1. Introduction

Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 cases are a significant public health concern for managing disease outbreaks [

1]. The absence of symptoms in asymptomatic cases contributed to contact-tracing and infection screening challenges amidst the coronavirus-disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [

2] with many infections remaining silent in the community unless identified through active screening in contact tracing or workplace and healthcare screening. SARS-CoV-2 is the pathogen causing COVID-19. It can exhibit different symptom profiles (SP) in hosts [

3]. For this study, SP includes symptomatic (patients who return positive nucleic acid tests (PCR) for SARS-CoV-2 and display clinical symptoms throughout their infection period) or asymptomatic (symptom-free patients with a positive PCR, have no previous symptoms, and no symptoms reported throughout the isolation until a negative test result was returned) [

4,

5].

Asymptomatic infection in 2020-21 was more prevalent in children and young adults compared to the elderly, while symptomatic infection was more common in older adults and the elderly [

6,

7]. A systematic review subgroup analysis of eight studies, revealed of 318 asymptomatic cases in China, 49.6% were children under 18 years, 30.3% were adults aged 19 to 50 years, and only 16.9% were elderly aged 51 years plus [

7]. Age thus has potential to complement future screening interventions worldwide as a major SARS-CoV-2 SP descriptor if these observations still hold with the arrival of new variants of concern. Further, a recent study also indicates the non-homogeneous incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infections across Victoria in 2020 may be due to varying socio-economic conditions, and such factors may be important for consideration in public health policy in developing pandemic mitigation strategies [

8].

Interim phase III trial data for the AstraZeneca vaccine, the only trial to actively test participants to detect any infection regardless of symptoms, reported no change in asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection incidence whilst symptomatic infection rates fell [

9]. This raised the question of how the profile of asymptomatic infections and infections overall might change in a post-vaccine population. The number of asymptomatic infections in the phase III trials were small, and therefore the degree to which asymptomatic cases persist or are prevented post-vaccination is unclear and may vary by demographics across populations. Identifying relationships between demography and SPs could therefore have important outbreak management implications, such as informing active screening processes.

In this study we analyse COVID-19 outbreak data in Australia before vaccinations were introduced to see if it is possible to distinguish asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 cases based on social and demographic characteristics [

5]. A recent study postulated certain HLA genes may mediate asymptomatic COVID-19 infections, suggesting population genetic differences in propensity to contract an infection or symptom development once infected. In particular, the authors postulate that HLA haplotypes may alter the t-cell function, increasing immune memory from other coronavirus infections and provide cross immunity to SARS-CoV-2 on first exposure. Predictors of symptom outcomes are crucial to understand in infection management and assist public health authorities support those most at risk of developing severe disease. The likelihood of being infectious in the absence of symptoms is also important in public health when managing outbreaks and minimising inadvertent spread of pathogens from asymptomatic carriers [

10].

This study examines COVID-19 symptom profiles according to demographics to characterise the patient cohorts most likely to be symptomatic or asymptomatic, and to determine if ethnicity may play a role in moderating risk in infections following first exposure to a novel coronavirus. A secondary objective was to investigate associations between the development of symptoms and the circumstances of infection exposure type, whether within the household or workplace, where known.

2. Materials and Methods

This study, an observational case series has three aims: to provide comprehensive demographic profiles of pre-vaccinated SARS-CoV-2 cases according to SP, evaluate if associations exist between exposure type and SP, and if certain demographics could predict asymptomatic infection. The data represent SARS-CoV-2 cases detected in the second COVID-19 wave from the Geelong and greater Barwon region of Victoria, Australia.

The data source for this study was the ‘Barwon Health (BH) and Deakin University (DU) COVID-19 Research Task Force and Cohort Study’. Data were gathered from three patient follow-up care report forms of consenting cases who were swabbed at BH testing sites and tested positive by PCR for COVID-19 during the second COVID-19 wave between June-August 2020. Cases were identified via four pathways: people passively presenting for testing because of symptoms, or knowledge of tier-two exposure (on recommendation due to possible exposure or public or other lower risk sites), or those actively identified through workplace screening or outbreak management contact-tracing. After removing ineligible cases (n=43) where SP could not be determined due to missing test date and/or symptom details or cases who did not want to be included, data from a total 328 consenting cases who were symptomatic (n=265) and asymptomatic (n=63) were available for analysis. Multiple imputation and other methods to address missing data may introduce error if an inadequate understanding or erroneous application of such techniques occurs, especially in the context of a novel disease [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Excluding missing data was deemed the most suitable approach. The de-identified sample was drawn from BOSSnet by BH researchers to comprise the final dataset. A password protected file was maintained by DU which included deidentified cases with the following demographics: sex, age, ethnicity, occupation, living-situation, smoker-status, comorbidity, and exposure-type.

All statistical analysis was conducted using Stata, Version 17 [

11]. Duplicated responses were removed, and several new variables were generated; including a categorical age variable to align WHO age classifications and included ‘youth’ (18-24 years), ‘young adult’ (25-44 years), ‘adult’ (45-64 years), and ‘senior’ (65+ years) [

12]. To create subgroups of sufficient size for analyses, ethnicity was categorised into ‘ethnic majority’ (Caucasian) and ‘ethnic minority’ (other ethnicities). Occupation settings included ‘other not working’ and ‘other unknown’. SP was created by crosschecking data on symptoms at test date and symptoms through the monitoring period to identify who was truly asymptomatic, and symptomatic, and a binary variable was created. This is an important strength of this cohort – the ability to discern true asymptomatic cases from those tested in a pre-symptomatic period and not followed-up.

Logistic regression was used to model the relationship between demographic characteristics and SP. Descriptive statistics were produced with associated 95% confidence intervals. Associations of all variables with SP were examined using univariate logistic regression, and variables with a univariate association reaching a level of significance of 0.05 were included in the multivariable models. Sex was also included in the final model given the well documented association with SARS-CoV-2 infection outcomes [

6,

7]. Associations between ethnic minorities and asymptomatic infection were also analysed.

3. Results

3.1. Sample demographic profile

Table 1 presents the demographic profile of SARS-CoV-2 cases, stratified by symptoms (328 symptomatic (n=265) and asymptomatic (n=63) cases). Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 cases comprised 19.2% of the total sample. The mean age of cases was similar across symptom groups, 37.8 years [95% CI 37.2 – 49.1] for asymptomatic cases and 38.1 [95% CI 57.4 – 79.9] for symptomatic, however young adults between 25 and 44 years accounted for a greater proportion of asymptomatic cases (69.8%, 95% CI 57.4 – 79.9) than symptomatic (43%, 95% CI 37.2 – 49.1). There was no association apparent between sex and presence of symptoms, however asymptomatic cases were more likely to be from ethnic minority groups [65%, 95% CI 52.2 – 76.0] compared with symptomatic cases (33.7%, 95% CI 27.4 – 40.5).

Asymptomatic cases were less likely to be HCWs (3.5%) across the total sample, with most not revealing their occupation (44.8%). There were relatively similar proportions of symptomatic and asymptomatic cases who reported comorbidities and who reported none. Most cases had never smoked both in symptomatic (55.6%, 95% CI 45.6 – 65.1) and asymptomatic (90.9%, 95% CI 55.6 – 98.8) groups. All former smokers were symptomatic in this sample. Lastly, there were similar proportions of both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases who acquired their infection across all potential exposure settings. For example, workplace exposure accounted for 35.5% (95% CI 28.9 – 42.8) of symptomatic cases and 34% (95% CI 22.0 – 48.6) of asymptomatic cases.

3.2. Demographic profile of SARS-CoV-2 cases and predicting asymptomatic infection

Table 2 displays the results from the crude and adjusted logistic regression model fitted for asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Associations between demographic characteristics and asymptomatic infection in univariate analysis included age, ethnicity, and occupation. In univariate analyses, young adults (25-44 years) were three times more likely to be asymptomatic [OR 3.1, 95% CI 1.3 – 7.3, p<0.01] compared to those aged 18-24 years. SARS-CoV-2 cases from an ethnic minority were more likely to be asymptomatic [OR 3.7, 95% CI 2.0 – 6.7, p<0.001] than ethnic majority cases.

With health workers as the reference group, those who were not employed (unemployed and other not working) were more likely to be asymptomatic [OR 6.5, 95% CI 1.1 – 38.0, p<0.05]. The likelihood of being an asymptomatic case was lower and similar, across essential service workers and residential aged-care-workers. Comparatively for healthcare workers, transmission risk was high in 2020 relative to the rest of the population. There were no significant differences detected in the likelihood of presenting asymptomatic with respect to sex, comorbidity status, living situation, smoker status or infection exposure location.

In the final multivariable logistic regression model, age, ethnicity, and occupation remained significant covariates of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection independent of sex, however the strength of association varied. Ethnicity remained the most significantly-associated covariate of asymptomatic infection, with the odd of being an asymptomatic case approximately three times greater for those from an ethnic minority background [OR 3.2, 95% CI 1.5 – 6.7, p<0.01]. Seniors were also approximately seven times more likely to be asymptomatic [OR 7.3, 95% CI 1.0 – 50.5, p<0.05] compared to youth aged 18-24 years after adjusting for ethnicity, sex, and occupation. Similarly, those in ‘other unknown’ occupations had a greater likelihood of remaining asymptomatic compared to healthcare workers (OR 7.3, 95% CI 1.5 – 34.6, p<0.05) after adjustment for age, sex, and ethnicity.

3.3. Ethnicity and asymptomatic infection

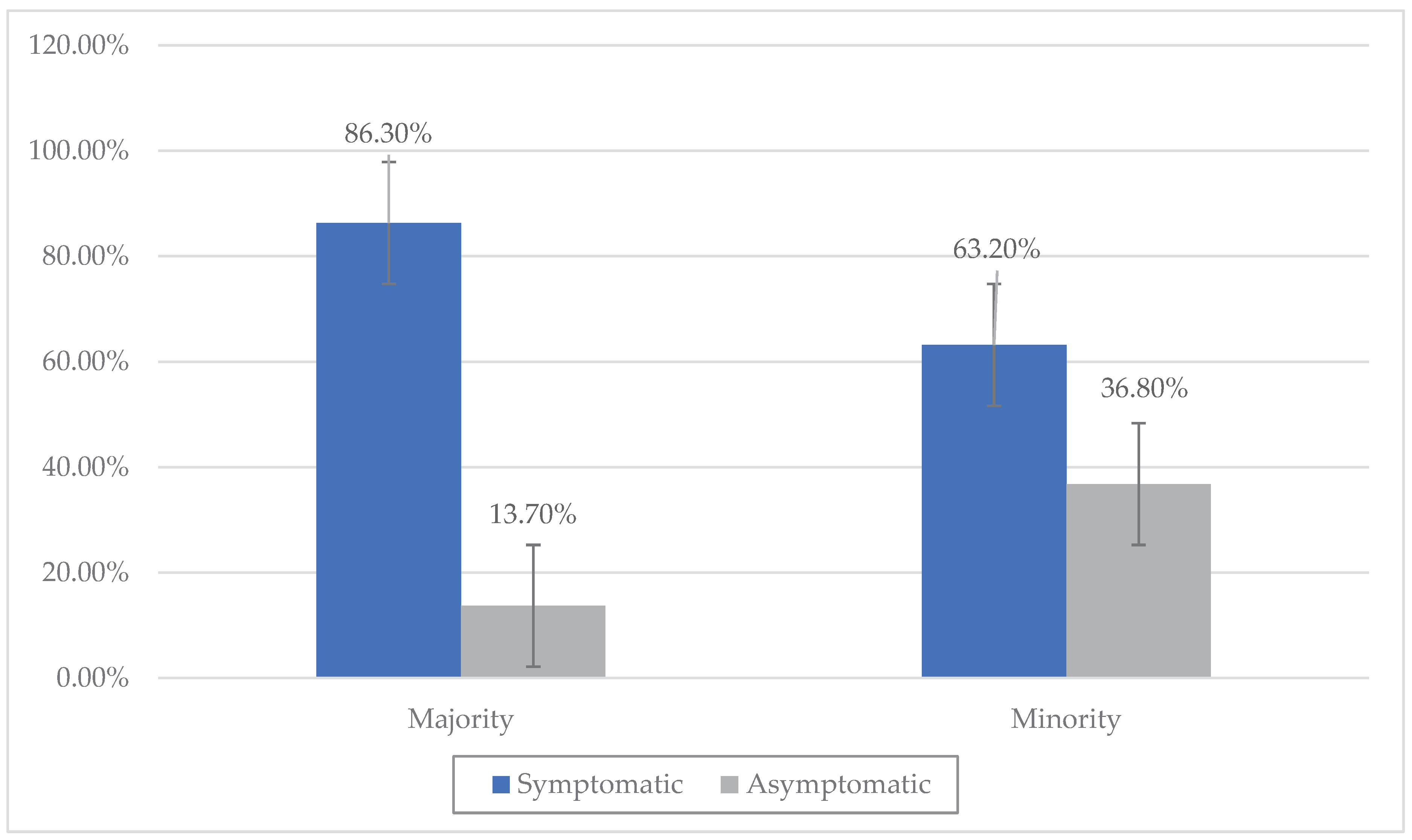

Ethnic minority was a significant covariate in the model for presenting with an asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Figure 1 displays proportions of ethnic majority and minority cases presenting as symptomatic and asymptomatic. A significantly greater proportion of ethnic minority cases were likely to be asymptomatic (36.8%, 95% CI 52.2 – 76.0), compared to ethnic majority cases (13.7%, 95% CI 24.0 – 47.9).

Table 3 provides a breakdown of the ethnic majority and minority groups. Compared with Caucasian cases, all other groups had higher rates of asymptomatic infection, particularly Northeast Asians (41.2%, 95% CI 2.6 – 13.7).

4. Discussion

The study found demographic profiles differed between asymptomatic and symptomatic cases. The overall proportion of asymptomatic and symptomatic cases of 19 percent is consistent with previous population data [

16,

17]. The more detailed demographic analysis in this sample found more young adults were asymptomatic compared to older adults. Importantly, infection rates among younger people have varied with increasing transmissibility of different variants, and immunity instilled by COVID-19 vaccination [

18,

19,

20,

21].

However, in the multivariable model it was age greater than 65 years that was independently associated with asymptomatic infection. This conflicts directly with numerous studies reporting higher asymptomatic infection prevalence in young adults compared to elderly [

6,

7]. This inconsistency may be explained by the small sample size among the seniors and potential age-related confounding factors, including likelihood of getting tested, and thus results should be interpreted with caution [

15].

This study also found most asymptomatic cases (65%) in this sample were cultural and linguistic diverse (CALD) ethnic minorities, and conversely most symptomatic cases (63%) were Caucasian. Previous studies found increased severe SARS-CoV-2 infection risk among ethnic minorities when compared to white counterparts [

22,

23]. We report higher asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection among ethnic minority cases but did not examine severity of symptoms which might also have been more frequent among those ethnic minority cases who did experience symptomatic disease. Also, people from ethnic minority backgrounds in Barwon may have been less likely to get tested even if they had symptoms, if it forced them out of work if unable to work from home [

8]. Conversely, if more likely to be essential workers, then more asymptomatic infections may have been picked up through workplace screening conducted regardless of symptoms.

More severe SARS-CoV-2 illness has been documented among ethnic minorities as a proportion of all reported cases [

16,

22]. Higher intensive care and mortality among Asians [

23], and delayed testing may be one contributing factor.

Many SARS-CoV-2 cases among CALD groups in the Barwon region during this period were associated with large workplace outbreaks [

4]. Because people from ethnic backgrounds are more likely to experience broader CALD related testing barriers compared to Caucasian cases [

23], case ascertainment is likely to vary between these subgroups. For example, although interpreters and communication with community leaders were utilised, there remained significant challenges in building trust among workers of minority ethnicities in some circumstances, where complex household arrangements, insecure casual employment, and fears relating to visa status or other residency issues were prevalent [

4]. As such, some workers from ethnic population groups may have remained reluctant to share symptom information or may have found understanding messaging related to testing and other outbreak mitigation strategies more challenging, than the Caucasian majority [

22]. Consequently, asymptomatic cases may be more likely to be reported through workplace screening or active contact testing in CALD communities, whilst symptomatic cases may be more likely to be underreported outside the workplace setting. Such cultural complexities suggest SARS-CoV-2 SP and its association with ethnic minorities may be influenced by multiple CALD factors [

23,

24,

25,

26].

This study is original in analysing pre-vaccinated SARS-CoV-2 cases according to symptomatic and asymptomatic disease and the association of certain demographic characteristics in the first waves of the pandemic in Australia. This assessment has been largely overlooked in previous studies and may contribute to identifying if and how vaccination status (unvaccinated, dose 1, 2, 3, 4) affects the demographic profile of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Whilst the Barwon survey data provide a unique opportunity to monitor symptom development and determine the profile of early pandemic asymptomatic cases without interference from the timing of testing and possible misclassification of pre-symptomatic cases, the sample size does limit precision and power. Whilst we found statistically significant differences in univariable and multivariable modeling, the confidence intervals demonstrate the possible range of plausible values for these associations, limiting the practical significance of the results based on this cohort alone. Further, numerous confounders could be implicit in the ambiguity of the ‘unknown’ occupation and ethnicity categories and therefore the associations detected here must be considered with caution.

Low numbers in some subpopulation groups may also render results unrepresentative of the general population and reduce external validity. The study is also limited by possible symptom recall bias, potentially misclassifying mild symptomatic cases as asymptomatic, although the prospective nature of the surveys reduces this risk [

27]. The heterogeneity in how cases classify their symptom severity or lack of, makes it difficult to accurately distinguish asymptomatic from presymptomatic, and mild symptomatic infection [

20].

The impact of selection bias is an important consideration in the interpretation of the findings, with cases in this study derived from four separate pathways. Outbreak management and workplace screening are active processes, and are likely to capture most infections, symptomatic or asymptomatic.

5. Conclusions

Overall, this study identified asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection may be associated with CALD groups. Further research is required to understand the interaction between ethnicity, testing patterns and symptom presentation. Ethnic differences in the likelihood of an infection remaining asymptomatic would align with the emerging view that genetic haplotypes might infer different cross -protection from historic infections from related viruses. If so, this might partly offset other findings of increased risk of severe disease in those with symptomatic disease, which may be related to genetic or structural societal and economic differences that can exacerbate infection outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.B, E.A, D.C, B.J.M and S.C.T.S.; methodology, C.M.B, S.C.T.S.; validation, C.M.B and E.A.; formal analysis, S.C.T.S and C.M.B.; investigation, S.C.T.S, D.C, B.J.M, E.A and C.M.B.; resources, E.A and C.M.B; data curation, E.A, D.C and B.J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.T.S and C.M.B.; writing—review and editing, S.C.T.S, D.C, B.J.M, E.A and C.M.B.; visualization, C.M.B and E.A.; supervision, C.M.B and E.A.; project administration, S.C.T.S.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by The Ethics Committee of Barwon Health (20/56 14/05/2020 & 21/91 14/10/2021) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was opt out for inclusion into the database for monitoring COVID-19 cases at Barwon Health. If a patient did not want their information collected by researchers, they informed the Project Manager by phone or email. Information on this study was displayed at testing sites with posters, pamphlets and a website to find information on the research and how to withdraw consent at the time.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the data custodian (D, Cooper). The data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons of the approving institute.

Acknowledgments

Analysis was conducted using Stata, Version 17 (Stata Corp 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organisation Managing epidemics: Key facts about major deadly disease. WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/managing-epidemics-key-facts-about-major-deadly-diseases (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Cheng, H.Y.; Jian, S.W.; Liu, D.P.; Ng, T.C.; Huang, W.T.; Lin, H.H.; Taiwan COVID-19 Outbreak Investigation Team. Contact Tracing Assessment of COVID-19 Transmission Dynamics in Taiwan and Risk at Different Exposure Periods Before and After Symptom Onset. JAMA internal medicine 2020, 9, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation Coronavirus disease. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- [COVID19 Barwon Health and Deakin University COVID-19 Research Task Force and Cohort Study] Barwon Health Geelong. 2020. COVID-19 Second Wave; unpublished data; 20/56 14/05/2020 & 21/91 14/10/2021.

- Gao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Sun, C.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Qiu, S.; Ma, K. A systematic review of asymptomatic infections with COVID-19. Journal of microbiology, immunology 2021, 1, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronbichler, A.; Kresse, D.; Yoon, S.; Lee, K.H.; Effenberger, M.; Shin, J.I. Asymptomatic patients as a source of COVID-19 infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. IJID 2020, 98, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syangtan, G; Bista, S.; Dawadi, P. Asymptomatic SARs-COV-2 Carriers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Public Health 2020, 8, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roder, C.; Maggs, C.; McNamara, B.; O’Brien, D.; Wade, A.J.; Bennett, C.; Pascol, J.A.; Athan, E. Area-level social and economic factors and the local incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Victoria during. Medical Journal of Aust 2020, 7, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voysey, M.; Costa Clemens, S.A.; Madhi, S.A.; Weckx, L.Y.; Folegatti, P.M.; Aley, P.K.; Angus, B.; Baillie, V.L.; Barnabas, S.L.; Bhorat, Q.E.; et al. Single-dose administration and the influence of the timing of the booster dose on immunogenicity and efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine: a pooled analysis of four randomised trials. Lancet 2021, 397, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdolo, D.; L Chatzileontiadou, D. A common allele of HLA is associated with asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature 2023, 620, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp Stata Statistical Software Release 17. Available online: https://www.stata.com/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- World Health Organisation Life course. Available online: https://www.who.int/our-work/life-course (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Ranganathan, P.; Pramesh, C.S.; Aggarwal, R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Logistic regression. Perspect Clin Res. 2017, 8, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, J.; Wang, B. Inconsistency Between Univariate and Multiple Logistic Regressions. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2017, 29, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. The prevention and handling of the missing data. Korean journal of anesthesiology 2016, 45, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentsch, C.T.; Kidwai-Khan, F.; Tate, J.P.; Park, L.S.; King, J.T., Jr; Skanderson, M.; Hauser, R.G.; Schultze, A.; Jarvis, C.I.; Holodniy, M.; et al. Patterns of COVID-19 testing and mortality by race and ethnicity among United States veterans: A nationwide cohort study. PLoS medicine 2020, 17, e1003379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byambasuren, O.; Cardona, M.; Bell, K.; Clark, J.; McLaws, M.L.; Glasziou, P. Estimating the extent of asymptomatic COVID-19 and its potential for community transmission: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMMI 2020, 5, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Han, Z.G.; Qin, P.Z.; Liu, W.H.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.Q.; Li, K.; Xie, C.J.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Transmission and containment of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant of concern in Guangzhou, China: A population-based study. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2022, 16, e0010048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanes-Lane, M.; Winters, N.; Fregonese, F.; Bastos, M.; Perlman-Arrow, S.; Campbell, J.R.; Menzies, D. Proportion of asymptomatic infection among COVID-19 positive persons and their transmission potential: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one 2020, 15, e0241536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Shahul Hameed, S.K.; Babu, G.R.; Venkataswamy, M.M.; Dinesh, P.; Kumar Bg, P.; John, D.A.; Desai, A.; Ravi, V. Descriptive epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Karnataka state, South India: Transmission dynamics of symptomatic vs. asymptomatic infections. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 32, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedzwiedz, C.L.; O'Donnell, C.A.; Jani, B.D.; Demou, E.; Ho, F.K.; Celis-Morales, C.; Nicholl, B.I.; Mair, F.S.; Welsh, P.; Sattar, N.; et al. Ethnic and socioeconomic differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection: prospective cohort study using UK Biobank. BMC medicine 2020, 18, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sze, S.; Pan, D.; Nevill, C.R.; Gray, L.J.; Martin, C.A.; Nazareth, J.; Minhas, J.S.; Divall, P.; Khunti, K.; Abrams, K.R.; Nellums, L.B.; et al. Ethnicity and clinical outcomes in COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 29, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treibel, T.A.; Manisty, C.; Burton, M.; McKnight, Á.; Lambourne, J.; Augusto, J.B.; Couto-Parada, X.; Cutino-Moguel, T.; Noursadeghi, M.; Moon, J.C. COVID-19: PCR screening of asymptomatic health-care workers at London hospital. Lancet 2020, 395, 1608–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmos, C.; Campaña, G.; Monreal, V.; Pidal, P.; Sanchez, N.; Airola, C.; Sanhueza, D.; Tapia, P.; Muñoz, A.M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in asymptomatic healthcare workers at a clinic in Chile. PloS one 2021, 16, e0245913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Li, H.; Lee, K.H.; Hong, S.H.; Kim, D.; Im, H.; Rah, W.; Kim, E.; Cha, S.; Yang, J.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Asymptomatic and Symptomatic Pediatric Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review. Medicina 2020, 56, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, G.; Morris, T.; Tudball, M. Collider bias undermines our understanding of COVID-19 disease risk and severity. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.Q.M.; Takemura, T.; Moi, M.L.; Nabeshima, T.; Nguyen, L.K.H.; Hoang, V.M.P.; Ung, T.H.T.; Le, T.T.; Nguyen, V.S.; Pham, H.Q.A.; Duong, T.N.; et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Shedding by Travelers, Vietnam. Emerging infectious diseases 2020, 26, 1624–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).