Submitted:

30 October 2023

Posted:

31 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

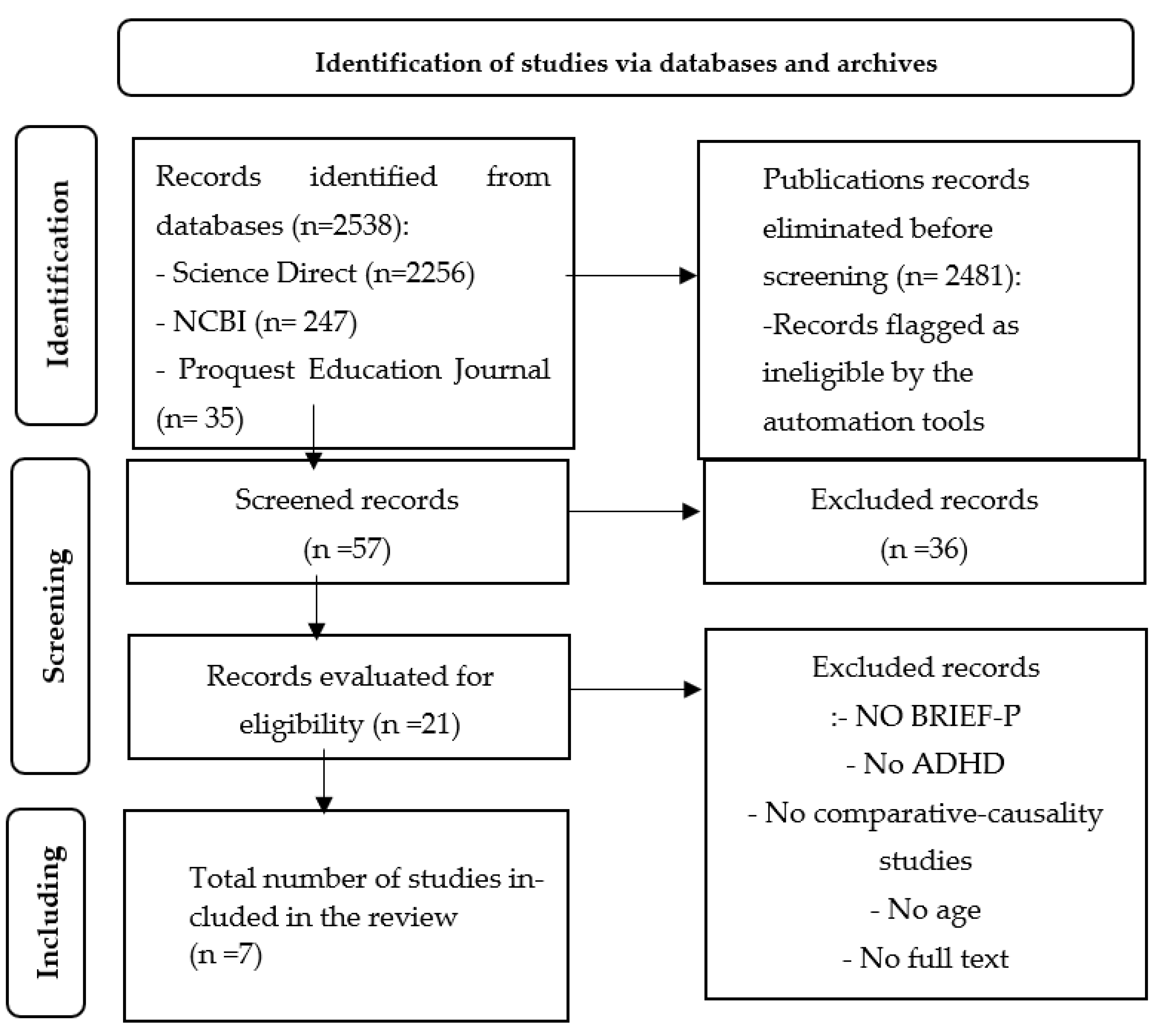

2.1. Search strategy

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| (a) Participants: persons with symptoms compatible with ADHD obtained from the application of standardized tests | (a) Participants: not diagnosed with ADHD |

| (b) Cognitive age that allows the application of BRIEF-P | (b) Cognitive age: does not allow application of BRIEF-P |

| (c) Cognitive competence: obtained through the application of standardized tests | (c) Cognitive competence: not available |

| (d) Executive dimensions: single construct or basic dimensions (flexibility, inhibition and working memory). | |

| (e) Assessment instruments: standardized for assessing executive functions: hetero- and/or self-report | (d) Assessment instruments: non-standardized |

| (f) Type of studies: empirical | (e) Type of studies: case study and review |

| (g) type of design: non-experimental, comparative-causal (group with ADHD-compatible symptoms versus group with typical development) | (f) type of design: non-comparative-causal |

| (h) Language: English and Spanish | (g) Language: other |

| (i) Other characteristics: full text | (h) Other characteristics: abstract, full text not available |

3. Results

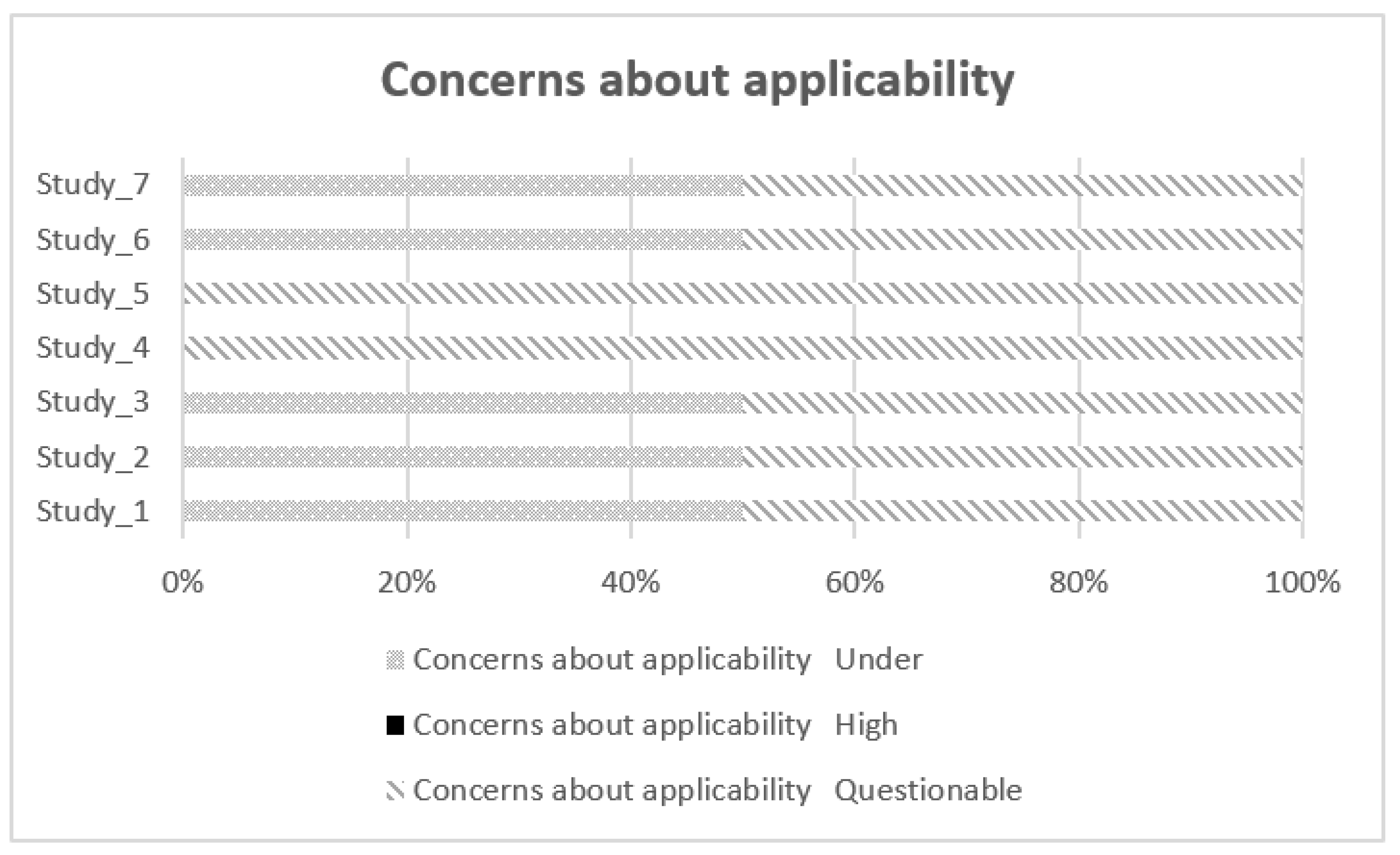

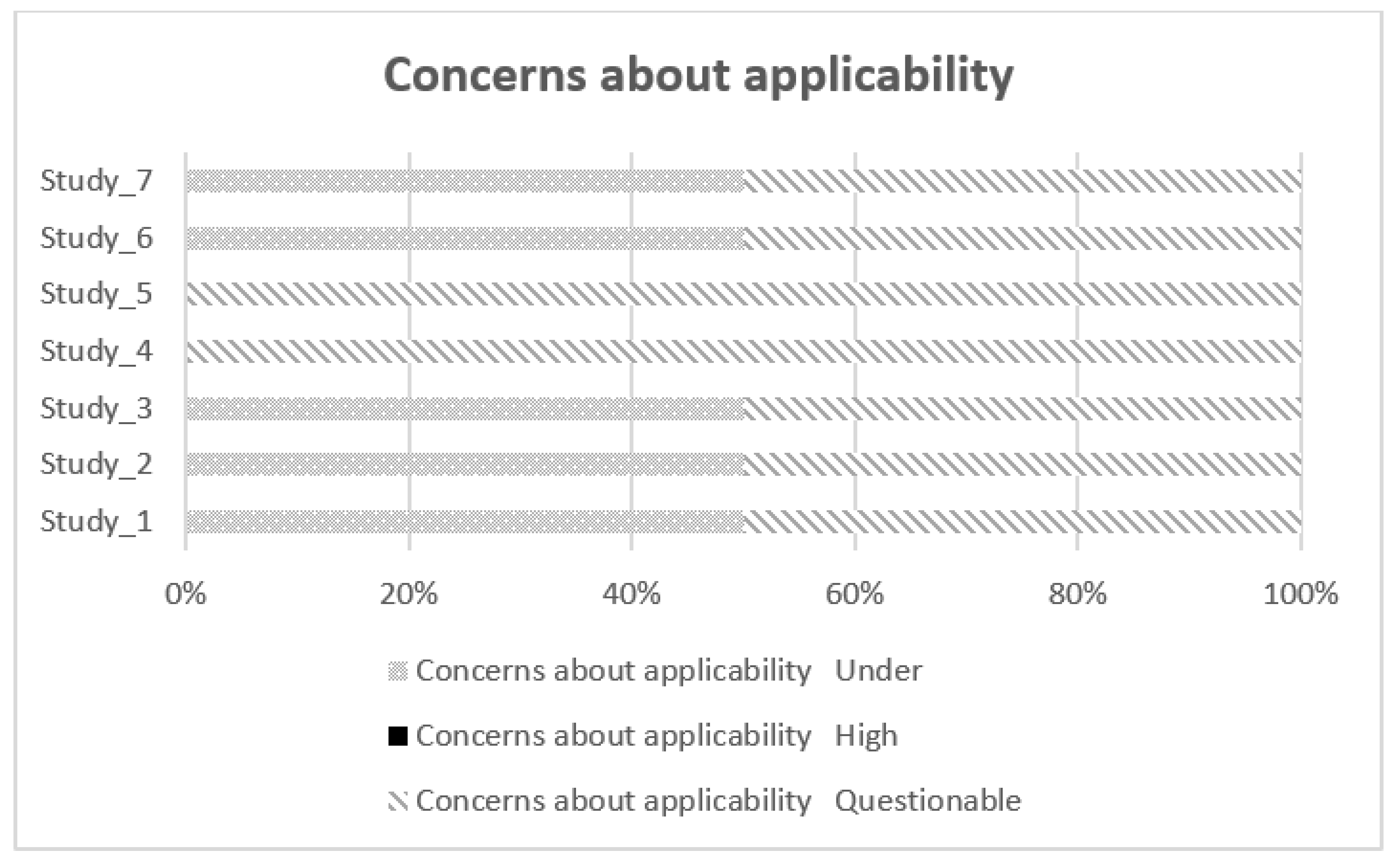

3.1. Risk of bias

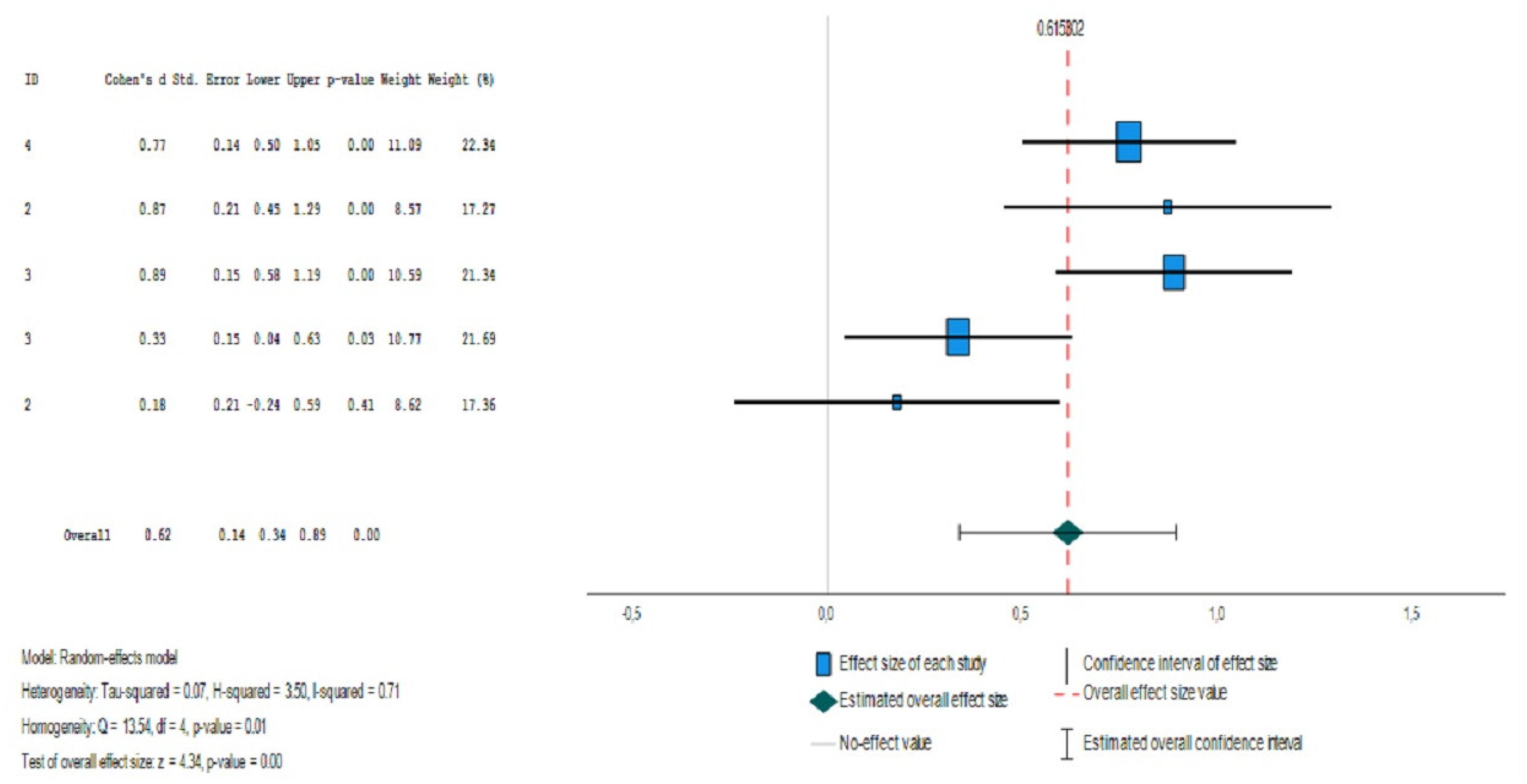

3.2. Floor effect and ceiling effect

3.2.1. Floor effect

3.2.2. Ceiling effect

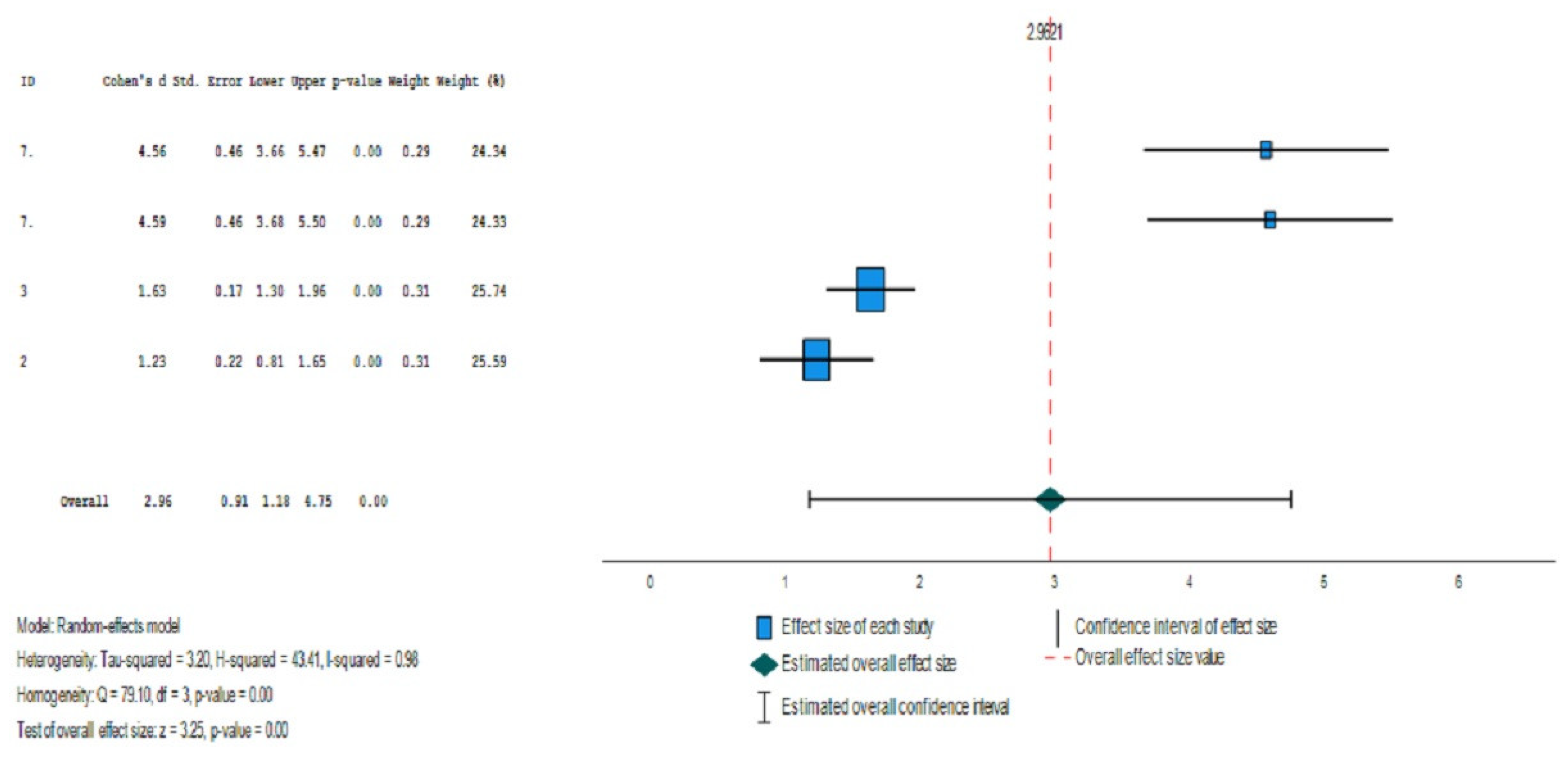

| Study | Author | BRIEF_P | ADH | Typical Development | |||||

| N | M | STD | N | M | STD | ||||

| 7 | Çak et al. (2017). | Emergent Metacognition (Working Memory + Planning/Organization) | 21 | 100.46 | 11.61 | 52 | 54.09 | 9.54 | |

| 7 | Çak et al. (2017). | Global Executive Functioning | 21 | 103.05 | 10.07 | 52 | 54.39 | 10.79 | |

| 3 | Zhang, et al. (2018). | Global Executive Functioning | 163 | 104.59 | 16.26 | 63 | 79.54 | 12.75 | |

| 2 | Ezpeleta, L., & Granero, R. (2015) | Global Executive Functioning | 23 | 107.27 | 21.81 | 538 | 83.54 | 19.19 | |

| N: Sample size; M: Mean; STD: Standard Desviation; | |||||||||

| Effect size | Standard error | Z | Sig. (bilateral) | Confidence interval 95% | Prediction interval 95%a | ||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Global | 2.962 | .9117 | 3.249 | .001 | 1.175 | 4.749 | -5.679 | 11.603 | |

| a. Based on t-distribution. | |||||||||

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sayal, K., Prasad, V., Daley, D., Ford, T., & Coghill, D., "ADHD in children and young people: prevalence, care pathways, and service provision," The Lancet Psychiatry, 2018, Volume 5(2), pp. 175-186. [CrossRef]

- Lange, K., Reichl, S., Lange, K., Tucha, L., & Tucha, O., "The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder," ASHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 2010, Volume 2, pp. 241-255. [CrossRef]

- [3] American Psychiatric Association (APA), Diagnóstic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th ed., Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA), Diagnóstic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th T R Edition, Arlington: American Psychiatric Association, 2022.

- Faraone, S., Perlis, R. H., Doyle, A. E., Smoller, J. W., Goralnick, J., Holmgren, M. A., & Sklar, P., "Molecular Genetics of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder," Biological Psychiatry, 2005, Volume 57(11), pp. 1313-1323. [CrossRef]

- Millichap, J., "Etiologic Classification of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder," Pediatrics, 2008, Volume 121(2), pp. e358-e365. [CrossRef]

- Antshel, K., Hier, B. O., & Barkley, R., "Executive Functioning Theory and ADHD," in Handbook of Executive Funtioning, New York, Springer, 2014, pp. 107-120. [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R. A., Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment, The Guilford Press, 2006.

- Doyle, A. E., "Executive functions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorde," Journal od Clinical Psychiatry, 2006, Volume 67, Suppl 8, pp. 21-26, Retrieved from https://www.psychiatrist.com/pcc/neurodevelopmental/adhd/executive-functions-attention-deficit-hyperactivity/.

- Bauermeister, J., Shrout, P., Ramírez, R., Bravo, M., Alegría, M., Martínez-Taboas, A., Chávez, L., Rubio-Stipec, M. and García P. R. J., "ADHD correlates, comorbidity, and impairment in community and treated samples of children and adolescents.," Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 2007, Volume 35(6), pp.883-898. [CrossRef]

- Gnanavel, S., Sharma, P., Kaushal, P., & Hussain, S., "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbidity: A review of literature," World Journal of Clinical Cases, 2019, Volume 7(17), pp. 2420-2426. [CrossRef]

- Marqués-Cabezas, P., Segura-Rodríguez, A., García-Barriuso, P., Gallardo-Borge, L., Mateos-Sexmero, M., Blanco, J., Queipo de LLano De la Viuda, M., Perez-Carranza, M., Aparicio-Parras, A., Espina-Barrio, J. and Rodriguez-Campos, A., "Comorbility symptoms in AHDH adult patients," European Psychiatry, 2022, Volume 65(S1), pp. S466-S466. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. E., "Executive Functions and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Implications of two conflicting views," International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 2006, Volume53(1), pp. 35-46. [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, X.F., Sonuga-Barke,E. J.S., Milham, M. P., & Tannock, R., "Characterizing cognition in ADHD: beyond executive dysfunction," Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2006, Volume 10(3), pp. 117-123. [CrossRef]

- Lambek, R., Tannock, R., Dalsgaard, S., Trillingsgaard, A., Damm, D., & Thomsen, P., "Validating neuropsychological subtypes of ADHD: how do children with and without an executive function deficit differ?," The Journal of Child Psychological and Psychiatry, 2010, Volume 51(8), pp. 895-904. [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D., "The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis," Cognitive Psychology, 2000, Volume 41(1), pp. 49-100. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Shuai, L., Zhang, J., Wang, Y., Lu, T., Tan, X., Pan, J. and Shen, L., "Neuropsychological Profile Related with Executive Function of Chinese Preschoolers with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Neuropsychological Measures and Behavior Rating Scale of Executive Function-Preschool Version.," Chinese Medical Journal, 2018, Volume 131(6), pp. 648-656. [CrossRef]

- Babb, K. A., Levine, L. J., & Arseneault, J. M., "Shifting gears: Coping flexibility in children with and without ADHD.," International Journal of Behavioral Development, 2010, Volume 34(1), pp. 10-23. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, I., Hoyniak, C., McQuillan, M., Bates, J., & Staples, A., "Measuring the development of inhibitory control: The challenge of heterotypic continuity.," Developmental Review, 2016, Volume 40, pp. 25-71. [CrossRef]

- Bausela-Herreras, E., "Development of Executive Function at the Preschool Age," in Handbook of Research on Neurocognitive Development of Excecutive Funtions and Implications for Intervention, IGI Glogal, 2022, pp. 1-22.

- Zelazo, P., Müller, U., Frye, D., Marcovitch, S., Argitis, G., Boseovski, J., Chiang, J., Hongwanishkul, D., Schuster B. and Sutherland, A., "The development of executive function in early childhood.," Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 2003, Volume 68(3), pp. vii-137. [CrossRef]

- Lensing, N., & Elsner, B., "Development of hot and cool executive functions in middle childhood: Three-year growth curves of decision making and working memory updating," Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 2018, Volume 173, pp. 187-204. [CrossRef]

- Homer, B. D., Plass, J. L., Rose, M. C., MacNamara, A. P., Pawar, S., & Ober, T. M., "Activating adolescents’ “hot” executive functions in a digital game to train cognitive skills: The effects of age and prior abilities," Cognitive Development, 2019, Volume 49, pp. 20-32. [CrossRef]

- Prencipe, A., Kesek, A., Cohen, J., L. C., Lewis, M., & Zelazo, P., "Development of hot and cool executive function during the transition to adolescence," Jorunal of Experimental Child Psychology, 2011, Volume 108(3), pp. 621-631. [CrossRef]

- Rastikerdar, N., N. V., Sammaknejad, N., & Fathabadi, J., "Developmental trajectory of hot and cold executive functions in children with and without attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)," Research in Developmental Disabilities, 2023, Volume 137, Art. 104514. [CrossRef]

- Shakehnia, F., Amiri, S., & Ghamarani, A., "he comparison of cool and hot executive functions profiles in children with ADHD symptoms and normal children," Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 2021, Volume 55, pp.102483. [CrossRef]

- Berger, I., Slobodin, O., Aboud, M., Melamed, J., & Cassuto, H., "Maturational delay in ADHD: evidence from CPT," Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 2013, Volume 7, pp.1-11. [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, K., Bunte, T., Wiebe, S., Espy, K., Deković, M., & Matthys, W., "Executive function deficits in preschool children with ADHD and DBD," Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 2012, Volume 53, pp.111-119. [CrossRef]

- Roshani, F., Piri, R., & Malek A, M. T., "Comparison of cognitive flexibility, appropriate risk-taking and reaction time in individuals with and without adult ADHD.," Psychiatry Research, 2020 Volume 284, Art. 112494. [CrossRef]

- Karalunas, S. L., & Huang-Pollock, C. L., "Examining relationships between executive functioning and delay aversion in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.," Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 2011, Volume 40(6), pp. 837–847. [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Téllez, G., Romero-Romero, H., Rivera-García, L., Prieto-Corona, B., Bernal-Hernández, J., Marosi-Holczberger, Guerrero-Juárez, E. V., Rodríguez-Camacho, M. and Silva-Pereyra, J. F., "Cognitive and executive functions in ADHD.," Actas Españolas de Psiquiatria, 2012, Volume 40(6), pp. 293-298.

- Zelazo, P., & Carlson, S., "Hot and Cool Executive Function in Childhood and Adolescence: Development and Plasticity," Child Development Perspectives, 2012, Volume 6(4), pp. 354-360. [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R. "Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD," Psychological Bulletin, 1997, Volume 121(1), pp. 65-94. [CrossRef]

- Hobson, C., Scott, S., & Rubia, K., "Investigation of cool and hot executive function in ODD/CD independently of ADHD," The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 2011, Volume 52(10), pp.1035-1043. [CrossRef]

- Nejati, V., "Reading mind from the eyes in individuals with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A meta-analysis," Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 2022, Volume 22(10), pp. 889-896. [CrossRef]

- Nigg, J., "Is ADHD a disinhibitory disorder?," Psychological Bulletin, 2001, Volume 127(5), pp. 571-598. [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R. "Advances in the diagnosis and subtyping of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: what may lie ahead for DSM-V," Revista de Neurologia, 2009, Volume 48, suppl 2, pp. S101-106. [CrossRef]

- Servera, M., "Modelo de autorregulación de Barkley aplicado al trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad: una revisión," Revista de Neurologia, 2005, Volume 40(6), pp. 358-368. [CrossRef]

- Kofler, M., Singh, L., Soto, E., Chan, E., Miller, C., Harmon, S., & Spiegel, J., "Working memory and short-term memory deficits in ADHD: A bifactor modeling approach.," Neuropsychology, 2020, Volume 34(6), pp. 686-698. [CrossRef]

- Kasper, L., Alderson, R., & Hudec, K., "Moderators of working memory deficits in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a meta-analytic review.," Clinical Psychology Review, 2012, Volume 32(7), pp. 605-617. [CrossRef]

- Nejati, V., Derakhshan, Z., & Mohtasham, A., "The effect of comprehensive working memory training on executive functions and behavioral symptoms in children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)," Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 2023, Volume 81, Art.103469. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B., Chan, R., Gracia, N., Cao, X., Zou, X., Jing, J., Mai, J., Li, J. and Shum, D., "Cool and hot executive functions in medication-naive attention deficit hyperactivity disorder children," Psychological Medicine, 2011, Volume 41(12), pp. 2593-2602. [CrossRef]

- Cañas, J., Quesada, J., Antolí, A., & Fajardo, I., "Cognitive flexibility and adaptability to environmental changes in dynamic complex problem-solving tasks.," Ergonomics, 2003, Volume 46(5), pp. 482-501. [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, M., Hijlkema, M., & Kalverboer, A., "Physiotherapy for clumsy children: an evaluation study," Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 1994, Volume 36(2), pp. 143-155. [CrossRef]

- Wixted, E., Sue, I., Dube, S., & Potter, A., Cognitive Flexibility and Academic Performance in College Students with ADHD: An fMRI Study., UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 126, 2016.Reetreived from https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1144&context=hcoltheses.

- Chan, R. C., Shum, D., Toulopoulou, T., & Chen, E. Y., "Assessment of executive functions: Review of instruments and identification of critical issues," Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 2008, Volume 23, pp. 201-216. [CrossRef]

- Donders, J., "The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function: Introduction," Child Neuropsychology, 2002 Volume 8(4), pp. 229-230. [CrossRef]

- Gioia, G., Kenworthy, L., & Isquith, P., "Executive Function in the Real World: BRIEF lessons from Mark Ylvisaker," Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 2010, Volume 25(6), pp. 433-439. [CrossRef]

- Henry, L. A., & Bettenay, C., "The assessment of executive functioning in children," Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 2010, Volume 15(2), pp. 110-119. [CrossRef]

- Lezak, M., Howieson, D., Bigler, E., & Tranel, D., Neuropsychological assessment, New York : Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Miyake, A., Emerson, M. J., & Friedman, N. P., "Assessment of executive functions in clinical settings: Problemas and recomendations," Seminars in speech and language, 2000, Volume 21(2), pp. 169-183. [CrossRef]

- Toplak, M., Bucciarelli, S., Jain, U., & Tannock, R., "Executive functions: performance-based measures and the behavior rating inventory of executive function (BRIEF) in adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).," Child Neuropsychology, 2009, Volume 15(1), pp. 53-72. [CrossRef]

- Verdejo-García, A., & Bechara, A., "Neuropsychology of the executive Funtions," Psicothema, 2010, Volume 22(2), pp. 227-235. Retreived from https://www.psicothema.com/pdf/3720.pdf.

- Wild, K., & Musser, E. D., "The Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery in the Assessment of Executive Functioning," in Handbook of Executive Funtioning, New York, Springer, 2014, pp. 171-190. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, J., Mungas, D., Possin, K., Rankin, K., Boxer, A., Rosen, H., Bostrom, A., Sinha, L., Berhel, A. and Widmeyer, M., "NIH EXAMINER: conceptualization and development of an executive function battery," Journal of International Neuropsychological Society, 2014, Volume 20, pp. 11-19. [CrossRef]

- Naglieri, J., & Das, J., Cognitive Assessment System, Itasca:: Riverside Publishing Company, 1997.

- Naglieri, J., Das, J., & Goldstein, S., Cognitive Assessment System2, Austin: ProEd, 2013.

- Delis, D., Kaplan, E., & Kramer, J., Delis Kaplan (D-KEFS) technical manual, San Antonio, TX: NCS Pearson Inc., 2001.

- Naglieri, J. A., & Goldstein, S., Comprenhensive Executive Functioning Index, Toronto: Multi Health Systems, 2013.

- Gioia, G., Isquith, P., Guy, S., & Kenworthy, L., BRIEF: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function professional manual, Lutz, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources., 2000.

- Guy, S. C., Isquith, P. K., & Gioia, G. A., Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function—Self Report Version, Lutz, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, 2004.

- Roth, R. M., Isquith, P. K., & Gioia, G. A., Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Adult Version (BRIEF-A), Lutz, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, 2005.

- Çak, H. T., Çengel, S. E., Gökler, B., Öktem, F., & Taşkıran, C., "The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function and Continuous Performance Test in Preschoolers with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder," Psychiatry Investigation, 2017, Volume14(3), pp. 260-270. [CrossRef]

- Gioia, G. A., Espy, K. A., & Isquith, P. K., Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function Preschool Version (BRIEF-P:), Lutz, florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, 2003.

- García-Fernández, T., González-Pienda, j. A., Rodríguez-Pérez, C., & Álvarez-García, D., "Psychometric characteristics of the BRIEF scale for the assessment of executive functions in Spanish clinical population," Psicothema, 2014, Volume 26(1), pp. 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Skogan, A. H., Egeland, J., Zeiner, P., Øvergaard, K. R., Oerbeck, B., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., & Aase, H., "Factor structure of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions (BRIEF-P) at age three years," Child Neuropsychology, 2016, Volume 22(4), pp. 472-492. [CrossRef]

- Mahone, E. M., & Hoffman, J., "Behavior Ratings of Executive Function among Preschoolers with ADHD," The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 2007, Volume 21(4), pp. 569-586. [CrossRef]

- Page, M., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Jeremy J. M., Grimshaw, M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. Tianjina, L., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A. and Alonso-fernández, S., "The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews," Revista Española de Cardiologia, 2021, Volume74(9), pp. 790-799. [CrossRef]

- Ezpeleta, L. and Granero, R., "Executive functions in preschoolers with ADHD, ODD, and comorbid ADHD-ODD: Evidence from ecological and performance-based measures," Journal of Neuropsychology, 2015, Volume 9(2), pp. 258-270. [CrossRef]

- Skogan, A. H., Zeiner, P., Egeland, J., Urnes, A.-G., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., & Aase, H., "Parent ratings of executive function in young preschool children with symptoms of attention-deficit/-hyperactivity disorder," Behavioral and Brain Functions, 2015, Volume 11, Article 16. [CrossRef]

- Whiting PF, R. A., Mallett, S., Deeks, J., Reitsma, J., Leeflang, M., Sterne, J., Bossuyt. P. and Q.-2. Group, "QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies.," Annals of Internal Medicine, 2011, Volume 155(8), pp. 529-536. [CrossRef]

- Mallen, C., Peat, G., & Croft, P., "Quality assessment of observational studies is not commonplace in systematic reviews.," Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 2006, Volume 59(8), pp. 765-769. [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, S., Sheffield, T., Nelson, J., Clark, C., Chevalier, N., & Espy, K., "The structure of executive function in 3-year-olds," Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 2011, Volume 108(3), pp. 436-452. [CrossRef]

- Takacs, Z. and Kassai, R., "The efficacy of different interventions to foster children's executive function skills: A series of meta-analyses.," Psychological Bulletin, 2019, Volume 145(7), pp. 653-697. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P., Stringaris, A., Nigg, J., & Leibenluft, E., "Emotion dysregulation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.," The American Journal of Psychiatry , 2014, Volume 171(3) pp. 276-293. [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad, M., Ghanavati, E., Rashid, M., & Nitsche, M. A. , "Hot and cold executive functions in the brain: A prefrontal-cingular network," Brein and Neurocience Advances, 2021, Volume 23; Art. 5. [CrossRef]

| Studies | Likelihood of bias | Concerns about applicability of results | |||||

| Selection of individuals | Index test | Reference test | Flow and schedule | Selection of patients | Index test | ||

| 1 | Low | Low | Low | Doubtful | Doubtful | Low | |

| 2 | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Doubtful | |

| 3 | Low | Low | Low | Doubtful | Low | Doubtful | |

| 4 | Low | Low | Low | Doubtful | Doubtful | Doubtful | |

| 5 | Low | Low | Low | Doubtful | Doubtful | Doubtful | |

| 6 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Doubtful | |

| 7 | Doubtful | Low | Low | Low | Low | Doubtful | |

| Study | Author | BRIEF_P | ADH | Typical Development | |||||

| N | M | STD | N | M | STD | ||||

| 4 | Skogan, et al. (2015) | Flexibility | 104 | 14.10 | 3,20 | 117 | 11.90 | 2.50 | |

| 2 | Ezpeleta, L., & Granero, R. (2015) | Emotional Control | 23 | 14.96 | 4,12 | 538 | 11.97 | 3.40 | |

| 3 | Zhang, H.-F., et al. (2018). | Emotional Control | 163 | 15.10 | 3,53 | 63 | 12.20 | 2.46 | |

| 3 | Zhang, H.-F., et al. (2018). | Flexibility | 163 | 13.40 | 3,03 | 63 | 12.41 | 2.79 | |

| 2 | Ezpeleta, L., & Granero, R. (2015) | Flexibility | 23 | 13.77 | 3,41 | 538 | 13.15 | 3.51 | |

| N: Sample size; M: Mean; STD: Standard Desviation; | |||||||||

| Effect size | Standard error | Z | Sig. (bilateral) | Confidence interval 95% | Prediction interval 95%a | ||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Global | .615 | .1419 | 4.335 | <.001 | .337 | .893 | -.343 | 1.574 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).