty in Academic Departments of Family Medicine: Are Women and Minorities Better Off in Family Medicine? Fam Med 2001, 33, 459–465, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11411975/ (accessed on 26/10/2023). [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, J.L.; Garrett, S. Sexism and Racism in the American Health Care Industry: A comparative analysis. Int J Health Serv 1978, 8, 677–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeh, S.L. Women in health care: an examination of earnings. Doctoral dissertation, Wichita State University, Wichita, Kansas, 2012. https://soar.wichita.edu/bitstream/handle/10057/5426/t12045_Umeh.pdf? (accessed on 26/10/2023).

- Platts, A.E.; Tann, J. A changing professional profile: ethnicity and gender issues in pharmacy employment in the United Kingdom. Int J Pharm Pract 1999, 7, 29–39, file:///C:/Users/umaru002/Downloads/A_changing_professional_profile_ethnicit.pdf (accessed on 26/10/2023). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queneau, H. Changes in occupational segregation by gender and race-ethnicity in healthcare: Implications for policy and union practice. Labor Stud J 2006, 31, 71–90, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epdf/10.1177/0160449X0603100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm-Burns, M.A.; Spivey, C.A.; Hagemann, T; Josephson, M. A. Women in leadership and the bewildering glass ceiling. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2017, 74, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, D.P.; Jena, A.B. Trends in Diversity and Representativeness of Health Care Workers in the United States, 2000 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e2117086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassell, K. CPWS Briefing Paper: GPhC Register Analysis 2011. Manchester, UK: The University of Manchester, 2011. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/gphc_register_analysis_2011.pdf (accessed on 01/11/2023).

- Acker, J. From glass ceiling to inequality regimes. Sociol Trav 2009, 51, 199–217, https://journals.openedition.org/sdt/16407 (accessed on 01/11/2023). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Women in Pharmacy Leadership. Canadian Pharmacists Association. https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/WomeninPharmacyReport_final.pdf (accessed on 01/11/2023).

| Authors, year of publication | Article type, Study Design (If applicable) | Study population | Area of focus | Key relevant findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a Rankin et al., 2023 [34] | Research; Cross-sectional, secondary data analysis | The 2020 American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) membership | Gender and racial diversity/ representation (professional membership) | - Moderate increase in gender and racial diversity in professional membership [2002 - 2020) - Underrepresentation of Women, Hispanic/Latinx/Spanish individuals, and individuals reporting a race other than White or Asian |

| a. Chawla et al., 2021 [35] | Research; Cross-sectional, secondary data analysis | Academic faculty with (1) an MD or equivalent, (2) academic ranking, (3) plastic surgery training, and (4) accredited plastic surgeon. | Gender and racial inequity (leadership, scholarly productivity) | - Underrepresentation of women of color in faculty leadership in North America - Less representation of women and underrepresented minorities in leadership in the US compared to Canada |

| a,bOkoye, 2020 [36] | Commentary | Women & Underrepresented minorities in medicine (UIM) in dermatology | Unique experiences and/or challenges | - Underrepresentation of UIM women in academic dermatology - Compared with their majority colleagues, UIM women in academia have higher clinical burden, and lower remuneration |

| b,cVerduzco-Gutierrez et al., 2022 [19] | Commentary | Women of color in academic medicine | Unique experiences and/or challenges women of color. |

- Institutional gender bias as a barrier to progression of women of color to leadership in academic medicine. - Potential strategies and recommendations. |

| cRamas et al., 2021 [20] | Review/ Expert Opinion | Women physicians | Gender inequity (rate of promotion and career advancement) Unique experience and/or challenges (Professional fulfillment and well-being). |

- Three wellness-oriented models are presented to promote the professional fulfillment and well-being of women physicians - Highlights intersectionality (race + gender) and emphasizes the need for more tailored support for URM women physicians (by race/ethnicity and gender identity) |

|

Authors, year of publication |

Article type, Study Design (If applicable) | Study population | Area of focus | Key relevant findings |

| aManik & Sadigh, 2021 [37] | Commentary | Women & Underrepresented minorities in medicine (radiology). | Gender and racial diversity/ representation (education, leadership, research & workforce) |

- Underrepresentation of women of color in leadership in radiology. - Decreasing proportion of women and minorities represented in radiology with increasing rank or job title elevation. |

| aPatel et al., 2021 [38] | Research; Retrospective, observational study | Awards recipients in oncology & hematology | Gender and racial representation (within award recipients) | - Underrepresentation of women and persons from minority groups among award recipients from the seven major international Hematology & Oncology societies in the world |

| bMassaquoi et al., 2021 [39] | Research; cross-sectional survey | Registered attendees of the 2016 Uniformed Services Academy of Family Physicians | Gender and racial inequity (academic medicine and healthcare leadership) Gender and racial representation (attaining early career leadership positions) |

- Inequity in leadership positions and opportunities for advancement between Caucasians and non-Caucasians or males compared with females. |

| aNewman et al., 2019 [31] | Report; assessment and programmatic initiatives | Women & minorities in academic surgery | Gender and racial diversity/ representation (professional fulfillment and career success). |

- Persisting underrepresentation of women and significant absence of under-represented minority faculty in academic surgery. |

| a,cHill et al., 2016 [21] | Research: Mixed Methods; Interviews, Survey (Description of study design; no findings reported) | Women of color junior faculty in academic medical institutions. | Gender and racial diversity/ representation Unique experiences and/or challenges (Institutional, individual, and sociocultural factors that influence the entry, progression, and advancement of women of color in academic medicine) |

- Underrepresentation of women of color among senior biomedical scientists and academic medical faculty as rationale. - Study aims to identify the factors implicated in career progression and leadership attainment. |

| bWarner et al., 2015 [40] | Research; Prospective cohort study | Medical School faculty with rank of Asst. or Assoc. Prof. | Gender and racial inequity (predictors of intra-organizational connections measured by network reach; and their associations with promotion and attrition) | - Minority (African American, Hispanic, and Native American) and women faculty members had lower network reach; higher network reach was associated with likelihood of promotion and less likelihood of leaving the institution. |

| Authors, year of publication | Article type, Study Design (If applicable) | Study population | Area of focus | Key relevant findings |

| bFruge et al., 2011 [33] | Research; cross-sectional survey | American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology (ASPHO) members | Gender & racial inequity Unique experiences and/or challenges (comparative career pathway experience of women and minority ASPHO members). |

- More dissatisfaction reported among Minority and women respondents - Less access to resources and perceived inequity in salary reported among Minority respondents - More dissatisfied with work-life balance and organizational support offered reported among Minority respondents. - Women and minority respondents reported negotiating less successfully. |

| bPololi & Jones, 2012 [41] | Research (Qual); Interviews | Medical faculty representing various disciplines at 4 different career stages (early career, leaders, plateaued, and left academic medicine) | Gender inequity Unique experiences and/or challenges (Marginalization) |

- Women had a sense of "not belonging" in the organization, self-perception of being an “outsider”, feeling isolated and invisible. T - Barriers to advancement, including bias and gender role expectations. - Perception of double disadvantage among faculty from underrepresented minority groups and PhDs |

| a,bCropsey et al., 2008 [42] | Research; survey | Medical school faculty who left the School of Medicine | Unique experiences and/or challenges (women and minority faculty attrition) | - Underrepresentation of women and non-white faculty in higher professional ranks - Women and nonwhite faculty are more likely to be at lower ranks (Instructor or Asst. Prof) - Lower rating of career progression and rate of promotion - Women significantly less likely to evaluate their opportunity for advancement and rate of promotion as good to excellent compared with their male counterparts. |

| bBakken et al., 2006 [32] | Commentary | Physician scientists | Unique experiences and/or challenges (career progression, mentoring, performance) – women and underrepresented minorities | Highlights the unique challenges to career progression for women and underrepresented minorities: - Less than optimal mentoring experience with gender and/or racial discordance - Impact of gender and racial stereotypes on performance |

| a,cWong et al., 2001 [22] | Commentary | Underrepresented minority (URM) physician faculty | Gender and racial representation. (initiative to increase URM faculty recruitment) | Highlights persisting underrepresentation of women of color among medical school faculty and describes efforts to increase representation |

| a,bLewis-Stevenson et al., 2001 [43] | Research; survey | Women and minority physician faculty in departments of family medicine. | Gender and racial inequity (role and academic positions of women and minorities) | - Gender inequity in likelihood of becoming associate or full professors - Underrepresentation of persons from minoritized racial groups - Racial inequity in likelihood of becoming senior faculty |

| bWeaver & Garrett, 1978 [44] | Commentary | Women and URM health professionals | Gender and racial inequity Unique experiences and/or challenges (women and URMs as candidates for professional schools, health care workers/ providers, and service users). |

Highlights - - gender and racial inequity in health professions admissions - discrimination against women and minorities in the health care professions - distinction of sexism vs. racism in the context of the healthcare industry |

| Authors, year of publication | Article type, Study Design (If applicable) | Study population | Area of focus | Key relevant findings |

| b,cClark, 2022 [23] | Commentary | African American (AA) Women in Professional Pharmacy Associations | Unique experiences and/or challenges (Roles in professional pharmacy associations between 1900-1970) | Highlights - Black women's achievements in professional pharmacy associations: addressing injustices and advocating for civil rights contributory to paving the way for inclusion and equity. |

| cParker, 2020 [24] | Doctoral Thesis Research (Qual); Interviews |

African American and African graduate health professional women students | Unique experiences and/or challenges (Black women who had gained entry to or completed graduate education in the health professions) | Emergent themes reflected unique challenges of Black women, including: - Some mentors are inherent/others must be sought out - Experiences and forward-thinking reinforcement matter - Sense of security matters - Student diversity starts with a diverse and supported faculty - Issues both in and outside of school must be addressed - Inclusion must be genuine and meaningful - There is power in being heard |

| bUmeh, 2012 [45] | Doctoral Thesis: Research; secondary data analysis | Women working in health professions and aged 18 - 65; 2008-2010 CPS data | Gender and racial inequity (income earned - non-white women, women with children ≤ 6 years old, immigrant women). | Gender and racial inequity in pay - minority women who work in health care occupations earn less annually than their white counterparts, with the exception of Asians. |

| b,cAbdul-Mutakabbir et al., 2022 [25] | Commentary | Black, Indigenous, and Persons of Color (BIPOC) women in Pharmacy | Gender and racial inequity (historical context) Unique experiences and/or challenges (BIPOC women in pharmacy) |

Highlights historical context of racism and gender inequity. |

| Platts & Tann, 1999 [46] | Research (Mixed Methods); Interviews, Survey | Ethnic minority pharmacists and non-ethnic minority pharmacists (registered pharmacists) | (A comparative analysis) Unique experiences and/or challenges (female and ethnic minority pharmacists – roles, career aims and outcomes) |

Differences in career trajectory and career expectations between Female CPh (Control pharmacist - non-ethnic), and female EPh (Ethnic and Minority pharmacists) - With increasing age, CPh tended to move away from full-time employment towards part-time employment, while EPh either left the profession or became owners - EPh had high levels of ambition for promotion, but their perceptions of likelihood of success were low |

| cHowells et al., 2018 [26] | Research (Qual); Interviews | Women from Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups (BAME) and white women pharmacists | (A comparative analysis) Unique experiences and/or challenges (choices and work patterns) | - Career trajectories and opportunities similar for women part-time workers irrespective of ethnic origin - Normative factors (such as cultural ideals and parental expectations about medical and pharmacy careers) likely critical influences on BAME women’s pharmacy sector preferences |

| Authors, year of publication | Article type, Study Design (If applicable) | Study population | Area of focus | Key relevant findings |

| cRockich-Winston et al., 2023 [27] | Research (Qual); Interviews | Student pharmacists from underrepresented groups (URGs) | *Unique experiences and/or challenges (professional identity formation (PIF)) | - Intersectionality of identities results in perceptions of advantages belonging to certain social categories, while simultaneously being disadvantaged belonging to other social categories. - Intersectionality influences professional identity formation (PIF) for student pharmacists from underrepresented groups (URGs) |

| aQueneau, 2006 [47] | Research; secondary data analysis | The healthcare workforce is represented in 16 occupations, representing ~ 90 percent of total employment in the healthcare workplace. | Gender and racial representation (patterns of occupational segregation by gender and race-ethnicity in healthcare). | - Increased representation of women in higher-paying occupations such as physicians, dentists, and pharmacists; but persisting underrepresentation in such occupations over the period 1983-2002 - Over-representation of women and blacks in low-paying occupations such as nursing aides, orderlies, and attendants. - Underrepresentation of Blacks and Hispanics in better-rewarded occupations |

|

aChisholm-Burns et al., 2012 [48] |

Research (Mixed Methods); survey with open and closed-ended questions. | Female, full-time faculty members of a public non-HBCU college or school of pharmacy | Gender and racial representation (Trends in the numbers of women and underrepresented minority (URM) pharmacy faculty) Unique experiences and/or challenges (factors influencing academic career pursuit and retention) |

- Persisting underrepresentation of URM women pharmacy faculty members at each rank and administrative (ie, dean) position |

| a,bWorld Health Organization, 2019 [9] | Report | The global healthcare workforce | Gender representation (Trends and dynamics in the health workforce) |

- Acknowledges gender inequality in health and social care workforce globally - Highlights gaps in data and research |

| cHahn et al., 2021 [28] | Research; Cross-sectional Survey | Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) students identifying as underrepresented racial minorities (URMs) | Unique experiences and/or challenges (pharmacy career engagement, interest, and confidence URM PharmD students) | - Female Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) students identifying as underrepresented racial minorities (URMs) more likely than males to report having frequent exposure to community pharmacy during school - Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) students identifying as underrepresented racial minorities (URMs) most confident in their ability to obtain a job in community pharmacy (vs hospital and residency |

|

Authors, year of publication |

Article type, Study Design (If applicable) | Study population | Area of focus | Key relevant findings |

| b,cAspinall et al., 2023 [29] | Systematic Review | The nursing profession | *Gender and racial inequity (nursing leadership). | - Gender gap in global health leadership, resulting in a male-dominated yet feminized sector - Ethnic and gender discrimination (unconscious bias and institutional racism) result in poor progression with associated low salary increases |

| bSamra & Hankivsky, 2021 [30] | Commentary | The medical profession | Gender inequity (Impact of patriarchal cultures and colonial histories and values) | Highlights - How patriarchal and colonial histories and values have shaped medical education; constraining women doctors’ career choices and progression internationally - Implicit and explicit biases based on social stereotyping that shape the identification, cultivation, and selection of individuals chosen for programs and internships - How unconscious bias can contribute to systematic underestimation of the capabilities of qualified women and ethnic minority and internationally trained applicants. - The need to recognize and challenge Whiteness norms and patriarchal practices in medicine |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).