Submitted:

16 October 2023

Posted:

18 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Material and methods

Animals and experimental design:

Induction of diabetes:

Grouping and drug intervention:

Blood collection and biochemical assessment:

Preparation of testicular tissue and samples

Assessment of testicular oxidative stress and inflammatory parameters

Assessment of sperm characteristics

Histopathological examination

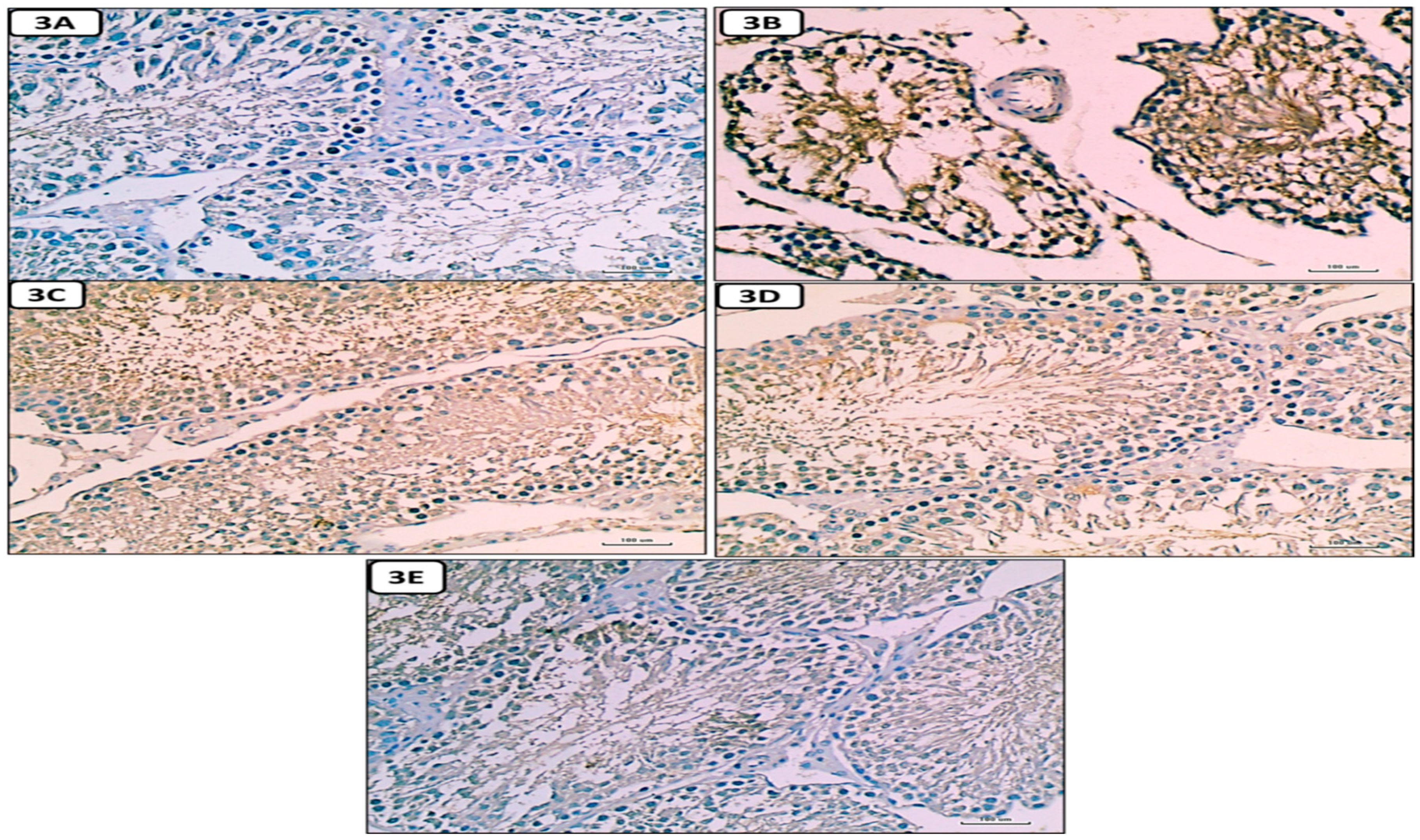

Immunohistochemical studies

Statistical analysis:

Results

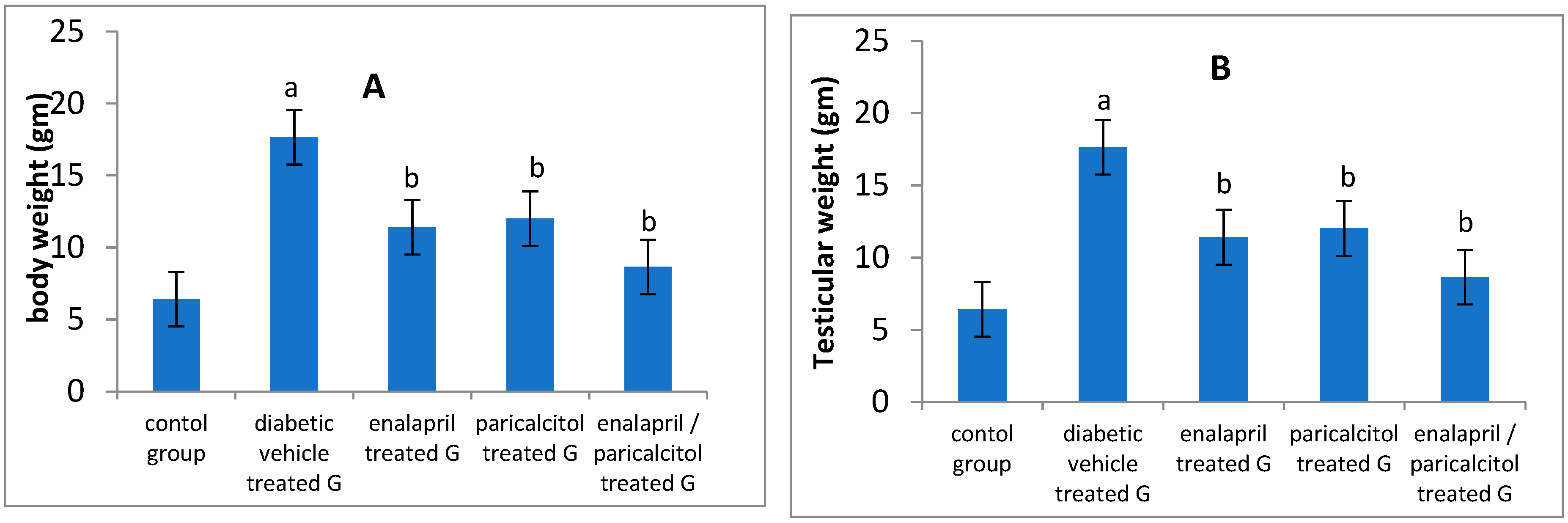

Effect of different treatments on body weight and testicular weight in studied groups:

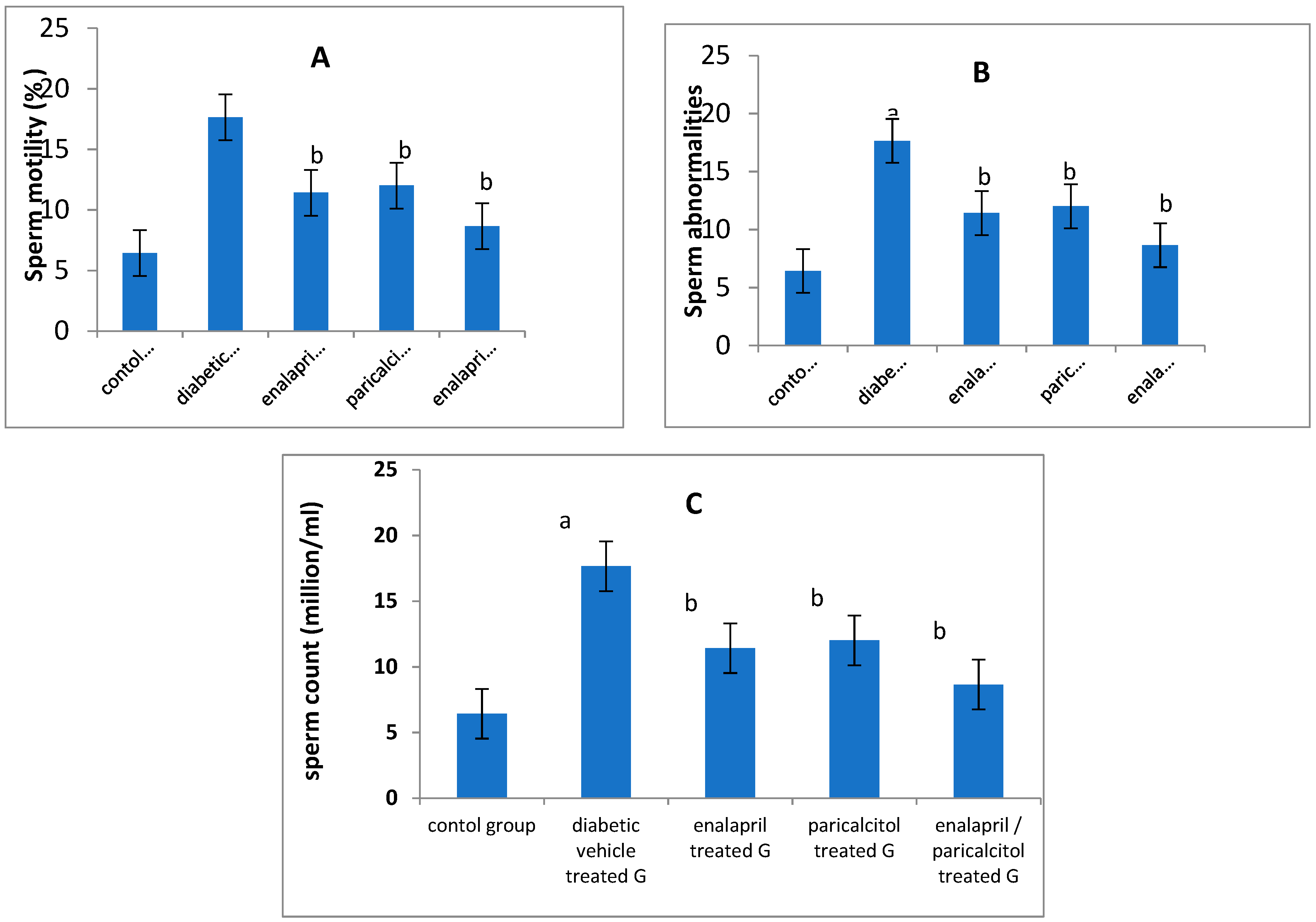

Impact of different treatments on sperm parameters in studied groups:

| Groups Parameters |

Non diabetic Controls | Diabetic groups | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle treated | Enalapril treated | Paricalcitol treated | Enalapril + Paricalcitol treated | |||

| Body weight (gm) | 230.2 ± 17.4 | 120.5 ± 15.4a | 170.3 ± 12.2b | 173.4 ± 14.4b | 205.7 ± 14.3b | < 0.05 |

| Testicular weight (gm) | 1.54 ± 0.02 | 0.78 ± 0.04 a | 1.15 ± 0.01b | 1.12 ± 0.05b | 1.43 ± 0.04b | < 0.05 |

| Sperm count (mill/ml) | 52.23 ± 6.5 | 25.2 ± 5.85a | 35.33 ± 3.21b | 36.11 ± 4.96b | 45.75 ± 5.22b | < 0.05 |

| Sperm motility (%) | 65.3 ± 5.32 | 35.4 ± 4.76a | 47.45 ± 5.11b | 48.32 ± 4.89b | 58.45 ± 6.39b | < 0.05 |

| Abnormal sperms (%) | 6.43 ± 0.97 | 17.6 ± 1.85a | 11.42 ± 0.89b | 12.01 ± 0.76b | 8.65 ± 0.56b | < 0.05 |

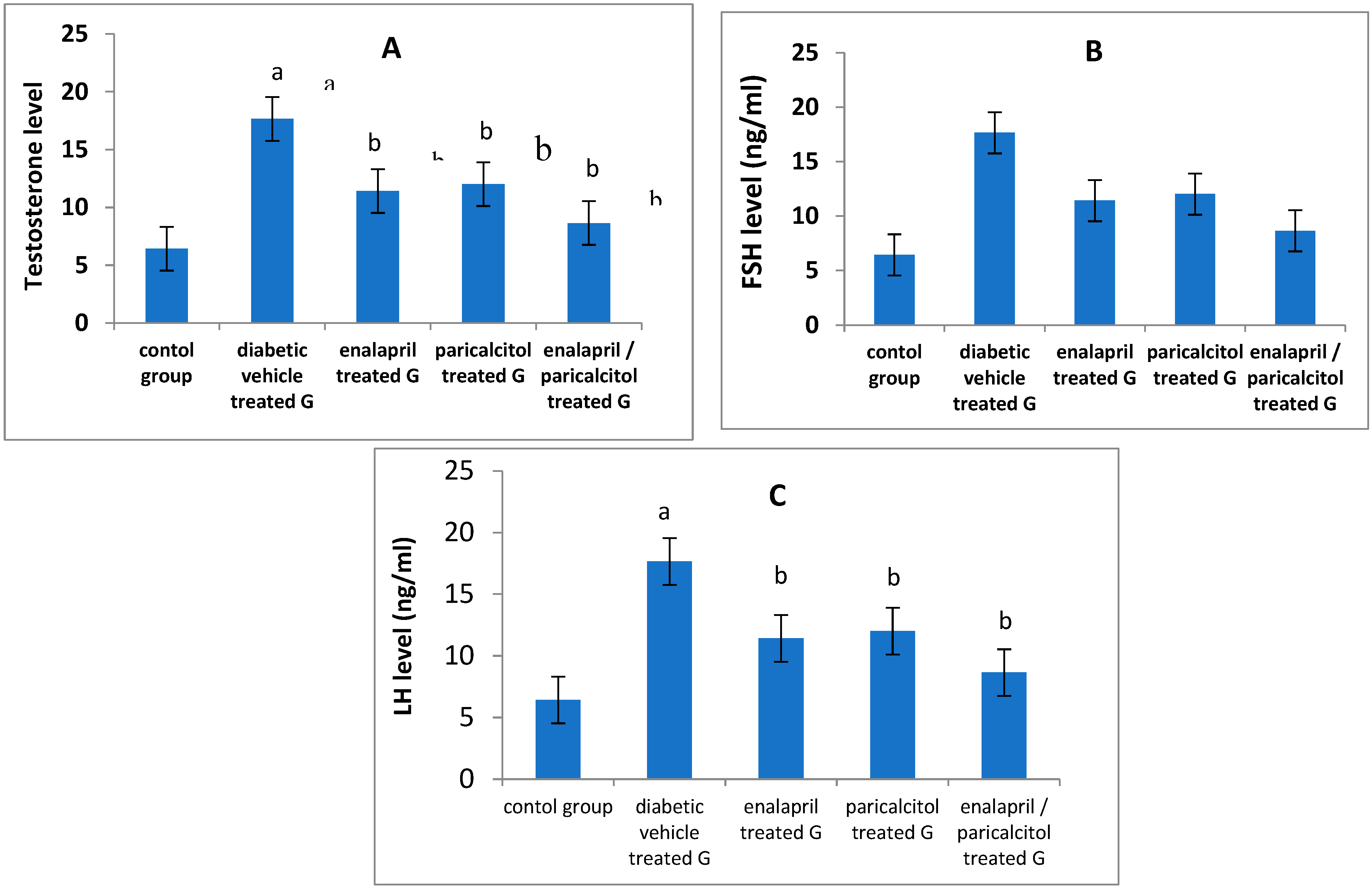

Impact of different treatments on testosterone, FSH and LH in studied groups:

| Groups Parameters |

Non-diabetic Controls | Diabetic groups | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle treated | Enalapril treated | Paricalcitol treated | Enalapril + Paricalcitol treated | |||

| Testosterone (ng/ml) | 4.71 ± 0.24 | 1.9 4 ± 0.13a | 3.55 ± 0.34b | 3.71 ± 0.11b | 4.4 ± 0.23b | < 0.05 |

| FSH (ng/ml) | 5.61 ± 0.98 | 2.75 ± 0.37a | 3.97 ± 0.57 b | 4. 02 ± 0.45b | 4.99 ± 0.31b | < 0.05 |

| LH (ng / ml) | 4.32 ± 0.45 | 1.97 ± 0.36a | 3.41 ± 0.54b | 3.56 ± 0.34b | 4.1 ± 0.65b | < 0.05 |

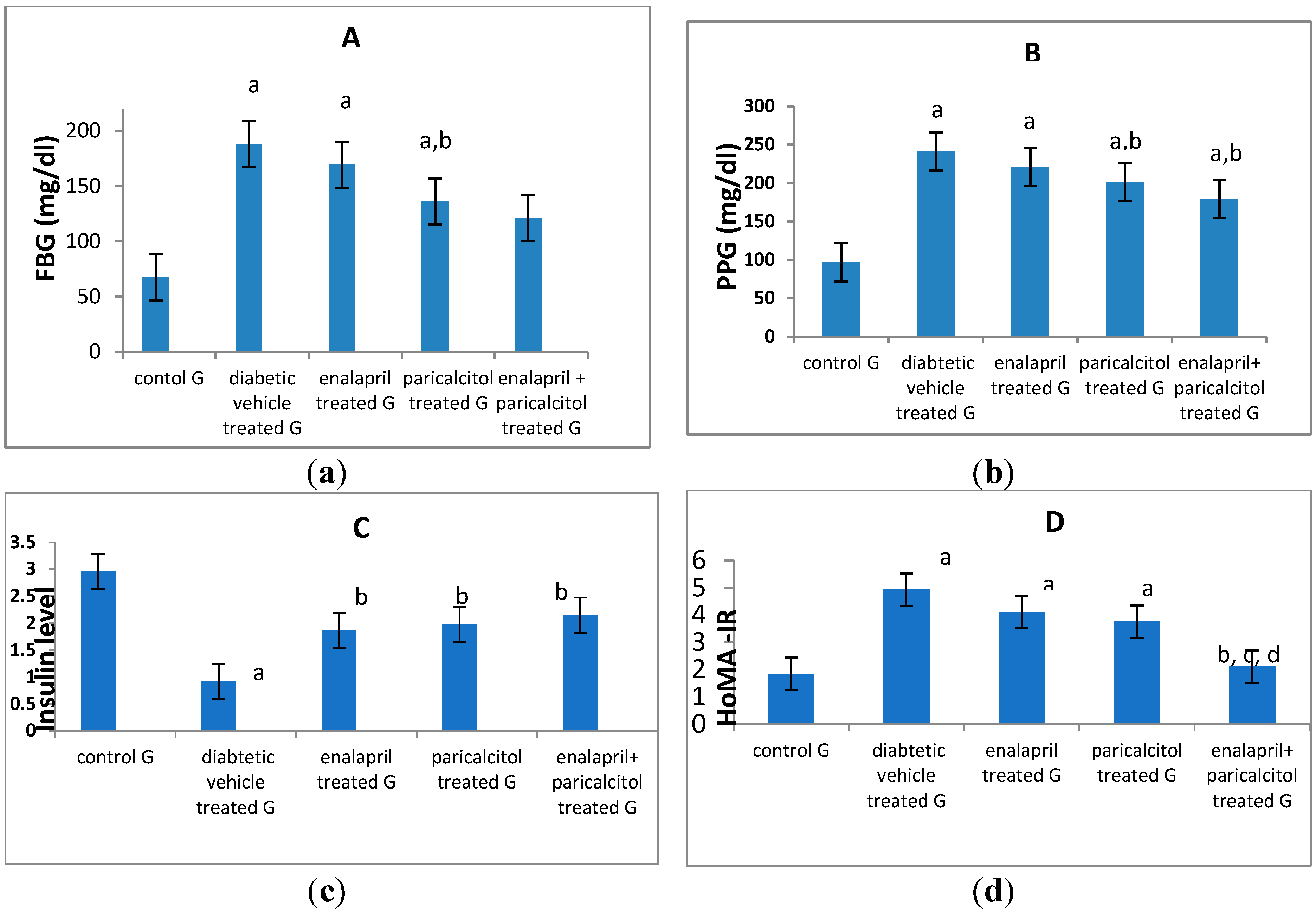

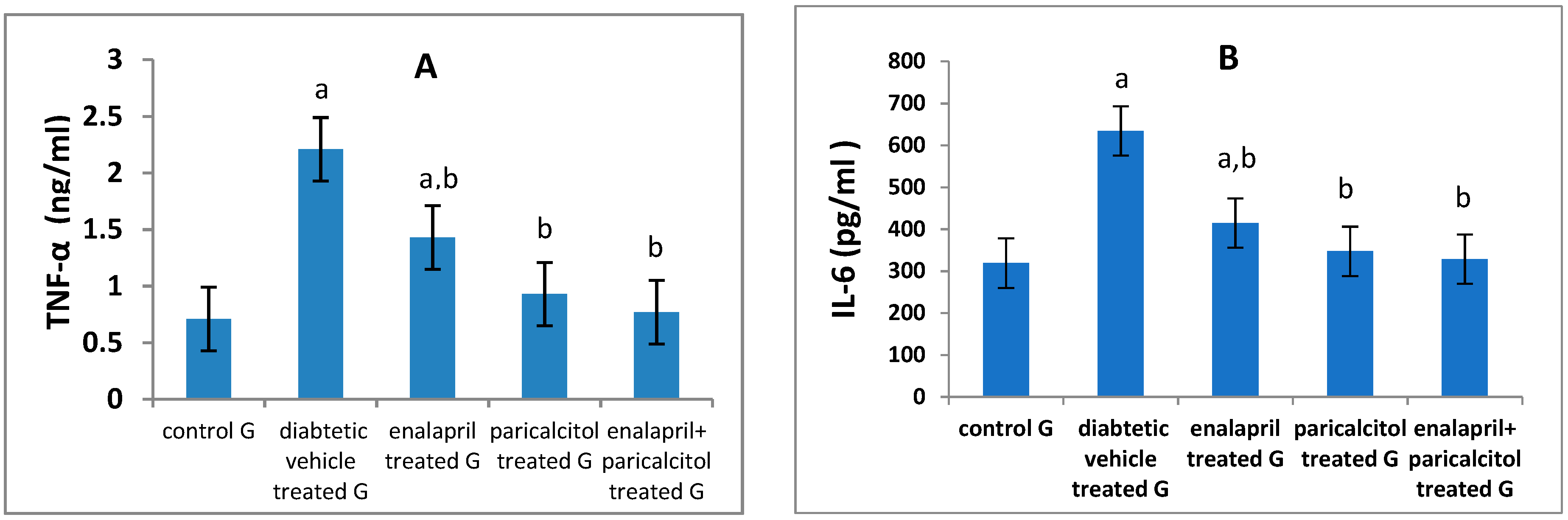

Effect of different treatments on glycemic status and inflammatory parameters:

| Groups Parameters |

Non-diabetic Controls | Diabetic groups | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle treated | Enalapril treated | Paricalcitol treated | Enalapril + Paricalcitol treated |

|||

| FBG (mg/dl) | 67.5 ± 11.3 | 188.02 ± 9.3a | 169.22 ± 4.71a | 136.19 ± 5.37a,b | 121.15 ± 3.54a,b | P < 0.01 |

| PPG (mg/dl) | 97.11 ± 14.3 | 241.26 ± 7.6a | 221.32 ± 4.51a | 201.31 ± 0.65a,b | 179.69 ± 4.14a,b,c | P < 0.01 |

| Insulin (ng/ml) | 2.96 ± 0.25 | 0.92 ± 0.58a | 1.86 ± 2.42b | 1.97 ± 3.04b | 2.148 ± 3.34b | P < 0.05 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.85 ± 0.16 | 4.93 ± 1.58a | 4.11 ± 1.45a | 3.76 ± 4.33a | 2.11 ± 1.51b,c,d | P < 0.05 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 319.1 ± 9.07 | 634.7 ± 24.5a | 414.9 ± 10.9a.b | 347.35 ± 31.2b | 328.5 ± 13.8b | P < 0.01 |

| TNF-α (ng/ml) | 0.71 ± 0.16 | 2.21 ± 0.03a | 1.43 ± 0.19a.b | 0.93 ± 0.19b | 0.77 ± 0. 9b | P < 0.01 |

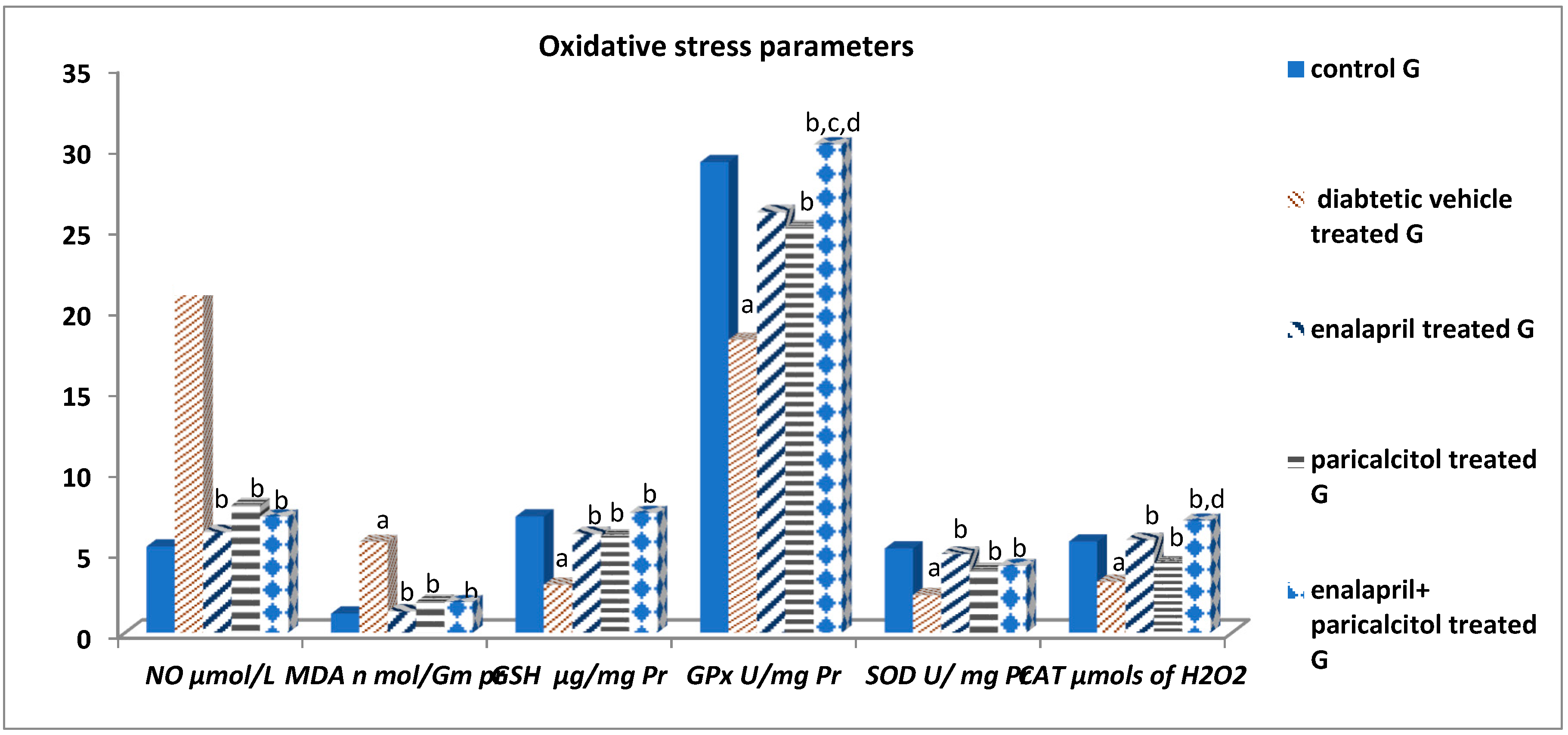

Impact of different treatments on testicular oxidative stress parameters:

| Groups Parameters |

Non-diabetic Controls | Diabetic groups | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle treated | Enalapril treated | Paricalcitol treated | Enalapril + Paricalcitol treated |

|||

| NO (μmols/L) | 5.33 ± 1.13 | 21.24 ± 4.6a | 6.23 ± 1.11b | 7.89 ± 2.32b | 7.19 ± 1.44b | P < 0.001 |

| MDA (nmol/mg pr) | 1.18 ± 0.13 | 5.61 ± .34a | 1.32 ± 0.41b | 1.91 ± 0.15b | 1.89 ± 0.11b | P < 0.001 |

| GSH (μg/mg pr) | 7.19 ± 1.05 | 2.97 ± 0.88a | 6.11 ± 0.72b | 5.93 ± 1.08b | 7.41 ± 1.54b | P < 0.01 |

| GPx (U/mg pr) | 29.12 ± 2.82 | 18.12 ± 2.02a | 26.03 ± 3.08b | 25.06 ± 2.03b | 30.22 ± 2.08b,c,d | P < 0.01 |

| SOD (units/mg pr) | 5.21 ± 0.43 | 2.33 ± 1.55a | 4.88 ± 1.39b | 3.85 ± 1.13b | 4.13 ± 1.48b | P < 0.01 |

| CAT (μmols of H2O2) | 5.64 ± 1.56 | 3.15 ± 0.96a | 5.73 ± 1.07b | 4.31 ± 1.16b | 6.93 ± 1.35b,d | P < 0.01 |

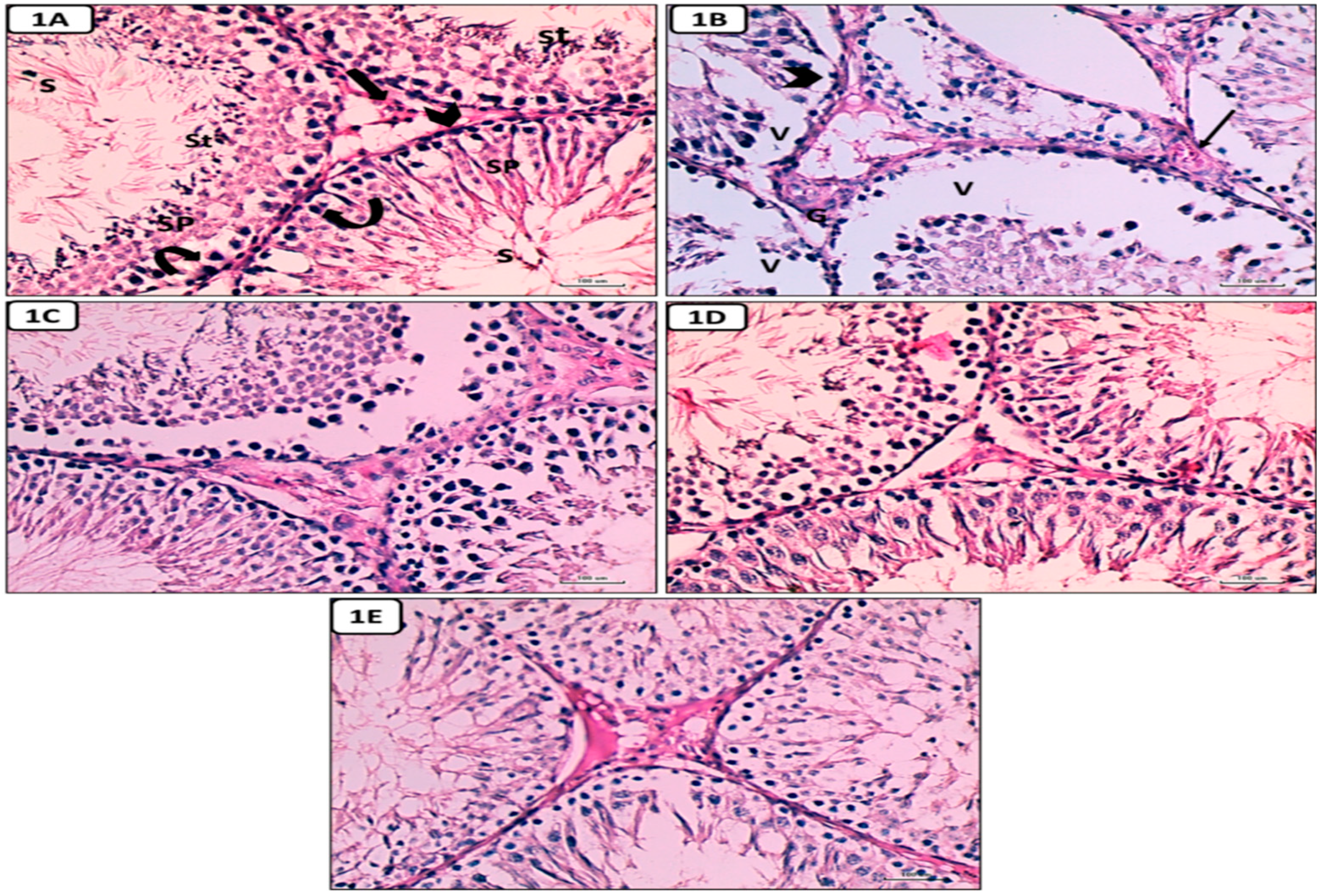

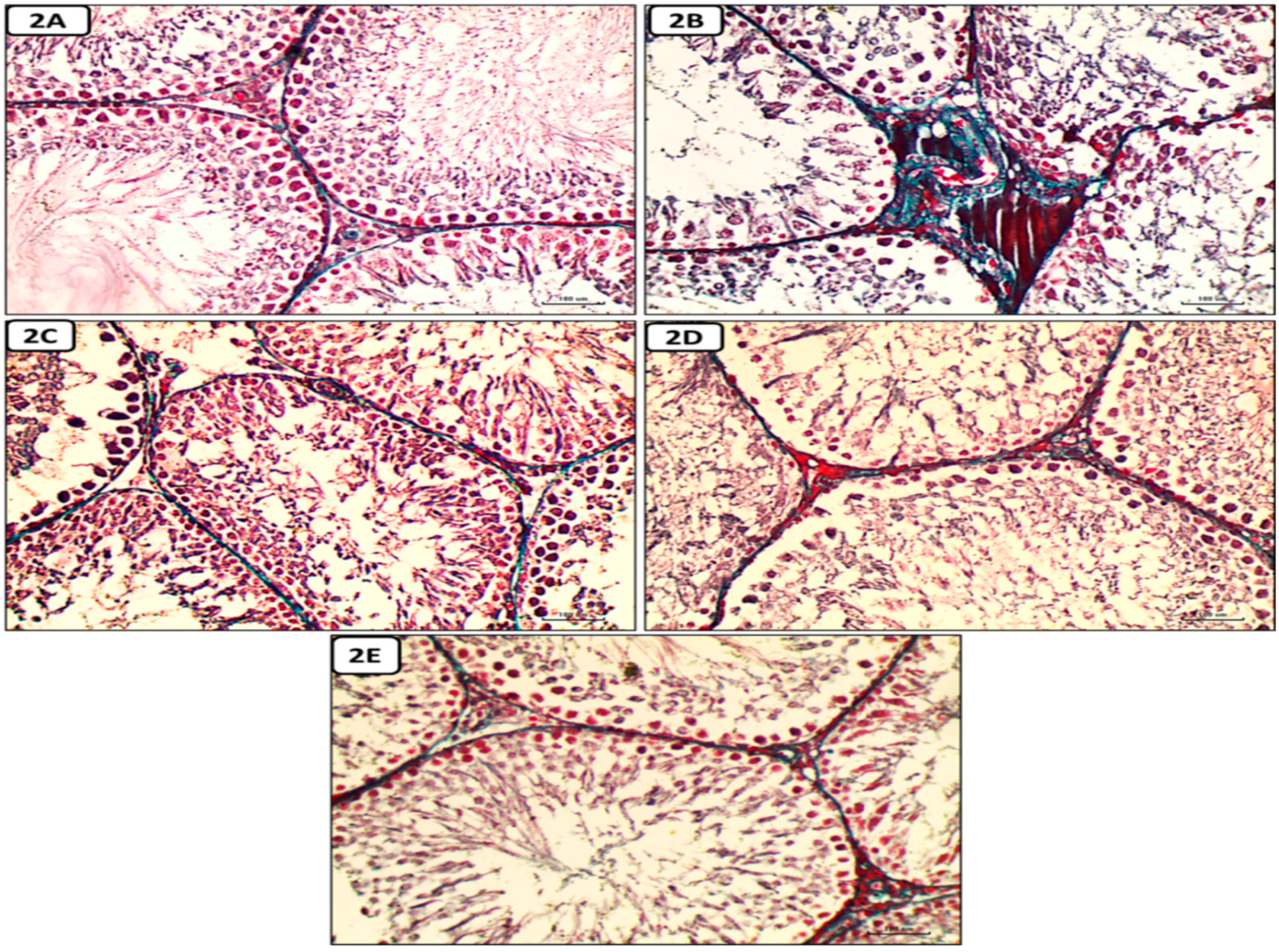

Histological and Immunohistochemical results

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections results

Discussion

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saeedi,P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019,157,107843. Doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843. [CrossRef]

- Aksu, I.; Baykara,B.; Kiray, M.; Gurpinar, T.; Sisman, A.R.; Ekerbicer, N., Tas, A.; Gokdemir-Yazar, O.; Uysal, N. Serum IGF-1 levels correlate negatively to liver damage in diabetic rats. Biotech Histochem. 2013, 88(3-4),194-201. doi: 10.3109/10520295.2012.758311. [CrossRef]

- Shrilatha, B.; Muralidhara. Occurrence of oxidative impairments, response of antioxidant defences and associated biochemical perturbations in male reproductive milieu in the Streptozotocin-diabetic rat. Int J Androl. 2007, 30(6), 508-518. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007. 00748.x. [CrossRef]

- Maresch, C.C.; Stute, D.C.; Ludlow, Hammes, H.P.; de Kretser, D.M.; Hedger, M.P.; Linn, T. Hyperglycemia is associated with reduced testicular function and Activin dysregulation in the Ins2 Akita+/− mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017,446, 91–101.

- Tiwari, A. K. Imbalance in antioxidant defense and human diseases: multiple approach of natural antioxidants therapy. Current Science, 200, 81, 1179–1187.

- Ali, T.M.; Mehanna, O.M.; Elsaid, A.G.; Askary, A.E. Effect of Combination of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Vitamin D Receptor Activators on Cardiac Oxidative Stress in Diabetic Rats. Am J Med Sci. 2016; 352(2), 208-214. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.04.016. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.M.; Ali, T.M.; Abdel Gaid, M.; Elberry, A.A. Effects of enalapril and paricalcitol treatment on diabetic nephropathy and renal expressions of TNF-α, p53, caspase-3 and Bcl-2 in STZ-induced diabetic rats. PLoS One. 2019,14(9), e0214349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214349. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, S.; Kurz, S.; Münzel, T.; et al. Angiotensin II-mediated hypertension in the rat increases vascular superoxide production via membrane NADH/NADPH oxidase activation. Contribution to alterations of vasomotor tone. J Clin Invest. 1996,97(8),1916-1923. doi:10.1172/JCI118623. [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, B.J.; Mugesh, G. Synthesis, characterization and antioxidant activity of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Org Biomol Chem. 2011,9(5),1356-1365. doi:10.1039/c0ob00823k. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, Z.; Hekmatdoost, A.; & Nourian, M. Antioxidant efficacy of vitamin D. Journal of Parathyroid Disease, 2016; 5(1), 11-16.

- Wang, T.J.; Pencina, M.J.; Booth, S.L.; Jacques, P.F.; Ingelsson, E.; Lanier, K.; et al. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008,117,503-11. [CrossRef]

- Ravani, P.; Malberti, F.; Tripepi, G.; Pecchini. P.; Cutrupi, S.; Pizzini, P.; et al. Vitamin D levels and patient outcome in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2009,75,88-95. [CrossRef]

- Mitri, J.; Muraru, M.; Pittas, A. Vitamin D and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011, 65,1005-15. [CrossRef]

- Hyppönen, E.; Läärä, E.; Reunanen, A.; Järvelin, M.R.; Virtanen, S.M. Intake of vitamin D and risk of type 1 diabetes: a birthcohort study. Lancet. 2001, 358,1500-3. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; XU, J.; & Zhang, H. Effect of Vitamin D on ACE2 and Vitamin D receptor expression in rats with LPS-induced acute lung injury. Chinese journal of emergency medicine, 2016,1284-1289.

- Long, L.; Qiu, H.; Cai, B.; Chen, N.; Lu, X.; Zheng, S.; Ye, X.; Li, Y. Hyperglycemia induced testicular damage in type 2 diabetes mellitus rats exhibiting microcirculation impairments associated with vascular endothelial growth factor decreased via PI3K/Akt pathway. Oncotarget, 2018,9 (4), 5321–5336. [CrossRef]

- Shrilatha, B.; Muralidhara. Early oxidative stress in testis and epididymal sperm in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice: Its progression and genotoxic consequences. Reprod. Toxicol.2007, 23, 578-587. [CrossRef]

- Finch, J.L.; Suarez, E.B.; Husain, K.; et al. Effect of combining an ACE inhibitor and a VDR activator on glomerulosclerosis, proteinuria, and renal oxidative stress in uremic rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2012, 302(1), F141–9. [CrossRef]

- Tietz, N.W. Clinical Guide to Laboratory Tests, 3rd Ed., Pbl, W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 1995, Pp:509–580.

- Temple, R.C.; Clark, P.M, and Hales, C.N. Measurement of insulin secretion in type 2 diabetes: problems and pitfalls. Diabetic Medicine. 1992, 9, 503-512. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia1985, 28, 412–9.

- Huang, H.F.; Linsenmeyer, T.A.; Li M.T.; Giglio, W.; Anesetti, R.; von Hagen, J.; Ottenweller, J.E.; Pogach, L. Acute effects of spinal cord injury on the pituitary-testicular hormone axis and Sertoli cell functions: a time course study. J. Androl. 1995, 16, 148–157. [CrossRef]

- Ellman, M. A spectrophotometric method for determination of reduced glutathione in tissues. Anal Biochem.1959, 74(1), 214–226.

- Flohe, L.; Otting, F. Superoxide dismutase assays. Methods Enzymol. 1984,105, 93–104. [CrossRef]

- Husain, K.; Suarez, E.; Isidro, A.; Ferder, L. Effects of paricalcitol and enalapril on atherosclerotic injury in mouse aortas. Am J Nephrol. 2010, 32(4), 296-304. [CrossRef]

- Aebi H. (1984): Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymology,105:121-6. [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbaturic acid reaction. Anal.Biochem. 1982, 95, 351-358. [CrossRef]

- Hortelano, S.; Dewez, B.; Genaro, A.M.; Díaz-Guerra, M.J.; Boscá, L. Nitric oxide is released in regenerating liver after partial hepatectomy. Hepatology. 1995,21, 776-786. [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.; Jena, GB. Effects of nicotine on the testicular toxicity of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat: intervention of enalapril. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2014, 33, 609-622. doi:10.1177/0960327113491509. [CrossRef]

- Khaki, A.; Khaki, A.A.; Hajhosseini, L.; Golzar, F.S.; Ainehchi, N. The anti-oxidant effects of ginger and cinnamon on spermatogenesis dys-function of diabetes rats. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2014,11,1-8. doi:10.4314/ajtcam. v11i4.1. [CrossRef]

- Shalizar, J.A.; Hasanzadeh, S.; Malekinejad, H. Chemoprotective effect of Crataegusmonogyna aqueous extract against cyclophosphamide-induced reproductive toxicity. Vet Res Forum. 2011, 2, 266–273.

- Bancroft, J.D.; Layton C. The Hematoxylin and Eosin. In: SuVarna, S.K.; Layton, C.; Bancroft, J.D.; Eds., Theory & Practice of histological Technique, 7th Edition, Churchill Livingstone of ElSevier, Philadelphia, Ch.10 and 11, 2013,172-214.

- Jackson, P.; Blythe, D. Immunohistochemical Techniques. In: SuVarna, S.K.; Layton, C.; Bancroft, J.D.; Eds., Theory & Practice of histological techniques, 7th Edition, Churchill Livingstone of El Sevier, Philadelphia. Ch. 18, 2013, 381-434.

- Ricci, G.; Catizone, A.; Esposito, R.; Pisanti, F.A.; Vietri, M.T.; Galdieri, M. Diabetic rat testes: morphological and functional alterations. Andrologia. 2009, 41, 361-368. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0272.2009. 00937.x. [CrossRef]

- Take, G.; Ilgaz, C.; Erdogan, D.; Ozogul, C.; Elmas, C. A Comparative Study of the Ultrastructure of Submandibular, Parotid and Exocrine Pancreas in Diabetes and Fasting. Saudi Medical Journal. 2007, 28, 28-35.

- Long, L.; Wang, J.; Lu, X.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, S.; Luo, C.; Li, Y. Protective effects of scutellarin on type II diabetes mellitus-induced testicular damages related to reactive oxygen species/Bcl-2/Bax and reactive oxygen species/microcirculation/staving pathway in diabetic rat. J Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 252530. doi:10.1155/2015/252530. [CrossRef]

- Schoeller, E.L.; Albanna, G.; Frolova, A.I.; Moley, K.H. Insulin rescues impaired spermatogenesis via the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in Akita diabetic mice and restores male fertility. Diabetes. 2011, 61(7):1869-1878. doi:10.2337/db11-1527. [CrossRef]

- Ozdemır, O.; Akalın, P.P.; Baspınar, N.; Hatıpoglu, F. Pathological changes in the acute phase of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats.Bull Vet Inst Pulawy. 2009,53, 783-790.

- Husain, K.; Suarez, E.; Isidro, A.; Hernandez, W.; Ferder, L. Effect of paricalcitol and enalapril on renal inflammation/oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. World J Biol Chem. 2015, 6, 240-248. doi:10.4331/wjbc. v6.i3.240. [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.M.; Esawy, B.H.; Elmorsy, E.A. Effect of combining an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a vitamin D receptor activator on renal oxidative and nitrosative stress in diabetic rats. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol 2015, 5(3), 222–31. [CrossRef]

- Husain, K.; Ferder, L.; Mizobuchi, M.; Finch, J.; Slatopolsky, E. Combination Therapy with Paricalcitol and Enalapril Ameliorates Cardiac Oxidative Injury in Uremic Rats. Am J Nephrol 2009,29:465-472. doi: 10.1159/000178251. [CrossRef]

- Ritter, C.; Zhang, S.; Finch, J. L.; Liapis.; Suarez, E.; Ferder, L.; Delmez, J.; Slatopolsky, E. Cardiac and Renal Effects of Atrasentan in Combination with Enalapril and Paricalcitol in Uremic Rats. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2014,39, 340-352. doi: 10.1159/000355811. [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.J.; Cavia, M.; Muniz, P.; De Francisco, A.L.; Arias, M.; Santos, J.; et al. Paricalcitol reduced oxidative stress and inflammation in hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol 2012; 13: 159. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-13-159 PMID: 23186077. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.F.; Milena, F.J.; Mora, C. Leo, C.; Claverie, F.; Flores, C.; Garcia, J. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene expression in diabetic nephropathy: relationship with urinary albumin excretion and effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005, (99, :S98-S102. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005. 09918.x. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.A.; Fearnley, G.W.; Harrison, M.A.; Tomlinson, D.C.; Wheatcroft, S.B.; Ponnambalam, S. Vascular endothelial growth factors: multitasking functionality in metabolism, health and disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015, 38(4), 753-763. doi:10.1007/s10545-015-9838-4. [CrossRef]

- Pérez Díaz, J.; Benitez, A.; Fernández Galaz, C. Effect of streptozotocin diabetes on the pituitary-testicular axis in the rat. Horm Metab Res. 1982, 14(9), 479-482. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1019052. [CrossRef]

- Salvi, R.; Castillo, E.; Voirol, M.J.; Glauser, M.; Rey, J.; Gaillard, R.C.; Vollenweider, P.; Pralong F.P. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone-expressing neurons immortalized conditionally are activated by insulin: implication of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Endocrinology. 2006, 147, 816-826. doi:10.1210/en.2005-0728. [CrossRef]

- Olivares, A.; Méndez, J.P.; Cárdenas, M.; Oviedo, N.; Palomino, M. Á.; Santos, I.; Ulloa-Aguirre, A.. Pituitary-testicular axis function, biological to immunological ratio and charge isoform distribution of pituitary LH in male rats with experimental diabetes. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009, 161(3), 304-312. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.12.021. [CrossRef]

- Shoorei, H.; Khaki, A.; Khaki, A.A.; Hemmati, A.A.; Moghimian, M.; Shokoohi, M. The ameliorative effect of carvacrol on oxidative stress and germ cell apoptosis in testicular tissue of adult diabetic rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 568-578. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.054. [CrossRef]

- Soltani, M.; Moghimian, M.; Abtahi-Eivari, S.H.; Shoorei, H.; Khaki, A.; Shokoohi, M. Protective Effects of Matricaria chamomilla Extract on Torsion/ Detorsion-Induced Tissue Damage and Oxidative Stress in Adult Rat Testis. Int J Fertil Steril. 2018, 12(3), 242-248. doi:10.22074/ijfs.2018.5324. [CrossRef]

- Nna, V.U.; Bakar, A.B.A.; Ahmad, A.; Mohamed, M. Down-regulation of steroidogenesis-related genes and its accompanying fertility decline in streptozotocin-induced diabetic male rats: ameliorative effect of metformin. Andrology. 2019, 7(1), 110-123. doi:10.1111/andr.12567. [CrossRef]

- Alahmar, A.T. Role of Oxidative Stress in Male Infertility: An Updated Review. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2019, 12, 4-18. doi:10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_150_18. [CrossRef]

- Laleethambika, N.; Anila, V.; Manojkumar, C.; Muruganandam, I.; Giridharan B.; Ravimanickam, T.; Balachandar, V. Diabetes and Sperm DNA Damage: Efficacy of Antioxidants. SN Compr. Clin. Med.2019, 1, 49–59.

- Alasmari, W. A.; Faruk, E. M.; Abourehab, M. A.; Elshazly, A. M. E.; & El Sawy, N. A. The effect of metformin versus vitamin E on the testis of adult diabetic albino rats: histological, biochemical and immunohistochemistry study. Advances in Reproductive Sciences, 2018, 6(4), 113-132.

- Samir, S.M.; Elalfy, M.; Nashar, E.M.E.; Alghamdi, M.A.; Hamza, E.; Serria, M.S.; Elhadidy, M.G. Cardamonin exerts a protective effect against autophagy and apoptosis in the testicles of diabetic male rats through the expression of Nrf2 via p62-mediated Keap-1 degradation. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2021, 25(4), 341-354. doi:10.4196/kjpp.2021.25.4.341. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, Q.; Guo, F.; Huang, F.; Ji, L.; An, T.; Qin, G. Vitamin D3 supplementation improves testicular function in diabetic rats through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ/transforming growth factor-beta 1/nuclear factor-kappa B. J Diabetes Investig. 2019, 10(2), 261-271. doi:10.1111/jdi.12886. [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Wang, Q.; Hao, Y.; Ma, X.; Wu, L., Li, W.; Du, M.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Guo, F.; Ma, S.; Huang, F.; Qin, G. Vitamin D supplement improved testicular functions in diabetic rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016, 473, 161-167. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.03.072. [CrossRef]

- Borg, H. M.; Kabel, A.; Estfanous, R.; & Abd Elmaaboud, M. Effect of the combination between empagliflozin and calcipotriol on cadmium-induced testicular toxicity in rats. Bulletin of Egyptian Society for Physiological Sciences. 2020,40(1), 15-31. DOI:10.21608/BESPS.2019.14918.1029. [CrossRef]

- Sood, S.; Reghunandanan, R.; Reghunandanan, V.; Marya, R.K.; Singh, P.I. Effect of vitamin D repletion on testicular function in vitamin D-deficient rats. Ann Nutr Metab. 199, 39, 95-98. doi:10.1159/000177848. [CrossRef]

- ABOZAID, E. R.; & HANY, A. Vitamin D3 nanoemulsion ameliorates testicular dysfunction in high-fat diet-induced obese rat model. The Medical Journal of Cairo University, 2020, 88, 775-785. DOI: 10.21608/mjcu.2020.104886. [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.; Jena, G.B. Enalapril reduces germ cell toxicity in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat: investigation on possible mechanisms. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2012, 385(2), 111-124. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0707-x. [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.; Jena, G.B. Effects of nicotine on the testicular toxicity of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat: intervention of enalapril. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2014, 33(6), 609-622. doi:10.1177/0960327113491509. [CrossRef]

- Bechara G.R., deSouza D.B., Simeos M., Felix-Particio B., Medeiros Jr. J.L., Costa W.S., Sampaio F.J.B. Testicular Morphology and Spermatozoid Parameters in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats Treated with Enalapril. J Urol. 2015, 194(5), 1498-1503. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2015.06.073. [CrossRef]

- Gokce, G.; Karboga, H.; Yildiz, E.; Ayan, S.; Gultekin, Y. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade on apoptotic changes in contralateral testis following unilateral testicular torsion. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008, 40(4), 989-995. doi:10.1007/s11255-008-9348-5. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).