Submitted:

14 September 2023

Posted:

20 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

| Primers | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| hVEGF | 5′-GTCGGGCCTCCGAAACCATG-3′ | 5′-CCTGGTGAGAGATCTGGTTC-3′ |

| hBcl2 | 5′-CTGGAGAGTGCTGAAGATTGATG-3′ | 5′-CAATCACGCGGAACACTTGATTC-3′ |

| hMcl1 | 5′-GATCAGTATATACACTTCAG-3′ | 5′-CAGGTGCAGCCTGTACTTGTC-3′ |

| hβ-actin | 5′-GCCCTGGACTTCGAGCAAGA-3′ | 5′-TGCCAGGGTACATGGTGGTG-3′ |

Results

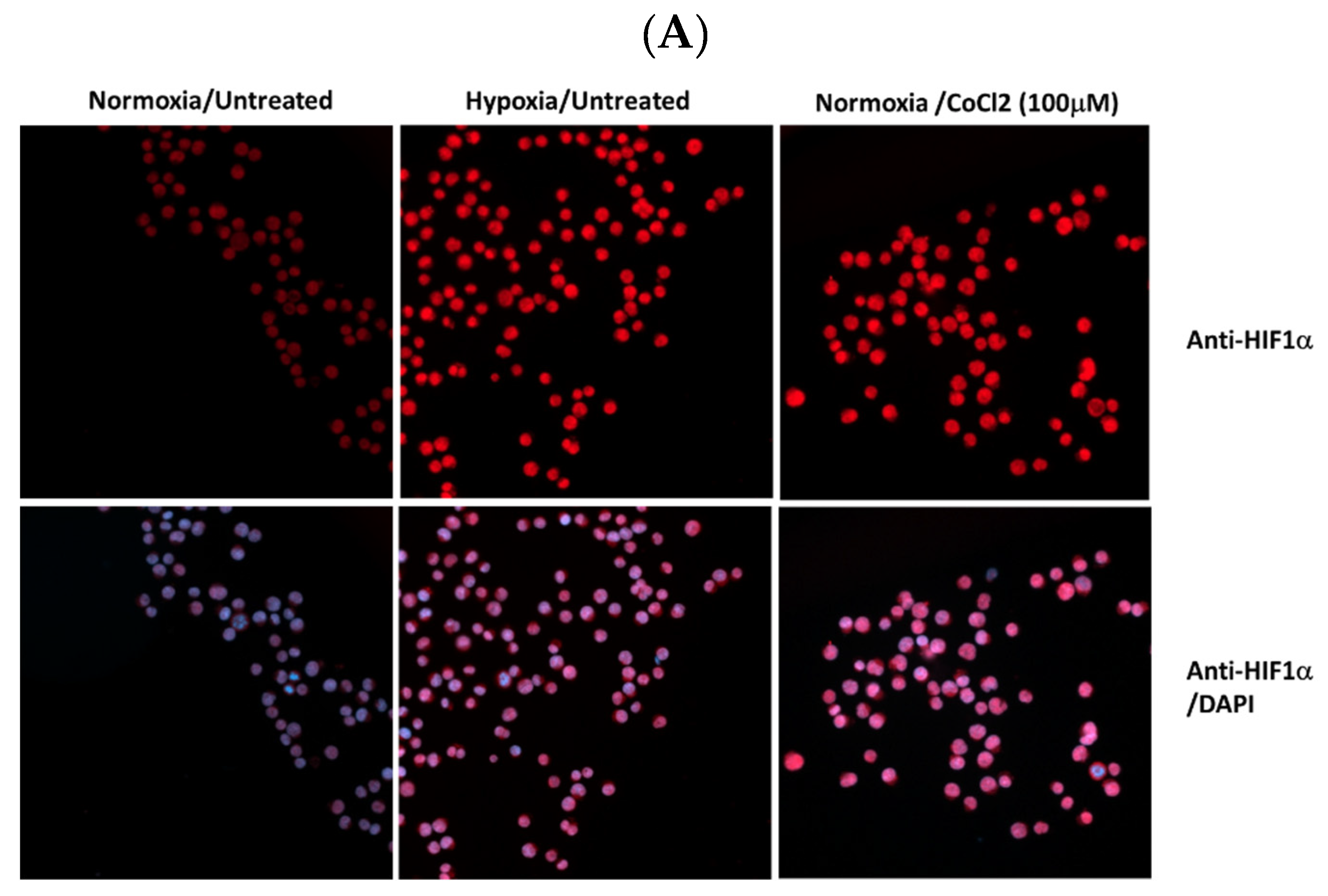

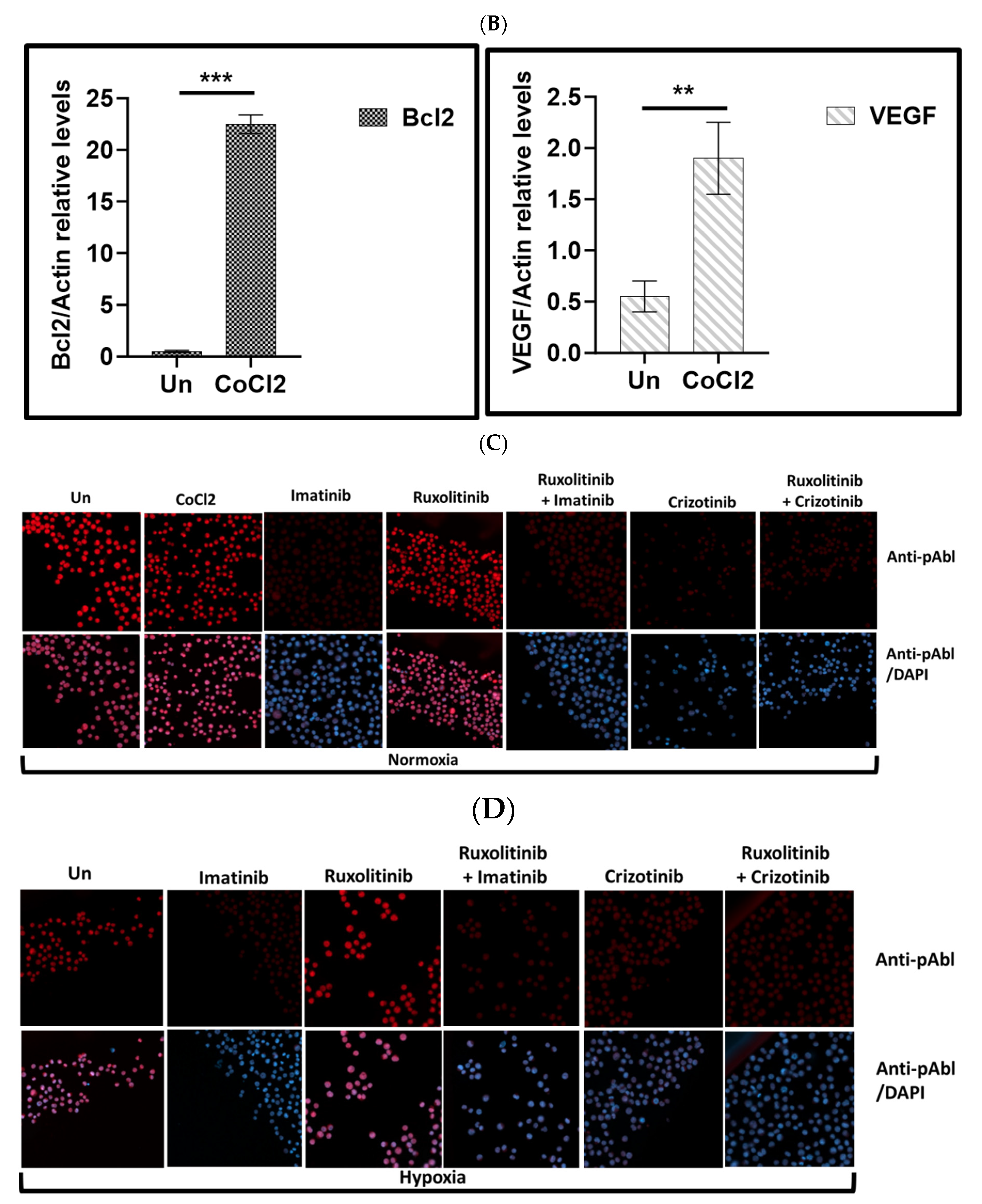

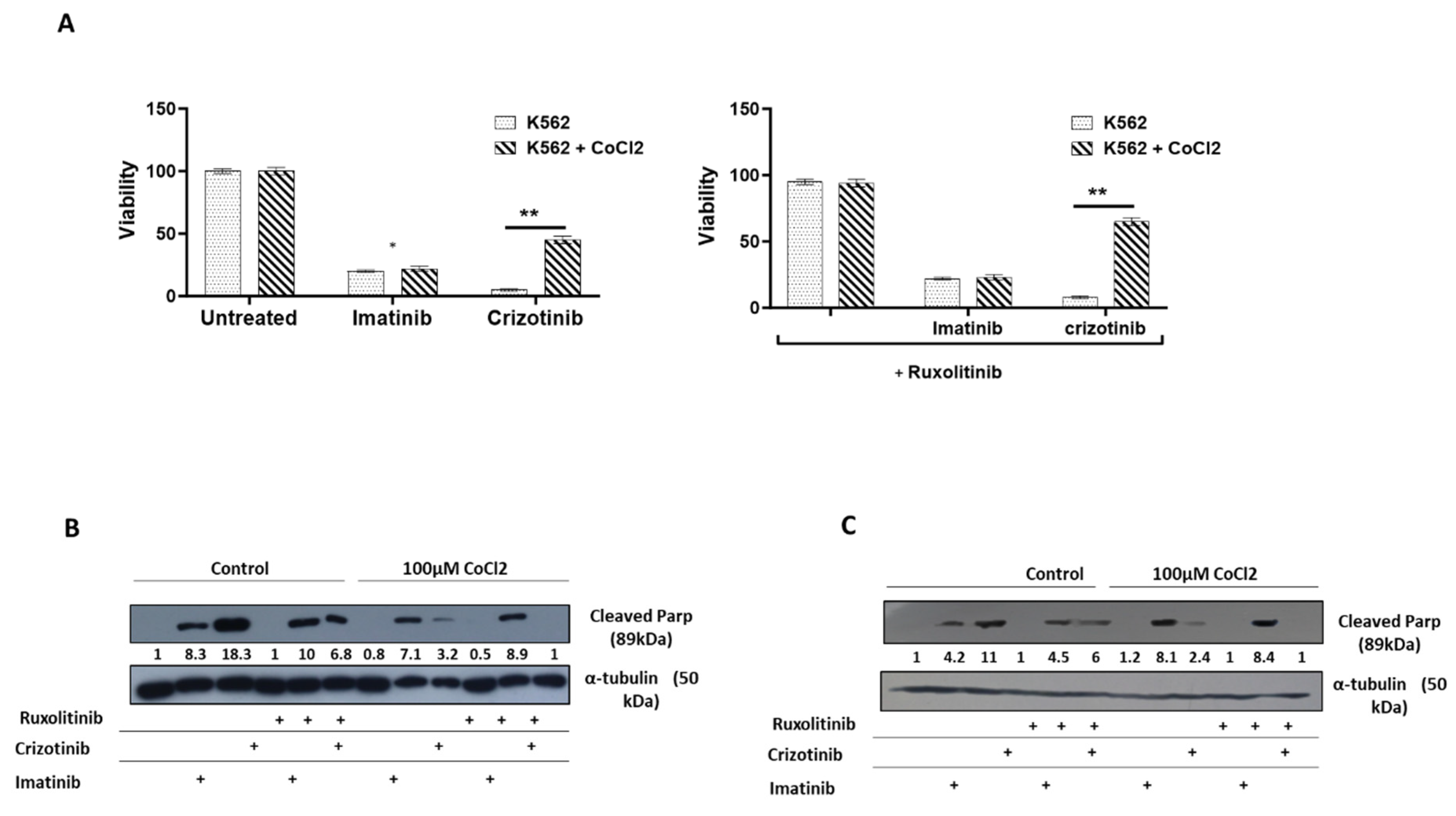

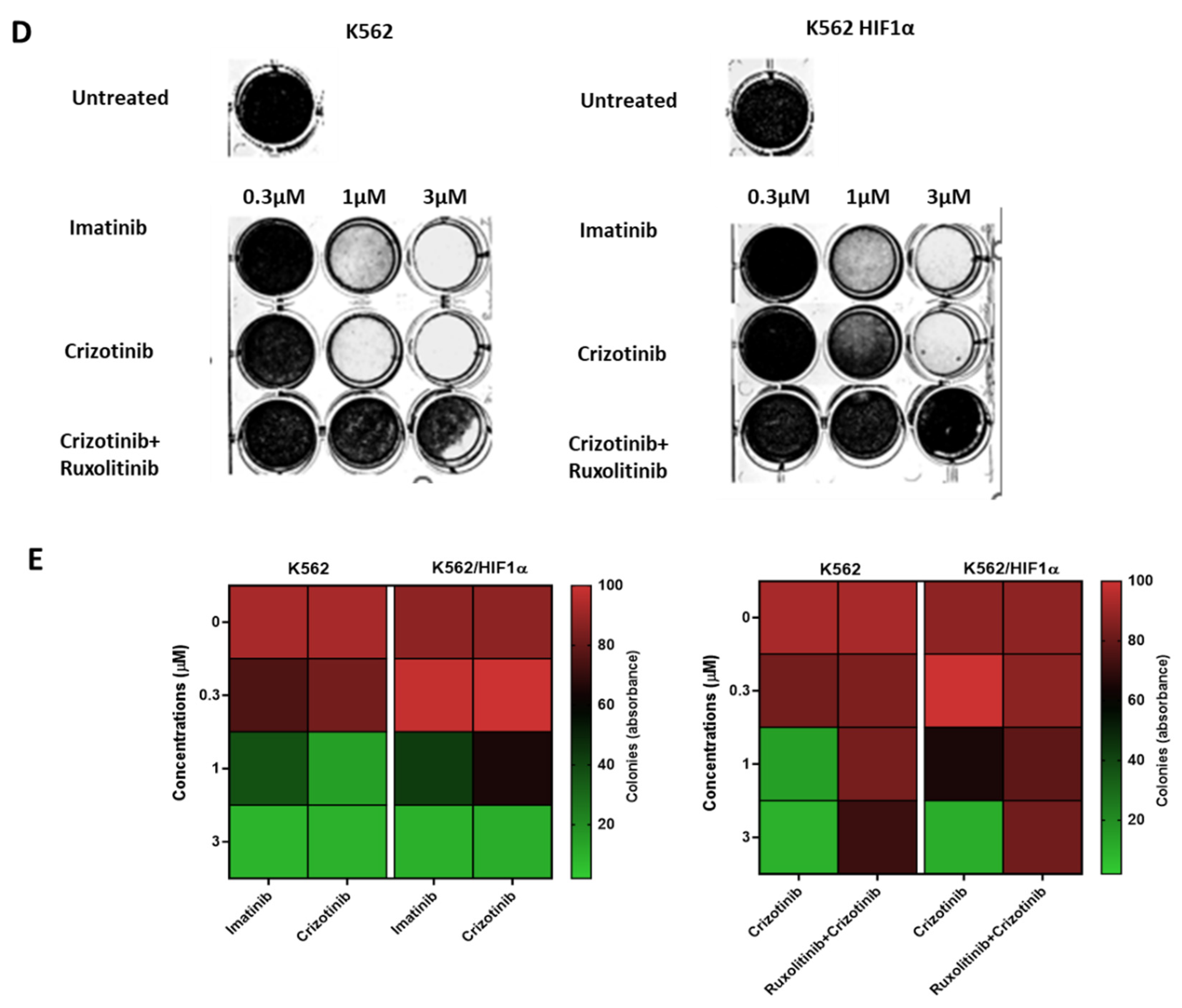

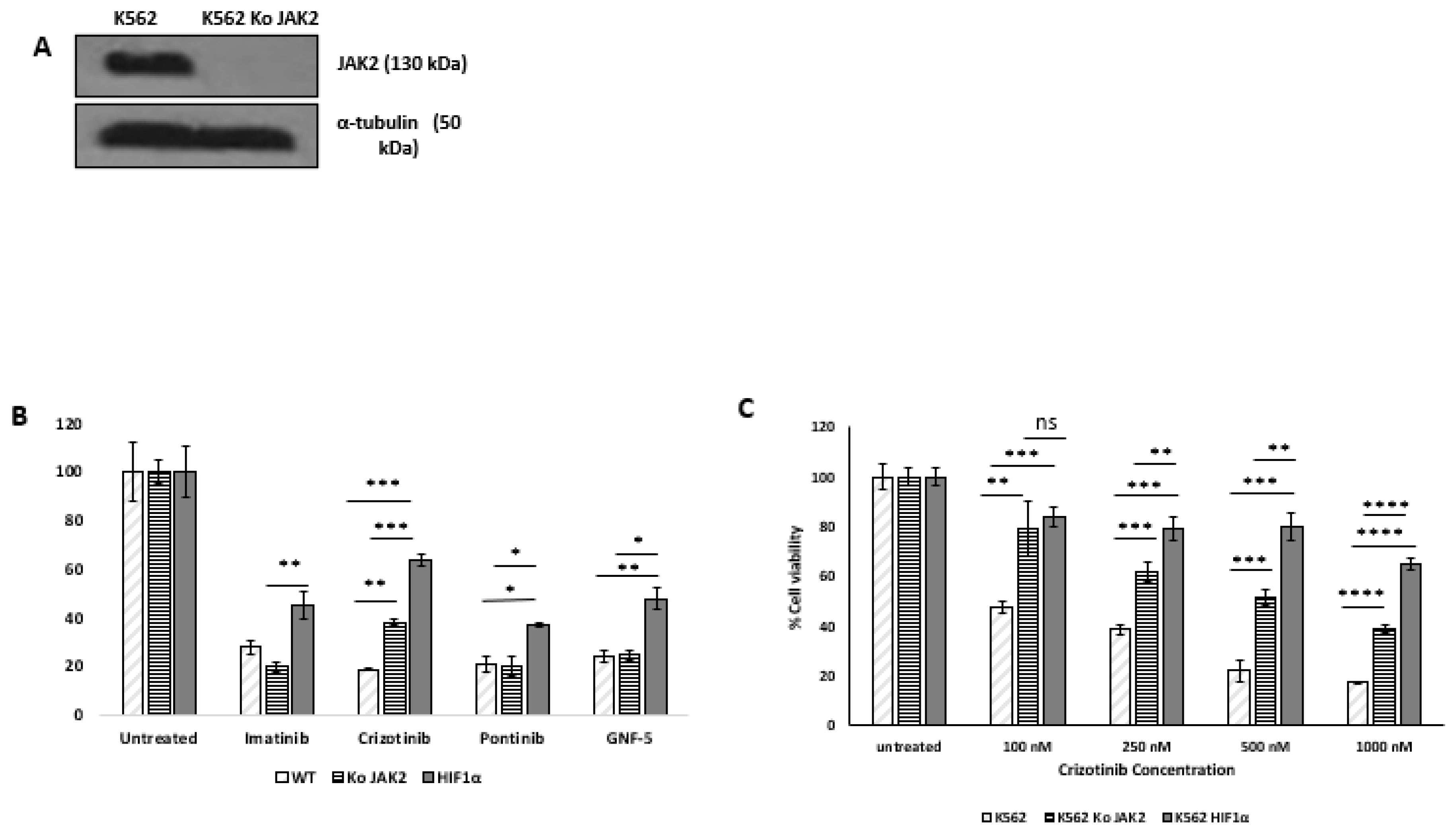

The role of HIF1α and JAK2 in mediating CML chemoresistance

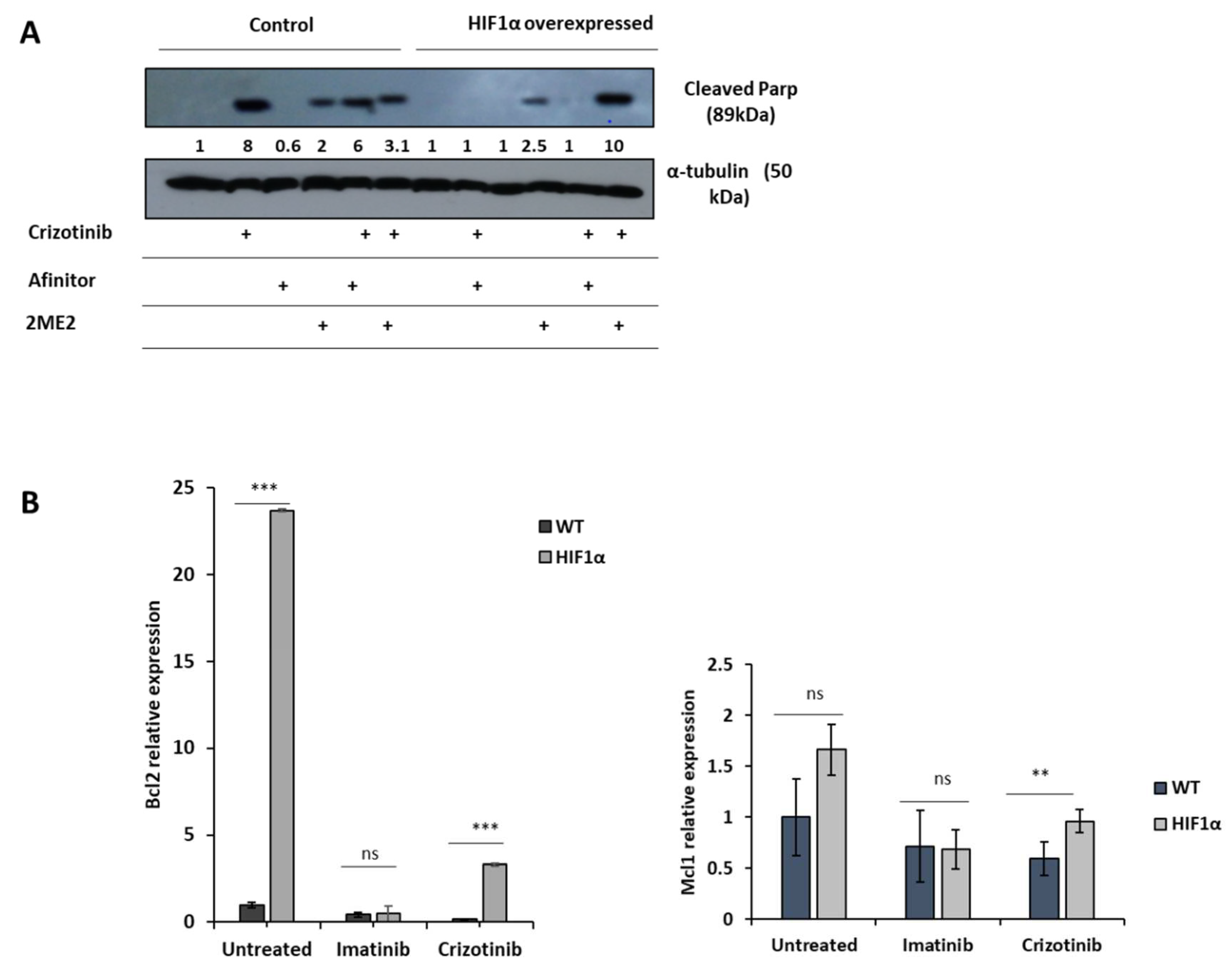

2ME2 restores crizotinib sensitivity of CML cells under hypoxic conditions

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faderl S, Talpaz M, Estrov Z, O’Brien S, Kurzrock R, Kantarjian HM. N Engl J Med 1999, 341, 164–167.

- Ottmann, O.G.; Hoelzer, D. The ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 (Glivec) in Philadelphia positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia - promises, pitfalls and possibilities. Hematol J 2002, 3, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radich, J.P.; Dai, H.; Mao, M.; Oehler, V.; Schelter, J.; Druker, B.; Sawyers, C.; Shah, N.; Stock, W.; Willman, C.L.; et al. Gene expression changes associated with progression and response in chronic myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 2794–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talpaz, M.; Silver, R.T.; Druker, B.J.; Goldman, J.M.; Gambacorti-Passerini, C.; Guilhot, F.; Schiffer, C.A.; Fischer, T.; Deininger, M.W.; Lennard, A.L.; et al. Imatinib induces durable hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with accelerated phase chronic myeloid leukemia: results of a phase 2 study. Blood 2002, 99, 1928–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambacorti-Passerini, C.B.; Gunby, R.H.; Piazza, R.; Galietta, A.; Rostagno, R.; Scapozza, L. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to imatinib in Philadelphia-chromosome-positive leukaemias. Lancet Oncol 2003, 4, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meads, M.B.; Hazlehurst, L.A.; Dalton, W.S. The bone marrow microenvironment as a tumor sanctuary and contributor to drug resistance. Clin Cancer Res 2008, 14, 2519–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, B.Z.; Polliack, A. Cancer microenvironment, extracellular matrix, and adhesion molecules: the bitter taste of sugars in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2011, 52, 1619–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witz, I.P. The tumor microenvironment: the making of a paradigm. Cancer Microenviron 2009, 2 Suppl 1, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfai, Y.; Ford, J.; Carter, K.W.; Firth, M.J.; O'Leary, R.A.; Gottardo, N.G.; Cole, C.; Kees, U.R. Interactions between acute lymphoblastic leukemia and bone marrow stromal cells influence response to therapy. Leuk Res 2012, 36, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Groffen, J.; Heisterkamp, N. Increased resistance to a farnesyltransferase inhibitor by N-cadherin expression in Bcr/Abl-P190 lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Leukemia 2007, 21, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.O.; Mortensen, B.T.; Hodgkiss, R.J.; Iversen, P.O.; Christensen, I.J.; Helledie, N.; Larsen, J.K. Increased cellular hypoxia and reduced proliferation of both normal and leukaemic cells during progression of acute myeloid leukaemia in rats. Cell Prolif 2000, 33, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.M.; Wilson, W.R. Exploiting tumour hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer 2004, 4, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minakata, K.; Takahashi, F.; Nara, T.; Hashimoto, M.; Tajima, K.; Murakami, A.; Nurwidya, F.; Yae, S.; Koizumi, F.; Moriyama, H.; et al. Hypoxia induces gefitinib resistance in non-small-cell lung cancer with both mutant and wild-type epidermal growth factor receptors. Cancer Sci 2012, 103, 1946–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruick, R.K. Expression of the gene encoding the proapoptotic Nip3 protein is induced by hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 9082–9087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Chen, X.; Huang, R.; Zeng, H.; Gong, J.; Meng, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Q. BCL-xL is a target gene regulated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1{alpha}. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 10004–10012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erler, J.T.; Cawthorne, C.J.; Williams, K.J.; Koritzinsky, M.; Wouters, B.G.; Wilson, C.; Miller, C.; Demonacos, C.; Stratford, I.J.; Dive, C. Hypoxia-mediated down-regulation of Bid and Bax in tumors occurs via hypoxia-inducible factor 1-dependent and -independent mechanisms and contributes to drug resistance. Mol Cell Biol 2004, 24, 2875–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Ahn, H.J.; Ryu, J.H.; Suk, K.; Park, J.H. BH3-only protein Noxa is a mediator of hypoxic cell death induced by hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. J Exp Med 2004, 199, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowter, H.M.; Ratcliffe, P.J.; Watson, P.; Greenberg, A.H.; Harris, A.L. HIF-1-dependent regulation of hypoxic induction of the cell death factors BNIP3 and NIX in human tumors. Cancer Res 2001, 61, 6669–6673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Comerford, K.M.; Wallace, T.J.; Karhausen, J.; Louis, N.A.; Montalto, M.C.; Colgan, S.P. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-dependent regulation of the multidrug resistance (MDR1) gene. Cancer Res 2002, 62, 3387–3394. [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley, S.R.; Print, C.; Farahi, N.; Peyssonnaux, C.; Johnson, R.S.; Cramer, T.; Sobolewski, A.; Condliffe, A.M.; Cowburn, A.S.; Johnson, N.; et al. Hypoxia-induced neutrophil survival is mediated by HIF-1alpha-dependent NF-kappaB activity. J Exp Med 2005, 201, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengler, V.L.; Galbraith, M.; Espinosa, J.M. Transcriptional regulation by hypoxia inducible factors. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 2014, 49, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, A.; Takahashi, F.; Nurwidya, F.; Kobayashi, I.; Minakata, K.; Hashimoto, M.; Nara, T.; Kato, M.; Tajima, K.; Shimada, N.; et al. Hypoxia increases gefitinib-resistant lung cancer stem cells through the activation of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. PLoS One 2014, 9, e86459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shain, K.H.; Yarde, D.N.; Meads, M.B.; Huang, M.; Jove, R.; Hazlehurst, L.A.; Dalton, W.S. Beta1 integrin adhesion enhances IL-6-mediated STAT3 signaling in myeloma cells: implications for microenvironment influence on tumor survival and proliferation. Cancer Res 2009, 69, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, R.R.; Tolentino, J.H.; Argilagos, R.F.; Zhang, L.; Pinilla-Ibarz, J.; Hazlehurst, L.A. Potentiation of Nilotinib-mediated cell death in the context of the bone marrow microenvironment requires a promiscuous JAK inhibitor in CML. Leuk Res 2012, 36, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traer, E.; Javidi-Sharifi, N.; Agarwal, A.; Dunlap, J.; English, I.; Martinez, J.; Tyner, J.W.; Wong, M.; Druker, B.J. Ponatinib overcomes FGF2-mediated resistance in CML patients without kinase domain mutations. Blood 2014, 123, 1516–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewry, N.N.; Nair, R.R.; Emmons, M.F.; Boulware, D.; Pinilla-Ibarz, J.; Hazlehurst, L.A. Stat3 contributes to resistance toward BCR-ABL inhibitors in a bone marrow microenvironment model of drug resistance. Mol Cancer Ther 2008, 7, 3169–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okabe, S.; Tauchi, T.; Katagiri, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Ohyashiki, K. Combination of the ABL kinase inhibitor imatinib with the Janus kinase 2 inhibitor TG101348 for targeting residual BCR-ABL-positive cells. J Hematol Oncol 2014, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, K.P.; Manjeri, A.; Lee, K.L.; Huang, W.; Tan, S.Y.; Chuah, C.T.; Poellinger, L.; Ong, S.T. Physiologic hypoxia promotes maintenance of CML stem cells despite effective BCR-ABL1 inhibition. Blood 2014, 123, 3316–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Qin, Y.; Liu, S. Cytokines, breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) and chemoresistance. Clin Transl Med 2018, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; He, G.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, J. Hypoxia induces inflammatory microenvironment by priming specific macrophage polarization and modifies LSC behaviour via VEGF-HIF1α signalling. Transl Pediatr 2021, 10, 1792–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidan, N.; Khamaisie, H.; Ruimi, N.; Roitman, S.; Eshel, E.; Dally, N.; Ruthardt, M.; Mahajna, J. Ectopic Expression of Snail and Twist in Ph+ Leukemia Cells Upregulates CD44 Expression and Alters Their Differentiation Potential. J Cancer 2017, 8, 3952–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Bartz, S.; Mao, M.; Li, L.; Kaelin, W.G., Jr. The hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha N-terminal and C-terminal transactivation domains cooperate to promote renal tumorigenesis in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 2007, 27, 2092–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.A.; Dykxhoorn, D.M.; Palliser, D.; Mizuno, H.; Yu, E.Y.; An, D.S.; Sabatini, D.M.; Chen, I.S.; Hahn, W.C.; Sharp, P.A.; et al. Lentivirus-delivered stable gene silencing by RNAi in primary cells. RNA 2003, 9, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najajreh, Y.; Khamaisie, H.; Ruimi, N.; Khatib, S.; Katzhendler, J.; Ruthardt, M.; Mahajna, J. Oleylamine-carbonyl-valinol inhibits auto-phosphorylation activity of native and T315I mutated Bcr-Abl, and exhibits selectivity towards oncogenic Bcr-Abl in SupB15 ALL cell lines. Mol Biol Rep 2013, 40, 2205–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gochman, E.; Mahajna, J.; Shenzer, P.; Dahan, A.; Blatt, A.; Elyakim, R.; Reznick, A.Z. The expression of iNOS and nitrotyrosine in colitis and colon cancer in humans. Acta Histochem 2012, 114, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, A.A.; Metodieva, A.; Badura, S.; Khateb, M.; Ruimi, N.; Najajreh, Y.; Ottmann, O.G.; Mahajna, J.; Ruthardt, M. Allosteric inhibition enhances the efficacy of ABL kinase inhibitors to target unmutated BCR-ABL and BCR-ABL-T315I. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren Carmi, Y.; Khamaisi, H.; Adawi, R.; Noyman, E.; Gopas, J.; Mahajna, J. Secreted Soluble Factors from Tumor-Activated Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Confer Platinum Chemoresistance to Ovarian Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dotan, N.; Wasser, S.P.; Mahajna, J. Inhibition of the androgen receptor activity by Coprinus comatus substances. Nutr Cancer 2011, 63, 1316–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Prabhash, K.; Noronha, V.; Joshi, A.; Desai, S. Crizotinib: A comprehensive review. South Asian J Cancer 2013, 2, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regev, O.; Kidan, N.; Nicola, M.; Khamisie, H.; Ruthardt, M.; Mahajna, J. Mesenchymal soluble factors confer imatinib drug resistance in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells. Arch Med Sci 2021, 17, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Yotnda, P. Induction and testing of hypoxia in cell culture. J Vis Exp, 3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvendiran, K.; Bratasz, A.; Kuppusamy, M.L.; Tazi, M.F.; Rivera, B.K.; Kuppusamy, P. Hypoxia induces chemoresistance in ovarian cancer cells by activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Int J Cancer 2009, 125, 2198–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostojic, A.; Vrhovac, R.; Verstovsek, S. Ruxolitinib: a new JAK1/2 inhibitor that offers promising options for treatment of myelofibrosis. Future Oncol 2011, 7, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snell, C.E.; Turley, H.; McIntyre, A.; Li, D.; Masiero, M.; Schofield, C.J.; Gatter, K.C.; Harris, A.L.; Pezzella, F. Proline-hydroxylated hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) upregulation in human tumours. PLoS One 2014, 9, e88955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, W.C.; Wilson, M.I.; Harlos, K.; Claridge, T.D.; Schofield, C.J.; Pugh, C.W.; Maxwell, P.H.; Ratcliffe, P.J.; Stuart, D.I.; Jones, E.Y. Structural basis for the recognition of hydroxyproline in HIF-1 alpha by pVHL. Nature 2002, 417, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamachary, B.; Penet, M.F.; Nimmagadda, S.; Mironchik, Y.; Raman, V.; Solaiyappan, M.; Semenza, G.L.; Pomper, M.G.; Bhujwalla, Z.M. Hypoxia regulates CD44 and its variant isoforms through HIF-1α in triple negative breast cancer. PLoS One 2012, 7, e44078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabjeesh, N.J.; Escuin, D.; LaVallee, T.M.; Pribluda, V.S.; Swartz, G.M.; Johnson, M.S.; Willard, M.T.; Zhong, H.; Simons, J.W.; Giannakakou, P. 2ME2 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis by disrupting microtubules and dysregulating HIF. Cancer Cell 2003, 3, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, O.; Samudio, I.; Benito, J.M.; Jacamo, R.; Kornblau, S.M.; Markovic, A.; Schober, W.; Lu, H.; Qiu, Y.H.; Buglio, D.; et al. Regulation of HIF-1alpha signaling and chemoresistance in acute lymphocytic leukemia under hypoxic conditions of the bone marrow microenvironment. Cancer Biol Ther 2012, 13, 858–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, A.A.; Haberbosch, I.; Khamaisie, H.; Agbarya, A.; Pietsch, L.; Eshel, E.; Najib, D.; Chiriches, C.; Ottmann, O.G.; Hantschel, O.; et al. Crizotinib acts as ABL1 inhibitor combining ATP-binding with allosteric inhibition and is active against native BCR-ABL1 and its resistance and compound mutants BCR-ABL1(T315I) and BCR-ABL1(T315I-E255K). Ann Hematol 2021, 100, 2023–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albadari, N.; Deng, S.; Li, W. The transcriptional factors HIF-1 and HIF-2 and their novel inhibitors in cancer therapy. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2019, 14, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogita, A.; Togashi, Y.; Hayashi, H.; Sogabe, S.; Terashima, M.; De Velasco, M.A.; Sakai, K.; Fujita, Y.; Tomida, S.; Takeyama, Y.; et al. Hypoxia induces resistance to ALK inhibitors in the H3122 non-small cell lung cancer cell line with an ALK rearrangement via epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Int J Oncol 2014, 45, 1430–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamski, J.; Price, A.; Dive, C.; Makin, G. Hypoxia-induced cytotoxic drug resistance in osteosarcoma is independent of HIF-1Alpha. PLoS One 2013, 8, e65304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, T.; Sun, S.; Wang, W.; Liu, G. Hypoxia promotes drug resistance in osteosarcoma cells via activating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling. J Bone Oncol 2016, 5, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, C.; Gouel, F.; Dubus, I.; Heuclin, C.; Roget, K.; Vannier, J.P. Hypoxia promotes chemoresistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines by modulating death signaling pathways. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, W.; Dong, X.; Qiao, H.; Sun, X.; Jiang, H. 2ME2 inhibits the activated hypoxia-inducible pathways by cabozantinib and enhances its efficacy against medullary thyroid carcinoma. Tumour Biol 2016, 37, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, S.S.; Salama, S.A.; Hassan, M.H.; Khalifa, A.E.; El-Demerdash, E.; Fouad, H.; Al-Hendy, A.; Abdel-Naim, A.B. 2-Methoxyestradiol reverses doxorubicin resistance in human breast tumor xenograft. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2008, 62, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, D.; Catley, L.; Hideshima, T.; Li, G.; Leblanc, R.; Gupta, D.; Sattler, M.; Richardson, P.; Schlossman, R.L.; Podar, K.; et al. 2-Methoxyestradiol overcomes drug resistance in multiple myeloma cells. Blood 2002, 100, 2187–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhani, N.J.; Sarkar, M.A.; Venitz, J.; Figg, W.D. 2-Methoxyestradiol, a promising anticancer agent. Pharmacotherapy 2003, 23, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamaisi, H.; Mahmoud, H.; Mahajna, J. 2-Hydroxyestradiol Overcomes Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Mediated Platinum Chemoresistance in Ovarian Cancer Cells in an ERK-Independent Fashion. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren Carmi, Y.; Khamaisi, H.; Adawi, R.; Noyman, E.; Gopas, J.; Mahajna, J. Secreted Soluble Factors from Tumor-Activated Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Confer Platinum Chemoresistance to Ovarian Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, X. Combined Effects of 2-Methoxyestradiol (Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1alpha Inhibitor) and Dasatinib (A Second-Generation Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor) on Chronic Myelocytic Leukemia Cells. J Immunol Res 2022, 2022, 6324326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Veldhuizen, P.J.; Ray, G.; Banerjee, S.; Dhar, G.; Kambhampati, S.; Dhar, A.; Banerjee, S.K. 2-Methoxyestradiol modulates beta-catenin in prostate cancer cells: a possible mediator of 2-methoxyestradiol-induced inhibition of cell growth. Int J Cancer 2008, 122, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVallee, T.M.; Zhan, X.H.; Johnson, M.S.; Herbstritt, C.J.; Swartz, G.; Williams, M.S.; Hembrough, W.A.; Green, S.J.; Pribluda, V.S. 2-methoxyestradiol up-regulates death receptor 5 and induces apoptosis through activation of the extrinsic pathway. Cancer Res 2003, 63, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Luna, M.A.; Rocha-Zavaleta, L.; Vega, M.I.; Huerta-Yepez, S. Hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha induces chemoresistance phenotype in non-Hodgkin lymphoma cell line via up-regulation of Bcl-xL. Leuk Lymphoma 2013, 54, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Sanchez, R.; Berzal, S.; Sanchez-Nino, M.D.; Neria, F.; Goncalves, S.; Calabia, O.; Tejedor, A.; Calzada, M.J.; Caramelo, C.; Deudero, J.J.; et al. AG490 promotes HIF-1alpha accumulation by inhibiting its hydroxylation. Curr Med Chem 2012, 19, 4014–4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Sánchez, R.; Berzal, S.; Sánchez-Niño, M.D.; Neria, F.; Gonçalves, S.; Calabia, O.; Tejedor, A.; Calzada, M.J.; Caramelo, C.; Deudero, J.J.; et al. AG490 promotes HIF-1α accumulation by inhibiting its hydroxylation. Curr Med Chem 2012, 19, 4014–4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, C.H.; Lee, H.J.; Cha, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, K.R.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, D.K.; Kim, K.W. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha inhibits self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells in Vitro via negative regulation of the leukemia inhibitory factor-STAT3 pathway. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 13672–13679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regev, O.; Kidan, N.; Khamisie, H.; Mahajna, J. Crizotinib overcomes microenvironment mediated drug resistance in Ph positive leukemia. European Journal of Cancer 2016, 61, S92–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).