Submitted:

24 October 2023

Posted:

25 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We present a shadow removal approach grounded in unsupervised generative adversarial training.

- Our detailed architectural design addresses the challenges drones encounter in capturing shadow-free images of fasteners in real-world scenarios.

- By leveraging a custom-designed loss function, our network optimizes the quality of images restored after shadow removal.

- Through rigorous comparative and ablation tests, we validate the robustness of our algorithm, laying a foundation for future studies on identifying absent rail fasteners.

2. Materials and Methods

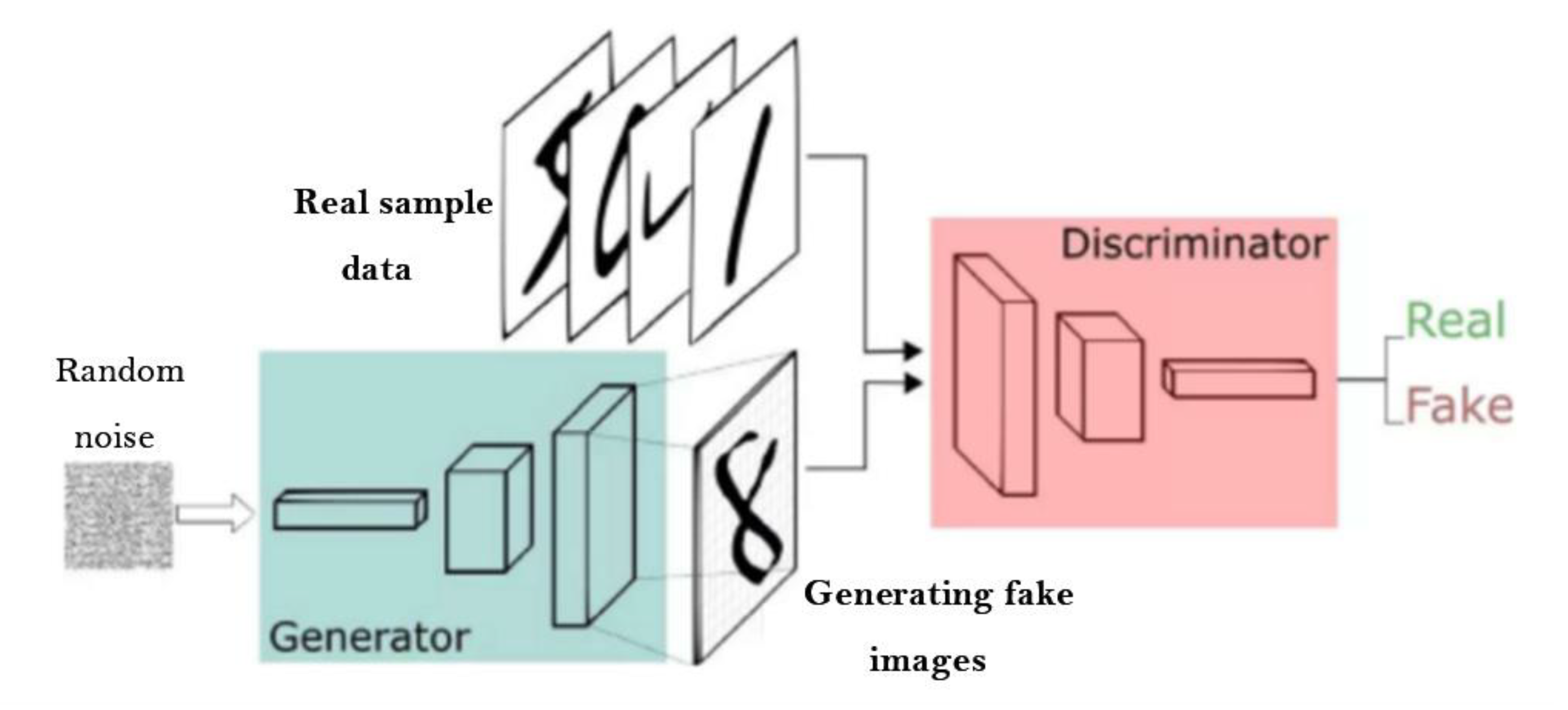

2.1. Generative Adversarial Network

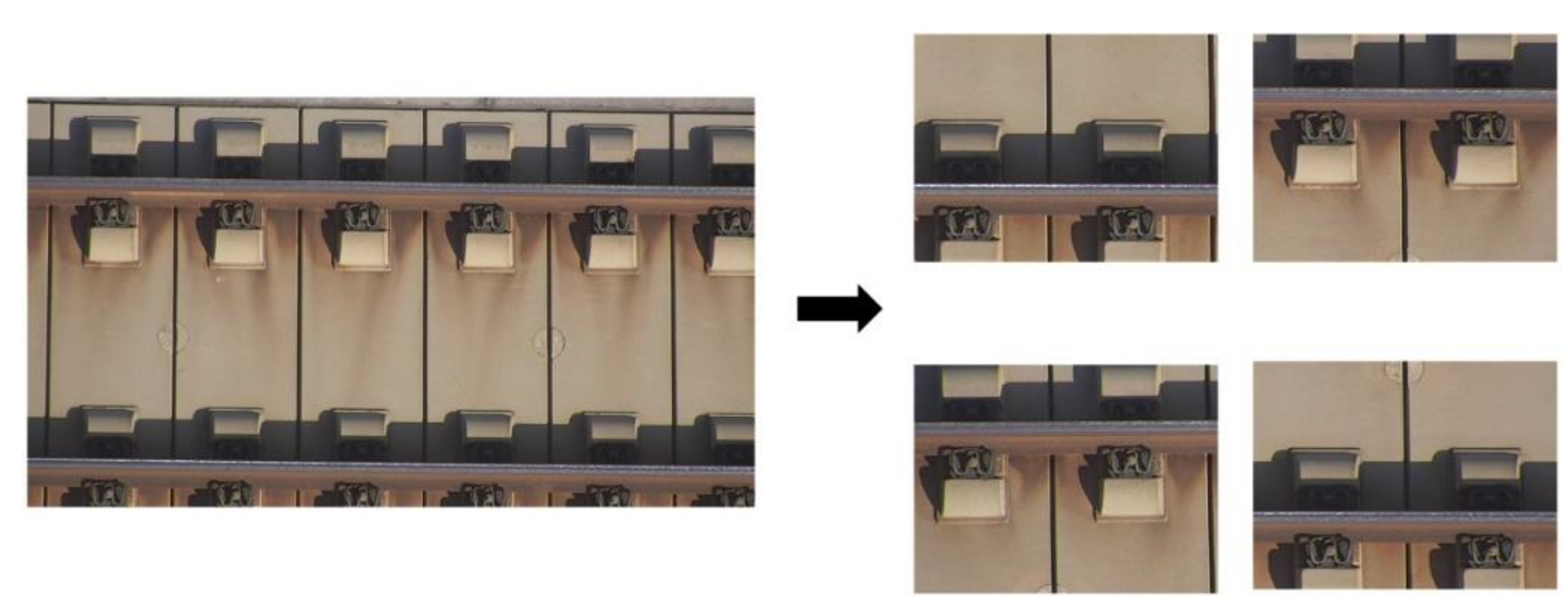

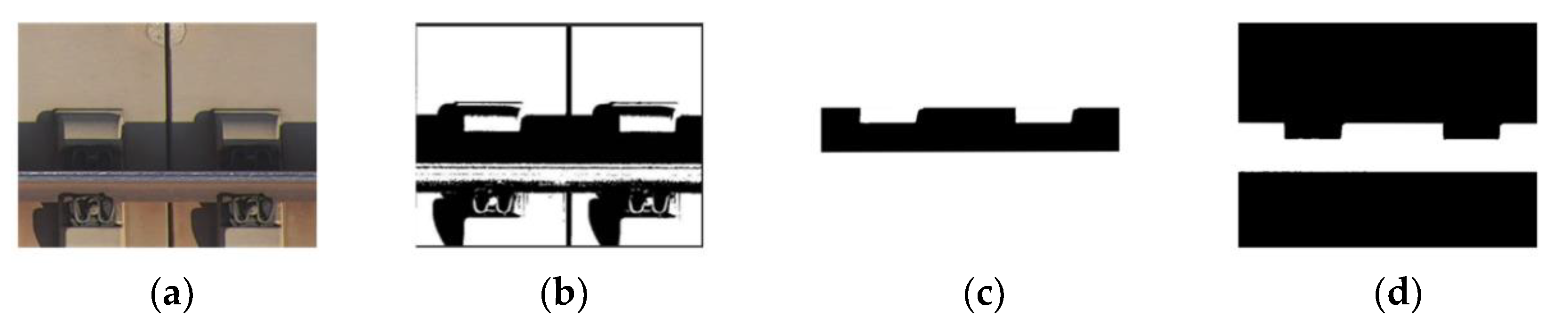

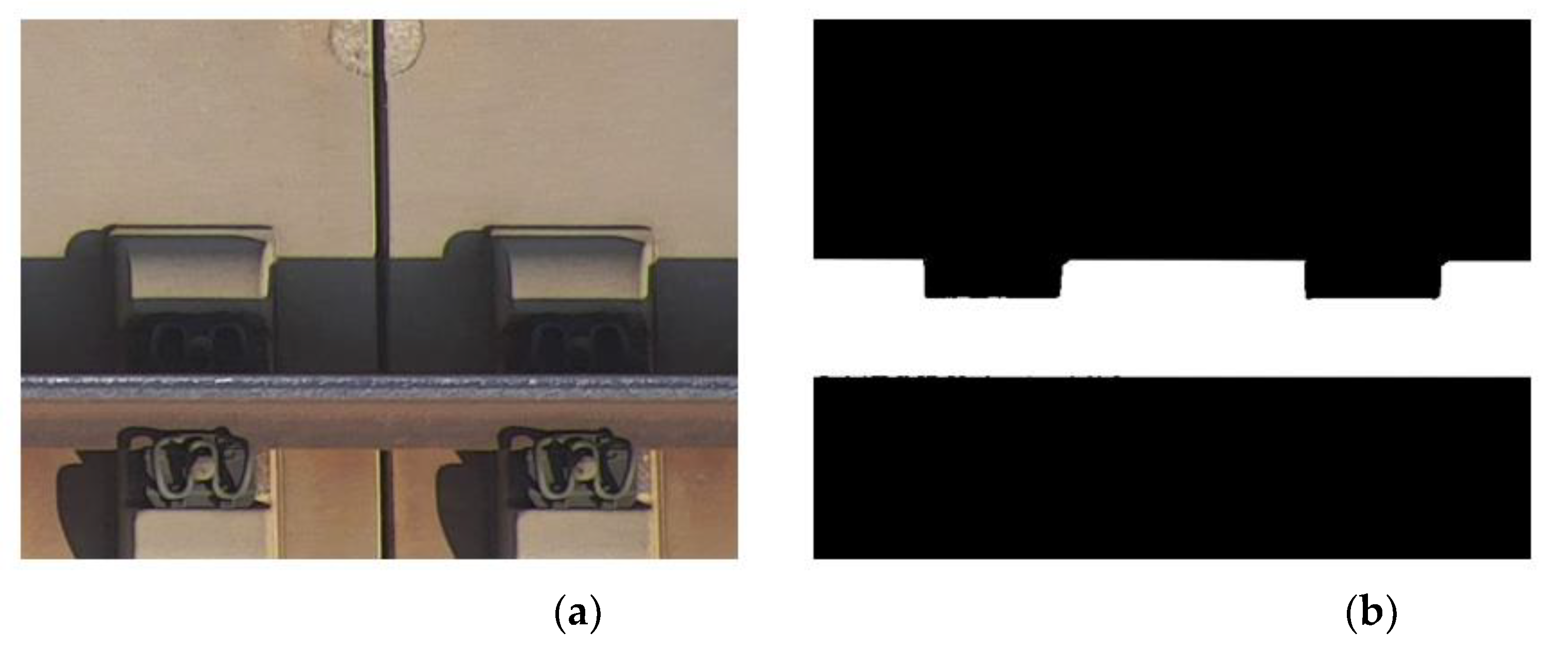

2.2. Dataset Construction

3. Shadow Removal Network Pse-ShadowNet

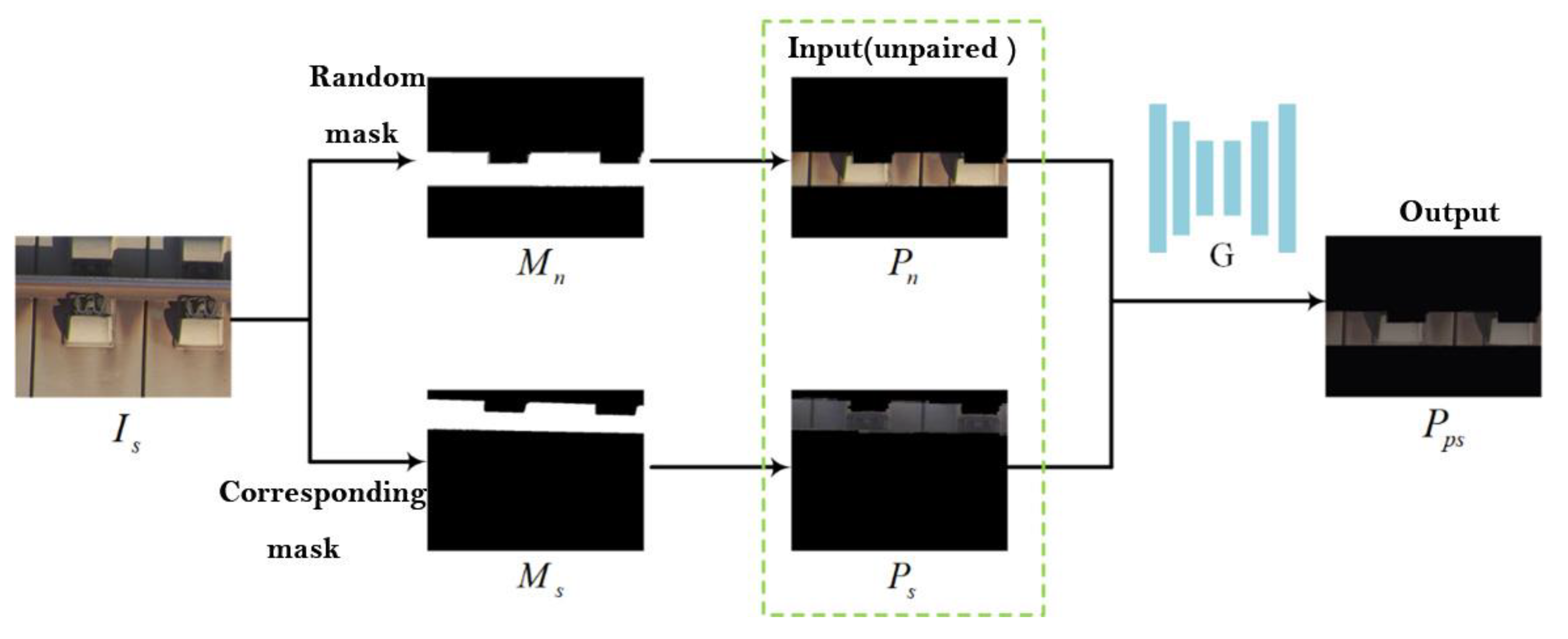

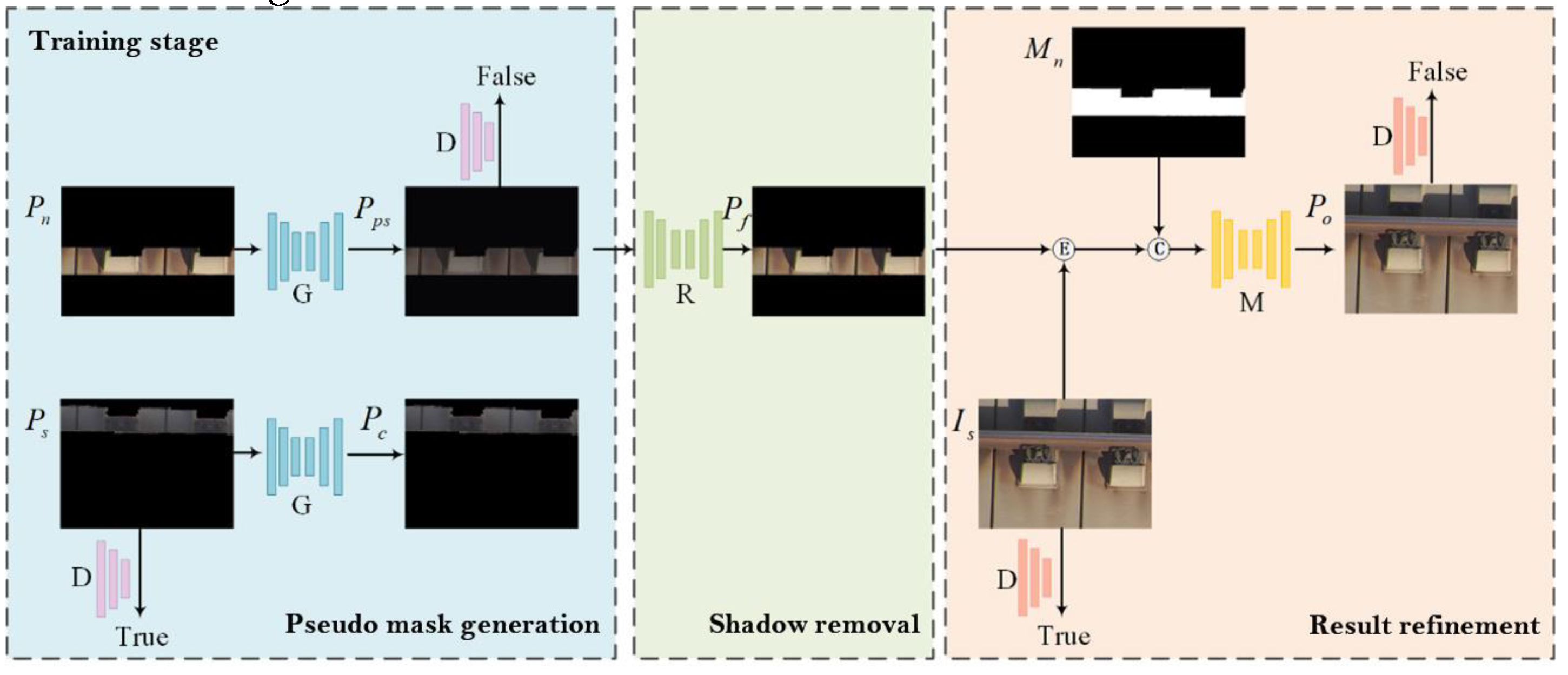

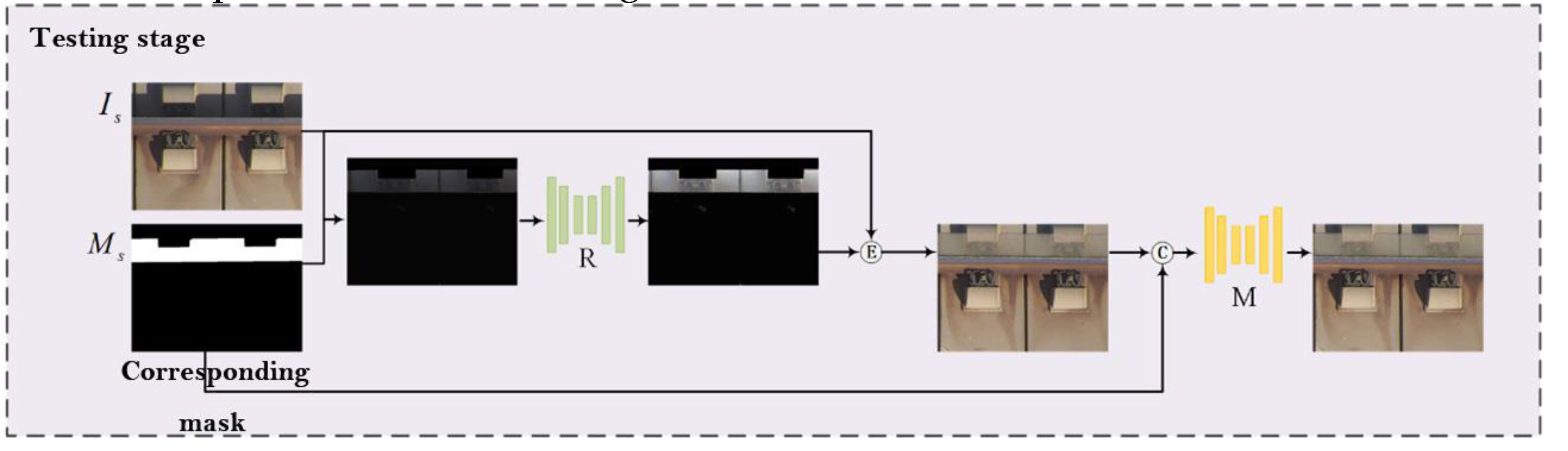

3.1. Design of Adversarial Training Network Framework

- (1)

- Pseudo mask generator

- (2)

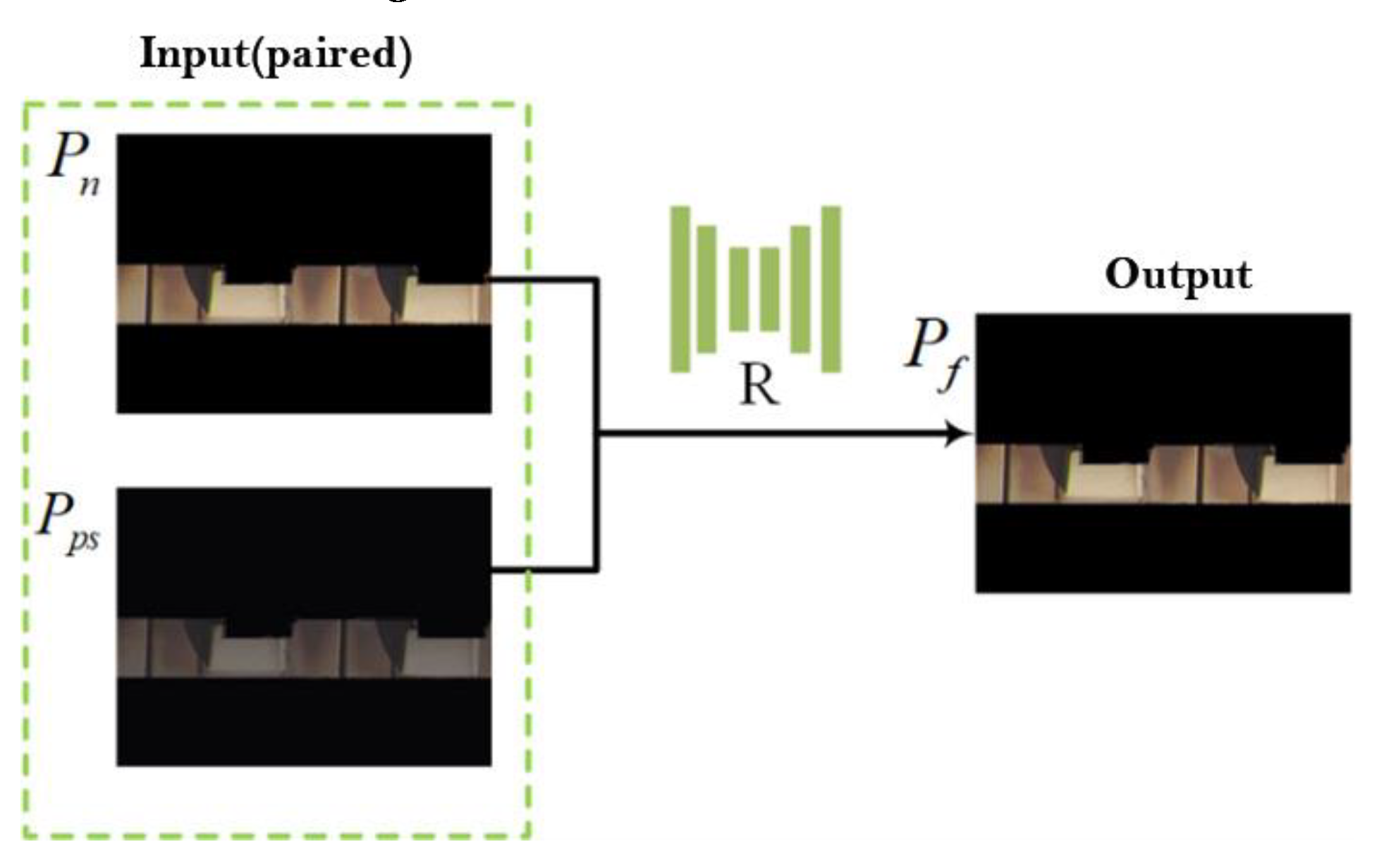

- Shadow removal network

- (3)

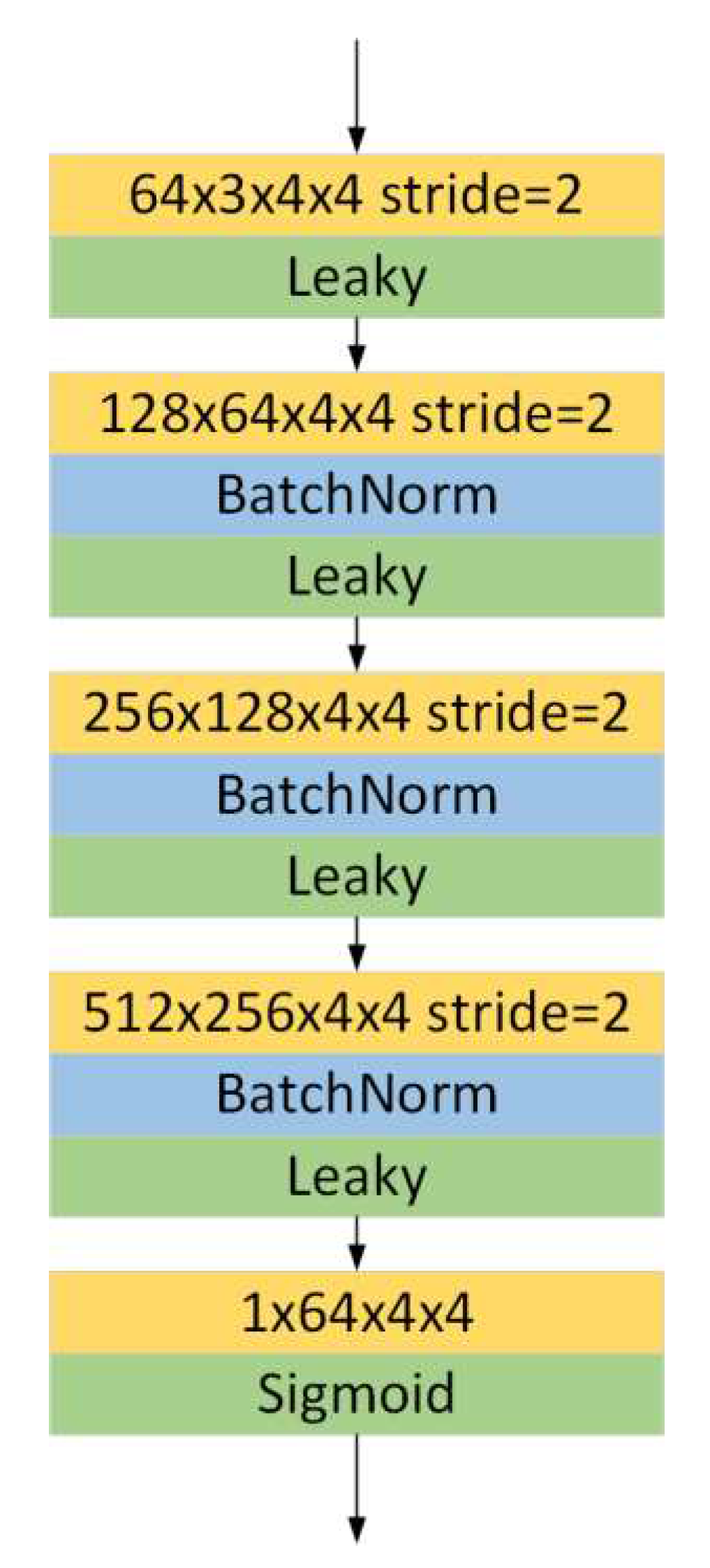

- Result refinement network

- (1)

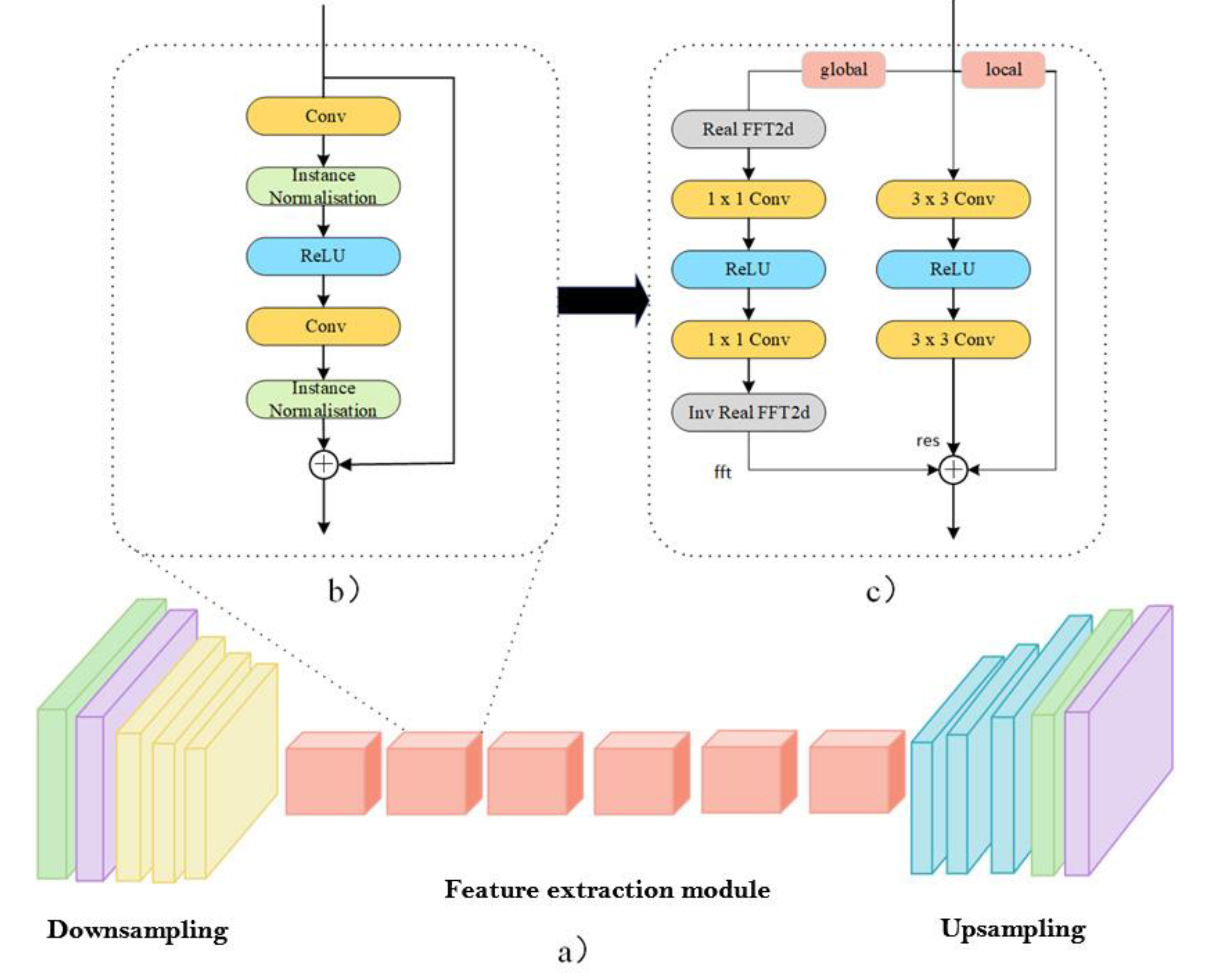

- Perform a 2D real FFT operation to obtain :

- (2)

- Concatenate the real and imaginary parts along the feature channel to obtain :

- (3)

- Apply a stack of two 1x1 convolutions with an intermediate ReLU layer to obtain :

- (4)

- Perform an inverse 2D real FFT operation to return to the spatial domain.

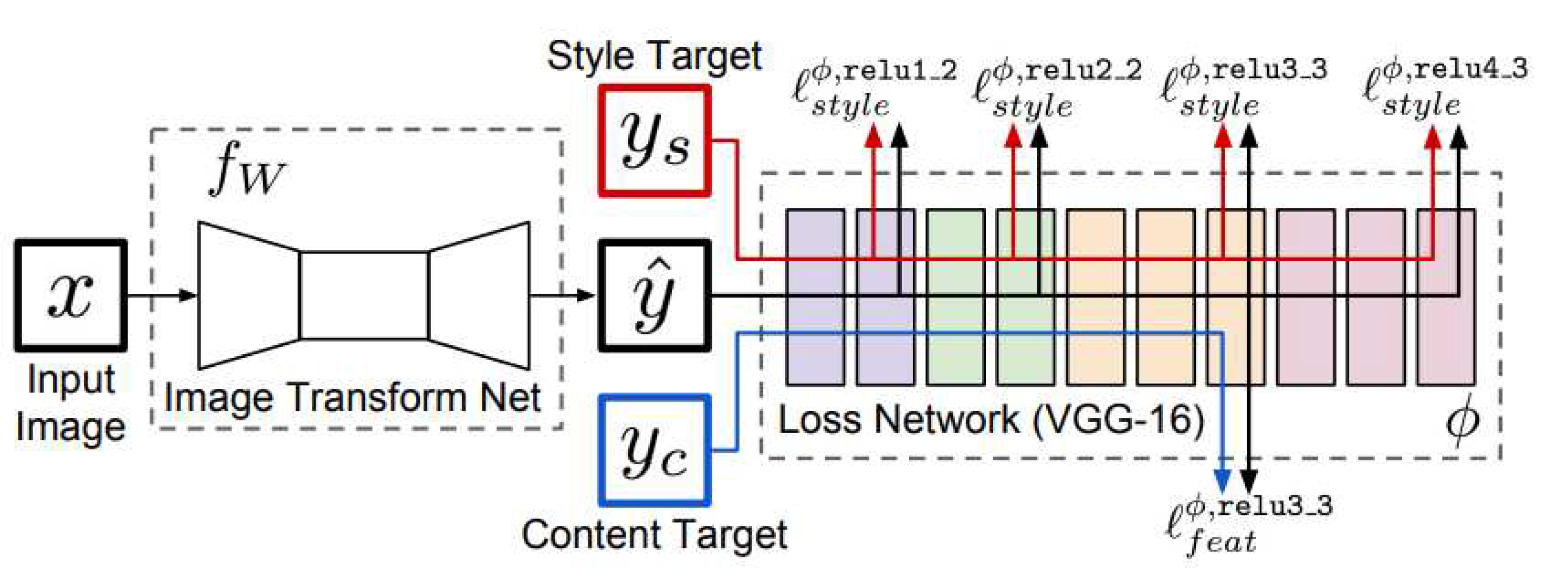

3.2. Design of Overall Weighted Loss Function

- (1)

- Pseudo mask generation sub-network

- (2)

- Shadow removal sub-network

- (3)

- Result refinement sub-network

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Setup

- (1)

- Datasets

- (2)

- Experimental environment

- (3)

- Hyperparameter settings

- (4)

- Evaluation metrics

- (1)

- RMSE

- (2)

- SSIM

- (3)

- PSNR

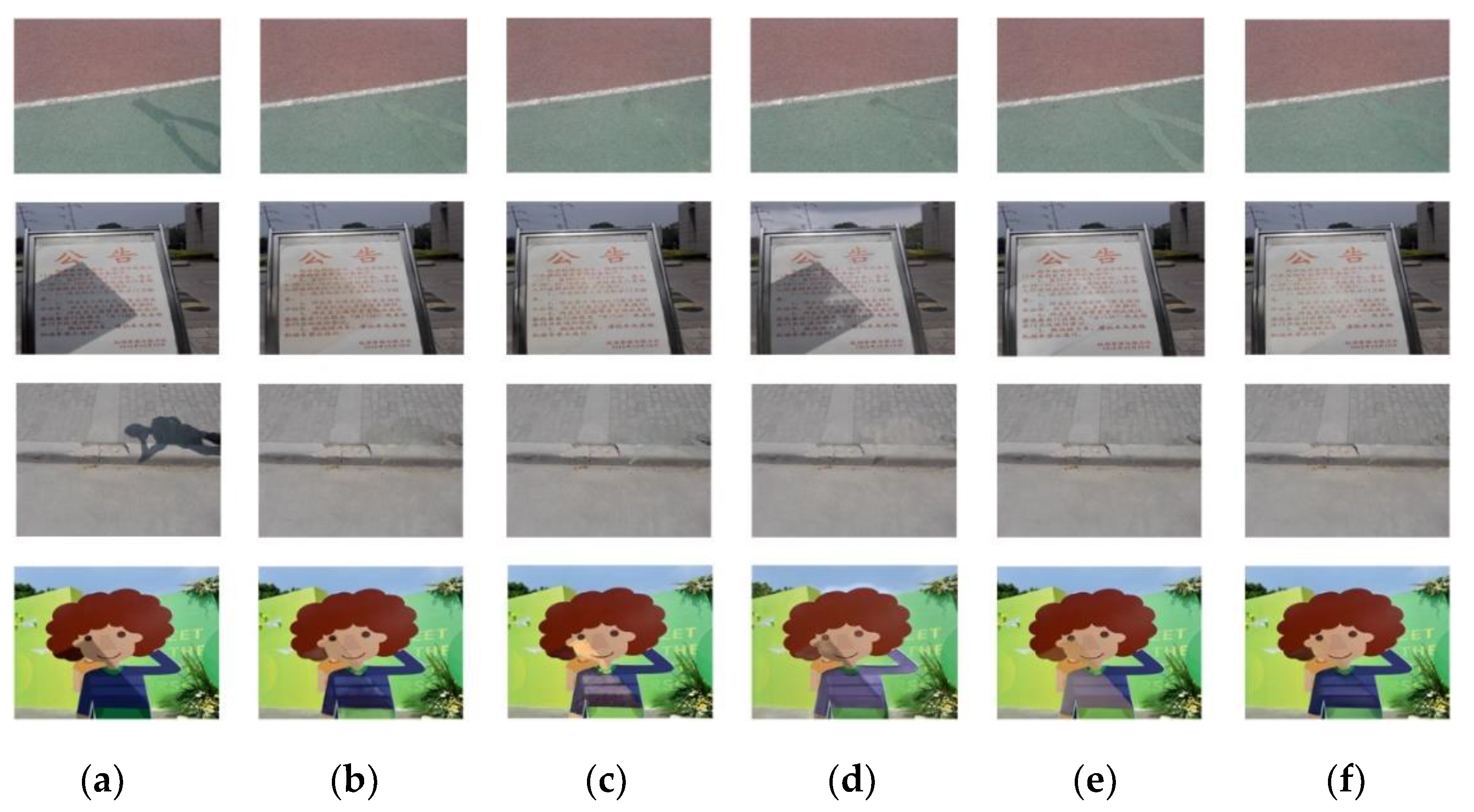

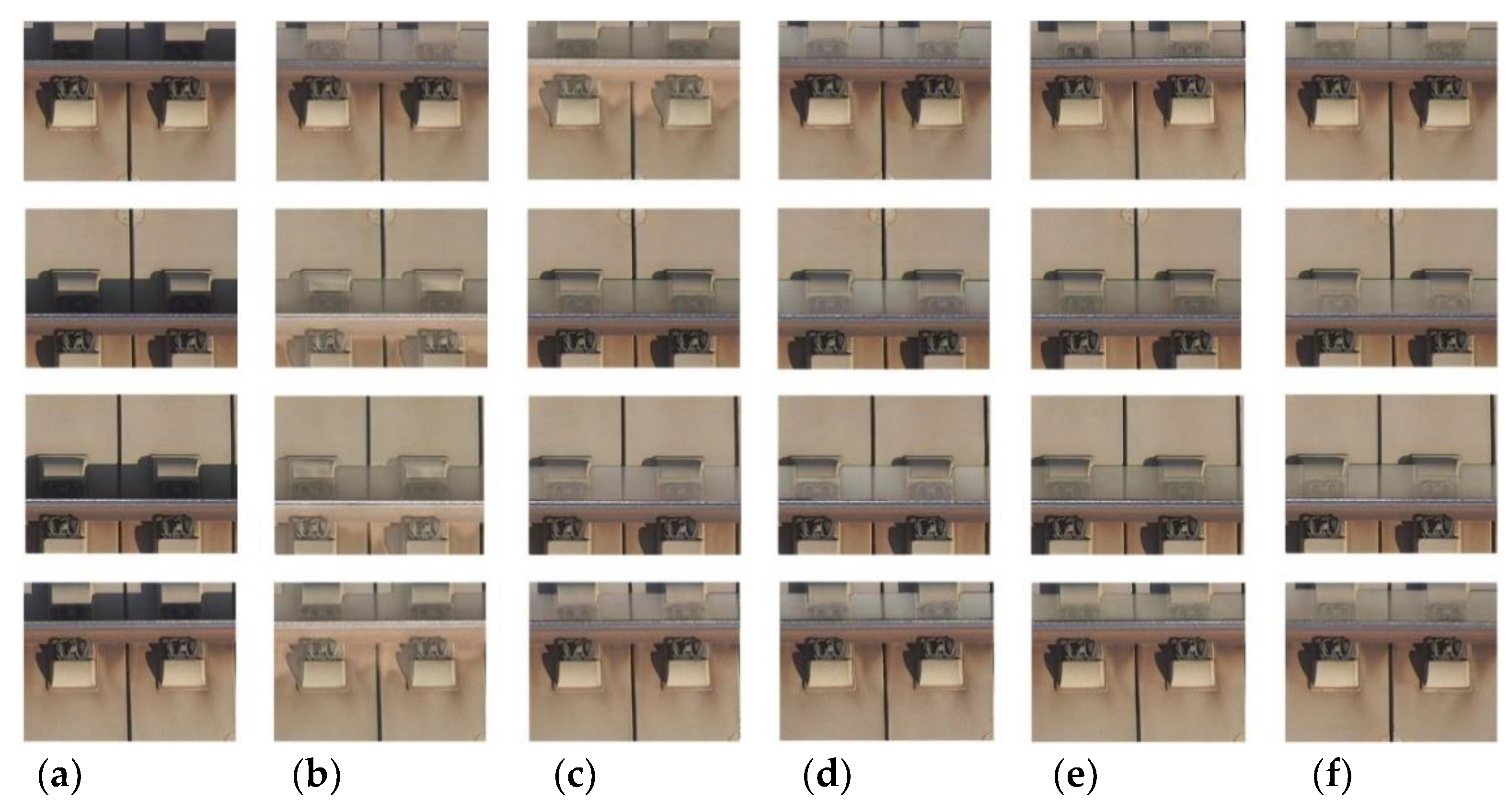

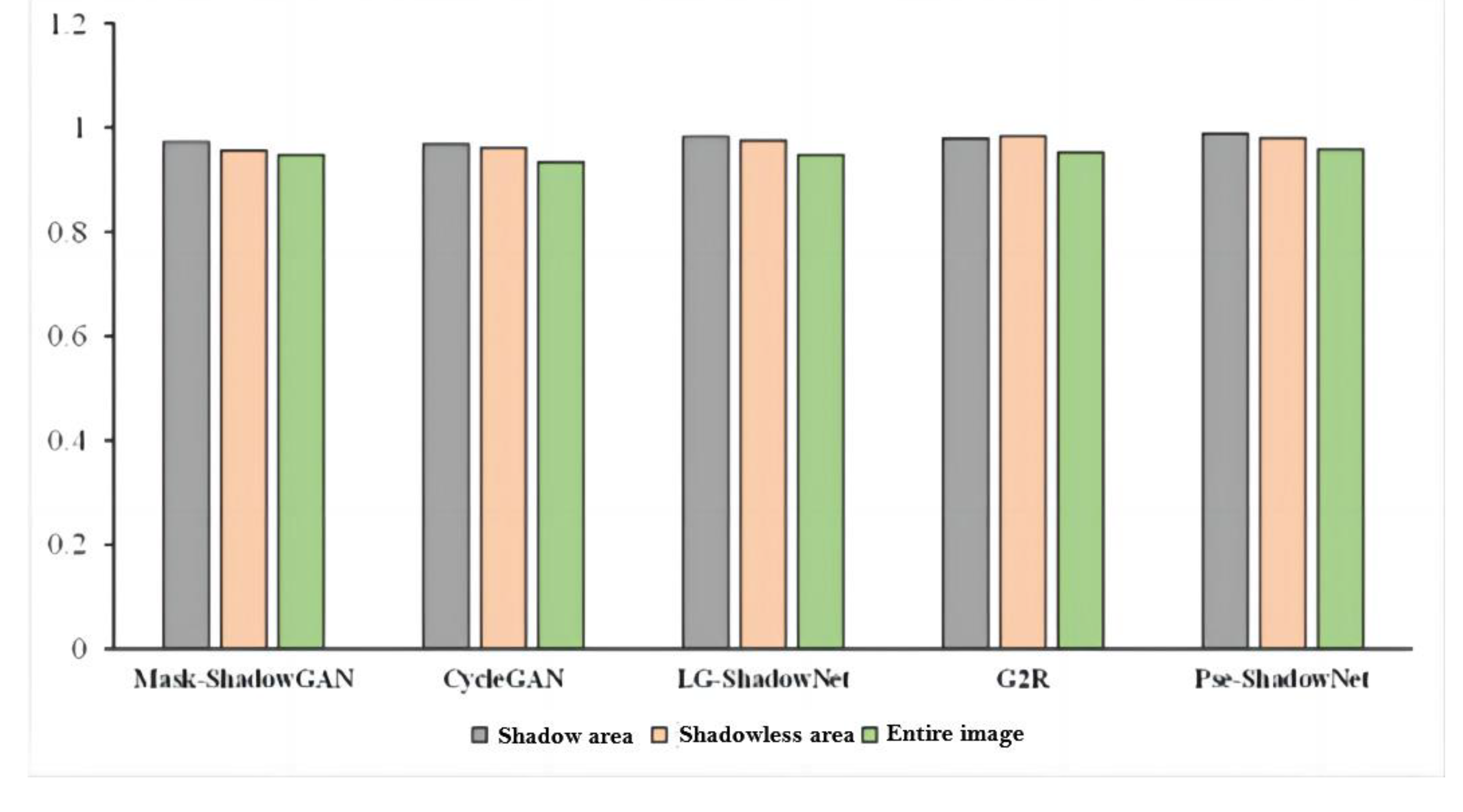

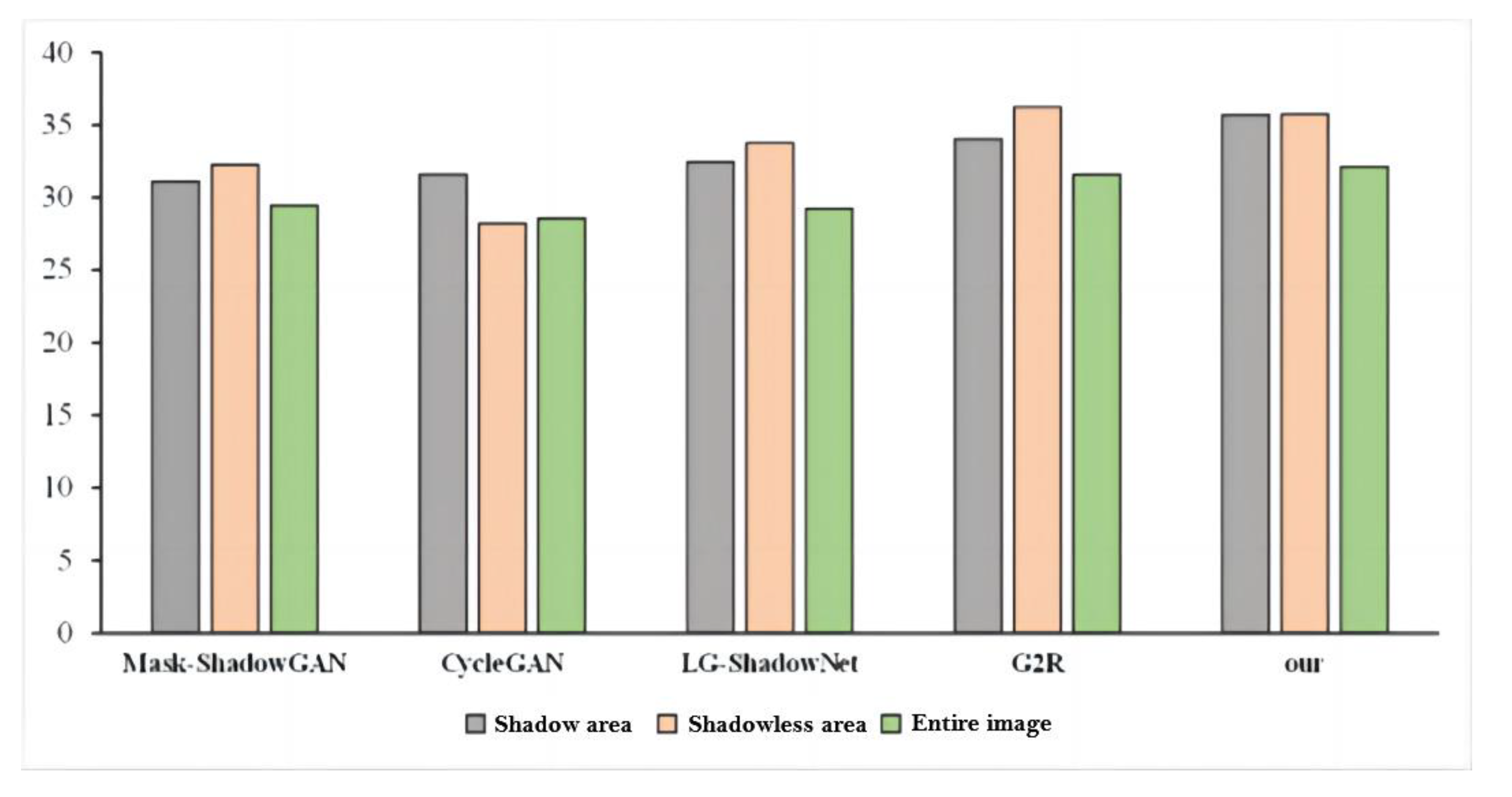

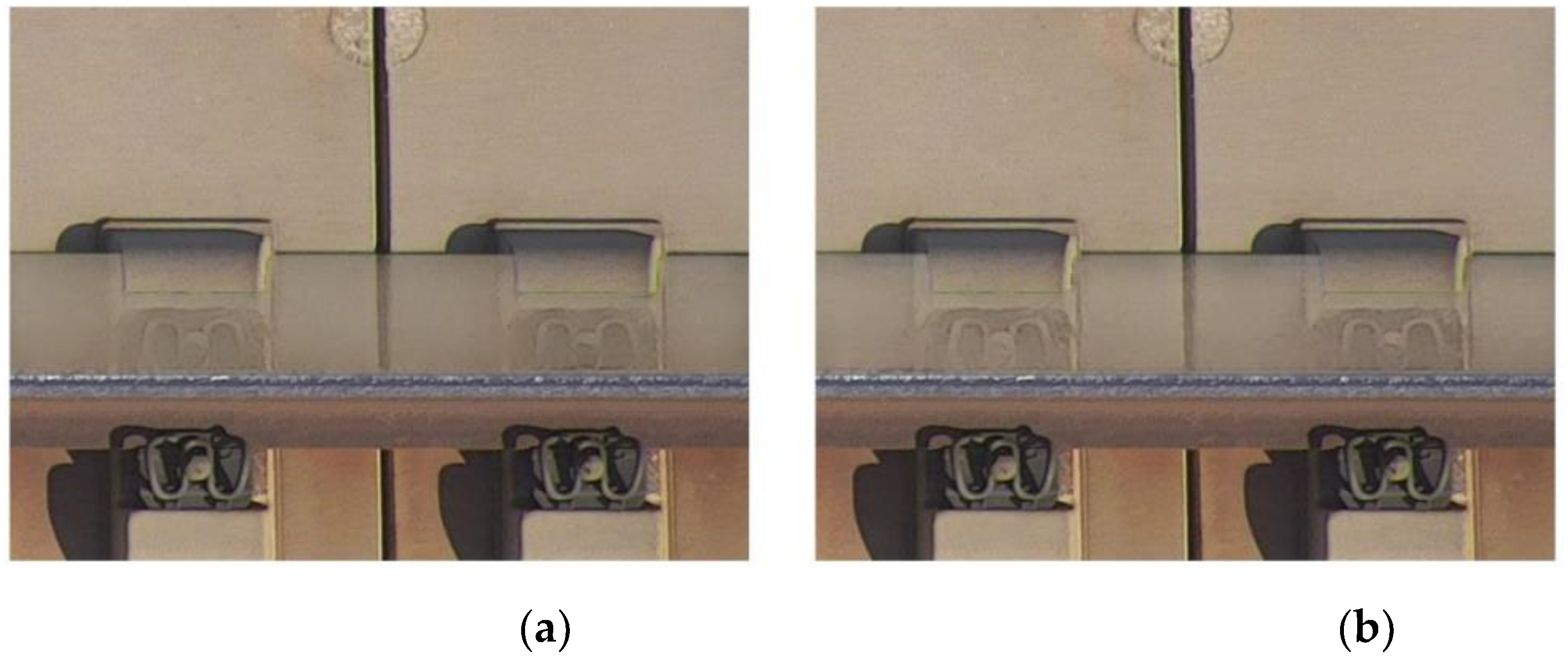

4.2. Comparative Analysis

- (1)

- Evaluation of the ISTD dataset

- (2)

- Evaluation of the fastener shadow dataset

| model | Shadow area | Shadowless area | Entire image | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | SSIM | PSNR | RMSE | SSIM | PSNR | RMSE | SSIM | PSNR | |

| Mask-ShadowGAN | 9.8 | 0.972 | 31.09 | 4.9 | 0.956 | 32.24 | 5.6 | 0.947 | 29.45 |

| CycleGAN | 10.8 | 0.968 | 31.56 | 9.3 | 0.961 | 28.17 | 9.7 | 0.934 | 28.55 |

| LG-ShadowNet | 9.8 | 0.982 | 32.45 | 3.7 | 0.975 | 33.73 | 4.3 | 0.947 | 29.22 |

| G2R | 9.3 | 0.979 | 34.02 | 2.4 | 0.983 | 36.21 | 3.6 | 0.952 | 31.54 |

| Our | 7.8 | 0.988 | 35.68 | 2.8 | 0.980 | 35.72 | 3.5 | 0.958 | 32.11 |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Xu, J.; Wang, P.; An, B.; Ma, X.; Chen, R. Damage detection of ballastless railway tracks by the impact-echo method. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Transport, Brisbane, Australia, 16-20 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson, G. D.; Hordley, S. D.; Lu, C. , Drew, M. S. On the removal of shadows from images. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2005, 28(1), 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson, G. D.; Hordley, S. D.; Drew, M. S. Removing shadows from images. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2002: 7th European Conference on Computer Vision Copenhagen, Venezia, Italy, 30 October-3 November 200.

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, W.; & Kumar, B. V. Strong shadow removal via patch-based shadow edge detection. In 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, 6-10 May 2012.

- Shor, Y.; Lischinski, D. The shadow meets the mask: Pyramid-based shadow removal. Computer Graphics Forum 2008, 27(2), 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryka, M.; Terry, M.; Brostow, G. J. Learning to remove soft shadows. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 2015, 34(5), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Tian, J.; He, S.; Tang, Y.; Lau, R. W. Deshadownet: A multi-context embedding deep network for shadow removal. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Hawaii State, USA, 21-26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A. A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 24-27 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Fu, C. W.; Heng, P. A. Mask-shadowgan: Learning to remove shadows from unpaired data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; Seoul, South Korea, 20-26 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Yin, H.; Mi, Y.; Pu, M.; Wang, S. Shadow removal by a lightness-guided network with training on unpaired data. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2021, 30, 1853–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Sharma, A.; Tan, R. T. Dc-shadownet: Single-image hard and soft shadow removal using unsupervised domain-classifier guided network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, Canada, 10-17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Le, H.; Samaras, D. From shadow segmentation to shadow removal. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020.

- Liu, Z.; Yin, H.; Wu, X.; Wu, Z.; Mi, Y.; Wang, S. From shadow generation to shadow removal. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 20-25 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cun, X.; Pun, C. M.; Shi, C. Towards ghost-free shadow removal via dual hierarchical aggregation network and shadow matting gan. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, USA, 27-28 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Zhou, C.; Guo, Q.; Juefei-Xu, F.; Yu, H. , Feng, W. ; Wang, S. Auto-exposure fusion for single-image shadow removal. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 20-25 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; , Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A. (Eds.) Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. In Neural Information Processing Systems 27: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2014, Quebec, Canada, 04-09 December 2014.

- Mao, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, Q.; Shen, W.; Wang, Y. Intriguing Findings of Frequency Selection for Image Deblurring. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington DC, USA, 27-28 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lata, K.; Dave, M.; Nishanth, K. N. Image-to-Image Translation Using Generative Adversarial Network. In 2019 3rd International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA), Tamil Nadu, India, 12-14 June 2019. 14 June.

- Johnson, J.; Alahi, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Drente, Netherlands, 09 October 2016.

- Simonyan K,; Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2014, 6, 72–89.

- Hu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Fu, C. W.; Heng, P. A. Mask-shadow gan: Learning to remove shadows from unpaired data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Korea, 20-26 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A. A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, HI, USA, 20-26 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Yin, H.; Mi, Y.; Pu, M.; Wang, S. Shadow removal by a lightness-guided network with training on unpaired data. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2021, 30, 1853–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Yin, H.; Wu, X.; Wu, Z.; Mi, Y.; Wang, S. From shadow generation to shadow removal. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 19-25 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Experimental needs | name | Configure parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware configuration | operating system | Ubuntu 18.04.5 |

| Development language |

Python3.9 | |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce GTX 3090ti | |

| Software environment | Tensorflow-gpu | 12.0 |

| Pytorch | 1.10.1 | |

| CUDA | 11.1 | |

| cuDNN | 8.0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).