Submitted:

01 November 2023

Posted:

02 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

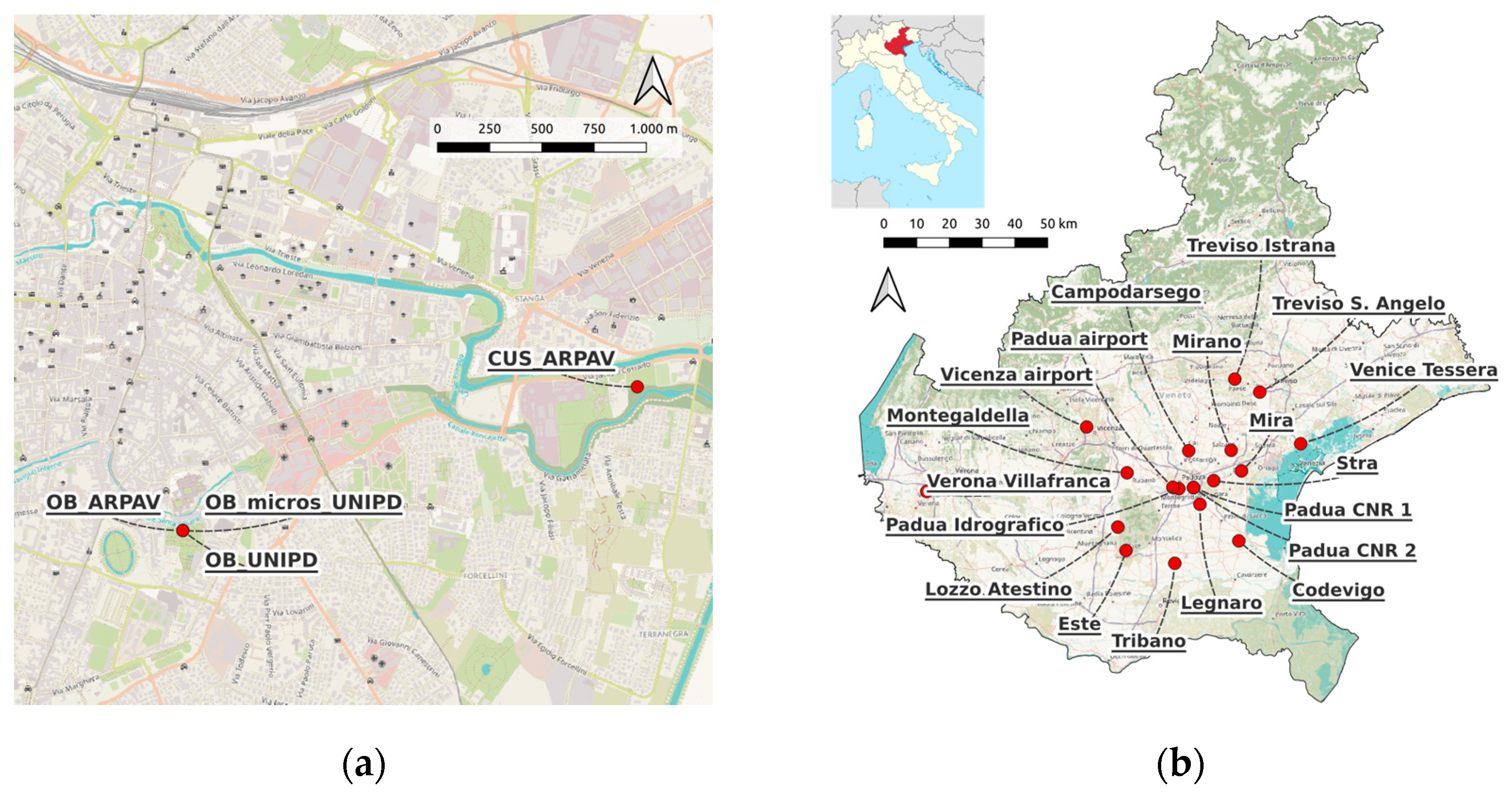

2. Materials and Methods

- January 1980 – December 1993: observations collected at the Botanical Garden by the University of Padua (hereinafter referred to as OB_UNIPD), using a SPIGE mechanical thermohygrograph (measurements were copied from the strip chart into a log) and, from 1984 to 1990, two SPIGE minima and maxima glass thermometers. On 24 October 1990 modern electronic instruments were installed and observations were sampled automatically at unknown intervals [1];

- October 1993 – November 2001: observations sampled every hour (it is unknown whether instantaneous or mean values) collected with a new instrument at the Botanical Garden by the University of Padua (OB_micros_UNIPD);

- May 2000 – 10 March 2019: observations sampled every 15 minutes (instantaneous values) collected with a new instrument at the Botanical Garden, some tens of meters far with respect to the previous sensors, by ARPAV (OB_ARPAV);

- 11 March 2019 up to present: on 11 March 2019 the station was relocated ~2 km east, in the University Sports Center (CUS_ARPAV), where it is located nowadays.

3. Results

3.1. Absolute tests

3.2. Relative tests

| Test | Padua-ERA5 Change-points | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum temperature | Maximum temperature | |

| F-test | Jun 2018 1 | Apr 2000 2 |

| cpt.mean | Feb 1991 2 Jun 2004 2 Mar 2019 2 |

Aug 1980 2 Apr 1983 2 Feb 1993 2 Apr 2000 2 |

| STARS | May 1983 3 Mar 1991 3 Jul 1996 3 Oct 2000 3 Apr 2019 3 |

May 1983 3 Dec 1990 3 Feb 1994 3 May 2000 3 Sep 2003 3 |

- 1 p-value < 0.01.

- 2 The package does not calculate traditional p-values directly related to the changes.

- 3 p-value ≤ 0.01 and cutoff length in the range 12-42 months (i.e., 1-3.5 years).

| Test | Padua-MERIDA Change-points | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum temperature | Maximum temperature | |

| F-test | Nov 2018 1 | Apr 2000 2 |

| cpt.mean | Nov 2018 2 | May 1996 2 Apr 2000 2 Aug 2003 2 |

| STARS | Aug 1996 3 May 2016 3 Apr 2019 3 |

Jun 1996 3 Oct 1998 3 May 2000 3 Sep 2003 3 Jan 2004 3 May 2015 3 |

- 1 p-value < 0.01.

- 2 The package does not calculate traditional p-values directly related to the changes.

- 3 p-value ≤ 0.01 and cutoff length in the range 12-42 months (i.e., 1-3.5 years).

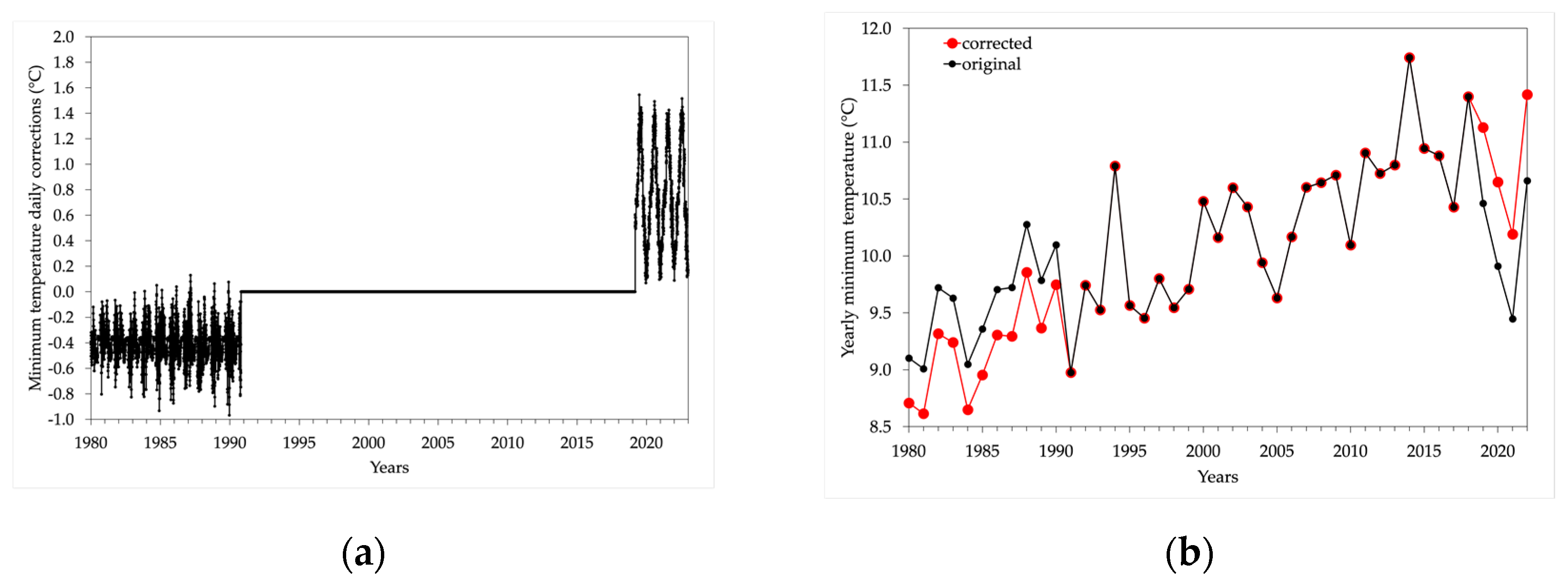

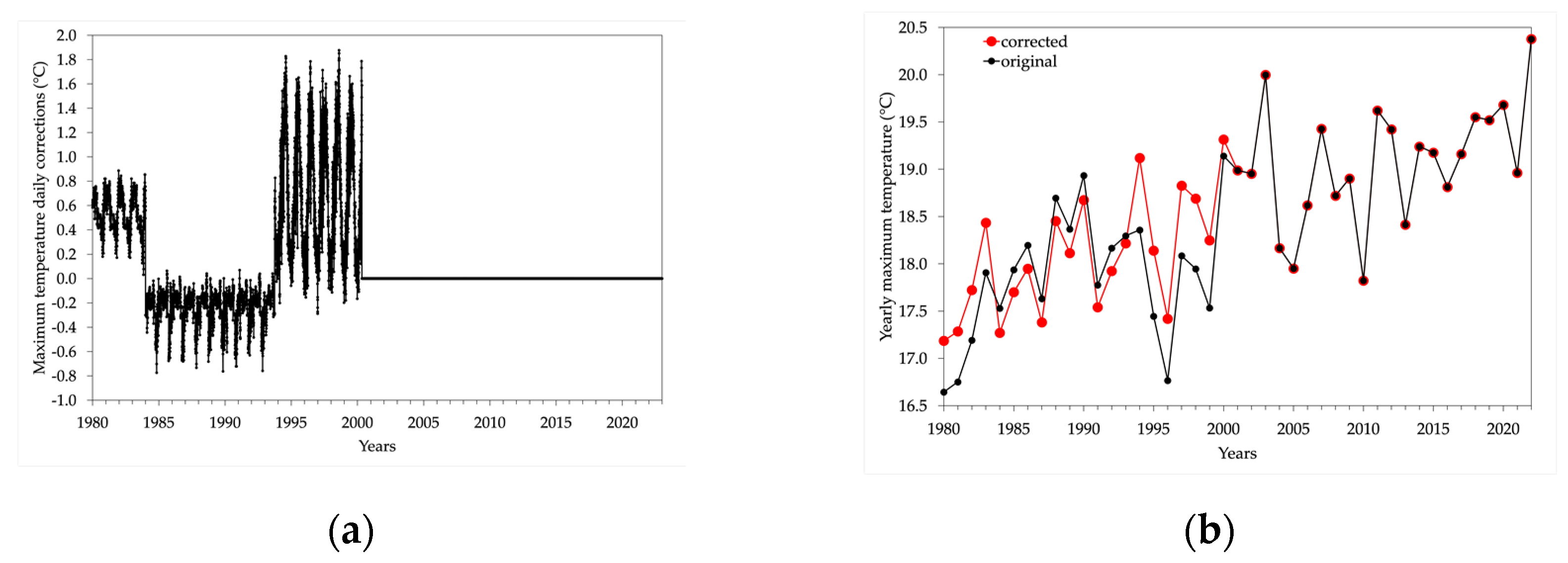

3.3. Homogeneization

| 1980-2022 | OB_UNIPD (1 Jan 1980 – 23 Oct 1990) to OB_ ARPAV | |

|---|---|---|

| Month | Tmin (°C) | r2 |

| January | Y = 0.9768 · X - 0.44 | 0.991 |

| February | Y = 0.9847 · X - 0.26 | 0.957 |

| March | Y = 0.9500 · X - 0.07 | 0.953 |

| April | Y = 0.9640 · X - 0.09 | 0.948 |

| May | Y = 0.9882 · X - 0.34 | 0.943 |

| June | Y = 1.0136 · X - 0.69 | 0.942 |

| July | Y = 0.9961 · X - 0.30 | 0.915 |

| August | Y = 1.0010 · X - 0.38 | 0.926 |

| September | Y = 0.9416 · X + 0.52 | 0.946 |

| October | Y = 0.9443 · X + 0.14 | 0.970 |

| November | Y = 0.9408 · X - 0.11 | 0.977 |

| December | Y = 0.9408 · X - 0.35 | 0.968 |

| 1980-2022 | CUS_ARPAV to OB_ ARPAV | |

|---|---|---|

| Month | Tmin (°C) | r2 |

| January | Y = 0.9701 · X + 0.28 | 0.968 |

| February | Y = 0.9913 · X + 0.39 | 0.921 |

| March | Y = 0.9781 · X + 0.65 | 0.910 |

| April | Y = 0.9915 · X + 0.79 | 0.906 |

| May | Y = 1.0328 · X + 0.43 | 0.904 |

| June | Y = 1.0617 · X + 0.02 | 0.909 |

| July | Y = 1.0380 · X + 0.54 | 0.872 |

| August | Y = 1.0403 · X + 0.52 | 0.884 |

| September | Y = 0.9749 · X + 1.36 | 0.910 |

| October | Y = 0.9735 · X + 0.99 | 0.934 |

| November | Y = 0.9682 · X + 0.70 | 0.954 |

| December | Y = 0.9758 · X + 0.32 | 0.939 |

| 1980-2022 | OB_UNIPD (1 Jan 1980 – 31 Dec 1983) to OB_ ARPAV | |

|---|---|---|

| Month | Tmax (°C) | r2 |

| January | Y = 0.9938 · X + 0.65 | 0.996 |

| February | Y = 0.9803 · X + 0.84 | 0.978 |

| March | Y = 1.0032 · X + 0.70 | 0.980 |

| April | Y = 1.0160 · X + 0.40 | 0.975 |

| May | Y = 1.0117 · X + 0.27 | 0.977 |

| June | Y = 0.9983 · X + 0.46 | 0.975 |

| July | Y = 0.9992 · X + 0.46 | 0.967 |

| August | Y = 1.0147 · X + 0.04 | 0.971 |

| September | Y = 0.9868 · X + 0.69 | 0.969 |

| October | Y = 0.9731 · X + 0.80 | 0.971 |

| November | Y = 0.9529 · X + 0.97 | 0.973 |

| December | Y = 0.9675 · X + 0.89 | 0.959 |

| 1980-2022 | OB_UNIPD (1 Jan 1984 – 30 Sep 1993) to OB_ ARPAV | |

|---|---|---|

| Month | Tmax (°C) | r2 |

| January | Y = 1.0010 · X - 0.31 | 0.992 |

| February | Y = 0.9739 · X - 0.02 | 0.969 |

| March | Y = 0.9979 · X - 0.13 | 0.968 |

| April | Y = 1.0112 · X - 0.34 | 0.966 |

| May | Y = 1.0088 · X - 0.38 | 0.971 |

| June | Y = 1.0044 · X - 0.33 | 0.968 |

| July | Y = 1.0047 · X - 0.27 | 0.960 |

| August | Y = 1.0274 · X - 0.92 | 0.962 |

| September | Y = 0.9983 · X - 0.26 | 0.962 |

| October | Y = 0.9742 · X + 0.01 | 0.964 |

| November | Y = 0.9490 · X + 0.21 | 0.964 |

| December | Y = 0.9611 · X + 0.00 | 0.951 |

| 1980-2022 | OB_micros_UNIPD to OB_ ARPAV | |

|---|---|---|

| Month | Tmax (°C) | r2 |

| January | Y = 1.0401 · X - 0.15 | 0.997 |

| February | Y = 1.0661 · X - 0.29 | 0.988 |

| March | Y = 1.0795 · X - 0.44 | 0.988 |

| April | Y = 1.0900 · X - 0.72 | 0.983 |

| May | Y = 1.0831 · X - 0.80 | 0.986 |

| June | Y = 1.0748 · X - 0.77 | 0.985 |

| July | Y = 1.0738 · X - 0.77 | 0.975 |

| August | Y = 1.0836 · X - 1.02 | 0.977 |

| September | Y = 1.0703 · X - 0.71 | 0.980 |

| October | Y = 1.0546 · X - 0.48 | 0.982 |

| November | Y = 1.0238 · X - 0.05 | 0.983 |

| December | Y = 1.0410 · X - 0.17 | 0.972 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Camuffo, D. History of the Long Series of Daily Air Temperature in Padova (1725–1998). Climatic Change 2002, 53, 7–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D.; Bertolin, C. Recovery of the early period of long instrumental time series of air temperature in Padua, Italy (1716–2007). Phys Chem Earth, Parts A/B/C, Elsevier BV, 2012, Vol. 40-41, pp. 23-31. [CrossRef]

- Yozgatligil, C.;Yazici, C. Comparison of homogeneity tests for temperature using a simulation study. International Journal of Climatology, Wiley, 2015, Vol. 36(1), pp. 62-81. [CrossRef]

- Militino, A.; Moradi, M.; Ugarte, M. D. On the Performances of Trend and Change-Point Detection Methods for Remote Sensing Data Remote Sensing, MDPI AG, 2020, Vol. 12(6), pp. 1008. [CrossRef]

- Overland, J. E.; Percival, D. B.; Mofjel H. O. Regime shifts and red noise in the North Pacific. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, Elsevier BV, 2006, Vol. 53(4), pp. 582-588. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, T. C.; Easterling, D. R.; Karl, T. R.; Groisman, P.; Nicholls, N.; Plummer, N.; Torok, S.; Auer, I.; Böhm, R.; Gullett, D.; Vincent, L.; Heino, R.; Tuomenvirta, H.; Mestre, O.; Szentimrey, T.; Salinger, J.; Førland, E. J.; Hanssen-Bauer, I.; Alexandersson, H.; Jones, P. E.; Parker, D. Homogeneity adjustments of in situ atmospheric climate data: a review. Int J Climatol, 1998, Vol. 18(13), pp. 1493-1517. [CrossRef]

- Cos J., Doblas-Reyes F., Jury M., Marcos R., Bretonnière P. A., Samsó M. The Mediterranean climate change hotspot in the CMIP5 and CMIP6 projections, Earth Syst. Dynam., 2022, 13, 321–340. [CrossRef]

- Alexandersson, H. A homogeneity test applied to precipitation data. Journal of Climatology, Wiley, 1986, Vol. 6(6), pp. 661-675. [CrossRef]

- Buishand, T. Some methods for testing the homogeneity of rainfall records. Hydr., Elsevier BV, 1982, Vol. 58(1-2), pp. 11-27. -27. [CrossRef]

- Pettitt, A. N.; A Non-Parametric Approach to the Change-Point Problem. Applied Statistics, JSTOR, 1979, Vol. 28(2), pp. 126. [CrossRef]

- Chow, G. C. Tests of Equality Between Sets of Coefficients in Two Linear Regressions. Econometrica, JSTOR, 1960, Vol. 28(3), pp. 591. [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, S. N. A sequential algorithm for testing climate regime shifts. Geophysical Research Letters, American Geophysical Union (AGU), 2004, Vol. 31(9). [CrossRef]

- Changepoint, https://github.com/rkillick/changepoint/ (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- von Neumann, J. Distribution of the Ratio of the Mean Square Successive Difference to the Variance. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 1941, Vol. 12(4), pp. 367-395. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, D. M. Testing a Sequence of Observations for a Shift in Location. Journal of the American Statistical Association, Informa UK Limited, 1977, Vol. 72(357), pp. 180-186. [CrossRef]

- Wambui G. D., Waititu G. A., Wanjoya A. The Power of the Pruned Exact Linear Time(PELT) Test in Multiple Changepoint Detection, Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2015, Vol. 4(6), pp. 581-586. [CrossRef]

- Mann, H. B. Nonparametric Tests Against Trend. Econometrica, JSTOR, 1945, Vol. 13(3), pp. 245. [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods, 4th edition; Charles Griffin: London, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, R.O. Statistical Methods for Environmental Pollution Monitoring; Wiley: NY, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Biavati, G., Horányi, A., Sabater, J. M., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Rozum, I., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Dee, D., and Thépaut, J.-N. ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1979 to present, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Velikou K., Lazoglou G., Tolika K., Anagnostopoulou C. Reliability of the ERA5 in Replicating Mean and Extreme Temperatures across Europe, Water 2022, 14, 543. [CrossRef]

- Bonanno R., Lacavalla M., Sperati S. A new high-resolution Meteorological Reanalysis Italian Dataset: MERIDA, Q J R Meteorol Soc. 2019, 145:1756–1779. [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, J. A. User’s guide of the climatol R Package. Unpublished, 2023.

- Caloiero, T., Filice, E., Coscarelli, R., Pellicone, G. A Homogeneous Dataset for Rainfall Trend Analysis in the Calabria Region (Southern Italy), Water, MDPI AG, 2020, Vol. 12(9), pp. 2541. [CrossRef]

- Cocheo, C., Camuffo, D. Corrections of Systematic Errors and Data Homogenisation in the Daily Temperature Padova Series (1725–1998). Climatic Change, 2002, 53, 77–100. [CrossRef]

| Station shortname | Longitude | Latitude | Elevation | Data availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OB_UNIPD | 11.8805 | 45.3993 | 12 m | 1 Jan 1980 – 31 Dec 1993 (99.6%) |

| OB_micros_UNIPD | 11.8805 | 45.3993 | 12 m | 1 Oct 1993 – 30 Nov 2001 (91.0%) |

| OB_ARPAV | 11.8805 | 45.3993 | 12 m | 1 May 2000 – 10 Mar 2019 (100.0%) |

| CUS_ARPAV | 11.9085 | 45.4050 | 12 m | 11 Mar 2019 – 31 Dec 2022 (99.9%) |

| R package | Test | Function | Abs./Rel. |

|---|---|---|---|

| trend 1.1.5 | SNH | snh.test | Abs. |

| Pettitt | pettitt.test | Abs. | |

| Buishand U Buishand Range |

bu.test br.test |

Abs. Abs. |

|

| DescTools 0.99.47 | Von Neumann ratio | VonNeumannTest | Abs. |

| strucchange 1.5-3 | F-test | Fstats | Both |

| changepoint 2.2.4 | cpt.mean | cpt.mean | Both |

| rshift 2.2.2 | STARS | Rodionov | Both |

| climatol 4.0.0 | Climatol | homogen | Rel. |

| Station shortname | Longitude | Latitude | Elevation | Data Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Padua Idrografico | 11.8716 | 45.3912 | 13 m | 1 Jan 1986 – 31 Dec 1996 (50.9%) |

| Padua airport | 11.8483 | 45.3953 | 13 m | 1 Jan 1980 – 29 Dec 1990 (98.8%) |

| Padua CNR 1 | 11.9290 | 45.3931 | 10 m | 10 Apr 1984 – 31 Dec 1986 (51.4%) |

| Padua CNR 2 | 11.9290 | 45.3931 | 10 m | 29 Oct 1993 – 29 Dec 2008 (78.3%) |

| Codevigo | 12.1000 | 45.2430 | 0 m | 18 Feb 1992 – 31 Dec 2022 (99.6%) |

| Tribano | 11.8490 | 45.1860 | 4 m | 1 Jan 1996 – 31 Dec 2022 (100.0%) |

| Mira | 12.1177 | 45.4353 | 5 m | 5 May 1992 – 31 Dec 2022 (99.9%) |

| Campodarsego | 11.9137 | 45.4948 | 15 m | 1 Jan 1993 – 31 Dec 2022 (100.0%) |

| Legnaro | 11.9524 | 45.3467 | 10 m | 17 Jul 1991 – 31 Dec 2022 (99.3%) |

| Este | 11.6606 | 45.2244 | 12 m | 1 Feb 1980 – 31 Dec 1999 (78.4%) |

| Lozzo Atestino | 11.6307 | 45.2893 | 15 m | 1 Jan 1985 – 31 Dec 1996 (79.3%) |

| Stra | 12.0084 | 45.4107 | 9 m | 28 Jan 1985 – 31 Dec 2004 (88.1%) |

| Mirano | 12.0797 | 45.4930 | 10 m | 1 Jan 1988 – 30 Nov 2004 (100.0%) |

| Montegaldella | 11.6710 | 45.4383 | 22 m | 1 Apr 1993 – 31 Dec 2004 (98.6%) |

| Treviso Istrana | 12.1013 | 45.6887 | 41 m | 1 Jan 1980 – 31 Dec 2022 (98.6%) |

| Treviso S. Angelo | 12.1978 | 45.6508 | 17 m | 1 Jan 1980 – 31 Dec 2022 (97.0%) |

| Venice Tessera | 12.3519 | 45.5053 | 2 m | 1 Jan 1980 – 31 Dec 2022 (99.8%) |

| Vicenza airport | 11.5167 | 45.5667 | 39 m | 1 Jan 1980 – 29 Feb 2008 (98.1%) |

| Verona Villafranca | 10.8881 | 45.3964 | 72 m | 1 Jan 1980 – 31 Dec 2022 (98.8%) |

| Test | Change-points | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum temperature | Maximum temperature | |

| SNH1 | Feb 2000 | Mar 2000 |

| Pettitt1 | Feb 2000 | Mar 2000 |

| Buishand U1 | Feb 2000 | Mar 2000 |

| Buishand Range1 | Feb 2000 | Mar 2000 |

| Von Neumann ratio1 | yes | yes |

| F-test1 | Feb 2000 | Mar 2000 |

| cpt.mean2 | Mar 2000 | Apr 1982 Mar 2000 Apr 2003 Aug 2003 Feb 2011 |

| STARS3 | Sep 1987 Jul 2013 Mar 2020 |

Jul 1985 Apr 2000 Jan 2004 Sep 2006 |

- 1 p-value < 0.01.

- 2 The package does not calculate traditional p-values directly related to the changes.

- 3 p-value ≤ 0.01 and cutoff length in the range 12-42 (i.e., 1-3.5 years).

| Datasets over 1993-2022 | Minimum temperature | Maximum temperature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c_Pearson | RMSE (°C) | c_Pearson | RMSE (°C) | |

| ERA5 | 0.980 (0.866) | 2.25 | 0.986 (0.904) | 1.48 |

| MERIDA | 0.987 (0.912) | 1.17 | 0.990 (0.926) | 1.28 |

| Campodarsego | 0.982 (0.911) | 2.47 | 0.995 (0.965) | 1.01 |

| Legnaro | 0.986 (0.923) | 1.83 | 0.994 (0.962) | 0.93 |

| Codevigo | 0.983 (0.904) | 1.76 | 0.991 (0.936) | 1.22 |

| Mira | 0.983 (0.915) | 2.25 | 0.992 (0.953) | 1.08 |

| Tribano 1 | 0.985 (0.912) | 1.88 | 0.992 (0.946) | 1.23 |

| Treviso Istrana | 0.983 (0.898) | 1.86 | 0.991 (0.936) | 1.37 |

| Treviso S. Angelo | 0.987 (0.919) | 1.56 | 0.991 (0.941) | 1.26 |

| Venice Tessera | 0.990 (0.929) | 1.22 | 0.986 (0.908) | 1.62 |

| Verona Villafranca | 0.982 (0.884) | 2.06 | 0.987 (0.908) | 1.50 |

| Change-points | ||

|---|---|---|

| Timing | Cause | |

| Minimum temperature | 24 Oct 1990 11 Mar 2019 |

Instrument change Location change |

| Maximum temperature | 1 Jan 1984 1 Oct 1993 1 May 2000 |

Instrument change Instrument change Instrument and location change |

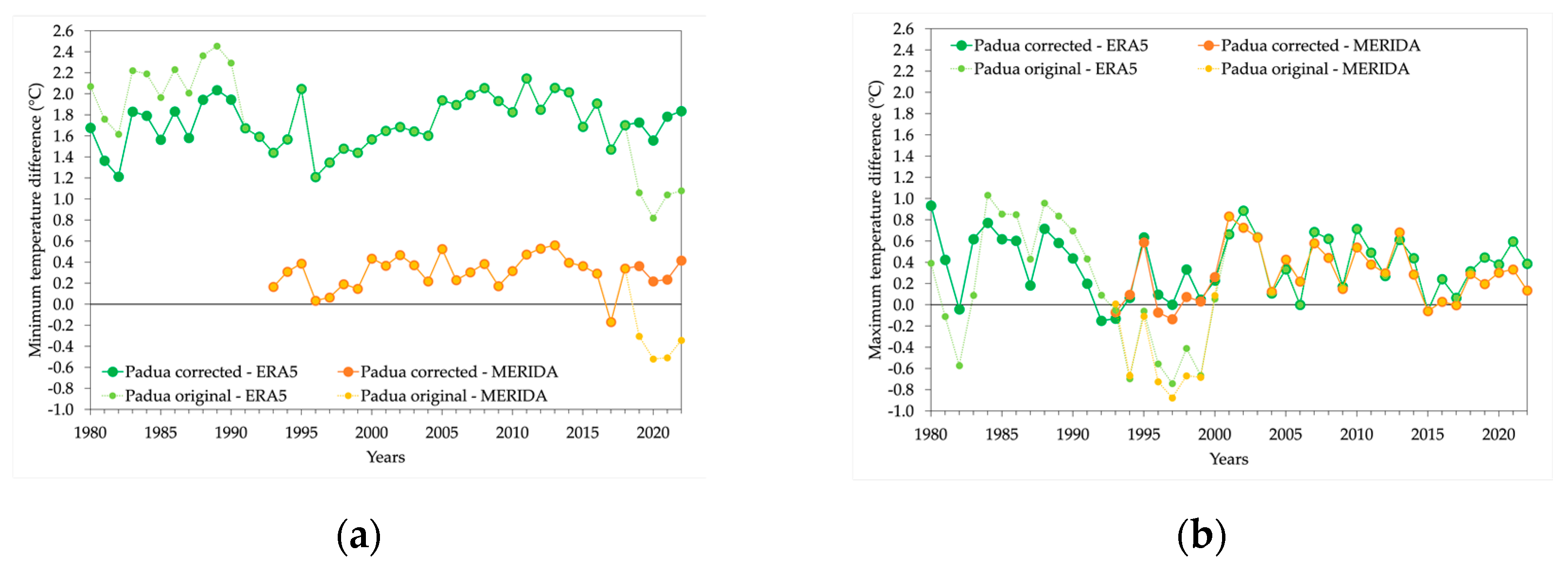

| 1993-2022 | Slopes (°C/decade) | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum temperature | Maximum temperature | |

| Padua original | +0.31 ± 0.08 | +0.61 ± 0.09 |

| Padua corrected | +0.48 ± 0.08 | +0.40 ± 0.09 |

| MERIDA | +0.46 ± 0.07 | +0.39 ± 0.09 |

| 1980-2022 | Slopes (°C/decade) | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum temperature | Maximum temperature | |

| Padua original | +0.35 ± 0.05 | +0.52 ± 0.06 |

| Padua corrected | +0.54 ± 0.05 | +0.48 ± 0.05 |

| ERA5 | +0.49 ± 0.05 | +0.50 ± 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).