Submitted:

14 October 2023

Posted:

17 October 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Objective

Language

Methods

Identification of Relevant Studies

Study Selection

Data Charting

Collating, Summarising, and Reporting Results

Trustworthiness and Rigour

Results

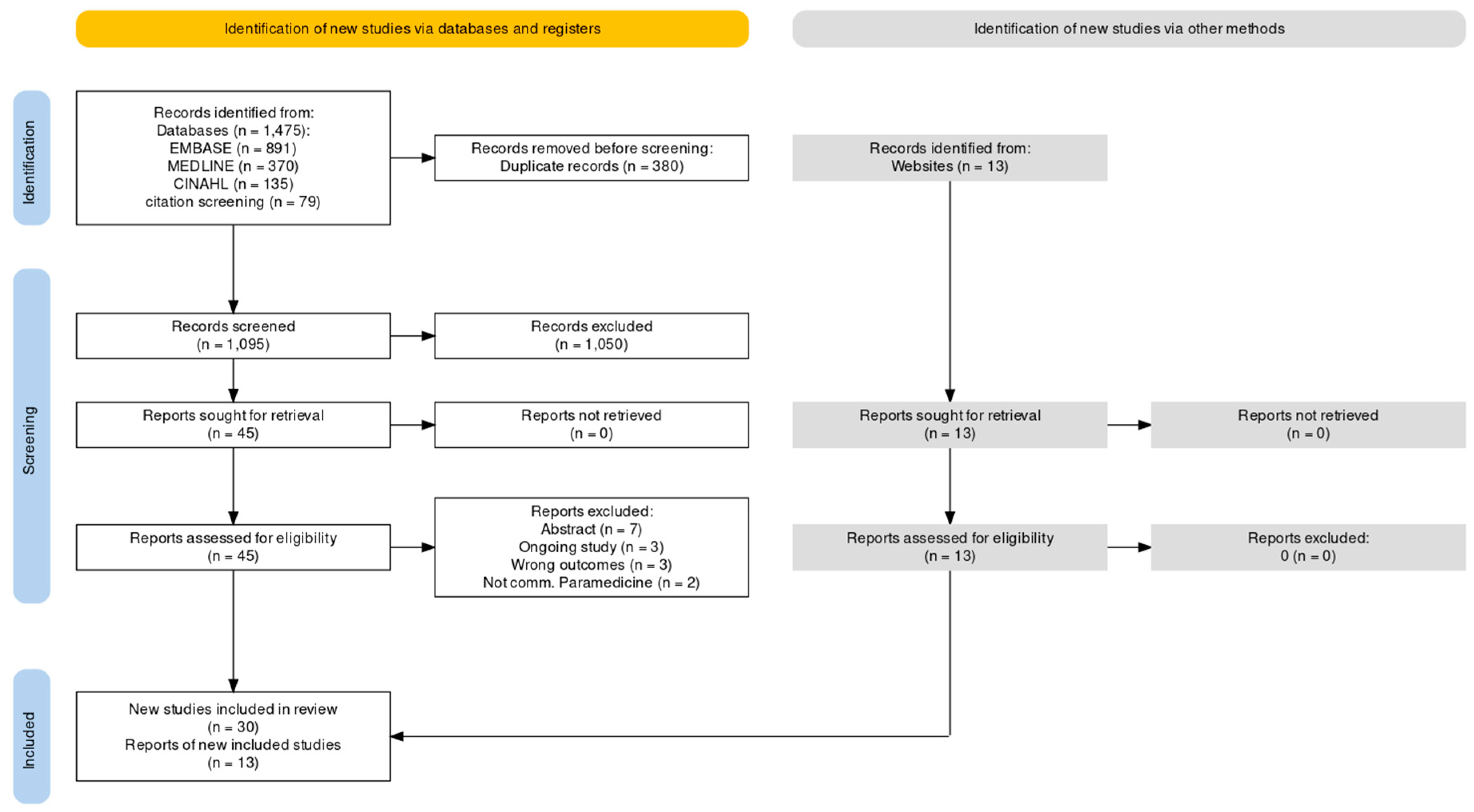

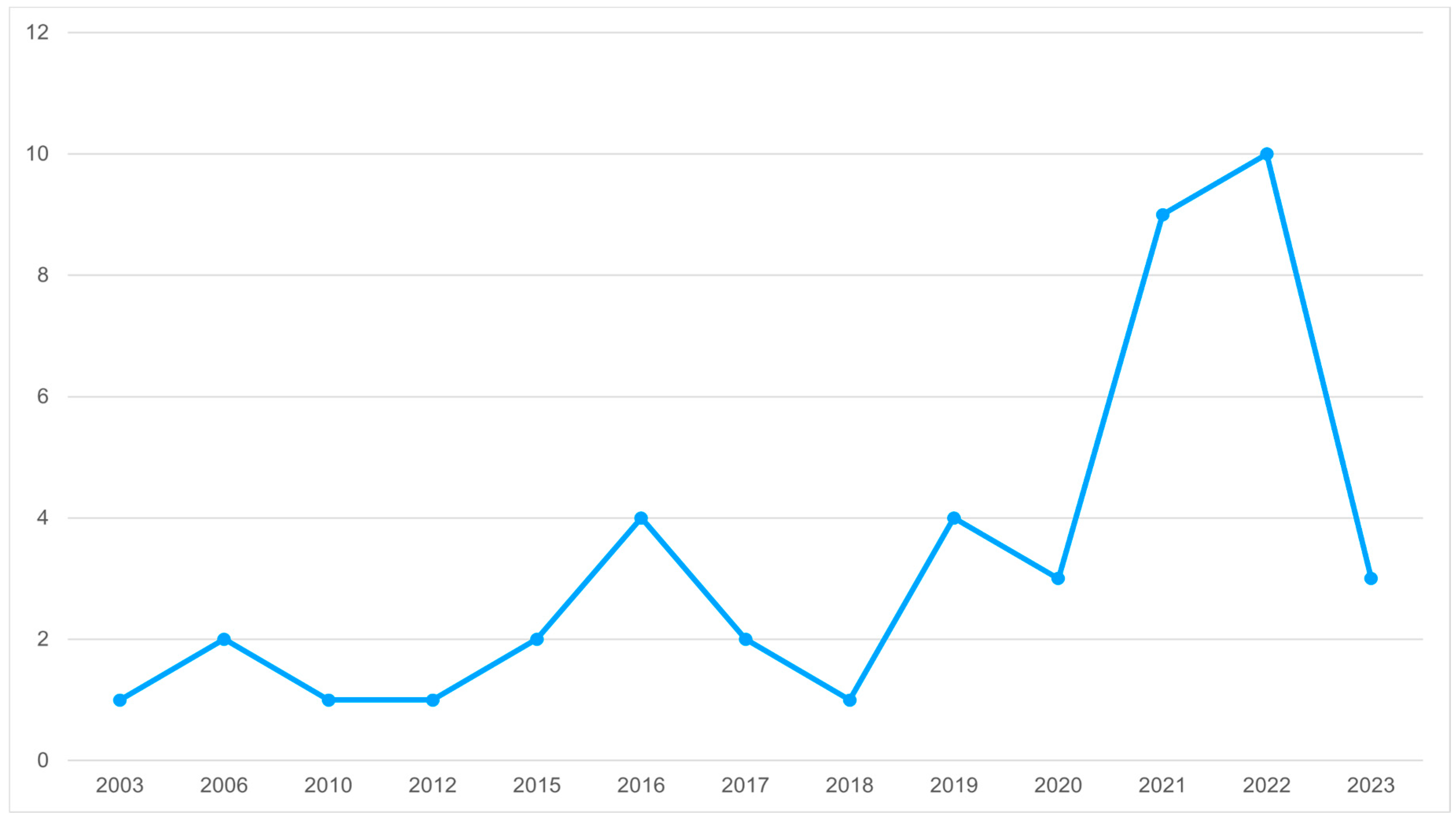

Identification of Potential Studies

Social Needs Domains

Domain 1 - Access to Health and Social Services

Domain 2 - Daily Living

Domain 3 - Mental Health and Substance Use

Domain 4 - Technology

Domain 5 - Social Support, Agency and Belonging

Community Needs Assessment

Social Needs Education

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgements

Declaration of conflicting interests

ORCID iD

Appendix A. - Search Strategy

- Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to March 31, 2023>

- Search Strategy:

- 1

- "social determinants of health".mp. (11939)

- 2

- SDoH.mp. (664)

- 3

- social needs.mp. (2234)

- 4

- poverty.mp. (65784)

- 5

- homeless*.mp. (12711)

- 6

- houseless*.mp. (18)

- 7

- "food insecurity".mp. (5926)

- 8

- "social isolation".mp. (21797)

- 9

- "community paramedicine progra*".mp. (39)

- 10

- "mobile integrated healthcare".mp.] (22)

- 11

- "mobile integrated health care".mp. (8)

- 12

- "community paramed*".mp. (153)

- 13

- "paramed*".mp. (12112)

- 14

- "community care paramedic".mp. (0)

- 15

- isolat*.mp. (2050741)

- 16

- 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 15 (2141019)

- 17

- 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 (12125)

- 18

- 16 and 17 (370)

- 18

- ***************************

Appendix B. - Data Extraction Form (within Covidence)

- Study ID

- Title

- Title of paper / abstract / report that data are extracted from

- Lead author contact details

-

Country in which the study was conducted

- United States

- UK

- Canada

- Australia

- Other

- Characteristics of included studies

- Aim/objective of study

-

Study design

- Randomised controlled trial

- Non-randomised experimental study

- Cohort study

- Cross sectional study

- Case control study

- Systematic review

- Qualitative research

- Prevalence study

- Case series

- Case report

- Diagnostic test accuracy study

- Clinical prediction rule

- Economic evaluation

- Text and opinion

- Other

- Start date

- End date

- Study funding sources

- Possible conflicts of interest for study authors

- Participants

- Population description

-

Program setting

- Rural

- Urban

- Mixed

- Other

-

Type of program

- Home visit

- Clinic

- Mobile/outreach

- Other

-

Referral source

- 911 crew

- Secondary triage

- Community referral

- MRP referral

- Discharge referral

- Other

- Inclusion criteria

- Exclusion criteria

- Total number of participants

- Primary outcome

-

Social needs assessment conducted?

- Yes

- No

- Unclear

-

Social needs addressed

- Poverty/SES

- Housing

- Food insecurity

- Social support & isolation

- Mental health/substance use

- Access to services

- Employment

- Environmental

- Health literacy

- Other

-

Paramedic education includes/targets SDoH

- Yes

- Unclear

- Other

- Notes

Appendix C. – Study Characteristics

| Author(s) and Country of Origin | Year | Methodology | Key Findings | Categories |

| Allana et al, Canada | 2021 | Text and opinion | Better integration with the health system or new payment models for paramedic services may help realign the incentive to address social determinants, particularly where there are cost savings that occur in other parts of the health system as a result of paramedic care. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Employment; Environmental; Health literacy |

| Boland et al, United States | 2022 | Cohort study | Statistically significant reductions in the mean incidence of ED utilization were observed across all sex and age groups, and reductions were observed irrespective of home visit frequency and quartile of baseline IR of 9-1-1 calls. | Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services |

| Buitrago et al, United States | 2022 | Other: Root Cause Analysis (RCA) | The top 5 root causes for readmission across the 79 readmitted patients (and therefore included in the CCA) were worsening of existing disease state, poor health literacy, new disease state, poor functional status, and behavioural health issues. The most common contributing factor for readmission for those with respiratory diseases was inadequate management of an existing disease state (n 5 16, 23.5%) followed by medication management (n 5 14, 20.6%). Functional status, behavioural health issues, and income limitations each represented 7.4% (n 5 5) of the total contributing factors. Poor health literacy and functional status. |

Poverty/SES; Housing; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Health literacy |

| Chan et al, Canada | 2019 | Systematic review | Community paramedicine programs and training were diverse and allowed community paramedics to address a spectrum of population health and social needs. The types of services provided included assessment and screening, acute care and treatment, transport and referral, education and patient support, communication, and other (Table 3). Most common were physical assessment (n = 27; 46.6%), medication management (n = 23;39.7%), and assessment, referral, and/or transport to community services (n = 22; 37.9%). The training for these programs usually covered how to care for seniors; assessing the environment (e.g., home), health risks, and overall health; health promotion; and intervention-specific materials (n = 1 each; 25.0%) |

Social support & isolation; Access to services; Health literacy |

| Cockrell et al, Australia | 2019 | Systematic review | These results fall into a number of broad categories. First, the impact rurality has on health and wellbeing, and then the way paramedics respond to those challenges. Next, the way social determinants of health impact capability and resilience and potential ways paramedics can impact health resilience in their practice. Finally, an exploration of the developing practice of paramedicine and the capacity of paramedics to engage in new roles and activities as they develop, especially in reference to using a salutogenic model in practice. However, rurality alone does not equate to higher morbidity and mortality rates, but rather exacerbates socioeconomic disadvantage, decreased access to healthcare, occupational risk and environmental hazards. There is the potential for disparities in rural communities to be further addressed using a salutogenic approach by paramedics. Successful community paramedicine (CP) programs are integrated within local healthcare systems and offer reasonable options for treatment or referrals in appropriate situations while being as unique as the communities in which they serve. The recent move toward tertiary education in paramedicine has provided programs with greater opportunities for interprofessional learning (57). Interprofessional learning programs which educate paramedics to become members of the primary health team has shown to increase participation in patient education and health promotion. Most health professionals seem motivated and interested in participating in interprofessional practice, however, success is often hindered by embedded cultural behaviours and rigid professional boundaries (58) | Poverty/SES; Social support & isolation; Access to services; Environmental; Health literacy |

| Ford-Jones and Daly, Canada | 2022 | Qualitative research | The study findings outline three promising practices: diversion programmes that transfer patients to a destination other than the ED; crisis response teams that attend calls identified as involving mental health and community paramedicine programmes including referral programmes. Community Paramedicine: The most consistently mentioned programme to address psychosocial concerns is the community referral programme, often called Community Referral by Emergency Medical Services (CREMS). Community paramedicine is a rapidly expanding domain of paramedicine, with many initiatives involving a more psychosocially focused follow-up for users of paramedic services. Other mental health-related initiatives in community paramedicine included follow-up by paramedic services and other mental health workers following substance use–related calls, as well as referral programmes for those with repeat police and ambulance interactions for mental health, substance use issues or psychosocial needs. While many of these programmes relate more specifically to chronic disease or home care, mental health and substance use–related needs have come to the forefront, even during the time of the field work, particularly in relation to the opioid crisis. | Mental health/substance use; Access to services |

| Gainey et al, United States | 2018 | Case report | MIH providers were recruited early in the flood response to target vulnerable community members in need of the most assistance. The MIH team is a community-based model of care using paramedics to reach patients in their communities and homes. In addition to the novel utilization of MIH providers to assist disaster victims, the agency’s three medical control physicians, all board-certified in emergency medicine and EMS, were also utilized in novel ways. In the early hours of the disaster, many calls for assistance came from citizens whose homes could not be accessed by traditional EMS ambulances given the extensive flooding. Some calls were forwarded to the physicians for telephone triage and assessment with some patients given self-care instructions via telephone. Additionally, during the operations phase of disaster response, the medical control physicians responded to in-field calls, providing medical care and appropriately triaging patients for transport versus non-transport to local hospitals. This became important for the appropriate utilization of EMS transport units and to maintain control of patient volumes transported to local hospital emergency departments. This utilization of EMS physicians augmented the work being performed by the MIH providers. | Housing; Access to services; Environmental |

| Georgiev et al, United States | 2019 | Case report | Community Paramedicine: Patients in this CP program experience complex health conditions and have limited access to resources, which negatively affect their SDoH. Individuals with low incomes are more likely to lack health insurance and have unmet medical needs, including care coordination and access to primary care. The NPs in this CP program identify the needs of a vulnerable population, provide individualized service based on SDoH, and coordinate care with team members. They also work closely with health economists and researchers to understand federal and state regulations that may impede or improve access to care for vulnerable populations. The recommendation for CP programs is to use a multidisciplinary approach. Telemedicine: Telemedicine provides the capability for patients in homes to remotely connect to caregivers. One in four CP programs use telemedicine,16 and the use of telemedicine in CP has been proven to decrease hospital transports. Specially trained paramedics used physician-guided telemedicine to treat acutely ill patients with HF, dementia, diabetes, COPD, and decubitus ulcers in their homes. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Environmental; Health literacy |

| Hirello and Cameron, Canada | 2021 | Text and opinion | Paramedics play an important role in the Canadian healthcare system. They deliver high quality care on demand, in any region, to whomever needs it. However, for paramedics to fulfil their potential in modern healthcare, the profession must ensure its values are aligned with all other healthcare providers. This requires enactment of socially accountable practice at all levels of the paramedic profession, including educators, employers, policy makers, other healthcare providers and most importantly, practicing paramedics. | |

| Langabeer et al, Unites States | 2020 | Case report | Of the individuals who had an in-home conversation with the outreach team, 70 patients (33% success rate) engaged in same day treatment. Nearly 70% of the people we outreach to are socio-economically vulnerable, based on their lack of current employment, health insurance, or stable housing. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Employment; Health literacy |

| Leyenaar et al, Canada | 2021 | Other: Quantitative | Opportunity exists for further collaboration between community-based support services agencies and home care providers, community paramedicine home visit programs, and other parts of the healthcare continuum—particularly primary care providers—to improve coordination of care to medically complex community-dwelling older adults. High proportions of mental health-related conditions were identified in community paramedicine patients. Other research has demonstrated that mental health and social isolation can contribute to repeated 9-1-1 use. While we provided a comparison to other cohorts of community-dwelling older adults, further comparisons are needed with additional community and geriatric mental health populations. When using existing community care populations as a reference group, it appears that patients seen in community paramedicine home visit programs are a distinct sub-group of the community-dwelling older adult population with more complex comorbidities, possibly exacerbated by mental illness and social isolation from living alone. Community paramedicine programs may serve as a sentinel support opportunity for patients whose health conditions are not being addressed through timely access to other existing care providers. | Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services |

| Logan, United States | 2022 | Case report | explores how a group of paramedics were cross trained as community health workers (CHWs) in Indiana. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Employment; Environmental; Health literacy |

| McManamny et al, Australia | 2022 | Qualitative research | Key Themes: Role - trusted; visible within the community; skilled; importance of networking; widespread coverage; varied Other Service - importance of "territory"; filling a gap or void; the rural GPBarriers - other services; funding; time Activities - opportunities; individual community needs; hospital avoidance The results of this study suggest that paramedic health education for rural-dwelling older people is both feasible and acceptable to older people and to the community; however, a range of barriers challenge the concept of paramedics working within this expanded scope. |

Social support & isolation; Access to services; Health literacy |

| Moczygemba et al, Unites States | 2021 | Qualitative research | Qualitative data indicated that unlimited smartphone access allowed participants to meet social needs and maintain contact with case managers, health care providers, family, and friends. mHealth interventions are acceptable to people experiencing homelessness. HIE data provided more accurate ED and hospital visit information; however, unlimited access to reliable communication provided benefits to participants beyond the study purpose of improving care coordination. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Employment; Health literacy |

| Mund et al, United States | 2016 | Text and opinion | mobile integrated health units address gaps and barriers experienced by geographically, socially, economically and/or culturally isolated to accessing health and social services | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Employment; Environmental; Health literacy; Other: refugee, immigration status |

| Naimi et al, United States | 2023 | Diagnostic test accuracy study | It was common for patients to have more than seven individual SDoH needs. The most frequently identified individual SDoH needs were categorized in the Coordination of Healthcare (37.7% of all needs), Durable Medical Equipment (18.8%), and Medication (16.3%) domains. The four needs correlated with the largest statistically significant increases in 30-day hospital utilization—portable oxygen, social security card, home health, and physical therapy—are also correlated with statistically significant increases in HOSPITAL score, making them good targets for focused interventions. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Employment; Environmental; Health literacy; Other: durable medical equipment - transportation - utilities - access to ID documents - coordination of health care needs - medication |

| Pennel et al, United States | 2016 | Other: comparative case study | Across the three paramedic care coordination sites, four major themes emerged. These were: (1) a shift in the paramedic and patient interactions from episodic, crisis- based to longer- term, ongoing; (2) aspects of the rural environmental and social context that enabled and constrained paramedic care coordination programs; (3) impacts of care coordination including patient peace of mind as well as improved use of preventive health care and disease self- management; and (4) major concerns voiced about programs’ sustainability. | Poverty/SES; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Environmental; Health literacy; Other: education - language barriers - uninsured - disability - immigration status - transportation - healthcare coordination |

| Pirrie et al, Canada | 2020 | Cross sectional study | Measurements: poverty, food insecurity and risk factors. The poverty rate was lower than expected which could be related to the surrounding environment and perceptions around wealth. Food insecurity was approximately twice that of the general population of older adults in Canada, which could be related to inaccessibility and increased barriers to healthy foods. For those who reported being food secure, dietary habits were considered poor. While social housing may function as a financial benefit and reduce perceived poverty, future interventions are needed to improve the quality of diet consumed by this vulnerable population. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services |

| Rahim et al, United States | 2022 | Text and opinion | Community Paramedicine has potential to enable value-based care models, increase access to primary care, reduce burden on EMS and EDs - specifically filling gaps for marginalized populations accessing primary care. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Employment; Environmental; Health literacy |

| Ridgeway et al, United States | 2023 | Qualitative research | The clinic received favourable survey ratings on acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility, program favourability (mean [SD], 4.5 [0.9]), likelihood to recommend (mean [SD], 4.6 [0.9]), and accessibility (mean [SD], 4.2 [0.8]), all on 1–5 scales, with slight variations across groups (Appendix, Exhibit 1). Interviews deepened understanding of implementation (Table 4). | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services |

| Rosa et al, Canada | 2021 | Text and opinion | The literature has identified discrepancies with the delivery of timely and accessible in-home palliative care.13 Community paramedicine has been suggested as a viable option to bridge this gap. | Social support & isolation; Access to services |

| Ruest et al, Canada | 2016 | Text and opinion | Community Paramedics are in an excellent position to see the importance of health promotion and injury prevention and can use their position in the community to advocate on the part of the client and community, thereby drawing attention from the traditional illness care to a broader aspect of treatment, promotion and prevention. Community Paramedics can easily expand their role to become Health Promotion experts and advocates of the rural older adult population, ensuring that each person has equitable access to all resources required to advert social isolation. “We hope that, regardless of where they live, older people enjoy equal opportunity of access to services for equal needs”. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Access to services; Employment; Environmental; Health literacy |

| Schwab-Reese et al, United States | 2021 | Qualitative research | Participants viewed the community paramedic as a trusted provider who supplied necessary health information and support and served as their advocate. In their role as physician extenders, the community paramedics enhanced patient care through monitoring critical situations, facilitating communication with other providers, and supporting routine healthcare. Women noted how community paramedics connected them to outside resources (i.e., other experts, tangible goods), which aimed to support their holistic health and wellbeing. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Employment; Environmental; Health literacy; Other: Education |

| Shannon et al, Australia | 2022 | Systematic review (rapid) | The outcome measures reported show that there is evidence to support the implementation of community paramedicine into healthcare system design. Community paramedicine programmes result in a net reduction in acute healthcare utilisation, appear to be economically viable and result in positive patient outcomes with high patient satisfaction with care; This review identified and explored community paramedicine literature focused on five key areas: education, models of delivery, governance and clinical support, the scope of the role and outcomes associated with community paramedic models. Models of care delivery: community assessment/referral; community paramedic-led clinics; home visit programs; remote patient monitoring; community paramedicine specialist response; hospital discharge/transitional care support; palliative care; influenza surge programs; COVID response programs. A key recommendation and lesson reported in the literature across multiple studies was the essential role of understanding the community needs and factors that enabled a sustainable community paramedicine programme (Leyenaar, McLeod, et al., 2019; Pearson & Shaler, 2017; Seidl et al., 2021). O'Meara et al. (2015) advised that engaging appropriately with the community can result in more integrated paramedic services, working as part of a less-fragmented system across the health, aged care and social service sectors. This was found to also be important to prevent duplication and overlap of existing service delivery (Feldman et al., 2021). The findings of this review demonstrate a lack of research and understanding of the education and scope of the role of community paramedics, and also highlighted a need to develop common approaches to education and scope while maintaining flexibility in addressing community needs. There was a lack of standardisation in the implementation of governance and supervision models which may prevent community paramedicine from realising its full potential. Finally, although there has been an increased focus on outcomes in the literature, such reporting is inconsistent. This inconsistency, and the gaps evident across the other areas of focus, makes it difficult to articulate what community paramedicine programmes can achieve and their impacts on the healthcare system. | Access to services |

| Sokan et al, United States | 2022 | Case control study | This pilot study demonstrated a trend toward improved medication adherence among patients enrolled in the MIH-CP program. | Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Environmental; Health literacy |

| Stickler et al, United States | 2021 | Case report | The Mobile COVID-19 Unit was rapidly developed and deployed. It was successful in educating patients on self-management, provision of timely medical care for COVID-19 and other acute and chronic health conditions and building trust with this underserved community. The Unit also supported COVID-19 vaccination of unsheltered adults in conjunction with OCPH. Success of this program was predicated on close communication between the CP team, Olmsted County Housing Stability Team, and shelter staff; versatility of CP skills spanning education, social support, and medical evaluation/management; and endorsement by community partners respected by the homeless community. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Employment; Environmental; Health literacy |

| Strum et al, Canada | 2015 | Text and opinion | Paramedics are well positioned to serve as health advocates to respond to individual patient health needs, respond to health needs of the communities, identify determinants of health of populations they serve, and promote the health of individual communities and populations. Community Paramedicine is an evolving service model that enabled paramedics as health advocates. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Access to services; Employment; Health literacy; Other: Education - Early Childhood Development - Working Conditions |

| Swayze et al, United States | 2016 | Text and opinion | Mobile Integrated Healthcare-Community Paramedicine (MIH-CP) supports chronic disease by addressing individuals' determinants of health through 1. patient education 2. medication inventory/reconciliation and connecting individuals to 3. social support interventions 4. environmental interventions 5. economic support interventions | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Employment; Environmental; Health literacy |

| Taplin et al, Canada | 2022 | Cohort study | Emergency department visits were unchanged following the initial visit, while there were significant increases in community-based care.In the year following the initial community paramedic visit there were small but significant increases in community-based care utilization of people experiencing homelessness. These data suggest that the continued development and implementation of paramedics as part of an interdisciplinary care team can increase access to care for a traditionally underserved population with complex health needs. Patients would likely benefit from the integration of community paramedics in community-based management that aim to improve access to care following ED visits. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Employment; Environmental; Health literacy |

| Taplin et al, Canada | 2023 | Qualitative research | The community paramedics address the health and social needs of individuals experiencing homelessness (IEH) while working in a multidisciplinary setting. The CCT is an innovative program that can inform future health service design in similar settings. | Poverty/SES; Housing; Food insecurity; Social support & isolation; Mental health/substance use; Access to services; Employment; Environmental; Health literacy |

| Newall, Canada | 2015 | Grey Lit | Paramedics with Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Services beginning to do more preventative community work – calling this community paramedicine. Community Paramedic initiative Emergency Paramedics in the Community (EPIC) project – focuses on common 911 callers; perform in-community medical assessments; refer to community resources. Main purpose is to provide preventative medical care and prevent unnecessary 911 calls proactively. EPIC targets frequent 911 callers and at-risk individuals, including those isolated, substance misuse, mental illness, chronic disease | social isolation; loneliness, food security, elder abuse, mental health, substance use; access to services |

| Raven et al, Australia | 2006 | Grey Lit | Review summary of expanded paramedic roles supporting social needs; Nova Scotia, Canada community-initiated community paramedicine program to address healthcare needs of citizens geographically isolated on an island; East Anglian Ambulance Service, UK operationalized community paramedics in urban areas to address gaps in accessing health services, linking nursing-social-mental health teams to persons receiving care | remote/rural, social isolation, access to health services, mental health |

| Thomas-Henkel and Schulman, United States | 2017 | Grey Lit | Community paramedics use an electronic record tool to screen for SDoH during home visits; electronic record is integrated with EPIC EMR allowing for interprofessional reporting and referrals; community paramedics are well positioned for screening and assessments based on their unique understanding of communities | substance use; race; ethnicity; income/SES; education; intimate partner violence (IPV)/; interpersonal safety/violence; physical activity; social isolation; insurance status; incarceration; mental health; food security; housing; legal barriers; childcare; working conditions; access to health services; medications; transportation; language barriers; refugee status; temporary foreign worker; veteran status |

| Olynyk, Canada | 2010 | Grey Lit | Utilizes CPs to connect individuals to core services: nursing, personal support, PT/OT, Speech-Language Therapy, extreme cleaning and secondary services: social work, nutritional counselling, medical equipment/supplies, health care referrals, public health, health education, long term care placement | care coordination; disability; mental health (including hoarding); people who use drugs or alcohol; cognitive pathology (dementia); need for Supportive Living placement; homelessness; social isolation |

| Nolan et al, Canada | 2012 | Grey Lit | overview of Community Paramedicine programs across Canada; some service delivery involves the provision of connecting health and social services, filling healthcare gaps, access to health services, remote/rural healthcare service; service to marginalized populations | access to health services; remote/rural living; social isolation; living environment; age; gender; income/SES; poverty; cultural isolation/social integration |

| Misner, Canada | 2003 | Grey Lit | Community paramedicine, while not a new idea, has never before been used in collaboration with a nurse practitioner and an off-site physician. Expanded paramedic role to address geographically isolated citizens; community-initiated/community-led; community needs-assessment via town-hall engagement followed by survey; off-site physician oversight; supported with additional paramedic education sessions to prepare for expanded community work; increased paramedic coverage, paramedic-staffed clinics for screening, prevention, health promotion; incorporated NP collaborative practice – enabled expansion to more complex care services; lab diagnostics; relationship building with Islanders; building collaborative relationships with community services and health professionals such as Home Care | Remote/rural living; access to health services |

| Hay, Canada | 2006 | Grey Lit | Community Paramedicine as an innovative model addressing gaps in healthcare service delivery to vulnerable populations | rural living; homelessness |

| Ashton and Leyenaar, Canada | 2019 | Grey Lit | This case study demonstrates that CSA Z1630 does provide useful guidance for the implementation of community paramedicine in a remote Indigenous community in the North. In the absence of an existing paramedic service, the findings of the study show that while specific aspects of the Standard are applicable, other elements would only be applicable once a paramedic service was established. The report identifies a number of areas where revisions to the Standard would make it more applicable to address the needs of remote Indigenous communities, such as relevant program indicators and broader stakeholder and partner participation in community paramedicine planning, and program and service delivery.; community-needs assessment, consultation; community member, services and interprofessional collaboration | remote/rural living; social isolation; access to health services; income/SES; employment/working conditions; education/literacy; childhood experiences; physical environment; social supports/coping skills; culture |

| CSA, Canada | 2017 | Grey Lit | National Standard to provide guidance to fully understand context, key considerations, and essential elements for community paramedicine program development; Section 5.3 Specialized Capabilities, g) understanding the social determinants of health | access to health services; remote/rural living; social isolation; living environment; age; gender; income/SES; poverty; cultural isolation/social integration |

| Batt et al, Canada | 2021 | Grey lit | Community paramedicine programs have evolved to meet the needs of their communities. They have achieved this by responding to COVID-19 in collaboration with public health agencies; leveraging technology to facilitate remote monitoring and virtual visits; addressing social inequities in their communities, such as access to health care and social services; and by meeting the needs of vulnerable populations, who already faced issues in equity of access to services prior to the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the essential collaborative care role community paramedicine programs can provide to patients in their homes or communities. These programs have demonstrated their ability to support public health measures, provide home and community-based care, and most importantly, collaborate with other health care professionals in coordinating and providing care to Canadians regardless of social circumstances. | older adults; race/ethnicity (Indigenous Peoples); homelessness; palliative care; people who use drugs; immigrants and migrant workers; incarcerated; food security; poverty; health literacy; internet access; caregiver support; care coordination |

| PHECC, Ireland | 2020 | Grey Lit | Community Paramedicine is an opportunity to combine emergency care with primary care to support health equity in rural regions; Report Recommendations: 1. focus on shifting care from acute hospital to community 2. include the word "paramedic' in the title determined for Community Paramedic practitioner 3. mainstreaming of community paramedicine to Ireland and engage with wider stakeholders 4. set standards and educational outcomes 5. integrate community paramedicine into primary and acute care 6. take cognisance of the evaluation of pilot projects 7. engage a sub-group to set clinical standards 8. robust clinical governance structures, licensed providers 9. enabling legislation changes | access to health services; rural living |

| Shannon et al, Australia | 2021 | Grey lit | scoping review spanned 7 countries; varied program models and education requirements; over-arching themes relevant to supporting social needs 1. community-needs 2. collaboration, interprofessional, community, stakeholders 3. communication for role clarity, misconceptions 4. support of CP, experienced paramedic recruitment, workforce support 5. research, evaluation, data-sharing. Core: community-centred approaches, interprofessional practice, and program evaluation as enabling factors of community paramedicine program development and implementation | access to health services; |

| PHECC, Ireland | 2022 | Grey Lit | framework founded on community paramedicine model: 1. healthcare service 2. specialist paramedic - community care 3. community need; potential settings of care include integrated health-social service; scope of practice addresses SDoH, social needs; educational domains to support social needs - integration into primary care, communications, teamwork | health promotion; health literacy; substance use; mental health; homelessness; palliative care; care coordination; health and social services referrals; advocacy |

References

- Allana A, Pinto AD. Paramedics Have Untapped Potential to Address Social Determinants of Health in Canada (2021, accessed 26 April 2023).

- 2. Tavares W, Allana A, Beaune L; et al. Principles to Guide the Future of Paramedicine in Canada. Prehospital Emergency Care, 2021; 1–11.

- Tavares W, Bowles R, Donelon B. Informing a Canadian paramedic profile: Framing concepts, roles and crosscutting themes. BMC Health Serv Res 2016, 16, 477. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon B, Eaton G, Lanos C; et al. The development of community paramedicine; a restricted review. Health & Social Care in the Community 2022, 30, e3547–e3561. [Google Scholar]

- Wingrove, G. International Roundtable on Community Paramedicine. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, Epub ahead of print 7 February 2011. [CrossRef]

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health : Final report of the commission on social determinants of health. Combler le fossé en une génération : Instaurer l’équité en santé en agissant sur les déterminants sociaux de la santé : Rapport final de la Commission des Déterminants sociaux de la Santé 2008, 247.

- Essington T, Bowles R, Donelon B. The Canadian Paramedicine Education Guidance Document.

- Porroche-Escudero, A. Health systems and quality of healthcare: Bringing back missing discussions about gender and sexuality. Health Systems 2022, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IISD. Who Is Being Left Behind in Canada? International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2023. Available online: https://www.iisd.org/articles/insight/who-being-left-behind-canada (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Available online: https://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/301/weekly_acquisition_lists/2015/w15-24-F-E.html/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-7-2015-eng.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Shannon B, Batt AM, Eaton G; et al. Community Paramedicine Practice Framework Scoping Exercise. https://www.phecit.ie/Custom/BSIDocumentSelector/Pages/DocumentViewer.aspx?id=oGsVrspmiT0dOhDFFXZvIz0q5GYO7igwzB6buxHEgeAwoe6hhx3Qzd%252fCRqybt66szE0PsYSC8wDndnJ4ZZBtixIuvZKX1%252f4wN58oIZl8uwPebsYwRo0IvX6hVCWn5T8FxWsBQJfWSaVSf%252bRJ%252b80BMTb0c8d%252b63Hj (2021, accessed 18 May 2023).

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C; et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Crenshaw KW, McCall L. Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 2013, 38, 785–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, SA. The coin model of privilege and critical allyship: Implications for health. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC; et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey Matters: A practical tool for searching health-related grey literature | CADTH. https://www.cadth.ca/grey-matters-practical-tool-searching-health-related-grey-literature (accessed 11 June 2023).

- Haddaway NR, Grainger MJ, Gray CT. citationchaser: An R package and Shiny app for forward and backward citations chasing in academic searching. Epub ahead of print 16 February 2021. [CrossRef]

- Francis, E. 11.2.8 Analysis of the evidence - JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - JBI Global Wiki. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687681 (accessed 11 June 2023).

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual Health Res 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas E, Magilvy JK. Qualitative Rigor or Research Validity in Qualitative Research. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing 2011, 16, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton C, Leyenaar MS. Health Service Needs in the North: A Case Study on CSA Standard for Community Paramedicine; Canadian Standards Association: Canada.

- Batt AM, Hultink A, Lanos C; et al. Advances in Community Paramedicine in Response to COVID-19.

- Cockrell KR, Reed B, Wilson L. Rural paramedics’ capacity for utilising a salutogenic approach to healthcare delivery: A literature review. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine; 16. Epub ahead of print 23 April 2019. [CrossRef]

- Misner, D. Community Paramedicine: A Part of an Integrated Health Care System. 2003. Available online: https://ircp.info/Portals/11/Downloads/Expanded%20Role/Community%20Paramedicine.pdf?ver=TfO8p2_1qDzq4LlLyNLlqA%3d%3d (accessed 18 May 2023).

- Buitrago I, Seidl KL, Gingold DB; et al. Analysis of Readmissions in a Mobile Integrated Health Transitional Care Program Using Root Cause Analysis and Common Cause Analysis. J Healthc Qual 2022, 44, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokan O, Stryckman B, Liang Y; et al. Impact of a mobile integrated healthcare and community paramedicine program on improving medication adherence in patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after hospital discharge: A pilot study. Exploratory Research in Clinical and Social Pharmacy 2022, 8, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olynyk, C. Toronto EMS Community Paramedicine Program Overview 2010. 2010. Available online: https://ircp.info/Portals/11/Downloads/Expanded%20Role/Toronto%20CREMS/Toronto%20EMS%20Community%20Paramedicine%20Program%20Overview%202010.pdf?ver=Vn9xFmVDYfFxk0pJG0QiFw%3d%3d (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Taplin J, Dalgarno D, Smith M; et al. Community paramedic outreach support for people experiencing homelessness. Journal of Paramedic Practice, 15.

- Schwab-Reese LM, Renner LM, King H; et al. “They’re very passionate about making sure that women stay healthy”: A qualitative examination of women’s experiences participating in a community paramedicine program. BMC Health Serv Res 2021, 21, 1167. [Google Scholar]

- Pennel CL, Tamayo L, Wells R; et al. Emergency Medical Service-based Care Coordination for Three Rural Communities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 2016, 27, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruest, M. County of Renfrew Paramedic Service Resilience Program Contribution to the Health Promotion Strategies that Address the Inequities Associated with Social Isolation of Seniors in the County of Renfrew. Canadian Paramedicine 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Boland LL, Jin D, Hedger KP; et al. Evaluation of an EMS-Based Community Paramedic Pilot Program to Reduce Frequency of 9-1-1 Calls among High Utilizers. Prehospital Emergency Care 2022, 1–8.

- Georgiev R, Stryckman B, Velez R. The Integral Role of Nurse Practitioners in Community Paramedicine. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners 2019, 15, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langabeer JR, Persse D, Yatsco A; et al. A Framework for EMS Outreach for Drug Overdose Survivors: A Case Report of the Houston Emergency Opioid Engagement System. Prehospital Emergency Care 2021, 25, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, RI. ‘I Certainly Wasn’t as Patient-Centred’: Impacts and Potentials of Cross-Training Paramedics as Community Health Workers. Anthropology in Action 2022, 29, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManamny TE, Boyd L, Sheen J; et al. Feasibility and acceptability of paramedic-initiated health education for rural-dwelling older people. Health Education Journal 2022, 81, 848–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moczygemba LR, Thurman W, Tormey K; et al. GPS Mobile Health Intervention Among People Experiencing Homelessness: Pre-Post Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e25553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mund, E.; Taking Care to the Streets. EMSWorld. 2016. Available online: https://lw.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/emsworld/article/12179630/taking-mih-cp-care-to-the-streets (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Rahim F, Jain B, Patel T; et al. Community Paramedicine: An Innovative Model for Value-Based Care Delivery. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice; Publish Ahead of Print. Epub ahead of print 2 December 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gainey CE, Brown HA, Gerard WC. Utilization of Mobile Integrated Health Providers During a Flood Disaster in South Carolina (USA). Prehosp Disaster med 2018, 33, 432–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taplin JG, Barnabe CM, Blanchard IE; et al. Health service utilization by people experiencing homelessness and engaging with community paramedics: A pre–post study. Can J Emerg Med 2022, 24, 885–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgeway JL, Wissler Gerdes EO, Zhu X; et al. A Community Paramedic Clinic at a Day Center for Adults Experiencing Homelessness. NEJM Catalyst; 4. Epub ahead of print 15 March 2023. [CrossRef]

- Stickler ZR, Carlson PN, Myers L; et al. Community Paramedic Mobile COVID-19 Unit Serving People Experiencing Homelessness. Ann Fam Med 2021, 19, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strum, R. Paramedics as Health Advocates. Canadian Paramedicine 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas-Henkel C, Schulman M. Screening for Social Determinants of Health in Populations with Complex Needs: Implementation Considerations.

- Pirrie M, Harrison L, Angeles R; et al. Poverty and food insecurity of older adults living in social housing in Ontario: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1320. [Google Scholar]

- Leyenaar MS, McLeod B, Jones A; et al. Paramedics assessing patients with complex comorbidities in community settings: Results from the CARPE study. Can J Emerg Med 2021, 23, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford-Jones PC, Daly T. Filling the gap: Mental health and psychosocial paramedicine programming in Ontario, Canada. Health Social Care Comm 2022, 30, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newall, N. Who’s At My Door Project: How organizations find and assist socially isolated older adults. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Centre on Aging.

- Nolan M, Hillier T, D’Angelo C. Community Paramedicine in Canada. 2012. Available online: https://ircp.info/Portals/11/Downloads/Policy/Comm%20Paramedicine%20in%20Canada.pdf?ver=XJMZv0HNBUMEpxqc9etOFg%3d%3d (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Naimi S, Stryckman B, Liang Y; et al. Evaluating Social Determinants of Health in a Mobile Integrated Healthcare-Community Paramedicine Program. J Community Health 2023, 48, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raven S, Tippett V, Ferguson J-G; et al. An exploration of expanded paramedic healthcare roles for Queensland. Queensland, Australia: Australian Centre for Prehospital Research.

- Hay D, Varga-Toth J, Hines E. Frontline Health Care in Canada: Innovations in Delivering Services to Vulnerable Populations. Research Report F, 63, September 2006. 20 September; 63.

- PHECC. The introduction of Community Paramedicine into Ireland. 2020. Available online: https://www.phecit.ie/Custom/BSIDocumentSelector/Pages/DocumentViewer.aspx?id=oGsVrspmiT0dOhDFFXZvIz0q5GYO7igwzB6buxHEgeDKMmmW%252fnE3lbsxRkYxd6aQYk7snfcymr0EG16DvMZvqmNsz5SqfTY2bCjDsrkmvfchr0f6fWdxsRfEpP0eHF2WFYnnA1HA6sq8buhbiuE7hUxFSMEFO%252btRyWB31RTiP1quSbFCsa%252bZGt6Ri4g1h1nnWZcXksZCSqw%253d (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Hirello L, Cameron C. Improving Paramedicine through Social Accountability. Canadian Paramedicine, 2021. https://canadianparamedicine.ca/special-editions/ (2021).

- Chan J, Griffith LE, Costa AP; et al. Community paramedicine: A systematic review of program descriptions and training. CJEM 2019, 21, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PHECC. Community Paramedicine in Ireland: a framework for the specialist paramedic. Available online: https://www.phecit.ie/Custom/BSIDocumentSelector/Pages/DocumentViewer.aspx?id=oGsVrspmiT0dOhDFFXZvIz0q5GYO7igwzB6buxHEgeDq00klOJxrAiwRg8WilA7iQpuh0JuuyxLZ%252fgoqHj9YAdVJBi%252feIjLQQQejAdgErxHc1gOlnYuCfGcZtM%252fFZTDuGELCeo4hOpwR2WpMNptaZMMl%252biPM01lTiSTAjYn0UiWidbzfXGJzNluN5VUHbqIsRWHtJZQ5aTg%253d (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Agarwal G, Lee J, McLeod B; et al. Social factors in frequent callers: A description of isolation, poverty and quality of life in those calling emergency medical services frequently. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 684. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal G, Brydges M. Effects of a community health promotion program on social factors in a vulnerable older adult population residing in social housing. BMC Geriatr 2018, 18, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal G, Keenan A, Pirrie M; et al. Integrating community paramedicine with primary health care: A qualitative study of community paramedic views. CMAJ Open; 10. Epub ahead of print 2022. [CrossRef]

- Batt AM, Bank J, Bolster J. Canadian Paramedic Landscape Review and Standards Roadmap.

- Bolster J, Batt AM, Pithia P. Emerging Concepts in the Paramedicine Literature to Inform the Revision of a Pan-Canadian Competency Framework for Paramedics: A Restricted Review. Epub ahead of print 2022. [CrossRef]

- First Nation Information Governance Centre - OCAP Principles. The First Nations Information Governance Centre. https://fnigc.ca/ (accessed 11 June 2023).

- Rosa A, Dissanayake M, Carter D; et al. Community paramedicine to support palliative care. Progress in Palliative Care 2021, 0, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- CSA. Community paramedicine: Framework for program development. 2017. Available online: https://www.csagroup.org/store-resources/documents/codes-and-standards/2425275.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Gebhard A, McLean S, St Denis V. White benevolence: Racism and colonial violence in the helping professions. Canada: Fernwood Publishing Company, 2022. 2022.

- O’Meara P, Ruest M, Stirling C. Community Paramedicine: Higher Education as An Enabling Factor. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine 2014, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAEMSE. NAEMSE Consensus Statement on Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2023. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10903127.2023.2212753?download=true (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Alsan M, Garrick O, Graziani G. Does Diversity Matter for Health? Experimental Evidence from Oakland. American Economic Review 2019, 109, 4071–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe RP, Krebs W, Cash RE; et al. Females and Minority Racial/Ethnic Groups Remain Underrepresented in Emergency Medical Services: A Ten-Year Assessment, 2008–2017. Prehospital Emergency Care 2020, 24, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz KM, Arora TK, Termuhlen PM; et al. Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in Medicine: Why It Matters and How do We Achieve It? Journal of Surgical Education 2021, 78, 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudman JS, Farcas A, Salazar GA; et al. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the United States Emergency Medical Services Workforce: A Scoping Review. Prehospital Emergency Care 2023, 27, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Social Science & Medicine 2014, 103, 126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo EG, Isom J, DeBonis KL; et al. Reconsidering Systems-Based Practice: Advancing Structural Competency, Health Equity, and Social Responsibility in Graduate Medical Education. Academic Medicine 2020, 95, 1817–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coletto, D. Canadians Are Ready for Paramedics to Do More in Healthcare: Abacus Data Poll. 2023. Available online: https://abacusdata.ca/pac-2023/ (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Allana A, Tavares W, Pinto AD; et al. Designing and Governing Responsive Local Care Systems – Insights from a Scoping Review of Paramedics in Integrated Models of Care. IJIC 2022, 22, 5–1. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, B.; First Peoples, Second Class Treatment. Toronto: Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute. 2015. Available online: https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Summary-First-Peoples-Second-Class-Treatment-Final.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

| Country | Number of studies n (%) |

|---|---|

| Canada | 19 (44) |

| United States | 17 (39) |

| Australia | 5 (12) |

| Ireland | 2 (5) |

| Total | 43 |

| Domain | Domain 1 - Access to Health & Social Services | Domain 2 - Daily Living | Domain 3 - Mental Health & Substance Use | Domain 4- Technology | Domain 5- Social Support, Agency & Belonging | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of studies n= 43 | n= 42 | n=30 | n=28 | n=3 | n=33 | |

| Included codes | care coordination medications health literacy rural living palliative care hospice referrals in-home services caregiver support prevention/screening health promotion health insurance disability support safe childcare language barriers supportive living |

income education safe housing food security safe employment reliable transportation clean air clean water heating/cooling electricity |

mental health services drug cessation alcohol cessation tobacco cessation safe supply harm reduction |

reliable internet cell phone tablet computer email access medical equipment mobility devices fall prevention |

social isolation loneliness intimate partner violence physical safety cultural isolation race, ethnicity gender sexuality identity documentation (ID) incarceration immigration status refugee status migrant worker veteran status older adults |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).