1. Introduction

The dynamic interaction between soil and foundation is a complex phenomenon that poses significant challenges to geotechnical engineers. This challenge is especially pronounced when dealing with extreme loading conditions, material nonlinearity, changing boundary conditions, and large deformations common in dynamic pile-soil interaction under impact loading. Despite advancements in computational methodologies, accurately simulating this event remains daunting.

The Updated Lagrangian Finite Element Method (UL-FEM) has been a cornerstone in this computational landscape, yet it is not without its limitations. While UL-FEM has been instrumental in solving dynamic pile-soil interaction problems across various applications, it suffers from significant drawbacks. These include severe mesh distortions and element entanglements, often leading to non-physical and inaccurate results. Such issues are particularly prevalent in scenarios involving large deformations, such as "rigid" or "short" piles embedded in soil subjected to impact loading.

Four principal computational methodologies have gained prominence in the realm of simulating laterally impacted piles embedded in soil. These are the lumped parameter approach [

1,

2], the subgrade reaction method [

3,

4], the modified subgrade reaction approach [

5,

6], and the direct method [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. While the first three methodologies rely on nonlinear springs, dampers, and lumped soil mass to simulate the dynamic soil behavior, the direct method employs a continuum Lagrangian solid elements, adhering to specific constitutive laws. However, all these approaches bear intrinsic limitations. The abstraction of soil to nonlinear springs, dampers, and lumped mass fails to capture its complex particulate-continuum nature and often overlooks critical soil attributes, such as dynamic stress-strain behavior of soil, three-dimensional large plastic deformation or flow of soil around the pile, volumetric expansion behavior of the soil, inertial and strain rate effects on the behavior of soil, hydro-mechanical effects (fully saturated vs. unsaturated/partially saturated soil), and the dynamic shear interaction between the pile and the surrounding soil. This leaves these methods less reliable when complex impact loading conditions, multiphysics situations, complex pile geometries, and various terrain conditions (sloped vs. level terrain) are present.

Moreover, although the direct method excels in simulating soil responses under small deformations, it struggles with mesh distortions and element entanglements during larger deformations, particularly for simulations that involve "rigid" or "short" piles. Simulating pile-soil systems using a direct approach requires expertise in computational modeling of geotechnical problems as well as the use and calibration of soil constitutive models.

In addition, previous research has disproportionately focused on inelastic pile deformations during pile-soil impacts, potentially obscuring soil behavior's contribution to the overall system dynamics. This leaves several unresolved questions, especially about the soil mechanics that pile failure mechanisms might overshadow. Given these limitations and gaps in understanding, an urgent need is to develop an improved and computationally efficient methodology. Specifically, computational frameworks engineered for large deformation problems appear to be promising avenues for enhanced modeling of dynamic pile-soil interactions under impact scenarios, thus constituting an important frontier for deepening the understanding of the governing physics of pile-soil systems under extreme loading conditions.

In recent times, mesh-free particle techniques, such as Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) [

14,

15] and the Material Point Method (MPM) [

16,

17], have been recognized for their utility in modeling soil-structure interactions that encompass large soil deformations. However, the significant computational demands of these methods pose challenges for simulating large-scale pile-soil systems, especially under vehicular impacts. On the other hand, the Discrete Element Method (DEM) [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] emerges as an alternative, though its granular-scale methodology requires considerable computational resources. Moreover, this granularity often necessitates introducing scaling factors to efficiently model large soil volumes using fewer particles [

19,

20]. Notably, many prevalent MPM and DEM software, both open-source and proprietary, are not tailored for dynamic soil-structure scenarios associated with vehicular collisions.

Addressing this gap, this study presents an enhanced and computationally efficient approach—termed the erosion method—to model dynamic pile-soil interactions under impact loading. This method augments UL-FEM with an erosion algorithm to address the large deformations in granular soils around embedded piles during lateral vehicular impact events. To ensure the robustness and reliability of the erosion method, this study developed full-scale, mechanics-based computational models and validated them against field-scale physical impact tests.

This research aims to formulate a computationally efficient, large-deformation soil modeling methodology for use in nonlinear finite element analysis platforms, such as LS-DYNA [

23,

24]. This improved simulation method is pivotal for accurate simulations of soil-embedded barrier and containment systems, including W-beam and thrie-beam guardrail systems and approach guardrail transitions (AGTs), under vehicular impacts. The main function of these barrier systems is to safely contain and redirect errant vehicles. The fulfillment of these requirements greatly depends on the dynamic pile-soil interaction under impact events, which influences the energy dissipation capability of the barrier systems. This study also examined the influence of soil mesh density and pattern on the results of simulated pile-soil systems under lateral impacts. Initial analyses targeted the identification of mesh densities capable of capturing the soil’s large deformation and plastic flow dynamics during pile impacts. Subsequent investigations pivoted toward examining the effects of soil domain sizes and boundary condition on the dynamic response of pile-soil system. The intent was to investigate model response by varying domain sizes and boundary conditions and develop guidelines for optimizing these parameters for enhanced accuracy and efficiency in pile-soil impact simulations.

2. Element Erosion Technique

The UL-FEM method employs fixed-mass elements wherein the mesh attached to the material also deforms when subjected to deformations. This results in severe mesh distortions for dynamic, large-deformation problems, such as vehicle impacts into pile-soil systems. Consequently, this problem introduces numerical instabilities, slows the calculations, and sometimes terminates the computation. In order to overcome these difficulties, the UL-FEM hydrocodes use an element erosion technique that deletes severely distorted elements to enable the computation to continue. Element erosion thresholds are set to avoid deleting the soil elements until they are severely damaged, and their strength and mass are no longer likely to affect the physics of the problem.

Although the element erosion algorithm does not simulate the real physics of the pile-soil impact problem, it is a convenient numerical technique to avoid numerical problems associated with large soil deformations due to extreme loading conditions. Severe mesh distortion produces three major problems for geotechnical engineering applications that involve large and rapid deformation of soils. Firstly, the soil elements can invert, which results in negative Jacobian or negative volume, causing most hydrocodes to terminate the computation. Secondly, severe distortion produces errors in the evaluation of the soil constitutive equation, specifically when the soil element undergoes rapid deformation. Thirdly, it reduces the time step, which results in impractical or extremely long CPU time as the time step is computed from the smallest element dimension.

Different element erosion criteria have often been used to model and analyze materials and structures under dynamic impact loading. These criteria are classified based on the variable that deletes severely distorted elements from the computation, such as strain-based [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], stress-based [

31,

32], and damage-based criteria [

33,

34]. Defining proper erosion characteristics is important in simulating dynamic pile-soil interaction under impact loading. If the soil elements are deleted too soon, the soil may offer less resistance to the pile impact, making the pile move farther into the soil with minimal resistance provided by the soil. On the other hand, if the failure strain or stress is set too high, soil elements may be severely distorted, reducing the computation time step and, in some cases, leading to the termination of the simulation. Therefore, choosing element deletion values is typically a trade-off between preventing deletion for as long as possible and not sacrificing accuracy or computational cost due to the element distortion.

Among the various element erosion criteria, the damage-based criterion is associated with stiffness degradation of the material, making it physically sound and adequate for modeling large deformation of geomaterials [

35]. However, a continuum damage model should be incorporated into the soil constitutive model to implement the damage-based erosion criterion for deleting severely distorted soil elements. Since the soil material model used in this study includes a continuum damage model, utilizing a damage-based element erosion criterion is relatively straightforward.

3. Constitutive Models

The choice of proper constitutive models that can account for the critical behavior of soil and pile and calibrating input parameters under dynamic impact environments is crucial to accurately model and investigate the dynamics of vehicle impacts into piles embedded in soil. This section details the prevailing constitutive model used for modeling the impact behavior of the soil and steel (pile) material for modeling and simulating dynamic pile-soil interaction problems using the erosion method.

3.1. Granular (MASH strong) soil

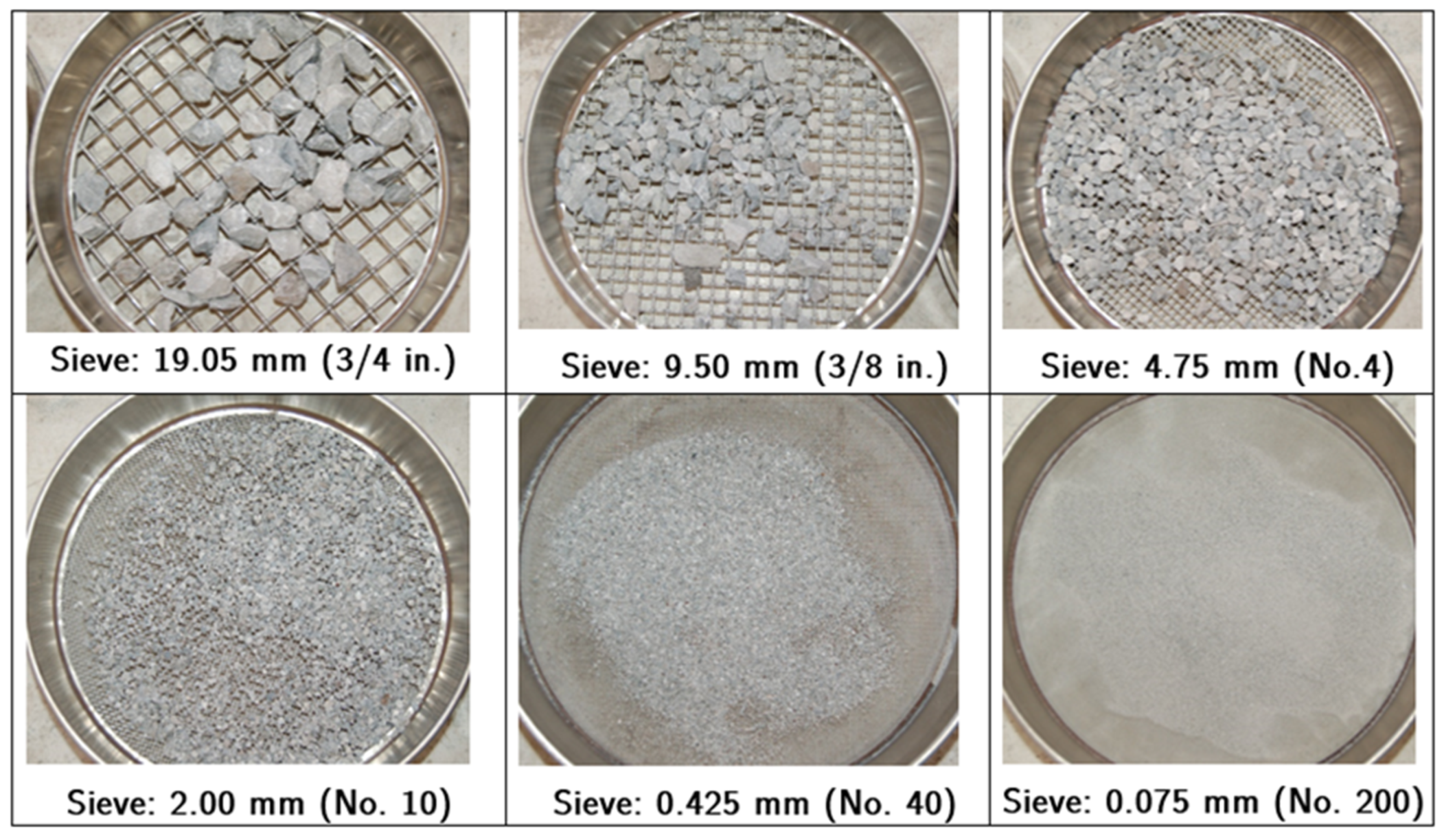

In accordance with the stringent protocols governing soil-embedded barriers and containment systems crash tests, steel piles are frequently embedded in granular soils, hereafter referred to as granular (MASH strong) soil. As shown in

Figure 1, the granular (MASH strong) soil exhibits heterogeneity in grain sizes, characterized by a spectrum of angular to subangular particles, spanning dimensions from 19.05 mm down to silt-sized particles. Through the lens of the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS), granular (MASH strong) soil can be systematically classified under the well-graded gravel (GW) category.

A rheological soil model (FHWA soil model) that is available within the LS-DYNA simulation platform is adopted to simulate granular (MASH) strong soil. An in-depth discussion on the fundamental theoretical basis of the FHWA granular soil model for modeling dynamic pile-soil interaction under vehicle impacts is presented in [

36]. The details regarding the theoretical basis of the soil model are not discussed herein; however, a brief description of the FHWA granular soil model is discussed below.

The FHWA soil model is specifically developed to model dense and rapid granular flows of compacted road-base material, also known as NCHRP Report 350 strong soil [

37] , used in crash testing of soil-based roadside safety structures. It should be noted that the NCHRP Report 350 strong soil is most similar to granular (MASH strong) soil. This constitutive model has been identified as the most suitable and comprehensive (granular) soil model within LS-DYNA hydrocode for incorporating elasto-plastic soil behavior, including the effects of confinement, strain rate, damage or strain softening, moisture, and pore water pressure [

38,

39,

40,

41].

The FHWA soil model is developed within the elasto-viscoplastic constitutive framework. The elastic behavior is based on Hooke’s law (i.e., isotropic linear elasticity). The condition of plastic yielding is based on a modified Mohr-Coulomb yield function that relates the deviatoric stresses with the hydrostatic pressure exerted on the granular soil. The elastic condition allows the granular soil to stagnant configuration. In contrast, the plastic condition enables the granular soil to yield when the stress state reaches the shear strength of the granular soil. The FHWA soil model included a viscoplastic regularization of the continuum damage model via Duvaut-Lions type viscoplastic formulation to model the rapid, dense flow of compacted granular (MASH strong) soil during pile impacts.

The regularized softening or damage model enables the FHWA granular soil model to account for the large soil deformation as well as to capture the transition to fluid-like soil flow, including liquefaction-like behavior that is typically observed during crash testing of piles embedded in granular soil.

The calibrated granular (MASH strong) soil input parameters used in this study are shown in

Table 1. Details regarding the selection and determination of input parameter values for the granular (MASH strong) soil are discussed in [

36]. Additionally, in [

36], a detailed discussion is provided on the range of values of the FHWA soil model input parameters for computational modeling and simulation of dynamic impact pile-soil interaction problems that typically involve granular (MASH strong) soil.

3.2. Steel Pile

The most widely used steel material model under dynamic impact environments, the piecewise-linear plasticity model [

23,

24], was adopted to model the stresses and strains in the steel piles. In the piecewise-linear plasticity model, the deviator stress is determined to satisfy the yield function as follows:

in which,

sij is the deviator stress tensor and

where

β is a strain rate factor and accounts for strain-rate effects,

is the initial yield stress,

is the hardening function, and can be specified in tabular form or linear hardening of the form

with plastic hardening modulus

.

In this elstoplastic model, the deviator stresses are updated elastically, and the yield function is checked. The deviator stresses are accepted if the yield function is satisfied. Otherwise, the plastic strain increment is calculated as follows:

in which,

is the current hardening modulus, and

G is the shear modulus. The trial deviator stress state,

is scaled back as follows:

The piecewise-linear plasticity model accounts for strain rate effects using using the Cowper-Symonds model. The Cowper-Symonds model scales the yield stress using a factor

β, which is calculated as:

in which,

is the effective plastic strain rate, and

c and

p are Cowper-Symonds strain rate parameters.

It is not possible to obtain Cowper-Symonds strain rate parameters from tensile tests. However, values of 40.4 and 5 for c and p, respectively, were reported to agree reasonably with test data for mild steel according to Symonds [

42]. Thus, the Cowper-Symonds strain rate parameters of c = 40.4 and p = 5 were the input parameters for the steel pile in the Piecewise-Linear Plasticity model.

For the current study, material properties for the American Society for Testing Materials (ASTM) A36 steel pile were obtained from tensile tests conducted on samples taken from W152x12.6 piles at MwRSF-UNL and reported in the work of Schmidt et al. [

43]. The material input parameters for the ASTM A36 steel pile are shown in

Table 2. Material properties for ASTM A992 steel pile were obtained from tensile tests conducted on samples taken from W152x23.6 ASTM A992 steel pile at MwRSF-UNL and reported in the work of Schrum et al. [

44]. The material input parameters for the ASTM A992 steel pile are presented in

Table 3.

3.3. Erosion Criteria

In this work, the removal of Lagrangian soil elements – conceptualized as element erosion – is triggered when the damage and principal failure strain cross a threshold value. Within the FHWA soil model, DAMLEV signifies the damage level, ranging between 0 and 1.0, and determines element erosion in soil material [

23]. Concurrently, 'EPSMAX' demarcates the maximum principal failure strain causing the removal of a solid element. Therefore, both DAMLEV and EPSMAX thresholds must be exceeded to invoke the deletion of a soil element. DAMLEV and EPSMAX were equalized with the maximum damage parameter (

) to incorporate element erosion in the soil model. As depicted in Equation (6), the maximum damage within the soil element is associated with the peak (

) and residual (

) friction angles of the soil. These values for element erosion were utilized as adaptivity thresholds in simulating various post-soil systems subjected to lateral impact loading.

4. Model Development and Simulation Details

Numerical models were developed to assess the capability of the erosion method in simulating laterally impacted pile-soil systems under various scenarios. First, the impact response of a flexible pile installed in soil was evaluated, mirroring a physical impact test performed on a W152x12.6 steel pile of 1,830 mm length, embedded 1,016 mm into MASH strong soil. Next, the study encompassed a pile-soil system primarily governed by soil failure rather than pile yielding or plastic deformation. To this end, a numerical model was established to reproduce a physical impact test conducted on a W152x23.6 stiff steel pile of 1,830 mm length, embedded (1,016 mm) in MASH strong soil. To facilitate appropriate comparisons with physical impact test data, all simulations were conducted for a 100 ms impact event or a pile displacement threshold of 750 mm. All computational tasks were executed using MPP LS-DYNA hydrocode, version R10.1.0, on the University of Nebraska’s Crane supercomputer cluster, equipped with Intel Xeon E5-2670 2.6GHz processors and allocated 32 cores per simulation.

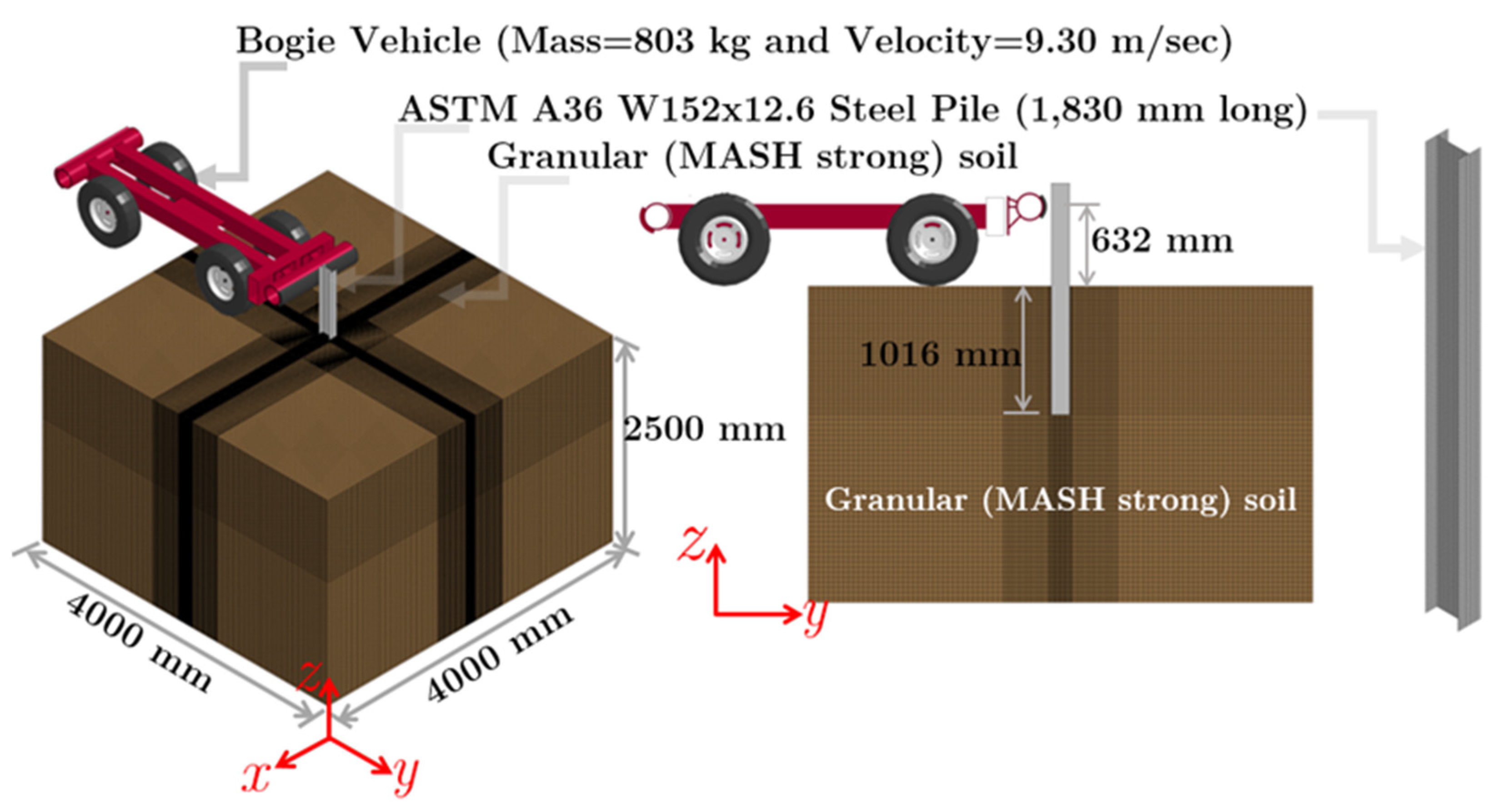

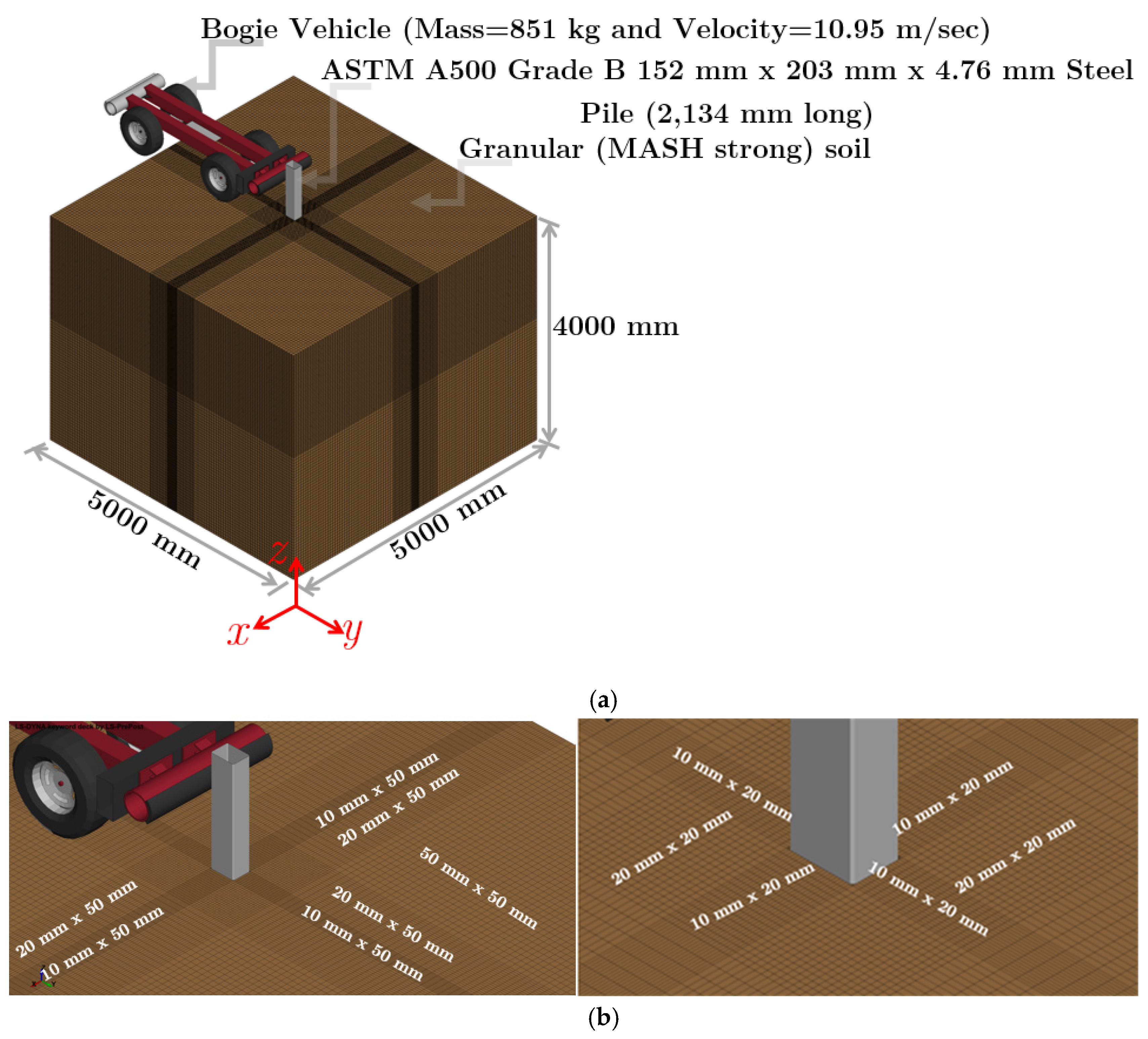

Computational model geometry, set-up, and initial conditions are shown in

Figure 2. The pile was composed of 3,660 four-noded, fully-integrated, square shell elements along the two flanges and 2,562 four-noded, fully-integrated, square shell elements along the web of the W152x12.6 pile. The shell elements along the web and flanges were 10 mm long across the pile height of 1,830 mm.

The soil domain was chosen as 4d x 4d in plan and 2.5d in depth to ensure that the soil domain boundaries are well outside the large deformation or plastic zone, where d represents the pile embedment depth. Thus, the soil domain size was 4,000 mm x 4,000 mm x 2,500 mm deep, consisting of 3,057,070 eight-noded, one-point quadrature hexahedral elements. Each soil element within the embedment depth had a depth of 20 mm, while each soil element outside the embedment depth had a depth of 40 mm. The soil mesh sizes varied in the X-Y plane based on distance from the W152x12.6 pile. Since large deformation and plastic flow of the soil occurs around the pile, a minimum soil mesh size was employed in the neighborhood (i.e., near-field soil domain) of the pile to accurately capture the large deformation of soil during pile impact. The size of the minimum mesh size was 5 mm x 10 mm. The near field-soil domain had a dimension of 914 mm x 914 mm. This dimension was determined based on observations made from high-speed videos captured from various pile-soil system physical impact tests at the MwRSF-UNL. In addition, during pile-soil impact testing at the MwRSF-UNL test site, piles are typically installed in a circular testing pit with an approximately 914 mm diameter.

In contrast, the maximum soil mesh size was in the corner of the soil domain (i.e., far-field soil domain), where the soil material has minimal plastic deformation. The maximum soil mesh size had a dimension of 40 mm x 40 mm in the X-Y plane. The adequacy of the soil domain size and mesh densities was confirmed by comparison against the size of soil blocks used in the works of Sassi [

5], Sassi and Ghrib [

6], Wu and Thompson [

8], and Whitworth et al. [

13].

The ability to extract acceleration data from the numerical model is essential to provide a direct comparison with the dynamic impact test data. Thus, model acceleration data was obtained from a node at the center of gravity of the bogie vehicle and processed similarly to the physical impact test data. Newton’s second law was used to obtain force. Using the speed of the bogie before impact and integrating acceleration twice, displacements were calculated with those forces and displacements being parallel to the impact direction. The energy dissipated by the pile-soil system was obtained by integrating areas under the force versus displacement curves.

The Automatic Node to Surface contact type in LS-DYNA was employed to model the contact between the bogie vehicle (neoprene impact head) and steel (pile) interaction. A static and dynamic friction coefficient of 0.1 was applied to model the friction interaction between the neoprene impact head and the pile. The values of the friction coefficients were adopted from Deladi [

45]. In dynamic impact simulations, it is often recommended to set static and dynamic friction coefficients equal to avoid potential numerical instabilities and a higher frequency contact [

23,

24].

A penalty-based, two-way, Eroding-Surface-to-Surface contact was implemented to model the interaction between the pile and soil. Eroding-Surface-to-Surface contact enables compression and tangential loads to be transferred from the master (pile) and slave segments (soil) and vice-versa. Contact surfaces are also updated as soil elements are eroded. The force that prevents penetration between segments depends on the stiffness of linear springs. The contact stiffness is independent of the material properties of the pile and soil and is calculated by dividing the nodal masses with the square of the time step [

23,

24]. The sliding contact between the pile (steel) and soil utilized a static coefficient of friction,

(where:

is the peak friction angle of soil), as suggested by Yoshimi and Kishida [

46] and Uesugi and Kishida [

47]. Static and dynamic coefficients of friction were set equal to avoid potential numerical stabilities and a higher frequency contact.

The Boundary Non-Reflecting (BNR) boundary condition on the computational domain was utilized for all baseline model simulations. Unlike standard boundary constraints where rotations and displacements are fixed, the BNR condition does not constrain rotations and displacements. Instead, conditions and equations are defined internally within the solver to characterize the computational domain as an infinite medium [

23,

24].

The load application to the computational models of the pile-soil systems consisted of two stages. In the first stage, the explicit dynamic relaxation feature was employed to apply gravity slowly to the pile-soil systems before the onset of transient loading so that after the completion of the dynamic relaxation or initialization phase, the pile-soil systems will be under an appropriate initial state of stress. Upon completion of the dynamic relaxation or initialization stage, the model was stabilized, and the transient impact load was applied on the computational model of the pile-soil system. In order to apply impact load, the bogie vehicle was assigned with an initial velocity that corresponded to the initial velocity of the bogie vehicle immediately before impacting the pile-soil systems in the physical impact tests.

5. Simulating Impact Response of Flexible Pile in Soil

5.1. Comparison Between Simulation and Physical Impact Tests

Computer simulation of a bogie impacting an 1,830-mm long, W152x12.6 steel pile embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil at a speed of 8.94 m/sec was completed to assess the accuracy of the erosion method for simulating the dynamic pile-soil interaction problems that are primarily governed by pile failure or plastic bending instead of soil failure. The pile was embedded 1,016 mm into the soil, and the volume was modeled using the erosion method. Results were compared against large-scale dynamic impact tests of a bogie vehicle impacting piles embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil. Quantitative comparisons focused on force vs. displacement response, energy vs. displacement response, and average impact forces with test nos. MH-1 and MH-4 from Schmidt et al. [

43] being selected for comparisons. The bogie vehicle impacted the pile at a speed of 9.30 m/sec for test no. MH-1 and at 8.90 m/sec for test no. MH-4.

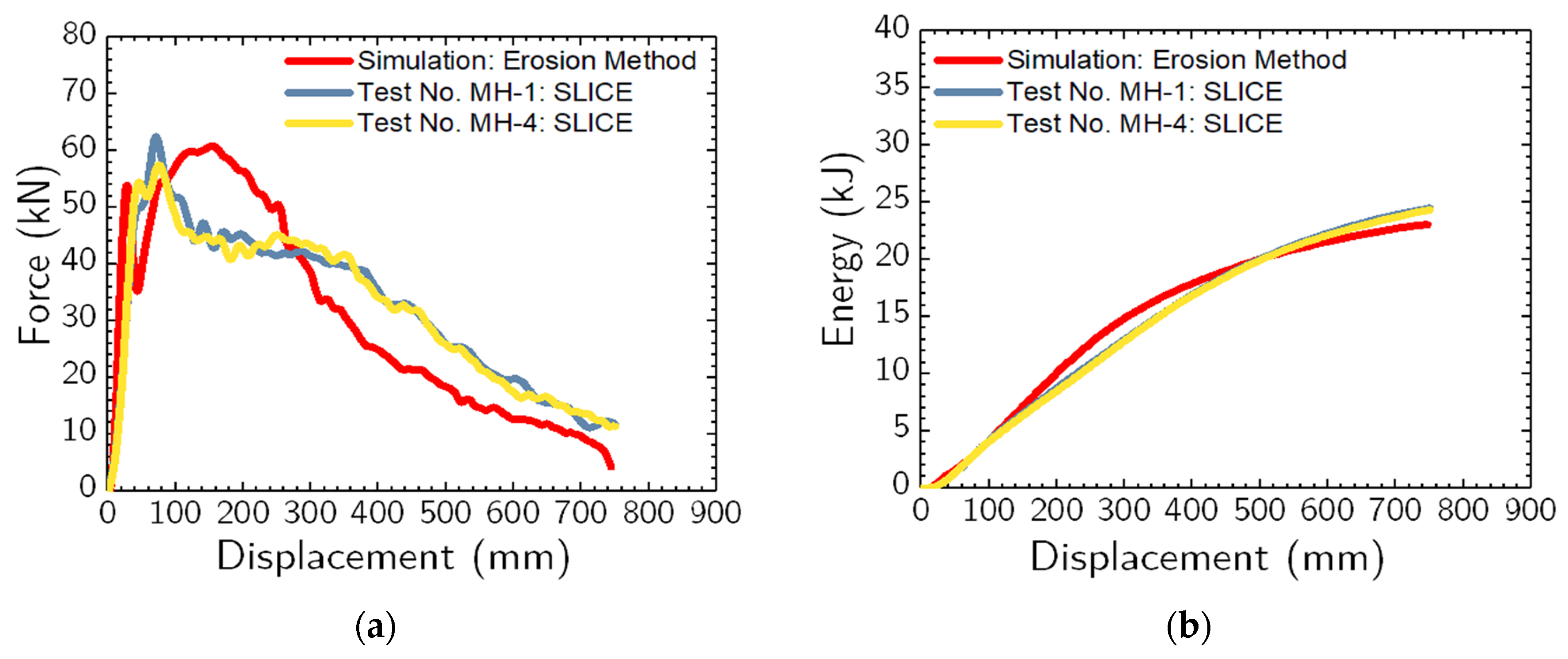

Comparisons of simulation results with dynamic impact testing results are shown in

Figure 3 and provided in

Table 4. The most important results for comparison purposes were an average force at 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm of pile displacement (measured at the impact height). The average force at a particular displacement is calculated by dividing the energy by a specific displacement. This idealized force at different displacements is vital for practical use in designing and analyzing, soil-based barrier systems under vehicle impacts [

48].

The average forces at pile displacements of 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm, from the numerical simulation were within 6.2%, 16.2%, 7.2%, and 0.2%, respectively, when compared to the average (average forces) of the impact tests, as presented in

Table 4. The total energy obtained from the simulation was within 6.9% compared to the average total energy of the dynamic impact tests. Results from simulated dynamic impact events within 20% of a test are typically considered reasonable [

49]. Thus, these results were deemed reasonable and satisfactory for the complex dynamic impact pile-soil interaction problem.

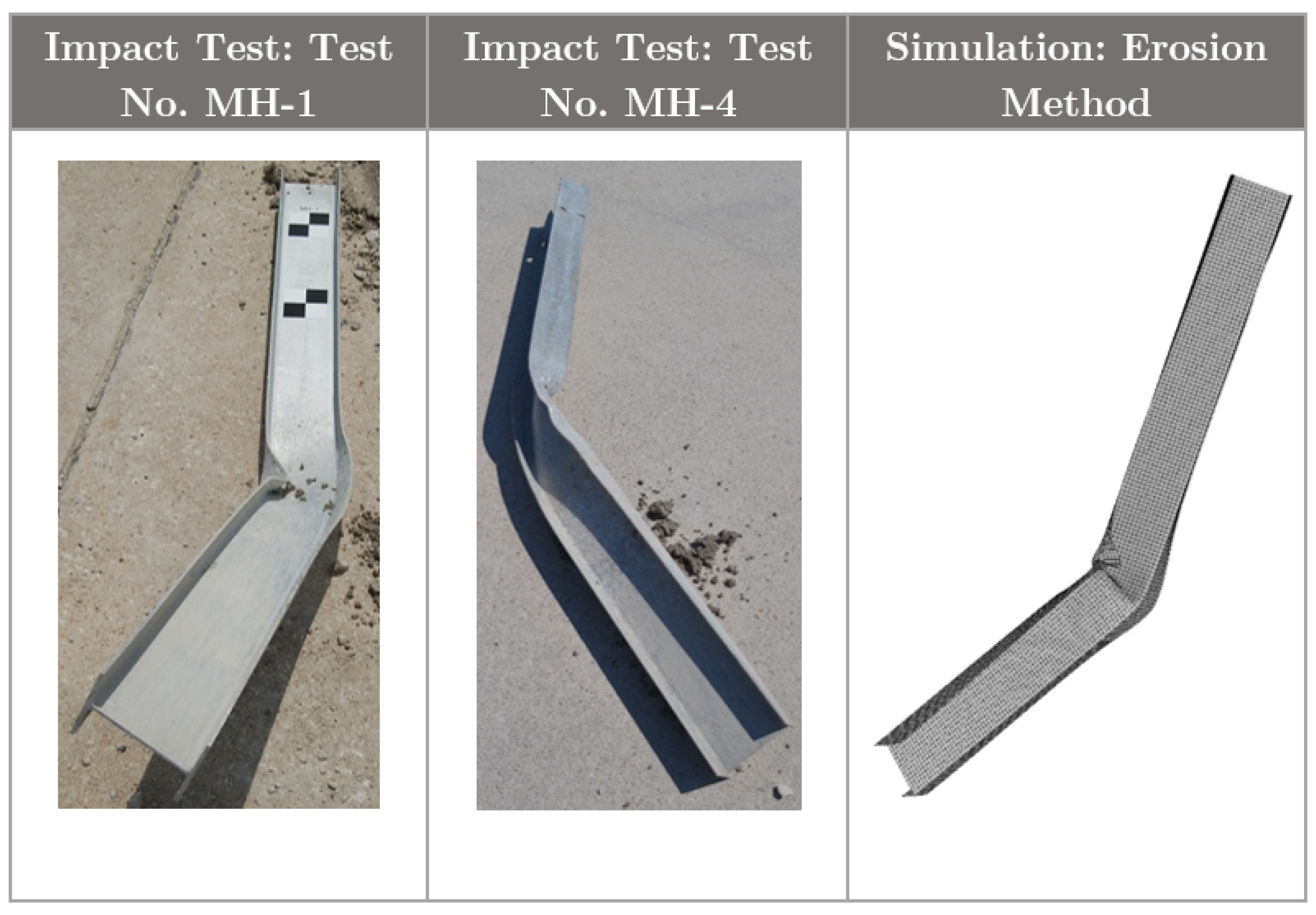

Post-impact photograph from the simulation were compared with test no. MH-1, as shown in

Figure 4. This comparison indicated that the computational model appears to predict global behavior well as ascertained via a study of deformed shapes and the locations of regions where local buckling and plastic material response were observed. When the final deformed shape of the pile was compared to model predictions, as shown in

Figure 4, largely similar permanent set and localized plastic deformations were observed. The complete yielding of the pile due to lateral-torsional buckling was observed at a distance of 265 mm below the ground surface in the computational model. In test nos. MH-1 and MH-4, the W152x12.6 steel pile bent backward and yielded approximately 254 mm below the ground surface [

43].

5.2. Discussion of Results

As shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, the maximum dynamic bending moment produced by the lateral impact has exceeded the yield moment of the pile section. As such, the lateral impact capacity of a W152x12.6 pile (with embedment depth of 1,016 mm) embedded in MASH strong soil is primarily governed by the pile characteristics. This type of failure mechanism is a “flexible” or “long” pile mechanism in traditional geotechnical engineering. As presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, a plastic hinge is formed. Hence, the impact resistance of the pile-soil system was dependent on the dynamic yield moment of the pile. This dynamic yield moment is reached before full mobilization of the dynamic soil resistance. Furthermore, the soil reached its full dynamic resistance above the steel pile’s yield point, as depicted in

Figure 6.

The contours of von Mises stress variations in the soil at different times presented in

Figure 6 show that plastic deformation of the soil primarily occurs in the near-field soil domain where the pile deformed plastically. The results from the stress analysis indicate that the impact resistance to yielding provided by the soil below the yield point is infinite, and the rotation of the pile cannot happen. The lower part of the embedded pile region remained mostly vertical, while the upper part deformed to a shape shown in

Figure 6.

6. Simulating Impact Response of Rigid Pile in Soil

6.1. Comparison Between Simulation and Physical Impact Tests

Numerical simulation of a bogie impacting an 1,830-mm long, W152x23.6 steel pile embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil at a speed of 9.84 m/sec was completed to assess the accuracy of the proposed soil modeling method (tool) to simulate pile-soil systems primarily governed by soil failure, rather than pile yielding or plastic deformation. The pile was embedded 1,016 mm into the soil, and the soil volume was modeled using the erosion method. Simulation results were compared to large-scale dynamic impact tests of a bogie vehicle impacting a W152x23.6 steel pile embedded in MASH strong soil. Quantitative comparisons focused on force vs. displacement response, energy vs. displacement response, and average impact forces with test nos. BL-8 and BL-20 being selected for comparisons. The bogie vehicle impacted the pile at a speed of 9.84 m/sec for test no. BL-8 and at 9.21 m/sec for test no. BL-20. The mass of the bogie vehicle, including accelerometers and the mountable head, was 783 kg and 842 kg, in test no. BL-8 and test no. BL-20, respectively.

Comparisons of simulation results with dynamic impact testing results are provided in

Table 5 and shown in

Figure 7. Again, the most important results for comparison purposes were the average force at 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm of pile displacement (measured at the impact point); and total energy absorbed by the pile-soil system. The average forces at pile displacements of 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm from the numerical simulation were within 18.1%, 11.8%, 0.3%, and 5.0%, respectively, when compared to the (average) average forces of the physical impact tests. The total energy obtained from the simulation was within 20% compared to the average total energy of the dynamic impact tests. As noted previously, results from simulated dynamic impact events within 20% of a test are typically considered reasonable [

49]. Thus, these results were deemed reasonable and satisfactory for the complex dynamic impact pile-soil interaction problem.

6.2. Discussion of Results

In contrast to the “long” or “flexible” pile, i.e., W152x12.6 with an embedment of 1,016 mm, the behavior of the W152x23.6 pile with an embedment of 1,016 mm is primarily governed by the lateral soil failure instead of the yielding of the pile, as presented in the time-sequential photographs of the physical impact tests and simulated in

Figure 8. The lateral impact load caused the failure of the granular (MASH strong) soil along the entire pile length, as depicted in the effective (von-Mises) stress contours in

Figure 9. Therefore, a 152x23.6 pile with an embedment of 1,016 mm behaves essentially as a “short” or “rigid” pile, and the dynamic soil resistance governs its impact behavior, load capacity, and energy dissipation.

7. Effect of Soil Mesh Density on Response of Laterally Impacted Pile-Soil Systems

This study examined the effect of soil mesh density around the pile during lateral vehicular impacts. The objective of this investigation was to provide better insight into the influence of soil mesh density on the dynamic response of the pile-soil system. Further, it was desired to provide guidelines and recommendations on soil mesh densities (sizes) for pile-soil impact simulations using the erosion method.

7.1. Model Geometry and Discretization

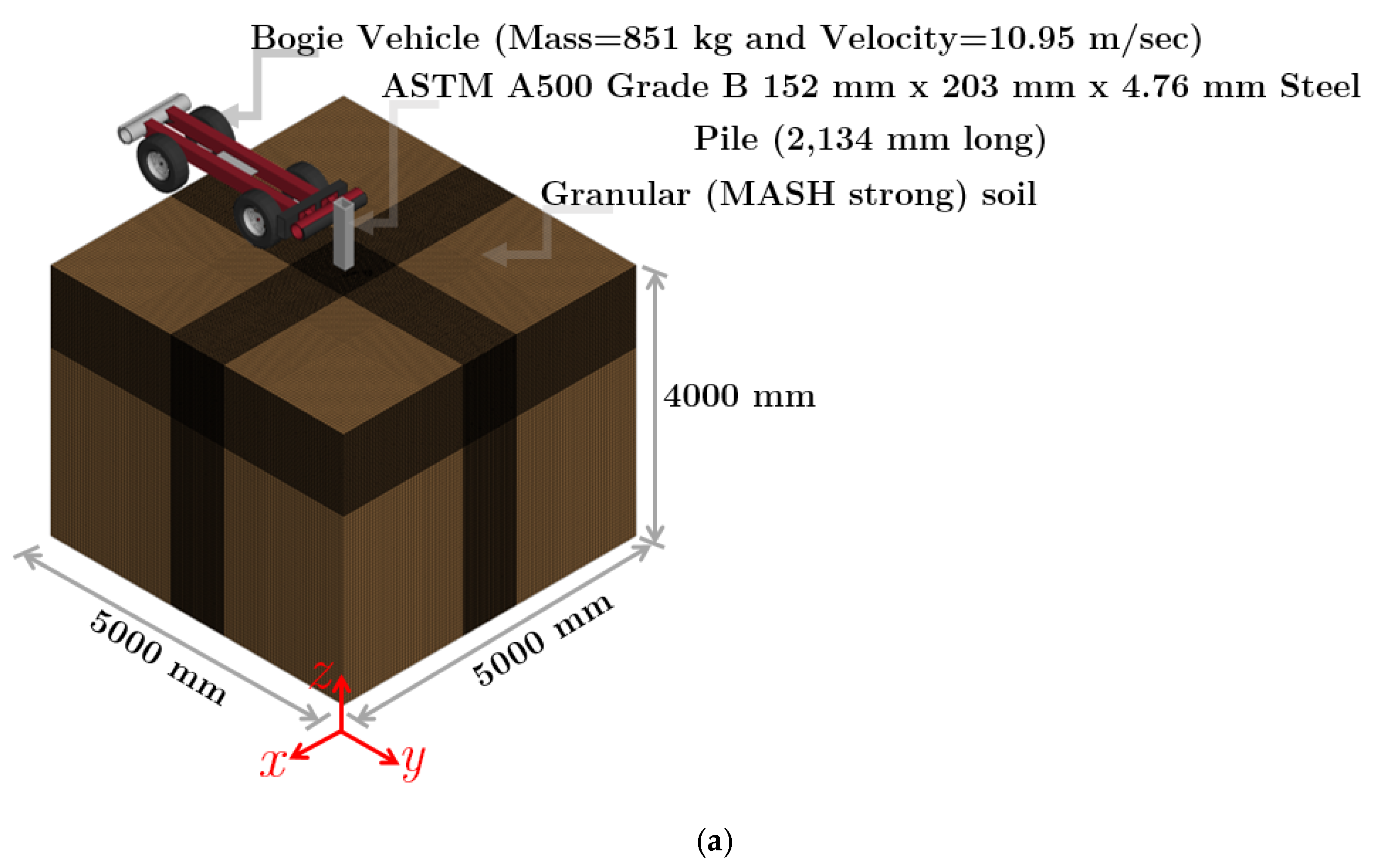

In order to fulfill the above objective, two mesh densities were considered: (1) baseline mesh size model (

Figure 10), which varied in the global X and Y direction based on distance from the pile, and (2) uniform mesh size model (

Figure 11), which had a uniform soil mesh configuration around the pile. For the noted investigation, a 2,134-mm long, ASTM A500 Grade B steel tube pile (i.e., a 152 mm x 203 mm with a wall thickness of 4.76 mm embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil was considered. The focus was on the large-deformation soil zone (near-field soil domain) around the pile, which was 914 mm x 914 mm in the global X-Y plane. As noted previously, this large-deformation soil zone was determined based on observations from various physical impact tests conducted on pile-soil systems.

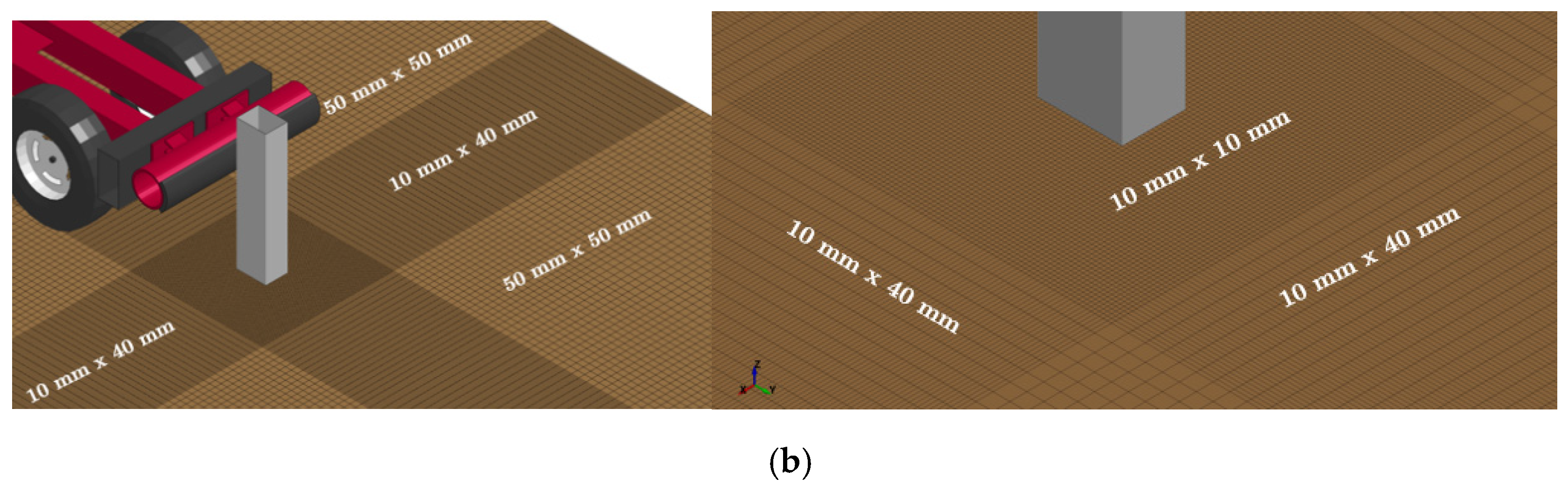

7.1. Results

Results from simulation were compared with large-scale dynamic impact tests where a bogie vehicle impacted a steel tube pile set within granular (MASH strong) soil. The focal metric for comparison was the average impact force versus pile displacement, with data from test no. P3G-7, as documented by Meyer et al. [

50], was chosen as the benchmark. The average force holds significance in the design and analysis of soil-embedded barriers and containment systems facing vehicular impacts [

48]. A comparison, encapsulating average forces and percentage differences between the simulated and physical test results, is shown in

Figure 12. This comparison is specifically rendered for average forces spanning pile displacements from 125 mm to 500 mm, as illustrated in

Figure 12(b).

The simulation-derived average forces resonated well with those recorded during dynamic impact tests. For pile displacements at 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm, the baseline mesh-size simulation deviated by 9.2%, 2.1%, 4.6%, and 6.2%, respectively, from the physical test data. Conversely, the uniform mesh simulation showcased deviations of 1.2%, 10.2%, 4.8%, and 1.2% for the same displacements. Both simulation approaches—baseline and uniform meshes—yielded results within a 5% to 10% range of the physical impact test.

7.2. Guidelines and Recommendations

The findings presented in the previous section suggest that pile-soil impact models constructed with soil mesh sizes of 1 to 1 and 1 to 2 or (2 to 1) element aspect ratios within the large deformation soil region as well as element aspect ratio not more than a 5 to 1 or (1 to 5) for the entire soil volume (domain) could replicate the essential responses of the dynamic impact pile-soil interaction problem. Pile-soil impact simulation models constructed with soil mesh sizes between 10 mm x 20 mm x 20 mm and 50 mm x 50 mm x 20 mm, as well as with soil mesh sizes between 10 mm x 10 mm x 10 mm and 50 mm x 50 mm x 10 mm shows favorable agreement with physical impact test data in terms of pile-soil systems resistive forces and energy absorption. Thus, it is recommended that a constraint of no more than a 5 to 1 (or 1 to 5) soil element aspect ratio with mesh sizes between 10 mm x 10 mm x 10 mm and 50 mm x 50 mm x 10 mm could be used for pile-soil impact simulations within the framework of the erosion method.

It is well known that significant mesh size differences between adjacent solid elements cause artificially induced excessive numerical errors in finite element analysis. Therefore, it is advisable to avoid abrupt soil element size differences among adjacent elements to avoid potential numerical errors in the pile-soil impact numerical simulation. As presented in this study, the soil models used a restriction of no more than a 5 to 1 or (1 to 5) for the small deformation region and no more than 1 to 1 or 1 to 2 or (2 to 1) element aspect ratios for the large deformation zone satisfactorily predicted the impact behavior of pile-soil system. Hence, a soil-element aspect ratio smaller than or equal to 5 to 1 or (1 to 5) was desirable for the pile-soil impact simulation.

8. Effect of Soil Domain Size on Response of Laterally Impacted Pile-Soil Systems

For conducting any soil continuum-based computational analysis on dynamic pile-soil interaction problem, determining the size of the soil domain (volume) is essential. Theoretically, considering as large as possible soil volume would be ideal as it produces dynamic responses free from boundary effects. Nonetheless, such a choice leads to enormous computational costs, and it is not feasible or practical for modeling full-scale, soil-based, barrier and containment systems. Thus, it is important to justifiably define the size of soil volume for dynamic pile-soil interaction analysis that would ensure computational efficiency without the loss of accuracy of the dynamic response of the pile-soil system. In order to make the computational models more general and applicable for modeling various full-scale, soil-embedded barrier systems under vehicular impacts, the size of the soil domain was linked to the pile embedment depth (d).

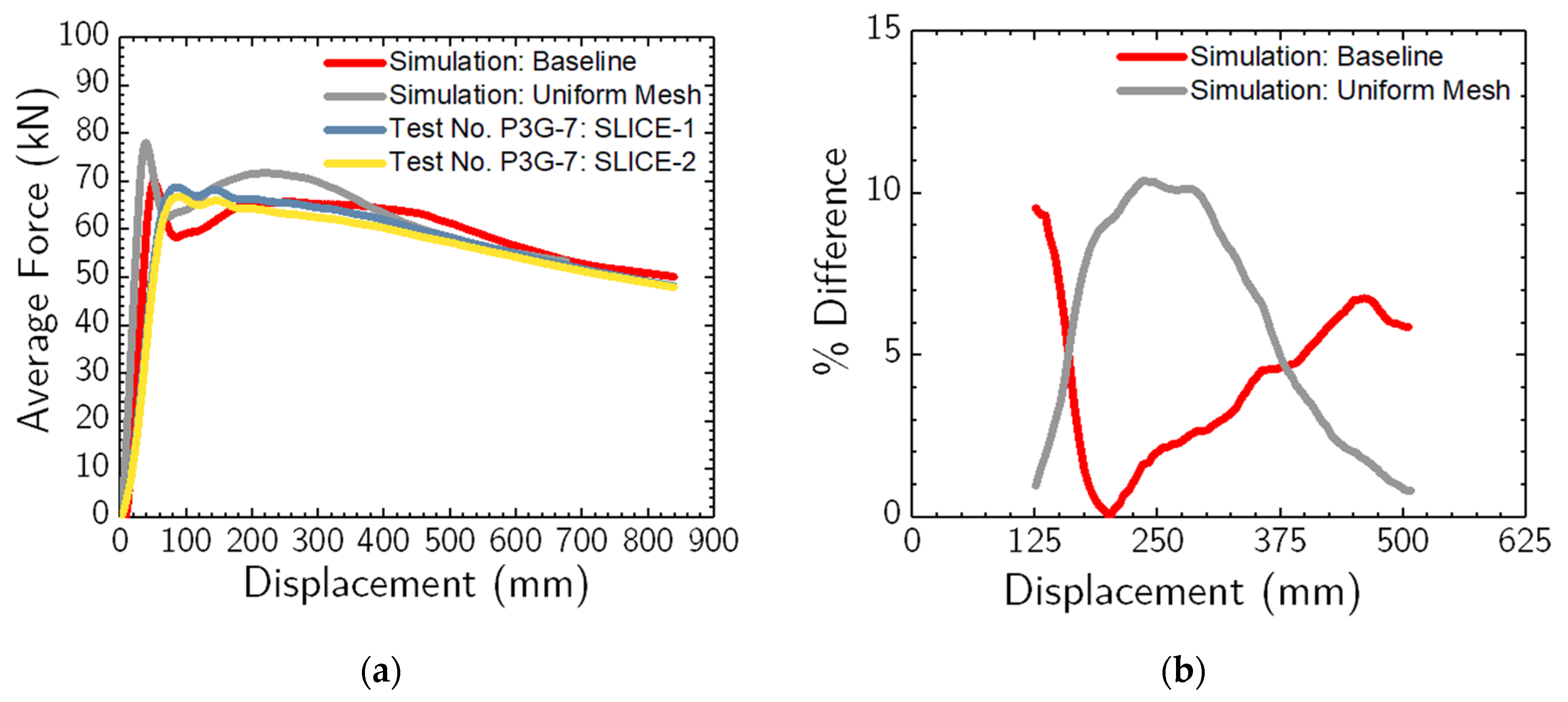

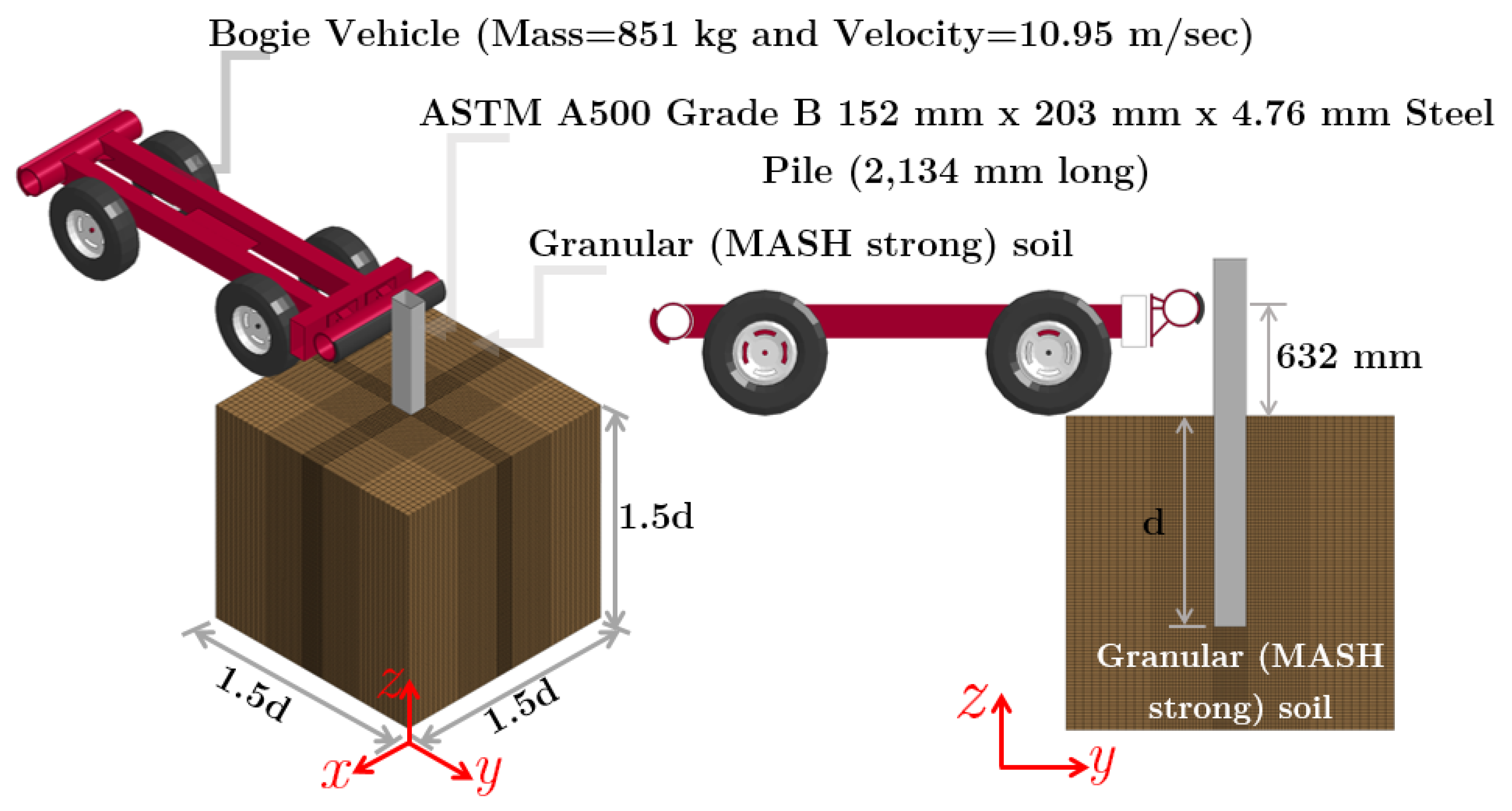

8.1. Model Geometry and Discretization

Numerical simulations of a bogie vehicle impacting a 2,134-mm long, ASTM A500 Grade B steel tube pile (i.e., a 152 mm x 203 mm with a 4.76 mm wall thickness and embedment depth (d) of 1,219 mm) embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil at a speed of 10.95 m/sec was completed to assess the effects of soil domain size on the results of dynamic impact pile-soil interaction. The soil volume was modeled using the erosion method following the previously discussed modeling methodologies and procedures. Six different soil volume sizes were considered, which were subjected to the previously mentioned impact conditions, and their response was monitored and analyzed. The soil volumes that were considered for this research effort were: (1) 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d; (2) 2d x 2d x 1.5d; (3) 2d x 2d x 2d; (4) 3d x 3d x 2d; (5) 3d x 3d x 3d; and (6) 4d x 4d x 3d. An example of the details of the impact conditions, pile geometry, material properties, and the volume of soil domain utilized is provided in

Figure 13.

8.2. Results

The sensitivity of modeling results, including the force vs. displacement and energy vs. displacement responses of the pile-soil system to the various sizes of the soil domain, was examined to understand the influence of the soil domain size. The simulation results were compared with full-scale, physical impact testing data to quantify the change in pile-soil system response due to the size of soil volume.

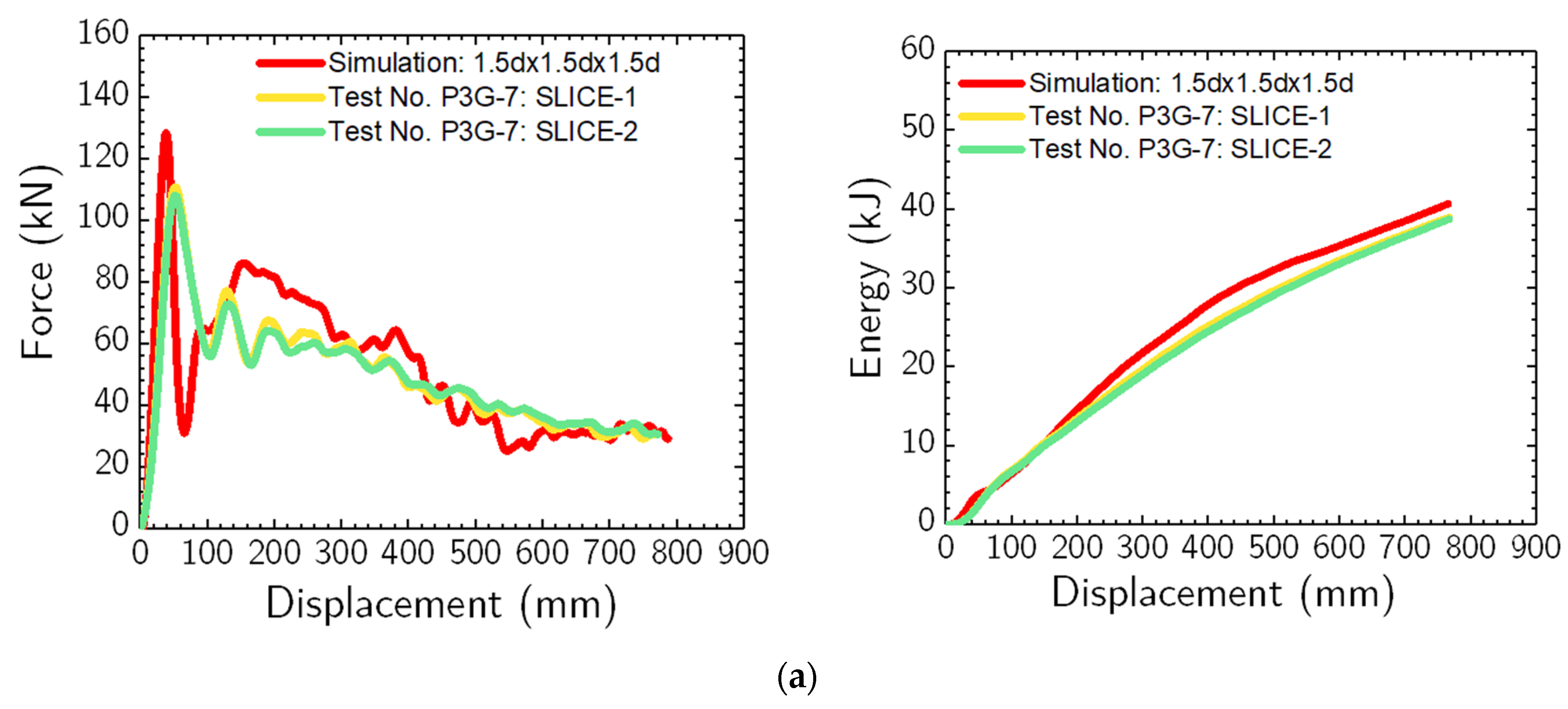

Figure 14 (a) shows a force vs. displacement and energy vs. displacement comparison between the impact test data from Meyer et al. [

50] and simulation with 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d soil domain. The simulation showed a stiffer response for the initial 250 mm of pile displacements (at the impact height) compared to the physical impact test data. Additionally, there was an increase in the energy dissipation prediction for large pile displacements. The average force deviations between the simulation and the physical impact tests at pile displacements of 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm were observed at 1.5%, 11.8%, 10.6%, and 9.2%, respectively. For the 2d x 2d x 1.5d soil domain, as shown in

Figure 14 (b), the simulation overpredicted the resistive forces for pile displacements between 125 mm and 450 mm. The average force deviations at these displacements were 3.2%, 10.5%, 10.2%, and 9.4%, respectively.

Considering the 2d x 2d x 2d soil domain, the simulations (

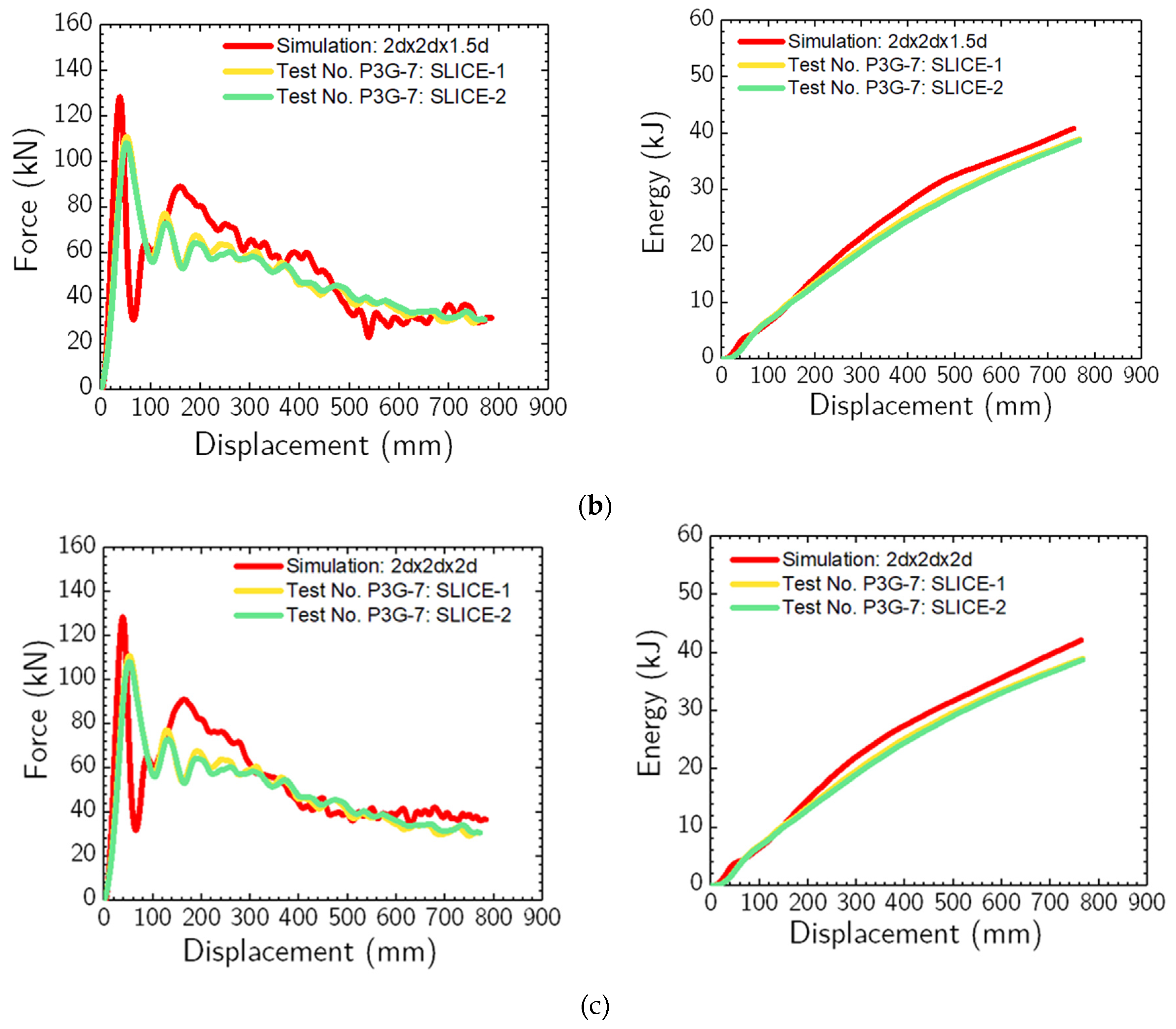

Figure 14 (c)) revealed a stiffer response for displacements between 125 mm and 300 mm, accompanied by increased energy dissipation predictions for displacements beyond 250 mm. The force deviations at 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm were 2.2%, 12.6%, 11.2%, and 7.3%, respectively. Within the 3d x 3d x 2d soil domain,

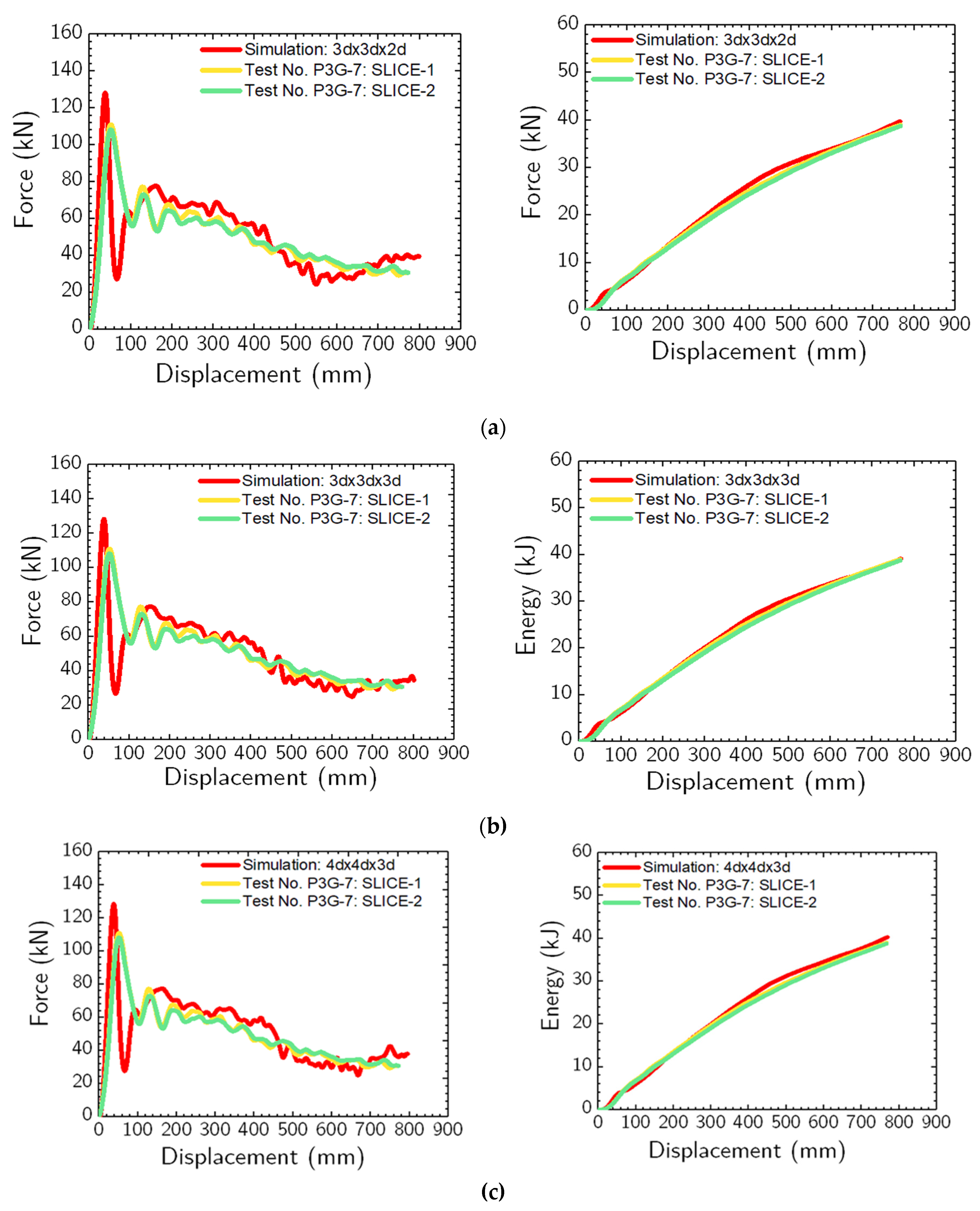

Figure 15 (a) compares the simulation and physical impact test. A slightly stiffer response is discernible between 125 mm and 400 mm displacements. The recorded average force deviations at 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm pile displacement were 5.1%, 4.1%, 6.2%, and 4.7%, respectively.

In the context of the 3d x 3d x 3d soil domain,

Figure 15 (b) displays a notable alignment between the simulation and physical tests, particularly in force vs. displacement and energy vs. displacement. Discrepancies in forces at displacements of 125 mm (5 in.), 250 mm (10 in.), 375 mm (15 in.), and 500 mm (20 in.) were 6.8%, 3.1%, 4.2%, and 3.2%, respectively. Lastly, for the 4d x 4d x 3d soil domain, as illustrated in

Figure 15 (c), the simulation mirrored the experimental data effectively. Discrepancies in average forces at displacements of 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm were observed at 9.6%, 2.3%, 4.6%, and 3.2%, respectively.

In evaluating the dynamic response of the pile-soil system, differences were evident between the smallest and the largest soil domain sizes. With an increasing soil domain size, the dynamic response of the pile-soil system gradually converged towards the characteristics of larger soil domain sizes. Notably, the sensitivities in the system's response were amplified for the smaller soil domain sizes, particularly for 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d, 2d x 2d x 1.5d, and 2d x 2d x 2d configurations. In contrast, the responses manifested remarkable consistency across larger domain sizes, specifically in 3d x 3d x 2d, 3d x 3d x 3d, and 4d x 4d x 3d. A significant change in both force vs. displacement and energy vs. displacement responses was observed upon the domain size increase from 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d to 3d x 3d x 2d.

Contrastingly, the difference was markedly subdued when the soil domain size increased from 3d x 3d x 2d to 3d x 3d x 3d. This observation highlights that past a specific soil domain size, the dynamic response of the pile-soil interaction experiences only negligible changes. Consequently, for engineering applications, there appears to be a defining soil domain size that accurately captures the pile-soil system's dynamic behavior. This domain size can be categorically referred to as the “optimum soil domain size.” Delineating this optimum dimension can substantially reduce computational costs without sacrificing response accuracy. To ascertain this optimal size, it is imperative to undertake a computational time investigation across the discussed soil domain sizes. Pursuant to this, we executed a computational time analysis, laying down guidelines and recommendations for the optimal soil domain size pertinent to pile-soil system modeling. Subsequent sections discuss this computational time study.

9. Effect of Boundary Condition on Response of Laterally Impacted Pile-Soil Systems

In the context of pile-soil impact numerical analyses, the role of boundary conditions is paramount. For the baseline model, boundary non-reflecting (BNR) boundary conditions were applied to the exterior surfaces, encompassing four sides and bottom boundaries. Such a boundary condition mirrors real-world environments by negating the re-entry of artificially generated stress waves at soil model boundaries.

A contrasting approach adopted in numerous studies for soil-foundation systems simulation is the single point constraint (SPC) boundary condition (i.e., pin, or fixed boundary conditions). Herein, displacements and rotations are constrained [

51,

52,

53]. The comparative accuracy of BNR and SPC conditions in dynamic pile-soil interaction remains under-investigated in existing literature. Past studies also offer limited guidance on optimal soil domain size and the most appropriate boundary conditions for dynamic impact pile-soil analyses. The present investigation probed the effects of BNR and SPC boundary conditions on the dynamic response of pile-soil systems across varied soil domain sizes. The subsequent section elucidates the derived insights.

9.1. Results

The dynamic response of pile-soil systems under varied boundary conditions was critically assessed across multiple soil domain sizes, determined by the pile's embedment depth (d). Both BNR and SPC boundary conditions were considered. The soil domains evaluated included: 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d, 2d x 2d x 1.5d, 2d x 2d x 2d, 3d x 3d x 2d, 3d x 3d x 3d, and 4d x 4d x 3d.

The simulations' average resistive force responses were compared against physical impact test data.

Table 6 and

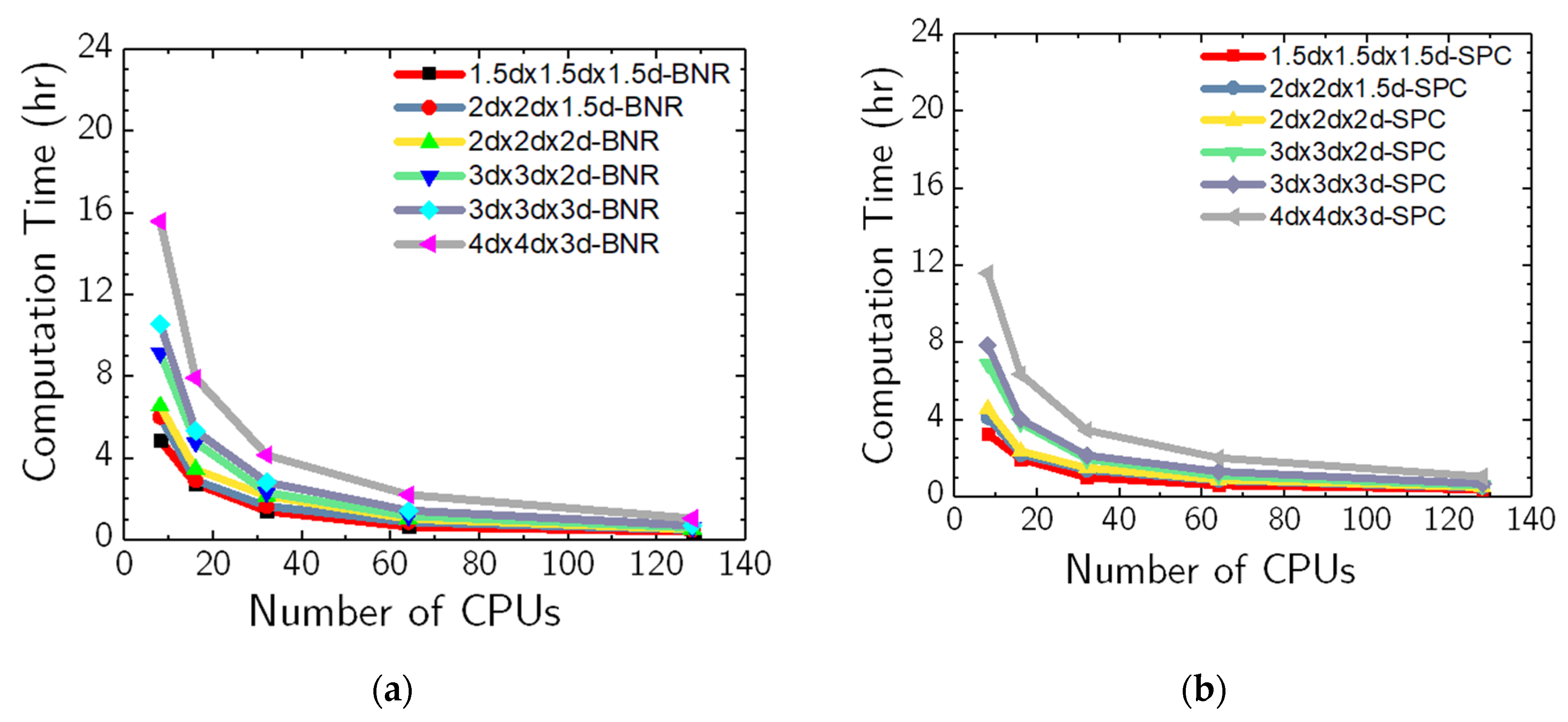

Table 7 present the difference in average force between the simulations (BNR and SPC conditions) and the physical impact tests from dataset P3G-7, measured at pile displacements of 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm. Rather than gauging the computational efficiency of these models solely at a single CPU count, performances were assessed at 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128 CPU counts, as illustrated in

Figure 16 and

Figure 17. Additionally, the analysis duration, considering the number of solid soil elements and boundary conditions, was evaluated, detailed in

Figure 17. Based on these insights, subsequent sections provide consolidated guidelines and recommendations for pile-soil impact modeling and simulations using the erosion method.

9.2. Guidelines and Recommendations

Within pile-soil system dynamics, the fidelity of numerical simulations depends on the extent of the soil domain size and boundary conditions adopted. An investigation into the system's response for varied soil domain sizes revealed distinctive trends, highlighting the importance of these parameters for accurate modeling. For larger soil domain sizes, such as 3d x 3d x 2d, 3d x 3d x 2d, and 4d x 4d x 3d, the response was less affected by boundary conditions. For instance, the 4d x 4d x 3d domain exhibited a negligible influence from boundary conditions applied at both bottom and exterior boundaries. Therefore, responses at these sizes serve as an effective benchmark. On the contrary, the smaller soil domain sizes (1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d to 2d x 2d x 2d) were significantly influenced by boundary conditions, especially the SPC type.

A discernable difference was observed in the system's dynamic response between the smallest and largest domain sizes, regardless of the boundary conditions. As domain size increased, the system's response became increasingly similar to larger domains for both BNR and SPC conditions. For instance, the shift from 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d to 3d x 3d x 2d elicited a pronounced change in force versus displacement and energy versus displacement response. However, this variation was subdued when progressing from 3d x 3d x 2d to 4d x 4d x 3d, implying that the dynamic response exhibits marginal alterations after a threshold. This observation emphasizes an "optimum soil domain size" – the ideal size that captures the system's dynamic response without undue computational cost.

In light of computational efficiency, two regions of computation time trends exist, as discerned from

Figure 16 and

Figure 17. The initial region (8-32 CPUs) showcases a sharp rise in computation time with expanding soil domain size. Subsequently, an asymptotic trend emerges (32-128 CPUs) irrespective of boundary conditions. Importantly, BNR boundary conditions typically demanded 20% to 50% more computation time than the SPC.

Comparative analysis with physical impact test data affirms that simulations with BNR boundary conditions across all evaluated soil domain sizes accurately model the dynamic response. Meanwhile, domains of 3d x 3d x 2d to 4d x 4d x 3d with SPC boundary conditions offer a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. Thus, these configurations are recommended for future numerical modeling endeavors of the pile-soil impact problem using the erosion method.

10. Summary and Conclusions

A computationally efficient, large-deformation soil modeling method, i.e., the UL-FEM enhanced by erosion algorithm, referred to as the erosion method for the numerical simulation of pile-soil impact problem, has been presented. The UL-FEM enhanced by erosion algorithm has been combined for the first time with a continuum damage-based viscoplastic soil constitutive model, which realistically predicts the dynamic mechanical behavior of granular (MASH strong) soil. Comparisons between simulation and field-scale physical test results were discussed. The key findings from the study presented in this paper are highlighted below.

The proposed large deformation soil modeling method for pile-soil impact analysis based on element erosion algorithm within the UL-FEM framework agreed well the measured pile-soil impact response. The applicability of the soil modeling method has been successfully demonstrated for both “long” or “flexible” and “short” or “rigid” pile behavior under impact loading.

The simulation method presented in this study overcomes the inherent limitations of popular soil modeling techniques typically used for modeling piles embedded in soil under vehicular impacts, such as the lumped parameter method, subgrade reaction approach, modified subgrade reaction method, and direct method.

This study investigated the effect that soil domain sizes and boundary conditions had on the dynamic impact response of pile-soil systems using field-scale physical impact test data. This study should help engineers and researchers to better understand the influence of soil domain sizes and boundary conditions on the dynamic response of piles embedded in granular soil when subjected to lateral vehicular impacts. Furthermore, guidelines and recommendations were provided on optimum soil domain size and boundary conditions.

Computational time studies were conducted to assess the efficiency of the various soil domain sizes and boundary conditions. This investigation demonstrated the effect that soil domain sizes and boundary conditions had on the performance of LS-DYNA pile-soil impact simulations.

The modeling method developed in this study can be used to enhance and advance the current pile-soil system modeling methods and be extended for future research, such as modeling full-scale, soil-embedded barrier and containment systems.

This research work will significantly contribute to the numerical modeling techniques currently used by engineers and researchers in the analysis and design of piles subjected to vehicular impact loading. The findings of this study will facilitate the efficient and economically feasible pile design by reducing the required number of component crash tests of pile-soil systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yosef. and Faller.; methodology, Yosef, Faller; software, Yosef, Fang, Faller, Kim.; validation, Yosef, Fang, Faller, Kim.; formal analysis, Yosef, Fang, Faller, Kim; investigation, Yosef, Faller, Kim.; resources, Faller; data curation, Yosef, Faller, Kim.; writing—original draft preparation, Yosef.; writing—review and editing, Faller, Fang, Kim.; visualization, Yosef, Faller, Kim.; supervision, Faller, Kim.; project administration, Faller.; funding acquisition, Faller. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge several sources that contributed to this research: (1) the United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) − Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Nebraska Department of Transportation (NDOT), and the Midwest Pooled Fund Program for sponsoring this project; (2) MwRSF personnel for conducting the dynamic bogie testing; and (3) The Holland Computing Center (HCC) at the University of Nebraska -Lincoln.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pajouh, M.A., Schmidt, J., Bielenberg, R.W., Reid, J.D., and Faller, R.K., Simplified Soil-Pile Interaction Modeling under Impact Loading, in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics V. 2018, American Society of Civil Engineers Reston, VA. p. 269-280.

- Schmidt, J., Reid, J., Stolle, C., Faller, R., Bielenberg, R., Asselin, N., and Rilett, L., Analysis supporting development of a new, non-proprietary ASTM F2656-15 M30 barrier, in Final Report to the Surface Deployment and Distribution Command Transportation Engineering Agency. 2017, Midwest Roadside Safety Facility, University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Plaxico, C.A., Patzner, G.S., and Ray, M.H., Finite-element modeling of guardrail timber posts and the post-soil interaction. Transportation Research Record, 1998. 1647(1): p. 139-146. [CrossRef]

- Patzner, G.S., Plaxico, C.A., and Ray, M.H., Effects of post and soil strength on performance of modified eccentric loader breakaway cable terminal. Transportation Research Record, 1999. 1690(1): p. 78-83. [CrossRef]

- Sassi, A., Analysis of W-beam guardrail systems subjected to lateral impact, in Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. 2011, University of Windsor (Canada).

- Sassi, A. and Ghrib, F., Development of finite element model for the analysis of a guardrail post subjected to dynamic lateral loading. International Journal of Crashworthiness, 2014. 19(5): p. 457-468. [CrossRef]

- Tabiei, A. and Wu, J., Roadmap for crashworthiness finite element simulation of roadside safety structures. Finite Elements in Analysis and Design, 2000. 34(2): p. 145-157. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. and Thomson, R., A study of the interaction between a guardrail post and soil during quasi-static and dynamic loading. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 2007. 34(5): p. 883-898. [CrossRef]

- Opiela, K., Kan, S., and Marzougui, D., Development of a finite element model for W-beam guardrails. 2007.

- Bligh, R.P., Abu-Odeh, A.Y., Hamilton, M.E., and Seckinger, N.R., Evaluation of roadside safety devices using finite element analysis, in Sponsored by the Texas Department of Transportation In Cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration. 2004, Texas transportation institute, Texas A&M University: College Station, Texas.

- Marzougui, D., Mahadevaiah, U., and Opiela, K.S., Development of a modified MGS design for test level 2 impact conditions using crash simulation, in Working Paper, NCAC 2010-W-005. 2010, National Crash Analysis Center: Ashburn, VA.

- Hendricks, B.F. and Wekezer, J.W., Finite-element modeling of G2 guardrail. Transportation Research Record, 1996. 1528(1): p. 130-137. [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, H., Bendidi, R., Marzougui, D., and Reiss, R., Finite element modeling of the crash performance of roadside barriers. International Journal of Crashworthiness, 2004. 9(1): p. 35-43. [CrossRef]

- Kulak, R.F. and Bojanowski, C. Modeling of cone penetration test using SPH and MM-ALE approaches. in 8th European LS-DYNA users conference. 2011.

- Kulak, R.F. and Schwer, L. Effect of soil material models on SPH simulations for soil-structure interaction. in Proceedings of 12th International LS-DYNA Users Conference. 2012.

- Ceccato, F., Beuth, L., and Simonini, P., Adhesive contact algorithm for MPM and its application to the simulation of cone penetration in clay. Procedia Engineering, 2017. 175: p. 182-188. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, D., Gravish, N., and Tolley, M.T., Soft robot actuation strategies for locomotion in granular substrates. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 2019. 4(3): p. 2630-2636. [CrossRef]

- Butlanska, J., Arroyo, M., Gens, A., and O’Sullivan, C., Multi-scale analysis of cone penetration test (CPT) in a virtual calibration chamber. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 2014. 51(1): p. 51-66. [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.M. and Zhang, N., Three-dimensional simulations of plate anchor pullout in granular materials. International Journal of Geomechanics, 2019. 19(4): p. 04019004. [CrossRef]

- Gens, A., Arroyo, M., Butlanska, J., and O’Sullivan, C., Discrete simulation of cone penetration in granular materials. Advances in Computational Plasticity: A Book in Honour of D. Roger J. Owen, 2018: p. 95-111. [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A., Martinez, A., and DeJong, J., Discrete element model (DEM) simulations of cone penetration test (CPT) measurements and soil classification. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 2020. 57(9): p. 1369-1387. [CrossRef]

- Liang, W., Zhao, J., Wu, H., and Soga, K., Multiscale modeling of anchor pullout in sand. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 2021. 147(9): p. 04021091. [CrossRef]

- Hallquist, J.O., LS-DYNA theory manual. 2014, Livermore software Technology corporation: Livermore, CA, 10–82–10–102.

- Hallquist, J.O., LS-DYNA keyword user’s manual (r:13107). 2020, Livermore, CA, 10–82–10–102: Livermore software Technology corporation.

- Beppu, M., Miwa, K., Itoh, M., Katayama, M., and Ohno, T., Damage evaluation of concrete plates by high-velocity impact. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 2008. 35(12): p. 1419-1426. [CrossRef]

- Nyström, U. and Gylltoft, K., Numerical studies of the combined effects of blast and fragment loading. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 2009. 36(8): p. 995-1005. [CrossRef]

- Riedel, W., Kawai, N., and Kondo, K.-i., Numerical assessment for impact strength measurements in concrete materials. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 2009. 36(2): p. 283-293. [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z. and Lu, Y., Modifications of RHT material model for improved numerical simulation of dynamic response of concrete. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 2010. 37(10): p. 1072-1082. [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z. and Lu, Y., Evaluation of typical concrete material models used in hydrocodes for high dynamic response simulations. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 2009. 36(1): p. 132-146. [CrossRef]

- Farnam, Y., Mohammadi, S., and Shekarchi, M., Experimental and numerical investigations of low velocity impact behavior of high-performance fiber-reinforced cement based composite. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 2010. 37(2): p. 220-229. [CrossRef]

- Teng, T.-L., Chu, Y.-A., Chang, F.-A., Shen, B.-C., and Cheng, D.-S., Development and validation of numerical model of steel fiber reinforced concrete for high-velocity impact. Computational Materials Science, 2008. 42(1): p. 90-99. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Konietzky, H., and Huang, R., Elastic–plastic-hydrodynamic analysis of crater blasting in steel fiber reinforced concrete. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, 2009. 52(2): p. 111-116. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. and Hao, H., Mesoscale modelling and analysis of damage and fragmentation of concrete slab under contact detonation. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 2009. 36(12): p. 1315-1326. [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, A., Musselman, E., Schokker, A.J., and Linzell, D., Behavior of portable fiber reinforced concrete vehicle barriers subject to blasts from contact charges. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 2010. 37(5): p. 521-529. [CrossRef]

- Luccioni, B.M., Aráoz, G.F., and Labanda, N.A., Defining erosion limit for concrete. International Journal of Protective Structures, 2013. 4(3): p. 315-340.

- Yosef, T.Y., Development of advanced computational methodologies and guidelines for modeling impact dynamics of post-granular soil systems, in Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. 2021, University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Ross, H., Sicking, D., Zimmer, R., and Michie, J., Recommended procedures for the safety performance evaluation of highway features, in National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Report 350. 2009, Transportation Research Board: Washington, D.C.

- Saleh, M. and Edwards, L., Evaluation of soil and fluid structure interaction in blast modelling of the flying plate test. Computers & Structures, 2015. 151: p. 96-114. [CrossRef]

- Busch, C.L., Aimone-Martin, C.T., and Tarefder, R.A., Experimental evaluation and finite-element simulations of explosive airblast tests on clay soils. International Journal of Geomechanics, 2016. 16(4): p. 04015097. [CrossRef]

- Tagar, A., Changying, J., Adamowski, J., Malard, J., Qi, C.S., Qishuo, D., and Abbasi, N., Finite element simulation of soil failure patterns under soil bin and field testing conditions. Soil and Tillage Research, 2015. 145: p. 157-170. [CrossRef]

- Linforth, S., Tran, P., Rupasinghe, M., Nguyen, N., Ngo, T., Saleh, M., Odish, R., and Shanmugam, D., Unsaturated soil blast: flying plate experiment and numerical investigations. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 2019. 125: p. 212-228. [CrossRef]

- Symonds, P., Survey of methods of analysis for plastic deformation of structures under dynamic loading, in Division engineering report BU/NSRDC/1–67. 1967, Brown University.

- Schmidt, J., Mongiardini, M., Bielenberg, R.L., K., Reid, J., and Faller, R., Dynamic testing of MGS W6x8.5 posts at decreased embedment, in Final Report to Nebraska Department of Roads, Transportation Research Report No. TRP-03-271-12. 2012, Midwest Roadside Safety Facility, University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Schrum, K., Sicking, D., Faller, R., and Reid, J., Predicting the Dynamic Fracture of Steel via a Non- Local Strain Energy Density Failure Criterion, in Final Report to Federal Highway Administration, MwRSF Research Report No. TRP-03-311-14. 2014, Midwest Roadside Safety Facility, University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Deladi, E.L., Static friction in rubber-metal contacts with application to rubber pad forming processes, in Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. 2006, University of Twente.

- Yoshimi, Y. and Kishida, T., A ring torsion apparatus for evaluating friction between soil and metal surfaces. Geotechnical testing journal, 1981. 4(4): p. 145-152. [CrossRef]

- Uesugi, M. and Kishida, H., Frictional resistance at yield between dry sand and mild steel. Soils and foundations, 1986. 26(4): p. 139-149. [CrossRef]

- Homan, D., Thiele, J., Faller, R., Rosenbaugh, S., Rohde, J., Arens, S., Lechtenberg, K., Sicking, D., and Reid, J., Investigation and dynamic testing of wood and steel posts for MGS on a wire-faced mse wall, in Final Report to the Federal Highway Administration, Transportation Research 2012, Midwest Roadside Safety Facility, University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Mongiardini, M., Ray, M., Plaxico, C., and Anghileri, M., Procedures for verification and validation of computer simulations used for roadside safety applications, in Final Report to the National Cooperative Highway Research Program, NCHRP Report No. W179, Project No. 22-24. 2010, Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

- Meyer, D., Ammon, T., Bielenberg, R., Stolle, C., Holloway, C., and Faller, R., Quasi-static tensile and dynamic impact testing of guardrail components, in Draft Report to the U.S. Army Surface Deployment and Distribution Command Traffic Engineering Agency, Transportation Research Report No. TRP-03-350-17. 2017, Midwest Roadside Safety Facility, University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Reese, L., Qiu, T., Linzell, D., O'hare, E., and Rado, Z., Field tests and numerical modeling of vehicle impacts on a boulder embedded in compacted fill. International Journal of Protective Structures, 2014. 5(4): p. 435-451. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.G., Development of design guidelines for soil embedded post systems using wide-flange I-beams to contain truck impact, in Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. 2011, Texas A&M University.

- Mirdamadi, A., Deterministic and probabilistic simple model for single pile behavior under lateral truck impact, in Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. 2014, Texas A&M University.

Figure 1.

Granular (MASH strong) soil grain sizes ranging from 19.05 mm to silt size.

Figure 1.

Granular (MASH strong) soil grain sizes ranging from 19.05 mm to silt size.

Figure 2.

Computational model geometry, set-up, and initial conditions of a laterally impacted W152x12.6 steel pile embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil.

Figure 2.

Computational model geometry, set-up, and initial conditions of a laterally impacted W152x12.6 steel pile embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil.

Figure 3.

(a) Force vs. displacement and (b) energy vs. displacement plots from simulation and physical impact test.

Figure 3.

(a) Force vs. displacement and (b) energy vs. displacement plots from simulation and physical impact test.

Figure 4.

Post-impact photographs of buckled W152x12.6 steel pile, physical impact test and simulation using erosion method.

Figure 4.

Post-impact photographs of buckled W152x12.6 steel pile, physical impact test and simulation using erosion method.

Figure 5.

Comparison of time sequential images between dynamic impact test (Test No. MH-1) and simulated impact test using erosion method for 1,830-mm long, W152x12.6 steel pile embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil.

Figure 5.

Comparison of time sequential images between dynamic impact test (Test No. MH-1) and simulated impact test using erosion method for 1,830-mm long, W152x12.6 steel pile embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil.

Figure 6.

Von Mises stress distribution within granular (MASH strong) soil in laterally impacted “flexible” or “long” I-shaped W152x12.6 steel pile embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil.

Figure 6.

Von Mises stress distribution within granular (MASH strong) soil in laterally impacted “flexible” or “long” I-shaped W152x12.6 steel pile embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil.

Figure 7.

(a) Force vs. displacement and (b) Energy vs. displacement plots from simulation and physical impact test.

Figure 7.

(a) Force vs. displacement and (b) Energy vs. displacement plots from simulation and physical impact test.

Figure 8.

Time sequential images of dynamic impact test (Test No. BL-8) and simulated test using the erosion method for an 1,830-mm long W152x23.6 steel pile embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil.

Figure 8.

Time sequential images of dynamic impact test (Test No. BL-8) and simulated test using the erosion method for an 1,830-mm long W152x23.6 steel pile embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil.

Figure 9.

Von Mises stress distribution within granular (MASH strong) soil in laterally impacted rigid W152x23.6 steel pile embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil.

Figure 9.

Von Mises stress distribution within granular (MASH strong) soil in laterally impacted rigid W152x23.6 steel pile embedded in granular (MASH strong) soil.

Figure 10.

Baseline mesh size model: (a) initial conditions, model setup, and geometry; and (b) soil mesh pattern in X-Y plane.

Figure 10.

Baseline mesh size model: (a) initial conditions, model setup, and geometry; and (b) soil mesh pattern in X-Y plane.

Figure 11.

Uniform mesh model: (a) model setup geometry, and initial conditions; and (b) soil mesh pattern in X-Y plane.

Figure 11.

Uniform mesh model: (a) model setup geometry, and initial conditions; and (b) soil mesh pattern in X-Y plane.

Figure 12.

(a) Average force vs displacement comparison between baseline and uniform mesh-size simulations and impact test data (i.e., test no. P3G-7) and (b) Average force percentage difference between the baseline and uniform mesh-size simulation and physical impact test (i.e., test no. P3G-7) for 125 mm through 500 mm pile displacements.

Figure 12.

(a) Average force vs displacement comparison between baseline and uniform mesh-size simulations and impact test data (i.e., test no. P3G-7) and (b) Average force percentage difference between the baseline and uniform mesh-size simulation and physical impact test (i.e., test no. P3G-7) for 125 mm through 500 mm pile displacements.

Figure 13.

Computational model geometry, set-up, and initial conditions of laterally impacted, 2,134-mm long, ASTM A500 Grade B steel tube pile embedded in 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d granular (MASH strong) soil domain (Note: figure not drawn to scale).

Figure 13.

Computational model geometry, set-up, and initial conditions of laterally impacted, 2,134-mm long, ASTM A500 Grade B steel tube pile embedded in 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d granular (MASH strong) soil domain (Note: figure not drawn to scale).

Figure 14.

Force vs. displacement and energy vs. displacement comparisons between physical impact test data (i.e., test no. P3G-7) and simulation with: (a) 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d; (b) 2d x 2d x 1.5d; and (c) 2d x 2d x 2d soil domain sizes.

Figure 14.

Force vs. displacement and energy vs. displacement comparisons between physical impact test data (i.e., test no. P3G-7) and simulation with: (a) 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d; (b) 2d x 2d x 1.5d; and (c) 2d x 2d x 2d soil domain sizes.

Figure 15.

Force vs. displacement and energy vs. displacement comparisons between physical impact test data (i.e., test no. P3G-7) and simulation with: (a) 3d x 3d x 2d; (b) 3d x 3d x 3d; and (c) 4d x 4d x 3d soil domain sizes.

Figure 15.

Force vs. displacement and energy vs. displacement comparisons between physical impact test data (i.e., test no. P3G-7) and simulation with: (a) 3d x 3d x 2d; (b) 3d x 3d x 3d; and (c) 4d x 4d x 3d soil domain sizes.

Figure 16.

Computation time as a function of number of CPUs for the six soil domain sizes for: (a) BNR boundary condition and (b) SPC boundary condition.

Figure 16.

Computation time as a function of number of CPUs for the six soil domain sizes for: (a) BNR boundary condition and (b) SPC boundary condition.

Figure 17.

Relationship between computation time and number of soil elements at 8, 16, 32, 64, and 124 CPUs for: (a) BNR boundary condition and (b) SPC boundary condition.

Figure 17.

Relationship between computation time and number of soil elements at 8, 16, 32, 64, and 124 CPUs for: (a) BNR boundary condition and (b) SPC boundary condition.

Table 1.

Fully calibrated granular (MASH strong) soil input parameters [

36].

Table 1.

Fully calibrated granular (MASH strong) soil input parameters [

36].

| Item |

Soil Parameter |

Unit |

Value |

| Soil characteristics parameters |

Specific gravity,

|

[-] |

2.65 |

| Moisture content, |

[%] |

3.4 |

| Density of soil, |

[kg/mm3] |

1.9e-06 |

| Elasticity parameters |

Shear modulus, |

[MPa] |

12.0 |

| Bulk modulus, |

[MPa] |

20.0 |

| Plasticity parameters |

Peak friction angle, |

[Degrees] |

45.0 |

| Cohesion, |

[kPa] |

5.0 |

| Modified MC surface coefficient, |

[kPa] |

3.7 |

| Eccentricity parameter,

|

[-] |

0.7 |

| Viscoplasticity parameters |

Viscoplasticity parameter,

|

[-] |

1.0e-03 |

| Viscoplasticity parameter,

|

[-] |

2.0 |

| Strain softening parameters |

Volumetric strain at initial damage threshold,

|

[-] |

1.0e-05 |

| Void formation energy,

|

[kN/mm] |

6.0e-08 |

| Residual friction angle,

|

[Degrees] |

15 |

Table 2.

Material input parameters for a W152x12.6 ASTM A36 steel pile [

43].

Table 2.

Material input parameters for a W152x12.6 ASTM A36 steel pile [

43].

| Input parameters |

Value |

| Density (kg/mm3) |

7.86e-06 |

| Young's modulus (GPa) |

200 |

| Poisson’s ratio |

0.30 |

| Effective plastic strain |

ep1 |

ep2 |

ep3 |

ep4 |

ep5 |

ep6 |

ep7 |

ep8 |

| 0.000 |

0.0243 |

0.0303 |

0.0368 |

0.0776 |

0.1425 |

0.1794 |

0.9050 |

| Effective stress (GPa) |

es1 |

es2 |

es3 |

es4 |

es5 |

es6 |

es7 |

es8 |

| 0.370 |

0.3701 |

0.4050 |

0.4236 |

0.5026 |

0.5638 |

0.5858 |

0.8731 |

Table 3.

Material input parameters for a W152x23.6 ASTM A992 steel pile [

44].

Table 3.

Material input parameters for a W152x23.6 ASTM A992 steel pile [

44].

| Input parameters |

Value |

| Density (kg/mm3) |

7.86e-06 |

| Young's modulus (GPa) |

200 |

| Poisson’s ratio |

0.30 |

| Effective plastic strain |

ep1 |

ep2 |

ep3 |

ep4 |

ep5 |

ep6 |

ep7 |

ep8 |

| 0.000 |

0.0160 |

0.0470 |

0.0890 |

0.1170 |

0.1410 |

0.1850 |

2.0000 |

| Effective stress (GPa) |

es1 |

es2 |

es3 |

es4 |

es5 |

es6 |

es7 |

es8 |

| 0.439 |

0.4730 |

0.5200 |

0.5610 |

0.5860 |

0.6010 |

0.6210 |

1.8000 |

Table 4.

Average force comparison at pile displacements of 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm between simulation and test nos. MH-1 and MH-4.

Table 4.

Average force comparison at pile displacements of 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm between simulation and test nos. MH-1 and MH-4.

| Item |

Average Force (kN) |

| at 125 mm |

at 250 mm |

at 375 mm |

at 500 mm |

| Test No. MH-1 |

43.19 |

43.56 |

42.55 |

39.87 |

| Test No. MH-4 |

41.99 |

42.79 |

42.49 |

39.66 |

| Test Average |

42.59 |

43.17 |

42.52 |

39.77 |

| SimulatonTest No. MH-1: Erosion Method |

45.30 |

50.78 |

45.68 |

39.70 |

| % Difference: Simulation vs. Test No. MH-1 |

4.8% |

15.3% |

7.1% |

0.4% |

| % Difference: Simulation vs. Test Average |

6.2% |

16.2% |

7.2% |

0.2% |

Table 5.

Average force comparison at pile displacements of 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm between simulation and test nos. BL-8 and BL-20.

Table 5.

Average force comparison at pile displacements of 125 mm, 250 mm, 375 mm, and 500 mm between simulation and test nos. BL-8 and BL-20.

| Item |

Average Force (kN) |

| at 125 mm |

at 250 mm |

at 375 mm |

at 500 mm |

| Test No. BL-8 |

43.09 |

45.49 |

45.89 |

45.24 |

| Test No. BL-20 |

47.16 |

46.03 |

43.68 |

40.47 |

| Test Average |

45.13 |

45.76 |

44.78 |

42.85 |

| Simulation Test No. BL-8: Erosion Method |

54.09 |

51.47 |

44.89 |

40.78 |

| % Difference: Simulation vs. Test No. BL-8 |

22.6% |

12.3% |

2.2% |

10.4% |

| % Difference: Simulation vs. Test Average |

18.1% |

11.8% |

0.3% |

5.0% |

Table 6.

Average force percentage difference between simulation with BNR boundary condition and impact test data (test no. P3G-7) for six soil domain sizes.

Table 6.

Average force percentage difference between simulation with BNR boundary condition and impact test data (test no. P3G-7) for six soil domain sizes.

| Soil domain size |

Average force percentage difference between simulation with BNR and impact test data (test no. P3G-7) [%] |

| At 125 mm |

At 250 mm |

At 375 mm |

At 500 mm |

| 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d |

1.5% |

11.8% |

10.6% |

9.2% |

| 2d x 2d x 1.5d |

3.2% |

10.5% |

10.2% |

9.4% |

| 2d x 2d x 2d |

2.2% |

12.6% |

11.2% |

7.3% |

| 3d x 3d x 2d |

5.1% |

4.1% |

6.2% |

4.7% |

| 3d x 3d x 3d |

6.8% |

3.1% |

4.2% |

3.2% |

| 4d x 4d x 3d |

9.6% |

2.3% |

4.6% |

3.2% |

Table 7.

Average force percentage difference between simulation with SPC boundary condition of the soil domain and impact test data (test no. P3G-7) for six soil domain sizes.

Table 7.

Average force percentage difference between simulation with SPC boundary condition of the soil domain and impact test data (test no. P3G-7) for six soil domain sizes.

| Soil domain size |

Average force percentage difference between simulation with BNR and impact test data (test no. P3G-7) [%] |

| At 125 mm |

At 250 mm |

At 375 mm |

At 500 mm |

| 1.5d x 1.5d x 1.5d |

0.8% |

17.2% |

15.2% |

11.3% |

| 2d x 2d x 1.5d |

0.3% |

17.8% |

15.1% |

12.3% |

| 2d x 2d x 2d |

0.6% |

15.6% |

15.2% |

8.4% |

| 3d x 3d x 2d |

3.4% |

8.5% |

9.6% |

8.1% |

| 3d x 3d x 3d |

4.3% |

5.1% |

5.2% |

6.3% |

| 4d x 4d x 3d |

9.6% |

2.3% |

4.6% |

3.2% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).