1. Introduction

The earliest Periodic Table of Elements arranged the chemical elements according to periodic trends in physical properties. In 1864, John Newlands observed that when the known elements were arranged sequentially by increasing atomic weight, the properties of every first element strongly resembled the properties of every eighth like the notes of a musical octave. [

1] He called this the “Law of Octaves.” Newland’s fixed-period approach served as a necessary precursor to the present quantum mechanical understanding that electron shells or periods fill in varying lengths according to a set of “magic numbers,” including the numbers 2, 10, 18, 36, 54, and 86, wherein each successive shell contains the capacity for an ever greater number of electrons. [

2] The success of the electron shell model has encouraged a similar quest for an analogous nucleon shell model.

Mendeleev’s 1871 Periodic Table of Elements listed 63 elements. [

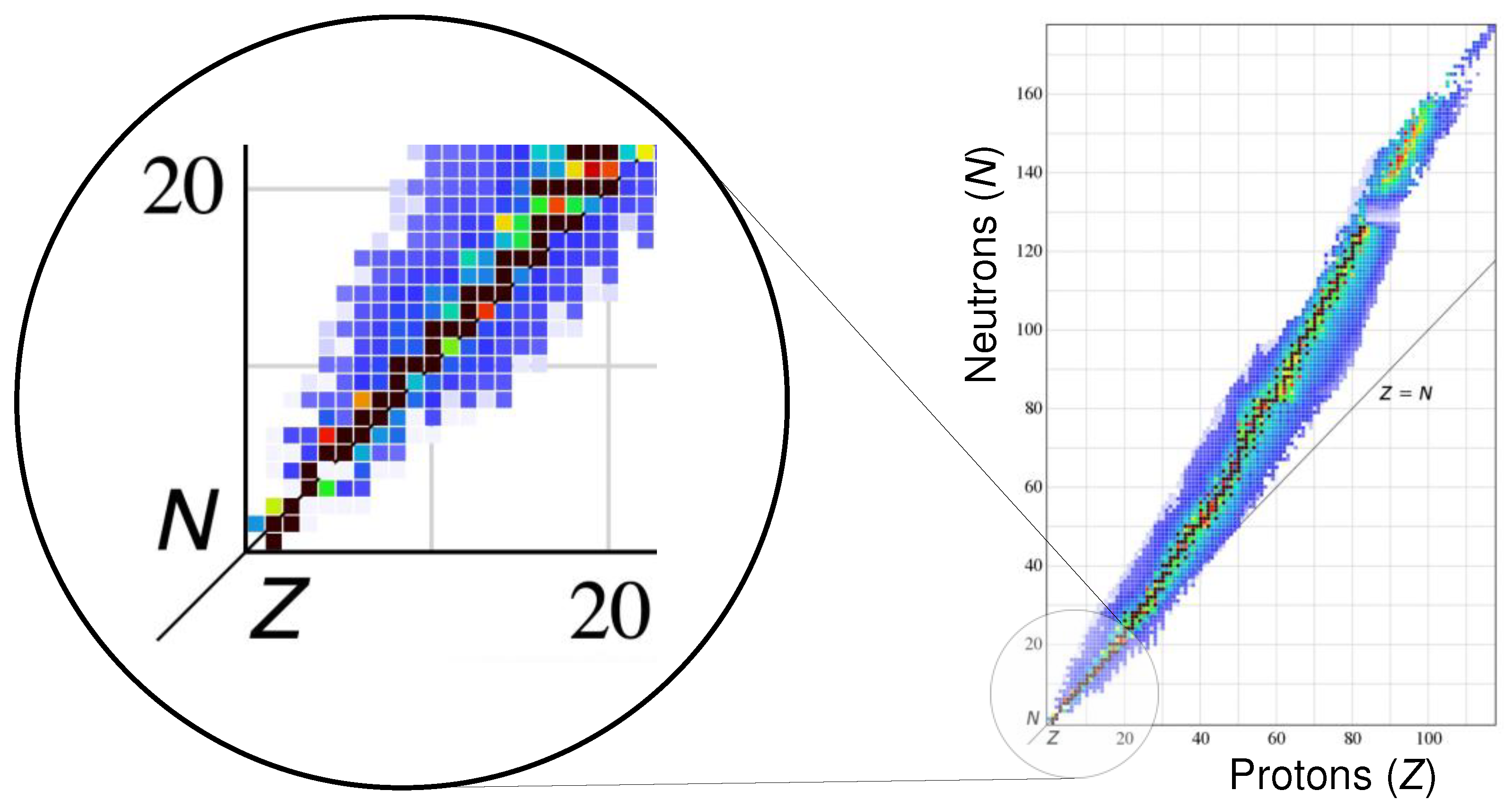

3] Per the IAEA, there are now 118 elements, more than 250 stable isotopes, and more than 3000 unstable isotopes, as rendered in the Segrè chart (

Figure 1(a)). [

4] Here the “Valley of Stability” representing the most stable nuclides is initially linear, then curves gently upward above

36Ar in favor of an increasing ratio of neutrons to protons. The predictable nature of this initial linear region may provide the most fertile ground for discerning fundamental periodic patterns in nuclear phenomena.

The goal of this manuscript is the identification of periodic trends. No assumptions are made about possible parallels between nuclear structure and electron cloud structure. Electron shells or periods fill according to a set of variable and increasing magic numbers, but this manuscript employs the early

fixed-period methodology that resulted in Newlands’ Law of Octaves. This was a prelude to the “octet rule” of Lewis dot structures 40 years later, which established (in representational form) an association between underlying electron structure and the 8-element period of recurring elemental physical properties. [

5]

Using this fixed-period methodology, the first property considered is the nuclear magnetic moment

µ, which equals zero due to nucleon pairing effects when the numbers of protons and neutrons are both even. Since stable nuclides through

36Ar increase one AMU at a time, this means that every other magnetic moment equals zero beginning with

16O as illustrated in

Figure 2 below. Otherwise, the nuclear magnetic moment

µ is unique for each nuclide and varies in sign and magnitude as mass number increases. The variability initially appears random, and although Segrè studied quadrupole moment periodicity with some success, no periodic patterns have been previously identified. [

6]

The magnetic moment is an experimentally determined value. [

7] It is thought to derive from the spin of nucleons and their quarks but is not simply the sum of quark magnetic moments. [

8] While spin is an intrinsic form of angular momentum, the nuclear magnetic moment also depends on orbital angular momentum, which relates to how a nucleus rotates in space. [

9] The relative contributions of intrinsic versus orbital angular momentum are still an active field of research.

A second nuclear property is the change in total nucleon binding energy with the addition of each added nucleon (∆BE), which is also unique for each nuclide. Bohr and Mottelson analyzed the related proton and neutron separation energies of isotopes with even mass numbers and found limited evidence of shell-like periodicity, but only above N=50, 82, and 126. Neither Segrè nor Bohr and Mottelson were analyzing the data in search of a hypothetical

fixed period length, however. [

10]

The working hypothesis here is that the unique nuclide-to-nuclide variability in both µ and ∆BE reflects the evolving underlying light nuclide structure. Like the Rule of Octaves, the period length of nuclear physical properties might serve as a preliminary step in identifying recurring nuclear structural patterns in a way that parallels the relationship between elemental physical properties and electron orbital structure.

2. Theory and Methods

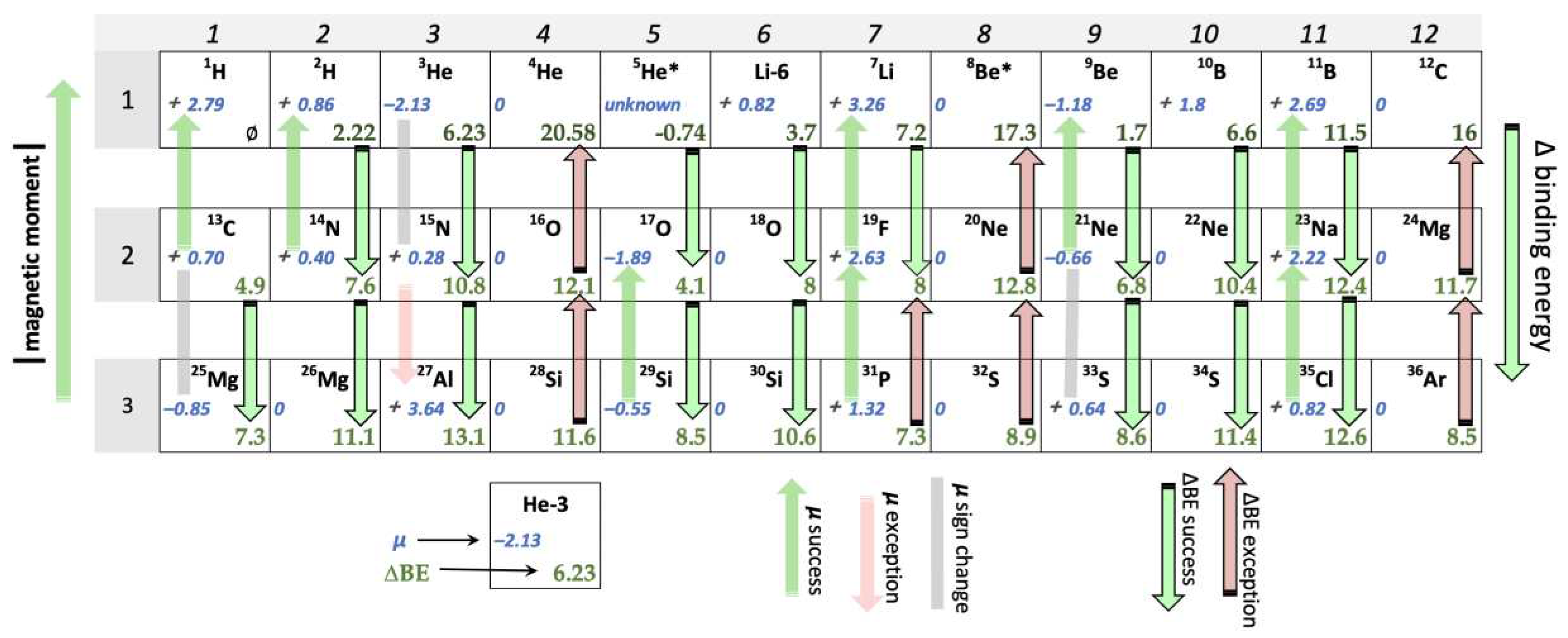

The nuclides of interest are listed in sequence by ascending order according to atomic mass, associated with their respective magnetic moments and binding energies. As per the method of Newlands, the nuclides were then grouped into fixed periods containing 4-18 nucleons per period. These periodic groupings were stacked on top of one another so that the nuclides of one period aligned vertically with the nuclides of the succeeding period directly below it. Nuclear magnetic moments and ∆BE were then evaluated for vertical trends. (See Figure 2 for the 12-nucleon iteration.)

The periodicity of ∆BE is a straightforward assessment. The total binding energy of each nuclide may be determined either from the mass deficit and Einstein’s equation E=mc

2, or from published tables. [

11] The ∆BE of a nuclide is determined from the difference in the total binding energy of the nuclide of interest and the total binding energy of the previous light stable nuclide in the sequence. With only one exception (unstable

5He*), all ∆BE values are positive, consistent with a release (in light nuclides) of varying amounts of energy with the addition (fusion) of each individual nucleon. Across the various period lengths, in the majority of nuclide-to-nuclide vertical trends, the ∆BE appeared to generally increase in the direction of the bottom of the page as shown in Figure 2. Any ∆BE consistent with this general trend is counted as a "trend confirmation". An example would be the trend from

6Li to

18O below depicted as a green arrow. A ∆BE trend in the opposite direction is counted as a "trend exception," as in the trend from

24Mg to

12C below depicted as a red arrow. The number of trend confirmations divided by the sum of the trend confirmations plus the trend exceptions yields the percent trend confirmation for each period length.

A similar approach was taken with the analysis of magnetic moments. Across the various period lengths, the magnitude of non-zero magnetic moments tends to increase in the direction of the top of the page. A “trend confirmation” is defined as the case in which the absolute value of the magnetic moment increased in the direction of the top of the page while maintaining the same sign. An example would be the trend from 14N to 2H below depicted as a green arrow. A "trend exception" is indicated by a trend in the opposite direction, as in the example of 15N to 27Al depicted with a red arrow below. A second type of trend exception occurs when the sign of the magnetic moment changes between a pair of vertically aligned nuclides, as in the trend between 3He and 15N depicted by a gray bar below. The cases in which the magnetic moments of a pair of vertically aligned nuclides are both equal to zero (4He and 16O, for example) do not indicate a trend in either direction and thus were not included within the µ trend analysis. As with ∆BE, the number of trend confirmations divided by the sum of the trend confirmations plus the trend exceptions yields the percent trend confirmation for each period length.

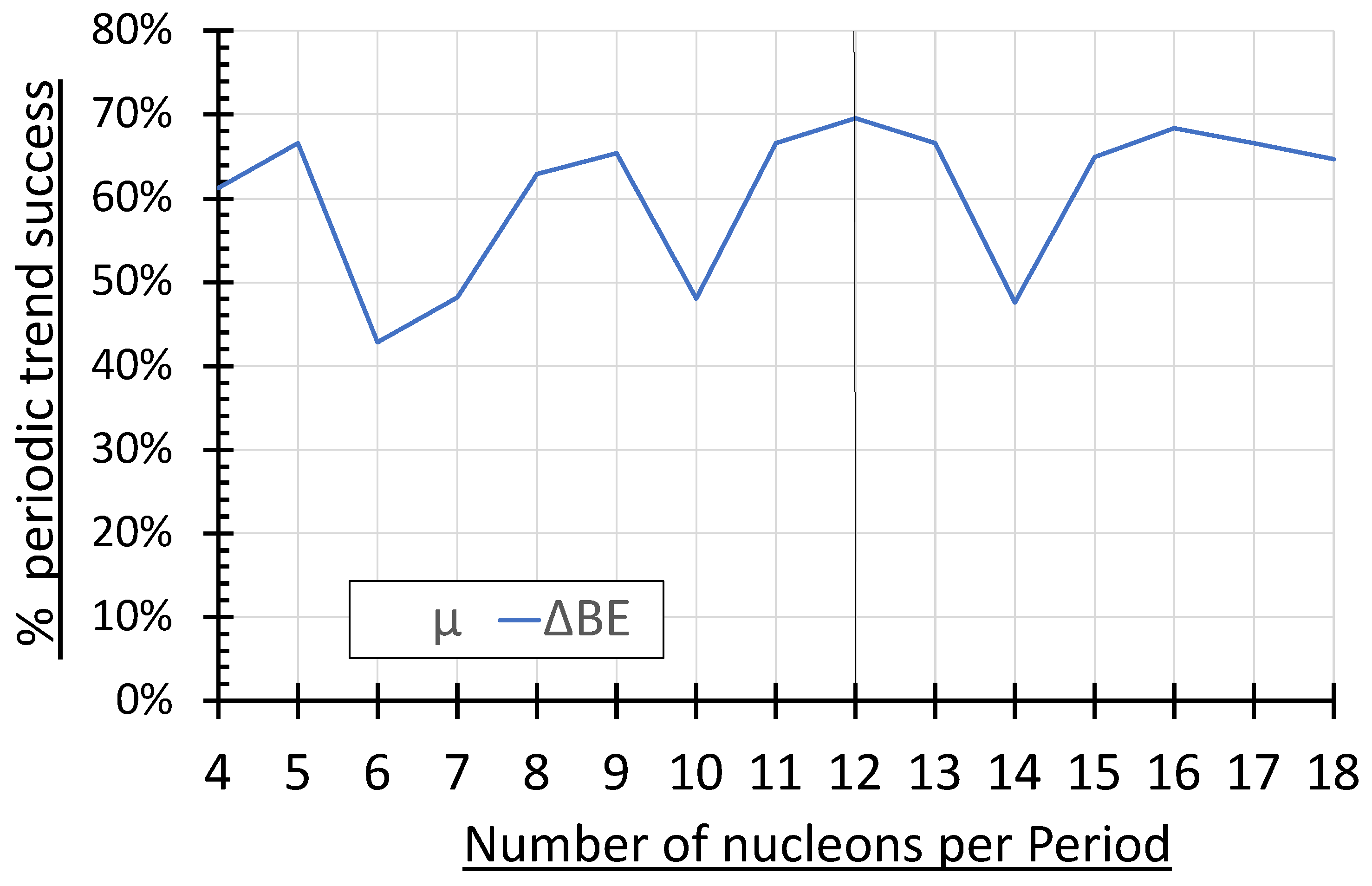

Figure 3 illustrates an analysis of the 503 individual trends considered within all period lengths from 4 through 18 equals 503, including 138 trends in

µ and 365 trends in ∆BE. [

12] The number of trends considered for

µ ranged from a low of 4 trends per period in the 9- and 13-nucleon period lengths to a high of 17 trends within the 4-nucleon period length. The average number of trends in

µ was 9 trends per period, and 12 trends were considered within the 12-nucleon period length. The number of trends considered for ∆BE ranged from a low of 18 trends per period in the 17-nucleon period length to a high of 31 trends within the 4-nucleon period length. The average number of trends in ∆BE was 25 trends per period, and 23 trends were considered within the 12-nucleon period length. (Note: The low trend confirmation rates in

µ depicted in

Figure 3 do NOT represent trends in the opposite direction but represent a change, for the most part, in the sign of the nuclear magnetic moments. [

12])

Nuclear magnetic moments of zero are known to recur periodically whenever the number of protons and the number of neutrons equals zero. Above

16O, nuclear magnetic moments of zero recur every four nuclides and can be thought of as exhibiting a fixed, 4-nuclide period consistent with nucleon pairing effects. It is therefore expected that this fixed 4-nuclide period would be embedded within the results of any periodicity analysis of nuclear magnetic moments, as manifest in

Figure 3(b).

3. Results

The periodicity of nuclear magnetic moments and the binding energy of the last added nucleon were analyzed for hypothetical period lengths ranging from 4 to 18 nucleons per period. Nuclear magnetic moments tended to increase up a column while maintaining the same sign (a

µ trend confirmation), and the ∆BE tended to increase down a column (a ∆BE trend confirmation). The number of trend confirmations divided by the sum of the confirmations and exceptions yielded the percent for each nuclear property. The percent confirmation rate for each period length is plotted in

Figure 3. Both properties demonstrate an oscillating pattern of maxima every ≈ 4-nucleon period starting at 4 nucleons per Period, and minima every ≈ 4-nucleon period starting at 6 nucleons per Period. The 12-nucleon period demonstrated the best percent confirmation rate for both

µ and ∆BE, with rates of 67% and 70%, respectively.

Analysis of the 12-nucleon period also reveals a recurring 4-nucleon trend in columns 4, 8, and 12 of

Figure 2. The nuclides within these columns have in common an even number of protons and neutrons, and the number of protons equals the number of neutrons. This phenomenon is well documented within the nucleon pairing effect, characterized in each case by a magnetic moment of zero. Curiously, for every 4n nucleons (columns 4, 8, and 12) the trend in ∆BE is systematically

reversed, as indicated by a red arrow pointing towards the top of the page. This pattern accounts for six out of seven instances (86%) of trend exceptions in ∆BE in the 12-nucleon case. The pattern is less regular and less pronounced in the 4-nucleon (67%) and 8-nucleon (70%) cases (see supplement). [

12] Only in the 12-nucleon case do both the trend confirmations and trend exceptions exhibit this degree of symmetry.

4. Discussion

The central hypothesis of this treatment of nuclear periodicity is that unique µ and ∆BE values derive from their unique nuclide structures as manifested by their periodicity. This is analogous to the way that elemental physical properties ultimately derive from their respective unique electron orbital structures.

The nuclear magnetic moment and nucleon binding energy are disparate nuclear phenomena, and yet their periodicities appear to correspond in

Figure 3. The nucleon binding energy arises from the association of nucleons bound within the atomic nucleus and therefore relates to the strong nuclear force. Conversely, the nuclear magnetic moment may relate (simplistically) to the +2/3 and- 1/3 electrostatic charges on up and down quarks respectively. Though seemingly unrelated, the two nuclear phenomena may both relate to nuclear structure. Assuming the nucleus possesses a component of rotational kinetic energy, the sign and magnitude of the nuclear magnetic moment would be influenced by the movement and relative positions of quark charge. The strong nuclear force notwithstanding, the association of opposite quark charge within the confined space of the nucleus would also have electrostatic potential energy implications, as the magnitude of this electrostatic potential energy would also depend on the relative positions of quark charge. The similar undulating morphology and inflection points in both the nucleon binding energy and nuclear magnetic moment curves depicted in

Figure 3 may suggest a similar periodic structural source for both phenomena. Although the exact structural basis for this periodicity is unknown at this time, the data supports a 4n periodicity (consistent with nucleon pairing) superimposed on the observed 12-n periodicity. The precise convergence of

µ and ∆BE periodicity at the 12-nucleon period may prove an important parameter in future structural models of the atomic nucleus.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- J. A. Newlands, "On Relations Among the Equivalents," Chemical News, vol. 7, pp. 70-72, 7 February 1863.

- L. Pauling, "The Nature of the Chemical Bond. Application of Results Obtained from the Quantum Mechanics and from a Theory of Paramagnetic Susceptibility to the Structure of Molecules," Journal of the American Chemical Society, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 1367-1400., 1931. [CrossRef]

- P. Strathern, "Chapter 14. The Periodic Table," in Mendeleyev's Dream, New York, Pegasus Books Ltd., 2001, p. 287.

- "Valley of Stability," [Online]. Available: By Bdushaw - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61302797.

- G. N. Lewis, "The Atom and the Molecule," J. Am. Chem. Soc., vol. 38, no. (4), pp. 762-785, 1916. [CrossRef]

- E. Segre, Nuclei and Particles, Reading, Mass.: W.A. Benjamin, 1964.

- K. S. Krane, "Extensions and applications," in Introductory Nuclear Physics, New York, Wiley, 1988, p. 625.

- E. Cartlidge, "The spin of a proton," Phys. World, vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 28-32, 2015.

- L. LANDAU and E. LIFSHITZ, "CHAPTER VIII - SPIN," in Quantum Mechanics, Elsevier, 1977, pp. 197-224.

- Bohr, A. and Mottelson, B., Nuclear Structure, Reading, MA: Benjamin, 1969.

- High Energy Physics Division, "High Energy Physics Division," dbserv.pnpi.spb.ru, [Online]. Available: http://dbserv.pnpi.spb.ru/elbib/tablisot/toi98/www/astro/table2.pdf. [Accessed 1 July 2023].

- APPENDIX A: Comparison of periodic sequence length for nuclear magnetic moments and ∆nucleon binding energies.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).