Submitted:

27 September 2023

Posted:

28 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

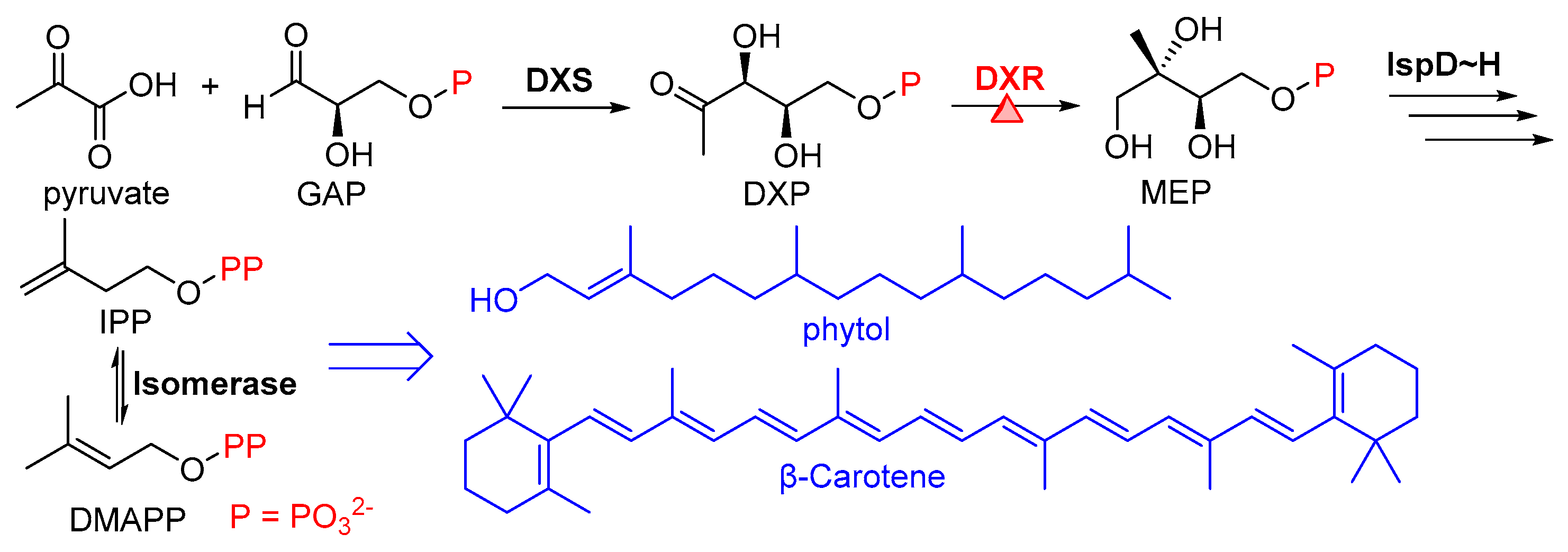

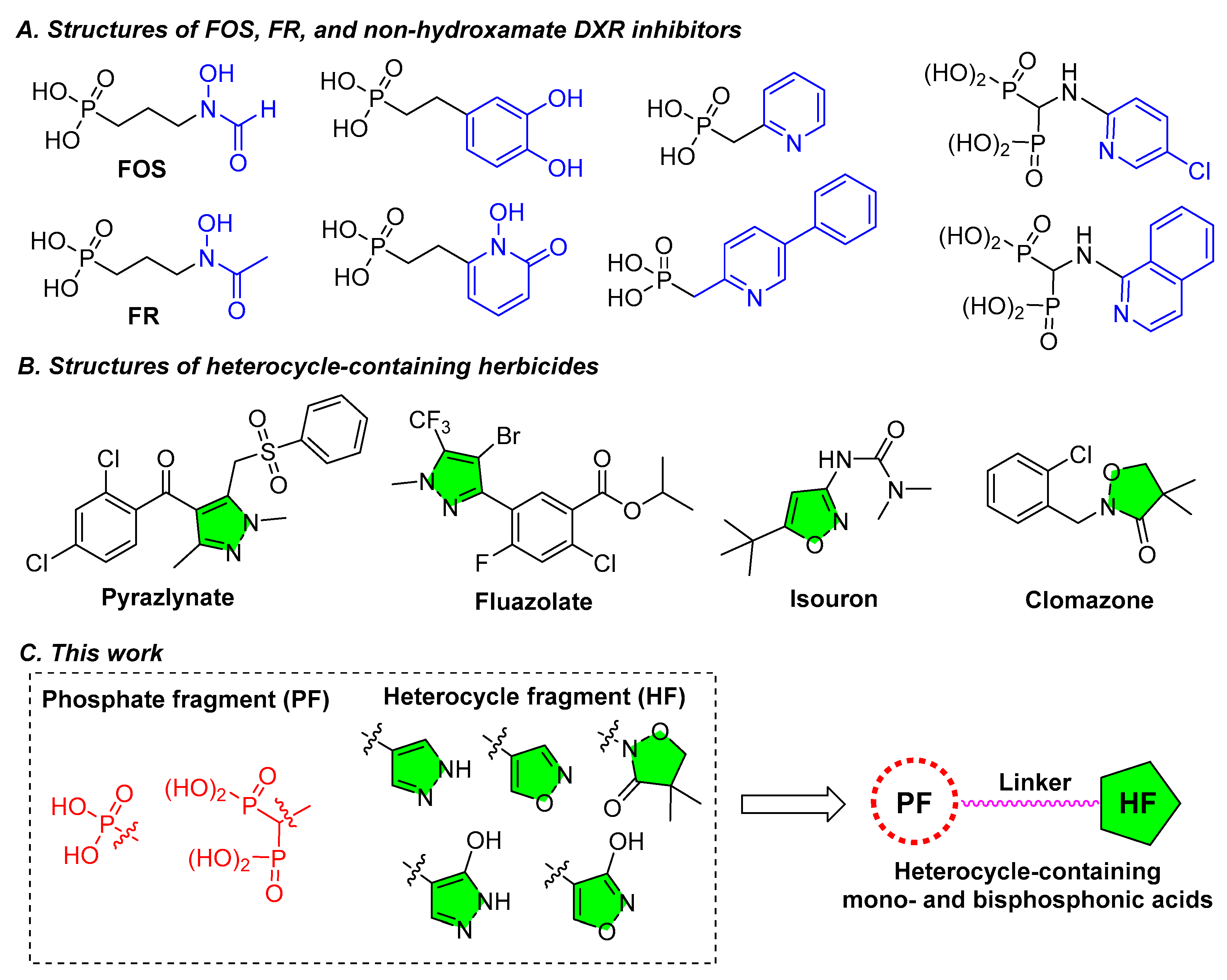

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

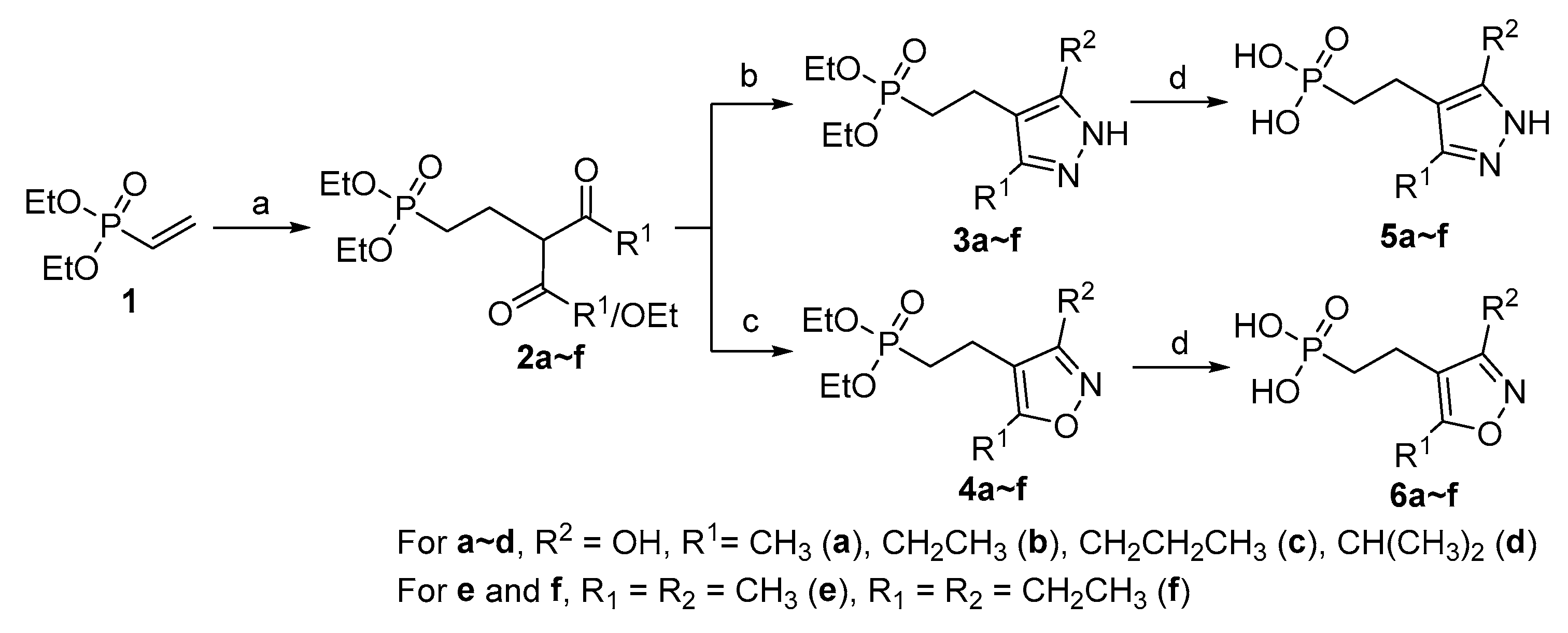

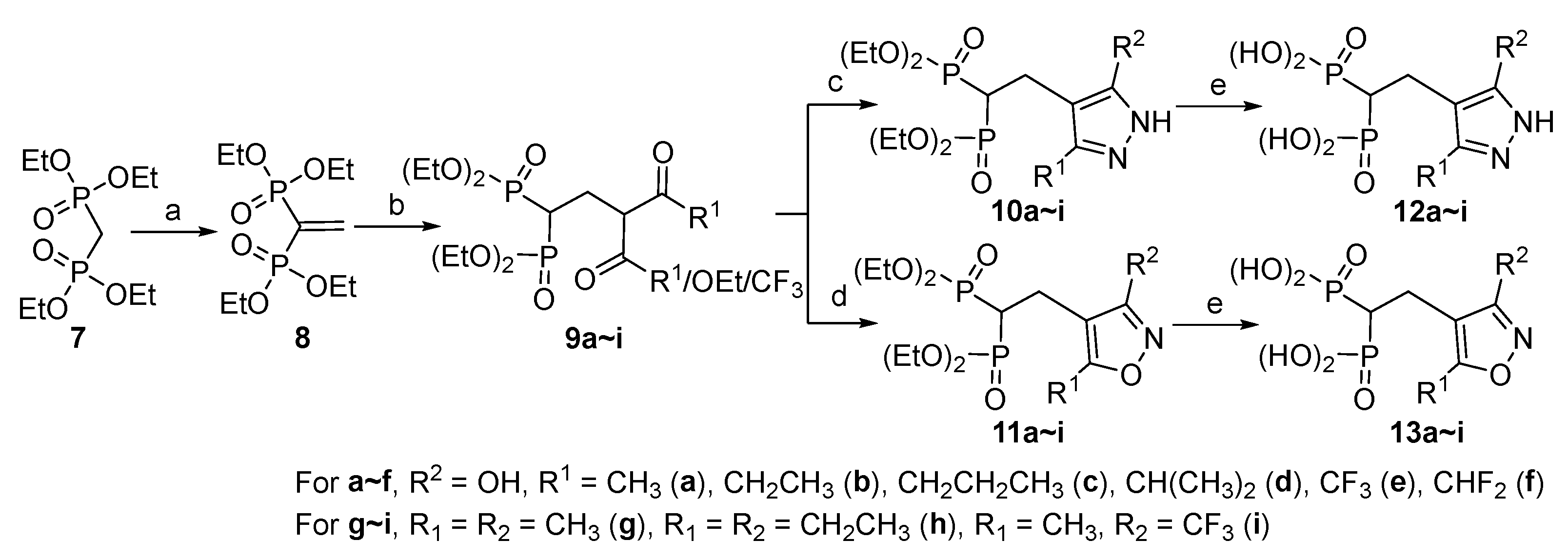

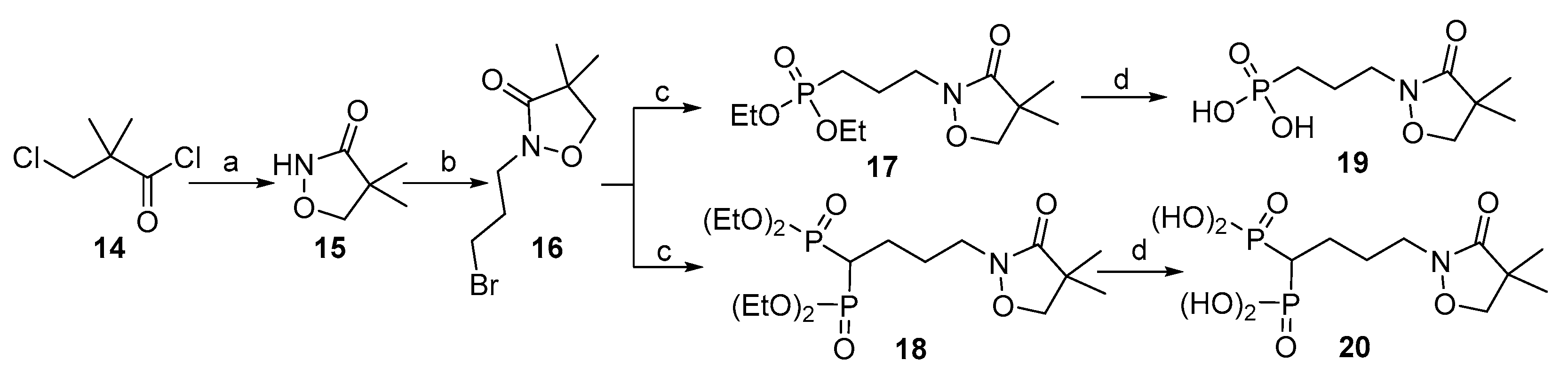

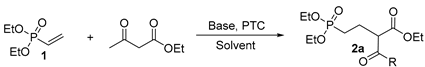

2.1. Chemistry

| Entry | Base | PTC | Solvent | Temp (℃) | Yield (%)b |

| 1 | t-BuOK | -- | THF | r.t. | 60 |

| 2 | NaH | -- | THF | r.t. | 45 |

| 3 | NaOEt | -- | EtOH | r.t. | 40 |

| 4 | t-BuOK | -- | THF | 66 | 62 |

| 5 | Cs2CO3 | TBAI | CH3CN | 80 | 80 |

| 6 | Cs2CO3 | TEBAC | CH3CN | 80 | 85 |

| 7 | K2CO3 | TBAI | CH3CN | 80 | 83 |

| 8 | K2CO3 | TEBAC | CH3CN | 80 | 90 |

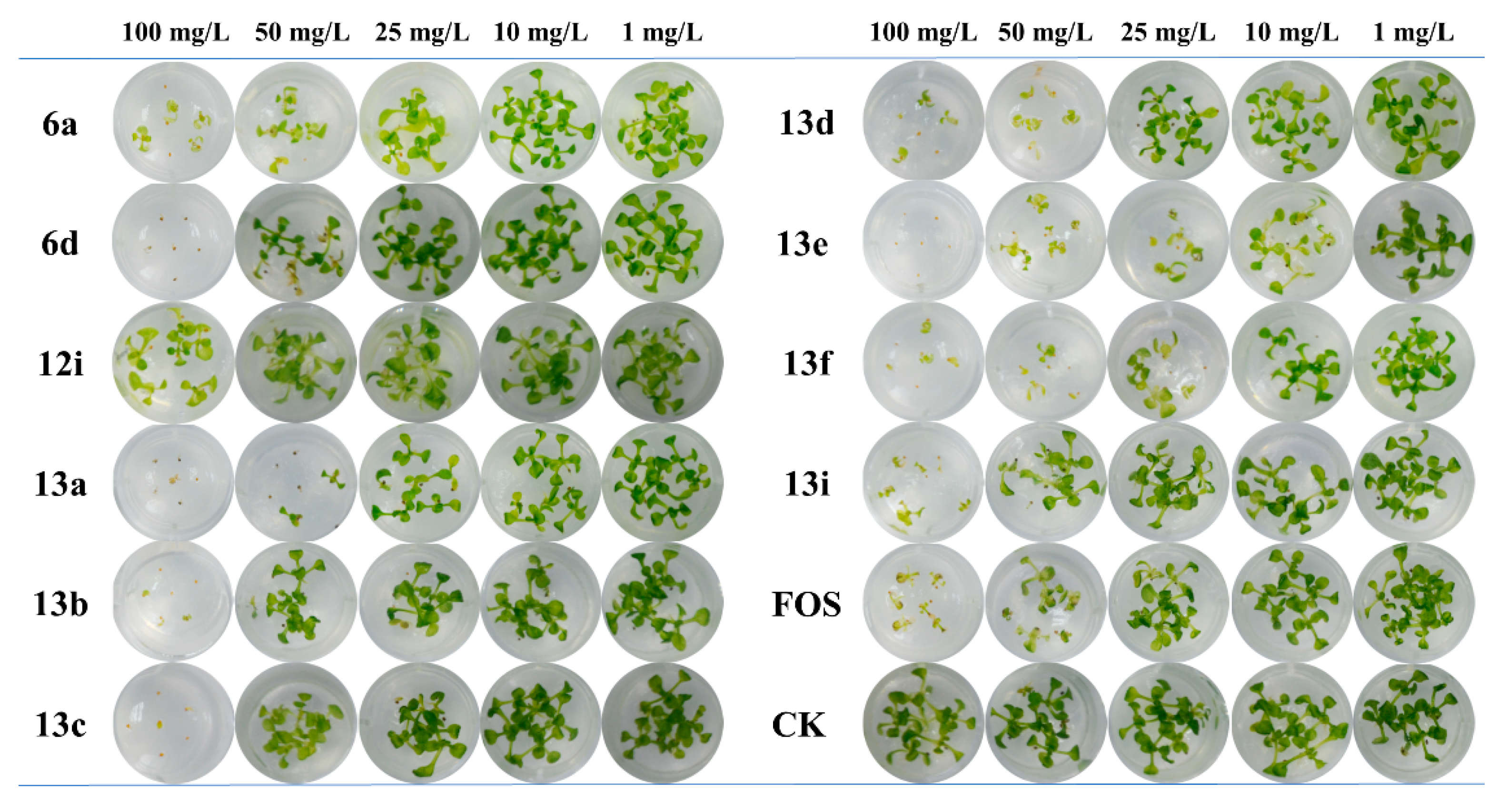

2.2. Arabidopsis Growth Inhibitory Activity

| Comp | EC50 (mg/L)a | Comp | EC50 (mg/L) | Comp | EC50 (mg/L) |

| 5a | >100 | 6f | >100 | 13b | 37.7±2.8 |

| 5b | >100 | 12a | >100 | 13c | 48.4±5.3 |

| 5c | >100 | 12b | >100 | 13d | 23.1±1.9 |

| 5d | >100 | 12c | >100 | 13e | 7.8±1.2 |

| 5e | >100 | 12d | >100 | 13f | 8.7±1.3 |

| 5f | >100 | 12e | >100 | 13g | >100 |

| 6a | 28.6±3.9 | 12f | >100 | 13h | >100 |

| 6b | >100 | 12g | >100 | 13i | 40.7±2.9 |

| 6c | >100 | 12h | >100 | 19 | >100 |

| 6d | 45.7±4.8 | 12i | 88.3±4.3 | 20 | >100 |

| 6e | >100 | 13a | 21.6±3.8 | FOS | 27.5±3.1 |

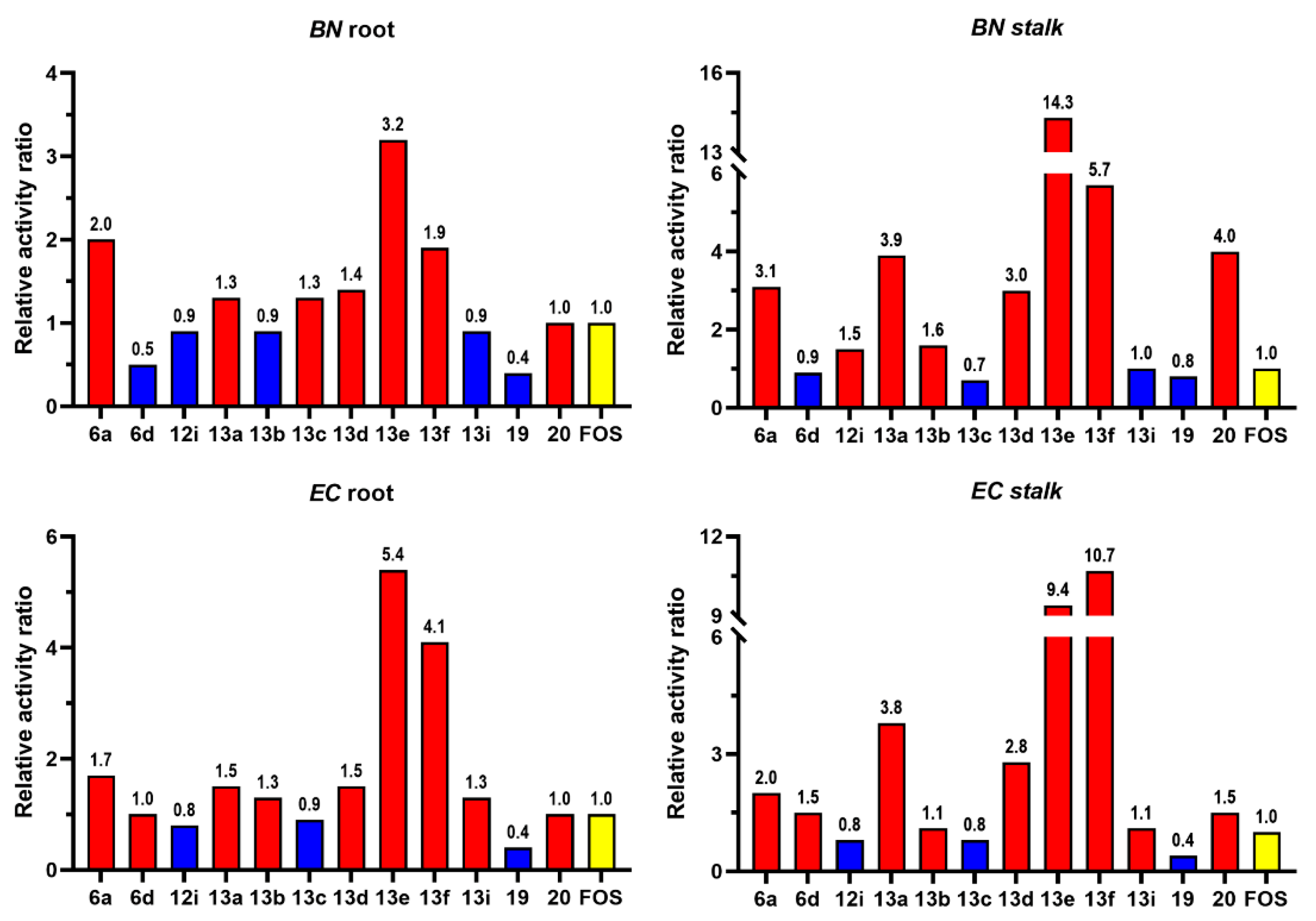

2.3. Pre-emergence Herbicidal Activity

| Comp | EC50 (mg/L) | |||

| BN | EC | |||

| root | stalk | root | stalk | |

| 6a | 17.3 | 10.5 | 24.0 | 18.9 |

| 6d | 67.5 | 38.2 | 40.1 | 25.7 |

| 12i | 36.6 | 21.7 | 53.1 | 47.7 |

| 13a | 26.9 | 8.5 | 27.1 | 10.2 |

| 13b | 38.8 | 20.2 | 29.9 | 35.3 |

| 13c | 27.7 | 46.9 | 43.9 | 45.8 |

| 13d | 25.2 | 11.0 | 27.2 | 13.5 |

| 13e | 10.7 | 2.3 | 7.4 | 4.1 |

| 13f | 17.9 | 5.8 | 9.7 | 3.6 |

| 13i | 40.5 | 33.5 | 32.1 | 34.6 |

| 19 | 79.3 | 39.2 | >100 | 88.0 |

| 20 | 34.6 | 8.2 | 40.0 | 25.2 |

| FOS | 34.7 | 32.9 | 40.2 | 38.4 |

2.4. Post-emergence Herbicidal Activity

| Comp | Visual evaluationb | Loss of weight (%) | ||

| AR | EC | AR | EC | |

| 6a | + | + | 35.6 | 30.8 |

| 13a | ++ | + | 52.3 | 35.8 |

| 13d | ++ | + | 45.7 | 34.9 |

| 13e | +++ | ++ | 70.3 | 53.5 |

| 13f | +++ | ++ | 61.8 | 48.1 |

| 20 | + | + | 23.6 | 22.9 |

| FOS | + | + | 31.5 | 27.4 |

2.5. DXR Inhibitory Activity

| Comp | InR (%)a | Comp | InR (%) | Comp | InR (%) |

| 5a | 11.9 | 6f | 11.7 | 13b | 27.4 |

| 5b | 12.9 | 12a | 13.7 | 13c | 28.4 |

| 5c | 6.1 | 12b | 21.9 | 13d | 14.0 |

| 5d | 17.7 | 12c | 32.3 | 13e | 54.9 |

| 5e | 23.0 | 12d | 12.4 | 13f | 24.4 |

| 5f | 32.4 | 12e | 22.8 | 13g | 7.3 |

| 6a | 15.8 | 12f | 6.1 | 13h | 10.3 |

| 6b | 19.5 | 12g | 11.6 | 13i | 30.3 |

| 6c | 7.5 | 12h | 2.3 | 19 | 22.5 |

| 6d | 17.3 | 12i | 27.1 | 20 | 29.5 |

| 6e | 12.1 | 13a | 60.2 | FOS | 98.7 |

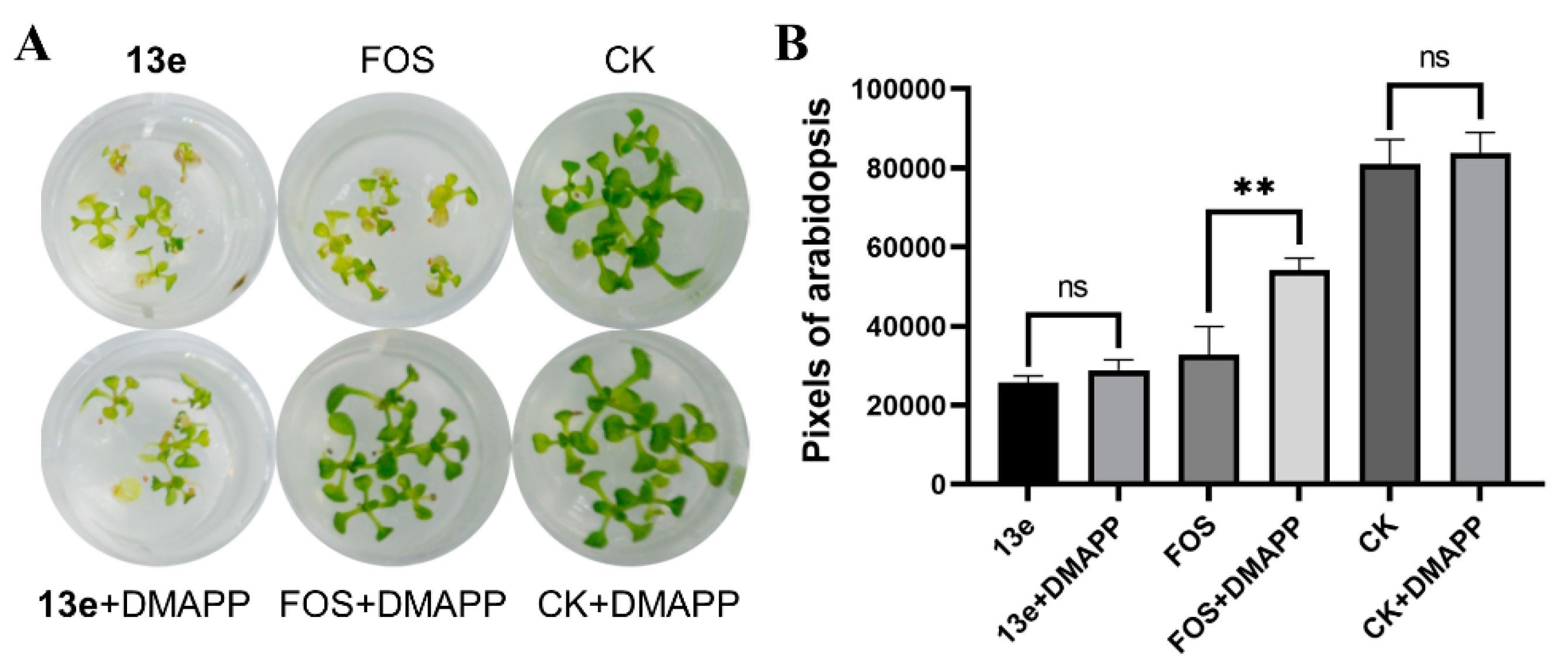

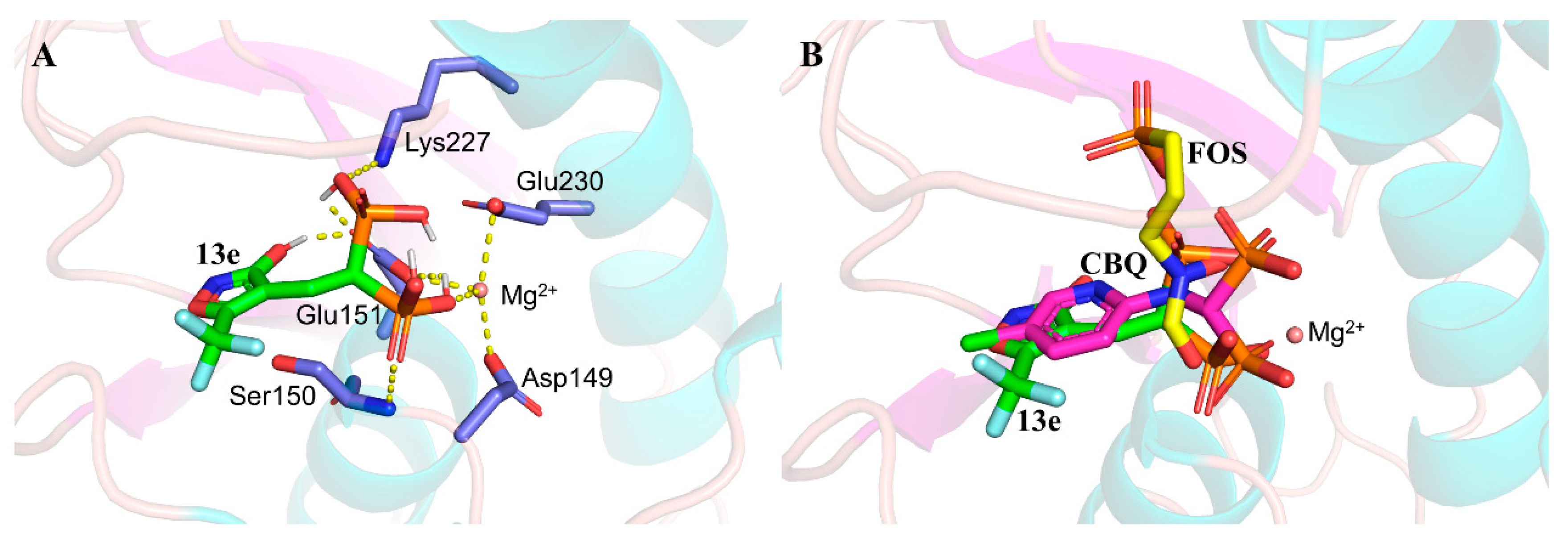

2.6. DMAPP Rescue and Molecule Docking

2.7. Discussion on Structure-Activity Relationships

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Instruments and Reagents

3.2. Synthesis

3.3. Biological Assays

3.3.1. Arabidopsis Growth Inhibition Assay

3.3.2. Pre-Emergence Herbicidal Inhibition Assay

3.3.3. Post-Emergence Herbicidal Inhibition Assay

3.3.4. DXR Enzyme Inhibition Assay

3.3.5. DMAPP Rescue

3.4. Molecular Docking

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frank, A.; Groll, M. The methylerythritol phosphate pathway to isoprenoids. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 5675–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Chang, W.C.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, H.W.; Liu, P. Methylerythritol phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 497–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, T.; Kroezen, B.S.; Hirsch, A.K. Druggability of the enzymes of the non-mevalonate-pathway. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Dong, X.; Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Liu, L. An Update on the function and regulation of methylerythritol phosphate and mevalonate pathways and their evolutionary dynamics. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 1211–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranová, E.; Coman, D.; Gruissem, W. Network analysis of the MVA and MEP pathways for isoprenoid synthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 665–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeffler, J.F.; Tritsch, D.; Grosdemange-Billiard, C.; Rohmer, M. Isoprenoid biosynthesis via the methylerythritol phosphate pathway. Mechanistic investigations of the 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 4446–4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppisch, A.T.; Fox, D.T.; Blagg, B.S.J.; Poulter, C.D. E. E. Coli MEP synthase: steady-state kinetic analysis and substrate binding. Biochemistry 2001, 41, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajima, S.; Hara, K.; Iino, D.; Sasaki, Y.; Kuzuyama, T.; Ohsawa, K.; Seto, H. Structure of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase in a quaternary complex with a magnesium ion, NADPH and the antimalarial drug fosmidomycin. Acta Crystallogr. F. 2007, 63, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Zeidler, J.; Schwender, J.; Müller, C. The non-mevalonate isoprenoid biosynthesis of plants as a test system for new herbicides and drugs against pathogenic bacteria and the malaria parasite. Z. Naturforsch. C. 2000, 55, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possell, M.; Ryan, A.; Vickers, C.E.; Mullineaux, P.M.; Hewitt, C.N. Effects of fosmidomycin on plant photosynthesis as measured by gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence. Photosynth. Res. 2010, 104, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuhara, M.; Kuroda, Y.; Goto, T.; Okamoto, M.; Terano, H.; Kohsaka, M.; Aoki, H.; Imanaka, H. Studies on new phosphonic acid antibiotics. III. Isolation and characterization of FR-31564, FR-32863 and FR-33289. J. Antibiot. 1980, 33, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuhara, M.; Kuroda, Y.; Goto, T.; Okamoto, M.; Terano, H.; Kohsaka, M.; Aoki, H.; Imanaka, H. Studies on new phosphonic acid antibiotics. I. FR-900098, isolation and characterization. J. Antibiot. 1980, 33, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, T.; Hirsch, A.K.H. Development of inhibitors of the 2C-Methyl-D-erythritol 4-Phosphate (MEP) pathway enzymes as potential anti-infective agents. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9740–9763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesharwani, S.; Sundriyal, S. Non-hydroxamate inhibitors of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR): A critical review and future perspective. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 213, 113055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knak, T.; Abdullaziz, M.A.; Höfmann, S.; Alves Avelar, L.A.; Klein, S.; Martin, M.; Fischer, M.; Tanaka, N.; Kurz, T. Over 40 years of fosmidomycin drug research: A comprehensive review and future opportunities. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Kozikowski, A.P. Why hydroxamates may not Be the best histone deacetylase inhibitors-what some may have forgotten or would rather forget? ChemMedChem 2015, 11, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermant, P.; Bosc, D.; Piveteau, C.; Gealageas, R.; Lam, B.; Ronco, C.; Roignant, M.; Tolojanahary, H.; Jean, L.; Renard, P.Y.; Lemdani, M.; Bourotte, M.; Herledan, A.; Bedart, C.; Biela, A.; Leroux, F.; Deprez, B.; Deprez-Poulain, R. Controlling plasma stability of hydroxamic acids: a MedChem toolbox. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 9067–9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, J.J.; Li, X.; Chou, C.J. Advances and challenges of HDAC inhibitors in cancer therapeutics. Adv. Cancer Res. 2018, 138, 183–211. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.M. A bioinorganic approach to fragment-based drug discovery targeting metalloenzymes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2007–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.Y.; Adamek, R.N.; Dick, B.L.; Credille, C.V.; Morrison, C.N.; Cohen, S.M. Targeting metalloenzymes for therapeutic intervention. Chem. Rev. 2018, 119, 1323–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaloussi, M.; Lindh, M.; Björkelid, C.; Suresh, S.; Wieckowska, A.; Iyer, H.; Karlén, A.; Larhed, M. Substitution of the phosphonic acid and hydroxamic acid functionalities of the DXR inhibitor FR900098: an attempt to improve the activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 5403–5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Endo, K.; Kato, M.; Cheng, G.; Yajima, S.; Song, Y. Structures of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase/lipophilic phosphonate complexes. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 2, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajima, S.; Hara, K.; Sanders, J.M.; Yin, F.; Ohsawa, K.; Wiesner, J.; Jomaa, H.; Oldfield, E. Crystallographic structures of two bisphosphonate: 1-deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 10824–10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Sundriyal, S.; Rubio, V.; Shi, Z.Z.; Song, Y. Coordination chemistry based approach to lipophilic inhibitors of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6539–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamberth, C. Heterocyclic chemistry in crop protection. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2013, 69, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C.; Schwender, J.; Zeidler, J.; Lichtenthaler, H.K. Properties and inhibition of the first two enzymes of the non-mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis. Biochem. Soc. T. 2000, 28, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Su, Y.; Yan, Y.H.; Peng, J.Y.; Dai, Q.Q.; Ning, X.L.; Zhu, C.L.; Fu, C.; McDonough, M.A.; Schofield, C.J.; Huang, C.; Li, G.B. MeLAD: an integrated resource for metalloenzyme-ligand associations. Bioinformatics 2019, 36, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmaja, A.; Reddy, G.S.; Venkata Nagendra Mohan, A.; Padmavathi, V. Michael adducts-source for biologically potent heterocycles. Chem. Pharm. Bul. 2008, 56, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulman Page, P.C.; Moore, J.P.; Mansfield, I.; McKenzie, M.J.; Bowler, W.B.; Gallagher, J.A. Synthesis of bone-targeted oestrogenic compounds for the inhibition of bone resorption. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 1837–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang J.H. Herbicidal 3-isoxazolidinones and hydroxamic acids. US 4405357, 1983-09-20.

- Adeyemi, C.M.; Faridoon; Isaacs, M. ; Mnkandhla, D.; Hoppe, H.C.; Krause, R.W.M.; Kaye, P.T. Synthesis and antimalarial activity of N-benzylated (N-arylcarbamoyl)alkyl-phosphonic acid derivatives. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 6131–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chofor, R.; Risseeuw, M.; Pouyez, J.; Johny, C.; Wouters, J.; Dowd, C.; Couch, R.; Van Calenbergh, S. Synthetic fosmidomycin analogues with altered chelating moieties do not inhibit 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase or Plasmodium falciparum growth in vitro. Molecules 2014, 19, 2571–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enders, D.; Wahl, H.; Papadopoulos, K. Asymmetric Michael additions via SAMP/RAMP hydrazones enantioselective synthesis of 2-substituted 4-oxophosphonates. Liebigs Ann. 1995, 7, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Malla, R.K.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Spilling, C.D.; Dupureur, C.M. Synthesis and kinetic analysis of some phosphonate analogs of cyclophostin as inhibitors of human acetylcholinesterase. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 2265–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lolli, M.L.; Lazzarato, L.; Di Stilo, A.; Fruttero, R.; Gasco, A. Michael addition of Grignard reagents to tetraethyl ethenylidenebisphosphonate. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 650, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, A.; Hasaninejad, A.; Parhami, A.; Zare, A.R.M.; Khalafi Nezhad, A. Microwave-assisted michael addition of amides to alpha, beta-unsaturated esters under solvent-free conditions. Pol. J. Chem. 2008, 82, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Sauret-Güeto, S.; Botella-Pavía, P.; Flores-Pérez, U.; Martínez-García, J.F.; San Román, C.; León, P.; Boronat, A.; Rodríguez-Concepción, M. Plastid cues posttranscriptionally regulate the accumulation of key enzymes of the methylerythritol phosphate pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Duan, L.; Duan, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, A. Synthesis and evaluation of halogenated 5-(2-Hydroxyphenyl)pyrazoles as pseudilin analogues targeting the enzyme IspD in the methylerythritol phosphate pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 3071–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.E.; Yang, D.; Huo, J.; Chen, L.; Kang, Z.; Mao, J.; Zhang, J. Design, synthesis, and herbicidal activity of thioether containing 1,2,4-triazole schiff bases as transketolase inhibitors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 11773–11780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, L.; Trisch, D.; Grosdemange-Billiard, C.; Hemmerlin, A.; Willem, A.; Bach, T.; Rohmer, M. Isoprenoid biosynthesis as a target for antibacterial and antiparasitic drugs: phosphonohydroxamic acids as inhibitors of deoxyxylulose phosphate reducto-isomerase. Biochem J. 2005, 386, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ping, H.; Song, C.; Duan, J.; Zhang, A. Optimization synthesis of phosphorous-containing natural products fosmidomycin and FR900098. Phosphorus Sulfur. 2023, 198, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, M.G.; Leroux, J.; Stubbs, K.A.; Mylne, J.S. Herbicidal properties of antimalarial drugs. Sci Rep-UK. 2017, 7, 45871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).