Submitted:

18 October 2023

Posted:

18 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Sample Preparation

2.2. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

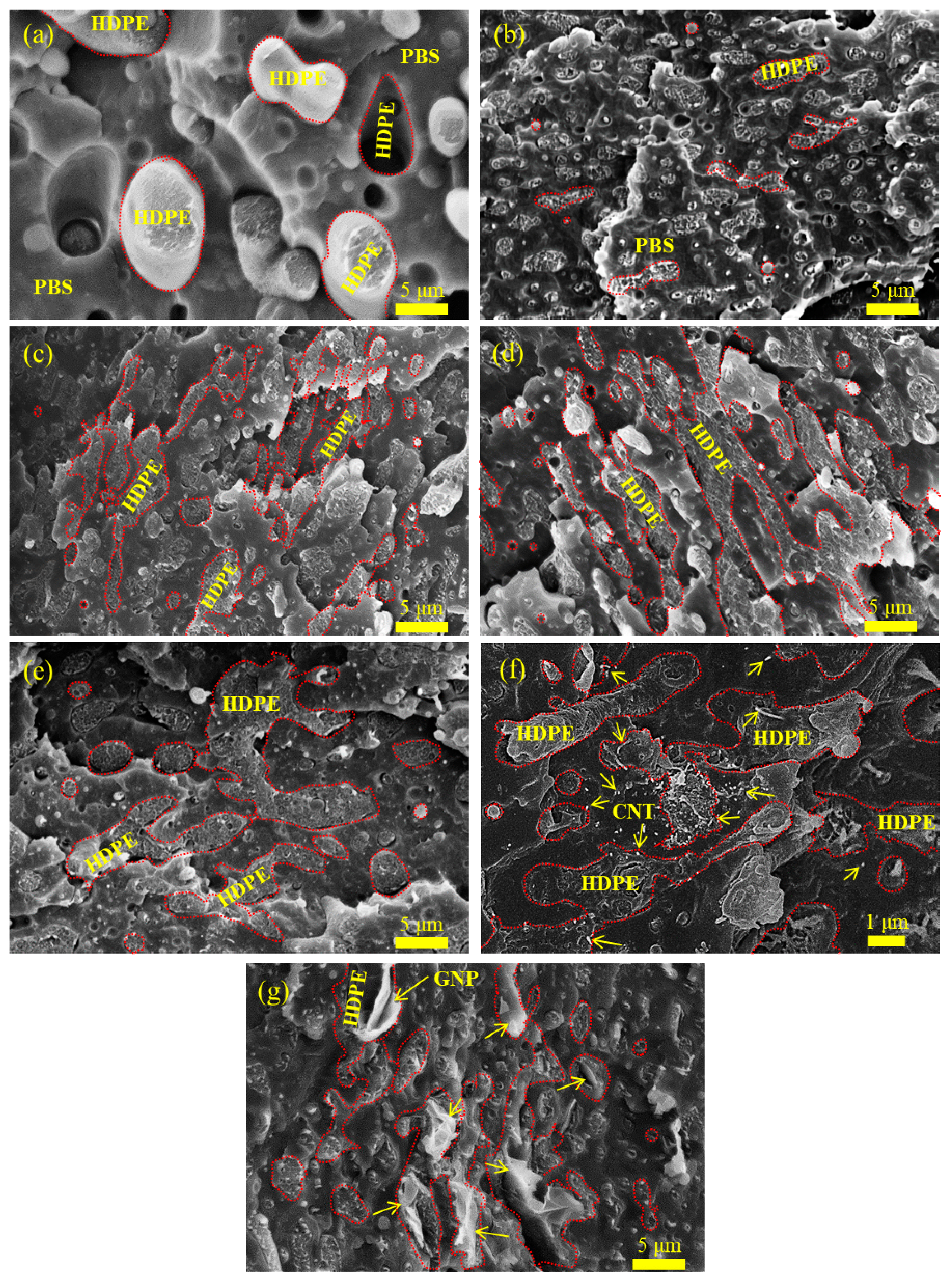

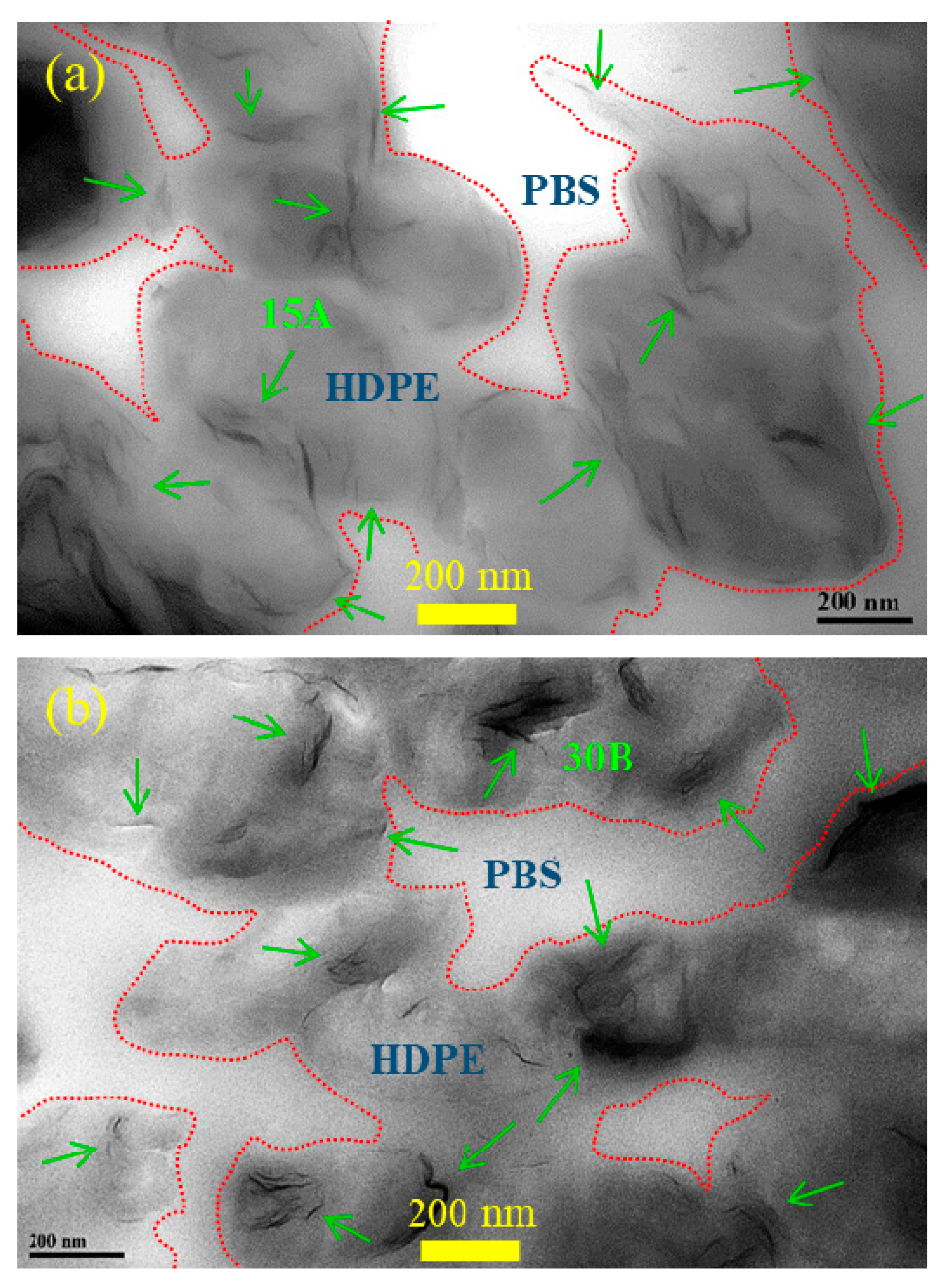

3.1. Phase Morphology and Selective Localization of Nanofiller(s)

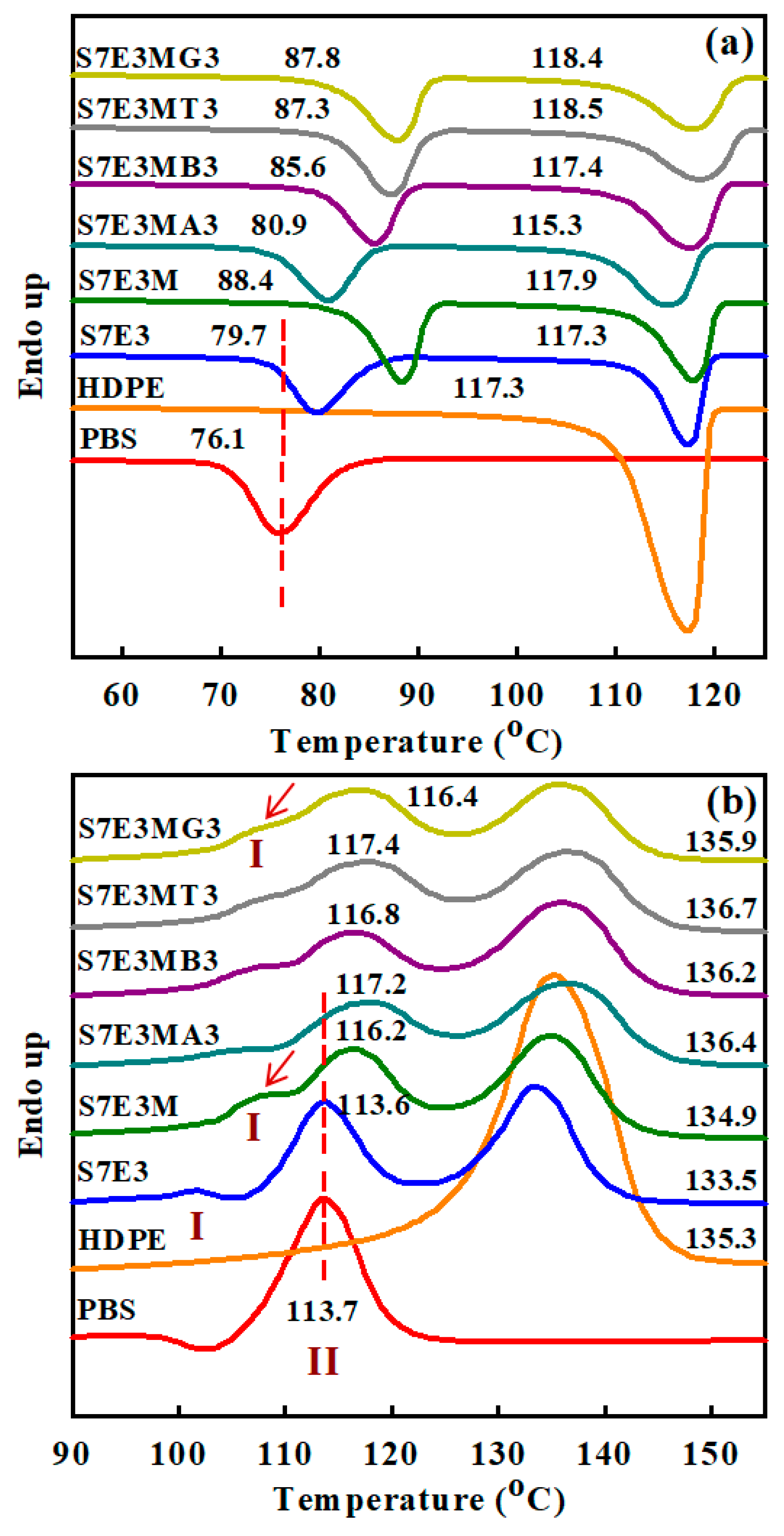

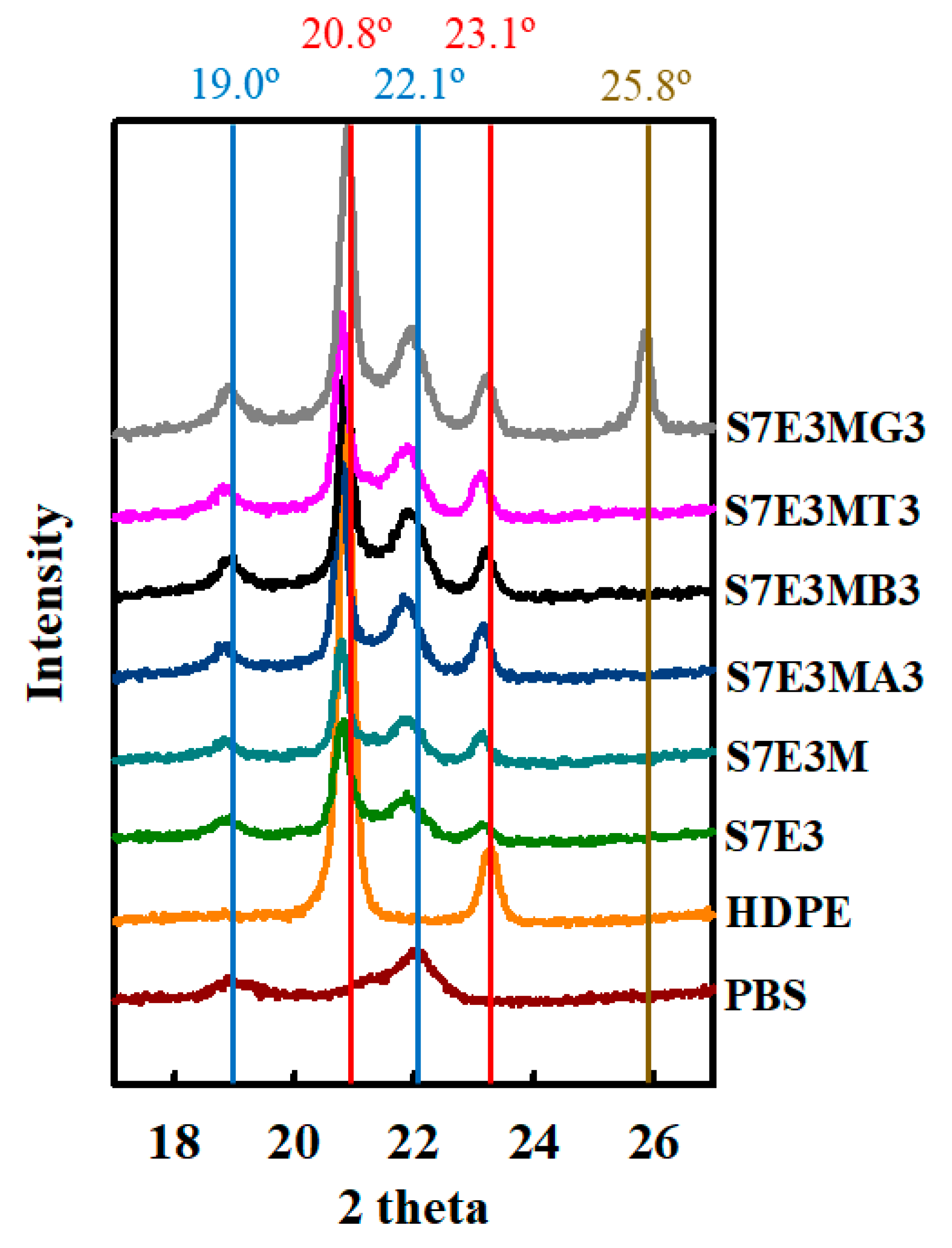

3.2. Crystallization and Melting Behavior

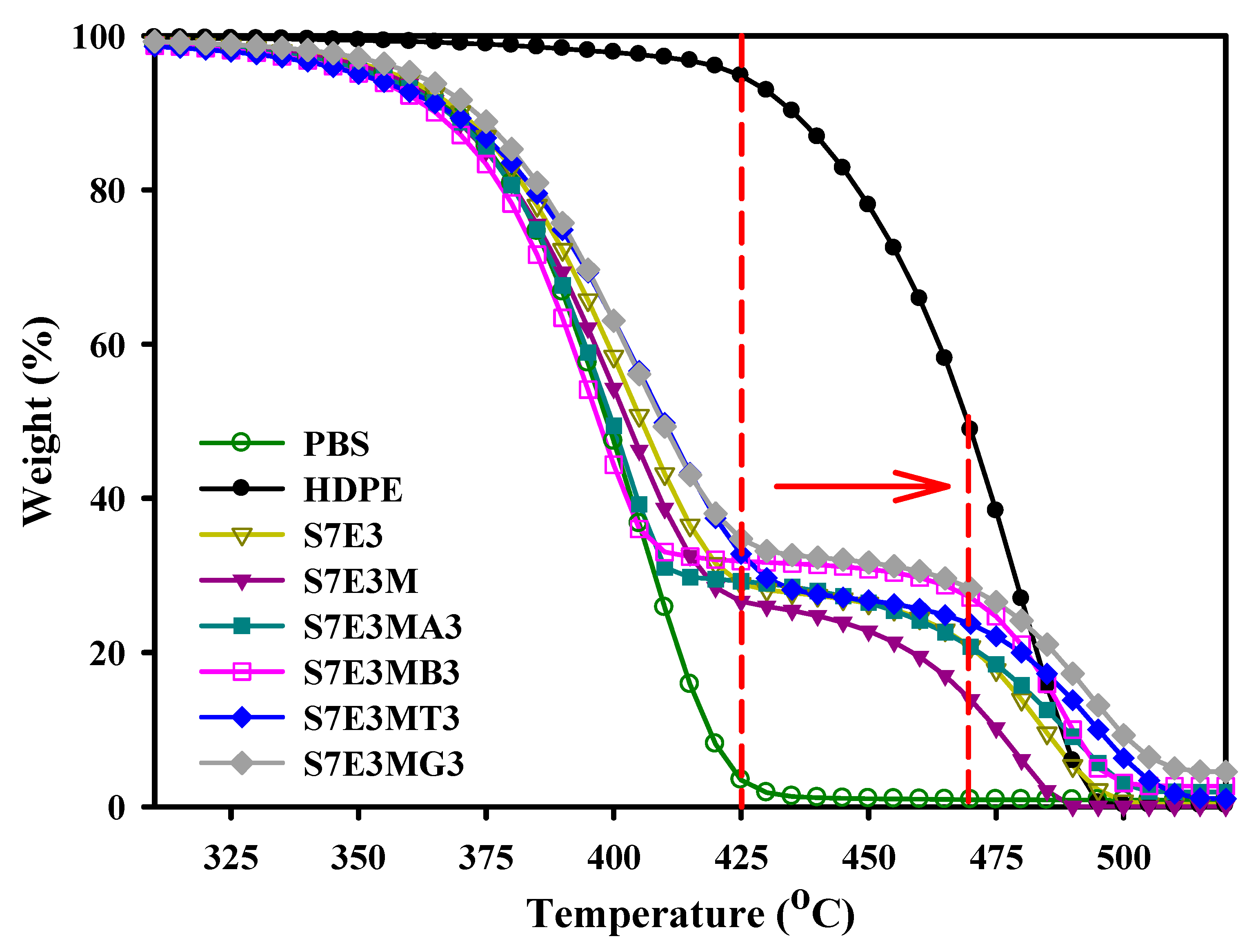

3.3. Thermal stability

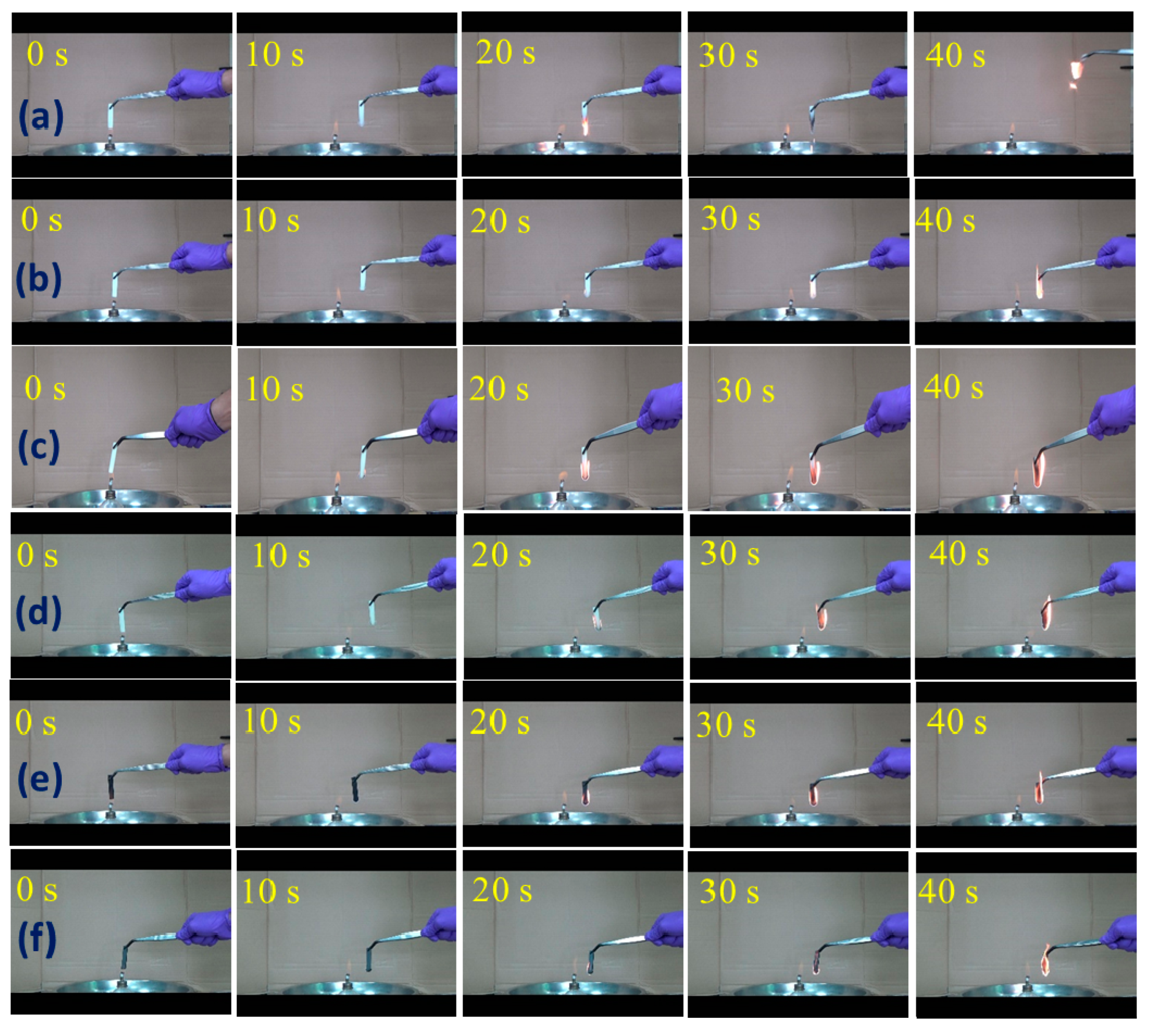

3.4. Anti-Dripping Performance

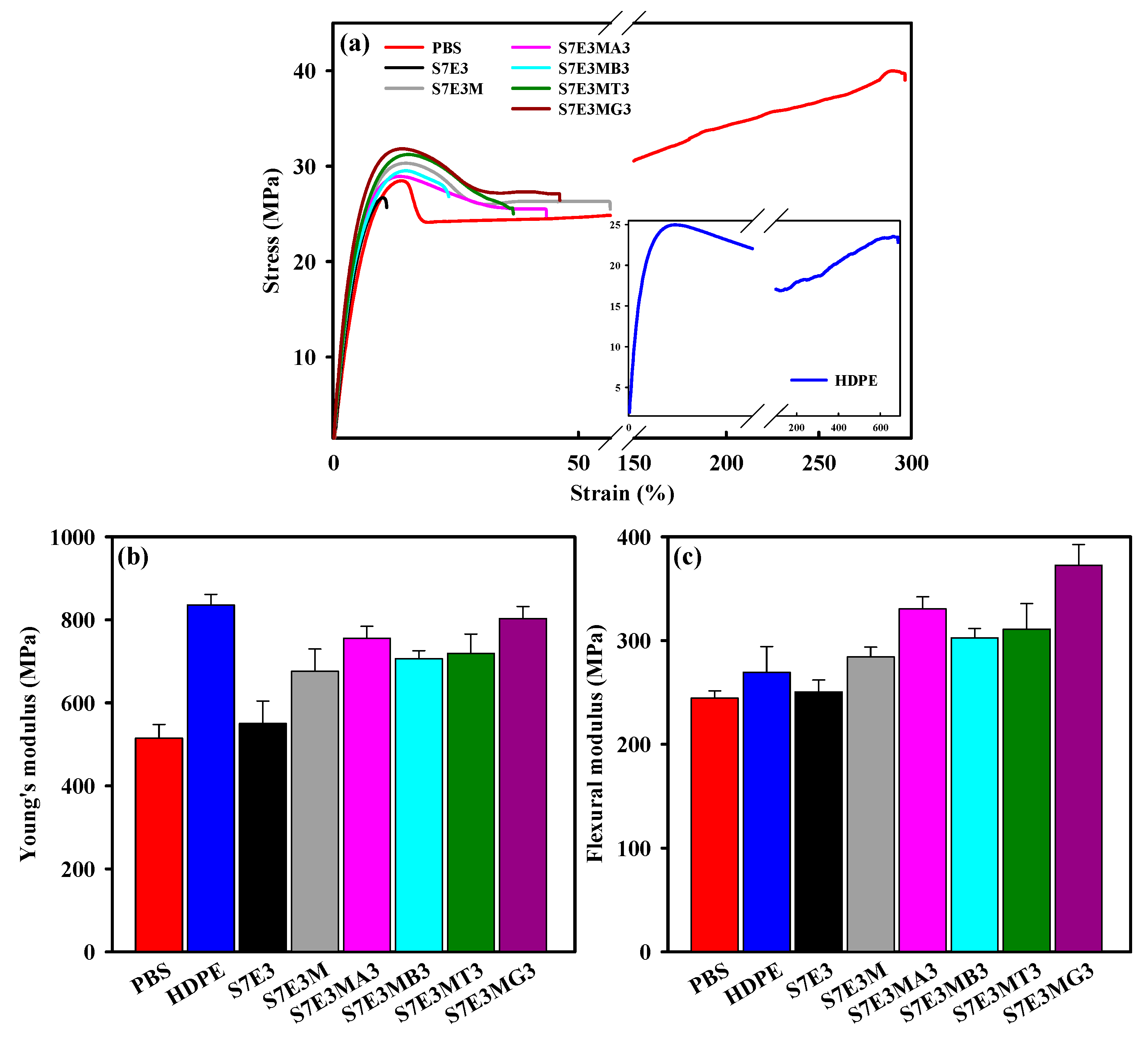

3.5. Mechanical Properties

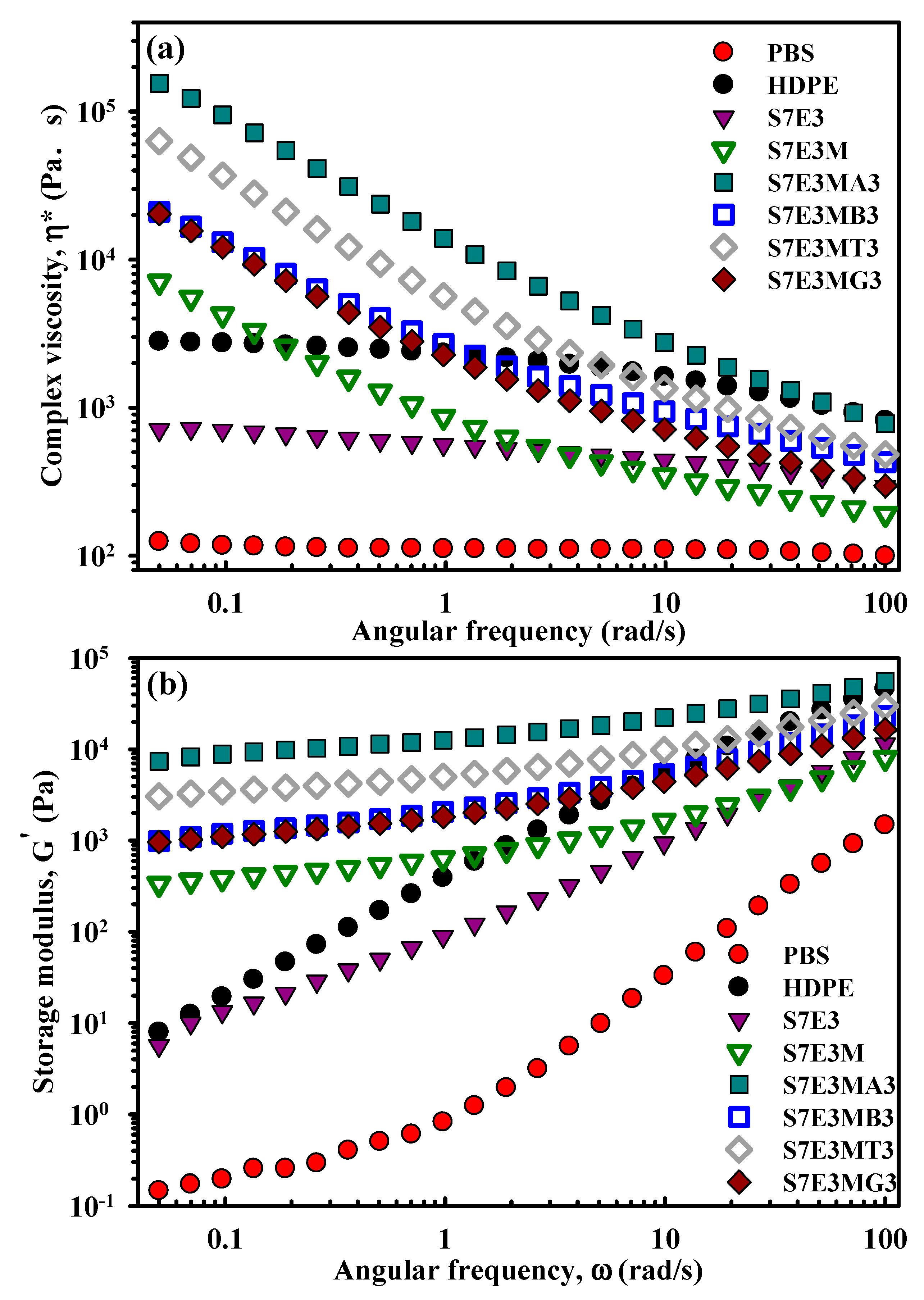

3.6. Melt Rheology

3.7. Electrical Resistivity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ray, S.S.; Bousmina, M. Biodegradable polymers and their layered silicate nanocomposites: In greening the 21st century materials world. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2005, 50, 962–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.M.; Behera, K.; Yadav, M.; Chiu, F.C. Polyamide 6/poly(vinylidene fluoride) blend-based nanocomposites with enhanced rigidity: Selective localization of carbon nanotube and organoclay. Polymers 2020, 12, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, K.; Chen, J.F.; Yang, J.M.; Chang, Y.H.; Chiu, F.C. Evident improvement in burning anti-dripping performance, ductility and electrical conductivity of PLA/PVDF/PMMA ternary blend-based nanocomposites with additions of carbon nanotubes and organoclay. Compos. B. Eng. 2023, 248, 110371–110382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, F.C.; Behera, K.; Cai, H.J.; Chang, Y.H. Polycarbonate/poly(vinylidene fluoride)-blend-based nanocomposites—Effect of adding different carbon nanofillers/organoclay. Polymers 2021, 13, 26261–26276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darshan, T.G.; Veluri, S.; Behera, K.; Chang, Y.H.; Chiu, F.C. Poly(butylene succinate)/high density polyethylene blend-based nanocomposites with enhanced physical properties—Selectively localized carbon nanotube in pseudo-double percolated structure. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 163, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, K.; Chang, Y.H.; Chiu, F.C. Manufacturing poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/high density polyethylene blend-based nanocomposites with enhanced burning anti-dripping and physical properties—Effects of carbon nanofillers addition. Compos. B Eng. 2021, 217, 108878–108889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.S.; Maiti, P.; Okamoto, M.; Yamada, K.; Ueda, K. New polylactide/layered silicate nanocomposites. 1. Preparation, characterization, and properties. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 3104–3110. [Google Scholar]

- Sivanjineyulu, V.; Chang, Y.H.; Chiu, F.C. Characterization of carbon nanotube- and organoclay-filled polypropylene/poly(butylene succinate) blend-based nanocomposites with enhanced rigidity and electrical conductivity. J. Polym. Res. 2017, 24, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquel, N.; Freyermouth, F.; Fenouillot, F.A.; Rousseau, J.P.; Pascault, P.; Loup, R.S. Synthesis and properties of poly(butylene succinate): Efficiency of different transesterification catalysts. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2011, 49, 5301–5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigli, M.; Fabbri, M.; Lotti, N.; Gamberini, R.; Rimini, B.; Munari, A. Poly(butylene succinate)-based polyesters for biomedical applications: A review. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 75, 431–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleija, M.; Platnieks, O.; Macutkevič, J.; Banys, J.; Starkova, O.; Grase, L.; Gaidukovs, S. Poly(butylene succinate) hybrid multi-walled carbon nanotube/iron oxide nanocomposites: Electromagnetic shielding and thermal properties. Polymers 2023, 15, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amornsakchai, T.; Duangsuwan, S.; Mougin, K.; Goh, K.L. Comparative study of flax and pineapple leaf fiber reinforced poly(butylene succinate): Effect of fiber content on mechanical properties. Polymers 2023, 15, 3691–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barletta, M.; Aversa, C.; Ayyoob, M.; Gisario, A.; Hamad, K.; Mehrpouya, M.; Vahabi, H. Poly(butylene succinate) (PBS): Materials, processing, and industrial applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 132, 101579–101641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aontee, A.; Sutapun, W. Effect of blend ratio on phase morphology and mechanical properties of high density polyethylene and poly(butylene succinate) blend. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 747, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Li, J.; Feng, J.; Yang, T.; Lin, X. Mechanical and thermal performance of distillers grains filled poly(butylene succinate) composites. Mater. Des. 2014, 57, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.B.; Xu, J.Z.; Xu, H.; Li, Z.M.; Zhong, G.J.; Lei, J. The crystallization behavior of biodegradable poly(butylene succinate) in the presence of organically modified clay with a wide range of loadings. Chinese J. Polym. Sci. 2015, 33, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Niu, B.; Zhang, L.Q.; Ji, X.; Xu, L.; Yan, Z.; Tang, J.H.; Zhong, G.J.; Li, Z.M. Confined crystallization of poly(butylene succinate) intercalated into organoclays: Role of surfactant polarity. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 68072–68080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Wu, D.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, W.; Lin, D. Rheological percolation behavior and isothermal crystallization of poly(butyene succinte)/carbon nanotube composites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 14186–14192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platnieks, O.; Gaidukovs, S.; Neibolts, N.; Barkane, A.; Gaidukova, G.; Thakur, V.K. Poly(butylene succinate) and graphene nanoplatelete based sustainable functional nanocomposite materials: Structure-properties relationship. Mater. Today Chem. 2020, 18, 100351–100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Chang, H.; Kang, C.; Sim, J. Analysis of mechanical properties and structural analysis according to the multi-layered structure of polyethylene-based self-reinforced composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 4055–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.U.R.; Jalil, A.; Sadiq, A.; Alzaid, M.; Naseem, M.S.; Alanazi, R.; Alanazi, S.; Alanzy, A.O.; Alsohaimi, I.H.; Malik, R.A. Effect of rice husk and wood flour on the structural, mechanical, and fire-retardant characteristics of recycled high-density polyethylene. Polymers 2023, 15, 4031–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Elkoun, S.; Ajji, A.; Huneault, M.A. Oriented structure and anisotropy properties of polymer blown films: HDPE, LLDPE and LDPE. Polymer 2004, 45, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandalise, R.N.; Zeni, M.; Martins, J.D.N.; Forte, M.M.C. Morphology, mechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of recycled high density polyethylene and poly(vinyl alcohol) blends. Polym. Bull. 2009, 62, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkova, L.; Filippi, S. Characterization of HDPE-g-MA/clay nanocomposites prepared by different preparation procedures: Effect of the filler dimension on crystallization, microhardness and flammability. Polym. Test. 2011, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aontee, A.; Sutapun, W. A study of compatibilization effect on physical properties of poly(butylene succinate) and high density polyethylene blend. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 699, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodjie, S.L.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Cai, W.W.; Li, C.Y.; Keating, M. Morphology and crystallization behavior of HDPE/CNT nanocomposite. J. Macromol. Sci. B Phys. 2006, 45, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarani, E.; Wurm, A.; Schick, C.; Bikiaris, D.N.; Chrissafis, K.; Vourlias, G. Effect of graphene nanoplatelets diameter on non-isothermal crystallization kinetics and melting behavior of high density polyethylene nanocomposites. Thermochim. Acta 2016, 643, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawiec, J.; Pawlak, A.; Slouf, M.; Galeski, A.; Piorkowska, E.; Krasnikowa, N. Preparation and properties of compatibilized LDPE/organo-modified montmorillonite nanocomposites. Eur. Polym. J. 2005, 41, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gcwabaza, T.; Ray, S.S.; Focke, W.W.; Maity, A. Morphology and properties of nanostructured materials based on polypropylene/poly(butylene succinate) blend and organoclay. Eur. Polym. J. 2009, 45, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.; Gupta, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Choi, H. Effect of clay on thermal, mechanical and gas barrier properties of biodegradable poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene succinate) (PLA/PBS) nanocomposites. Int. Polym. Process. 2010, 25, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojijo, V.; Sinha Ray, S.; Sadiku, R. Effect of nanoclay loading on the thermal and mechanical properties of biodegradable polylactide/poly[(butylene succinate)-co-adipate] blend composites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 2395–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Wu, C.; Peng, H.; Sun, Q.; Zhou, L.; Zhuang, J.; Cao, X.; Roy, V.A.L.; Li, R.K.Y. Effect of nitrogen-doped graphene on morphology and properties of immiscible poly(butylene succinate)/polylactide blends. Compos. B Eng. 2017, 113, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, F.C.; Yen, H.Z.; Chen, C.C. Phase morphology and physical properties of PP/HDPE/organoclay (nano) composites with and without a maleated EPDM as a compatibilizer. Polym. Test. 2010, 29, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample code | Composition | Parts (wt%) |

|---|---|---|

| PBS | PBS | 100 |

| HDPE | HDPE | 100 |

| S7E3 | PBS/HDPE | 70/30 |

| S7E3M | PBS/HDPE/PEgMA | 70/25/5 |

| S7E3MA3 | PBS/HDPE/PEgMA/15A | 70/25/5/3* |

| S7E3MB3 | PBS/HDPE/PEgMA/30B | 70/25/5/3* |

| S7E3MT3 | PBS/HDPE/PEgMA/CNT | 70/25/5/3* |

| S7E3MG3 | PBS/HDPE/PEgMA/GNP | 70/25/5/3* |

| Samples | Properties | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Td10 (°C) |

Td90 (°C) |

YM (MPa) (σ) | FM (MPa) (σ) | Log (Volume Resistivity) (Ω-cm) | |

| PBS | 369 | 419 | 515 ± 34 | 245 ± 7 | >14 |

| HDPE | 435 | 488 | 836 ± 25 | 269 ± 25 | >14 |

| S7E3 | 370 | 484 | 551 ± 54 | 251 ± 12 | >14 |

| S7E3M | 368 | 475 | 676 ± 54 | 284 ± 10 | >14 |

| S7E3MA3 | 368 | 489 | 756 ± 29 | 331 ± 12 | >14 |

| S7E3MB3 | 367 | 490 | 707 ± 19 | 303 ± 9 | >14 |

| S7E3MT3 | 368 | 495 | 719 ± 47 | 311 ± 25 | 7.5 ± 0.1 |

| S7E3MG3 | 373 | 499 | 803 ± 29 | 373 ± 20 | >14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).