1. Introduction

The field of underwater image processing has encountered significant challenges and attracted many researchers in recent decades. Images captured in underwater scenarios are altered in every aspect due to the changes in radiant energy when traveling through water rather than air. Light propagating underwater is scattered by tiny particles in suspension (quartz sand, clay minerals, plankton, etc.) and absorbed by water, resulting in blurred imaging and reduced color contrast [

1]. The energy absorption varies with wavelengths and types of water, generating perceived color distortions at different distances [

2]. Accurate feature extraction from underwater images is crucial for various tasks in underwater visual applications, including the detection of subsea pipelines and underwater target recognition. However, unique characteristics of underwater images, such as light attenuation, color distortion, and object blurring, bring difficalties for feature extraction. Consequently, researchers have conducted comprehensive studies to address the problem regarding underwater images.

The conventional approach for image feature extraction involves detecting handcrafted feature points. [

3] proposed the Scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT) for extracting distinctive scale-invariant features from images. The key step is the creation of the Difference of Guassian (DOG), followed by the completion of the feature point detection, orientation estimation and generation of a descriptor. This approach demonstrates robustness to variations in lighting and local shape, thereby enhancing the reliability of feature extraction. Speeded Up Robust Features (SURF) [

19] approximates or even outperforms SIFT in terms of repeatability, uniqueness, and robustness, while also being much faster to compute and compare. The KAZE [

20] and AKAZE [

21] are designed to detect feature points by constructing a nonlinear scale space and detecting them within this space. These approach help to preserve more image details. The Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF (ORB) was proposed by [

4]. The ORB consists of FAST and BRIEF. The FAST algorithm detects pixels with rapid changes in grayscale image pixel values by comparing pixel values with only four equidistant pixels. Subsequently, the BRIEF algorithm generates a binary descriptor vector based on these feature points. This binary descriptor vector can be computed and stored quickly, improving real-time performance for image feature extraction.

With the development of deep learning, the advantages of neural network learning methods driven by big data for extracting image features are gradually being manifested. [

5] proposed a combined approach called KeyNet. This method first detects manual features and then feeds these features into the neural network. However, it is important to note that the algorithm’s performance is limited to clear images. [

6] proposed ResFeats, a vector representation for features extracted from underwater images. ResFeats are extracted from underwater images using a ResNet network that has been pre-trained on ImageNet. [

7] introduced LIFT, a CNN framework designed for end-to-end learning of invariant feature transformations. The LIFT framework consists of three components: a feature detector, a direction estimator, and a descriptor generator. These components work together to mitigate the effects of changes in light using deep learning techniques. [

8] proposed a CNN-based UIE-Net network, which is an end-to-end learning framework designed to enhance underwater images. The network can learn powerful feature representations simultaneously through a unified training approach. A pixel destruction strategy is employed within the learning framework to improve convergence speed and accuracy. [

9] presented a novel feature extraction model to enhance underwater image classification. The model combines the strengths of unsupervised autoencoders and incorporates a hybrid design to accurately process large-scale underwater images. [

10] proposed a cross-modal knowledge distillation framework for underwater image processing. They pre-trained the SuperPoint [

13] network on aerial images and performed transfer learning using underwater datasets. DeLF [

23] is an attention-based feature extraction network. This method first trains the feature map and then detects key points on top of the feature map. The detectors are based on high-level semantic features. D2-Net proposed by [

24] uses dense feature extraction and description. By postponing the detection to a later stage, the obtained keypoints are more stable than traditional counterparts based on early detection. [

27] proposes the use of a binary descriptor normalization layer in the network, which enables the generation of binary descriptors with a fixed number of binary descriptors. It improves the network operation speed, descriptor matching speed. And IF-Net [

22] aims to generate a robust and generalized descriptor under critical light change conditions.

In summary, the current research primarily focuses on processing aerial and clear underwater images, while feature extraction for blurred underwater images remains a challenge. Therefore, this paper proposes a method based on the self-attention [

25] mechanism to enhance the robustness of feature extraction from blurred underwater images. This is achieved by introducing self-attention mechanisms between convolutional layers and performing transfer learning on blurry underwater images using the SuperPoint-based network. Subsequently, feature extraction comparison experiments are conducted using a simulated blurred underwater image dataset and the Real-world Underwater Image Enhancement (RUIE) [

11] dataset to validate the effectiveness and stability of the network proposed in this paper.

The novelties/innovations of this study are as follows:

- 1)

A fuzzy algorithm is used to blur the NTNU image dataset to simulate real underwater images with different levels of blurring.

- 2)

Improved network structure by introducing two self-attention mechanisms in SuperPoint’s encoder.

- 3)

SuperPoint was originally used for aerial images, and we use an underwater image dataset to retrain the improved network with the ability to extract feature points in underwater blurred images.

The study is organized as follows:

Section 2 discusses the challenges and importance of feature extraction from underwater images;

Section 3 outlines the process of creating a dataset of blurred underwater images;

Section 4 introduces the structure and training process of the network;

Section 5 designs a comparative experiment using two datasets and analyzes the experimental results; finally, a summary of the entire study is provided.

2. Problem Description

The features of an image play a crucial role in enabling computers to accurately comprehend and interpret the image. In the context of underwater visual tasks, the feature points extracted from underwater images provide essential information for subsequent tasks. However, the underwater environment poses various challenges due to light absorption and scattering of suspended particles. These factors result in low contrast, fogging effects, and color distortion, primarily in shades of blue or green. Seriously degraded underwater images lack sufficient information for effective target detection and recognition, making it more challenging to identify targets in underwater environments.

With the development of high-tech underwater optical equipment, the quality of underwater images has improved to a certain extent. However, there are still issues such as color degradation, low contrast, and blurred details. Additionally, the cost of implementing these technologies is also a factor to consider. Underwater image degradation poses a significant obstacle to feature extraction, making it a critical issue for underwater visual applications. Traditional computer vision techniques often encounter challenges when processing underwater images, particularly in extracting unique feature points that can effectively generalize in complex scenes.

As shown in

Figure 1, subgraph (a) shows underwater blurry images. This is due to the influence of water on the propagation of shooting time, resulting in blurry effects in the image. And the absorption of blue and green light by water is relatively small, resulting in a blue-green color in the final image. subgraph (b) shows the effectiveness of existing feature point extraction methods on such images. Due to the low image quality, high-quality feature points cannot be extracted. The concentrated distribution and small number of feature points pose great challenges to subsequent tasks. A network based on self-attention mechanism is proposed in this paper, which enhances the network’s sensitivity to degraded features in underwater images to tackle this issue.

3. Blurred Underwater Image Dataset

The underwater environment presents various unknown conditions, making it challenging to visualize images formed under different levels of water turbidity. Precisely controlling the level of turbidity in water is also difficult. The NTNU dataset [

12] is an underwater image dataset created in an underwater 3D scene model. It includes 3D models such as artificial objects and submarine dunes to enhance environmental complexity. In a synthetic underwater 3D simulation environment, all parameters are controllable, and the geometry data can be accurately represented. A blurred underwater image dataset was created by applying various degrees of blurring operations to the NTNU dataset. Fuzzy processes are based on the Lambert-Beer law as a grounded theory, which applies to all electromagnetic radiation and all light-absorbing substances, including gases, solids, liquids, molecules, atoms, and ions. The generalized light attenuation model is described as in Equation (

1). The model is transferred to an underwater environment as shown in Equation (

2). The blurring pipeline is shown in

Table 1, with Equations (3)–(7) expressing the specific calculation method of the process.

Where

E is the light intensity,

r is the distance, and

c is the medium attenuation coefficient.

where

a is the absorption coefficient,

b is the scattering coefficient, and the sum of

a and

b is equivalent to the total medium attenuation coefficient

c.

where

represents the color attenuation coefficient matrix,

is the color attenuation constant,

is the depth image,

is the scattering coefficient image matrix,

is the original image,

and

represent the gradient magnitude and the standard deviation of the gradient of the original image, respectively.

and

denote the set scattering coefficient constant and the standard deviation of the scattering coefficient image,

r is the reflectance,

is the filter size, and

h is the Gaussian filter with

as the size. Where the subscript

m denotes the image matrix, which is a three-dimensional matrix. The third dimension denotes the color channel. By setting the two parameters

and

, it is possible to obtain underwater images with different blurred levels.

This method utilizes depth information to transform a clear simulation image into underwater images with varying degrees of blur, as depicted in

Figure 2. The dataset of generated blurred images will be used in the feature extraction comparison experiments of this paper.

4. Proposed Method

Underwater images are subject to alterations to the light and characteristics of the medium resulting in blurry, hazy and tinted images [

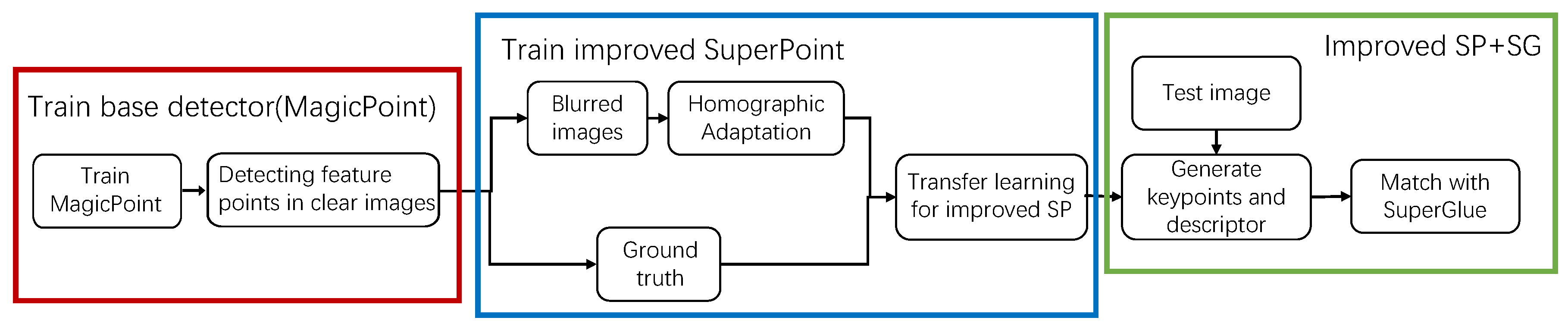

26]. Traditional methods are not suitable for extracting features from them. To address this problem, this paper proposes a self-supervised network based on the self-attention mechanism. This network is an end-to-end learning framework, which means it takes an input image and produces output feature points and descriptors. Transfer learning is performed on the EUVP dataset to learn the ability to extract features from blurred underwater images. The pipeline of the whole system is shown in

Figure 3.

4.1. Architecture

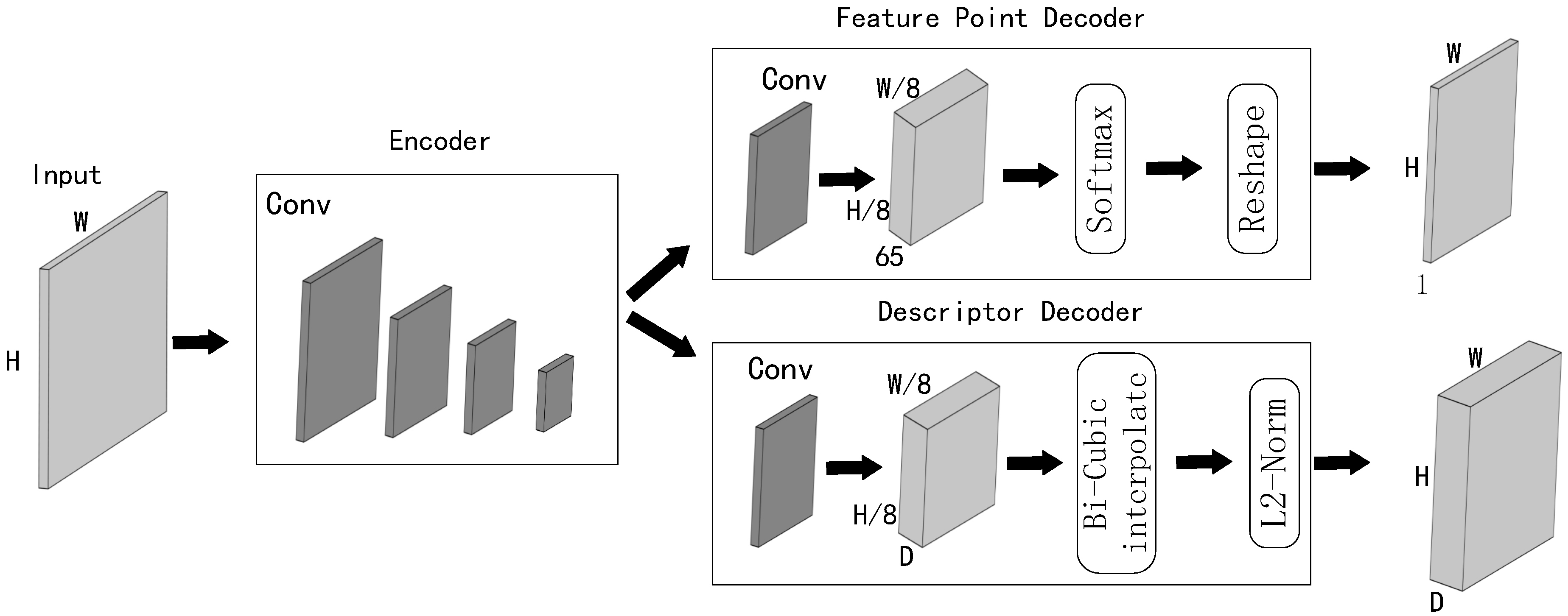

The network proposed in this paper is based on the SuperPoint network [

13] as the infrastructure, which includes a shared encoder, a feature detector, and a descriptor generator. The overall structure is shown in

Figure 4. VGG-style shared encoders are used to reduce the dimensionality of the input image and computational complexity. In the network proposed in this paper, a self-attention mechanism is introduced in the second and fourth layers of the shared encoder. The self-attention mechanism helps reduce reliance on external information and instead focuses more on the internal relevance of features within the image. By utilizing the correlations among local information, the self-attention mechanism effectively captures global feature information, enabling the learning of deeper abstract features in blurred underwater images. Additionally, the input and output sizes of the self-attention mechanism are the same, which facilitates subsequent computations. The network’s shared encoder architecture, depicted in

Figure 5, illustrates the integration of the VGG backbone and the introduced self-attention mechanism. Furthermore,

Figure 6 shows a flowchart that outlines the steps involved in the self-attention mechanism, with

representing a learnable parameter. The specific expression is shown in Equations (8)–(10).

where

x represents the input image;

is a

convolution; and

is the dimension of

K. We compute the dot products of the query with all keys, to prevent the results from being too large, divide each by

, and apply a softmax function to obtain the weights on the values. The final output is obtained by adding the attention output to the original value times

.

4.2. Loss Functions

The loss function of the network is the same as SuperPoint [

13]. It is the sum of two intermediate losses: one for the feature point decoder loss

and one for the descriptor decoder loss

. The final loss is balanced using the parameter

, as shown in Equation (

11).

The loss function

for the feature point decoder is a fully convolutional cross-entropy loss. In this equation,

X and

D represent the feature maps and description subgraphs of the original image, while

Y represents the ground truth of the original image. Additionally,

,

, and

represent the information of the homographic warped image, with the same meaning as mentioned earlier. The specific expression of the feature point decoder loss function is shown in Equation (

12).

where

and

denote the height and width of the feature map of feature points,

and

are the values of

X,

Y at

. The specific expression of

is shown in Equation (

13). Furthermore, k is the number of channels.

Equation (

14) is used to determine whether the center position of an image is similar to the corresponding image after a homographic adaptation. The result is 1 for positive correspondence and otherwise for negative correspondence. Where

represents the position of the center pixel of the corresponding input image, and

represents a homographic adaptation of

.

The loss function of the descriptor decoder is defined as shown in Equation (

15).

where

and

denote the values of

D and

at

and

, respectively. The shared encoder has an 8-fold downsampling operation, so each point in the output descriptor feature map corresponds to an 8 × 8 cell in the input image. The weight term

is introduced to balance the case where there are more negative correspondences than positive correspondences. The thresholds for positive and negative correspondences are represented by

and

, respectively.

4.3. Training Networks

The network proposed in this paper is trained on the EUVP [

15] underwater image dataset using transfer learning. At the same time, the same transfer learning was applied to the original SuperPoint network. In the later experiments, we call the original network after transfer learning as transferred SuperPoint. The EUVP dataset consists of pairs of underwater images, including both blurred and high-quality images. The dataset encompasses various visibility conditions and locations, providing a diverse range of natural scene variations. In this paper, a subset of the underwater scene image dataset is used. It consists of 2,185 pairs for training and 130 pairs for validation, totaling 4,500 images.

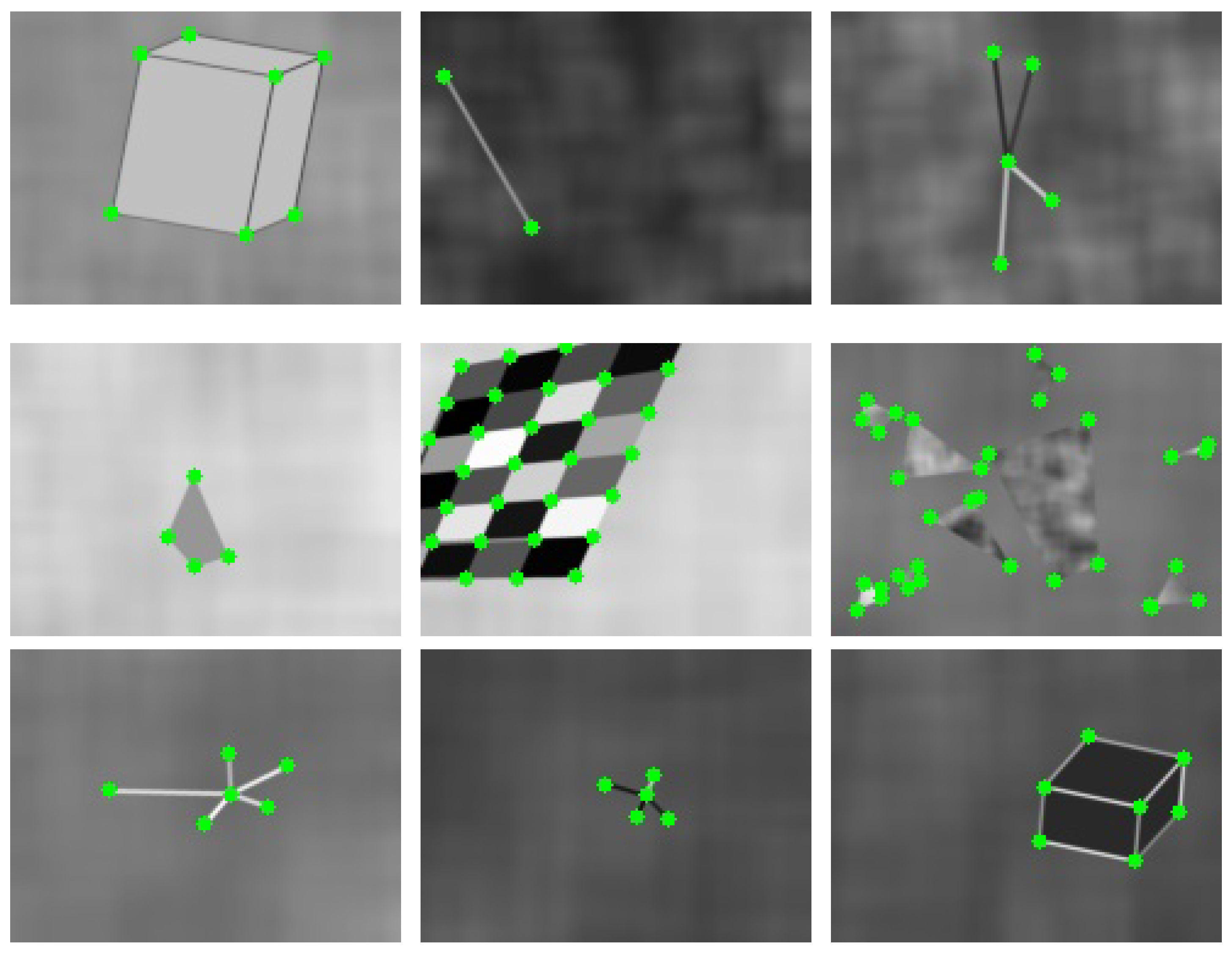

The network is trained using self-supervised learning, and the training process is as follows. (1) The MagicPoint [

14] network, which consists of a shared encoder and a feature point decoder, is the base network of SuperPoint and is trained on synthetic image datasets. The synthetic dataset contains simple geometric figures, such as straight lines, Y-shaped lines, triangles, and other easily identifiable features. Some example images from this dataset are shown in

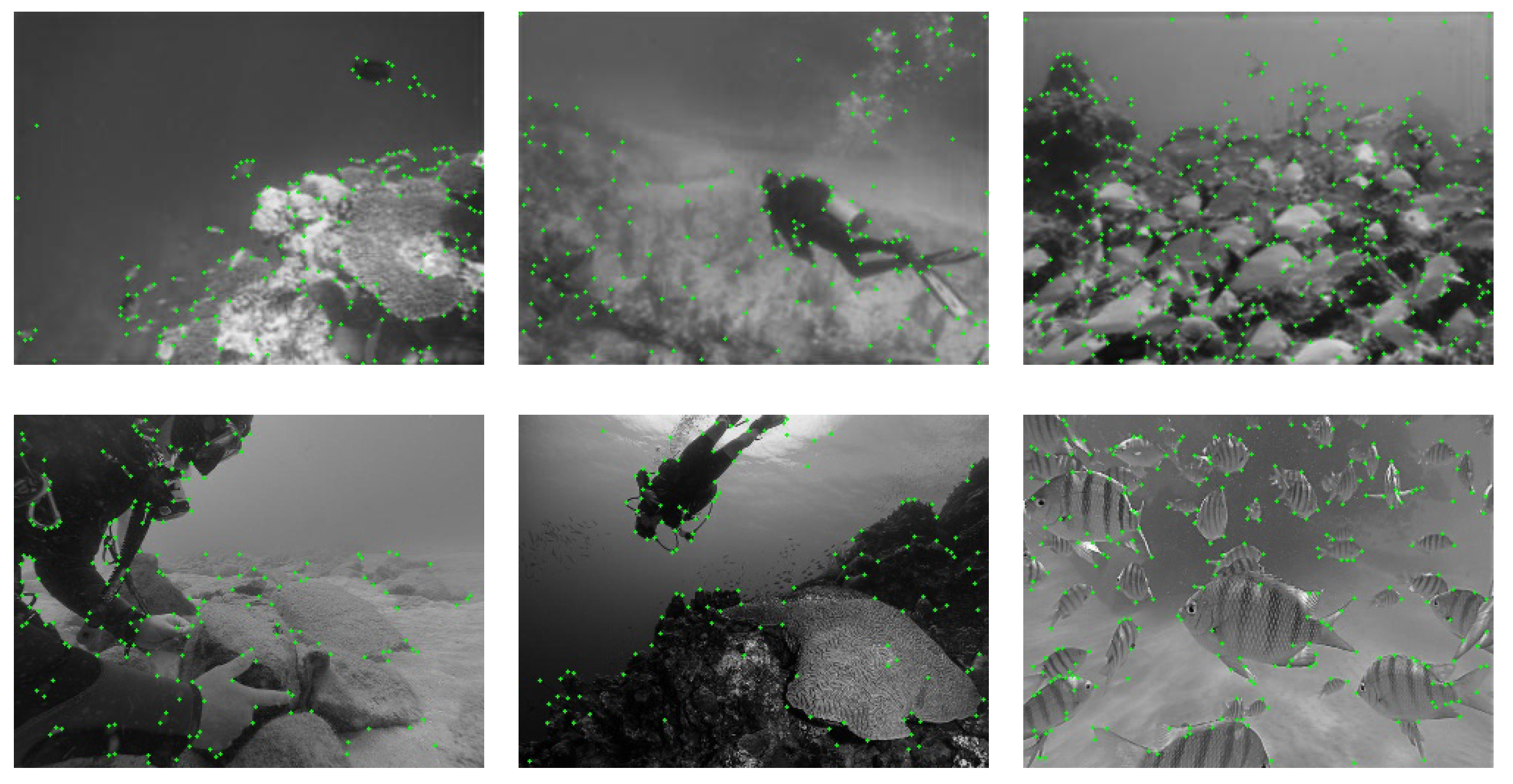

Figure 7. (2) The MagicPoint network is used to extract feature points from high-quality images of the EUVP dataset, and the resulting feature points are considered as the ground truth. This annotation process involves subjecting the input image to N iterations of homographic adaptation. The feature points on the warped image are detected for each homographic warp. After applying the inverse homographic adaptation, the feature points from all N homographic adaptations are pooled back onto the original image to ensure an adequate number of feature points are extracted. In this paper, N is set to 50. The result of the MagicPoint in extracting feature points from the training dataset is shown in

Figure 8. (3) The network is trained on the annotated dataset obtained in the second step. The network learns to generate feature points and descriptors based on the input images and the ground truth provided by the MagicPoint network.

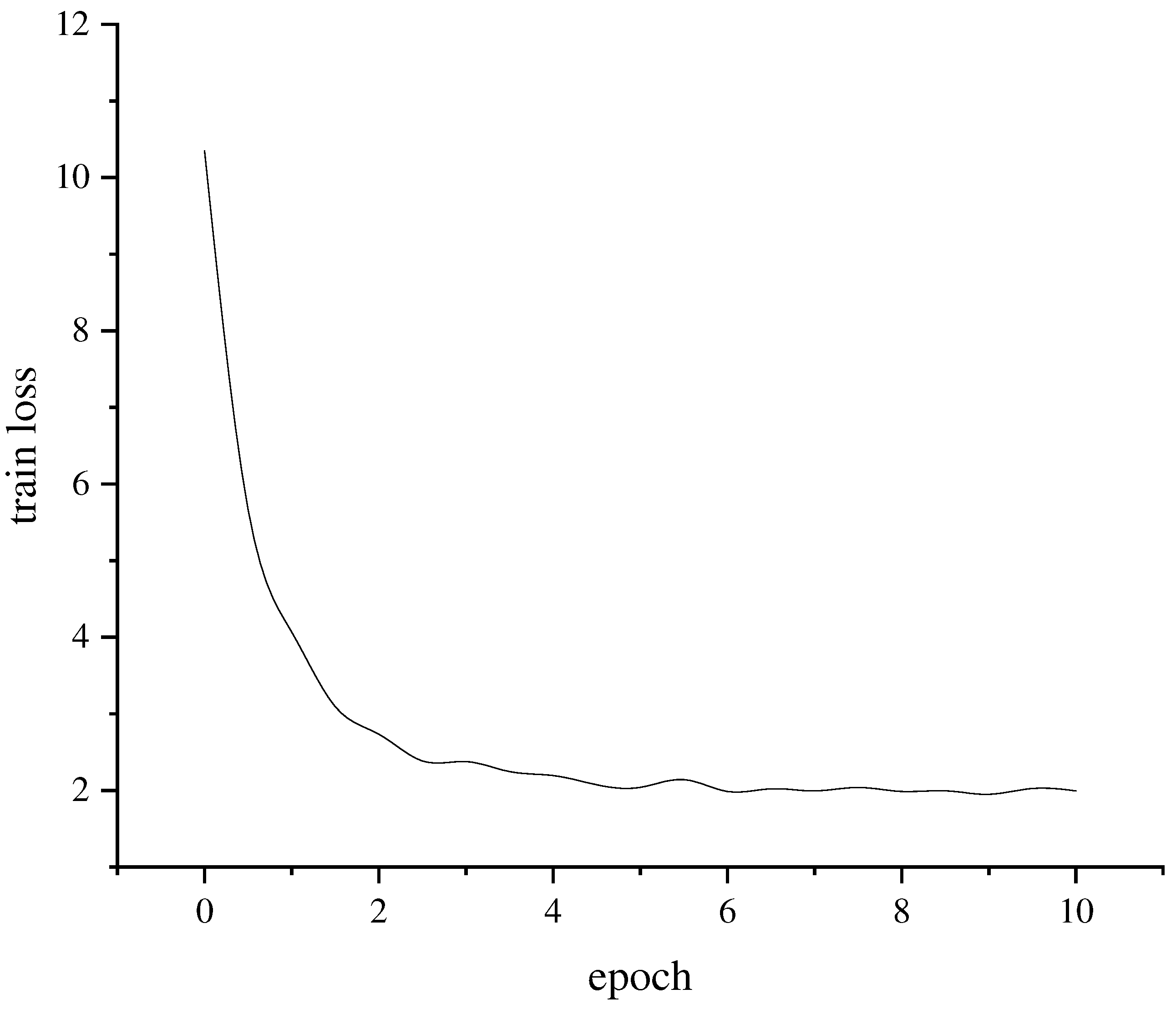

During training, the initial learning rate is set to 0.001, and the dropout rate in the self-attention mechanism is 0.4. The loss function values of the training over ten epochs are depicted in

Figure 9. It can be observed that the loss function value of the improved network model converges to approximately two after ten training iterations, indicating a good fit for the trained network.

5. Experiments

To assess the performance of the network proposed in this paper in extracting features from blurred underwater images, comparative experiments were conducted with ORB, SIFT, the original SuperPoint, and the transferred SuperPoint. Two underwater image datasets containing blurred images were selected for experimental testing. The first dataset was created by blurring the NTNU dataset. Three representative groups of images were selected, and the degree of blurring for each group was divided into five levels, ranging from 1 to 5, to indicate increasing levels of blurring intensity. The second dataset used for testing was the RUIE dataset. Objective evaluations were based on several metrics, including the number of extracted features and matches, as well as inference efficiency.

5.1. Comparison Experiment of Blurred NTNU Dataset

In the underwater environment, where the conditions are relatively mild, optical images have higher clarity, and the objects in the images are more distinct. Therefore, an image with a blur level of 1 was chosen for the comparison experiments. This level of blurring represents a clear underwater image, allowing for a more focused evaluation of the feature extraction performance of the different methods.

In

Figure 10, the results of feature extraction using various algorithms are shown for three images with a blur level of 1. All three images are tested in the subsequent experiments, and their respective blur levels are indicated separately. The network proposed in this paper shows a more uniform distribution of feature points extracted from the three underwater images. It can extract more feature points from images with a single scene. On the other hand, the original SuperPoint network extracts a large number of feature points in the background of image A that are not easily interpretable from a human perception perspective. The feature points extracted by the transferred SuperPoint also exhibit better uniformity, but their quantity is lower compared to those extracted by the network proposed in this paper. The feature points extracted by the ORB and SIFT algorithms lack uniformity, which can negatively impact tasks such as visual SLAM.

To assess the effectiveness of the extracted feature points, they were matched with the corresponding feature points in adjacent frame images. The handcrafted feature points were matched using FLANN [

18], while the feature points extracted by SuperPoint and the algorithms proposed in this paper were matched using SuperGlue [

16].

Figure 11 shows the matching results of various algorithms on the underwater images with blur level 1 and their adjacent frames. The number of feature points extracted by each algorithm and the number of matches are tabulated in

Table 2.

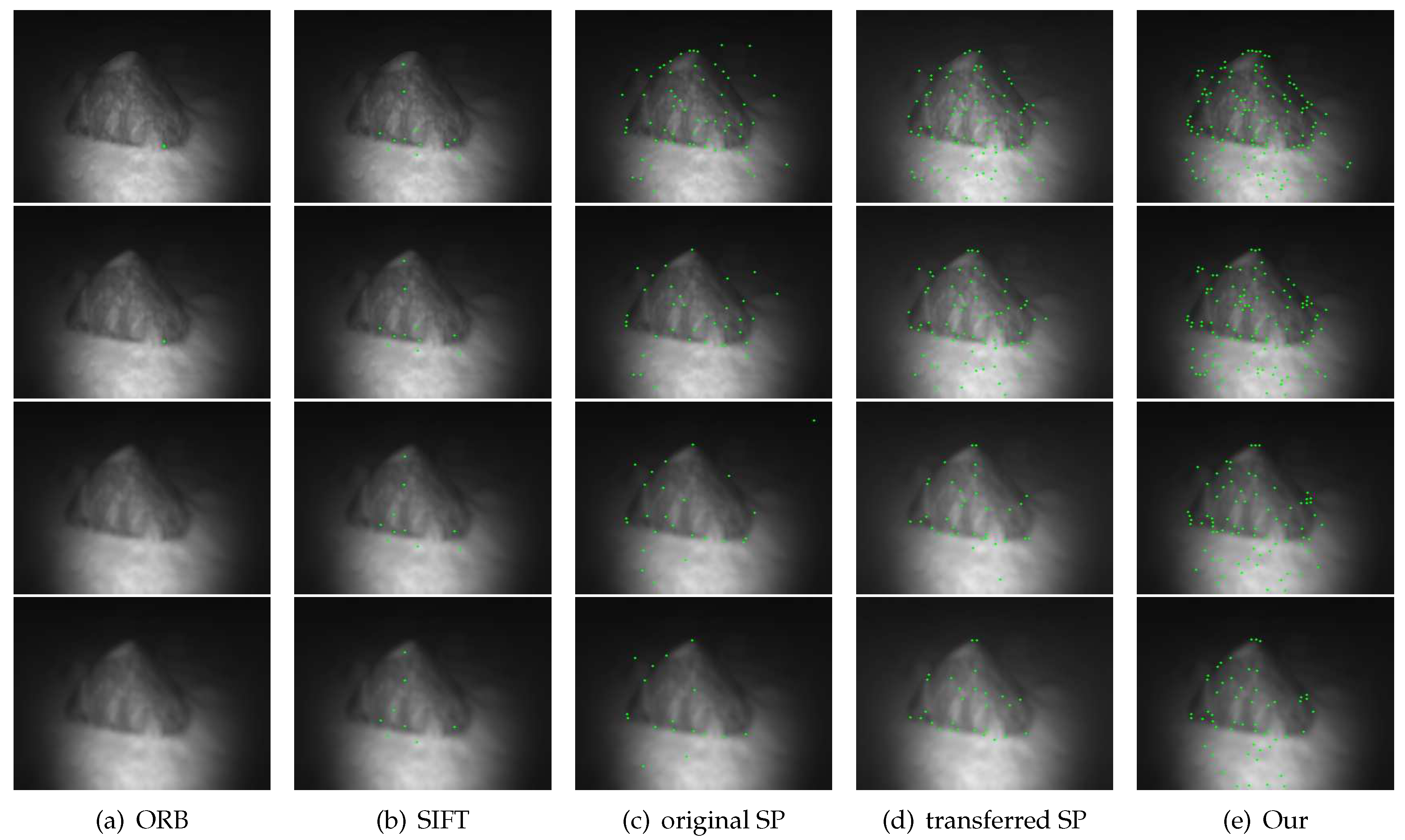

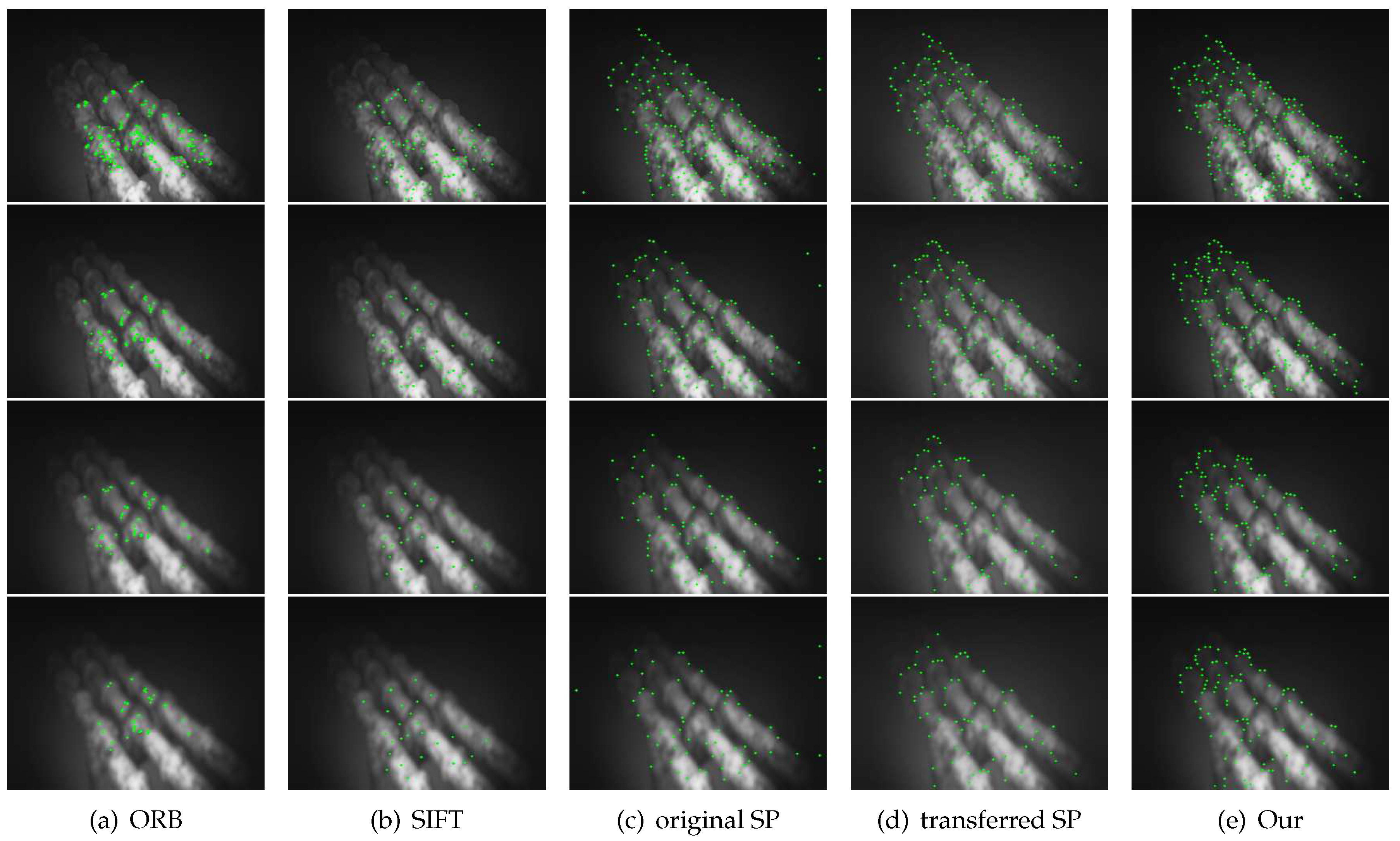

In order to account for the complex and diverse underwater environment, images B and C with blur levels 2 to 5 were used as examples. These images were simulated under various turbidity conditions in water, and comparative experiments of feature extraction were conducted using ORB, SIFT, SuperPoint, and the network proposed in this study. The aim was to evaluate the performance of these algorithms in extracting features from underwater images with varying levels of blur.

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 show the results of various algorithms in extracting feature points on image B and image C, respectively, with different levels of blur. Image B, with its blurred textures and simple scene, becomes increasingly challenging for traditional methods as the level of blur intensifies. On the other hand, image C exhibits more textured features on the objects, enabling various methods to extract a large number of feature points. However, the feature points extracted by ORB and SIFT lack uniformity. In contrast, both SuperPoint and the algorithm proposed in this paper detect feature points more uniformly. Furthermore, the network proposed in this paper extracts a significantly greater number of effective feature points compared to both the original network and the transferred SuperPoint.

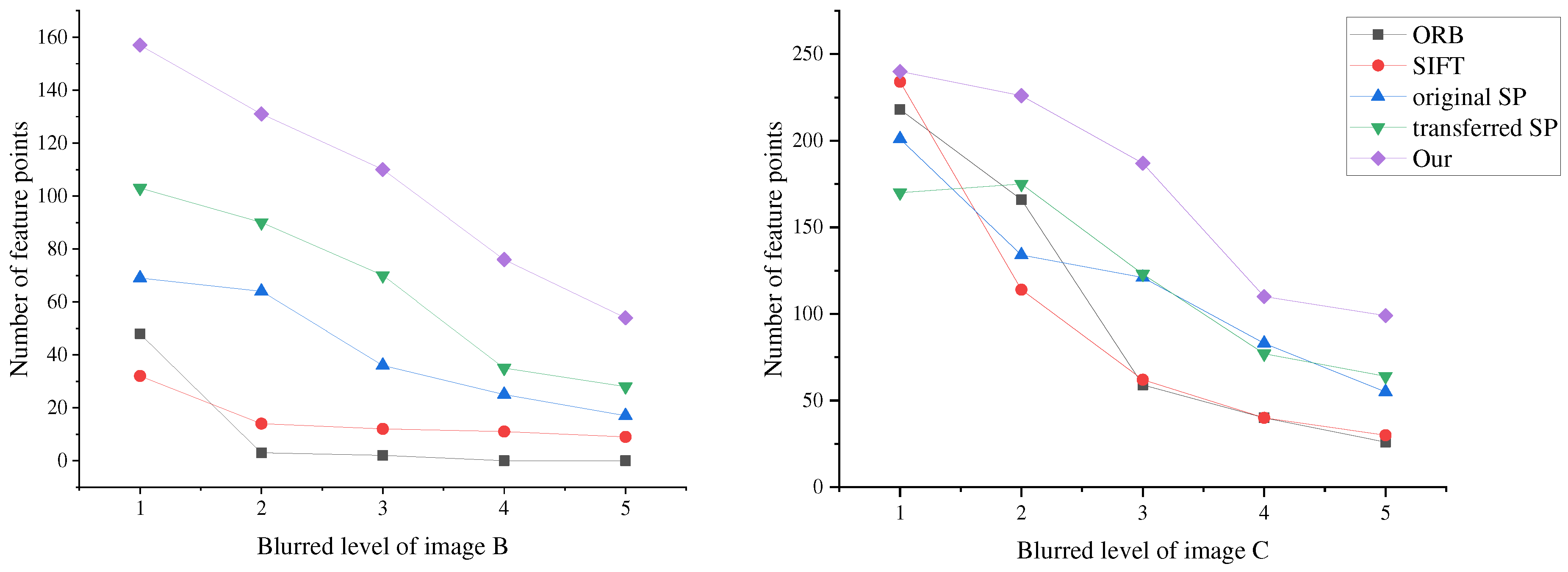

Figure 14 shows the change in the number of feature points extracted by the different algorithms as the blur level gradually increases. Notably, the network proposed in this paper exhibits the slowest decrease in the number of feature points and is capable of extracting feature points that meet specific requirements, even in images with a blur level of 5.

5.2. Comparison Experiment of REIU Dataset

To assess the performance of the proposed network on real-world underwater images, a comparative experiment was conducted using the RUIE dataset. This dataset comprises real underwater images captured near Roe Deer Island in the Yellow Sea, with scene depths ranging from 0.5 m to 8 m. The water depth, influenced by periodic tides, varies between 5 m and 9 m. These environmental conditions lead to underwater images with diverse color tones and varying levels of quality. This experiment utilized two subsets of the RUIE dataset: the Underwater Image Quality Set (UIQS) and the Underwater Color Cast Set (UCCS). The Underwater Color Image Quality Evaluation (UCIQE) metric [

17] is a linear combination of chromaticity, saturation, and contrast in underwater images. The UIQS subset is divided into five subsets (A, B, C, D, E) based on the descending order of UCIQE values. Examples of different image quality levels from subsets A to E are shown in

Figure A1. In the subset from A to E, the image quality progressively decreases. The UCCS is divided into subsets based on the average value of the blue channel in the CIELAB color space. The subsets include blue, green, and blue-green hues. Examples of images from these subsets are shown in

Figure A2.

The performance of the network proposed in this paper is compared with other algorithms for feature extraction on two subsets: UIQS and UCCS. In

Figure 15, the extraction results of different algorithms from the UIQS dataset are shown. The first row of images represents subset A, and the second row represents subset B, and so on, with the last row representing subset E. The SIFT and ORB algorithms can extract a few feature points in subsets A and B. However, these feature points tend to be concentrated in local areas of the images, and their distribution is not uniform. As the blur level increases, the SIFT and ORB algorithms fail to extract enough feature points. The original SuperPoint network can only extract a limited number of feature points from blurred images. The transferred SuperPoint is able to extract uniformly distributed feature points on all images, but not as many as the proposed network. However, the proposed network extracted a significantly higher number of stable feature points from all blurred images. It is also less susceptible to image blurring and can directly extract feature points from images without the need for pre-processing. This comparison demonstrates the superior performance of the proposed network in accurately and robustly extracting feature points from blurred images.

Figure 16 shows the results of feature extraction by various algorithms from underwater images in different tones. The first row represents the green images, the second row represents the blue-green images, and the third row represents the blue images. The results indicate that the proposed network can extract a larger number of high-quality feature points from all images, regardless of their tones. In contrast, the ORB and SIFT algorithms extract fewer feature points from the blue-green and green images and exhibit the drawback of uneven distribution of feature points on the blue image. The original SuperPoint and the transferred SuperPoint can extract fewer feature points from images with all three tones. This comparison highlights the superior performance of the network proposed in this paper. It is capable of extracting a larger number of high-quality feature points across different tones in underwater images, providing a more comprehensive and accurate representation of the image features.

Table 3 provides statistical information on various algorithms regarding the number of features extracted and inference efficiency on different types of images. The ORB demonstrates higher efficiency in feature extraction. SIFT extracts more feature points, but only on clear images. However, both ORB and SIFT exhibit diminishing performance as the blur level increases and are sensitive to changes in image hue. The original network and transferred network extract a small number of feature points across all images. In contrast, the improved network shows a slower decline in its ability to extract feature points as the degree of image blurring increases. Furthermore, it exhibits robust characteristics regarding interference resistance and insensitivity to changes in hue. Notably, the proposed network is capable of extracting 195 feature points even from highly blurred images. Furthermore, the inference frame rate remains steady at approximately 28 frames per second when processing images that contain 300 feature points. The criterion for calculating FPS is by calculating the time used by the program to process each image, which was run on a GPU of model 3090Ti.

The experimental results support the conclusion that the network proposed in this paper performs better in processing low-quality underwater images. It can address challenges such as low image contrast, fogging blur, and color deviation commonly encountered in underwater environments. The network’s robustness is demonstrated by its ability to extract stable and effective feature points, thus overcoming the limitations of traditional methods and the original SuperPoint structure.

6. Conclusions

A feature extraction network is introduced to address common challenges in underwater images, including color distortion and object blurring. The proposed method incorporates two self-attention mechanisms within the shared encoder module of the network. The goal is to improve the accuracy of feature extraction, especially for blurred underwater images. The underwater image dataset is used to improve the performance of feature extraction in the network by employing transfer learning. Experimental results demonstrate significant advantages of the proposed algorithm over traditional methods and the SuperPoint network in terms of both the quantity and quality of extracted feature points. The proposed network demonstrates adaptability to different levels of image degradation, making it suitable for effectively handling various degrees of degradation in underwater images. It provides an effective solution for extracting features from blurred underwater images. Its advancements hold promising implications for enhancing performance and expanding applications in underwater visual tasks, particularly in the field of visual SLAM in underwater environments.

Author Contributions

Writing—review and editing , project administration and funding acquisition, D.W.; methodology, software, and writing—original draft preparation, B.S.; Conceptualization and validation, L.H., L.Z. and Y.W.; resources, Z.Y.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 51909044.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Example diagram of Underwater Image Quality Set.

Figure A1.

Example diagram of Underwater Image Quality Set.

Figure A2.

Example diagram of Underwater Color Cast Set.

Figure A2.

Example diagram of Underwater Color Cast Set.

References

- Ghosh S, Ray R, V.S.R.K.S.S.N.N.S. Reliable pose estimation of underwater dock using single camera: A scene invariant approach. Machine Vision and Applications 2016, 27:221-236. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, F.; Bräunl, T. Evaluation of Several Feature Detectors/Extractors on Underwater Images towards vSLAM. Sensors 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. International journal of computer vision 2004, 60, 91–110. [CrossRef]

- Rublee, E.; Rabaud, V.; Konolige, K.; Bradski, G. ORB: An efficient alternative to SIFT or SURF. In Proceedings of the 2011 International conference on computer vision. Ieee, 2011, pp. 2564–2571.

- Barroso-Laguna, A.; Riba, E.; Ponsa, D.; Mikolajczyk, K. Key. net: Keypoint detection by handcrafted and learned cnn filters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 5836–5844.

- Mahmood, A.; Bennamoun, M.; An, S.; Sohel, F.; Boussaid, F. ResFeats: Residual network based features for underwater image classification. Image and Vision Computing 2020, 93, 103811. [CrossRef]

- Yi, K.M.; Trulls, E.; Lepetit, V.; Fua, P. LIFT: Learned Invariant Feature Transform. Computer Vision–ECCV 2016 2016, pp. 467–483.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z. A deep CNN method for underwater image enhancement. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP). IEEE, 2017, pp. 1382–1386.

- Arif, M.H. A Novel Feature Extraction Model to Enhance Underwater Image Classification. Intelligent Computing Systems 2020, p. 78.

- Yang, J.; Gong, M.; Nair, G.; Lee, J.H.; Monty, J.; Pu, Y. Knowledge Distillation for Feature Extraction in Underwater VSLAM. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.17981 2023.

- Liu, R.; Fan, X.; Zhu, M.; Hou, M.; Luo, Z. Real-world underwater enhancement: Challenges, benchmarks, and solutions under natural light. IEEE transactions on circuits and systems for video technology 2020, 30, 4861–4875.

- Zwilgmeyer, P.G.O.; Yip, M.; Teigen, A.L.; Mester, R.; Stahl, A. The varos synthetic underwater data set: Towards realistic multi-sensor underwater data with ground truth. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 3722–3730.

- DeTone, D.; Malisiewicz, T.; Rabinovich, A. Superpoint: Self-supervised interest point detection and description. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 2018, pp. 224–236.

- DeTone, D.; Malisiewicz, T.; Rabinovich, A. Toward geometric deep slam. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.07410 2017.

- Islam, M.J.; Xia, Y.; Sattar, J. Fast underwater image enhancement for improved visual perception. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2020, 5, 3227–3234. [CrossRef]

- Sarlin, P.E.; DeTone, D.; Malisiewicz, T.; Rabinovich, A. Superglue: Learning feature matching with graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 4938–4947.

- Yang, M.; Sowmya, A. An underwater color image quality evaluation metric. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2015, 24, 6062–6071. [CrossRef]

- Muja, M.; Lowe, D.G. Fast approximate nearest neighbors with automatic algorithm configuration. VISAPP (1) 2009, 2, 2.

- Bay, H.; Ess, A.; Tuytelaars, T.; Van Gool, L. Speeded-up robust features (SURF). Computer vision and image understanding 2008, 110, 346–359.

- Alcantarilla, P.; Bartoli, A.; Davison, A. KAZE Features. Computer Vision–ECCV 2012 2012, pp. 214–227. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, Q.; Yu, W.; Wang, B. SRP-AKAZE: An improved accelerated KAZE algorithm based on sparse random projection. IET Computer Vision 2020, 14, 131–137.

- Chen, P.H.; Luo, Z.X.; Huang, Z.K.; Yang, C.; Chen, K.W. IF-Net: An illumination-invariant feature network. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2020, pp. 8630–8636.

- Noh, H.; Araujo, A.; Sim, J.; Weyand, T.; Han, B. Large-scale image retrieval with attentive deep local features. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 3456–3465.

- Dusmanu, M.; Rocco, I.; Pajdla, T.; Pollefeys, M.; Sivic, J.; Torii, A.; Sattler, T. D2-Net: A Trainable CNN for Joint Detection and Description of Local Features. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2019-IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2019.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Iqbal K, Salam R A, O.A.T.A.Z. Underwater Image Enhancement Using an Integrated Colour Model. IAENG International Journal of computer science 2007, 34(2).

- Kanakis, M.; Maurer, S.; Spallanzani, M.; Chhatkuli, A.; Van Gool, L. ZippyPoint: Fast Interest Point Detection, Description, and Matching through Mixed Precision Discretization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 6113–6122.

Figure 1.

Problems in processing underwater images.

Figure 1.

Problems in processing underwater images.

Figure 2.

Different degrees of blur effect.

Figure 2.

Different degrees of blur effect.

Figure 3.

Pipeline of the whole system

Figure 3.

Pipeline of the whole system

Figure 4.

Feature extraction network architecture.

Figure 4.

Feature extraction network architecture.

Figure 5.

Feature extraction network shared encoder.

Figure 5.

Feature extraction network shared encoder.

Figure 6.

Self-attention mechanism flow chart.

Figure 6.

Self-attention mechanism flow chart.

Figure 7.

Example of a synthetic dataset image

Figure 7.

Example of a synthetic dataset image

Figure 8.

MagicPoint extracts the ground truth of the training data set.

Figure 8.

MagicPoint extracts the ground truth of the training data set.

Figure 9.

The loss function curve of the feature extraction network.

Figure 9.

The loss function curve of the feature extraction network.

Figure 10.

The result of feature point extraction by various algorithms on image B with different degrees of blurring.

Figure 10.

The result of feature point extraction by various algorithms on image B with different degrees of blurring.

Figure 11.

The result of feature point extraction by various algorithms on image C with different degrees of blurring.

Figure 11.

The result of feature point extraction by various algorithms on image C with different degrees of blurring.

Figure 12.

Number of feature points extracted by different algorithms on different images with different blurred levels.

Figure 12.

Number of feature points extracted by different algorithms on different images with different blurred levels.

Figure 13.

The result of feature extraction on different images by various algorithms.

Figure 13.

The result of feature extraction on different images by various algorithms.

Figure 14.

The matching result of feature points extracted by each type of algorithm.

Figure 14.

The matching result of feature points extracted by each type of algorithm.

Figure 15.

Feature extraction results of various algorithms on underwater images with different degrees of blurring.

Figure 15.

Feature extraction results of various algorithms on underwater images with different degrees of blurring.

Figure 16.

Feature extraction results of various algorithms on underwater images with different hues.

Figure 16.

Feature extraction results of various algorithms on underwater images with different hues.

Table 1.

Fuzzification process.

Table 1.

Fuzzification process.

| set parameters |

| 1: calculate the color decay coefficient image |

| 2: calculate the scattering coefficient image: |

| 3: calculate the raw gradient and standard deviation |

| 4: calculate and normalize the scattering image |

| 5: add Gaussian white noise |

| 6: calculate reflectance |

| 7: perform Gaussian filtering |

| 8: crop the image |

Table 2.

Number of feature points and matching pairs on level 1 blurred images for each type of algorithm.

Table 2.

Number of feature points and matching pairs on level 1 blurred images for each type of algorithm.

| Method |

Image A |

Image B |

Image C |

| |

|

Points |

Matching |

Points |

Matching |

Points |

Matching |

|

| ORB+FLANN |

83 |

59 |

48 |

16 |

218 |

120 |

| SIFT+FLANN |

28 |

24 |

32 |

18 |

234 |

189 |

| original SP+SuperGlue |

56 |

44 |

69 |

46 |

201 |

105 |

| transferred SP+SuperGlue |

33 |

29 |

100 |

73 |

160 |

124 |

| Our+SuperGlue |

65 |

61 |

157 |

100 |

240 |

179 |

Table 3.

The number of feature points extracted by different algorithms on different images and the inference time.

Table 3.

The number of feature points extracted by different algorithms on different images and the inference time.

| Image |

ORB |

SIFT |

Original SP |

Transferred SP |

Our |

| |

|

Points |

FPS |

Points |

FPS |

Points |

FPS |

Points |

FPS |

Points |

FPS |

| A |

452 |

245 |

719 |

42.6 |

143 |

37 |

282 |

40.1 |

386 |

25.5 |

| B |

116 |

574 |

93 |

56 |

95 |

39.5 |

224 |

38.5 |

343 |

27.7 |

| C |

0 |

844 |

5 |

57.8 |

55 |

38.7 |

210 |

38.5 |

308 |

28.6 |

| D |

0 |

\ |

5 |

51.1 |

40 |

39.4 |

160 |

38.2 |

241 |

28.7 |

| E |

0 |

\ |

0 |

\ |

38 |

39.4 |

125 |

42.5 |

195 |

28.9 |

| green |

72 |

624 |

62 |

48 |

84 |

37.6 |

233 |

42.4 |

323 |

25.9 |

| blue-green |

20 |

743 |

31 |

50.3 |

93 |

38.2 |

225 |

41.3 |

308 |

28 |

| blue |

297 |

320 |

269 |

57.9 |

92 |

37.3 |

240 |

40.9 |

323 |

26.6 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).