Submitted:

30 October 2023

Posted:

30 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

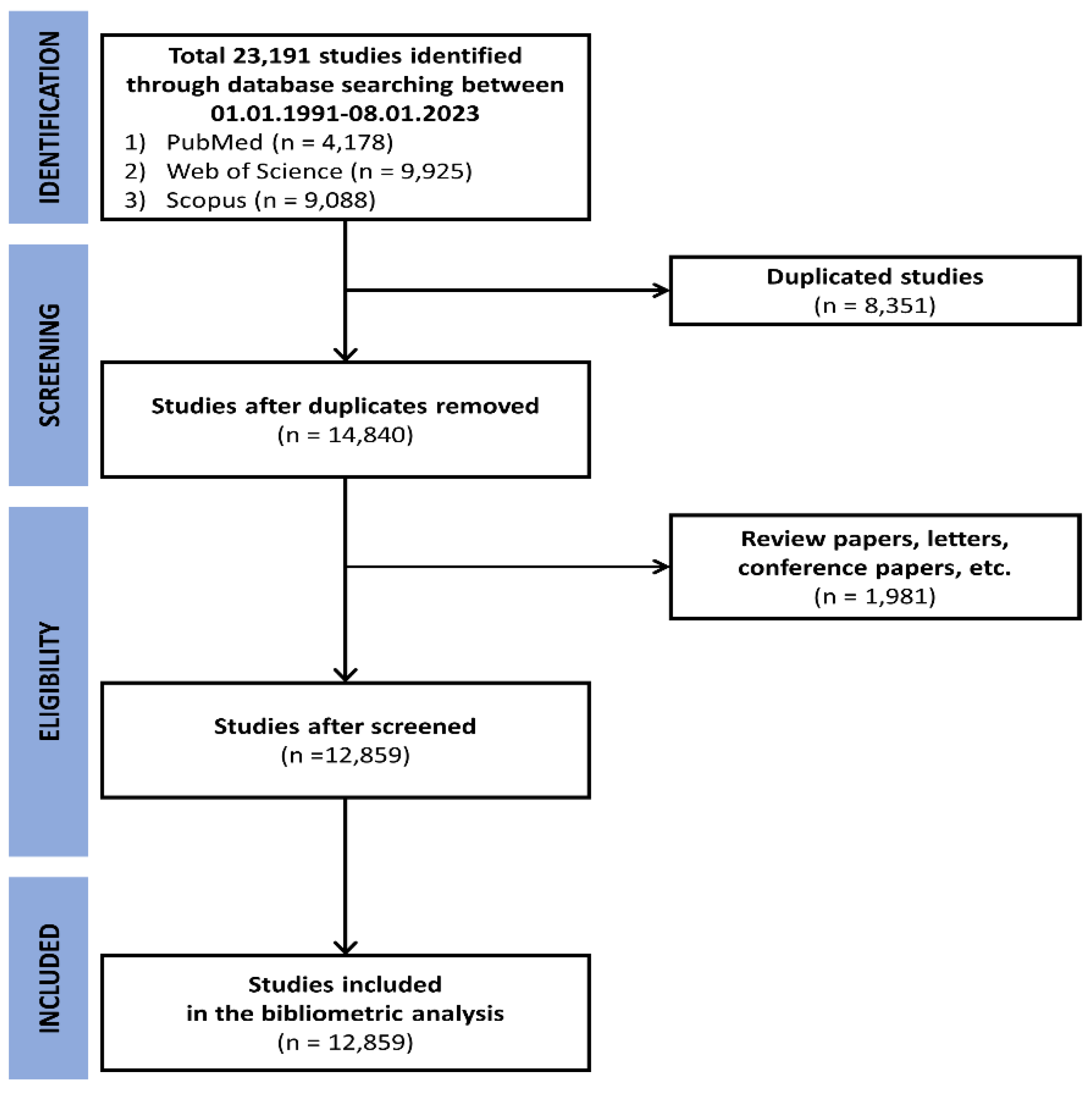

2.1. Bibliometric analysis method

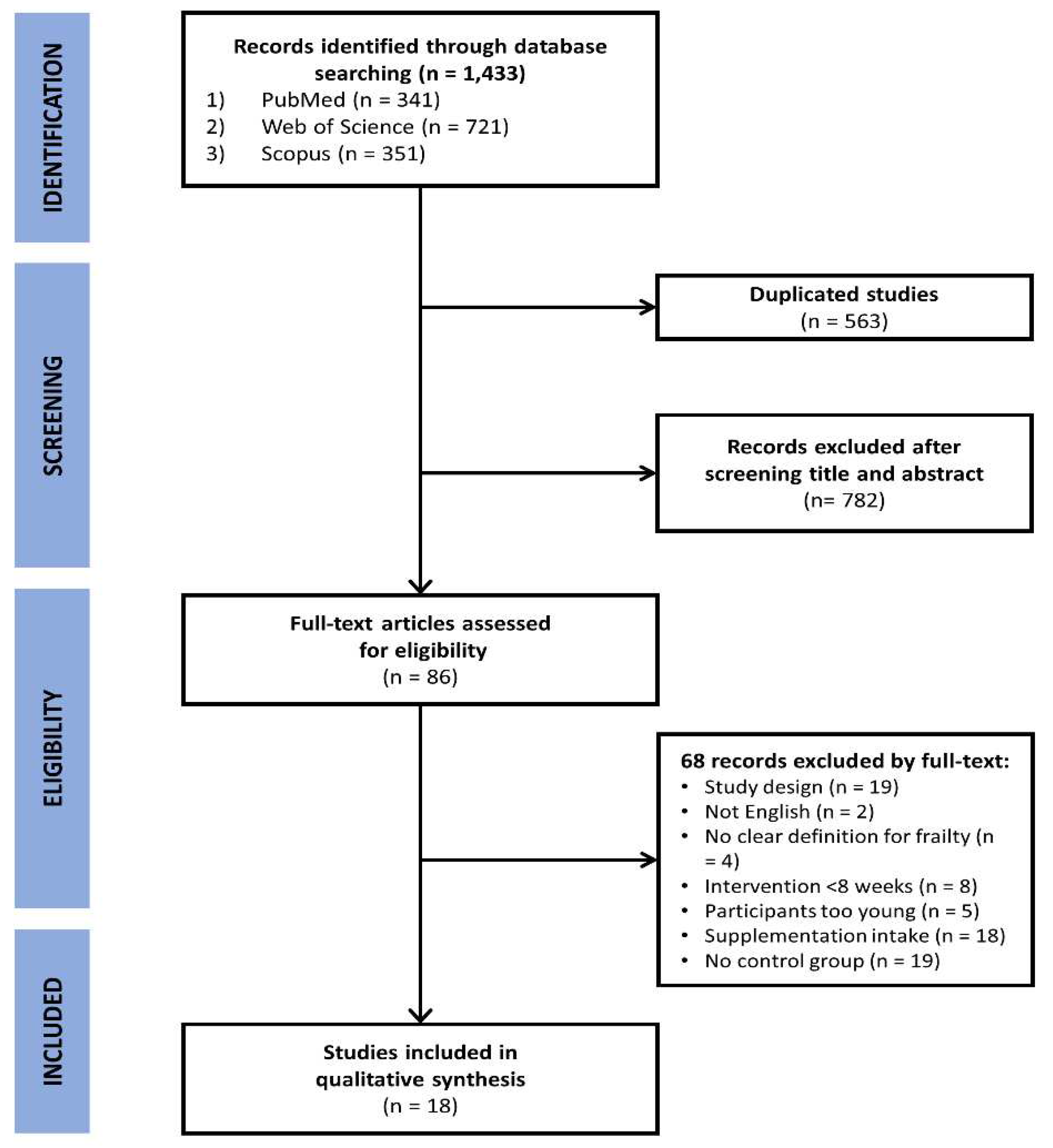

2.2. Meta-analysis method

2.2.1. Data Extraction

2.2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.2.3. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Bibliometric analysis

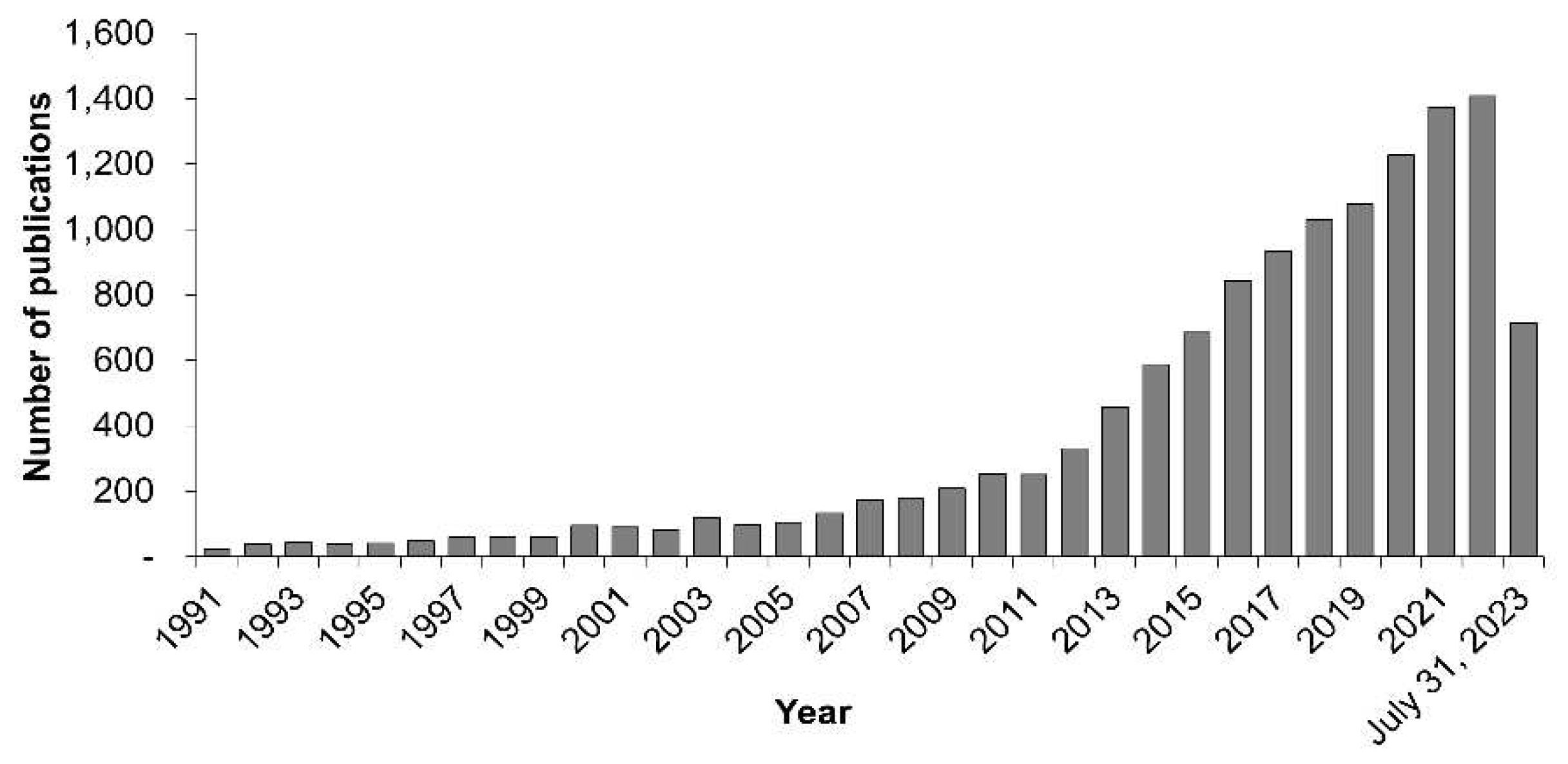

3.1.1. Trend of publication year-wise

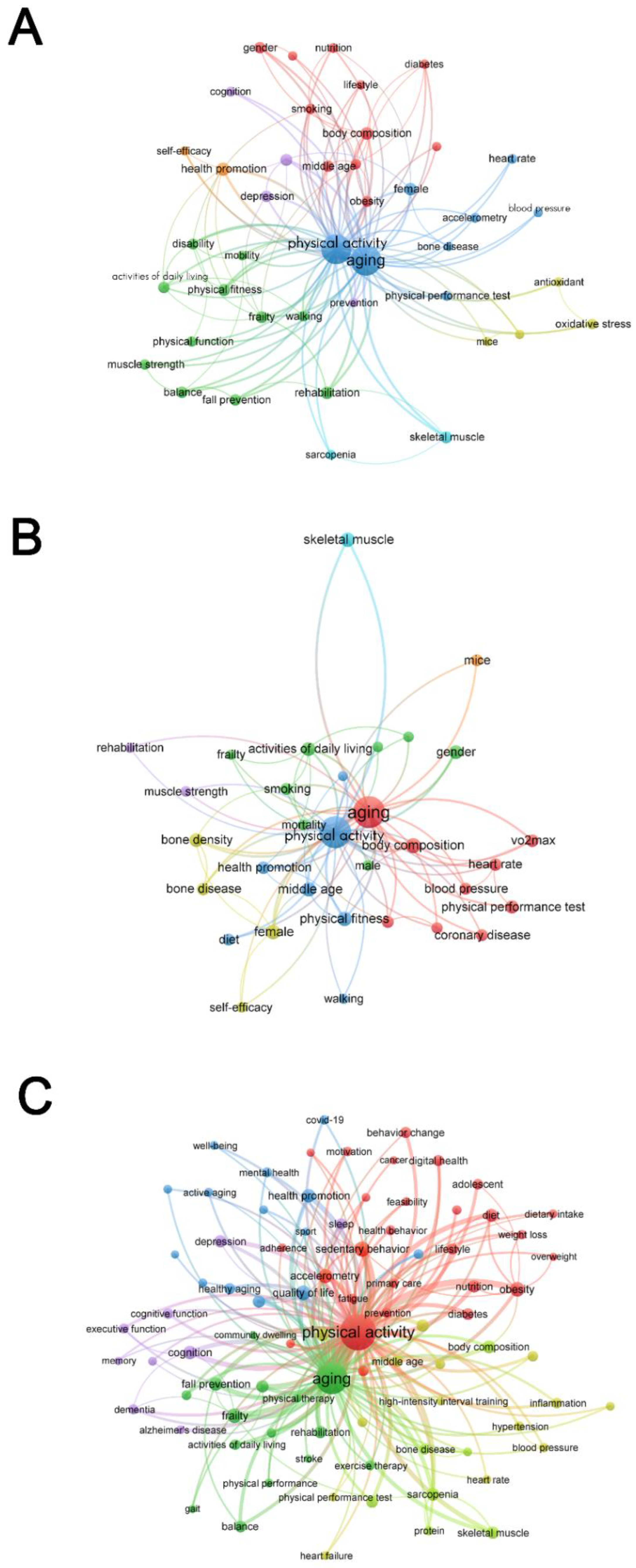

3.1.2. Keywords analysis

3.1.3. Trends in keywords by time

3.2. Meta-analysis

3.2.1. Quality check

3.2.2. Study characteristics

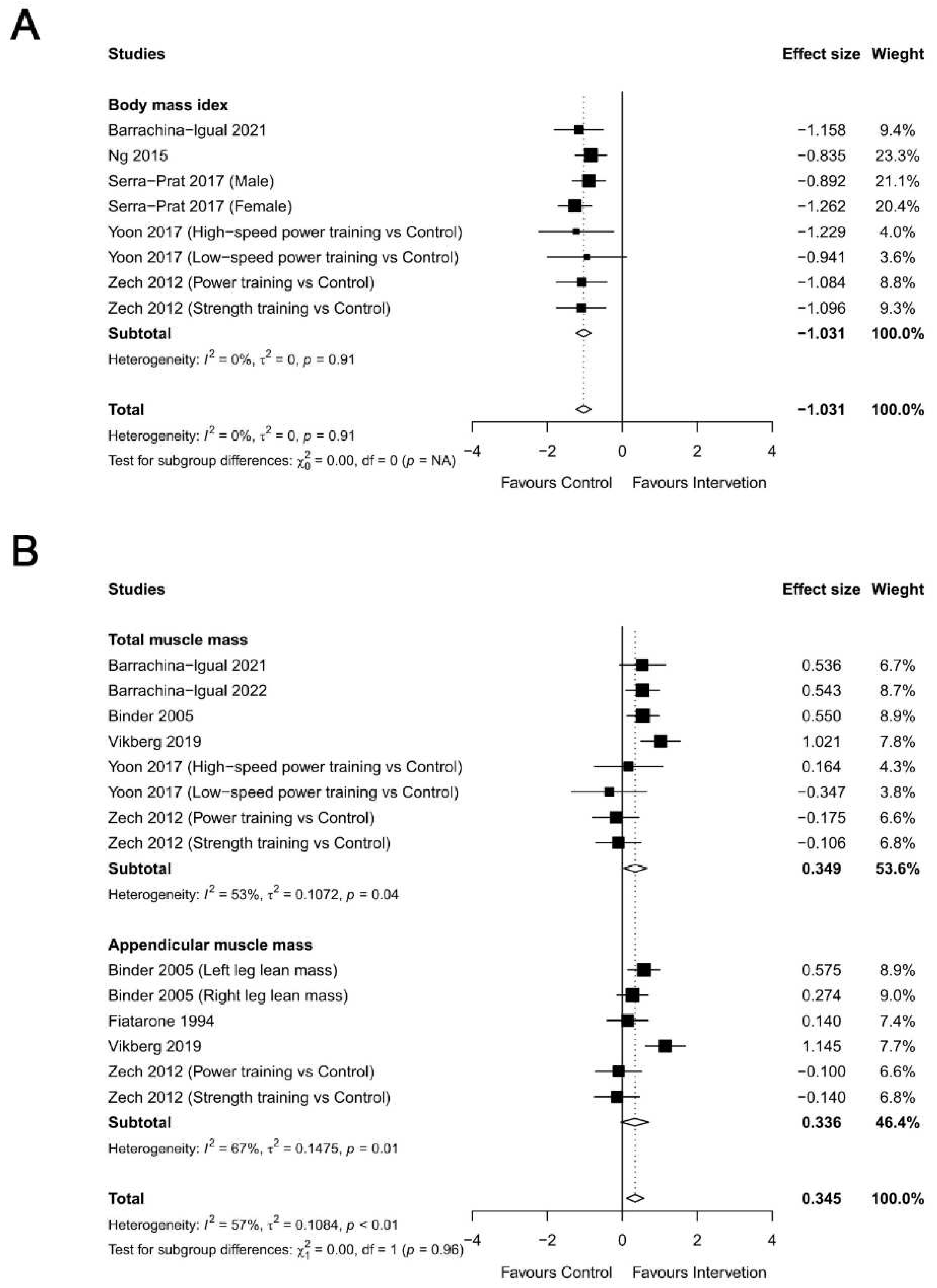

3.2.3. Body Composition

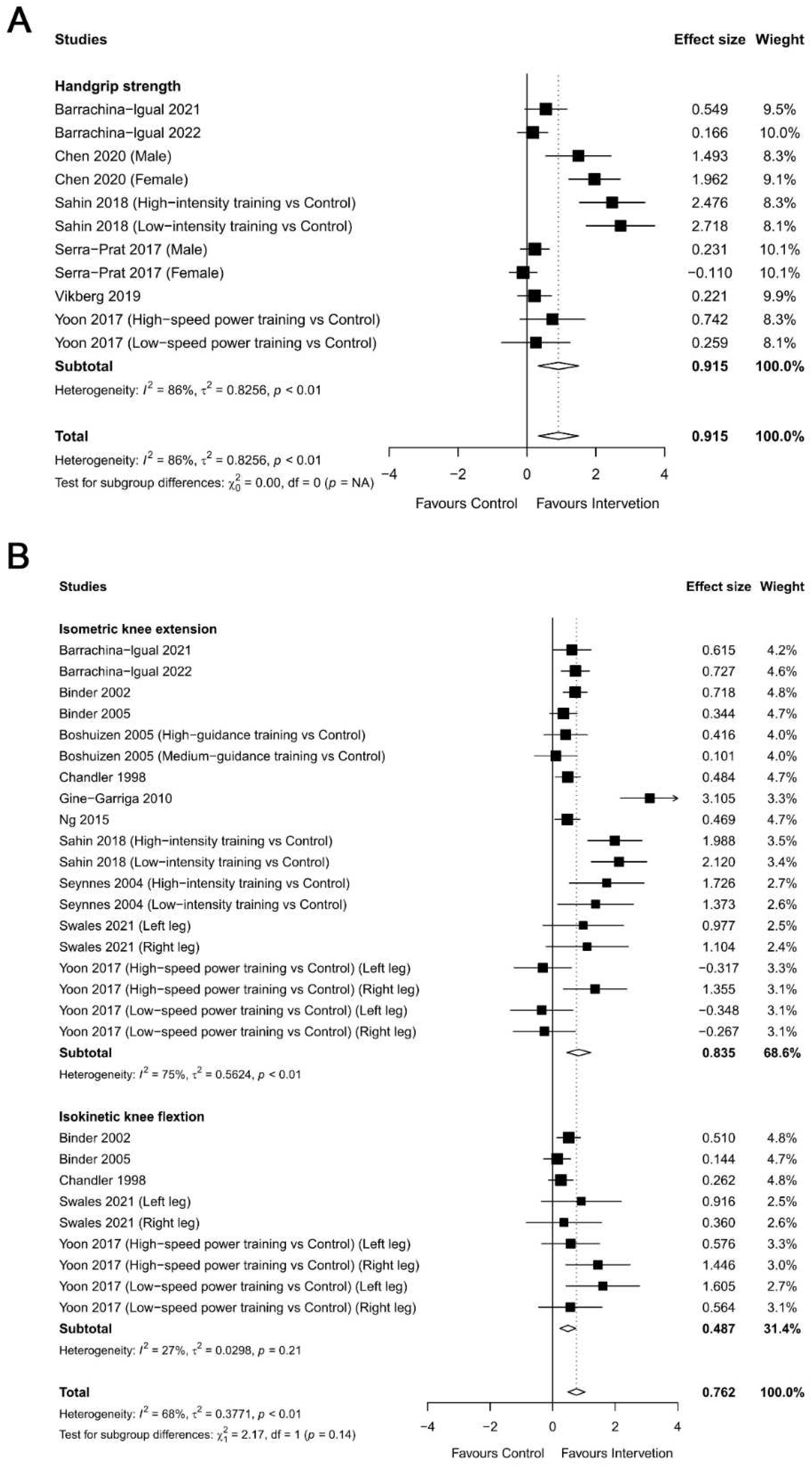

3.2.4. Muscular Strength

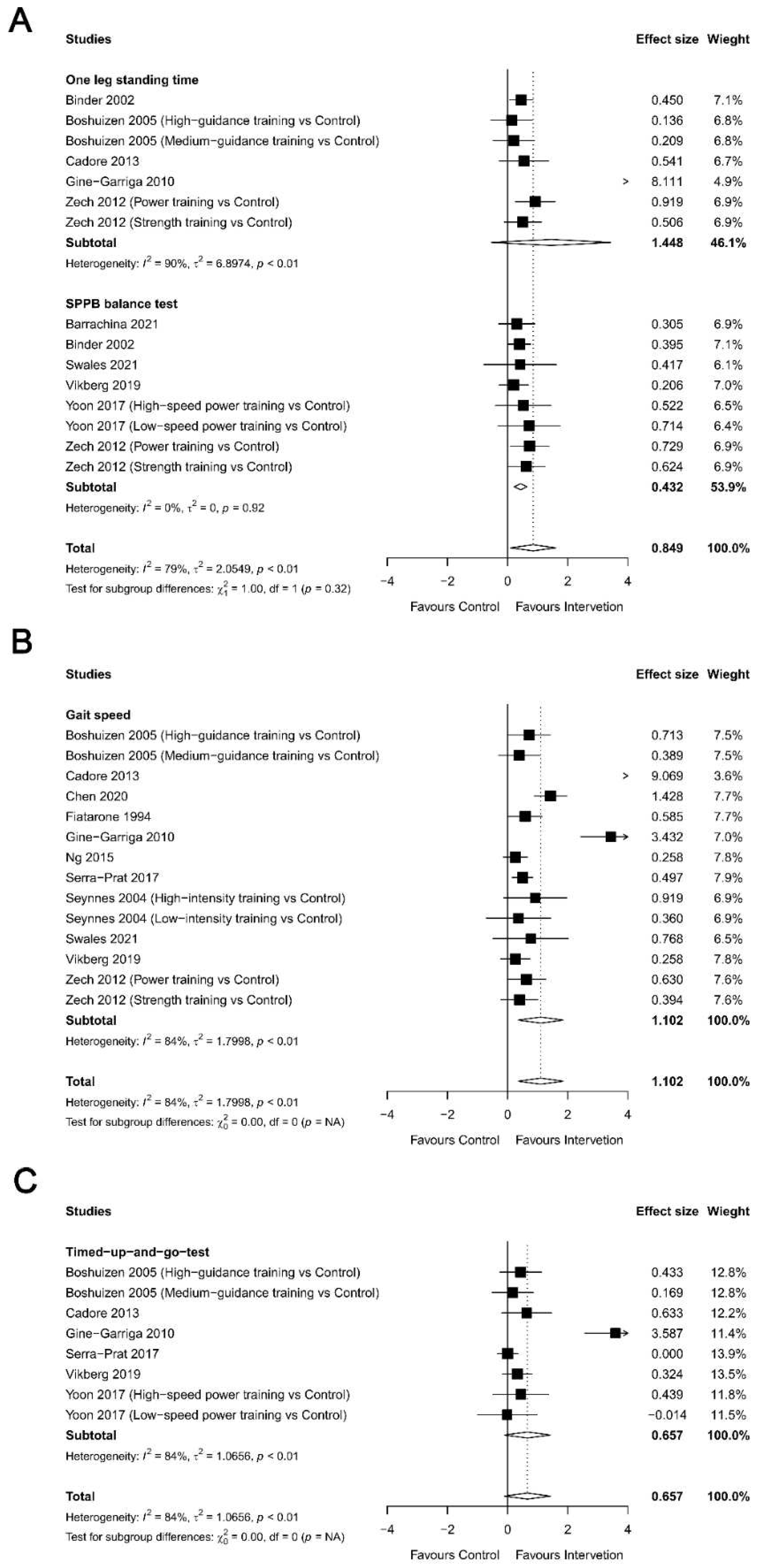

3.2.5. Physical Function

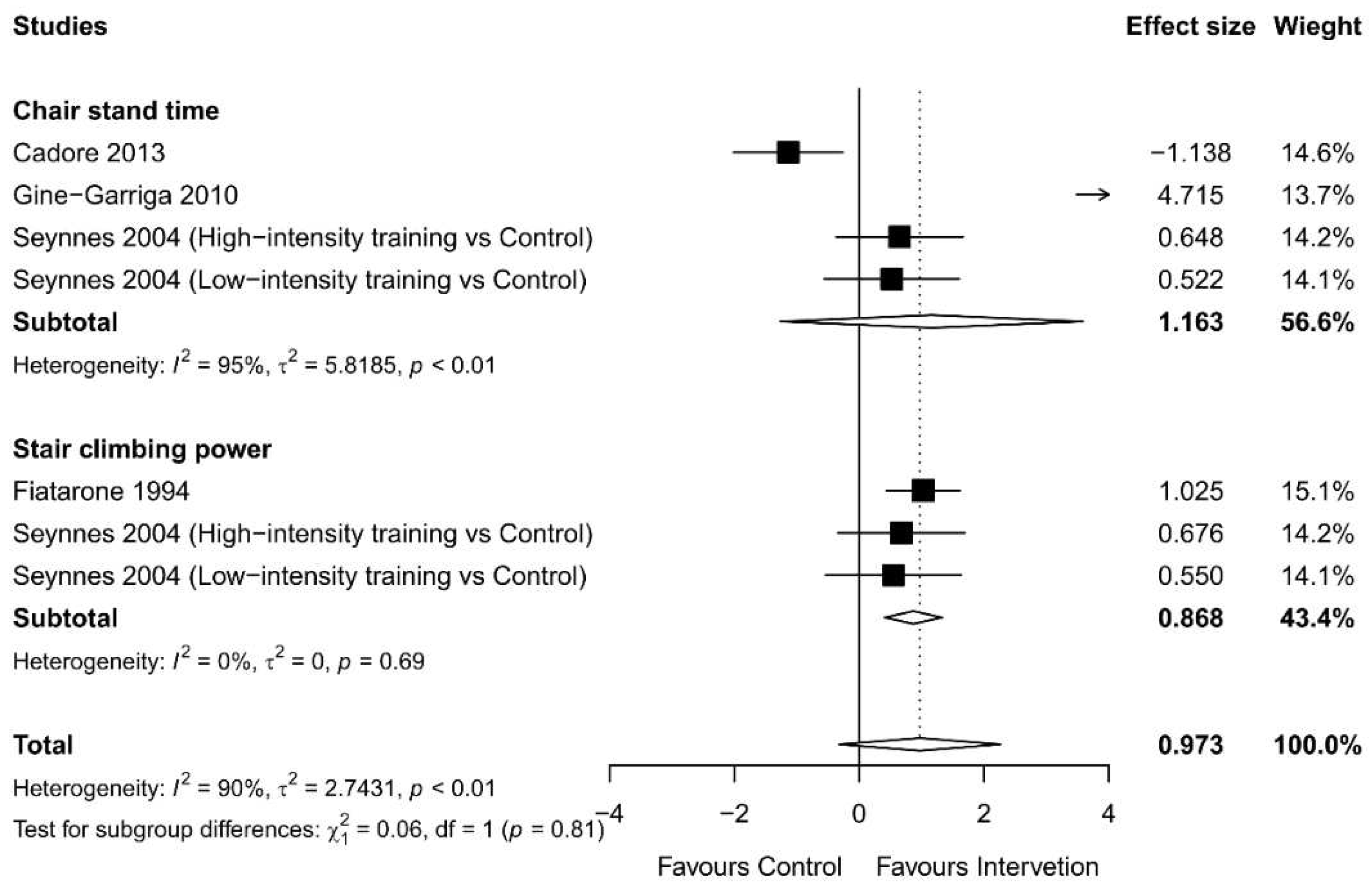

3.2.6. Functional Strength

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dziechciaż, M., & Filip, R. (2014). Biological psychological and social determinants of old age: bio-psycho-social aspects of human aging. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 21(4), 835-838. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. G., Betancourt, L., & Sun, Y. (2005). Molecular Endocrinology and Physiology of the Aging Central Nervous System. Endocrine Reviews, 26(2), 203-250. [CrossRef]

- Evans, W. J. (2010). Skeletal muscle loss: cachexia, sarcopenia, and inactivity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(4), 1123S-1127S. [CrossRef]

- Seene, T., & Kaasik, P. (2012). Muscle weakness in the elderly: role of sarcopenia, dynapenia, and possibilities for rehabilitation. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, 9(2), 109-117. [CrossRef]

- Duchowny, K. A., Clarke, P. J., & Peterson, M. D. (2018). Muscle weakness and physical disability in older americans: Longitudinal findings from the U.S. health and retirement study. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 22(4), 501-507. [CrossRef]

- Buta, B. J., Walston, J. D., Godino, J. G., Park, M., Kalyani, R. R., Xue, Q.-L., Bandeen-Roche, K., & Varadhan, R. (2016). Frailty assessment instruments: Systematic characterization of the uses and contexts of highly-cited instruments. Ageing Research Reviews, 26, 53-61. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A. (2021). The united nations decade of healthy ageing requires concerted global action. Nature Aging, 1(1), 2-2. [CrossRef]

- Cesari, M., Calvani, R., & Marzetti, E. (2017). Frailty in older persons. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 33(3), 293-303. [CrossRef]

- Kuzuya, M. (2012). Process of physical disability among older adults―contribution of frailty in the super-aged society. Nagoya Journal of Medical Science, 74, 31-37.

- Garcia-Garcia, F. J., Gutierrez Avila, G., Alfaro-Acha, A., Amor Andres, M. S., De Los Angeles de la Torre Lanza, M., Escribano Aparicio, M. V., Humanes Aparicio, S., Larrion Zugasti, J. L., Gomez-Serranillo Reus, M., Rodriguez-Artalejo, F., & Rodriguez-Manas, L. (2011). The prevalence of frailty syndrome in an older population from Spain. The Toledo study for healthy aging. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 15(10), 852-856. [CrossRef]

- Merchant, R. A., Morley, J. E., & Izquierdo, M. (2021). Exercise, aging and frailty: Guidelines for increasing function. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 25(4), 405-409. [CrossRef]

- Di Lorito, C., Long, A., Byrne, A., Harwood, R. H., Gladman, J. R. F., Schneider, S., Logan, P., Bosco, A., & van der Wardt, V. (2021). Exercise interventions for older adults: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 10(1), 29-47. [CrossRef]

- Levin, O., Netz, Y., & Zivcorresponding, G. (2017). The beneficial effects of different types of exercise interventions on motor and cognitive functions in older age: a systematic review. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, 14, 20. [CrossRef]

- Rebelo-Marques, A., De Sousa Lages, A., Andrade, R., Ribeiro, C. F., Mota-Pinto, A., Carrilho, F., & Espregueira-Mendes, J. (2018). Aging hallmarks: The benefits of physical exercise [Review]. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 9. [CrossRef]

- Graham, Z. A., Lavin, K. M., O’Bryan, S. M., Thalacker-Mercer, A. E., Buford, T. W., Ford, K. M., Broderick, T. J., & Bamman, M. M. (2021). Mechanisms of exercise as a preventative measure to muscle wasting. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology, 321(1), C40-C57. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, L., Degens, H., Li, M., Salviati, L., Lee, Y. i., Thompson, W., Kirkland, J. L., & Sandri, M. (2019). Sarcopenia: Aging-related loss of muscle mass and function. Physiological Reviews, 99(1), 427-511. [CrossRef]

- Szychowska, A., & Drygas, W. (2022). Physical activity as a determinant of successful aging: a narrative review article. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(6), 1209-1214. [CrossRef]

- Ellegaard, O., & Wallin, J. A. (2015). The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: How great is the impact? Scientometrics, 105(3), 1809-1831. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-L., Ding, G., Feng, N., Wang, M.-H., & Ho, Y.-S. (2009). Global stem cell research trend: Bibliometric analysis as a tool for mapping of trends from 1991 to 2006. Scientometrics, 80(1), 39-58. [CrossRef]

- Zitt, M., Ramanana-Rahary, S., & Bassecoulard, E. (2005). Relativity of citation performance and excellence measures: From cross-field to cross-scale effects of field-normalisation. Scientometrics, 63(2), 373-401. [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2022). VOSviewer manual version 1.6.18. Univeristeit Leiden, 1-54.

- Fragala, M. S., Cadore, E. L., Dorgo, S., Izquierdo, M., Kraemer, W. J., Peterson, M. D., & Ryan, E. D. (2019). Resistance training for older adults: Position statement from the national strength and conditioning association. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 33(8), 2019-2052. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F., Scharhag-Rosenberger, F., Carlsohn, A., Cassel, M., Müller, S., & Scharhag, J. (2011). The intensity and effects of strength training in the elderly. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 108(21), 359.

- *Barrachina-Igual, J., Martínez-Arnau, F. M., Pérez-Ros, P., Flor-Rufino, C., Sanz-Requena, R., & Pablos, A. (2021). Effectiveness of the PROMUFRA program in pre-frail, community-dwelling older people: A randomized controlled trial. Geriatric Nursing, 42(2), 582-591. [CrossRef]

- *Barrachina-Igual, J., Pablos, A., Pérez-Ros, P., Flor-Rufino, C., & Martínez-Arnau, F. M. (2022). Frailty status improvement after 5-month multicomponent program PROMUFRA in community-dwelling older people: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(14), 4077. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/11/14/4077.

- *Binder, E. F., Schechtman, K. B., Ehsani, A. A., Steger-May, K., Brown, M., Sinacore, D. R., Yarasheski, K. E., & Holloszy, J. O. (2002). Effects of exercise training on frailty in community-dwelling older adults: Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50(12), 1921-1928. [CrossRef]

- *Binder, E. F., Yarasheski, K. E., Steger-May, K., Sinacore, D. R., Brown, M., Schechtman, K. B., & Holloszy, J. O. (2005). Effects of progressive resistance training on body composition in frail older adults: Results of a randomized, controlled trial. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 60(11), 1425-1431. [CrossRef]

- *Boshuizen, H. C., Stemmerik, L., Westhoff, M. H., & Hopman-Rock, M. (2005). The effects of physical therapists’ guidance on improvement in a strength-training program for the frail elderly. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 13(1), 5-22. [CrossRef]

- *Cadore, E. L., Casas-Herrero, A., Zambom-Ferraresi, F., Idoate, F., Millor, N., Gómez, M., Rodriguez-Mañas, L., & Izquierdo, M. (2014). Multicomponent exercises including muscle power training enhance muscle mass, power output, and functional outcomes in institutionalized frail nonagenarians. Age (Dordrecht, Netherlands), 36(2), 773-785. [CrossRef]

- *Chandler, J. M., Duncan, P. W., Kochersberger, G., & Studenski, S. (1998). Is lower extremity strength gain associated with improvement in physical performance and disability in frail, community-dwelling elders?. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 79(1), 24-30. [CrossRef]

- *Chen, R., Wu, Q., Wang, D., Li, Z., Liu, H., Liu, G., Cui, Y., & Song, L. (2020). Effects of elastic band exercise on the frailty states in pre-frail elderly people. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 36(9), 1000-1008. [CrossRef]

- *Fiatarone, M. A., O'Neill, E. F., Ryan, N. D., Clements, K. M., Solares, G. R., Nelson, M. E., Roberts, S. B., Kehayias, J. J., Lipsitz, L. A., & Evans, W. J. (1994). Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. New England Journal of Medicine, 330(25), 1769-1775. [CrossRef]

- *Giné-Garriga, M., Guerra, M., Pagès, E., Manini, T. M., Jiménez, R., & Unnithan, V. B. (2010). The effect of functional circuit training on physical frailty in frail older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 18(4), 401-424. [CrossRef]

- *Ng, T. P., Feng, L., Nyunt, M. S. Z., Feng, L., Niti, M., Tan, B. Y., Chan, G., Khoo, S. A., Chan, S. M., Yap, P., & Yap, K. B. (2015). Nutritional, physical, cognitive, and combination interventions and frailty reversal among older adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. The American Journal of Medicine, 128(11), 1225-1236.e1221. [CrossRef]

- *Sahin, U. K., Kirdi, N., Bozoglu, E., Meric, A., Buyukturan, G., Ozturk, A., & Doruk, H. (2018). Effect of low-intensity versus high-intensity resistance training on the functioning of the institutionalized frail elderly. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 41(3), 211-217. [CrossRef]

- *Serra-Prat, M., Sist, X., Domenich, R., Jurado, L., Saiz, A., Roces, A., Palomera, E., Tarradelles, M., & Papiol, M. (2017). Effectiveness of an intervention to prevent frailty in pre-frail community-dwelling older people consulting in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Age and Ageing, 46(3), 401-407. [CrossRef]

- *Seynnes, O., Fiatarone Singh, M. A., Hue, O., Pras, P., Legros, P., & Bernard, P. L. (2004). Physiological and functional responses to low-moderate versus high-intensity progressive resistance training in frail elders. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 59(5), M503-M509. [CrossRef]

- *Swales, B., Whittaker, A., & Ryde, G. (2022). P04-11 A physical activity intervention designed to improve multi-dimensional health and functional capacity of frail older adults in residential care: a randomised controlled feasibility study. European Journal of Public Health, 32(Supplement_2). [CrossRef]

- *Vikberg, S., Sörlén, N., Brandén, L., Johansson, J., Nordström, A., Hult, A., & Nordström, P. (2019). Effects of resistance training on functional strength and muscle mass in 70-year-old individuals with pre-sarcopenia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(1), 28-34. [CrossRef]

- *Yoon, D. H., Kang, D., Kim, H.-j., Kim, J.-S., Song, H. S., & Song, W. (2017). Effect of elastic band-based high-speed power training on cognitive function, physical performance and muscle strength in older women with mild cognitive impairment. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 17(5), 765-772. [CrossRef]

- *Zech, A., Drey, M., Freiberger, E., Hentschke, C., Bauer, J. M., Sieber, C. C., & Pfeifer, K. (2012). Residual effects of muscle strength and muscle power training and detraining on physical function in community-dwelling prefrail older adults: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatrics, 12(1), 68. [CrossRef]

- Waltman, L., van Eck, N. J., & Noyons, E. C. M. (2010). A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks. Journal of Informetrics, 4(4), 629-635. [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523-538. [CrossRef]

- Leeson, G. W. (2018). The growth, ageing and urbanisation of our world. Journal of Population Ageing, 11(2), 107-115. [CrossRef]

- Collard, R. M., Boter, H., Schoevers, R. A., & Oude Voshaar, R. C. (2012). Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: A systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(8), 1487-1492. [CrossRef]

- Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Rikkert, M. O., & Rockwood, K. (2013). Frailty in elderly people. The Lancet, 381(9868), 752-762. [CrossRef]

- Hoogendijk, E. O., & Dent, E. (2022). Trajectories, transitions, and trends in frailty among older adults: A review. Annals of Geriatric Medicine and Research, 26(4), 289-295. [CrossRef]

- Jayanama, K., Theou, O., Godin, J., Mayo, A., Cahill, L., & Rockwood, K. (2022). Relationship of body mass index with frailty and all-cause mortality among middle-aged and older adults. BMC Medicine, 20(1), 404. [CrossRef]

- Goodpaster, B. H., Carlson, C. L., Visser, M., Kelley, D. E., Scherzinger, A., Harris, T. B., Stamm, E., & Newman, A. B. (2001). Attenuation of skeletal muscle and strength in the elderly: The Health ABC Study. Journal of Applied Physiology, 90(6), 2157-2165. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A. K., & Kirkland, J. L. (2016). Aging and adipose tissue: potential interventions for diabetes and regenerative medicine. Experimental Gerontology, 86, 97-105. [CrossRef]

- Meeuwsen, S., Horgan, G. W., & Elia, M. (2010). The relationship between BMI and percent body fat, measured by bioelectrical impedance, in a large adult sample is curvilinear and influenced by age and sex. Clinical Nutrition, 29(5), 560-566. [CrossRef]

- Monteil, D., Walrand, S., Vannier-Nitenberg, C., Oost, B. V., & Bonnefoy, M. (2020). The relationship between frailty, obesity and social deprivation in non-institutionalized elderly people. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 24(8), 821-826. [CrossRef]

- Fried, L. P., Tangen, C. M., Walston, J., Newman, A. B., Hirsch, C., Gottdiener, J., Seeman, T., Tracy, R., Kop, W. J., & Burke, G. (2001). Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56(3), M146-M157.

- Koopman, R., & Loon, L. J. C. v. (2009). Aging, exercise, and muscle protein metabolism. Journal of Applied Physiology, 106(6), 2040-2048. [CrossRef]

- Dibble, L. E., Hale, T. F., Marcus, R. L., Droge, J., Gerber, J. P., & LaStayo, P. C. (2006). High-intensity resistance training amplifies muscle hypertrophy and functional gains in persons with Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders, 21(9), 1444-1452. [CrossRef]

- Denys, K., Cankurtaran, M., Janssens, W., & Petrovic, M. (2009). Metabolic syndrome in the elderly: an overview of the evidence. Acta Clinica Belgica, 64(1), 23-34. [CrossRef]

- Bårdstu, H. B., Andersen, V., Fimland, M. S., Raastad, T., & Saeterbakken, A. H. (2022). Muscle strength is associated with physical function in community-dwelling older adults receiving home care: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 856632. [CrossRef]

- Wickramarachchi, B., Torabi, M. R., & Perera, B. (2023). Effects of physical activity on physical fitness and functional ability in older adults. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 9, 23337214231158476. [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R. P., Kraemer, W. J., Snih, S. A., & Peterson, M. D. (2018). Handgrip strength and health in aging adults. Sports Medicine, 48(9), 1993-2000. [CrossRef]

- Bean, J. F., Leveille, S. G., Kiely, D. K., Bandinelli, S., Guralnik, J. M., & Ferrucci, L. (2003). A comparison of leg power and leg strength within the InCHIANTI study: which influences mobility more? The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 58(8), M728-M733. [CrossRef]

- Billot, M., Calvani, R., Urtamo, A., Sánchez-Sánchez, J. L., Ciccolari-Micaldi, C., Chang, M., Roller-Wirnsberger, R., Wirnsberger, G., Sinclair, A., Vaquero-Pinto, N., Jyväkorpi, S., Öhman, H., Strandberg, T., Schols, J., Schols, A., Smeets, N., Topinkova, E., Michalkova, H., Bonfigli, A. R., . . . Freiberger, E. (2020). Preserving mobility in older adults with physical frailty and sarcopenia: Opportunities, challenges, and recommendations for physical activity interventions. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 15, 1675-1690. [CrossRef]

- Osoba, M. Y., Rao, A. K., Agrawal, S. K., & Lalwani, A. K. (2019). Balance and gait in the elderly: A contemporary review. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology, 4(1), 143-153. [CrossRef]

- Skelton, D. A., & Beyer, N. (2003). Exercise and injury prevention in older people. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 13(1), 77-85. [CrossRef]

- Berg, K. O., Maki, B. E., Williams, J. I., Holliday, P. J., & Wood-Dauphinee, S. L. (1992). Clinical and laboratory measures of postural balance in an elderly population. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 73(11), 1073-1080.

- Thrane, G., Joakimsen, R. M., & Thornquist, E. (2007). The association between timed up and go test and history of falls: The Tromsø study. BMC Geriatrics, 7(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, C., Salarian, A., Carlson-Kuhta, P., Aminian, K., Nutt, J. G., & Horak, F. B. (2010). The instrumented timed up and go test: potential outcome measure for disease modifying therapies in Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 81(2), 171-176. [CrossRef]

- Lemos, E. C. W. M., Guadagnin, E. C., & Mota, C. B. (2020). Influence of strength training and multicomponent training on the functionality of older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria & Desempenho Humano, 22.

- Henwood, T. R., & Taaffe, D. R. (2006). Short-term resistance training and the older adult: the effect of varied programmes for the enhancement of muscle strength and functional performance. Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging, 26(5), 305-313. [CrossRef]

| 1991-2000 | 2001-2010 | 2011-08.2023 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength | Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength | Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength | |

| 1 | body composition | 29 | 77 | body composition | 50 | 145 | sedentary behavior | 485 | 1290 |

| 2 | female | 25 | 68 | health promotion | 58 | 136 | obesity | 447 | 1225 |

| 3 | physical fitness | 24 | 68 | rehabilitation | 48 | 116 | quality of life | 443 | 1108 |

| 4 | middle age | 23 | 57 | quality of life | 41 | 115 | frailty | 424 | 1126 |

| 5 | activities of daily living | 19 | 56 | female | 46 | 113 | accelerometry | 356 | 951 |

| 6 | bone density | 19 | 51 | frailty | 43 | 103 | cognition | 329 | 899 |

| 7 | gender | 19 | 47 | physical fitness | 42 | 98 | health promotion | 326 | 902 |

| 8 | skeletal muscle | 23 | 45 | depression | 33 | 96 | fall prevention | 311 | 820 |

| 9 | health promotion | 15 | 45 | obesity | 31 | 92 | physical fitness | 283 | 760 |

| 10 | bone disease | 15 | 43 | skeletal muscle | 40 | 91 | diet | 279 | 807 |

| 11 | smoking | 13 | 43 | gender | 38 | 90 | body composition | 265 | 668 |

| 12 | heart rate | 15 | 38 | fall prevention | 37 | 90 | sarcopenia | 260 | 719 |

| 13 | vo2max | 15 | 35 | balance | 33 | 83 | physical function | 256 | 688 |

| 14 | cardiovascular disease | 11 | 35 | disability | 29 | 82 | depression | 253 | 653 |

| 15 | risk factor | 10 | 35 | diet | 26 | 81 | rehabilitation | 252 | 619 |

| 16 | diet | 13 | 31 | smoking | 23 | 75 | skeletal muscle | 245 | 602 |

| 17 | blood pressure | 11 | 31 | middle age | 33 | 70 | nutrition | 228 | 666 |

| 18 | coronary disease | 11 | 28 | mobility | 20 | 68 | walking | 227 | 607 |

| 19 | longitudinal study | 8 | 27 | activities of daily living | 33 | 67 | female | 223 | 520 |

| 20 | mortality | 8 | 27 | walking | 27 | 64 | diabetes | 212 | 523 |

| 21 | male | 8 | 24 | muscle strength | 26 | 62 | muscle strength | 203 | 524 |

| 22 | physical performance test | 16 | 23 | physical function | 26 | 59 | balance | 192 | 500 |

| 23 | mice | 12 | 23 | nutrition | 19 | 58 | middle age | 182 | 360 |

| 24 | muscle strength | 8 | 23 | oxidative stress | 23 | 51 | healthy aging | 178 | 400 |

| 25 | leisure activity | 8 | 21 | cognition | 20 | 50 | lifestyle | 176 | 546 |

| 26 | self-efficacy | 8 | 17 | lifestyle | 18 | 50 | sleep | 166 | 445 |

| 27 | frailty | 7 | 17 | sarcopenia | 21 | 47 | digital health | 157 | 471 |

| 28 | walking | 7 | 16 | self-efficacy | 17 | 47 | behavior change | 156 | 412 |

| 29 | questionnaire | 7 | 16 | diabetes | 17 | 46 | adolescent | 152 | 369 |

| 30 | rehabilitation | 7 | 13 | prevention | 16 | 43 | activities of daily living | 143 | 392 |

| Study | Eligibility criteria | Random allocation | Concealed allocation | Groups Similar at Baseline | Blinding of participants | Blinding of therapists | Blinding of assessors | Adequate follow-up (<15% Dropouts) | Intention-to-treat analysis | Between-group comparisons | Point estimates and variability | PEDro Score (0–10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiatarone et al. 1994 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Chandler et al. 1998 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Binder et al. 2002 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 5 |

| Seynnes et al.2004 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | 4 |

| Binder et al. 2005 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | 4 |

| Boshuizen et al. 2005 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | 4 |

| Giné-Garriga et al. 2010 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Zech et al. 2012 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 7 |

| Ng et al. 2015 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Cadore et al. 2014 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Serra-Prat et al. 2017 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | 5 |

| Yoon et al. 2017 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | 4 |

| Sahin et al. 2018 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | 4 |

| Vikberg et al. 2019 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 7 |

| Chen et al. 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 7 |

| Barrachina et al. 2021 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | 5 |

| Barrachina-Igual et al. 2022 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 5 |

| Swales et al. 2022 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

| Study (Year, Country) |

N (IG/CG) |

Age (years) |

Gender (M/F) | Duration (Frequency) | Intervention | CG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiatarone et al. 1994 (USA) |

51 (25/26) |

IG 86.2±5.0 CG 89.2±4.0 |

21/30 | 10 (3x/week) |

Progressive lower extremity RT - Hip and knee extensors (80% of 1-RM) |

- |

| Chandler et al. 1998 (USA) |

100 (50/50) |

77.6±7.6 | 50/50 | 10 (3x/week) |

Progressive lower extremity RT - Resisted hip extension and abduction, knee flexion and extension, ankle dorsiflexion, toe raises, chair rises, and stair stepping (2 set x 10 rep) - Once the participant could perform two sets of 10 easily at a given color of theraband, the resistance was increased by replacing the theraband with the next color |

No resistance training was allowed, but aerobic or flexibility exercises were permitted |

| Binder et al. 2002 (USA) |

115 (66/49) |

IG 83.0±4.0 CG 83.0 ± 4.0 |

55/60 | 36 (2-3x/week) |

Three approximately 3-month-long phases of ET - Phase 1: 22 exercises that focused on improving flexibility, balance, coordination, speed of reaction and, to a modest extent, strength - Phase 2: Progressive RT (1-2 set x 6-8 rep, 65 % of 1-RM) - Phase 3: Endurance training 15-20min (65-75% of VO2peak) - Shortened programs of Phase 1 and Phase 2 exercises were continued during Phase 3 |

Home-based exercise program focused primarily on flexibility (60min, 2-3x/week) was performed |

| Seynnes et al. 2004 (France) |

22 (HI 8/ LI 6/ CG 8) |

81.5 | N/A | 10 (3x/week) |

Progressive lower extremity RT - Knee extensor muscles - HI: 3 set x 8 rep, 80% of 1-RM - LI: 3 set x 8 rep, 40% of 1-RM |

- |

| Binder et al. 2005 (USA) |

91 (53/38) |

83.0±4.0 | 42/49 | 36 (3x/week) |

Multi-component exercise program - 1-12weeks: Light-resistance + flexibility + balance training - 13-24week: Resistance + Flexibility + balance training - 25-36week: Resistance + Flexibility + balance + endurance training |

Home-based exercise program focused primarily on flexibility (60min, 2-3x/week) was performed |

| Boshuizen et al. 2005 (Netherlands) |

72 (HG 24/MG 26/CG 22) |

HG 80.0±6.7 MG 79.3±7.0 CG 77.2±6.5 |

4/68 | 10 (3x/week) |

Lower extremity RT - HG: 2 group sessions + 1 home session - MG: 1 group session + 2 home session |

- |

| Giné-Garriga et al. 2010 (Spain) |

51 (26/25) |

84.0±2.9 | 20/31 | 12 (2x/week) |

Progressive lower extremity RT + balance training - 1 day of balance-based activities and 1 day of lower body strength-based exercises (RPE intensity of 12–14; 1-2set x 6-8 rep) |

- |

| Zech et al. 2012 (Germany) |

69 (ST 23/ PT 24/ CG 22) |

ST 77.8±6.1 PT 77.4±6.2 CG 75.9±7.8 |

N/A | 12 (2x/week) |

Progressive RT + Balance training - ST: with an ‘average’ velocity (2–3 s) - PT: move as rapidly as possible during the concentric phase of each repetition and to move slowly during the eccentric phase (2–3 s) |

- |

| Cadore et al. 2014 (Spain) |

24 (11/13) |

IG 93.4±3.2 CG 90.1±1.1 |

7/14 | 12 (2x/week) |

Multi-component exercise program - Upper and lower body RT with progressively increased loads (1 x 8-10 rep, 40-60% of 1-RM) with balance and gait retraining |

Mobility exercises were performed 30min per day (4x/week) |

| Ng et al. 2015 (Singapore) |

98 (48/50) |

70.0±4.7 | 43/55 | 24 (2x/week) |

Progressive RT + functional tasks + balance training - 1-12 weeks: classes conducted by a qualified trainer - 13-24 weeks: home-based exercises |

- |

| Serra-Prat et al. 2017 (Spain) |

172 (80/92) |

IG 77.9±5.0 CG 78.8±4.9 |

75/97 | 48 (4x/week) |

Multi-component exercise program - Aerobic exercise: walking outdoors for 30-45min - Strengthening arms, legs, and balance training for 20-25 min |

- |

| Yoon et al. 2017 (Korea) |

58 (HSPT 19/ LSST 19/ CG 20) |

HSPT 75.0±0.9 LSST 76.0±1.3 CG 78.0±1.0 |

0/58 | 12 (2x/week) |

Progressive RT with elastic bands - HSPT: Low-intensity, 2-3 set x 12-15 rep - LSST: High-intensity, 2-3 set x 8-10 rep |

Static and dynamic stretching exercises (60min, 1x/week) were performed |

| Sahin et al. 2018 (Turkey) |

48 (HI 16/ LI 16/ CG 16) |

HI 84.2±6.9 LI 84.5± 4.8 CG 85.4±4.7 |

N/A | 8 (3x/week) |

Whole body RT - HI: 1 set x 6-10 rep, 70% of 1-RM - LI: 1 set x 6-10 rep, 40% of 1-RM |

- |

| Vikberg et al. 2019 (Sweden) |

70 (36/34) |

70.9±0.03 | 32/38 | 10 (3x/week) |

Whole body RT, with a focus on strengthening of the lower-extremity - Moderate to high RT intensity was applied using the Borg CR-10 scale (6-7/10) - 1week: 2set x 12 rep - 2-4 weeks: 3set x 10 rep - 5-7 weeks: 4set x 10 rep - 8-10 weeks: 4set x 10 rep |

- |

| Chen et al. 2020 (China) |

70 (35/35) |

IG 77.0±5.2 CG 75.3±6.0 |

23/43 | 8 (3x/week) |

Whole body RT with elastic bands - 2 set x 10-15 rep |

- |

| Barrachina-Igual et al. 2021 (Spain) | 50 (27/23) |

75.0±7.0 | 13/37 | 12 (2x/week) |

Multi-component exercise program - Balance, flexibility, aerobic (10min warming-up) and progressive RT (3set x 10-15 rep, 70% of 1-RM) combined with self-massage for myofascial release |

- |

| Swales et al. 2022 (UK) |

11 (6/5) |

86.1±7.2 | 4/7 | 6 (3x/week) |

RT - Warm-up for 5min - Resistance training: optimal rhomboid, hip adduction, hip abduction, chest press, leg extension, leg curl, leg press (2 set x 12 rep) |

- |

| Barrachina-Igual et al. 2022 (Spain) | 81 (39/42) |

77.6±7.5 | 13/68 | 20 (2x/week) |

Multi-component exercise program - Warm-up exercise: aerobic exercise and joint mobility for 10 min - Progressive high intensity RT: 6 strength exercise (2 trunk, 2 arms and 2 legs) 3 set x 8-12 rep for 42-45 min - Self-massage for myofascial release: 7 exercise per session (4 lower limb, 1 chest and 2 back) 1set x 10 rep for 9-10 min |

Continue their routine daily activities |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).