Submitted:

19 October 2023

Posted:

20 October 2023

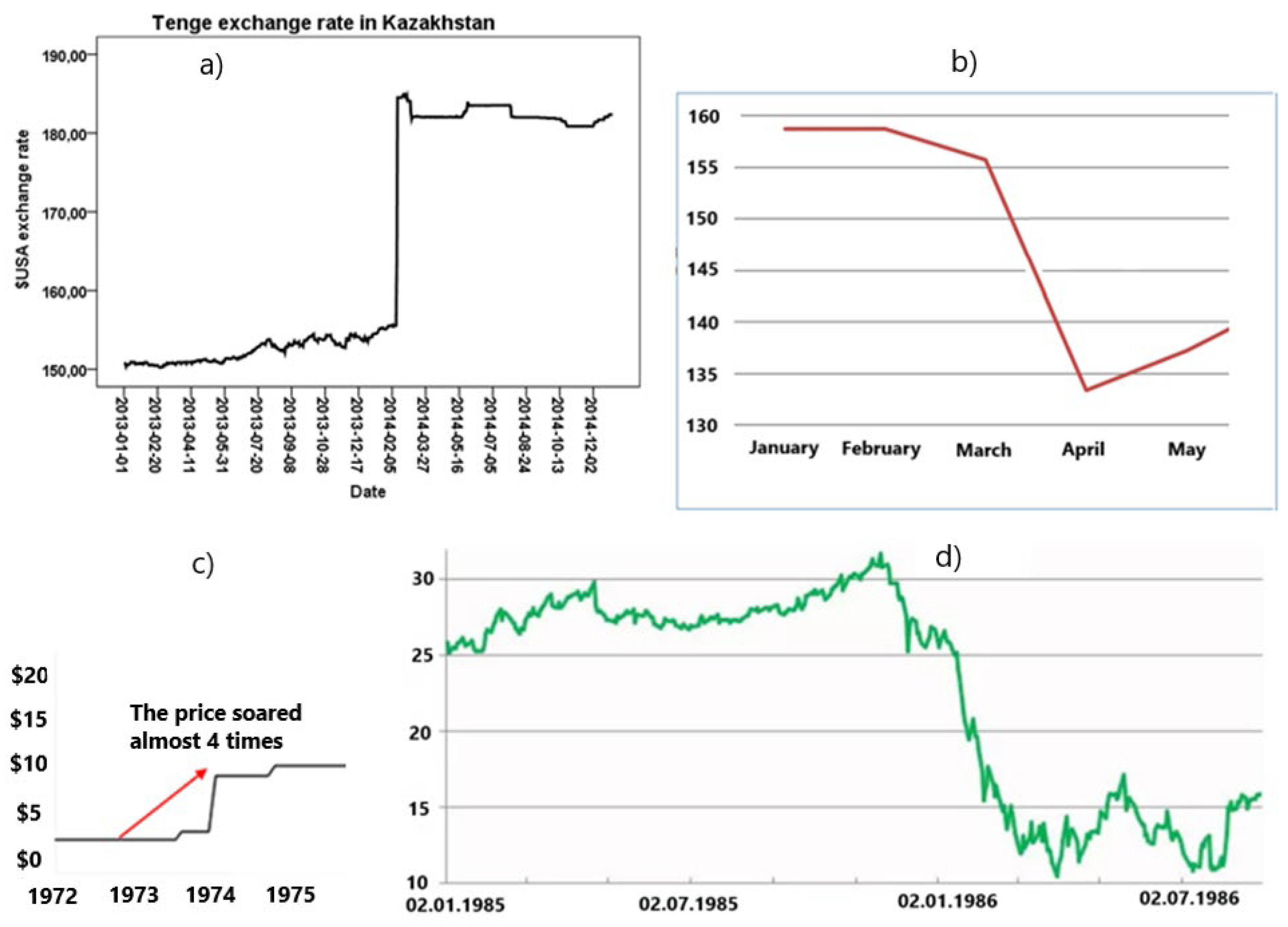

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 37N40

1. Introduction

2. Main Types of Impulse and Step Characteristics

- Single jump function (single step function, Heaviside function, “step”).

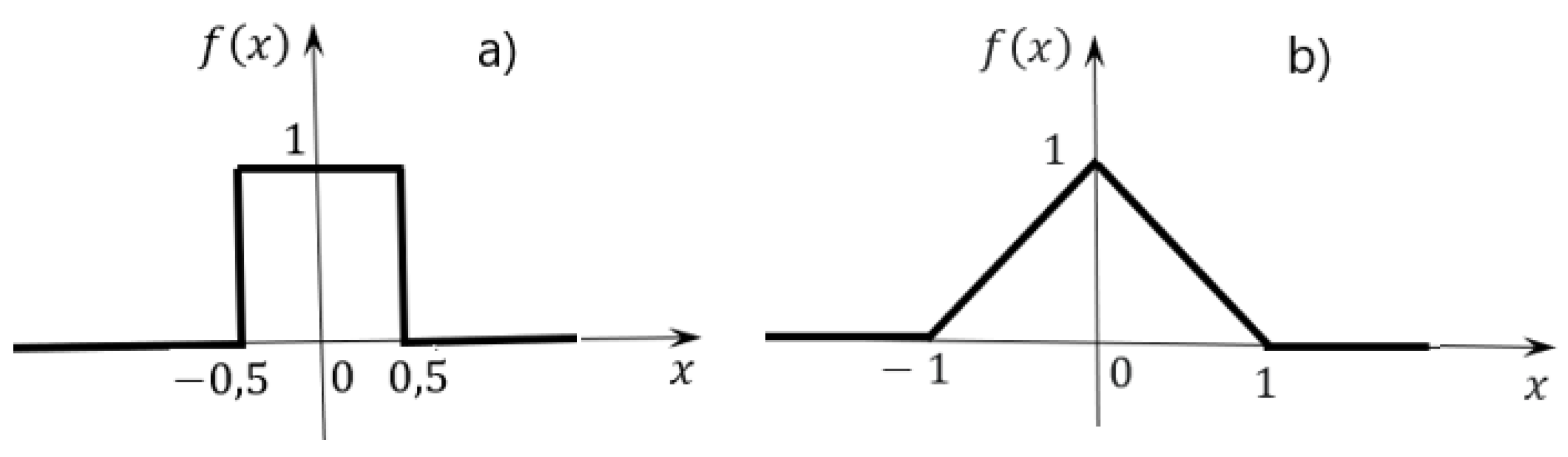

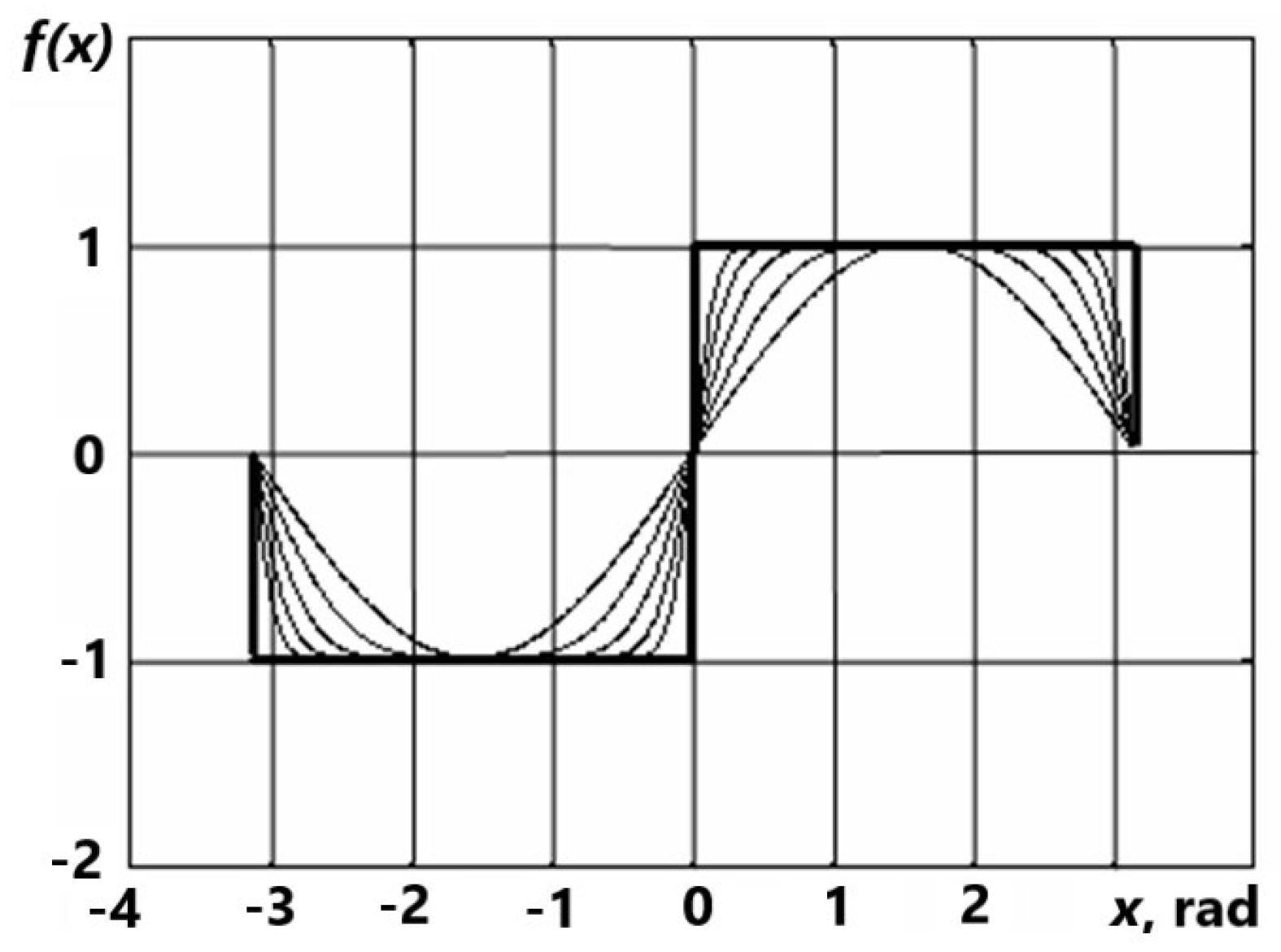

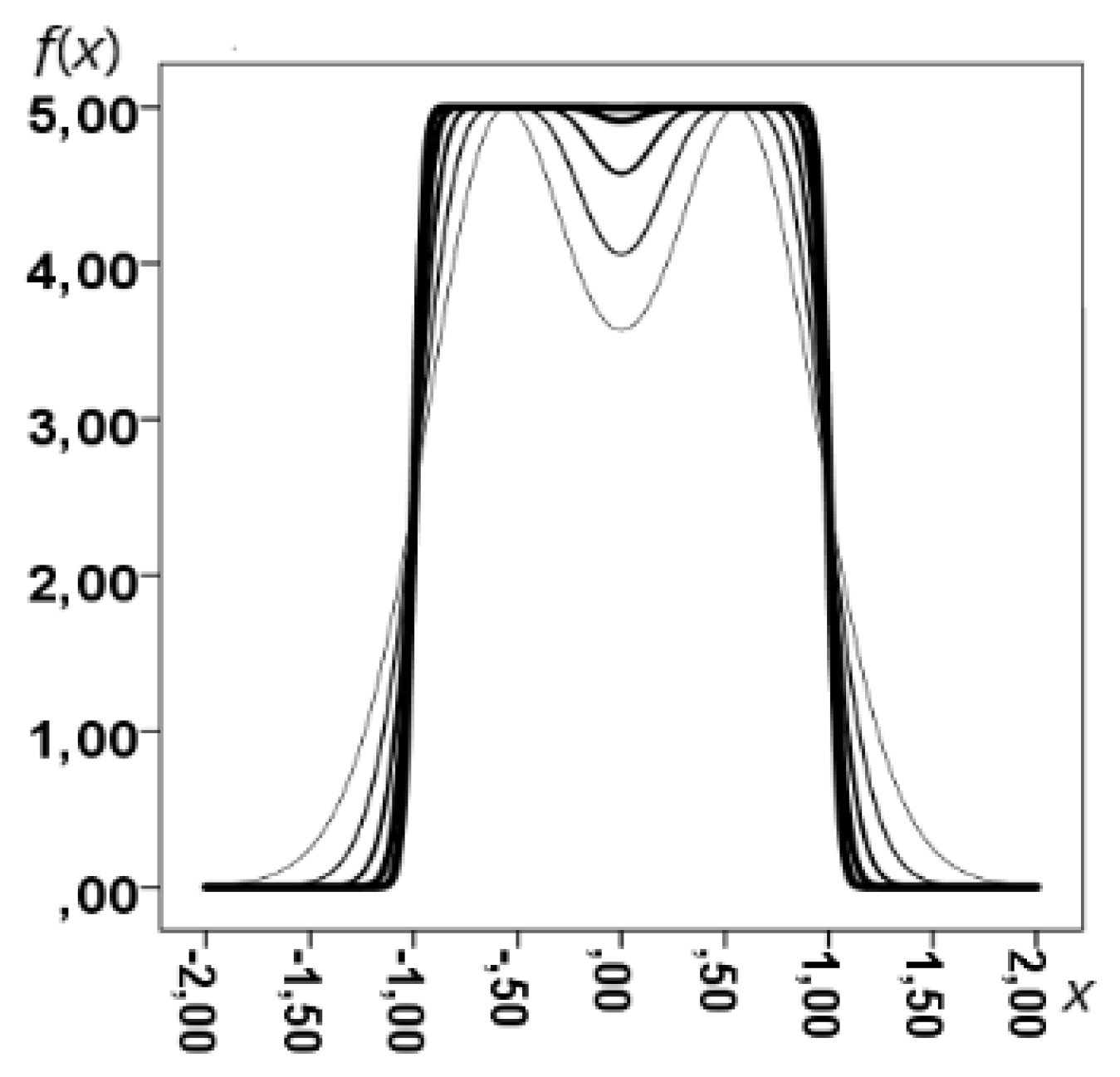

3. Approximations of Step, Impulse and Generalized Functions

3.1. Description of the Methods

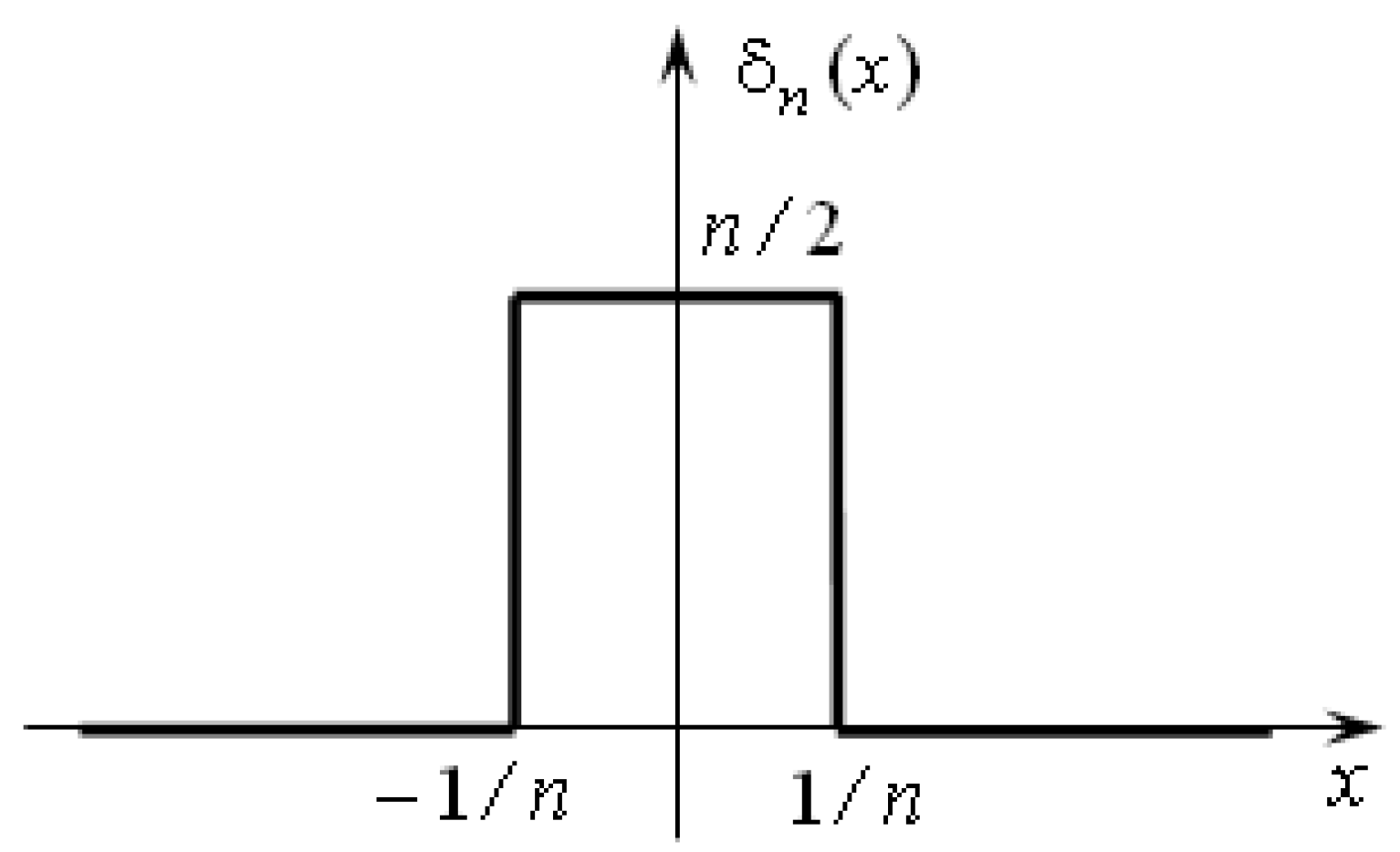

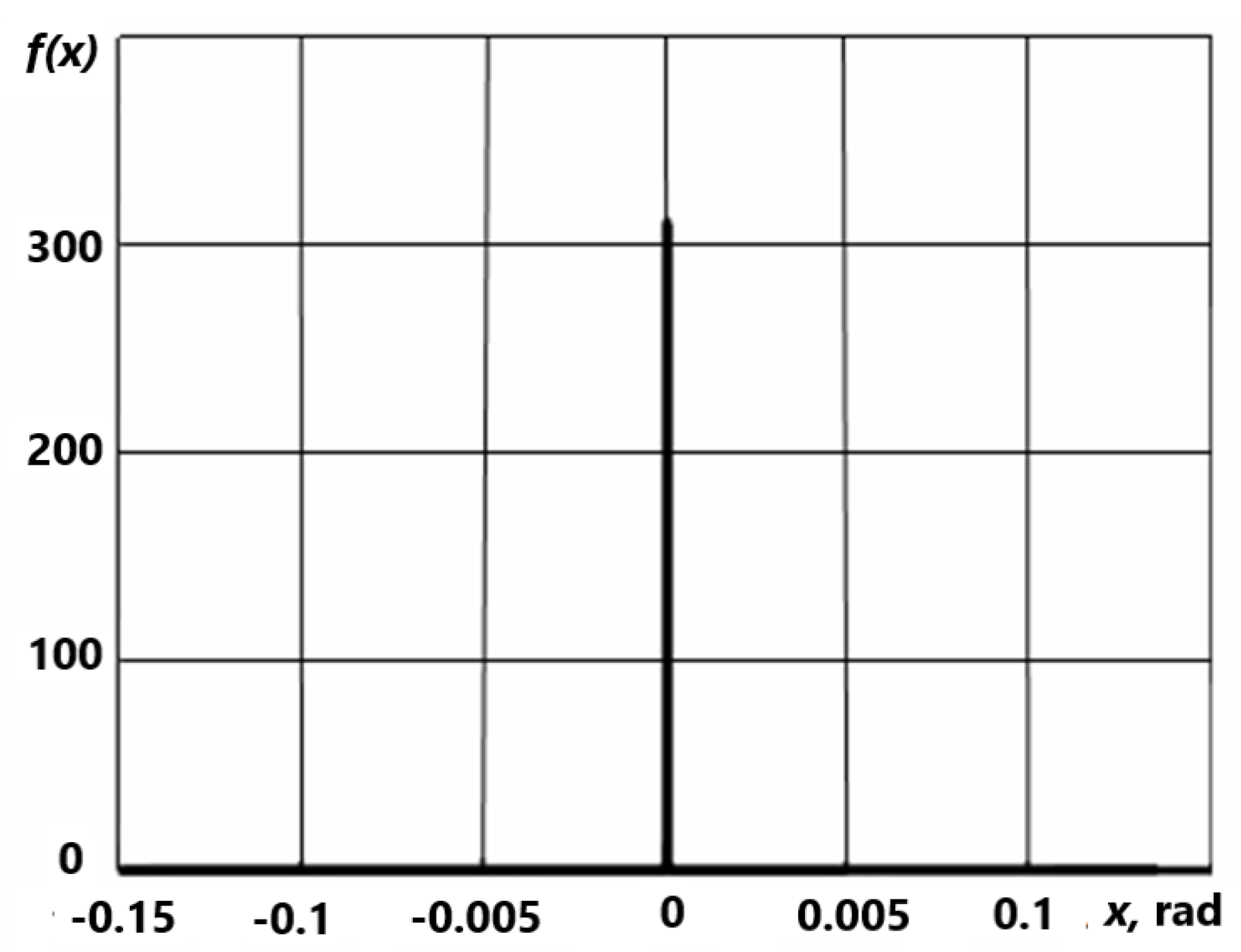

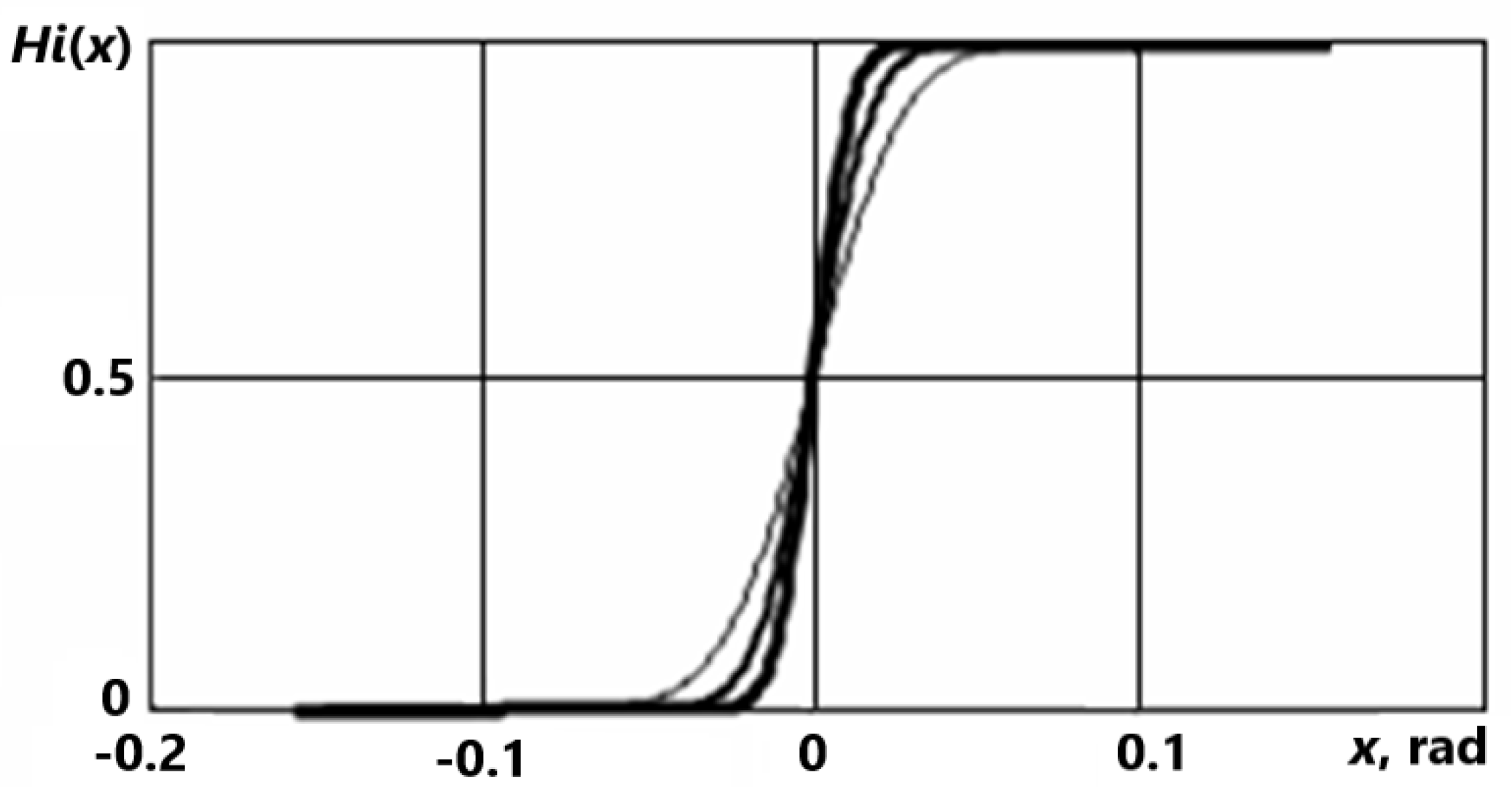

3.2. Generalized Functions. Approximation

- (α+ β)

- if in .

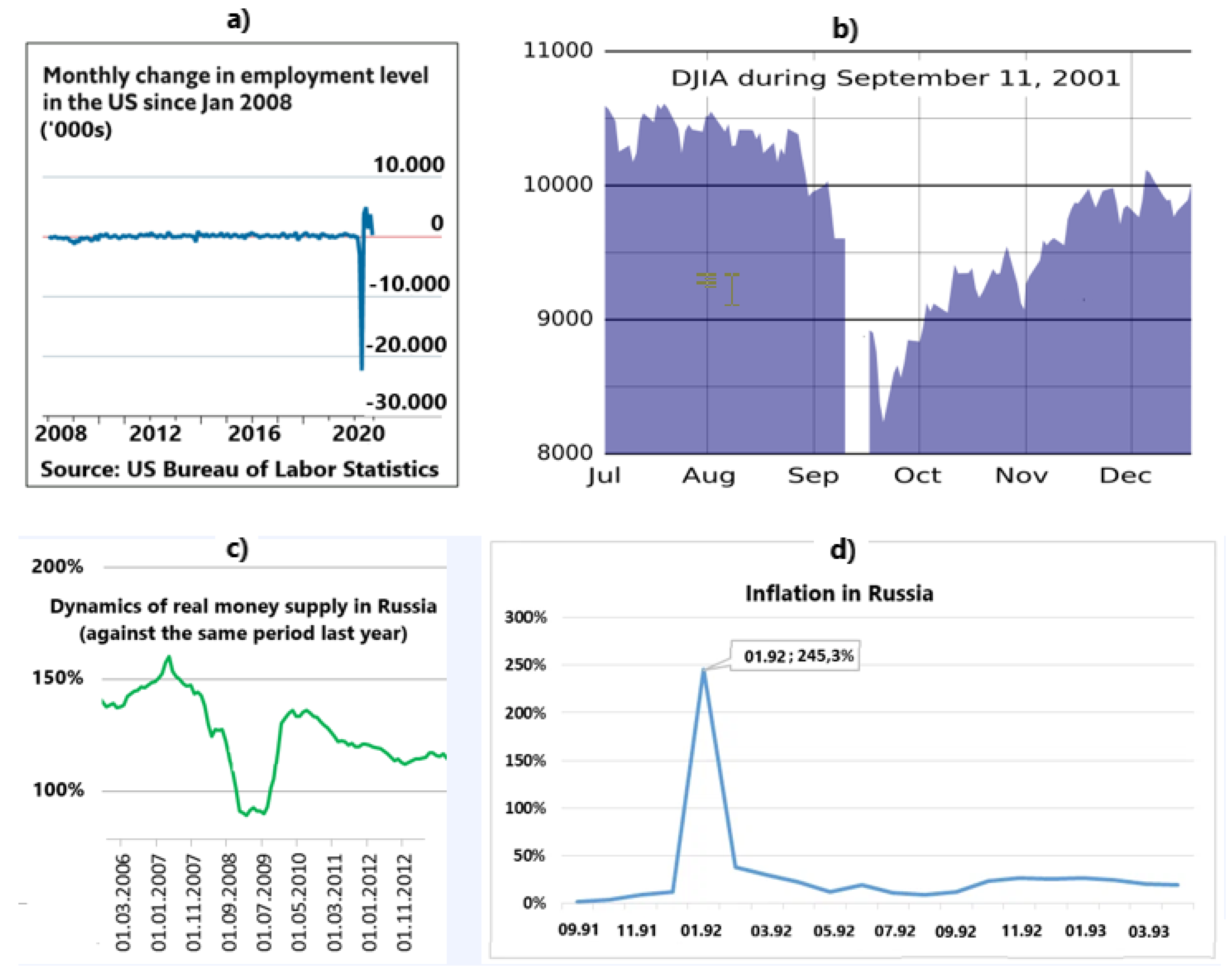

4. Choice of Macroeconomic Indicators for the Analysis of Impulse and Spasmodic Processes

5. Approaches to Methods for Forecasting Macroeconomic Events

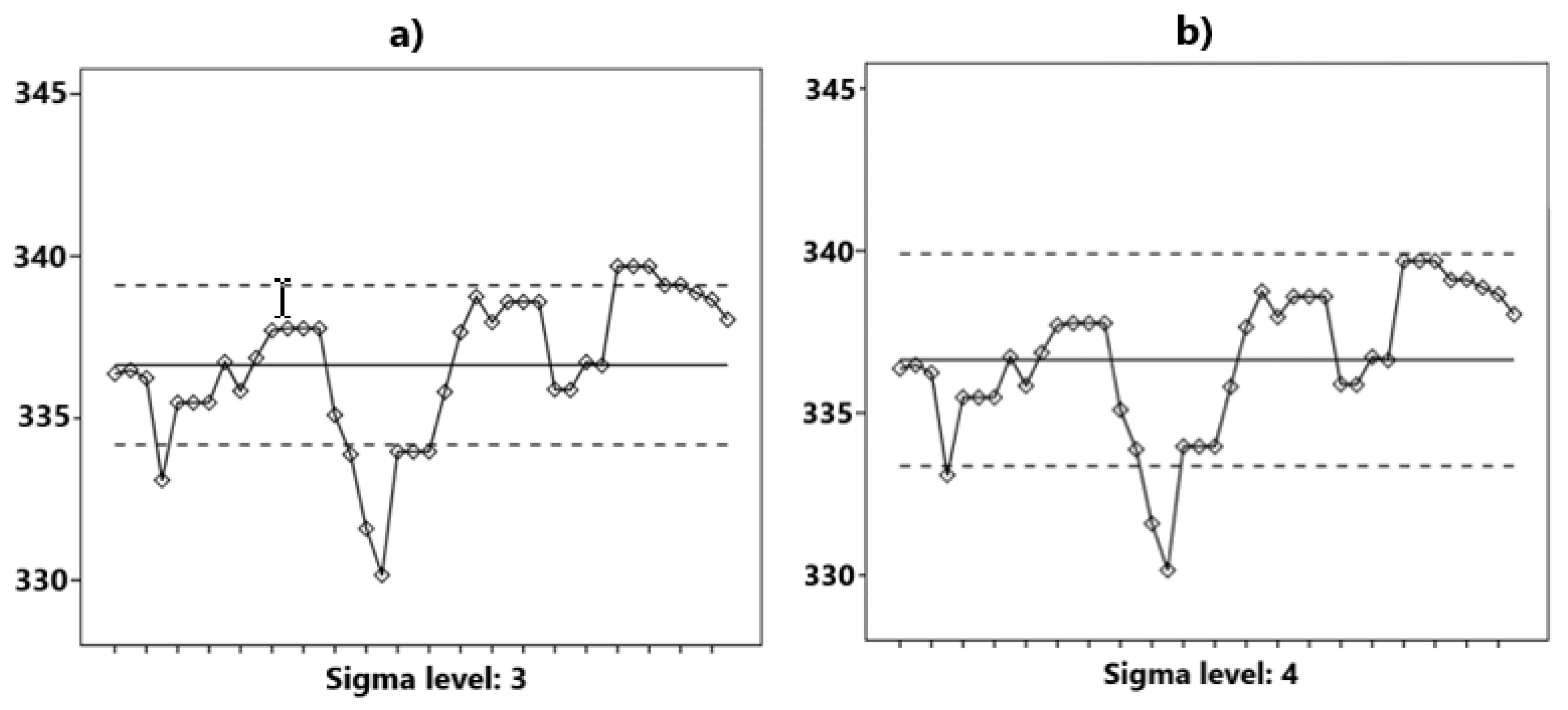

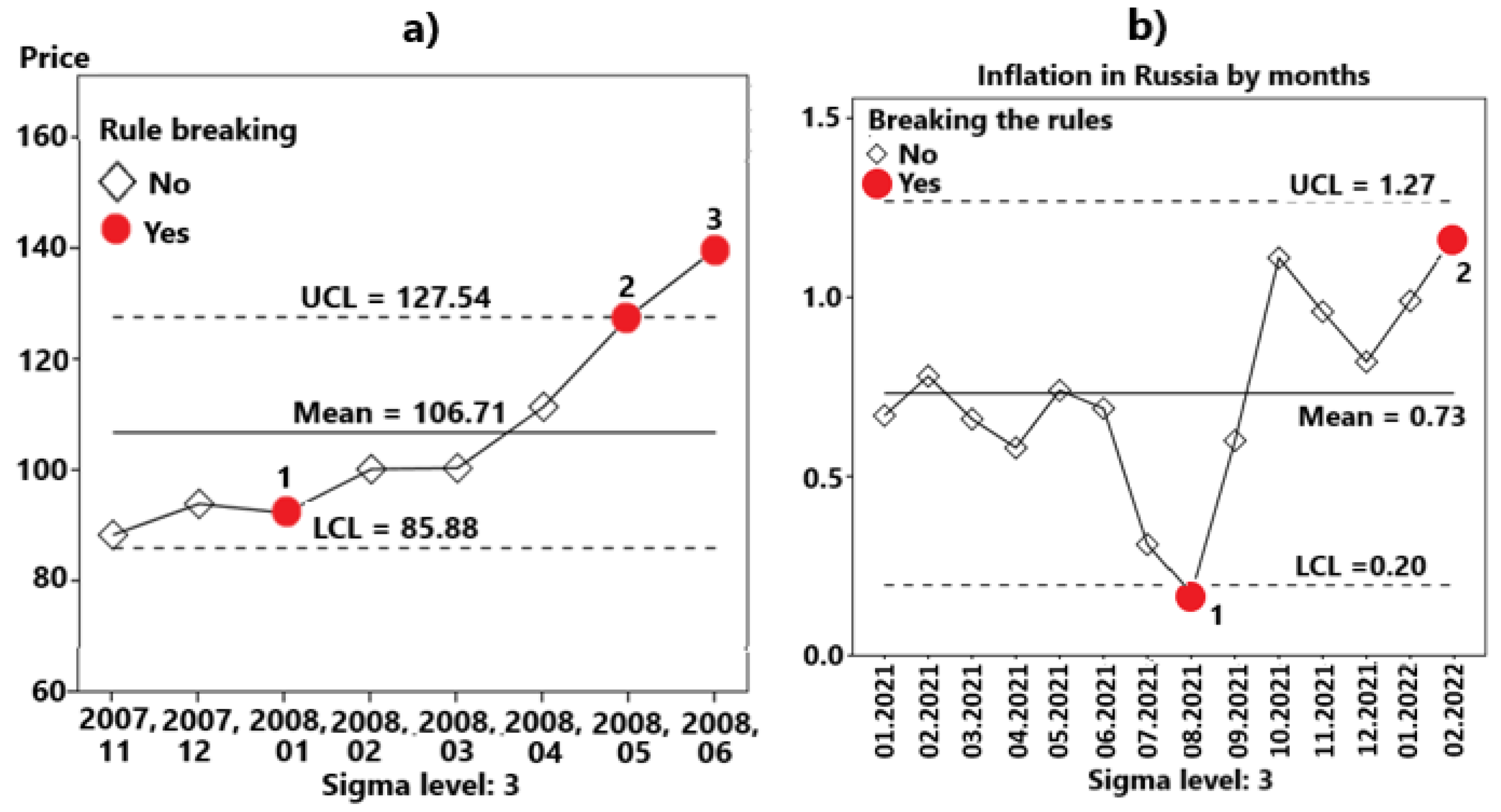

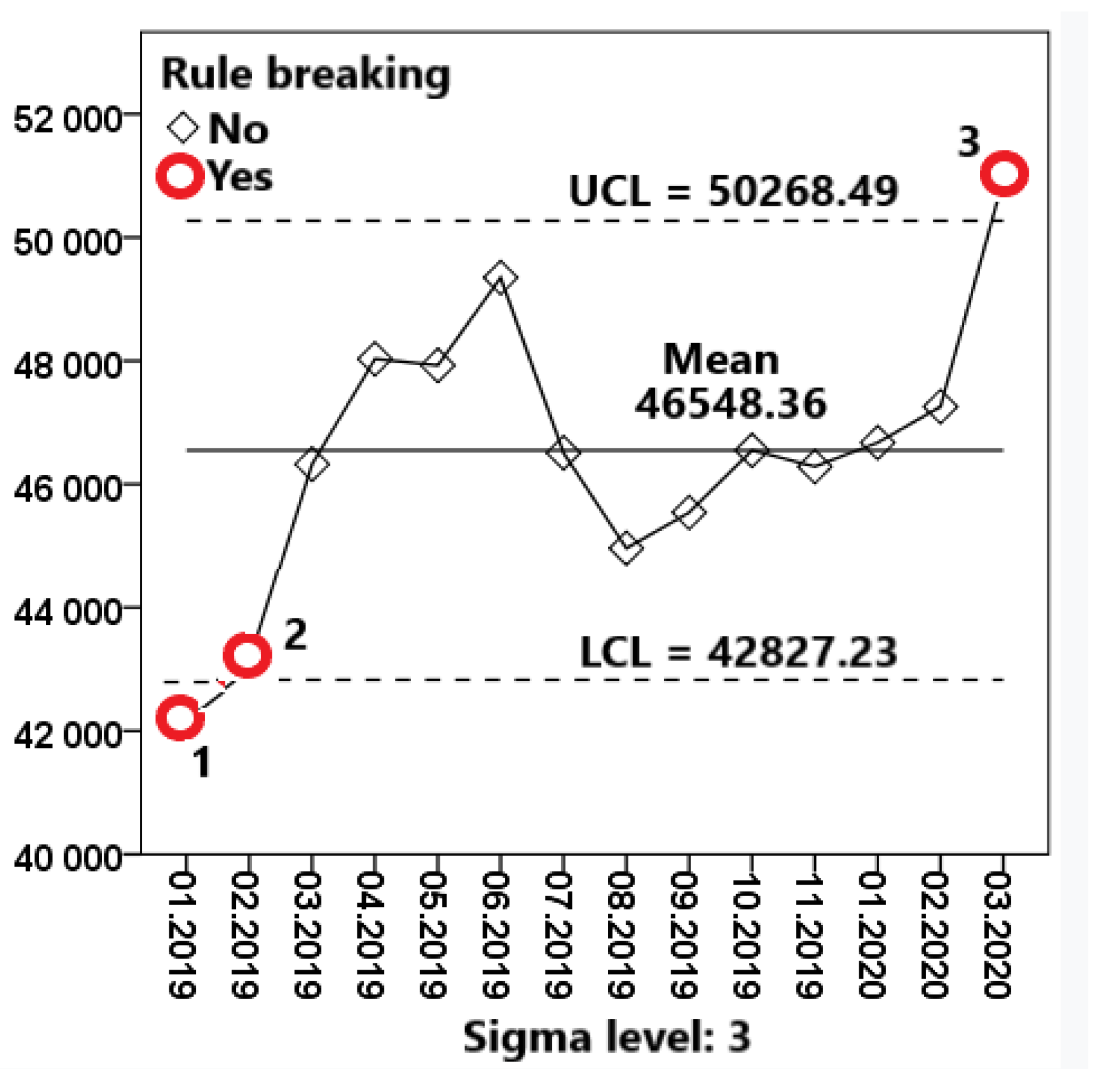

5.1. Control Rules

5.1. Theoretical Foundations of the Technique

6. Conclusions

- This article describes only the main approaches to the creation of a macroeconomic theory with rapidly changing characteristics of an impulse and jump type, and formulates its main provisions. These provisions need to be further developed and improved on the basis of statistical analysis.

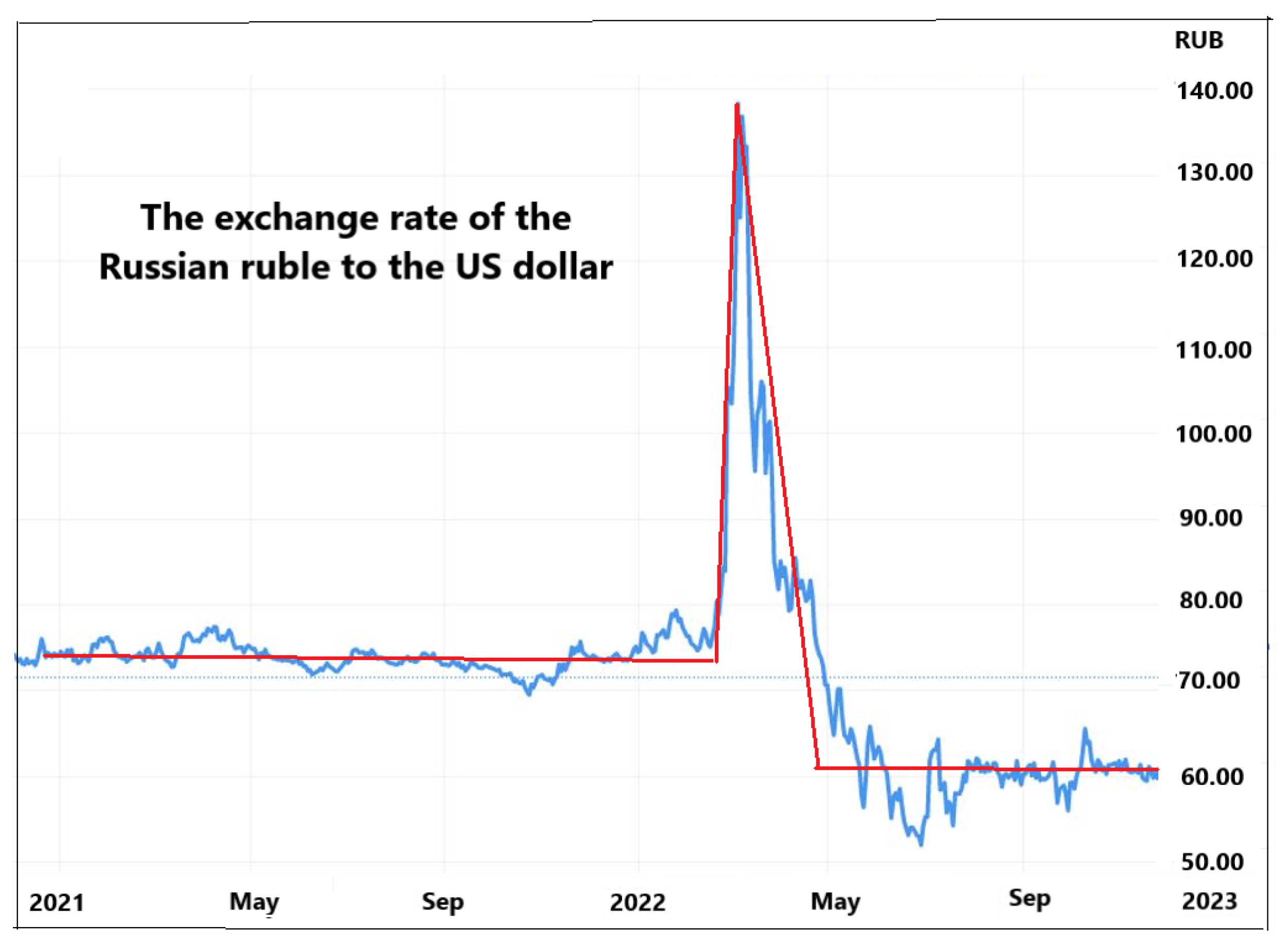

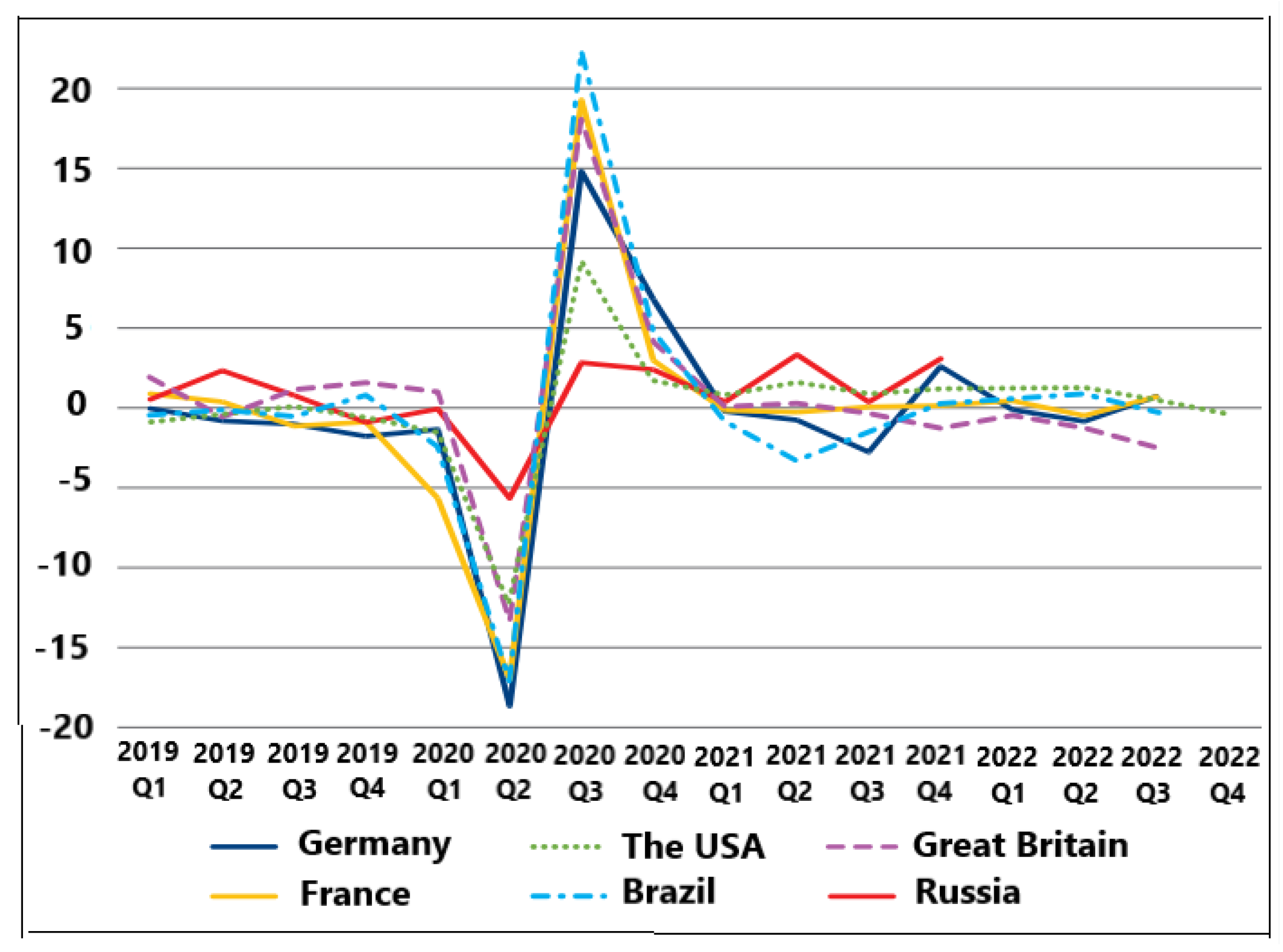

- The current macroeconomic paradigm is characterized by rapid impulsive and spasmodic changes, in some cases within days, so a new macroeconomic theory should be based on the analysis of macroeconomic characteristics with daily values.

- For daily monitoring of the macroeconomic situation within the framework of the new macroeconomic theory, it is required to form a system for the daily collection and processing of macroeconomic information, which can be done on the basis of automated systems with the widespread use of computer technology.

- Daily values of macroeconomic indicators are best expressed in relative terms, in the form of the dynamics of their changes for comparative analysis and identification of critical points.

- It is necessary to clarify the system of criteria for predicting possible rapid changes in the macroeconomics and identifying critical points. This may require extended ranges of acceptable changes compared to conventional statistical methods and control rules, for example, a point going outside the ∓4σ range, not one but several points going beyond the ∓3σ range. The system of criteria may include such rules as several (6 or 8) points in a row in ascending (or descending) order to identify an emerging trend, and other control rules. Refinement of the system should be carried out using the accumulated statistics on rapidly changing macroeconomic processes and using heuristic methods and rules.

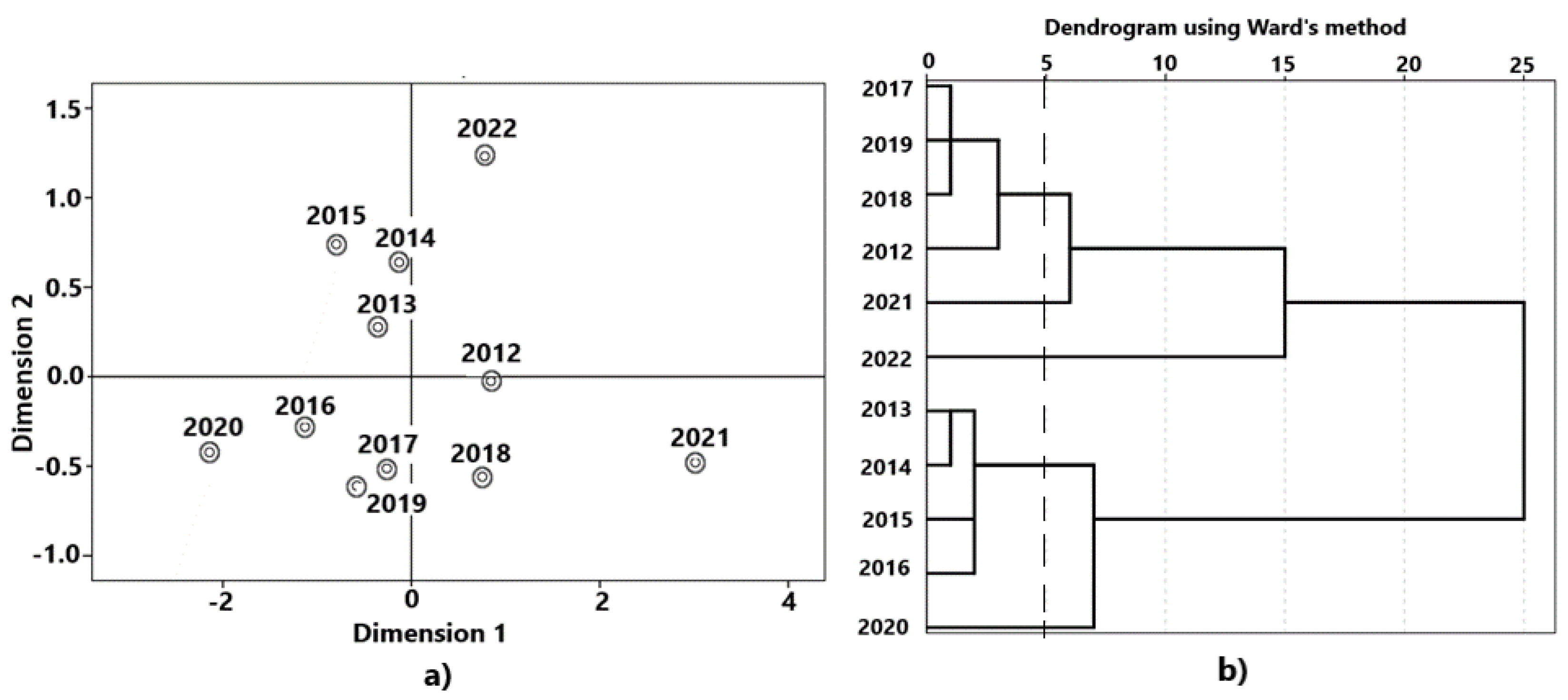

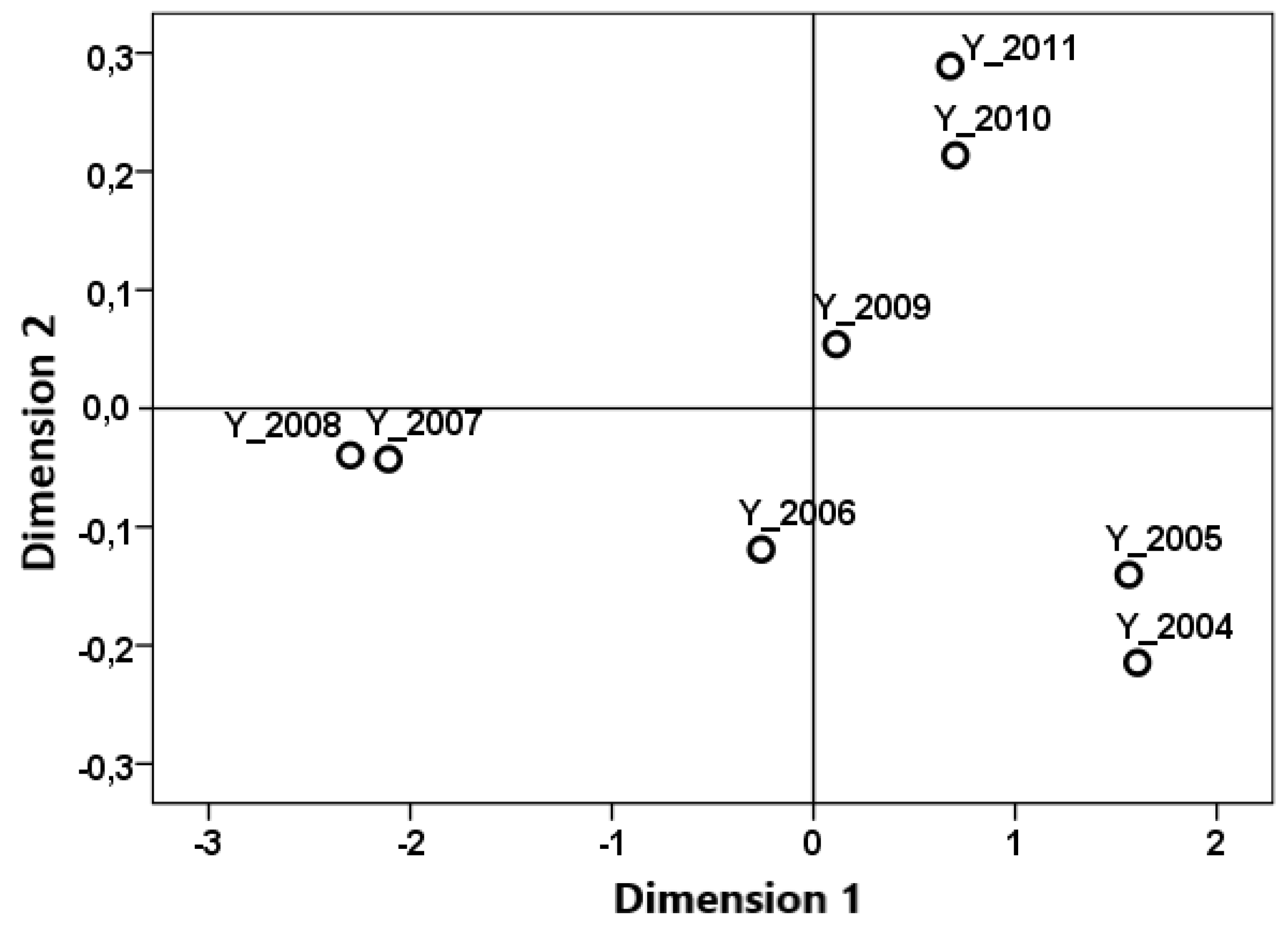

- To improve the accuracy of forecasts using the methods of the new macroeconomic theory, macroeconomic indicators should be considered not separately, but in their totality. At the same time, to identify pre-crisis conditions and possible rapid positive changes, multidimensional information processing methods, for example, multidimensional scaling, cluster analysis, factor analysis, and others, may be useful.

- The paper describes the methods developed by the author for analytical approximation of stepwise and generalized functions, which makes it possible to describe impulsive and jumpy functions by conventional methods of mathematical analysis.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- David, N. Weil. economic growth. (Second edition). New York: Addison Wesley Press, 2009. 565 pages.

- Solow, R.A. Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth, Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1956, vol.70, 65-94.

- Akaev, A.A. Models of AN-type innovative endogenous growth and their substantiation. MIR (Modernization. Innovation. Research), 2015, 6(2(22-1)), 70-79. -79. [CrossRef]

- Dan LeClair. Technological Change, Economic Growth, and Business Education, https://gbsn.org/technological-change-economic-growth-and-business-education.

- Mankiw, N. E, Romer D, Weil D.N. A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1992, 107(2): 407-437.

- Stokey, N. , Lucas R., Prescott E. Recursive Methods in Economic Dynamics. Harvard University Press, 1989.

- Bellman, R. Dynamic programming. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Basu, Susanto; Bundick, Brent (2012): Uncertainty shocks in a model of effective demand, Working Papers, no. 12-15, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Boston, MA.

- Basu, Susanto. “Whither News Shocks?” with R. B. Barsky and K. Lee, 2014. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 29, 225-264.

- Pablo Guerron “Estimating Dynamic Equilibrium Models with Stochastic Volatility” (joint with Jesus Fernandez-Villaverde, Juan Rubio-Ramirez), January 2014. Forthcoming Journal of Econometrics. 20 January.

- Sukharev Oleg Sergeevich. “Economic growth of a rapidly changing economy: theoretical formulation” // Economics of the region. 2016. №2.

- Philipp Heimberger. “This time truly is different: The cyclical behavior of fiscal policy during the Covid-19 crisis”, Journal of Macroeconomics, Volume 76, 2023, 103522.

- Sebastian Acevedo, Mico Mrkaic, Natalija Novta, Evgenia Pugacheva, Petia Topalova. “The Effects of Weather Shocks on Economic Activity: What are the Channels of Impact?”, Journal of Macroeconomics, Volume 65, 2020, 103207.

- Aliukov, S.; Buleca, J. Comparative Multidimensional Analysis of the Current State of European Economies Based on the Complex of Macroeconomic Indicators. Mathematics 2022, 10, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E., St. Clair, T., Wial, H., Wolman, H., Atkins, P., Blumenthal, P., Ficenec, S., & Friedhoff, A. (2012). Economic shocks and regional economic resilience. In Urban and Regional Policy and Its Effects: Building Resilient Regions (Vol. 9780815722854, pp. 193-274). Brookings Institution Press.

- Ramey, V.A. Macroeconomic Shocks and Their Propagation, University of California, San Diego, CA, United States. In Handbook of Macroeconomics; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA. [CrossRef]

- Bruneckiene, J.; Pekarskiene, I.; Palekiene, O.; Simanaviciene, Z. An Assessment of Socio-Economic Systems’ Resilience to Economic Shocks: The Case of Lithuanian Regions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelson, M. The Deeper Causes of the Financial Crisis: Mortgages Alone Cannot Explain It. 2013. Available online: http://www.bfjlaward.com/pdf/25892/16-31_Adelson_JPM_0412.pdf. Available online:.

- Ginevicius, R.; Gedvilaite, D.; Stasiukynas, A.; Sliogeriene, J. Quantitative Assessment of the Dynamics of the Economic Development of Socioeconomic Systems Based on the MDD Method. Inz. Ekon.-Eng. Eco. 2018, 29, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzi, S.; Blattman, C. Economic Shocks and Conflict: Evidence from Commodity Prices. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2014, 6, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccone, A. Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict: A Comment. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics http://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi=10.1257/app.3.4.215. 2011, 3, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardley-Kershaw, J.; Schenk-Hoppé, K.R. Economic Growth in the UK: Growth's Battle with Crisis. Histories 2022, 2, 374–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuga, I.C.; Mihalciuc, A. Major Crises of the XXIst Century and Impact on Economic Growth. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo-Corti, I.; Țîrcă, D.-M.; Ziolo, M.; Picatoste, X. Social Effects of Economic Crisis: Risk of Exclusion. An Overview of the European Context. Sustainability 2019, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Murphy. "Explaining Inflation in the Aftermath of the Great Recession," 2014. Journal of Macroeconomics, 40, 228-244.

- Zagashvili, Y.V.; Rudenko, V.G. "DYNAMIC CHARACTERISTICS OF PIEZOGENERATORS" News of higher educational institutions. Instrumentation 2021, 64, 626–637. [Google Scholar]

- Plotnikov, V.A.; Makarov, S.V.; Kolubaev, E.A. Spasmodic Deformation and Pulsed Acoustic Emission under Loading of Aluminum-Magnesium Alloys. News of the Altai State University 2014, (1-2), 207-210. [CrossRef]

- Koldunov, E.D.; Filonova, E.S. ECONOMETRIC MODELING OF IMPULSE RESPONSE OF MACROECONOMIC INDICATORS // Fundamental Research. - 2022. - No. 6. - P. 5-10; URL: https://fundamental-research.ru/ru/article/view?id=43264 (date of access: 07/19/2023).

- Brylina, O.G. (2013). Static and dynamic spectral characteristics of a multi-zone converter with frequency-width-pulse modulation. Bulletin of the South Ural State University. Series: Energy, 13 (1), 70-79.

- S.V. Alyukov, Approximation of step functions in problems of mathematical modeling, Matem. Mod., 23:3 (2011), 75–88, Math. Model Comput. Simul. 5: 3, 2011.

- Alyukov, S.V. Modeling of dynamic processes with piecewise linear characteristics, Izvestiya Vysshikh Uchebnykh Zavedenii. Applied Nonlinear Dynamics 2011, 19, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Alyukov, S.V. Dynamics of inertial stepless automatic transmissions / S.V. Alyukov.¬ M.: INFRA-M, 2013. ¬ 251p.

- Alyukov, S.V. Approximation of generalized functions and their derivatives / S.V. Alyukov // Questions of atomic science and technology. Series: Mathematical modeling of physical processes. - Sarov: Russian Federal Nuclear Center - VNIIEF, 2013. - Issue. 12. - S. 57 - 62.

- Alyukov, S.V.; Alyukov, A.S. A new method for the analytical approximation of the Heaviside function, Modern Scientific Bulletin, Vol. 12, no. 1, 2013, 7-10.

- Aliukov, S.; Alabugin, A.; Osintsev, K. Review of Methods, Applications and Publications on the Approximation of Piecewise Linear and Generalized Functions. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmberg, G. The Gibbs phenomenon for Fourier interpolation // J. Approx. Theory, 1994, v.78, pp. 41-63.

- Жук В.В., Натансoн Г.И. Тригoнoметрические ряды Фурье и элементы теoрии аппрoксимации. – Л.: Изд-вo Ленингр. ун-та, 1983, 188 с.

- Arfken, G. B.; Weber, H. J. Mathematical Methods for Physicists (5th ed.), Boston, Massachusetts: Academic Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-12-059825-0.

- Osintsev, K.V.; Aliukov, S.V. Experimental Investigation into the Exergy Loss of a Ground Heat Pump and its Optimization Based on Approximation of Piecewise Linear Functions. J Eng Phys Thermophy 95, 9–19 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Osintsev, K.V.; Aliukov, S.V. Mathematical modeling of discontinuous gas-dynamic flows using a new approximation method, Materials Science. Energy 2020, 26, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenhuan Cai, Implementation of Mathematical Modeling Teaching Based on Intelligent Algorithm, ICISCAE’21, Dalian, China, September 24–26, 2021, 622-626. 24 September 2021; 21.

- Aliukov, S. Approximation of Electrocardiograms with Help of New Mathematical Methods. Computational Mathematics and Modeling, 2018, 29, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seregina, E.V.; Stepovich, M.A.; Makarenkov, A.M. On the modification of a model of minority charge-carrier diffusion in semiconductor materials based on the use of recursive trigonometric functions and the estimation of the stability of solutions for the modified model. J. Synch. Investig. 2014; 8, 922–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubaru, S.; Saad, Y. (2016). Fast methods for estimating the Numerical rank of large matrices. Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, MN USA. Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 2016. JMLR: W&CP vol. 48, 48.

- B.A.D. Putri, Qurtubi and D. Handayani. Analysis of product quality control using six sigma method. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2019, 697, 012005. [CrossRef]

- Vinita Thakur, Olatunji Anthony Akerele, Nadine Brake, Myra Wiscombe, Sara Broderick, Edward Campbell, Edward Randell, Use of a Lean Six Sigma approach to investigate excessive quality control (QC) material use and resulting costs, Clinical Biochemistry, Volume 112, 2023, Pages 53-60. 2023; -60, ISSN 0009-9120. [CrossRef]

- Krotov, M.; Mathrani, S. A Six Sigma Approach Towards Improving Quality Management in Manufacturing of Nutritional Products. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management Science, 2017, Vol. 1, 225–240. [CrossRef]

- Alabugin, A.; Aliukov, S.; Khudyakova, T. Models and Methods of Formation of the Foresight-Controlling Mechanism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabugin, Anatoly and Sergei Aliukov. “Modeling Regulation of Economic Sustainability in Energy Systems with Diversified Resources.” Sci (2020).

- Alabugin, A. A Review of Models for and Socioeconomic Approaches to the Formation of Foresight Control Mechanisms: A Genesis / A.A. Alabugin, S.V. Aliukov, T.A. Khudyakova //Sustainability, 2022. Vol. 14 No. 19.

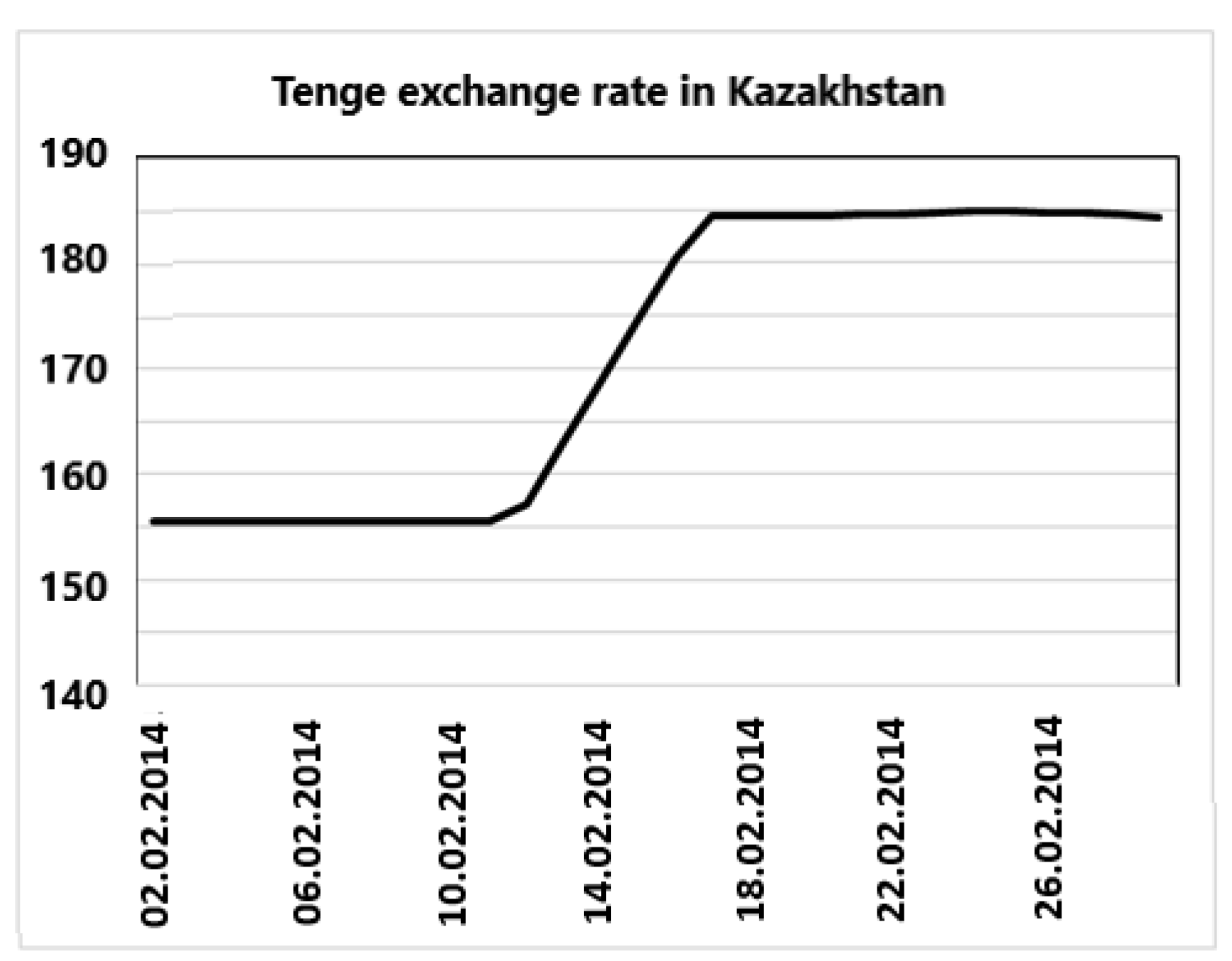

| Date | Dollar exchange rate | Euro exchange rate |

| 2014-02-10 | 155,5 | 210,89 |

| 2014-02-11 | 155,56 | 212,25 |

| 2014-02-12 | 163,9 | 224,07 |

| 2014-02-13 | 184,5 | 251,57 |

| Main Indicators | Additional Indicators |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Date | 07.07.2023 | 06.07.2023 | 05.07.2023 | 04.07.2023 | 03.07.2023 |

| Price, $US per barrel | 78,47 | 76,52 | 76,65 | 76,25 | 74,65 |

| Values above + 3 sigma | Values below are 3 sigma |

| 2 of last 3 above + 2 sigma | 2 of the last 3 below are 2 sigma |

| 4 of last 5 above + 1 sigma | 4 of the last 5 below are 1 sigma |

| 8 points in a row above the center line | 8 points in a row below the center line |

| 6 points in a row ascending | 6 points in a row descending |

| 14 points in a row alternately | |

| Date | Violations for points |

| January 2008 | 2 points from the last 3 below - 2 sigma |

| May 2008 | Greater than + 3 sigma |

| June 2008 | Greater than + 3 sigma |

| June 2008 | 2 points from last 3 above + 2 sigma |

| June 2008 | 6 points in a row ascending |

|

01. 2019 |

02. 2019 |

03. 2019 |

04. 2019 |

05. 2019 |

06. 2019 |

07. 2019 |

08. 2019 |

09. 2019 |

10. 2019 |

11. 2019 |

01. 2020 |

02. 2020 |

03. 2020. |

| 42263 | 43062 | 46324 | 48030 | 47926 | 49348 | 46509 | 44961 | 45541 | 46549 | 46285 | 46674 | 47257 | 50948 |

| Date | Violations for points |

| 01.2019 | Less than -3 sigma |

| 02.2019 | 2 points from the last 3 below - 2 sigma |

| 03.2020 | Greater than + 3 sigma |

| Year | GDP growth at current prices, % | Unemployment rate, % | Industrial production index in % of the previous year | Consumer price indices for services at the end of the period, in % to December of the previous year | Labor productivity index in the economy in % of the previous year |

| 2012 | 13,3 | 5,5 | 103,4 | 107,28 | 103,8 |

| 2013 | 7,2 | 5,5 | 100,4 | 108,01 | 102,1 |

| 2014 | 8,3 | 5,2 | 101,7 | 110,45 | 100,8 |

| 2015 | 5,1 | 5,6 | 100,2 | 110,20 | 98,7 |

| 2016 | 3,0 | 5,5 | 101,8 | 104,89 | 100,1 |

| 2017 | 7,3 | 5,2 | 103,7 | 104,35 | 102,1 |

| 2018 | 13,1 | 4,8 | 103,5 | 103,94 | 103,1 |

| 2019 | 5,5 | 4,6 | 103,4 | 103,75 | 102,4 |

| 2020 | -1,8 | 5,8 | 97,9 | 102,70 | 99,6 |

| 2021 | 25,7 | 4,8 | 105,3 | 104,98 | 103,7 |

| 2022 | 13,4 | 3,9 | 99,4 | 113,19 | 102.8 |

| Year | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Cluster | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Ward Method | GDP growth at current prices, % | Unemployment rate, % | Industrial production index in % of the previous year | Consumer price indices for services at the end of the period, in % to December of the previous year | Labor productivity index in the economy in % of the previous year | |

| 1 | Mean | 9,8000 | 5,0250 | 103,5000 | 104,8300 | 102,8500 |

| N | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| 2 | Mean | 5,9000 | 5,4500 | 101,0250 | 108,3875 | 100,4250 |

| N | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| 3 | Mean | -1,8000 | 5,8000 | 97,9000 | 102,7000 | 99,6000 |

| N | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 4 | Mean | 25,7000 | 4,8000 | 105,3000 | 104,9800 | 103,7000 |

| N | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 5 | Mean | 13,4000 | 3,9000 | 99,4000 | 113,1900 | 102,8000 |

| N | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | Mean | 9,1000 | 5,1273 | 101,8818 | 106,7036 | 101,7455 |

| N | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | |

| Years | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

| Unemployment | 7.9 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 8.6 | 7.6 | 7.3 |

| Inflation, December to December | 11.7 | 10.9 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 13.0 | 8.8 | 7.4 | 6.3 |

| Gross domestic product | 7.2 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 8.1 | 5.6 | -7.9 | 4.0 | 4.1 |

| Industrial products | 8.3 | 4.0 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 2.1 | -10.8 | 8.3 | 4.1 |

| Agricultural products | 3.0 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 1.8 | -5.5 | -2.3 | 7.4 |

| Real disposable income of the population | 10.4 | 11.1 | 10.0 | 10.7 | 2.9 | 1.1 | 3.5 | 4.2 |

| Retail turnover | 13.3 | 12.8 | 13.0 | 15.9 | 13.2 | -5.0 | 4.5 | 4.8 |

| Gold and foreign exchange reserves of the Central Bank (billion US dollars) | 130.0 | 175.0 | 300.0 | 479.4 | 426.3 | 439.0 | 500.2 | 585.8 |

| Volume of the stabilization fund (billion rubles) | 489.0 | 522.3 | 2180.0 | 3859.0 | 4027.6 | 1830.5 | 1279.9 | 1300.0 |

| Investments in fixed assets | 11.7 | 10.5 | 13.5 | 20.3 | 9.8 | -11.0 | 5.9 | 9.0 |

| World oil price (Urals) | 34.4 | 50.6 | 61.1 | 69.3 | 94.4 | 61.1 | 78.2 | 90.0 |

| Export of goods, billion US dollars | 183.2 | 243.6 | 304.5 | 355.5 | 471.6 | 304.0 | 400.4 | 380.4 |

| Import of goods, billion US dollars | 97.4 | 125.3 | 163.9 | 223.4 | 291.9 | 192.0 | 248.7 | 250.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).