Introduction

Late-onset hypogonadism (LOH) is a condition caused by the decline of testosterone with aging, and is associated with various symptoms, including physical, psychological, and sexual disturbance [

1,

2]. LUTS is one of the symptoms associated with LOH. LUTS can lead to urinary tract infection and upper urinary tract damage and can significantly decrease quality of life [

3]. Some recent studies have shown that testosterone replacement treatment (TRT) can improve male LUTS [

4]. Though LOH worsens male LUTS, most studies have investigated LUTS in LOH patients who present to a hospital [

3,

5,

6]. Until now, no large study has investigated the correlation between LOH severity and LUTS in patients who have not visited a hospital.

The Aging Male Symptoms (AMS) score, which is also validated in Japanese individuals, is widely accepted for the assessment and monitoring of symptoms of LOH; patients with an AMS score of 17-26 are not diagnosed with LOH [

7]. The international prostate symptom score (IPSS), which includes seven domains and a QOL score, is widely used to assess the symptoms of male LUTS [

8]. This questionnaire assesses voiding and storage symptoms.

The present study investigated the correlation between the severity of LOH and LUTS in Asian Japanese males of ≥40 years of age using a web-based questionnaire.

Materials & Methods

We asked a total of 2,000 Japanese male individuals to answer both the AMS and IPSS/QOL questionnaires using a web-based survey (Freeasy, ibridge, Tokyo, Japan) in August 2021. This survey was approved by the institutional review board of Yokohama City University (Yokohama, Japan) [F220900015]. In these 2,000 individuals, 500 individuals were assigned to each of the following age groups: 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, and ≥70 years. The AMS and IPSS/QOL questionnaires, which have been validated in Japanese, were answered on a website.

LOH symptoms were assessed by AMS score as no/little (17-26 points), mild (27-36 points), moderate (37-49 points), and severe (≥50 points) [

9]. LUTS was assessed by IPSS, with the severity categorized as follows: mild (0-7 points), moderate (8-19 points), and severe (20-35 points) [

9]. To compare the risk of voiding and storage dysfunction according to the severity of AMS, voiding dysfunction was assessed by the sum of IPSS Q1, Q3, Q5, and Q6, while storage dysfunction was assessed by the sum of IPSS Q2, Q4, and Q7 [

10]. Nocturia was defined by a score of ≥2 points for IPSS Question 7. We also assessed the QOL index to assess the quality of daytime life in individuals with LUTS.

Statistical Analyses

The participants’ characteristics and scores were analyzed using t-tests and chi-squared tests. A one-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the association between the AMS score and urinary symptoms. The statistical analyses were performed using the Graph Pad Prism software program (Graph Pad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). P values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Five hundred individuals in each age group (40-49 years, 50-59 years, 60-69 years, and ≥70 years) answered both the AMS and IPSS/QOL questionnaire. The distribution of the IPSS total scores, QOL scores, and AMS scores are shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

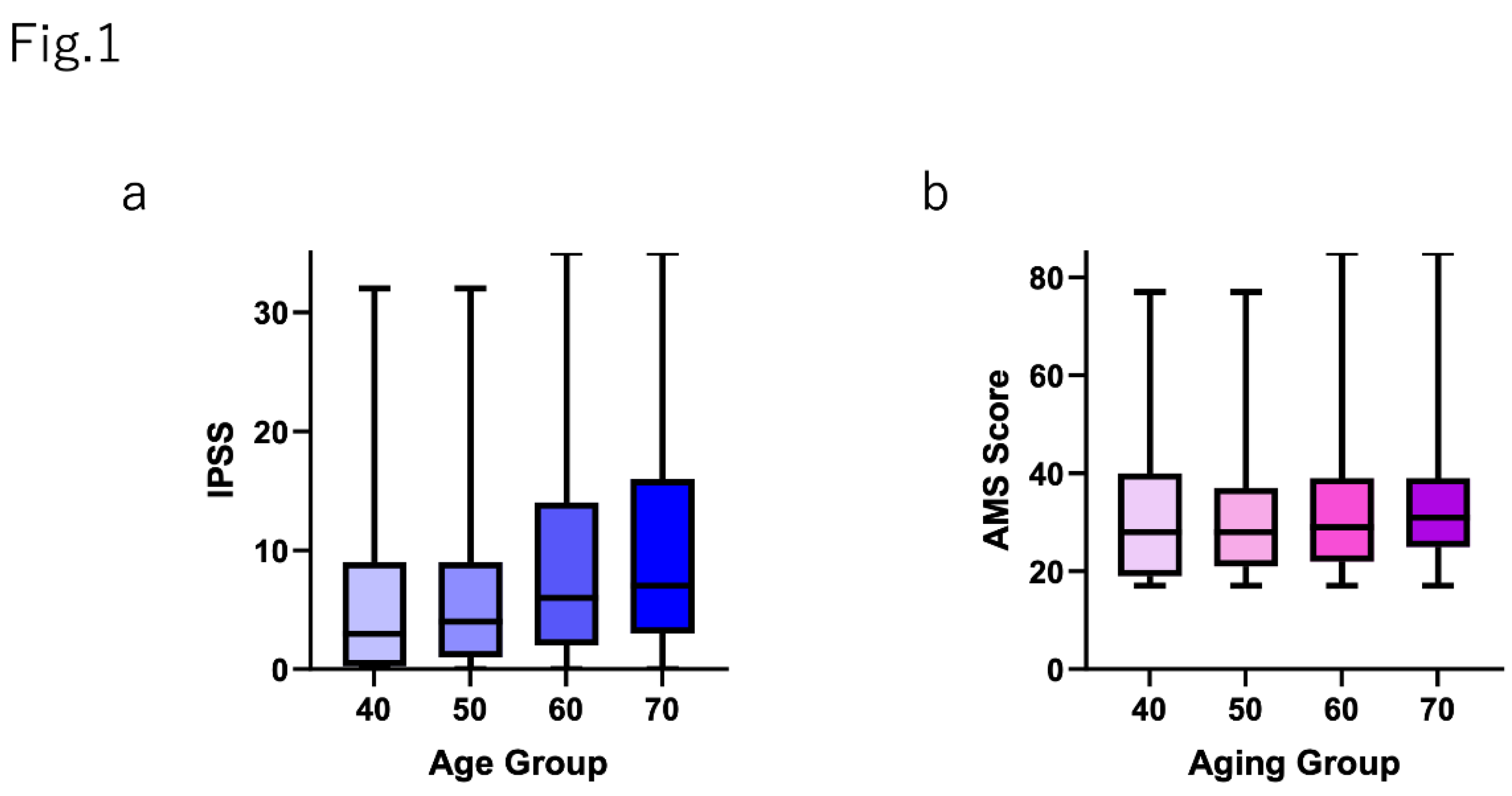

Figure 1 shows that the IPSS total score was positively correlated with aging. The IPSS total scores in each age group were as follows (shown as mean±SD): 40-49 years, 5.95±7.25; 50-59 years, 6.09±6.79; 60-69 years, 8.71±8.31; and ≥70 years, 10.14±8.90 (p<0.0001). The AMS scores (shown as mean±SD) were almost same in each age group: 40-49 years, 31.29±13.6; 50-59 years, 30.48±11.96; 60-69 years, 31.26±11.55; and ≥70 years, 32.59±11.06 (p=0.0491).

The individual IPSS scores (Q1-Q7), the IPSS total score, and the QOL index in each AMS score group are shown in

Table 1. The IPSS total score was positively correlated with the severity of AMS (shown as median [mean±SD]): no/little group, 2 (3.67±5.36); mild group, 6 (7.98±6.91); moderate group, 11 (12.49±8.63); and severe group, 16 (14.83±9.24) (p<0.0001). The QOL index was also positively correlated with the severity of AMS (shown as median [mean±SD]): no/little group, 2 (2.19±1.40); mild group, 3 (3.00±1.38); moderate group, 3.5 (3.57±1.40); and severe group, 4 (3.87±1.50) (p<0.000). Other IPSS scores, including Q7 (nocturia), were also positively correlated with the severity of AMS (

Table 1).

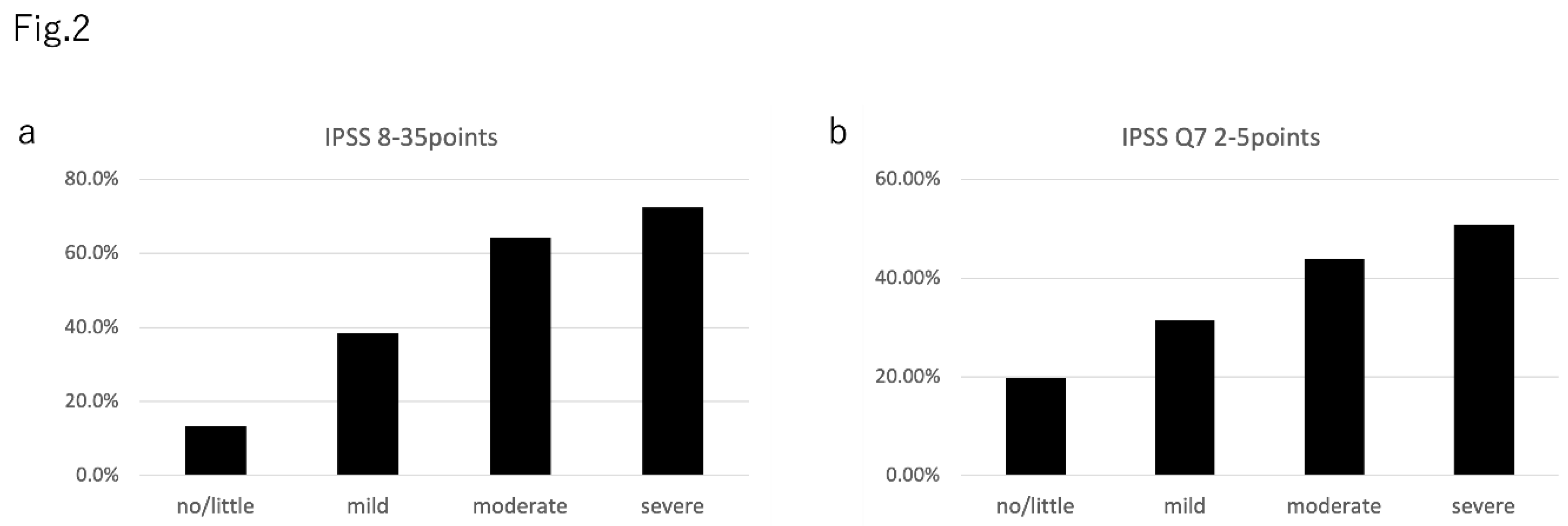

The prevalence of an IPSS total score of ≥8 in the AMS severity groups was as follows: no/little group, 13.3% (111 of 834); mild group, 38.3% (225 of 587); moderate group, 64.2% (244 of 380); severe group, 72.4% (144/199) (

Figure 2a). The prevalence of nocturia in the AMS severity groups was as follows: no/little group, 19.8% (165 of 834); mild group, 31.5% (185 of 587); moderate group, 43.9% (167 of 380); and severe group, 50.8% (101 of 199) (

Figure 2b).

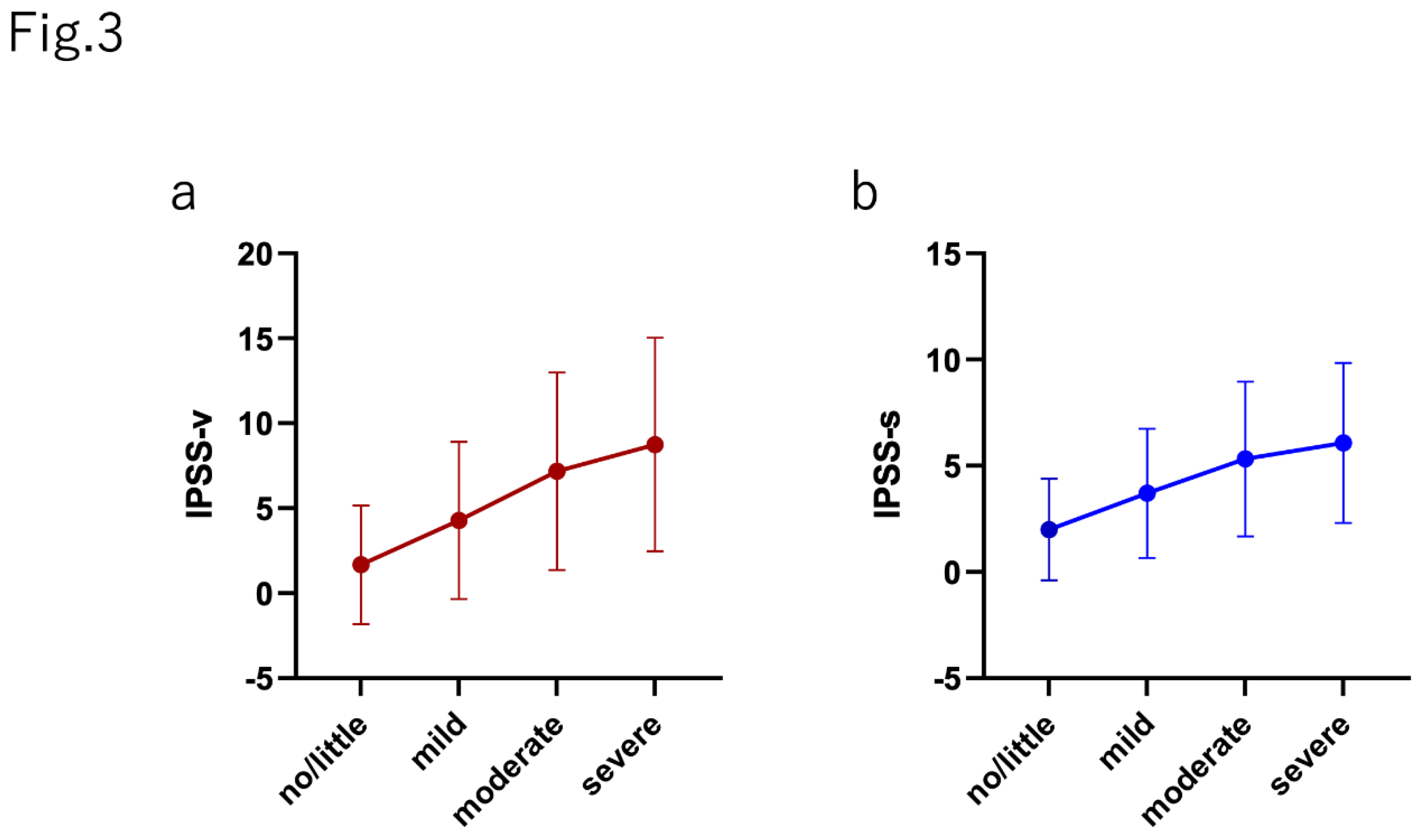

The median (mean±SD) IPSS-v score (voiding dysfunction) in each group was as follows: no/little group, 0 (1.67 ± 3.49); mild group, 3 (4.28 ± 4.68); moderate group, 6 (7.18 ± 5.81); and severe group, 9 (8.79 ± 6.29) (p>0.0001). The median (mean±SD) IPSS-s score (storage dysfunction) was as follows: no/little group, 1 (2.00 ± 2.40); mild group, 3 (3.70 ± 3.04); moderate group, 5 (5.32 ± 3.64); and severe group, 6 (6.08 ± 3.77) (p>0.0001). The relative scores of IPSS-v and IPSS-s normalized by the score in the no/little group was positively correlated with the severity of AMS (IPSS-v: mild, 2.56; moderate, 4.29; and severe, 5.23; IPSS-s: mild, 1.85; moderate, 2.66; and severe, 3.04).

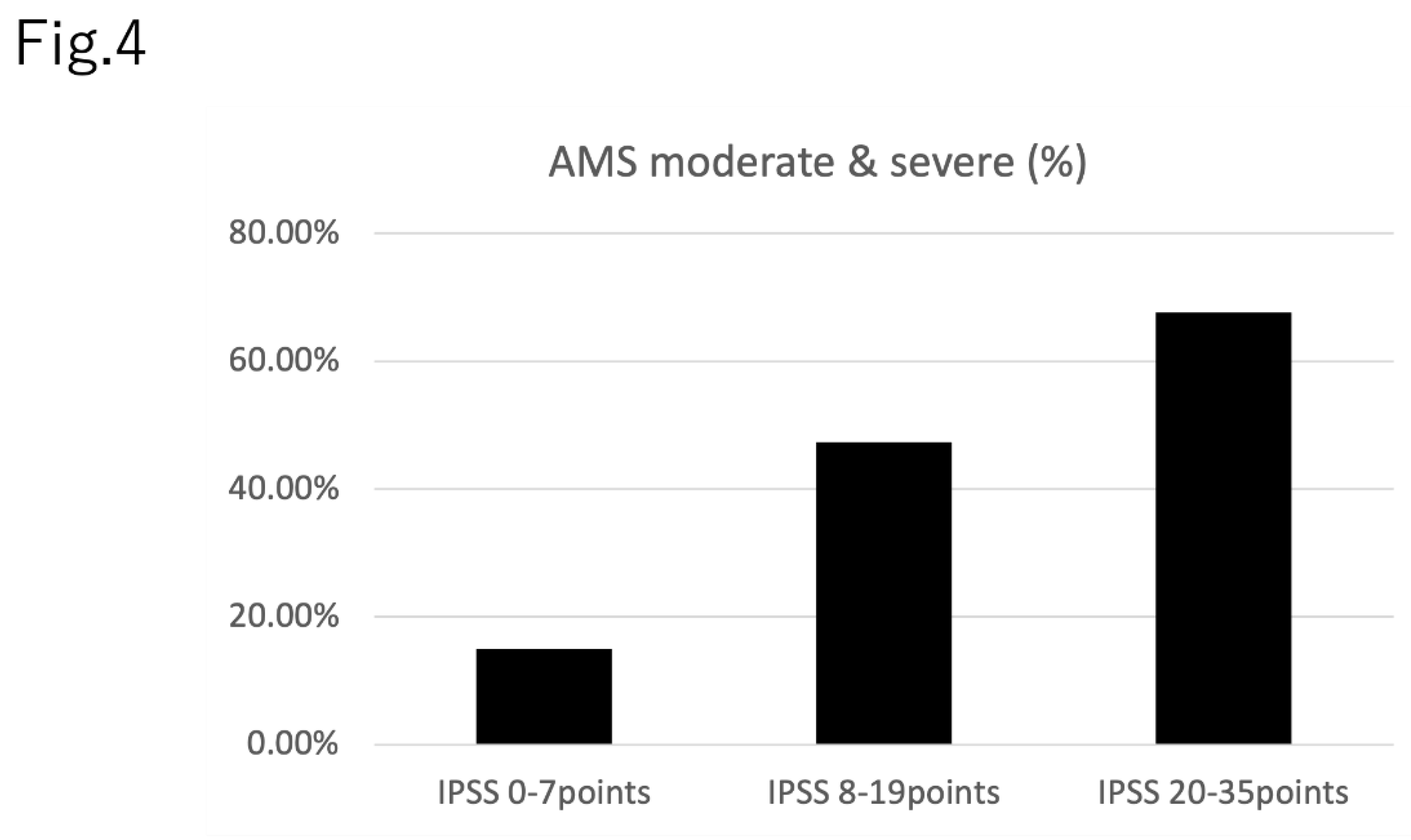

Figure 4 demonstrates the prevalence of moderate or severe AMS in each IPSS severity group: IPSS total score 0-7 points, 15.0% (191 of 1,276); IPSS total score 8-19 points, 47.4% (236 of 499); and IPSS total score 20-35 points, 67.6% (152 of 225). Raw data, including age, having a spouse or not, having children or not and household income is shown in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 3.

The correlation between both (a) voiding and (b) storage symptoms in each AMS severity group.

Figure 3.

The correlation between both (a) voiding and (b) storage symptoms in each AMS severity group.

Figure 4.

The prevalence of moderate and severe AMS in each IPSS score group.

Figure 4.

The prevalence of moderate and severe AMS in each IPSS score group.

Discussion

The present study revealed that patients with higher AMS scores showed a higher prevalence of LUTS and nocturia. These results also supported the previous studies that reported that LOH symptoms worsened urinary symptoms [

5]. Most previous studies examined patients with LOH symptoms who visited presented hospitals. The present study assessed all individuals, including individuals without symptoms. This is the largest study to date to assess the correlation between LUTS and LOH symptoms.

The detailed mechanism underlying the association between LOH and LUTS is still unknown. However, one possibility is that testosterone regulates nitric oxide (NO) production and that decreased testosterone resulted in lower NO production. Decreasing NO increases smooth muscle and the pelvic muscle tone, which worsens LUTS [

6,

11]. Amano et al. reported that patients with LOH suffered LUTS, especially voiding symptoms [

1,

12]. The present study also supported the previous study, in that a stronger correlation was observed between the severity of AMS and the worsening of voiding symptoms in comparison to the severity of AMS and the worsening of storage symptoms.

This study also supported the previous studies as LUTS worsened with as the severity of LOH symptoms increased. In daily clinical practice, urologists sometimes experience cases of male patients with LUTS whose symptoms are not improved by treatment, including alpha-1 blockers and 5-alpha reductase, and endourological surgery. Based on the evidence to support the efficacy of testosterone replacement treatment for the improvement of LUTS in patients with LOH symptoms, ruling out LOH symptoms using the AMS score may be useful for determining appropriate treatment strategies for male patients with LUTS.

The present study was associated with several limitations. Firstly, we assessed LOH symptoms based on the AMS questionnaire and did not examine the serum testosterone levels. Thus, we did not determine the clinical diagnosis. AMS is widely used to assess the severity of LOH in daily clinical practice. Thus, a large number of individuals were assessed in this short-term study. Secondly, this study did not assess other factors that may affect LUTS, including smoking, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension [

13,

14]. Further studies, that include the evaluation of detailed information about the patient’s present status, past history, and other factors are needed.

Conclusions

Individuals with higher AMS scores, which reflect severe LOH symptoms, showed a higher risk of nocturia and LUTS.

References

- Amano, T.; Imao, T.; Takemae, K.; Iwamoto, T.; Nakanome, M. Testosterone replacement therapy by testosterone ointment relieves lower urinary tract symptoms in late onset hypogonadism patients. Aging Male. 2010, 13, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieschlag E, Swerdloff R, Behre HM, Gooren LJ, Kaufman JM, Legros JJ; et al. Investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males. Aging Male. 2005, 8, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassin, D.J.; El Douaihy, Y.; Yassin, A.A.; Kashanian, J.; Shabsigh, R.; Hammerer, P.G. Lower urinary tract symptoms improve with testosterone replacement therapy in men with late-onset hypogonadism: 5-year prospective, observational and longitudinal registry study. World J Urol. 2014, 32, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigehara, K.; Namiki, M. Late-onset hypogonadism syndrome and lower urinary tract symptoms. Korean J Urol. 2011, 52, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada K, Miyake H, Ishida T, Sumii K, Enatsu N, Chiba K; et al. Improved Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Associated With Testosterone Replacement Therapy in Japanese Men With Late-Onset Hypogonadism. Am J Mens Health. 2018, 12, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baas, W.; Kohler, T.S. Testosterone replacement therapy and voiding dysfunction. Transl Androl Urol. 2016, 5, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thwaites, J.H. Practical aspects of drug treatment in elderly patients with mobility problems. Drugs Aging. 1999, 14, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, T.; Ito, H.; Uemura, H. The impact of smoking on male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 20212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinemann LA, Saad F, Zimmermann T, Novak A, Myon E, Badia X; et al. The Aging Males' Symptoms (AMS) scale: Update and compilation of international versions. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becher, E.; Roehrborn, C.G.; Siami, P.; Gagnier, R.P.; Wilson, T.H.; Montorsi, F. The effects of dutasteride, tamsulosin, and the combination on storage and voiding in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic enlargement: 2-year results from the Combination of Avodart and Tamsulosin study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009, 12, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao C, Kim SH, Lee SW, Jeon JH, Kang KK, Choi SB; et al. Activity of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 2011, 107, 1943–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, T.I.T.; Takemae, K. Lower urinary tract symptom in patients with late-onset hypogonadism. Jpn J Impotence Res. 2009, 24, 359–365. [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara, T.; Ito, H.; Yao, M.; Uemura, H. Impact of smoking habit on overactive bladder symptoms and incontinence in women. Int J Urol. 2020, 27, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, T.; Ninomiya, S.; Tsutsumi, S.; Ito, H.; Yao, M.; Uemura, H. Impact of depression on overactive bladder. Int J Urol. 2021, 28, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).